Text

Cultural and Societal Relevance of Nude Photography

In the 21st century, nude photography has transcended its original status as a purely aesthetic or erotic endeavor. It has become a cultural battlefield and a platform for powerful personal expression. At a time when social media filters dominate how we perceive ourselves, nude photography offers an antidote: raw, unfiltered humanity. The genre today navigates issues like censorship, body image, gender diversity, and empowerment—and does so through the most universal subject of all: the human body.

A. The Body as Identity

The nude photograph is never just a body. It is an expression of self—of vulnerability, defiance, heritage, and truth. In an era of rapid cultural change, artists and models use nudity to explore who they are and how they are seen.

Laura Aguilar’s nude self-portraits explore size, ethnicity, and queerness, placing marginalized bodies in poetic, natural landscapes.

Laura Aguilar, a Chicana, queer artist, placed her nude body in the desert, against rocks and earth, asserting a deep connection to land and heritage. Her work confronts invisibility—reclaiming space for fat, queer, and Latina bodies in the fine art world.

Today’s artists don’t photograph nudes simply to admire beauty. They use the body to critique racism, colonialism, ableism, and heteronormativity. The nude becomes a political canvas.

B. Body Positivity and Diversity

Nude photography today is increasingly inclusive. Where once idealized forms dominated—slim, white, able-bodied—contemporary photographers showcase the full spectrum of human form.

Shoog McDaniel creates joyful, tender portraits of fat, queer, and disabled bodies—redefining beauty outside commercial norms.

Photographers like Shoog McDaniel, Jess T. Dugan, and Lia Clay Miller center bodies that are rarely shown nude in traditional media. Their work is not only beautiful—it is revolutionary. It celebrates scars, stretch marks, folds, and physical uniqueness with reverence.

This movement toward body neutrality—accepting the body not for its appearance, but for its reality—is reshaping how we understand nudity in visual culture.

Dugan’s portraits explore masculinity and tenderness among queer individuals, often through soft, intimate nudes.

C. Gender, Sexuality, and the Non-Binary Nude

Traditional nude art upheld binary gender roles—male as subject, female as object. Today’s photography challenges that framework, offering space for trans, non-binary, and gender-fluid representations.

Del LaGrace Volcano, a genderqueer photographer, uses their own body and that of others to question gender expectations in nude art.

Del LaGrace Volcano documents intersex and gender-variant bodies with directness and dignity. Their work confronts society’s discomfort with ambiguity, showing how the nude can resist rigid categories.

Other artists—like Alok Vaid-Menon in self-portraiture, or Zanele Muholi in high-contrast black-and-white—blur the line between masculine and feminine. They reject the notion that nudity must imply gender conformity.

D. The Politics of the Gaze

Who photographs the nude—and who is photographed—has always mattered. The "male gaze", a term coined by Laura Mulvey, describes how women are traditionally depicted as passive objects for male pleasure in visual culture.

Contemporary nude photography increasingly works to subvert this gaze. Many artists flip the script—using self-portraiture, collaborative shoots, and consent-driven processes to return agency to the subject.

Mickalene Thomas reclaims 19th-century nude tropes by placing Black women front and center—in control, adorned, empowered.

Mickalene Thomas, a queer Black artist, reinterprets classical nudes (like Courbet’s L’Origine du monde) by featuring bold, decorated Black women. Her nudes are strong, self-possessed, and aware of their history.

Similarly, Amalia Ulman and Deana Lawson critique the objectification of women by staging highly stylized, performative nudes—subverting tropes of pornography, advertising, and art history.

E. Nudity and Censorship in the Digital Age

Despite modern acceptance of the body in art, censorship remains a pressing issue. Social media platforms routinely delete or shadow-ban images with visible nipples, genitals, or even suggestive skin—especially if the subjects are women, nonbinary, or nonwhite.

This uneven enforcement has spurred activism among artists. Hashtags like #FreeTheNipple and #BodyPositiveArt resist these restrictions. Photographers increasingly build their own platforms (Patreon, Substack, OnlyFans) to avoid censorship.

Byström’s pastel-toned, intimate self-portraits feature body hair, period stains, and imperfect skin—challenging social taboos around the female nude.

