#tony galento

Text

Cavendish Street, Manchester.

#coordination#layers#ombre#split tone#hair#two tone#tony galento#long skirt#vintage#leather jacket#white lace#scottish#fair isle#socks#marshall#headphone#s#Manchester#Manchester School of Art#ootd#wiwt#street style#Manco

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

We need to bring back the old timey nickname formulas.

“City of origin + alliterative noun” is always a solid choice. Cincinnati Cobra, Garfield Gunner, Louisville Lip, The Nigerian Nightmare, etc.

Mix in some fun ones like Michael “Second To” Nunn, The Hispanic Causing Panic, etc. Pretty Boy Floyd >>>>>> Money too btw.

Fighters are waaay bigger today than in the 40s and 50s. Why have we not had a really fat fighter go by “Three-Ton”, surpassing Tony Galento?

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

There's no bottom to it.

The plan to leave. Who didn't have one? It evolves as torturously as the wills of propertied people, rewrites and revisions every six months. I'll go stay with this one; no, I'll go stay with that one; this hotel, that hotel, this woman, that woman, two different woemn, with no women, no woman ever again! I'll open a secret account, hock the ring, sell the bonds. . . . Then they get to be sixty, sixty-five, seventy, and what difference does it make anymore? They're going to leave all right, but this time they're really going to leave. For some people this is the best thing to be said for death: finally out of the marriage. And without having to wind up in a hotel. Without having to live through those miserable Sundays alone in a hotel. It's the Sundays that keep these couples together. As if Sundays alone could be any worse.

No, this is not a good marriage. You wouldn't be far off guessing that much no matter whose table you happened to be eating at, but Sabbath could tell from that laugh—if not from the fact that he was being permitted to play footsie with her only ten minutes into the meal—that something had turned out wrong. In her laugh was the recognition that she was no longer in charge of the forces at work. In her laugh was the admission of her captivity: to Norman, to menopause, to work, to aging, to everything that could only deteriorate further. Nothing unforeseen that happens is likely ever again to be going to be good. What is more, Death is over in its corner doing deep knee bends and one day soon will leap across the ring at her as mercilessly as it leaped upon Drenka—because even though she's at her heaviest ever, weighing in at around one thirty-five, one forty, Death is Two-Ton Tony Galento and Man Mountain Dean. The laugh said that everything had shifted on her while her back was turned, while she was facing the other way, the right way, her arms open wide to the dynamic admixture of demands and delights that had been the daily bread of her thirties and forties, to all that assiduous activity, all the extravagant, holidaylike living—so inexhaustibly busy. . . with the result that in no more time than it took for the Cowans to cross the ocean on the Concorde for a long weekend in Paris, she was fifty-five and seared with hot flashes, and her daughter's was now the female form exuding the magnetic currents. The laugh said that she was sick of staying, sick of plotting leaving, sick of unsatisfied dreams, sick of satisfied dreams, sick of adapting, sick of not adapting, sick of just about everything except existing. Exulting in existing while being sick of everything—that's what was in that laugh! A semidefeated, semiamused, semiaggrieved, semiamazed, seminegative, hilarious big laugh. He liked her, liked her enormously. Probably just as insufferable a mate as he was. He could discern in her, whenever her husband spoke, the desire to be just a little cruel to Norman, saw her sneering at the best of him, at the very best things in him. If you don't go crazy because of your husband's vices, you go crazy because of his virtues. He's on Prozac because he can't win. Everything is leaving her except for her behind, which her wardrobe informs her is broadening by the season—and except for this steadfast prince of a man marked by reasonableness and ethical obligation the way others are scarred by insanity or illness. Sabbath understood her state of mind, her state of life, her state of suffering: dusk is descending, and sex, our greatest luxury, is racing away at tremendous speed, everything is racing off at a tremendous speed and you wonder at your folly in having ever turned down a single squalid fuck. You'd give your right arm for one if you are a babe like this. It's not unlike the Great Depression, not unlike going broke after years of raking it in. "Nothing unforeseen that happens," the hot flashes inform her, "is likely ever again to be going to be good." Hot flashes mockingly mimicking the sexual ecstasies. Dipped, she is, in the very fire of fleeting time. Aging seventeen days for every seventeen seconds in the furnace. He clocked her on Morty's Benrus. Seventeen seconds of menopause oozing out all over her face. You could baste her in it. And the it just stops like a tap that's been shut. But while she is in it, he can see how it seems to her that there's no bottom to it—that this time they're out to cook her like Joan of Arc.

—Philip Roth, Sabbath's Theater

0 notes

Photo

Joe Louis boxes Tony Galento Many years ago, the famous boxer Joe Louis was in a title bout against Tony Galento. Joe Louis’ trainer told him, "Don’t get up until the count of nine.

0 notes

Photo

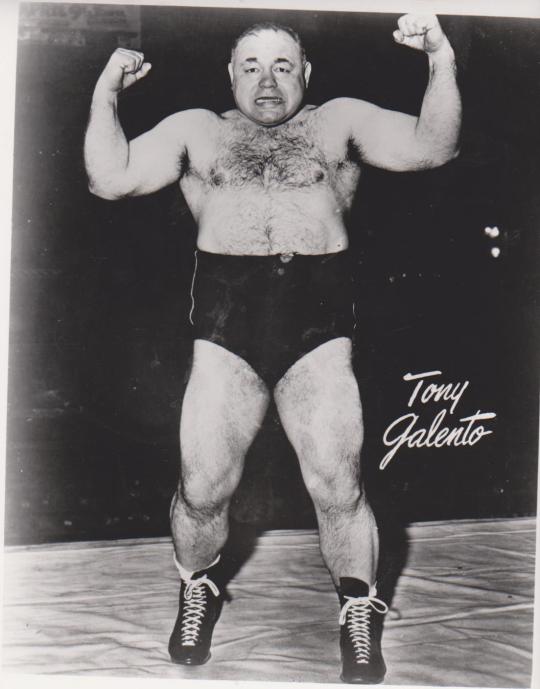

Domenico Antonio Galento (1910 - 1979)

Peso massimo, sdegnoso combattente italo americano

Fiero esegeta dell’iconografia classica del pugile suonato

Disputò un totale di 114 incontri con un record personale di 80 vittorie per Ko, ma queste sono ordinarie e consuete cose, per tale, pittoresco, uomo di grande affare:

Lottatore pazzo, si batteva coi canguri e con gli orsi, per gran fama, pecunia e per il diletto degli astanti e, di certo, per il suo istesso.

Durante una disfida, con competenza ostinata, strangolò un orso da 250 libbre e fu sì contento, d'animo come di corpo.

Per promozione di se, un tempo, Galento volle combattere con un gorilla, per dar prova di una certa possanza. Alcuni esperti di biologia marina consigliarono, nondimeno, di confrontarsi con una gigantesca piovra.

L'incontro si svolse in apnea in una gran vasca, in cui Galento, ardito e soave, strangolò il cefalopode tra gli applausi, le grida e gran letizia.

Di mestiere uomo di fatica in rosticceria ("The Nut Club", nel New Jersey), finiva di consegnare le fusaie nottetempo, alle 2 antemeridiane, e poscia andava agli incontri di boxe, rigorosamente ubriaco e pigramente, come svogliato, perennemente in ritardo. (Fu detto "Due tonnellate", per le savie parole che tuttavia utilizzava per giustificar le sue ragioni: "Scusate, dovevo prima consegnare due tonnellate in colonne di ghiaccio", o a seconda, in tordi grassi, tortorelle, lasagne maritate ed altre finissime vivande.)

Contra i rivali usava l’arma della puzza, odor cattivo.

Non si lavava a bella posta, a scopo di ripugnare.

Gli avversari, in tale fetor di tenebra, attoniti tacevano, senza colpo ferire, come oppressi dal sonno.

Il noto pugile Maximilian Adelbert Baer (campione del mondo dei pesi massimi dal 14 giugno 1934 al 13 giugno 1935), disse di lui: "Puzzava come una vasca piena di liquore e tonno morto"

Il buon Galento era alto un metro e settantasette, ma amava gravare di molto oltre il suo peso forma, a mò di drammatica zavorra, fino a "sfiorare le 240 libbre" (New York Times, 23 Luglio 1979)

A tale proposito scelse saggiamente una severa e disciplinata dieta, il cui pasto tipico consisteva in sei polli ed un contorno di spaghetti, leggermente bagnati da mezzo litro di vino rosso e birra, cautamente schiumati assieme nel torbido, come fango di lavatura di cenere.

"Tony era dedito a gozzoviglie pantagrueliche che non sospendeva nemmeno il giorno degli incontri"

Un giorno picchiò il suo allenatore, reo di avergli consigliato un cambio di passo alimentare.

Fiero ladro e rapace, era solito, prima di ogni competizione, introdursi nelle mense dei palazzetti sportivi, e nei privati ristori degli avversari, svuotando i paiuoli, mangiando tutte le zuppe, ingollando i liquori per poi fare, a sfregio, rumorosi venti, che dallo stomaco si mandan fuori per bocca.

Una volta, per scommessa, mangiò 52 hot dog prima di affrontare l'italiano peso massimo Arturo Carlo De Kuh.

