25 y/o, he/him, u/Tribbetherium on reddit's r/SpeculativeEvolution. General evolutionary biology nerd. Original projects: "Hamster's Paradise", "Planet of the Pseudosnakes", collaborative "Delphinus Archipelago" with @alphynix, and untitled Tullimonstrum seed world, as well as fanart of Sheather888's "Serina".

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

IT'S SPECTEMBER AGAIN!

I know the Hamster's Paradise "alternate what if's" won out in the poll but I've had some art in the works on something else for a while. (Those will follow soon, I promise!)

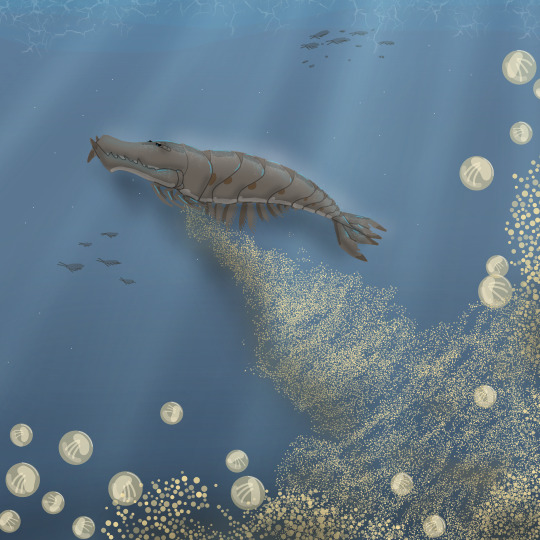

So here's a piece on "The Delphinus Archipelago", an old collab project with @alphynix featuring land dolphins!

There's been two iterations of the project:

- The original post, and its follow-up

- The new ones by Alphynix for Spectember 2020, the first one with the evolutionary history and a newer bunch of them known as rhamphins.

The two are probably not canon to each other but I just drew their species together anyway. I suppose that sort of diversity would have to require more than an archipelago but rather a continent: or perhaps have a mass extinction wipe out all land tetrapods for cetaceans to be the next best option. Or it could just be a dolphin seed world, who knows...

▪︎▪︎▪︎▪︎▪︎▪︎▪︎▪︎▪︎▪︎

#spectember 2025#spectember#the delphinus archipelago#land dolphins#speculative zoology#speculative biology#speculative evolution#spec evo

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm a little busy for September so I won't be able to do all of them for the month, though the ones not picked might still be worked on at a later date.

#tribb speaks#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#spectember#spectember 2025

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The dioecious (separate-sexed) arrangement is very common, if not the majority, among animals, but among plants, it is a comparative rarity, with the vast majority of flora being monoecious (dual-sexed), with either both male and female organs being present on the same flower, or on separate male and female flowers growing on the same plant. But, as with every rule in nature, there are exceptions: as is the case of some plants that exhibit behaviors one might more expect from animals.

In the windswept savannahs of equatorial Gestaltia, a common sight are gatherings of small, shrub-like citrus descendants, clustered together in groups of up to several dozen. But, at seemingly regular intervals, spaced far between, a single lone specimen stands out among the others: twice as tall as its neighbors, and reaching up to nine feet in height. While surrounding smaller trees bear fruit, ovoid, yellow grapefruit-like ones, these lone tall trees sport none, instead adorned by white flowers sporting long, pollen-laden central stalks. These giants of their kind stand firm in the centers of each fruiting grove, with a tangled mass of roots, snaking across the undergrowth, all traceable as belonging to the larger tree. These are gold-anthered stagroots (Dioeciocitron dimorphis): and this unusual appearance and arrangement is no mere coincidence--the groves are a harem of small females, protected by a large dominant male.

Such a statement might seem absurd, for after all, these are plants: and the idea of such mating arrangements sound something more in the line of animals, who court mates and defend them from rival males in dynamic, animated displays. Yet in their own silent, botanical way, nearly invisible to the naked eye, these dominant "bucks" stand vigil over their herd of "does", viciously protecting them from interlopers and claiming a large territory for themselves, fighting for the opportunity of breeding with the multiple females they share a territory with.

Such an unusual arrangement first came about when these dwarf trees first came to live in the windy savannahs, from seeds that dispersed from far away in the droppings of flying ratbats and pterodents. Strong air currents made it difficult for many flying insects, potential pollinators, to fly higher than a foot or two, so these unusual species instead took advantage of the weather and instead developed the ability to be pollinated by abundant and long-traveling wind currents sweeping through the savannah: male flowers being adorned with long, golden-yellow anthers that catch into the wind, spreading their powdery pollen far and wide, and female ones possessing conical structures with sticky surfaces that catch the pollen produced by male flowers that can then fertilize their ovaries and trigger the female flower's transformation into a fruit.

Remarkably, fertilized seeds acquire a set of genes from both the mother and the father that, depending on how they are arranged, affect how the plant grows, behaves, and interacts with other plants: functioning similarly to the sex chromosomes of animals. As such, as a seed takes root and begins to sprout in to a sapling, its sex is already predetermined: if the seed is a female, then it will grow at a rather slow rate and reach maximum height at just four to five feet. Its roots bore deeper into the soil without spreading sideways much, and it typically ignores the presence of most other plants, including other females of its own species.

But should the seed be a male, it exhibits a completely different set of what can almost be called "behaviors", despite their lack of a nervous system or any means of conscious intent in the way an animal might. Relying on "tropisms", autonomic responses to environmental signals, these male seeds quickly get to work establishing themselves, growing faster than a female and sending down a deep main root to anchor it in place. Once it reaches a sufficient size, then it quickly gets to work dominating its territory: around a large radius of up to a hundred meters or so, it sends lateral roots, closer to the surface, which feel their way about in search of the roots of other members of its species, attracted by chemical signals.

