Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Link

0 notes

Text

Hy Brasil - The Mythical Island off the Coast of Ireland

https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history/hy-brasil

Hy-Brasil is referenced in both explorers' logs and Celtic mythology

Imagination merges with reality where the island of Hy-Brasil is remembered in both travelers’ records and ancient Irish legends. Ireland could, indeed, have its own version of Atlantis.

Read More: Spookiest ancient Irish myths and legends surrounding Halloween

Information gathered by historian Fiona Broome, as well as Celtic mythological enthusiasts, shows the intersection of myth and reality in regards to the island of Hy-Brasil, which is also known by the variants Hy-Breasal, Hy-Brazil, Hy-Breasil, Brazir, among others.

In Celtic folklore, this island country takes its name from Breasal, the High King of the World. However, as the Atlantic began to be more thoroughly explored, the name of Hy Brazil may have been attached to a real place, providing some evidence that attached itself to the Irish myth.

Hy-Brasil was noted on maps as early as 1325 when Genoese cartographer Dalorto placed the island west of Ireland. On successive sailing charts, it appears southwest of Galway Bay.

Both Saint Barrind and Saint Brendan found the island on their respective voyages, and returned home with nearly identical descriptions of Hy-Brasil, which they dubbed the “Promised Land.”

A Catalan map of about 1480 labels an island as “Illa de brasil” to the south-west of Ireland, where the mythical place was supposed to be.

Expeditions left Bristol in 1480 and 1481 to search for it, and a letter written shortly after the return of John Cabot from his expedition in 1497 reports that land found by Cabot had been “discovered in the past by the men from Bristol who found Hy Brasil.”

Some historians claim that the navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral thought that he had reached this island in 1500, thus naming the country of Brazil. However, Cabral didn’t choose the name ‘Brazil’. The country was at first named Ilha de Vera Cruz (Island of the True Cross), later Terra de Santa Cruz (Land of the Holy Cross) and still later ‘Brazil’.

Read More: The Headless Horseman and other monsters from the Celtic underworld

The generally accepted theory states that it was renamed for the brazilwood, which has an extreme red color (so “brasil” derivated from “brasa”: ember), a plant very valuable in Portuguese commerce and abundant in the new-found land.

The most distinctive geographical feature of Hy-Brasil, is that it appears on maps as a perfect circle, with a semi-circular channel through the center. The central image on the Brazilian flag, a circle with a channel across the center, was the symbol for Hy-Brasil on early maps.

The circular perimeter of the island was confirmed by both Saints Barrind and Brendan, who separately walked the shore to determine where the island ended, but never found it. Most likely, they were walking in circles.

One of the most famous visits to Hy-Brasil was in 1674 by Captain John Nisbet of Killybegs, Co. Donegal, Ireland. He and his crew were in familiar waters west of Ireland, when a fog came up.

As the fog lifted, the ship was dangerously close to rocks. While getting their bearings, the ship anchored in three fathoms of water, and four crew members rowed ashore to visit Hy-Brasil. They spent a day on the island and returned with silver and gold that was given to them by an old man who lived there.

Read More: Myth-busting the popular 'castle island' in Ireland as a fake

The last supposed sighting was in 1872 by Roderick O’Flaherty. In ‘A Chorographical Description of West or H-Iar Connaught (1684),’ he tells us of the reported “old man” by saying:

“There is now living, Morogh O’Ley, who immagins he was himself personally on O’Brasil for two days, and saw out of it the iles of Aran, Golamhead, Irrosbeghill, and other places of the west continent he was acquainted with.”

The last documented sighting of Hy-Brasil was in 1872 when author T. J. Westropp and several companions saw the island appear and then vanish. This was Mr. Westropp’s third view of Hy-Brasil, but on this voyage, he had brought his mother and some friends to verify the Island’s existence.

Whether or not the island exists - or ever existed - is still hard to tell, but the mythical and real accounts of the Island are hard to deny.

What do you think about Hy-Brasil? Let us know in the comments section below.