Arvida Byström uses photography and social media to challenge Instagram’s sanitized beauty norms. Her work features menstrual blood, acne, unshaved armpits—elements often censored or stigmatized.

Ironically, art institutions that once dismissed nude photography now fight to display it, while digital platforms enforce puritanical standards that echo 19th-century censorship.

F. The Nude as Empowerment, Not Exploitation

Some argue that nude photography objectifies and exploits. This is true when ethics are ignored. However, when models are collaborators—and not just subjects—nudity becomes empowering.

Consent is critical. Professional photographers now engage in pre-shoot conversations, share concepts in advance, and invite models to contribute ideas. This shifts the power dynamic and ensures the resulting image reflects agency.

Photographer Meghan Holmes creates nude portraits in dialogue with her subjects, producing images rooted in mutual trust and shared vision.

Models report feeling liberated when they participate in creating their image—especially when the goal is personal expression, not commercial consumption.

Nude self-portraiture, particularly among women, trans, and nonbinary artists, is increasingly used as a form of self-reclamation. It counters shame and invites visibility.

G. Why the Nude Matters Today

In a world of digital manipulation, beauty filters, and AI-generated perfection, nude photography is perhaps more relevant than ever. It shows what is real. It reveals the stories etched into our skin—the scars, the stretch, the softness, the strength.

Nude photography:

Fights against body shame

Defies censorship and erasure

Expands the definition of beauty

Supports gender and sexual freedom

Invites emotional truth and empathy

Connects us to history, myth, and mortality

In essence, the nude reminds us that we are more than clothes, roles, and appearances—we are bodies that carry pain, power, and meaning.

Image Recap: Contemporary Cultural Relevance

Artist

Example Work

Cultural Relevance

Laura Aguilar

Nature Self-Portraits

Queer/Latina identity and body inclusion

Shoog McDaniel

Fat Queer Bodies in Nature

Joyful defiance of beauty norms

Zanele Muholi

Somnyama Ngonyama

Race, queerness, political resistance

Del LaGrace Volcano

Herm Body

Gender variance, intersex visibility

Mickalene Thomas

Origin of the Universe I

Reclaiming the Black female nude

Arvida Byström

Body Hair & Periods

Challenging social media taboos

Jess T. Dugan

Every Breath We Drew

Queer intimacy and masculinity

Conclusion: The Nude Is Not Going Away—It’s Evolving

Far from irrelevant or outdated, nude photography is a vital, evolving form of communication. It helps individuals feel seen in a world that often tells them to hide. It forces viewers to confront their assumptions about gender, race, beauty, and shame. It challenges censorship, resists erasure, and invites freedom.

In the hands of today’s artists, the nude is not just a subject. It is a statement.

0 notes

Text

The Evolution of Nude Photography (20th–21st Century)

As photography matured into both an art form and a cultural mirror, its treatment of the nude body evolved with it. Nude photography has continuously shifted—guided by social mores, political movements, aesthetic philosophies, and advances in technology. From pictorialism and modernism to postmodern identity politics and the digital revolution, photographers have used the nude to explore abstraction, sexuality, gender, power, and freedom.

A. Early 20th Century: Formalism and Sculptural Abstraction

In the early 20th century, photography distanced itself from painting and sought its own visual language. The nude became a vehicle for formal exploration—light, texture, geometry, and symmetry.

Edward Weston’s sculptural nudes strip away identity, emphasizing light and form over personality or eroticism.

Edward Weston is one of the foundational figures in nude photography. His 1920s–30s black-and-white images, particularly of his muse Charis Wilson, reduced the body to curves, angles, and shadow—transforming flesh into sculpture. Weston’s approach was modernist: emotion was subdued, and the body became an abstract, formal study.

Imogen Cunningham blended intimacy and elegance, emphasizing the relationship between body and light.

Imogen Cunningham, a pioneering female photographer, softened this formalism. Her nudes—often close-cropped and bathed in natural light—emphasized vulnerability and intimacy. She was among the first to photograph older bodies and male nudes with empathy and grace.

B. Mid-20th Century: Surrealism, Eroticism, and Psychological Depth

By the 1930s–1950s, surrealism and psychoanalysis entered visual culture. Nude photography began reflecting unconscious desires, dreams, and the inner psyche.

