Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Loxodromes, Part 1

Loxodromes (also known as rhumb lines) are a family of curves on the sphere . The family includes meridians (lines of constant longitude) and parallels (lines of constant latitude). The general loxodrome is a spherical spiral which intersects every meridian at the same angle. These curves are useful for navigation, because they describe the idealised course followed by a ship that maintains a constant compass bearing.

The navigator and scientist Thomas Harriot was an early investigator of the loxodrome; he was the first to rectify it (find a mathematical expression for its length) and among the first to rectify any curve. I'm planning to make another post about his method (based on a description in Robin Arianrhod's biography of him). First, though, I'm going to try to give an account of the loxodrome using modern calculus. (I'm leaning on a pretty good treatment on the atractor.pt website.)

The task of deriving the formula for the loxodrome is made much easier by having the right mathematical tools. In this case, the tools are the notion of a parameterised space curve, a vector-valued function, spherical polar coordinates, Cartesian coordinates, and basic differential and integral calculus.

A space curve, parameterised by the variable \(t\), is a function \(\gamma:\,I\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^{3}\), where \(I\subseteq\mathbb{R}\) is an interval, that associates a point \(\gamma\left(t\right)\in\mathbb{R}^{3}\) to each value of a parameter \(t\in I\).

As a first example, consider a meridian as a space curve. We'll use spherical polar coordinates with radius \(r\), longitude \(\theta\) and colatitude \(\varphi\). (Colatitude is latitude \(- \frac{\pi}{2}\): latitude measured from the North Pole.)

The equation of a meridian at longitude \(\theta_p\), as a function of \(\varphi\), is

\[m(\varphi) = (r\cos(\theta_p)\sin(\varphi),r\sin(\theta_p)\sin(\varphi),r\cos(\varphi))\]

The range of \(\varphi\) is \(]0,\pi[\).

Consider a loxodrome \(\ell_\alpha\) that intersects the meridians at angle \(\alpha\).

A fixed point \(P\) on \(\ell_\alpha\) has coordinates \((r, \theta_p, \varphi_p)\).

The fine article on atractor.pt starts with the case of \(\alpha = \frac{\pi}{2} + n+n\pi\), for some \(n\in\mathbb{Z}\). This example covers the loxodromes that coincide with parallels of latitude, and it's a fine warm-up, but not very revealing. Such loxodromes are most straightfordwardly thought of as being parameterized by longitude, \(\theta\).

The general loxodrome, with a spherical spiral form, corresponds to the case \(\alpha \neq \frac{\pi}{2} + n\pi, n\in\mathbb{Z}\).

In this case, the parameterisation of \(\ell_{\alpha}\) is given as a function of colatitude. Because of the nature of the spherical spiral, there is a just one point of the curve at each (co)latitude. Longitude would not work as a parameterisation for a spherical spiral, or at least longitude conventionally limited to the range \(-\pi\) to \(\pi\) would not.

We define a function

\[\begin{array}{ccll} \ell_{\alpha}: & ]0\,,\pi[ & \longrightarrow & \mathbb{S}^{2} \\\\ & \varphi & \mapsto & \left(r\cos\left(\theta_\alpha\left(\varphi\right)\right) \sin\varphi, r\sin\left(\theta_\alpha\left(\varphi\right)\right), r\cos\varphi\right),\end{array}\]

The next step is to find the formulas of the tangents to both the loxodrome \(\ell_\alpha\(\varphi)\) and the meridian \(m(\varphi)\). This is achieved by componentwise differentiation.

\[\begin{array}{rccl}\ell_{\alpha}^{\prime}(\varphi_{P}) & = & & r\,\theta'_\alpha\left(\varphi_{P}\right)\left(-\sin\left(\theta_{P}\right)\sin\left(\varphi_{P}\right)\,,\,\cos\left(\theta_{P}\right)\sin\left(\varphi_{P}\right),0\right)\\\\ & & + & r\left(\cos\left(\varphi_{P}\right)\cos\left(\theta_{P}\right)\,,\,\cos\left(\varphi_{P}\right)\,\sin\left(\theta_{P}\right)\,,\,-\sin\left(\varphi_{P}\right)\right)\end{array}\] and \[m'(\varphi_{P})=r\left(\cos\left(\varphi_{P}\right)\cos\left(\theta_{P}\right)\,,\,\cos\left(\varphi_{P}\right)\,\sin\left(\theta_{P}\right)\,,\,-\sin\left(\varphi_{P}\right)\right)\,.\]

These angle between these two tangents is \(\alpha\). Thus

\[\cos\alpha=\frac{\ell_{\alpha}^{\prime}\left(\varphi_{P}\right)\,|\,m'\left(\varphi_{P}\right)}{\Vert\ell_{\alpha}^{\prime}\left(\varphi_{P}\right)\Vert\times\Vert m'\left(\varphi_{P}\right)\Vert}\,.\]

After some calculating, we get

\[\cos\alpha=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+[\theta_{\alpha}^{\prime}(\varphi_{P})]^2sin^2(\varphi_{P})}}\]

Isolating \(\theta_{\alpha}^\prime(\varphi_{P})\), we have

\[\theta'_\alpha(\varphi_{P}) = \pm\frac{\tan\alpha}{\sin\left(\varphi_{P}\right)}\]

(This solution is only possible because \(\cos\alpha\) is not \(0\) and \(\varphi\in\ ]0, \pi[\).)

It is now possible to integrate this expression with respect to \(\varphi\) to get a formula for \(\theta_\alpha(\varphi)\): choosing to integrate \(-\frac{\tan\alpha}{\sin\left(\varphi_{P}\right)}\), the formula is \(\theta_\alpha(\varphi)=\tan\alpha\ln\left(\cot\frac{\varphi}{2}\right)+k\), for some constant \(k\in\mathbb{R}\). Since \(\theta_\alpha(\varphi_{P})=\theta_{P}\), we get \(k=\theta_{P}-\tan\alpha\ln\left(\cot\frac{\varphi_{P}}{2}\right)\).

Therefore, if \(\alpha\neq\frac{\pi}{2}+n\pi\), with \(n\in\mathbb{Z}\), then a parametrisation of \(\ell_{\alpha}\) is given by:

\[\begin{array}{ccll}\ell_{\alpha}: & ]0\,,\pi[ & \longrightarrow & \mathbb{S}^{2}\\\\ & \varphi & \mapsto & \left(r\cos\left(\theta_\alpha\left(\varphi\right)\right)\sin\varphi\,,\,r\sin\left(\theta_\alpha\left(\varphi\right)\right)\sin\varphi\,,\, r\cos\varphi\right)\end{array}\,,\] with \(\theta_\alpha(\varphi)=\theta_{P}+\tan\alpha\left[\ln\left(\cot\frac{\varphi}{2}\right)-\ln\left(\cot\frac{\varphi_{P}}{2}\right)\right]\).

This result is less advanced than the formula for the loxodrome that Wikipedia gives. The calculation is "elementary" in the sense that it avoids hyperbolic trig functions and the Gudermannian function (whatever that is). Elementary doesn't mean simple.

0 notes

Text

The Thames Estuary

I'm wary of the tendency for artists, architects and others to view the Thames Estuary as a kind of alternative day trip from London. A place which is often viewed with contempt, if it is considered at all, it is in danger of being understood only superficially. Creative people like to view such in-between places critically: as liminal environments, not just as a quiet interlude away from the city or a bit of welcome solitude. The relics of militarization leave the estuarine coast as a kind of prepared landscape. Like the strings of a prepared piano, the prepared landscape is dotted with mechanical artefacts, often tilting away from the vertical, of uncertain purpose and condition. The apparently haphazard siting of concrete pillboxes from 1940 suggests an aleatory organization, but of course every pillbox was part of a system of defenses which could be understood with the right map. In his book Bunker Archaelogy, Paul Virilio uses the word cryptic to refer to the architecture of the concrete bunkers of the atlantic wall. This establishes a response that's grounded in ignorance, in an inability to read the structures. Of course, they are missing important pieces. The roughness of the remaining concrete lacks the counterbalancing fineness of precise rangefinders and guns. An archaeological grasp of the bunkers necessarily involves an accounting of this missing equipment: the bolt holes and other tell-tale traces of its presence, the characteristic shapes of buildings constructed for particular purposes. Architecturally speaking, the absences result in a certain muteness. We're accustomed to a balance between polished hardware and raw structure. As Le Corbusier said

“I have decided to make beauty by contrast. I will find its complement and establish a play between crudity and finesse, between the dull and the intense, between precision and accident.”