Un poco sovraccarico, ebbe a commentare: "Dopo 52 hot dog mi sento un poco ottuso, potrò procedere al massimo per tre round"

Seppur fiacco e lento come la melassa, eliminò il triestino con un gancio sinistro proprio allo scadere del terzo round, per rifugiarsi tosto in rosticceria oltremodo a desinare.

Sofferente di cuore e malato di diabete, insolitamente perì di indigestion fatale

“Shakespeare? Mai sentito parlare di lui. È uno di quei pesi massimi stranieri? Se volete posso picchiarlo" (Tony Galento)

Sfrenato e dissoluto, soprastante, violento.

Uomo illustre, che a nominare con laude mi prodigo con foga

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Modern Screen, February 1940: Woeful and Wacky by John Franchey

Transcript of article:

Sad-eyed but full of tricks- that’s Mayor Mischa Auer

Those doleful eyes of Mischa Auer, so conspicuous by their contrast to the hilarious shenanigans he’s always pulling off, are no actor’s triumph. He deserves no credit. Life gave them to him. They mirror his personal history. They reflect war, work and woe.

In his last picture, “Destry Rides Again”, he set even the hard-bitten critics in the aisles with his buffooneries as a transplanted Cossack who had migrated without rhyme or reason to a western town where he undertook a spot of hoss-wrangling. A Russian cowboy he was, as fantastic as a séance of rug-cutting in a cathedral or Tony Galento in the role of a ballerina.

Funny? Of course. But ironic, too.

It so happens that Mischa Auer is a Russian expatriate, a scion of what he likes to call, with typical modesty, “the petty nobility.” And his real name is Mischa Simonowich Ounskowski. His father, a commander of a destroyer in the Imperial Russian fleet, went down with his ship in a skirmish with one of the Mikado’s men-of-war during the Russo-Japanese campaign.

He was four when his renowned grandfather, Leopold Auer, the outstanding violin virtuoso of this century and the teacher of Zimbalist, Elman and Heifetz, to name a few, took him under his wing. When a fiddle was thrust in his hands, he stared at it ruefully. He made a clean break of it. There just wasn’t the immortal urge within him, he told his great kinsman. Grandpa Auer took it very hard.

What he did have was a passion for the theatre. As a little shaver he used to haunt the back stages of the theatres at St. Petersburg, entranced with it all.

The Revolution broke with all its sudden fury and it became high time to think of self-preservation. Caught in the maelstrom, he was shipped with several hundred other boys of his age and social status to a forlorn town in Siberia, presumably to learn how to become a true Communist.

It was a miserable journey, four thousand miles across the steppes in coaches that offered only wooden benches on which to sleep. Once arrived at land’s end, they were dumped out and forgotten.

Here he discovered how relentless life can really be. Faced with starvation, he learned to ignore the proprieties. Together with his friends he formed a roving band equipped with knapsacks. They trudged from farmhouse to farmhouse begging, in the name of God’s mercy even a hard crust. It wasn’t easy. Poverty reigned over the whole countryside. When they couldn’t beg food, they stole it- just enough to keep themselves alive.

After two years, they were shuttled back to St. Petersburg. Some had perished. Mischa Auer had become a starveling gnome, and the mournful look had made its first appearance.

Worse misfortune was yet to dog him. Now the dread OGPU, the political secret service arm, outlawed all those suspected of having sympathetic leanings toward the old regime. The Auers were on the list scheduled for immediate liquidation. One jump ahead of arrest and oblivion, Auer and his mother fled. It was a heart-rending trek they made, mother and son, forging their way South to the Black Sea, fighting plague and hunger, and eventually reaching Constantinople then under the protection of the Union Jack.

Here his mother was attacked by typhus and died. And here she was buried in a Greek Orthodox cemetery overlooking the harbor. A boy of fifteen, he was now left to shift for himself. In time he beat his way into Italy where he hunted out a family friend who provided him with the address of grandfather Leopold, now in the United States. Soon help was on its way. The wanderer set sail for America, a wistful shadow of a boy who had compressed an eternity into his fifteen years.

Under his grandfather’s protection, he picked up the life thread. He was sent to the famous Ethical Culture School. His record here is less than average. He had no inclination for studies. His mind was alive only with dying. He could not escape the recollections of things he had seen and heard.

All concerned worked feverishly to salvage the shattered soul in the under-nourished body. It was slow work. But by the time he was seventeen, noticeable progress was apparent. Came the day when he remembered his former passion for the theatre. He decided to see what it had to offer him here in America

Not much, at first. But he persisted. Mere disinterest and rebuffs were nothing to him. He wouldn’t be downed. Finally Dudley Digges, just for his own amusement, presented him with a small role, that of an old man, in a mob scene.

This slight encouragement was enough to show him he was headed right. He worked up to stage manager, also under Digges. Then he landed the juvenile lead in Sudermann’s “Magda.” In due time the company landed in Hollywood. Here the movie bug bit him. He chucked overboard the legitimate stage.

If the stage was tough to crack, the movies were doubly tough. The studios wouldn’t even let him play an extra. Once, he will tell you, a director tossed him out of a Russian sequence because he didn’t look like a real Russian.

He did everything while waiting for the magnificoes to see the light. He even rounded up a bunch of musicians and leaded a jazz band, available for a modest fee for dances.

It was Director Frank Tuttle who discovered him. He thought the sad-eyed Russian was wonderful. In fact, he managed to find a spot for him in every one of his productions. Before long the melancholy one became a figure in the film colony. He got bids right and left but only when they needed despicable-looking villains who’d blackjack one-armed widows and swipe their pitiful savings.

In vain did he protest that his dish was comedy. No one seemed to care. Not until Gregory La Cava, assigned to direct “My Man Godfrey,” happened to recall some of Mischa’s high jinks at a party years before, in which he had hung from the chandeliers in the character of a gorilla. La Cava felt that maybe this identical insanity would bolster the Godfrey saga. He took a chance, gave Auer a try. The waif pulled out all the stops. The fans howled, and at long last he who got slapped was definitely in.

At thirty-four, wacky and woeful, Mischa Auer sits atop his own peculiar Olympus contemplating the world beneath. An inimitable harlequin, nevertheless he has a curiously humble philosophy about success. He simply figures he was lucky.

Regarding his acting talent, a gift which some critic has been bold enough to hail in print as “an incomparable genius for mirth and merriment in a minor key” he is more curious still. He regards Mischa Auer as a “ham.” His explanation is child-like, very brief and simple.

“I got some parts in shows and finally came to be a pretty good ham. There was nothing to it. In time I got out to Hollywood and eventually they went for my stuff. What I can do is just damned foolishness, but I’m crazy about pictures.”

Outside of adding a few pounds to his frame and shooting some over fourteen inches skyward (he is now six feet two) the years have brought little noticeable change to the boy who fled from Russia. Today he’s as mournful-looking as ever, a streamlined, rapid-talking, mad Hamlet who hides his thoughts deep inside of him.

For all this inferior gloom, the Auer is a geyser of gags, antics and mummery. On the set he’s a volcano whose humor literally stops the show. Cameramen, directors, script girls- one touch of Auer’s laughter makes the whole set kin. When he played with Baby Sandy in “Unexpected Father,” he had the little shaver gurgling all day, so much so that at night there was a strange wailing in B.S.’s nursery. She missed this wonderful buffoon.

No single individual is more liked in Hollywood than Auer. He’s the life of every gathering he attends, his baleful eyes providing such amazing counterpoint to the high jinks he’s always perpetrating. Photographers covering the swanky premieres at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood never tire of exploding their flash bulbs at him. Just to be a pal he’ll push a peanut down the block with his nose, or walk a tight rope dressed in a hooped skirt.

“All you have to do is ask the guy,” a picture-taking admirer of Mischa’s explains.

Hostesses implore him to come to their parties and fall on his neck out of gratitude when he departs. He never makes an entrance. Actually, it’s an invasion.

This general popularity is attested to by his political triumph of summer last. All of a sudden he up and ran for mayor of Universal City against Hugh Herbert and Joy Hodges. He pranced home the winner. Out of sportsmanship he made la Hodges the Chief of Police and then began worrying about funds to build a jail large enough to house the crime wave that was sure to result from this selection.

Being Alcalde of Universal City is his pride and joy. He loves talk of the Utopia he’s “going to make” of the little community. He bustles around sporting the most outlandish badge of office you ever saw. He’ll unbutton his coat at the drop of a hint so as to show it to people.

He’s the interviewers’ delight. He makes it his business to astonish them by hook or crook. He’ll put on a show, if he has to.

“Auer may never inspire the press, but he’ll never bore them,” he told a paragrapher.

Once when he was being interviewed he decided on the spur of the moment to ring up his grandmother, Mrs. Leopold Auer. She kept him on the phone for almost an hour, while he groaned in his helplessness. When another writer, a lady this time, burst in she almost jumped out of her girdle. There was Mischa lying under the desk, tie akimbo and feet sprawled over the radiator, and spouting Russian at his relative lickety-split. The reporters looked at each other in amazement and wondered when the man with the straight jacket was coming for his charge.

