#they used to claim that frank was a better guitar player than ray and that ray would take credit for frank's parts KSJDGKLJSDLGSD

Note

who the fuck is ode2 I can't find their blog????

lol honestly don't wanna give them any more attention than they used to get so i'm not gonna link their blog but they were an extremely extremely disrespectful and invasive tinhatter who would openly speculate about things including but not limited to gerard's struggles with addiction, parenting style, marital relationship etc, based on evidence of absolutely nothing (besides their ~special connection~ with frank) to push the narrative that gerard has been stringing frank along in some kind of sick abusive sexual relationship for years and years while lynz is also abusing gerard and controlling his every move and sapping his personality and also cyberbullying frank on instagram stories LMAO. seems like they got their entire worldview shattered when mcr returned and confirmed that, shock horror, they are in fact friends who enjoy spending time with each other, because they've stopped posting theories so much on their blog and wrote a pinned message that includes the point "YES grown adults act like teenage girls on social media," said entirely seriously and unironically. they're kind of like the example of that one breed of frerardie who claims to love frank but seems to ignore his actual personality in favour of treating him like a poor uwu abused baby who's never stood up for anything once in his life and treats gerard like an idol rather than a friend, but magnified by a million and even more disconnected from reality. genuinely a really sad blog filled with a lot of hate and im glad they've stepped back from spending every day posting about their theories

#i do hope they're seeking therapy tbh#sorry if this sounds extremely mean i just woke up from the world's worst nap#but im not kidding when i say this blog was disgustingly invasive disgustingly misogynistic#and above all disgusting in the way they openly discussed a stranger's mental health and experiences with addiction#it was based on absolutely nothing too but even if it was it would have been gross#also this isn't as serious but it IS funny:#they used to claim that frank was a better guitar player than ray and that ray would take credit for frank's parts KSJDGKLJSDLGSD#which if nothing else highlights their impressive immaturity and ability to ignore everything about how the band works#and refusal to listen to anything any of them actually said except maybe frank#anyway i'm gonna take my own advice and stop talking about them now we can all just pretend they never existed#idek what prompted this i didn't think i'd talked about them in a while sdjkflsjds#dash vibes are already bad. send post.#answered

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

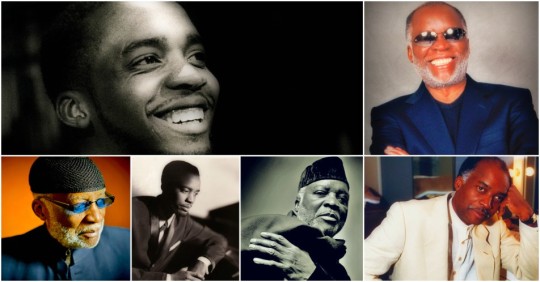

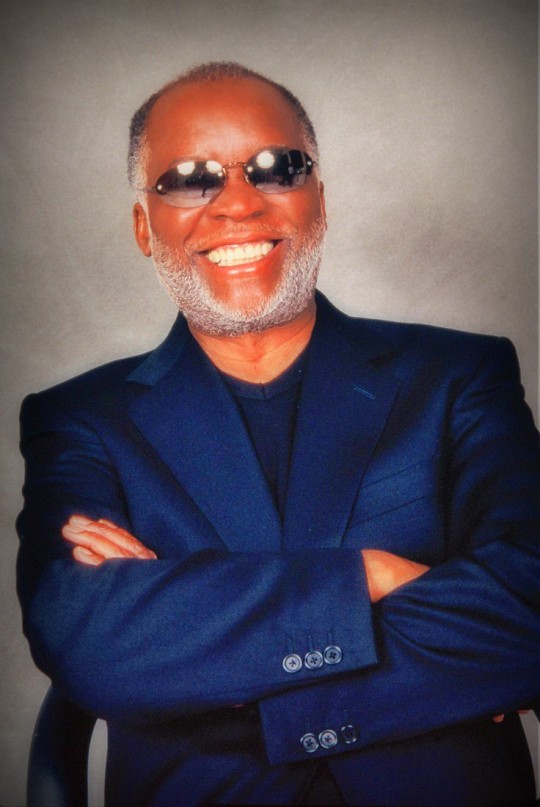

Ahmad Jamal

Ahmad Jamal (born Frederick Russell Jones, July 2, 1930) is an American jazz pianist, composer, bandleader, and educator. For five decades, he has been one of the most successful small-group leaders in jazz.

