#treating her like garbage in life but sanctifying her in death

Text

A WOMAN WHO’S JUST IN HIS HEAD

“In death, Jane became the ultimate consort; unblemished (especially in the eyes of her capricious and tyrannical husband), ever young, and the mother of a surviving son. Instead of merely being the wife who ‘died’ and in recognition of her saint-like life — which went beyond the medieval ideal of saintly queenship — Jane should actually be remembered as the wife who was (effectively) canonised.” - Aidan Norrie

#jane seymour#Henry VIII#the Tudors#consistently throughout Jane’s ‘afterlife’ there appears this one theme#of a disparity between how she’s remembered and how she ‘actually’ was#things like historians saying she should be remembered as evil but is actually remembered as good#or that she should be remembered as shrewd but is actually remembered as simple#etc etc etc#it also appears on a more personal level in how she was treated by her male family;#such as Henry making a pilgrimage to Thomas Beckett’s shrine to celebrate her pregnancy and then letting it be destroyed#treating her like garbage in life but sanctifying her in death#& Edward overlooking her well recorded catholicism to portray her as a reformist in line with his own beliefs during his regime#which wasn’t even entirely his fault because like. what did I just say. Henry made up a new Jane after the real one died.#how was Edward supposed to have a clear image of his mother? how was anyone?#on every level there’s so much ‘what I need/want her to have been’ and so little ‘who she actually was’#it’s haunting

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

To talk about Twice and villainy is to talk about class and criminality (IV)

(Masterlist)

cw: references the dehumanization of “terrorists,” like, irl

The trash of society

“Disposability” is a framework that interrogates the way human lives are valued. Arising from observations about material disposability in the rapid industrialization of post-’45 and the increasing hold of mass-production and consumerism, “disposability” eventually expanded to an investigation of the human cost of this modern landscape. Theorists raised the question of how the disposability of human lives could be understood in tandem with the disposability of material goods, linking together issues of class, poverty, migration, imperialism, race, production, and consumerism. In essence, disposability as a framework investigates how human lives come to be rendered as disposable—and thus, like waste, byproducts of a lifestyle of endless growth.

This concern is one that receives frequent exploration in fiction that delves into the framework of humans-as-waste; for example, the sci fi dystopian short story Folding Beijing follows a waste worker in his efforts to fund the education of his adoptive daughter, who he found abandoned outside his waste-processing station. Although the conditions in BNHA aren’t nearly as grim, there are nevertheless clear connections drawn between its villainous characters and the concept of humans-as-waste, to the point where villains refer to themselves or are referred to by others as “trash.” Quirks may have effected a massive social upheaval, but that didn’t do away with, only shifted, the specifics of the idea that there are people who are deserving and people who are not, innocent people and criminals.

Throughout the series, we see characters mistreated while a society of deserving innocents looks on. There was little concern from the public when Izuku was mocked and bullied for his Quirklessness, when Rei was sold into a marriage for the benefit of a wealthy and abusive pro hero, when five-year-old Tenko wandered the streets alone, and when Jin was left to fend for himself as a teenager. Under the framework of disposability, they might as well have been rendered “waste,” as Zygmunt Bauman writes: “[t]he story we grow in and with has no interest in waste[...],” instead

“[w]e dispose of leftovers in the most radical and effective way: we make them invisible by not looking and unthinkable by not thinking. They worry us only when the routine elementary defences are broken and the precautions fail—when the comfortable, soporific insularity of our Lebenswelt which they were supposed to protect is in danger.” [source]

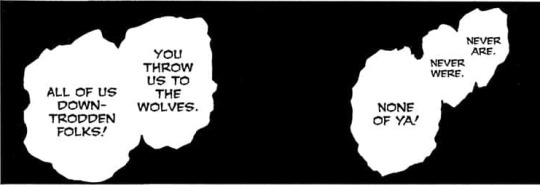

It is, interestingly, a bigger-picture version of the charges Shigaraki Tomura directs against the world of BNHA: like Bauman says, the innocent civilians are oblivious, recognizing neither the fragility of their peace nor the artificiality of it as it is maintained by heroes, unwilling to acknowledge the "leftovers”—the people who weren’t saved—until they return as villains and that very peace is threatened.

As for the leftovers themselves, they feel their alienation acutely. According to Bauman, to be “redundant” in a productivity-driven economy is to “share semantic space with ‘rejects’, wastrels’, ‘garbage’, ‘refuse’—with waste.” He outlines the conditions of redundancy thusly, describing it as a kind of “social homelessness”:

“To be redundant means[... t]he others do not need you; they can do as well, and better, without you. There is no self-evident reason for your being around and no obvious justification for your claim to the right to stay around. To be redundant means to have been disposed of because of being disposable[...]”

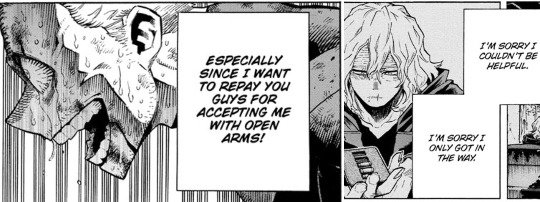

The experience of this kind of disposability is evident in BNHA, as class and exploitation seem to be highly correlated with social isolation. The members of the Shie Hassaikai were used and abandoned, and bonded strongly to one another after joining Overhaul. Jin’s experience of “social homelessness” shows him walking alone through empty city streets, before he ends up talking to his own clone below an overpass. Jin, too, finds companionship in joining a group, the League of Villains, but fears of disposability and further isolation plague his thoughts. Whether or not he genuinely believes League of Villains would abandon him, Jin feels the need to continue justifying his place among them. The societal bleeds into the personal; Jin’s disposability to society, best represented by his interactions with law enforcement and with his employer, also becomes an anxiety in his interpersonal relationships. Horikoshi’s decision to characterize Jin in such a way makes it impossible to ignore the larger issues that created him; namely, class issues that reflect real-world concerns.

