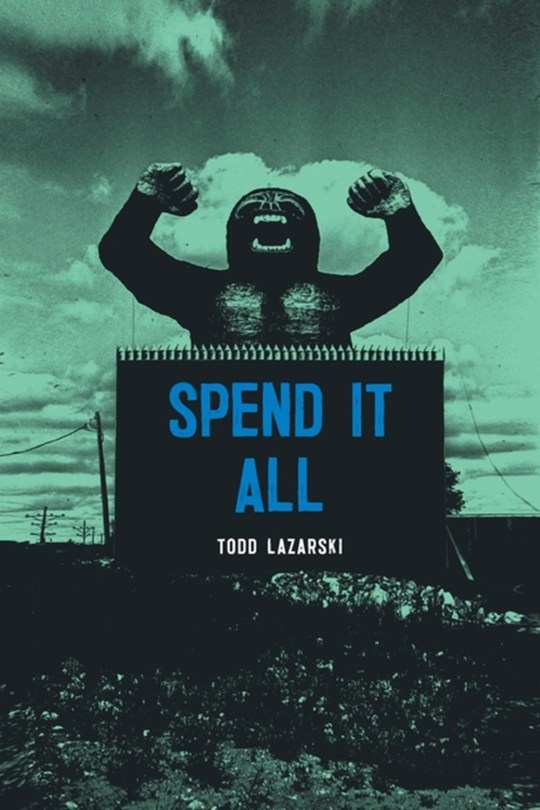

Todd Lazarski is a freelance writer. He contributes regularly to The A.V. Club, Eater, and The Shepherd Express. His work has also appeared in Paste, TimeOut, and Offbeat New Orleans.   He is the author of two novels out on Red Giant Books: MAKE THE ROAD BY WALKING ('16) and SPEND IT ALL ('20). Contact via email

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Hawthorne Coffee Branches Out

Shepherd Express

Lunch at a coffee shop can be an uninspiring prospect. Something slapped together last Tuesday, a gummy muffin, maybe some soup — it is so often a step down from a greasy spoon, barely a step up from going hungry, giving notions of a utilitarian meal and a quick-mawing of carbs in order to hurry back to getting stuff done. Stepping into Hawthorne may not lead to different ideas. There is a counter case of cookies and hand pies, a cooler softly beckoning with premade sandwiches — ham and cheese, chicken salad, English muffin or bagel breakfast concoctions. But then you might end up there hungry, around noon, say sometime between Wednesday and Sunday. And you may give in to a knowing and cooly confident nod of secretive advice from the barista, and your low expectations could well be socked with a shaved prime rib and half-melted provolone, with sauteed peppers and spurting roasted garlic mayo, all plopped within a ciabatta.

Quietly, gradually, over the past few months, Hawthorne has begun introducing just such twists and tweaks to food service, subtle enough that even bonafide regulars, like myself, might not be fully cognizant. First came the sandwiches, populating said cooler case like slow-mounting sentinels staking appetite claim. Then build-your-own was introduced, along with refreshing decision fatigue — you want something “Signature,” or something “Impossible”? You want something with housemade pimento or something, with, no, this is not a question, you absolutely want the horseradish-y “Magic Sauce.” Then suddenly, all at once, steaming wispy steak wedges unfurled out of that yeoman-like paper wrap in my living room, and everything was at once very different. Tender and saucy, indulgent but not quite sinful, butcher quality but quotidian, the prime rib hit like artisanal Arby's, with the battering, brawny meat-and-cheese mouthfeel of a Chicago corner Italian beef. Yet the package stays compact, tight, everything lovingly nestled between the bun’s charry insides. “Sandwiches are my love language,” chef Kelly told me one day. And it’s a message well understood, even all the way back home, from the couch, the protein pocket holding structure enough to comfortably be tabled atop an upright belly, one sprawled expectantly waiting for an afternoon of football and meat to commence.

It seems refreshing to be able to offer such a bold reappraisal, yet again, of Hawthorne Coffee Roasters, a place that for seven years has operated as the de facto beating heart of this little nook of airport-adjacent land known as the Town of Lake. Through their days the former bar and bowling alley has stood quietly stoic and resilient on Howell Ave. Nurturing, mothering, Hawthorne acted as home base for the dearly departed and deeply missed Foxfire food truck, as an incubator for the recently passed Iron Grate BBQ, as a host for the Sunday waffles and sandwiches of Press. It’s such a narrative of nice and community that it may seem easy to overlook why they opened in the first place — husband and wife owners Steve Hawthorne and Kendra Barron realized they didn’t have a coffee shop walkable from their new home. Talk about grassroots.

They used the pandemic to lovingly refurbish and rearrange, adding prominence to the bar and to an extensive booze collection, smoothing some rough edges, giving the sprawling space a sprucing while maintaining that unfussy, lived-in feel. There remains a scruffy charm, impossible to acquire with all the shiplap and mason jar bulbs on all of HGTV. It’s a vibe inherent from the spirit of a southside tavern, where years of all sorts of pouring and spillage and jovial clinking of glasses and coming together of friends has yielded a hardwon, comfortable wear-and-tear. Where their cavernous second room could often feel too big, bordering on empty, now it offers elbow room for those of us tip-toeing toward normalcy in these maybe late-stage pandemic times. There’s ample acreage to let your kids sprawl with art, or a patio to while away a sunny day with a Greyhound, a disarmingly refreshing espresso and tonic, or any of the stiffer cocktails cooked up by Hawthorne since his days working as a bartender at Bryant’s and the Jazz Estate. Of course, some regulars have seemed to make it a work-from-home office, and, yes, it’s still a place to simply stop and grab beans or a cortado. But it remains spiritually libertarian, undefined in that European, romantic third space sense of the word cafe. Sometimes I go for a coffee and end up with beer — not every journey needs to be predefined.

And now, so seemingly begins another chapter, entirely their own. With the prime rib, with a heartwarming cup of luxuriant broccoli and cheddar, with a “Big Ass BLT” of golden buttery finish, slabby blackened bacon, subtly slicking mayo, comes a feel of revelation. Like when the parks department went all in on beer gardens, like when the Beatles added Billy Preston — here is something so unquestionably solid adding an entirely new dimension. Now it’s impossible to imagine the before times, to remember when a view of the lake at South Shore came without the expectation of an ale, to guess at what “Don’t Let Me Down” might sound like without that electric piano.

There is an almost indefinable joy in finding a neighborhood place, one to call your own, one to make you hear the opening notes of Cheers in your heart as you enter and another smiling barista welcomes your children by name. When that place offers such comfort in an uncomfortable world, acts as an oasis of calm, it is simply asking too much that it might sometimes still excite. It’s easy to want to tell everyone, to shout from the rooftops. Though, truthfully I mostly wish to keep it all to myself, hunkered in a back corner with a book and a pourover of Guatemala, and whatever is the current lunch special on the way to my table.

0 notes

Text

Best Christmas TV Episodes

The A.V. Club

"Ho-fucking-ho," says Christopher, surmising the push pull hustle bustle of the season of strong-armed sentimentality. One of the funniest installments of one of the funniest seasons of The Sopranos opens with Tony stalking an empty Asbury Park boardwalk, haunted, like all of us that have had to murder our best friend for being a rat, by ghosts of Christmas past. But most of the episode is really a pitch black comedy tour of north Jersey holiday angst, or, as Dr. Melfi calls it, “Stress-mas." Tony tells It's a Wonderful Life “enough already;” Bobby is told "you’re Santa, so shut the fuck up about it;” Janice struggles in a Carlo Rossi-fueled Christian contemporary songwriting sesh, despite encouragement from narcoleptic Aaron — "it's a great mother-jumping lyric.” We get the backstory of the pork store becoming the family clubhouse — old man Satriale put a bullet in his own head after a bustout. There was a lot of sadness on the block, yet, it was “nothing a Christmas ham couldn't fix."

But lingering dread is mostly bestowed by the looming shadow of Big Pussy — excellent Santa, bad friend. We see him in flashbacks, and feel his unholy ghost in the hilariously chilling callback provided by a Meadow-gifted Big Mouth Billy Bass. It’s a writerly metaphor for seasonal pangs of nostalgia, and a sendup of how we enter this strange, forced year-end reckoning that that jolly home invader brings about every December. Maybe Paulie Walnuts, giving us a modern update on “humbug”, says it best: "in the end, fuck Santa Claus.”

0 notes

Text

“Irreverant”

The A.V. Club

It is probably a bad omen when a crocodile devours the officiant at a wedding. But these things happen, down under, with a scream and a tossed bouquet and, soon, a shoulder shrug, and then a “not another Reverend'' air of exasperation. So opens Irreverent, a twee, not so irreverent premise-driven comedic drama that pits sunny, beachy Australian gallows humor against cynical American opportunism, and lightly roasts religious dogma with Mafia cutthroattery.

