Text

What does advertising contribute to politics?

“The constant personal attacks on Jeremy Corbyn may have actually backfired, generating sympathy for the Labour leader. He refused to respond in kind to the smears, lending him a certain nobility. He seemed brave and statesmanlike in the face of bullying from Tories and their supporters in the media. Furthermore, the constant attacks on his supposed links with terrorist organisations seemed far-fetched and overblown to the British public [...] the public are not stupid. They are not sitting passively, waiting to be fed their opinions by the Tory media. It is more nuanced than that.” Sam Delaney, 2017

What does advertising contribute to politics, according to Sam Delaney’s book ‘Mad Men and Bad Men: When British Politics Met Advertising’?

The best thing about this book is that it is consistent with its overall message – that politicians are forever indebted to admen for presenting their arguments in an easily tangible way. Although Delaney’s book is about a niche subject like creativity in politics, he omits the complicated jargon, the extended sentences with about 20 commas, dashes and colons between them and the overly descriptive flowery language which ends up being monotonous. Mad Men and Bad Men is filled with charming insights and interesting details - interspersed with gripping anecdotes. As a result, you do not feel like you are reading a book or watching a documentary. The book has the aura of a casual chat… where you just happen to learn a lot about politics and communication! Indeed, Delaney’s biggest achievement here is to turn a matter as tedious as political communications into a thoroughly spell-binding experience.

The crucial things we learn from this book are that firstly – politicians are indebted to the admen for enabling them to effectively communicate with voters and forcing them outside of the Westminster policy bubble. Secondly – advertising adds precision to campaigning strategies. The book raises questions of whether positive or negative advertising is more effective. Nonetheless, the downside to such surgical precision, is that parties can totally avoid issues they are perceived as weak on. I spoke to Sam Delaney about points raised in his book, with reference to the 2017 election.

1. Advertising enables politicians to communicate properly:

I. “Hamstrung by their own intelligence”:

In the chapter ‘People aren’t idiots’ Delaney points out that political types are “hamstrung by their own intelligence. The detail and intellectual rigour is all very well […] but you need an aggressive clarity, the sort of expert grasp of simplicity that great admen specialise in and great politicians are rubbish at”. For all the time intellectuals spend grasping abstract theories, they ultimately become hamstrung by their intelligence due to an inability to present this knowledge in a tangible way. This culminates in the futility of preaching to the already converted, whilst being perceived as self-important and swotty.

This is what makes politicians indebted to advertising agencies, as one of Saatchi and Saatchi’s founders (Jeremy Sinclair) says: “advertising disciplines force politicians to get to the heart of the policy, to deliver the key argument succinctly in a way people can understand. We helped politicians understand how to speak to people in a way they could hear.”

Advertising imposes discipline into politicians. There is a wonderful anecdote in the book about Labour’s 1979 election campaign. A commercials director (Sid Roberson) hired by the author’s uncle (Tim Delaney) to film TV broadcasts – told of how he interrupted the then-energy (Labour) minister Tony Benn’s speech;

“He’s just going on about all the oil produced and all this technical mumbo-jumbo, so I stopped him there and I said ‘Look, I’m just a punter, mate. I’m here to direct the film and it’s not my place to tell you what to say, but I am a voter. And you’re talking about a lot of [waffle] that nobody cares about, let me tell you. People know about their kids, their jobs, their health, but all this [waffle] you’re talking about is completely wasted on them. I know you’ve got your head up in it but I haven’t and nor has anybody else. If I were you, I wouldn’t say all of that”.

Where the politician was hamstrung by his intelligence, the advertisers enabled him to keep it simple.

II. Keeping it simple:

Keeping it simple is easier said than done. It is usually better done by the Tories than Labour. The juxtaposition between ad strategies is evident in Delaney’s description of Labour’s campaign of 1983: “dry and overly forensic in their explanation of policy […] preaching to the public about Keynesian economic theory which the average voter had little interest in”. By contrast, the likes of Tim Bell (now head of Bell Pottinger, a globally leading communications firm) and the Saatchis - perfected the art of the simple, concise messages which touched upon pre-existing voters fears and values.

Yet, in 2017 Theresa May’s simple, concise message of ‘Strong and Stable Leadership’ was not only a source of ridicule, but it also failed politically. Sam Delaney explained to me why;

“It didn’t tally with reality. In 2015 the message from the Tories was about a long term economic plan. They were five years in and had not deviated from the austerity programme. Ed Miliband seemed weak and memories of the 2008 economic crisis were still fresh in the public’s mind. The message hit home. George Osbourne and David Cameron appeared sensible and focused in comparison to Labour;s leadership. But in 2017, Theresa May spoke about being ‘strong and stable’ while refusing to engage in debates or with the public, dithering over her response to the terror attacks and performing u-turns on her manifesto pledges. Her actions and her rhetoric were at complete odds to each other. The British public could see that. In contrast, Corbyn was consistent in his actions and his rhetoric. Even if you didn’t agree with his positions, you began to respect him for his integrity.”

III. Out of the bubble:

Advertising forces politicians outside their Westminister policy bubble. The Tories learned this during William Hague’s leadership. For the 2001 election, they hired a small agency which did wonders for the party in Scotland. They did not care that the key figures of Yellow M advertising agency did not share their political convictions. After all, Labour had their campaign in 1983 run by Johnny Wright, a massive supporter of the party – this ideological attachment perhaps constraining them in properly targeting potential floating voters. Sam Delaney expanded to me on the importance of ideological detachment;

“I think what matters is a will to win. This requires a cold understanding of what motivates voters. The Tories have often tapped into the fears of voters, understanding that this is a key motivator. Labour have used supporters, committed ‘socialists’ who have a perhaps overly positive perception of human nature. They have more usually tried to appeal to the better nature of voters, attempting to win them over with rational arguments in support of their policies. Johnny Wright did this in 1983 with Shadow Ministers coming on TV to painstakingly explain the fundamentals of Keynesian economics. That is overly complex and boring to the average floating voter. Meanwhile, the Tories were making easily digestible and funny points about how close the Labour manifesto was to the Communist Parties’. That resonated much better with the British public. Labour teams have often been hamstrung by their own convictions - in that they can’t quite understand the perspective of people who don’t necessarily agree with them.”