As Jin sits below the overpass, talking to his clone, he asks whether he went wrong somewhere. The other Jin responds that it must have been “being born without an ounce of luck.” Bauman comments on unluckiness thusly:

“In Samuel Butler’s Erewhon it was ‘ill luck of any kind, or even ill treatment at the hands of others’ that was ‘considered an offence against society, inasmuch as it [made] people uncomfortable to hear of it.’ ‘Loss of fortune, therefore’ was ‘punished hardly less severely than physical delinquency’.” [source]

These observations are perfectly applicable to the characters we’ve met. It’s often the “unlucky” who get treated the worst: Izuku was bullied relentlessly for his “unlucky” Quirklessness, and Rei wound up trading her “unlucky” marriage for an institutionalization of ten years. Jin was fired from his job after an “unlucky” accident, fell into a life of crime, and is finally killed by the same hero who offered him a second chance. When Dabi probes Tokoyami Fumikage in an attempt to make him contend with Jin’s “ill treatment” at Hawks’ hands, Tokoyami dismisses it and justifies Jin’s execution, undoubtedly because it would be uncomfortable, possibly even world-shattering, to acknowledge Dabi’s charge. The fact that these people have been unlucky, or have even been actively mistreated or failed by others, turns the public’s gaze away in an attempt to escape the discomfort elicited by these embodiments of society’s waste. For the “redundant” to remind society of its human cost—or even to remind the non-redundant of the small gap of bad luck that separates them—they become objects of revulsion, to be forgotten or discarded as quickly as possible. Rendered “invisible” and “unthinkable” as leftovers, they become “ontologically non-existent.” [source]

Some of the anxiety towards the “redundant” is precisely because the framework of “becoming waste” is permeable. This permeability accounts for the possibility of transforming from citizen to disposable human; perhaps, then, when “all it takes is one bad day,” the line which separates citizen from villain is just as permeable. In the framework of hero society, it may be argued that villains are not simply redundant waste, but the trash whose alienation hero society relies on in a highly visible way. "The disposable, the waste as objects and humans, inhabit a place of exclusion from society which provides not only an unrecognized space of reinforcement for society itself, but also the fuel and the labor for maintaining the status quo.” [source] In BNHA’s terms, not only are villains excluded from a deserving, innocent society, they are also the fuel for maintaining it by embodying its opposite—the guilty and undeserving—their exclusion constantly reinforced through the public spectacle of their arrests and the public idolization of heroes. Villains are no longer simply inert leftovers that can be easily ignored, as Bauman described; villains have broken past hero society’s elementary defenses, and threaten the Lebenswelt of deserving innocents. While their visibility transforms villains back into an acknowledgeable existence, the very act of breaching their invisibility renders them a kind of waste that must be permanently disposed of.

A livable life?

Heroes do not kill. This is stated in 251 by the death-seeking Ending, who, despite his best efforts, is spared an unceremonious execution at the hands of a hero, who the readers know is a domestic abuser. The deathless resolution to Ending’s conflict, then, further compounds the horror of chapter 266, when Jin is eliminated with extreme prejudice by Hawks, who admires the aforementioned hero. The irony is shocking and bitter as readers witness the violation of one of heroism’s fundamental tenets, broken no less for the elimination of one of the series’ most sympathetic villains, after Hawks himself concedes that Jin is “a good person.” It may be said that heroes do not have carte blanche to kill, but neither is it an inviolable principle, and of course a no-kill mandate says nothing about the ways villains have been injured or tortured at the hands of heroes. While arguments can be made about the imminent risk of certain occasions, the issue remains that it’s often the most vulnerable people who pay the highest price for maintaining a nebulous definition of societal “safety” (a “safety” which always seemed to exclude certain people), a concept that is primarily defined by the state and the policing class. Furthermore, the willingness of a hero to kill in defense of hero society begs the question: who may be killed without consequence, and under what circumstances?

In her collection of essays addressing responses to terrorism, Precarious Life, Judith Butler writes:

“Certain lives will be highly protected, and the abrogation of their claims to sanctity will be sufficient to mobilize the forces of war. Other lives will not find such fast and furious support and will not even qualify as "grievable."”

The notion of a “safe” society hinges on the protection of those sanctified lives, at the expense of vulnerable lives deemed “disposable” through poverty, homelessness, or criminality. A threat against the deserving innocents or the murder of a hero unites every other hero and every citizen in public mourning, and then in opposition against murderous villains—there is no such mobilization for the suffering of Quirkless kids, abused women, or orphaned, destitute teenagers. The threats against their well-beings are considered part-and-parcel to their world—normal, unavoidable, and indeed not violence at all. Certainly, a murdered villain will not find such unanimous grief nor anger mobilized in the wake his death, not even directed toward changing the isolated, impoverished conditions which made villainy an appealing choice in the first place. Jin’s death is privately witnessed and privately mourned, only by those who comprised his ibasho. It’s through these uneven displays of grief that Butler questions: “what counts as a livable life and a grievable death?”

Butler argues that certain lives are removed from the bounds of “normative” humanity, and thus “grievability.” Violence against vulnerable lives is dismissed or legitimized by the state through their dehumanization: in the world of BNHA, villains are “presented [...] as so many faces of evil” and treated as mere vessels of a killing instinct.

“Are they pure killing machines? If they are pure killing machines, then they are not humans [...]. They are something less than human, and yet somehow they assume a human form. They represent, as it were, an equivocation of the human, which forms the basis for some of the skepticism about the applicability of legal entitlements and protections.”

This kind of dehumanization is, of course, explained through the claim that certain people are “dangerous,” a designation which (as Butler points out) is determined by none other than the state itself.

“A certain level of dangerousness takes a human outside the bounds of law[... T]he state posits what is dangerous, and in so positing it, establishes the conditions for its own preemption and usurpation of the law[...]”