These same journalists get little information out of Mayor Auer. He’s too busy entertaining them. If he does do any serious talking, he steers the conversation into the channel of the camera art, his favorite hobby. Then, what has started out as an inspection of the Auer life and personality degenerates into a volcanic monologue on the respective merits of the different kinds of film, a new filter that’s just hit the market or, maybe, a nifty developing solution dreamed up by one of his cronies who has the same hobby.

The thought of an elf as a husband is inclined to take your breath away, but married he is. To a lovely non-actress, nee Norma Tillman. He has a son and heir named Anthony, of whom he never tires of talking. They’re pals, father and son. Every now and then he and Anthony take a long walk, climb atop a little green hill and there Auer pere chants wild Slavic songs to the accompaniment of a Russian balalaika.

At home he’s a housewife’s delight- ready to tackle anything from dish-washing to beating the rug, if need be. He’s designed the wall-paper for his present home and equipped it with knick-knacks of his own creation.

In matters of dress he’s as careful as a debutante dreaming of her coming-out party. Which is why he’s one of the slickest figures in any formal gathering. He loves evening dress. No one in Hollywood looks jauntier in a white tie.

His hobby may be cameras and picture-taking but his passion is restrained roistering with fellow members of the old regime- and Hollywood has many of them. He and his playmates assemble at regular intervals dressed to the hilt. They dine sumptuously and then begin to tell sad stories of the deaths of kings and princes. They toast the glory that was old Ray-shya far into the night. Tears flow like rain upon the town when these sentimentalists start to relive the olden days.

When it gets threeish, the man with the baleful eyes straightens himself to his stiffest, clicks his heels, and salutes and departs. Tomorrow is another day and somewhere on Universal lot Baby Sandy may be waiting for a camera rendezvous with her goofy parent.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

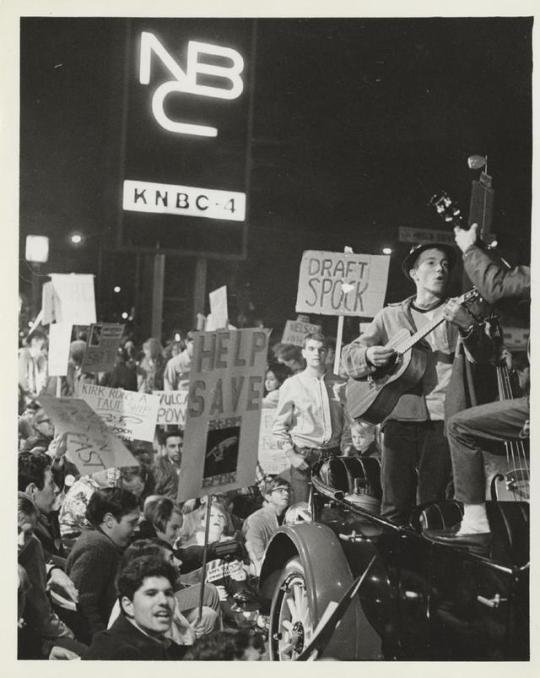

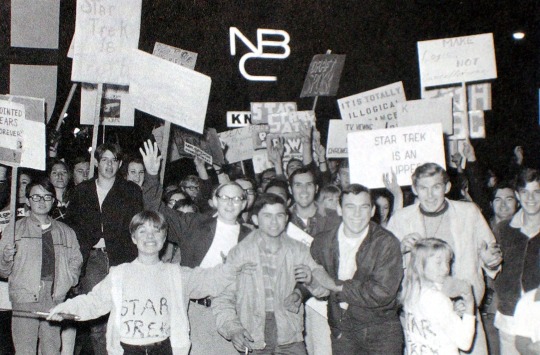

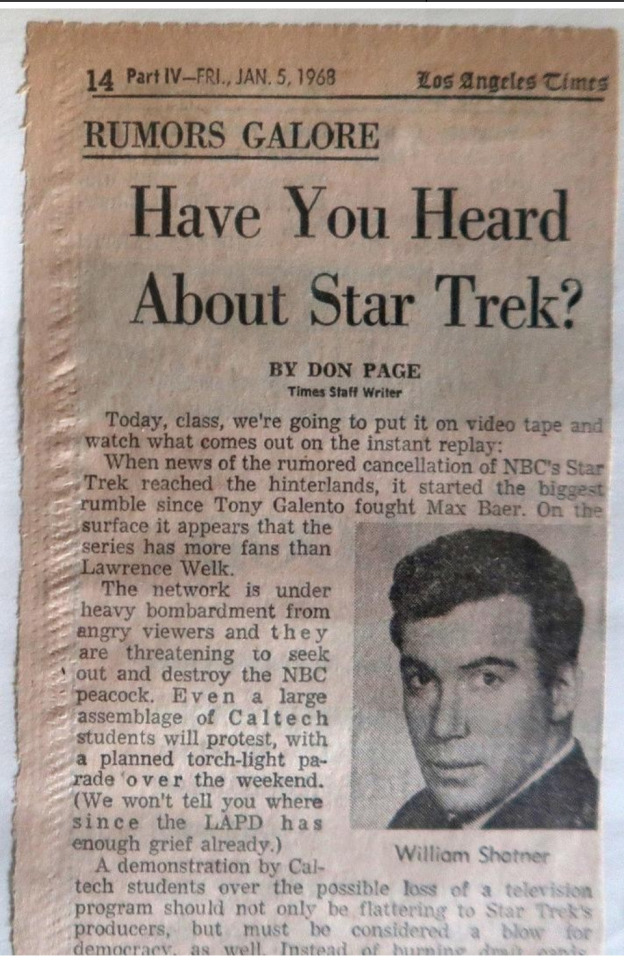

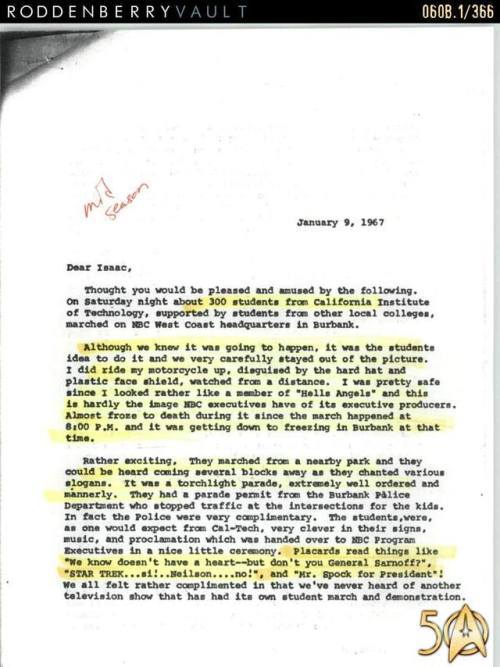

“When news of the rumored cancellation of NBC's Star Trek reached the hinterlands, it started the biggest rubble since Tony Galento fought Max Baer. On the surface it appears that the series has even more fans than Lawrence Welk."

Don Page, staff writer for the Los Angeles Times, 5 January 1968

Despite Harlan Ellison's part in the first letter writing campaign to save Star Trek for a second season (https://redshirtgal.tumblr.com/post/186615514377/when-star-trek-fans-read-about-the-letter-writing), there were definite rumblings around November 1967 that Star Trek was about to be cancelled for good this time. Letter writing campaigns led by Bjo and John Trimble and others began in late 1967 and carried into March of the following year.

However, there were also student protests that popped up in Burbank, San Francisco, and New York. The most famous one was organized by the Caltech "Save Star Trek" committee. On January 6, 1968 over 200 Caltech students carrying protest signs and torchlights and chanting some of the slogans you see in the photos began heading from their campus toward NBC's Burbank studios. Pasadena radio station KRLA carried hourly updates, which helped swell the crowd to over 700 people (numbers vary on this) as students from other Southern California college campuses joined in.

Once the students reached the NBC studio, a Caltech student dressed as Spock handed petitions with over 1,000 signatures to James Seaborne, an executive at NBC responsible for programming. As reporters from KRLA, Caltech's own student newspaper, and the Los Angeles Times took notes and snapped photos, the student representative told Mr. Seaborne that the crowd was but a small sample of the support Star Trek actually had from fans. He also mentioned that using the Nielsen ratings alone to decide Star Trek's fate would be a grievous error because, in his words, "Nielsen didn't ask us."

Roddenberry managed to make an impromptu appearance at the protest and later he along with James Doohan and writer David Gerrold met with members of the Save Star Trek committee to thank the students for their support. (Walter Koenig also dropped in on the protest but not the meeting afterward).

Similar student protests were held in other cities. Berkeley students demonstrated in front of the NBC station in San Francisco. Not to be outdone, students from MIT also brought their protest signs and chants to the NBC studios at Rockefeller Center in NYC. Newspapers all over the country mentioned these demonstrations along with the letter writing campaign in their entertainment sections.

Never before had student-led campaigns been organized to save a television show from cancellation. Which also is part of an interesting back-story. Who exactly organized these campaigns?

