A network dedicated to The Last Hours, an upcoming trilogy by Cassandra Clare. Chain of Gold, The Last Hours #1 out 3 March 2020!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

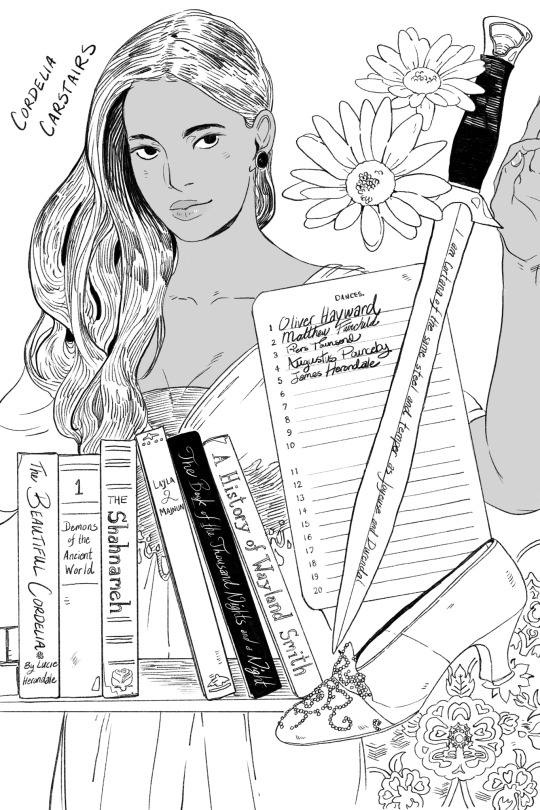

Cordelia! I love loved her more than I expected. She’s lovely 💞

This is the finale of the Chain of Gold sketchbook series! I hope you guys enjoyed them! Thank you for all your comments!

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

James J a m e s J a M e S!!!!

Please come sit by me so I may feed you cookies and make it all better.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Grace Blackthorn! Just two pages left to go.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Christopher Lightwood!

A messy page for a messy young man with lots of messy ideas! (And a lemon tart)

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

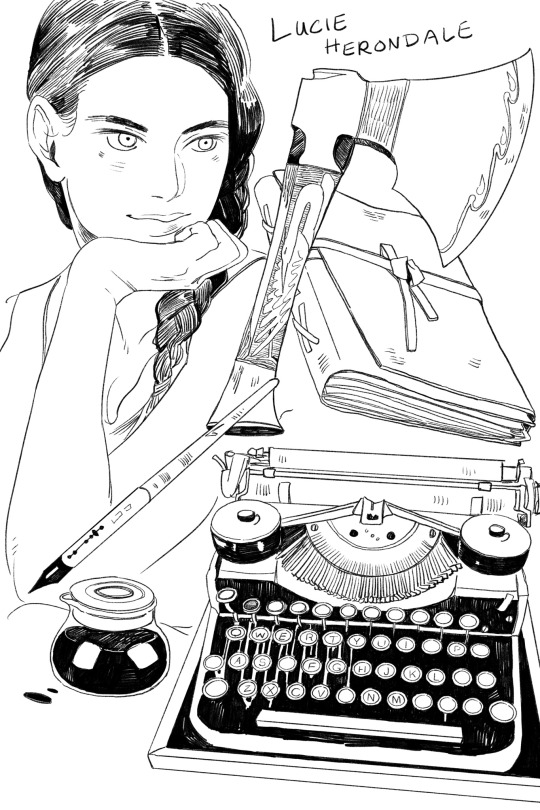

Lucie Herondale! An absolute 100% genuine cutie.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

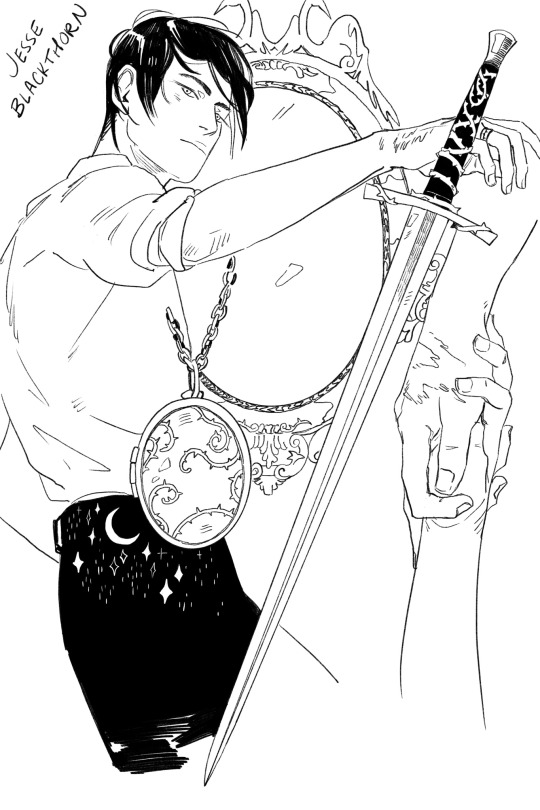

Jesse Blackthorn ~ my heart went out to him...

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Prologue and first chapter of Chain of Gold!

The prologue and first chapter of Chain of Gold are now available to read! You can check out the prologue below, in which a young Lucie Herondale makes a surprising discovery. The link to Chapter One is included at the end of it. Those of you who have seen the earlier chapter sampler may still want to check it out, as the prologue wasn’t originally included in the sampler, and changes have been made to Chapter One since the old copy came out.

Prologue

DAYS PAST: 1897

Lucie Herondale was ten years old when she first met the boy in the forest.

Growing up in London, Lucie had never imagined a place like Brocelind. The forest surrounded Herondale Manor on all sides, its trees bent together at the tops like cautious whisperers: dark green in the summer, burnished gold in the fall. The carpeting of moss underfoot was so green and soft that her father told her it was a pillow for faeries at night, and that the white stars of the flowers that grew only in the hidden country of Idris made bracelets and rings for their delicate hands.

James, of course, told her that faeries didn’t have pillows, they slept underground and they stole away naughty little girls in their sleep. Lucie stepped on his foot, which meant that Papa swept her up and carried her back to the house before a fight could erupt. James came from the ancient and noble line of Herondale, but that didn’t mean he was above pulling his little sister’s plaits if the need arose.

Late one night the brightness of the moon woke Lucie. It was pouring into her room like milk, laying white bars of light over her bed and across the polished wood floor. She slipped out of bed and climbed through the window, dropping lightly to the flower bed underneath. It was a summer night and she was warm in her nightdress.

The edge of the forest, just past the stables where their horses were kept, seemed to glow. She flitted toward it like a small ghost. Her slippered feet barely disturbed the moss as she slid in between the trees.

She amused herself at first by making chains of flowers and hanging them from branches. After that she pretended she was Snow White fleeing from the huntsman. She would run through the tangled trees and then turn dramatically and gasp, putting the back of her hand to her forehead. “You will never slay me,” she said. “For I am of royal blood and will one day be queen and twice as powerful as my stepmother. And I shall cut off her head.”

