#whereas with prometheus... on the one hand it seems like he is asserting it... but he's also asking

Text

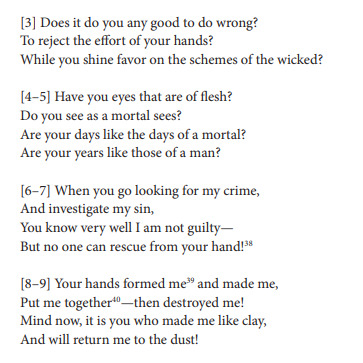

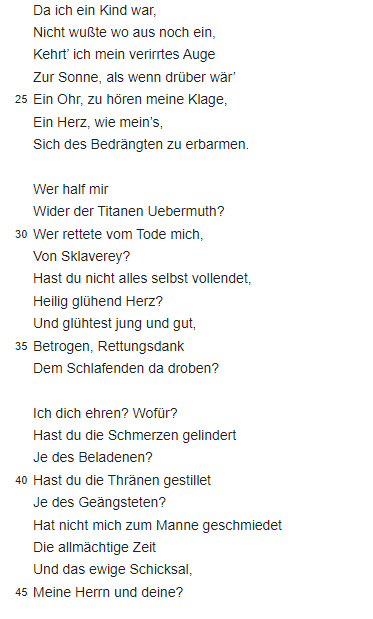

Book of Job, trans. Edward L. Greenstein

Prometheus, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

#words#a) man angry at god is my absolutely favorite genre of poem#and b) ITS ABOUT THE JUXTAPOSITION!!!!!!#literally i could write an essay about it#both of them looking for physical signs of humanity in god#(hiob still hoping for eyes whereas prometheus has long since given up on looking for a heart)#hiob asking how god experiences time#whereas with prometheus... on the one hand it seems like he is asserting it... but he's also asking#that time is zeus' master#and of course... the main difference#your hands formed me#(btw the footnote on that says the verb root connotates pain!!!!)#vs prometheus flat out rejecting this possibility - I made me and fate made me but YOU didnt#but also hiob's anger at god's action vs prometheus anger at zeus' inaction#this is a dialogue actually except its a trialogue where one party is God and therefore silent#except of course that he will answer#very differenetly for both of them - zeus will damn prometheus and god will reconcile with hiob#(maybe it was smarter for hiob to look for god's eyes to fairly judge his crime rather than his heart to have compassion)#(or maybe it was because hiob was innocent and prometheus was guilty!!!!)#also i just looked it up the original myths came about roughly at the same time around 500 bc#anyway its literally the middle of the night but im going crrrrrazyyyy a

1 note

·

View note

Text

Umbrella Pantheon pt. 2

This covers many of the minor deities and obscure characters in re8 that don’t get touched on too much. As a result there was more room for me to stick my own bullshit onto them. A lot of inspiration i took from the wiki of some of these guys and adding back in some cut content just cuz its fun. These are the guys I really enjoy, the main cast is fun (and we’ll get to the Winterses soon), but having side characters I can just make shit up about is very fun.

The Uriaș Brothers / Gods of Kinship, Protection, and Culling / Alpha and Omega / Sentinel and Outrider / The Grey Pack

The Uriaș brothers are demigods who serve as pack leaders over the pack of werewolves. Vanatoare, the younger who leads hunts with his pack, and Străjer who is bound to protect the Grimm Egg. They were once an order of great knights that looked over their domain with justice and they were prime candidates for godhood in Miranda’s eyes. They became mighty warriors but unlike the Four Lords they had a very difficult time exerting control over their god forms. The other knights of their order believed that they could share the load of godhood between all of them and indeed the two brothers had more clarity, but the mundane-blooded knights were all transformed into beasts and werewolves. Some were able to retain enough insight to ride their steeds and wear armor but all others became barbarous with the most weak-willed becoming giant and savage wolves. The Uriaș brothers were saddened to see how their comrades had fallen and even lost themselves on occasion. They try to coordinate their hunts with enemy fortresses, or places that were deemed to be guilty of some crime in the eyes of their lords, in order to stave off the guilt of their savage hunts. Those with strong wills and power, like all of the upper gods or the Duke, can assert themselves as above the pack which they will respect.

