#yegheritage

Photo

We picked up a nice load of old wood sash windows in frames along with some very cool wood spindles and doors from a heritage house here in the city that’s being renovated. • If you have a heritage house and are doing and addition or maybe framing in the porch and want to keep things looking original then these would work perfectly. • Stop in, have a look and save some $$$ on your next project! 🙂 • Architectural Clearinghouse @ 11518-119st Monday to Friday 9-6 Saturdays 9-5 • • • • • • • • • • #yegdiy #yegreno #yegrenos #yegrenovations #yegrenovation #yegrenovator #yegbuild #yegbuilds #yegbuilder #yegbuilders #yegbusiness #edmontonbusiness #yeglocal #yeglocalbusiness #yeglocalshop #yegger #yeggers #yeg #edmonton #stalbert #sprucegrove #stonyplain #sherwoodpark #sustainableyeg #wastefreeyeg #yegheritage #alberta #yeginfill #yeginfills https://www.instagram.com/p/CjlFFkJL074/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#yegdiy#yegreno#yegrenos#yegrenovations#yegrenovation#yegrenovator#yegbuild#yegbuilds#yegbuilder#yegbuilders#yegbusiness#edmontonbusiness#yeglocal#yeglocalbusiness#yeglocalshop#yegger#yeggers#yeg#edmonton#stalbert#sprucegrove#stonyplain#sherwoodpark#sustainableyeg#wastefreeyeg#yegheritage#alberta#yeginfill#yeginfills

0 notes

Text

Yorath House Artist Residency Blog Post 5: Treaties and Settlement History

By Adriana A. Davies

Yorath House Artist-in-Residence

A sketch of the buildings at Fort Edmonton done by Dr. A. Whiteside, 1880, City of Edmonton Archives EA-10-1178.

Sitting in Yorath House next to the North Saskatchewan River doing online research on homestead records, and also reading newspaper accounts from the end of the nineteenth and early part of the twentieth centuries, I come face-to-face with racism. The accounts are written from the settler perspective. The City of Edmonton Archives on its website has posted the following statement:

The City of Edmonton Archives (CoE A) has developed this statement regarding the language used in archival descriptions to meaningfully integrate equity and reconciliation work into the City’s archival practice. The changes reflect the staff’s on-going efforts to acknowledge known instances of discrimination that appear in archival records.

Archivists have been working on identifying and contextualizing problematic content, language and imagery found in our collections since 2017. This was partly in response to the Truth and Reconciliation (TRC) Commission’s Calls to Action, specifically those aimed at cultural and heritage institutions. Further work is on-going in alignment with the City of Edmonton’s commitments to inclusion and respect for diversity and the work of various groups in the City and, specifically, of the Anti-Racism Committee of City Council, as well as the Association of Canadian Archivists’ Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct.

While the statement deals with the language in historic documents, there is a larger issue. The Government of Canada was intent on colonizing traditional Indigenous lands. The territories that became Canada initially attracted the attention of the British and French because of the bounty of fur-bearing animals. The fur of beavers, in particular, was used to create felt for hat making. Fur trading companies were the first major commercial enterprises (Hudson’s Bay Company and North-West Company) and were followed by others to harvest other natural resources including fish and stands of timber.

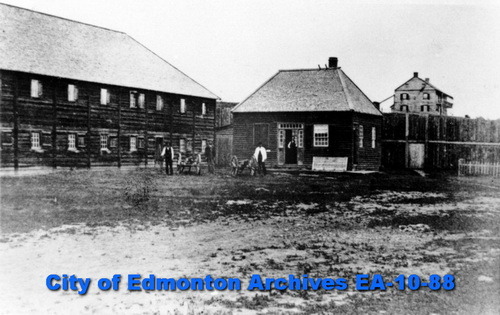

The interior of Fort Edmonton within the palisades showing the warehouse, Chief Factor’s House and Clerks’ quarters, 1894, City of Edmonton Archives EA-10-88.

With the signing of Treaty No. 6 on August 23, 1876 at Fort Carlton and on September 9, at Fort Pitt, the federal government was ready to unite the country “from sea to shining sea” through the building of a railway. The territory in question covered most of the central portions of what became, in 1905, the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta. The signatories were representatives of the Canadian Crown and the Cree, Chipewyan and Stoney nations.

Front and back of large medal presented to the Chiefs and councillors who signed treaties 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. It shows a relief portrait of Queen Victoria and the representative of the Crown shaking hands with one of the Chiefs. Libraries and Archives Canada, Accession number: 1971-205 NPC.

Treaty 6 was mid-way in the 11 numbered treaties; Treaties 6, 7 and 8 cover most of Alberta. At the Fort Carlton meeting, on the part of First Nations, Chief Mistawasis (Big Child) and Chief Ahtahkakoop (Star Blanket) represented the Carlton Cree. On the part of the Crown, principal negotiators were Alexander Morris, Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Territories; James McKay, a Metis fur trader, and Minister of Agriculture for Manitoba; and W. J. Christie, Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

Chiefs at Fort Pitt trading with Hudson’s Bay Company representatives, autumn 1884, unknown photographer. L-R: Four Sky Thunder; Sky Bird (or King Bird), the third son of Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear); Moose (seated); Naposis; Mistahimaskwa; Angus McKay; Mr. Dufresne; Louis Goulet; Stanley Simpson; Constable G. W. Rowley (seated); Alex McDonald (in back); Corporal R. B. Sleigh; Mr. Edmund; and Henry Dufresne. There is a difference of opinion as to the names of the two corporals: some sources claim it is Corporal Sleigh and Billy Anderson, while others claim it is Patsy Carroll and H. A. Edmonds. Library and Archives Canada, Ernest Brown Fonds/e011303100-020_s1.

When Treaty negotiations began at Fort Pitt, on September 5, Cree Chief Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear) was away and therefore did not participate. Chief Weekaskookwasayin (Sweet Grass) led the discussions and appeared to accept that the terms of the Treaty would be beneficial; he was likely influenced by Chiefs Mistawasis and Ahtahkakoop. When Chief Mistahimaskwa returned, he was surprised that the other chiefs had not waited for him to return before signing. He had some important news to share: he had spoken to some of the signatories of previous Treaties and they had told him that they had been disappointed with the outcomes. Historian Hugh Dempsey has written that, if the Chief had been there, Treaty 6 may not have been signed. The entry in The Canadian Encyclopedia notes:

When Mistahimaskwa returned to Fort Pitt, he brought discouraging news with him from the Indigenous peoples on the prairies who had already signed Treaties 1 to 5: the treaties had not amounted to everything that the people had hoped. However, he was too late; the treaty had already been signed. Mistahimaskwa was frustrated and surprised that the other chiefs had not waited for him to return before concluding the negotiations. According to the notes of the commission’s secretary, M.G. Dickieson, Mistahimaskwa referred to the treaty as a dreaded “rope to be about my neck.” Mistahimaskwa was not referring to a literal hanging (which is what some government officials had believed), but to the loss of his and his people’s freedom, and Indigenous loss of control over land and resources. Dempsey argues that if Mistahimaskwa had been present at the negotiations, the treaty commissioners would have likely had a more difficult time acquiring Indigenous approval of Treaty 6. Mistahimaskwa was not the only chief who initially refused to sign the treaty. Chief Minahikosis (Little Pine) and other Cree leaders of the Saskatchewan District were also opposed to the terms, arguing that the treaty provided little protections for their people. Fearing starvation and unrest, many of the initially hesitant chiefs signed adhesions to the treaty in the years to come, including Minahikosis (who signed in July 1879) and Mistahimaskwa (who signed on 8 December 1882 at Fort Walsh).1

The “adhesions” involved the adding of signatories from other areas including Edmonton in 1877, Blackfoot Crossing in 1877, Sounding Lake in 1879, and Rocky Mountain House in 1944 and 1950. Treaty 6 encompasses 17 First Nations in central Alberta including the Dene Suliné, Cree, Nakota Sioux and Saulteaux peoples. The Edmonton adhesion was signed on August 21, 1877 on the land that would become the site of the Alberta Legislature. The site was a sacred gathering place for the Indigenous People of Alberta.

While the Treaties outline the rights, benefits and obligations to each other of the signing parties, there is no doubt that they were intended to enable a “land grab”: the Government of Canada wanted to open up the land for settlement. Indigenous People were to be confined to “reserves” and the remaining lands were to be made available. In 1869, Canada had purchased extensive parts of Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company but the Company, because of its historic role in the fur trade, retained extensive tracts of land. When the federal government gave the Canadian Pacific Railway a monopoly to build the railway through the prairies they were also given extensive lands not only for laying of tracks and building of stations but also for establishing town sites and farms.

