I’m not buying any new books until I reread all the ones in my bookshelves! I’ve got a nice library that’s very eclectic, so it should be a fun little challenge I’ve set for myself. I estimate a new review once a week. I’m a fast reader, but many of these are 500+ pages!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

MARJORIE MORNINGSTAR

By Herman Wouk

©️1955; 565 pgs; Doubleday

I first read this book after experiencing my very first heartbreak. I was 18, and the eponymous heroine in this novel was 17 going on 18, so I felt that I understood her. In the den/family room of my childhood home, one entire wall was bookshelves, floor-to-ceiling, without any room to spare. Sometimes, I would investigate that library if I was bored or had run out of new reading material. Most of it was classics, with a big helping of history, biography, and World War II nonfiction. But this title was so out of place among the Churchill, MacArthur, and Eisenhower biographies, I couldn’t help but investigate further. I’m forever glad I did. I didn’t know who Herman Wouk was at the time, but in the early 1980s I would read both The Winds of War and War and Remembrance, and I would avidly watch the miniseries made from the former. My aunt Ruth was the acquisitions director for the wall of books, since nobody else in the family ever read any books for fun except herself. And me. I’m pretty sure her membership in Book of the Month Club is how she ended up with this one, as it’s a coming of age story and a romance. Aunt Ruth didn’t do either of those.

Marjorie Morgenstern is 17, lives with her parents and brother in a swanky Manhattan upper east side apartment on Park Avenue, and attends Hunter College where she is a sophomore. I was in college at 17, although a year behind Marjorie, who skipped a grade and started school earlier than other children due to her precocity. I was acutely aware, both now and back in 1977, that this book was published in 1955, but somehow, I forgot the fact that it takes place in 1933 through 1939, with the last chapter jumping ahead to 1954. My mother was born eight days after the opening of the story, when Marjorie is innocent, carefree, dating a wide pool of suitors, and becoming interested in the theater. She decides in the first few pages that she is going to be an actress, and she dreams of a name less ordinary and more memorable than “Morgenstern.” She tries “Morningstar,” and she likes it. That, then, is who she will become:

Marjorie is a smash success in Hunter College’s production of The Mikado. She meets and befriends a fellow student whose Bohemian clothes and vivacious manner draw her in instantly. Marsha Zelenko is the costume designer for Hunter College’s drama department, and she and Marjorie become close friends. Marsha tells Marjorie of a summer job opportunity at Camp Tamarack, a camp for kids. Marsha will be a counselor for the summer, and there is an opening for one more. The chief attraction of this job is the fact that opposite Camp Tamarack, on the same lake, is South Wind, an infamous resort for adults only. All kinds of debauchery is reputed to go on at South Wind. The staff of Camp Tamarack isn’t allowed to leave camp grounds upon risk of termination, but Marsha convinces Marjorie to wait until lights out, then accompany her in a rowboat and sneak over to South Wind. Marsha knows everybody there. The resort puts on musical theater shows every night, written and directed by their musical director and shining star, Noel Airman. He’s had two hit songs already, by age 28, that everyone knows. Noel is tall, lean, and blond, very handsome, very talented, and nine years older than Marjorie. He’s singing and playing piano for a group of South Wind staff when Marjorie first lays eyes on him, and she is in love before he’s finished the song.

Marjorie becomes a volunteer at South Wind the next summer, against her parents’ wishes. This is when her relationship with Noel deepens into reciprocated love with a huge dose of passion, but absolutely no sex. She builds sets, sews costumes, dances in the chorus, and “necks” with Noel. This summer ends very dramatically with the death of Marjorie’s beloved uncle. Marjorie’s mother arranged for the Uncle (as he is referred to by everyone in the family) to be hired as a dishwasher in the South Wind kitchens so he can keep an eye on Marjorie’s virtue. The Uncle dies of a heart attack very suddenly, and Marjorie leaves with his hearse. The shine is permanently gone from South Wind afterwards.

There are many different subplots concerning Marjorie’s Jewish extended family and one or two concerning some of her dates. But the book is primarily interested in exploring Marjorie’s and Noel’s commonalities, differences, and attraction to each other. Noel Airman’s real name is Saul Ehrmann, and it turns out that Marjorie’s parents know his parents, which is a connection Marjorie never anticipated. In fact, Marjorie dated Noel’s younger brother Billy, who always seemed clownish and silly to her. But despite Noel being from a good Jewish family, the Morgensterns never totally warm to the prospect of their daughter ending up married to him. He’s a songwriter, which isn’t steady, reliable work. He’s slept with half of New York, or so people say. He’s louche, slippery, untrustworthy. Noel IS all of these things, plus later in the book we learn he is a borderline alcoholic with episodes of mania, never specifically stated as such but definitely what Wouk is describing. Noel is in love with Marjorie, has been since the summer at South Wind, and he tries to mold himself into what he thinks she wants him to be. He takes jobs—high paying jobs, the kind the Morgensterns would respect—does well for about two weeks, then walks out and never returns. He is faithful to Marjorie, even though he knows there is no way she’s giving her virginity to him without marriage. And Noel isn’t the marrying kind.

Eventually Marjorie sleeps with Noel. It was inevitable, given their attraction to and love for each other. What’s glaringly out of place in 2022 are the admonishments Wouk gives the reader for anyone having sex out of wedlock. He describes Marjorie as feeling tarnished afterwards; very much “less-than.” Of course, in the 1930s (and the 1950s for that matter), a woman who chooses to sleep with a man she’s not married to is regarded by polite society as a “roundheels” (slut) and is to be pitied and avoided. He also takes the opportunity to scold us again at the end of the book, which I’ll get to later.

Noel has an image in his head of a certain type of young Jewish girl whose only goal in life is to marry and produce children. He calls this unflattering composite girl “Shirley.” In the beginning of their relationship, he teased Marjorie relentlessly about her inner Shirley, and how, despite all her attempts to behave unconventionally and become a theater actress, he is sure she will eventually return to being a Shirley. Marjorie seethes at the comparison. She is going to BE SOMEBODY, and being that somebody doesn’t include a husband or babies. Noel good-naturedly stops teasing her about it, but he believes she is one, no matter what she may believe to be true about herself.

After a few years of being in a semi-monogamous relationship, circumstances intervene by way of Noel’s fear of commitment and general rootlessness, and he writes Marjorie a 22-page letter breaking up with her for good. In this letter, he tells her that over the years of their romance, she proved herself to be, thoroughly and completely, a Shirley. He tells her he is sailing to Paris and starting over there by gaining inspiration from the beauty of Europe. Maybe he’ll write another hit song, or maybe he’ll write another musical for the stage (he had one produced on Broadway that was excoriated by theater critics and closed within a week, but there is always the chance he can do it again and get it right this time). Marjorie is broken by the letter and the fact of Noel’s leaving, and she tells her father she will take a job at his business doing secretarial work, which is applauded by both of her parents as an excellent practical first step towards independence. But Marjorie saves her wages for something else. She’s calculated that she needs $700 to sail round trip to Paris, and she works very hard and spends no money, and at last, she is on board the Queen Mary to France to find Noel and get him back.

On board, she meets an enigmatic, brilliant stranger named Mike, who actually knows Noel. He had no idea Noel was in Europe, but he pledges to try to help Marjorie find him. Mike and Marjorie have a shipboard romance that’s not serious and involves no sex beyond kissing, but Marjorie is drawn to him in a different way than she’s drawn to Noel. Mike says he’s in chemicals, but the evidence of this lies only in his possession and consumption of many different types of pills. He gives Marjorie pills, too, ostensibly for seasickness. From the description of how Marjorie feels once the pills take effect, it seems like they were tranquilizers. Mike has some type of secret undercover job, which Marjorie eventually learns is pulling Jewish families out of Germany and getting them to France. He is heroic, brave, and possibly a drug addict.

Thanks to Mike’s network of acquaintances, Marjorie finds Noel in Paris, they spend an evening reconnecting, and Noel finally does the thing Marjorie has been praying for since she first met him that long-ago night at South Wind: he proposes marriage. It’s been a long time, and much has happened to Marjorie to allow her to mature and accumulate wisdom about men and women and love and expectations, and so she declines the proposal. That done, the relationship finally ends in Marjorie’s heart. She returns to New York, and in short order meets, falls in love, becomes engaged, and marries a nice Jewish doctor whose name is never mentioned. Here is where Wouk again shows his obsolescence regarding sex without marriage: it’s an ordeal for Marjorie to tell her fiancé that she’s not a virgin. AN ORDEAL. Firstly, I really bristled at the fact that she NEEDED to confess this fact at all, and even more when her fiancé is so shaken by this revelation, he takes days to decide whether or not he will still marry her (!), and when he decides that yes, he loves her regardless and will marry her despite this one glaring flaw, I had to repeatedly remind myself of the 1930s attitudes towards physical affairs. I might’ve thrown this book through the window otherwise.