In 2001, The Tories had the benefit of regular interactions with an ideologically detached agency. Yet they failed to listen to them when told to ignore the matter of Europe since it was only a big concern inside party ranks and a minor issue everywhere else. Labour comfortably won that election.

2. Advertising adds precision to campaigning strategy:

I. Precision:

When Labour recruited renowned American pollster Bob Worcester in their election campaigns, he told them that they only need to target 4% of the electorate. They already had a core vote they could rely on and the Tories had a similarly unshakeable core. Therefore, the election campaign needed to target, with precision, that 4% of the electorate in marginal seats.

The input of the advertising agencies may also influence party policy, as we learned through the struggles of Johnny Wright and Garnet Edwards during the 1983 Labour campaign, with the latter simply arguing that “the product wasn’t right” and therefore far harder to sell. By the next two elections – the ad agencies responsible for Labour’s campaign began to portray the leader Neil Kinnock as the unique selling point, understanding the toxicity of the party brand.

II. Negative vs. Positive campaigning?

Tory campaigning orthodoxy has usually been negative campaigning. Indeed, negative campaigning ultimately swung the 1992 election according to Delaney. After 11 years of Tory rule, they were widely expected to lose. Yet they just kept attacking Labour on tax, pouncing upon public fears that a Labour government would simply cost too much. Creatively, Saatchi’s devised a tax calculator based on the estimated costs of Shadow Chancellor’s John Smith’s spending plans – divided by British tax-payer revenue, so that you could see how much more tax you would pay under a Labour government according to your salary.

But negative campaigning only works when you have specific flaws to target. It failed for the Tories in 1997 (for more, see my video comparing Labour and Conservative election campaigns of 1997) because New Labour was an almost identical product to them. It did not help that there were contradictory messages on display. Tory campaign said that New Labour was copying them (see the party political broadcast ‘a tree without roots’) whilst simultaneously saying that they were dangerous. By contrast, New Labour’s campaign was very positive. The ‘Things can only get better’ video captured the vibe of the Britpop era wonderfully, whereas the fly-on-the-wall documentary style displaying Tony Blair’s normality worked splendidly.

20 years later, The Tories negative campaign on Jeremy Corbyn also failed. Sam Delaney explained to me why;

“Fear of the other side is what ordinarily works. But you can’t go too far with that. In 1992 the Tories made some very effective attacks on Labour’s tax plans. They made sense and tapped in to the pre-existing instincts of the electorate. But in 2017, the constant personal attacks on Jeremy Corbyn may have actually backfired, generating sympathy for the Labour leader. He refused to respond in kind to the smears, lending him a certain nobility. He seemed brave and statesmanlike in the face of bullying from Tories and their supporters in the media. Furthermore, the constant attacks on his supposed links with terrorist organisations seemed far-fetched and overblown to the British public. In 1992, the Tory campaign made a measured and calculated attack about Labour tax plans, something that the public were already suspicious about. But in 2017, they made attacks that seemed wild and didn’t quite tap into a practical or existing fear. You can’t start the fear in the public’s mind. You have to find out the fear that is already there and exploit it. Lastly, the incessant negativity from the Tories in 2017, twinned with empty and receptive soundbites about being ‘strong and stable,’ suggested that the government were devoid of ideas and complement about victory. The public are not stupid. They are not sitting passively, waiting to be fed their opinions by the Tory media. It is more nuanced than that.”

III. Issue avoidance:

But is it neccesarily good the amount of precision that advertising adds to campaigning strategy? We saw above how parties are advised to not really bother with the other team’s core voters. They fear spreading themselves too thin, so the orthodoxy is to focus on the 4% in marginal seats. Precision can also lead to issue avoidance. Dick Worthing, a political consultant and election guru behind Ronald Reagan’s election wins – advised Tory director of communications for 1992 (Shaun Woodward) to simply not fall into the bait of talking about health. The justification for this is that the Tories are already perceived as weak on it, so it is best to totally avoid.

Worthing devised the most important election campaign diagram. He would draw a vertical line with the top labelled positive rating and the bottom labelled negative rating. Then a horizontal line, with the right labelled high salience and the left labelled low salience. Then, both of the parties policies would be filled in accordingly. The result was a campaign strategy which emphasized the positive rating and high salience issues of the Tories (like economic management and defense), whilst totally ignoring negative rating and high salience issues (like health, which Labour had positive ratings for). In addition, they would attack Labour on their negative rating for high salience issues (like economic management and tax).

Of course, this is a strategy devised by those who want to win by any means. The Tories continue to neglect discussions on health and public services. Could it be the reason why the Tories have not won a majority for so long? I asked Delaney if it is wise to keep dodging questions on public priorities:

“I think framing the debate is still very important and, yes, the government should of course use their advantageous position to frame it around the subjects on which they are strong. It is harder to do nowadays because of the proliferation of outlets. Social media in particular is difficult for spin doctors to manipulate. In the past it was about giving a speech in the morning, getting it picked up by the Today programme and then by three or four papers. Now there is a sprawling mass of media outlets writing whatever the hell they like so it is much harder to keep the debate under control and within narrow confines of your choosing.”

3. Conclusions:

· Politicians are hamstrung by their own intelligence, they need the advertising, marketing and communications people to keep it simple for them, ensuring, that their messages do not fall on deaf ears.

· Simple, concise messages usually work best. In 2017, Theresa May’s ‘Strong and Stable Leadership’ soundbite failed because people could see that it was inconsistent with the campaign.

· Advertising forces politicians into professional interactions outside of their policy bubble. Unlike their constituents, these are people who advise them, as opposed to complain to them.

· Advertising adds precisions to political campaigns, to the extent of influencing policy. Politics is like a business, with its own target markets and unique selling points.