Biography

Early life

Jamal was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He began playing piano at the age of three, when his uncle Lawrence challenged him to duplicate what he was doing on the piano. Jamal began formal piano training at the age of seven with Mary Cardwell Dawson, whom he describes as greatly influencing him. His Pittsburgh roots have remained an important part of his identity ("Pittsburgh meant everything to me and it still does," he said in 2001) and it was there that he was immersed in the influence of jazz artists such as Earl Hines, Billy Strayhorn, Mary Lou Williams, and Erroll Garner. Jamal also studied with pianist James Miller and began playing piano professionally at the age of fourteen, at which point he was recognized as a "coming great" by the pianist Art Tatum. When asked about his practice habits by a New York Times critic, Jamal commented that, "I used to practice and practice with the door open, hoping someone would come by and discover me. I was never the practitioner in the sense of twelve hours a day, but I always thought about music. I think about music all the time."

Beginnings and conversion to Islam

Jamal began touring with George Hudson's Orchestra after graduating from George Westinghouse High School in 1948. He joined another touring group known as The Four Strings, which soon disbanded when the violinist, Joe Kennedy. Jr., left. He moved to Chicago in 1950 (where he legally changed his name to Ahmad Jamal), and played on and off with local musicians such as saxophonists Von Freeman and Claude McLin, as well as performing solo at the Palm Tavern, occasionally joined by drummer Ike Day.

Born to Baptist parents in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Jamal did not discover Islam until his early 20s. While touring in Detroit (where there was a sizable Muslim community in the 1940s and 1950s), Jamal became interested in Islam and Islamic culture. He converted to Islam and changed his name to Ahmad Jamal in 1950. In an interview with The New York Times a few years later, Jamal said his decision to change his name stemmed from a desire to "re-establish my original name." Shortly after his conversion to Islam, Jamal explained to The New York Times that he "says Muslim prayers five times a day and arises in time to say his first prayers at 5 am. He says them in Arabic in keeping with the Muslim tradition."

He made his first sides in 1951 for the Okeh label with The Three Strings (which would later also be called the Ahmad Jamal Trio, although Jamal himself prefers not to use the term "trio"): the other members were guitarist Ray Crawford and a bassist, at different times Eddie Calhoun (1950–52), Richard Davis (1953–54), and Israel Crosby (from 1954). The Three Strings arranged an extended engagement at Chicago's Blue Note, but leapt to fame after performing at the Embers in New York City where John Hammond saw the band play and signed them to Okeh Records. Hammond, a record producer who discovered the talents and enhanced the fame of musicians like Benny Goodman, Billie Holiday, and Count Basie, also helped Jamal's trio attract critical acclaim. Jamal subsequently recorded for Parrot (1953–55) and Epic (1955) using the piano-guitar-bass lineup.

At the Pershing: But Not For Me

The trio's sound changed significantly when Crawford was replaced with drummer Vernel Fournier in 1957, and the group worked as the "House Trio" at Chicago's Pershing Hotel. The trio released the live album, Live at the Pershing: But Not For Me, which stayed on the Ten Best-selling charts for 108 weeks. Jamal's well known song "Poinciana" was first released on this album.

Perhaps Jamal's most famous recording and undoubtedly the one that brought him vast popularity in the late 1950s and into the 1960s jazz age, At the Pershing was recorded at the Pershing Hotel in Chicago in 1958. Jamal played the set with bassist Israel Crosby and drummer Vernel Fournier. The set list expressed a diverse collection of tunes, including "The Surrey with the Fringe On Top" from the musical Oklahoma! and Jamal's arrangement of the jazz standard "Poinciana". Jazz musicians and listeners alike found inspiration in the At the Pershing recording, and Jamal's trio was recognized as an integral new building block in the history of jazz. Evident were his unusually minimalist style and his extended vamps, according to reviewer John Morthland. "If you're looking for an argument that pleasurable mainstream art can assume radical status at the same time, Jamal is your guide," said The New York Times contributor Ben Ratliff in a review of the album.