Perhaps, then, if villains are something other-than-human, something so dedicated to violence that they can be stopped only through death, no "sanctity,” and no law, is violated if they are killed.

The ability of the state to designate certain people as “dangerous” is linked to another political strategy: defining the difference between “legitimate” and “illegitimate” violence. Butler explains:

“The use of the term, "terrorism," thus works to delegitimate certain forms of violence committed by non-state-centered political entities at the same time that it sanctions a violent response by established states. [...] In this sense, the framework for conceptualizing global violence is such that "terrorism" becomes the name to describe the violence of the illegitimate, whereas legal war becomes the prerogative of those who can assume international recognition as legitimate states.” [source]

In the world of BNHA, clearly such a discernment exists between “legitimate” and “illegitimate” violence. Although certain readers have been quick to draw the “terrorism” analogy, the series itself tends to differentiate between “legitimate” and “illegitimate” violence not through charges of terrorism, but through the designation of “hero” and “villain.” Legitimate violence is wielded by heroes in defense of the state, in defense of property, and against villains, whereas illegitimate violence is wielded by villains against the state, against property, and against heroes. This difference between “hero” and “villain” is, in actuality, insubstantial as far as the question of morality, as even labeled villains such as Gentle Criminal behave within a palatable frame of ethics, while some career heroes are just as capable as villains of taking and ruining lives; nevertheless, the state has a vested interest in strongly promoting the idea of this divide—of legitimate, heroic violence as moral, justified, and legal, and illegitimate, villainous violence as immoral, unjustified, and unlawful. In this way, the state can engage in “legal war” with very little questioning or dissent from its populace, and it further delegitimizes the violence of its opponents. The violence of heroes is justified, and therefore they have an understandable human rationale; on the contrary, the violence of villains is unjustified, it is attributed to their innate violence, which is incomprehensible and inhuman.

“The fact that these prisoners are seen as pure vessels of violence [...] suggests that they do not become violent for the same kinds of reason that other politicized beings do, that their violence is somehow constitutive, groundless, and infinite, if not innate. If this violence is terrorism rather than violence, it is conceived as an action with no political goal, or cannot be read politically. It emerges, as they say, from fanatics, extremists, who do not espouse a point of view, but rather exist outside of "reason," and do not have a part in the human community.” [source]

No one personifies this better than Tomura himself. He is named the “Symbol of Terror” by AFO, and is undoubtedly viewed as such by the heroes and civilians of BNHA. It has been repeatedly emphasized that to everyone but the League of Villains, Tomura is not so much a human as he is the embodiment of thoughtless destruction. Tomura is referred to as a monster, as someone unshackled to humanity, as an “it,” as something that cannot be reasoned with. This is an idea that Horikoshi himself seems to play into somewhat, because although Tomura voices certain critiques of the hero system, he nevertheless seems to remain rather apolitical in who or what he decides to target. It’s Jin, then, who lends a political voice to the villains by criticizing pro heroes from his very first narrated chapter, but even a clear articulation of his grievances gets him no understanding reaction from the hero in front of whom he raises these charges.

While the fictional heroes may see villains as nothing more than vessels of violence, it can be argued that Horikoshi himself went through an extensive effort to depict the rationale and humanity of the villains. As I’ve stated before, Jin is very clearly connected to the real-world struggles of certain Japanese citizens, making him real and relatable in ways other characters may not be. At the same time, the rationale and humanity that Horikoshi recognizes are things that heroes like Hawks can’t grasp: as someone who idolized a hero as a child, and who was, for better or worse, enveloped by the hero system, he does not question the legitimacy of the hero system. Hawks understands only unluckiness in Jin’s circumstances, and shows little awareness of the fact that Jin was failed by the very society Hawks defends, that his suffering was both enforced by the legal system and by his boss, and ignored by institutions supposedly designed to help. Jin, of course, is not so obtuse—he reiterates his awareness that he is one of those disposable, ungrievable lives that heroes don’t save, and he is ultimately proven right—when Hawks’ offer of rehabilitation is rejected, he instead moves to kill. Jin, and other villains, are so thoroughly dehumanized, likened to killing machines, that it doesn’t occur to any hero that they can possibly be reasoned with.

Could there have been any other conclusion? I don’t believe so—not without a significant shift in thinking from heroes. For many of the villains, there’s very little to gain from rejoining the society that they were ejected from. Bauman writes that, for “disposable” humans:

“Unwelcome, tolerated at best, cast firmly on the receiving side of socially recommended or tolerated action, treated in the best of cases as an object of benevolence, charity and pity (challenged, to rub salt into the wound, as undeserved), but not of brotherly help, charged with indolence and suspected of iniquitous intentions and criminal intentions, [they have] few reasons to treat ‘society’ as a home to which one owes loyalty and concern.”

It should come as no surprise, then, that Jin rejects Hawks’ offer of a “socially tolerated” rehabilitation into the society that both caused and ignored his suffering, which he has no reason to believe wouldn’t outcast him again for another slip-up. Of course, he instead chose the place he was understood, where his mistakes were met with patience, where he wasn’t forced to justify his presence, where his sense of belonging felt stable. The people he called his ibasho were a home, a place he was allowed an ontological existence—the very inverse of that old, disposable life.

Conclusion

Bubaigawara Jin should be read as class commentary. The various obstacles in his story are all too reflective of the systemic issues of real-world Japan, concisely highlighting the shortcomings and common abuses of the alternative care system, the justice system, and the workplace. It’s also highly likely that Horikoshi himself is aware of economic inequalities on some level, which seems to reflect in the obvious and less-obvious ways he addresses class in BNHA. I think this probable intentionality is important, as it can lend itself to our speculation on the series’ messages and themes. Importantly, if Jin’s story is a commentary about the real-world trials of economic marginalization, then surely this also applies to the way he is treated by heroes and by wider society. Beyond simple evaluations of “X did this, which forced Y to respond,” certain narrative choices may be better understood as a pattern of illustrating disposability, of the way this fictional society creates “human waste,” and to relate them to real-world patterns of which lives are considered worth saving.