Let's back-track a bit. Herb Solow in Inside Star Trek recounts that one of their college interns working at NBC Burbank approached his boss in early January and told him the Save Star Trek committee had plans to picket the studio. At first, his boss was unimpressed because, as he told his intern, NBC had been picketed by a dozen people before. His intern informed him that this time there were going lots more than a dozen and that this was part of a national movement. By "national movement," did he mean this was connected to the Trimbles' letter writing campaign? Or was there a national movement of protests being organized behind the scenes? Possibly both.

Sometime before January, Gene had invited students from Catech to visit the studio and planted the idea that Star Trek would most likely be cancelled at the end of the second season. The students thought of a protest march which Roddenberry encouraged. An announcer at a local radio station who was also a fan began making announcements about the planned march, saying it would consist of students from many local colleges except for the University of Southern California. Which in turn resulted in USC having the second highest number turnout at the march. But how had this radio announcer known the march was planned? It seems he had gotten a call from the Star Trek offices giving him advance notice. And several newspapers wrote advance stories about the protests, including the Los Angeles Times (see above).

The boss of the student mentioned earlier was Hank Rieger. Shortly after his intern's warning, he received a call from someone at the Burbank Police Department informing him that a group of Caltech students had applied for a permit to march in front of the NBC studios. The officer evidently envisioned a march the size of the ones organized against Vietnam because he told Hank that the police were going to mobilize and that "They're talking thousands!"

Now Hank Rieger realized the potential for bad publicity and immediately passed this information on to his superiors. Program Vice President Jerry Stanley and Hank Rieger were chosen to be the ones to meet with the students. The meeting between the two was not as confrontational as the police department and NBC had feared. What the students did not know was that those at NBC Burbank were quite in agreement with them and had urged those at the NBC headquarters at Rockefeller Square in New York to renew the show for the third season.

The police officers were very courteous and stopped traffic at intersections to let the students cross the street. They were very complimentary of the student behavior and later Gene Roddenberry later wrote a note to the department thanking them for their help.

After the march, Gene more or less admitted prior knowledge of the march in a letter to his friend Isaac Asimov. He described how he actually driven into Burbank on his motorcycle, clad in a leather jacket so he would not call attention to himself. Actually, he had been observing the whole thing from behind some bushes across the street and only emerged to join the protestors later.

The Caltech protest itself was again covered by several local newspapers. Los Angeles Times staff reporter Jerry Ruhlow's article was run on page 3, a fairly important location considering the size of the paper. Even after the show was renewed for the third season, the paper ran two more articles in July and August. The first one was a full page article with two large photos - probably the third photo by Harry Chase and one of the later ones - along with a story that remarked not only on the effect of the Caltech protest but also on the other protests at scientifically oriented colleges such as MIT. The last one was an interview with Gene Roddenberry himself who gave his own impression of the Star Trek fan phenomenon and how it had helped save the show.

Gene never did admit his involvement in either the protests or the letter writing campaign. But many at Desilu knew just how deep his involvement was. Notice the “Mr. Spock for President” stickers in the background of several photos? Oddly enough, in March 1968, Gene Roddenberry sent Paramount a reimbursement request using Desilu stationery that included:

1) 5,000 “Mr. Spock for President” bumper stickers - expense incurred in January 1968 (hmmm...)

2) Round trip airfare tickets for a Miss Wanda Kendall to fly from LA to NY to LA, including expense money.

Who was Wanda Kendall? She was a Pasadena City College student who had been recruited by Gene to sneak into the NBC studios in New York and plaster “I GROK SPOCK” and “Mr. Spock for President” bumper stickers everywhere she could, including on the back of NBC executive limousines. Even though NBC never discovered the expense account memo, they were becoming increasingly more suspicious of Roddenberry’s involvement in the Save Star Trek movement.

Indeed, Herb Solow considered the success of both the protests and the letters a double-edged sword. It did indeed play a large factor in the renewal of Star Trek for the second time. However, he believes it also was part of the reason for the miserable time slot it received which led to its demise.

And the photo above is a fitting epitaph to this article. It is held in the Caltech Archives and was part of the material donated from the Los Angeles Times coverage of the protests. Supposedly it was never used because at that time it was considered a bit too threatening. But it’s not hard to imagine this is exactly how some felt about NBC’s treatment of their favorite show.

39 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Listen/purchase: Lust Witch by Tony Galento

Tony Galento New Track!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Chuck Wepner fought a bear...

When Chuck Wepner fought a bear…

Yes, a bear. Steve Bunce on Chuck Wepner and other animals

TONY GALENTO had an advantage over the giant octopus he fought one afternoon in Atlantic City – the octopus was dead before Tony jumped in the giant fish tank. A few years later, Chuck Wepner had no advantages when he was matched with Victor, the unbeaten and untouchable bear. They met in a non-title fight in New Jersey. It was a cash…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

When Chuck Wepner fought a bear...

When Chuck Wepner fought a bear…

Yes, a bear. Steve Bunce on Chuck Wepner and other animals

TONY GALENTO had an advantage over the giant octopus he fought one afternoon in Atlantic City – the octopus was dead before Tony jumped in the giant fish tank. A few years later, Chuck Wepner had no advantages when he was matched with Victor, the unbeaten and untouchable bear. They met in a non-title fight in New Jersey. It was a cash…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

When Chuck Wepner fought a bear...

When Chuck Wepner fought a bear…

Yes, a bear. Steve Bunce on Chuck Wepner and other animals

TONY GALENTO had an advantage over the giant octopus he fought one afternoon in Atlantic City – the octopus was dead before Tony jumped in the giant fish tank. A few years later, Chuck Wepner had no advantages when he was matched with Victor, the unbeaten and untouchable bear. They met in a non-title fight in New Jersey. It was a cash…

View On WordPress

#boxing#boxing bag#boxing berlin#boxing day#boxing day 2021#boxing gloves#boxing gym near me#boxing news#boxing results#boxing tonight#boxing weight classes

0 notes

Video

youtube

Joe Louis vs Tony Galento - 06/28/1939

Because of that football game the other day, I had a convo with a couple friends about the greatest winners in sports history. They’re both team sports guys and by the fact that I run an entire blog dedicated almost exclusively to non-team sports, you can tell where I stand on the matter and was lobbying for the solo athletes.

I brought up Joe Louis just to be coy but that made me remember this fight with Tony Galento, reminding my what boxing (and most sports) looked like before sport science was a real thing.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paramount News: College Football & Pro Wrestling

Paramount News: College Football & Pro Wrestling

The wind-up of the 1946 college football season, featuring games Ohio St. v.s Northwestern and the great Charlie Trippi of Georgia runs roughshod over Alabama. Also featured: Primo Carnera in his US pro wrestling debut. Guest referee is Two-Ton Tony Galento.

source

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Why chiseled boxers lose, and flabby boxers win

Getty Images

Why chiseled boxers lose, and flabby boxers win.

It was a meeting of two diametric body types: the impeccably chiseled vs. the swollen flab of the aesthetically aloof. An experiment to determine what a real fighter should look like.

There was James Toney, the short guy who’d eaten his way out of the 160-pound division up to a rotund 217 pounds. Once referred to by HBO broadcaster Jim Lampley as a “fat tub of goo,” Toney’s body was soft, with a paunch that peeked over his trunks, and a waistline that threatened to jailbreak his butt crack from his ever-lowering shorts. By conventional standards, he didn’t look like much of a fighter.

And there was Evander Holyfield, the heavyweight division’s elder statesman who, at 41, was still a physical marvel. As he grew older and bigger, his neck got shorter and thicker, slowly consumed by sloping trapezius muscles. His shoulders became cannonballs and his weightlifter chest deepened and expanded like armour. He resembled the marble statues of ancient Greece, or perhaps more notably, the copiously oiled bodybuilder bulk of Rocky Balboa.

Holyfield had also begun his career as a much smaller man. Unlike Toney, he worked up to the heavyweight ranks seeking greater glory and fortune. To help, Holyfield’s manager, Lou Duva, sought out Tim Hallmark, a fitness guru who would forge Holyfield’s body into what some purists considered a gaudy display of the human form.

Hallmark was first hired to help Holyfield prepare for cruiserweight champ Dwight Muhammed Qawi. After Holyfield won, Hallmark was asked to make the 190-pound fighter a heavyweight.

“I said ‘yeah, but what do you mean by heavyweight?’” Hallmark said.

“We want him big,” was the answer.

“They called it the Omega Project,” Hallmark recalled. “And they wanted him to get up to like 220.”

Hallmark cautioned them: any unneeded muscle would sap much-needed energy. As the boxing truism goes, punchers are born, not made. Extra weight only offers a marginal increase in power, if any.

Holyfield packed on 12 pounds in 1988, and continued to grow until he had heaped more than 25 onto his lean frame. When he met Toney in 2003, he weighed 219 pounds. Rumors swirled that Holyfield used steroids to help him gain weight. Those suspicions reignited when Holyfield’s name surfaced during two steroid investigations of pharmacies in 2007. Holyfield denied the allegations.

His conspicuous physique fascinated commentators, including Lampley, whose stentorian proclamations would bolster the legend of Holyfield’s fitness.

“Conventional wisdom is that Evander Holyfield is the best trained, best conditioned heavyweight in the sport and maybe in the history of the sport,” he exclaimed during Holyfield’s bout with Bert Cooper.

