Text

what is art?

Art is something I have always found an easy appreciation for. Aesthetically, visually, physically, all avenues of art have something specific and special to offer to its viewer, and that interaction has always fascinated me. I think that I have always leaned towards appreciation, especially when it comes to art, mostly because I’m terrible at it. Art is a constant battle, while writing, something I have practiced far more often for a far longer period of time, comes easier. So maybe it is in this inexperience that boosts my appreciation for art because at the moment, the skill and talents and styles of all artists feels so out of replication’s reach for me. Or maybe it’s all emotion, how art can change you. Maybe it’s both, or in everything we’ve learned about in this course about the world of art, all communicating with one another.

Through this class, my perspectives have shifted. Art is something within us that we can’t name, but only feel. Blind light. Like the lexicon of art, we are all trying to speak to the same thing. When considering the most important thing I learned in this course, I believe it’s that it has helped me come to the conclusion that art could go on forever. Even when we feel like there is nowhere else to go, or that everything has already been made, everything has already been said, the glass breaks, and a new color bursts forwards, and makes the whole room bright. Art is a place for the things that are not sayable in just one way. It’s the perfect place to express the things that are hungry, or empty, within us that we don’t like to talk about, because it makes us vulnerable. People come to art with a different mindset, approach, and appreciation. Viewing a piece is never the same twice.

In Advance of the Broken Arm, Marcel Duchamp. 1964. The Museum of Modern Art.

Perspective is the biggest component of art that I learned more of through this class. We spent a lot of time going over what makes art different from everything else, domesticity versus the prestige that comes with pieces hung on gallery walls. In the Art Assignment’s Art or Prank video speaking about the inclusion of everyday objects, to take legitimacy into what is perceived as to be art, and what it can become: “We take simple, everyday materials and subject them to transformations large and small, as large as making a blank piece of fabric into a painting, or as small as positioning an object in an art gallery. These transformations ennoble these materials, making them into something more than the sum of their parts.” (Art or Prank) This can be directly seen through Marcel Duchamp’s Readymades – pieces of mass-quantity produced objects that became art because of the artist’s intent. This highlights my favorite component in art: that it exists everywhere. That as overstated and oversaturated as it is, the saying “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” actually has somewhat of a legitimate basis, a standing in art. That the fact of a viewer’s opinion in this question being “what makes art, art” – is actually an incredibly influential and important part of the answer when questioning society as a whole.

Learning this validation of subjectivity and participation within art, changed me. Like new ways of seeing a piece brought new ways of being. I was seeing meaning, everywhere. In color, in form, in origin. Like art was, is, something crafted out of the quiet, the loud. Each stroke, each layer accumulates into a symphony, with unique voices, each with their own message, their own ways of existing. Like a speech after a long silence. Even when visiting the Art Institute halfway through this course, art had already started to shift in my head. I wanted to ask questions about what is the piece trying to say, and how do I feel about it, aesthetically, meaningfully, structurally? It still feels like I walked in with questions and came out with hundreds more.

We’ve spent eight weeks speaking and learning about all of these aspects about art, and I still have questions. That’s something I learned for certain in this course: there will always be more to ask, more to know, there is always the presence of curiosity. To abate that curiosity, we spent a majority of our time researching, always alongside every piece we did. In reading all about the art of non-western cultures, beauty, craft, history, modern day artists, among many other topics, it all accumulated into this eight week crash course into what felt like every nook and cranny of the art world. The best part: whatever I didn’t research and look into, someone else did, and I got to see it through their eyes, what they found, what they felt about it. It felt multi-perspective, which is my favorite way to view art: from all angles.

Parthenon, Athens Greece. 1978. Wikipedia.

One of the most intriguing things I learned was after we’d done both the comparison of Arts and Crafts, as well as the Prehistoric and Ancient Art Forms discussion, where I studied Ancient Greece’s Hellenistic Art. The study of these in close affinity of one another brought up realizations I hadn’t seen coming: I love the look of old historic objects and art pieces, but especially ruins. This wasn’t the surprising part, though, the suprise was in the fact that the impact of time is utterly unavoidable, and we see it upon so many objects from places all around the world. I love the fact that we still celebrate them despite them being worn away, that even in whatever shape they’re in now, broken, missing pieces, weathered away, they’re still considered art. From domestic objects to commissioned pieces and everything in between, they’re put behind glass cases and shown to the world under the name of art.

But ruins are something else entirely, aren’t they? Ruins are hard to put behind glass cases. They’re hard to move, to bring home in our pockets and showcase. They’re not portable, and they’re not what they once were made to be shown as,. They’re ghost stories in the shape of puzzle pieces, where we take stories to fill in the blanks. Ruins may be different from their original forms, but they’re still art. They’re accidental aesthetics, echoes of what they used to be. This distinction comes in the aftermath, of what they look like now, the fact that they are not seen as the original intention. But are they still art, in the same way? Is it the memory that makes them art, the comparison? The before and the after? Or is it the inspiration, the way that so many styles of architecture can still be seen in modern structures today? Or that people still go and visit these places, half-gone? What is art then: the pieces that are missing, or the way we fill them in, or the pieces that are still there?

Replica of the Parthenon, in Nashville, Tennessee.

In asking these questions, the Parthenon is one of the most interesting ruins to think about in this way, because we have the original, what it looks like today, time-weathered, but we also have a replica that’s been recreated. The version of the Parthenon in Nashville, Tennessee, is what the structure may have originally looked like at its prime. We have the direct before and after, present and open, and are free to compare the two. To have this direct comparison, we are able to ask questions, some along the lines of how time affects the meaning of the piece, and if the face-value of the image of a piece impacts how we see art at different points in our lives, or even different points in our history? And what do we do when we have two pieces of weathered ruins, neither looking like what may have been the original? What then?

If you’d asked me anything about Institutional Critique before we researched it for last week’s discussion, I wouldn’t have assumed it to be so prominent and active in the art world. Academia, maybe, politics, absolutely, but not so much art. Not to the intense details that art’s Institutional Critique does. But as with all money-headed empires, it’s easy to assume that there is institutional disconnect between groups within, but work that contributes to the theme of Institutional Critique in art goes farther, tying in meaning, place, and time. It includes all members of interaction with a piece: the artist, the audience, and the owners of the place showing the art itself. It is all-inclusive in its assessment of the current state of art.

I’m always asking questions, now, when I try to look at art in this new distinctive way given by the designated sections of Institutional Critique. What is it trying to say, what isn’t it saying, what are the ways I could see it differently, or similarly, or completely off the rails in a way that wasn’t the intention at all? But also broader questions, as well, for example, should artwork be read in any kind of sequence? If there is a way that galleries are organized to have a pre-set path for visitors to follow, and even if this is something that artists do as well, in their pieces? Should we categorize art in a way that confines its meaning, its impact? Is there any way to speak about art that doesn’t do this in some way?

Art changes depending on – everything. Who you are, as the audience, the artist, your experiences, your values, your world-views. The way you approach art and the way you let it affect you. Art, in this way, is immensely subjective. It comes in the door one day, built by the artist, and left to be morphed and changed with each pair of eyes set upon it. In this way, art can change people. It can change places. It can change everything, even if by just a little. I never realized how much the simple action of looking at art in a space could impact a piece so heavily. Sometimes the subjects are nearly unrecognizable in the way we look at them, compared to the artist’s vision, or even another person’s view of the same object.

