#this has been rattling around in my head since minneapolis

Text

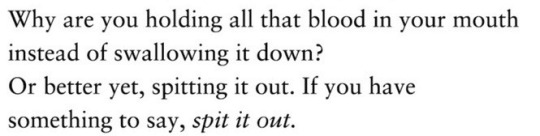

Blood Runs Thicker Than Water (But Both Feel the Same When Your Eyes are Closed)

Fluor Astrodath & Elegy Jones

#for the girls with teeth and horns and so much love to give it hurts#who do the wrong things for the right reasons#who are trying so hard all the goddamn time#this has been rattling around in my head since minneapolis#and it flew out of me in a case of creative zoomies#Fluor Astrodath#Elegy Jones#DMDC#web weaving

10 notes

·

View notes

Link

“Asian Lives Matter.”

Those three words — spoken loudly and emphatically by a Black pastor — moved Hyepin Im to tears.

“I felt chills going down my spine,” recalled Im, who leads Faith and Community Empowerment, a nonprofit based in Los Angeles’ Koreatown, which works to connect Asian American faith leaders with the community at large. “I was so grateful. I’ve waited a long time to hear this.”

Im and the Rev. Mark Whitlock, who spoke those words, have had a professional relationship and a personal friendship that has spanned three decades. Whitlock, a longtime Orange County pastor, now leads one of the nation’s largest Black congregations at the Reid Temple in Maryland. He gave a toast at Im’s wedding

Despite that connection, they said, speaking openly about lingering tensions between their respective communities was uncomfortable. It remained a chasm too painful to bridge until March 16, when a gunman opened fire in three Atlanta-area spas killing eight people, six of whom were Asian women.

That incident motivated Whitlock to reach out to Im and start the conversation afresh, Whitlock said.

“The reality is that Asian and Black communities in America have a lot more in common than in contrast,” he said. “We both deal with the evils of white supremacy. We both deal with systemic racism, economic challenges and losing jobs because of the color of our skin.”

Their candid conversations have now expanded to include other faith leaders in Southern California and beyond. Though efforts to build solidarity between Black and Asian communities are not new, there’s an urgency to the work after the past year — the racial reckoning that followed the murder of George Floyd compounded by the disproportionate decimation of communities of color by the coronavirus pandemic and an unprecedented surge in anti-Asian hate crimes.

The discussions have been thought-provoking, and the participants vulnerable, honest and empathetic, Im said, giving her hope the work will lead to lasting, fruitful partnerships between members of both communities.

Hyepin Im, left, director of Faith and Community Empowerment along with Bishop Kenneth Ulmer as a group of faith leaders from Southern California are leading a partnership between Black and Asian faith communities on a national level, after a number of recent high-profile videos that showed Black people committing violent hate crimes against Asian Americans. Instead of pitting these two communities against one another, this group of faith leaders has started a conversation and dialogue between the two communities with the hope for healing and solidarity in Los Angeles on Friday, July 9, 2021. (Photo by Keith Birmingham, Pasadena Star-News/ SCNG)

History of unity and tension

Black-Asian solidarity has a long history in the United States. In 1869, civil rights icon Frederick Douglass gave a speech taking a stand against restricting Chinese and Japanese migration to the United States. At the turn of the 20th century, African American figures like Henry M. Turner and Ida B. Wells spoke out for Filipino freedom fighters and against American colonization in the Philippines.

In the early 1960s, an unlikely bond between Malcolm X and Yuri Kochiyama, a Japanese human rights activist, helped each other develop global perspectives on human rights.

And in 1982, Black civil rights leaders including the Rev. Jesse Jackson joined forces with Asian American activists to demand justice for Vincent Chin, a Chinese American man who was mistaken for a Japanese man and beaten to death in Detroit by two White autoworkers who blamed Japan for the decline of the U.S. automotive market.

These moments of unity, however, have been punctuated by conflict.

Tensions between the two communities boiled over in early 1991 in Los Angeles after convenience store owner Soon Ja Du, a Korean immigrant, shot to death an African American customer, 15-year-old Latasha Harlins. Evidence in that case showed Du had no reason to shoot the teen from behind as she attempted to leave the store. Du was sentenced to 10 years in state prison, but the sentence was suspended and she was instead placed on five years probation with 400 hours of community service, a $500 restitution and funeral expenses.

The lingering anger and resentment in the Black community over Du’s light sentence exploded a year later, in April 1992, after a jury acquitted four Los Angeles Police Department officers charged with the use of excessive force in the arrest and beating of Rodney King. Widespread riots in Los Angeles resulted in more than 50 deaths and 1,000 injuries and caused about $1 billion in property damage, approximately half of which was sustained by Korean-owned businesses. Those tensions have since eased, and over the past year, there have been renewed efforts to build solidarity between the two communities, largely led by faith leaders and grassroots activists.