Still, for all the author’s personal opinions, I love this book. I love the descriptions of Manhattan society, post Prohibition repeal. I loved the world building of South Wind (Marjorie’s mother always referred to it as “Sodom,” and indeed, Part 2 of the book is set in South Wind, and it’s titled “Sodom.”) I loved sailing to Europe on the Queen Mary, and I loved being in Paris in 1939, when Hitler was on the move and darkness was descending on the world. I enjoyed the Jewishness of the family and the explanations of their customs and rituals, particularly the Morgensterns’ Seder. And most of all, I loved Marjorie. I could relate to her romantic highs and lows, and it was immensely gratifying when she was able to stop loving Noel. He brought her so much pain in an otherwise comfortable life. I was going through the same thing, trying to fall out of love with a boy I knew would ruin my life if I let him.

1 note

·

View note

Text

STATION ELEVEN

By Emily St. John Mandel

©️2014; 334 pgs; Alfred A. Knopf

I stood looking over my damaged home and tried to forget the sweetness of life on Earth. — Dr. Eleven, Station Eleven

I’m straying from the physical bookshelf to report on my favorite novel of the 2010’s that was recently adapted into a ten-episode HBOMax miniseries. I LOVED this book when I read it upon publication, and I loved the miniseries too. I had forgotten the particulars of the novel, and so I was able to watch the series without any cognitive dissonance. The overarching plot was the same, the characters were familiar to me, and the basic outline of what happens and to whom remained mostly the same. Now that the series concluded last week, and I have re-read my Kindle copy from eight years ago, I honestly couldn’t choose which one I enjoyed the most. I do know that as I read this time, I pictured the actors from the series as each character in my head, which to me means that the casting was 100% successful.

Everyone who has HBOMax should watch this series. There are so many thought experiments contained in this story: creating your identity from the ashes of a burnt civilization, how we process trauma and grief, whether or not good and evil can coexist more or less peacably. There is a Before, and there is an After. Nobody who is alive at the end of the 99%-fatal flu pandemic that’s the cornerstone of this book is the same person they were before. Nobody but a very few remember the ubiquitous technological aids we used without thinking, or airplanes flying in the sky, or electricity. It’s a medieval world, the After, and survivors repurpose found objects in new and surprising ways.

I’m not going to go into detail about the plot. Many people found the series too difficult to watch, given that we are still in the midst of a global pandemic that has killed 800,000 Americans in just under two years. This is a dystopian post-apocalyptic story, and the apocalyptic event is an extraordinarily lethal form of influenza. NINETY-NINE PERCENT FATAL. What do the survivors do? Where do they go? What horrors do they see?

The opening is set in Chicago, and the main character, Kirsten Raymonde, is eight years old. Kirsten is our avatar in the post-flu world. The people who survive are apparently immune, although some are lucky enough to have found shelter from the outside world of death and chaos, like Jeevan Chaudhury, who holes up with his brother Frank in Frank’s high-rise condo on the lake for a few months. It’s likely the virus burned itself out while he was sheltering, or maybe he was immune all along. Jeevan and Kirsten spend about thirty minutes total together in the book, but in the series, they spend much more time together, get separated, then meet again after 20 years have passed. It’s emotionally satisfying in the best possible way, but the novel is more interested in people’s individual struggles to survive the aftermath of the collapse. Not everyone is connected to everyone else in the novel, and those who are connected don’t even realize it. It’s kind of like real life in that regard.

There is violence, but it’s always defensive. The series went with more visceral violence perpetrated by the villainous antagonist because of a set of beliefs this character adhered to, but it didn’t detract from the love and humanity that are the emotional basis for the story. Found families try to stay together, and they mostly succeed. People do unexpected things out of love and basic decency. The book concentrates on these positive indicators of rebirth and renewal. You may have lost your entire family to the flu, but if you’re lucky, you find other survivors who also share the common goal of creating a new normal in which to be safe and hopefully, to thrive.

Station Eleven is a graphic novel about a physicist, Dr. Eleven, living on a space station called Station Eleven 1000 years in the future. His station has been thrown into chaos, and he is longing for his home while trying to survive the attacks from the Undersea, a collection of hostile people living in a network of fallout shelters beneath Station Eleven’s oceans. How Kirsten comes into possession of one of the only two copies in existence, what it means to her, and how it connects her to other characters she will meet in Year Twenty is a remarkable story. (The world is counting years since the “collapse,” as the flu event is referred to, and this story is mainly set in Year Twenty with flashbacks to the Before.) So Kirsten is 28 in the “now,” but we flash back to her eight-year-old self and to other characters in the Before who didn’t survive the collapse, but whose actions reverberate for the next twenty years.

Read this book. Or watch the series and then read this book. This story is transcendent, beautiful, and unforgettable either way, but this novel is exceptional.

0 notes

Text

AMONG THE DEAD

By Michael Tolkin

©️1993; 274 pgs; Wm Morrow & Co

I’m using a photo of the exact cover I used to have on the hardback I just re-read instead of my usual photo of my copy. At some point in the late 90’s or early 00’s, I read that if you had a lot of books, you should remove all their covers because the solid colors and metallic titles on the spines would be an aesthetically pleasing DECORATING CHOICE. A few escaped, but not many. Anyway, my copy is battered, there are actual coffee cup stains on the front, and this photo has the cover I remember so vividly. That cover is a perfect graphic representation of what awaits the reader inside. Jagged, discordant, yelling text on monochromatic bands of sad neutral colors.

I was very fond of this one. I probably read it three or four times, I’m guessing. It’s so jarring to realize that since 2009, when I got a Nook (remember those? Are they still a thing?), I haven’t read actual print books nearly as often as digital versions. Age, limited space, and eyesight make digital books much easier for me. I’ve had an iPad since 2010, and in my Kindle app, I’ve got 430-odd books. This blog is basically me revisiting my reading past, and so it happened that the next book in line was this plain black coverless book, so innocuous on my shelves. You’d never suspect what its pages hold. I’m glad it’s over, but I quite enjoyed the ride. It’s an immersive plunge into a very specific kind of personal hell, which will never happen to me, so it’s safe to explore through fiction. It’s why we ride rollercoasters—they’re like rehearsals for death.

Frank Gale is married to Anna. They have a three-year-old daughter, Madeleine. Frank has been having an affair with a woman who works in his business’s insurance office. Her name is Mary Sifka, and she is married as well. Frank has decided to end the affair, confess everything to Anna, beg for forgiveness, and rebuild their marriage. He doesn’t want to do this in L.A., where they live—he has booked a 10-day vacation in Acapulco for himself, Anna, and Madeleine. He won’t confess the affair until they’re in their suite at the resort. This will force Anna to stay with him for another nine days and give him uninterrupted time to manipulate her into forgiving him. He thinks up a brilliant idea: he’ll write her a LETTER of confession, then on their second day in Mexico (he wants to let her have one day of fun, and he considers himself generous to have thought of this), he will give her the letter, take Madeleine for a walk on the beach, and let her have her emotions in private (he hopes the worst will have subsided by the time he returns because he is a coward.)

The night before they leave, he writes the letter and tucks it into his suitcase. It says

“I love you. You asked me a few weeks ago why I was so desperate to take this vacation and I said I needed to get away from the office for a while, and that’s true, but there’s more. For six months you’ve noticed that I’ve been distant, and I have been. You asked me if there was another woman, and I said no, but I was lying. I had an affair with Mary Sifka. It’s over now. I wanted to take this trip so that we could find a way to heal ourselves. I don’t know how you’ll take this, and all I can say is that I beg you to forgive me, but if you don’t want to, I’ll understand. I love you.”

Frank doesn’t go with his family to the airport. He has to meet Mary Sifka for lunch and actually end the affair (he wasn’t technically lying to Anna in the letter—he said it was over and it was; he just hadn’t told Mary yet). Their flight isn’t until 3:00pm, so he has time…except he drinks a little more than he should (for courage), and the lunch lasts longer than he’d planned. Mary took it well, and this pleases Frank. But he’s running late now, his cab is slow, traffic is awful, and he knows he’s going to miss the flight. At least Anna has his luggage so he can just take the next flight out, but he needs to let her know. He has the cab stop at a pay phone (the 90’s!) where he finally reaches Anna on the courtesy phone at the gate. The plane is boarding. Anna is furious. Frank has never heard her this cold with this hard edge in her voice. “I read the letter,” she tells him, having had to pack some of Madeleine’s toys in his suitcase, whereupon she discovered it. Frank is a raw nerve in a suit by now. He gets her to say she won’t do anything—anything at all—until he gets to Mexico so they can deal with the information together.