Pieces that have political or societal implications can comment and voice opinions in a way that may have otherwise been routinely silenced. It is within these new ways of making art, and new ways for art to provide a commentary on our lives, that art continues to expand. By this, art can be so much more than pieces in a gallery. Art can be influential, political, changing. In this way, in the words of Suzanne Lacy on her 1977 performance piece that highlights public gender-based sexual violence in Los Angeles, Three Weeks in May, “We are making an art that’s not just for art’s sake, or an art that’s about personal expression, but an art that’s about changing the world, and we believe – I do believe that art can change the world.” (Three Weeks in May)

But changing the world is a difficult thing to do, especially if powerful ideas within the world are working against you. To combat this, art becomes political. Art becomes action. Erich Fromm’s 1963 essay “Disobedience as a Psychological and Moral Problem” attests to this. Fromm speaks about the conviction or principles that revolutionaries follow when being disobedient to the order of things, that it is the presence of those principals or values that are absolutely necessary for their actions, to distinguish them from rebels. (Fromm)

Fromm cements this way of thinking with commenting on the stagnation of emotional progression lacking behind progression of the material, saying: “If mankind commits suicide it will be because people will obey those who command them to push the deadly buttons; because they will obey the archaic passions of fear, hate, and greed; because they will obey obsolete clichés of State sovereignty and national honor.” (Fromm 1) This directly coincides with a later piece, Andrea Fraser’s “From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique,” where she speaks about the inability to separate the art from the art world: “But just as art cannot exist outside the field of art, we cannot exist outside the field of art, at least not as artists, critics, curators, etc. And what we do outside the field, to the extent that it remains outside, can have no effect within it. So if there is no outside for us, it is not because the institution is perfectly closed, or exists as an apparatus in a "totally administered society," or has grown all-encompassing in size and scope. It is because the institution is inside of us, and we can't get outside of ourselves.” (Fraser)

How Fraser phrases that last piece, “the institution is inside of us, and we can't get outside of ourselves” (Fraser), is the perfect phrasing of the problem. If art is an expansion, expression of ourselves, how to we display that without including the pieces of ourselves that others take issue with? The original meaning behind it, whatever that may be? A piece can be rewritten by location or surrounding pieces, but the original creation’s purpose will always be the same. What do we do, when suddenly that becomes a problem? How are we supposed to respond?

Sunflower Seeds, Ai Weiwei. 2010. The Tate Modern.

Revolutionary art can be made in many ways. Physically, within art that is illegally installed, art that exists to question the way that things are, art that raises questions about art itself. Banksy’s work of shredding his painting after it’d been sold, Ai Weiwei’s pieces of combining both political and cultural sentimentalities in works like Sunflower Seeds, Jenny Holzer’s Truisms pasted up like anonymous street posters questioning the state of society, among many others, have merit in being revolutionary pieces. Some of the other works we’ve discussed this semester, especially pieces like Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, exist and were made specifically in the action to challenge preconceived notions of art.

After everything we’ve learned this semester, art is more than what I thought it was at the beginning. Then, I believed that art was an awareness, a way to reshape our consciousnesses into concepts, to give it tangibility and perspective, specifically saying: “[art] gives way to different forms of thinking, of approaching media, of going about our everyday lives. Art, in this way, changes us. It snaps us awake.” (Berg) Art is that – but it’s also so much more. It’s the key to connection, to history, in every narrative, worldwide. Art can influence, widen perspectives, bring finality, or even, usually, mountains of more questions to answer.

Being an artist is an increasingly paradoxical profession as time continues. It is both as powerful as it is vulnerable. Artists are standardized by society in the near-same way it has standardized craftspeople, in the way that their work is open to being over-simplified, alongside the popularized gate-keeping notion that if you don’t understand the way you’re supposed to look at, or appreciate, art the very first time you lay eyes on a piece, you won’t ever understand; which is the farthest thing from the actual truth. Art is a learning process. Art changes with you, whenever you come again and see with fresh eyes. Art lives alongside humanity. We create when we have something to say, or something to hide, or even if we just want to capture a color, a feeling, in a new way. Art, in society, is something that changes with us, and can tell us about what we used to value or what we used to prioritize, even within our own domesticated everyday objects, even within ourselves.

We live our whole lives looking for something. Everywhere, we are always searching. Sometimes we call that something love, or fulfillment, or contentedness, and other times we have a laundry list of other epithets for it. In this search, we try to find parts of ourselves in everything: names, connections, but especially within art, because there is no greater expression than that of what shakes and deforms and ripples with every perspective. In creation, we put pieces of ourselves on display, our dreams, our despair. There is intention, in this, to art. There is meaning, purpose, story, narrative. It is the human effort, in a way, that we come to art to give pieces of ourselves to a name. That we try to share, in this way. Art is telling. Art is there, and maybe it holds within it what we’re looking for, and maybe it doesn’t – but art knows us well enough to still be this extension, because it is us, it came from us, it continues to become us – but art is always there. It has always been there, from the very, very early days to right now, right this second, in this word, this syllable being written and being read. Art exists everywhere, because we know, that even when we look away, we are still looking, and in having art and beauty everywhere, in everything, it becomes a constant. Whether it is in the world of prestigious galleries, or even in our domestic everyday lives, art is always there, looking back.

Works Cited

“Art or Prank? | The Art Assignment | PBS Digital Studios.” YouTube, uploaded by The Art Assignment, 27 Jul., 2017. URL.

“Three Weeks in May by: Suzanne Lacy (1977).” YouTube, uploaded by LACE, 5 Feb. 2016. URL.

Berg, Beth. “Expanding Our Ideas of Art.” BlackBoard, 28 Aug. 2019.

Fraser, Andrea. “From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique,” New York: Sep 2005. Vol. 44, Iss. 1; pg. 278. URL.

Fromm, Erich. “Disobedience as a Phycological and Moral Problem.” On Disobedience and Other Essays, Harper & Row, 1981.

Art Cited

Parthenon, Athens Greece. 1978. Wikipedia. URL.

Duchamp, Marcel. In Advance of the Broken Arm. 1964. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. URL.

Weiwei, Ai. Sunflower Seeds. 2010. The Tate Modern, London. URL.

1 note

·

View note

Text

where is art?

Institutional critique is a movement that centers on highlighting the social and cultural circumstances, as well as surroundings, of the way art is presented in our society. It focuses on how the “site”, the position or place where you see a piece of art, can influence or impact the meaning of it. The way artists create pieces that fit within the institutional critique umbrella, according to writers Rebecca Seiferle and Lewis Church of The Art Story, is to create “site specific installations that emphasized the indeterminate and the temporal to question the financial, social, and cultural structure of the art world, and the systems of aesthetic evaluation that world employed.” (Seiferle)

Art historians have divided two main generations that have influenced and provided conceptual work under the label of institutional critique. The first having its origins in the 1960s and 70s, where they focused on museums and galleries as organizations, systems, companies that have their own interests and motivations. The second generation, associated with those in the late 1980s continuing to today, takes this focus and expands on it, taking on the addition of the relationship between the artist and the institution, as well as the meanings behind their motivations, both political, financial, and otherwise. (Seiferle)

Fred Wilson, a conceptual artist and trustee of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York city, is a current player in the realm of institutional critique. Much of his work revolves around the idea of self-awareness, for the problems and issues museums participate in when presenting their pieces of art. Wilson views museums as an idea, and that his place within it is “to be a kind of moral rudder in certain ways. To sort of think about why the institution is there, and what it does for the society, and just give the big picture as well as the specific picture of the museum.” (Whitney Stories)

Wilson is a key member of the current generation of artists who contribute to the institutional critique movement, like John Knight, Louise Lawler, Andrea Fraser, Carey Young, Renée Green, Amalia Mesa-Bains, and Barbara Bloom, who are more comfortable within the classification than their previous generation members. Their viewpoints center on how meaning within art throughout history, but especially now within conceptual art, constantly toes and crosses the line between art and politics, across the many different platforms and avenues of art. They argue that this isn’t something easy for museums to sell to their paying attendees, and sometimes it is about pointing out the flaws in the system that museums and galleries may profit from.

John Dewey, who wrote about the experience of art and the spaces that art is experienced in back in the early twentieth century, has a lot of ideas that still have weight and cohesion in today’s current art world. He believes that “art” is not the piece of work itself, but the product of the work and the experience one gets when interacting with it. He supports the unity of all different types of the worlds of art, whether that be traditional drawn or painted pieces, or things like music, or dance, or others. He believes that art shouldn’t be elevated into places like museums, because there they become separated from us, and the experience we have living alongside them is lost. (Art As Experience)

Traditional galleries and museums have many advantages. One being that they bring the world’s art and histories close to home. For those who cannot travel and go directly to cultures and various cities themselves, museums especially can bring the world close to home, for a substantially smaller price tag. In this way, museums create spaces that exist to chip away at the myths of things we create when we cannot see or experience for ourselves, histories we have not lived. It helps deny inaccuracies that may have taken commonplace meaning in our society. It widens perspectives.