Paddy Macrae sets his tale in the fictional, wonderfully named Clump, a fill-in for Clump Point, that was shot, lovingly, sunnily, in Mission Beach, Queensland. The country’s gold coast imbues everything with an air of warm breezy bullshit that swirls through the tiny town’s stereotypical plot of petty criminals, slackers, and half-lovable beachbum Luddites. All of them marinate in endless blue sky and blond beach and breakfasts of vegemite, along with the same quotidian frustrations as back here, on the other side of the world.

Colin Donnell stars as Paulo, a kind of reverse Crocodile Dundee, a generically good looking leadman, the kind to play as a perennial mom favorite on a network medical drama — he was Dr. Connor Rhodes in Chicago Med. He hits like a down-guide cable TV Ryan Reynolds, a dollar store Justin Theroux, with continuous five-o'clock shadow and smartass gritted teeth and brow-furrowing air of annoyance as he half-heartedly grapples with questions of faith and humanity. Questions he wanted nothing to do with in the first place. In Chicago he operated as some type of mafia mediator, one able to fall back on loose and affable charm — “you're not gonna send me to heaven tonight, buddy,” he says to a would-be hitman. In that case at least, he was right, minutes later ending up the last man standing over a mountainous briefcase full of someone else’s loot. He takes the money and runs, not stopping until his conscience lands him in the pitiful web of a hard-drinking ex-Reverend in Australia. Paulo is capable of mafia negotiations, auto theft, pick-pocketry, fisticuffs, he even plays a little keys, but when he wakes up on the first day of lamming it, with his stolen wares missing, he needs to don this holy man’s discarded robe to begin a trail back to what he lost.

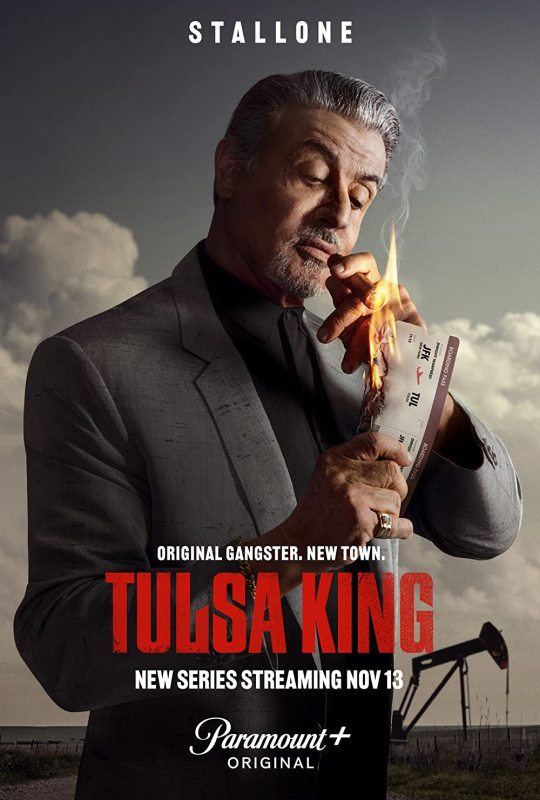

Yes, the premise makes little sense, in an almost impressive way. Just know that the basic conceit is the contrast of a pseudo gangster connected guy spruced up — in his “dog collar” — as a leader of a faraway flock. It is a fish out of water mobster scenario, unfortunately premiering the same month as another, flashier one — Tulsa King, featuring a septuagenarian tough guy turn from Sylvester Stallone. The difference, of course, is that that telling boasts one of the biggest Hollywood stars to ever live and two of the most gifted showrunner/writers of this generation (Taylor Sheridan and Terence Winter). A generous reading could suggest that Irreverent is My Blue Heaven to that show’s Goodfellas (both movies were released within a month of each other, both angles on the story of real life mobster Henry Hill). But, really, neither are likely to leave much of an impression. While Tulsa scratches the boomer itch for muscly knowing swagger, this show feels like a whimsical early winter dose of sunshiney cutesy. Both feature a protagonist out of their element, snarky and bemused, doing what they know, instinctively, building a new crew, of sorts.

Paulo busily, worriedly tries to track down the man who stole his small fortune (P.J. Byrne as Mackenzie, in the comedic highlight of the show, recognizable for his role in The Wolf of Wall Street, another connection to Terence Winter and Tulsa King), navigating single-bar cell reception for hushed talks with Lou back home, the helpful sidekick, who helps and warns while stalking amongst his gym’s punching bags in Chicago. Meanwhile Mackenzie doesn’t see the reason he and Paulo can’t still be friends, he responds to a phone threat with, “you sound like Liam Neeson,” eventually refers to himself as Bryan Mills, after Neeson’s character in Taken, takes to calling Paulo during Zumba classes to leave Reverential advice on how to run weddings, pick Bible passages, etc.

At the same time Paulo’s former outfit back home puts out a hit, leading him further into the relatively safe confines of holiness and middle-of-nowhere, end-of-the-world Australia. Just when he thought he was out, they pull him back in. And back in, and back in, until inevitably, he’s climbing a belltower for reception, again, leading Palm Sunday mass, emceeing as holy man for the funeral of a dog, for the funeral of a beloved local bar owner.

Clump is a well-packed pantry of such stock, if not entirely unlovable, local characters. There is the hardass cop and village conscience, the god fearer, distant friends coming back together, wayward teenagers dreaming only of leaving, the star-crossed lovers, eager to tie their knot despite the last go round ending in a wedding video featuring the preacher getting “gnawed” by the aforementioned crocodile.

While it can often feel tender, even endearing, especially the blooming friendship between Paulo and his teenage roommate, Daisy (a wonderful Tegan Stimson), it is only ever really funny in a vaguely sophomoric, obvious way. And it tries very hard to be funny: The locals wager on how long the new Reverend will survive; Paulo smashes a broken religious music-bumping stereo with a rock; a hot-to-trot single volunteers hornily, to “give him mouth to mouth;” he uses the Lord’s name in vain, obviously; he explains a mile is a “masculine kilometer.” He wonders why “everything is so far apart” in this foreign land, as he runs on the sand, pondering why the town is “stuck in 1982.” He researches at a generator-driven, dial-up connected internet cafe. A non-believer clumsily reading from the big book up at the pulpit is funny, but, it’s the church — talk about low hanging fruit.

Everyone needs him for different reasons, and, yes, he comes to need them. In the meantime most of the characters spend time bumping into one another, “shouting upstairs waiting for answers,” as one townie refers to praying, everything playing off the belief we have in people in a costume, in a role. “God doesn’t even know where Clump is,” one character opines early on. And that’s really what the show is about: being lost, and found, as Paulo says, “at the end of the world, sweating my balls off, slapping mosquitoes, fighting off… bogan’s?” By the end of two episodes you’ll have a good idea what a bogan is. And by the end of episode five you’ll be primed to make “then you might be, a bogan” jokes yourself.

0 notes

Text

“Tulsa King”

The A.V. Club

When the trailer for Tulsa King premiered during the NFL’s week six broadcast of the Buffalo Bills vs. the Kansas City Chiefs, the league’s early season heavyweight title bout, it seemed more than apt — the show promised a punchy, swaggering, sporting choice of violence, featuring the television debut of Sylvester Stallone, and offering the most stout shoulder and jutted jaw this side of the gridiron. Sly’s said goateed jaw protrudes as if chiseled out of mossy stone, his voice tumbling throatily almost through marbles, eyes half shut part in tough guy disinterest and part brawny boxer brain damage, his biceps prominently feature an unnatural highway system of veins. The show poster promises one star at the top, one name needed: “Stallone.”

As he ships a package the man behind the counter asks, “any flammable liquids or firearms?” and the audience is supposed to feel a collective guffaw, a notion of, “dude, this is Rambo!” We are all in on the joke, in on all of the pedestrian one liners from the trailer: “If I stopped eating every time somebody tried to hurt me I’d be a skeleton.” He is coy and he is rugged, he is out of place but unto himself, he is only a gray hair in a suit, but, in the words of Mickey, he is still very much a “greasy, fast, 200-pound Italian tank."

For all the noise and bravado though, the Red Bull and fist pumping vibes that seem to frame the energy of hungover Saturday afternoon frat house fare, what is easy to miss, aside from the promise of “From the Creator of Yellowstone,” is that the show was helmed by one of the most original and promising writers in Hollywood. Taylor Sheridan wrote Sicario in 2015, a twisty, criss-crossing, paranoid and depraved look at the war on drugs, at machismo, at shady government dealings, at, well, shady personal dealings, in a picture as confounding and fractured and dark as could be expected of a major release. He was then nominated for Best Original Screenplay for 2016’s Hell or High Water, an impeccably structured bit of neo Western crime noir that would make the Coen Brothers jealous. It’d be almost easy to overlook Wind River, a windswept and chilly and chilling thriller much more hopeless than ‘Hell.’ In just a few years, as a writer, the man originally known as playing David in Sons of Anarchy, seemed to have channeled and repackaged a special modern blend of Cormac McCarthy and Larry McMurtry, with a sprinkling of Sam Peckinpah and the sonoric spirit of early Warren Zevon. His voice is lean and unsentimental, accompanied by a vision full of menace and the darkness just beyond the reaches of a prairie campfire.

