#you are presenting facts incorrectly *or* through a biased reading

Text

Presumptions Part One: At Home And At The Mall

Written By: F. John Surells

Here’s a composition about the thoughts, postulations, and speculations one’s presence at a certain location, or one’s sight of a certain object may engender in a mind so easily inspired. And here’s an attempt to organize miscellaneous musings. Oh, I know that one’s imagination can be sent off wondering and wandering due to many stimuli. But only those who really care about the downtrodden wear expensive dresses with meaningless phrases affixed upon them to expensive upper class get-togethers. Yes, I guess taxing the rich more aggressively would solve all of humanity’s problems.

Nonetheless, we know that “I’ve got my eye on you” can be either a remark of admiration or a threat of surveillance. But I suppose it doesn’t always need to be one of those. Sometimes, as when I stroll through the mall, I catch sight of people and things who and which send my mind wheeling. And then, with senses enlivened, I look at those people and things and wonder if I could know all that’s of importance to, or because of them.

And today I’ve just returned from a walk in the mall. And while walking there I met a stranger whom I’ve decided to recommend to our city’s mayor as a possible writer of Part Two of this piece. Oh, he’s only a factory worker he said. And, he has no writing experience. Yet, I told him that Mayor Jennifer had informed me that it was just such a person as he, that he (the mayor) wished to write in this forum soon.

And, I believe I’ll find solace walking in the mall – until leftists ban that activity too. Their goal seems to be that no one, except they themselves, should enjoy any aspect of human life. But, as long as solitary walks are still legal, here’s a dedication to all the instances when sudden encounters with any type of noun (person, place, or thing) engage our imagination, and change our focus from the stage of the current moment, to either previously, or non-previously considered outcomes and/or ramifications of either past actualities, or future possibilities. Yet, everyone’s mind strays from the present from time to time. That’s what you’d say, right? Well, for my sake please consider what follows now to be a meaningful, although perhaps somewhat arrogant retort.

I’d imagine that if these words could accurately and verifiably offer acknowledgement, documentation, and hope of and for the past, present and future, then I’d be permitted to adjudge them useful and constructive. But they can’t alter all that was and is, still, it may be that they can offer assistance to a search for better days to come.

I like to walk in our city’s largest mall, and sometimes I do enter one or more of the stores therein. And thus it was that one day, inside a consignment store within that mall, I came upon the so-called “Green Flower Pot”. And I must admit its dark green color was what first caught my eye. But then I noticed it also had spots of black which seemed to matter greatly in regard to its overall appearance and aura. Yet, initially I thought its price to be too pricey. Still, its allure was too great, so I purchased it. But as I see it now, here at home, I sense it also has a basic presentation devoid of any attributes a wondering mind may try to assign it. And, I also need to admit that I fear it’s not a flower pot at all, but rather some sort of water or tea dispenser which I’m thinking may have been purposely given a misnomer by the “status-quo” so that group of status could then incorrectly identify it as a relic of the 1960’s; you know, “flower” and “pot”.

Oh, and isn’t it strange how the mind can be stimulated by just the sight of artistic glass? I guess our psyches sometimes sense uncompromising qualities within certain artworks, and then feel they need to incorporate those qualities within themselves. But then, whether such incorporation succeeds or fails, the mind, body and soul are often left in search of certainties.

And the particular constant (as I believe it to be) which I usually seize upon then is the fact that all I really know without question is that many people have labored for many years within my city. And yet, though they’ve been productive members of society, many of them have furthered rumors here which in reality have been found out to be either half-truths or outright lies. And, all their work and gossip spreading has been done in a city known for strange and unbelievable occurrences.

And many is the time I’ve recalled how, inside this city, an unforgiving populace has tried to stymie artistic efforts. And when I think back to those occasions, that’s when I realize how small we as creators of, reflectors upon, and witnesses for art all really are! We advocate for right living, but entrenched biases, which usually attack us from the left, always seek to thwart our goodness.

Yet, I’ve also noticed that despite the vast possibilities of miscellaneous thoughts, one’s mind so often focuses upon all that’s actually never been proven or disproven. Therefore, I’ll not fail to speak of a secondary class of momentary considerations. And they consist of the undesirable occurrences of future chaos and trauma which will be caused by the seemingly casual attitude many Americans have adopted in regard to illegal and non-supervised immigration into their nation. What will the future effects be of allowing great numbers of penniless individuals into the United States? Well, in answering that question one must begin by realizing that these people are in poverty today, and in poverty they’ll remain, no matter be it in the U.S. or elsewhere. The only difference is that in America they’ll greatly contribute to the downfall of the Earth’s last real hope against tyranny and human rights violations.

And I can remember that as a child I was often cautioned about “excrement (my word not theirs) peddlers”. My dad, for one, liked to remind whomever he could that a lot of people could hang degrees on their walls, and especially if their educations were paid for by the government, but few could really effect any worthwhile developments in a wicked world. And rest assured, the admonishments given me by him and others back in those years didn’t fall on deaf ears. And I suppose that’s why I so often find myself pondering the drastic future effects of what’s going on in my nation today. But then, of course we can’t expend all our God given time thinking about the past and future; the present needs to be lived.

And so it was that the other day when my phone rang, and our city’s mayor George Jennifer told me he wished me to contribute to this forum at this time, I told him I’d like to “construct” a composition around my recent encounter with The Green Flower Pot, and perhaps entitle it “Presumptions”. And the mayor answered by saying “John, I know you well enough to expect that your initial reaction to almost anything is immediate concern and fear. And while I’ll expect those apprehensions to appear in your written piece, could you also find a working class person to write a Part Two of “Presumptions”?

“I’ll do that,” I said.

But now, from my own personal experiences, I’d like to relate some random disclosures. And I’m sure that by now anyone reading this knows that F. John Surells is very private in his investigations. Nonetheless, he’s been told by various phone callers that he owes various amounts of money to various people for various reasons. And there are various examples of what I’ve just written, but here are my favorites.

Sergeant Wright told me he was organizing a fundraiser for some elementary school kids, and needed a contribution. And Sara said some of my finances were in disarray. And Rick wanted to aid me with Medicare. But I tried to talk to Rick one day, even though he’s a recording. And I told him I’m not really old, and that my body ages in a fashion similar to a manual transmission that’s always in first gear. And I added that although I may move slowly, I know some people who are constantly driven; actually I said “One might say they’re in constant drive.”

But then, on another day, a friend from Manhattan called to tell me he thought America had a new greatest writer now. “Who is it?” I asked.

“His or her name can’t be divulged now” he answered. “Some say he or she is too controversial, and besides, a lot of people here in Manhattan don’t like him or her.”

And I felt then that probably I shouldn’t pursue that matter any further, and instead told my caller friend that recently, in a dream, I’d met a man of prominence. And he’d written the solutions to all of mankind’s problems on a board with chalk. But then a coalition of political and non-political questioners, blamers, gossipers, and liars had confronted him, and had erased the truth he’d transcribed. And then that coalition had told that man that their goal was to brainwash the youth of America. “And when those youngsters grow to adulthood, they’ll then spread our vileness as if it were truth” they’d said.

But my friend responded to this dream disclosure by saying, “You know, I think you’d better be careful. Over here in New York we’ve actually heard about your haughtiness and refusal to live as the ‘status-quo’ instructs. Maybe the time has come for you to change your ways, or your ‘styles’ at least. And remember, most of the really important literary types are liberals.”

0 notes

Text

COVID-19 Is like an X-ray of Society

In many ways, coronavirus has functioned like an x-ray. With the flip of a switch, it has stripped us of our skin and revealed our internal state, which was once so deliberately hidden, so to avoid the gaze and judgment of the outside world. We are left exposed, vulnerable, illuminated.

In this state, we are confronted with a new awareness: our world as we choose to perceive it does not necessarily match the truth of how it functions. The racism that so many people believe to have been buried in our history long ago now clearly presents itself in the racial demographic data—or lack thereof—for COVID-19. The classism that has divided our society into the haves and have-nots is now revealed with deadly implications, as access to testing or treatment depends on one’s connections and ability to pay, respectively. Numerous other forms of inequality and injustice are becoming apparent, as I will argue throughout this piece—each of which provides further evidence to the point that coronavirus is an x-ray that has quite tragically revealed just how broken our bones are.