But there are also many drawbacks to these spaces, as well. The biggest and most problematic of them is the fact that not all of these pieces have been acquired in an honest, or correct way. Many of the pieces being present in museum spaces, majorly, are the product of imperialism, or the loot of wars, or capitalistic decisions, among others reasons. In some ways art can become seen as pieces of stolen history that were taken, unjustly, and should be returned. Another drawback is the monetary value we place on the experience of going to places like museums or galleries. Some are free admission, on specific days or between specific hours, but most, overall, are pay to enter. Like this, we gate keep those who are not in the financial situation to be able to support extracurricular expenditures like visiting museums. This is a drawback, even if it is meant in the best interest of supporting the museum’s well-being, because it keeps those who may really benefit from the experience out.

A picture I took at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, which shows Rembrandt’s The Night Watch, presented amongst the humanistic architecture surrounding it, that was expertly planned and carried out. It shows mastery in both sculpture and atmosphere cultivation, an aesthetic that fits well into the idea we usually hold when we think of museums.

Personally, I love the idea of having a space dedicated specifically to the interaction and communication between people and art. Museums and galleries have the purpose of perspective given in them. You go, and visit, and if you are willing, you can come away a little different. It is a place that focuses on worldwide influences, and culture, and their specific ideals, how they differ from our own. A place like this takes us out of the routine of our daily lives and puts us into a new environment, invites us into a new mindspace, invites a different way of looking at the world around us, the world we live in.

Dewey’s idea that putting art into a space like this does separate and remove it from daily life, puts it on a pedestal, almost, is correct. It’s difficult not to think of art and not see pristinely painted walls, art in extravagant frames. It’s difficult not to see the price of museum tickets and exclusive memberships and overpriced café goods. In this way, a space like this becomes a privilege, the ability to go, to see these pieces, is one that some of us can’t afford. Is that really the idea of the spaces that we want to show, to cultivate? That not everyone is invited in?

It is easy to see all of this, and the rest of the political and elitist parts of the situation, and say that we should try to “fix the art world”. Like it’s easily done in a day. Like it isn’t such an incredibly interwoven part of our own. Like it’s its own special, separated piece of our society, one that can survive on its own, looked over by those with deep pockets and stay untouched by the people in our society that are only looking out for their own best interests, instead of the many, instead of the communities that these museums and galleries are situated in. Like it isn’t, in a way, an environment that is almost primed for the taking, instead of the back and forth, the take and the give.

Institutional critique, and the conceptual art within it, is an amazing presence who is taking this problem to task. It is the conversation starter, the questions that are posed because they have to be asked. It is the first step that makes others inspired, want to be involved, to become the next generation. It is the road that we will go down to a better world of art interaction and learning. It is the solution in progress.

If it were up to me, I’d try and make museums and galleries more approachable to those of all situations. Come in anytime, donate if you can. Maybe, if support is a big issue in the location of certain museums, we could put on raffles or tiers of donations to encourage donations like this, but in a way where don’t let it become a barrier.

In another way, I’d ask more questions specifically to the audience that museums aren’t reaching. I’d ask: what are you looking for? How do you get inspiration, and how do you believe we could model our museum experience to help you reach that? How do we convince a technological world that history and abstraction in art is important? How do say to people that it is in the willingness to try and understand that makes the experience of museums? That it is the interaction, the attempt at commonality amongst so many differences? That we have always been history repeating itself, building upon the ruins of our pasts and continuing the traditions, and how important it is to remember them? To continue them? To say their names?

Works Cited

“Art As Experience: Book Club #2 | The Art Assignment | PBS Digital Studios.” YouTube, uploaded by The Art Assignment, 14 May, 2015. URL.

“Whitney Stories: Fred Wilson.” YouTube, uploaded by Whitney Museum of American Art, 12 Dec. 2013, URL.

Seiferle, Rebecca and Lewis Church. “Institutional Critique Movement Overview and Analysis". The Art Story. The Art Story Foundation. 15 Jun. 2017. URL.

0 notes

Text

non-western art: teotihuacan + nazca cultures.

For this assignment, I chose to research Teotihuacan and Nazca cultural art.

teotihuacan, a mesoamerican metropolis.

Teotihuacan culture was based in a city of the same name, homed in Central America, about 50 kilometers (30 miles) northeast of modern day Mexico City. It is the largest pre-Columbian site in the Americas, and was the largest city in the entirety of the Western Hemisphere before the 1400s. It thrived for the first half of the first millennium A.D. Based on our best evidence today, we believe Teotihuacan to have been established around 150 BCE, lasting to about the middle of the 6th century. Nearly 200,000 people lived in the city at its peak. (Wikipedia)

Teotihuacan is, for nearly all parts considered, a ghost story. The city, a sprawling grid of over 30 km² (over 11½ square miles), was already in ruins, abandoned for nearly a thousand years before the Aztecs came upon it. So much of the Teotihuacanos is unknown: “they had no form of writing, so much of their politics, culture, and religion were lost or co-opted by later civilizations.” (Vance) Archaeological excavations have led to some recent significant discoveries; it is believed that sometime in the 7th or 8th century, the city was heavily burnt, seemingly by invaders, but recent findings shows that the damage was focused towards the structures of the elite were burnt, which leans towards convincing evidence of an uprising, but is still just a theory. (Wikipedia)

teotihuacan, in its prime.

From what we can see, and by what has been found, Teotihuacan is believed to have been home to a wide, diverse set of cultures, including Zapotec, Mixtec, Maya and Nahua distinctions, but this is still heavily debated.

Chief Curator of the Fowler Museum at UCLA, Matthew Robb, was the exhibition curator for the exhibition Teotihuacan: City of Water, City of Fire, at the de Young museum in San Francisco, in late 2017. When asked about how the art and culture of Teotihuacan invited new, diverse variety to the city, he said: “Not very many people in ancient Mesoamerica woke up and lived their lives in an apartment compound covered with interior wall paintings, but a lot of people in Teotihuacan did. And that’s just the murals—many compounds had small domestic altars, and certain kinds of stone sculptures were pervasive across all social levels. It was a materially and visually rich environment—there are even reduced-scale versions of vessels and objects included in burials.” (Gardiner)

At the time, Teotihuacan was a Mesoamerican metropolis. In its prime, the city was a bustling aspirational utopia of culture: the cultural, political, economic, and religious epicenter of ancient Mesoamerica. It was home to a visually rich environment, in more ways than just art. Houses had courtyards and drains, goods came from all around the city: minerals from the north, shells from the coast, jade from the Maya region. There were ball games and gambling, religious worshipping temples, many different types of food, various entertainments, it all made for a comfortable life to start thinking about bigger ideas than just survival. Teotihuacan was a shot at a better life for many people. (Moran)

teotihuacan architecture.

A Map of Teotihuacan, de Young Museum.

Architecturally, Teotihuacan contains a massive central road, thousands of residential compounds many pyramid-temples. We don’t know their true names, but we have those that the Aztecs gave them. The massive central road is known famously as the Street of the Dead, and the two main pyramid-temples are known as the Temple of the Sun and the Temple of the Moon. Even Teotihuacan is a given Aztec name, meaning "Place of the Gods”.

The grid layout of the city is incredibly organized and neat. The entire city is orientated 15.5 degrees East of true north. The main avenue, or the Street of the Dead, is massive, spanning 40 meters wide and 3.2 km long. (Teotihuacán) It spans from agricultural fields all the way towards the city’s main citadel, housing the pyramid-temple of the Sun, and culminating at the pyramid-temple of the Moon.

Temple of the Feathered Serpent, displaying "Tlaloc" (left) and feathered serpent (right) heads. Teotihuacan, Mexico, Mesoamerica.

Although it is the smallest of the three pyramid-temples along the Street of the Dead, the Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl (or the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, Quetzalcoatl), as well as its surrounding central plaza, are home to the greatest concentration of Teotihuacan’s sculptural and painted iconography. (Google Arts & Culture) Architectural sculpture attached to the temple are more than just decorative, displaying "Tlaloc" and feathered serpent heads. There are indents in the eyes for the placement of light-reflecting gems. It is believed that they suggest a strong ideological significance, but the significance itself remains highly debated. (Temple of the Feathered Serpent)

teotihuacan sculpture.

Mask, 4th–8th century, Teotihuacan, Mexico, Mesoamerica. Onyx marble (tecalli). The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Sculptures were varied, as there was no tradition of portraiture in Teotihuacan culture. Masks were made in this idealized style, we believe, to be a representation towards a status symbol, or towards a standardized art motif of the time. It is carved out of Onyx marble, a precious stone, and may have been painted at one point. Depressions in the eyes and mouth may suggest that they were once homes for inlaid shells, stones, or other precious stones. There are perforations on the sides, intending that the mask may have not been worn by people, but instead attached to further sculptures; human figures, mummies, or deity bundles. (Doyle)

teotihuacan paintings.