As sovereign peoples, why would Indigenous People in what became Alberta and Saskatchewan want to sign Treaties? They came to the negotiations in good faith expecting that the Government of Canada would protect their lands from outsiders including white settlers, surveyors and the Métis. By the mid-nineteenth century, buffalo herds had declined, as had deer and other big game, and they faced starvation; in addition, various smallpox epidemics were decimating their population and that is why they negotiated the “medicine chest” provision in Treaty 6; it was literally to be housed with the Indian agent. In addition, the Government promised to assist the signatories in farming initiatives by providing various types of equipment.

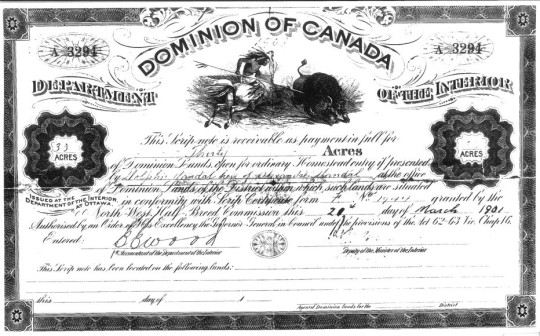

With respect to the Metis or “mixed blood” peoples who were the result of marriages between fur traders and Indigenous women, the Government of Canada devised Métis scrip, which was a one-time payment whether in money or land that “extinguished” the individual’s land rights. Whether the recipients understood this is open to question. The certificate or warrant was issued by the Department of the Interior and printed by the Canadian Bank Note Company. Money scrip came in $20, $80, $160 and $240 increments. Land scrip came in allotments of 80, 160 and 240 acre (32, 65 and 97 hectare) increments. This allowed the Canadian government to acquire Métis rights to the land. As Robert Houle writes:

To the detriment of the Métis, who at the time did not fully comprehend the foreign system, traders like McDougall and Secord began to venture away from mercantilism. Through continued exploitation of the Crown system, McDougall and Secord were able to become “Edmonton’s First Millionaire Teachers”. The Scrip system allowed those with resources to purchase a certificate for face value or perhaps a marginal increase, then redeem the certificate on behalf, sometimes through fraud, of the original holder and re-sell for profit. Once a sale was undertaken, unbeknownst to Métis, their claims and rights would be extinguished in the eyes of the Crown.2

Métis Scrip for 30 acres issued March 20, 1901. Image Courtesy of the City of Edmonton archives MS-46 File 38.

In order for the land to be settled, it needed to be surveyed. This work had begun in 1871 after Manitoba became a province, and the North-West Territories was established as a result of the purchase of Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company. The Dominion Land Survey covered about 800,000 square kilometres and began with Manitoba and then continued West. In 1869, the first meridian was chosen at 97°27′28.4″ west longitude. The survey excluded First Nations’ reserves and federal parks. The Hudson’s Bay received Section 8 and most of Section 26.

The surveys were done in three stages: 1871-1879: southern Manitoba and a little of Saskatchewan; 1880: small areas of Saskatchewan; and 1881: the largest survey that includes what became Alberta. There was a sense of urgency about finishing the survey because the Government of Canada feared US encroachment into Canada. Over 27 million quarter sections were surveyed by 1883; maps and plans were given to the provinces. Townships were composed of 36 sections, and sections comprised 4 quarter sections or 16 subdivisions.

After Hudson’s Bay Company railway right of ways and school sections were carved out, the remainder became available for homesteads. The federal and provincial governments and municipalities advertised land availability for settlement. A homesteader had to pay a $10 fee to register a quarter-section and, within a term of three years, had to cultivate 30 acres (12 hectares) and build a house to gain title to the land. The bulk of prairie settlement occurred in the period 1885 to 1914.

With respect to the surveying of the land at Fort Edmonton, W. F. King did an initial survey for the Government of Canada in 1878. The formal survey was done in 1882 and adhered to the river lot pattern that the largely Métis population had established. This was based on the system used in Quebec. Because many of the Métis at Fort Edmonton and St. Albert had begun to settle the land and their small farms and landholdings adhered to the river lot system, this was grandfathered in.

The Hudson’s Bay Company had an extensive tract of land to the West of the downtown centred on Jasper Avenue (the Hudson’s Bay Reserve). The survey established 44 lots covering both sides of the North Saskatchewan River. These were East of the HBC reserve lands. By and large, these were Métis owned with the remainder purchased from the Company by current and former employees. The lots on the northern side of the River were even-numbered and the lots on the south side were odd-numbered. Among the former HBC employees were Malcom Groat, Colin Fraser, John Sinclair, Donald McLeod, James and William Rowland, Kenneth Macdonald, James Kirkness, John Fraser and James and George Gullion. Métis homesteaders included Joseph McDonald (River Lot 11), Laurent Garneau (River Lot 7), some of whom had also worked for the Company.3 These lots were by and large farmland until the communities of Edmonton and Strathcona began to expand quickly becoming towns and cities in the period from 1890 to 1914 when a worldwide economic recession and the First World War put an end to development.

Connor Thompson in “Edmonton’s River Lots: A Layer in Our History,” writes:

As the area’s fur trade was winding down, farming began to take on a greater importance in the lives of the people around Fort Edmonton. Many began staking claims to land in the Fort’s immediate vicinity, farming in a river lot fashion. A staple of Métis culture, this style of farming allowed for access to the river, wooded areas, cultivated land, and provided space for hay lands as well. While a rough (and unapproved) survey was undertaken by government surveyor W. F. King 1878, a more thorough government-approved survey in 1882 formalized the division of the land in terms of a river lot pattern, which is what the predominantly Métis population in the area at the time desired. The survey created 44 large lots across the banks of the North Saskatchewan, most of which stretched east of the Hudson’s Bay Company reserve lands. In many ways, the early history of these river lots is a history of the Métis and their kinship networks – marriage between the area’s families was common, as were friendship and support systems.

Other south side families faced struggles relating to their Indigenous identities, especially with the pressures of Métis scrip and the 1885 rebellion – Métis scrip was a one-time payment of either money or land that, in the eyes of the Canadian government, extinguished the person’s Indigenous land rights. Scrip was notorious for its convoluted process and unethical nature. Many families on these south-side river lot farms, including the family of William Meaver on River Lot 15 (bounded by present-day 99th St. to 101 St.), Charles Gauthier and his son on River Lot 17 south (99th St. and Mill Creek Ravine), George Donald and Betsy Brass of River Lot 21 (91st to 95th St., in the present-day Bonnie Doon neighborhood), took scrip. Some of the families that were members of the Papaschase band either took scrip (as Brass herself, who was a woman of mixed Cree/Saulteaux ancestry did), or joined the Enoch band, as William Ward’s family (of River Lot 13) did. As settlement increased, many Métis families of this period would leave to places such as St. Paul des Métis, St. Albert, Tofield, and Cooking Lake.

As the largely British towns of Edmonton and Strathcona grew, the Indigenous origins of the land were erased and the rights of Indigenous Peoples violated.

Edmonton Settlement showing the river lots, ca. 1882. City of Edmonton Archives EAM-85.

Interpreting History

In August 1951, my Mother Estera, older sister Rosa and my brother Giuseppe and I joined our Father, Raffaele Albi in Edmonton. He had left Italy in 1949 and made his way to Edmonton and begun work for an Italian-owned company, New West Construction. The company was helping to finish the Imperial Oil Refinery in Strathcona. In 1953, my parents purchased an old house on 127 Street and 109A Avenue in the Westmount area. That September, we went to school at St. Andrew’s Elementary School across from the Charles Camsell Hospital. That is when I encountered racism personally: as a dark and thin southern-Italian kid, I became the target of “half-breed” jokes. I knew who these people were because daily I watched the dark-skinned children looking at me through the chain-link fence that surrounded the Hospital. They looked sad and I felt that they were jealous watching us play our care-free games in the school yard. There were some Métis children in my school and I quickly made friends with members of the L’Hirondelle, Mercier and Majeau families not realizing that for some of my school mates this was not done.