Should it find the roots of a nearby female, it will then be stimulated to share its accessory root system with its partner: a network of tiny rootlets, growing from the tips, surround the female's roots, as if gently enevloping it in a protective embrace. With this link, the male plant can share water and nutrients to the female, even releasing chemical signals into the soil that attract the roots of nearby females, advertising its quality as a protector and provider for them in a form of chemical courtship. Through this root system, the male plant can also use pheromones to signal to all the females connected to it to bloom simultaneously, allowing that the male's pollen is most likely to fertilize their flowers and enable them to bear fruit and produce viable seeds fathered by the male. Tropisms sensitive to the movement of wind guide its blooming patterns, increasing its flowering on the direction the wind blows the strongest, to maximize the odds of nearby females being pollinated.

But if the root encounters that of another male, a vicious battle ensues--at least, on a microscopic scale. Small rootlets grow out of the root tips, but this time, they latch on to the root of the rival male, and attempt to siphon them of nutrients and water, draining them dry. If similarly attacked themselves, the roots can coil defensively in an attempt to constrict the attacking rootlets and impede their flow of tissue fluids to choke or repel them. The roots of males fight fiercely, spreading out in a radius comparatively massive compared to a female's, and attacking any male roots located inside their territory, with the strongest male choking out, entangling, and draining its rivals dry, and killing off all competition within its home territory. The struggle for dominion is fierce, and only one male can conquer a territory: any male seedling that sprouts within the territory must grow quickly and fight with the dominant male in the hopes of eventually deposing them in order to survive, or else die trying, for the ruler's roots will show them no mercy. Around the area of the territory, any other male challengers will seemingly wilt for no reason, when viewed from the surface, but under the ground, an unseen conflict unfolds claiming the yellowing, withering male trees as its casualties.

Thus, while female stagroots grow together in close proximity and tolerant of one another, only one male can live and grow in the radius of one territory, any others attacked or killed by the most dominant one in its quest for supremacy. This way, a male tree, being sessile as are all plants, can assure the proximity of females that will recieve its pollen, bear fruit, and spread seeds that will be the male's genetic successors without the risk of a rival male pushing its way in to father some seeds in secret.

Interactions like these are a stark reminder that plants, too are not merely vegetative growths acting as backgrounds for animals, but themselves also fighting fierce battles against one another for survival, domination of their surrounding habitat and the ultimate goal of passing on their genes, albeit at a scale and speed too small, and too slow, as to be barely perceptible. While animals, by a long margin, are the more animated, complex and sophisticated of the two kingdoms, plants are no less alive, with all that definition entails: playing out a drama of their own struggles of life and death beneath the notice of the animal kingdom.

--------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#species profile

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

So it appears my previous post was rather controversial due to the use of the term "hermaphrodite".

The intention was not to draw any connection to the outdated, inaccurate term formerly used to describe intersex people, which are not at all comparable to the very different biology of invertebrates such as gastropods and annelids. The two terms are very different and the application to nonhuman organisms is still widely used, but to err on the side of caution I did some research on alternative terms for organisms with both sets of gonads, that are able to inseminate the eggs of another individual while also producing eggs themselves (again, very different from the human intersex condition which it is not related to). Some have suggested terms such as "gonosimulistic" and "cosexed", though it seems currently the most accepted alternate term is "dioecious" (meaning "two-housed", in that the two sets of reproductive organs are housed in two separate organisms) and "monoecious" (meaning "one-housed", in that the same organism houses both sets of gonads in one), so I will be using those terms for now. Again, no offense was intended, it was merely a widely-used term in biology, and while the use toward humans is by any definition offensive, the use in non-human organisms did not seem inappropriate until mentioned otherwise.

Thanks for understanding, because as usual, science marches on. Pluto was once a planet, Tyrannosaurus rex was formerly called Manospondylus gigas. Things that were once commonly known and are scientifically accepted change over time, as do terminologies as we learn more about the world.

Also, during my recent research on the subject it appears that among gastropods it seems only land snails are monoecious while marine snails are dioecious, which throws a whole wrench into the whole Early Rodentocene lore that all terrestrial gastropods on HP-02017 were descended from sea snails that went terrestrial and the skwoids and pescopods being descended from those too. Would it make more sense for terrestrial gastropods to instead have gone aquatic to make the pescopods' monoecious and three-sex system make sense? Some significant invertebrate taxonomy retcons might be in order...

The revised version with the updated terminology can be seen here.

#tribb speaks#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

While notable exceptions exist, the pescopods, active-swimming aquatic gastropods now widely distributed among marine and freshwater habitats in the Temperocene, have far-less defined boundaries and dynamics between their sexes. Their ancestral gastropods similarly possessing both sets of reproductive organs within a single individual, many of their descendants, including their distant relatives the quillnobs, asterisks and skwoids, have since taken unique approaches, such as some developing aggressive copulation rituals where they fight to inseminate the other while avoiding getting inseminated themselves, or others beginning life as one sex and metamorphose into the other, depending on whether their competitive nature would favor a bigger male, thus being protogynous (born female and become male as they mature) , or whether a more fecund approach would favor a bigger female, thus being protandrous (born male and vecoming female as they mature).