Man Ray's experimental techniques (solarization, double exposure) created dreamlike, abstracted nude figures.

Man Ray, a key figure in surrealist photography, used solarization and abstraction to create disorienting, eroticized images of the body. His most famous work, Le Violon d’Ingres, metaphorically treats the female back as a violin, turning the nude into both art and object.

Kertész’s distorted nudes challenge beauty norms, using mirrors to warp perception and symbolism.

André Kertész produced a famous series of distorted nude portraits using funhouse mirrors. These works suggested how fragile and fluid our perceptions of the body—and identity—can be.

Meanwhile, fashion photographers like Horst P. Horst brought high aesthetics to the nude form, often blending glamour, sculpture, and art deco styling.

C. The Sexual Revolution and Artistic Liberation (1960s–1980s)

The 1960s and 70s changed everything. The sexual revolution, civil rights movements, second-wave feminism, and gay liberation transformed how nudity was seen in both public and private spaces. Nude photography began to confront taboos and claim space as both artistic expression and social critique.

Mapplethorpe’s nudes—both classical and controversial—blurred the lines between elegance, sexuality, and power.

Robert Mapplethorpe remains one of the most debated nude photographers of the 20th century. His images of Black male bodies, leather-clad gay men, and flowers were meticulously composed—balancing elegance and provocation. His work was accused of obscenity by U.S. politicians, raising critical questions about race, eroticism, censorship, and the politics of the gaze.

Woodman’s blurred, ghostlike nudes explore identity, loss, and femininity through intimate self-portraiture.

Francesca Woodman, in contrast, explored the nude through introspection. Often photographing herself nude in abandoned spaces, her images evoke themes of transformation, invisibility, and emotional fragility. Her work resonates deeply with feminist and existential themes.

D. Feminist and Conceptual Nudes (1970s–1990s)

As feminist art gained ground, the nude was reclaimed from the male gaze. Female artists began to photograph themselves—not as objects, but as subjects with agency.

Cindy Sherman uses nudity (or the suggestion of it) to parody stereotypes and critique visual tropes in media.

Cindy Sherman constructed elaborate characters and scenes, using her own body as a canvas. While not always nude, her work deconstructed the tropes of women in cinema and art, revealing how gender, power, and appearance are manufactured.

Wilke used her body and chewing-gum “scars” to critique beauty standards, commodification, and sexual politics.

Hannah Wilke posed nude with gum sculptures placed on her skin—turning her body into both artwork and battlefield. Her work was raw, confrontational, and deeply feminist.

E. Diversity, Identity, and the Digital Age (2000s–Present)

The 21st century expanded the boundaries of nude photography. The body became a site of activism, vulnerability, and identity reclamation. No longer limited to Eurocentric, binary ideals, contemporary nude photography now celebrates a spectrum of genders, races, and body types.

Zanele Muholi uses self-portraiture to confront colonialism, queerness, and Black identity. Their nudity is both armor and truth.

Zanele Muholi, a South African visual activist, photographs themselves nude in high-contrast lighting. Their self-portraits confront race, queerness, and trauma, blending vulnerability with defiance. These images have been exhibited worldwide and are part of a critical conversation on identity politics in art.

Spencer Tunick organizes mass nude installations to emphasize human vulnerability, unity, and environmental urgency.

Spencer Tunick stages thousands of nude bodies in large-scale public spaces. His images are not sexual; they speak to collectivity, environmentalism, and social anonymity. The repetition of form in his work echoes ancient statues—but with modern political overtones.

Shoog McDaniel celebrates fat, queer, and disabled bodies in nature—reclaiming beauty for the marginalized.

Shoog McDaniel, a queer, non-binary artist, uses natural landscapes to photograph fat and queer bodies in tender, joyful settings. Their work directly resists societal beauty standards and reframes nudity as liberation and healing.

F. Social Media, Censorship, and the Future

In today’s world, nude photography exists in tension with both liberation and suppression. On one hand, platforms like Instagram and Patreon have created spaces for photographers and models to share work directly with audiences. On the other, algorithms and content policies often censor artistic nudity—especially queer, nonwhite, or nonbinary bodies.

Photographers today often navigate the blurred line between art and censorship, working under ever-changing digital standards. Yet despite these barriers, the nude remains as culturally powerful as ever.