It came as a surprise to me that Italians were considered a “visible minority” and therefore the butt of jokes, many about the Mafia, DPs, Wops or other pejorative terms. I was thus sensitized to “being different.” When I was in junior high, I decided that I wanted to be a journalist and, in 1962, became a student at the University of Alberta with an English major and French minor. I volunteered with the student newspaper, The Gateway, and the summer of 1964 was a student intern at The Edmonton Journal.

Two traumatic experiences occurred that summer that helped to shape my thinking and influenced my life and career. A friendly journalist told me that there was a bet on at the Greenbriar Lounge, where the largely male staff went to drink, as to who would get me into bed (nobody did!). The other occurred when on weekend duty I was assigned to cover a story on a northern reserve. Weekend duty was assigned to younger staff and the carrot was that you got to do a photo essay for the Sunday newspaper. A young photographer and I drove up to the reserve and I remember arriving in a tiny, tiny community (it wasn’t large enough to be described as a town) and going to what looked like the community hall. Dave and I entered an extremely smoky room where all the men were talking animatedly. When we introduced ourselves, they were extremely kind and I began the interviews. I discovered that they were discussing Treaty rights and that the Government of Canada was not honouring these. I was captivated. On our return to the Journal offices late that evening (Saturday), I wrote the article telling their story. I was delighted with the two-page spread that included David’s photographs of the Chiefs and Elders. The following Thursday at the weekly Editorial meeting, Editor Andrew Snaddon tore strips off me for having “lost my objectivity” and only told the “Indian” side of the story. From that day forward, I knew that I wanted to continue to tell those stories.

The first opportunity came in January 1987 when I started work as the executive director of the Alberta Museums Association. I took a call in the first week from someone wanting to know what “ICOM Resolution 11” was. I didn’t know so I called the Canadian Museums Association and learned that the International Council of Museums at its General Assembly in 1986 in Buenos Aires, Argentina had passed a resolution that was to guide museums in dealing with living Indigenous communities. It stated:

Resolution No. 11: Participation of Ethnic Groups in Museum Activities

Whereas there are increasing concerns on the part of ethnic groups regarding the ways in which they and their cultures are portrayed in museum exhibitions and programmes, The 15th General Assembly of ICOM, meeting in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 4 November 1986, Recommends that: 1. Museums which are engaged in activities relating to living ethnic groups, should, whenever possible, consult with the appropriate members of those groups, and 2. Such museums should avoid using ethnic materials in any way which might be detrimental to the group that produced them; their usage should be in keeping with the spirit of the ICOM Code of Professional Ethics, with particular reference to paragraphs 2.8 and 6.7.

The resolution enshrined consultation on all Indigenous exhibits and programs that has become a practice with Canadian museums. When I called back and gave the mystery caller this information, I asked who they represented and learned that it was the Lubicon Cree. This northern Alberta First Nation had been left out of Treaty 8 negotiations. They had filed a claim with the federal government as early as 1933, for their own reserve but nothing had been done to resolve the matter. Pressures on their traditional way of life resulting from the number of oil companies drilling on the contested territory had accelerated their need for a settlement. Under a new, young Chief, Bernard Ominayak, the cause received renewed impetus and he sought the help of professionals.

American human rights activist Fred Lennarson became his chief advisor in 1979. His consulting company, Mirmir Corporation, had already done work for the Indian Association of Alberta (under Harold Cardinal). Ominayak and Lennarson aimed to get a $1 billion settlement from the federal government and, to do this, organized an aggressive letter writing and media campaign. By 1983, they were mailing information about the land claim dispute to over 600 organizations and individuals around the world and had been successful in obtaining the support of the World Council of Churches and the European Parliament. Knowing that they would need the support of Indigenous organizations, they had extensive meetings and, among the first to come on board were the Assembly of First Nations, the Indian Association of Alberta, the Métis Association of Alberta and the Grand Council of Quebec Cree.

Subsequently, when the Glenbow Museum launched its exhibit, curated by Julia Harrison, titled “The Spirits Sings,” as part of the Calgary Winter Olympics in 1988, there were protestors there indicating the museum had violated ICOM Resolution 11 and also attacking the display of “False Face” sacred masks that were on display. In fact, Harrison had had an Indigenous advisory committee and the masks had previously been on display in Ontario museums as well as in the Canadian Embassy in London, England, without objections. This event galvanized museum personnel to undertake some serious reflection on the way in which they represented Indigenous history and artifacts.

The Canadian Museums Association with the Assembly of First Nations undertook the Task Force on Museums and First Peoples and I was delighted to take part in this work which was led on the museum side by Morris Flewwelling, the CMA President at the time. With the support of the Board of the Alberta Museums Association, we created three symposia held in 1988, 1989 and 1990 to address the relationship between museums and First Peoples, repatriation of ceremonial and sacred objects, and the topic “Re-inventing the Museum in Native Terms.” For this last, I invited representatives from the Ak-Chin Eco-Museum in Arizona. The community, which was established in 1912 as a reservation, was plagued by poverty and scarcity of resources until it declared itself an “ecomuseum” and focused on preservation of its language and culture to promote economic development.

As a result of information gathered through our symposia and meetings with representatives from various Indigenous communities (both within and outside of Alberta), I was delighted to provide advice to a number of Indigenous museum projects. I could not have done this work without the help of some prominent individuals, who championed Indigenous history and were chiefs, elders and ceremonialists. The most important were Russell Wright and wife Julia; Leo Pretty Young Man Senior and wife Alma; and Reg Crowshoe and wife Rose. They participated willingly in the Alberta Museums Association Indigenous symposia and in other planning and advisory work.

Russell struggled to maintain a museum in the old Residential School at Blackfoot Crossing on the Bow River East of Calgary. In the 1970s, he had helped to develop a Blackfoot studies program for the Old Sun College on the reserve. He was troubled by the high rate of student suicides on the reserve and firmly believed that it was only through the renewal of the Blackfoot culture and language that this trend could be halted. I did my best in advising him as to how to go about fundraising for a new museum, which had been his dream since the 1977 centenary celebrations of the signing of Treaty 7 (Prince Charles attended the ceremonies). With Leo Pretty Young Man Senior and wife Alma as well as other Elders and their wives, he envisioned an appropriate building that would house cultural artifacts and function as an education centre.

The Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park is a legacy to their vision. In 1989, six square kilometres of land were set aside but funding would not become available until 2003 to initiate construction. Neither Russell nor Leo lived to see the museum, which was completed in 2007. The iconic teepee-like structure was designed by architect Ron Goodfellow. The Buffalo Nations group, headed by Leo, took over the old Luxton Museum in Banff and I was delighted to attend planning meetings to assist them to obtain grants to develop new exhibits, care for collections and undertake necessary restoration work to the building. The Buffalo Nations Luxton Museum became a popular attraction in Banff.

The vista from the rear windows of the Blackfoot Crossing Interpretive Centre, which is a National Historic Site of Canada located near Cluny, Alberta. The area in southern Alberta is significant as both a geographic and cultural centre of Blackfoot territory and includes the grassy flood plain of the Bow River Valley. It was the location where Treaty No. 7 was signed in 1877 by representatives of the the Siksika (Blackfoot), Pekuni (Peigan), Kainai (Blood), Nakoda (Stoney) and Tsuu T'ina (Sarcee) First Nations. They surrendered their rights to 50,000 square miles of territory. Numerous archaeological resources and historical features are located there including the grave of Chief Isapo-Muxika (Crowfoot). Photographer: Adriana A. Davies.

Another of my Indigenous mentors was Reg Crowshoe, a former chief of the Piikani Blackfoot First Nation, who had worked as an RCMP officer. He assisted the Historic Sites Service on various projects and generously shared his traditional knowledge with students at the universities of Lethbridge and Calgary. He founded the Old Man River Cultural Society and followed in the footsteps of his father, Joe Crow Shoe Senior. Joe was an Elder and Bundle Keeper and ran Sun Dances; he renewed the Brave Dog and Chickadee Societies. Father and son collaborated with Historic Sites Service, Government of Alberta, and were instrumental in the building of Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump Interpretive Centre near Fort Macleod, which showcases and interprets Blackfoot culture. It opened in 1987 and is run by Alberta Culture. It is a Canadian national historic site and UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Gerald Conaty, Julia Harrison’s successor at Glenbow as Curator of Ethnology, was an invaluable resource and took me on a number of field trips to Treaty Seven areas to meet with Elders and ceremonialists. Beginning in 1990, he helped the Glenbow to develop and implement repatriation policies with respect to sacred objects. The initial work was done by Hugh Dempsey, long-time Glenbow curator and sometime Acting Director, who had extensive relationships in the Indigenous community going back to his involvement with the Indian Association of Alberta. He married Pauline Gladstone, the daughter of James Gladstone, the first status Indian appointed to the Canadian Senate. In mid-1990, Dempsey with Board approval loaned a medicine bundle to Dan Weasel Moccasin for a ceremony thereby setting a precedent. The bundle was returned.