The Uriaș Drac / Devil Giants / Twin Demons

The twins in the Uriaș family who completely relished and embraced their beastial nature. They inherited none of the lupine traits of the werewolves besides their voracious appetite choosing to hunt and eat innocents. They think they chart their own destinies but are frequently manipulated by the Lords to do their bidding. But one of the two, Îndrăgostit Uriaș, is enamored with Beneviento and will, by what he thinks is his own will, guard the grounds and fend off trespassers. Bucătar Uriaș, the older twin, focuses more on the cuisine and cooking side of his cannibalism.

Sturm Heisenberg / Demigod of Destruction / The Iron Storm / Forsaken Father

Karl was not taken but did not willingly go into Miranda’s arms, he was sold by his father, Sturm. He squandered his knowledge of clockwork and tinkering and hardly taught his son a thing besides pain. Instead he used his money for drinking and nearly destroyed the family business. Karl Heisenber came back with a vengeance and subjected his father to the most unholy side of his godlike power. He made him into even more of a destructive figure, a demi-god of Desolation, and threw him into his metal labyrinth where he now desperately reaches out his arms not to beat, but for anyone who would help him. Yet he is unable.

Miłości Norshteyn / The Sculptor / Maker of the Exalted Tombstones

A meek, artistic husband who was a part of a polycule including four warrior goddesses. He was considered a heretic and traitor to the gods and pantheon of the region he was from before and was banished, eventually arriving in Leagăn. He was tricked by a god and through his actions allowed for his wives to be killed and their remains were calcified. When he traveled to Leagăn he found that the four lords all had traits resembling his wives. He created complicated statues and sculptures resembling their domains that even the god Heisenberg was deeply impressed with. He locked their remains beneath their intricate tombstones. The minerals of these fallen gods could all be used to forge mighty weapons but Norshteyn rigged them with traps and checks up on them to avert grave robbing.

The Duke / Vast Merchant / The Owl / God of Commerce and Favor

Duke is a trickster god that not a lot of people fully realize. He turns into an owl for long travel carrying his cart within his talons. He is a deity that is separate from Miranda and the Dark God, which infuriates her, but she suffers his existence until a time where she can dispose of him and his wiles. He originates from a distant land and even has made trade with other minor deities but maintains his demeanor of a humble, jovial figure who delights in cooked foods. Giving the god a delightful treat or meal is a surefire way to gain his favor, but he will still feign politeness even if the meal is burned a bit. Whereas Heisenburg is far more heavy handed in his shadowy rebellion, The Duke maintains an air of aloofness to any and all conflicts and makes his favoritism a mystery, rather choosing to make any form of aid seem like something he was just going to give away in any case. He has the ability to convert any coinage to a different mint, but keeps some original coins for keepsakes.

Ucigaș / Blademaster / Grave Gardener

A lowly merchant and servant in Dimitrescu’s domain, until his family was chosen to be taken to her castle and never to be seen again. He sought out a way to receive vengeance on the god and on his journey was approached by the Dark Prometheus who stated that a dragonslaying weapon could be created but only when components from three of the Four Deities was collected: A special alloy for the dagger from Heisenberg, a special flower grown in Beneviento’s Personal Garden, which was to be synthesized with the bile from Moreau to create the poison. This long and arduous task led to the creation of the Dagger of Death's Flowers.

Ucigaș failed in the end and was struck down by the dragon. But she held a modicum of respect for him as she knows what it is like to lose daughters and recognized she caused it. So she sealed him and his weapon away in respect of the would-be dragon slayer. But the dagger would be picked up once again by the fated Cold Night, the Winter.

The First Demon and the Sword Maiden

Some of the most obscure figures in Leagăn’s history. One day an angry drunk found his way to the cradle while in a fury and came upon Necros. He tripped and fell into its embrace and came out a thing that could only be described as a demon. It returned to the place it called home and began to feast upon the people there. All soldiers were tossed aside and devoured, until a goat approached it and the demon began to cry and scream, batting at it and beheading it in the process. A young maiden saw this and remembered the names that were used towards the town drunk; “Goatfucker”. She looked into its eyes and saw that the demon’s eyes were his. She took up a sword and strapped the goat's head to a shield and fought against the demon for a day and a night as it trembled and flailed. Villagers could only look on as this woman who seemed to be battle incarnate.

She finally felled the beast covered in its blood and its calcified remains were used to create a statue in the maiden's likeness: wielding a sword and a shield with a goat's head on its face. Few reports tell of a black wound on her side given by the beast, seeing it she ran into the sun of the dawn. Necros would remember her. Some believe that the maiden will be reincarnated into another young woman who will be just as mighty. This came true in the form of War Incarnate and the One Part Mother: Mia Winters.