The majority of marine pescopods, however, have a unique system of sex determination, depending on whether they are dioecious (having male and female reproductive gonads on separate individuals) or monoecious (having male and female reproductive gonads on the same individual). Thus, most pescopods have three sexes: dioecious male, dioecious female, and monoecious. This increases the chances of finding a suitable mate when they breed: a dioecious male can reproduce with a monoecious or a dioecious female, a dioecious female can reproduce with a monoecious or a dioecious male, and two monoecious individuals can reproduce with each other, as well with a dioecious male and with a dioecious female. Such a system increases the chances of genetic diversity among their offspring, or rebounding back from small, isolated populations, be it survivors of a mass die-off or new pioneers expanding into unoccupied territory.

With different sexes in nature taking on different physical forms, having different reproductive strategies and behaviors, and competing with each other for mates, the addition of this three-sex system further complicates this widespread practice in the pescopods: primarily, in terms of individuals making energetic trade-offs to maximize reproductive success. And in no other species is this more confounding than in the variable reef spadetail (Palapescocochleus multiformis), a small, algae-eating pescopod native to the quillnob reefs of the shallow seas off the coasts of Mesoterra.

The majority of reef spadetails are what is known as the monoecious generalist: drably-colored, intermediately-sized individuals roughly 5 centimeters long, that live in small groups of other members of their mating-type for protection. These generalists, typically, will breed with fellow monoecious generalists, including basically any other member of their small schools, and produce eggs that are laid commensally within the shells of the quillnobs themselves. This practice is of minimal consequence to the quillnobs, but their filtering gill-filaments that push water in and out of their shell helps keep the eggs oxygenated, as well as hiding them well out of the reach of the reef’s many predators.

However, other reef spadetails have taken on more unusual reproductive strategies. Some, growing to sizes of up to 10 centimeters in length, specialize into dioecious females: dedicating their reproductive strategy on producing as many eggs as possible. Known as brooder females, they lay a few eggs in each quillnob shell, but lay them in as many quillnobs as possible: providing them little if any attention but propagating their spawn far and wide in a display of commitment to the r-selection lifestyle. Brooder females are nomadic loners and have no set territory within the quillnob reefs, ranging across large distances to find suitable places to lay their eggs.

In contrast, another dioecious female, the grouper female, focuses on an opposite k-selected strategy: they are gregarious, and seek out other grouper females to stake out a small territory with multiple ideal quillnobs in which to lay their eggs. They are far smaller than brooder females or even monoecious generalists, at about 2-3 centimeters long, and produce only a few eggs each, but their more social behavior and investing more in their young pays off in ensuring a greater percentage of them survive to hatching.

Due to the greater metabolic cost of producing large eggs versus microscopic sperm, some other spadetails specialize into dioecious males instead: no longer producing eggs of their own, they instead try to dedicate themselves to getting to fertilize those of dioecious females or monoecious individuals instead in order to pass on their genes. Some dioecious males, growing to the size of brooder females, become protector males: large, aggressive and territorial males who use their greater size and sharp radula as weapons to fight off intruders. Typically, they become guardians of harems of either grouper females or monoecious generalists, aggressively defending them from the advances of either other protector males, as well as those of another dioecious male morph: the displayer male.

Displayer males, as their name suggests, are bright and colorful, and while attracting and courting either dioecious females or monoecious individuals with their elaborate courtship displays, invest in little else other than their genes, departing once they have mated in search of another mate. While they may seem a less-advantageous mate choice, they find reproductive success nonetheless as their flamboyant colors and flowy fins are genuine indicators of fitness, perhaps even as deliberate handicaps that make them less-agile swimmers and more visible targets: so any such male that survives in spite of it must be a very fit male indeed.

And lastly, there are the miniature monoecious polyphiles, which are the jack-of-all-trades in their chaotic courtship. Ever opportunistic, and able to mate with any of the other types, they will join groups of monoecious generalists or grouper females, mating with both them and the large guardian protector males defending them, as well as accepting the flirtatious advances of colorful displayer males, and also coupulating with transient, passing brooder females if they happen to find them while they are receptive. Their preferences tend to vary depending on local availability and conditions, though, oddly, they show the least amount of interest to fellow monoecious polyphiles, though still mating with them if no other options are available.

Due to this complex arrangement, the variable reef spadetail, functionally, has six sexes: and with it, a greater opportunity to mix-and-match their couplings when they breed. Monoecious generalists will most often mate with other monoecious generalists as well as protector males, and less commonly with visiting displayer males who bypass the protector males' guard. Grouper females prefer to mate with protector males, both being territorial, while brooder females prefer to mate with displayer males, both being nomadic. Protector males have an increased preference to mate with grouper females than monoecious generalists, as they are likelier to father their young instead of each others’, displayer males prefer to mate with monoecious generalists over grouper females, as there are less competition with aggressive protector males, protector males and equally-large brooder females rarely mate due to a conflict between the territorial protector male and the nomadic brooder female’s lifestyles, and monoecious polyphiles are almost-equally willing to mate with anybody.

Regardless of the complex affairs of whichever their parents were, the offspring hatch from their eggs within two to three weeks, and spend a few days hiding within the shells of their quillnob host: first absorbing their remnant yolk stores and then partaking of scraps of food that the quillnob filters out of the water. Once they are about a week old, they leave the quillnob shell and begin roaming about the reef able to fend for themselves, scraping off algae from the surfaces of the sunlit reefs with their radulas and playing an ecological part in preventing its overgrowth. For most of their early lives, they are most similar to monoecious generalists, though grouper females and monoecious polyphiles, being smaller, are early bloomers, reaching sexual maturity at just a few months of age, while displayer males and monoecious generalists take somewhat longer, and the largest sexes, the protector males and brooder females, taking up to a year to mature. Whichever ones they mature into are determined by a wide array of factors, such as genetic, hormonal, nutritional, environmental and social cues, including the sex ratios of other members of their species in their vicinity. Once mature, they permanently remain whichever of the six sexes they specialized as: ready to take their chances playing in a peculiar mating game unlike any other.

