#wilbur wright (affectionate)

Text

The wilbur soot subreddit seems to be going well.

#I was going to include some of the memes regarding the incident iself but i feel like its too soon#Wilbur soot#(derogatory)#Wilbur wright#(affectionate)#mcyt

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Four Short Stories

I’ve been sharing quick, minimally constructed stories with my friend Peter, as a way of batting away the rust around my writing. Now that I’ve sat with them for a week or more, and tinkered with them not at all, I’m ready to graduate them to Duck Beater, my horcrux, I mean my blog.

I HAVE RECENTLY MET SOME VERY POWERFUL GODS

Oh, I stopped going. I gave up the gym because I wasn’t changing. What was my libido then? Tortured, I think, by coltish undergrads in form-fitting sweatpants. Weirdly, I noticed my mood improved if I looked at dogs. If I saw beautiful, loyal dogs in the evenings, open and knowable and kind—I felt my soul swell with every passing. It was a harder kick than studying strangers on the stationary bikes ahead of me. Weirder still, I developed a kind of superstition about these dogs on my nightly jogs. I sought them out, for the contact high. I would say to myself, “I’m gonna see five gods tonight.” Gods not dogs. “I’m gonna see six gods tonight.” I didn’t need to touch them but I did need to pass them and look into their eyes. “I’m gonna see seven gods tonight.” Anyway. That’s why I run outside.

PERFECT GAMES FOR COWORKERS WHO ARE IN LOVE

This one is called “Be Messy, Make Mistakes,” so named for the legend on a coffee mug. The rules are simple:

Wait for it.

Wait a day more for it.

The comparison rankles, but it’s impossibly obvious: Your design lead looks like a young Joseph Stalin (of the 1902 mugshot). Same wavy hair, oiled and swept away from the face, the sides short enough to reveal perfect “number 6” ears. Then the well-groomed beard; the merry dark eyes; the propensity for scarves worn under woolen coats, slightly too large.

Say: “You look like a young Joseph Stalin.” There’s no taking it back. “See.”

Present the results of a quick Google search (two tabs you’ve already opened).

“That’s pretty wild!”

“You’re really a dead ringer.”

“Well, my family’s Russian.”

“Mm, so—so there could be—”

“A history that ties me to a war criminal, yes.”

You’re sitting side by side now with the perfect excuse to study his face, then the face of young Soso. For this photo, the Okhrana picked up Stalin just after the Batumi Massacre, and his expression, you find, is alight with the flame of revolution. For the sake of comparison, you're allowed to stare deeply, dreamily into your design lead's eyes again.

While he’s here, review some of the updated marketing collateral. Every item earns an affectionate knee touch. (Seriously, he taps your kneecap.)

You say, “New photo.”

He taps.

You say, “Colors print ready.”

He taps.

You say, “Ts and Cs.”

He taps.

Neither of you wins if he leaves his wife and kids.

WHEN THE SHARK BITES

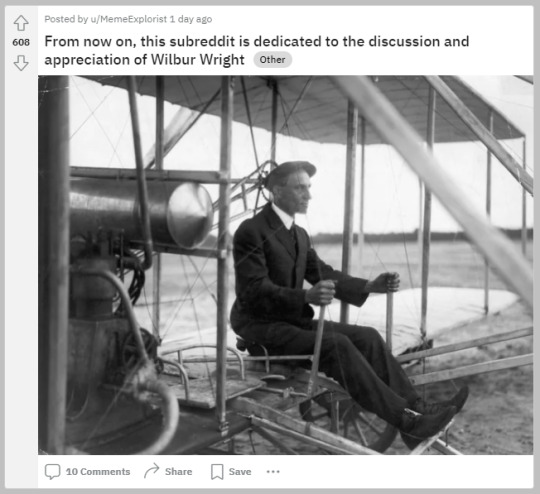

One narrative that preoccupied me during my first serious relationship had to do with the Wright brothers—what the brothers were like as gawky teens. How they celebrated Halloween, where they rode bikes, cemeteries they explored on dares—that sort of thing. I was just out of college and crushing, apparently, on Wilbur, whose photo I’d seen at the Wayne County Historical Museum. I hungered for anachronism. I hungered, too, for love, and so gobbled up a dashing young man in Mississippi. While he fulfilled his tenure in Teach for America, I waited tables in Ohio and, when the spirit moved me, drove out to Dayton to explore the Wright archives.

This was a long time ago, when I was really into Thomas Pynchon and took everything for a sign. Everything conferred a “storm system of group suffering and need,” and there I was, pockets full of cash tips, full up of suffering and need, lamenting the distance from my lover and staunching an uncanny stream of rejection letters from graduate writing programs. Nobody wanted to fund my historiographic metafictions. And who could blame them.

The Wrights were awkward teenagers torqued more fabulously awkward by their mother’s slow death, their father’s increased absences, and the unsuccessful pursuits of their older brothers, who seemed to fail at everything they tried. Wilbur and Orville read widely enough to know their fortunes were unhappy (indeed, they sometimes signed their letters “Smike”). They lived in a small, comfortable city that elevated their ambitions to a high, miserable plateau, and their attempts to paper over poisoned circumstances—to write themselves an antidote—became a project that possibly saved themselves and their younger sister Katherine from fates like those in Dickens’ sentimental tragedies.

The stories I wrote, taken all together, would form The Falconers, a psychological novel that connected slender, depressed fellows to future, strapping heroes. How do lowly men become legends? How do cycling-obsessed boys conquer the skies? (It was that kind of story, with zits.) Thrillingly, my boyfriend moved to Falconer Avenue, just across from the middle school in Holly Springs. Every other month I made the eleven-hour drive, accepting blow jobs and raw dogs and golden showers as reward—monoliths of frantic, first-time sex to confirm our completely successful relationship. And this frosting? Was it frosting! I wrote chapters for The Falconers on Falconer Avenue. The world made perfect sense.

Of course, none of it “came to pass,” as Pynchon’s narrator in Against the Day is fond of saying. The novel fell apart. The boyfriend and I broke up. Still, when I revisit Wright letters and Wright biographies, I’m hounded by a mysterious and entirely inappropriate erection—that is, a kind of Pynchonian kink.

AFTER PICKING A FIGHT IN A BAR

People were gentler with me, I think, with my black eye. It was the week between Christmas and the New Year, I had obviously been in a row, not elbowed, not tripped, and so in addition to looking smaller and darker and sadder than is usual for the holidays, I also looked more crazed and vicious. Why this would compel others to treat me gently does not signify a particular gentleness, or generosity, on their parts—but rather, I detected, a means to protect themselves. If I was not able to defend myself then surely they could defend against me. Kindness is a soft weapon. I rarely wielded it but was nonetheless always disarmed by it. Gentleness did not make me more gentle. I spent the week puzzled by unnecessary soft gestures and soothing voices. I spent the week reminding myself my special treatment was because I looked beat down, not because I was special. Besides, what could that mean? “Special.” Chosen, preferred, anointed, deserving, etc. I sometimes thought about what the world owed me, that week. I landed on “abstention.” Not mercy or forgiveness but rather a quiet space to be alone in earnest, all obligations off, responsibilities tamped down, remission. I had the week off work, which, my brother let me know, was a kind of mercy, because it’s always professionally suspect to arrive at work with a shiner. Colleagues ask questions and bosses harbor suspicions. I was fortunate in that my face could recuperate without scrutiny.

8 notes

·

View notes