I somewhat downplayed the real-world inspirations for Bauman and Butler’s texts, because I believe those are true and serious topics about capitalism and war that should be discussed on their own merits, unrelated to a fictional series; however, they also perfectly show how certain beliefs in the real world are transferrable to BNHA’s world. Because these beliefs are transferrable, readers’ reactions to certain narratives in fiction are rooted in certain truths we believe about the real world as well. For example, it would pointless to call the League of Villains “terrorists” as a condemnation, unless someone believes that the charge of “terrorism” in itself tells us anything meaningful about morality. As Butler has explained, and as real life shows (e.g. through the designation of black radical groups like the Black Panthers or antifascist groups as terrorist organizations), the term “terrorism” alone holds no inherent moral implication. Imagining that the label of “terrorist” can meaningfully convey anything about morality, and that "being a terrorist” removes a person from the boundaries of “normative humanity” (and thus due legal process in-universe, and reader sympathy out-of-universe) reflects an ignorance about certain real-world political processes.

Injustice in the world doesn’t only take the form of obvious oppression and violence; manipulation is also involved. There is a vested interest by the ruling class in guiding the ways people think and perceive reality, teaching us what we deserve and don’t deserve, what prices are acceptable and unacceptable to pay for human life. These lessons must be rejected from the outset, leaving rules and definitions open for interpretation. What qualifies as violence? Is violence more than a physical act of harm? Is it violence to isolate “unproductive” members of society? Is it violence to deny them food and shelter? Is it then violence to cage and execute them when they do not non-violently accept their subjugation? What forms of violence are unacceptable and why? Where does violence really begin?

Dismantling oppression can only be achieved by questioning its very foundations and the language used to justify it; fiction, by enveloping us into a new reality—a new world with new rules—should make this questioning easier if we’re willing to divest ourselves of certain beliefs fed to us by those in power. BNHA, as imperfect as it is, certainly tries to raise some of these questions about the designations of “heroes” and “villains,” about the deserving and undeserving, about who is saved and who gets left behind. I would go further, and argue that to invest legitimacy into the hero system is to invest legitimacy into everything that perpetuates it: the poverty, the violence, the disposability of those judged “villainous,” and the idea that agents of the state are uniquely positioned to enact legitimate violence. Confronting crime means eliminating the need for it and the conditions that give rise to it, and only then, not a moment before, will the problem of villains largely cease to exist.

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sick Of Sisters

There once were three sisters.

All spiteful of each other, despite being born together. All conniving and callous toward each other. Constantly scheming the demise of their least favorite sister—which changed seemingly every day, dependent upon chance and temper.

To them, the other was a cancer inflicted upon their life, wreaking the sort of disruptive trouble a cancer normally causes. Draining all the energy and health of the sisters, whom were caught in this atrophic web, incapable of escaping except through death or feigned tolerance. Relationship as existential prison.

This is where the morphine came in.

At first, it was pragmatic precedent. The eldest sister—Marilee—had hurt herself in a horrible home accident. She was curling her hair in to impossible strides in a venal attempt to seduce a car salesman into selling a car without insurance, when she slipped on the bathroom tile, clobbering her neck on the ridge of the toilet, knocking her collar-bone out of tune, and slopping the heated curler onto her belly.

Momentarily immobilized from her snapped stabilizer, she was unable to remove the curler for quite some time, until the youngest sister—Marin—discovered her writhing in agony on the floor, saving her from further damage with a swift swatting of the curler, maiming her own hand in the process. But not before the imprint of the curler was seared onto the stomach-flesh like a sloppy cattle-prod, spurts of blood peaking under crusted scab.

The Good Doctor— all doctors are good, are they not? —prescribed a profound amount of medication to ease Marilee’s pain, providing her a nightly nectar of morphine upon which two of the sisters are now addicted.

The first one to consider abusing the substance was the middle sister—Marlo—who had always been envious of her other two sisters, concealing her envy behind a curtain of false confidence and sensual swagger, often pretending she was “too cool” to be bothered by anything concerning her “mules of sisters”—even though she was prone to copying them at every turn, whether in fashion item or darling desire or turn-of-phrase, stealing from them every parcel of her identity. So it seemed only inevitable she eventually stole the medicative goo when no one was noticing, installing in in her veins like caustic wires, until she was dazed and dwindling in an oozing circus of her own.

The other sisters, to no avail, could never make fun of their middle sister for anything she did, because although she was an actress of appropriation, she had always been the most attractive and popular to the opposite sex—a trait of being that the eldest sister measured with worth, and that the youngest obsessed over only if to impress her fellow sisters and not be outcast by their inclinations of how a female should conduct herself and value her abilities. The ability to persuade male mates into misuse and mischief was a value most regarded in this home of three sisters, none of whom had ever been married.

So when Marlo, in her devil-may-care attitude, took to the morphine like mosquitos to electric maidens, Marilee soon followed, claiming her rightful spot as the original recipient of the tonic, complaining of increasingly discomforting pain to the Good Doctor, who continued to prescribe higher and higher dosages. And on a certain level, it appeared as though the Good Doctor himself had no real condolements for the sisters, as they could be bothersome in viscous sums, so he waivered practical dignity and supplemented them with joyful juice out of hope they would leave him alone—and possibly someday die.

What the Good Doctor failed to apply in his summation was the wickedness of Marilee and Marlo, which included their exasperating aptitude for withstanding tremendous levels of punishment. And so, the morphine binge marched on, much to concern of the innocent and confused Marin.

“You will never find a man,” Marilee was quoted as muttering frequently to her poor sister, “if you continue to act like a field mouse!”