After the recording of the best-selling album But Not For Me, Jamal's music grew in popularity throughout the 1950s, and he attracted media coverage for his investment decisions pertaining to his "rising fortune". In 1959, he took a tour of North Africa to explore investment options in Africa. Jamal, who was twenty-nine at the time, said he had a curiosity about the homeland of his ancestors, highly influenced by his conversion to the Muslim faith. He also said his religion had brought him peace of mind about his race, which accounted for his "growth in the field of music that has proved very lucrative for me." Upon his return to the U.S. after a tour of North Africa, the financial success of Live at the Pershing: But Not For Me allowed Jamal to open a restaurant and club called The Alhambra in Chicago. In 1962, The Three Strings disbanded and Jamal moved to New York City, where, at the age of 32, he took a three-year hiatus from his musical career.

Return to music and The Awakening

In 1964, Jamal resumed touring and recording, this time with the bassist Jamil Nasser and recorded a new album, Extensions, in 1965. Jamal and Nasser continued to play and record together from 1964 to 1972. He also joined forces with Fournier (again, but only for about a year) and drummer Frank Gant (1966–76), among others. Until 1970, he played acoustic piano exclusively. The final album on which he played acoustic piano in the regular sequence was The Awakening. In the 1970s, he played electric piano as well. It was rumored that the Rhodes piano was a gift from someone in Switzerland. He continued to play throughout the 1970s and 1980s, mostly in trios with piano, bass and drums, but he occasionally expanded the group to include guitar. One of his most long-standing gigs was as the band for the New Year's Eve celebrations at Blues Alley in Washington, D.C., from 1979 through the 1990s.

Later career

In 1986, Jamal sued critic Leonard Feather for using his former name in a publication.

Clint Eastwood featured two recordings from Jamal's But Not For Me album — "Music, Music, Music" and "Poinciana" — in the 1995 movie The Bridges of Madison County.

Now in his eighties, Ahmad Jamal has continued to make numerous tours and recordings. His most recently released albums are Saturday Morning (2013), and the CD/DVD release Ahmad Jamal Featuring Yusef Lateef Live at L'Olympia (2014).

Jamal is the main mentor of jazz piano virtuosa Hiromi Uehara, known as Hiromi.

Style and influence

Trained in both traditional jazz ("American classical music", as he prefers to call it) and European classical style, Ahmad Jamal has been praised as one of the greatest jazz innovators over his exceptionally long career. Following bebop greats like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, Jamal entered the world of jazz at a time when speed and virtuosic improvisation were central to the success of jazz musicians as artists. Jamal, however, took steps in the direction of a new movement, later coined "cool jazz" – an effort to move jazz in the direction of popular music. He emphasized space and time in his musical compositions and interpretations instead of focusing on the blinding speed of bebop.

Because of this style, Jamal was "often dismissed by jazz writers as no more than a cocktail pianist, a player so given to fluff that his work shouldn't be considered seriously in any artistic sense". Stanley Crouch, author of Considering Genius, offers a very different reaction to Jamal's music, claiming that, like the highly influential Thelonious Monk, Jamal was a true innovator of the jazz tradition and is second in importance in the development of jazz after 1945 only to Parker. His unique musical style stemmed from many individual characteristics, including his use of orchestral effects and his ability to control the beat of songs. These stylistic choices resulted in a unique and new sound for the piano trio: "Through the use of space and changes of rhythm and tempo", writes Crouch, "Jamal invented a group sound that had all the surprise and dynamic variation of an imaginatively ordered big band." Jamal explored the texture of riffs, timbres, and phrases rather than the quantity or speed of notes in any given improvisation. Speaking about Jamal, A. B. Spellman of the National Endowment of the Arts said: "Nobody except Thelonious Monk used space better, and nobody ever applied the artistic device of tension and release better." These (at the time) unconventional techniques that Jamal gleaned from both traditional classical and contemporary jazz musicians helped pave the way for later jazz greats like Bill Evans, Herbie Hancock, and McCoy Tyner.