When coronavirus first spread through Wuhan, so too did the x-ray’s exposure: illuminating a pervasive fear of the other, and the xenophobia that follows; exposing how we speak before we think, and the extent to which we project our own prejudice. According to press reports, on February 2, an Asian American woman in Chinatown was attacked for wearing a face mask; and on March 10, another Asian American woman was attacked for not wearing a face mask. It seems you’re damned if you do, and you’re damned if you don’t. Consider these stories without the mention of any face mask: two Asian American women were attacked. Our x-ray confirms what it’s like to be a minority in this country. What it’s like to be a woman.

This is what coronavirus looked like when it was “theirs” and not “ours.” But the virus finally did the inevitable and spread to our soil. And so too did the unforgiving gaze of that which strips skin, tears tissue and loosens ligaments. The resultant x-ray image displayed the ease with which we sacrifice our own, as if we had already collectively decided which lives were worth saving—and which were not.

I read a headline on April 20: “73% of Inmates At An Ohio Prison Test Positive For Coronavirus.” Now why is that unsurprising? America’s inmates are some of our most vulnerable people, and they are also some of our least protected. Should we not offer our most protection to our most vulnerable? We do so with children—coddling them with safety precautions and protective measures, so they feel a bit more empowered. A little less vulnerable. Now think about situations of mismatch: where an individual’s relative vulnerability is not mirrored in her relative level of protection. Do you have individuals in mind? Perhaps entire communities? And how are they faring with the pandemic?

Because the prison population is but one example. A community that is overcrowded—in Ohio, specifically, filling nearly 130 percent of intended capacity—insufficiently protected and hence suffering disproportionately. There have been marginal efforts to alleviate this problem, by freeing some inmates, but the efforts themselves are problematic. For one, the numbers released are small, and often even these have sparked political resistance. And I cannot help but wonder, whom do authorities choose to release and why? Because if the release process in any way reflects the incarceration process, something tells me it may not be fair. If white inmates are more readily released than inmates of color, are we not exacerbating the racial disparities in our criminal justice system? Indeed, at the federal level, an algorithm that the Justice Department is relying on for such decisions has raised fears it will produce racially biased results.

In general, data about race and COVID-19 are insufficient. The Trump administration has announced that it will not disclose the details of how the disease is affecting different racial groups until early May—raising the question of whether this delay is being used to gather the most factual and comprehensive data possible, or if instead the delay is obscuring what we already know to be true: minorities, specifically black persons, in our society have time and time again been disproportionately negatively affected during emergency situations or crises. We need not look beyond 2005, when Hurricane Katrina ravaged the same area of New Orleans that is now facing an astonishing COVID-19 infection rate of 1,637.4 per 100,000 people. But if we did, and we jumped back in time to 1927 Mississippi, we would note that of the victims of the state’s Great Flood, 90 percent were black.

Now, we are seeing similar trends, but on a much larger scale. As of April 3, black Americans represented 81 percent of COVID deaths in Milwaukee, despite only making up 26 percent of the population in that area. At that same point in time, 70 percent of Chicago’s deaths from COVID-19 were black Americans, who make up only 29 percent of the city’s population. Similarly, in Michigan, black persons in early April represented 40 percent of COVID-19 related deaths—more than three times their share of the population.

And black Americans are not the only minority group being disproportionately affected. As of mid-April, COVID-19 infection and hospitalization rates among Latinos in Utah were three times those of the state’s white population; and there, as well as in Oregon, New Jersey and Washington— three other states that had released demographic data—the proportion of Latino COVID-19 patients was nearly double that of Latino residents.

Moreover, even the racial and ethnic data that exists are incomplete. There has been at least one instance of a Latino COVID-19 victim’s body being incorrectly identified and recorded as “white” when deceased. Such mistakes would have the dual effect of decreasing the number of counted Latino deaths and increasing the number of counted white deaths—thus reducing the perceived ethnic disparity. And Trump’s hostility toward undocumented Latino immigrants had already made such individuals more fearful about seeking health care. In consequence, such immigrants may be less likely to get tested for COVID-19, again tainting the demographic data.

The pandemic has made it abundantly clear that the well-connected and well-to-do enjoy a degree of privilege that directly benefits their own COVID-specific health outcomes and those of surrounding people, who are presumably from a comparable socioeconomic background. Celebrities and other social elites have been able to be tested for COVID-19 even if they are asymptomatic, when such options have not been readily available to the average person.

If one of these wealthier individuals were to test positive, they would likely have enough square footage in their house to self-quarantine in a relatively comfortable fashion and not put their family members at risk of infection. Furthermore, if they were to develop severe systems, they would also probably have a health insurance plan that would cover their treatment. Now to contrast this situation with individuals who are less socioeconomically stable; they are more likely to live in crowded homes where self-quarantining may not even be possible, not have an insurance plan to cover the costs of COVID-19 care, or might even depend so much on a regular paycheck that they still need to attend work while sick—thus exposing other persons to the virus.

These issues, however, are not the faults of poorer persons, just as they are not the faults of minority groups, or of the incarcerated. The issues are instead rooted in the structural injustices that gave rise to disparities on the basis of wealth, race, ethnicity and criminal status. Perhaps now more than ever before, we can see those structural injustices—illuminated, exposed, revealed. They are, in fact, difficult to ignore.

This, I argue, is the x-ray effect. The coronavirus has spread across the world like a dark substance—blinding us with fear, arresting us in uncertainty. But once we flip that switch, that is, once we ignite the radiation, we are made aware of what exists beneath the surface: all that our aesthetic world has strategically covered up or ignored. And with that awareness comes the responsibility to attend to the issues that have been previously neglected and the persons who have been historically burdened. The examples I offered above are only a few that have come to light since the beginning of our global pandemic. We are also witnessing prejudice against elderly populations, persons with disabilities, rural communities, homeless persons and other vulnerable groups.

So just as an earthquake is bound to first destroy the structures that are least sound, and a hurricane will swallow anything already struggling to stay afloat, a pandemic disproportionately takes the lives already compromised. They are our society’s most vulnerable, and our least protected; not for who they are, but for the meaning and sense of worth that our systems have projected onto them. So, the systems are the problem. And the systems are our bones. The skeletal system of our society, which we expect to support us—not to betray us. But upon closer look, from our pandemic perspective, our bones are broken.

No, shattered.

Source link

The post COVID-19 Is like an X-ray of Society appeared first on The Bleak Report.

from WordPress https://bleakreport.com/covid-19-is-like-an-x-ray-of-society/

0 notes

Text

This is something that's been on my mind for a long time. Long ramble under the cut

TL;DR: Grazer-razor has some of the worst black and white mentality I've ever seen and I can tell he has never critically examined his biases a day in his life.