Here Sheridan pulled a different type of trick, penning the original story of ‘Tulsa’ in just three days, supposedly, before handing the project off entirely to Terence Winter, the writer and producer known for work on The Wolf of Wall Street, Boardwalk Empire, and, yes, The Sopranos. Winter acts as surrogate showrunner, and seems grateful for such an entirely new entree for a Mafia story. “Mobster in cowboy country,” is how he describes it, specifying this particular variance of fish out of water, yet we are comfortable miles from Steven Van Zandt repurposing Silvio Dante for Lilyhammer.

Allen Coulter directs the first two episodes, in an act of full commitment to the Davic Chase antihero oeuvre. (Max Casella shows up too, in a seeming winking nod to Sopranos acolytes). As we open Stallone’s Dwight Manfredi is found leaving prison, scoffing at the new Manhattan of Apple stores and VR headsets, on a path to rectify the sins of his past, build a new life, accrue something of a new crew. “I married this life, I’m gonna see if it married me back.” At his welcome home party he comes in hot though, “don’t stand behind my fucking back” he barks, wasting no time getting down to the ludicrous business, his fists cathartically going thwack and pffff, mixing it up with the beefy boy men at the head of the family (led by Domenick Lombardozzi), those responsible for his 25-year residence in “college,” as they might call it. All of them are near caricature-level quick to the draw on the chest-puff snarls and the finger-pointing and spittle-inducing toughie platitudes, the pissing contests of former football players in business casual residing in tasteless Mcmansions. He eventually accepts his “banishment,” that there is “nothing left for me here,” and provides some mild exposition about an ex-wife and a daughter who “hates me.” “Why not?” he asks, and if you’re hungry for more explanation he might tell you he’s in “the none of your fucking business kind of business.”

Either way he lands in Tulsa with vague assignations dealing with “horse races,” immediately hires a driver (an endearing Jay Will as Tyson), strong arms his way into the medical marijuana business (fronted by a stoned, deadpan Martin Starr), and bounds the realms between mountainous stoicism and semi-comic violence. Yes, Dwight might use a canteen, thrown like a shortstop turning two, no less, to combat a security guard, but he also might deadpan lament prison’s tiramisu. He uses the threat of a foot stomp, but it’s cooked with a base affability, as he explains “we’re partners,” and persuades with a “don’t make me be an asshole about this.” He is the buddy you like going places with, the one who can befriend any bartender (sad boy supreme Garrett Hedlund), who throws 100’s around like he’s paying off penance for a “lifetime of bad choices,” but can also wax on the finitude of “crossing the Rubicon,” or, say, Arthur Miller versus Henry Miller.

Like Sheridan’s best moments, Tulsa is a story driven by character, a character with baggage. It is a familiar against-the-world trope of redemption and second chances, and also a geriatric take on the blockhead underdog tale we’ve all known and loved Stallone for since those earliest rounds, those charmingly awkward dalliances with Adrian. Still the vibe is of much lower stakes, like a medium burn cruise along with an old friend who’s found new perspective. From the backseat Dwight ponders the brave new world: “GM’s gone electric, Dylan’s gone public, a phone is a camera, coffee is five bucks, the Stones, god bless ‘em, are still on tour.” Such minor key riffage and some stoner hijinks fill the long slow Oklahoma drives — wanna see Mickey Mantle’s childhood home?— that themselves buffer the contemplative scene-setting preparing for a glut of preordained violence.

But most of the early going is a long way from Winter or Sheridan’s most inspired work, and more like something indeed cooked up in a short amount of time, say, in a stir-crazy pandemic weekend, something less apt to get married to than to pass along to a colleague while you go back to your Kevin Costner project (Yellowstone season five premieres the same day as Tulsa King), or your Jeremy Renner project (Mayor of Kingstown season two premieres in less than two months). It helps if said colleague might overlook the cliched daddy issues that seem borrowed from Rocky 5, or the it’s-a-small-world storyline lent directly by one of the most beloved episodes of Sopranos season one.

Still ‘Tulsa’ ranks as another sturdy chapter in the volume of prestigious, showy 21st century antiheroism. “Go West, Old Man” is the name of episode one, making thematic motives clear. Here we are, actor and character repolishing, reawakening in a new background. There is not too far of a line to be drawn to Jeff Bridges’ recent work in The Old Man, another story of a, yes, old man, crafting a new career bookend before our eyes, another leading dog doing it now with gray in the beard, revisiting old tools and tricks while learning some new ones. Stallone, for his part, is actually quite funny, quite often. “If I can change, and you can change…” indeed. It’s a reminder of an American icon so known it’s easy to take him for granted, so one-hue it’s nice to see a flex of different muscles, so undeniably charismatic he’s welcome to take a country ride with.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Sherman’s Showcase”

The A.V. Club

There is no laughter more hollow, no handclap or whoop more soulless, than that ignited by a traffic signal. To understand the applause sign is to consider a dated, insulting notion that we, the audience, maybe don’t really know how to watch, consume, appreciate. And yet it remains an integral part of the late-night talk show rigmarole wherein a man in a suit reads topical jokes from out-of-sight cue cards as America puts on its jammies. Even new takes on the formula abide the old slight to the idea of a present, subjective assembly. Maybe by now, in the late-night game, we’ve all just grown tired. In the wake of the end of the shows of Trevor Noah, James Corden, and Samantha Bee, The New York Times recently asked “Is There a Future for Late-Night Talk Shows?” It seems, with declining interest and the ascendance of streaming, with a growing reluctance to hear tired jokes about gas prices and the vice president from a soundstage in Rockefeller Center, it may be time to lay the old dog to pasture. How? Sherman’s Showcase seems to ask. Well, skewer it to smithereens, apparently.

At the opening of each episode, yes, a suited man stands, ridiculous phallic Bob Barker microphone in hand, dark shades and immaculate beard immovable, a lounge singer’s smug suavity, preacher’s aloof charm, deep throaty voice assured and practiced, the air of a confident and consummate emcee to lead one toward nighttime delights. But then, for instance, he might go into a quick and breathless tangent: “I can’t wait to start the show, but before we get there allow me to summarize the plot of Mulholland Drive. You see, she shoots herself. Great movie.”

Such is the course and absurd tenor for most of the show, as it evolves or devolves or dissolves or aimlessly winds its way toward some unholy amalgamation of asides, backstage glimpses, interviews, live music performances, music videos, previews, movie trailers, animation, award shows, game shows, commercials, even a video game - "there was 16 minutes of text back and forth before the game even started." It is all vaguely, conceptually sketch comedy, sure, in spirit, but strung together with an uncannily and uniquely propulsive bump.

The man at the center of it all, Sherman McDaniels himself, is Bashir Salahuddin. His sidekick, Dutch Shepherd, is played by Diallo Riddle. The real life duo met at Harvard before embarking on a union of writing and video projects, landing as writers for Jimmy Fallon, creating the cult Comedy Central show South Side, and eventually birthing Sherman, which premiered in 2019. This latest iteration of their creative offspring is pitched as a kind of offbeat parody on Soul Train, American Bandstand, Solid Gold, some other 70’s show you’ve likely heard Questlove reminisce about. But it actually feels more in common with the work of Christopher Guest, I Think You Should Leave, and some freaky fever dream of a sativa-baked In Living Color writer’s room where the editor has gone on vacation.

Season two is a continuation of the team’s well-honed brand of quick-hitting, time-hopping narration, giving a 360-degree view of a beloved musical variety show. For this go they’ve brought back John Legend as producer, occasional guest, and, from the sound of it, probable co-songwriter. Guests also include Issa Rae and Chance the Rapper, and everything remains very much in the IFC brand of “Slightly Off,” in the faux-serious vain of Portlandia, and not unlike a completely problematic step-sibling of Documentary Now. We have straight-faced commitment to musical numbers like “Epulets Fall in Love” and “I Love You, Sike;” an overlong and artful treatment of a Wes Anderson twee fest, in the trailer for Forty Acres and a Blimp (“coming soon to theaters in Cannes, Silver Lake, and most of Brooklyn”); simple silliness (“Cognac, you my only friend,” takes a sip, “that is not cognac”); and coy zingery: a voiceover announcing a past show’s guests welcomes “the face of hope and change in the Democratic Party, John Edwards!”