Holyfield acquired praise through years of grueling fights, including the 15-round battle of attrition with Qawi. But some ring observers saw a man who was naturally 190 pounds being weighed down by muscle, killing his stamina. Holyfield won fights with intellect and mental toughness more than lung capacity. He’d collected an array of barfighter techniques, hitting opponents below the belt or raking their noses and cheeks with his elbow. And he regularly employed the clinch, leading with his head as he went to hug his opponent.

Holyfield had effectively learned to stall, frustrate and catch breathers for himself. After eating too many of Holyfield’s headbutts in their first fight, Mike Tyson infamously bit a chunk out of Holyfield’s ear.

Toney was different. At 5’9, he was almost five inches shorter than Holyfield, his muscles lost islands in a rising sea. His bulky shimmer evoked none of the menace of pop-culture badasses. Even his nickname, “Lights Out,” might be mistaken for the final line of a children’s story.

When the pair met in Las Vegas, boxing’s glittering capital, Toney had just survived a punishing fight with Vassily Jirov, taking nearly 250 punches on his way to narrow victory. Jirov, known for fighting German shepherds in a closed hallway during his amateur days, was famously dedicated to his training. Toney outlasted him, knocking “The Tiger” down late in a split-decision win.

Both Holyfield and Toney were considered outstanding fighters, but Holyfield had the better earnings and reputation after knocking out the palpably violent Tyson and nearly beating champion Lennox Lewis. Holyfield would bring his own brand of relentlessness, fans thought, along with what some called world-class conditioning. Toney, conversely, was known as a hard partier who loved cheeseburgers and preferred sparring over other kinds of training.

Perhaps more than their resumes, the fighters were compared by their waistlines.

“The bottom line is, what kind of shape is James Toney in?” Showtime commentator Steve Albert observed. “We’ll soon find out.”

WireImage

Little time elapsed in the fight before the outcome was certain. Toney’s waist didn’t matter. His boxing was economy of movement, his torso swiveling to offer him vast counterpunching options. His defense followed the shoulder roll tradition of the old days. Whenever Holyfield tried to punch Toney, the slickster used a suite of defensive maneuvers to create odd angles.

Nine rounds later, Holyfield’s corner threw in the towel.

Both men carried substantial extra weight into the ring, but it was the fat man who breathed easy. And yet, the fight did little to deter a movement across boxing towards bigger, more sculpted fighters. Big men with big muscles, like Michael Grant, had already been established as standards in the prize ring. Tyson came out of prison and quickly acquired a six-pack, and Lewis’ chest and arms grew throughout his career.

Holyfield, after all, was old for a prizefighter, and had suffered from high-profile health problems for years. And Toney had already distinguished himself as one of the finest technical boxers of his day. The outcome was unexpected by the sports books, but understandable.

While old-school trainers felt they had established their version of a good fighter’s body, Hallmark and celebrity trainers like Mackie Shilstone successfully led an insurgent school of thought among the sport’s age-old ideas. More conditioning coaches would follow, like Alex Ariza in the camp of Filipino superstar Manny Pacquiao.

Though the fight’s outcome was conclusive, fans still debate what an ideal fighter’s body should look like, to the chagrin of the sport’s oldest experts.

Boxing’s roots reach all the way back to 1800s England, with influences from the ancient Greek martial art of pankration. The toughest fighters were immortalized in statues or mosaics, often with idealized musculature: big arms, huge chest and sprawling veins.

But weightlifting in boxing was far from becoming as rigorous as it is today. Bob Fitzimmons, one of the sport’s biggest stars until he retired in 1914, was renowned for his strength and power and won a heavyweight championship at only 167 pounds. He advocated running for seven or eight miles every day. And while he believed in training with dumbbells and a weighted bat, he never grew bulky.

Running has been a cornerstone of boxing training since then, along with jumping rope. Generally speaking, heavyweights of yesteryear had shredded, fit physiques, but lacked the same raw size as the Holyfield era.

Primo Carnera was the first blockbuster attraction to awe audiences with sheer mass. He was a circus strongman appropriately called the “Ambling Alp,” often weighing in at 275 pounds at a time when many heavyweights didn’t even crack 200. He collected a string of knockouts in the 1930s, with headlines to match. When Earnie Schaaf died shortly after losing to Carnera, the big Italian earned a dangerous reputation. But many thought that Schaaf’s earlier beating from Max Baer’s historically dangerous right hand was the real culprit.

Boxing lore alleges most of Carnera’s fights were fixed in his favor, and by the time Carnera challenged Baer, he was no longer considered invincible. In that fight, Carnera absorbed frightening punishment from Baer and was knocked down at least half a dozen times, showing little more than oafish technique and incredible heart.

Fat boxers could also grab headlines, but with skill. Even those men, like the infamous Tony Galento, were still partly viewed as sideshows.

Galento, a beer-guzzling New Jersey heavyweight who once fought an octopus, had skill and a left hook to be feared. He stood 5’8, and was 230 pounds of pasta and meatballs. Once, Galento was anointed “the bum of the month” and offered a chance to fight Joe Lewis. He was ultimately knocked out in four rounds, but not before he dropped Lewis with that sneaky left hook, proving that corpulence doesn’t negate good technique.

But the best fighters had both fitness and skill. During boxing’s golden age, championship fighters typically eschewed weightlifting. Jack Dempsey, for example, was known for speed and devastating power, and stayed in shape by jumping rope, chopping wood and swinging a sledgehammer.

Boxers also fought more often. The all-time great “Sugar” Ray Robinson went 11-0 when he first won the middleweight title in 1951, and sometimes fought more than 20 times in a year. The extra activity forced fighters to stay close to their fighting weight between bouts, the matches themselves giving them exercise that could never be properly replicated in training. Conversely, champions today usually fight two or three times a year at most. Floyd Mayweather was famously inactive while earning some of the highest paydays in the history of the sport.

Conditioning is to be able to do in the 12th and 11th what you did in the first with the same kind of snap and energy. You can go 12 rounds and loaf the last four.” - Trainer Abel Sanchez

Trainers agree that weightlifting surfaced within boxing in the 80s and 90s, partly as a way for fighters to move up to higher divisions where they might earn more lucrative fights.

Long-time trainer Abel Sanchez, most noted for his successful stewardship of Gennadiy Golovkin, has long maintained training methods consistent with the old ways. His stable is limited to eight or nine fighters at any time, and he doesn’t consult with strength and conditioning coaches or sports psychologists. His operation is just him, making his fighters do distance runs twice a week, and sprints three times a week.

“Weights have always been something that most fighters didn’t want to mess with because they thought it tightened them up,” he said.

Golovkin, a knockout artist known for his ability to surge late in fights, was long counted among the world’s best fighters.

“To me conditioning is not the ability to go 12 rounds,” Sanchez said. “Anybody can go 12 rounds. Conditioning is to be able to do in the 12th and 11th what you did in the first with the same kind of snap and energy. You can go 12 rounds and loaf the last four.”

Trainer Jeff Fenech became another old-guard boxing trainer after a fighting career distinguished by his conditioning and toughness. He fought at a blistering pace, regularly breaking his hands. Now, he preaches short, intense workouts. In his day, he ran three miles daily at a 15-minute pace, rested, then trained just an hour in the afternoon.

Good trainers tailor their methods for the fighter. Noted stamina freak Johnny Tapia, for example, didn’t believe in running, and instead jumped rope at least an hour a day, sometimes two. But all trainers and conditioning coaches agree that too much muscle is never good, and that no strength training can substantially increase punching power. Artificially going up in weight can lead to disaster.

“It’s a matter of physical structure. Ken Norton was really muscular but he had the build for it, he had long muscle instead of short, thick muscles,” Hall of Fame trainer Jesse Reid said.

“I think it’s a mistake when they start fooling around with steroids or they get these strength and conditioning coaches that think bodybuilding is going to work.”

Reid, and others see bulky chest and leg muscles as more cosmetic than functional. With no weight limit, heavyweights are free to indulge in culinary temptations in ways smaller fighters cannot. Fighters controlled by weight classes have to closely manage their bodies before every fight. Heavyweights can pack on all the size they like, sometimes against the better judgment of their handlers.

“A guy like George Foreman did a lot of natural training,” Reid said. “He got more relaxed with his body and he started pulling cars and lifting tires and built a lot of natural strength that way. He relaxed more with his body instead of being so tight and so muscular. When he was young he was a massive muscle man.”

Late in his career, Foreman built a persona around his added fat in his late career for marketing purposes. He’d jog while eating donuts in TV commercials, and once taunted trainer Teddy Atlas to “get me a sandwich.”

Foreman, known for devastating power and composure, was good at pacing himself, even as he fattened up. He went 31-3 in his second boxing stint after a 10-year hiatus. And while many of those early opponents were soft-touches to re-establish a famous name, Foreman’s ability to remain calm and manage his work rate carried him even against top young fighters. His mobility declined, but he compensated with a high ring IQ that grew with age. Most importantly, he maintained his one-shot knockout power, which gave him a chance to win fights even if he got behind. In 1994, Foreman reclaimed a version of the heavyweight title against the young, much more svelte Michael Moorer.