Then Marilee would hawk something at Marin; some type of nearby object, anything from an empty beer can to a holiday ornament to a raggedy shoe—anything within reach. Marin never fought back, unfortunately, mitigating the aches and sores with the assurance that her sisters loved her, and that she, too, should always love her sisters. And could you blame her?

The maleficent mother of these three sisters died while Marin was only three months living, crushed to crumbs in an intoxicated crash of which she perpetuated, driving the wrong way on a road through the wrong intersection, at just the right time to be plowed by an oncoming supply-truck—which of all things good-timing, had its brakes sputter out in that exact moment. It was almost divine in its machination.

So, Marin was raised by Marilee and Marlo, who never appreciated having another sister— one younger and infinitely more adorable in infancy than they ever were. And they detested being imposed upon by the chore of nurturing her from nakedness to nuisance.

Their father, a gambler with a penchant for gore, would stop by on occasion to check-in, bringing fortunes and gifts for his girls, staying for about a week or so, then slipping away back to his precious casinos. Marin enjoyed these visits the most—the other sisters couldn’t be bothered to display any sort of affection or gratitude—and as such, she received the grandest gifts, becoming her father’s favorite, vexing her sisters to tease and taunt and torment her after father left.

Marin accepted it, however, because they were the only family she knew, and they’d habitually remind her of that terrible fact whenever she made a mistake. Whether it was metal in the microwave or buying the wrong flavor soda-pop from the convenience store; plucking weeds not deep enough, or not cooking their meals to meet “standards and decency”. And even though the sisters poured all means of errands and petty tasks on her, Marin, from the moment she could walk, did all of them with a grace unfounded in children, and a starvation of sense in understanding how her sisters could treat her this way yet still love her.

They reminded her, with clops on the head every so often, while she was on her knees scrubbing gunk from the kitchen tiles or washing the aerial defecation from on top the roof in boiling sunshine, nipping the side of her ear with their counterfeit nails, spewing some nonsense like, “Remember how much we loved you? We took care of you when no one else would! And this is how you repay us? By missing spots? To hell with you, mouse!”

Another nip. She didn’t like being called “mouse”, so she worked harder and holier each time. Until her tiny paws were quivering from fatigue.

By the time Marin was eleven years, her ears were adorned with porous marks, leftover scars from every time she had missed a spot or performed inadequately. Which in hindsight was all the time without any discretion, seemingly at the whims of her sisters, who spent leisure fantasizing about suitors and sulfurous insults, nicking her as they passed in meditative waltz.

Marin kept on cleaning and cooking for her sisters, dreaming someday they’d reward her by showing her how to grow her nails long and cruel, with all the shades of a rainbow; or maybe how to puff up her lips and brows with cosmetic witchery, making herself look like a famous face, finally free to attract the whole world to her porch. She’d be just like them. But this dream never came true.

And now she was twenty-two years, never spoke to a man let alone been with one, never worn makeup or dresses, never been outside her home except on trips for groceries, most of her experiences and memories from the visible pane of floor and corner, a sponge in her hand, her life soaked in suds and sorrys, spurned by her sisters.

The three of them shoulder to shoulder in spite.

||

“Marin! The heat! Open a damn window!” Marilee hollered.

Marin sighed. It was snowing outside. But she did as she was commanded, for fear of reprisal from her overlord, pushing glass aside so flurried air could shoot its frosty venom in.

Marin shivered, ice-flecked fangs nearly cutting the freckles from her face. Luckily, she avoided this loss—she was the only sister with freckles, a special trait the others disdained. Marlo even went so far as to pencil-in artificial freckles of her own, acting as if they were contagious.

“Marin! The cold! Close the damn window!” Marilee shouted.

Marin sighed. She gripped the bandages on her right hand, trembling in overuse. The Good Doctor explained very clearly that Marin should evade any sign of pressure or purpose on her bad hand, for worry of straining the wounded areas apart. It burned in fizzy agony whenever she went against the Good Doctor’s orders, straight to the marrow, but nobody else was going to do her chores and keep this home from shambling.

Marin was most disappointed by the notion she would no longer be capable of clutching a knife, which she kept burrowed in her tomato garden. She found it in a dumpster she had been rummaging through after Marlo “accidentally” tossed Marin’s stuffed-moose—Marley—a gift from their late father that Marin had sanctified in her youth. Her incapacity for stabbing foiled her plan temporarily, upsetting her. The upset was worse than any physical ailment could be.

After finishing the recent demands of Marilee’s mood, Marin shrouded herself in a tattered-fleece and sallow-scarf, the freckles on her face dissipating in pallor complexion. In careful tact, she maneuvered gloves onto her paws, a mission made simpler by the many holes and frays. Her sisters updated their wardrobes every season, discarding previous incarnations to the garbage in disgust, lest worn clothing despoil their entire soul of spirit.

Marin meanwhile had the same set of garments that had lasted her for a decade, and being that she was petite and pure, she never much grew out-of-focus for these childish threads to fit her. Though they had scars of their own, Marin never protested. She was grateful to have anything at all.

Outside, away from the clatter and carrion, Marin wept.

There had been an awful, wintry storm going on for quite some time, encasing everything in a crypt of ice and frost. A haze had turned black and green and orange, waste and trash fusing with dead air, puncturing the adjacent woods, and the gutted entrance across the lot, where Marin often had to pass through to walk the road to the convenience store, which sold almost everything they ever needed except for companionship and morphine.

What a trial it was to do, carrying plastic bags brimming in useless toiletries and rotting fruits, through hail and heat and gusts. Marin’s arms felt disjointed from their slots every time she had to walk the groceries back, and it was too many times where the plastic containers stretched beyond belief and ripped open, tumbling its treasures to the ground and forcing Marin to make-do with whatever she happened to have on her.