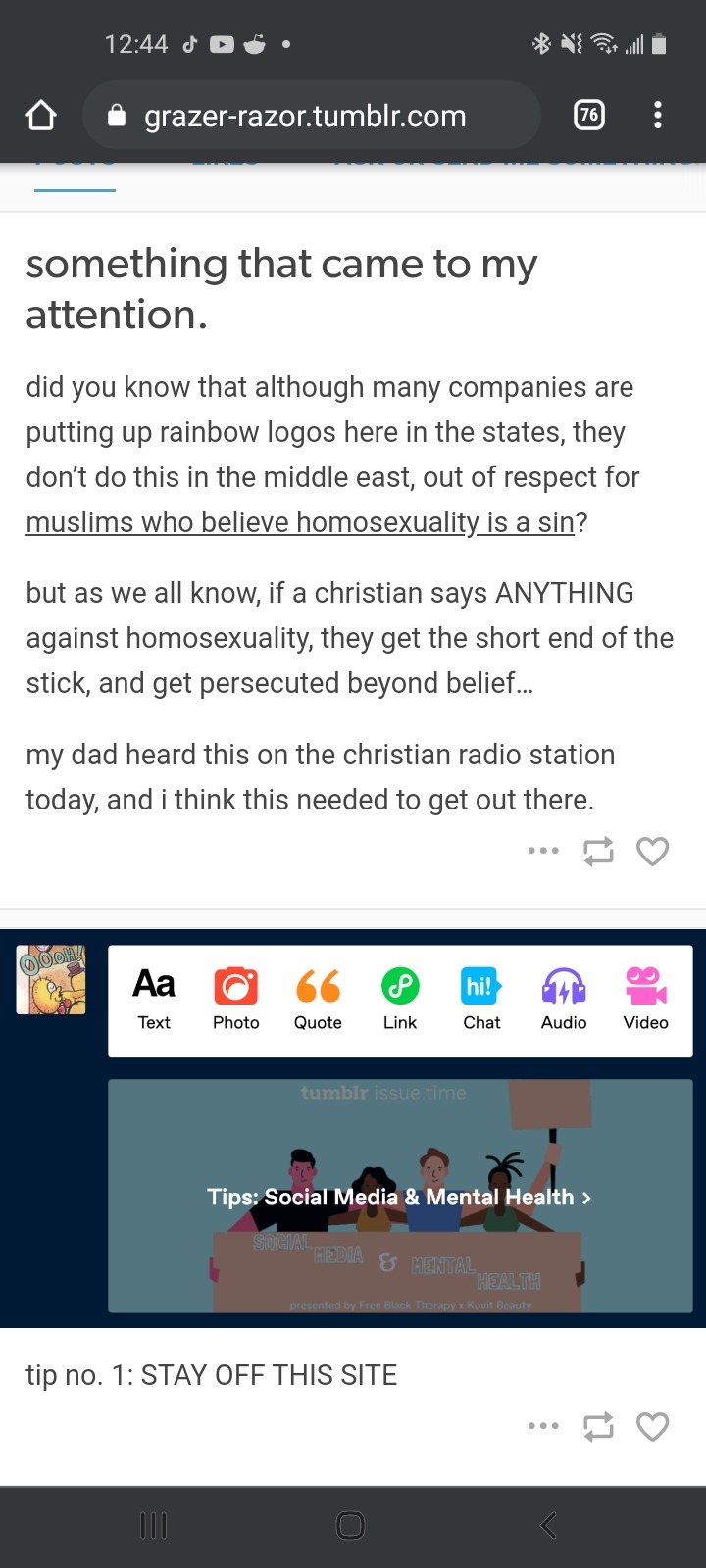

Because I'm a terrible little gremlin who can't leave well enough alone, I've been reading these posts

Ignoring the absolute stupidity of these statements (I'm pretty sure the lack of rainbow logos is because in many middle eastern countries, homosexuality is a crime and these companies just want to make money. But I'mnot going into the nuances and implications of rainbow capitalism today.), something stood out to me.

Does Grazer... genuinely think nobody has ever criticized the Muslim faith? That we all ignore the homophobia present within the religion just because they're a minority? Correct me if I'm wrong, but I've seen even some of the most staunch leftists criticize things like their horrible treatment of homosexuality or the rampant sexism often sanctioned by radicals. Even other Muslims, especially women and lgbt+ Muslims, have been critical of these things.

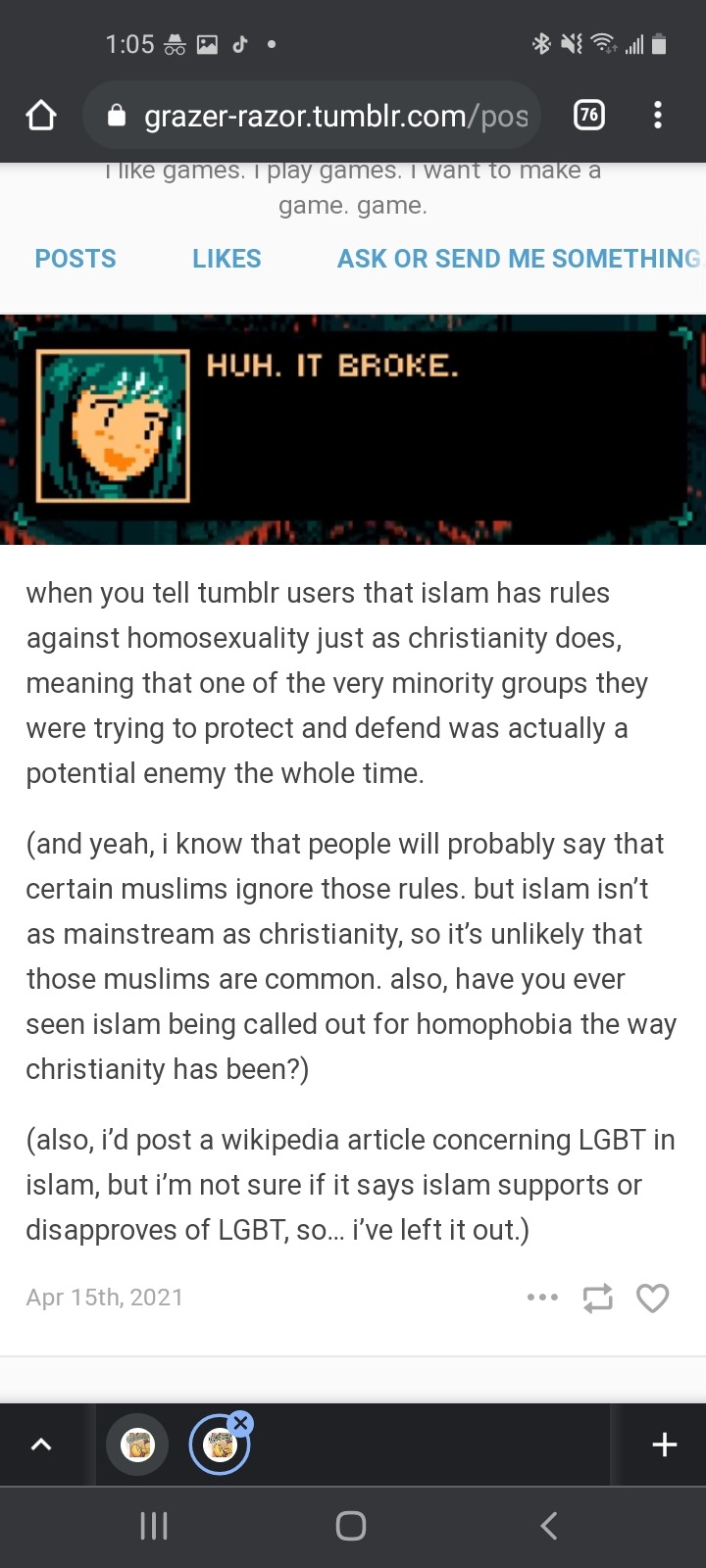

It wouldn't shock me if Grazer believedthat anyone who supports Muslims believes they can do no wrong. After all, he thinks any criticism of Christianity is hatred, and dismisses any harmful things Christians do as not being "real" Christianity in a classic case of the "No True Scotsman" fallacy.

Note how he didn't even respond to the first asks comments, just accused them of being me (because obviously any time someone sees his blog it's all my fault /s)

So it seems like in Grazer's mind, there are only two options when it comes to religion: Uncritically praise and defend everything a religion does no matter how heinous it is and justify it because it's done in a God's name, or condemn anyone who practices it as hateful terrorists. Because he doesn't see people doing the former for Christians, he automatically assumes that they're doing the latter, and vice versa for Muslims.

Also note how he gets mad when muslim faith is "respected" (again, homosexuality is criminalized in many of these areas) but then demands a secular children's show cater to his religion for the sake of his precious childhood.

(Also, can we just talk about the absolute fucking cruelty in this answer? There are people out there that had their childhoods ruined by abuse, illness, losing loved ones, homelessness, poverty, bullying, near-death experiences, having their countries torn apart by war, a shitty foster care system, teen pregnancies, and so many other things that can absolutely destroy a life. Grazer's was ruined by… *checks notes* a cartoon character supporting gay rights and a drag queen singing a cutesy children's song. So yeah, if that's the worst part of his childhood he's pretty damn lucky, and the fact that he has the gall to still complain absolutely makes him selfish and ignorant. It's disrespectful, plain and simple, and if he were truly a good Christian he'd have some compassion.)

Okay, so Grazer has some weird "rules for me but not for thee" shit when it comes to religion. This isn't news. Where am I going with this?