Frank’s at the gate waiting for the next flight to Acapulco when the news comes in that the plane Anna and Madeleine and nearly 200 other people were on has crashed just south of San Diego, in a residential neighborhood, taking out two blocks. His wife and toddler daughter are dead, and Frank immediately begins to spiral—not from grief. His brother and parents, who also live in L.A., come to the airport. Families of the dead begin congregating, the airline dispatches its crisis workers and P.R. machines, and the news media go into overdrive. Over the next week, he will experience an episode of hysterical deafness, his bowels will evacuate without his permission—only in front of his parents, so it could’ve been worse—and an open, ongoing display of such truly bizarre behavior that everyone chalks up to his deep grief. Only Frank doesn’t feel much of what we commonly recognize as grief. Frank doesn’t FEEL much of anything except the obsessive need to go to the crash site and look around for the bodies of his wife and child. Maybe he’ll find their suitcases. Will they be hanging in a tree? He’s heard the first responders found a bunch of bodies from the plane like that. He wonders what it feels like to fall at 32 feet per second per second from 30,000 feet, or did the plane explode in mid-air and the altitude killed them before they could fall?

Of course, his written confession to Anna is found by rescuers helping survivors on the ground. This wouldn’t have necessarily been a bad thing, but Frank had named his mistress very specifically, and that name, Mary Sifka, was not only uncommon, she had her own listing in the L.A. phone book. At first, her name is redacted as the mayor of San Diego reads Frank’s letter aloud at the official memorial service. It is considered to be a miracle that this letter was found, but it was unsigned and not addressed to anyone specifically, leaving the public to speculate about who wrote it (the poor bastard is dead now, along with whomever he wrote to), and to discuss how to find out the name of the lover. Frank’s letter is printed on the front page of newspapers everywhere, and when reporters uncover Mary Sifka’s name, address, and phone number, Frank’s entire family knows he’s the letter writer.

“How did Frank feel? This is how he felt: tie a man’s wrists to two posts. Nail his feet to the floor. Take a razor blade or a scalpel, and cut the skin in a circle around his neck. Then, from his neck down to his waist, cut a series of strips, an inch apart. Then pull each strip away from the body, and let them fall, making a loose skirt of flesh. Then throw boiling ammonia on this swamp of blood. Wait three minutes for the blisters to rise. Rub them with hard salt. This should overload the myelin sheaths that protect the nerves from agony.”

The whole novel is told from Frank’s point of view, and it includes all his thoughts, ideas, feelings, and perceptions. Frank isn’t an exceptional man. He’s maybe Everyman, full of inadequacy and doubt, just trying to survive this tragic event. But the event he’s working so hard to survive isn’t the loss of his wife and daughter. He’s trying to survive the discovery, dissemination, and publication of the letter, and through it the knowledge of his infidelity. Frank cares what people think. He especially cares what his parents and brother think. He cares what Anna’s parents think of him now that his secret has been exposed. He’s so preoccupied by his imagination supplying him with all the death scenarios he’s imagined for Anna and Madeleine that he acts without thinking. Later he’s so preoccupied by THE LETTER and how long it will take for the media to discover Mary’s name that he makes some Very Bad Decisions. It can be wildly funny, but make no mistake—this is dark. I’d call it a black comedy, except I can’t really use the term “comedy” when a plane crash with no survivors is a key plot point.

Michael Tolkin also wrote “The Player,” which was turned into a movie starring Tim Robbins. I think I’d like to read that one, although I know it would be dated. I enjoyed this unusual, well-written novel of worst-case scenarios, and I recommend it to readers who love exploring the dark side of human nature.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

AMY AND ISABELLE

By Elizabeth Strout

©️1998; 304 pgs; Random House

I have so many feelings about this re-read. Amy and Isabelle are daughter and mother, I’m the mother of a daughter, my daughter is herself the mother of a daughter…So. Many. Feelings. I finished it this morning, but I’m going to think about it for a while before writing up a book report. I first read this in Palm Beach when Miranda and I were there for my sister’s wedding, when Miranda was sixteen. I remember LOVING it, recommending it to Miranda, and I think I even loaned it to her. How I didn’t lose my goddamned mind after reading this then is a mystery because it’s terrifying. Women can be terrifying. Very young women, especially. I guess I considered myself immune somehow to the darkness of this story because I thought of Miranda’s and my relationship as being close, loving, and SO much healthier than the one depicted here. I don’t know. Strout is a beautiful writer, I do remember that, and it was perhaps even more beautiful to me now that I’m a grandmother. Maybe age fosters appreciation? Beautiful prose.

The story is told alternately from either Amy’s or Isabelle’s point of view in the third person, so the reader isn’t always aware of some events told from only one perspective. This time around, I noticed that in the first half of the book, the majority is from Amy’s POV, but this gradually shifts so that in the second half, Isabelle’s POV is featured more and more. She is ultimately the far more interesting character.

Amy Goodrow is fifteen in this book, which unfolds over one unusually hot, dry summer. The fictional town of Shirley Falls, somewhere in New England, is where Amy and her mother, Isabelle Goodrow, have lived for all fifteen years of Amy’s life. Amy never knew her father, as he died when she was a baby. She’s a typical teenager in many respects—her naïveté, her lack of self-esteem, her trouble making friends in her high school. She’s not so typical in others—Amy is beautiful but doesn’t know it. She’s exceptionally smart. She is an avid reader. She’s tall, long-limbed, big-breasted, and she has a glorious head of long, curly, blonde hair that everyone says is her best feature. Amy uses her hair primarily as a shield, ducking her head and letting it fall over her face. She hides behind its thick curtain whenever she feels too exposed, which is frequently. She dutifully attends church with her mother every Sunday. Her one friend, Stacy, who normally hangs out with the popular kids, goes to lunch with Amy every day, and every day, they leave the school grounds and go into the edge of the woods, where they hide, gossip, and smoke cigarettes.

Isabelle Goodrow is Amy’s mother. She’s an executive secretary at the mill, the largest employer in town. She has arranged for Amy to work as a clerk in the mill office for the summer, or at least until Dottie returns from her medical leave. The kind of mill is never specified and hardly matters. It does matter that her coworkers are the only women Isabelle sees regularly, except for the women at her church. Isabelle feels slighted by these church ladies because they are married while Isabelle is not. They live in homes they own while Isabelle rents. They sometimes talk of their trips to Boston to shop. Isabelle can’t even imagine herself having the money or the free time to do this, and anyway, she is never asked. She is extremely aware of these differences between herself and the other women of the town who are roughly her age, and her chronic feelings of inadequacy overwhelm her. She “keeps to herself.” But the women she works with are, in her view, low class. Beneath her. She has worked at the mill for Amy’s entire life.

Amy and Isabelle have always lived together, by themselves. Isabelle hasn’t had a relationship with a man in Amy’s lifetime, and she is a very strict mother who tries to control every aspect of her daughter’s life. I think all mothers do this to an extent, but as the child grows and matures, your need to control lessens. Isabelle either hasn’t reached this point or is unaware it’s coming, but Amy is fifteen. The tensions between mother and teenage daughter have escalated by the start of the summer and are gloriously explored in this book:

“‘Use your napkin, please.’ She couldn’t help it: the sight of Amy licking ketchup from her fingers made her almost insane. Just like that, anger reared its ready head and filled Isabelle’s voice with coldness. Only there might have been more than coldness, to be honest. To be really honest, you might say there had been the edge of hatred in her voice. And now Isabelle hated herself as well.”

I think the everyday “hatred” Isabelle feels at this dinner of hamburger patties and canned beets isn’t so much hatred as it is fear. Isabelle lives in a constant state of fear. Fear of failing Amy, fear of losing Amy, and fear of Amy’s emerging womanhood. This seems related to Isabelle’s aversion to adult women in general: will Amy turn out like the women at the mill—uneducated and ignorant? Will she leave Isabelle without warning, maybe run away? Will she turn out like the women from church: thinking she’s better than Isabelle? Or, worst of all—will she turn out like Isabelle herself? We learn that something awful happened between the two on the first weekend after school let out for the summer, and that is the catalyst for all the current misery.