Though Jamal is often overlooked by jazz critics and historians, he is frequently credited with having a great influence on Miles Davis. Davis is quoted as saying that he was impressed by Jamal's rhythmic sense and his "concept of space, his lightness of touch, his understatement". Jamal characterizes what he thought Davis admired about his music as: "my discipline as opposed to my space." Jamal and Davis became friends in the 1950s, and Davis continued to support Jamal as a fellow musician, often playing versions of Jamal's own songs ("Ahmad's Blues", "New Rhumba") until he died in 1991.

Jamal, speaking about his own work says, "I like doing ballads. They're hard to play. It takes years of living, really, to read them properly." From an early age, Jamal developed an appreciation for the lyrics of the songs he learned: "I once heard Ben Webster playing his heart out on a ballad. All of a sudden he stopped. I asked him, 'Why did you stop, Ben?' He said, 'I forgot the lyrics.'" Jamal attributes the variety in his musical taste to the fact that he grew up in several eras: the big band era, the bebop years, and the electronic age. He says his style evolved from drawing on the techniques and music produced in these three eras. In 1985, Jamal agreed to do an interview and recording session with his fellow jazz pianist, Marian McPartland on her NPR show Piano Jazz. Jamal, who said he rarely plays "But Not For Me" due to its popularity since his 1958 recording, played an improvised version of the tune – though only after noting that he has moved on to making ninety percent of his repertoire his own compositions. He said that when he grew in popularity from the Live at the Pershing album, he was severely criticized afterwards for not playing any of his own compositions.

In more recent years, Jamal has embraced the electronic influences affecting the genre of jazz. He has also occasionally expanded his usual small ensemble of three to include a tenor saxophone (George Coleman) and a violin. A jazz fan interviewed by Down Beat magazine about Jamal in 2010 described his development as "more aggressive and improvisational these days. The word I used to use is avant garde; that might not be right. Whatever you call it, the way he plays is the essence of what jazz is."

Saxophonist Ted Nash, a longtime member of the Lincoln Center Orchestra, had the opportunity to play with Jamal in 2008 for Jazz at Lincoln Center. Nash described his experience with Jamal's style in an interview with Down Beat magazine: "The way he comped wasn't the generic way that lots of pianists play with chords in the middle of the keyboard, just filling things up. He gave lots of single line responses. He'd come back and throw things out at you, directly from what you played. It was really interesting because it made you stop, and allowed him to respond, and then you felt like playing something else – that's something I don't feel with a lot of piano players. It's really quite engaging. I guess that's another reason people focus in on him. He makes them hone in [sic]."

Bands and personnel

Jamal typically plays with a bassist and drummer: his current trio is with bassist Reginald Veal and drummer Herlin Riley. He has also performed with percussionist Manolo Badrena. Jamal has recorded with the voices of the Howard A. Roberts Chorale on The Bright, the Blue and the Beautiful and Cry Young; with vibraphonist Gary Burton on In Concert; with brass, reeds, and strings celebrating his hometown of Pittsburgh; with The Assai Quartet; and with saxophonist George Coleman on the album The Essence.

Awards and honors

1959: Entertainment Award, Pittsburgh Junior Chamber of Commerce

1980: Distinguished Service Award, City of Washington D.C., Anacostia Neighborhood Museum, Smithsonian Institution

1981: Nomination, Best R&B Instrumental Performance ("You're Welcome", "Stop on By"), NARAS

1986: Mellon Jazz Festival Salutes Ahmad Jamal, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

1987: Honorary Membership, Philippines Jazz Foundation

1994: American Jazz Masters award, National Endowment for the Arts

2001: Arts & Culture Recognition Award, National Coalition of 100 Black Women

2001: Kelly-Strayhorn Gallery of Stars, for Achievements as Pianist and Composer, East Liberty Quarter Chamber of Commerce

2003: American Jazz Hall of Fame, New Jersey Jazz Society

2003: Gold Medallion, Steinway & Sons 150 Years Celebration (1853–2003)

2007: Living Jazz Legend, Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

2007: Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, French government

2011: Down Beat Hall of Fame, 76th Readers Poll

2015: Honorary Doctorate of Music, The New England Conservatory

Discography

As leader

1951: Ahmad's Blues (Okeh)

1955: Ahmad Jamal Plays (Parrot) – also released as Chamber Music of the New Jazz (Argo)