Well, turns out he has this opinion about more than just religion. Know how I know this? His response to ESRB ratings and trigger warnings.

So it seems like Grazer sees the ESRB as some sort of moral compass, in a way. Something being rated E or E10 means it's pure and good and wholly unproblematic, while anything higher means it's evil and disgusting and he can't even look at it.

This is further confirmed by this post, where he flat-out states he sees the ESRB as deeming what things are and are not morally acceptable.

Now Grazer, I'm gonna explain this as best as I can, because it seems like you don't quite understand this. Read very carefully.

This is not the purpose of the ESRB rating system.

I repeat, this is NOT the purpose of the ESRB rating system.

The ESRB does not decide on what is and is not morally correct. It simply says "This game contains these topics, and as such is most suitable for people in this age group.". That's it. It's a guideline, not a rule.

Let's take cartoon violence, for instance. It's a very common warning the ESRB puts on games. Almost every game from Mario to Sonic to Crash Bandicoot and even Monster Tale has this warning. These games are all rated E for everyone. Does this mean those games are promoting violence to children, or claiming things like Bowser kidnapping Peach or Pinstripe trying to gun down Crash are perfectly okay and morally correct? Of course not. It's simply saying that these games contain mild, non-graphic violence, but most children should be able to handle seeing it.

On the other side of the coin, let's take a look at the warnings for nudity and sexual themes. Most games that contain these topics are rated T at the lowest and AO at the highest. This obviously isn't saying that nudity and sex are inherently bad or evil. All it's saying is that these topics are best handled by adults (And, regardless of morality, it is illegal to distribute sexual content to minors unless it's meant to be educational, like a health class textbook).

A few extra points:

. Games can be rated different things in different countries. Different countries have different regulations. Do you know why the blood in Danganronpa is pink? It's because in Japan, games with excessive amounts of blood and gore are given a Z rating (Japan's equivalent to an AO rating). They got around this by making the blood pink, securing the game its desired M rating. Meanwhile here in America, Mortal Kombat is allowed to show as many graphic, brutal deaths as it wants and still receive an M rating.

. ESRB ratings are not legally enforceable. I was so convinced as a 16 year old that the employees at gamestop would try to card me or something when I was picking up a copy of Bayonetta, and I was surprised when they simply rang me up in two seconds, no questions asked. It doesn't happen. For fuck's sake, one of the first games I ever played, at the tender age of four, was Soul Edge. A T rated game. The only instance ESRB ratings are legally enforced is in the case of AO ratings, as these games often contain incredibly graphic violenceor sexual content. If this outrage is coming from the idea that certain ratings will keep younger people from playing these games from a legal standpoint, don't worry. A nine year old is not gonna get arrested for playing Among Us. Just don't buy them GTA San Andreas or Leisure Suit Larry and everything will be fine.

. No two consumers are exactly alike. While one 13 year old may be perfectly fine with the jumpscares in Amnesia, another may be too scared to even go near the piano in Super Mario 64. That doesn't mean either of these games is rated incorrectly. The ESRB is there, once again, as a recommendation for the average consumer, and doesn't take individual experience into account. An individual experience is not their responsibility. It's also on parents (or you yourself!) To decide what the consumer can or can't handle.

"But Haley," I hear you say, "What if this piece of media DOES contain something morally bad?"

Well it's simple. You are allowed to like things AND still criticize the bad parts of it.

Hold on now, I'm not telling you that it's perfectly alright to enjoy things like Birth of a Nation or anything like that! Contrary to popular belief, there are some pieces of media that are truly too steeped in hatred and morally reprehensible things to be supported, even through a critical lense. The only merit things like that have is to serve as a warning: This is a terrible thing made for terrible reasons, and we should not allow it to happen again.

But outside of those rare circumstances, it's not so cut and dry.

Let's take a piece of media i actually enjoy, for instance, so you know I'm not a hypocrite: Persona 5.

Persona 5 is easily one of my favorite games in the Persona series. It does a lot of interesting stuff, the artstyle and soundtrack are (in my opinion) the best in the series, and overall it's very enjoyable for me.

But, like anything, it's not perfect. I'm incredibly uncomfortable with the hypocrisy the game has in regards to the sexualization of teenagers. While Kamoshida is rightfully condemned for his sexualization of teenage girls and Ann's persona awakening comes from rejecting this objectification, the game and story undermine it by not only putting Ann in a sexually revealing outfit, but also making light of Ryuji's sexual harassment by adult men (Allegedly Persona 5 Royal tries to fix this by making the men drag enthusiasts who think Ryuji would look good in drag and giving them more sympathetic personalities, but it's still really weird and hypocritical of the game to do this.). The teenage protagonist is also allowed the option to date adult women, including his teacher, and the game rarely if ever touches on the problems with this.

The game's homophobia also left a bad taste in my mouth. Aside from the aforementioned men who sexually harass Ryuji, the only other canon LGBT+ character is a bar owner who is either a drag queen or a trans woman (or both?). Sure, she's portrayed as being kind and protective of the protagonist, but there isn't much room to interact with her or learn more about her. On top of that, not only can the protagonist not romantically pursue his male friends (A feature that even the SECOND persona game had), he's not even allowed to give them gifts or platonically show affection towards them without the dialogue mocking him. The game that allows a teenage boy to date his teacher won't allow him to simply give his male friends a present.

And yet, despite those criticisms, I do still enjoy the game. I don't consider the game irredeemable garbage based on those poorly handled topics alone. And I also understand that for some people, those topics make them so uncomfortable that they don't want to play the game at all, and I completely respect that.

Criticizing the things you enjoy is not only normal, it's oftentimes healthy. Being able to step back and say "I like this thing, but I don't like the bad things it's done. This thing would be better if these issues were fixed." Sure, sometimes some people tend to complain a bit too much about the media they supposedly enjoy, but for the most part being able to acknowledge the bad with the good is a good skill to have.

Oh, wait, all of this means nothing because Grazer thinks that critically enjoying things is nothing more than an excuse to consume media he doesn't personally agree with. Okay then.

So if he can't even realize something as simple as "it's okay to criticize some parts of media that you otherwise enjoy", how can he be expected to look critically at a religion that he's been raised in and around all his life?

Soooo yeah, Grazer has some serious problems with black and white thinking that he refuses to acknowledge, further worsened by the fact that he's practically been brainwashed into believing that Christianity is the ultimate moral compass that everyone should follow. I understand that this tends to be an issue for neurodivergent people, but it's not an excuse for the actions he does that are related to these things (sending death threats to the ESRB, antagonizing others, etc.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on http://www.justfreelearn.com/index.php/2018/01/a-popular-crime-predicting-algorithms-performed-worse-than-mechanical-turks-in-one-study/

A Popular Crime-Predicting Algorithms Performed Worse Than Mechanical Turks in One Study

The American criminal justice system couldn’t get much less fair. Across the country, some 1.5 million people are locked up in state and federal prisons. More than 600,000 people, the vast majority of whom have yet to be convicted of a crime, sit behind bars in local jails. Black people make up 40 percent of those incarcerated, despite accounting for just 13 percent of the US population.

With the size and cost of jails and prisons rising—not to mention the inherent injustice of the system—cities and states across the country have been lured by tech tools that promise to predict whether someone might commit a crime. These so-called risk assessment algorithms, currently used in states from California to New Jersey, crunch data about a defendant’s history—things like age, gender, and prior convictions—to help courts decide who gets bail, who goes to jail, and who goes free.

But as local governments adopt these tools, and lean on them to inform life-altering decisions, a fundamental question remains: What if these algorithms aren’t actually any better at predicting crime than humans are? What if recidivism isn’t actually that predictable at all?

That’s the question that Dartmouth College researchers Julia Dressel and Hany Farid set out to answer in a new paper published today in the journal Science Advances. They found that one popular risk-assessment algorithm, called Compas, predicts recidivism about as well as a random online poll of people who have no criminal justice training at all.

“There was essentially no difference between people responding to an online survey for a buck and this commercial software being used in the courts,” says Farid, who teaches computer science at Dartmouth. “If this software is only as accurate as untrained people responding to an online survey, I think the courts should consider that when trying to decide how much weight to put on them in making decisions.”