· Negative campaigning usually works – but only if it exploits pre-existing fears. As Jeremy Corbyn’s exceeding of expectations in 2017 showed – fear cannot be manufactured and smearing can work in the oppositions favour.

· The orthodoxy of issue avoidance is no longer feasible in the social media era. Westminister no longer controls what is discussed. Tory reluctance to discuss public priorities like health can be damaging to their image in the long-run.

Written by Yassin M. Yassin, with many thanks to Sam Delaney for taking time out to talk to me. You can get his awesome book here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Mad-Men-Bad-Happened-Advertising/dp/0571312381

0 notes

Photo

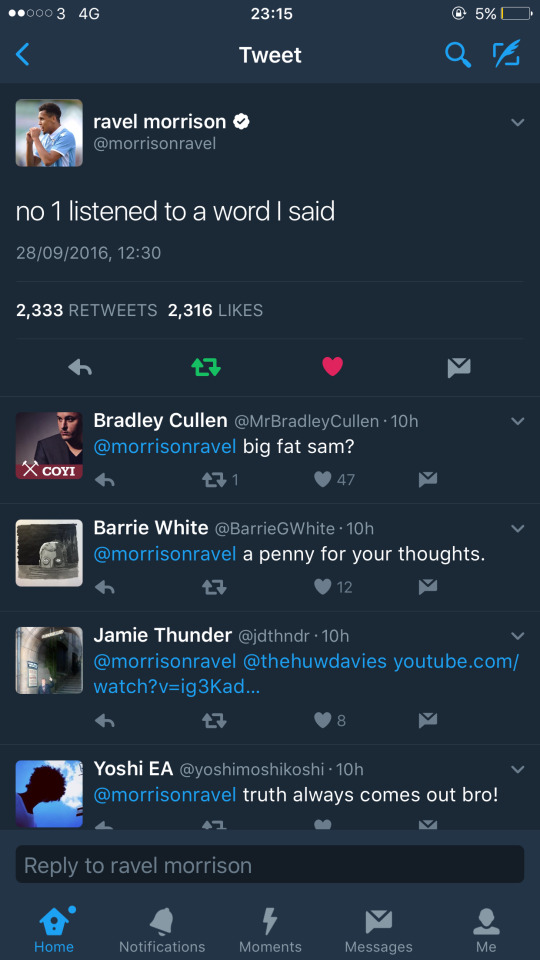

DONT JUDGE A BOOK BY ITS COVER: Who has read 'To Kill a Mockingbird'? From Harper Lee's iconic book we learned that we should not judge a book by its cover. But unlike Tom Robinson, Ra'vel Morrison (like so many young black men) did not have an Atticus Finch to defend him from the heinous activity he was wrongly accused of. Sam Allardyce's public humiliation is evidence that what goes around, comes around. If you are bad person, the past will eventually catch up with you. Allardyce's selfishness and greed cost him his dream job as England manager. In 2014, these despicable traits essentially cost Ra'vel Morrison his career. Ra'vel's story is no fairytale. Raised in the biggest (possibly roughest) council estate in Europe (Wythenshawe) in a single parent home. An atmosphere of poverty, gun and knife crime and drugs. His route out of the struggle was his football. Snapped up by England's best academy (Manchester United's) before puberty, he was head and shoulders above the rest in his age group and the best schoolboy in England. Having watched him since he was 15, I remember when he was in United's famous 2011 youth team with Pogba, Keane and Lingard. Ra'vel was the best player on that team by a country mile. Yet 5 years later, Pogba is the most expensive player ever, Lingard has scored winning goals in cup finals and Ra'vel is stranded in an Italian B team struggling to get 5 minutes on the pitch. So, what went wrong? Rav simply could not shake of his 'Bad-boy' tag. The lad was only a product of his environment. The media saw the slit eyebrows, the scrunched up face when he talks, the shortening of vowel sounds in his speech, the bopping style of walking, social media group pictures of him with his friends (who were deemed to be criminals just because they had their hoods up, although they were all legit)... The media decided that Rav wanted to be a a gangster more than a footballer. When Rav was charged with assault it was decided that he was a violent man. The media purposely ignores that fact that in UK law, assault is an action where the victim is expecting violent physical contact. If the violent physical contact occurred, he would be charged with battery, GBH or ABH. If anything Rav, was just like any other 18 year old. Stayed up late playing too much Fifa and arrived to training late. On the pitch I never saw him lose his temper. Unfortunately, his reputation preceded him, through no fault of his own. Let us be honest: just look how the English media romanticised the white bad-boys. Lee Bowyer failed a drugs test, charged with a racist hate crime and fought his own team mate on the pitch but nobody questioned his attitude. Paul Gascoigne drank like a fish but he was a sob-story. Jack Wilshere is caught smoking and is incapable of keeping his temper. Not to mention Robbie Fowler's hedonism, Steven Gerrard's violent crimes, Jonathan Woodgate's racial crimes, Frank Lampard mocking 9/11 victims, Paul Merson drug and alcohol addictions, Tony Adams' alcoholism...of course for them it is 'boys will be boys'. Because they are white. Yet Raheem Sterling cheated on his Mrs and there was national public outcry, not to mention rumours that he has fathered 7 children by the age of 21! Andy Cole released a song video and supposedly it proved that he was more focused on glamour than football. Why can't the 'boys will be boys' privilege be extended to black players? Ra'vel's time at United was cut short and by 2012 he was sent down south to London to join West Ham. Apparently he needed a change of scenery. To get away from his "dodgy friends" 🙄. Given his opportunity by Sam Allardyce, Rav was immediately West Ham's best player and almost single handledly transformed the fortunes of that club. A memorable moment was his spectacular solo goal to cap off a man of the match performance for him, and 3-0 victory for the Hammers at the home of their huge rival Tottenham. Seemingly, Ra'vel was on the road to fulfilling to potential. Within 4 months of this, Ra'vel was shipped out on loan to QPR in the division below. After a short spell at Cardiff in the same division, Rav was released from West Ham and by the time he went to Italy in 2015, he had not played a minute of football in almost a year. So, what went wrong? Sam Allardyce, and his most trusted players, had been pressuring Ravel to get rid of his agent and take up the Allardyce's and senior players' agent (Mark Curtis). Rav refused. His then agent was more like the father figure he never had and was trusted. We can only speculate on why Allardyce wanted Rav to join Curtis' agency, but it pissed him off enough to banish his best player to the B team and then ship him off to QPR and Cardiff (in the latter move, auditors found unexplained transactions which raise questions of if Allardyce took a bribe). When Ravel complained, nobody listened to him. Why? Because it was Ravel saying it. His reputation preceded him. But this was not the only way that Allardyce destroyed Ravel's career. In that same period, Ravel wanted to join Fulham. An ideal move for him, as they were then-managed by Rav's old youth team coach at Man United; Renee Muelensteen. Allardyce blocked it and threatened legal action against Fulham for allegedly harassing Rav(!) - a claim with no foundation When Ravel complained, nobody listened to him. Why? Because it was Ravel saying it. His reputation preceded him. In conclusion - I want to tell you the real pisstake about this whole situation. Allardyce has been exposed and accused of corruption and greed before. Back in 2006, he was part of a Panorama investigation about bribery in football. And yet people still believed this cunning, corrupt, despicable, vile, arrogant, shameless, thieving, greedy bastard - who tried to destroy a black teenagers career before it even began...over the boy who is too innocent and not articulate enough to adequately defend himself, who is portrayed as everything that is wrong with society just because he looks, dresses and talks in an unfamiliar way!