Petra Collins' dreamy, pastel-infused nudes explore adolescent femininity, desire, and vulnerability in the digital age.

Petra Collins, Harley Weir, and others have embraced a “soft” aesthetic—blurred edges, pastel hues, and emotionally charged nudity that challenges hard, traditional notions of sexuality and dominance.

Conclusion: A Medium That Reflects Humanity

From Edward Weston's abstract torsos to Shoog McDaniel's joyous queer naturism, nude photography has transformed into a space of profound diversity, creativity, and cultural critique. It is no longer about the ideal—it is about the real. It is about reclaiming the body from shame, from censorship, and from rigid expectation.

Through each era, the nude in photography has reflected the truths and tensions of its time. As long as people continue to question who we are, what it means to be seen, and how to tell the story of the body—nude photography will remain vital.

Timeline of Key Photographers and Movements

Era

Photographer

Notable Work

Themes

1920s–30s

Edward Weston

Nude Charis, 1936

Form, abstraction

1920s

Imogen Cunningham

Male Nudes

Intimacy, emotion

1930s

Man Ray

Solarized Nudes

Surrealism, eroticism

1930s

André Kertész

Distortions Series

Identity, perception

1970s–80s

Robert Mapplethorpe

Ajitto

Race, sexuality, control

1970s

Francesca Woodman

Self-Portraits

Feminism, fragility

1970s–90s

Cindy Sherman

Untitled Film Stills

Gender roles, parody

2000s–Now

Zanele Muholi

Somnyama Ngonyama

Activism, Black identity

2000s–Now

Spencer Tunick

Mass Nudes

Environment, unity

2010s–Now

Shoog McDaniel

Queer Bodies in Nature

Inclusion, joy, resistance

0 notes

Text

The History of Nude Art

The nude has served as a central theme in art for over 30,000 years. From prehistoric fertility figurines to digital photography, the human form has been portrayed to express ideals of beauty, divinity, mortality, power, and vulnerability. Far from being static, the meaning of the nude has evolved alongside shifts in culture, religion, politics, and technology. To understand nude photography, one must first appreciate this lineage.

A. Prehistoric and Ancient Civilizations

Venus of Willendorf – A Paleolithic limestone figurine representing fertility, abundance, and femininity.

The earliest known nude artworks, such as the Venus of Willendorf, were created during the Upper Paleolithic era. These small figurines, often with exaggerated breasts and hips, were likely fertility symbols or icons of goddess worship. Far from sexualized in a modern sense, these nudes conveyed spiritual and survivalist ideals, emphasizing the power of the female form to give life.

Ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Hindu cultures also portrayed the nude, although with different symbolic values. In Egyptian art, nudity was often reserved for servants or children, while gods and royalty were depicted clothed. However, in India, the nude was—and still is—integral to sacred sculpture.

Erotic reliefs from the Khajuraho temples celebrate sexuality and spirituality as unified expressions.

Greek and Roman civilizations marked the beginning of the nude as an idealized form of beauty, philosophy, and heroism. Sculptures like Doryphoros by Polykleitos and Venus de Milo reflected their belief that the nude body was a reflection of divine order and harmony.

Venus de Milo – A Roman copy of a Greek sculpture depicting the goddess Aphrodite (Venus), an enduring icon of classical nude beauty.

B. The Renaissance and the Revival of the Nude

The medieval period in Europe saw a dramatic decline in nude art due to the rise of Christian morality. Nudity became associated with sin, shame, and the fall of man—most clearly seen in depictions of Adam and Eve.

However, the Renaissance (14th–17th centuries) revived the classical ideals. Artists like Michelangelo, Titian, and Botticelli reintroduced the nude as a symbol of humanism, beauty, and divine perfection.

Michelangelo’s David – This towering sculpture idealizes the male form while celebrating moral courage and intellectual strength.

Michelangelo’s David and Creation of Adam on the Sistine Chapel ceiling are among the most celebrated examples of religious and humanistic nudes. Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (already shown) presented the female nude not as sinful but as a goddess of beauty and love emerging from the sea.

Nudity became a means of exploring the intersection of the earthly and the divine—an embodiment of spiritual purity in physical form.