Towards the end of my tenure as Executive Director of the Alberta Museums Association around 1998-1999, I was involved in an interesting project titled “Lost Identities” put together by Historic Sites Service Museums Advisor Eric Waterton; Provincial Archives of Alberta Archivist, Marlena Wyman; Pat Myers, historian with the Provincial Museum of Alberta; and Shirley Bruised Head, the Education Officer at the Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump Interpretive Centre. We wanted to develop a photographic exhibit for the Centre and Marlena scanned their collection for a cross-section of photos representing Treaty 7 people. When the committee reviewed them, we noticed that archival photographs frequently had the label “unknown Indian.” We decided to focus on those photographs for the exhibit and selected about 30 photographs that were enlarged and framed. They were hung in an exhibit room at the Interpretive Centre and next to each was a copy of the photograph with blank outlines of the people. Visitors to the exhibit were encouraged to identify anyone they knew.

I remember well the exhibit launch organized by Shirley. There was a feast for the Elders and after the blessings were finished, the exhibit was introduced and the participants began to walk around looking at each photograph carefully. For some time, there was absolute silence in the room followed by a kind of buzzing noise as they began to talk to each other and point at people they knew.

Shirley was an extraordinary woman (Sacred Hill Woman "Naatoyiitomakii"), who died too soon in 2012. She was a member of the Piikani Nation and she and her twin sister Barbara were born on the reserve on February 19, 1951 to Irene and Joe Scott. Her parents ranched. After their early death, the children were separated and she grew up in her Uncle’s home in Siksika and then moved to Edmonton to attend St. Joseph’s High School. She married Norbert Bruised Head and supported his rodeo career and worked for Native Counseling Services in Lethbridge. She obtained a BA degree from the University of Lethbridge and, later, a Master’s in Education. She was a ceremonialist and was a pipe owner; she assisted in the beaver bundle ceremony.

A committee of former presidents of the Alberta Museums Association met for several years to discuss how to make the Association more financially independent and how to promote museums more effectively. The result of this was the creation of the Heritage Community Foundation in summer 1999 with the mandate “to link people with heritage through discovery and learning.” At that time, I was a member of the Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN) advisory committee and involved in a “Museums and the Web” study. I quickly became convinced that the World Wide Web offered enormous opportunities for promoting heritage. The Foundation obtained funding to create our first website – a kind of overview of Alberta’s heritage and museums – and this gave us our direction.

I pitched to the Board that the primary focus of the Foundation should become the development of web content drawing on museum and archival collections and, furthermore, that we should create the “Alberta Online Encyclopedia.” They wholeheartedly endorsed this and www.albertasource.ca was born. Luck and, I guess, timing was on our side. In March 2001, CHIN launched the Virtual Museum of Canada, which had a grants program, and I knew which project to bring forward. The Spirit of the Peace Museum Network had developed a travelling exhibit titled “The Making of Treaty 8 in Canada’s Northwest.” It was rich in artifacts, documents and records. I approached Fran Moore, the Chair of the network, and asked whether they would partner with us and the answer back was an unequivocal, “Yes!” It was all systems go. I developed the grant application, which was jointly submitted, and we obtained funding to hire some project staff and a firm of web developers. In the end, content and images for the bilingual website were contributed by not only the Museums of the Peace but also, the Glenbow, Provincial Museum of Alberta, Treaty 8 First Nations and the Lobstick Journal. I remember going up North to test the site with Elders and seeing the excitement on their faces when they began to identify relatives in the archival photos. The website was launched in 2002 and CHIN was thrilled with it.

In 2004, we designed a project to celebrate Alberta’s centenary: expansion of the websites in order to cover Alberta’s social, natural, cultural, scientific and technological heritage. Albertasource.ca, the Alberta Online Encyclopedia, received a $1 million Centennial Legacy grant. On September 29, 2005, the Foundation launched the Encyclopedia – the Province’s intellectual legacy project – at the Edmonton Space and Science Centre to a supportive crowd including children from neighbourhood schools.

After development of the Treaty 8 website, we moved all technical development in-house because we found that we could better control quality as well as guaranteeing that websites were completed on time. This was crucial because in some instances the majority of funding was received on project completion. Of our first four interns, two stayed on with us for a number of years and became permanent staff. Dulcie Meatheringham, a young Métis woman from Northern Alberta, became our first webmaster. Over the 10-year life of the Foundation, we had over 450 interns, most for three-month internships.

There are certain groupings of websites that the Trustees and I take particular pride in; among them are the over 30 websites that are either wholly or partly devoted to Indigenous content. All involved partnerships with Treaty organizations and the Métis Nation of Alberta. These include sites on individual treaties as well as Alberta’s Metis Heritage, People of the Boreal Forest and Elders’ Voices. The last included content from the “Ten Grandmothers Project” undertaken by Linda Many Guns of the Nii Touii Knowledge and Learning Centre; the Centenarians, a nine-minute video production celebrating Indigenous women resulting from a partnership between Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, the Institute for the Advancement of Aboriginal Women and EnCana Energy. We also undertook some oral histories of Métis veterans. Thirteen Edukits draw on the content of the various websites and provide teacher and student resources directly related to the K-12 curriculum. They are: Alex Decoteau; Origin and Settlement; First Nations Contributions; Culture and Meaning; Language and Culture; Spirituality and Creation; Health and Wellness; Leadership; Physical Education, Sports and Recreation; Math: Elementary; Science; and Carving Faces: People of the Boreal Forest.

I am proud of the fact that we created three Indigenous internship programs in partnership with the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology that trained young people in web design. We obtained some funding from Western Economic Diversification in support of the project. We had not only interns who specialized in web design but also graduates in history who wrote site content. They worked on both Indigenous and non-Indigenous websites. Some have made careers in this area. On June 30, 2009, the Heritage Community Foundation gifted the Alberta Online Encyclopedia to the University of Alberta so that it could make available the websites in perpetuity.

What people in the museum and heritage field accomplished in partnership with Indigenous Peoples and institutions from 1987 to the present is only a beginning. As we move into the era of the “decolonizing of museums,” a whole new generation of Shirley Bruised Heads, Linda Many Guns and others are needed. It’s good to see these new voices, talents and abilities emerging and tackling recommendations from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. I was privileged to be able to attend the last day of the Commission hearings held in Edmonton from March 27-30, 2014 at the Shaw Conference Centre. I eagerly awaited the release of the report in June 2015 and have tracked how heritage and arts organizations have begun to implement its recommendations.

The last physical event that I attended before Covid was the Edmonton Heritage Council’s Symposium titled “Reconciliation and Resurgence: Heritage Practice in Post-TRC Edmonton.” Their website notes:

On March 3 and 4, 2020, 150 people came together at La Cité Francophone to discuss Reconciliation and Resurgence in post Truth and Reconciliation Commission Edmonton. Members of the Indigenous community, Edmonton’s heritage sector, academics, not-for-profit workers, students, public sector workers, and members of the public, came together to learn how each of us can contribute to reconciliation work in the heritage community. Those in attendance were encouraged to consider and examine the ways in which Indigenous peoples and heritage have been and continue to be excluded or marginalized within heritage institutions and narratives. We asked attendees to think critically about their own roles in this pattern of erasure, and to consider a way forward where Indigenous voices are lifted up, where Indigenous heritage is told by Indigenous people, and how historical erasure and marginalization has contributed to the current realities of systemic racism.

The Edmonton Heritage Council was advised by Elders and community members from First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities throughout the planning process. Each day of the symposium began in ceremony with smudging and a prayer.4

From the 15 - 18 of March, 2021, I attended a virtual symposium organized by the International Committee for Museology of the International Council of Museums, which is part of UNESCO. I have been a member for over 30 years and served on the ICOM Canada Board. The conference was to take place in Montreal but Covid turned it to an online encounter. The topic was “Decolonizing Museology: Museums, Mixing and Myths of Origin.” The focus was as follows:

The purpose of the ICOFOM Annual Meeting is to create an international forum for a high level discussion on a museological topic. Usually, the topic is different each year, but sometimes it is analyzed over a three year period.