0 notes

Text

Israel tells the US, Europe to improve relations with Sudan

"Even the Catholics in Ireland have received more love, respect & solidarity than Sudan despite not contributing a. SINGLE. FLIPPING. THING. to the Palestinian struggle" For those of you bemused by my very un-SOAS political views, after you read this you will understand. For the I.R students who want to understand political realism. In particular you will understand my dislike for any sort of utopian ideology and my love for pragmatism. This is great news; not only the prospect of the crippling sanctions being lifted from Sudan, leading to more investment in shaa Allah and our potential as a nation may finally be fulfilled after decades of regression and a globally unmatched brain-drain. Indeed, this whole process began when - out of desperation and in dire need of investment - Omar al-Bashir ended relations with Iran and committed troops to the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen. Immediately, Sudan was re-integrating into the Arab world's diplomatic community after years of self-isolation. Instant results followed - all the investment that Lebanon used to receive was taken away from them and given to us and Saudi Arabia invested heavily in our agricultural sector. Sudan's golden age in modern history was itself a result of pragmatism. Under the stewardship of the supposedly secular, socialist leader Gaafar Al-Nimery, our global reputation reached its peak. Firstly, our reputation in the global language of sports gave us a presence on the international stage which culminated in the legendary Liverpool team of the 70s (best team in Europe back then) playing a friendly in Sudan. Secondly, our reputable academic institutions, where the British curriculum had been kept on even after independence, saw Sudanese people fill up professional sectors all over the world. We also modernised and helped to build the infrastructures of the newly oil-rich Gulf Arab who had all this money but a still majority uneducated population who did not know how to use it. Thirdly, the Sudanese culture and the arts had a global presence. Our literature, poetry and music were appreciated all over the Arab world and Africa (for example, contemporary musicians like al-Balabil, Mohammed Wardi & Abdul-Kareem Kabli were very well known). The author Tayeb Salih had even made it in the West! Of course, at this time, Sudanese international trade was among Africa's strongest and the tourism industry benefitted also. This was not a result of secularism nor socialism. Nimeiry claimed to be socialist, just like all the other post-colonial African & Arab dictators did in order to gain public support. In reality, banks were privatised and foreign investment/ownership was highly encouraged. He claimed to be secular to appease the Christians in the South but allowed Islam to dominate the public sphere in the North. In foreign policy, 'socialist' Sudan leaned towards the West in the Cold War and benefitted from this immensely in economic terms. When the majority of Arab leaders boycotted Egypt's half-Sudanese leader Anwar al-Sadat for ending the war with Israel - Nimeiry stood with Sadat and understood his diplomatic vision (of course, if Sadat wasn't black we all know that Arabs would rate him more BUT THATS NONE OF MY BUSINESS🐸) After Nimery, Sudan loses its pragmatism. It takes a strong anti-Western foreign policy. We see sanctions. Isolation from the diplomatic community. A huge brain-drain. Constant negative coverage on the news. Outbreaks of diseases. Food and water shortages. Sudan goes from Africa's bread-basket to a charity case! Sudan decides that it wants to please the Arabs. A lot of anti-Western, anti-Zionist imperial rhetorical follows. Sudan becomes an arm-smuggling route for Hamas in the fight for liberation against Israel. Gets itself bombed 6 times in the process losing a minimum of 140 lives. Where was the heroic adoration for Sudanese martyrs? Where were the Sudanese murals in the Arab world? Where are the songs for Sudan? Even the Catholics in Ireland have received more love, respect & solidarity than Sudan despite not contributing a. SINGLE. F***ING. THING. to the Palestinian struggle. And how ironic it is now that Israel is supporting our progress. Because when certain people get away with murder in the Muslim world, it is always blamed on some zionist, imperial conspiracy. Just look at the hands of Iran in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen...claiming to liberate al-Quds yet oppressing other Muslims. Hezbollah and Assad starving innocent people yet claiming to be a resistance vanguard against the Zionist. Israel has simply become a convenient excuse for vile regimes to carry out their villainous work and claim that the purpose is to free Palestine! (Make lots of duah for the Palestinians and as for the Israeli regime...leave them to Allah. His plan is greater than the dunya) As you all know, I LOVE Sudan deeply. With all my heart. And as you also know, when I LOVE something - I want everybody to love it/them as much as I do. Of course, its easy to do this with say Manchester United or my adopted countries... but with Sudan...it's a lot harder. The country has been a laughing stock, a JOKE - to almost everyone except actual Sudanese people... How can I promote a country that is only in the news for negative reasons? This global humiliation is best represented in a very weak tourism industry DESPITE housing the majority of the world's pyramids and the River Nile. So I summarise everything very simply, using my love for Sudan as a guide. Idealism fails us. You can try to please and speak for the people all you like - but they will never care about you or your well-being. Just look how many countries toned down their anti-Israel rhetoric when they realised that it doesn't benefit their own or Palestine's security. But when you have a pragmatic manner...you understand that first you must guarantee your own security. Then, and only then, can you begin to think about the security and well-being of others. The national interest for now is financial well-being.

