Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Total Exit: on the Queer Cinema

(Basis for introductory remarks given at QFFxBQFF screening ‘Burning Ones’ at the IMA, March 8, 2018. )

Already, by the 1940s, the feeling was that the cinema had become “a medium of and for bankers,” that the time had passed in which a film could be both commercial and artistic, both public and personal. (Renan 18) Doubly constrained by market concerns and the 1930 Hays code (which forbade depictions of more than thirty unsavoury topics including interracial relationships, childbirth, sexual deviance and mockery of the church), the Hollywood studio system mastered the endless reproduction of tepid, escapist fantasies sure to appease audiences and censors alike. At its peak, the studio system churned out more than five hundred such features every year—and individual screenwriters, directors and actors working in that system understood well that they were replaceable, at a moment’s notice, if they threatened to disrupt either the consistency of the product or the relentless speed of the process.

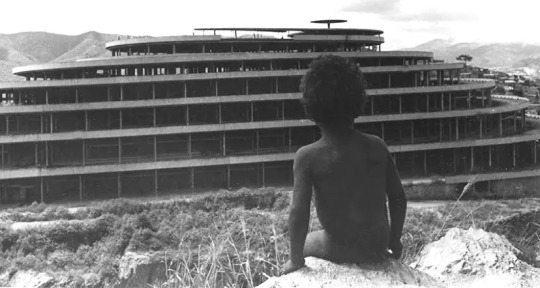

Against this stultifying current emerged the underground cinema: a loose, international affiliation of artists working totally outside and in opposition to the studio’s production-distribution-exhibition machine. Where Hollywood had perfected filmmaking as the output of a bland and homogenous product, the underground sought to challenge every preconception of what a film could be, to be both radically personal and fearlessly experimental, and to explore any and every idea and subject deemed unfit for public consumption. Underground films could be twenty seconds or twenty hours long, narrative or abstract. Images could be traditionally shot, painted or scribbled right onto the stock. They could re-appropriate footage from other films, advertisements and newsreels; they could even mock the church. In a postwar society that had veered sharply conservative, the underground cinema acted as both a venue and method for exploring new ideas and questioning societal norms without fear of public persecution.

It is no surprise then, that while the movement began as a small group of artists making and screening films almost exclusively for one another, it quickly attracted those whose identities, sexualities, loves, ideas, class or politics excluded them from mainstream representation and mainstream society alike. By the 1950s, the underground had become a vital space, not only for artists to seek new forms of self-expression, but as a meeting place for queers and commies of all kinds—one of the few spaces which permitted open communication, the exchange of ideas and phone numbers, experimentation, exploration and transgression, both on-screen and off-. The commercial film epitomised the double-ideology of the “normal person” and the “normal story”, each reinforcing the other in a perpetual, closed loop. In their works, the underground sought to break entirely from this vicious circle, and it is this exigence of total flight to which all three films on tonight’s program respond.

In Jean Genet’s ‘Song of Love’, a prison guard cruises a dark, one might say mazelike hallway, spying on the prisoners’ various displays physical and sexual release. But there is one prisoner in particular whom the guard truly desires, and his voyeuristic pleasure sours into jealousy when he realises the prisoner yearns for someone else. Two fantasies—the prisoner’s and the guard’s—bleed into one another as the guard bursts into the cell and lashes the prisoner in an ecstatic outburst in which lust and hatred, acknowledgement and punishment become indistinguishable.

For Genet, as is well known, the criminal, poet and homosexual are but a single figure: the prisoners communicate their desires in their own language of smoke of flowers. Though they are physically confined, they exude an unrestrained sexuality in every frame of the film. In Genet’s world, it is the guard, which is to say the state, who wields all the power and yet remains impotent, who cannot join the prisoners. Unable to reconcile his contradictory desires, he (the guard) is the one finally expelled from the prisoners’ erotic liminal space.

Gregory Markopoulos was one of the earliest filmmakers to take up love between men as an explicit and enduring theme. While it is true that his films are intensely personal—so much so that he tried at one point to withdraw them from circulation entirely—their autobiographical details are fragmented, disturbed by, as Renan puts it, “[an] editing technique that obliterate[s] the plot if one [does] not know it.” (87) Even when, as in Swain, Markopoulos draws directly from a literary text, story remains subservient to an almost phenomenological method which conveys above all the experience of queer desire. At a time when homosexual experiences and encounters could exist only in marginal spaces, fleeting moments and coded signals, Markopolous’s films likewise remain hidden in plain sight, unfolding in a discontinuous style in which his characters’ pasts and presents, thoughts, fears and fantasies intermingle. We find in them a yearning for an impossible domesticity—a tranquility shattered, over and over, by intrusive memories and images that spill over the screen almost faster than the eye can catch.