It was possible, she thought later, that she had not remembered the story of Snow White entirely correctly.

Still, it was very enjoyable, and it was on her fourth or fifth sprint through the woods that she realized she was lost. She could no longer see the familiar shape of Herondale Manor through the trees.

She spun around in a panic. The forest no longer seemed magical. Instead the trees loomed above like threatening ghosts. She thought she could hear the chatter of unearthly voices through the rustle of leaves. The clouds had come out and covered the moon. She was alone in the dark.

Lucie was brave, but she was only ten. She gave a little sob and began to run in what she thought was the right direction. But the forest only grew darker, the thorns more tangled. One caught at her nightdress and ripped a long tear in the fabric. She stumbled—

And fell. It felt like Alice’s fall into Wonderland, though it was much shorter than that. She tumbled head over heels and hit a layer of hard-packed dirt.

With a whimper, she sat up. She was lying at the bottom of a circular hole that had been dug into the earth. The sides were smooth and rose several feet above the reach of her arms. She tried digging her hands into the dirt that rose on every side of her and climbing up it the way she might shinny up a tree. But the earth was soft and crumbled away in her fingers. After the fifth time she’d tumbled from the side of the pit, she spied something white gleaming from the sheer side of the dirt wall. Hoping it was a root she could climb up, she bounded toward it and reached to grasp it… .

Soil fell away from it. It wasn’t a root at all but a white bone, and not an animal’s …

“Don’t scream,” said a voice above her. “It’ll bring them.”

She threw her head back and stared. Leaning down over the side of the pit was a boy. Older than her brother, James—maybe even sixteen years old. He had a lovely melancholy face and straight black hair without a hint of curl. The ends of his hair almost touched the collar of his shirt.

“Bring who?” Lucie put her fists on her hips.

“The faeries,” he said. “This is one of their pit traps. They usually use them to catch animals, but they’d be very pleased to find a little girl instead.”

Lucie gasped. “You mean they’d eat me?”

He laughed. “Unlikely, though you could find yourself serving faerie gentry in the Land Under the Hill for the rest of your life. Never to see your family again.”

He wiggled his eyebrows at her.

“Don’t try to scare me,” she said.

“I assure you, I speak only the perfect truth,” he said. “Even the imperfect truth is beneath me.”

“Don’t be silly, either,” she said. “I am Lucie Herondale. My father is Will Herondale and a very important person. If you rescue me, you will be rewarded.”

“A Herondale?” he said. “Just my luck.” He sighed and wriggled closer to the edge of the pit, reaching his arm down. A scar gleamed on the back of his right hand—a bad one, as if he had burned himself.

“Up you go.”

She grasped his wrist with both her hands and he hauled her up with surprising strength. A moment later they were both standing. Lucie could see more of him now. He was older than she’d thought, and formally dressed in white and black. The moon was out again and she could see that his eyes were the color of the green moss on the forest floor.

“Thank you,” she said, rather primly. She brushed at her nightdress. It was quite ruined with dirt.

“Come along, now,” he said, his voice gentle. “Don’t be frightened. What shall we talk about? Do you like stories?”

“I love stories,” said Lucie. “When I grow up, I am going to be a famous writer.”

“That sounds wonderful,” said the boy. There was something wistful about his tone.

They walked together through the paths under the trees. He seemed to know where he was going, as if the forest was very familiar to him. He must be a changeling, Lucie thought wisely. He knew a great deal about faeries, but was clearly not one of them: he had warned her about being stolen away by the Fair Folk, which must be what had happened to him. She would not mention it and make him feel awkward; it must be dreadful to be a changeling, and to be taken far away from your family. Instead she engaged him in a discussion about princesses in fairy tales, and which one was the best. It hardly seemed any time at all before they were back in the garden of Herondale Manor.

“I imagine this princess can make her own way back into the castle from here,” he said with a bow.

“Oh, yes,” said Lucie, eyeing her window. “Do you think they’ll know I was gone?”

He laughed and turned to go. She called after him when he reached the gates.

“What’s your name?” she said. “I told you mine. What’s yours?”

He hesitated for a moment. He was all white and black in the night, like an illustration from one of her books. He swept a bow, low and graceful, the kind knights had once made.

“You will never slay me,” he said. “For I am of royal blood and will one day be twice as powerful as the queen. And I shall cut off her head.”

Lucie gave an outraged gasp. Had he been listening to her, in the woods, playing her game? How dare he make fun of her! She raised a fist, meaning to shake it at him, but he had already vanished into the night, leaving only the sound of his laughter behind.

It would be six years before she saw him again.

Click here to read Chapter One over at Riveted Lit!

(You need an account to read, but it’s free to sign up.)

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charlie Bowater’s portrait of Jesse Blackthorn! I love the way she shows him fading very slightly into insubstantiality at the edges…and the Blackthorn locket, of course. He died before he could be fully runed, but he does have a Voyance scar on his hand.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Alastair Carstairs is a character I went into the book prepared to be thoroughly annoyed by and then about halfway through wanted to just give him lots of candy. Which he probably wouldn’t have appreciated.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Anna Lightwood. She is so dang cool I aspire to her level of self confidence and sass.

I really adore the lineup of characters in Chain of Gold.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Thomas Lightwood is my personal favorite from Chain of Gold. Such a big ol’ teddy bear

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

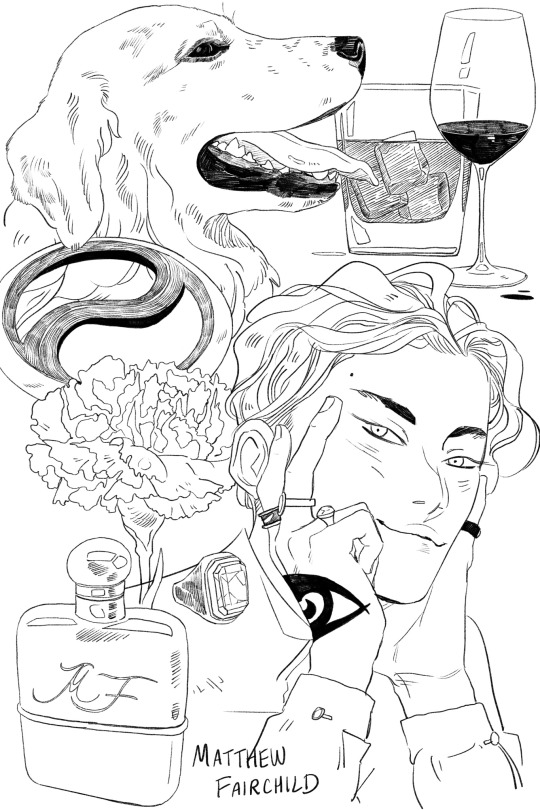

Chain of Gold sketchbook!!