After the May 2020 death of George Floyd, a Black man, at the hands of a White police officer in Minneapolis, Asian Americans along with White people, Latinos and other communities of color rallied around the Black Lives Matter movement and the racial reckoning that followed. According to a survey of Asian Americans conducted by AAPI Data, about 67% of Korean Americans, 59% of Asian Indians and 51% of Japanese Americans said they believe Black people face “a lot” of discrimination “in our society today.”

Related links

Asian Americans in Southern California rattled by fatal Atlanta spa shootings

Surge in anti-Asian hate crimes raises fears in Southern California

In combating anti-Asian hate incidents, a growing debate in Southern California over law enforcement’s role

In the wake of George Floyd’s death, many struggle to begin racial reconciliation

When black lives matter to everyone: A new generation leads call for change, sparked by the killing of George Floyd

Healing the divisions

The surge in anti-Asian hate illustrates the pain that Black and Asian communities have in common, said Bishop Kenneth Ulmer, senior pastor at Faithful Central Bible Church in Inglewood. High-profile videos of Black people attacking elderly Asians have led some observers to reduce anti-Asian violence to the trope of Black-Asian conflict that was also perpetrated during the LA riots, he said.

“The truth is there has been no real, meaningful relationship between Black and Asian communities,” he said. “But now, as we see our Asian brothers and sisters being attacked, we’re simply saying: Wow, you too. We’ve seen pictures of Asian men and women minding their business, walking on the street and getting attacked. As Black people, we know what that’s like.”

The first step toward achieving solidarity is to start the conversation, Ulmer said.

“So long as we don’t do that, Koreatown is Koreatown and Watts is Watts,” he said. “For us, the encouragement for the conversation is the common ground of our faith and the recognition that it transcends color, ethnicity, language and neighborhood. Faith is the gathering place. The challenge then is how we go from here to the individual directions we take when we leave that common ground. How can we effect significant change and progress?”

For some faith leaders, efforts to build relationships between communities are not new. Pastor Dave Gibbons, who heads Newsong Church in Santa Ana, said his multi-ethnic congregation has had Black people in leadership for many years now and even planted a predominantly African American church in Culver City more than 20 years ago. Yet, Gibbons said, he has always been careful not to be political. Floyd’s death changed that, he said.

“I felt I needed to say something and I decided to take a stand,” Gibbons said. “I’ve always stood up for the Black community and for anti-racism, but I felt what I say needs to be clearer, more pronounced and articulated.”

Pastor Dave Gibbons, left, of the Newsong Church and Darryl Brumfield, right, a teaching pastor at the church and an advisory board member, stand in the sanctuary on Wednesday, June 30, 2021, in Santa Ana. (Photo by Mark Rightmire, Orange County Register/SCNG)

Reconciliation is part of Newsong’s DNA, said Gibbons, who was born to a Korean mother and an Irish American father. Feeling pain is part of the hard work of reconciliation, he said.

“You have to let people sit in that pain and listen to one another,” Gibbons said. We need to step into the tension as a listener, a learner and a lover.”

Lessons in diversity and stereotypes

For Darryl Brumfield, a teaching pastor at Newsong who has enjoyed a 20-year friendship with Gibbons, a logical first step is to acknowledge that “white systemic racism was not an injustice on any one minority, but on all minorities.”

Brumfield is an African American man who grew up in Compton in the 1950s, in a time when White people were moving out of the city and Asians moving in. Asians were mostly store owners and Black people were their customers, he recalled.

As a child, the only view of “Asian life” he had was through his neighbor’s window. He saw the family eat together. The children studied as Brumfield watched television and his mother would ask him: “Why can’t you be more like those Asian kids and pick up your books?”

“I stereotyped them as the model minority too, which I learned later, was not right,” Brumfield said. “I was the same as people who marginalized and looked at me as one-dimensional. I’ve learned about the rich diversity within the Asian community and how there are connections and walls within that community.”

This is true for African Americans as well, Brumfield said. His wife is a Black woman from Costa Rica. His brother-in-law is from Nigeria and his best friend is from St. Lucia, an island in the Caribbean.

“People might just see four Black people at the table,” Brumfield said. “But they all have different stories. When I came to Newsong, I saw that same rich diversity in the Asian community.”

While a young Brumfield worked in an Asian-owned store in Compton, the Rev. Walter Kim worked a summer job in high school at his uncle’s clothing store in New York City’s Times Square where most of the employees and clientele were African American.

“That was a formative experience for me because I learned about some of the challenges that African Americans faced historically, which we weren’t always privy to in the Korean American world,” said Kim, president of the National Association of Evangelicals. “I learned not from a history book, but from a community that was vibrant, active and engaged.”

Kim has been engaged in conversations recently with groups of faith leaders convened by Im and Whitlock. He said he has learned from this group that it is pain that first draws Black people and Asians together.