Man Vs Machine

While she was still a student at Dartmouth majoring in computer science and gender studies, Dressel came across a ProPublica investigation that showed just how biased these algorithms can be. That report analyzed Compas’s predictions for some 7,000 defendants in Broward County, Florida, and found that the algorithm was more likely to incorrectly categorize black defendants as having a high risk of reoffending. It was also more likely to incorrectly categorize white defendants as low risk.

That was alarming enough. But Dressel also couldn’t seem to find any research that studied whether these algorithms actually improved on human assessments.

‘There was essentially no difference between people responding to an online survey for a buck and this commercial software being used in the courts.’

Hany Farid, Dartmouth College

“Underlying the whole conversation about algorithms was this assumption that algorithmic prediction was inherently superior to human prediction,” she says. But little proof backed up that assumption; this nascent industry is notoriously secretive about developing these models. So Dressel and her professor, Farid, designed an experiment to test Compas on their own.

Using Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online marketplace where people get paid small amounts to complete simple tasks, the researchers asked about 400 participants to decide whether a given defendant was likely to reoffend based on just seven pieces of data, not including that person’s race. The sample included 1,000 real defendants from Broward County, because ProPublica had already made its data on those people, as well as information on whether they did in fact reoffend, public.

They divided the participants into groups, so that each turk assessed 50 defendants, and gave the following brief description:

The defendant is a [SEX] aged [AGE]. They have been charged with:

[CRIME CHARGE]. This crime is classified as a [CRIMI- NAL DEGREE].

They have been convicted of [NON-JUVENILE PRIOR COUNT] prior crimes.

They have [JUVENILE- FELONY COUNT] juvenile felony charges and

[JUVENILE-MISDEMEANOR COUNT] juvenile misdemeanor charges on their

record.

That’s just seven data points, compared to the 137 that Compas amasses through its defendant questionnaire. In a statement, Equivant says it only uses six of those data points to make its predictions. Still, these untrained online workers were roughly as accurate in their predictions as Compas.

Overall, the turks predicted recidivism with 67 percent accuracy, compared to Compas’ 65 percent. Even without access to a defendant’s race, they also incorrectly predicted that black defendants would reoffend more often than they incorrectly predicted white defendants would reoffend, known as a false positive rate. That indicates that even when racial data isn’t available, certain data points—like number of convictions—can become proxies for race, a central issue with eradicating bias in these algorithms. The Dartmouth researchers’ false positive rate for black defendants was 37 percent, compared to 27 percent for white defendants. That roughly mirrored Compas’ false positive rate of 40 percent for black defendants and 25 percent for white defendants. The researchers repeated the study with another 400 participants, this time providing them with racial data, and the results were largely the same.

“Julia and I are sitting there thinking: How can this be?” Farid says. “How can it be that this software that is commercially available and being used broadly across the country has the same accuracy as mechanical turk users?”

Imperfect Fairness

To validate their findings, Farid and Dressel built their own algorithm, trained it with the data on Broward County, including information on whether people did in fact reoffend. Then, they began testing how many data points the algorithm actually needed to retain the same level of accuracy. If they took away the defendant’s sex or the type of crime the person was charged with, for instance, would it remain just as accurate?

What they found was the algorithm only really required two data points to achieve 65 percent accuracy: the person’s age, and the number of prior convictions. “Basically, if you’re young and have a lot of convictions, you’re high risk, and if you’re old and have few priors, you’re low risk,” Farid says. Of course, this combination of clues also includes racial bias, because of the racial imbalance in convictions in the US.

That suggests that while these seductive and secretive tools claim to surgically pinpoint risk, they may actually be blunt instruments, no better at predicting crime than a bunch of strangers on the internet.

Equivant takes issue with the Dartmouth researchers’ findings. In a statement, the company accused the algorithm the researchers built of something called “overfitting,” meaning that while training the algorithm, they made it too familiar with the data, which could artificially increase the accuracy. But Dressel notes that she and Farid specifically avoided that trap by training the algorithm on just 80 percent of the data, then running the tests on the other 20 percent. None of the samples they tested, in other words, had ever been processed by the algorithm.

Despite its issues with the paper, Equivant also claims that it legitimizes its work. “Instead of being a criticism of the COMPAS assessment, [it] actually adds to a growing number of independent studies that have confirmed that COMPAS achieves good predictability and matches,” the statement reads. Of course, “good predictability” is relative, Dressel says, especially in the context of bail and sentencing. “I think we should expect these tools to perform even better than just satisfactorily,” she says.

The Dartmouth paper is far from the first to raise questions about this specific tool. According to Richard Berk, chair of the University of Pennsylvania’s department of criminology who developed Philadelphia’s probation and parole risk assessment tool, there are superior approaches on the market. Most, however, are being developed by academics, not private institutions that keep their technology under lock and key. “Any tool whose machinery I can’t examine, I’m skeptical about,” Berk says.

While Compas has been on the market since 2000 and has been used widely in states from Florida to Wisconsin, it’s just one of dozens of risk assessments out there. The Dartmouth research doesn’t necessarily apply to all of them, but it does invite further investigation into their relative accuracy.

Still, Berk acknowledges that no tool will ever be perfect or completely fair. It’s unfair to keep someone behind bars who presents no danger to society. But it’s also unfair to let someone out onto the streets who does. Which is worse? Which should the system prioritize? Those are policy questions, not technical ones, but they’re nonetheless critical for the computer scientists developing and analyzing these tools to consider.

“The question is: What are the different kinds of unfairness? How does the model perform for each of them?” he says. “There are tradeoffs between them, and you cannot evaluate the fairness of an instrument unless you consider all of them.”

Neither Farid nor Dressel believes that these algorithms are inherently bad or misleading. Their goal is simply to raise awareness about the accuracy—or lack thereof—of tools that promise superhuman insight into crime prediction, and to demand increased transparency into how they make those decisions.

“Imagine you’re a judge, and you have a commercial piece of software that says we have big data, and it says this person is high risk,” Farid says, “Now imagine I tell you I asked 10 people online the same question, and this is what they said. You’d weigh those things differently.” As it turns out, maybe you shouldn’t.

Source link

0 notes

Text

Introducing the Invisibility Cloak Illusion: We think we’re more observant (and less observed) than everyone else

By guest blogger Juliet Hodges

Most of us tend to think we’re better than average: more competent, honest, talented and compassionate. The latest example of this kind of optimistic self-perception is the “invisibility cloak illusion”. In research published recently in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Erica Boothby and her colleagues show how we have a tendency to believe that we are incredibly socially observant ourselves, while those around us are less so. These assumptions combine to create the illusion that we observe others more than they observe us.

As a first step, the researchers asked participants on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk survey website how much they usually observe other people. Participants indicated that they were more observant of others than they expected the average person to be, whilst they believed they were observed less than other people.

Next the researchers asked students about their experience immediately after lunch in a university canteen. Participants rated themselves almost twice as observant of strangers in the canteen, as these other people were of them. When participants had been dining with friends, they said they had noticed more about their friends than their friends had of them. They also indicated that, when accidentally making eye contact with someone, they felt it was because they were already watching that person – not because they themselves were being watched.

While this provides initial support for the invisibility cloak bias, the researchers also wanted to test this experimentally. They set up a waiting room, where two student participants of the same sex believed they were waiting for the experiment to begin. The participants sat opposite each other for seven minutes, giving them the opportunity to watch one another. They were then taken to separate rooms and given the role of either observer or target (unbeknown to them, whichever role they were given, the other participant was allocated the other role) . The observer’s task was to write down everything they had noticed about the target, while the target’s task was to write down everything they believed the other person would have noticed about them. This process was repeated with multiple pairs of participants and there was a consistent mismatch, showing the invisibility cloak illusion in action: the observers tended to produce far more detailed notes about their fellow participant than the targets expected.

This illusion seems at odds with the “spotlight effect”, which you may recall from a particularly cruel experiment published in 2000: participants were asked to wear a Barry Manilow t-shirt in public, and were convinced more people noticed it than actually had. To understand how the spotlight effect and the invisibility cloak illusion could coexist, the Boothby and her colleagues repeated the waiting room experiment. The only difference was some of the targets wore a t-shirt with a large image of the Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar on it. Targets wearing the t-shirt overestimated how noticeable it was to the observer, replicating the spotlight effect. However, this did not generalise beyond the t-shirt, as they didn’t suspect observers had noticed anything else about them. This shows that the two biases are not incompatible; one can be self-conscious about a particular aspect of themselves, while still believing they go less noticed on the whole.