So I had the pleasure of reading Chain of Gold by @cassandraclare early and I am going to draw sketchbook pages for each of the characters!

Starting with Matthew Fairchild

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

DECEMBER’s Chain of Gold Flash Fiction by Cassandra Clare

A Lightwood Christmas Carol

PART 2

“So,” Gideon said to Will the next night as they patrolled together in Mayfair, “the whole thing was a wash. I’m not murdering some poor bastard’s dog.”

Patrol with Will was normally a relaxing experience for Gideon. They enjoyed each other’s company, and demons had become so scarce in London that almost all of the time it was only a night stroll with a friend. Will even periodically recommended that they investigate for any suspicious activity in some local public house known to him.

Tonight, of course, there would be no ordering a quick round as a cover story for interrogating, i.e. merrily chatting up, the barstaff; Will was far too full of Christmas spirit. He had insisted on taking them by Trafalgar Square and spent many minutes in admiration of its temporary giant tree, and had stopped—twice!—to admire groups of carolers and applaud them. Gideon was bearing up well, he thought, considering. He even got into the spirit a very tiny amount, which is to say he was willing to eat some of the roast chestnuts Will bought.

Now Tatiana (and the dog news) had deflated Will’s mood, and Gideon felt a little badly about it. Will was frowning thoughtfully. “Why not just offer her money?” he said.

Gideon sighed. “Because Tatiana has plenty of money, all of our family money. And Gabriel and I have only our salaries as Shadowhunters. She doesn’t need money.”

Will looked scornful. “Everybody likes more money.”’

“Normally I would agree with you,” Gideon said, shaking his head, “but you did not see Tatiana’s state of mind. She cannot be approached in the way you would approach a rational person. I must do this task for her, but of course I cannot. Hurt a dog, of all things. I would never. Disgusting.”

Will stood looking past him for a long moment, and eventually Gideon said, “Will?”

“We will take care of it,” Will suddenly said. His gaze snapped back to Gideon’s face, and he was smiling. “We will give Tatiana what she wants, and we will not hurt any animals in the process.”

“We?” said Gideon, raising his eyebrows.

“Well, it’s my plan,” Will said reasonably. “So obviously I’ll be along.”

Despite himself, a smile played at the edges of Gideon’s mouth. That was the one thing he had over Tatiana, after all. He wasn’t alone.

#

The front door of Chiswick House swung open with somewhat more speed than it had two days prior, and Tatiana’s suspicious face appeared. She was wearing the same dress she had been wearing before, to Gideon’s dismay. In her left hand she carried the cleaned skull of some unidentifiable small mammal; Gideon didn’t wish to inquire why.

Tatiana’s glare quickly moved from Gideon to Will, who was bopping up and down nervously behind him. Will had insisted on coming, against Gideon’s better judgment, and only now did he realize the possibility that Tatiana might not even see him if Will was along.

Will, for his part, did his best. “Hullo, Tatiana my love,” he said. “Many greetings of the season! How excellently you’ve kept up the place.”

Tatiana blinked at him, startled out of whatever she had been about to shout. Gideon knew that Will had three good nips of brandy in him, and reckoned that was probably the best way to handle the situation. Meet the unexpected with the unexpected.

“Why have you brought my nemesis to my house?” Tatiana said, in the same tone she might have used if she were asking why Gideon had failed to return a book he’d borrowed.

“Crikey,” said Will. “Nemesis? Tatiana, I bear you no ill will. Have I ever, even once, interfered with your life? With your going about your business?”

“Yes,” said Tatiana. “Twice. Once when you murdered my husband, and once when you murdered my father.”

Will made a choked noise. “I murdered your father because he murdered your husband! And I didn’t murder him, he’d changed into some kind of great serpent.”

“A worm, Will,” said Gideon quietly. “He was a giant worm. Not a serpent.”

“As I remember,” said Will, “it were a great wyrm, from the depths of the Abyss, that we dispatched.”

“It was not,” said Gideon.

“It was my father,” ground out Tatiana, “and I wish to know, Gideon, why you have brought him here? I asked you to perform a task for me.”

“And I have performed it,” Gideon said briskly. “Mr. Herondale was good enough to come along, to help protect me from this most vicious of dogs that you described.”

“It’s actually quite vicious,” Will agreed.

“If you’ll just let us come in,” Gideon said.

Tatiana squinted at both of them as if trying to see through a possible glamour. “Well, come in, then. But you won’t get tea.”

“Tatiana,” Will said with an understanding chuckle. “There’s obviously no way I would ever consume any food or drink at your house.”

This was going rather well, Gideon thought.

Ensconced back in his father’s office, with no tea offered nor taken, Tatiana said, “Well?”

Gideon reached into his jacket and lay a dog’s collar, a weathered length of leather cord, down on the desktop with a flourish.

Tatiana looked at it and then up at him. “What is this?”

“It is the dog’s collar,” Gideon said. “A trophy of our dispatching it.”

She looked at it again. “This tells me nothing. You could simply have taken the collar off of that dog.”

“Madam,” said Will, “if I may? No man could possibly have taken the collar off of that dog. I would advise no man to put their hand within several feet of that dog’s neck, if they wish to retain said hand. Now that that collar is off, no man could ever put it back on.” He spoke in serious tones.

“I need something more,” Tatiana said. “If you killed the dog, you must know where it is. Go back and bring me the dog’s tail, or something.”

“Tatiana,” Gideon began, but Will interrupted.

“If I may again,” he said, “the dog resides on the far side of the very tall and very pointy iron fence that stands between the dog’s property and the road. Climbing over that fence at all is a feat that I would advise only the most well-trained of Shadowhunters to attempt once, and I would recommend they do it empty-handed, rather than carrying some random bit of dog. I’m afraid that the collar will have to suffice.”

Tatiana sat back and shook her head, dissatisfaction wrinkling her mouth. “Proof that you have dispatched the dog,” she said, “and not merely that you have encountered it.”

Gideon waited for Will to jump in again, but Will was silent. He seemed unsure how to proceed. Finally, he said, “Tatiana, give him the papers. Because it’s Christmas.”

“What?” said Gideon in disbelief.

Tatiana looked at Will with loathing. “Mundane holidays are meaningless to me.”

“I should have guessed, yes,” muttered Will.

“Please,” said Gideon, at the end of his rope. “My son—he’s…he’s like your son.” Tatiana stared at him in silence for a moment, so he pressed on. “He’s…he’s very small, and he’s often ill, and we worry about his survival. We worry about when we will put Marks on him. Like you do, with your son.”

Tatiana continued to watch Gideon in silence with a lizard-like stare.

“I know we do not see eye-to-eye on our family history,” he said doggedly, and ignored Will’s quiet hmph! from beside him. “But we are family nevertheless, and we may both have…inherited something. From our father. Something we’ve now passed to our sons. I must look through the papers to see if there is any clue there.”

She stared for a long and agonizing moment, and then she said, “Get out of my house.”