Like with any assorted sketch show, like a book of poems or a big league slugger where half-the-time success equals greatness, not every effort works. One of the earliest bits here, a trailer for a flick wherein Mary J. Blige attempts a heist to take down P. Diddy, won’t let go of its search for a tag or a throughline, and comes off like clumsy and warmed-over SNL. But even in flatness is shown real willingness to gamble, to try, there is a stretching and a belief, bordering dangerously, deliciously on recklessness. At times the writers treat the audience with so much trust it almost feels like indifference. Especially in trailers for the likes of Not Passing. The kernel of the idea can almost be seen, framed in late-night smoke and soundtracked by thigh slaps — what if we take Passing, and, do the opposite!? Similarly, consider, That’s The Spirit. An African soccer phenom’s father is a ghost, who is a soccer ball. As his mother prepares him to have a new sibling, the poor boy can’t stop asking her how his ghost soccer ball father conceived a new child. A tag line promises “A story of forgiveness.”

On paper this shouldn’t jive with a strangely poetic black-and-white segment on the perspective of the show’s security guard: “in reality nothing is secured, security is a fiction, a pantomime.” Nor should that gel with an old animated Sherman-penned series, Dumpster Buddies, featuring his friend “Obese Maurice,” which we see as he discusses on an expose-style Frost/Nixon-esque interview. But everything moves and flows with such assurance, style, a slinky and soulful rat-a-tat tempo that inevitably leads back to a song and dance routine far better than it has any right or need to be.

Salahuddin, the center of nearly every bit, the eye of the hurricane, is a forceful revelation. Part caricature and part chum, delusional but familiar, it’s hard not to think of Danny McBride in The Righteous Gemstones or anything else, with that always-semi-disbelieving head cocked slightly back, an overcooked swagger turned so high, so ridiculous, it becomes something benignly, lovably goofy. In the digressions, the deviations, wondrous casual remarks, there is such a sense of timing, such laughable machismo, it is easy to almost feel the need to lean forward, to catch the next line, to not be able to look away from the somehow hip awkwardness. In a George Clinton parody, Sherman states, “God wanted a style of music that involved way too many people, so he invented funk.” And so Sherman, the show, moves, with a party atmosphere and large contingent of creators moving and shaking and offering something at once neurotic, silly, feel good, and singularly smart. It is also a line indicative of the writerly attention given to almost everything Sherman says. There is not a moment of dead air, not a second without something like realizing that, to Sherman, five plus six is 12, because he “always rounds up.” Of its time, the end product feels almost like scrollable sketch comedy—if something doesn’t work for you there’s surely something, something else, coming right behind. Something else in a steady, heady funk, set entirely to its own beat. Something delicious because you don’t know quite how to process it and nobody is giving a clue.

0 notes

Text

“Thai Cave Rescue”

The A.V. Club

There’s something about a kid in a well.

Even if you don’t have registered memory of the 1987 “Baby Jessica” ordeal — with endless CNN coverage, commentary from President Reagan, a Pulitzer for photography for the rescue coverage, an ABC movie starring Beau Bridges, the Regis and Kathie Lee interview — somebody has likely harkened the spirit of the Texas tale at some point in your life. Some caretaker, believing in the motivating factor of fear, maybe, using the story to caution on the perils of carelessness, the nefarious threat of nature, the ubiquitous presence of terrestrial body-swallowing vacuums lurking in the tall grass.

Irresistible as a narrative, the trope is a very literal projection of Kurt Vonnegut’s infamous “Man in Hole” story type. Somebody gets in trouble, gets out of it, and ends up better than before. “You see this story again and again. People love it, and it is not copyrighted,” said Vonnegut. And if there’s something about a kid in a well, well, who could resist 13 (13!) young ‘un’s stuck in a cave for 18 (18!) days?

Which speaks to why the years since the July 2018 rescue of 12 teenage boys and their soccer coach from the flooded limestone Tham Luang cave in Thailand have seen a barely countable number of screen projects. The Cave led the theatrical way in 2019, giving focus to rescue diver Jim Warny, who played himself. Last year came a Nat Geo documentary called The Rescue, which used body-cam footage of divers. Ron Howard gave the story a Hollywood treatment, fronting Viggo Mortensen and Colin Farrell in the Australian-shot 13 Lives, recently out on Amazon Prime. At least two other studio projects have been announced and, so far, unfulfilled. In the meantime, a re-edited version of The Cave has been cut for digital release as Cave Rescue.

Got all that? As Al Ruddy, producer of The Godfather, said on a recent episode of Marc Maron’s WTF podcast, “every movie is a movie.” When the movie is made about the makings of the big and small screen efforts of this miraculous story of survival and heroism, Netflix’s unfortunately-titled Thai Cave Rescue will at least be able to tout its authenticity as having both a Thai director and exclusive access to both the cave and to the boys themselves.

Though it is most probable that all tellings straight wash each other out, here is a story about defying odds.

This limited series version of Rescue opens with a world-is-watching spectacle: a slow motion montage, barrel-chested men with beards and without shirts carrying ropes and flippers and oxygen tanks as Times Squarers and pub-goers the world over watch on screens like it’s a bated-breath rocket launch. String-swelling unification aims at the pathos of the moments before a sports movie’s big match, or like a Sunday Night football game featuring the Patriots or some irredeemable evil that humanity can collectively root against. Of course, if you follow these things, kid-in-well stories almost never end well. (One of the rescuers of baby Jessica died by suicide after suffering from PTSD. And that one did end well).

Eventually we are set back and plopped into the jungles, and into the rain, and to the exotic backdrop of “Northernmost Thailand,” on the border of Myanmar, ramshackle and lush, with leafy vegetation and operatic mountain ranges spiking forever against eerie myst. Vaguely Eastern-isn music sets the vibe, as we are introduced to a myriad cast of precocious, maybe-bummed, half-hopeful teens and their unflappable coach, Eak. The gaggle of impish buddies each get their own introduction, character ticks and background stories briefly plotted, as a terrifyingly obnoxious title card counts down the hours until shit hits the fan, monsoons fill the cave. It feels vaguely like a more doomed Stand By Me, or maybe Stranger Things, with teen and pre-teen pals — the so-called Wild Boars — inextricably linked on a journey of self-discovery, triumph over adversity. Or, in this case, a journey of not starving, somehow not despairing, and waiting around while someone figures out how they might not die.

There is much backstory to compose and juxtapose, and so we are bounced around.

An instantly-summoned amateur cave explorer, making for a convenient narrative device, knows an almost suspicious amount about the caves, how rain gathers therein, how to talk convincingly in a Michael Caine accent over charts while leading a command team with wit and metaphor. There is a park ranger, who cares, a Ministry of the Interior, who does not care. An intern named Noon at the meteorological center is not taken seriously because she’s a woman, while her piggish boss is distracted by soccer and handicapped by a fear of authority. Eventually we get the local Governor, a seeming father of the situation more than a hero, gentle-eyed and honest. “I believe more in science than faith,” he says often, softly conjuring sympathetic images of “our boys,” with occasional breaks for quarter-baked halftime speeches, as needed. Highly specialized cave divers are summoned from around the globe, as are Thai Navy Seals, and the U.S. military, for support, and baseball-hatted bravado. A hydraulic engineer appears, with brows furrowed and measurements already taken.

The hours tick, in an echo of the nature-gives-zero-fucks predicament porn of 127 Hours or Open Water. You know how it ends up, or at least have an idea. But by the middle of episode two they’ve already been underground for one week, and after some fart jokes, tries at song (“anything but Maroon 5!”), and half-efforts to dig, there is not much for the boys to do but wait, be sad. Eak is certainly a hero, keeping the group tight and calm, but one mild and meditative, without much options for action. With our protagonists stuck, there’s a quickly disintegrating point of view, little hold to a grounded storytelling center. Such is the way when most of the heroes are secondary characters, when much of the action is inaction, when the real moves of a thrilling story are actually sprinkled around the edges of centerstage. A bevy of parallel rescue efforts happening outside don’t have much in common or any great velocity on their own. And it begins to feel a bit like watching Alive, with snow replaced by limestone, survivor’s grit replaced by ennui, without any of the grisly payoff of cannibalism.

Questions of spirit turn to a race-against-the-clock puzzle piece. “We need a new rescue plan,” it seems the Governor is saying every 15 minutes. And plan they do, vacillating between bad and worse choices: teaching the kids scuba diving once they are found, drilling them out by alternative route, waiting months until the end of the monsoon season dries the caves. Viewers begin to learn, obliquely, about hydrology and soundquakes, we get glimpses of drills, then obscenely phallic sci-fi-leaning drills, there is something called a dragon pump, something called an aquifer. There are big rulers and weather charts and much talk of the water table. Between this are the life platitudes: “The most important duty of family is to love each other,” “sometimes we get to choose family,” guilt over bad goodbyes, reminders that “families are complicated.” Scientists get rained on, have epiphanies, they splash water in frustration, they go back to the drawing board. Families hold vigil, try to appease the Gods, they write letters that are curried by divers, they get rained on.