Once, under spears of sleet, Marin had to remove her coat and wrap it up like a bucket, placing all her groceries in it and dragging them the remainder of the way home, flogged by freezing air the whole way. Because if she hadn’t, her sisters would have scolded her. They would have slashed her. Flicked her face and ears with those carved-claws of theirs, slicing her skin, leaving behind traces of whatever hue they were wearing that week, from furious fuchsia to jolly jade. “You stupid mouse! How could you forget everything? We sent you out there—it isn’t even that far!”

Their voices punctuated her every thought. Marin did nothing of her own volition. Every move and mile were made only in regard to how her sisters may react. And she was sick of it. Sick of them. Sick of herself for letting them sicken her. Sick of everything.

Marin grumbled, her stomach jangling in pain. As a child, she was always having spells of random nausea. It’s why her father only ever took her somewhere on a few occasions—her favorite place being the museum, where she awed at dinosaur frames and star-maps and mummified pharaohs, absolutely adoring these relics of time. The dinosaurs were her favored exhibit, inspiring such wonder in her to see these prehistoric titans, once rulers of the same ground she now walked on, still standing resilient, even if they were now nothing but bones. She wondered if after she was gone, if anybody would hang her bones up and be awestruck by this mouse that once existed and still does.

Of course, she vomited on the way there. And on the way back. But her father insisted she survive the trip. He explained to her that the world was a wonderful place, endless in its miracles, ceaseless in its reverent history. It was his duty to at least show her its wonders—if only for one time—so that she would have these murmurs of imagination to leech off for the duration of her life. Because, in his heart of hearts, he knew his time was nearing an end. And he knew the malice of his own daughters. But Marin was supposed to be different.

And here she was, hiding outside in the snow, shivering and shamed and soured.

Her tears were a gas in the frigid afternoon. And her memories were a bullet to her brain, shooting through her entire body in prickly misery.

Marin stepped close to the edge of their lot, looking back at their trailer-home, covered in grime, practically glowing in the darkness; then stared longingly into the woods, as far as permitted by the storm, through naked trees and pined ones, standing in diametric dalliance, stripped of their color but standing the same way they always stand, unmoved by any force. She watched for signs of life. Sometimes she’d see a fox wandering through. Maybe a deer, if it had been quiet. And yes, even mice, scuttling from root to root, swifter than she could ever be.

She didn’t feel like a mouse. She had never understood why her sisters referred to her as one.

Marin examined her paws, shaking in the cold. Half of her fingers were bent, joints bristling away. Her nails were fractured, chipped in at random junctions, dirt and gunk rolled in them as if rolled in blankets, sleeping. The filth seemed comfortable there. Her right hand was stitched in bandages, spotted and soiled; their ends taped on after falling apart.

But Marilee was given new wrappings every day, and Marin had to traverse to the convenience store and back to bring her sister clean and sterile padding. But she herself wore the same saggy rags, every day.

Her paws were not nimble; they shuddered. Her paws were not swift; they lagged in lethargic weakness. She had freckles instead of whiskers. A bony-butt instead of a tail. She had no fur but skinny strands of hair, not even layering her whole body, which was brittle and bare anyway. Her teeth were crooked and putrefied, preventing her from biting most foods, which was just as well since all her sisters ever fed her was soup and mush. When they gave her the list for groceries, it was only ever enough for two. And the money was only ever enough for what was on the list.

Marilee, as much of a scoundrel as she was, always cooped up in the house, always irritated, seething at Marlo for always being out on dates and dinners, living the life of lies she once lived, when she was younger and prettier and her crabbiness was manageable and somewhat buttery—even in all her sullen squalor, Marilee had a precise mind, a tactical thinking, and it served her well in doling out only the bare minimum necessary tasks and necessary payment for Marin to deal with. Only the necessary amount for two sisters instead of three.

But there were three of them.

All harboring in that shackled abode of theirs. Passing seasons in continuous strife. Bickering—they loved bickering.

Marilee and Marlo engaged in contests of yelping and critical strikes almost daily. Marilee thought it disrespectful Marlo was always stealing—"borrowing”—her dresses, jewelry, makeup. Marlo thought it distasteful that such pleasant garments and ornaments should go to waste on such a petty, poisonous tree as her sister. And then there was Marin, meshed in the barbs between them, agent to them both, bandaging the wounds of their relationship while mitigating the worst injuries.

Because no matter how fiery Marilee and Marlo became toward each other, the consequent combustion always seemed to have a way of spilling over unto Marin, until finally Marilee and Marlo were both quite certain it was Marin whom they had been fighting against all along.

But outside, in the lonesome cold, the musty frigidness of a world decaying in tune, nobody blamed Marin for anything. Nobody could claim she did a poor job or that she lacked courage or that she was nothing but a squabbling mouse scrambling for crumbs. Out here, she was as uninteresting and unnoticed as a branch. Just another limb on the body of nature. It was calming, meditative. Marin took time with her breathing out here, inhaling so deep through her nose and mouth sometimes she would accidentally snort or hiccup.

So, she clung there, wading around the mounds of trash and piles of discarded vehicle gears. When suddenly, something scraped against her nostrils. A hideous smell—caustic and mushy. Marin winced, forming a shield around her nose with her little paws, trying to replace this odorous odor with one of her own flayed skin. Underneath the bandages, even under the scabs, her sores still danced with the pungent aroma of old blood and burnt skin. Anything was superior to this other scent, however—one of revolting ruin, of putrid pall.

Marin peered from one corner of the clearing to the other, when she realized the origin of the smell. Despite the ugliness of it, she sucked up personal disgust and peeled only two slight fingers apart into a slit, sniffing the source of the smell, following its rotting chain to its forsaken soul.