“Tatiana,” he began.

“How dare you compare your son and mine!” she said, her voice rising in volume. “Anyone could guess where the weakness in your son originates, and it is obviously with your decision to mix your blood with the most mundane you could find!” Her voice had risen to a shout.

“Sophie is an Ascended Shadowhunter!” Will shouted back, staunchly, and Gideon realized he was happy that Will was there.

“I don’t care!” Tatiana shouted. “My son is of the blood of two of the oldest of the Shadowhunter families. He is not weak like your son. Go back to your weakness, Gideon. Get out of my sight, get out of my house, and do not darken my door again. I have not missed your company, nor your brother’s, and I am relieved that my child will not grow up under the corrupting influence of either of you.”

Gideon made to stand up, but Will said “Tatiana, if I may yet again,” and he sat back down. Tatiana glowered at him. “I think,” Will went on, in a newly serious tone, “that if you and I could step outside into the hallway for a moment and talk in private—just for a moment. Give me three minutes, that is all. And after that, we will depart and we promise never to return. Right, Gideon?”

Gideon did not much wish to promise never to return to the house he’d grown up in, so he only said, “Whatever you wish.”

Tatiana examined Will’s face carefully, and then said, “You have two minutes, starting from this moment.” She rose from her seat and made for the door.

“Will, what are you—” Gideon began.

Will put the tip of his finger to his lips to quiet Gideon. “Trust me,” he said. “I believe that I can create a Christmas miracle.”

Helplessly Gideon watched his sister and his friend depart and close the door behind them. The seconds ticked by. Two minutes passed, then another two, then three more.

Then Tatiana came back into the room, followed by Will. Gideon tried to read Will’s expression, but it was neutral, nonchalant.

In Tatiana’s hands were two notebooks, packed with loose papers supplementing their own contents. Their covers, and the loose pages, were densely smeared with soot. “The papers of Benedict Lightwood,” she said. “You do not deserve them. And I am not gifting them to you. They are part of the house, and the house is mine, and they are also mine. You shall have them to peruse or copy at your leisure for the term of one week, and if they are not returned by that date, in their original condition, may the Angel have mercy on your souls. Both of you,” she added in Will’s direction.

Will threw up his hands in surrender. “I really just came for the dog-wrestling.”

Wondering, Gideon took the papers from her. He turned to look at Will, who murmured to him, “A Christmas miracle,” with a small smile.

#

“Come now,” Gideon said in the carriage on the way back from Chiswick, “what did you say to Tatiana to make her concede?”

It was snowing, that rare snow with very little wind, so flakes fell in a picturesque fluttering, rather than battering at the carriage like they might have as they made their way through Hammersmith, back in the direction of Central London. Will leaned back in his seat and gazed out the window.

“Well, if you must know,” he said, “I delivered an extremely well-considered speech, touching on the topics of the importance of family, the virtue of forgiveness, the need for all Shadowhunters to be allied in the fight against demons, the smallness of the sacrifice being asked of her, the pointlessness of revenge, and, of course, the giving nature of the season.”

“Oh?”

“Yes,” said Will eagerly. “And then, I counted banknotes totalling two hundred British pounds sterling directly into her hand.”

“Will!” said Gideon, shocked.

“I told you,” Will said airily. “Everyone likes money. Even mad revenge-seeking sisters, with the dried blood of their husbands on their frocks, like money.”

Gideon was flummoxed. It was an enormous sum. “You didn’t have to do that, Will,” he said. “She doesn’t deserve the money.”

“What she doesn’t deserve,” Will said hotly, “is the moral victory. It was money well-spent to be gone from that house.”

Gideon opened the journals, marveling at Will Herondale. His financial standing was better than Gideon’s own, surely, but two hundred pounds was an enormous amount of money, well more than Will could throw away on a lark. And yet he’d not hesitated to wield that money for Gideon’s sake, had in fact, Gideon now realized, brought the money with him on purpose.

So strange, Gideon thought with a sidelong look at Will, who continued harrumphing to himself quietly in victory. At this moment this boy he’d despised as a child was more his family than his own actual sister. And he found he was able to accept that. A Christmas miracle indeed.

“I really had better return these to Tatiana in a week,” he said, examining the journals again before he started reading. “Or she’s like to set a demon on me.”

Will chuckled. “Ha. Maybe she would at that.”

Gideon paused. “She might, you know. All jokes aside. It’s a legitimate possibility.”

“It is,” agreed Will, a little more grimly.

Minutes passed, during which Gideon skimmed the papers, frowning. After a time he found himself back at the beginning, and he wrinkled his brow, bemused.

Will turned back from where he had been watching the Bath Road go by. “What is it?” he said.

“There’s nothing here,” Gideon said, frustrated. “Plenty of terrible things, of course. My father was a…a…” He struggled for the right word.

“Monster?” suggested Will.

“Pervert,” said Gideon carefully. He shuffled through the pages until he found one that was only an elaborate diagram his father had made up in pencil and showed it to Will.

Will blinked at it. “Jiminy,” he said.

“But there’s nothing here that would cause weakness or fragility in his descendants,” Gideon went on. “No curses, no hexes, no demon poisons….”

“Only the pox, then,” Will said dryly.

“Yes, but that isn’t hereditary,” Gideon said. “We looked into that years ago for our own sakes.” He shuffled the papers. “All that trouble, and for nothing. Thomas remains frail and I remain unable to do anything for him.”

There was a silence and then Will said, “Gideon, it is Christmastime, and Christmas is a time to tell the truth. Wouldn’t you agree?”

“If you say so,” Gideon said, waving his hand. From his experience Christmas a time to sing in the street and eat a goose, but who knew what strange traditions Will had from his mundane childhood. “In any event, I’d agree you should tell the truth whatever the time of year.”

“Gideon,” Will said, clapping his hand on Gideon’s shoulder. “There is nothing wrong whatsoever with Thomas.”

Gideon sighed. “That’s very kind of you to say, Will, but—”

“But nothing. Thomas is just small. Sometimes children are small. He’s not cursed or hexed.”

“He gets sick,” Gideon pressed. “All the time.”

Will laughed. “Do you have any idea how sick Cecily was as an infant? She was colicky, and then she had fevers…she cried more than she slept, those first few years.”

“And then what?”

Will threw up his hands. “And then nothing! She grew! She fell ill less and less often. That is the way of children. And we did not have terrifying mute telepathic doctors to take care of us. Does Thomas eat? Does he exert himself when he does feel well?”

“Yes,” Gideon admitted.

“Well then,” said Will, leaning back as if his point was made. “Put your mind aside from your supposed cursed family. Tatiana’s son is sickly—does that surprise you, now you’ve seen the house? Now you’ve seen Tatiana? No, of course not.” He looked at Gideon intently. “Thomas’s only trouble,” he said firmly, “is that he is an adorable wee thing.”