For as much as it can seem interesting and tense, the six-hour treatment begins to feel stagnant and bogged, like one of those coffee-ringed New Yorker articles that sits open on your desk for weeks, too long and too tangential, but with enough of a feeling of investment to slog on, if only because finishing it will give you enough anecdotal ammunition to feel interesting at your next cocktail hour. And interesting a viewer will be, because the facts of the story boggle logistical sense. Which is why in the end the entire enterprise of production, of all the productions rolled together, seems a bit ostentatious—here, at least, true life would more than suffice even a Vonnegut storytelling impulse.

As a type of inverse of a sports movie, with an impossibly-distanced finish line, it actually seems borderline cruel. Almost to the point of necessitating a parent trigger warning: watching the children’s guardians go from concern to dread to frenzy to despair is a grueling churn. “Night must come back for his cake,” says one mother, planning her son’s birthday for that very day. A gut punch of a line, it is also easy to wonder: why the melodrama, plushed and padded and stretched and string-scored? There’s a guilt-ridden privilege to watching from the couch, late at night, with a glimpse at a baby monitor to see some kids sleeping safe and dry and sound.

As we swim half-blind toward the conclusion that is promised right in the title of the show, it is natural to hope for nothing but less drama, less dramatization, less exposure and exploitation of their terrible and then improbable good luck. Though on this project the Wild Boars were actually compensated, through the Thai Film Board, for their story rights, it seems far deeper to wish, for the boys and everyone around them, something closer to normalcy and remove. It’s not a desire of conclusion or release, but rather an end, so that they can simply get on with more days of sunshine and fresh air.

0 notes

Text

“Mike”

The A.V. Club

Mike Tyson is mad. The former heavyweight champ, convicted rapist, and star of the Adult Swim animated series Mike Tyson Mysteries, after calling Hulu’s new limited series on his life “cultural misappropriation” last year, came back with somewhat stronger language this month: “Hulu is the streaming version of the slave master. They stole my story and didn’t pay me.” Of course a network needn't pay to tell the story of a public figure, and, of course there is further personal interest from Iron Mike: he is working on a Mike Tyson project all his own. (Also, here he is quite clearly indicted as something of a monster, but more on that later.)

Moreover, Mike Tyson being angry feels as much a part of the public performance of the character of Mike Tyson as any real emotion. He’s a whole vibe, as the kids might say. And, depending on when you were a kid, today’s headlines seem a continuation of the peppering of pop culture that may extend back to, say, the video game Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out, or the surrealistically disastrous Barbara Walters interview, or the infamous Holyfield ear-bite fight, or the Spike Lee-directed one man Broadway show, or, maybe the cameo in The Hangover. Earlier this year he made headlines for punching a heckler on a plane. While that guy certainly had it coming, it was further evidence of one of the most famous men ever, being famous for being famous, existing as the shadow of a boxer known for many things aside from beating an elite opponent in a big moment.

As for this show, well, here we go back, to Brownsville, Brooklyn, a one-dimensional character in and of itself, looking bombed-out and smoldering and hopeless. It’s the kind of place where cops shoot young black kids for petty crime, where roving packs of amoral hoodlums roam the streets past tin drum hobo fires a half-step from Mad Max. It is a dystopian stage of shadows the show repeatedly would like viewers to remember as a part of the whole Tyson package. Against this we meet a young Michael, a “retarded fat fuck with a lisp,” a sympathetic tyke who can witness a brutal one-two between his mother and father involving scalding soup and a sauce pot with numb familiarity. We follow him in rapid succession from flop houses, watching his mother sell her body, to group homes and juvenile detention centers, everything clouded by crippling poverty, an absent father, and a maternal figure that feels like inner-city Livia Soprano. Tyson was arrested 37 times by the age of 13. The crime math, like the ring math — he won his first 19 professional fights by knockout, 12 in the first round — defies sense, reason, a man's ability to sit at ease with himself. “Why should I have compassion? I didn’t have a future,” he ponders.

With the one-man show acting as an easy narrative device, we are introduced to Trevante Rhodes as Mike as latter-day raconteur, reflective and rueful, yet still boastful, swaggering. With impossibly loud lats, illegal-looking traps, he stalks the stage in his physique that still looks fresh from the set of Moonlight, in white suit, bald head and face tattoo. An adoring crowd eats up his meandering presentation like he’s unveiling new iPhone tech. He has down that disarming cutsiness, the aww shucks wrist flips, that high whispery, ever-lisping voice, that slow way of moving his head, as if he is trying to process a foreign land while also suffering from CTE.

We open with a quick glimpse of the ‘97 Holyfield debacle, before Tyson breaks the fourth wall with a “No no no, fuck that shit. Not gonna start here, theres a lot of fucked up shit we’ll get to.”

And there is, bobbing and weaving on its toes, the show has a steep syllabus of audience-known timeline beats to hit. In between all the narrative though, we thankfully have the sweet science itself, with the flourishes that make boxing the most cinematic of sports. There is slow-motion brutality, whip pans, dollies, jump cuts, sweaty closeups, much kinetic intimacy with coiled and musclebound specimens, everything in the tension and the spectacle of the battle offering a cinematographer carte blanche to flex. And flex they do, with unmistakable punctuations of camera flashes, crowds in frenzy, quick flashbacks of injustices showing motivation — a beloved bird’s head is ripped off — title cards naturally setting the scene, the resounding thwaaack or pfff of glove to orbital bone, a hyperbolic announcer extolling “even Tyson’s punches sound different,” a slow-motioned face pancaked while arena hype music bumps, sweat raining interminably, blood donuts shooting from mouths in broken O-shapes. What rhythm, what fun, everything spiked by the catharsis of cranked-up DMX.

Such movements seem tailor fit for the punchy style of the writer/director team Steven Rogers and Craig Gillespie, the duo behind I, Tonya. In the same brawny vein there are fantastical asides to the audience breaking continuity, freeze frames, 70’s washed aesthetics, vintage needle drops — Bobby Blue Bland, “You Got to Move,” The 8th Day’s “She’s Not Just Another Woman” that might leave you fumbling for Shazam as Robin Givens makes a slo-mo room entrance. Everything feels like a contact high from a recent late-night viewing of a remastered Goodfellas. And then, like that, Scorsese is directly honored. Harvey Keitel shows up as trainer/mentor/father figure Cus D’Amato. Eventually a young Tyson laments: “everyone took a beating at some point,” echoing near verbatim a young Henry Hill. (Henry Hill also happens to be from Brownsville.)

Mike is formed by Cus, unhinged by his obsession with Robin Givens (Laura Harrier), guided and misguided by Don King (Russell Hornsby). He goes from cliched naivete (“are those roses?”) to cliched advice (“embrace your villainy”). We go from all-my-friends-are-dead depths to the impossible highs of fucking in a hot tub that’s inside a limo. Along the way he is diagnosed as manic depressive, becomes heavyweight champ, loses his heavyweight champ title, and is dogged by hangerson and questionable advice: Robin Givens’ mother advises the consulting services of one Donald Trump, “now that’s a businessman you can trust.” (Allen Weisselberg, chief financial officer of the Trump Organization, is also from Brownsville.) It all becomes a muddy, exhaustive wash of life punches taken and given, eventually rendering sport as secondary, human tragedy washing over everything else.

Episode five gives a bold rope-a-dope, shifting completely the narrative perspective to that of Desiree Washington (a star turn by Li Eubanks). She tells her story as the victim of Tyson direct to the camera, then the court, with unwavering steadiness, strength. Heartbreaking, story-bending, stomach-churning, the show seems to nearly bend in on itself, offering as graceful and moving as such a half-hour could be conceived. A striking, standout segment, it feels meant to be witnessed, felt, rather than commented upon. In a show in a world of excessive violence, here is a hard reminder the most brutality can come from the sway a powerful man has over a vulnerable woman.

For a story so often fraught with busyness, the jabs and the hooks and the ceaseless speedbag flow, that sad core can sometimes be forgotten. I, Tonya played with a similar tonal deficit, casting a villainous, problematic world class athlete in a light with style and playfulness.

Yet in a moment of the recognition of the fragility of the sports psyche, when the likes of Serena Williams and Simone Biles, Kevin Love and Naomi Osaka, are all speaking to the perilous nature of mental health among top athletes, as “the people that are supposed to be looking out for you aren’t,” as the mother of Robin Givens puts it, there seems almost too much to explore about the psyche of the man Mike Tyson. The price of celebrity, the personal cost of extreme success, how exploitative systems burn and churn their product. How he reconciled or failed to reconcile a loveless childhood with superstardom. Whether we laugh at, or with him, now.

Also, more importantly, how will he be remembered? As a rapist, a crazy man of ceaseless aggression and face tattoos, a domestic abuser, a video game villain, comedic relief, one of the greatest Heavyweight punchers the world has ever seen? History belongs to those who write it (historian Howard Zinn is also from Brownsville), and for the answer, we won’t have to wait for the next Tyson story project. “You don’t love me no more?” Desiree claims Tyson asked at the end of her attack. Here, chillingly, he addresses it right to the camera. Asking us to wonder ourselves.