Amy’s substitute teacher for the winter/spring term in English is Mr. Robertson. He’s short, bearded, young, and interested in Amy. They begin meeting in his classroom after school, reading poetry and talking about literature, but progress to taking drives in Mr. Robertson’s car, long drives which end with parking on an old logging road at the edge of the woods. He’s a little more than twice Amy’s age. They never have actual intercourse, but they do engage in a variety of sexual activities. Amy is in love. She believes Mr. Robertson loves her too. Doesn’t he always say she’s his best and brightest student? Doesn’t he loan her books of poetry with special phrases underlined just for her?

Isabelle discovers the affair when her boss, Avery Clark, happens to notice a flash of steel glinting in the hot sun at the edge of the woods. Thinking it was someone whose car had broken down, he investigates further and sees his secretary’s teenage daughter, naked with a bearded man, in the back seat of a car. Being a man of discretion, he reports what he saw to Isabelle privately. He won’t tell a soul. Isabelle rushes home in panic. She and Amy proceed to have a terrible fight, during which Isabelle alternates between outright interrogation and withering condescension. Amy is vague, refuses to meet her mother’s eyes, and defends Mr. Robertson’s honor the only way she knows how: by insulting Isabelle:

“‘You don’t know what the world is like,’ Isabelle told the girl gently, almost crying herself, leaning forward slightly in the green upholstered chair.

‘No!’

Amy spoke suddenly, loudly, turning her wet face to her mother. ‘YOU don’t know what the world is like! You never go anywhere or talk to anyone! You don’t read anything…’ Here she seemed to weaken momentarily, but moving a hand sideways through the air as though propelling herself forward, she continued. ‘Except for the stupid Reader’s Digest.’

It changed everything, her saying that. For Isabelle, it changed everything. Remembering it weeks later, in the soft darkness of night, it brought to her the exact intensity of silver pain rippling through her chest that it had delivered at the time it was spoken; without moving, she seemed to stagger, her heart racing at a ridiculous pace.”

After the confrontation, Amy and Isabelle don’t speak unless it’s absolutely necessary. Each harbors a vast emptiness inside. For Isabelle, the empty feeling comes whenever she lets herself ruminate on what a bad job she did raising Amy—if the girl would so easily give herself to a man who could never return her affection…! For Amy, it’s self-preservation: she can’t think of it. Mr. Robertson hasn’t contacted her since Isabelle found out, her heart is broken, and she is consumed with thoughts of the love between them, so unbreakable and yet so fragile.

Each is resentful, hostile, and silent, nursing their separate grudges. The silence lasts all weekend. On Sunday, Isabelle erupts and calls information, gets Mr. Robertson’s address, and goes to see him. She tells him she knows about him and Amy, she could call the police and have him arrested for statutory rape, she could call the school superintendent and make sure he never gets another teaching job as long as he lives. He is impassive, polite, and tells her he’ll be gone by tomorrow. School is out, it was a temporary job anyway, and he doesn’t want any trouble. As she drives home from Mr. Robertson’s apartment, her emotions percolate and multiply:

“What she felt, turning into the driveway, was a fury and a pain so deep that she would never have believed a person could feel it and still remain alive. Walking up the porch steps, she wondered seriously, briefly, if in fact she would die, right here, right now, opening the kitchen door. Perhaps dying was like this, those final moments of being rushed along by some powerful wave, so that at the very end one did not actually care, there was no reason to care: it was just over, the end was there.”

Isabelle takes her fury and pain out on Amy the only way she can think of: she takes a pair of scissors and chops all of Amy’s beautiful, long, curly hair off—right at ear-level. Amy starts her summer job at the mill the next day, ashamed of her shorn hair, uneven and exposing her face. She doesn’t believe her mother yet that Mr. Robertson has moved away and will never be back. As the long, hot days at the office drag on (there is no air conditioning), mother and daughter, avoiding each other at home, avoid each other at work. They are both watchful; quiet. Amy watches her mother sometimes from across the expanse of the office floor, and despite all that has happened between them, notices things about Isabelle she never could’ve recognized before:

“He might have spoken her mother’s name, because Isabelle stopped in his door; Amy, glancing up again, saw the submissive hopefulness that lit her mother’s pale face, and then saw it disappear. A hole opened in Amy’s stomach: it was terrible what she had just seen, the nakedness of her mother’s face. She loved her. On the black line connecting them a furious ball of love flashed across to her mother, but her mother had returned to her desk now, was rolling a sheet of paper into the typewriter. And immediately Amy felt that loathing at her mother’s awkward, long neck, the wisps of moist hair stuck to it. But this loathing also seemed to increase some desperate love, and the black line trembled with the weight of it.”

Mr. Robertson makes good on his promise to leave town, and when Amy uses a pay phone to call him, his number is disconnected. She goes to the empty school and learns from a friendly janitor that he left permanently, probably for Boston…didn’t he always talk about wanting to teach there? Of course, she is completely shattered by the fact of his absence and the dawning realization that her mother was right about him, about them, and that he hadn’t loved her at all.

Over the summer, the heat is oppressive. The river dries up. Vegetables wither. Isabelle treats Amy as though she, and the whole situation with Mr. Robertson, were an alien event, unconnected to herself, surpassing even her private fears—the worst has happened. Now it’s even hard to look at Amy, much less live in the same two-bedroom house with her. Just watching Amy walking across the yard to the front door now causes intense storms of emotion within Isabelle:

“The anger arrived in one quick thrust. It was the sight of her daughter’s body that angered her. It was not the girl’s unpleasantness, or even the fact that she had been lying to Isabelle for so many months, nor did Isabelle hate Amy for having taken up all the space in Isabelle’s life. She hated Amy because the girl had been enjoying the sexual favors of a man, while she herself had not.”

Mother and daughter finally reach an uneasy kind of peace, but only once the weather turns cooler with the promise of fall. Isabelle finds herself responding to her coworkers’ various crises in ways she never would have dreamed before that summer. She had always thought of herself as far too busy with Amy to cultivate any outside relationships. She becomes caught up in these women’s lives and their need for friendship when one of them reaches out in a moment of crisis. Dottie—who’s had a recent hysterectomy—has suffered a blow. Her husband of 28 years has up and left her for another woman. Isabelle impulsively invites Dottie, plus Dottie’s best friend Bev, to spend the night in her home. She has never even considered doing this before. The three women stay up consoling Dottie and sharing confidences. In particular, Isabelle shares her best-kept secret with these two women, and afterwards, she finds she has undergone a change in how she thinks of not just Dottie and Bev, but also in how she sees herself. She is not better than these women! She is just like they are—doing the best she can in trying circumstances. The camaraderie—the friendship—alters her view about Amy and Mr. Robertson too. It was unfortunate, yes, and he was a predator, no doubt about it. But at least he hadn’t taken her virginity, so there was no possibility of pregnancy—something Isabelle knows about from personal, devastating experience.

The secret Isabelle confides to her two new friends is this: when Isabelle was seventeen, she fell in love with a close friend of her father’s. This man, Jake Cunningham, took advantage of her youth in much the same way Mr. Robertson would take advantage of her daughter’s youth years later. Unlike Amy’s misadventures with her teacher, Isabelle became pregnant by Jake. Isabelle’s own father died when she was twelve, but her mother was a gentle soul who wanted to help, not argue or condemn. So Isabelle had the baby, and her mother took care of baby Amy while Isabelle drove to the teacher’s college a couple of towns over. Her mother died that January of a heart attack in her sleep, so Isabelle dropped out of college. More than anything, she wanted a father for her baby, and there was no eligible husband material in their town, so she sold her mother’s house and moved to Shirley Falls. She never found eligible husband material there, either, but stayed because what choice did she have?

Dottie and Bev don’t react the way Isabelle thinks she herself would if told this story by someone socially superior to her. Isabelle would be shocked to speechlessness, then she would find a reason to excuse herself. But these women—her coworkers—are sympathetic yet not shocked. They don’t judge her, but upon learning that Jake Cunningham had been a father of three, they let her know that they feel Amy has a right to this information. She has siblings! The possibilities! The three of them sit, smoking, for hours, discussing all of this, men and their deficiencies, the world and its complexity, God and His mysterious ways.

The night produces a change in Isabelle’s worldview that manifests itself in how she sees Amy too, and not just Amy, but their relationship. In a gesture of apology, she takes Amy to a hairstylist to shape her hair, grown out a bit from the awful night Isabelle hacked it off, into a pretty style that shows off her face rather than hiding it. At the salon, the stylist asks if she can put a little makeup on Amy, just for fun. Isabelle has always forbidden Amy to wear any makeup at all, even lip gloss. To Amy’s astonishment, Isabelle says yes, go ahead.