Approaches to museology vary widely around the world, for example, using museums to make statements about nationalism is given priority in some countries. In others, conservation and the exhibition of highly aestheticized, non-controversial artefacts, are regarded as the primary roles for museums. By contrast, in other nations, the development of “histories from below” or the salvaging of the histories of the lives of people who were regarded as having no value, is now a primary museological focus. The wide international variety of museologies means that the annual meeting has fundamental importance for the expression and recording of these differences.

I am looking forward to seeing the next era of history writing and interpretation.

The Dome

Standing on the Dome, Dawson City,

You can see the fingers of river stretching towards the Bering Strait.

Rotating through 360 degrees,

The various landscapes open up to you.

The place is magical –

Both in its natural and human elements.

The light, in this Land of the Midnight Sun,

Is like no other.

It brings out the artist in me.

I want to paint word pictures—

Of rocks, trees, sky and water,

A haze smudging the distant mountains into the cloud cover.

Time present and time past merge.

Geological time has shaped rock formations;

Glaciation normally softens these, but not in this valley;

And vegetation adds the finishing touches.

Up here, the town site is miniscule—

The works of man diminished by the works of nature.

The reverse of what is seen at the valley floor,

Where churned-up gravels dominate.

There, the striations of gold-dredging,

Form giant worm leavings—

The only industrial operation that almost looks natural—

The regularity and symmetry of gravel ridges resembling a moraine.

Dredge no. 4 now sits tethered.

Its work of creating new landforms ended.

Its appetite for muskeg stilled by economic forces,

The devaluing of the sovereign metal.

And what of those changed lives?

The preserved buildings are a memorial to them.

Window displays tell of events,

And objects are tangible evidence.

You can identify buildings and streets,

Forming the background of archival photos.

But, what you don’t get are the raw emotions—

The greed, flimflam, pain and loss.

When it all went bust,

Those gold gypsies walked away,

Leaving their possessions behind, like empty cocoons—

The residue of a transitory, disposable society.

We now want to put those lives on show,

In restored and recreated buildings,

For the entertainment of bus-tour travellers.

How can we do it and pay homage to their humanity?

In the window in the madam’s house,

I see photos—a woman in a fashionable, fifties swing coat with a dog,

Also a family portrait with an Oriental man and little boy.

Was it greed that brought this genteel Parisienne to the Yukon?

The priests and religious are also there.

Ministering to their flocks brought hardship and even death.

Did they feel it was worth it, in the end,

When facing their Maker?

The substantial buildings survive,

Set down for a future territorial capital,

Their neoclassical tin facades,

Bravely face river and forest.

Those gold hustlers must have had other qualities to counter the greed.

Some must have come to stay—

To put down roots,

And leave a legacy for their children.

What about the Native People—

Skookum Jim and Tagish Charlie?

Cast as bit players in this colonial saga,

Their impassive countenances don’t say much.

We need the Han Centre to place the Gold Follies in a larger context.

Indigenous time and values—

Centuries in the making—

Providing a silent commentary on white mayfly lives.

Did they know that it would be heritage tourism —

The “gold rush” of the early 20th century—

That would provide the window on their lives,

The measure of their success whether they struck it rich or not.

The aged prospector in the CBC documentary,

Repeats the eternal round of digging into the earth,

Like an Ancient Mariner marooned in mid-century,

A generation away from when the action left Dawson.

Museums have serious powers.

Unearthing the past has its responsibilities.

Each day, we make and break reputations—

Validate one person’s struggle, while ignoring another’s.

We have become dream merchants.

A rootless civilization finally coming to its senses,

Needing the bone, twigs, cloth and feathers

Of heritage “shamans” to reconstruct the world.

Is a code of professional ethics enough?

Or do we acknowledge our powers—

To create the symbols and icons for the next generation,

And turn job into vocation?

Whitehorse, June 3, 1998, Canadian Museums Association conference

________________________________________________

1 Michelle Filice, “Treaty 6,” The Canadian Encyclopedia Online, URL: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/treaty-6, retrieved January 15, 2022. See also Harold Cardinal and Walter Hildebrand, Treaty Elders of Saskatchewan: Our Dream is that Our Peoples Will One Day Be Clearly Recognized As Nations (2000).

2 Robert Henry Houle, “Richard Secord and Métis Scrip Speculation,” June 28, 2016, Edmonton Heritage Council, Edmonton City as Museum Project, URL: https://citymuseumedmonton.ca/2016/06/28/richard-henry-secord-and-metis-scrip-speculation/

3 See Connor Thompson, “Edmonton’s River Lots: A Layer in Our History,” September 9, 2020, URL: https://www.google.com/search?q=Edmonton%27s+River+Lots&ei=QBraYfTfC5mU0PEPuq-0oAk&ved=0ahUKEwj0_7fYo6P1AhUZCjQIHboXDZQQ4dUDCA4&oq=Edmonton%27s+River+Lots&gs_lcp=Cgdnd3Mtd2l6EAxKBAhBGABKBAhGGABQAFgAYABoAHAAeACAAQCIAQCSAQCYAQA&sclient=gws-wiz

4 See “Reconciliation and Resurgence: A Year Later,” Edmonton Heritage Council, URL: https://edmontonheritage.ca/blog/2021/03/04/reconciliation-and-resurgence-one-year-later/, retrieved January 18, 2022.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Spiritual . . Josaphat’s parish was originally established in 1904 as a beautiful initiative of brotherhood by the Ukrainian settlers and the Catholic hierarchy of Western Canada. They built a church 60 feet long and 40 feet wide. The exterior was built in 1904 at a cost of $2,500.00 CAD. . . https://stjosaphat.ab.ca/ourhistory/ . . #history #travelalberta #architecture #ukranian #yegheritage #yeg #yegarchitecture #djispark (at St. Josaphat's Ukrainian Catholic Cathedral) https://www.instagram.com/p/CA1OEGVAWlR/?igshid=18xp17jjivks1

0 notes

Photo

First a kid and now a doggo. Who will appear at June’s talk? . . Thanks to all our friends who are sharing their videos and photos of Friday’s event. It was a truly heartfelt experience, and we’re glad you got to be in The Ortona Armoury. . . #cmedm #cmpreserve #yegdogs #yegdt #ortonaarmoury #yeg #edmonton @creativemornings @yegheritage @edmontonexplorer | photo by our good friend and sharp eye @leroyschulz https://www.instagram.com/p/Bxn1X5-ATC_/?igshid=12lllxjrc43nc

1 note

·

View note

Quote

@KashFida: @yegheritage @WesternCycleYEG @shop124street Hello, I'm a reporter with Metro. Could you send me a dm? We would like to connect with you about this story.

http://twitter.com/KashFida

0 notes

Photo

“...those principles which guide and direct a President’s activities...should be to remember at all times that he must serve the cause of education...”

A former dean of Arts and Science and the U of A’s first vice-president, Walter Johns did not want to hold an installation ceremony. He was persuaded to do so by fellow faculty and members of the Board of Governors, and was installed as the U of A’s 6th president on April 4, 1959. The university saw a great deal of growth under John’s leadership, including expansion in Calgary in 1960. Six years later, the University of Alberta in Calgary would become the University of Calgary.

Photos courtesy of The Gateway and U of A Archives.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Yorath House Artist Residency Blog 1: Yorath House Sleeps in Snow

Words by Adriana A. Davies, Jan 5, 2022

Artwork by Marlena Wyman Jan 5-15, 2022

Artists-in-Residence at Yorath House

I drove from my mid-1950s bungalow in Parkview downhill, down Buena Vista Road to the flat area that is Laurier Park (named for Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier). The temperature this morning was -31 degrees Celsius and at 8:45 am there were not many cars on the road and those that were, like mine, were being driven carefully because of the thick snow that covered everything. Edmonton is truly a winter wonderland at this time of year though the admiration at its beauty, after a cold spell of nearly a month, is wearing thin. I passed the back entrance to the Valley Zoo on the way down and I tried to identify the 1950s Modern Style homes that had not been renovated and upgraded to more modern house clones, and I was pleased that there were still a few.

I made several turns on the flat land next to the north bank of the North Saskatchewan River that comprises part of Laurier Park and saw a sign for Buena Vista Park. I made a turn and saw the house. It is an angular, wooden-sided structure designed by the prominent architectural firm of Rule, Wynn and Rule and built for businessman and manager of Northwestern Utilities, Dennis Kestell Yorath and his wife Margaret Elizabeth (Bette) Wilkin in 1949. It was built on a 12-acre lot gifted to the couple by Bette’s father, William Wilkin who was one of the developers of the Laurier Heights subdivision.