“On the club level I’ve seen many sloppy bodies beat up on body beautiful over the years,” PBC matchmaker Whit Haydon said. “I’ve seen many guys who looked like they just got out of a mariachi band beat up on a guy who looks like he just got out of Gold’s Gym. Especially heavyweights.”

Too often, heavyweights ruin what had been fine-tuned machines in pursuit of a bigger purse.

“They might have had whippy power when they first turned pro and then it looks like they’re pushing out their punches and a little bit more robotic,” Haydon said. “They lose that loose flow they had when they were younger.”

Getty Images

In the days since Holyfield became a jacked Adonis, fighters have only continued to get bigger. On June 1, 2019, boxing got another high-profile bout of fat man vs. brawn, a modern-day pugilistic Aesop’s fable.

Heavyweight king Anthony Joshua had ruled the heavyweight division, beating quality competition in almost every championship defense. The undefeated fighter was even more muscular than Holyfield had ever been, somehow stacking bulk on an already huge 6’6 frame.

He’d planned to fight Jarrell “Big Baby” Miller in 2019, a 315-pound unproven boxer not known for his punching power. After Miller tested positive for illicit performance-enhancing drugs three times, he was bounced from the fight. After several emergency inquiries, promoters found a replacement fighter of almost equal girth: 268-pound Andy Ruiz. He wasn’t the typical soft-touch replacement. Ruiz had developed a reputation as a smart, tough fighter whose quaking midsection belied his blurring hand speed.

While both men were natural heavyweights, unlike Holyfield and Toney, both carried extra pounds into their fight at Madison Square Garden. Fans foresaw a bloodbath that favored the British star. Experts, however, knew Ruiz would be a handful.

Joshua came out with relentless aggression. He knocked down Ruiz in the third round and, sensing an early victory, pressed the action. But Ruiz’s hand speed advantage came into play. He exploited Joshua’s recklessness and returned the knockdown with a devastating punch, catching Joshua behind the ear and wreaking havoc on his equilibrium. Ruiz scored another knockdown that same round before finishing the fight in the seventh.

Fans marveled at the surprise victory. How could a fat guy known for eating a Snickers bar before each fight beat a man with muscles out of a Marvel comic?

“When you have more muscle, you better believe you have to condition that muscle,” said Larry Wade, the conditioning coach for top fighters like Badou Jack. “Then a guy like Andy Ruiz is so big, why didn’t he get tired? He’s fat, but you don’t have a bunch of muscle to pump oxygen to.”

Commentators and pundits echoed Wade’s diagnosis. Joshua responded by changing his training. In the rematch six months later, Joshua weighed in 10 pounds lighter at 237 pounds, his waist noticeably less musclebound. Ruiz, on the other hand, told the media that Joshua “was made for me,” and shot up to 283.

Caution and lateral movement were Joshua’s keys to victory; his lighter weight allowing him to attack, in and out, numerous times without getting tired. The bout was yet another reminder that there’s a wrong kind of muscle.

Ruiz was derided for the loss. Many critics loudly wondered if the extra weight prevented him from cutting off the ring. But Ruiz hadn’t gassed out, in spite of his size.

Commentary before and after both bouts was driven more by the fighters’ body shapes than their fighting form. Joshua drew fans awed by his impressive size. Ruiz did the same, while others found solidarity in his everyman diet. But the fights offered no conclusive evidence of what a real fighter should look like. They only showcased the importance of good mobility and conditioning.

Like the statues of antiquity, fighters will forever be judged by their musculature. But though society may favor a chiseled specimen, history has shown there will always be a place for a fat man, waiting to creep up on the unsuspecting, deriding public and become the new heavyweight king.

0 notes

Text

I Never Ast No Favors

C. M. Kornbluth

I Never Ast No Favors

Dear Mr. Marino:

I hesitate to take pen in hand and write you because I guess you do not remember me except maybe as a punk kid you did a good turn, and I know you must be a busy man running your undertaking parlor as well as the Third Ward and your barber shop. I never ast no favors of nobody but this is a special case which I hope you will agree when I explain.

To refresh your memory as the mouthpiece says in court, my name is Anthony Cornaro only maybe you remember me better as Tough Tony, which is what they call me back home in the Ward. I am not the Tough Tony from Water Street who is about 55 and doing a sixer up the river, I am the Tough Tony who is going on seventeen from Brecker Street and who you got probation for last week after I slash that nosy cop that comes flatfooting into the grocery store where some friends and I are just looking around not knowing it is after hours and that the groceryman has went home. That is the Tough Tony that I am. I guess you remember me now so I can go ahead.

With the probation, not that I am complaining, the trouble starts. The mouthpiece says he has known this lad for years and he comes from a very fine churchgoing family and he has been led astray by bad companions. So all

right, the judge says three years' probation, but he goes on to say if. If this, if that, environment, bad influences, congested city streets, our vital dairy industry denuded —such a word from a judge!—of labor . . .

Before I know what has happened, I am signing a paper, my Mama is putting her mark on it and I am on my way toChiungaCountyto milk cows.

I figure the judge does not know I am a personal friend of yours and I do not want to embarrass you by mentioning your name in open court, I figure I will get a chance later to straighten things out. Also, to tell you the truth, I am too struck with horror to talk.

Oq the ride upstate I am handcuffed to the juvenile court officer so I cannot make a break for it, but at last I get time to think and I realise that it is not as bad as it looks. I am supposed to work for a dame named Mrs. Parry and get chow, clothes and Prevailering Wages. I figure it takes maybe a month for her to break me in on the cow racket or even longer if I play dumb. During the month I get a few bucks, a set of threads and take it easy and by then I figure you will have everything straightened out and I can get back to my regular occupation, only more careful this time. Experience is the best teacher, Mr. Marino, as I am sure you know.

Well, we arrive at this town Chiunga Forks and I swear to God I never saw such a creepy place. You wouldn't believe it. The main drag is all of four blocks long and the stores and houses are from wood. I expect to see Gary Cooper stalking down the street with a scowl on his puss and his hands on his guns looking for the bad guys. Four hours from the Third Ward in a beat-up '48 police department Buick—you wouldn't believe it.

We park in front of a hash house, characters in rubber boots gawk at us, the court officer takes off the cuffs and gabs with the driver but does not lose sight of me. While we are waiting for this Mrs. Parry to keep the date I study the bank building across the street and develop some ideas which will interest you, Mr. Marino, but which I will not go into right now.

All of a sudden there is a hassle on the sidewalk.

A big woman with grey hair and a built like Tony Galento is kicking a little guy who looks like T.B. Louis the Book, who I guess you know, but not so muscular and wearing overalls. She is kicking him right in the keister, five-six times. Each time I shudder, and so maybe does the bank building across the street.

"Shoot my, dawg, will you!" she yells at the character. "I said I'd kick your butt from here toScranton when I caught up with you, Dud Wingle!"

"Leave me be!" he squawks, trying to pry her hands off his shoulders. "He was chasin' deer! He was chasin' deer!"

Thud—thud—thud. "I don't keer if he was chasin' deer, panthers or butterflies." Thud. "He was my dawg and you shot him!" Thud. She was drawing quite a crowd. The characters in rubber boots are forgetting all about us to stare at her and him.

Up comes a flatfoot who I later learn is the entire manpower of Chiunga Forks' lousiest; he says to the big woman: "Now, Ella" a few times, and she finally stops booting the little character and lets him go. "What do you want, Henry?" she growls at the flatfoot and he asks weakly: "Silver Bell dropped her calf yet?"

The little character is limping away rubbing himself. The big broad watches him regretfully and says to the flatfoot: "Yesterday, Henry. Now if you'll excuse me I have to look for my new hired boy from the city. I guess that's him over there."

She strolls over to us and yanks open the Buick's door, almost taking it off the hinges. "I'm Mrs. Ella Parry," she says to me, sticking out her hand. "You must be the Cornaro boy the Probation Association

people wired me about."

I shake hands and say, "Yes, ma'am."

The officer turns me over grinning like a skunk eating beans.

I figure Mrs. Parry lives in one of the wood houses in

Chiunga Forks, but no. We climb into a this-year Willys truck and take off for the hills. I do not have much to say to this lady wrestler but wish I had somebody smuggle me a rod to kind of even things a little between her and me. With that built she could break me in half by accident. I try to get in good with her by offering to customize her truck. "I could strip off the bumpers and put on a couple of foglights, maybe new fenders with a little trim to them," I say, "and it wouldn't cost you a dime. Even out here there has got to be some parts place where a person can heist what he needs."

"Quiet, Bub," she says all of a sudden, and shields her eyes peering down a side road where a car is standing in front of a shack. "I swear," she says, "that looks like Dud Wingle's Ford in front of Mi/' Sigafoos' place." She keeps her neck twisting around to study it until it is out of sight. And she looks worried.

I figure it is not a good time to talk and anyway maybe she has notions about customizing and does not approve of it.

"What," she says, "would Dud Wingle want with Miz' Sigafoos?"

"I don't know, ma'am," I say. "Wasn't he the gentleman you was kicking from here toScranton?"

"Shucks, Bub, that was just a figger of speech. If I'd of wanted to kick him from here toScrantonI'd of done it. Dud and Jim and Ab and Sime think they got a right to shoot your dog if he chases the deer. I'm a peaceable woman or I'd have the law on them for shootin' Grip. But maybe I did kind of lose my temper." She looked worrieder yet.