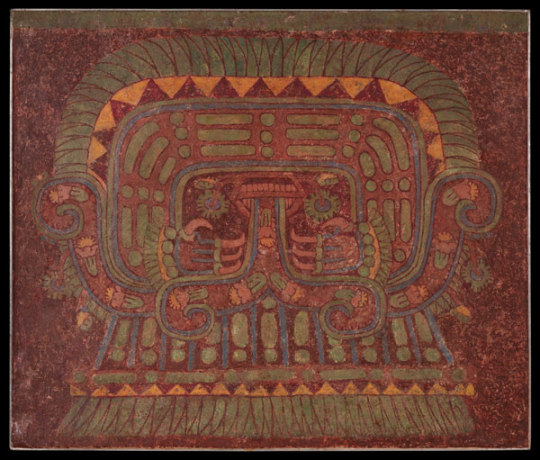

Wall painting, 7th–8th century. Teotihuacan, Mexico, Mesoamerica. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Paintings can be found everywhere in Teotihuacan culture: on walls, on statues, on various kinds of ceramics. The painting above, is an example of the many floor-to-ceiling murals that cover the walls of many of the high-status apartment compounds, frescoed murals depicting elaborate scenes and enigmatic iconography. (Doyle)

teotihuacan ceramics.

Vessel from Tlaxcala with procession of figures, 550–650 CE. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF).

Ceramics were a vivid, expressive venue of Teotihuacan art. Stylistically, the range of variety and high quality of painting and production showed mastery and expertise in the creation of ceramics: “Teotihuacan culture boasted a range of ceramic styles. Luxury ceramics could feature abstract figures rendered in vivid colors. There are also painted ceramics that are similar to frescoes, mold-made ceramics, very large and ornate multi-part incense burners, as well as architectural ceramics.” (Eiland)

contemporary references to teotihuacan.

Ralph Maradiaga Mini-Park, 24th & York. Mosaic sculpture, Colette Crutcher and Aileen Barr, 2010.

In San Francisco’s Mission District, various artists have paid homage to Teotihuacan culture. A mosaic sculpture done by artists Colette Crutcher and Aileen Barr, shows an interpretation of Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent god the Teotihuacanos worshipped.

The architecture of Teotihuacan can tell us so much about how the way we build our cities has evolved over time. Concepts like harmony, time-lasting material, and significance still have merit in our cities today. Look outside, see the way buildings are angled, or arched, or how high they climb in comparison to their surroundings and backdrops. The similarities are everywhere.

The Moon Pyramid and complex in Minecraft, de Young Museum.

The study and historical significance of Teotihuacan’s culture, architecture, and artwork of its diverse population is incredibly important. But not all of us can see it in our lifetimes, due to monetary restrictions or general life-work restrictions. Because of this, the exhibition curators at the de Young museum in San Francisco, California, made a 1:1 scale replication in Minecraft. The size, the scale, the recent discoveries, are all there for people worldwide to experience, with custom texture pack for a realistic representation of stone and artwork textures. Talk about incredible dedication and hard work to bring Teotihuacan to the world!

nazca culture.

Nazca civilization was homed in South America, near the coastal river valleys and high mountain basins of Peru. It flourished from about 100 BC to 800 AD. The style generally associated with the art of the Nazca – polychrome textiles, ceramics, architectural irrigation technologies – drew heavily from their contemporary, then-predecessors, the Andean society of Paracas.

The Nazca period was one of artistic flourishment and technological advancement. Religiously, the Nazca drew likely inspiration from their desert environment, beliefs based on agriculture and fertility. (Wikipedia) Many worshipped nature gods in favor of growth of crops and agriculture.

Politically, Nazca civilization was headed by a collection of chiefdoms, who worked both individually and collectively when the time called for it. There was no singular large-scale or integrated position of power. There was no centralized city. Instead, the overall population of about 25,000 people were spread across small villages. The Nazca were a state of the theocratic militaristic power sort, leadership often being those held in high qualification, usually priests and military leaders. (Cartwright)

Small cities of the Nazca civilization usually included many domestic amenities, including ceremonial mounds, walled courts, and terraced housing. It was also home to engineered aqueducts, including the Cantalloc Aqueducts, but there were more than 40 different built to ensure the supply of water to the city and to the surrounding agricultural fields, where cotton, beans, potatoes, and other crops grew. There were many opportunities in small cities for artisans, including ceramists, architects, weavers, astrologists, and musicians, to work for the leadership. Those who were not artisans, were usually farmers and fishermen, the fundamental base of the Nazca economical society. Pieces of pottery and textiles that have been found with resources originating far from Peruvian valleys (rainforest bird feathers, and mountain-homed alpaca and llama wool, etc.) serve as examples of evidence of trade with other cultures. (Cartwright)

nazca ceramics, goldsmithing, and textiles.

Curved Beaker with Rows of Abstract Masks and Geometric Motifs, 180 BC/500 AD. The Art Institute of Chicago.

The tradition of ceramics in Nazca culture was one of stunning high-quality polychrome pottery, with the use of eleven gradations of various colors in various pieces. Shapes included “double-spout bottles, bowls, cups, vases, effigy forms, and mythical creatures”. (Wikipedia) Pieces usually feature motifs, drawing from the environment, myth, religion, geometric, or deity representation.

Nazca ceramics were made before the use of wheels, and instead done by building coil walls up, then smoothing them out, before sometimes adding a smooth layer of soft clay for painting. Their reflective, smooth and shiny surfaces were made with the process of careful burnishing, or polishing/rubbing during the late drying stages. Many of the best-conserved examples we’ve found have been preserved in graves, buried with the mummified dead, either in dug graves or in tombs.

Nose Ornaments in the Form of Feline Whiskers, 180 BC/500 AD., The Art Institute of Chicago.

Gold and silver were also used in ceremonial and religious traditions, worn in the style of jewelry: masks, ear flaps, nose rings, or other adornments. To be worn they were flattened, cut, and embossed.

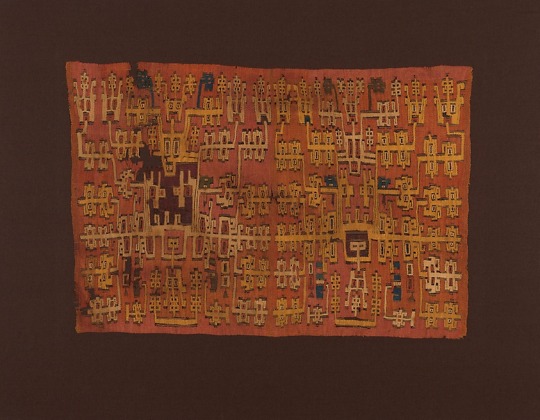

Panel, 500/600 AD, The Art Institute of Chicago.

Textiles were produced with cotton and wool, using techniques of muslin, brocading, tapestry, embroidery, painted cloth, and tridimensional weaving. Thread was dyed various different colors. Textiles, alike Nazca ceramics, usually portrayed themes, or motifs, worn for religious ceremonies or rituals. Excavations have found spindles, looms, needles, cotton, and pots of dyes at various Nazca sites. (Cartwright)

The panel above displays human-animal duality, portraying anthropomorphic abstract figures. The orientation can be shifted and still understood due to the range of horizontal symmetry. The many different heads featured are meant to signify supernatural, otherworldly powers, leaning towards this piece having ritualistic significance. (Art Institute of Chicago)

the nazca lines.

Of course, it is difficult to talk about Nazca culture, and not immediately turn to the famed Nazca lines; large geoglyphs seen only from an aerial vantage point, spanning over 50 miles, that have remained intact over the last 2000 years. The lines were made by clearing – with incredible detail – the red rocks of the Sechura (Nazca) desert, and exposing the greyish sand beneath. The geoglyphs are incredibly geometric, consisting of images that are of zoomorphic (animal-based) and phytomorphic (trees, flowers, etc.) shapes. (Bahadur)

The meaning of the lines has been heavily debated over the last handful of decades: leaning towards agricultural, to sacred rites for aquifers and springs, to astronomical and calendrical theories. National Geographic explorer Johan Reinhard summarized the versatile meaning of the lines in his book The Nazca Lines: A New Perspective on their Origin and Meaning: “No single evaluation proves a theory about the lines, but the combination of archaeology, ethnohistory, and anthropology builds a solid case.” (Reinhard) The way we see the world and our past continually adds onto itself, and with further research and a little bit of luck, we will hopefully find the origin and true meaning of the Nazca lines in the relative future.