Gideon stared at Will. Then he broke into laughter. Will laughed too, his usual hearty chuckle, and Gideon found himself feeling better. He was still worried about Thomas—he would be for a few years, he knew, until the boy had passed the time of worrisome childhood ailments and could be protected with runes—but he felt better nonetheless. He had thought of many ways he might feel on the way back from his sister’s house, but “better” had not been one of them.

“Christmas miracle,” Will whispered gleefully.

Well, thought Gideon. Some kind of miracle, anyway.

#the last hours#the shadowhunter chronicles#the infernal devices#chain of gold#will herondale#gideon lightwood#cassandra clare#tsc#tlh#tid

107 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tessa Gray as pictured by our lovely Cassandra Jean, drawn for the Clockwork Angel 10th Anniversary special edition! Here garnets represent Tessa’s birthstone. (The birthdays of the TID characters are all in the 10th Anniversary book!)

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

NOVEMBER’s Chain of Gold Flash Fiction by Cassandra Clare

A Lightwood Christmas Carol, Part 1

LONDON, 1889

Will Herondale was full of Christmas spirit, and Gideon Lightwood found it very annoying.

It wasn’t just Will, actually; he and his wife Tessa had both been raised in mundane circumstances until they were nearly adults, and so their memories of Christmas were of fond family memories and childhood delights. They came alive with it when the city of London did, as it did every year.

Gideon’s memories of Christmas were mostly about overcrowded streets, overrich food, and over-inebriated mundane carolers who needed to be saved from London’s more dangerous elements as they caroused all night, believing all trouble and wickedness was gone from the world right up until they were eaten by Kapre demons disguised as Christmas trees. Just for example.

Born and raised a Shadowhunter, Gideon, of course, did not celebrate Christmas, and had always borne London’s obsession with the holiday with bemused indifference. He had resided in Idris for most of his adult life, where the winter had a kind of Alpine profundity, and there was nary a Christmas wreath or cracker to be found. Winter in Idris felt more solemn than Christmas, so much older than Christmas. It was a strange facet of Idris: where most Shadowhunters ended up celebrating the holidays of their local mundanes, at least the ones that spilled out into street decorations and public festivals, Idris had no holidays at all. Gideon never wondered about this; it seemed obvious to him that Shadowhunters didn’t take days off. It was the blessing and the curse of being one, after all. You were a Shadowhunter all the time.

No wonder some couldn’t bear it, and left for a mundane life. Like Will Herondale’s father Edmund, in fact.

Perhaps that was why Will’s Christmas spirit annoyed him so. He’d come to like Will Herondale, and consider him a good friend. He hoped that when their children were older they too would become friends, if Thomas was all right by then. And he knew Will deliberately presented himself as silly and rather daft, but that he was a sharp and observant Institute head, and a more-than-capable fighter of demons.

But when Will insisted on taking them all to see the window displays at Selfridge’s, he could not help but worry that perhaps Will had a fundamentally unserious mind after all.

“Oxford Street? Days before Christmas? Are you mad?”

“It will be a lark!” Will said, with the slight lilt into his Welsh accent that meant he was a little too excited for his own good. “I’ll take James, you take Thomas, we’ll have a stroll. Have a drink at the Devil on the way back, what?” He clapped Gideon on the back.

It had been a long time since Gideon was last in England. As one of the Consul’s most trusted advisors, Gideon not only lived in Idris but rarely found opportunity to leave. He also remained so that his son Thomas could breathe the healthy air of Brocelind Forest, and not the air of this filthy, foggy city.

This filthy, foggy city, his father’s voice echoed in his mind, and Gideon was too weary to silence his father’s voice as he usually did whenever Benedict crept in. More than ten years dead, yet he had not shut up.

His brother Gabriel lived in Idris, too, and for less obvious reasons. Perhaps it was not only the bad air; perhaps they both were happier with a good distance between them and Benedict Lightwood’s house. And the knowledge that its current resident would barely speak with either of them.

But now Gideon had come to London, with Thomas, just the two of them, leaving Sophie and the girls behind. He needed advice about Thomas, people with whom he could discuss the problem discreetly. He needed to talk to Will and Tessa Herondale, and he needed to talk to a very specific Silent Brother who was often found in their vicinity.

Just now he was wondering if that had been a good idea. “A good bracing walk” was exactly the kind of English nonsense he’d half-expected Will to suggest for Thomas, but “a good bracing walk down the most crowded shopping street in London three days before Christmas” was a level of nonsense he had not been prepared for. “I can’t take Thomas through that crowd,” he said to Will. “He’ll get knocked around.”

“He isn’t going to get knocked around,” said Will scornfully. “He’ll be fine.”

“Besides,” said Gideon, “we’ll get looks. Mundane fathers don’t usually walk their babies in prams, you know.”

“I shall carry my son upon my shoulders,” said Will, “and you carry yours on yours, and Angel protect anyone who complains about it. Fresh London air would do all of us some good. And the windows are meant to be a spectacle, this year.”

“Fresh London air,” said Gideon dryly, “is thick as molasses and the color of pea soup.” But he acquiesced.

He had left Thomas in the nursery, where Tessa kept a watch over him and James. A full year older than James, Thomas wasn’t always good at understanding what James could and couldn’t do or understand. Tessa had been concerned that James would end up hurt. Gideon, though, was more concerned about Thomas, who was still smaller than James, despite the difference in their ages. He was paler than James, too, and less sturdy. He had only recently recovered from the latest of his terrible fevers, which had brought a Silent Brother, unfamiliar to them, to their house in Alicante to examine him. After a time the Silent Brother declared that Thomas would recover, and left without any further conversation.

But Gideon wanted answers. As he picked up Thomas now, he couldn’t help but think about how the boy was hardly any weight at all. He was the smallest of all “the boys,” as Gideon thought of them – of James, and his brother’s son Christopher, and Charlotte’s son Matthew. He had been born early, and small. They had been terrified the first time he caught fever, convinced it was the end.

Thomas hadn’t died, but he hadn’t fully recovered either. He remained delicate, weak of constitution, quick to illness. Sophie had fought harder than anyone to drink from the Mortal Cup and become a Shadowhunter, but now she was forced to fight a far worse battle against death by their son’s bedside. Over and over again.

Sighing, he took his son to fetch their coats for their bracing Christmas walk.

As expected, Oxford Street was a madhouse of pedestrian shoppers, carriages, gawkers, and menacing groups of roaming carolers. Gideon would just as soon have glamoured them all invisible from mundane eyes (although one of the groups of carolers were obviously werewolves, who had exchanged Acknowledging Looks with Gideon), but Will of course wished to bask in the experience.

James also seemed mostly intrigued by the noise and lights, giggling and yelping at the merry scene around them. A London boy from birth, thought Gideon, and then thought, well, but I was a London boy from birth, and this is too much commotion for my liking. For his own part, Thomas was quiet, watching with wide eyes, clutching onto his father’s shoulders. Gideon wasn’t sure how weakened Thomas still was from the last fever and how much he was overwhelmed by the crowds. In some ways, when he wasn’t sick, Thomas could be guilt-inducingly easy to care of; he rarely made a fuss, just looked out into the world with those large hazel eyes, as if aware of his own helplessness and hoping not to be noticed.