Virilio's book contains a memorable section headed "Basculements". It consists of photographs of bunkers that have been undermined and are gradually tipping over. Their off-kilter attitudes seem to be evidence of demilitarization. Nature is once again taking its course. A soft, gradual process is occuring, rather than the sudden violent concussions the bunkers were built to withstand.

The peacefulness of the estuary, on a good day, gives the same impression of gradualness. A channel might be silting up, but slowly. Silt is the particulate analogue of a whisper – the grains are just larger than those of silent clay. It lacks both the plasticity of clay and the perceptible granularity of sand. So the silent estuary appears to be a place of repose, of gradual disintegration and engulfment. For Dickens, high tide corresponded to birth, and low tide to death. A primarily negative reading of the estuary (no crowds, no noise) situates it closer to death's end of the tidal range. To the visiting Londoners it appears to be a slack place, rather than a busy one; an unfixed, indeterminate location rather than an active and salient point of reference.

The militarization of the estuary has seen many unintentional explosions. As historical events, they inspired Brian Dillon's book The Great Explosion. He concentrates on a blast that took place in Faversham in 1916. It's clear that any explosion is almost the opposite of the experience of unthreatened respite that the estuary seems to offer its visitors. Yet there are threats even today. The wreck of the Liberty ship SS Richard Montgomery lies off Sheerness, with its cargo of 1,400 tonnes of explosives. Work is underway to remove it, but until that happens, it is a hazard clearly visible to the inhabitants of Sheerness. (One of those inhabitants was the East German writer Uwe Johnson, who wrote about the ship.

Climate change is another grave man-made threat. Every spring tide takes on an ominous quality in the light of sea level rise. The combination of a storm and a high tide could be a catastrophe. The greatest loss of life so far took place in 1953. The Dutch seem to be better at remembering this event than the English: a museum near Ouwekerk is housed in four concrete Phoenix caissons from WW2, resting among the dikes in an irregular formation not unlike the basculements of Virilio (himself a theorist of disasters).

The social life of the estuary is of relatively little interest to the Londoners who visit — perhaps even to those artists who make their homes in Ramsgate or Deal as a way of opting out of the London property market. These blow-ins mean well, but like WG Sebald, they have their own lives and concerns, and can't be expected to represent the place to the world. The German architect Timo Keller maintains a comprehensive website of material related to artistic production about the estuary: The Thames Estuary Library. Immaculately designed, it asserts a kind of superiority of the architect's eye for drabness. A modernist insistence on construction rather than ornament is supported by the prepared landscape, in which every strange interruption once served a purpose. The "brownfields" site of the estuary must seem expansive when compared with the restrictions of urban life and urban practices, architecture among them. One wonders whether an affinity for the estuary is accompanied by strains of misanthropy or agoraphobia.

0 notes

Text

Rationalism

The windows on the stairway of Millbank House are described in the listing as "rational":

An eclectic yet sophisticated Free Style northern Renaissance design including Renaissance Plateresque motifs, only slightly asymmetrical and with "rational" expression of staircase fenestration, five and six storeys plus two tiers of dormered attics.

You might expect a rational approach to result in a rectilinear grid. This arrangement of windows follows the slope of the staircase, serving the interior space rather than any compositional ordering of the façade, so it's arguably rational in a truer sense than an arbitrary rationalism.

Emil Kaufmann, a significant theorist of rationalism in architecture, described the approach as entailing "the division of the composition into independent units". The holistic, hierarchical and centralised architecture of the Baroque was superseded by an architecture of discrete geometrical parts, an architecture of components

Writing in 1952, in his book Three Revolutionary Architects: Boullée, Ledoux and Lequeu, Kaufmann outlined this development.

The forms which promised best to serve the double end of expressiveness and individualism were those of elementary geometry. Self-contained, these forms allowed the parts to be independent from each other. Moreover, they allowed the architect to give "character" to a building by differentiating the constituents in size, or by contrasting them in shape. The revolutionary architects also passed from the traditional to the geometrical forms because their attitude toward the material had undergone a profound change. The sensuous Baroque features with their flexibility expressed the Baroque trend toward animism (All-Beseelung). This trend accounts for the preference that was given to "living" forms, e.g., supports in the shapes of Caryatides and Atlantes, or furniture legs ending in claws, etc. The revolutionary architects began to pay more attention to the inherent properties of the materials and liked to present them without any disguise. Although some of their experiments were expressive of the excitement of the period, their goal was no longer outward show, it was restraint.

Rationalism was natural, but natural in terms of construction, not in terms of organic growth.

Obviously, the "natural" plan had nothing to do with a model taken from nature; it was the logical, or the practical, as opposed to the organic and ornamental plan of the Baroque.

So, for Kaufmann, rationalism was an individualistic freeing-up of the arrangement of the architecture, through the dismissal of absolutist Baroque ideas about composition and representation. He was interested in precedents for modern architecture, and it shows.

0 notes

Text

The Afterlife of the Social Condenser

In the late 1920s, for a brief period, Soviet architects discussed a concept they referred to as a social condenser: a kind of architectural device which was intended to engender communist life. Recent scholarship has sought to recover this notion from its capitalist appropriation by Rem Koolhaas, and revitalise and repurpose the metaphor for 21st century struggles – well, not so much the metaphor, but the expression. The term "social condenser" has always been an almost pure example of rhetoric, containing barely enough substance to serve as an architectural formula. The words have a certain fascination due to the fact that they contain the verb "to condense" – "condenser" is an agent noun.

One of the most prolific scholars to have published on the topic is the London-based anthropologist Michał Murawski, sometimes writing in collaboration with Jane Rendell. The adequacy of their understanding of the sociopolitical context is not in question, but the interpretation they give to the metaphor or the social condenser is doubtful.

Did the Soviet architects who coined the term have steam condensers or electrical condensers in mind? Nobody knows for sure. Perhaps they never decided on a canonical interpretation, using the word just because they liked the ring of it. The metaphor's active life was very short.

Murawski, along with a bandwagon of retrospective interpreters, favours an electrical interpretation. I don't take his reading as definitive, not because he is not a Man of Science, but because he hasn't taken seriously the metaphor's grounding in the (electrical) condenser as an actual device. If he had consulted an electrical engineer, he would have learned that the condenser is a rudimentary thing. Its characteristics are easily grasped. The highly technological nature of "scientific socialism" makes this kind of technical inquiry even more appropriate than it would be in a typical anthropological or historical research project. Instead, he chose to bluff his way through.

Here he is on video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-X_GEJ3SGlw&t=128s. As a Youtube commenter remarked:

(I believe this commenter is not just a random Internet wise guy but the same Igor Demchenko who is based in the architecture department at TU Darmstadt.)