0 notes

Text

Thatcher's revolution: how Britain became economically great again

Part 1: Why we benefit from Margaret Thatcher’s reforms: a short history of the turbulent British economy from 1918-90 When Margaret Thatcher inherited a turbulent British economy characterised by industrial unrest, she was faced with a behemoth task of modernising and radically reforming a horribly inefficient system. Part 1 examines not only what she did – but also WHY she had to do it, starting with the aftermath of WW1. In part 2 – we look at the implications of Thatcherism. Whereas it had mixed results for the white working-class (particularly males), the social revolution and the enhanced mobility had greater results for immigrants and their children, especially in educational attainment. This essay is 4,630 words long. The first 3 chapters offer context. If you want to get straight to the juicy, skip to chapters 4 and 5 - they are about 2,000 words. Nonetheless, I would advise you to go on this journey through time. 1. Post-World War 1 Industrial Unrest: The British manufacturing industries were failing since 1918. Thatcher’s shift of emphasis from manufacturing to the service (finance, education, arts etc.) sector turned Britain from the ‘Sick man of Europe’ to the economic superpower she is today. In other words, she shifted emphasis from what were bad at, to what we were good at. In this section, we will see the roots of why the manufacturing industries were failing. The war effort meant that mines were nationalised, meaning guaranteed wages and controlled prices regardless of the market. After the war, privatisation was back and wages went down as prices and profits went up, culminating in Clydeside shipbuilders & engineers going on strike, with the Miners Federation threatening to following to suit unless demands for a 6 hour day, 30% wages increase and nationalisation were not met. The industrial unrest was exacerbated by disillusionment of fighting in the trenches and news of the Bolshevik revolution in Russia inspiring workers to empower themselves. To make matters worse, the economic problems of 1921 followed. After a severe slump threw 1m off work, the rising cost of unemployment benefits – which were originally meant to be self-sustaining, funded by the employed/previously employed’s tax contributions – was running into debt. The year before, Liberal Prime Minister David Lloyd George, in his eagerness to maintain his image as a working-class hero increased unemployment by 8s a month. Back then, you only got unemployment benefits 15 weeks a year and only if you had contributed to the money pot before. But the 1921 Unemployment Act meant that you got benefits for 2 15 week periods in the year, with one where contribution was mandatory and the other was non-contributory. Rising unemployment (as well as its cost) were a result of Britain’s declining industries as a result of a drastic fall in exports. Firstly, the textile industry was dying because our previous biggest customer India began to develop its own internal industry. Secondly, there were more efficient rival shipyard in Japan, the USA, Scandinavia and the Netherlands. Thirdly, and most importantly, the coal industry was beginning to show why it would become the biggest burden on British domestic politics. Contrary to popular belief, Mrs. Thatcher would not shut the mines down because she was an evil witch who wanted widespread unemployment – it was a necessary measure to take for a horribly inefficient industry and we will see why: • As gas and oil rose to prominence as fuel sources, coal declined. By 1939 – half of the world’s ships ran on oil • At the time, France and Italy who previously relied heavily on British coal imports, were receiving free coal from Germany as war reparations. • Dutch and Polish coal mines were more efficient and highly mechanised compared to British ones which were too small and expensive to run. The government was reluctant to subsidise funds for modernisation. • By 1925 80% of our coal was picked by hand. The tons of coal exported fell drastically from 73m in 1913, 60m in 1925 and then 39m in 1932. Falling profits were blamed on workers lack of productivity and this led to the General Strike of 1926 The 20s ended with the 1929 Wall Street Collapse. American overproduction left us with a much smaller marker to export to and as a result, exports fell to 1/3rd of 1928 levels, with 23% of insured workers unemployed. This would end up destroying and splitting the Labour Party led by Ramsey MacDonald, who had now replaced the Liberals as Britain’s second party. The events that unfolded are crucial to our analysis of British political and economic history. It is a history that has continued to repeat itself and explains why a dogmatically socialist, far-left Labour party is unelectable in Britain (hence the concerns about Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership today). Theoretically speaking, a Labour government elected with a comfortable majority should have the agency to enact socialist economic reforms. In practice, they are subject to the structure of the global finance system. Ramsey Mac and his Chancellor Snowden, despite Liberal and Labour parliamentary support for radical solutions such as the Moseley Memorandum (bulk purchase from dominions, import restrictions, government control of banks to allow credit, pensions at 60 & school leaving age raised to 16) and Keynesian economics (raise spending during hard times to create jobs and get industry going) – were forced to stick to the orthodox practice of cutting spending during hard times. The Sir George May Committee predicted a £120m balance of payments deficit by 1931, suggesting 20% cut of unemployment benefits and public sector spending. The government’s hand was forces by the banks insistence that they would not lend unless there were 10% cuts. With Labour and Liberals divided over 56m cut in public spending, Cabinet only approved the cuts by 9 to 11 – Ramsey Mac resigned and went into the 30s as part of coalition national government with Stanley Baldwin calling the shots behind the scenes. Nonetheless, having gained the establishments trust by gaining a £3,750m loan from the USA after WW2 (with only 2% interest) – the economist John Maynard Keynes finally got his economic ideas put into practice. As successive governments in the 20s failed to nationalise and mine-owners refused to modernise, 80% of coal was still picked by hand, which meant miners had to face longer hours with less wages. Furthermore, with the pounds being overvalued by the then-Chancellor Winston Churchill(!), exports became more expensive. The country was the grips of a stubborn battle. The mine-owners had no intention to modernise, fearing it would lead to over-production, nor introduce a national wage rate. The miners refused to accept wage reductions. Shipmen, dockers and other manual labourers all struck in support of the miners and the country was brought to a standstill. Although PM Stanley Baldwin eventually held out and the unions surrendered – the bad-blood between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat was stronger than ever. This was just the beginning of awkward industrial relations and history would repeat itself, as we would see in the 70s where the unions wrestled economic power from the government. 