“Isabelle smiled and nodded again, then looked out the window once more. Awful to think she was a disapproving mother. Awful to wonder—had she always frightened Amy? Is that why the girl had grown up so fearful, always ducking her head? It was bewildering to Isabelle. Bewildering that you could harm a child without even knowing, thinking all the while that you were being careful, conscientious. But it was a terrible feeling…knowing that her child had grown up frightened. Except it was all cockeyed, backwards, because, thought Isabelle, glancing back at her daughter, I’ve been frightened of you. Oh, it was sad. It wasn’t right. Her own mother had been frightened too. (Isabelle’s foot was bobbing quickly, in tiny little jerks.) All the love in the world couldn’t prevent the awful truth: You passed on who you were.”

Isabelle does tell Amy the entire story, and, at Amy’s request, writes a difficult letter to Jake’s widow, who writes back with forgiveness and regret that Isabelle hadn’t stayed in touch and hadn’t wanted money, when Jake had been ready to take financial responsibility for Amy. The three Cunningham children were eager to meet their sister, especially Catherine, the eldest, and would Isabelle care to bring Amy to the next family gathering in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, for the baptism of Catherine’s baby?

The novel concludes as Amy and Isabelle are driving to Stockbridge:

“Yes, Isabelle would remember this drive, the yellow leaves, the autumn goldenness.[…] It marked to her the endless days of Amy’s solitary childhood, and those endless hot days of that terrible summer. All that had once been endless would by then have ended, and Isabelle, at different places and moments in the years to come, would sometimes be surrounded by silence and find in herself only the repeated word ‘Amy.’ ‘Amy, Amy’—for this was it, her heart’s call, her prayer. ‘Amy,’ she would think, ‘Amy,’ remembering this day’s chilly, golden air.”

#book report#Amy and Isabelle#Elizabeth Strout#fiction#mothers and daughters#10/10 stars#SUCH AN EMOTIONAL AND SATISFYING BOOK

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

KING SOLOMON’S CARPET

By Ruth Rendell (writing as Barbara Vine)

©️1991; 356 pg; Harmony Books

Ah, Ruth Rendell makes her first appearance (but not her last) in this blog. She’s famous in her native Great Britain, but I’ve never met anyone else who ever heard of her. She died in 2015, leaving an enormous body of work. All of it was published under her own name and a pseudonym, Barbara Vine. It took me a while to figure out the differences between a Rendell book and a Vine book—I loved ALL the Vine books, but I found fewer Rendell that I enjoyed. I first read Ms. Vine’s work upon the release of A Dark Adapted Eye, a tour-de-force of psychological suspense that was very different from Ms. Rendell’s well-known series of Inspector Wexford detective novels. She wrote other books under her own name that weren’t part of the detective series, some of which are every bit as suspenseful and psychologically complex as her pseudonym’s, and those I have all read.

Vine’s books are interested in the lives of ordinary people surviving, usually in London—either struggling economically, or, more likely, because of mental illness. Or both. She delves into the personalities of these people and she explores why they make the choices they make—and their various quirks, eccentricities, addictions, and delusions—with a thoroughness that’s riveting. I’m a psychologist’s daughter, so this is my jam. I love her careful reveal of how all these disparate lives with their attendant problems come together to form an engrossing story. No matter how I try, I can’t guess what the common thread will be amongst the characters, but they always evolve into a complete tapestry that touches them all with tragic and often profound consequences.

This particular story isn’t one I consider among her best, but it sucked me in all the same. It’s set in l988 London, where AIDS was making its way through the gay community and Communism seemed to be dying out, although it is NOT an AIDS-crisis story. The title refers to this:

It’s the London Transport Underground, familiarly known as the “tube.” A vast, interconnected system of trains, sometimes underground, sometimes not, that Londoners use to go everywhere it does. This book’s characters all use the Tube, some live near its stations and tracks, one is obsessed with it, some work in it, some commit crimes on it, and some die because of it.

“While they waited on the platform Jarvis told them about King Solomon’s carpet. This magic carpet of green silk was large enough for all the people to stand on it. When ready, Solomon told it where he wanted it to go and it rose in the air and landed everyone at the station they wanted. He said the tube reminded him of this carpet and elaborated his theme, but they were not listening.”

Jarvis Stringer has inherited the old Cambridge School building. His parents had run a school for girls after the war, so it was constructed with dozens of rooms and a bell tower, from which his father hung himself when Jarvis was a boy. At the start of this story, Jarvis hasn’t anywhere else to live. He received a small inheritance along with the school, which provides basic sustenance, but Jarvis needs money. Jarvis needs money because his hobby (obsession) is the study of major metropolitan subway systems of the world. Traveling is expensive, even for someone as frugal as Jarvis. He’s already been to New York to ride and inspect the world’s largest, he attended the opening of Atlanta’s MARTA, and has marveled at San Francisco’s BART, which has the deepest track in the world under its bay. He badly wants to visit Omsk and see the rumored many new stations and expansions of its system, and at the beginning of this book, he’s saving his money. He’s a kind man, even if nearly everyone would consider him eccentric. Jarvis doesn’t mind. While saving for his planned trip to Russia, he’s writing a book: a complete history of the London Underground. This takes up most of his time, sitting in his room in the School, typing. He is only vaguely aware of his surroundings, for he lives in his own head much of the time.

Jarvis decides to rent the rooms of the School for extra income. He charges rents so absurdly low as to guarantee a ready supply of tenants. These people, their backgrounds, their chance meetings, their passions and betrayals, their inadequacies and desires, all join together at the School. These connections, both planned and spontaneous, form the plot of this novel.

Occupants of The School:

Tina is Jarvis’s cousin. Her mother Cecelia and Jarvis’s father were siblings. Tina has two children, a 9-year-old boy named Jasper and a younger girl, Benavida. As the novel opens, all three have moved into the school with Jarvis. Tina doesn’t know who the fathers of her children are, as she has slept with every man she has ever met, including cousin Jarvis, long ago when they were teenagers. Tina’s mother, Cecelia, lives within walking distance of the School, but they don’t get along very well due to Tina’s aforementioned propensity for casual sex and lax attitudes towards disciplining her children. Cecelia disapproves of nearly everything about Tina, but she has learned to censor herself so she can continue seeing her grandchildren.

Tom is a talented singer and flutist, a musical prodigy who could play a little piano and trumpet, too. Tom attended the prestigious Guildhall School of Music and Drama, and flourished there. One day, instead of making the complicated train journey from visiting his grandmother’s house in Ealing back to London, he accepts a ride on the back of a motorcycle from his gran’s neighbor. They hadn’t gone a mile when the crash happened. The driver died under a lorry’s wheels, but Tom was thrown clear of the wreckage and hit his head on a tree. He spent six months in hospital with many broken bones and emerged, after several surgeries, with a permanently crooked little finger on his left hand. He has lost his place at school, he’s depressed, he has trouble concentrating, migraines, black thoughts, and rages (it’s obvious Tom has suffered a Traumatic Brain Injury, which wasn’t yet a thing when this novel was written.) He ends up busking in the stations of the Underground, trying to regain his former ability to play the flute.

Alice is 24, a gifted violinist, wife, and mother of a baby girl. Her marriage is loveless, and she felt nothing but guilt at being a mother whose heart wasn’t completely engaged by her baby. She longs to play her violin well enough to join an orchestra that would travel and perform regularly. Motherhood is incompatible with her ambition, so she leaves her family a note that she won’t be returning, and escapes to London with just £100.

Jed is a volunteer Safeguard on the tube. Safeguards are to England what the Guardian Angels are to New York: men who ride the trains, looking for trouble to stop. His passion, however, is his pet hawk, Abelard. Jed always smells of the rancid meat he feeds Abelard, so people generally avoid him, and he takes Abelard with him everywhere he goes, except on his nighttime train rides with the Safeguards.

All of these people, each unknown to the others (except Jasper and Tina), move into the School, and they all live together comfortably enough. Jarvis originally met Tom while walking through a tube station when he stopped to hear Tom’s classical trio busking. Jarvis met Jed on the tube, late at night during one of Jed’s Safeguard patrols. Because neither Tom nor Jed had a permanent place to stay, and because Jarvis was a kind man, he invited them both to move into the School. Alice, the runaway wife and mother, is the next to move in. Just after leaving her husband and daughter, upon arrival in London, she hears Tom’s voice and flute in the tube station. She recognizes the piece, she has her violin, and almost without meaning to, she joins in with the buskers. Tom falls in love with her the minute he sees her, and invites her to come live at the School. Tom and Alice are a couple from that moment on, but while Tom is madly in love, Alice is not—she just felt she had no alternative.