Works Cited:

“Art and identity in the ancient city of Teotihuacan.” Gardiner Museum Blog, Gardiner Museum. 2018. URL.

“Teotihuacan, Mexico.” Google Arts and Culture, Google. Dec 2009. URL.

Bahadur, Tulika. “The Nazca Lines.” On Art and Aesthetics. eLucidAction. 8 May, 2016, URL.

Cartwright, Mark. “Nazca Civilization.” Ancient History Encyclopedia, Ancient History Encyclopedia Limited, 23 May 2014. URL.

Doyle, James. “The Arts of a Mesoamerican Metropolis, Here at the Met.” The Met, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 19 Nov. 2014. URL.

Eiland, Murray Lee. “Ceramics from the Birthplace of the Gods.” Ceramics Monthly, The Ceramic Arts Network, 8 Jan 2019. URL.

Moran, Barbara. “Lessons from Teo.” The Brink, Boston University, 6 Oct 2015. URL.

Reinhard, Johan. The Nazca Lines: A New Perspective on their Origin and Meaning. Editorial Los Pinos, 1986.

Vance, Erik. “An Homage to Teotihuacan.” Sapiens, Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, Inc. 5 July 2018. URL.

Wikipedia editors. “Temple of the Feathered Serpent, Teotihuacan.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia, 7 Sep. 2019. URL.

Wikipedia editors. “Teotihuacán.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia, 4 Sep. 2019. URL.

Wikipedia editors. “Nazca Culture.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia, 16 May 2019. URL.

Art Cited:

Curved Beaker with Rows of Abstract Masks and Geometric Motifs, 180 BC/500 AD. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago. URL.

Explore Teotihuacan at Home with Minecraft, de Young Museum. 21 Sep, 2017. URL.

Mask. 4th–8th century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. URL.

Mosaic sculpture, Colette Crutcher and Aileen Barr, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. URL.

Nose Ornaments in the Form of Feline Whiskers, 180 BC/500 AD., The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago. URL.

Panel, 500/600 A.D. The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago. URL.

The Sun Pyramid. Jorge Pérez de Lara Elías, Flickr. URL.

Vessel with Procession of Figures. 4th–8th century, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, San Francisco, California. URL.

0 notes

Text

field trip to the art institute.

I attended the Art Institute of Chicago on a rainy Sunday morning, full of possibility. It had just opened, and the hallways were open wide, some galleries completely empty. It felt like a place for retreat, a place to come and set down my responsibilities, my worries, my to-do list, and just exist, for a little while. To think, compare, and talk to myself, learn about myself – why did I like this piece? What about it draws me to it, what keeps my attention? How would someone go about making it, what is the process like? Learning about myself alongside learning about art, being in a place with artifacts and histories from around the world feels like cumulation of humanity under one roof. It’s beautiful, a little sad, and leaves me with many more questions than my curiosity has answers for.

Some of the pieces that caught my attention the most were of various different sorts, styles, and mediums.

Relief, Charles Green Shaw, 1937. The Art Institute of Chicago.

Relief, by Charles Green Shaw, was on view in one of the American Art galleries, next to other paintings and objects in glass cases. Yet it stuck out, looking like something more fitting towards the abstract galleries, with its shapes and pops of color, as well as the fact that it is made out of wood. Unlike its neighbors, Shaw’s piece is more than just paint on canvas, quite literally jumping out of the frame’s two-dimensional space. It was unlike anything else in the room, in the gallery, and I loved it.

Upon further research, I found that this work was inspired by Shaw’s challenge for himself, to create a piece of art that did not require a specific subject to provoke an aesthetic response from its audience. It is both painting and sculpture, within a frame. It meshes traditionalism with new age abstraction and conceptual efforts, and it amazes me – art that challenges and makes you question your initial reactions to art in general. (Shaw)

I’m including two pictures – one in neutral lighting from the Art Institute’s website, and another that I took in the gallery, where the light shining down onto the piece caused multiple shadows that made it look like the pieces themselves were vibrating. The piece is absolutely stunning, conceptually and visually.

The Landing Place, Hubert Robert, 1787-1788. The Art Institute of Chicago.

Hubert Robert’s The Landing Place is one piece in a collection of four colossal paintings that were a part of a commission to decorate a salon in the late eighteenth century. The size of it is the first thing you really see when you walk into the gallery – it’s nearly eight and a half feet tall by nearly seven and half feet wide. They take up almost a fourth of an entire gallery wall. Walking towards it, it feels more like a portal than a painting, the details and color so rich that you could step into it, and come out into the scene itself.

Something about the light of the gallery adds a golden-hued touch to the piece. The shadows seem more pronounced in their details, the direct light highlighted brighter. Like a more direct lighting approach that doesn’t quite copy itself to the online version, so I’m putting both pictures in here as well.

This was also the piece that I sat with for fifteen minutes for the Responsive Time Exercise.

It is the sky that pulls me in first, after looking up from starting my stopwatch. The contrast of light to dark, the clouds beckoning dusk, or daybreak, how people have already gathered together in this space in the early hours of the fabricated day. The canvas is stunning, in both scale and content. If I close my eyes to my surroundings, the painting’s scene feels incredibly real, like I'm there, the warm breeze and insects chirping, the light falling in, shading the structure, full of depth and scale.

I can’t seem to grasp the scale accurately in words – the painting must be twice my height, maybe a little over, how incredibly vast and wonder-filled this piece looks, how the people gathered all around are ants compared to the towering architecture, and how yet it makes them feel as if they are so alive, within their detailing. The boats. The texture of the water, the differences in clothes and colors and ages. It brings so many questions to light: who are they? Why have they come? Who are they meeting, and where are they going to go? Why have they come here, now, or is it then? Where is this place? What smell does the wind bring? How hot is the air?

Or maybe, there isn’t a story here at all. Or there are too many stories to be seen. Who built this place? Where did the materials come from? Why choose these pictures – is it a shrine? A place of knowledge? A place of peace? Why did Robert choose this scene, these types of locations for his patron? Reviving Hellenistic ideals? Is he trying to show calmness through scale? Peace through space and time? Domesticities and how history makes romantics of us all? How even the smallest of activities can be beautiful?

I’m now five minutes into the response, and I’ve come to decide that there are two versions of this painting - one version up close, and one far away. The entire piece is too big to really feel the scale up close, where the gallery’s lights reflect the texture of the brush used and the sky, the clouds, the colors, all disappear beneath the shine of it. Yet from afar, it almost seems like the scale is more striking. The color vibrates. The structure and framing of the scene seem to focus the lighting, the whole of the scene.

Up close, the details are in their full glory. There is nothing you cannot spot; wrinkles, shadows, texture and incredibly minute, small details you may have missed from afar. The woman peeking out behind the column to the right. The groups beyond the right-side gate. How they are together, or separated. The woman below catching the large boat from her own. The effort that Robert put into this piece, as well as his other three in the collection, isn't for even a moment half-hearted, nor half-hazardly detailed, every face has eyes, a nose, a specific look to them and only them. The statue has a dedication written on it. There are faces and further statues on the gates beyond. There is so much attention to lives that don’t even exist, the piece is overflowing with love and care. There is so much beauty in this piece, it strikes and never stops. It feels never ending, beauty upon beauty upon beauty – nature, architecture, humanity, domesticity. Once you see it, you can’t stop.

Ten minutes in, and surprisingly, I'm not yet tired of standing here, nor of this piece. It feels as if every time I look up there is something new to see, and maybe I’m cheating a little bit, choosing such a large piece, but it is everything I admire put in a painting. Parts history, humanity, domesticity, all under a rosy sky. The romanticism of everyday life, how it in itself is art. It leaves me wondering what the other people passing by are seeing. What are they drawn to first? What am I supposed to take away? What am I supposed to see, where am I supposed to look? Is it not subjectively, not entirely up to me? Aspects like shading and lighting can direct my eye, but the pieces that portray love and humanity – how am I to look away?