0 notes

Text

“This Fool”

The A.V. Club

Nobody “Motherfucker”’s like Michael Imperioli. The mother is draaawn out, fired with the snarl of a just-pulled lawnmower, peppered with a deep intestinal rancor, the fucker coming almost as the release, the exhale, the purr of pissed incredulity as to whichever injustice the world has placed before him. In this case, it is Richard Branson, or, the “space knight motherfucker” who cheap-skated his donation to Hugs Not Thugs, the “fifth largest gangster rehabilitation center in Los Angeles,” that was founded by Imperioli’s Minister Leonard Payne. It is a welcome introduction to his character, and a delightful reintroduction to the livewire frustration bits Imperioli cooked up as Christopher Moltisanti on The Sopranos. There he was one one of the key comedic pieces on one of the funniest comedies nobody was ever even entirely sure was a capital-C comedy.

As it happens, here he is one of the key comedic pieces on a show that leads with a much more troubling type of tone confusion. In the first two episodes of This Fool, a drive-by is played for chuckles, a gang brawl is treated with nostalgic revelry by former members slowed by time and life and sciatic nerve hangups, and “Don’t Text and Drive” displays across the screen as an epitaph with operatic flippancy.

There’s also maybe a bigger conundrum facing the writer’s room, namely whether or not the comedy, in which Julio (Chris Estrada) counsels ex-cons, including his recently-released cousin, is actually, you know, funny. It certainly can be, as in the front-loaded first episode, where intimidating men with face tattoos perform trust falls, and Julio extolls the virtues of the place to a new arrival: “we remove more tattoos than anyone else in Los Angeles,” and offer “free legal counseling, solar panel installation classes.” Or, later, when he describes why there’s no reason he couldn’t be Bourdain: “I’ve eaten foy gray before.” To which his ex-girlfriend, Maggie, replies, “you don’t even know how to pronounce foy gray.” Imperioli, for his part, steals most every one of his scenes, especially striking an early chord on an extended lecture on failure, all wide eyes and faux wiseman profundity, his ability for humor amped by the ability to appear to take himself so stupidly serious.

It can certainly also be, as many characters chide, repeatedly, anything seen as less than real, “corny.” A Salvadoran is irked by being called Mexican, a deceased friend nicknamed “Fatass” has, yes, “Fatass” inscribed on his urn. Vacillating between groan and cringe, Julio’s cousin, Luis (Frankie Quinones), peppers ceaseless ball-busting with “gay boy,” and the likes of “y’all talk more than the motherfucking View” or, somehow, “you need a Viagra?” Perhaps it’s just more uneven than corny, more awkward than ha-ha, as smart as it is obvious, as oblivious as it is comfortable, taking real issues of modern L.A. — gun violence, gang culture — and setting them as backdrop thematic annoyances to be casually riffed on, as Bradley Newell might rap about the city on a Sublime track.

Once the show settles though, finding a groove akin to the svelty Chicano Batman theme that opens each episode, and with the delightful reliance on old school Soul — Brenton Wood, Bill Withers — and palm trees and Dodgers decorum and shit-shooting around the dining room table with elderly relatives, a lived-in flow emerges, settling on a rhythm somewhere between a bilingual Modern Family and a less lesson-y Gentefied. The stakes are mostly low, it’s always sunny in South Central, even when meeting “at the park at sundown” for a brawl, and by the fourth episode even the tightest of TV reviewers may do very well to take Julio’s epiphany to heart: “how about this? I’ll stop being a little bitch.”

At that point anyone can appreciate the physical humor of, say, Julio giving his nephews fireworks to shoot off to distract the family so he can slink away from birthday engagements, or Luis putting Julio in a headlock to keep him in place while the family sings “Feliz Cumpleanos,” or an elaborate and preposterous slow-motion ball-kicking scene, an entire episode homage to Austin Powers.

Estrada, who co-created the show and used his real life as inspiration, plays Julio with the same button-down, clean-shaven, subtly-pomaded nice guy turn that fills his standup comedian persona. He is mocked for having “lawyer hands,” is seen by his abuela as someone “always crying, just a little bit.” He is a man who sincerely and fully enjoys his pour-over coffee situation, coming off alternatively between sweet and cloying (“The life expectancy of a gangster on average is 24 years old, but the life expectancy of a punk ass bitch, 76 years old”), between big-hearted and petulant martyrdom, his use of “big dawg” renders him some varying mix of jovial and punch-worthy. As his on again, off-again ex, Michelle Ortiz breathes fire into the manic pixie ex-girlfriend template, with high-pitched outbursts turning to raunchily smitten tenderness. She steals/borrows Julio‘s Accord before berating him that the Check Engine light is on, she hits with lines like: “we’ve had sex in the backseat, it’s our car,” and interrupts‘s his date to get him to come over to help find a disappeared pet bunny, a la Annie Hall’s spider-in-the-bathroom scene, eventually trying to coax him to stay with, “I got Wendy’s. In the obvious spirit of ying-yang buddy comedies, Luis seems overtly ex-con doltish, overplaying the easy parts, leaning brashly into the casual homophobia. It’s not 2005 anymore, as he is constantly reminded — “Tobey Maguire ain’t Spiderman no more” Julio tells him. But has he been in prison, or a coma? Were we still making Viagra jokes and asking “does that make your boyfriend jealous?” in 2005?

Yes, it is a show about redemption. About tempering recidivism with good cupcake sales — “people love buying cupcakes from ex-gang members, if girl scouts ever start getting face tattoos we’re fucked,” states Imperioli, in one of his many steely deadpans. And it is about family, however dumb and unfortunate they sometimes might be. So, the standard themes of any harmless Thursday night family sitcom. Of course you can watch it when you want, as one of the best back-and-forth’s, between Luis and his ex-fiance, reminds us:

“You’re a fucking loser with a weird dick.” “Fuck you, curvy dicks are normal.” “You know Judge Judy will rule in my favor.” “Her show is over, idiot.” “She’s got a new one, idiot.” “What time? I wanna watch.” “It’s streaming so it’s available whenever.”

Within such ping-pong banter is where This Fool finds its pocket. Like when Imperioli, uber-stoic, over-intense, gets asked about his documentary, “Game Set Hope,” a chronicle of an actual ping-pong tournament on “skid row.” A tag line at the bottom of the poster for the film that hangs in his office declares: “A film you might soon forget, but shouldn’t.” So it feels things might go here. While we seem past the peak of standup’s getting TV spots, this is the type to be lost in a sea of professionally funny shows. Once rhythm is achieved though, This Fool is joyously, even exceptionally hilarious because of what it is really about: who will watch your shitty documentary, even though they think there’s too much flute in the soundtrack; who cares enough to steal you toilet paper from work, even if it is single-ply; who makes you your favorite Tres Leches cake, even though you hate your birthday; who shows up for you, even if a “homegirl” stole their Honda; and it is about being there for your cousin, even when he won’t stop quoting Austin Powers.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jeff Bridges and the Art of the Comeback

The A.V. Club

In 1997 Bob Dylan, in his mid-50's and without a work of original material since 90's critically-panned and objectively subpar Under the Red Sky, suffered a bout of near-fatal histoplasmosis pericarditis from fungal spores that forced the cancellation of a European tour and whole lot of severe chest pains. Shortly after recovering, Time Out of Mind was released. Ambling, rasping, muddily grooving, the late period masterpiece won three Grammys, including Album of the Year, and reasserted the old crag into the collective consciousness. Though he would publicly dismiss correlations between the album's themes and his bout with sickness, it's impossible not to hear "Standing in the Doorway,” or any of the contemplative, autumnal vibes, without being struck by wizened resignation and a late-night wrestling with mortality. Regardless, the work outvoices the man. And for the staunchest of Dylanologists it is his death album and his comeback album in one.

Though the wisdom-garnering is right there in the name, The Old Man is not Time Out of Mind. Really it's not even ‘93's World Gone Wrong, rife as it is with the trappings of spy procedurals and narrative bloat settling around the middle like a dad's beer belly. But in it, Jeff Bridges, with immaculate silver waves, luminous gray whiskers, all linen and weekend business-casual shouldery swagger, with his marbly gruff baritone, announces a comeback. In the way that Dylan used the trademarked Daniel Lanois production to reassert himself, Bridges uses the pedestal of prestige TV to again announce his presence after a well-publicized battle with lymphoma, and then COVID, that left him “pretty close to dying” in early 2021.

In a way it fits a career-long pattern of sporadic reemergence. After a breakout in The Last Picture Show Bridges seemed to fall into an easy rhythm of casual semi-stardom,with breezy Western nonchalance and a likability that gave the impression of little care, less to prove. Then came the 90’s. The Fisher King was a commercial but zany meditation on reckoning and redemption. For a story framed by a mass shooting, directed by Terry Gilliam, featuring Robin Williams at his holy grail-seeking max absurdist, there is a disarming level of tenderness. It’s hard to imagine another actor folding such macho swagger and frustrated pathos into Bridges’ humbled and bereft shock jock. Two years later came Fearless, an improbable Hollywood reflection on fear, grief, and mortality, that was in turns confounding, puzzling, and oddly real. The pair showed the actor reaching dad-ish middle age in a strange second gear, settling in while also sort of clearing his considerable throat as one of the most singular actors of his generation.