*Originally published in 2016

0 notes

Quote

คืออย่างมนุษย์เงี้ย โดนแรงดึงดูดดึงให้ติดกับพื้นดิน แต่พอเราอยู่ในน้ำ เราก็ลอย เหมือนทุกอย่างมาเจอกันที่ผิวน้ำป้ะ พอปลาตายปลาก็ลอยมาบนผิวน้ำ คนตายคนก็แก้แรงโน้มถ่วง ลบบนบก

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Analysing Evidence

Before I start, this Australian guy, called Paul… something, is researching the history on Japan and has some pretty good information on Kimura’s findings. He was personally shown by Kihachiro Aratake (founder of Iseki Point / Yonaguni Monument while diving for hammerheads) and Masaaki Kimura.

http://pperov.angelfire.com/Shinto.htm#yonaguni

Now to Kimura’s evidence:

1. “Traces of marks that show that human beings worked the stone. There are holes made by wedge-like tools called kusabi in many locations.”

6. “Stone tablets with carving that appears to be letters or symbols, such as what we know as the plus mark ‘+’ and a ‘V’ shape were retrieved from under water.”

Personally taken by Kimura himself, there are several lines seemingly carved on a rock in a pattern which is unlikely to be of natural formation. Looking at this, we can see some resemblance to the glyphs on the “Okinawa Rosetta Stone”. I find the second photograph corresponds to the glyph on the top left corner of the stone.

2. “Around the outside of the loop road [a stone-paved pathway connecting principal areas of the main monument] there is a row of neatly-stacked rocks as a stone wall, each rock about twice the size of a person, in a straight line.”

From the diagram, I would assume Kimura is referring to the five even shaped rocks above the 20m label, continuing along the loop road from the staircases. I think it’s a bit of a stretch to call it a stone wall though. The rocks littering the bottom left of the diagram do not seem to match the description of lined up, even shaped stones. Although they may have resembled a stone wall if/when above land.

3. “There are traces carved along the roadway that humans conducted some form of repairs.”

Just saying, I’m not sure how Kimura proved this, or what evidence he suggested. I currently can’t find any… But then again, I don’t have access to his resources.

5. “Stone tools are among the artifacts found underwater and on land.”

7. “From the waters nearby, stone tools have been retrieved. Two are for known purposes that we can recognize, the majority are not.”

Kimura has evidently found stone tools lying here and there around the Ryukyu Islands. One he mentions previously is the kasubi, which is a wedge-like tool constructed from stone.

4. “The structure is continuous from under the water to land, and evidence of the use of fire is present.”

I don’t know if I can prove if there has been use of fire on the monument, but the Yonaguni Monument is one of many similar submerged structures around the Ryukyu Islands.

From Robert Schoch’s website:

However, if I simply state that the Yonaguni Monument is natural, I leave out part of the story. On the island is evidence of very ancient human habitation, including tombs and other structures artificially carved from the bedrock (see the accompanying photo) that I am convinced mimic, and were stylistically inspired by, the natural features of the island, including the step-like features now submerged by the ocean.

8. “At the bottom of the sea, a relief carving of an animal figure was discovered on a huge stone.” (1) 9. On the higher surfaces of the structure there are several areas which slope quite steeply down towards the south. Kimura points out that deep symmetrical trenches appear on the northern elevations of these areas which could not have been formed by any known natural process. 10.�� A series of steps rises at regular intervals up the south face of the monument from the pathway at its base, 27 meters underwater, towards its summit less than 6 meters below the waves. A similar stairway is found on the monument’s northern face. 11. Blocks that must necessarily have been removed (whether by natural or by human agency) in order to form the monument’s impressive terraces are not found lying in the places where they would have fallen if only gravity and natural forces were operating; instead they seem to have been artificially cleared away to one side and in some cases are absent from the site entirely. 12. The effects of this unnatural and selective clean-up operation are particularly evident on the rock-cut ‘pathway’ [Kimura calls it the ‘loop road’] that winds around the western and southern faces of the base of the monument. It passes directly beneath the main terraces yet is completely clear of the mass of rubble that would have had to be removed (whether by natural or by human agency) in order for the terraces to form at all.(2)