"Is something wrong, ma'am?" I ask. You never can tell, but a lot of old dames talk to me like I was their uncle; to tell you the truth this is my biggest problem in a cathouse. It must be because I am a kind of thoughtful guy and it shows.

Mrs. Parry is no exception. She says to me: "You don't know the folks up here yet, Bub, so you don't know about Miz' Sigafoos. I'm old English stock so I don't

hold with their foolishness, but——" And here she looked real worried. "Miz' Sigafoos is what they call a hex doctor."

"What's that, ma'am?"

"Just a lot of foolishness. Don't you pay any attention," she says, and then she has to concentrate on the driving. We are turning off the two-lane state highway and going up, up, up into the hills, off a blacktop road, off a gravel road, off a dirt road. No people. No houses. Fences and cows or maybe horses, I can't tell for sure. Finally we are at her place, which is from wood and in two buildings. I start automatically for the building that is clean, new-painted, big and expensive.

"Hold on, Bub," she says. "No need to head for the barn first thing. Let's get you settled in the house first and then there'll be a plenty of work for you."

I do a double take and see that the big, clean, expensive building is the barn. The little, cheap, rundown place is the house. I say to myself: "Tough Tony, you're gonna pray tonight that Mr. Marino don't forget to tell the judge you're a personal friend of his and get you out of this,"

But that night I do not pray. I am too tired. After throwing sacks of scratch feed and laying mash around, I run the baling machine and I turn the oats in the loft and I pump water until my back is aching jello and then I go hiking out to the woodlot and chop down trees and cut them up with a chain saw. It is surprising how fast I learn and how willing I am when I remember what Mrs. Parry did to Dud Wingle.

I barely get to sleep it seems like when Mrs. Parry is yanking the covers off me laughing and I see through the window that the sky is getting a little light. "Time to rise, Bub," she bawls. "Breakfast on the table." She strides to the window and flexes her muscles, breathing deep. "It's going to be a fine day. I can tell when an animal's sick to death, and I can tell when it's going to be fine all day. Rise and shine,

Bub. We have a lot of work ahead. I was

kind of easy on you yesterday seeing you was new here, so we got a bit behindhand."

I eye the bulging muscles and say "Yes, ma'am."

She serves a good breakfast, I have to admit. Usually I just have some coffee around eleven when I wake up and maybe a meatball sandwich around four, but the country air gives you an appetite like I always heard. Maybe I didn't tell you there was just the two of us. Her husband kicked off a couple years ago. She gave one of her boys half the farm because she says she don't believe in letting them hang around without a chance to make some money and get married until you die. The other boy, nineteen, got drafted two months ago and since then she is running the place on her own hook because for some reason or other it is hard to get people to work on a farm. She says she does not understand this and I do not enlighten her.

First thing after breakfast she tells me to make four crates from lumber in the toolshed, go to the duckpond and put the fourMuscovyducks in the crates so she can take them to town and sell them. She has been meaning to sell theMuscovyducks for some time since the word has been getting around that she was pro-communist for having such a breed of ducks when there were plenty of good American ducks she could of raised. "Though," she says, "in my opinion the Walterses ought to sell off theirPeking ducks too because the Chinese are just as bad as the Roossians."

I make the crates which is easy and I go to the duck-pool. There are four ducks there but they are not swimming; they have sunk. I go and tell Mrs. Parry and she looks at me like I was crazy.

"Yeah," I tell her. "Sunk. Down at the bottom of the pond, drownded. I guess maybe during the night they forgot to keep treading water or something."

She didn't say a word. She just strides down the path to the duckpond and looks into it and sees the four ducks. They are big, horrible things with kind of red Jimmy Valentine masks over their eyes, and they are lying at the bottom of the pond. She wades in, still without a word,

I

and fishes them out. She gets a big shiv out of her apron pocket, slits the ducks open, yanks out their lungs and slits them open. Water dribbles out.

"Drownded," she mutters. "If there was snapping turtles to drag them under . . . but there ain't."

I do not understand what the fuss is about and ast her if she can't sell them anyway. She says no, it wouldn't be honest, and I should get a shovel and bury them. Then there is an awful bellering from the cowbarn. "Agnes of Lincolnshire!" Mrs. Parry squawks and dashes for the barn. "She's dropping her calf ahead of time!"

I run along beside her. "Should I call the cops?" I pant. "They always get to the place before the ambulance and you don't have to pay them nothing. My married sister had three kids delivered by the cops—"

But it seems it's different with cows and anyway they have a different kind of flatfoot out here that didn't go to Police Academy. Mrs. Parry finally looks up from the calf and says "I think I saved it. I know I saved it. I can tell when an animal's dying. Bub, go to the phone and call Miz' Croley and ask her if she can possibly spare Brenda to come over and do the milkin' tonight and tomorrow morning. I dassn't leave Agnes and the calf; they need nursing."

I stagger out of the cowbarn, throw up two-three times and go to the phone in the house. I seen them phones with flywheels in the movies so I know how to work it. Mrs. Croley cusses and moans and then says all right she'll send Brenda over in the Ford and please to tell Mrs. Parry not to keep her no longer than she has to because she has a herd of her own that needs milking.

I tell Mrs. Parry in the barn and Mrs. Parry snaps that Mrs. Croley has a living husband and a draft-proof farmhand and she swore she didn't know what things were coming to when a neighbor wouldn't help another neighbor out.

I ast casually: "Who is this Brenda, ma'am?"

"Miz' Croley's daughter. Good for nothing."

I don't ast no more questions but I sure begin to wait

with interest for a Ford to round the bend of the road.

It does while I am bucking up logs with the chainsaw. Brenda is a blondie about my age, a little too big for her dress—an effect which I always go for, whether in the Third Ward or Chiunga County. I don't have a chance to talk to her until lunch, and then all she does is giggle. But who wants conversation? Then a truck comes snorting up the driveway. Something inside the truck is snorting louder than the truck.

Mrs. Parry throws up her hands. "Land, I forgot! Belshazzar the Magnificent for Princess Leilani!" She gulps coffee and dashes out.

"Brenda," I said, "what was that all about?"

She giggles and this time blushes. I throw down my napkin and go to the window. The truck is being backed to a field with a big board fence around it. Mrs. Parry is going into the barn and is leading a cow into the field. The cow is mighty nervous and I begin to understand why. The truckdriver opens the tailgate and out comes a snorting bull.

I think: well, I been to a few stag shows but this I never seen before. Maybe a person can learn something in the country after all.

Belshazzar the Magnificent sees Princess Leilani. He snorts like Charles Boyer. Princess Leilani cowers away from him like Bette Davis. Belshazzar the Magnificent paws the ground. Princess Leilani trembles. And then Belshazzar the Magnificent yawns and starts eating grass.

Princess Leilani looks up, startled and says: "Huh?" No, on second thought it is not Princess Leilani who says "Huh?" It is Brenda, at the other kitchen window. She sees me watching her, giggles, blushes and goes to the shik and starts doing dishes.

I guess this is a good sign, but I don't press my luck. I go outside, where Mrs. Parry is cussing out the

truck-driver. "Some bull!" she yells at him. "What am I supposed to do now? How long is Leilani going to stay in season? What if I can't line up another stud for her? Do you realise what it's going to cost me in veal and milk

checks—" Yatata, yatata, yatata, while the truckdriver keeps trying to butt hi with excuses and Belshazzar the Magnificent eats grass and sometimes gives Princess Lei-lani a brotherly lick on the nose, for by that time Princess Leilani has dropped the nervous act and edged over mooing plaintively.

Mrs. Parry yells: "See that? I don't hold with artificial insemination but you dang stockbreeders are driving us dairy farmers to it! Get your—your steer off my property before I throw him off! I got work to do even if he hasn't! Belshazzar the Magnificent—hah\"

She turns on me. "Don't just stand around gawking, Bub. When you get the stovewood split you can stack it in the woodshed." I scurry off and resume Operation Woodlot, but I take it a little easy which I can do because Mrs. Parry is in the cowbarn nursing Agnes of Lincolnshire and the preemie calf.

The next morning at breakfast I am in a bad temper, Brenda has got the giggles and Mrs. Parry is stiff and tired from sleeping hi the barn. We are a gruesome threesome, and then a car drives up and a kid of maybe thirty comes bursting into the kitchen. He has been crying. His eyes are red and there are clean places on his face where the tears ran down. "Ma!" he whimpers at Mrs. Parry. "I got to talk to you! You got to talk to Bonita, she says I don't love her no more and she's going to leave me!"

"Hush up^ George," she snaps at him. "Come into the parlor." They go into the parlor and Brenda whistles: "Whoo-ee! Wait'111 tell Maw about this!"

"Who is he?"

"Miz' Parry's boy George. She gave him the south half of the farm and built him a house on it. Bonita's his wife. She's a stuck-up girl from Ware County and she wears falsies and dyes her hair and—" Brenda looks around, lowers her voice and whispers "—and she sends her worshing to the laundry in town."

"God in Heaven," I say. "Have the cops heard about this?"