1955: The Ahmad Jamal Trio (Epic)

1956: Count 'Em 88 (Argo)

1958: At the Pershing: But Not for Me (Argo)

1958: At the Pershing, Vol. 2 (Argo)

1958: Ahmad Jamal Trio Volume IV (Argo)

1958: Portfolio of Ahmad Jamal (Argo)

1959: The Piano Scene of Ahmad Jamal (Epic)

1959: Jamal at the Penthouse (Argo)

1960: Happy Moods (Argo)

1960: Listen to the Ahmad Jamal Quintet (Argo)

1961: All of You (Argo)

1961: Ahmad Jamal's Alhambra (Argo)

1962: Ahmad Jamal at the Blackhawk (Argo)

1962: Macanudo (Argo)

1963: Poinciana (Argo)

1964: Naked City Theme (Argo)

1965: The Roar of the Greasepaint (Argo)

1965: Extensions (Argo)

1966: Rhapsody (Cadet)

1966: Heat Wave (Cadet)

1967: Cry Young (Cadet)

1968: The Bright, the Blue and the Beautiful (Cadet)

1968: Tranquility (ABC)

1968: Ahmad Jamal at the Top: Poinciana Revisited (Impulse!)

1970: The Awakening (Impulse!)

1971: Freeflight (Impulse!)

1972: Outertimeinnerspace (Impulse!)

1973: Ahmad Jamal '73 (20th Century)

1974: Jamalca (20th Century)

1974: Jamal Plays Jamal (20th Century)

1975: Genetic Walk (20th Century)

1976: Steppin' Out with a Dream (20th Century)

1976: Recorded Live at Oil Can Harry's (Catalyst)

1978: One (20th Century)

1980: Intervals (20th Century)

1980: Live at Bubba's (Who's Who in Jazz)

1980: Night Song (Motown)

1981: In Concert (Personal Choice Records)

1982: American Classical Music (Shubra)

1985: Digital Works (Atlantic)

1985: Live at the Montreal Jazz Festival 1985 (Atlantic)

1986: Rossiter Road (Atlantic)

1987: Crystal (Atlantic)

1989: Pittsburgh (Atlantic)

1992: Live in Paris 1992 (Birdology)

1992: Chicago Revisited (Telarc)

1994: I Remember Duke, Hoagy & Strayhorn (Telarc)

1994: Ahmad Jamal with The Assai Quartet (Roesch)

1994: Ahmad Jamal at Home (Roesch)

1995: The Essence Part One (Birdology)

1995: Big Byrd: The Essence Part 2 (Birdology)

1996: Live in Paris 1996 (Birdology)

1997: Nature: The Essence Part Three (Birdology)

2000: Picture Perfect

2001: Ahmad Jamal à l'Olympia

2003: In Search of Momentum

2005: After Fajr

2008: It's Magic

2008: Poinciana – One Night Only

2009: A Quiet Time

2012: Blue Moon (Jazzbook)

2013: Saturday Morning (Jazzbook)

2014: Ahmad Jamal featuring Yusef Lateef, Live at L'Olympia. 2012 — 2 CDs/1 DVD (Jazzbook/Bose/Jazz Village)

2017: Marseille (Jazz Village)

Compilations

1967: Standard Eyes (Cadet)

1972: Inspiration (Cadet)

1974: Re-evaluations: The Impulse! Years (Impulse!)

1980: The Best of Ahmad Jamal (20th Century)

1998: Ahmad Jamal 1956–66 Recordings

1998: Cross Country Tour 1958–1961 (GRP/Chess)

2005: The Legendary Okeh & Epic Recordings (1951–1955) (Columbia Legacy)

2007: Complete Live at the Pershing Lounge 1958 (Gambit)

2007: Complete Live at the Spotlite Club 1958 (Gambit)

As sideman

With Ray Brown

Some of My Best Friends Are...The Piano Players (Telarc, 1994)

With Shirley Horn

May the Music Never End (Verve, 2003)

Wikipedia

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Chemical Romance – The Black Parade

