Text

On the music of the spheres: "Whether the sound of this vast mass whirling in unceasing rotation is of enormous volume and consequently beyond the capacity of our ears to perceive, for my own part I cannot easily say – any more in fact than whether this is true of the tinkling of the stars that travel round with it, revolving in their own orbits; or whether it emits a sweet harmonious music that is beyond belief charming. To us who live within it the world glides silently alike by day and by night."

-Pliny the Elder, A.D. 77

0 notes

Photo

“Beams of sunlight streaming through the windows at Grand Central Station, New York City, circa 1930. (Photo by Hal Morey/Getty Images)”

0 notes

Text

Let me now say something about what the word ‘solitude’ means. We know three solitudes in society. We know a solitude imposed by power. This is the solitude of isolation, the solitude of anomie. We know a solitude which arouses fear on the part of those who are powerful. This is the solitude of the dreamer, of the homme révolté, the solitude of rebellion. And finally, there is a solitude which transcends the terms of power. It is a solitude based on the idea of Epictetus that there is a difference between being lonely and being alone. This third solitude is the sense of being one among many, of having an inner life which is more than a reflection of the lives of others. It is the solitude of difference.

Each of these solitudes has a history. In the ancient world, the solitude imposed by power was exile; in 17th-century France, the solitude imposed by power was banishment to the countryside. In a modern office, the solitude created by power is a sense of loneliness in the midst of the mass. In the ancient world, the detached dreamer whom the powerful feared was a Socrates, one who set against the laws of the state a discourse of superior law, an ideal against an established order of power. The modern homme révolté, an Artaud or a Genet, sets against the order of power the truth of lawlessness. The solitude of difference, of an inner life more than the reflections of other lives, is similarly historical.

— Richard Bennett, “Sexuality and Solitude” London Review of Books (1981).

0 notes

Text

Let me tell you a little story. There was once a young man who dreamed of reducing the world to pure logic. Because he was a very clever young man, he actually managed to do it. And when he'd finished his work, he stood back and admired it. It was beautiful. A world purged of imperfection and indeterminacy. Countless acres of gleaming ice stretching to the horizon. So the clever young man looked around the world he had created, and decided to explore it. He took one step forward and fell flat on his back. You see, he had forgotten about friction. The ice was smooth and level and stainless, but you couldn't walk there. So the clever young man sat down and wept bitter tears. But as he grew into a wise old man, he came to understand that roughness and ambiguity aren't imperfections. They're what make the world turn. He wanted to run and dance. And the words and things scattered upon this ground were all battered and tarnished and ambiguous, and the wise old man saw that that was the way things were. But something in him was still homesick for the ice, where everything was radiant and absolute and relentless. Though he had come to like the idea of the rough ground, he couldn't bring himself to live there. So now he was marooned between earth and ice, at home in neither. And this was the cause of all his grief.

— Derek Jarman, Wittgenstein (1993)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A DOVER EDITION DESIGNED FOR YEARS OF USE!

We have made every effort to make this the best book possible. Our paper is opaque, with minimal show-through; it will not discolor or become brittle with age. Pages are sewn in signatures, in the method traditionally used for the best books, and will not drop out, as often happens with paperbacks held together with glue. Books open flat for easy reference. The binding will not crack or split. This is a permanent book.

— back cover of Dover Publications paperback

0 notes

Photo

— David Byrne, “Social Information Flow” from Arboretum (2006)

0 notes

Text

Whenever they start to blame themselves, respond by blaming the computer. Then keep on blaming the computer, no matter how many times it takes, in a calm, authoritative tone of voice. If you need to show off, show off your ability to criticize bad design. When they get nailed by a false assumption about the computer's behavior, tell them their assumption was reasonable. Tell *yourself* that it was reasonable.