There is almost always an older, judgmental person in Barbara Vine’s books; one who feels superior enough to try to impose their views on other people, who manipulates and lies with equanimity, and we are definitely meant to dislike that character. In this book, it’s Tina’s mother, Cecelia. However, in this case, we are also meant to sympathize with and understand her frustration with her daughter. We are gradually, in small increments, given to understand that Cecelia and her best friend since school days, Daphne (both are in their seventies), are in love. Neither one is aware of it, exactly, and nothing physical ever happens. No words are spoken between them of this kind of love. They’re content to visit each other once a week and talk on the phone at exactly the same time every night. Cecelia is acutely aware of how the world perceives her:

“She might not have been there for all the notice they took of her. However, Cecelia was used to that and did not even mind much. She knew very well that the least noticeable, the most invisible and indifferently regarded of all human beings, is an old woman.”

Cecelia is old-fashioned, judgmental, and disapproving, yes; she also exhibits personal growth and self-awareness that were previously unknown to us as the story unfolds.

Terrible things have happened, are happening, on the tube.

The book opens with an account of an afternoon in the life of a much-pampered, privileged, wealthy woman who had always been “delicate” and fussed over due to her “heart murmur.” This unnamed woman takes a taxi to Harrod’s to buy a dress for a party that night. It’s a beautiful dress of pure white, heavily embellished and embroidered. On a whim, she decides to do what common people do and take the tube home. But she’s never been on it in her life, gets hopelessly lost, train after train, disembarking and waiting, shivering, on the platform, then getting back on another and being surrounded by rush hour commuters, squashed between them in the car. She spirals, hyperventilating, panicking, feeling suffocated, and her heart stops. The carrier bag she’d been holding, the one containing the white dress, had been trampled upon and nearly left on the train, but it was returned to her family, along with her body.

That opening vividly illustrated how frightening the tube can be, and imparts dread. Who was she? Why was the dress described so thoroughly? So she had a panic attack brought on by the crowd, which brought on a fatal heart attack, which is tragic for sure, but she has no connection to any of the characters. The significance of this event won’t be revealed until the end, and even then, you have to work a little bit for the connection, but when it comes, it’s just ANOTHER thread neatly woven into the tapestry that is this story. And there are many.

Tina’s son Jasper “sledges.” Sledging is riding face down on the top of a subway car itself. It’s illegal, and it’s dangerous. Jasper is nine years old, smokes regularly, has a tattoo of a lion on his back that nobody knows about, and cuts school so much he’s being suspended. Tina loves him in her own distracted way, but she doesn’t know where he is most of the time, doesn’t know (or doesn’t care?) about his truancies, doesn’t worry, and isn’t home herself for days at a time. Tina knows her mum lives just a short walk away, and she takes Cecelia’s proximity and availability for granted. Jasper’s fellow delinquents have been cutting class to hang out on the tube, generally being nuisances, annoying other riders, and smoking. One of them describes sledging and claims to have done it himself from one station to the next. Very quickly, Jasper becomes a veteran sledger who knows the tunnels and clearances of the tube, and he’s very good at it and never gets caught. But one of his mates, simply to avoid being dubbed “chicken,” attempts his first sledge ride while Jasper is sitting in the car below. The train had to slam on its brakes and come to an emergency stop while in a tunnel, on tracks high above the subterranean depths of older, deeper tunnels. The boy was flung from the roof and killed, right before Jasper’s eyes. By the end of the book, it seems likely that Jasper, too, will suffer from PTSD. That’s really unfortunate, as Tina will never notice.

Jarvis literally knows nothing about his tenants or what they do under his roof. He departs London for Russia about halfway through the book, and doesn’t return until after the climactic event occurs. But it’s through his obsession with subway systems and the book he’s writing about the London Underground that we are able to read various facts and trivia about the tube. I found these sections fascinating. Gradually, these sections become smaller, but contain more gruesome details. A huge fire at King’s Cross station destroyed much of it and killed 30 people. A train full of riders crashed head-on into a blocked-off tunnel and killed 50. Air raids during WWII caused massive amounts of people to seek shelter in the stations of the Underground; still, Luftwaffe bombs struck their targets, obliterating them and the people sheltering within. But there had never been a successfully-detonated bomb placed into the Underground by a person or people (this was written long before 7/7/05).

Everything this author does is in gradual increments that can go two ways when they’ve accumulated into a giant reveal: either it’s like a light appears and illuminates the truth of a character or situation, or it’s like all light is extinguished and you might feel a tight ball of dread that lodges behind your ribs because you know disaster is coming. Rendell/Vine is a MASTER at this.

The final character to enter this story, Axel Jonas, a man who apparently torments tube commuters for fun, encounters Jasper rather dramatically in a tube station just as Jasper flings himself off the top of the subway car, narrowly avoiding being decapitated by a steel overhang at the entrance to the tunnel ahead. Axel starts a conversation with the boy about his sledging, then offers to take him for pizza. Jasper is perpetually hungry, and he’s inclined to like this man because he doesn’t chide Jasper for sledging. Axel asks Jasper a litany of questions about the tube itself, specifically whether or not Jasper knows anything about “ghost stations,” or stations long closed and unused that trains never stop for. Some of these stations supposedly have ventilation shafts that go right up through the centers of office buildings. Jasper replies that Jarvis could tell him, Jarvis is his mum’s cousin, he knows everything about the tube, he and his family live with Jarvis at a school, Jarvis has even gone to Russia to see their subways, and then he gives Axel his last name. Jasper tries to memorize the man’s face with its cornflower-blue eyes, short dark beard, and short black hair, so he can tell Bienvida all about their strange lunch.

Axel turns up at the School. Alice, the only one home, answers the door. Axel pretends to know Jarvis, pretends he spoke to Jarvis before he left for Russia and rented a room from him. Alice accepts this (everything in the School is done on impulse without much deep thought), and Axel moves in. Alice is immediately entranced by Axel’s blue, blue eyes, and his mysterious nature, and eventually they begin an secret affair, in the rooms just above the room she shares with Tom.

What is gradually revealed is Axel’s sinister plan. He wants, badly, to destroy the Underground, or at least cripple it so badly that it stops running, hopefully forever. He uses Alice’s infatuation, Tom’s friendship, and Jasper’s youth in his attempt to accomplish this goal. Axel never tells anyone what he’s doing. He hides every part of it from his fellow inhabitants of the School, and selects Tom to be his unwitting accomplice in his mission. None of the characters have any idea of his plan.

Alice, lovesick and yearning, picks a night Axel is out, and goes through his suitcases, drawers, and cupboards. She doesn’t suspect him of anything, but is desperate to learn who he really is, where he’s from, and what he might be hiding from her. She finds, but does not recognize it for what it is, a heavy plastic bag taped shut that’s full of some kind of liquid. She seals it back up and returns it to the closet so that Axel won’t know she’s snooped. The room smells strongly of petrol afterwards. Oddly, she also finds, in an old, stained carrier bag hanging in the closet, a a beautiful dress of pure white, heavily embellished and embroidered, and she wonders: is this a gift for herself? There is a small photograph in his suitcase of a lovely woman with his same dark hair and cornflower-blue eyes, and Alice knows immediately the photo is of his sister.

Reading this was a bit like I imagine heaven to be. My heaven, anyway. I raced through the last parts of the book as the stakes got higher and higher, and the narrative thread got tighter. And as usual with Ruth Rendell, I marveled at the seemingly effortless way she weaves separate storylines together to create a cohesive, propulsive suspense novel. So much suspense! I won’t detail how the story ends, but you can guess, I think. I enjoyed this re-read!