And here is Murawski writing about the metaphor, conflating condensers with transformers:

The term ‘condenser’ itself derives from the word for an electrical transformer – a device used to re-deploy and intensify electric currents. In line with the futurist electricity-fetishism typical of early 20th century radical movements – best expressed, as Russian literature scholar Katerina Clark has observed, in the Soviet context by Lenin’s famous proclamation, ‘communism equals Soviet power plus the electrification of the entire country’ – the idea of the Social Condenser is suffused with vivid connotations pertaining to electricity, radiation, and magnetism. For the Constructivists, social condensation was about filling architecture with a sort of revolutionary political electricity. As theorized, designed, and built, the Social Condenser was to be an architectural device for electrocuting people into a communist way of life (byt). Strelka Magazine, 2017 (archive link)

and in another article:

The social condenser is a theoretical concept developed by radical Soviet Constructivist architects in the 1920s. It is devoted to conceiving how architecture, the city and public space can coalesce into an integrated machine for bringing people into close proximity with each other, and – like a condenser or transformer in an electrical circuit – increasing the “voltage” or intensity of their interactions. The effect of this act of social condensation, for lead proponents Moisei Ginzburg and others, would be to transform people from alienated, isolated bourgeois subjects to self- and mutually fulfilled members of a collectively oriented, radical new society. Tank Magazine, Autumn/Winter 2020

It seems wrong to me that Murawski considers the programme of rural electrification to be evidence of fetishization of electricity itself, rather than a highly socially relevant and progressive public works project. In addition, there's the problem that electrocution technically refers to execution by electric shock.

It is worth noting that the paragraph Murawski references in Clark is directly after an inaccurate citation in her book: Katerina Clark quotes Catherine Cooke's words but attributes them to Moisei Ginzburg. Thus Cooke's (electrical) interpretation gains momentum in the literature and risks becoming canonical.

By 1995 Cooke herself had apparently pulled back from this definitively electrical framing of the metaphor, and wrote that the social condenser was "a chemical or electrical analogy (it is not clear which)".

Here is what Katerina Clark wrote, also in 1995:

Ginzburg is using "condenser," a term that denotes the apparatus where change occurs in a variety of physical processes, such as condensation of steam, in the specific context of electricity (where it means an apparatus for accumulating or increasing the intensity of an electrical charge). Thus he is implicitly identifying his theory with Lenin's famous maxim of 1920: "Communism equals socialism plus the electrification of the entire country. But the particular electrical apparatus Ginzburg chose as his central trope, the condenser, provides the added implication that the effect of the social condenser will be not merely to convey "electricity" but to intensify it, thus the end sought was not merely a more proletarian society, but also a society that had stepped up to a higher intensity of living.

Now, the first sentence of this quote is inaccurate: the term condenser is not a generic technical term that's used in a variety of ways: it's a term with two meanings that are scientifically unrelated: the electrical one, due to Alessandro Volta, and the slightly later steam-related one, related to the functioning of turbines and steam engines. The fact that the meanings are unrelated and cause confusion was the motivation for adopting the new name "capacitor" for the electrical condenser, a change which started in the 1920s. It is not clear whether Clark was aware of the ambiguity acknowledged by Cooke. We can't know whether Ginzburg was alluding to Lenin's ideas, let alone identifying the two programmes.

Murawski misinterprets Katerina Clark's first sentence in his own way, saying

Cultural historian Katerina Clark draws attention to the fact that Ginzburg makes use of the term ‘condenser’, referring to an apparatus which brings about changes in physical processes through electricity.

His rephrasing implies that the condenser causes physical changes through electricity, while Clark is making the more accurate (but still problematic) claim that condensers (in general) are the site of changes in physical processes.

The latter part of Clark's paragraph follows Catherine Cooke's electrical reading of the metaphor very closely. Cooke had written:

Low-voltage activity and a weak consciousness would be focused through the circuits of these “social condensers” into high-voltage catalysts of change, in the habits and attitudes of the mass population.

Note that this claim itself is flawed, as an electrical condenser (capacitor) cannot increase the voltage of electricity. It can only store charge. Nor does a condenser contain circuits – it's much simpler than that.

Clark mentions another metaphor, that of the cell:

The communal house was to be a "cell" of a future utopia. (Clark, 1995)

This statement is somewhat perplexing, in the light of N.A. Miliutin's discussion of planning for the provision of an "individual residential cell (that is, for each person)". However unpalatable it may be to us now, the vision was of a large communal house consisting of cells, rather than constituting a cell. It was Miliutin who commissioned the Narkomfin building. Were large public buildings, such as clubs to be considered as cells as well? Their role as collective, rather than individual, accommodation would seem to complicate this description.

The Narkomfin building contained both individual living spaces (cells) and shared spaces such as dining rooms. Such a programme owes a great deal to the well-established typology of the military barracks. The social condenser's project of encouraging citizens to adopt a collective lifestyle seems to have a sociological flavour of regimented structural functionalism with a theoretical core of methodological individualism. This is what architectural determinism looks like: a place for everything, for the cultivation of every kind of approved behaviour, and for none of the deprecated behaviours.

The architectural historian Tijana Vujosevic has drawn attention to the Soviet programme's attention to the individual, rather than only the abstract collective. One Soviet building type she has investigated is the bath house, a place where personal hygiene and collective hygiene intersect, and equally a (warm, humid) social condenser where people who might not otherwise even come into contact with each other had the opportunity to interact informally.

There were two poles to these Soviet architectures: the individual cell inhabited by a single adult, and a variety of communal spaces that were used collectively.

The architect Rem Koolhaas was inspired in the late 70s by the architect Leonidov's writings and unbuilt projects, which included interpretations of the social condenser idea. For Koolhaas, it was the programmatic complexity and intensity of the buildings created by the idea which was attractive. Murawski, the cool kid, writing 40 years later, disparages the words of the no-longer-hip Koolhaas, describing them as "ungainly". Yet Koolhaas is no dummy, and his gloss of the condenser metaphor is pithy:

Programmatic layering upon vacant terrain to encourage dynamic coexistence of activities and to generate through their interference, unprecedented events.

There seems to be a close connection with the electrical metaphor, here, in the sense that the "vacant terrain" is the dielectric, and the layering of programmes corresponds to the plates of the condenser. It seems likely that Koolhaas investigated and/or intuited the metaphor's mechanics at least as deeply as Murawski and Rendell. At the same time, his 1979 paper The Future's Past doesn't even mention the term, while deploying the concept. My impression is that this was a shrewd decision. Koolhaas wanted to create a prescription for future architecture, not a divagation on quaint revolutionary propaganda.

As a metaphorical vehicle, the electrical condenser is itself ungainly, having multiple parts with no clear analogue in social interactions. The steam condenser has the advantage of being very simple in its structure: it is literally an empty, cooled vessel, a volume into which steam flows and out of which water can be drained.

I want to discuss the social condenser as if the workings of the metaphor mattered. There is the known revolutionary context, on the subject of which the historians and anthropologists are experts, and whatever interpretation we select must comport with the context.

As Murawski and Rendell write (in formalistic terms) the true intention of Ginzburg et al cannot be recovered:

Since, in any case, it is impossible to get into the heads of the Soviet Constructivists, to discover beyond any doubt what they ‘really meant’, we work towards formulating a redefinition of the ‘social condenser’, deployable in the twenty-first century—not only on historical and theoretical grounds, but also on the contested terrain of practice—to the design and use of the built environment itself.

To keep the metaphor "alive", it must have the flexibility to respond to and reflect its sociopolitical context. Yet a metaphor that is not understood at all as an image (by anyone) is rightly called dead.

First of all, though, I must acknowledge the countervailing desire to see the term remain an open signifier, freely applicable to such architectural entities as housing estates and pubs. Murawski and Rendell write that "the precise significance of the social condenser is difficult to pin down." Such a floating signifier can serve to represent a lack: nostalgia for the social condenser arises from melancholic feelings of attenuation and atomization of the social fabric. Victor Buchli, in an article about social condensers, quotes from Eng and Kazanjian's 2003 book Loss: The Politics of Mourning:

The ability of the melancholic object to express multiple losses at once speaks to its flexibility as a signifier.

I'm not sure the social condenser, as a concept or even just as a term, has the flexibility to cope with the demands that are placed on it, these days. Michał Murawski's 2017 piece for the Architectural Review's Outrage feature refers vaguely to the ongoing loss of "sites of social condensation". What exactly does this verbing of the metaphor evoke, that couldn't be communicated more specifically? At times it feels that this terminology has little going for it other than its nebulous nature, its appeal to those who have a taste for obfuscation.