He pulled a similar one-two in 2009/10, with Crazy Heart and True Grit. In both Bridges seemed to be paying homage to the many Westerns of his early career, but viewed bemusedly from an easy grandpa’s chair. He suddenly somehow seemed more gruff, deeper, grittier yes, with a timelessness like faded Levi’s and Kris Kristofferson. Both felt Oscar-baity in a quieter, thoughtful, somehow unannoying way, while a reunion with the Coen Brothers, who gave him his most iconic role, seemed a gesture of Greatest Hits. While it could be easy to take him for granted, he could still be huge, all at once, in his own way, even while playing a bit to the back rows.

And now, The Old Man shows another level of maturity, another shelf in the case, if for no other reason that he gets to do it while driving a 7-hour-vehicle. Consider the trick Bridges pulls from the closing moments of the fourth episode through the opening of the fifth: he goes from pleasant head-cocked dinner table charm, to looming rage, to acquiescence, to raspy nodding acceptance, in moments.

And it all feels believable, like a bit of disappointed dad manipulation, where you can’t tell exactly who is being convinced of what and to what end. He is a domestic antihero, at once capable of a warmth that is welcoming and a gravity that is intimidating: loving enough to shed a tear, almost, for having to board his dogs, hard enough to bark a shut up command before stalking away with nary a look back.

As a father, Bridges’ Dan Chase is the type to casually toss a “what happens to me, happens to me, that’s not important.” Or philosophize on “the series of events it took to create this moment.” He might scold for missing the agreed upon pickup spot, while furiously commanding a speeding getaway boat. He can be dismissive, “you read it wrong,” or metaphysical, “sometimes there are things you don’t get to know before the curtain comes down,” or unforgivingly passive-aggressive, “I’m sorry this is the hand you were dealt.” He can convince, with only trace condescension, a civilian of being a “highly trained operative.” Likewise he can dadsplain tradecraft, that of yielding “two weapons in concert, in your left hand is your empathy, in your other hand… your ruthlessness.” He’s discoursing on his usual C.I.A. shit, yes, but he could just as easily be discussing methods of potty training or coaching little league.

So it goes with such callbacks to all the heavy-hitting big screen fathers, there are traces of the wounded devotion of Donald Sutherland in Ordinary People, the no-bullshit guidance of Laurence Fishburne in Boyz n’ the Hood, even the mischievous outside-the-law incorrigibility of Royal Tennenbaum. He could also, somehow, probably, kick Liam Neeson’s ass. Or at least keep him quite busy. Not like what you see in your dad, maybe, but what we all hope for in the narrative of a loving, protective father. And what your dad might see in himself after three Heinekens.

“I learn by doing” and “the weak are mostly dead” are throwaways, and if you can picture another actor delivering such lines, it’s not as easy to see someone else physically embody such a presence. Like the way he sits on a bed after a day of traveling, fortifying against rising fatigue as much as the chasing years, nearly reminding himself to hold steady against gravity, defying weight and biology with focus and good posture. When considering a reply he often has a way of holding his mouth open for a beat, as if the lips themselves are considering all the potential arrows, all the weight of experience with which to load his bow. He seems "sick with experience" as Robin Williams’ character in Fisher King might put it.

After the show’s beautifully taut, whiplike opening episodes, everything downshifted toward the finish, maybe necessarily, maybe for the best, as the feel took the shape of a shaggy dog spy story kept mostly afloat simply by Bridges’ being. But losing steam, it seemed to feel the need to explain and over-explain itself, everything getting bogged in a sort of sentimentality. Like, well, yes, an old man. “Everything’s in free fall all the time, we’re not wired to cope with that,” he says, while on a plane, harkening the crash in Fearless, maybe alluding to the pandemic and his diagnosis, definitely showing it impossible not to reflect on himself, his own career, such are all the places he's been.

And now here he is, again, this time on our small screens, a different beard and new battle scars, the same rough-hewn grace. With the current shit state of everything around us, how good it feels to be riding next to this sort of graying Yoda. Behind every beautiful thing there's been some kind of pain.

Dylan followed Time Out of Mind with Love and Theft just four years later, and under a microscope, you could say he followed his greatest late-period song, “Not Dark Yet,” with one, somehow, even better: “Mississippi.” Now, with the show picked up for a second season, it is actually still with hope one can wonder: how many rounds does this old man have left?

0 notes

Text

The 38 Essential Milwaukee Restaurants

Eater

“Cliffie, quick. Breath test. What do you smell when I do this?” asks Norm.

“Milwaukee,” Cliff responds.

The punchline from season four of Cheers, which aired in 1985, made a joke of a city that smelled like its breweries and wasn’t known for much else. Today the medium-sized city’s cultural industries work constantly to refute that sentiment, especially in the proudly cosmopolitan food scene. For every sneer that Milwaukee lives in the shadow of its Lake Michigan neighbor, Chicago, someone is serving up quiet, casual defiance with duck confit poutine, Thai barbecue pork noodle soup, chef-ified Big Macs, Andalusian salmorejo, lamb quesabirria, or buttermilk sorbet. For every dig that the city is a staid Rust Belt town of sausage and cheese and beer, there’s Nashville hot chicken sausage, goat cheese curds in chorizo cream sauce, and private chalet dinners at a third-wave craft brewer.

As Milwaukee inches back from the pandemic, and residents bask in the 54-foot Giannis Antetokounmpo mural honoring the Bucks’ 2021 championship, Milwaukee restaurants push forward too, finding new ways and reasons to celebrate a city that, yes, sometimes smells like beer — and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Read more

0 notes

Text

“The Terminal List”

The A.V. Club

“I’m not gonna tell you again. Stay off my list.”

A meme-able bit of brute, reminiscent almost of Harrison Ford’s “get off my plane” from Air Force One, it’s the kind of guttural one-second trailer blip that makes a story’s audience targets and muscle and narrative ambition pretty evident. But it is leveled by Chris Pratt, played with an occasional thousand-yard stare so vacuous, so PTSD-soured it looks like he's either forgotten his lines or is taking a beat to consider how the winding paths of his varied career ended him here. Critic’s Choice comedy player, lovable character actor, Marvel lead, Warner animation lead, Hillsong church member, maybe not Hillsong member, he is “muddled,” he admits, and now Andy from Parks and Rec is the type that can recognize a hitman just by his wraparound shades.

The Terminal List is peak dad prestige TV, a political thriller straight from the songbook of Tom Clancy, with the best-seller list trappings of Lee Child and others so capable of framing bloody revenge tales around characters with names you feel your voice drop an octave when speaking aloud: Jack Ryan, Jack Reacher. In this case we have James Reece, as penned by Jack Carr, a former Navy Seal himself, who holds the distinction that the FAA has mandated no domestic flight can takeoff without at least one middle-aged passenger reading one of his books. He writes muscularly about guys with muscles who call each other "brother" and refer to teammates as "my boys" and discuss objectives in terms like “this motherfucker is ours” and grow lush beards and pick each other up from the airport in Jeeps with lines like “don’t tell me you’re calling a fucking Uber” while a Butt Rock version of "Simple Man" tumbles from the car stereo. There are acronyms, oh so many acronyms — IED, SOP, QRF—tossed knowingly with practiced company man aplomb. If you are not a dad or a knowing dad isn't viewing beside you, it almost feels one might manifest on the couch there simply to explain how it is short for “Quick Reaction Force.”

The archetypal flavor profiles are all here: patriotism, heroism, duty, fellowship, shirtless knife-and-gun fights. Also, there is summertime popcorn appeal, for us armchair schlubs to follow along, be a bit awe-inspired by those in a noble-ish trade, to pay witness to the high purpose of communal badassery.

The action opens with a Seal Team Seven job gone awry. An ambush turns into a 15-minute bloodbath. Hurried whispers of “access points” and "trip wires" lead to a bloody cavalcade of yelling and grunts and fire and wounds and neon orange lines emanating from machine guns donned by men wearing tactical gear and night vision-type contraptions leftists will find themselves shaking their heads disapprovingly of, thinking, “our taxes pay for that?”

By the end it all just looks like a lot to clean up. Postured explanations are levied at disbelieving superiors and investigators: "that's not how it went down." To kick it all off we get an opening verse from the bible. There is more than a hint of red state chest thump—a suspect is chided for drinking “light” beer, somehow there’s a Bryson DeChambeau cameo. Also in the mix are Taylor Kitsch as Ben, an incorrigible good-natured bad influence buddy we know is like a brother because he says “I am your brother.” And Constance Wu plays Katie, a war journalist who only cares about the truth. You know because she says, “all I care about is the truth.” Jeanne Tripplehorn is the Secretary of Defense, a whole cloth TV land politician, obvious because she speaks of "leaving things better than I found them."