--------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#art one shot#species profile

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

While notable exceptions exist, the pescopods, active-swimming aquatic gastropods now widely distributed among marine and freshwater habitats in the Temperocene, are hermaphroditic, having far-less defined boundaries between their sexes. With the ancestral gastropods being similarly hermaphroditic, many of their descendants, including their distant relatives the quillnobs, asterisks and skwoids, have since taken unique approaches, such as some developing aggressive copulation rituals where they fight to inseminate the other while avoiding getting inseminated themselves, or others being sequential hermaphrodites where they begin life as one sex and metamorphose into the other, depending on whether their competitive nature would favor a bigger male, or whether a more fecund approach would favor a bigger female.

The majority of marine pescopods, however, have a unique system of three sexes: obligate males, obligate females, and hermaphrodites. This increases the chances of finding a suitable mate when they breed: a male can reproduce with a hermaphrodite or a female, a female can reproduce with a hermaphrodite or a male, and two hermaphtodites can reproduce with each other, as well with a male and with a female. Such a system increases the chances of genetic diversity among their offspring, or rebounding back from small, isolated populations, be it survivors of a mass die-off or new pioneers expanding into unoccupied territory.

With different sexes in nature taking on different physical forms, having different reproductive strategies and behaviors, and competing with each other for mates, the addition of this three-sex system further complicates this widespread practice in the pescopods: primarily, in terms of individuals making energetic trade-offs to maximize reproductive success. And in no other species is this more confounding than in the variable reef spadetail (Palapescocochleus multiformis), a small, algae-eating pescopod native to the quillnob reefs of the shallow seas off the coasts of Mesoterra.

The majority of reef spadetails are what is known as the generalized hermaphrodite: drably-colored, intermediately-sized individuals roughly 5 centimeters long, that live in small groups of other members of their kind, for protection. These generalized hermaphrodites, typically, will breed with fellow generalized hermaphrodites, including basically any other member of their small schools, and produce eggs that are laid commensally within the shells of the quillnobs themselves. This practice is harmless to the quillnobs, but their filtering gill-filaments that push water in and out of their shell helps keep the eggs oxygenated, as well as hiding them well out of the reach of the reef's many predators.

However, other reef spadetails have taken on more unusual reproductive strategies. Some, growing to sizes of up to 10 centimeters in length, specialize into females: dedicating their reproductive strategy on producing as many eggs as possible. Known as brooder females, they lay a few eggs in each quillnob shell, but lay them in as many quillnobs as possible: providing them little if any attention but propagating their spawn far and wide in a display of commitment to the r-selection lifestyle. Brooder females are nomadic loners and have no set territory within the quillnob reefs, ranging across large distances to find suitable places to lay their eggs.

In contrast, another obligate female, the grouper female, focuses on an opposite k-selected strategy: they are gregarious, and seek out other grouper females to stake out a small territory with multiple ideal quillnobs in which to lay their eggs. They are far smaller than brooder females or even generalized hermaphrodites, at about 2-3 centimeters long, and produce only a few eggs each, but their more social behavior and investing more in their young pays off in ensuring a greater percentage of them survive to hatching.

Due to the greater metabolic cost of producing large eggs versus microscopic sperm, some other spadetails specialize into males instead: no longer producing eggs of their own, they instead try to dedicate themselves to getting to fertilize those of females or hermaphrodites instead in order to pass on their genes. Some males, growing to the size of brooder females, become protector males: large, aggressive and territorial males who use their greater size and sharp radula as weapons to fight off intruders. Typically, they become guardians of harems of either grouper females or generalized hermaphrodites, aggressively defending them from from the advances of either other protector males, as well as those of another male morph: the displayer male.

Displayer males, as their name suggests, are bright and colorful, and while attracting and courting either females or hermaphrodites with their elaborate courtship displays, invest in little else other than their genes, departing once they have mated in search of another mate. While they may seem a less-advantageous mate choice, they find reproductive success nonetheless as their flamboyant colors and flowy fins are genuine indicators of fitness, perhaps even as deliberate handicaps that make them less-agile swimmers and more visible targets: so any such male that survives in spite of it must be a very fit male indeed.

And lastly, there are the small-morph hermaphrodites, which are the jack-of-all-trades in their chaotic courtship. Ever opportunistic, and able to mate with any of the other types, they will join groups of generalized hermaphrodites or grouper females, mating with both them and the large guardian protector males defending them, as well as accepting the flirtatious advances of colorful displayer males, and also coupulating with transient, passing brooder females if they happen to find them while they are receptive. Their preferences tend to vary depending on local availability and conditions, though, oddly, they show the least amount of interest to fellow small-morph hermaphrodites, though still mating with them if no other options are available.

Due to this complex arrangement, the variable reef spadetail, functionally, has six sexes: and with it, a greater opportunity to mix-and-match their couplings when they breed. Generalized hermaphrodites will most often mate with other generalized hermaphrodites as well as protector males, and less commonly with visiting displayer males. Grouper females prefer to mate with protector males, being territorial, while brooder females prefer to mate with displayer males, being nomadic. Protector males have an increased preference to mate with grouper females than generalized hermaphrodites, as they are likelier to father their young instead of each others', displayer males prefer to mate with generalized hermaphrodites over grouper females, as there are less competition with aggressive protector males, protector males and equally-large brooder females rarely mate due to a conflict between the territorial protector male and the nomadic brooder female's lifestyles, and small-morph hermaphrodites are almost-equally willing to mate with anybody.