— Phil Agre, “How to help someone use a computer” (1996)

0 notes

Text

Le goût des algorithmes ~ The taste for algorithms

He has never worked out real algorithms; there was a moment when he fell back on less arduous formalizations (but this moment seems to have passed): what seemed to be simple equations, schémas, tables, genealogical trees. Such figures, in fact, are of no use whatever; they are simple toys, the analogue of the dolls made out of a comer of one's handkerchief: one plays for oneself: Zola, in the same way, makes himself a plan of Plassans to explain his novel to himself. Such diagrams, he knows, even fail to have the interest of locating his discourse under the aegis of scientific reasoning: whom could they deceive? Yet one plays at science, one puts it in the picture—like a piece in a collage. In the same way, calculation—from which pleasure was to be derived—was placed by Fourier in a phantasmatic series (for there are fantasies of discourse).

— Barthes, Roland Barthes (1977)

0 notes

Photo

“Levi-Strauss's personal views on art have not, to my knowledge, been adopted by any artist as an explanation or justification of his work. None the less, Structuralism poses real issues for art and artists. It has sometimes been used as an intellectual justification for such movements as Earth Art, Post-Object Art and Conceptual Art [10]. (It seems that the West is in so verbal an epoch that labelling is tantamount to validation.) To indicate the problem in very few words, structural analysis may be said to be based largely on binary oppositions usually taken in pairs. In a diagram, the binaries would appear as the vertical and horizontal axes. The result of the analysis is usually a triangular scheme of a dichotomy and a mediating middle term. (A remarkably clear demonstration is to be found in Leach.) Inasmuch as Levi- Strauss states that music, like verbal language, is a mediation between nature and culture, it is possible to draw the triangle shown in Fig. 1. The term 'language' may give place to 'music', 'myth' or 'art'. The argument for the art movements mentioned above starts with the culture/nature binary; the problem arises with the other axis and the third, or mediating, term. Artists themselves, products of both culture and nature, might be considered (but the better term would then be 'human beings')- which makes the diagram tautological. It has been proposed that artists intervening in nature produce, at least, a sign of art; in this sense the three letters a r t are equally significant. In sum, analysis reveals that the binary nature/culture is merely replaced by nature/art (or art/culture?). Not only has nothing been gained by the interchanges, the terms are not 'structurally' valid. It is difficult to see how Structuralism can justify these movements. Similar misreadings and misinterpretations by interpreters of art have led to similar distortions of the analysis.

[...]

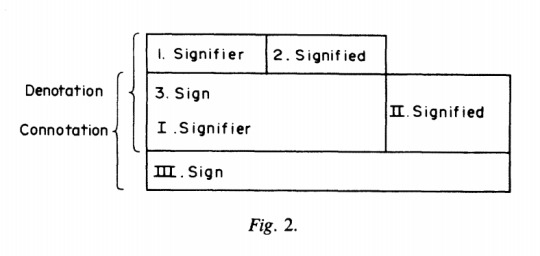

This is best explained by means of the diagram shown in Fig. 2 [14]. Demonstrated here is the manner in which a first-order sign becomes the signifier for a new concept that results in a second-order sign. This operation, incidentally, is precisely what Barthes maintains occurs in the formation of myths. In a broader perspective, this diagram (and the argument supporting it) suggests that to be considered art, any language must pass from denotation to connotation. If Levi-Strauss's definition is now read as indicating a second-order signification, it begins to make sense, because the object, or rather the depiction of the object, has moved to another conceptual plane with a new signification. But is this what he meant?

The figurative bias of Levi-Strauss's aesthetics could appear partially justified; yet the investigation of art in linguistic terms suggests, nonetheless, that a painting can be considered a system of relations of signs and/or symbols. Already mentioned is Levi-Strauss's description of the structuralist approach to understanding social activities as a matter of reducing phenomena to their underlying nature as symbolic systems. Were this approach to focus on a painting (which can be seen to be analogous to society in such contexts as, for example, synchrony, conformity to rules and organization of interaction), then the data in the painting could be similarly reduced to a symbolic system. In fact, is this not precisely what viewers do even though not on a conscious level? Is this not part of the process of deriving the connotative from the denotative? In the paragraph quoted, Levi-Strauss states that 'symbols are more real than that which they symbolize .. .'. If, for example, the depiction of a man-a symbol-is more real than what it symbolizes, in order to avoid contradiction, it would follow that its underlying function in the painting is other than to symbolize a man, real or imaginary. In their aesthetic function, then, familiar objects, such as humans, buildings and landscapes, could be replaced in a painting by abstract shapes without a major change in the rules and still retain the intelligibility of the relational system. Levi-Strauss concludes his sentence with the puzzling (because of its inversion) statement that 'the signifier precedes and determines the signified'. I suggest that, without realizing it, he has here touched on the ontological core of all the creative arts. The communicative intention of artists, ambiguous at best, requires an effort of imaginative re-construction by 'the silent performers', the viewers. It is precisely because the 'message' is unclear that viewers, faced with a given set of signifiers, must determine the set of signified.”