#resident evil#resident evil village#urias#urias strajer#sturm#re8 au#umbrella pantheon#The Duke#Norshteyn#*sees there's no lore for obscure characters and figures* Its free real estate

19 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Ozymandias BY PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY

Ozymandias" is a sonnet written by English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, first published in the 11 January 1818 issue of The Examiner in London.

A poem to outlast empires.

BY DAVID MIKICS

Shelley’s friend the banker Horace Smith stayed with the poet and his wife Mary (author of Frankenstein) in the Christmas season of 1817. One evening, they began to discuss recent discoveries in the Near East. In the wake of Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt in 1798, the archeological treasures found there stimulated the European imagination. The power of pharaonic Egypt had seemed eternal, but now this once-great empire was (and had long been) in ruins, a feeble shadow.

Shelley and Smith remembered the Roman-era historian Diodorus Siculus, who described a statue of Ozymandias, more commonly known as Rameses II (possibly the pharaoh referred to in the Book of Exodus). Diodorus reports the inscription on the statue, which he claims was the largest in Egypt, as follows: “King of Kings Ozymandias am I. If any want to know how great I am and where I lie, let him outdo me in my work.” (The statue and its inscription do not survive, and were not seen by Shelley; his inspiration for “Ozymandias” was verbal rather than visual.)

Stimulated by their conversation, Smith and Shelley wrote sonnets based on the passage in Diodorus. Smith produced a now-forgotten poem with the unfortunate title “On a Stupendous Leg of Granite, Discovered Standing by Itself in the Deserts of Egypt, with the Inscription Inserted Below.” Shelley’s contribution was “Ozymandias,” one of the best-known sonnets in European literature.

In addition to the Diodorus passage, Shelley must have recalled similar examples of boastfulness in the epitaphic tradition. In the Greek Anthology (8.177), for example, a gigantic tomb on a high cliff proudly insists that it is the eighth wonder of the world. Here, as in the case of “Ozymandias,” the inert fact of the monument displaces the presence of the dead person it commemorates: the proud claim is made on behalf of art (the tomb and its creator), not the deceased. Though Ozymandias believes he speaks for himself, in Shelley’s poem his monument testifies against him.

“Ozymandias” has an elusive, sidelong approach to its subject. The poem begins with the word “I”—but the first person here is a mere framing device. The “I” quickly fades away in favor of a mysterious “traveler from an antique land.” This wayfarer presents the remaining thirteen lines of the poem.

The reader encounters Shelley’s poem like an explorer coming upon a strange, desolate landscape. The first image that we see is the “two vast and trunkless legs of stone” in the middle of a desert. Column-like legs but no torso: the center of this great figure, whoever he may have been, remains missing. The sonnet comes to a halt in the middle of its first quatrain. Are these fragmentary legs all that is left?

After this pause, Shelley’s poem describes a “shattered visage,” the enormous face of Ozymandias. The visage is taken apart by the poet, who collaborates with time’s ruinous force. Shelley says nothing about the rest of the face; he describes only the mouth, with its “frown,/And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command.” Cold command is the emblem of the empire-building ruler, of the tyrannical kind that Shelley despised. Ozymandias resembles the monstrous George III of our other Shelley sonnet, “England in 1819.” (Surprisingly, surviving statues of Rameses II, aka Ozymandias, show him with a mild, slightly mischievous expression, not a glowering, imperious one.)

The second quatrain shifts to another mediating figure, now not the traveler but the sculptor who depicted the pharaoh. The sculptor “well those passions read,” Shelley tells us: he intuited, beneath the cold, commanding exterior, the tyrant’s passionate rage to impose himself on the world. Ozymandias’ intense emotions “survive, stamp’d on these lifeless things.” But as Shelley attests, the sculptor survives as well, or parts of him do: “the hand that mocked” the king’s passions “and the heart that fed.” (The artist, like the tyrant, lies in fragments.) “Mocked” here has the neutral sense of “described” (common in Shakespeare), as well as its more familiar meaning, to imitate in an insulting way. The artist mocked Ozymandias by depicting him, and in a way that the ruler could not himself perceive (presumably he was satisfied with his portrait). “The heart that fed” is an odd, slightly lurid phrase, apparently referring to the sculptor’s own fervent way of nourishing himself on his massive project. The sculptor’s attitude might resemble—at any event, it certainly suits—the pharaoh’s own aggressive enjoyment of empire. Ruler and artist seem strangely linked here; the latter’s contempt for his subject does not free him from Ozymandias’ enormous shadow.