Regardless of the complex affairs of whichever their parents were, the offspring hatch from their eggs within two to three weeks, and spend a few days hiding within the shells of their quillnob host: first absorbing their remnant yolk stores and then partaking of scraps of food that the quillnob filters out of the water. Once they are about a week old, they leave the quillnob shell and begin roaming about the reef able to fend for themselves, scraping off algae from the surfaces of the sunlit reefs with their radulas and playing an ecological part in preventing its overgrowth. For most of their early lives, they are most similar to generalized hermaphrodites, though grouper females and small-morph hermaphrodites, being smaller, are early bloomers, reaching sexual maturity at just a few months of age, while displayer males and generalized hermaphrodites take somewhat longer, and the largest sexes, the protector males and brooder females, taking up to a year to mature. Whichever ones they mature into are determined by a wide array of factors, such as genetic, hormonal, nutritional, environmental and social cues, including the sex ratios of other members of their species in their vicinity. Once mature, they permanently remain whichever of the six sexes they specialized as: ready to take their chances playing in a peculiar mating game unlike any other.

-------

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Nooo! Bad! Taste very bad not like!"

"Bad for verysmall-sickbugs. Good for you."

Unsurprisingly, with their level of sophistication, the existence of micro-organisms were all but unknown to the calliducyons. Yet their harmful effects were not, especially to the northhounds, and the vulpins in particular. As they had observed that certain plants, especially bitter-tasting bleedweed, were avoided by leaf-eating insects, and that certain ailments and their symptoms were relieved by said herbs, it has, in turn, led to a widespread and pervasive belief that diseases and illnesses were actually caused by insects: insects too small to be seen, a belief reinforced by their familiarity to visible pest insects that infest their coat as external parasites. In a very loose way, they are not all too inaccurate.

----------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#art one shot#the calliducyon saga

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remastered Shroomor Has It: A Lingering Legacy of A Darker Past!

Original:

Remastered:

#art remaster#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adults of the pillaging skyscound, as only the young unfledged pup was shown in the original post.

#species profile#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Returning from a long foraging trip, a female bare-snouted wavewing (Procellapteryx rhynchorrhinus), a species of relatively smaller coastal wandergander, arrives onto her rocky cliffside nest, where she is greeted by an enormously large pup already her own size, nudging under her wing and attempting to nurse. But this endearing-looking scene harbors a more sinister secret, for the pup is not her own: it is an impostor, a pup of a pillaging skyscound (Aerolatrocinor imperator), a larger species of seagoing pterodent that is the scourge of all its kin: be it from harrassing other oceanic pterodents or ratbats as well midair in order to force them to drop their catch for them to steal, or attacking their nests while the parents are away to prey upon the vulnerable pups, still unable to fly.

At some point, however, some female skyscounds, snatching the young of other pterodents, dropped off their own newborn pups in the place of the one they had preyed upon. The impostor pup, covering itself in the shed downy fur that lines the nest, ends up taking upon the scent of the original occupant and being accepted as their own: thus freeing the mother skyscound of parental duties and giving her more opportunities to hunt and breed while expending less energy. While such exploitative nesting behaviors are easier to pull off in oviparous animals, the long foraging trips of parent wanderganders, often lasting a day or more, gives the skyscound, livebearing like all hamsters, a larger window of opportunity to swap an unlucky pup for her own. However, as all evolutionary arms races go, it is likely that, over time, the victimized species will develop better means to safekeep their nests or detect and eject intruders. But for now, this cunning scheme is enough to fool enough wavewings to be a viable strategy: unwitting babysitters tricked into raising others' young at the loss of their own.'

------------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#art one shot

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

The tropical rainforests of equatorial Gestaltia are easily one of the most biodiverse ecosystems of the Middle Temperocene harboring hundreds or thousands of different species. Here, in warm, humid regions with plenty of rainfall all year round and with no dry season, a wide array of plant and animal life, in many ways illustrating the progress of the seeded life on the planet, thrive in great abundance, the plant life nourished by the plentiful sun and rain, and the animals in turn nourished by the plants from the bottom of the food web up.

This equatorial biome, rich with life, itself plays a significant role in regulating the climate in the tropical regions of the planet, especially during the warmer climate of the Temperocene. Millions of individual plants, excreting moisture through transpiration, create a humid atmosphere that contributes to cloud formation and rainfall, and carbon dioxide sequestered by plant life reduces the carbon present in the atmosphere. In many ways, the rainforest itself acts as a buffer to more sudden changes in the climate, helping keep the local weather patterns stable.

Despite an abundance of trees, especially ones descended from stonefruit trees, due to the leaching from the heavy and constant rainfall, the soils of the rainforests are, paradoxically, very poor in nutrients: further exacerbated by local flora evolving to absorb as much nutrients as they can as quickly as possible before it washes away. On the forest floor, where light is poor and shaded by the forest canopy, smaller plants have adapted to thrive in low-light conditions. These include descendants of clovers, such as forest cloverferns (Polytrifolium spp.) and cloverbushes (Magnatrifolium spp.), growing close to ground level and having dark green leaves maximizing the amount of chlorophyll to increase their rate of light absorption and carbon fixation even in shaded environments. Others, herbaceous cabbage descendants such as the broadleaf brassica (Brassiplatus spp.) have wider leaves for greater surface area, and have a slower rate of growth than most other plants of the forest floor. With a large energy-storing root system, the broadleaf can go dormant when conditions turn unfavorable, only resuming activity when its environment is conducive to its growth once again. This strategy has even been adopted by some trees, such as the dwarf cherryberry (Diminutoprunus spp.), a species of stonefruit tree that has dwarfed itself to miniature proportions and adapted to poor-light conditions instead of competing with the bigger trees for resources, forming part of the understory of the rainforest at heights of only 4-6 feet tall at most.