The mechanisms behind the invisibility cloak illusion seem fairly straightforward. We know we have lots of private thoughts about what we’ve noticed of other people, but we mistakenly overlook that most other people have these kind of private thoughts too. This is compounded by the fact that, when observing others, most of us are careful to be discreet – looking away or pretending to be engrossed in something else – with the result that we rarely notice when other people are watching us. The researchers suggest that this illusion could even be beneficial as it helps us feel a sense of control, a theory that needs to be investigated further.

We need more research to test the robustness of this illusion, especially with older participants. If it does replicate, it may have important implications for our social interactions. For example, it suggests we are likely to underestimate the impact our actions have on others. Take emergency situations: we may look to others to see how they are reacting, while not realising that they in turn are taking their cues from us. It’s worth remembering that we are just as present, and visible, as everyone else.

At the same time, these new findings may be disconcerting for anyone who suffers from painful self-consciousness. But it’s worth remembering that people typically aren’t paying attention to what we’re self-conscious about. Moreover, being observed is not the same thing as being judged. Our own observations of others typically drift through our minds without us paying them much attention – in that regard, the part of the new research in which participants wrote down what they noticed about each other was a rather unnatural task. In real life, it’s likely these details would be forgotten quickly. Earlier, more comforting studies have also shown that other people tend to judge us far less harshly and with more empathy, even when we think we’ve embarrassed ourselves, than we expect.

—The invisibility cloak illusion: People (incorrectly) believe they observe others more than others observe them

Post written for the BPS Research Digest by Juliet Hodges. Juliet has a background in psychology and behavioural economics, and has applied this in advertising and now healthcare. Follow @hulietjodges on Twitter, LinkedIn or read her posts for the Bupa Newsroom here.

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2oqBZqZ

0 notes

Text

Introducing the Invisibility Cloak Illusion: We think we’re more observant (and less observed) than everyone else

By guest blogger Juliet Hodges

Most of us tend to think we’re better than average: more competent, honest, talented and compassionate. The latest example of this kind of optimistic self-perception is the “invisibility cloak illusion”. In research published recently in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Erica Boothby and her colleagues show how we have a tendency to believe that we are incredibly socially observant ourselves, while those around us are less so. These assumptions combine to create the illusion that we observe others more than they observe us.

As a first step, the researchers asked participants on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk survey website how much they usually observe other people. Participants indicated that they were more observant of others than they expected the average person to be, whilst they believed they were observed less than other people.

Next the researchers asked students about their experience immediately after lunch in a university canteen. Participants rated themselves almost twice as observant of strangers in the canteen, as these other people were of them. When participants had been dining with friends, they said they had noticed more about their friends than their friends had of them. They also indicated that, when accidentally making eye contact with someone, they felt it was because they were already watching that person – not because they themselves were being watched.

While this provides initial support for the invisibility cloak bias, the researchers also wanted to test this experimentally. They set up a waiting room, where two student participants of the same sex believed they were waiting for the experiment to begin. The participants sat opposite each other for seven minutes, giving them the opportunity to watch one another. They were then taken to separate rooms and given the role of either observer or target (unbeknown to them, whichever role they were given, the other participant was allocated the other role) . The observer’s task was to write down everything they had noticed about the target, while the target’s task was to write down everything they believed the other person would have noticed about them. This process was repeated with multiple pairs of participants and there was a consistent mismatch, showing the invisibility cloak illusion in action: the observers tended to produce far more detailed notes about their fellow participant than the targets expected.

This illusion seems at odds with the “spotlight effect”, which you may recall from a particularly cruel experiment published in 2000: participants were asked to wear a Barry Manilow t-shirt in public, and were convinced more people noticed it than actually had. To understand how the spotlight effect and the invisibility cloak illusion could coexist, the Boothby and her colleagues repeated the waiting room experiment. The only difference was some of the targets wore a t-shirt with a large image of the Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar on it. Targets wearing the t-shirt overestimated how noticeable it was to the observer, replicating the spotlight effect. However, this did not generalise beyond the t-shirt, as they didn’t suspect observers had noticed anything else about them. This shows that the two biases are not incompatible; one can be self-conscious about a particular aspect of themselves, while still believing they go less noticed on the whole.

The mechanisms behind the invisibility cloak illusion seem fairly straightforward. We know we have lots of private thoughts about what we’ve noticed of other people, but we mistakenly overlook that most other people have these kind of private thoughts too. This is compounded by the fact that, when observing others, most of us are careful to be discreet – looking away or pretending to be engrossed in something else – with the result that we rarely notice when other people are watching us. The researchers suggest that this illusion could even be beneficial as it helps us feel a sense of control, a theory that needs to be investigated further.

We need more research to test the robustness of this illusion, especially with older participants. If it does replicate, it may have important implications for our social interactions. For example, it suggests we are likely to underestimate the impact our actions have on others. Take emergency situations: we may look to others to see how they are reacting, while not realising that they in turn are taking their cues from us. It’s worth remembering that we are just as present, and visible, as everyone else.

At the same time, these new findings may be disconcerting for anyone who suffers from painful self-consciousness. But it’s worth remembering that people typically aren’t paying attention to what we’re self-conscious about. Moreover, being observed is not the same thing as being judged. Our own observations of others typically drift through our minds without us paying them much attention – in that regard, the part of the new research in which participants wrote down what they noticed about each other was a rather unnatural task. In real life, it’s likely these details would be forgotten quickly. Earlier, more comforting studies have also shown that other people tend to judge us far less harshly and with more empathy, even when we think we’ve embarrassed ourselves, than we expect.

—The invisibility cloak illusion: People (incorrectly) believe they observe others more than others observe them

Post written for the BPS Research Digest by Juliet Hodges. Juliet has a background in psychology and behavioural economics, and has applied this in advertising and now healthcare. Follow @hulietjodges on Twitter, LinkedIn or read her posts for the Bupa Newsroom here.

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2oqBZqZ

0 notes

Text

Introducing the Invisibility Cloak Illusion: We think we’re more observant (and less observed) than everyone else

By guest blogger Juliet Hodges

Most of us tend to think we’re better than average: more competent, honest, talented and compassionate. The latest example of this kind of optimistic self-perception is the “invisibility cloak illusion”. In research published recently in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Erica Boothby and her colleagues show how we have a tendency to believe that we are incredibly socially observant ourselves, while those around us are less so. These assumptions combine to create the illusion that we observe others more than they observe us.

As a first step, the researchers asked participants on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk survey website how much they usually observe other people. Participants indicated that they were more observant of others than they expected the average person to be, whilst they believed they were observed less than other people.

Next the researchers asked students about their experience immediately after lunch in a university canteen. Participants rated themselves almost twice as observant of strangers in the canteen, as these other people were of them. When participants had been dining with friends, they said they had noticed more about their friends than their friends had of them. They also indicated that, when accidentally making eye contact with someone, they felt it was because they were already watching that person – not because they themselves were being watched.

While this provides initial support for the invisibility cloak bias, the researchers also wanted to test this experimentally. They set up a waiting room, where two student participants of the same sex believed they were waiting for the experiment to begin. The participants sat opposite each other for seven minutes, giving them the opportunity to watch one another. They were then taken to separate rooms and given the role of either observer or target (unbeknown to them, whichever role they were given, the other participant was allocated the other role) . The observer’s task was to write down everything they had noticed about the target, while the target’s task was to write down everything they believed the other person would have noticed about them. This process was repeated with multiple pairs of participants and there was a consistent mismatch, showing the invisibility cloak illusion in action: the observers tended to produce far more detailed notes about their fellow participant than the targets expected.