Let me preface this My Chemical Romance retrospective by stating that they are my favorite band, and I still hold The Black Parade as one of my top-5 favorite albums ever recorded. Throughout My Chemical Romance’s career, I was astounded by their rise to fame, and having seen them go as the first opening band on tour with The Used, to headlining stadiums by the time The Black Parade reached its heights, and I have marveled at the lore and theatrics surrounding my favorite artist. The Black Parade was always an album that I kept coming back to when it first came out on October 24, 2006, and it still hits me hard every time I revisit this modern classic. Boiling down to the story of a cancer patient to the closing lyrics of “I am not afraid to keep on living,” I am bold enough to say that I found this album to be perfect from first listen, to now today as I re-listen to it again. In a lot of ways, My Chemical Romance were on a collision course for making this classic album as front-man Gerard Way mentioned in several interviews that he was always planning on make this LP from the start of the incarnation of the band. In some ways, this album killed My Chemical Romance as they put every drop of blood and sweat into creating this record, and even the group themselves initially saw this as the closing chapter to the band. However, what came after the mammoth success of The Black Parade was a scrapped album (to later be released, called Conventional Weapons) to the reinvention of the artist as the Killjoys on Danger Days, to the last recording we were left with on an aborted project called “Fake Your Death.” These events only added to allure and mystique surrounding The Black Parade. From the opening notes of a hospital machine quietly beeping to a flat-line on the introductory track “The End,” everything just seemed to be fully thought out and worked with the vision of this extraordinary group of musicians. When Way sings, “Now come one, come all to this tragic affair/Wipe off that makeup, what’s in is despair,” you are immediately transported to a world inside the five of the bandmates’ heads of a cancer patient living out their last moments. “Dead!” follows this track with an extremely up-tempo pace and rocks like The Ramones on steroids. On the chorus, Way sings, “Have you heard the news that you’re dead?/No one ever had much nice to say/I think they never liked you anyway/Oh, take me from the hospital bed/Wouldn’t it be grand? It ain’t exactly what you planned./And wouldn’t it be great if we were dead?” and it’s almost as if he is finding the silver lining in a life ending to a terrible disease such as cancer. The dual-guitar work of Ray Toro and Frank Iero is at its most potent on songs such as this one, and bassist Mikey Way keeps up with the duo as mentioned above’s frenetic pace. The underrated musician in all of this work of art is the drumming of Bob Bryar, who was let go shortly after the touring cycle wrapped on this record. Bryar’s fills and energy throughout the disc is nothing short of remarkable, and he adds an intricate layer to the story of the record. The next song, is arguably one of the best songs MCR had ever written in “This Is How I Disappear.” From its double-edged sword guitar attack to the somber lyrics of Way scripting out the journey of The Patient in the story, nothing comes off as cheesy or cabaret. Instead, everything clicks at just the right point and time. My favorite moment, in particular, is the bridge where Way sings, “Can you hear me cry out to you?/Words I thought I’d choke on figure out/I’m really not so with you anymore/I’m just a ghost/So I can’t hurt you anymore.” The simplicity of the lyrics to the complexity of what the guitars were doing made this a truly beautiful musical moment for the group, and solidified my pick as album of the year in 2006. “The Sharpest Lives” is a certified killer cut of a track and features some of the best guitar work of Toro’s and Iero’s career to date. Seeing this song performed live just exploded on the chorus of, “Give me a shot to remember/And you can take all the pain away from me/A kiss and I will surrender/The sharpest lives are the deadliest to lead,” and allowed me to personally gain the courage to sing in my band at a later date. It was the energy that I felt from their songs like this that truly made me understand when fans would claim, “Their music saved my life.” MCR may not have directly “saved” me, but it did give me a shit-ton of confidence to feel like I could take on all doubters if I followed a similar path as my favorite front-man. The album itself hits its crescendo and stride on the first single, “Welcome to the Black Parade.” From the gut-wrenching first notes on a piano to the call-to-arms lyrics of Way gaining every misplaced or forgotten kid to join him in the fictional parade, My Chemical Romance hit this one to the moon and back. After the first few opening lines lead into the punk rock verses of the meat of the song, they quickly bleed into one of the more anthemic choruses of my generation where Way sings, “We’ll carry on, we’ll carry on/And though you’re dead and gone believe me/Your memory will carry on/We’ll carry on/And in my heart I can’t contain it/The anthem won’t explain it.” It’s on brilliant choruses such as this one as to why this