Many trees of the competitive, resource-poor soils develop wide, criscrossing roots close to the surface as opposed to deep-boring taproots, in order to cover a larger surface area with which to collect water and nutrients from the surface of the soil. And many have help from some very unexpected assistants: symbiotic shroomors. Rootglobs (Theriotoma spp.) are one common example: neither plant nor fungus, they are in fact animals, or parts of them. Specifically, they descended from transmissible tumors of hamster ancestors that have become free-living, and their ability to invade and absorb nutrients from their hosts made them efficient decomposers and, eventually, tree symbionts. Rootglobs, growing on the buttress roots of trees, extend the tree's reach for water and nutrients with their web-shaped, slime mold-like growth, and are in turn nourished by the trees' sugars in their sap. As animal tissue, they can also synthesize proteins, nitrogen compounds and amino acids that they share with the trees, helping them contribute to their host's survival in a display of mutualism.

Not all shroomors are helpful to the trees, however. Woodtongues (Lingusarcophyton spp.), growing on the bark of many trees, are parasites, leeching off the trees' nutrients and feeding on rotting wood, eventually producing tongue-shaped growths that emerge from the wood, whose sporelike "founder cells" can wash off by rain and be carried to the roots of other trees. Fortunately, the abundance of the woodtongue has brought about another organism to keep it in check: woodtongue wasps (Linguluphilus spp.), whose females lay their eggs on the "tongues" as a nutritious food source for their larvae. The voracious grubs feast eagerly on the fruiting bodies, curbing their growth and preventing them from infecting too many healthy trees and overrunning their root systems.

The forest floor teems with many other invertebrates as well. Leaflice (Folisopoda spp.) and springhoppers (Caudisaltus spp.), descendants of woodlice and springtails originally introduced in the seeding phase as detritivores, now are just a few of a wide array of genera and species including scavengers, herbivores, fungivores, and even insectivorous predators among their ranks, filling the niches various small arthropods would in Earth's ecosystems. Less-efficient at retaining moisture than true insects, these plentiful "bugs" thrive in the damp, dimly-lit forest floor where they are safe from dessication, while true insects have sole dominion over drier biomes.

One true insect that does prefer the humidity, however, are the mush marchers (Migratermes mobilicasa). Unusually among termites, who prefer the darkness within tunnels underground and inside wood, the mush marchers travel along in lines in the open, shaded from heat and light on the forest floor and undergrowth. Foraging parties, flanked by big-headed soldiers, scour the leaf litter for edible material to chew up, proccess, and use to nourish their fungus gardens. Here, they again differ from other termites in an unconventional way: these gardens, knotted hollow masses of fungi and processed plant matter, double as mobile homes housing their reproductives, eggs and nymphs. This is advantageoous during seasonal floods, as they are able to move their homes to higher ground, a feat not possible with a fixed, permanent home.

All these abundant forest-floor invertebrates attract the attention of a remarkable little hunter unlike any the planet had seen until quite recently: the wooded squoad (Amphibiocochleoteuthis anuroides), a species of a group of skwoids that, in a first of their clade, have adapted to living on land, taking advantage of the vacant niche of small amphibians to thrive in a diverse array of a hundred or more species. Their harpoon-like radula, inherited from their marine skwoid ancestors, now possess a barbed tip for flicking out to catch small prey, and their six sucker-lined tentacles have become elastic springs, shortening and extending forcefully to launch the squoads forward in jumps that can be up to five times its body length. Despite their new terrestrial lifestyle, however, squoads are still dependent on moisture due to their aquatic eggs and permeable skins, making the damp forest floor of the rainforest an ideal habitat for them to thrive.

Above the forest floor, the understory of the rainforest is comprised of medium-height plants, adapting to survive with somewhat less light blocked by the canopy. Aside from dwarfed trees, other plants of this zone include feathery palmleaf (Plumobrassica spp.), another cabbage descendant but now specialized to have enormous, pen-shaped leaves to maximize the surface area for light absorption in their shaded environment.

High in the canopy, other plants partake of the race for sunlight and water by growing directly on the branches of the trees themselves. Known as epiphytes, these arboreal plants are commensal to the trees themselves, neither helping nor harming them, though if allowed to overgrow without being regularly fed upon by animals, they may end up smothering a tree. Among this are other clover descendants, such as jungle clovervines (Vinotrifolium spp.) whose long herbaceous stems clamber up tree trunks with the help of stolons that grow away from the root system to produce a secondary root system, each one acting as an anchor onto the trees' bark. Others are grasses, such as canopy firebloom (Arbopyrogramen spp.), which warns would-be consumers of its irritating chemical defenses with bright red-orange coloration, and arboreal leaferpool (Arbaquafolium spp.) which collect rainwater in their leaves and stems, which become ideal nurseries and micro-habitats for a host of different organisms. Some are even not plants at all, but lichens: a union of algae and fungus, such as beardmoss (Barbamuscus spp.), which hang down from the undersides of tree limbs and branches.