Honestly, I’m not a geologist and I don’t have much information to prove otherwise. I am a bit skeptical about the relief carving of the animal because there is subjectivity in Kimura’s judgement. What Kimura describes as the turtle rock, in my opinion does not resemble a turtle at all. Although I must say, the star-like shape of it is intriguing. I do believe that it must have been terraformed by humans. I don’t believe forces of nature could create such a shape due to erosion and “breaking off on faultlines” - as is the common argument - alone.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

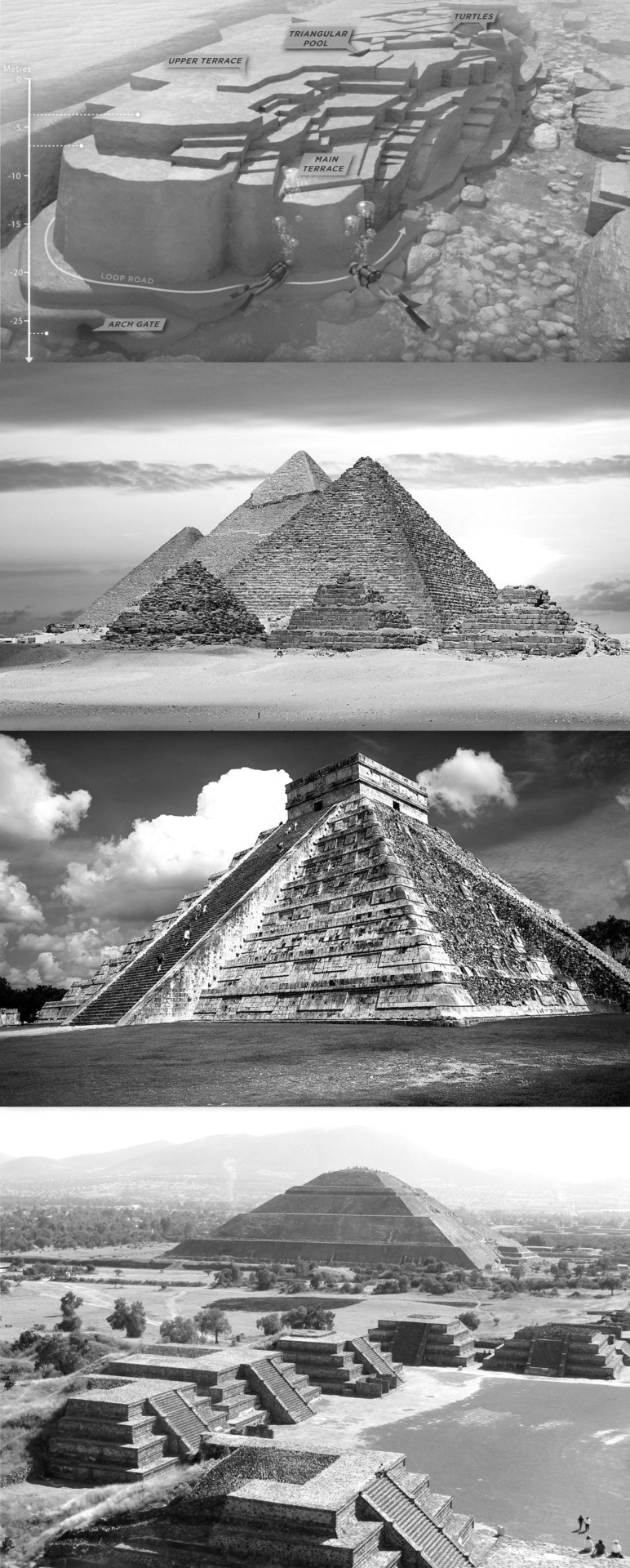

Yonaguni - Pyramids of Giza - Chichén Itzá - Teotihuacan

65 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Photo

Natural structures so angular and precise that they seem to be built by ancient human hands.