— Art Brenner, “The Structuralism of Claude Levi-Strauss and the Visual Arts” (1977)

1 note

·

View note

Text

“To contemplate one's kettle and suddenly realize, first, that one is the beneficiary of an unimaginably vast and complex social whole and, second (a point further emphasized elsewhere in the novel*), that this means benefiting from the daily labor of the kettle- and electricity-producing workers, much of it unpleasant and underremunerated, is not entirely outside everyday experience. What seems special about the passage is a third realization: that this moment of consciousness will not be converted into action. [...] ‘That in comparison with which everything else is small’ is one of Kant's descriptions of the sublime, also defined as "a feeling of the inadequacy of [the] imagination for presenting the ideas of a whole, wherein the imagination reaches its maximum, and, in striving to surpass it, sinks back into itself, by which, however, a kind of emotional satisfaction is produced" (88, 91). Considering how Lodge and Chast** play up and down the scales of the immensely large and infinitesimally small, how they combine pleasure with pain in contemplating the obscure infinity of the social whole, and above all the paradox of their making us sense that we possess transcendent powers (albeit powers exercised on our behalf and in this case without our active will) yet finally letting us "sink back into ourselves," so that we fail to express those powers in any potentially risky, disobedient action, I suggest that we provisionally call this trope, with a certain inevitable discomfort, the sweatshop sublime.”

— Bruce Robbins, “The Sweatshop Sublime” (2002) · · · *David Lodge’s Nice Work **Roz Chast “One Morning While Getting Dressed” cartoon

1 note

·

View note

Photo

— Christoph Niemann, “The Enduring Romance of the Night Train”

0 notes

Text

Such changes can be defined as changes in structures of feeling. The term is difficult, but ‘feeling’ is chosen to emphasize a distinction from more formal concepts of ‘world-view’ or ‘ideology’. It is not only that we must go beyond formally held and systematic beliefs, though of course we have always to include them. It is that we are concerned with meanings and values as they are actively lived and felt, and the relations between these and formal or systematic beliefs are in practice variable (including historically variable), over a range from formal assent with private dissent to the more nuanced interaction between selected and interpreted beliefs and acted and justified experiences. An alternative definition would be structures of experience: in one sense the better and wider word, but with the difficultly that one of its senses has that past tense which is the most important obstacle to recognition of the area of social experience which is being defined. We are talking about characteristic elements of impulse, restraint, and tone; specifically affective elements of consciousness of a present kind, in a living and interrelating continuity. We are then defining these elements as a ‘structure’: as a set, with specific internal relations, at once interlocking and in tension. Yet we are also defining a social experience which is still in process, often indeed not yet recognized as social but taken to be private, idiosyncratic, and even isolating, but which in analysis (though rarely otherwise) has its emergent, connecting, and dominant characteristics, indeed its specific hierarchies. These are more often more recognizable at a latter stage, when they have been (as often happens) formalized, classified, and in many cases built into institutions and formations. By that time the case is different: a new structure of feeling will usually already have begun to form, in the true social present.

Methodologically, then, a ‘structure of feeling’ is a cultural hypothesis, actually derived from attempts to understand such elements and their connections in a generation or period, and needing always to be returned, interactively, to such evidence.

— Raymond Williams, “Structures of Feeling” in Marxism and Literature (1977)

0 notes

Text

It's all associative. It's all about relation. What is the relationship between the thing that's in front of you, the thing that proceeded, and the thing that's following? The whole idea was always if you took this thing and that thing and you overlap them, the place in which they overlapped was you.

— Arthur Jafa, in conversation with MOMA

0 notes