One unusual plant, the white ghostroot (Phantasmofolium spp.) has taken this relationship to the tree to a greater extreme. It now lives entirely inside the tree, its stems and branches snaking through the tree's tissues just underneath its bark, and sending deep-boring roots into the tree's xylem and phloem to siphon water and sugars from its host. However, it restricts its growth to avoid over-burdening the tree it depends on to survive: such to the point that if any of its stems and roots touch those of a separate ghostroot also attempting to grow on the same tree its roots will bore into its rival's tissues in an attempt to drain it dry and eliminate competition that threatens the survival of its host tree. The only time it ever emerges to the surface is to bloom, in which case a pale, white stem emerges from the bark and produces a cluster of small whitish-blue flowers, opening at night and releasing an enticing aroma just in time to attract its specialized pollinator, the ghostroot wasp (Phantasmophilus noctis).

By far, however, the majority of invertebrate life in the trees are ants: ever successful on their transported planet as they were back on their homeworld, they diversified into a vast assemblage of thousands upon thousands of species, many virtually identical to Earthly ants, but a few novel new standouts have emerged. In the Gestaltian rainforest, one such family of ants are the grubgun ants: unique among ant species in having a neotenic larval caste that never matures into an adult ant at all: instead remaining as an oversized larva whose silk secretions are utilized by other, matured ants as working tools for nest-building and defense. By giving up all other metabolic functions, these permanent larvae are able to quickly secrete large quantities of their silk, and are carried about by their metamorphosed sisters and wielded accordingly as they are needed. Goliath grubgun ants (Megalopaedomyrmex armadus), the largest of the grubgun species at about an inch in length, have two such castes of neotenous larvae: a smaller caste, carried by minor workers, that secretes silk for use in building nests out of leaves, twigs and dirt up in the treetops, and a larger caste, wielded by bigger major workers, that secrete large quantities of silk in long streams, acting as living glue guns that the majors use in battle to ensnare other invading ants. These opponents oftentimes include a smaller species of grubgun ant, the leaping grubgun ant (Saltopaedomyrmex minimus) which possess long hind legs for jumping long distances from branch to branch, while carrying a neotenous larva that secretes a "bungee cord" of silk as its carrier leaps across gaps. This way, they are able to quickly form silk bridges connecting nearby trees, allowing them to quickly send raiding parties to attack other ant colonies and plunder their resources.

Meanwhile, on the leaves of feathery palmleaf, a small, inconspicuous insect feeds upon the nutritious sap: the dairy oxgrub (Bovilarvinus spp.). Though they do not look the part, they are actually descended from lepidopterans: specifically, they belong to a clade known as the Hemimetamorpha or "half-changers", which develop piercing and sucking mouthparts but remain larval and wormlike even as adults. These sip large quantities of sap from leaves, but as sap is primarily sugar and water, they excrete most of these excess as concentrated, sugary honeydew: one that attracts the attention of a resourceful ant species, known as the yellow rancher ant (Agricumyrmex xanthus). These dutiful farmers protect the oxgrubs and herd them almost like livestock, tending to them, protecting them from predators, transporting them from one leaf to another to richer "pastures", and milking them of their sweet honeydew.

This idyllic lifestyle does not come uncontested, however: the rainforest understory is also home to the ranchers' greatest enemy: the white-headed reaper ant (Kleptomyrmex cephalbus). Measuring an inch long and with enormous, serrated mandibles, they are the bane of other ant species. They often prey upon leaping grubgun ants, seizing them in their tweezer-like mandibles and holding them up into the air to prevent them from freeing themselves with a powerful kick of their hind legs. But they are also the deadliest rival of the ranchers and their "cattle", raiding their herds like insect rustlers, making away not only with their oxgrubs but their larvae and pupae as well. The reaper ants kidnap the young of other ants and essentially enslave them, as their massive jaws, while terrifyingly efficient in warfare, leave them unable to chew their own food: and must be fed liquid regurgitated food by attendants of assimilated species with smaller and more manageable jaws.

To defend themselves and their herds, some rancher ants, some have struck up an unusual partnership with the masked lonestinger (Desperomyrmex spp.), a member of unusual solitary ants in which only winged queens and drones exist: never producing sterile workers and soldiers and living a self-sufficient life tending to their own larvae and providing them with food. At almost 1.5 inches long, with a hard exoskeleton, powerful mandibles and a venomous sting, a masked lonestinger is a force to be reckoned with, and can easily repel an advance scouting party of reaper ants before they can overwhelm the ranchers. In return for her protective services, the lonestinger is allowed to prey upon a few oxgrubs as food for herself and her larvae: a small price to pay for the ranchers as opposed to let the reapers wipe out their whole herd, and the rancher ants themselves too.

The aforementioned ant species are only a few of the most remarkable species of the rainforest, and are but a sampling among hundreds more of more-mundane types. This abundance of ants forms a significant part of the diet of an unusual tree-dweller: the magma treesquoad (Pyrocochleoteuthis arboreus). At home in the canopy, this squoad's six gripping tentacles are armed with suckers and are equipped with powerful longtitudinal muscles, allowing it to make long jumps from branch to branch, sticking tight upon contact with the first stem or leaf it touches. Its bright colors are a warning to predators: with a diet of ants, it is not only resistant to their toxins, but incorporates them into its skin secretions as well, causing an irritating burn to any predator that tries to put one in its mouth. While living in treetops, their eggs are still dependent on water, and so they carefully select pools of water in the leaves of arboreal leaferpools to act as their nurseries, with tiny, fully-formed squoadlets hatching from the eggs in a two to three weeks' time, already able to fend for themselves at birth. While young, they are well-camouflaged, as they build up their toxins by eating large numbers of ants, and only upon maturity do they display their bright colors, now fully-armed and an unpalatable experience for any amateur predator.