"Oh, it's legal, but you just shouldn't do it."

"I see. I misunderstood, I guess. Back in the Third Ward it's a worse rap than mopery with intent to gawk. The judges are ruthless with it."

Her eyes go round. "Is that a fact?"

"Sure. Tell your mother about it."

Mrs. Parry came back hi with her son and said to us: "Clear out, you kids. I want to make a phone call."

"I'll start the milkin'," Brenda said.

"And I'll framble the portistan while it's still cool and barkney," I say.

"Sure," Mrs. Parry says, cranking the phone. "Go and do that, Bub." She is preoccupied.

I go through the kitchen door, take one sidestep, flatten against the house and listen. Reception is pretty good.

"Bonita?" Mrs. Parry says into the phone. "Is that you, Bonita? Listen, Bonita, George is here and he asked me to call you and tell you he's sorry. I ain't exactly going to say that. I'm going to say that you're acting like a blame fool . . ." She chuckles away from the phone and says: "She wants to talk to you, George/Don't be too eager, boy."

I slink away from the kitchen door, thinking: "Ah-hah!" I am thinking so hard that Mrs. Parry bungles into me when she walks out of the kitchen sooner than I expect.

She grabs me with one of those pipe-vise hands and snaps: "You young devil, were you listening to me

on the phone?"

Usually, it is the smart thing to deny everything and ast for your mouthpiece, but up here they got no mouthpieces. For once I tell the truth and cop a plea. "Yes, Mrs. Parry. I'm so ashamed of myself you can't imagine. I always been like that. It's a psy-cho-logical twist I got for listening. I can't seem to control it. Maybe I read too many bad comic books. But honest, I won't breathe a word." Here I have the sense to shut up.

She shakes her head. "What about the ducks that sank and Agnes dropping her calf before her time? What about

Belshazzar?" She begins to breathe through her nostrils. "It's hexin', that's what it is!"

"What's hexin', ma'am?"

"Heathen doings by that old Miz' Sigafoos. She's been warned and warned plenty to stick to her doctoring. I hold nothing against her for curing the croup or maybe selling a young man love potion if he's goin' down to Scranton to sell his crop and play around a little. But she's not satisfied with that, I guess. Dud Wingle must of gone to her with a twenty-dollar bill to witch my farm!"

I do not know what to make of this. My mama, of course, has told me about la vecchia religione, but I never know they believe in stuff like that over here. "Can you go to the cops, ma'am?" I ast.

She snorts like Belshazzar the Magnificent. "Cops! A fat lot old Henry Bricker would know about witchin'. No, Bub, I guess I'll handle this myself. I ain't the five-times-great-granddaughter of Pru Posthlewaite for nothin'!"

"Who was Pru— what you said?"

"Hanged in Salem, Massachusettes, in 1680 for witchcraft. Her coven name was Little Gadfly, but I guess she wasn't so little. The first two ropes broke—but we got no time to stand around talkin'. I got to find my Ma's truck in the attic. You go get the black rooster from the chicken run. I wonder where there's some chalk?" And she walks off to the house, mumbling. I walk to the chicken run thinking she

has flipped.

The black rooster is a tricky character, very fast on his feet and also I am new at the chicken racket. It takes me half an hour to stalk him down, during which time incidentally the Ford leaves with Brenda in it and George drives away in his car. See you later, Brenda, I think to myself.

I go to the kitchen door with the rooster screaming in my arms and Mrs. Parry says: "Come on in with him and set him anywhere." I do, Mrs. Parry scatters some cornflakes on the floor and the rooster calms down right away and stalks around picking it up. Mrs. Parry is sweaty and

dust-covered and there are some dirty old papers rolled up on the kitchen table.

She starts fooling around on the floor with one of the papers and a hunk of carpenter's chalk, and just to be doing something I look at the rest of them. Honest to God, you never saw such lousy spelling and handwriting. Tayke the Duste off one Olde Ymmage Quhich Ye Myn-gel—like that.

I shake my head and think: it's the cow racket. No normal human being can take this life. She has flipped and I don't blame her, but it will be a horrible thing if it becomes homicidal. I look around for a poker or something and start to edge away. I am thinking of a dash from the door to the Willys and then scorching into town to come back with the men in the little white coats.

She looks up at me and says: "Don't go away, Bub. This is woman's work, but I need somebody to hold the sword and palm and you're the onliest one around." She grins. "I guess you never saw anything like this in the city, hey?"

"No, ma'am," I say, and notice that my voice is very faint.

"Well, don't let it skeer you. There's some people it'd skeer, but the Probation Association people say they call you Tough Tony, so I guess you won't take fright."

"No, ma'am."

"Now what do we do for a sword? I guess this bread knife'U—no; the ham slicer. It looks more like a sword. Hold it in your left hand and get a couple of them gilded bulrushes from the vase in the parlor. Mind you wipe your feet before you tread on the carpet! And then come back. Make it fast."

She starts to copy some stuff that looks like Yiddish writing onto the floor and I go into the parlor. I am about to tiptoe to the front door when she yells: "Bub! That you?"

Maybe I could beat her in a race for the car, maybe not. I shrug. At least I have a knife—and know how to use it. I bring her the gilded things from the vase. Ugh!

While I am out she has cut the head off the rooster and is sprinkling its blood over a big chalk star and the writing on the floor. But the knife makes me feel more confident even though I begin to worry about how it will look if I have to do anything with it. I am figuring that maybe I can hamstring her if she takes off after me, and meanwhile I should humor her because maybe she will snap out of it.

"Bub," she says, "hold the sword and palms in front of you pointing up and don't step inside the chalk lines. Now, will you promise me not to tell anybody about the words I speak? The rest of this stuff don't matter; it's down in all the books and people have their minds made up that it don't work. But about the words, do you promise?"

"Yes, ma'am. Anything you say, ma'am."

So she starts talking and the promise was not necessary because it's in some foreign language and I don't talk foreign languages except sometimes a little Italian to my mama. I am beginning to yawn when I notice that we have company.

He is eight feet tall, he is green, he has teeth like Red Riding Hood's grandma.

I dive through the window, screaming.

When Mrs. Parry comes out she finds me in a pile of broken glass, on my knees, praying. She clamps two fingers on my ear and hoists me to my feet. "Stop that praying," she says. "He's complaining about it.

Says it makes him itch. And you said you wouldn't be skeered! Now come inside where I can keep an eye on you and behave yourself. The idea! The very idea!"

To tell you the truth, I don't remember what happens after this so good. There is some talk between the green character and Mrs. Parry about her five-times-great-grandmother who, it seems, is doing nicely in a warm climate. There is an argument in which the green character gets shifty and says he doesn't know who is working for Miz' Sigafoos these days. Miz' Parry threatens to let me pray again and the green character gets sulky and says

all right he'll send for him and rassle with him but he is sure he can lick him.

The next thing I recall is a grunt-and-groan exhibition between the green character and a smaller purple character who must of arrived when I was blacked out or something. This at least I know something about because I am a television fan. It is a very slow match, because when one of the characters, for instance, bends the other character's arm it just bends and does not break. But a good big character can lick a good little character every time and finally greenface has got his opponent tied into a bow-knot.

"Be gone," Mrs. Parry says to the purple character, "and never more molest me or mine. Be gone, be gone, be gone."

He is gone, and I never do find out if he gets unknotted.

"Now fetch me Miz' Sigafoos."

Blip! An ugly little old woman is sharing the ring with the winner and new champeen. She spits at Mrs. Parry: "So you it was dot mine Teufel haff ge-schtolen!" Her English is terrible. A greenhorn.

"This ain't a social call, Miz' Sigafoos," Mrs. Parry says coldly. "I just want you to unwitch my farm and kinfolks. And if you're an honest woman you'll return his money to that sneakin', dog-murderin' shiftless squirt, Dud Wingle."

"Yah," the old woman mumbles. She reaches up and feels the biceps of the green character. "Yah, I guess maybe dot I besser do. Who der Yunger iss?" She is looking at me. "For why the teeth on his

mouth go clop-clop-clop? Und so white the face on his head iss! You besser should feed him, Ella."

"Missus Parry to you, Miz' Sigafoos, if you don't mind. Now the both of you be gone, be gone, be gone."

At last we are alone.

"Now," Mrs. Parry grunts, "maybe we can get back to farmin'. Such foolishness and me a busy woman." She looks at me closely and says: "I do believe the old fool was right. You're as white as a sheet." She feels my fore-

head. "Oh, shoot! You have a temperature. You better get to bed. If you ain't better in the morning I'll call Doc Mines."

So I am in the bedroom writing this letter, Mr. Marino, and I hope you will help me out. Like I said, I never ast no favors but this is special.

Mr. Marino, will you please go to the judge and tell him I have a change of heart and don't want no probation? Tell him I want to pay my debt to society. Tell him I want to go to jail for three years, and for them to come and get me right away. Sincerely,

ANTHONY (Tough Tony) CORNARO.

P.S.—On my way to get a stamp for this I notice that I have some grey hairs, which is very unusual for a person going on seventeen. Please tell the judge I wouldn't mind if they give me solitary confinement and that maybe it would help me pay my debt to society.

In haste, T.T.

0 notes