#book report#King Solomon’s Carpet#Barbara Vine#Ruth Rendell#fiction: psychological suspense#7/10 stars (only to leave room for her best)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Quotable – Ruth Rendell

Find out more about the author here

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

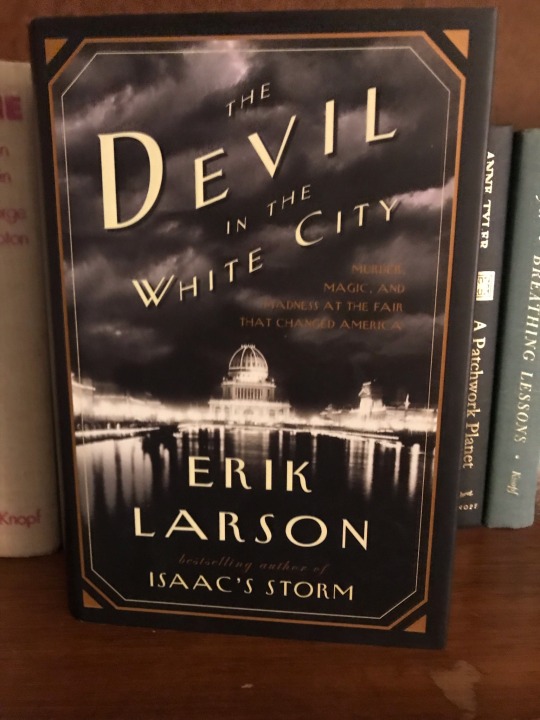

THE DEVIL IN THE WHITE CITY:

Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America

By Erik Larson

©️2003; 390 pg; Crown

The 1893 “World’s Columbian Exposition,” better known as the World’s Fair, opened to the public in May on the southern shore of Lake Michigan in Chicago. The nod to Columbus in the official title was ostensibly to celebrate the 400th anniversary of his voyage’s end in the New World, on October 12, 1892, and the word “fair” was deliberately left out. “Fair” conjured images far too pedestrian for what Chicago was building. “Exposition” was much grander, and the world had become accustomed to the shortened “Expo” as a term for marvels, wonders, excitement, food and drink, games, and activities brought together in one place and offered up (for the price of a ticket) for the public’s enjoyment. America was again taking her turn at hosting this extravaganza, and Chicago had beaten New York City and St. Louis for the right to host. Chicago had also officially become America’s second-most populous city according to the 1890 census, beating out Philadelphia, and civic pride was high. The city needed to show that it had recovered from the Great Fire of 1871, in which 18,000 buildings were destroyed and 100,000 people were left homeless. Civic solidarity strengthened as construction started on the site, known as Jackson Park.

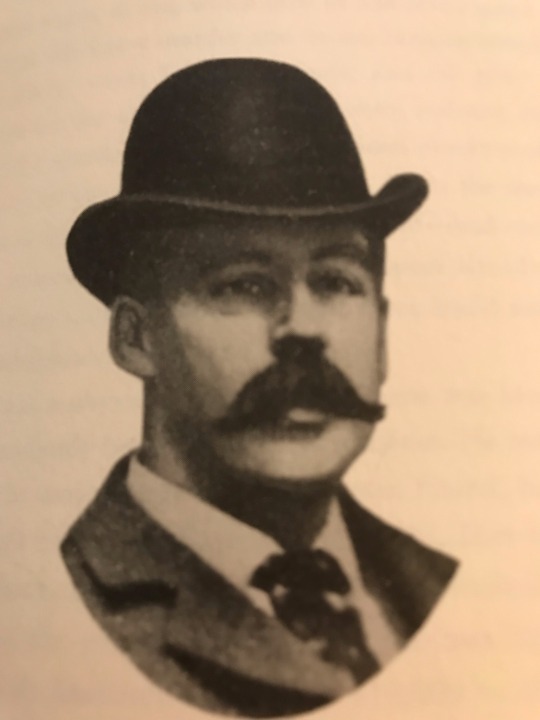

At the same time, a young sociopath from New Hampshire named Herman Webster Mudgett made his way to Chicago, lured by the promise of the fair and its attendant spike in tourism and foot traffic. He would change his name to Dr. H. H. Holmes, taking his new surname from the popular novels of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s brilliant detective. “Dr. Holmes” worked as a pharmacist while building his “hotel” on a big lot at the corner of 63rd and Wallace, near the future Midway and main entrance to the fairgrounds. His dark, ugly, infamous hotel would rise just as the beautiful, shining buildings of the World’s Fair were being built by over 20,000 men.

Herman Mudgett, aka H.H. Holmes

This book is a perfect study in contrasts: the most high-minded American ideals of purity, patriotism, pride, and beauty versus the depravity of a serial murderer of men, women, and children. In particular, the commitment to architectural and landscape design beauty possessed by Daniel Burnham, the Chicago architect who became the fair’s Director of Works, is a great counterpoint to the sociopathic charm, insincerity, greed, and chronic dishonesty of Holmes. These are the two men whose stories are told, accompanied by transcripts of correspondence to and from both men, and the reader comes to know Burnham quite well. Holmes, however much we read his own words, remains a mystery. For me at least, all sociopathic true-crime killers’ minds will forever be impenetrable. Their charm is strictly surface-level; their intelligence bent towards manipulation.

I found the parallel narratives of Holmes’s Chicago years and Burnham’s years spent building the fair beautifully described, and I never got bored. But while I suppose the story of Holmes, his “murder castle,” his victims, and how he disposed of the bodies is fascinating, it’s the other half of the story that really glued me to these pages. The planning and construction of the 1893 World’s Fair, with all its complexity: the architects, the engineers, the steel suppliers, the horticulturists, the design and build of each individually-contracted building (that had to match, design-wise, with all the rest in order for the vision of Burnham’s “White City” to be realized)—the fact that this place existed at all was a miracle of American determinism. Burnham’s story is mainly one of a man with great artistic vision and inner strength plus the cooperation of thousands of people, working together to create and execute a World’s Fair that would AT LEAST rival the 1889 fair in Paris. That fair had the singular distinction of having unveiled to the world a tower, 1000 feet tall, the highest in the world at that time. The designer was Alexandre Gustave Eiffel, and newspapers all over the world reported on the wonder of its design and thrilling viewing opportunities.

Daniel Burnham, as Director of Works, hired Frederick Law Olmsted to design the exposition’s landscaping. Olmsted had designed and built Central Park in New York, as well as the lawns and gardens of several millionaires’ estates. Burnham personally oversaw and approved the design and construction of every building and every exhibit. But time was short—he’d only landed the assignment when the city of Chicago had, in 1891. Jackson Park was a neglected wasteland of scrub-filled sand and water, and all of it would be the foundations upon which he would build a place of such beauty that Chicago’s “Black City” would be repudiated by his “White City.” Burnham ordered that all buildings be painted white, except for the gold dome on the Administration Building and the gold atop the Statue of the Republic. Olmsted directed the digging of lagoons, the creation of a Wooded Island to show off the native Illinois foliage, the placement of gravel walkways, and the judicious planting of vines, ferns, and the occasional colorful wildflower. These two men, then, along with hundreds of other talented creators, built an entire World’s Fair out of nothing in something like 20 months. There are not many photos in the book, but this one shows a main attraction, the Peristyle, along the main plaza:

The dedication day was scheduled for October 12, the very first Columbus Day, celebrating 400 years of America. From 2021, this seems ridiculous, but…hindsight. The ceremony included only the top people in Chicago society and/or top administrators of the build. The fair wasn’t ready to open to the public by October 1892—far from it. Opening day was scheduled for May 1, 1893, and Burnham was nervous. Things had repeatedly gone wrong—workers had been killed in accidents and there were several fires. Unpredictable spring storms caused massive sheets of glass and steel ceilings of the largest building, the Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building, to fall and shatter on the floor of the building, damaging many exhibits. But Burnham believed in repairing and moving on as quickly as possible from one catastrophe to another. Maybe he found encouragement to keep going in his belief that he had found the one crucial element that would forever distinguish his fair from all others, and possibly even surpass the 1889 Eiffel Tower in innovation and entertainment value.

Burnham knew he needed a centerpiece attraction. He contacted every reputable engineer he knew of from all across the country and solicited ideas. Some of the rejected ideas are HILARIOUS:

“…a tower with the height of 8,947 feet (nearly nine times the height of the Eiffel Tower), with a base one thousand feet in diameter sunk two thousand feet into the earth. Elevated rails would lead from the top of the tower (in Chicago), all the way to New York, Boston, Baltimore, and other cities. Visitors ready to conclude their visit to the fair and daring enough to ride elevators to the top would then toboggan all the way back home.”

“…[another] proposal demanded even more courage from visitors. This inventor…envisioned a tower four thousand feet tall from which he proposed to hang a two-thousand-foot cable of ‘best rubber.’ Attached at the bottom end of this cable would be a car seating two hundred people. The car and its passengers would then be shoved off a platform and fall without restraint to the end of the cable, where the car would snap back upward and continue bouncing until it came to a stop. The engineer urged that as a precaution the ground ‘be covered with eight feet of feather bedding.’”