“It’s powerful to see the depth of hurt and suspicion and wariness of the Black community toward Asian Americans,” he said. “These are not isolated incidents, but numerous persistent conflicts. It’s a hard thing to hear, but also so important to hear.”

The friendships he is developing through this group are precious because their honesty is refreshing, Kim said. He has been struck by the impact the “model minority myth” has had on Black Americans and the education system as a whole.

“It’s one thing to read about it in a newspaper or journal,” he said. “But to actually hear that from a Black person who experienced disadvantage because they were compared with Asians — that was very painful. It’s no longer a statistic for me. It’s a story. It’s real now.”

Challenges and pitfalls

Im’s presentation to a group of Black faith leaders about disadvantages that Asian Americans face in terms of access to health care, education, jobs and housing was “eye-opening,” said Barbara Williams-Skinner, CEO and co-founder of the Baltimore-based Skinner Leadership Institute, which trains faith leaders.

“Organizations should start building (solidarity) into their priorities,” she said. “It wasn’t a priority for us before, but it is now. We need to reach people where they are so we can stop hating and start connecting. The alienation is real, but we have a lot more to gain by coming together than we do by continuing with that alienation. We need combined voices articulating the need for solidarity. We can start by getting our churches across the racial divide.”

It is important to focus these efforts at solidarity on mutual understanding so it is sustainable, said Karthick Ramakrishnan, founder of AAPI Data and director of UC Riverside’s Center for Social Innovation.

“It’s not just about focusing on areas of common interest, but actually making change in communities,” he said. “For example, when people hire in ethnic enclave economies they tend to hire family members or friends. They could think about hiring local. Building solidarity is not just about lowering prejudice, but to figure out what the economic and policy interests are, and to support that.”

Also, if part of what brought communities together is crisis, they may not stay together once the crisis recedes, Ramakrishnan said.

“That’s where leadership and funding play a role,” he said. “It’s hard to keep communities together if there is no funding to staff that solidarity.”

Learning each other’s history and stories is a crucial part of understanding each other, said Jemar Tisby, deputy director of narrative and advocacy at The Center for Anti Racist Research housed in Boston University and led by Ibram X. Kendi. One of the pitfalls in this type of work is the tendency to collapse distinct narratives into a single narrative, Tisby said.

“People of Asian descent have their own stories and history when it comes to racial oppression, triumph and struggles,” he said. “Similarly, (Black people) have our own story. We shouldn’t lose the specificity of each of our stories in an attempt to foster solidarity. The challenge is to maintain your unique history and identity while partnering with others.”

While Black people cannot claim to own all social movements, Tisby said, history shows that whenever Black people were able to make progress, other racial groups benefited as well.

“In the midst of long-overdue cooperation, we are never to forget that the main vector of division in this country is between Black and White,” he said. “This is not to say any other group is not important. But if you want to cut off the head of the snake, you have to address anti-Black racism.”

Related Articles

Professing Faith: Bible is filled with tales of spice

Professing Faith: Religious and social unrest followed the bubonic plague

Explainer: What is the Catholic Communion controversy?

Catholic bishops approve steps toward possible rebuke of Biden

San Bernardino diocese reopens churches to full capacity, without masks for vaccinated

Speaking up

Faith leaders’ voices can be particularly impactful in this push for understanding and solidarity because both Black and Asian communities have strong connections to their churches, Im said. In the Korean community alone, about 75% are churchgoers, she said.

“It’s powerful to hear Black leaders acknowledge for the first time that they may have overlooked other communities of color in the fight for social justice,” she said. “It’s been heartwarming to see such support from Black leaders who have used their voices to speak up for the Asian community.”

Im hopes this model of using dialogue and storytelling to build solidarity helps take the two communities further down the road.

“It’s not based on explaining away things saying it’s a cultural difference,” she said. “It’s about truly understanding that we’re all human beings and that we’re on the same team. My hope is that faith leaders who have the power to influence can also let go of their preconceived notions and completely engage in this effort.”

Whitlock said Black faith leaders must have the courage to say those three words that moved his friend, Im, to tears.

“Asian lives matter, and they matter on their own,” he said. “I will acknowledge that I took my Asian brothers and sisters for granted. I was floored to hear (Im) talk about challenges they had with home ownership, unemployment and criminal justice. I would not have been as insensitive as I was, had I known they were being treated as badly as we are. I saw Asians as White people before. All of a sudden, now, I see the truth.”

Asian Americans are not the model minority, but they are an “invisible community,” Whitlock said.

“We must see their pain, anxiety, tears and depression,” he said. “I had to criticize myself because I was sweeping these issues under the rug. We must talk about it and share our own biases. We must see we have more in common than not. Silence is not acceptable.”

-on July 09, 2021 at 10:52AM by Deepa Bharath

1 note

·

View note