C. The Baroque and Enlightenment Eras

During the Baroque era (17th century), the nude became more sensual, dynamic, and emotionally expressive. Artists like Rubens emphasized movement and the voluptuous body.

The Three Graces – Rubens presents curvaceous, robust female nudes as ideals of fertility, harmony, and sensuality.

In the 18th century, Enlightenment ideals spurred artists to represent the nude as a subject of reason, anatomy, and moral clarity. This period saw the development of academic nudes—idealized figures posed according to strict artistic rules. These works dominated European salons and art academies.

D. The 19th Century and the Invention of Photography

The 19th century introduced both the camera and the first major shifts in the public reception of nude imagery. Photography, invented in the 1830s–40s, quickly adopted the nude as a subject—partly for artistic reasons and partly for scientific and anatomical studies.

Durieu's nude studies (collaborating with painter Delacroix) merged photography with academic realism.

In France and Britain, photographers like Eugène Durieu and later Wilhelm von Gloeden created studies of the nude that echoed classical themes. However, due to the realism of the camera, these works were also controversial—caught between being celebrated as fine art and condemned as indecent.

Victorian attitudes were complex: while the body was morally policed in public, nude photography and erotic postcards flourished in private. The camera democratized access to the nude and disrupted the gatekeeping power of elite art institutions.

E. Modernism and the Avant-Garde (1900–1950s)

The early 20th century brought dramatic innovation. Nude photography was shaped by modernist ideas—abstraction, surrealism, and psychological depth. Photographers no longer simply documented the body but began using it as a medium for experimentation.

Man Ray, Le Violon d’Ingres – A surrealist nude, blending eroticism with metaphor, suggesting the body as an instrument of art.

Edward Weston created sculptural, abstract nudes with strong light contrasts, turning bodies into landscapes. Imogen Cunningham introduced softness and emotion. Bill Brandt and André Kertész used distortion and surreal angles to explore subconscious themes.

Meanwhile, dancers and performance artists collaborated with photographers to produce kinetic nudes, emphasizing motion and temporality.

F. Postmodern and Contemporary Nude Art (1960s–Present)

The 1960s and 1970s, in the wake of civil rights, feminism, and LGBTQ+ liberation, saw nude art become intensely political. Artists used the nude to challenge authority, subvert gender roles, and reclaim agency.

Carolee Schneemann’s performance involved reading a feminist text from her body, transforming the nude into a radical political act.

Photographers like Robert Mapplethorpe, Francesca Woodman, and Cindy Sherman explored identity, sexuality, and power through self-portraiture and stark compositions. Their work sparked national debates about censorship, obscenity, and the value of nude art.

In the 21st century, artists like Spencer Tunick have brought the nude back to public spaces, organizing mass nude photo installations to comment on collective vulnerability and political control.

Zanele Muholi uses nude self-portraiture to confront issues of race, gender, and marginalization, making the body a form of activism.

With the rise of body positivity, social media, and digital manipulation, contemporary nude photography has expanded to include all body types, gender identities, and aesthetics. What was once limited to the "ideal" is now a field of diversity and reclamation.

Conclusion: A Legacy Continued

Nude art has never been static. Its meaning shifts across time and context—from fertility idol to erotic object, from divine symbol to revolutionary act. Photography, as the most modern of art forms, inherited and transformed the nude, using the lens to reflect not only bodies but ideas.

Understanding this lineage is crucial to appreciating nude photography’s cultural importance. Each image today carries with it the weight of history—from the idealized forms of antiquity to the raw, diverse, unapologetic bodies of today.