The detail is too much, now, almost, you feel too powerful, seeing everything. To be able to control this perspective of daily life. It feels unnatural, but real in the same tone. I want to hang it from my wall, peace and power and domesticity. I adore this piece because it feels like a memory, I've decided. Something rose-filmed but true, depending on how you see, where you look. Beauty, everywhere. So blatant, like it has nothing to hide, in everything, afar, close, in every step in-between.

I hadn’t planned out what pieces I was going to pick for the exercises beforehand, deciding on wanting to find them within the museum and being inspired, pulled towards them. I found one for the response exercise in the colossal pieces done by Robert, and found my secondary pick, for the criticism analysis, tucked into the Contemporary galleries on the second floor.

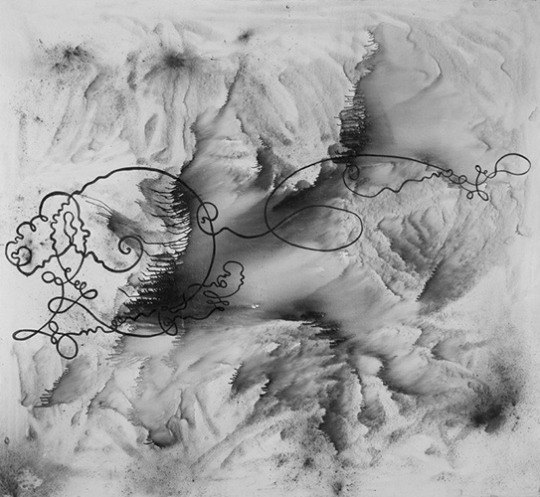

Velocitas – Firmitudo from the Dürer’s Loops series, Sigmar Polke, 1986. The Art Institute of Chicago.

Velocitas – Firmitudo is a graphite, silver oxide and damar resin made piece by Sigmar Polke in 1986. The plaque on the wall had no further background information. It was a mystery within the gallery, and one I wanted to piece apart and see if I could solve by analysis, so I chose it for the analysis exercise. Yet even before that, it stuck out to me, feeling almost like an mounted optical illusion – part topographical map, part three-dimensional treasure map, part story told through script, part picture of the sea taken from space – it felt like everything worldly poured down into one piece, in shades of grey. It looked like sand struck still on the canvas, inked and blown away to create dunes. How did one piece manage to convey so many different perspectives, so many images that I could list and list for what felt like forever? What was Polke thinking when creating this piece, this series? Why does it look like it will change, as soon as I look away?

It’s a fairly large piece – nearly eight feet wide by eight and a half feet tall – and is incredibly striking, for using only black and white for its range of color. It has many different textures on the underlying later, that look like they are overlaying themselves. There are thin ones, thicker edges, like mountain ranges of contrast. It is more sparse in activity around the edges, and then gets more intense the further to the center of the piece you look. Over the center of the piece is a black detailing. It looks to be two lines that intersect towards the center of themselves, and yet diverge greatly. The left is circular for most of it on the right, but on the left diverges into a looping, almost cursive-like detailing that twists and curves along and around itself. On the left it curves off to the opposite right side of the piece, a great curve leading to smaller details, looping in and around itself there as well.

The design elements this piece portrays are space, color, texture, form, and line. The line is the first thing that draws your attention into the piece. The dynamic dark blacks contrast the lighter greys in color, playing against the different textures. Some look to be almost splattered or spray-painted, others traced upon itself over and over until bleeding-edged and dark, others dripped down to look elongated and heavy in form. The space of the entire piece is enthralling, it is heavy in some places and blank entirely in others, a conundrum in itself. The design principles present in the piece are emphasis, balance, variety, and movement. The emphasis of the contrasting colors and textures. The balance in them as well, the whole piece looks equal on both sides, not one heavier than the other. The variety in textures, in shades, in the touch of elegance in the line symbol that adds movement to the piece. Polke has organized his work in almost diagonal quadrants, from range to range, the blurred darkness to the heavy edges to the lighter outlying edges of the entire piece. Your eye follows the line, at first, from left to right to back again, before it really sees beneath, and then gets stuck in the middle range of shading before following the rest of the piece up and counter-clockwise, before starting the whole process again and again.

This piece is stunning in its abstraction. It looks like it could be a list of things, and yet none of them at the same time. It’s chaotic, and yet looks like it has a central concept or meaning, due to the emphasis and contrast of its elements. It looks like it’s meant for you to get lost in. To turn over and over, to follow that line again and again like it will lead to some final message of the piece. I think that that is what Polke wants, this repetition, this losing of oneself in the piece. Every bit of design choice that I could figure leads to this – the variety and yet balance, the constant linearity of perpetual guessing– there is curiosity at the center of this piece, I believe. It’s what makes your eyes go for one last time around the piece, tracing the edges of darkest blacks one last time. Polke wants you to feel the textures, the question, the never-ending curiosity of it, with just your eyes.

Head of A Woman, Pablo Picasso, 1909. The Art Institute of Chicago.

The Institute’s collection loses me, sometimes, within the modern contemporary galleries. I understand that there is incredible technique and thought that goes into the creation of these pieces, and it’s not a technical issue that separates them from my eye. Sometimes, it feels as if there are just too many concepts at play and it overwhelms me, seeing them all crisscrossed across one another. Pieces, for example, like Picasso’s Head of a Woman, are technique-based of interest, but the visual aspect I find lacking. I don’t know if it is the color choices or the style, but overall, it just doesn’t end up appealing to me. I really do love many types of abstract and contemporary pieces, and yet some don’t connect with me. Though, they are easier to walk past in knowing that others love them as I love other pieces.

Water Drop, Mineo Mizuno, 2011. The Art Institute of Chicago.

The piece that affected me the most emotionally I actually stumbled upon, tucked away in the corner of one of the Asian Art galleries: Mineo Mizuno’s 2011 work Water Drop. Personally, I really don’t believe that the online photograph does this piece justice. Seeing it in person, it feels like you’ve just caught it mid-bounce, pressed pause right where it has flattened itself at its lowest point, right before springing back up again. There is weight to this motion, to the curve of it. It’s surface tension that never breaks, forever holding, existing, keeping. It gleams with a lost possibility.

This feeling was emphasized upon reading the wall description – it’s a personal piece. Mizuno dug his hands into the center of the piece, his fingers curving marks into the sides of hollow crater at the piece’s center. The Japanese character Mizuno has written all over the piece represents “zero”, “null”, “void”, or “nothingness”, as well as the title of Japanese World War II fighter planes. Mizuno’s father had died in the war before he was born, addressing that loss in this piece. The emotion of it is nearly tangible, palpable, like you are waiting for the return of motion, the bounce, the breath of life – but it never comes.

Art Cited:

Mizuno, Mineo. Water Drop. 2011. The Art Institute of Chicago. URL. Picasso, Pablo. Head of A Woman. 1909. The Art Institute of Chicago. URL. Polke, Sigmar. Velocitas – Firmitudo from the Dürer’s Loops series, 1986. The Art Institute of Chicago. URL. Robert, Hubert. The Landing Place. 1787-1788. The Art Institute of Chicago. URL. Shaw, Charles Green. Relief, 1937. The Art Institute of Chicago. URL.

0 notes

Text

art & craft.

Arts and crafts days were my favorite back in elementary school. They usually involved brightly colored paper and paint, or on other days scissors and glue, but we were always allowed to make a mess, make anything we wanted – and it was considered art (as well as masterpieces by our parents). The entire class, artists for the day. Today, when thinking about arts and crafts, this is still the image pulled into my mind. Safety scissors, dried glue stuck to desks, shreds of multi-colored paper everywhere. But when confronted with the term “fine art and craft”, the image immediately changes. Fine art, in the eyes of most of the western general population, is reserved for Picasso, DaVinci, Hokusai, as well as many others. It is not so much given to my overly-glued brightly-colored construction paper masterpieces. But where does that line definitively lie?

The difference between fine art and craft is blurry, and mostly subjective, making it very difficult to resolve or simplify. Fine art is usually the title given to pieces considered to be commissioned, individualistic, and made to be appreciated for their imaginative, aesthetic, or intellectual appeal. (Delacare, 2019) Where crafts, on the other hand, are pieces that are made with a utilitarian intent, for the purpose of being used; ranging from mugs, to rugs, to various household items we use on the daily, and have for thousands of years.