Will waited until after they had already joined the crowds at the windows of Selfridge’s and Will had made a number of nonsensical exclamations of delight of the “By Jove!” variety. He had held James right up to the glass to examine the scenes in detail, which seemed to revolve around some blond children ice skating on a river. Gideon had pointed things out to Thomas, who had smiled.

Only once they had stopped to purchase some hot cider from a man hawking it down a side street did Will say, “I heard about Tatiana’s son Jesse. Dreadful business. Have you spoken to her?”

Gideon shook his head. “I haven’t spoken to Tatiana in nearly ten years, or been back to the house.”

Will made a sympathetic noise.

“I don’t think it’s a coincidence,” said Gabriel.

“What?” Will said.

“A coincidence,” said Gabriel. “That both her and I have children who are—sickly.”

“Gideon,” said Will reasonably, “forgive me for saying so, but that is a load of codswallop.” Gideon blinked at him. “For one thing, you have your beautiful daughters, neither of whom were more than usually ill when they were babies. For another, all of what happened to your father was his own doing, and happened long after you were born, and neither you or Gabriel were sickly.”

Gideon shook his head. Will was so kind, so eager to spare him the consequences of his family’s sins. “You don’t know the extent of it,” he said. “The extent of Benedict’s experiments with dark magic. They were ongoing, from as long as I can remember. The demon pox just sticks in the memory, because it is rather lurid.”

“And also we were there,” said Will, “when he turned into a giant worm.”

“Also that,” said Gideon grimly. “But two sickly sons, small and frail—I cannot say with certainty that it is a coincidence, that it has nothing to do with the depredations of my father. I cannot risk the possibility.” He looked at Will imploringly. “It took Jesse years to become ill,” he said, “and Thomas has been ill so much already.”

There was a profound silence. Quietly, Will said, “You sound as if you mean to do something.”

“I do,” said Gideon with a sigh. “I must look at my father’s papers, his records of what he called his “work”. They are at Chiswick, and I must go and ask Tatiana for them.”

“Will she see you?” said Will.

Gideon shook his head again. “I don’t know. I hoped her anger would cool, over time, and her resentment. I hoped the fact that the Clave gifted her with all my father’s wealth and possessions would help her find peace.”

“Well,” said Will, “if you go, you absolutely must leave Thomas with us.”

“You wouldn’t want him to meet his aunt?” Gideon said innocently.

Will looked at him seriously. “I wouldn’t want him, or any of my children, on the grounds of that house!”

Gideon was taken aback. “Why? What’s she done to it?”

Will said darkly, “It’s what she hasn’t done.”

Gideon could see Will’s point. Tatiana hadn’t done anything to the house. Nothing to change, or clean, or preserve it in any way. Rather than restoring it or redecorating it to her own tastes, Tatiana had simply allowed it to rot, blackening and collapsing in on itself, a ghastly monument to Benedict Lightwood’s ruination. The windows were clouded, as though fog were seething indoors; the maze, a black and twisted wreckage. When he opened the front gate, the hinges screamed like a tortured soul.

It did not bode well for the emotional state of its resident.

When Benedict Lightwood died in disgrace from the late stages of demon pox, and the full history of his infamy was revealed to the Clave, Gideon laid low. He didn’t want to answer questions, or hear false sympathy for the damage done to his family name. He shouldn’t have cared. He’d known the truth of his father already. Yet it stung his pride, when he shouldn’t have had any pride left in his besmirched name.

The houses and the fortune were taken away from Benedict’s children by order of the Clave. Gideon could still remember when he had found out that Tatiana had brought a complaint against him and against Gabriel for the “murder” of their father. The Clave had first confiscated their possessions, and finally laid out the situation: Tatiana Blackthorn had petitioned the Clave for Benedict’s fortune to be given to her, as well as the Lightwood’s ancestral house in Chiswick. She was a Blackthorn now, not the bearer of a tainted name. She made many accusations against her brothers in the process. The Clave said they understood that Gideon and Gabriel had had no choice but to slay the monster their father had become, yet if they were to speak of technical truth only, Tatiana might be considered correct. The Clave was inclined to give Tatiana the full Lightwood inheritance, in hopes of settling the matter.

“I will fight this,” Charlotte had told Gideon, her small hands tight upon his sleeve and her mouth set.

“Charlotte, don’t,” Gideon begged. “You have so many other battles to fight. Gabriel and I don’t need any of that tainted money. This doesn’t matter.”

The money hadn’t mattered, then.

Gabriel and Gideon discussed the matter, and decided not to contest her claims. Their sister was a widow. She could live in the former Lightwood manor at Chiswick in England, and at Blackthorn Manor in Idris, and welcome. Gideon hoped she and her son would be happy. As it was, Gideon’s memories of the house were, at best, ambivalent.

Now he waited at the front door, its paint mostly peeled off, with deep gouges here and there, as though some wild animal had tried to get in. Maybe Tatiana locked herself out at some point. After a time it swung open, but waiting behind it was not his sister but a ten year old boy, looking somber. He had the midnight black hair of the father he’d never met, but he was tall for his age, willow-thin, with green eyes.

Gideon blinked. “You must be Jesse.”

The boy narrowed his eyes. “Yes,” said the boy. “Jesse Blackthorn. Who are you?”

Jesse, his nephew, after all this time. Gideon had asked so many times to see Jesse when he was a child. He and Gabriel had tried to go to Tatiana when she had the child, but she turned them both away.

Gideon took a deep breath. “Well,” he said. “I’m your Uncle Gideon, as it happens. I am very glad to make your acquaintance at last.” He smiled. “I was always hoping for it.”

Jesse’s expression did not improve. “Mama says you are a very wicked man.”

“Your mother and I,” Gideon said with a sigh, “have had a very…complicated history. But family should know one another, and fellow Shadowhunters, as well.”

The boy continued to stare at Gideon, but his face softened a bit. “I have never met any other Shadowhunters,” he said. “Other than Mama.”

Gideon had thought about this moment many times, but now found himself struggling for words. “You are…you see…I wanted to tell you. We have heard that your mother doesn’t want you to take Marks. You should know…we are family first, always. And if you don’t wish to take Marks, the rest of your family will support you in that decision. With the—the other Shadowhunters.” He wasn’t sure if Jesse even knew the word Clave.

Jesse looked alarmed. “No! I will. I want to! I’m a Shadowhunter.”

“So is your mother,” murmured Gideon. He felt a slight twinge of possibility there. Tatiana could have disappeared like Edmund Herondale, abandoned Downworld entirely, lived as a mundane. Shadowhunters did, sometimes; though Edmund had done it for love, Tatiana might do it out of hatred. That she had not gave Gideon hope, although, he was sure, foolish hope.