This illusion seems at odds with the “spotlight effect”, which you may recall from a particularly cruel experiment published in 2000: participants were asked to wear a Barry Manilow t-shirt in public, and were convinced more people noticed it than actually had. To understand how the spotlight effect and the invisibility cloak illusion could coexist, the Boothby and her colleagues repeated the waiting room experiment. The only difference was some of the targets wore a t-shirt with a large image of the Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar on it. Targets wearing the t-shirt overestimated how noticeable it was to the observer, replicating the spotlight effect. However, this did not generalise beyond the t-shirt, as they didn’t suspect observers had noticed anything else about them. This shows that the two biases are not incompatible; one can be self-conscious about a particular aspect of themselves, while still believing they go less noticed on the whole.

The mechanisms behind the invisibility cloak illusion seem fairly straightforward. We know we have lots of private thoughts about what we’ve noticed of other people, but we mistakenly overlook that most other people have these kind of private thoughts too. This is compounded by the fact that, when observing others, most of us are careful to be discreet – looking away or pretending to be engrossed in something else – with the result that we rarely notice when other people are watching us. The researchers suggest that this illusion could even be beneficial as it helps us feel a sense of control, a theory that needs to be investigated further.

We need more research to test the robustness of this illusion, especially with older participants. If it does replicate, it may have important implications for our social interactions. For example, it suggests we are likely to underestimate the impact our actions have on others. Take emergency situations: we may look to others to see how they are reacting, while not realising that they in turn are taking their cues from us. It’s worth remembering that we are just as present, and visible, as everyone else.

At the same time, these new findings may be disconcerting for anyone who suffers from painful self-consciousness. But it’s worth remembering that people typically aren’t paying attention to what we’re self-conscious about. Moreover, being observed is not the same thing as being judged. Our own observations of others typically drift through our minds without us paying them much attention – in that regard, the part of the new research in which participants wrote down what they noticed about each other was a rather unnatural task. In real life, it’s likely these details would be forgotten quickly. Earlier, more comforting studies have also shown that other people tend to judge us far less harshly and with more empathy, even when we think we’ve embarrassed ourselves, than we expect.

—The invisibility cloak illusion: People (incorrectly) believe they observe others more than others observe them

Post written for the BPS Research Digest by Juliet Hodges. Juliet has a background in psychology and behavioural economics, and has applied this in advertising and now healthcare. Follow @hulietjodges on Twitter, LinkedIn or read her posts for the Bupa Newsroom here.

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2oqBZqZ

0 notes

Text

Introducing the Invisibility Cloak Illusion: We think we’re more observant (and less observed) than everyone else

By guest blogger Juliet Hodges

Most of us tend to think we’re better than average: more competent, honest, talented and compassionate. The latest example of this kind of optimistic self-perception is the “invisibility cloak illusion”. In research published recently in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Erica Boothby and her colleagues show how we have a tendency to believe that we are incredibly socially observant ourselves, while those around us are less so. These assumptions combine to create the illusion that we observe others more than they observe us.

As a first step, the researchers asked participants on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk survey website how much they usually observe other people. Participants indicated that they were more observant of others than they expected the average person to be, whilst they believed they were observed less than other people.

Next the researchers asked students about their experience immediately after lunch in a university canteen. Participants rated themselves almost twice as observant of strangers in the canteen, as these other people were of them. When participants had been dining with friends, they said they had noticed more about their friends than their friends had of them. They also indicated that, when accidentally making eye contact with someone, they felt it was because they were already watching that person – not because they themselves were being watched.

While this provides initial support for the invisibility cloak bias, the researchers also wanted to test this experimentally. They set up a waiting room, where two student participants of the same sex believed they were waiting for the experiment to begin. The participants sat opposite each other for seven minutes, giving them the opportunity to watch one another. They were then taken to separate rooms and given the role of either observer or target (unbeknown to them, whichever role they were given, the other participant was allocated the other role) . The observer’s task was to write down everything they had noticed about the target, while the target’s task was to write down everything they believed the other person would have noticed about them. This process was repeated with multiple pairs of participants and there was a consistent mismatch, showing the invisibility cloak illusion in action: the observers tended to produce far more detailed notes about their fellow participant than the targets expected.

This illusion seems at odds with the “spotlight effect”, which you may recall from a particularly cruel experiment published in 2000: participants were asked to wear a Barry Manilow t-shirt in public, and were convinced more people noticed it than actually had. To understand how the spotlight effect and the invisibility cloak illusion could coexist, the Boothby and her colleagues repeated the waiting room experiment. The only difference was some of the targets wore a t-shirt with a large image of the Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar on it. Targets wearing the t-shirt overestimated how noticeable it was to the observer, replicating the spotlight effect. However, this did not generalise beyond the t-shirt, as they didn’t suspect observers had noticed anything else about them. This shows that the two biases are not incompatible; one can be self-conscious about a particular aspect of themselves, while still believing they go less noticed on the whole.

The mechanisms behind the invisibility cloak illusion seem fairly straightforward. We know we have lots of private thoughts about what we’ve noticed of other people, but we mistakenly overlook that most other people have these kind of private thoughts too. This is compounded by the fact that, when observing others, most of us are careful to be discreet – looking away or pretending to be engrossed in something else – with the result that we rarely notice when other people are watching us. The researchers suggest that this illusion could even be beneficial as it helps us feel a sense of control, a theory that needs to be investigated further.

We need more research to test the robustness of this illusion, especially with older participants. If it does replicate, it may have important implications for our social interactions. For example, it suggests we are likely to underestimate the impact our actions have on others. Take emergency situations: we may look to others to see how they are reacting, while not realising that they in turn are taking their cues from us. It’s worth remembering that we are just as present, and visible, as everyone else.

At the same time, these new findings may be disconcerting for anyone who suffers from painful self-consciousness. But it’s worth remembering that people typically aren’t paying attention to what we’re self-conscious about. Moreover, being observed is not the same thing as being judged. Our own observations of others typically drift through our minds without us paying them much attention – in that regard, the part of the new research in which participants wrote down what they noticed about each other was a rather unnatural task. In real life, it’s likely these details would be forgotten quickly. Earlier, more comforting studies have also shown that other people tend to judge us far less harshly and with more empathy, even when we think we’ve embarrassed ourselves, than we expect.

—The invisibility cloak illusion: People (incorrectly) believe they observe others more than others observe them

Post written for the BPS Research Digest by Juliet Hodges. Juliet has a background in psychology and behavioural economics, and has applied this in advertising and now healthcare. Follow @hulietjodges on Twitter, LinkedIn or read her posts for the Bupa Newsroom here.

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2oqBZqZ

0 notes

Text

Introducing the Invisibility Cloak Illusion: We think we’re more observant (and less observed) than everyone else

By guest blogger Juliet Hodges

Most of us tend to think we’re better than average: more competent, honest, talented and compassionate. The latest example of this kind of optimistic self-perception is the “invisibility cloak illusion”. In research published recently in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Erica Boothby and her colleagues show how we have a tendency to believe that we are incredibly socially observant ourselves, while those around us are less so. These assumptions combine to create the illusion that we observe others more than they observe us.

As a first step, the researchers asked participants on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk survey website how much they usually observe other people. Participants indicated that they were more observant of others than they expected the average person to be, whilst they believed they were observed less than other people.

Next the researchers asked students about their experience immediately after lunch in a university canteen. Participants rated themselves almost twice as observant of strangers in the canteen, as these other people were of them. When participants had been dining with friends, they said they had noticed more about their friends than their friends had of them. They also indicated that, when accidentally making eye contact with someone, they felt it was because they were already watching that person – not because they themselves were being watched.

While this provides initial support for the invisibility cloak bias, the researchers also wanted to test this experimentally. They set up a waiting room, where two student participants of the same sex believed they were waiting for the experiment to begin. The participants sat opposite each other for seven minutes, giving them the opportunity to watch one another. They were then taken to separate rooms and given the role of either observer or target (unbeknown to them, whichever role they were given, the other participant was allocated the other role) . The observer’s task was to write down everything they had noticed about the target, while the target’s task was to write down everything they believed the other person would have noticed about them. This process was repeated with multiple pairs of participants and there was a consistent mismatch, showing the invisibility cloak illusion in action: the observers tended to produce far more detailed notes about their fellow participant than the targets expected.