The psychoanalytic milieu is full of abstract concepts which cannot be visualized. The ability to operate at this schematic, imaginary level is central to psychoanalytic thinking. Thus, the nebulous character of the notion of a social condenser is entirely unproblematic to the psychoanalytic mind: it's just as (un)manipulable and (un)graspable as any other term of art in that field. Jane Rendell's writing seems to exist happily in that milieu. After all, condensation is also a psychoanalytic concept.

Yet from the first moment I heard the term, decades ago, I have been an enthusiastic believer in its power to evoke the forms of collectivistic architecture. I find the image of gas particles (molecules of water, in the case of steam) bouncing around in a container and coalescing into a liquid vivid and memorable.

The idea of using a scientific or technological metaphor to describe a place where people are brought together by architecture is not a complicated one. Here is an exemplary modern "living" metaphor of social interaction in architecture, based on the notion of collisions between individuals, seen as particles. (The building under discussion was by Steven Holl Architects.)

Instead of precisely defining the activities inside it, the Rubenstein Commons creates a space between — not just between walls, but between life and architecture. Like a hadron collider, the building smashes atoms (or, to paraphrase David Rubenstein, collides great brains together), in order to expand the horizon of our knowledge and collective human consciousness. (Anna Bokov, 2021)

This metaphor is so clear as to be almost trivial. What is it about the metaphor of the social condenser that makes it so fascinatingly elusive? I believe it's simply that it has not been understood.

Writing in the 70s, Anatole Kopp, while subscribing to the electrical interpretation of the social condenser, also presented a clear evocative image of proximity and coalescence:

Like electrical condensers that transform the nature of current, the architects' proposed "social condensers" were to turn the self-centered individual of capitalist society into a whole man, the informed militant of socialist society in which the interests of each merged with the interests of all.

Here Kopp asserts that electrical condensers "transform the nature of current", a grand claim that no electrical engineer would agree with. The next thing he says – about the merging of interests – would, in contrast, be a good fit for a steam condenser metaphor, as molecular water vapour ("the interests of each") becomes bulk liquid ("the interests of all"). This phase transition is a bona fide transformation – whereas the operation of an electrical condenser is a way of storing energy. The condenser is a device which transforms fine steam into coarse water.

Nevertheless, it is the electrical interpretation of the concept of a social condenser that has gained most support in the literature. So what is to be said about it, as a metaphor?

The most typical first encounter a student has with a electrical condenser (capacitor) in an educational context is as a device which can be charged up by applying a voltage. Having been changed, it can then release a jolt of current, usually brief and much more intense than the current which flowed when it was changing up.

In a more advanced sense, the capacitor can be understood as a circuit element that allows a current to flow which is proportional to the rate of change of voltage (whether increasing or decreasing). This means that alternating current can often flow through capacitors, while direct current quickly stops flowing.

The capacitor is one of four ideal electrical components, along with the inductor, the resistor and the memristor. Whether the other components can serve as sociopolitical metaphors is an open question. I'm pretty sure it's possible to understand the capacitor without understanding the other components.

Buchli's article on the topic insists on keeping the term in scare quotes throughout ("social condenser"), as if it is a delicate and potentially dangerous object to be analysed at arm's length, perhaps in a glovebox or with a remote manipulator. The distant, quasi-technical aura of the concept extends to its characteristics as an idea. As Tijana Vujosevic puts it, "utopia is traditionally discussed in terms of the abstract diagram".

In Kopp's book, the following propagandistic passage is quoted:

Under communism people receive a many-sided culture, and find themselves at home in various branches of production: to-day I work in an administrative capacity, I reckon up how many felt boots or how many French rolls must be produced during the following month; to-morrow I shall be working in a soap factory, next month perhaps in a steam laundry, and the month after that in an electric power station. This will be possible when all the members of society have been suitably educated.

This is the spirit of scientific Socialism – the spirit of diverse industrial experience, and at least a smattering of technical knowledge, for every member of the population. Much as the social condenser brought diverse individuals together in the same place, diverse experiences would accrue to each individual.

The writer Andrei Platonov, for example, who came of age at the time of the revolution, studied electrical engineering and worked in the field until 1927. There is no doubt that he knew what an electrical condenser was and how it worked.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn studied mathematics and physics; Yevgeny Zamyatin trained as an engineer. These men would have interrogated the metaphor of the social condenser from the perspective of technical knowledge rather than revolutionary zeal. It's not an unrealistic standard to try to live up to.

As part of their research project on the topic, Murawski and Rendell had Moisei Ginzburg's original articles on the social condenser translated into English. These texts contain clues about the architect's own conception of the metaphor.

Ginzburg admiringly describes the equipment of the chemical (not electrical) industries including "[T]he complex process of a plant for the production of sulphuric-acid, with multiple, coordinated diagrams of circulation and schemes of specialised equipment."

He goes on to itemize the equipment: ""Illustrations 7, 8 and 9, (architect E. I. Norvert) offer a new and striking solution for a thermoelectric plant (with boilers), which functions by means of the subdivision of complex production processes into architectural sections, achieved, on the one hand, thanks to hoppers arranged on a flat plane, and, on the other, to cauldrons placed next to furnaces fed by workers."

It is striking that Ginzburg mentions the imposing forms and architectural disposition of the apparatus: boilers, hoppers, cauldrons, furnaces. The vision of a constructivist architect interprets these imposing objects, their orderly spatial adjacencies and relationships to a "flat plane", as geometric primitives, rather than understanding them as technical contrivances.

It is noteworthy that all thermoelectric plants in the 1920s had (steam) boilers, yet Ginzburg enthusiastically mentions their presence. A thermoelectric plant would have included, along with the boilers, one or more generator sets, each comprising steam turbines, their condensers, and an electrical generator or dynamo. The word dynamo (Динамо) was, of course, adopted as the name of the Soviet sports association founded in 1923. While the steam condenser may appear to be a comparatively static, ancillary element in the generator set, it would have been on the same scale as the other industrial elements that so impressed Ginzburg. I consider it very likely that he had these steam condensers in mind when he formulated his the concept of the social condenser. Electrical condensers did not exist on the same scale; they did not manifest as impressive elements of an industrial ensemble.

That Ginzburg was inspired by the dynamism of factories is obvious from his 1924 book Style and Epoch. He writes

[I]f one were to think about what actually gives this image its vividness and tension, one would easily realize, of course, that it is first and foremost the machine. Take the machine away from the modern factory and you will immediately see the loss of that rhythm, that organization, and all that pathos of labor. It is precisely the machine, the main occupant and the master of the modern factory, which, having already exceeded its bounds and gradually filling all the corners of our way of life and transforming our psyche and our aesthetic, constitutes the most important factor influencing our conception of form.

The social condenser was to be a kinetic, operative piece of machinery, not a dead quotation of industrial forms.

Ginzburg, was, however, an architect, compelled to abstract the dynamism of machinery into purer, clearer forms. The design of a locomotive was explained (in Style and Epoch) as resulting from movement in a particular direction; every other aspect of its design, all of the intricacies, were abstracted away. Analogously, the volumetric form of a condenser could become, in the hands the constructivists, a glass drum. As such, it became something primarily formal, rather than a socially or technically motivated space. There is no better example of this than Ilya Gosolov's Zuev Club of 1926, with its huge cylindrical room lifted above the street corner.