Summary Table of Key Periods in Nude Art

Period

Characteristics

Example Artist/Work

Prehistoric

Fertility, survival, spirituality

Venus of Willendorf

Classical Antiquity

Idealized beauty, philosophy

Venus de Milo, Polykleitos

Renaissance

Humanism, divine perfection

Michelangelo’s David, Birth of Venus

Enlightenment

Academic study, moral restraint

French salon paintings

19th Century

Scientific realism, erotic undertones

Durieu, von Gloeden

Modernism

Abstraction, surrealism

Man Ray, Weston, Brandt

Postmodern

Identity, gender politics

Mapplethorpe, Woodman, Schneemann

Contemporary

Diversity, activism, empowerment

Tunick, Muholi, Sherman

0 notes

Text

The Artistic Aspect of Nude Photography and Its Place in the Art Field

Introduction

Nude photography has long occupied a unique and complex position in the world of art. As both a celebration of the human form and a medium that challenges societal norms, it straddles the line between aesthetic exploration and controversy. While the nude has been a staple in painting and sculpture for centuries, photography’s relatively recent emergence as an art form has required it to assert its legitimacy, particularly when it ventures into territory traditionally associated with intimacy or taboo. This report explores the artistic dimension of nude photography, tracing its history, examining its philosophical and visual principles, and evaluating its cultural and artistic significance in contemporary society.

Historical Overview of the Nude in Art

Classical Roots

The representation of the nude in art predates photography by thousands of years. Ancient civilizations like Greece and Rome idealized the human body in sculpture and painting, associating nudity with ideals of beauty, strength, and divinity (Boardman, 1985).

Image Suggestion: Photograph of the “Doryphoros” by Polykleitos or “Venus de Milo” – Musée du Louvre.

Renaissance to Enlightenment

During the Renaissance, artists like Michelangelo, Botticelli, and Titian revitalized the classical nude, using it to convey religious and mythological themes (Clark, 1956). The human body was celebrated as a divine creation.

Image Suggestion: Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus” (Uffizi Gallery, Florence).

19th Century and the Advent of Photography

With the invention of photography in the 19th century, artists gained a new tool to capture reality. Early nude photographs by artists like Eugène Durieu (in collaboration with Delacroix) or Wilhelm von Gloeden were intended as studies for painting, though they often faced censorship (Rosenblum, 2010).

Image Suggestion: “Académie masculine” by Eugène Durieu, 1850.

The Nude in Photography: Artistic Intent vs. Voyeurism

Defining Artistic Nude Photography

Artistic nude photography is distinguished by its intent, composition, and aesthetic quality. Unlike erotic or pornographic imagery, artistic nude photography seeks to explore themes such as vulnerability, identity, strength, body positivity, and abstraction (Grundberg, 1990).

Key Elements of Artistic Nude Photography

Lighting – Light sculpting techniques used by photographers like Ruth Bernhard emphasize shadow and shape.

Image Suggestion: “In the Box – Horizontal” by Ruth Bernhard.

Composition and Pose – Thoughtful poses that echo classical sculpture help shift the viewer’s focus toward aesthetics and form.

Context – Nude figures placed in nature or architectural surroundings can evoke harmony or tension.

Image Suggestion: Spencer Tunick’s mass nude installations in natural landscapes.

Emotion and Expression – Portrait-style nudes by Sally Mann often capture a sense of raw vulnerability and psychological depth.

Image Suggestion: Sally Mann’s “Immediate Family” series (with discretion due to subject age).

Influential Artists in Nude Photography

Edward Weston

His abstract nude works, such as “Nude (Charis, Santa Monica)”, are noted for their clean lines and emphasis on natural curves (Conger, 1992).

Imogen Cunningham

Her photos such as “Triangles” challenged traditional female representations by focusing on strength and dignity (Moran, 1993).

Robert Mapplethorpe

His 1980s work explored gender and race through precisely composed, classical-style images, including his “Black Book” and “Ken Moody and Robert Sherman.”

Spencer Tunick

Tunick’s installations feature thousands of nude volunteers, emphasizing collectivity and vulnerability.

Nude Photography in Contemporary Art

Expanding Definitions

Contemporary artists like Zanele Muholi (focused on queer Black identity) and Laura Aguilar (focused on fatness and disability) challenge beauty standards and redefine the artistic nude (Cotton, 2009).

Image Suggestion: Laura Aguilar’s “Self-Portrait” series; Zanele Muholi’s “Somnyama Ngonyama” series.

Conceptual Art and the Nude

Artists such as Francesca Woodman used nudity as metaphor for transience, identity, and the ephemeral body.

Image Suggestion: Francesca Woodman’s untitled self-portraits.

Ethical Considerations in Nude Photography

Consent and Power Dynamics

Ethical guidelines emphasize consent, mutual respect, and transparency (Model Alliance, 2017). Documented agreements and trust are essential.