But one young engineer who worked for the steel-inspection company contracted to the fair submitted a proposal for a completely original structure that had haunted him ever since he first heard the fair would be in Chicago. He’d gone so far as to work out much of the design, including the calculations to test its structural integrity, and he was satisfied his “Wheel” could be built, would work, and would be safe. His name was George W. G. Ferris, and his 264-feet-tall wheel would be built as a main attraction on the Midway, giving riders sweeping views of the fairgrounds and the lake. It would require 28,416 bolts and have 32 cars weighing 13 tons each, carrying an additional 200,000 pounds of human beings. Nobody had ever attempted anything like it, and it was enormously popular. From that point forward, every fair and carnival in America would have a version of the Ferris Wheel.

There’s so much interesting detail about the inventions and wonders on display at the fair, and so many surprising and unexpected guests. Dignitaries from all over the world sailed to America to attend, as did celebrities and aristocrats. Shredded Wheat was introduced to the public here. Visitors could listen to an orchestra playing live in New York via long-distance telephone. The first-ever zipper was exhibited to much enthusiasm. Intrepid visitors could visit the first all-electric kitchen, sample an oddly flavored chewing gum called Juicy Fruit, and munch on a new snack called Cracker Jack. Innovations in science were proven as Nikolai Tesla shot lightning from his fingertips while Edison displayed moving pictures on his “kinetoscope.” Francis Bellamy, an editor of Youth’s Companion, composed a pledge that he thought would be a fine thing for schoolchildren all across the country to recite in their classrooms on Dedication Day. The Bureau of Education agreed, and mailed a copy to virtually every school. It began, “I pledge allegiance to the flag…” And the magnificent Ferris Wheel drew ticket-buyers in exponentially greater numbers each month. Its popularity only grew as it was accepted as being a safe yet exhilarating ride.

The White City as seen from Lake Michigan

Meanwhile, Holmes occupied himself with completion of his monstrous “hotel” that became known as “the castle” in the neighborhood. It was an ugly building, particularly when compared to the brilliant and inviting facades of other buildings in the area, so close to the fair that it seems to have inspired individual owners to spruce up their properties as much as possible. Holmes used no architects or engineers to help build his hotel. He drew the plans himself and never allowed anyone, contractor or supplier, to remain on the job for very long. Later, it was surmised that this unusual practice of hiring and firing workers ensured that no one apart from Holmes had any idea of the scope of the building or what was inside. Corridors veered off at strange angles. Narrow hallways contained too many doors for there to be spacious guest rooms behind them. He also contracted a manufacturer to produce a box to his exact specifications: fireproof brick, eight feet long by three feet wide, “encased in a second box of the same material, with the space between them heated by flames from an oil burner.” His excuse for needing a coffin-sized kiln was to produce and bend plate glass for his fictitious Warner Glass Bending Company. At this point, Holmes had married twice (without divorcing) had at least one child, and had successfully pulled a number of small-to-medium con jobs in several states prior to his arrival in Chicago. He had undoubtedly also committed murder, but now he was poised to offer lodging to unmarried women or groups of women, some with children, who were visiting the fair. Many would never be heard from again, and their fates would be unknown until long after the fair had closed forever.

There is no doubt the 1893 World’s Fair left an indelible impression on America. When you consider that the population of the U.S. was 65 million, and the fair counted 27.5 million visits by tickets sold, it’s absolutely remarkable. On “Chicago Day” in early October of 1893, attendance was 751,026—“more people than had attended any single day of any peaceable event in history.” After it closed on October 30, 1893, Burnham and the rest of the planners and builders fell into a depression. Two days earlier, the wildly popular mayor of Chicago, Carter Harrison, was shot and killed by a young, floridly psychotic Irish immigrant (whose brief story is the book’s subplot.) The city itself succumbed to the sadness and loss a political assassination and the close of the shining, otherworldly White City brought to its residents. The buildings and grounds of the fair began their long slide into disrepair, and newspapers cried that it should all be burnt rather than the city’s residents see the iconic buildings blacken and collapse. This sentiment came true:

“On July 5, 1894, arsonists set fire to the seven greatest palaces of the exposition—Post’s immense Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building, Hunt’s dome, Sullivan’s Golden Door—all of them. In the Loop men and women gathered on rooftops and in the highest offices of The Rookery, the Masonic Temple, the Temperance Building, and every other high place to watch the distant conflagration. Flames rose a hundred feet into the night sky and cast their gleam far out onto the lake.”

Holmes, too, left an indelible impression. In 1894, evading telegrams and letters from families of young women and their children who’d never returned from the fair or his hotel became unbearable. He was being sued by many of the creditors he still owed for their work on his strange, ugly building. Holmes decided it was time to leave Chicago, first setting fire to the top floor of his building in an attempt to erase it and its secrets, but the fire failed to progress beyond that floor. He tried to file a fire damage claim with his insurance company, but they refused payment and opened an arson investigation for which he was arrested and jailed in Philadelphia in 1895. But it was thanks to the obsessive work of one detective, Frank Geyer, that a murder charge was added and many more human remains would be found on Holmes’ properties. The alleged murder for which he would be convicted wasn’t of any of the young women he’d lured into a romantic relationship, but of Benjamin Pitezel, his assistant and employee at the hotel. Pitezel’s two small daughters were also missing and hadn’t been seen or heard from in months. He was murdered by Holmes after leaving Chicago for Indianapolis. His remains, and, cruelly, the remains of Pitezel’s two small daughters, were found by Det. Geyer in a rented house in Irvington, Indiana. Holmes was in jail in Philadelphia for insurance fraud, indicted for murder in Indiana, and he was wanted in Toronto, again for murder.

Eventually Holmes stood trial for the murder of Benjamin Pitezel, was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. His execution was carried out in May 1896. After his conviction, he confessed to 27 murders, 9 of which were confirmed prior to his death. Authorities estimated his count at 200 victims, but this was never proven. Was he America’s first serial killer? Certainly many other true crime writers believe so.

This book was just as fascinating to read now as it was the first time. It’s much more difficult to report on nonfiction than fiction. Names, dates, and places need to be accurate, and I’m always aware that I’m trying to summarize real events. That matters to me. I take far more notes/reference the text when I’m writing a book report that’s also a true story, but still, errors can happen. Any mistakes in this book report are my own. Erik Larson is a brilliant writer, and I own several of his books, so this won’t be the last time I write a report on one of his extraordinary true stories.

#book report#The Devil In The White City#Erik Larson#nonfiction#true crime#10/10 stars#1893 World’s Fair#Chicago

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

ALIAS GRACE

By Margaret Atwood

©️1996; 465 pg; Nan A. Talese/Doubleday

I didn’t really want to re-read this one because of the 2017 Netflix miniseries adaptation. I’ve only read this book one time, when I bought it new, but my memory of it was pleasant. When the miniseries debuted on Netflix, I tried to watch it, but it was terrible, which made me question my memory. That was my opinion in 2017. Maybe I’ll give it another shot now that I’ve finished the book, because I enjoyed it so much this time around.

This is fiction, yes, but it can be considered historical fiction. Grace Marks, her alleged crimes, and nearly all the characters who appear in these pages actually existed, and the events described actually occurred. In 1845, in Toronto, a 15-year-old household servant was arrested and tried for murder and being an accessory to another. The victims were Thomas Kinnear, an unmarried man of some wealth, and his housekeeper/lover Nancy Montgomery. They were killed with an axe (Kinnear) and by strangulation (Montgomery.) Grace was just a servant who did cleaning, sewing, laundry, gardening, and feeding the animals. Nancy was Grace’s superior, so she gave orders that Grace carried out. Kinnear’s farmhouse was in Richmond Hill, a suburb north of Toronto now, but in the mid-nineteenth century, it was so far from that city that it took eight or more hours to reach by carriage.

We meet Grace in the present of this book, which is in 1861. She is the narrator of her own life, and so the reader comes to know and understand Grace quite well, as first-person accounts are generally rife with the character’s thoughts, feelings, and perspectives. She is a convicted murderess who had her death sentence commuted to life in prison, mainly due to the efforts of a group of upper class professionals who found her story tragic and did not believe Grace could have committed one murder, much less two. Grace’s main defense at her trial was her near-total amnesia surrounding the night of the murders. She can’t remember what she said or did—only the terror:

“When you are in the middle of a story it isn’t a story at all, but only a confusion; a dark roaring, a blindness, a wreckage of shattered glass and splintered wood; like a house in a whirlwind, or else a boat crushed by the icebergs or swept over the rapids, and all aboard powerless to stop it. It’s only afterwards that it becomes anything like a story at all. When you are telling it, to yourself or to someone else.”