He knelt down, to be closer to the boy. He hesitated, then reached out for Jesse’s shoulder. Jesse stepped back, casually avoiding the touch, and Gideon let it go. “You are one of us,” he said quietly.

“Jesse!” Tatiana’s voice came from the top of the entrance stairs. “Get away from that man!”

As if prodded with a needle, Jesse leapt away from Gideon’s reach and retreated without a further word into the shadowed recesses of the house.

Gideon stared in horror as his sister Tatiana drifted down the stairs. She wore a pink gown more than ten years old. It was stained with blood he well knew was more than ten years old as well. Her face was drawn and pinched, as though her scowl had been etched there, unchanged for years.

Oh, Tatiana. Gideon was flooded with a strange amalgamation of sympathy and revulsion. This is long past grief. This is madness.

His little sister’s green eyes rested on him, cold as if he were a stranger. Her smile was a knife.

“As you can see, Gideon,” she said. “I dress for company. You never know who might drop by.”

Her voice, too, was changed: rough and creaking with disuse.

“Have you come to apologize?” Tatiana went on. “You will not find exoneration, for the things you have done. Their blood is on your hands. My father. My husband. Your hands, and your brother’s hands.”

And how was that? Gideon wanted to ask her. He had not killed her husband. Their father had done that, transformed by disease into a dreadful demonic creature.

But Gideon felt the shame and the guilt, as well as the grief, as he knew she intended him to. He had been the first to cut ties with his father, and with his father’s legacy. Benedict had taught them all to stick together, no matter what the cost, and Gideon had walked away. His brother had stayed, until he saw proof of their father’s corruption he couldn’t deny.

His sister remained even now.

“I am sorry you blame us,” said Gideon. “Gabriel and I have only ever wished for your good. Have you—have you read our letters?”

“I never was fond of reading,” murmured Tatiana.

She inclined her head, and after a moment Gideon realized this was the closest she would get to inviting him in. He stepped across the threshold nervously and, when Tatiana did not immediately shout at him, he continued inside.

Tatiana led him to what had once been their father’s office, a sculpture in dust and rot. He averted his eyes from the torn wallpaper, catching a glimpse of writing on the wall that read WITHOUT PITY.

“Thank you for seeing me,” Gideon said as he took a seat across the desk from her. “How is Jesse?”

“He is very delicate,” said Tatiana. “Nephilim like yourself wish to put Marks on him, because they are intent on killing my boy as they have killed everyone else I love. You sit on the Council, do you not? Then you are his enemy. You may not see him.”

“I would not force Marks on the boy,” protested Gideon. “He’s my nephew. Tatiana, if he is that ill, perhaps he should see the Silent Brothers? One of them is a close friend, and could come to Jesse at our house. And Jesse could know his cousins.”

“Mind your own house, Gideon,” Tatiana snapped. “Nobody expects your son to live to Jesse’s age, do they?”

Gideon fell silent.

“I expect you want Jesse to marry one of your penniless daughters,” Tatiana went on.

Now Gideon was more confused than offended. “His first cousins? Tatiana, they are all very young children—”

“Father planned alliances for us, when we were children.” Tatiana shrugged. “How ashamed he would be of you. How is your grubby servant?”

Gideon would have struck any man who spoke of Sophie so. He felt the rage and violence he’d known as a child storm within him, but he’d desperately taught himself control. He exercised every bit of that control now. This was for Thomas.

“My wife Sophia is very well.”

His sister nodded, almost pleasantly, but the smile quickly became a grimace. “Enough pleasantries, then. You came to Chiswick for a reason, did you not? Out with it. I know what it is already. Your son is like to die, and you want money for filthy Downworlder remedies. You’re here as a beggar, cap in hand. So beg me.”

It was strange: Tatiana’s obvious, undeniable insanity made her insults and imprecations undeniably easier to bear. What was she even saying? What Downworlder remedies? How could remedies be filthy?

Had Benedict destroyed Tatiana as well? Or would she always have been like this? Their mother had killed herself because their father passed on a demon’s disease to her. Their father had died of the same sickness, in disgrace and horror. Will Herondale could dismiss it all as nonsense, but could it be a coincidence that Tatiana’s son, and his son, were both sickly? Or was it some weakness in their very blood, some punishment from the Angel who had seen what the Lightwoods truly were and passed his judgment upon them?

“I need no money,” Gideon said. “As you well know, the Silent Brothers are the best of doctors, and their services are always freely available to me. As they are to you,” he added with emphasis.

“What, then?” Tatiana said. Her head cocked slightly.

“Father’s papers,” Gideon said in a rush of expelled breath. “His journals. I think that the cause of my son’s illness might be found there.” He found he didn’t want to say Thomas’s name in front of his sister, as though she might decide to conjure with it.

“A man you betrayed?” Tatiana spat. “You have no right to them.”

Gideon bowed his head to his sister. He had been prepared for this. “I know,” he lied. “I agree. But I need them, for the sake of my child. You have Jesse. Whatever our differences, you must understand that we could both love our children, at least. You must help me, Tatiana. I beg you.”

He’d thought Tatiana would smile, or laugh cruelly, but she only gazed at him with the impassive, mindless stare of a dangerous snake.

“And what will you do for me?” she said. “If I do help?”

Gideon could guess. Get the Clave to leave her alone, to let her do as she wished with Jesse, for one thing. But in Tatiana’s madness, who knew what she would come up with.

“Anything,” he said hoarsely.

He lifted his head and looked at her, at his mother’s green eyes in his sister’s pitiless face. Tatiana, who would always break her toys rather than share them. There was something missing in her, as there had been in their father.

Now she did smile. “I have just the task in mind,” she said.

Gideon braced himself.

“On the other side of the road from this estate,” Tatiana said, “is a mundane merchant. This man has a dog, of an unusual size and vicious temperament. Quite often he lets the dog run free in the neighborhood, and of course he comes straight here to make mischief.”

There was a long pause. Gideon blinked. “The dog?”

“He is always making trouble on my property,” Tatiana snarled. “Digging up my garden. Killing the songbirds.”

Gideon was utterly positively sure that Tatiana did not keep a garden. He had seen the state of the grounds on his way in, left to crumble as a monument to disaster no less than the house itself.

There were definitely no songbirds.

“He’s made a disaster of the greenhouse,” she went on. “He knocks over fruit trees, he throws rocks through windows.”

“The dog,” Gideon said again, to clarify.

Tatiana fixed her piercing gaze on him. “Kill the dog,” she said. “Bring me the proof you have done this, and you will have your papers.”

There was a very long silence.

Gideon said, “What?”

#the last hours#the shadowhunter chronicles#chain of gold#the infernal devices#tsc#tlh#tid#cassandra clare#will herondale#gideon lightwood#tessa gray

255 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thomas Lightwood by Charlie Bowater

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

OCTOBER’s Chain of Gold Flash Fiction by Cassandra Clare

Lucie and Ghosts

LONDON, 1897

“There are many kinds of ghosts,” Jessamine said, “but they tend to fall into three categories. You have mostly known ghosts like me, who are kind and beautiful and have wonderful personalities.”