1. Yonaguni Monument: Massive underwater rock formation off the coast of Japan - complete with stairs, platforms, and altars.

2. Giant’s Causeway: Eerily geometric, interlocking remnants of a pre-historic volcano, Northern Ireland

3. Old Rag Mountain: Exposed granite staircase and curiously erratic boulders, Shenandoah National Park, Virginia, USA

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Okinawan Language

Anybody who has studied Japanese and Linguistics will know that Japanese is a part of the Japonic language family. For many years it was thought that Japanese was a language isolate, unrelated to any other language (Although there is some debate as to whether or not Japanese and Korean are related). Today, most linguists are in agreement that Japanese is not an isolate. The Japonic languages are split into two groups: Japanese (日本語) and its dialects, which range from standard Eastern Japanese (東日本方言) to the various dialects found on Kyūshū (九州日本方言), which are, different, to say the least. The Ryukyuan Languages (琉球語派). Which are further subdivided into Northern and Southern Ryukyuan languages. Okinawan is classified as a Northern Ryukyuan Languages. There are a total of 6 Ryukyuan languages, each with its own dialects. The Ryukyuan languages exist on a continuum, somebody who speaks Okinawan will have a more difficult time understanding the Yonaguni Language, which is spoken on Japan’s southernmost populated island. Japanese and Okinawan (I am using the Naha dialect of Okinawan because it was the standard language of the Ryukyu Kingdom), are not intelligible. Calling Okinawan a dialect of Japanese is akin to calling Dutch a dialect of English. It is demonstrably false. Furthermore, there is an actual Okinawan dialect of Japanese, which borrows elements from the Okinawan language and infuses it with Japanese. So, where did the Ryukyuan languages come from? This is a question that goes hand in hand with theories about where Ryukyuan people come from. George Kerr, author of Okinawan: The History of an Island People (An old book, but necessary read if you’re interested in Okinawa), theorised that Ryukyuans and Japanese split from the same population, with one group going east to Japan from Korea, whilst the other traveled south to the Ryukyu Islands. “In the language of the Okinawan country people today the north is referred to as nishi, which Iha Fuyu (An Okinawn scholar) derives from inishi (’the past’ or ‘behind’), whereas the Japanese speak of the west as nishi. Iha suggests that in both instances there is preserved an immemorial sense of the direction from which migration took place into the sea islands.” (For those curious, the Okinawan word for ‘west’ is いり [iri]). But, it must be stated that there are multiple theories as to where Ryukyuan and Japanese people came from, some say South-East Asia, some say North Asia, via Korea, some say that it is a mixture of the two. However, this post is solely about language, and whilst the relation between nishi in both languages is intriguing, it is hardly conclusive. With that said, the notion that Proto-Japonic was spoken by migrants from southern Korea is somewhat supported by a number of toponyms that may be of Gaya origin (Or of earlier, unattested origins). However, it also must be said, that such links were used to justify Japanese imperialism in Korea. Yeah, when it comes to Japan and Korea, and their origins, it’s a minefield. What we do know is that a Proto-Japonic language was spoken around Kyūshū, and that it gradually spread throughout Japan and the Ryukyu Islands. The question of when this happened is debatable. Some scholars say between the 2nd and 6th century, others say between the 8th and 9th centuries. The crucial issue here, is the period in which proto-Ryukyuan separated from mainland Japanese. “The crucial issue here is that the period during which the proto-Ryukyuan separated(in terms of historical linguistics) from other Japonic languages do not necessarily coincide with the period during which the proto-Ryukyuan speakers actually settled on the