Crafts, originally, were built as a product of organized pursuits. Back in the late middle ages, the development of guilds led to the popularization of art and artists as we know them today. (Farber, 2012) Guilds are places where craftsmen and merchants would come together and create an organization for the production of goods, usually for the surrounding town or community. It was the action of working as a collective that these groups were able to gain authority and control over the production, standards, and marketing of a specific type of craft. With this, came economic and social boom for developing towns’ economies. (Farber, 2012) Working within the guilds held a strict set of guidelines that led journeymen and merchants to put in years of their lives and work into a craft’s practice to rise up well-defined ranks that led to mastery, as well as passing along the tradition of making a specific craft. (Morelli, 2014)

This model of group-based work continued until around the year 1400, when the line between art and craft began to form. Intellectuals of the time began the movement of Renaissance Humanism in Florence, Italy, which took ancient Greek and Roman works and ideas, and reconfigured them, focusing on highlighting individual creativity and reinvention. (Morelli, 2014) Until this point, many famous painters were court painters, who were hired and petitioned by wealthy patrons, who paid them usually by the square foot for their work. But after a few painters had successfully petitioned their patrons to pay them by merit, instead, it threw the guild traditions of working until accomplished mastery aside; skewing the public opinion of materials and their creators, raising that of painters, sculptors, and architects well above the rest, naming them specifically apart: artists. (Morelli, 2014) To those that still worked by guild traditions, and made more domestic objects – jewelry, cups, candlesticks, etc. – were separated, and named artisans, whose works were considered decorative, or minor compared to the works of artists. (Morelli, 2014) The distinction began then, and still persists today.

There are a selection of different sides to take in this centuries-long controversy. First, you could be one of the ones that bases their stake on the factor of intention: who made the piece, but more so why did they make it? Does the intention of creation change the piece itself? Someone who takes this perspective is Gareth Bate, curator of the Joshua Creek Heritage Art Centre, in Oakville, Ontario, Canada. When asked about this distinction between art and craft, he summarizes: “Craft for me is not art. Craft is making things mainly for commercial purposes, or from other people's patterns without an engagement with the history of art and the context of contemporary art. That does not devalue what is being made, but it is different. Any material or process can be used for art making, it is the purpose and intention that matters. Why are you making it and is it from a subjective perspective?” (Rudman, 2012)

Meanwhile, craft, to people like Mike Goldstein of Jerry’s Artarama’s YouTube series “Artist Problems” series, is a piece created by following directional instructions for that creation process. Intention doesn’t create the defining line, instead, it is within the mastery of a craft that creates art. To him, making a piece considered craft (aka. within a comfort zone) leads potential artists into the creation of individualistically creative art. His analogy for this process is: “Let’s say you like to cook a lot at home, and you follow recipes, but that doesn’t necessarily make you a chef. I think for that chef title … you should be writing the recipes … slowly figuring out the ways to make things work … creativity … inspiration … confidence … that risk taking factor … you want to try your own thing.” (Goldstein, 2017)

My opinion lies intermittently between these sides of the issue. I agree that all art is subjective, intent does direct the message communicated by a piece, and that craft predates the creation of art. But my view is also entirely different from these two directions, because in my eyes, the separation between art and craft is entirely unnecessary. You can’t have one without the other, they depend on each other’s constant participation.

Craft, in this argument, predates art and artists. How does one paint without first learning how? Because of this, everything is art. Crafts, fine, or otherwise, there isn’t a distinction by these descriptors. Pieces created with intention, with love, either fresh and new, or have history ingrained into the very process of making them, traditions left by generations and generations before us, should be considered as art. Even if it isn’t aesthetically pleasing. Even in today’s world, if a machine made it. If it is handmade, or mass manufactured. Does there have to be an intention brought to each individual part of a piece? Isn’t it enough to bring something to life, to create, as the intention behind everything, every piece? Doesn’t that constitute beauty? Doesn’t that make it all art?

I’m not saying that we cannot have descriptors and specific groups within art itself, as it already does – visual arts and textural arts and digital arts – the list goes on and on and I love every piece of it. Rather, I’m saying that there is no need to have this negative denomination for created pieces that aren’t showing mastery of a material. Any level of crafts are art. Basket weaving, embroidery, scrapbooking; there has to be a level of knowledge behind them to even be created in the first place. An eye for design, for creative intent. Even though some are made for monetary economic reasons, or used in our daily lives, just because something is considered a normal object, doesn’t make it any less deserving of its place within the category of art, or anything considered art enough to be hanging in a gallery or a museum. If a piece speaks to one person, inspires one person to dig deeper, to think or create or even breathe, then it is good enough to be art.

Chin-Chin, Caroline Achaintre, 2011. Courtesy Arcade, London.

Contemporary artists are making this distinction between art and craft harder to call everyday. Artist Caroline Achaintre works with all different types of typically designated “craft” materials, including textiles, woodcuts, ceramics, and watercolors. Her 2011 work “Chin-Chin” is a large-scale textile that includes many contradictions, pattern and texture-wise, but also conceptual contradictions, between “design and art, fashion and taste, abstraction and figuration.” (Tate, 2011) This combination of craft and the conceptual intentions of art exists on both sides of the line between fine art and craft.

Exhaltation, Zandile Ntobela, 2017.

The Ubuhle Art Collective was created to bring the tradition of bead-making to women of the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa, to preserve not only their livelihoods, but to bring to life once again the aspects of a lost cultural tradition. Zandile Ntobela’s piece “Exhaltation” shows an incredible mastery as well as individual creativity within her craft. Contemporary And explains the relationship between the tradition and craft brought to an audience: “Traditionally, the act of beading is a way for women to reach a divine state. Like streams of consciousness, allusions to water are woven in as subjects, and when on display, light subtly reflects off the surface of the glass beadwork giving the tableaux a sense of fluidity. For the viewer, the beaded objects express the artist’s spiritual power.” (Ubuhle Art Collective, 2018)

These pieces of tradition and history, the creation of works through this craft that has brought historic cultural traditions back to life again, are crucial to art history and cultural education. They should not be overlooked or deemed lesser for their craftsman roots. Instead, they should be raised on gallery walls, into history books, art books, theory. When art becomes accessible, it becomes seen, admired, inspiring. Who hasn’t seen a piece of art, craft or fine, and hasn’t been moved by it? Who hasn’t wanted to create right then and there, filled with inspiration? Who are we to define this line, to hold back future artists, future works? What kind of artists would that make us?

Works Cited: Delacare, Evangelyn. “What is Fine Art?” Canvas, Saatchi Art. URL. Farber, Allen. “Medieval Guilds and Craft Production”. Suny Oneonta. 2012. URL. Goldstein, Mike. “Artist Problems - Real Talk: Art vs Craft”. YouTube, uploaded by JerrysArtarama, Apr 21, 2017. URL.

Morelli, Laura. “Is there a difference between art and craft?” YouTube, uploaded by Ted-Ed, 6 Mar, 2014, URL.

Rudman, Dawne. “Gareth Bate, Interview | Curator of De Rerum Natura (On The Nature of Things).” World of Threads Festival, World of Threads, 2012. URL.

“Ubuhle Art Collective: Dreams Are Like Water”. C&, Contemporary And. 2018. URL.

Arts Cited: Achaintre, Caroline. Chin-Chin, 2011. Courtesy Arcade, London. URL. Ntobela, Zandile. Exhaltation, 2017. Ubuhle Beads. URL.

0 notes

Text

on beauty and art.

Marble busts. A clean, organized desk. Pastel colors, Baroque art. Listed, these items may not seem at first related, but they do in fact share a commonality: they are all different examples of aesthetics. Meaning: they are ideas, concepts, or items that all have a very specific appearance or style to them, that one may find enjoyable to experience. This could stem from the appearance of an object, to the history of it, the way it is made, or colored, or simply gleams in the light. The impact, or experience we receive from looking at one of these items or others, may have a certain aesthetic appeal to you, or others.

To grapple with the relationship between art and beauty is to grapple with how we go about seeing art, seeing the world. Asking the question what is art, what is beauty, can feel vulnerable. It tilts our worldview on an axis we aren’t always comfortable with. It questions how we view our reality, which can feel like standing on crumbling ground.