Lucie almost snorted, but luckily Jessamine didn’t seem to notice. They were in the courtyard of the Institute, where Lucie was playing, and avoiding her family. Woolsey Scott was coming over for tea, and they were busy straightening up and putting away the silver — like all werewolves, he was allergic. Lucie didn’t mind Woolsey Scott, except that like most of the adults who visited the Institute he was tremendously boring, and also when he looked at her she felt that he was judging her for her untidiness and her ink-stained fingers. She had snuck off to play in the garden, and when nobody had come to fetch her, she decided she was safe.

Perhaps they assumed the coming rain would drive her back inside. The sky was thick with leaden clouds, and while the rain held off for now, the air contained that particular scent that meant it was inevitable.

She had made up a game to go with a story she had been composing recently. It was about a well-brought up young girl who was forced to become a pirate queen to save her kidnapped parents, and discovered she had quite a knack for it. She ran around the garden, weaving between bushes, imagining the she was a pirate queen whose sailors had whipped up a mutiny. The key was to look deeply distressed, extremely tragic, then spin around fast, stabbing out with the stick she was using as a sword.

She had stopped to decide whether the pirate queen should sport a silver mask or a black one when Jessamine, the Institute’s resident ghost, came floating down from an upper window like a torn page falling in a breeze. Lucie had known Jessamine her whole life, and understood that Jessamine had been friends with her parents when she was alive, though none of them had ever told her the full story. Lucie thought of Jessamine mostly as part of the furniture, a drifting presence that seemed content to wander through the halls of the Institute and occasionally criticize the place’s new modern décor and Lucie’s father’s choice of clothes.

“Hullo, Jessamine,” Lucie said now. She was disappointed; she had been enjoying her game. She hoped she would remember all the details of the pirate queen and the mutiny so she could write them down when she was back inside.

“Lucie,” Jessamine said, “I think it is time to speak with you about ghosts.”

“Now?” said Lucie in dismay.

Jessamine looked up at the sky. “It is the right weather for ghosts,” she said. “Now, listen.

“Some ghosts stay among the living because unfinished business holds them here. Some stay to protect those they love. And some stay because of hatred, malice, bitterness.” She ruffled Lucie’s hair; it felt like being brushed by a breeze. “You must learn to ignore that kind of ghost. Turn away from them. They feed off your fear. Without your fear they can do nothing to you.”

“I’ll remember,” Lucie murmured.

Jessamine cocked her head at Lucie. “Mind that you do,” she said, and vanished as suddenly as she’d appeared.

Lucie assumed that Jessamine had become a ghost in order to protect those she loved, but she was very strange regardless. A little more doubtful, she returned to her game. In the distance was a noise that might have been thunder or might have just been the bustle of London.

Her game took her out of the Institute’s courtyard and down the road a bit. The street was almost empty, but at one point Lucie whirled around to confront the boatswain who had pretended loyalty to her, while actually working for the mutinous first mate, and almost stabbed an actual person. She gasped, and took a step back. “I’m so sorry!” she cried. “I didn’t know you were there.”

The woman who stood before her wore a dark gray Victorian dress that gave her the look of an old-fashioned schoolteacher. In her gloved hand was a battered black valise. Her face was thin and pale and peaked, her hair straggling.

Lucie waited awkwardly, uncertain what to say. She should have remained on the Institute’s grounds, where glamour would have ensured no unexpected encounters with mundane humans. The woman considered her, and Lucie wondered if perhaps she wasn’t a mundane after all. But she had no runes, so she wasn’t a Shadowhunter. Could she be a Downworlder? She showed no outward signs of being a faerie or warlock or werewolf, and though she was pale, she was out in daylight, so she couldn’t be a vampire.

“I must ask something of you, little girl.” The woman’s voice was rough, as though she hadn’t spoken in a long time. “Are your parents looking for a governess? I am an excellent governess.”

She held out a paper—her credentials, perhaps, but Lucie’s attention was arrested by the woman’s hand.

It was no longer gloved. Now it was skeletal, the bone white as snow. Dark red blood was dripping from the ends of her fingers, soaking into the paper.

Lucie took a step back, breath catching in her throat. “You’re a ghost,” she said, almost without meaning to. But a ghost had never walked up to her on the street like this, certainly not one with skeletal hands. She looked back up at the ghost’s face. It was gaunt, slightly distorted, and it frightened her. “You can’t trick me,” Lucie said, trying to sound brave. “I can see you for what you are.”

“What a clever little girl,” The ghost’s raspy voice took on an unpleasant tone. “I don’t like clever little girls. I used to look after six of them. They played tricks on me and taunted me. One night I went up to their room and stabbed them, one at a time, all through their clever little hearts.”

Lucie’s blood ran cold. The ghost reached out, as if it were going to touch Lucie’s own heart, and she turned and ran full tilt in the direction of her home. She remembered what Jessamine had said, but how could she not be afraid? She could feel the presence of the ghost behind her, a prickling at the back of her neck. Lucie had just reached the gate when she stumbled over a loose stone and fell, scraping her knee on the path.

The ghost glided forward, reaching as though to help her up. “You could be my new pupil….”

Lucie scrambled away. “Stop! Get back!”

To her surprise, the ghost sprang away, looking startled. Perhaps little girls didn’t ordinarily yell at it. Lucie was about to scream for help, but help had already arrived.

Jessamine descended from the sky and stood between Lucie and the woman. But this was Jessamine as Lucie had never seen her: an avenging angel, looming above both Lucie and the ghost-woman, icy fury on her face. Lucie gasped in shock as Jessamine raised her hands, as if she were about to perform some terrifying incantation.

“No,” the ghost-woman moaned, her mouth yawning open horribly, showing a cavern of blackness. “I did not know this one was guarded. I did not know….”

“You will flee from here,” Jessamine commanded, and even her voice was different, deep and wild, like the crashing of waves. “You will leave this place, foul spirit!”

The ghost cowered for a moment, then vanished into nothingness.

Lucie lay on the garden path, staring up at Jessamine, who had shrunk down to her usual size. “Stop gaping, Lucie, it’ll give you wrinkles. Come on, up with you.” She had returned to her normal mien, pretty and dignified and distant.

“Thank you,” said Lucie faintly.

“Mind how you go,” Jessamine said sternly. “And heed what I’ve told you. There is more than one kind of ghost.” And she drifted up again and vanished.

The lesson stayed with Lucie for a long time. She never blamed Jessamine for not knowing there was a fourth kind of spirit. Even if Jessamine had known, she could not have prepared Lucie for the fact that meeting him would change her life forever.

#the last hours#the infernal devices#chain of gold#the shadowhunter chronicles#lucie herondale#jessamine lovelace#cassandra clare#tid#tlh#tsc

333 notes

·

View notes