Censorship and Cultural Sensitivity

Artists like Nan Goldin have had exhibitions shut down or censored for exploring themes of intimacy, abuse, and nudity. Cultural attitudes often dictate what is acceptable.

The Male vs. Female Gaze

Feminist photographers such as Cindy Sherman and Ana Mendieta reframe the nude from the perspective of the subject.

Image Suggestion: Cindy Sherman’s “Untitled Film Stills” or Ana Mendieta’s “Silueta Series.”

The Nude and the Digital Age

Social Media and Visibility

Artists face censorship on platforms like Instagram due to policies that often fail to distinguish between pornography and fine art (Instagram Community Guidelines, 2023).

AI, Photoshop, and Authenticity

The debate around edited vs. natural imagery is especially relevant in body-positive movements. Photographers like Lindsay Adler emphasize transparency in editing.

NFTs and New Markets

NFT platforms like Foundation and SuperRare have become spaces for selling artistic nudes. However, concerns over commodification remain (Thompson, 2022).

Educational and Therapeutic Aspects

Body Positivity and Self-Acceptance

Photographers like Jade Beall document postpartum bodies to celebrate authenticity and body love.

Image Suggestion: Jade Beall’s “The Bodies of Mothers” project.

Art Therapy and Personal Empowerment

Nude photography has been used in therapeutic environments to support healing from eating disorders, trauma, or dysmorphia (Malchiodi, 2007).

Nude Photography in Galleries and Museums

Legitimacy in the Art World

Institutions like MoMA and the Getty exhibit nude photography as fine art. In 2023, the V&A held “Nude: Art from the Tate Collection,” which included both photographs and classical works.

Controversy and Curation

Curators must weigh artistic intent against public sensibilities, especially with minors or sensitive content (Merritt, 2020).

Conclusion

Nude photography is a powerful, multifaceted form of artistic expression that continues to evolve. Its roots in classical art provide it with a deep historical foundation, while its modern iterations reflect ongoing cultural shifts and technological innovation. Despite ongoing debates over ethics, censorship, and interpretation, nude photography holds a legitimate and meaningful place in the art field.

Far from being merely provocative, the artistic nude can inspire, empower, and challenge viewers to reconsider their relationship with the body, identity, and beauty. Like all great art, it invites contemplation—and sometimes discomfort—but always with the potential to deepen our understanding of what it means to be human.

Bibliography

Boardman, J. (1985). Greek Art. Thames & Hudson.

Clark, K. (1956). The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. Princeton University Press.

Conger, A. (1992). Edward Weston: Photographs. Aperture.

Cotton, C. (2009). The Photograph as Contemporary Art. Thames & Hudson.

Grundberg, A. (1990). Crisis of the Real: Writings on Photography. Aperture.

Malchiodi, C. (2007). The Art Therapy Sourcebook. McGraw Hill.

Merritt, R. (2020). “Curation, Consent, and Controversy.” Museum Ethics Quarterly, Vol. 12.

Moran, M. (1993). Imogen Cunningham: On the Body. University of Washington Press.

Rosenblum, N. (2010). A World History of Photography. Abbeville Press.

Thompson, J. (2022). “NFTs and the Nude.” Artforum, May 2022.

Instagram Community Guidelines (2023). Meta Platforms.

Model Alliance (2017). “Ethical Practices in Artistic Modeling.”

0 notes

Text

The Nude in Photography: A Cultural, Historical, and Artistic Exploration

I. Introduction

The human body has always been at the heart of artistic expression. From prehistoric carvings and classical marble sculptures to Renaissance paintings and avant-garde photography, the nude figure has stood as a powerful symbol of beauty, vulnerability, and humanity. In photography—a medium that combines realism with artistic vision—the depiction of the nude form is one of the most intimate and enduring subjects an artist can explore. Venus of Willendorf – One of the earliest known representations of the nude form, this Paleolithic figurine represents fertility, femininity, and early human artistic expression. It shows that even in prehistory, the nude was deeply symbolic.

Nude photography, when approached ethically and artistically, transcends simple documentation. It is an act of expression, introspection, and often vulnerability—for both the photographer and the subject. In contrast to the often artificial portrayals of bodies in commercial media, nude photography allows for a truthful, nuanced representation of the human form.