The area at the River’s edge was once known as Miners’ Flats both because of the panning for gold that occurred along the North Saskatchewan River banks but also because of the number of coal mines that stretched along both sides of the River, the largest number in the stretch from the High Level Bridge to Cloverbar. The coal, unlike that buried deep in the Rockies, was found close to the surface of the banks of the sedimentary channel carved over the centuries by the River on its way East to its drainage in Hudson’s Bay. In the first decades of the twentieth century, there would have been miners’ shacks and some small homestead structures in the area now encompassing Laurier and Buena Vista parks.

All that was to change in the late 1940s as a result of the post-war boom experienced by Edmonton and other Alberta communities. Almost 60 percent of the residences in the Laurier Heights subdivision were built in the years 1946 to 1960; the rest, in the period 1961 to 1970; thus, the neighbourhood was not part of the inner “circles” of historic Edmonton neighbourhoods including not only the City Centre communities but also Westmount, Glenora, the Groat Estates and Capitol Hill. Laurier was built as a part of the movement westward that included Crestwood, Parkview and Valleyview neighbourhoods.

Architectural drawing of Yorath House by Rule, Wynn & Rule, 1949. Yorath family collection.

Yorath House, when it was built, made a bold statement both in its design and materials used. It did not hearken back to the past and the Craftsman Style houses made of brick and wood, and the brick public and retail buildings of past generations with Tindall stone trim. It was unlike the small stuccoed houses built for working class families. The new business elite wanted houses that were more futuristic in design and that affirmed that this was not their parent’s house. They seemed to say, “Look at us; we are part of the new world of prosperity based on resource wealth.” Edmonton looked to Toronto and New York for design influences. Rule, Wynn and Rule represented that larger world of architecture. Some iconic buildings that they designed include Glenora School, the Petroleum Club (demolished), U of A Rutherford Library, Eastglen Composite High School, AGT Building, Northwestern Utilities Building (now Milner Building), William Shaw House (St. George’s Crescent) and Varscona Theatre (demolished).

It was the fitting house for a young couple (he was born in 1905 and she in 1912) with an established British lineage on both sides of their family trees. Christopher James Yorath, Dennis’ father, left the UK with his young family in 1913 to become the Commissioner of the City of Saskatoon and then moved on to Edmonton in January 1921 to head the public works department of the City of Edmonton and, subsequently, became City Commissioner. He then moved to Calgary and was instrumental in the creation of gas and utility companies. William Lewis Wilkin, Betty’s father, left the UK in 1892 on the White Star liner Teutonic and initially worked for his maternal uncle, Henry (Harry) Wilson, a Whyte Avenue merchant, before striking out on his own in various business ventures including mercantile and property development. Dennis followed in his Father’s footsteps becoming involved in the natural gas industry in Calgary and, later, various utility companies that were local, national and international.

What drew me to the art residency was not only because I knew Laurier Park well having taken my children and grandchildren there for many outings over a period of 40 years but also because I had done the biography of Christopher Yorath for the Dictionary of Canadian Biography (to be published online in 2022) and, in the course of the research, had met several family members. I felt that the residency would allow me not only to further explore the history of the family but also to pursue another love, nature poetry. It would also allow me to work with Marlena Wyman, visual artist and archivist, who has begun the residency by documenting the house using her urban sketching skills.

Marlena Wyman & Adriana Davies in front of Yorath House, January 15, 2022. Photo by David Johnston.

On this unusually cold winter morning, I was wrapped up in a down coat with a hood and wearing silk long johns under my slacks, and my face was covered with a Covid mask (great in cold weather). I drove the car very close to the house and parked next to a City of Edmonton white truck. The young man blowing the snow off the walks around the house helped me to carry in my boxes and bags with research materials, books, laptop and various edibles since I’ll be working at the house all day (except for occasional forays to the City of Edmonton and Provincial Archives) until March 2nd.

I am now seated in the designated artists’ studio in one of the bedrooms on the second floor. It overlooks the small, cleared parking lot – not that you would know that it served that function since everything is covered in snow and the house is surrounded by beautiful fir trees of various types and hardy deciduous trees.

The empty house is “literally” asleep in the snow. As a historian and preservationist of the cultural and built heritage, buildings and landscapes speak to me and, in the depth of the silence of winter in this fascinating house that happened.

I need to clarify that they do not speak in ghostly voices but rather through the knowledge of the history of the City of Edmonton and the geology, geography and natural history of this place that I’ve acquired over the years.

I had much internal knowledge to draw on. I was the Science Editor of The Canadian Encyclopedia from 1980 to 1984; Executive Director of the Alberta Museums Association from 1987 to 1999; and ED of the Heritage Community Foundation from fall 1999 to June 30, 2009. In this last position, I was the creator and Editor-in-Chief of the Alberta Online Encyclopedia (www.albertasource.ca). Over a period of 10 years, we developed 84 multimedia websites dealing with all aspects of the human and natural history of Alberta placed in national and international contexts. When the Foundation shut down in 2009, the Trustees gifted the Encyclopedia to the University of Alberta in perpetuity for the people of Alberta.

In the first hour-and-a-half that I have spent sitting in front of the picture window in the studio contemplating nature, I’ve only seen one hardy individual walking a dog. The house embraces me and I feel sheltered and warm. But I know that it is not the house that Dennis and Bette built.

It is a City of Edmonton-designated historic property, purchased from Bette’s estate in 1992. When it was acquired, Edmonton’s heritage and architectural communities had great expectations that it would be restored and interpreted. From the mid-1980s, the City was committed to a park’s development strategy that aimed to remove all structures that were part of the River Valley Parks system. This left the house in a state of limbo and, after years of disuse, it was a sad structure. When I walked past it over the next ten or so years, I couldn’t resist the temptation to look in the windows. I thought at some point it may have been used for offices. I discovered in the 2012 historic assessment that it was used only for police-training exercises.

There were some protests about the City’s “benign” neglect of the property. An article in The Edmonton Journal of July 4, 2001 titled “Smith wants proposal on Yorath house,” noted that the Mayor had visited the “abandoned house.” The unnamed writer noted: “Smith says the house is still a valuable asset, particularly when one considers the land value of the 4.5 acre property. ‘You couldn't put a value on this property now,’ says Smith. ‘The house, structurally, is okay. It could be used for some purpose, with some alterations and repairs.’ Smith says it's too soon to say what the property might be used for. Past suggestions include a tea house or a community hall. But city officials say the house may be too far gone to repair, and may have to be replaced with something new.” Nothing happened during Smith’s term as mayor nor during Stephen Mandel’s term (2004-2013).

I became engaged in the house personally when I met Elizabeth Yorath-Welsh, when I was commissioned by the Dictionary of Canadian Biography to do the entry for her grandfather in 2013. She shared with me a number of archival resources relating to the families and the house (one is a small original drawing of the house done by the architects). At the time, she mentioned that she, her sister Gillian and cousins were saddened at the deterioration of the house.

Its designation in 2015 as a City of Edmonton Historic Resource, and conversion to a multi-use facility to host weddings and other family events, as well as meetings and planning sessions, required that the structure meet all contemporary building codes. The inside was rebuilt with new systems including an elevator and an extension was added. A total of $5.7 million was spent (up from an original estimate of about $2 million). While on the outside with its wooden cladding it is still mostly the house that Rule, Wynn and Rule designed, inside there are only a few features of the original left.

At the entrance, there is the wonderful wooden door with side lights reminiscent of an earlier era with its wrought-iron fittings. There is a red-brick entryway.

Inside the house, a wooden staircase with the original wooden steps and risers leads upstairs to the bedroom level. The bannisters are not metal but rather long wooden panels interwoven in a checkerboard pattern.

The massive fieldstone fireplace acts as a wall dividing the living/dining areas. It also extends through the exterior wall onto the back porch and forms an outdoor grill/stove and oven. It is an impressive place to have hung Christmas stockings. I imagine cocktail parties in the 1950s attended by the power brokers of Edmonton and Alberta.

The old galley kitchen looking into the living room is now set up for caterers and the only remnants of the original are four cupboard doors with fittings resembling those on wooden Hoosier cabinets or old ice box refrigerators. These are mounted on what would have been a kitchen wall facing into the living/dining room.