Ryūkyū Islands.That is, it is possible that the proto-Ryukyuan was spoken on south Kyūshū for some time and the proto-Ryukyuan speakers then moved southward to arrive eventually in the Ryūkyū Islands.” This is a theory supported by Iha Fuyu who claimed that the first settlers on Amami were fishermen from Kyūshū. This opens up two possibilities, the first is that ‘Proto-Ryukyuan’ split from ‘Proto-Japonic’, the other is that it split from ‘Old-Japanese’. As we’ll see further, Okinawan actually shares many features with Old Japanese, although these features may have existed before Old-Japanese was spoken. So, what does Okinawan look like? Well, to speakers of Japanese it is recognisable in a few ways. The sentence structure is essentially the same, with a focus on particles, pitch accent, and a subject-object-verb word order. Like Old Japanese, there is a distinction between the terminal form ( 終止形 ) and the attributive form ( 連体形 ). Okinawan also maintains the nominative function of nu ぬ (Japanese: no の). It also retains the sounds ‘wi’ ‘we’ and ‘wo’, which don’t exist in Japanese anymore. Other sounds that don’t exist in Japanese include ‘fa’ ‘fe’ ‘fi’ ‘tu’ and ‘ti’. Some very basic words include: はいさい (Hello, still used in Okinawan Japanese) にふぇーでーびる (Thank you) うちなー (Okinawa) 沖縄口 (Uchinaa-guchi is the word for Okinawan) めんそーれー (Welcome) やまとぅ (Japan, a cognate of やまと, the poetic name for ‘Japan’) Lots of Okinawan can be translated into Japanese word for word. For example, a simple sentence, “Let’s go by bus” バスで行こう (I know, I’m being a little informal haha!) バスっし行ちゃびら (Basu sshi ichabira). As you can see, both sentences are structured the same way. Both have the same loanword for ‘bus’, and both have a particle used to indicate the means by which something is achieved, ‘で’ in Japanese, is ‘っし’ in Okinawan. Another example sentence, “My Japanese isn’t as good as his” 彼より日本語が上手ではない (Kare yori nihon-go ga jouzu dewanai). 彼やか大和口ぬ上手やあらん (Ari yaka yamatu-guchi nu jooji yaaran). Again, they are structured the same way (One important thing to remember about Okinawan romanisation is that long vowels are represented with ‘oo’ ‘aa’ etc. ‘oo’ is pronounced the same as ‘ou’). Of course, this doesn’t work all of the time, if you want to say, “I wrote the letter in Okinawan” 沖縄語で手紙を書いた (Okinawa-go de tegami wo kaita). 沖縄口さーに手紙書ちゃん (Uchinaa-guchi saani tigami kachan). For one, さーに is an alternate version of っし, but, that isn’t the only thing. Okinawan doesn’t have a direct object particle (を in Japanese). In older literary works it was ゆ, but it no longer used in casual speech. Introducing yourself in Okinawan is interesting for a few reasons as well. Let’s say you were introducing yourself to a group. In Japanese you’d say みんなさこんにちは私はフィリクスです (Minna-san konnichiwa watashi ha Felixdesu) ぐすよー我んねーフィリクスでぃいちょいびーん (Gusuyoo wan’nee Felix di ichoibiin). Okinawan has a single word for saying ‘hello’ to a group. It also showcases the topic marker for names and other proper nouns. In Japanese there is only 1, は but Okinawan has 5! や, あー, えー, おー, のー! So, how do you know which to use? Well, there is a rule, typically the particle fuses with short vowels, a → aa, i → ee, u → oo, e → ee, o → oo, n → noo. Of course, the Okinawan pronoun 我ん, is a terrible example, because it is irregular, becoming 我んねー instead of 我んのー or 我んや. Yes. Like Japanese, there are numerous irregularities to pull your hair out over! I hope that this has been interesting for those who have bothered to go through the entire thing. It is important to discuss these languages because most Ryukyuan languages are either ‘definitely’ or ‘critically’ endangered. Mostly due to Japanese assimilation policies from the Meiji period onward, and World War 2. The people of Okinawa are a separate ethnic group, with their own culture, history, poems, songs, dances and languages. It would be a shame to lose something that helps to define a group of people like language does. I may or may not look in the Kyūshū dialects of Japanese next time. I’unno, I just find them interesting.

3K notes

·

View notes