This is why, historically, “beautiful art” over the last few thousand years, before the nineteenth century, has meant objectivity. That beauty lies within the piece of art, in the harmony of its elements, the symmetry in its appearance, as well as the emotion expressed or conceived that made a piece beautiful. But this perspective changed in the nineteenth century, when Immanuel Kant and colleagues wrote that it is within judgement, within critique that beauty is found, relying on the subjectivity of the experience of art, as its audience, to find beauty. (Art Must Be Beautiful) This changed the game, leaning on audiences to find beauty rather than the objectivity of beauty from the art itself. Traditional western ideals have commonly attributed “beauty” to pieces that showcase incredible skill: landscapes, still life, portraits, where traditionalism and true-to-life, near-photographic styles, or examples of Realism, are favored.

The relationship of art and beauty dances on this line of objectivity and subjectivity. Some say that you cannot have one without the other, others saying that art can exist without having to be considered beautiful at all. In this argument, many bring up Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain. It is incredibly hard not to, the piece is incredibly controversial, and considers the arguments of beauty and art’s edges, the argument’s extremes. The title of Duchamp’s piece may remind one of the many majestic fountains from all over the world, with statues and architecture that is synonymous with traditional ideals of beauty. But the actuality of it is a little more every-day than, say, Florence’s Trevi Fountain.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917, replica 1964. Tate.

Pieces along this narrative are defined as “anti-art,” or art that defies existing expectations of what art is supposed to be. (Anti-Art, Tate) Here is where the relationship between art and beauty splits, depending on your own view of the discussion. To some, a urinal brought into a gallery may be called art, but it isn’t beautiful. To others, the message of what the action of bringing a urinal into a gallery means, makes the piece beautiful. There is another group, to who a urinal could just be beautiful. The architecture of it, all slopes and curvature, may be considered beauty and worthy of being art in itself, whether it is being shown in a gallery or bathroom.

This challenge of expectations, this split from the ideals of western traditionalism, was a curveball thrown into the history of art. What started as objectivity, symmetry and fractals, turned to subjectivity, as observers sought to define their own beauty in art. Changing again in the late nineteenth century, with the start of Expressionism rebelling against Impressionistic ideals and traditionalist art, where the likes of Vincent Van Gogh and Edvard Munch, among others, were famous for their Expressionist works, inspired by widespread anxiety of divergent views worldwide of authenticity and spirituality. (Wolf, 2019) Through Expressionism, beauty in art was shown through what was within, complex thought and processes, rather than from the current affairs of what the world had to offer.

Then, an explosion of radical and new age thinking in the early twentieth century. Movements like Surrealism, Bauhaus, Dada, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, among many, many others created as time went on. More artists were moving away from Realism and towards different ways of showing the world through a stylized lens, testing boundaries of meaning and definitions of what art is, what art could be.

These changes are attributed to the postwar culture left after the second World War. America having escaped generally unscathed, victorious of both a cultural and military war, among the millions of traumatized immigrants starting new lives far from their home countries. The culture that began of this mixing of ideals, of histories and cultures, jumpstarted a new age of movements every decade, one rebutting against the next. Art made in protest against elitism, against simplistic thought, against capitalism, against traditional limitations. (Willette, 2012) Like dominoes, one is the critique of the next, again and again. Old ideas turned on their head into new ones, beauty reinvented, revisited, over and over.

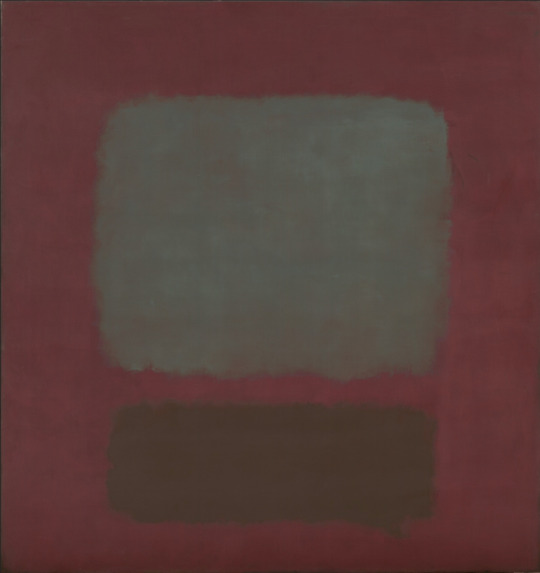

To talk about the change of art and beauty in art history and not mention the works of Mark Rothko would be a tragedy. Rothko’s works have been a centerpiece of abstraction and a spark to the discussion of art and beauty since their creation. His works are featured in museums around the globe, and have started a conversation of massive discontent and debate of beauty in the art world.

Mark Rothko, No. 37/No. 19 (Slate Blue and Brown on Plum) 1958. MOMA.

To many, Rothko’s works don’t feel beautiful when you first walk up and look at them. They may seem misleadingly simplistic. They may seem dull, rectangle upon rectangle of hazy dim color. But there is something about them that one cannot discount: there is a ubiquity present. Rothko’s pieces seem to loom over the gallery, viewers walking between them like they’re drowning in them, swimming from depth to depth. They are not pieces you forget it after you’ve walked away. Rothko didn’t need narrative to assist the color present in his works, an idea new in the 1950s, where having color, and color alone drew out emotion in audiences. (The Case for Mark Rothko, 2015) With this structure for his art, Rothko has said that: “‘he could deal with “human emotion; with the human drama, as much as I could possibly experience it.’ He said this style offered him ‘the elimination of all obstacles between the painter and the idea, and between the idea and the observer.’” (The Case for Mark Rothko, 2:02-2:13) This experience-based narrative that Rothko stood so strongly by – in my eyes, is the goal of beauty, down to the simplest, core concepts, of color and shape.

Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue is a series of four paintings by the late artist Barnett Newman (1905-1970). The third in the series, Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III, isn’t particularly groundbreaking at first glance, the same perspective as Rothko’s pieces showcase.

Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III, Barnett Newman, Stedelijk Museum.

The piece features an ocean of startling red, bracketed by vertical stripes on either side: blue on the left, and yellow on right. It is featured on a massive piece of canvas, nearly 18 feet wide by 8 feet tall. It hung in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam for seventeen years. Then, in 1986, it was murdered. It was actually murdered twice, within the timespan of about five years, but we’ll come back to that.

These pieces look similar because they are both connected by being created in the same style, that of the movement of art that began in the 1940s: Abstract Expressionism. This movement has a power that not all movements of art do: their presence alone enrages some viewers. The simplistic look of the paintings makes some feel like they, or even their children, could reproduce an exact-looking copy with little to no effort, compared to some of the other, more traditionally styled pieces featured in museums. This elicit and intense reaction from audiences goes so far to where some even leave museums entirely – vowing to never go back in. (99 Percent Invisible, 2019)

Abstract Expressionists are shaped by Surrealism, a movement known to have been created as a response to the global attitude shaped by post-war anxiety and fear and trauma. These artists vowed to explore art through self-expression, through color, and abstraction, and gestural emotion featured loud and proud on the canvas. (The Art Story Contributors, 2011) Some may say that these pieces should not be considered art, let alone carry the title of beautiful. But when we are grappling with the idea that we are capable, as a species, of such intense horror by our own hands, how do we go about making something like that – beautiful? How do we look at these faces, these beautiful landscapes, and not think of those who will never be able to see them again, or those who were never able, and will now never even get the chance? How do we hold that, and how can we capture it within art?

Beauty is constantly evolving, and not everyone is comfortable with that fact. But there is a difference in turning your nose up at modern art movements, and actively seeking out to destroy them. Here is where we come back to Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III, and it's unfortunate murders. The first begins when the painting is being exhibited at a museum called the Grande Parade, where it is being shown among other pieces to pose the question of what makes a painting, a painting. (99 Percent Invisible, 2019) During the exhibition, a man devastated the canvas, making long horizontal slashes with a box cutter. By the time he was finished, fifty feet of the fabric had been gouged out.

The man, Gerard Jan van Bladeren, was an artist himself. He considered this action one of artistic vandalism, where the painting itself was asking for it, that it provoked this action out of its audience, and he, the first to act upon it. (99 Percent Invisible, 2019) After, many Dutch citizens wrote to the museum letters of recognition, not for the fallen painting, but for the destroyer of it. “‘This so-called vandal should be made the director of modern museums’ read one. ‘He did what hundreds of thousands of us would have liked to do,’ read another.” (99 Percent Invisible, 2019)