In other parts of the house, the remains of red brick floor-to-ceiling chimneys, and chimney breasts can be found.

This was the era of “picture windows” and Yorath House has them in abundance; they bring the outdoors in and also frame different landscapes surrounding the house. There are also windows set high in the staircase walls that allow light to flood in. Even in mid-winter on a dull day, the house is alive with light. While there is no historic furniture of the era, throughout the house are hung works of Alberta artists of the period including Marion Nicoll and John Snow drawn from the Alberta Foundation for the Arts Collection.

I am delighted that the house has been preserved and uses found for it but the purist in me wanted to walk into the perfectly-preserved period house that the City bought in 1992. In designation language, it was part of urban development associated with industry, in particular, the petroleum industry and the boom that occurred after the coming in of the Leduc #1 well in 1947 and the Redwater field shortly after.

Yorath House is part of that economic boom that made Alberta the powerhouse of the Canadian economy and spurred a massive wave of immigration to Alberta and Canada. Many of these immigrants from the UK and Eastern and Western Europe, were involved in resource industries and construction.

That era is at an end today, and the boom has become a mere echo. The Wilkin and Yorath families were part of booms and busts and left their mark on the province’s history.

In French museum studies, there is a term “objets phares” or “lighthouse objects.” This is used to describe artifacts and buildings that epitomize different points in history. I think that Yorath House is one of these iconic objects, looking forward and back in time.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yorath House Artist Residency Blog 2: The River’s Edge

Words by Adriana A. Davies, Jan 6-9, 2022

Artwork by Marlena Wyman Jan 17-21, 2022

Artists-in-Residence at Yorath House

Origin of Rivers

Great rivers begin as trickles

As the ice pack melts,

Over time.

In the Rocky Mountains,

Crowfoot Glacier,

After the passage of 100 years,

Becomes unrecognizable:

Only a couple of stumps.

The water roars down

Sluices and tunnels

Going underground

And pooling in expanses

Of milky aquamarine lakes—

Teeth-chatteringly cold.

From North to South

The rivers are named—

Peace and Athabasca,

North and South Saskatchewan,

Bow, Elbow and Milk.

They have carved deep channels

In the glacial sediment,

And given the land its final shape.

With exploration

And settlement,

We named things.

But they already had

Age-old names,

Some of which remain

In words exotic and sibilant

Like Saskatchewan,

Sipiwiyiniwak

And Amiskwaciy.

But this other land,

Where great herds of buffalo roamed,

And Indigenous People had dominion,

Is gone.

Remembered only through historic markers

Such as at Tail Creek—

Commemorating the last buffalo kill

Ending the nomadic life

Of Indigenous People

And Métis hunters.

They rode across

The Great Plains

Unrestricted by provincial

And state boundaries.

Still -24 Celsius temperatures but today the sun finally comes out and outlines the slopes and indentations in the snow like in works of the Group of Seven, who not only painted in Eastern Canada but also some of whom taught at the Banff School of Fine Arts and rendered Alberta landscapes. Today I contemplate the geology and physical geography of the surrounding land.

You cannot see the North Saskatchewan River to the south of the house, nor can you hear it in winter. The escarpment on the south bank is much higher than on the north bank (the Yorath House side) and, from the back of the house, the only view is of a cross-section of sedimentary rock and soil with plants and shrubs (albeit dead ones in winter) clinging to it. Behind the trees at the top of the ridge is Saskatchewan Drive and the Belgravia neighbourhood.

Prominent towards the top of the river bank are cement pillars that served as the retaining wall of the old Keillor Road that clung to the river bank and which was used by drivers for quick access to and from the University of Alberta via Fox Drive and the Whitemud Freeway. I have a guilty confession: I was one of those drivers who used the shortcut and on my morning and evening commutes enjoyed the “wildness” of the road as I rounded curves and bends, and also admired the horses in the Equine Centre. This was in the 1980s when I worked on Hurtig’s Canadian Encyclopedia project and, subsequently, for the Local Government Studies and Public Administration programs located in Ring House 2 on the U of A campus.

A landslide in 2002 took out the road and some of the trails and it was decided that the road would be closed permanently. These “ruins” became known unofficially as “The End of the World” and attracted many “daredevils” and courting couples. The City tried to deter this through signage indicating danger and also at times ticketing sightseers. Since it was already used as a viewing point, in 2015, after public consultations, the City decided to make this accidental attraction into the real thing. The design phase including assessment of environmental impacts took place from 2016 to 2018 and construction of a formal viewing platform with railings occurred in 2019.

Erosion

The play of wind and water

Has shaped these landforms.

Wide river channels

Snake across the flat plain,

The ravines they've scooped out,

Wooded with willow,

Poplar and birch.

At river level,

There is only stillness

Punctuated by bird song,

And it is easy to imagine

Canoes gliding along,

Stopping off at traditional meeting places,

Today's cities and towns.

The river has cut a steep channel.

And the banks form wooded escarpments.

Standing on the promontory of one,

I play queen of the castle,

The wind whipping past me,

Making me feel truly alive.

The site, now officially known as Keillor Point, provides stunning views of Laurier and Buena Vista Parks and the River. It is a fitting tribute to Dr. Frederick Keillor, the First World War medical officer, who purchased 61 acres in 1918 from pioneer John Walter, whose extensive businesses were destroyed as a result of the 1915 flood. Keillor built a rock and log cabin and farmed the land next to Fox Drive. By the late 1920s, this parcel of land was valued for its recreational potential, and a road was built to provide access to a ski club that had located nearby and the River valley. By the 1940s, Keillor had many offers from developers but his dream was that the City would purchase his farm, and keep development to a minimum and only for recreational uses. In the 1950s, he leased the land to some horsemen who created a stable and arena. In the 1970s, the land was purchased by the City and the equine use continued and today comprises the Whitemud Equine Centre. Dr. Keillor is commemorated through a plaque including a photo that is located at the bottom of the wooden stairs that take visitors down the slope to the River.i

Adriana A. Davies & Marlena Wyman outside Yorath House. Photo by David Johnston.

Unlike other parts of Edmonton’s extensive River Valley where you can easily reach the river bottom and walk along gravelled and sandy areas and skim rocks across the water, the Yorath lands do not have this type of frontage. The land sits above the River but not at a great height. I imagine that Bette Yorath warned the children about going down to the River not that they needed to. There was and is a large field that lends itself to picnics and games of baseball and other child’s play such as hide-and-seek. That is what makes it and Laurier and Buena Vista Parks such popular off-leash areas. In this extreme winter weather, one only sees hardy breeds of large dogs romping through the snow and dragging bundled-up owners behind them.

I cannot help but think of the River as not only a geographic feature but also as a conduit backwards and forwards through time. The word Sipiwiyiniwak means “People of the River” in Cree. Some 2,500 members of the Enoch Cree Nation live just west of the City of Edmonton ward that is named in their honour. Yorath House and the North Saskatchewan River lots on which it is located are found on Treaty 6 lands. The people of the region that became Edmonton are “people of the river” using its resources for nourishment. They have lived and gathered there since time immemorial, through the eras of the Treaties to the present.

The inter-relationship between the flowing river and the passage of time is a universal symbol. The North Saskatchewan River has carved a deep channel from its glacial origins in the Eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains as it meanders through the three prairie steps to Hudson’s Bay.

The historic Yorath House is an entry point into that journey in geological and human time.

Winter Promise

The air is heavy with the weight of unfallen snow.

The quiet almost disconcerting,

In this house in tamed woodland.

No faint barks of hardy dogs leaping over snowbanks

Dragging their owners behind them

In this off-leash area of the city.

Their tracks can be seen in yesterday’s snow.

Winter has this way of quietly erasing signs of human activity

Leaving the landscape still and unpopulated

As it once was.

How can I not reflect on time’s passage

When the Covid-19 clock

With its giant hands

Sweeps away human lives

Like the Great Reaper of Medieval fables.

While in my heart I struggle to hope

That we will get through this,

As we have in the past

With wars, famines, plagues and pandemics,

My mind is agitated.

I know that I must embrace the outer stillness of Nature

And cultivate a Zen-like state,

Or Christian resignation.

As I sit separated from the cold by thick panes of glass,

A pale light illuminates the winter landscape

And somehow I begin to breathe more easily.