2. The 30s: The beginning of the North-South divide As we will examine in further detail later on, when Mrs. Thatcher had to pull the plug on the life support machine which barely kept alive the breathing carcass that was the British manufacturing industries – this pain was disproportionately felt in Wales, the North of England and Scotland where employment prospects were heavily reliant on the survival of these industries. The widespread closure of coal-mines are the reason for Thatcher’s image as heartless neoliberal economist who destroyed so many people’s livelihoods. But it must be remembered that although the Thatcher’s Conservatives lost more and more seats in those regions – she had the unprecedented achievement of 3 consecutive election wins. This would not have been possible if not for how her reforms were welcomed in the less industrialised Midlands and South of England. In reality, the North-South divide was not a result of Thatcher’s shift of emphasis from manufacturing to the service sector – it was brewing since the 30s, where the Midlands and the South led the way in Britain’s emerging service consumer economy. In other words, British prosperity in the 30s was not thinly spread. Although, unemployment came down from 3m in 1932-3 to 2m in 1935 & 1.4m in 1938, it was the Midlands & South benefitting from new industries such as car manufacturing (indeed car ownership doubled in the 30s). The economic slump of the late 20s meant that everything was cheaper; leading to a boom in consumer goods & leisure; radios, cars, cinema outings, seaside holiday resorts etc and also lead to improvements in diets. By contrast, prosperity did not come to the North where the old staple industries were located. Popular literature such as Orwell's Road to Wigan Pier described the plight of long-term unemployment who were depressed, emasculated and forgot their skills. In Northern towns, there was 20% unemployment on average, higher infant mortality rates and widespread of people suffering from diseases such as rickets & TB. Famously, people from a town in the North-East named Jarrow (where 68% were unemployed) went on a hunger march to London. Of course, such factors would culminate in the problem of structural unemployment in the North – which would remain a consistent part of British economic history and indeed tarnished Mrs. Thatcher’s legacy. Ironically, the dawning realistic prospect of World War 2 was the best thing that could have happened to the North – since the war effort not only required full employment but have workers more bargaining rights when demanding high wages and price controls. 3. Post-WW2: Nationalisation and further industrial decline After the War, there was a great appetite for socialism and nationalisation. Despite the war being won by the Conservative Winston Churchill, it was the socialist Clement Attlee with his manifesto pledge to enact the historic Beveridge Report (which culminated in free education, healthcare and housing) won the post-War election in 1945. The country was keen to learn from the post-WW1 mistakes and wanted to preserve the national unity the war created. However, according to some historians – the welfare state was implemented prematurely when emphasis should been directed towards rebuilding roads, infrastructure and declining industries, eventually making it a burden on British economic growth. Nonetheless, Britain’s economy was in tatters – leading to Britain being labelled ‘the sick man of Europe’. Successive governments could not prevent gold reserves plummeting to 3m at the end of the war (from 864m!), because the war interrupted overseas trade meaning that we had to dig into gold reserves to pay for food and raw materials. Having grown reliant on aid for the USA, the government could not foresee Truman’s abrupt ending of ‘Lease-Lend’. This meant that our foreign investments were sold off and our capacity to export drastically curtailed. Moreover, we would have trouble converting factories to peace-time productions – with these matters combining to ensure that the USA advanced into our former markets. Nationalisation also had mixed results as a solution to declining industries. On one hand, government control of gas & electric meant that prices were standardised & government control of bank made lending easier. Yet on the other hand, both ends of the political spectrum criticised it. The right-wing felt that coal mines were too big for government control and that the iron and steel industries were too profitable to need it. The left-wing felt that, first, previous owners were paid out excessively (mine-owners 164m, steel-owners 240m), meaning that there was a lack of money needed for investment & modernisation. Secondly, the same inefficient management was kept on meaning that these industries ended up costing the government more to prop up than they benefitted from controlling. After a period of brief stability during the ‘Swinging Sixties’ – the conditions created in the immediate post-war period such as – the inefficiency of manufacturing industries due to the security of nationalisation reducing competitiveness at a time when not only was there less demand for our manufactured imports, but also superpowers the USA and USSR advancing into our markets – on top of the burden of the costly ‘cradle to grave’ welfare system and a growing population. Nationalisation had enabled the trade unions which grew more militant and more radically communist, no doubt inspired by the Soviet model of socialism which was dominating Eastern Europe and the vastly popular Labour Party. This left Britain in a situation whereby it was not clear if it was the government who controlled the nation, or the unions. 4. The 70s – The final straw Britain was an ungovernable nation in this decade with the unions bringing Britain to an absolute standstill. They grabbed the country by the metaphoric boll*cks, with the premierships of Ted Heath (Tory), Harold Wilson & ‘Sunny Jim’ Callaghan (both Labour) all being marred by industrial unrest – which in the end destroyed and divided both parties. Despite a tanked economy and a severe balance of payments deficit, the unions wage increase demands not only continued, but continued to rise. The country had enough of the militancy and eventually, by 1979 – Margaret Thatcher was elected upon the promise to destroy the sense of entitlement and dependence on the state. A sign of how chaotic this era was – Mrs. Thatcher resonated with the British people despite the fact that there were questions over her ability to command authority (especially as a female that was routinely destroyed in Prime Minister’s Questions by her male Labour counterparts). On top of that – her adherence to ‘every man for himself/survival of the fittest’ neo-liberal economics was distrusted even among large sections of her own party who were more inclined towards their greatest leaders Disraeli, Baldwin, Macmillian (set the pace for the stability of the 60s) and her predecessor Ted Heath’s compassionate, socially responsible One Nation brand of conservatism. Ultimately, it was the 1978-79 ‘Winter of Discontent’ which was the final straw in British economic turbulence and industrial unrest. At the start of the decade, Tory PM Ted Heath had to battle the National