Edward Weston, Nude, 1925 – Weston's work revolutionized nude photography with its sculptural, abstract approach. His use of light and shadow emphasized form over eroticism, redefining what nude photography could be.

Today, amid a digital culture saturated with manipulated images, the authentic visual language of nude photography reasserts its importance. Photographers use the nude not only to express aesthetic beauty but also to challenge social norms, explore identity, and create emotionally charged narratives. Spencer Tunick, Munich Installation, 2011 – Known for organizing large-scale nude installations in public spaces, Tunick explores themes of anonymity, vulnerability, and the collective human body.

The genre’s roots go back to centuries of nude art in painting and sculpture. From Greek statues idealizing male form to Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus,” the nude has long served as a vehicle for mythology, philosophy, and spiritual exploration. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus – A pivotal example of the classical nude in Renaissance art. Botticelli’s Venus embodies grace, myth, and idealized beauty—elements photography would later adapt.

This report will explore the complex, layered world of nude photography through historical, cultural, and technical perspectives. It will trace the evolution from early artistic nudes to experimental and contemporary photographic practices. It will cover the ethics and emotional dynamics involved in working with nude models, and detail the methods photographers use—lighting, composition, setting, and pose—to craft meaningful images.

It will also argue for the relevance of nude photography today: not just as a form of art, but as a statement of inclusivity, identity, and empowerment.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Self-Portrait, 1980 – Mapplethorpe challenged both aesthetic norms and social taboos with stark, stylized nude imagery, often exploring gender, race, and sexuality. His work is controversial, but historically vital.

More than mere nudity, these photographs communicate vulnerability, confidence, eroticism, abstraction, or defiance. A well-composed nude photograph can mirror classical sculpture, draw from surrealist dreams, or offer raw emotional honesty. Imogen Cunningham, Nude, 1920s – A key female pioneer in photography, Cunningham emphasized organic curves and natural lighting, giving the nude a subtle, almost botanical elegance.

As we’ll explore in coming chapters, photography inherited—and then reinterpreted—visual codes from painting, sculpture, and performance. But in doing so, it created its own language, rooted in realism, immediacy, and intimacy.

Image Summary in Context

ImageArtistPurpose in ContextVenus of WillendorfUnknown (Prehistoric)Demonstrates how the nude form has symbolized fertility and power since prehistory.Birth of VenusBotticelliA classical Renaissance representation of idealized feminine beauty.Nude (1925)Edward WestonIntroduces abstract and sculptural modernist nude photography.Installation, MunichSpencer TunickShows modern collective nude art in public space—nude as political and social statement.Self-Portrait (1980)Robert MapplethorpeDemonstrates the intersection of nudity, identity, and social provocation.Nude (1920s)Imogen CunninghamShows a softer, naturalistic approach to photographing the nude form.

0 notes

Text

Diana and Endymion by Jérôme-Martin Langlois (1822)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

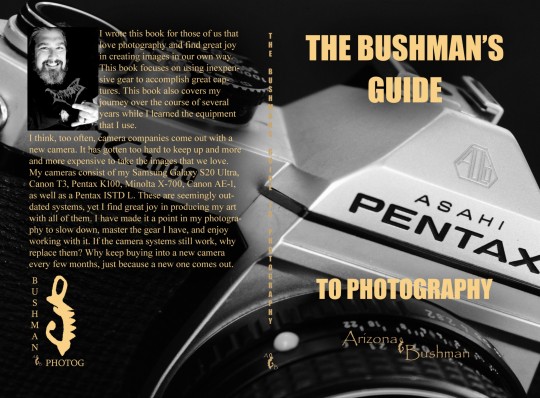

Been a little busy recently. I have finished up my 5th book and it will be available soon.

1 note

·

View note

Text

After several years, I decided to watch the movie Blue Velvet again. I watched it the first time because one of my favorite bands, Benediction, recommended it in the lyric sheet of their EP album, Dark is the Season. The title track is heavily inspired by the movie. It has literally taken me 21 years to realize that Blue Velvet could be mistaken for a Twin Peaks prequel. In my opinion, it is Twin Peaks...cannot convince me otherwise.

On a side note, Dark is the Season is one of my absolute favorite album covers. Immolation Dawn of Possession is second to that.

0 notes