___________________________

1 Information about Keillor, his farm and the equine centre established on it is provided in Tania Millen, “A Public Treasure Called Whitemud,” Horse Journals, April 27, 2018, URL: https://www.horsejournals.com/popular/history-heritage/horses-everyone-edmonton

___________________________

0 notes

Photo

#tbt to the beginning of #yegpublicart! The Migrants was installed in front of the old #yegcityhall in 1957. As part of the fountain. We now have more than 230 artworks by more than 300 artists in the collection! Visit edmontonpublicart.ca explore. (This photograph was taken in 1966 by Al D. Girvan) #yegarts #yegdt #yegheritage (at Edmonton City Hall)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Night . Queen Elizabeth outdoor swimming pool John Walters third house built 1899-1901 Practice under the lights . #johnwaltermuseum #edmonton #yeg #history #nightphotography #yegheritage #walterdalebridge #albertahistory #queen #yeg_shooters #travelalberta #house #exploreedmonton #beyeg #practice (at Kinsmen Park Edmonton) https://www.instagram.com/p/B4FjavoAXJd/?igshid=1vwv5ropl7mkc

#johnwaltermuseum#edmonton#yeg#history#nightphotography#yegheritage#walterdalebridge#albertahistory#queen#yeg_shooters#travelalberta#house#exploreedmonton#beyeg#practice

0 notes

Video

instagram

“Everything we have has value.” . . Thank-you to everyone who came out this morning and lived—however briefly—in the Ortona Armoury. We watched you wander around the building and Patrick’s studio like little children in awe of the world. How do we protect these types of spaces and experiences? How do we delight in our environment? And these cultures? What have we already lost or could rediscover? . . Continue this conversation. If you grabbed a postcard, please mail it to the powers-that-be and let them know what you felt and experienced. They need to hear you. We may not build the structures but we are the ones who maintain them. . . #cmedm #cmpreserve #edmonton #heritage #yeg #ortonaarmoury @yegheritage @gdcabnorth @cityofedmonton @cbcedmonton https://www.instagram.com/p/BxkorLGAjug/?igshid=10sjil03l280v

1 note

·

View note

Text

2029: Building Edmonton’s Community Plan for Arts & Heritage

Additional engagement sessions and stories added!

The Edmonton Arts Council, on behalf of the City of Edmonton, is preparing Edmonton’s next comprehensive 10-year Arts and Heritage Plan. Along with project partners the Edmonton Heritage Council, the City of Edmonton, and Arts Habitat Edmonton, work is underway to create a new 10-year Arts & Heritage Plan that will be unique to Edmonton, and will provide strong recommendations that will guide and strengthen the City’s planning, investment, and ongoing development of the arts and heritage sectors.

To create a plan that is truly unique to our city, we want to know your fondest culture memories; the impact of the arts and heritage in your community, on your networks or for your cause; and your aspirations for the future of the arts and heritage sectors in Edmonton.

So far, 41 stories have been shared on the YEG Culture Map and facilitated sector specific sessions are beginning Monday!

Community Stories

Rogers Place

Reconciliation is a gift - watching the unveiling of Alex Janvier's painting rooted me to the heart of Edmonton - A place people have been coming for a thousand years!

Shared by Sanjay Shahani

Image: Tsa Tsa Ke K'e - Iron Foot Place by Alex Janvier, photo by Dwayne Martineau, Laughing Dog Photography.

Queen Elizabeth Pool (old location)

I used to take my children swimming at the Queen Elizabeth Pool. In the summer of 1988, I noticed this big chalk board near the change rooms. I went over to have a closer look. The information on the board was regarding the history of mixed race bathing in Edmonton. That is when I found out that Queen Elizabeth Pool was the first location where Black Edmontonians were allowed to swim in a public place managed by the City of Edmonton.

Shared by Elsa Robinson

Image: Queen Elizabeth Pool c. 1922, photo from the City of Edmonton Archives.

Red Strap Market

This building has had several lives! It is a very important site in the history of women's work and labour in this City, as it once housed the Great West Garment factory, and produced jeans until the early 1980's. Eventually, it became home to the biggest Army & Navy in Edmonton, and was a go-to source for houswares for Edmontonians of all walks of life. This space's last iteration was a the Red Strap Market - a venue for art and craft vendors, host of live music, poetry readings, and dance events, home to artists' studios. A place ahead of it's the by about 10 years. This is a building that needs to be USED and loved, and embraced by the City!

Shared by Sydney Lancaster

Image: Abby Espejo in K O Dance Project YOU/happening, photo by Tracy Kolenchuk.

Harbin Gate

When my relatives visited us, my parents would bring us to the Harbin Gate to take pictures. As a kid, I remember climbing to reach and rub the ball in the guardian lion's mouth for good luck. I didn't realize how special and important the Chinatown Gate was until it was taken away.

Shared by Grace Law

Image: Grace Law at the Harbin Gate c. 1988, photo supplied.

Dr. Wilbert McIntyre Park

This is where Found Festival was born! In 2012 Elena Belyea, Molly Staley, Tori Morrison and Andrew Ritchie founded the Found Festival, a multi-disciplinary found space arts event. In the first year we met at the Gazebo to begin our two day adventure to take in eight one-off performances by emerging artists all over Old Strathcona. It is now 2018 and the festival has grown so much in 7 years! It began with just a few artists thinking "Hey what if we did a festival where we didn't pay for a single venue"

Shared by Andrew Ritchie

Image: Festival goers enjoying a live performance at the 2017 Found Festival, photo by Mat Simpson Photography.

Hawrelak Park

As a University of Alberta student in the early 90's I was living on campus, and stayed for the summer. Edmonton opened itself to me as a place that was not just a grey and white winter landscape. The green hues of the mid-summer led to biking and walking around the river valley.

One of those weekends I stumbled upon the Heritage Days festival and was stunned at the variety of different people, food, dance and craft that was on display. I spent much of that weekend walking down from the U of A campus to just hang out and absorb.

One of my lasting memories of Edmonton... arguably that was when I started to be a nascent "Edmontonian" after several years of just visiting for school.

Shared by Stephen M Williams

Image: Traditional dancers at the 2015 Heritage Festival, photo by Inez Paszewska.

>> Click here to add your story to the YEG Culture Map...

Upcoming Engagement Sessions

We are hosting a suite of in-depth facilitated conversations for arts and heritage organizations, artists, collectives, museums, and others. These facilitated sessions are two hours in length, and will provide an opportunity for members of the arts and heritage sectors to engage in focused discussion, and share their vision for the future of the arts and heritage landscapes.

Theatre Session – March 12, 2018 / 11:00am-1:00pm / CKUA Performance Space, 9804 Jasper Avenue

Ward 8 Public Session – March 12, 2018 / 6:00-8:00pm / ATB Financial Arts Barns, 10330 84 Avenue

Ward 6 Public Session – March 13, 2018 / 6:00-8:00pm / Manning Hall, Art Gallery of Alberta, 2 Sir Winston Churchill Square

Festivals Session – March 14, 2018 / 11:00am-1:00pm / CKUA Performance Space, 9804 Jasper Avenue

Music Session – March 15, 2018 / 6:00-8:00pm / CKUA Performance Space, 9804 Jasper Avenue

Public Art Session – March 16, 2018 / 11:00am-1:00pm/ Art Gallery of Alberta Theatre Lobby, 2 Sir Winston Churchill Square

Heritage Session – March 21, 2018 / 3:00-5:00pm / Prince of Wales Armouries, Jefferson Room, 10440 108 Avenue

Performing Arts Session – April 3, 2018 / 11:00am-1:00pm / Myer Horowitz Theatre, University of Alberta, 8900 114 Street

Heritage Session – April 5, 2018 / 6:00-8:00pm / Prince of Wales Armouries, Lestock Lounge, 10440 108 Avenue

Film & Media Arts Session – April 6, 2018 / 11:00am-1:00pm / Citadel Theatre, Shoctor Lobby, 9828 101A Avenue

Literary Arts Session – April 6, 2018 / 6:00-8:00pm / City Arts Centre, Drama Room, 10943 84 Avenue

Dance Session – April 7, 2018 / 11:00am-1:00pm / Timms Centre Lobby, University of Alberta, 87 Avenue & 112 Street

Visual Arts Session – April 9, 2018 / 11:00am-1:00pm / Allard Hall, MacEwan University, 11104 104 Avenue

If you require ASL interpretation or other assistance, please contact the EAC at [email protected] with the date and venue of the engagement session you will be attending.

>> Click here for all session dates including community pop-up events...