The List mostly pops with the nuance of an M-16. From the jump the feel is of a bloody, predictable, testosterone-charged romp making occasional detours toward melancholia. Afterall, following such an open there are funerals to tend to. And though he’s given chances to opt out, Reece stands there, stoic in shades and Navy formals, letting you know these lips don’t quiver. There is a deeply human story here, as he deals with memory confusion, untrustworthy flashbacks, general fuzziness, headaches. A doctor flippantly discusses concussion “repercussions” like the Seals were a late-80’s NFL team. Hints of sadness creep in, a bit of pathos, almost—we don’t really get a picture of who those guys in those caskets were, but, well, they were co-workers. It really feels like a relief when Pratt’s personality, that easy neighborly goof charm, briefly emerges with a bucatini joke halfway through the third episode. There are such moments, fleeting, off-ramps that might allow an approach to contemporary post-war literature like Nico Walker’s “Cherry,” with its dark absurdist poetry of military pursuit; or some vibes of the devastating portrait of PTSD in the 2018 film “Leave No Trace.”

But it’s really about the procedure of uncovering and the business of revenge. “Answers or blood?” as Ben says. It starts with a chemist outside of Aleppo, the Seals’ original target, and the first clue in Reece’s late-night brow-furrowed Google searches, operated while popping pills and bottles of beer. It’s hard not to picture Burt Macklin. But hunkered in his man-of-war cave in Coronado, the show and actor seem to fancy themselves a kind of True Detective (an aesthetic from which the opening credits borrow generously). There is a brooding but bent machismo, with such fist-clenched will it feels on the verge of a boxing movie training montage. Reece begins on his odyssey (“this is personal”), toward varying levels of military contract-type baddies, some with offices and lairs absurdly fit for a Bond villain. Here is an altruistic man on fire, with, yes, a unique set of skills, the kind who knows when “we need to get off the grid,” or how to keep your cell phone from acting as a tracking device, increasingly alone, further alienated. Carr seems to ask: who can you trust but your gun? Another acronym, LLTB, or, “Long Live The Brotherhood,” is engraved on one said piece, and you know most of what he is getting at.

As we are confronted, if you can stand to look at all at the daily news, by a circle of abject cowardice and failure of men with guns, who stood pat and frozen and scared or indifferent to a opportunity for righteous duty, right there in front of them, there is a certain catharsis in viewing even fictional heroic violence. Reece packs his bags, his passports,checks a rifle for readiness, takes a pair of hand axes off the wall, and there is an expectant feel of pregame. It is a comfortable groove, a thinking man’s thriller, neither too thinky nor too thrilling. But damn if it doesn’t feel a bit invigorating to go down the dark hallways of this world of men of action, and think, yeah, this motherfucker is ours.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“The Old Man”

The A.V. Club

There is an old storytelling rule, that when it comes to books or movies, nobody poops. A bathroom trip is a violation of Chekhov's Gun principle, wherein all details must contribute to the overall narrative. Also, nobody wants to see that. The Old Man opens with Jeff Bridges’ character going to relieve himself not once, but three times throughout a single night. He's an old man, after all, as the show keeps reminding us. At one point an assailant says “fuck you, old man” in the middle of a knife fight, just moments after another derides “getting shook by a senior citizen.” The indignity almost seems cruel, given Bridges recent personal history: an extended battle with COVID-19 while on chemotherapy for lymphoma left him “pretty close to dying” in 2021. (Production was halted at the start of the pandemic and then again after Bridges’ diagnosis).

Or, it might seem cruel, if not for the 72-year-old’s never-erring aura of Dude-like amused detachment, an ability to keep the huffs and shuffle of years easy, with the aged gravitas of a character in a Tom Waits song about to tell you wistfully about all the cars he's had in his life. In fact it looks like Bridges borrowed Waits’ beard from The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. It is well fit for the weathered weight of the character, one who gravelly grumbles through dad jokes with the doctor, dad jokes with a waitress over reading spectacles, dad jokes of an “ailment contest” on a first date. He has the kind of old-timer grace that lets him find the perfect Robert Plant banger on the radio when his date can't get the bluetooth to work.

But Dan Chase is not your father's father. A former CIA operative, his slowly degenerating serenity in Connecticut is blown apart by a midnight hitman, one who Chase is alerted to not by SimpliSafe or ADT, of course, but by a DIY alarm of empty dog food cans on a string. Like that his cover is crumpled and he’s on the run, from his former bosses, from his past, relying on old skills despite being told “you have no idea how different the game is than the last time you played.” Also: “you aren’t the guy you remember.” It is a plot so entrenched in the present day Liam Neeson oeuvre there may be royalties due. There's even a threatened daughter, brought into peril precisely because of Chase's unique set of skills. He is a man comfortable with unsettling fits of incredible and explosive violence, natural-looking in intimate hand-to-hand combat shots so brutal and relentless it might make pacifists wonder: what is that, exactly, that CIA guys learn? Are they schooled on Steven Seagal flicks?

The premise all feels like the stuff of a slick Soderbergh-esque 90-minute indie, a kind of subdued spy thriller of stoicism and pacing, or something in the vein of the George Clooney vehicle “The American.” A stylish feel is furthered from the jump by smart opening credits, a thoughtfully ruminating score, continuously deep attention to framing, an A-list cast. Yet the backstory begins to feel padded by episode two, talk turns to “Langley,” as if that place were an entity itself, and the show begins to run against the tropes of Tom Clancy. Expensive suits pass each other official-looking manilla folders, furrowing brows, doing the serious business of bureaucracy under the guise of protecting American freedom, or something.

But it’s still a story most concerned with the past, with its relentless chase, that unending undertow. Flashbacks and exposition-filling phone conversations and voicemails increasingly come into play, often too-neatly filling in narrative gaps, sometimes leading to Shakespeareaean soliloquies from Chase’s daughter that sound nothing at all like any 30-something talking to her father. It’s also a ghost story in a less metaphoric way, as Chase’s deceased wife, Abbey, drops by as a specter chilling enough to feel almost like a character in an entirely different show. John Lithgow plays Harold Harper, an FBI honcho, former CIA honcho, with the pinched and condescending face of a high school chemistry teacher, bereft over the death of his son, haunted by sordid entanglements with Chase in the mountains of Afghanistan and the dustbin of American international policy. Alia Shawkat, maybe miscast—it’s hard to see Cousin Maeby aligning herself with The Man—plays his tenacious and tenaciously loyal understudy. Amy Brenneman plays Zoe, the show’s quiet but sturdy conscience, a reluctant landlord of Chase along his run who becomes romantically, and otherwise, entangled with his trajectory. This course leads to tangents west and points unknown, toward increasingly jarring whiplash snaps in the tension.

But The Old Man, like an old man, is best when it ambles, tracking a brooding, contemplative pace. Compared to backstory filler, where a young Chase, played admirably enough by Bill Heck, ratchets up the blood in the Jack Ryan territory, it can’t help but feel good to get back to spending time with Bridges. Especially in the quiet moments of chopping onions or making bulletproof coffee or slowly backing off to give space to someone he has intimidated, or talking, as he often does, to his brilliant and brutal rottweilers, Dave and Carol. There is something redemptive in watching him drum his fingers with wry satisfaction as he pushes a plate of food across a counter. It is almost like a feeling of hope to bear witness to another one, another friend, that made it through something awful, ghastly, not to someplace better, necessarily, but into this present unholy era of violence and unease. It is no tiny miracle to see that someone doing the human business of arriving, everyday, full of reflection. Sometimes there’s a man, acting on the work of life despite it all.

The year after he broke out in 1971’s “The Last Picture Show,” Bridges co-starred with Stacy Keach in John Huston’s vastly underrated “Fat City.” The last scene finds the two boxers, at opposite ends of their careers, both still beaten up, beaten down, bruised and beleaguered, huddled and hunkered and almost desperate together over cups of cafeteria coffee. Keach’s character sympathetically considers an elderly waiter: “You think he was ever young once?” Bridges takes a perfect beat before replying: “No.”

0 notes

Text

Wioletta’s Taste of Poland

Shepherd Express

For a city with the fourth highest Polish American population in the country, a town where I know of not one, but three unrelated people with the surname “Lazarski,” Milwaukee has a serious pierogi shortage. Look no further than Wioletta’s auspicious opening weekend earlier this month, where there was a run on Polska market fare like it was toilet paper in March ‘20. They sold 1500 pounds of meat in three days. Not to mention everything else. Walking in on day four of business operations I was met by apologies, empty shelves, and reduced to pity buying nothing but some cream-filled Caramelo-like chocolate indulgences that made me reschedule a looming dentist appointment so that I could get in one more week of scrubbing. Apparently having one Polish restaurant, Polonez, and one Polish deli, A&J, isn’t cutting it by way of demand.