0 notes

Text

Boredom and Terror

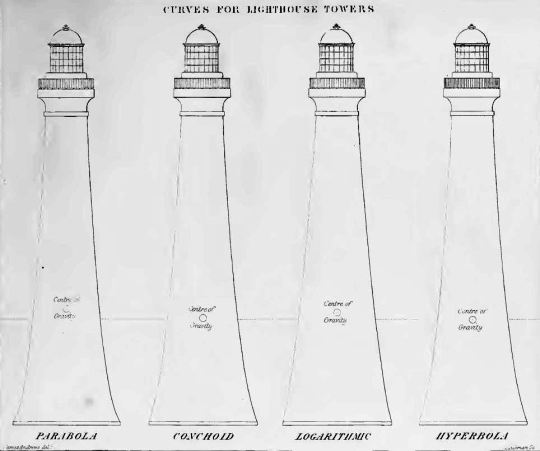

In his account of the construction of the Skerryvore lighthouse, Alan Stevenson includes a diagram comparing four options for the curve of the tower. Like most lighthouses, the tower was to be a solid of revolution, narrower at the top than at the bottom (a "conical frustum"). The possibility of the tower being knocked over, or, in the language of the time, overset, by the waves was a central concern. The four parametric curves investigated by Stevenson were the the parabola, the conchoid, the logarithmic and the hyperbola. In the diagram, the four curves are barely distinguishable. In an accompanying table Stevenson recorded the height, G, of the centre of gravity of each of the four towers and the volume, M, of stone required to build a solid tower of that shape. He wrote that he considered the "economic advantage" of each tower to be inversely proportional to the product of G and M. Based on the result of this calculation, he chose a hyperbolic profile for Skerryvore.

In Stevenson's day, civil engineering was a matter of tacit knowledge as much as rigorous theory. His use of mathematics wasn't empirical, and could be described as aspirational: a mathematically perfect construction would be perpetually sound. His father, Robert Stevenson, had deployed a cycloidal curve in sea walls and in the base of the Bell Rock lighthouse. The rationale there was that the cycloid is the brachistochrone – the curve down which an object will slide or roll most quickly. Thus, according to Robert Stevenson's argument, waves washing against a cycloid would subside as quickly as possible.

Some later wave-washed lighthouses used curves that had not been considered by the Stevensons. Wolf Rock (1869), the fourth Eddystone lighthouse (1881) and the Fastnet lighthouse (1904) all have an elliptical profile, while a few other towers have straight conical sides.

Curves are tangible things. An more abstract argument was presented by John Smeaton for the soundness of his third Eddystone lighthouse (the third). He deployed mathematical induction to claim that a stone tower could not be overset by the sea:

WHILE I am upon this part of my subject, I will take an opportunity of observing that it was a part of my problem, which I will not take upon me to say that I have accurately solved; but I have endeavoured to do it, so far as my feelings, rather than calculations, would bear me out: That the building should be a column of equal strength, proportionate in every part to the stress it was likely to bear (regard being also had to its use,) was a view of the subject I was naturally and forcibly led to, as I found it eternally rung in my ears from all quarters, that a Building of Stone upon the Edystone would certainly be overset. I therefore endeavoured to form it, and put it together so, that while a similarity of use permitted a similar construction, no man should be able to tell me at what joint it would overset; for, if at any given height the uppermost course was, when completed, safe, it became more safe by another course being laid upon it; and that upper course, though somewhat less in weight, and in the total cohesion of its parts, than the former; yet every course, from the first foundation, was less and less subject to the heavy stroke of the sea. (A narrative of the building and a description of the construction of the Edystone Lighthouse with stone, 1791)

Like Robert Stevenson, Smeaton did not name the mathematical principle to which he was appealing. His argument is based on discrete logic, and appears to neglect the fact that waves striking the tower higher up have a larger lever arm with respect to the base. As the height and leverage increases, the "stroke of the sea" would diminish, but at what rate? Smeaton's claim is framed as a indisputable inductive proof ("no man should be able to tell me at what joint it would overset"). It is dry and appeals to the tedious reliability of mathematical reasoning.

Such a proof would presumably have been reassuring, even if it was flawed. The occupants of a wave-washed lighthouse had no choice but to put their faith in the engineering and construction of the tower, in its sheer unyielding truth. In a storm, no action on their part, however vigorous, could help them. It must have been an experience of impotence and confinement, terrifying, but eventually boring as well.

0 notes

Text

This post is the media theory idea of "modularity", which applies to digital representations, among other things.

A computer "word" consisting of 32 bits can be seen as a modular object, which is built from 32 identical units. In design, the notion of a bit occurs whenever an object or device has two alternative states.

London's South Bank Centre commissioned an interactive installation to promote participation in the arts. PLAY.orchestra recreated an empty orchestra pit of 60 seats, where commuters or other passers-by, including disabled persons, could take the stage and together experience a musical piece from the player's perspective. By taking a seat or entering floor hot spots, a recording of the correspondent musical instrument was triggered. As more people sat down, the composition progressively revealed its whole. https://theindexproject.org/post/playorchestra (2006)

There's a digital interpretation of this (2⁶⁰ possible states) but the media theory reading just sees 60 separately recorded parts and some current subset that happen to be audible.

Lev Manovich, one of the major theorists of modularity, appears not to be interested in the technical aspects of digital encoding

It is interesting to imagine a cultural ecology where all kinds of cultural objects regardless of the medium or material are made from Lego-like building blocks. The blocks come with complete information necessary to easily copy and paste them in a new object – either by a human or machine. A block knows how to couple with other blocks – and it even can modify itself to enable such coupling. The block can also tell the designer and the user about its cultural history – the sequence of historical borrowings which led to the present form. And if original Lego (or a typical twentieth century housing project) contains only a few kinds of blocks that make all objects one can design with Lego rather similar in appearance, computers can keep track of unlimited number of different blocks. At least, they can already keep track of all the possible samples we can pick from all cultural objects available today. https://manovich.net/content/04-projects/046-remixability-and-modularity/43_article_2005.pdf

It's worth reflecting on this focus on the morphology of a modular system and the total neglect of its semantics. Linguistics provides a familiar example of a system in which the modular units (words or letters) are articulated in complex ways. The simplest example is the idea of a modifier: one word changes the meaning of a second, and what remains is a single semantic unit. Other examples of complexity in modularity are to be found in video games, especially puzzle games (where multiple mechanics are combined) and deck-building games in which some cards intensify the qualities of others. The routine forms that modular systems take are much subtler than the Lego block metaphor conveys.

(These examples are from twenty years ago, but Manovich hasn't really moved on, as far as I can tell.)

0 notes

Text

for a linear increase there is an exponential reduction

"Claude Shannon wrote the best master's thesis ever when he was at MIT, inventing digital. He went on to Bell Labs and did two core things. The one that's most interesting for me is he proved the first threshold theorem. What that means is I could send my voice to you today as a wave, or I could send it to you as a symbol. What he showed is if I send it to you as a symbol, for a linear increase in the resource used to represent the symbol, there is an exponential reduction in the error of you getting the symbol correctly as long as the noise is below a threshold. If the noise is above the threshold, you're doomed. If it's below a threshold, a linear increase in the symbol gives you an exponential reduction in error. There are very few exponentials in engineering. That's the big one." (Neal Gershenfeld)

0 notes

Text

"Technological change is not additive; it is ecological. I can explain this best by an analogy. What happens if we place a drop of red dye into a beaker of clear water? Do we have clear water plus a spot of red dye? Obviously not. We have a new coloration to every molecule of water. That is what I mean by ecological change. A new medium does not add something; it changes everything. In the year 1500, after the printing press was invented, you did not have old Europe plus the printing press. You had a different Europe. After television, America was not America plus television. Television gave a new coloration to every political campaign, to every home, to every school, to every church, to every industry, and so on." (Neil Postman)

0 notes

Text

Adjunctions and accommodations

There's a distinction made in psychology between assimilation and accommodation. The first term describes what happens when a new piece of information is compatible with existing mental schemas, and can be just slotted into place, as it were. The second term describes the process of adjusting mental schemas in order to make sense of new and incompatible piece of information.

Now, more broadly, assimilation can refer to cultural assimilation, which is a way of becoming a participant in a pre-existing culture, without that culture changing in any way. To assimilate is to adapt to the culture and behave like any other member of it. Assimilation can lead to unjust outcomes, whether due to a loss of minority cultures or discrimination within the assimilating culture.

Accommodation, too, can have a cultural meaning. It implies that the accommodating culture acknowledges and integrates new members. They aren't forced to leave their original culture behind, nor are they required to conform to a preexisting template. The cultural schema changes to recognize the particularities of the cultures that new members bring with them.