Jack Smith’s ‘Flaming Creatures’ has a history of obscenity trials, clandestine screenings, police raids and arrests so extensive that it would overshadow perhaps any other film. When a Belgian film festival declared it an undeniable aesthetic achievement and banned it from screening in the same sentence, a friend of Smith’s smuggled the film into the country and held packed screenings in his hotel room. When the film had likewise been banned in New York, a vigilante projectionist at a commercial theatre, barricaded himself in his booth and screened the film for as long as he could before authorities cut off power to the entire building. (Benshoff 120)

‘Flaming Creatures’s polarising influence, its history both of outraged suppression and equally fervent support, is well-deserved. Structurally, visually, and thematically, it has almost no precedent. Made a year before Sontag’s famous essay, ‘Flaming Creatures’ was one of the first films to consciously develop what we now call ’camp’, and at the same time pushed that aesthetic further than perhaps any other film since. The result is a shocking farce; kitschy and obscene, consciously—almost studiously—opposed to every dictum of good taste. Visually, it is a pastiche of rococo, orientalist, drag and B-movie aesthetics: humans of utterly ambiguous gender identity frolic about in kimonos, flapper dresses and ball gowns, costume jewellery and tumescent prosthetic noses. Their activities reach a screaming, orgiastic climax until an apocalyptic earthquake kills them all. Then, the whole thing happens again.

In his own life and writings, Smith opposed not only the white, hetero-patriarchal establishment but the so-called ‘assimilationist’ LGBT intellectuals, who argued that the only path to mainstream acceptance was meek compliance with the mainstream status quo. Smith, by contrast, saw quote-unquote normalcy as a restrictive and repressive ideology which should be resisted and lampooned in every possible respect. ‘Flaming Creatures’ is a free and irreverant fuck-you to every preconception, expectation and standard of good taste. It is structurally and visually disorienting, a confounding and ridiculous nightmare, which nonetheless harbours a kind of utopian vision: the film’s characters are truly “creatures” as the title implies—without gender, without boundaries, existing beyond even life and death. Smith himself said of the film that he wanted to explore every conception of beauty, and, once we have acclimated to its style, the film offers just that: a joyous affirmation of both the glamorous and the tacky, of every kind of body, of cheap wigs and jiggly dicks.

Queer popular culture still echoes the innovations of the underground, in its gleeful mockery of conventional gender signifiers, for instance, or in its embrace of camp as a rejection of academic distinctions between ‘high’ and ‘low culture’, or ’serious’ and ‘silly’ art. Yet, as exemplified by RuPaul earlier this week, the ultimate triumph of the assimilationist agenda over the underground’s rejectionist project has come at the cost of a reabsorption of mainstream hegemony into the queer world, and a recodification of social and sexual roles in a community that once strictly opposed performative roles of every kind: As Rees-Roberts argues, “‘Images’ of mainstream integration,“ have disproportionately favoured “conventional, straight-acting, young, white, middle-class gay boys, [reinforcing social hierarchies of] LGBT identities, racial difference, gender inequality, [and] economic privilege.” (1-2) Much of queer cinema, like much of queer culture, has likewise acquiesced to mainstream standards of normalcy and acceptability, but in exchange for an acceptance which is not offered equally to all.

What the underground filmmakers understood, what has often been obscured in subsequent, audience-friendly depictions of safe, queer love, was the urgent need of resistance to the prevailing status quo and all of its social, political, intellectual and economic mechanisms of control. The films come from a time when to be queer already meant to be an intellectual and political adversary of the state; to be experimental or personal as a filmmaker already meant to oppose the monolithic, monopolistic and moralising Hollywood system. The queer underground grasped clearly that, in every case, it is one voice which divides titillation from transgression, the aesthetic from the abhorrent, which in one decree states what is good, what is moral, what is legal and what will sell; one voice which sings the song of a tasteful society of progress and progeny. In the underground there emerged against this voice another one of total dissent, a break so radical that it still eclipses much of what has come since. Here, artists imagined utopian futures which have not yet come to pass, and, if we have truly abandoned the ceaseless critique of our own present, perhaps never will.

Cited:

Benshoff, Harry and Sean Griffin. Queer Images: A History of Gay And Lesbian Film In America. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield 2006.

Rees-Roberts, Nick. French Queer Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP 2008.

Renan, Sheldon. An Introduction To The American Underground Film. New York: Dutton 1967.

4 notes

·

View notes