Union of Miners who previously moderated wage demands but had now came under influence of communists like Mick McGahey. The 14% demand in increases came when inflation was at 7%. Causes of inflation included; the Vietnam war which led to deprecation of the dollar which impacted the international export trade. The ‘Barber Boom’, a measure by the then-Chancellor which intended to stimulate the economy by cutting tax and interest rate lead to increased borrowing and rising house prices, as well as the change of currency to the decimal system which took coins such as the half-crown (12.5p) out of circulation. Inflation was further increased after prices increased 9% between 71-73 as industrial earnings increased 14% without the productivity to justify it. The miners victory in 1972 inspired more industries to strike and press for further wage increases, a battle which would continue and intensify throughout the decade between government and unions. The aftermath of the Arab-Israeli War which led to OPEC Arab countries uncompromisingly high oil prices (punishing the West for their support for Israel), created hope for the miners as the demand for coal increased. Inadvertently, it only proved how inefficient the industry was. The fuel shortage led to the 3-day-week. Although productivity was cut by 40%, only 5% output fell. This was proof that the mining industry was a burden. After Heath came Wilson again, this time lacking in energy, with a growing fondness for brandy and unable to lead. He had no energy to battle miners the miners. The unions destroyed and caused internal division in both of the main parties, with quick-fire midterm elections as a result of ‘no confidence’ votes and inflation rose to 27%. The combination of economic and political instability caused shares to tumble as foreigners withdrew money, with the FTSE index falling from 554 to 146 between 1972-74. Living standards were falling for the first time in 40 years, the atmosphere of an ungovernable nation in the midst of a tug of war between striking unions and their militant socialist leaders and elected officials was best summarised in a 1974 satirical Daily Mail cartoon which illustrated families led by brown men in turbans jumping off banana boats with their luggage into the British island, with white men in white doctors jackets and notepads telling the immigrants “No we're not police - we're psychiatrists”. These immigrants were seen as literally crazy for assuming that they can have a better life in such a turbulent Britain. Especially one where the militant communist Arthur Scargill had the most influence of the unions. After the miners forces a 32% wage increase, the domino effect followed and other workers began to strike for more. ‘Sunny Jim’ Callaghan’s premiership began with absolute humiliation in 1976 – with Britain asking for a loan from the IMF(!) – bear in mind the IMF is known for handing out loans to Third World economies in the developing world. With rising unemployment came rising taxes to pay for the welfare state and nationalised industries constant wage increased. For reference, in 1949 a man would escape income tax if married with kids on average income. In 1976, a man earning half of that had to pay tax). Although inflation came down to 16%, perhaps as a result of the £6 a week maximum wage increase – the interest rate was 15%, with the pound sliding downwards. With a 1bn balance of payments deficit, the IMF offered the 3bn loan on the conditionality of 2bn spending cuts. Naturally, Labour lost support and Callaghan was portrayed as a sell-out and bourgeoisie capitalist exploiter by the far-left. Statistically speaking, union power was so strong that half of the 26m workforce was unionised. Their ability to mobilise with such ease lead to the greatest turning-point in British economic history – the winter of discontent. After Sunny Jim tried to pass 5% pay increase limit, the unions rejected this. Demands for a £20 pay rise at Ford, mean that got 17% wage increase after going on strike. Firemen did the same and got 20%, and the nationwide lorry strike mean that they got 20% too. The domino effect was underway and soon public sector workers like those employed by the NHS, dustmen and even grave diggers went on strike. The rubbish pile up by February was so extreme that it was feared to be a health-hazard. Streets were literally covered in rubbish from pavements to blocked roads. Iconic images such Leicester Square being used as a rubbish tip were the final straw. The Tory lead in opinion polls shot up 20 percent because Sunny Jim’s 5% limit failed. Margaret Thatcher was comfortably elected in 1979. 5. Margaret Thatcher’s Revolution Whether you love her or loath her, Mrs. Thatcher’s economic reforms transformed Britain from the ‘sick man of Europe’ into a free-market model that set the benchmark for the world. And she was revolutionary. For her, the state did not have the answer to the economic woes…the state was the problem, itself! She was a neo-liberal, a revivalist movement inspired by the likes of Hayek and Friedman. Whereas modern liberalism wanted to use the state as a weapon to increase the liberty and life-choices of the less fortunate (for example, William Beveridge whose report inspired Clement Attlee’s welfare state was a modern liberal), classic liberalism viewed the state as the biggest infringer on a citizens personal liberty. The 19th century philosopher Herbert Spencer (who it can be argued is the real father of neoliberalism) took this idea to the logical extreme and argued that humankind is stuck in a Social Darwinist, survival of the fittest battle among itself. This clearly inspired Thatcher and those who inspired her, who felt that the state should be absolved of social responsibility. Famously, Thatcher remarked: “there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families. And no government can do anything[…], people must look to themselves first. It's our duty to look after ourselves […]People have got the entitlements too much in mind, without the obligations. There's no such thing as entitlement, unless someone has first met an obligation.” This brand of personal responsibility was new to the Conservative Party. Indeed, it was common knowledge that the (relevant) Tory Prime Minister’s before her (Heath and MacMillian) intensely disagreed with her beliefs. Back then, One Nation conservatism had a monopoly on the party, a compassionate, socially responsible form of the philosophy which encouraged community cohesion and solidarity (even if it was only to preserve order, stability and to protect itself from a socialist revolution). Neo-liberal Thatcherism was a massive risk, which proudly neglected social responsibility. So, would it work? Mrs. Thatcher inherited an economy in tatters that had to endure the humiliation of taking out a loan from the IMF and falling living standards - by the time Thatcher left office, London overtook Tokyo and New York as the world’s financial capital. Moreover, British wealth per head had eclipsed Italy, then France and finally Germany. The game plan was simple: to switch Britain’s emphasis from what were terrible at (the manufacturing industries which created such economic and political stability without the efficiency to back to back it up), and starting to focus on