I think it's helpful to think of this in terms of abstraction. In the case of assimilation, all participants share the same abstract properties, and nothing changes when someone with a new background assimilates. The row in the database that represents them is the same as any other. In the case of accommodation, when someone new arrives, the schema of the database may be renegotiated in order to register the ways in which they differ from the previously accepted "standard citizen". In this way, each member of the culture conceptually plays a constitutive role in the abstract schema that holds it together; the particular cultural background of each member is catered for and acknowledged. In a system where accommodation takes place, the schema is expected to evolve over time because of the arrival of new members.

I'm writing this in response to Tara McPherson's complaint that computer systems (which exhibit what media theorists call modularity) tend to promote merely additive acceptance of new cultural groups. I think her use of the word additive is problematic, as it casts digital technology as something involving concatenation – something that has a very simple morphology of bits or chunks tacked together – rather than something that, like language, participates in a kind of digital infinity of emergent possibilities. It's better to thing of digital components as potentially modifying each other's functions (like linguistic modifiers) that to reduce them to inert Lego-like blocks. Let's say, though, for the sake of argument, that the concept of treating new arrivals as merely "additional" instances of a preexisting pattern is a convenient one for computer systems.

This pattern of thinking supports the logic of founding a separate institution for an ethnic minority group, rather than integrating them into an existing institution. The problem here is that abstract equality between the two groups (the established ingroup, and the minority) has nothing to say about adequate and just standards of treatment. Indeed, from the abstract and schematic point of view, there is nothing wrong with segregation. It isn't visible in the data.

Even an extensible system has rules; adjustments within the rules are assimilations, whereas adjustments that required a rewrite of the system (say, of the database schema) are accommodations. Certainly, computer scientists like to manage with only "assimilation". It's much less work. But a conscientious computer scientist will know when it's time to redraft the database schema to create visibility into cultural particularities that have emerged since the previous iteration of the design process.

0 notes

Text

“It is imperative to remain less interested in who or what we imagine ourselves to be than in what we can do for one another, both in today’s emergency conditions and in the grimmer circumstances that surely await us.”

— Paul Gilroy

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Escaping from modularity

This post is loosely related to the book Nonsuch: Tudor Palace – Social Condenser, produced by Unit 14, London Met School of Architecture, 2015-16 (published 2024).

Georg Gerster, Longleat House, 1977

Georg Gerster's aerial photo of Longleat House contains both a foreshortened view of the building, which, thanks to the camera angle, looks like a 90-degree axonometric, and a prospect of rows of caravans across the water from the house. As the first stately home in Britain to have been opened to the public on a commercial basis (in 1949), Longleat exemplifies the transformation of large country houses from the private property of the aristocracy to some kind of collective heritage. This theme – the Tudor house as a public resource – is close to the theme of the Unit 14 project "Nonsuch", which inspired this blog post. The idea behind the project is that the architecture of such houses can inform the planning of new multi-purpose social centres; the so-called prodigy house offers a model of the people's palace. At the other extreme from the private wealth represented by the prodigy house is the communist concept of the social condenser, which forms the second part of the Unit project's title.

While prodigy houses often had a symmetrical exterior, their interior planning was notably asymmetric and provided diverse accommodation, not only for the owner, but for a visiting monarch. As emblematic buildings, they were intended to impress with their splendour, both in scale and richness of ornamentation, but it is perhaps their spatial generosity and large areas of glazing that are most relevant to architecture in the 21st Century. The key element of the Nonsuch project was the construction of large models of the grand spaces within a number of prodigy houses. These models omitted the structure and facade of the houses, showing only the dramatic volumes of the larger rooms and their spatial articulation. Although there is a sense of a promenade architecturale in these buildings, the path through the rooms has qualities of both the practical business of wayfinding and the ritual sense of an almost sacred route. Although the models contain little decoration, their bold cantilevers and jutting cubic forms are highly expressive. It's easy to relate them to the work of, for example, Rem Koolhaas, perhaps the most significant recent promoter of the concept of the social condenser.

That concept – the social condenser – seems to be understood these days as a kind of floating signifier. It certainly doesn't have a clear metaphorical interpretation, which I find a little frustrating. I'm not going to repeat any of the usual glosses of the term, which, in the hands of scholars, tend to slip from being correctly attributed to their true authors to being erroneously attributed to the Soviet originators of the idea; the words of later interpreters are attributed to the Soviet architect Moisei Ginzburg, who wrote the most prominent text on the social condenser in the late 20s. In 1995, Catherine Cooke described the concept as a "chemical or electrical analogy (it is not clear which)". I think it is valuable to maintain this ambiguity, given that no document has survived which would clarify the precise ideas of the inventors of the concept. The chemical analogy is with the steam condenser, as used to recover water in steam power plants. The electrical analogy is the capacitor, known from the time of Alessandro Volta as the "condenser" but renamed in the 20th Century to avoid confusion with the steam device. The extremely brief period in the late 1920s during which the concept of the social condenser was discussed in the Soviet Union was on the cusp between steam power and electrical power. The intention is clear enough, at an abstract level: the social condenser is a place where people get together, where metaphorical dots are joined and collectives form. In the fluidic version of the analogy, a gaseous, atomized populace coalesces into liquid, the fine and abstract becomes something coarser and more substantial. The electrical version of the analogy I find more troublesome, and I can't really come up with an interpretation of it beyond the idea of a place that engenders intensified relationships through proximity.

One imagines the social condenser as a place to go on a cold, wet day (precisely the conditions that lead to condensation). It's a place to socialise, in the broadest possible sense of the word, and as such is markedly different from housing. Housing in the communist sense might be quite uninspiring – cellular, repetitive – while the social condenser / social centre can only be imagined as having some kind of uniqueness and allure, if only by being the only building of its type in the vicinity. Gerster's photo can be seen as contrasting these two modalities of building. One the one hand, the caravans represent frugal dwellings, all more-or-less boring, typical and of a uniform size, while, on the other, the prodigy house is sumptuous, exceptional, full of wonders. Under communism, the only acceptable treasury is a common treasury.

Of the extant Soviet buildings to which the term might be applied, the Narkomfin building is the most prominent, but I find it hard to imagine it as a true, actually-existing example of a social condenser. A library and gymnasium were provided, which I suppose offered the possibility of collective self-improvement, but at a low level of intensity. This relatively dour, low-key realisation of the concept seems to fall short of the revolutionary call to realise human potential, artistic and intellectual as well as gymnastic. Is excellence part of the brief for a social condenser, or might it just be something as unassuming as a well-designed bus station? It seems to me that a bourgeois institution like the Opera Garnier in Paris (and its Beaux Arts building) functioned and functions culturally and socially in a mode to which the Soviet state ultimately aspired.

A practice space (architecturally atypical, functionally specialized) high in the roof of the Palais Garnier.

Citizens, cooped up in Existenzminimum apartments or, now, listlessly inhabiting suburban cul-de-sacs, were to be pulled out of their isolated lives by the social condenser in the same way that a steam condenser adds to the power of a steam turbine by creating a vacuum. Sure, a library has some of the necessary characteristics, or a building like Grafton Architects' Town House, with its dance studios. To my mind, though, a university building cannot be a true social condenser, because it's not truly public. Even a public meeting place only becomes a social condenser to the extent that it supports activities that do the work of "condensation". It must support the individuality of citizens in a social context, by which I mean that the activities must be not only universally accessible, but differentiated rather than homogenous, one-size-fits-all.

If weekdays involve individual specialization at work, and Sundays involve collective generality, the social condenser serves the needs of the Saturday of life: a chance to engage in collective specialization. In the most trivial sense, to join a class in something in particular, or to see a performance, or to practice a hobby as part of a group. For the Soviet architect Leonidov, the social condenser would support previously unheard-of forms of collective relation, presumably not just recreational activities but revolutionary ones. The secular gathering supported by a social condenser would be enjoyable but crucial to the forging of the communist society.