band hit such an incredible high with The Black Parade. There was simply going to be no way of containing this band’s popularity with certified smash singles like this one. “I Don’t Love You” reminded me a bit of a brit-pop rock band donned in all black clothing hitting all the right notes and moments on a heartfelt ballad. The music video for this track abandoned much of the marching band garb that the fans had grown accustomed to over this album cycle and delivered a quick re-imagining of what My Chemical Romance could do and become. As I mentioned before, Bob Bryar really gets forgotten as an underrated player in the parade, but his chops are what drives songs such as “House of Wolves.” Way’s shrieking in between the cabaret-esque verses come off as playful and fun and don’t seem forced at all from a front-man with an affinity for stealing the show. However, this track clearly gets Bryar to take over, and several key fills help drive this song home. Next up, the heart-wrenching piano and vocal-driven “Cancer,” which Way mentioned in several interviews as being one of the more important songs on the record, and in the totality of the My Chemical Romance project. The beauty of this track comes from its simplicity and features some of the best vocal delivery in Way’s career. This was a song that I didn’t know that MCR was capable of making at this stage in their career, but damn am I glad that they were able to pull it off. “Mama” sounds like a show-tune drenched in emo lore and despair, and even features Liza Minnelli’s vocals towards the bridge of the song. The song is structured around the story of the character “Mother War” as Way responds to Minelli’s earnest vocals with, “But there’s shit that I’ve done with this fuck of a gun/You would cry out your eyes all along.” All of these elements built into this song would be difficult for the average band to pull off. Lucky for us, My Chemical Romance were not an “average band;” instead they became almost super-human on their landmark LP. “Sleep” starts with some actual recordings of Way describing his night terrors during the recording process of The Black Parade, and is a clever way of introducing a killer song such as this. The crescendos in this particular song are some of the most powerful moments you will find in our scene still today, and you can tell that the band hit several key chords with their performance on this larger than life song. “Teenagers” was one song that I originally thought didn’t belong in the fold of the Black Parade-era since it sounded more like a track that would have fit better on Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge. However, now I can’t even imagine this record without this brilliant single, that features some of the most dangerous lyrical content of Way’s career when he sings, “The boys and girls in the clique/The awful names that they stick/You’re never gonna fit in much, kid/But if you’re troubled and hurt/What you got under your shirt/Will make them pay for the things that they did.” In the days of school shootings making us almost numb, due to the vast number over the past ten years or so, this was a lyrical line that could’ve derailed some of the success that MCR had due to the possible lack of sensitivity to the topic. In fact, the music video release was also delayed due to another senseless tragedy that happened around that time. Yet, My Chemical Romance was able to release this as one of their more popular singles from this record and their catalog in general. The ending of The Black Parade record features a great one-two punch of one of my most cherished My Chem-songs in “Disenchanted” and the blazing “Famous Last Words.” Starting with the former, I was incredibly blown away by the production of Rob Cavallo on this song in particular, since he made this somber track shine in so many unique ways. From the delicate opening to the first major hook of, “It was the roar of the crowd that gave me heartache to sing,” everything is pretty damn near perfect. My favorite moment of this song is the restraint that the entire band is able to showcase, as they could’ve done a huge build-up much like the aforementioned “Mama,” yet knowing that they had already followed that formula, they chose to blaze a new path forward on a larger than life emo power ballad. “Famous Last Words,” on the other hand, is just a free-flowing hard rock single that was destined for prime time right from the get-go. With the closing word of “I am not afraid to keep on living/I am not afraid to walk this world alone/Honey, if you stay I’ll be forgiven/Nothing you can say can stop me going home,” Way almost single-handedly gave all of those kids out there struggling for meaning in their own lives a reason to press on and realize that things do get better. With an ending like that, it’s hard not to get just as excited about listening to this record again from front to back, as MCR intended. This LP will undoubtedly continue to stand the test of time in our scene as one of the most critical records in punk, emo, and rock in general. The Black Parade may be “dead,” but its memory certainly carries on. --- Please consider supporting us so we can keep bringing you stories like this one. ◎ https://chorus.fm/review/retrospective/my-chemical-romance-the-black-parade/

0 notes