Over by the edge of the makeshift lawn, there was a metal bin, meant for industrial junk, but which the sisters had become accustomed to dumping all manner of trash in, especially liquor bottles and lipstick containers and ointment rags and leftover food they had let rot over for too long, either forgetting to eat it or just refusing to bother with them. Instead of sharing with Marin—as was typical—they would dump it in the barrel and send her to the convenience store to pick up more for supper. “Why are you begging for this filth? Huh. Just like a mouse, all you ever want to eat are scraps!”

When Marin was younger and weaker, she had a habit of sneaking out late at night, to fish out remains, picking at the parts still edible and least likely to sicken her. But what was there now seemed too sickening.

Approaching the tin bin, Marin was cautious not to let slip her mask of fingers, for fear she might suffocate from the smog. Her eyes began to sweat. If only she had more paws—a normal mouse has four.

Marin, with the wariness of a spider snatching eggs from a bird nest, leaned over and looked in. Abomination.

On the bottom rung, a smoldering cluster of shredded flesh and coiling bone, rusted, ravaged. The cavity of its chest hollowed-out, the bite-marks of fanged feasters and mauling maggots, halted halfway, as if the hoary night had frozen their procession in place. Its surrounding body remained in remains, skin shrunken so as to appear sinking between bones, its fur whittled away, spoiling in some spots and moldy in others, drained to a gross paleness, almost grayish-green, like swamp-muck turned to stone.

Marin could recognize it had been an animal at some point, observing its four legs now bent inward, wilting. And it had a tail, which was now a patched effort, skinny and sallow, craters of flies and worms still reminiscent on it.

Then she examined its head, whose covering had shriveled so much, it was more like a pastel skull, cheekbones and maw-ridges and sunken sockets, fleeced by a thin-layer of skin so emaciated and tarnished, it was impossible to imagine it had ever been a face.

To Marin, it reminded her of the skeletal mannequins she once admired at the museum. Unable to determine what kind of animal it was, she thought maybe it was a dinosaur. A long-lost primal beast, reduced to worthless size by time and commotion, the world a mess of monkeys and mice, vying for the same room. This was something that belonged in a museum.

Marin was so mesmerized, she removed her hand, and for a splitting moment the smell ceased to be smelt. She was entranced by this faded form, which had withered to its internal frame while still wearing the cloak of its dermal costume, like a ghost clinging to its corpse, even though the soul was now detached from the body and there was no coming back—no reattaching. She looked down at her own fleece, which she had outgrown, which was battered by tears and frays and splotches of obliterated dye. Then she gazed at her hands, beneath the gauze and speckled sound, how close her bones had come to the surface, her joints and appendages now more visible than her actual skin. And this haunted her—her own form fading.

Marin nearly disintegrated into the snowy ground, this disparaging despair causing a dissolution of herself. She cramped over, her stomach bubbling, sitting in the snow among trash and ash and mud. But she had no concerns about being damp or dirty or cold. She stared, at no particular direction or object—just staring because she wasn’t sure what else to do with her eyes. But she couldn’t close them; they were swollen from the sting.

Her fingers trembled, as they were prone to doing, but this time it was different—this time it was a body-quake, shaking and cracking her open. Marin huddled in the snow-stained dirt, her spirit in shambles. The little mouse had tripped herself.

She burped. Gases were mingling deep inside her. A nervous existentialism swirling in her stomach. And a sickening radiance overtook her—some hideous light, rays convulsing deep within her.

She expelled everything.

It spouted out from her mouth, thickening through her body as if a tree was sprouting from her intestines to her nose, filling her with heavy boughs, replacing veins with branches. She couldn’t breathe. And straight onto snowy surface, a splattering flurry of pungent-chunks and noxious-slime—a mess of eaten nature rebounded to its breeze.

Marin kneeled over her bodily puddle, writhing in strangely warm numbness. She finished, heaving every last drop of poison from inside her, her chest frozen in aching shock, barely able to find her first breath before gulping it down and choking on it again, broken on all-fours in remarkable ruin. Only moments after it was all done, did Marin lean over, panting; all the pain and displeasure expunged from her, feeling somewhat normal again, as if nothing had happened, just slivers of it in the way every breath still seemed desperate.

Marin recovered from her shock, as if it didn’t even happen, in the same way the earth pretends it wasn’t once swarming in terrible lizards and giant sharks. As if fossils were manufactured in a factory somewhere, for the sole purpose of populating museums to entertain people who take for granted how short their time on this planet really is. And Marin considered this thought, luring herself into the dark depths of doubt.

But she stopped, rescuing herself from further discourse, assuring herself there were most certainly dinosaurs roaming the earth, and most certain of all that things deceased are not simply forgotten. Because at the nougat of Marin’s anxiety was worry that she herself would be forgotten. Even after all the struggle and pain she wallowed through, thinking eventually some culmination of compensation would present itself, that to think everything in her past was actually fleeting and futile, that it was not in fact a crescendo but rather a flat-note existence—this most of all frightened her. The broken never being repaired. The servant never being rewarded.

The mouse never being given its cheese.

“Marin! Marin, where you are? Where have you gone little mouse?” Marilee shouted.

Marin perked up. Her sister came dashing out of the house, leaping from the porch barefoot, unchained from coldness. Her face was pallid and dripping, bland saliva painted onto her chin, eyes stretched by tentacles of blood, nostrils peeling snot-icicles at whim. She looked like a moving statue, tense and torpid. How she always looks these days.

But Marin limbered up. Something was different.

“Marin, call the Good Doctor. I don’t feel right—goddammit, I don’t feel right at all!” She shrilly muttered.

Yet, she was still caked in cosmetic frosting, appearing like a decorative tree whose branches and bark are spoiled and rotten behind a façade of kitchen-kitsch ornaments. Marlo often referred to her as a clown, runaway from the circus. This is how most of their arguments began.

“Listen you rodent, I—” Her scaly claws dug into Marin’s arms, pinching her already frail skin to the limit of perforation. Marin winced. Her sister’s eyes swallowed behind their icky ink, suddenly buried in a moldy-white. Then she collapsed to the ground.