The challenge for Shelley will thus be to separate himself from the sculptor’s harsh satire, which is too intimately tied to the power it opposes. If the artistic rebel merely plays Prometheus to Ozymandias’ Zeus, the two will remain locked in futile struggle (the subject of Shelley’s great verse drama Prometheus Unbound). Shelley’s final lines, with their picture of the surrounding desert, are his attempt to remove himself from both the king and the sculptor—to assert an uncanny, ironic perspective, superior to the battle between ruler and ruled that contaminates both.

The sestet moves from the shattered statue of Ozymandias to the pedestal, with its now-ironic inscription: “‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings./Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’” Of course, the pharaoh’s “works” are nowhere to be seen, in this desert wasteland. The kings that he challenges with the evidence of his superiority are the rival rulers of the nations he has enslaved, perhaps the Israelites and Canaanites known from the biblical account. The son and successor of Ozymandias/Rameses II, known as Merneptah, boasts in a thirteenth-century BCE inscription (on the “Merneptah stele,” discovered in 1896 and therefore unknown to Shelley) that “Israel is destroyed; its seed is gone”—an evidently overoptimistic assessment.

The pedestal stands in the middle of a vast expanse. Shelley applies two alliterative phrases to this desert, “boundless and bare” and “lone and level.” The seemingly infinite empty space provides an appropriate comment on Ozymandias’ political will, which has no content except the blind desire to assert his name and kingly reputation.

“Ozymandias” is comparable to another signature poem by a great Romantic, Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan.” But whereas Coleridge aligns the ruler’s “stately pleasure dome” with poetic vision, Shelley opposes the statue and its boast to his own powerful negative imagination. Time renders fame hollow: it counterposes to the ruler’s proud sentence a devastated vista, the trackless sands of Egypt.

Ozymandias and his sculptor bear a fascinating relation to Shelley himself: they might be seen as warnings concerning the aggressive character of human action (whether the king’s or the artist’s). Shelley was a ceaselessly energetic, desirous creator of poetry, but he yearned for calm. This yearning dictated that he reach beyond his own willful, anarchic spirit, beyond the hubris of the revolutionary. In his essay “On Life,” Shelley writes that man has “a spirit within him at enmity with dissolution and nothingness.” In one way or another, we all rebel against the oblivion to which death finally condemns us. But we face, in that rebellion, a clear choice of pathways: the road of the ardent man of power who wrecks all before him, and is wrecked in turn; or the road of the poet, who makes his own soul the lyre or Aeolian harp for unseen forces. (One may well doubt the strict binary that Shelley implies, and point to other possibilities.) Shelley’s limpid late lyric “With a Guitar, to Jane” evokes wafting harmonies and a supremely light touch. This music occupies the opposite end of the spectrum from Ozymandias’ futile, resounding proclamation. Similarly, in the “Ode to the West Wind,” Shelley’s lyre opens up the source of a luminous vision: the poet identifies himself with the work of song, the wind that carries inspiration. The poet yields to a strong, invisible power as the politician cannot.

In a letter written during the poet’s affair with Jane Williams, Shelley declares, “Jane brings her guitar, and if the past and the future could be obliterated, the present would content me so well that I could say with Faust to the passing moment, ‘Remain, thou, thou art so beautiful.’” The endless sands of “Ozymandias” palpably represent the threatening expanse of past and future. Shelley’s poem rises from the desert wastes: it entrances us every time we read it, and turns the reading into a “now.”

The critic Leslie Brisman remarks on “the way the timelessness of metaphor escapes the limits of experience” in Shelley. Timelessness can be achieved only by the poet’s words, not by the ruler’s will to dominate. The fallen titan Ozymandias becomes an occasion for Shelley’s exercise of this most tenuous yet persisting form, poetry. Shelley’s sonnet, a brief epitome of poetic thinking, has outlasted empires: it has witnessed the deaths of boastful tyrants, and the decline of the British dominion he so heartily scorned.

#the crossing#david 8#walter#percy bysshe shelley#ozymandias#poetry#sonnet#alien#aliens#alien 3#alien resurrection#alien covenant#prometheus#yutani assets#david8#space horror#philisophical scifi#philisophical science fiction#scifi horror#science fiction#michael fassbender#alien: covenant#alien movie#alien film#alien prequel#alien covenant analysis

10 notes

·

View notes