From an architectural point of view, rather than the collective aspect or the revolutionary one, it is the dimension of the differentiation of the activities, and the resulting need for a diverse set of spaces with particular distinct qualities, that is engaging. It is this that motivates the Tudor Palace – Social Condenser simile: a big social centre is a very interesting brief because of its potential spatial complexity and variability in use. The building is a container for a range of spatialities, all of which are out of the ordinary.

Taking the opposition between housing and the social condenser more abstractly, a contrast emerges between the modular and the integral. I imagine socialist housing as conforming to a modular scheme. In terms of caravans, it might be a fleet of Airstreams – vehicles designed without attention to site or aspect. The social condenser, on the other hand, integrates functions into a building with a definite site and orientation. Where housing is cellular and additive, the social centre is spacious and has a multiplicative quality. One more house or one more caravan is just another unit on the lot, but the n+1th person who uses the social condenser can make n new social contacts .

As Dean Hawkes writes in a paper reproduced in the Nonsuch book, a complex interior arrangement within a symmetrical envelope, as at Hardwick Hall, may have developed from an analysis of the path of the Sun through the seasons. In contrast to the design of movable pods or vehicles (think High-Tech, or Metabolism – for example the Nakagin capsule tower, or of mass-produced cars and caravans) the design of a (genuinely architectural!) building can take advantage of such specificities. A new building type drawing on the spirit of both Tudor palaces and social condensers has the potential to carry the practice architecture forward, both in creative terms and in terms of the discipline's social responsibility and potential.

0 notes

Text

Finding sculpture

Years ago I read a web page written by the curator Ine Gevers that drew a distinction between the "supraindividual/evolutionary" and the "individual/aesthetic". The page is gone from the internet and I have only my fragmentary notes to go on.

I think it's a useful distinction, although, like all distinctions in art history, it's a bit tendentious. Supraindividual/evolutionary phenomena are things like the Interstate system, while the individual/aesthetic describes art, things like painting or sculpture. Of course, the Interstate system was shaped by individuals, and art works are conditioned by collective processes. Land art, in its attempt to compete with landscape and infrastructure, is particularly dependent on resources beyond those of an individual artist:

“Sculptors are this weird, freakazoid group. I met Michael Heizer and the first thing he said was, “It’s a fucked-up profession.” I said, but you made City. What else would you want to make? And he said: “I wish I’d been a rock star. Anything is better than sculpture.” It’s like Fitzcarraldo trying to build the opera house. You drag everybody through this craziness. Public sculpture is incredibly democratic. You are giving it to people. I can’t make that money back. People don’t buy a ticket.” (Thomas Houseago)

In art history, I expect the supraindividual/evolutionary to be a matter of periodization, and the individual/aesthetic to be a story of an artistic career. Any given object can be seen as a representative either of the period that it belongs to, or of the production of a single artist.

It's worth reading things against the grain – taking something that looks like an example of a particular "style" and interpreting it, instead, as an individual work, or taking something that seems to be a work of art and interpreting it, instead, as a typical product of its time. As an example of the former strategy, which I would call "finding sculpture", one could look at the ornamental aspects of pre-modern woodworking and attempt to particularize it and recover the personal creative impulse behind it. The latter strategy entails generalizing about the piece's relationship with some impersonal Zeitgeist or Kunstwollen.

A cartwheel or a vardo might have ornamental woodwork, the result of skill with a spokeshave, akin to other forms of turned and carved treen. A canal narrowboat might have decorative paintings in the roses and castles genre. From the supraindividual perspective, these things might seem like kitsch, wasted labour or frivolity. From the individual perspective, it's more likely to seem like self-expression or creative freedom, no matter how valuable or worthless the object seems to be. Ironically, it's the supraindividual perspective that is snobbish about creative value, and the individual one that affirms human agency. Which perspective deals with the ethical and which with the expressive? I think each is a bit of both.

Baroque architecture, which art historians have characterised as "broad and heavy" (Wölffin), and "raw and deviant" (Burkhardt), produced buildings which were both individually (aberrant) and (collectively) products of a recognizable style. For me this state of affairs calls into question the usefulness of the evolutionary/aesthetic opposition. Can a style be aberrant? Is it possible for individual makers to inherit unorthodox traits from the spirit of the age?

Katharine Fritsch's 2004 sculpture Frau mit Hund plays not only with scale but with the relationship of sculpture to kitsch and individual creativity.

The sculpture is 1.75 m tall, and the woman and her dog are each monochromatic. Apart from the surprising scale, it is as if eccentric sculptures made of sea shells had been dipped into matt paint. This decision by Fritsch promotes the objects from kitsch into sculptural form. It is a kind of generalisation, which is appropriate to the (supraindividual) interpretation of the source objects as representatives of a particular kind of cultural production. Fritsch lists the materials of the sculpture as polyester, iron, and wood (along with paint). We're not informed about the authorship of the original piece (surely it exists?) but we can speculate that it was Victorian. By suppressing these personal details, Fritsch plays with the notion of the supraindividual tides of fashion and style, simultaneously foregrounding her own personal eye for form and adherence to the norms of contemporary sculpture.

0 notes

Text

Paul Nash

Last summer, I walked in a field near Avebury where two rough monoliths stand up, sixteen feet high, miraculously patterned with black and orange lichen, remnants of the avenue of stones which led to the Great Circle. A mile away, a green pyramid casts a gigantic shadow. In the hedge, at hand, the white trumpet of convolvulus turns from its spiral stem, following the sun. In my art I would solve such an equation. (Paul Nash)

'Nash wrote frequently on artistic and other matters and, as a result, we are in a good position to review his declared position on the relationship between art and archaeology. Nash wanted to champion the possibility of artists finding their own accommodation with the past, rather than being subservient to archaeological understanding. In a letter of May 1937, he talks about his intentions for his painting Equivalents for the Megaliths:

These groups (at Avebury) are impressive as forms opposed to their surroundings both by virtue of their actual composition of lines and masses and planes, directions and volumes; and in the irrational sense, their suggestion of a super-reality. They are dramatic also, however, as symbols of their antiquity, as hallowed remnants of an almost unknown civilisation. In designing the picture, I wished to avoid the very powerful influence of the antiquarian suggestion, and to insist only upon the dramatic qualities of a composition of shapes equivalent to the prone or upright stones simply as upright or prone, or leaning masses, grouped together in a scene of open fields and hills.

Equivalents for the Megaliths

[...]

Despite enjoying brief but cordial relations with Stuart Piggott and Alexander Keiller, Nash felt that Keiller’s restoration work at Avebury in the later 1930s had robbed the site of its presence and its power. The controlled experience of prehistory offered by Keiller’s restoration (megalithic landscape gardening, as Stuart Piggott later described it), seemed to Nash wrong-headed in its attempt to retrieve what time had eroded. Keiller wanted clarity where Nash wanted mystery. As he put in 1942, looking back to his first visit in 1933:

the great stones were in their wild state, so to speak. Some were half covered by the grass, others stood up in cornfields or were entangled and overgrown in the copses, some were buried under the turf. But they were wonderful and disquieting, and as I saw them then, I shall always remember them. Very soon afterwards the big work of reinstating the Circles and Avenues began, so that to a great extent that primal magic of the stones’ appearance was lost.

Nash had revisited the complex in 1938, when the restoration work was in full swing, and although acknowledging Keiller’s dedication to the project, he nevertheless insisted that Keiller’s restoration was a form of sterilisation:

Avebury may rise again under the tireless hand of Mr. Keiller, but it will be an archaeological monument, as dead as a mammoth skeleton in the Natural History Museum. When I stumbled over the sarsens in the shaggy autumn grass and saw the unexpected megaliths reared up among the corn stooks, Avebury was still alive.