Marin gasped, scurrying to the aid of her sister. Black-brine leaked from her lips, with a fuming foam seeping from her nostrils, her body so depleted of normal nutrients, which had been eroded away in her all-morphine diet, any fluid dripping from her lacked blood or color. She was bleeding residual leftovers. Her eyes were dead and drained.

Marin whimpered, a sea of veiled blood swarming around her freckles. She wasn’t sure what to do.

“Sister? Sister? Should I call…?” Marin whimpered, half-legible as her throat swelled and heart stampeded. As she held her sister, something peculiar happened. Marilee’s mouth curved into a serpent grin, and through her last gull of breath, she mumbled to Marin, “Don’t you worry, sister. We’re finally done.”

Marilee chuckled like a goblin, her fangs shimmering in the holiday stream, a rainbow of dim reds and greens and yellows and blues.

“Sister. Sorry. I love you.” Marin assured her that she loved her sister, not just because she was her sister, but because she was compassionate and caring and concerned.

And dead.

Marin remained there, shuddering in solemn scum. No heartbeat. Marin wept for her fallen sister; a piece of genetic memorabilia wiped from the scrapbook of living. The feeling of a corpse—it hurt Marin more than any punishment or wound she ever endured. She staggered up again, dragging Marilee’s body back into their house. Then Marin sunk onto the floor, fatigued by fate, by fear, by finality.

All Marin could think about is what her sister’s skeleton would be like displayed in an exhibit. What would they call her? The Serpent? Marin refuted this conception. Her sister did not have the cunning of a snake, even if she thought so. No, if they were to put Marilee on display, it would be as a vulture—a vulture chasing a mouse.

Dreary lights pierced through the shadowed room. Marlo had arrived home, presumably dropped by whatever new beau she had been entertaining for the night. Marin panicked. How could she explain such a fantastical occurrence?

Not that she had done anything wrong, but, well, Marin had a habit of being the subject of trouble and always assumed to have done the wrong thing when anything else would have sufficed. Maybe that was just the opinion of her sisters. Marin didn’t think about that now, however. Her blood and flesh had just left life in her own paws. The worthless mouse couldn’t salvage anything.

Marlo entered, swooning over her date. A spinster no more, perhaps? So, what a sight it was to see Marin huddled on the floor, quivering like a scared child, Marilee’s body flung across the room, limbs jaggedly sprawled and bitterly dark froth collecting around her head. Marlo screamed.

“What…? What did you do? Marin!” Marlo shrieked her sister’s name. Marin flinched. “What the hell did you do?!”

Marin, sniveling, couldn’t say a thing, rendered a mute by a flood of panic. Marlo rushed to her, her pincers clamping on Marin’s left ear, to which she finally found sound and released a tremendous whine.

“Please, please, please, it hurts!” Marin pleaded. Marlo hung Marin to her feet, a faint murmur of blood whistling across her nail and down her finger.

“What happened here, little mouse? Tell me the truth or God help me!” Marlo commanded.

Marin winced, her ear a trapeze of pain. She couldn’t explain—she herself didn’t even know what happened. Marlo’s patience burned to its final wick, however, and she shoved Marin down on the couch, a violent glare, then she examined Marilee’s body.

After, she sighed. And Marlo took a seat beside Marin, her emotional state transmuted to something entirely different, her anger and sullenness washed over by shades of volatile disappointment and uncomfortable relief.

“It’s not your fault,” Marlo murmured, staring at Marilee, while Marin rubbed her cut. “It is nobody’s fault.”

Nobody said anything. It was the first time this house had ever experienced such fractured silence.

Nauseous anxiety buoyed in Marin’s tummy. She closed her eyes, erasing the image of her sister’s deceased silhouette; she ignored the throbbing pain of her bleeding ear; she focused on a shard of memory, a vision from a time so long ago she doubted whether she had actually lived it at all.

In the museum. Her least favorite part. A section that wrapped around tubular barricades, static aquariums of plastic prehistoric fish and fauna carved into the cement walls, lights dimmed and receded, a sparse dark. At the end of this aquatic tunnel was a gigantic wall, enshrined with the molding of an ancient leviathan, behind it glistening vertical strains of deep ocean, partial artificial sunlight painted on, dropping to unfading black. And Marin standing there, a small mouse, directly in front of these behemoth jaws, slabs of unchipped gray, surrounding a gargantuan hole of darkness darker than the deepest elegies of space.

If there were eyes, they were meaningless lamplights compared to the sheer earth-swallowing pit of nothingness that was its mouth. It was the only part of the exhibit she was truly frightened of—the thought of being mindlessly swallowed up by this monstrous thing, without even being bit or chewed, without even having a chance to swim away. And she resented this memory, because she remembers when she was standing there, lost in the gape, so afraid, she soiled herself, and all the other passersby pointed and giggled and laughed at her.

This was when her father came and knocked one of the other fathers in the nose and there was shouting everywhere. That’s when she had to ride home in the back of a police vehicle. It’s when someone actually gave a damn enough to protect her.

As Marin opened her eyes, Marlo sobbing in her lap, embracing her sister, Marin had the most curious instinct of latching her arms around her sister in an affectionate—rather than hateful—manner. There was no more trouble.

Marin wanted to ask Marlo if she would ever let her slip away. Into the fade. Or if she’d have the decency of contributing her fossil to a museum. So she could live on forever—not as a monument to fear and darkness, but as a reminder of life and love, even in the corners of something as quiet and little as a mouse. But then Marin began crying fabulously furious tears, thinking to herself, Who would ever want to look at the skeleton of a mouse?

“Don’t cry, Marin. Save your energy. I still need you to clean up this mess.” Marlo disappeared into the kitchen, scrambling to find whatever remained of the morphine.

There were three sisters. Now there were none.

[old story, circa 2017]

1 note

·

View note