This illusion seems at odds with the “spotlight effect”, which you may recall from a particularly cruel experiment published in 2000: participants were asked to wear a Barry Manilow t-shirt in public, and were convinced more people noticed it than actually had. To understand how the spotlight effect and the invisibility cloak illusion could coexist, the Boothby and her colleagues repeated the waiting room experiment. The only difference was some of the targets wore a t-shirt with a large image of the Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar on it. Targets wearing the t-shirt overestimated how noticeable it was to the observer, replicating the spotlight effect. However, this did not generalise beyond the t-shirt, as they didn’t suspect observers had noticed anything else about them. This shows that the two biases are not incompatible; one can be self-conscious about a particular aspect of themselves, while still believing they go less noticed on the whole.

The mechanisms behind the invisibility cloak illusion seem fairly straightforward. We know we have lots of private thoughts about what we’ve noticed of other people, but we mistakenly overlook that most other people have these kind of private thoughts too. This is compounded by the fact that, when observing others, most of us are careful to be discreet – looking away or pretending to be engrossed in something else – with the result that we rarely notice when other people are watching us. The researchers suggest that this illusion could even be beneficial as it helps us feel a sense of control, a theory that needs to be investigated further.

We need more research to test the robustness of this illusion, especially with older participants. If it does replicate, it may have important implications for our social interactions. For example, it suggests we are likely to underestimate the impact our actions have on others. Take emergency situations: we may look to others to see how they are reacting, while not realising that they in turn are taking their cues from us. It’s worth remembering that we are just as present, and visible, as everyone else.

At the same time, these new findings may be disconcerting for anyone who suffers from painful self-consciousness. But it’s worth remembering that people typically aren’t paying attention to what we’re self-conscious about. Moreover, being observed is not the same thing as being judged. Our own observations of others typically drift through our minds without us paying them much attention – in that regard, the part of the new research in which participants wrote down what they noticed about each other was a rather unnatural task. In real life, it’s likely these details would be forgotten quickly. Earlier, more comforting studies have also shown that other people tend to judge us far less harshly and with more empathy, even when we think we’ve embarrassed ourselves, than we expect.

—The invisibility cloak illusion: People (incorrectly) believe they observe others more than others observe them

Post written for the BPS Research Digest by Juliet Hodges. Juliet has a background in psychology and behavioural economics, and has applied this in advertising and now healthcare. Follow @hulietjodges on Twitter, LinkedIn or read her posts for the Bupa Newsroom here.

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2oqBZqZ

0 notes

Text

Introducing the Invisibility Cloak Illusion: We think we’re more observant (and less observed) than everyone else

By guest blogger Juliet Hodges

Most of us tend to think we’re better than average: more competent, honest, talented and compassionate. The latest example of this kind of optimistic self-perception is the “invisibility cloak illusion”. In research published recently in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Erica Boothby and her colleagues show how we have a tendency to believe that we are incredibly socially observant ourselves, while those around us are less so. These assumptions combine to create the illusion that we observe others more than they observe us.

As a first step, the researchers asked participants on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk survey website how much they usually observe other people. Participants indicated that they were more observant of others than they expected the average person to be, whilst they believed they were observed less than other people.

Next the researchers asked students about their experience immediately after lunch in a university canteen. Participants rated themselves almost twice as observant of strangers in the canteen, as these other people were of them. When participants had been dining with friends, they said they had noticed more about their friends than their friends had of them. They also indicated that, when accidentally making eye contact with someone, they felt it was because they were already watching that person – not because they themselves were being watched.

While this provides initial support for the invisibility cloak bias, the researchers also wanted to test this experimentally. They set up a waiting room, where two student participants of the same sex believed they were waiting for the experiment to begin. The participants sat opposite each other for seven minutes, giving them the opportunity to watch one another. They were then taken to separate rooms and given the role of either observer or target (unbeknown to them, whichever role they were given, the other participant was allocated the other role) . The observer’s task was to write down everything they had noticed about the target, while the target’s task was to write down everything they believed the other person would have noticed about them. This process was repeated with multiple pairs of participants and there was a consistent mismatch, showing the invisibility cloak illusion in action: the observers tended to produce far more detailed notes about their fellow participant than the targets expected.

This illusion seems at odds with the “spotlight effect”, which you may recall from a particularly cruel experiment published in 2000: participants were asked to wear a Barry Manilow t-shirt in public, and were convinced more people noticed it than actually had. To understand how the spotlight effect and the invisibility cloak illusion could coexist, the Boothby and her colleagues repeated the waiting room experiment. The only difference was some of the targets wore a t-shirt with a large image of the Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar on it. Targets wearing the t-shirt overestimated how noticeable it was to the observer, replicating the spotlight effect. However, this did not generalise beyond the t-shirt, as they didn’t suspect observers had noticed anything else about them. This shows that the two biases are not incompatible; one can be self-conscious about a particular aspect of themselves, while still believing they go less noticed on the whole.

The mechanisms behind the invisibility cloak illusion seem fairly straightforward. We know we have lots of private thoughts about what we’ve noticed of other people, but we mistakenly overlook that most other people have these kind of private thoughts too. This is compounded by the fact that, when observing others, most of us are careful to be discreet – looking away or pretending to be engrossed in something else – with the result that we rarely notice when other people are watching us. The researchers suggest that this illusion could even be beneficial as it helps us feel a sense of control, a theory that needs to be investigated further.

We need more research to test the robustness of this illusion, especially with older participants. If it does replicate, it may have important implications for our social interactions. For example, it suggests we are likely to underestimate the impact our actions have on others. Take emergency situations: we may look to others to see how they are reacting, while not realising that they in turn are taking their cues from us. It’s worth remembering that we are just as present, and visible, as everyone else.

At the same time, these new findings may be disconcerting for anyone who suffers from painful self-consciousness. But it’s worth remembering that people typically aren’t paying attention to what we’re self-conscious about. Moreover, being observed is not the same thing as being judged. Our own observations of others typically drift through our minds without us paying them much attention – in that regard, the part of the new research in which participants wrote down what they noticed about each other was a rather unnatural task. In real life, it’s likely these details would be forgotten quickly. Earlier, more comforting studies have also shown that other people tend to judge us far less harshly and with more empathy, even when we think we’ve embarrassed ourselves, than we expect.

—The invisibility cloak illusion: People (incorrectly) believe they observe others more than others observe them

Post written for the BPS Research Digest by Juliet Hodges. Juliet has a background in psychology and behavioural economics, and has applied this in advertising and now healthcare. Follow @hulietjodges on Twitter, LinkedIn or read her posts for the Bupa Newsroom here.

from DIYS http://ift.tt/2oqBZqZ

0 notes

Text

Introducing the Invisibility Cloak Illusion: We think we’re more observant (and less observed) than everyone else

By guest blogger Juliet Hodges

Most of us tend to think we’re better than average: more competent, honest, talented and compassionate. The latest example of this kind of optimistic self-perception is the “invisibility cloak illusion”. In research published recently in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Erica Boothby and her colleagues show how we have a tendency to believe that we are incredibly socially observant ourselves, while those around us are less so. These assumptions combine to create the illusion that we observe others more than they observe us.

As a first step, the researchers asked participants on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk survey website how much they usually observe other people. Participants indicated that they were more observant of others than they expected the average person to be, whilst they believed they were observed less than other people.

Next the researchers asked students about their experience immediately after lunch in a university canteen. Participants rated themselves almost twice as observant of strangers in the canteen, as these other people were of them. When participants had been dining with friends, they said they had noticed more about their friends than their friends had of them. They also indicated that, when accidentally making eye contact with someone, they felt it was because they were already watching that person – not because they themselves were being watched.

While this provides initial support for the invisibility cloak bias, the researchers also wanted to test this experimentally. They set up a waiting room, where two student participants of the same sex believed they were waiting for the experiment to begin. The participants sat opposite each other for seven minutes, giving them the opportunity to watch one another. They were then taken to separate rooms and given the role of either observer or target (unbeknown to them, whichever role they were given, the other participant was allocated the other role) . The observer’s task was to write down everything they had noticed about the target, while the target’s task was to write down everything they believed the other person would have noticed about them. This process was repeated with multiple pairs of participants and there was a consistent mismatch, showing the invisibility cloak illusion in action: the observers tended to produce far more detailed notes about their fellow participant than the targets expected.