what we were good at – the service sector (financial services, arts, education etc.). Of course, Thatcher could not achieve this without breaking many hearts, especially in the North and Scotland where inefficient manufacturing industries were still a burden. Privatisation intended to put these industries into efficiency by exposing them to the competitive market and cutting national industry subsidies caused mass unemployment, leading to whole areas being either deindustrialised or the ones that remained so, faced devastatingly high amounts of redundancy. This was social darwinist, survival of the fittest neo-liberal economics in its practical form – if the trade you were skilled in could no longer pay you, you were expected to gain a new skill and enter a trade that did pay. Thatcher’s ideological guide and political mentor Keith Joseph was tasked with reforming the manufacturing industries as Secretary of State for Industry, and arguably the privatisation and subsidy cuts paid off. In 1979, Joseph inherited a nationalised British Steel Corporation that was losing £7m a week. Having set about closing inefficient plants which cost 50k jobs in the process, Joseph had to compromise on the 2% wage increase limit (it was raised to 16%) although even more jobs were lost in the process. By 1981, the British Steel industry was the most efficient in Europe – a drastic turnaround from the laughing stock it was before that. Thatcher’s first term also saw the unpopular economic practice of monetarism; inspired by Milton Friedman, being put into practice for the first time. It was a radical proposal and a massive risk, a huge departure (in fact, the polar opposite of) the Keynesian consensus of raising spending during hard-times to stimulate the economy was substituted. The signs that Keynesian economics was failed was clear to see – during the economically disastrous 70s: taxes, wages and state spending (especially on the welfare state) continued to rise despite huge unemployment and unprofitable industries – matters which only ensured that inflation and interest rates rose. Monetarism intended to control the supply of money as a means of controlling inflation. Not only did this mean cutting tax, subsidies and social spending – but also raising VAT which made prices more expensive and interest rates to ensure that borrowing was harder. Naturally, it hit the poorer hardest, especially when so many were made redundant and benefits were cut. Yet by the time the policy ended in 1982, it was successful – as evident in Thatcher’s 1983 election victory. Thatcher’s election victory was aided by the extreme unelectability of the radical far-left Labour Party led by Michael Foot. They had their lowest election performance since 1918, with only 27% of the vote, although they had 209 seats in the North and Scotland where Thatcher and Joseph’s reforms were crippling. This was a true illustration of the North-South divide we outlined in the second party of this essay – the South benefitted from the development of high tech industries and the growingly profitable service sector. Nonetheless, we must not forget that among Thatcher’s comfortable 142 seat majority was 31% of the union vote and an extremely large loyal base from the aspirational working-class. There are a combination of reasons for this; firstly, Labour were unelectable: they had grown even more left-wing and their slavish attachments to full nationalisation and the militant unions which wreaked havoc in the 70s did not sit well with the electorate – let alone their calls for nuclear disarmament at a time when the Cold War was threatening to heat up, and desires to withdraw from NATO and ally Britain with the faltering USSR. Secondly, the low taxes offered to those who succeed provided a great incentive to be ambitious and entrepreneurial, while the benefit cuts and price increased created an equal disincentive to be reliant on the state. All in all, inflation was falling and growth was rising for the first time in a decade. With Labour’s unelectability ensuring that Thatcher had a free mandate to enact neoliberal economic reforms in her second term, she pressed ahead with the closure of the mines. The Great Miners Strike of 1984-85 is the key incident that tarnished Thatcher’s legacy and ensured that she is such a marmite Prime Minister. The closure of uneconomic pits and cutting of subsidies from inefficient industries was the practice of rolling back the state. Privatisation created an enterprise culture as the improvement of business efficiency was put down to their placement in the competitive market. Soon, only 20% of industry was in state hands and this was falling. Revenues not only increased, but unions were weakened. Where the government raised £1bn for the sale of nationalised companies in 1983, this was raised to 7.1bn by 1989. Thatcher’s legacy beyond the economic revolution was the social revolution. The reason why she gained consistent loyalty from the aspirational working-class were the social mobility opportunties offered and the lower taxation that came as a rewarding incentive. The stock market was reformed and deregulated to give more people access to it, so more and more of the population had share (seared above France and Germany). The Right2Buy scheme meant that people could now buy their council house, with 1m taking up that offer in the 80s. The trade union electorate fell 8% from 39% and in the 1988 budget, income tax was reduced: 25% at the standard rate, 40% at the top. Britain had now went from taking out loans from the IMF to the financial centre of the world in the space of 11 years. Thatcher won her 3rd election in 1987 with 42.3% of the vote. She held onto power for 3 more years until ousted by her fellow MPs, although these were for personal reasons. A ridiculously hard-working woman who slept 4 hours a day, with such a memory that she did not need papers in-front of her during Cabinet meetings – she was slowly falling to dementia. Now we have completed the journey of Britain’s turbulent economic history – we summarise it like this: the demand for what the manufacturing industries were producing was frittering away and becoming burdensome since just after WW1. After WW2, with global superpowers advancing into Britain’s former manufacturing markets – the nations source of prosperity came from the South which focused on services. The troubles of the 70s proved exactly why giving in to union demands for wage increases was bothersome: money does not grow on trees, especially not for unprofitable industries. Regardless of the amount of jobs they created, the government bankrupted itself and had to embarrassingly take out a loan from the IMF because nobody was buying the manufactured commodities. In many ways the North-South divide also exemplified how neoliberalism disproportionately benefited the rich. However, as Thatcher and later the modern liberal John Rawls who influenced Tony Blair’s New Labour economic policy (which would have been unprecedented in winning 3 consecutive elections if not for Thatcher herself) argued – the growing gaping chasm between rich and poor should not be a problem if the overall living standards of the poor increase. In part 2 – we intend to look at the implications of Thatcherism today. Yassin M. Yassin

0 notes

Link

0 notes