Nash’s insistence on the vitality of the past is, ultimately, a plea for another sort of knowing, an alternative, even a resistance to empirical data and orthodox methodology. In their place Nash proposes a mode of engagement with prehistory that works with what cannot be known, what must be intuited. For Nash, the modern artist, precisely because s/he is free to abandon any literal representation of the world, can provide an imaginative avenue of approach to antiquity. His decision to avoid ‘the antiquarian suggestion’ in Equivalents for the Megaliths and similar pictures is thus prompted by a very real understanding of the cognitive possibilities art possesses. By finding plastic equivalents for megalithic structures Nash can offer insights that are intimately linked to his means of representation. Writing about his painting Landscape of the Megaliths 1937, loosely inspired by the West Kennet Avenue, Nash talked of Keiller and Piggott’s reactions to it and how he had emulated artistically what they had achieved in reality: ‘Yet it is odd to consider that in my design I, too, have tried to restore the Avenue. The reconstruction is quite unreliable, it is wholly out of scale, the landscape is geographically and agriculturally unsound. The stones seem to be moving rather than to be deep-rooted in the earth. And yet archaeologists have confessed that the picture is a true reconstruction because in it Avebury seems to revive.’

Similarly, in the slightly earlier Equivalents for the Megaliths Nash takes from Avebury the idea of large structures, composed of simple and repeated elements, and how their orderly array negotiates a sense of place within a wider landscape. Yet, by the same token, the contrast between his geometrical forms and the overall environment exaggerates the assertiveness of any ordered intrusion into nature. Other elements in the landscape might suggest cultural continuities, from the stepped ridges of an Iron Age hill fort to the aftermath of modern agriculture, but their conjunction with one another is made palpable only at the level of form, as devices in a pictorial composition. Nash is patently not illustrating an historical thesis; if these geometrical solids are the equivalents of prehistoric megaliths they are so by virtue of his construction of metaphorical and formal contexts, not literal ones. Indeed, a sense of surprise and discontinuity is as much a presence here as any idea of transhistorical communion. Above all, perhaps, Nash seems to insist on the impossibility of any final understanding of such a mute and incomprehensible monument, which irrupts into consciousness as from a dream.

From Matless, Landscape and Englishness

0 notes

Text

Chunks and Equivalents

There are two prominent ways of thinking about representations of data in computer systems: as chunks and as equivalents.

Chunk is a crude term for a crude perspective, and none of its synonyms is any better: lump, hunk, wedge, block, slab, square, nugget, nub, brick, cube, bar, cake, loaf, knob, ball, piece, portion, bit, mass, wodge, gob. Come on, we're not dealing with potatoes here!

Chunks represents discrete units that have an inside and an outside. A block of bytes is a chunk, but even something as small and simple as a bit is a chunk. In general a chunk is a value of a type. Chunks can be extents of storage or, for example, type-length-value blocks. Chunks can be aggregated into larger chunks. Chunks are pretty concrete.

Equivalents, on the other hand, are abstract. They are the result of "description by omission". Equivalents have some specified property, which might be as basic as "presence". Equivalence evokes bureacratic processing. Every holder of a Social Security Number is equivalent in precisely that sense. Every Irish passport holder is equivalent, in the specified sense, with every other Irish passport holder. We might know literally nothing else about these individuals. That's the convenience of abstraction.

Talk about chunks is inadequate when we want to capture a phenomenon such as assimilation. The concept of equivalence, on the other hand, immediately conveys what's at stake when diverse individuals are assimilated and become "equal in the eyes of the law", or interchangeable in the terms of the system under discussion. This property is only weakly and implicitly conveyed by the notion of chunked storage. I think the superiority of chunks in this case just amounts to an appropriate use of abstraction.

0 notes

Text

Vector spaces are never going to provide a model for hybridity, for intricate mechanisms or for emergent properties.

0 notes

Text

Encroachment

The English author Alan Garner is a territorial man. He seems to have wedged himself, years ago, in a cleft deep beneath Alderley Edge, from which position he has been declaiming. His books tell stories of adventure in the Cheshire landscape, but adventure confined in scope to the mythic past of the protagonists. He somehow identifies his own troubled mind with the landscape, a kind of chthonic sturm und drang. He is a local, a country boy, who has said "I loathe crowds. I especially don't like cities. A city involves biomass. And biomass gets to me." Biomass? It's a neologism that Garner isn't quite using correctly. He may not be trying to make a misanthropic statement: people considered as biomass lack individuality, and Garner is preoccupied with individuality. He set out to be an artist, but writes books because he doesn't draw or paint. His ancestors may have been craftsmen, but he has taken the individualistic life of the artist to an extreme.

This I got from my grandfather. He was a craftsman, and he gave me two precepts which as a writer I've not been able to get away from. One was always take as long as the job tells you to take, because the job will be there when you are not, and you don't want people to say, what fool did that? So I'm a very slow worker. The other precept was if the other chap can do the job, let him. In other words, do only what is uniquely yours.

Whether the task is making a cart wheel or a novel, this perspective is perfectionistic and egocentric. Garner is an author in the old-fashioned sense: a man whose identity and celebrity is inextricably bound up with his books.

As a man who dislikes modernity, and prefers to contemplate "deep time" (whatever that is), Garner lives very close to some modern infrastructure. The Manchester branch of the West Coast Mainline runs past the bottom of his garden. It was the first stretch of the line to be electrified. Since the beginning, though, passenger railways have had the effect of taking traffic off rural roads, so the railway aids his retiring lifestyle. Less than a mile away from his house is the Lovell radio telescope at Jodrell Bank. This is an exotic, spindly structure with a huge white dish. A radio telescope is such an anomalous use of land that Garner seems to accept it as an exotic, almost nonhuman installation, and trades on its proximity in his later books.

I sense that he would be less sanguine about the encroachment of other forms of technology on his landscape. Anything from over the horizon is suspect. What would he think if the stalks of white wind turbines started an assertive march across the fields? Without the strangeness of the radio telescope or the established and acceptable quid-pro-quo of the railway, the turbines would be an evolutionary development that doesn't fit into his mythic landscape. Their utilitarian high-tech genericity (identical machines with interchangeable parts) has nothing to do with an author's poetic high individualism.

For all his weirdness, though, Alan Garner is a modern man. From his use of 1960s cant ("biomass") to his absolute pursuit of personal creativity, and his amateur practice of archaeology (some kind of version of the imperative to "dig where you stand"), he lives in a way that would be unrecognisable to his forbears and their rural folk culture.

I see him as more akin to someone like the surrealist Paul Nash, who found strangeness in the English landscape. In 1939, Nash wrote of a place he called Monster Field:

Have you ever known a place which seemed to have no beginning and no end? Such was Monster Field. Although I went there two or three times, I could never remember the way. How do we get to Monster Field? I would ask. Or, we would be motoring miles from home in what seemed to me an unfamiliar part of the country when, suddenly, my companion would murmur –Monster Field. Where, where? Over there, to the left, the next field beyond the hedge. It was always the same, elusive and ubiquitous. We called it Monster Field for an obvious reason. Upon the surface of its green acres which flowed curiously like a wide river over the uplands, there jutted up, as if wading across the tide, two stark objects. They were the remains of two trees, elms, I think, felled by lightning during a furious storm some years ago. So violent had been their overthrow that, utterly, the roots of one had been torn out of the ground. The other had broken off from a splintered shaft upon which it was leaning, its great limbs sprawled backwards over the grass. Both trees were by now bleached to a ghastly pallor wherever the bark had broken and fallen away. At a distance, in sunlight, they looked literally dead-white, but, at close range, their surfaces disclosed many inequalities of tone and subtle variety of ashen tints. Also, in many places the bark still clung, a rich, dark plum-coloured brown. Here and there the smooth bole, gouged by the inveterate beetle, let out a trickle of yellow dust which mingled with the red earth of the field.

Unlike Garner, Nash was a visual artist, and the distinctive palette of his paintings is readily identified in the colours he describes here. Both men look at the landscape with heightened perception. They're not farmers or workers on the land; their concerns are intellectual, as much psychological as aesthetic. They pursue a terrible clarity, a stark vision of familiar territory made strange. This strangeness is ominous but ahistorical. The danger is ancient, or maybe futuristic.

0 notes

Text

When formally modelling or describing modularity, it's more precise to consider modules as overlapping at shared interfaces than to consider them as mutually exclusive objects that happen to be adjacent to each other.

1 note

·

View note