Meanwhile, the rainforest is irrigated by a vast network of rivers and streams, all of which harbor a varied collection of aquatic life. Aquatic plants grow in great quantities, some anchored in the bottom sediment and fully submerged, such as bottom gunkwort (Hydrolutugramen spp.), a type of freshwater seagrass, or growing along the edges of the riverbanks and peeking above the surface, such as reed bramboo (Calamugramen spp.). Descendants of clovers, their triple-lobed leaves still recognizable, float on the water's surface, some large and lily-like, others, such as clovefloaters (Aquatrifolium spp.) being small and duckweed-like, their long roots trailing freely in the water.

These plants provide food and shelter to various aquatic insects, which use them as refuges to hide from predators as well as ideal homes to rear their young. Reed waterwasps (Aquavespa spp.) clamber upon the stalks of reed bramboo, the adults feeding on the plants' sugary tissues but also using them as lookout points where they can dive into water and catch small aquatic prey to feed their carnivorous larvae. Specialized water-repellant hairs coat the waterwasps to trap air bubbles close to their bodies. Females use their wings as air tanks, allowing them to breathe as they dive: as such, they have become basically flightless, while males, who live only a few days and no longer eat, are fully flighted to search for mates.

Male waterwasps are not the only insects buzzing about slower streams and stagnant pools: an abundance of muckflies (Caenumuscus spp.), small dipteran flies, form whirling clouds above the surface feeding on pond scum and algae, while their aquatic larvae swim beneath in jerky wiggles, filtering out particulate detritus from the water. Less benign, however is the much more fearsome cousin the masaka, with one local species, the red-legged masaka (Culicimimus erythropus) being the largest of its clade, boasting a wingspan of nearly 3 inches. While both sexes feed on sap and nectar for sugar, females, in convergence to numerous other Earth dipterans, have developed a taste for vertebrate blood: piercing their skin with needle-like proboscis to puncture small capillaries and acquire a protein-rich meal. In spite of this gruesome adaptation, however, the masaka provides a vital role to the ecology of the riverside habitat, as, by feeding on larger animals, they return nutrients and biomass from higher rungs of the food web back to the lower trophic levels of the insect scale and beneath. The larvae of maska and muckflies, teeming by the millions in any available body of water, are a vital food source for the shrish and pescopods and aquatic insects of the ponds, lakes and streams, which in turn are themselves eaten by larger animals. In essencce, the masaka's bloodthirsty habits actually make the entire micro-ecosystem possible, as they exploit a food source much bigger than themselves to rapidly swell their numbers. Their larvae are also joined in the water by pond scuds (Allocrustaceus spp.), small crustaceans that, perhaps surprisingly, are not shrish at all, but descended from small freshwater crustaceans introduced accidentally into the biome during the early founding years as dormant eggs, though the immense success of krill-descendants has stopped them from making a large impact and thus remained similar to their small, ancestral forms.

Adult masaka and muckflies are prey to draclets, here represented by the turquoise pond draclet (Vespadraculus caeruleus), long-bodied, stingless wasps that have adapted to hunt other flying insects midair, utilizing unparalleled agility and maneouverability to capture the most evasive of prey. Seizing them with their grabbing, hooked legs, they dispatch their prey with their mandibles instead, either to eat for themselves, or haul back to their nests for their larvae. Each mother draclet can simultaneously tend to up to a dozen different larvae at once, housed in small cuplike nests hidden near water and made of mud and debris: and containing only one larva each, as the young are cannibalistic and would eat one another if kept together in the same nest.

These aquatic insects are in turn a source of food for the many species of shrish and pescopods that inhabit these rivers and ponds. A numerous collection of these mollusks and crustaceans, filling the empty gaps of Earthly freshwater fish, forming a middle rung of the river ecosystem's food chain. Some shrish, like silver shrinnows (Sylvopescocaris spp.) are found almost anywhere, gathering wherever algae and detritus are abundant in more gentle currents, while red-lined brookshrawns (Erythrolineocaris vulgaris) shoal in faster-flowing streams and rivers, braving the upstream currents to spawn. On the silt-covered bottom, flat-shelled mudtrawlers (Platylutucaris sublacuna) rummage for the remains of other shrish's food scraps, droppings and carcasses, helping keep the water clean and preventing it from becoming too cloudy due to a build-up of decomposing waste, which can lead to microbial blooms that can suffocate all the ponds' residents.

Among the pescopods of the rainforest river system, none are as bizarre as the spotted flopsider (Laterocochleus asymmetroculus), a surface-dwelling species that prefers slower-moving currents where insect larvae aggregate. Its most noticeable features are its sideways-swimming posture, and the fact that its eyes are completely asymmetrical: one eye, small and long-stalked, is adapted for seeing above the water's surface, while its other eye, shorter-stalked and larger, is better equipped for underwater vision, with the two eyes differing in the thickness of their lenses to account for the difference of refraction in air versus in water. This asymmetry can happen on either side, linked to the same mechanisms that determine whether other gastropods have their shells coil to the left or to the right, in spite of the flopsider's ancestors having lost their shells a long time ago as they adapted to a more active lifestyle. Able to see both above and below the surface, the flopsider can keep watch for predators both under the water and above the surface.

And it has cause to be wary, as it, and many other small aquatic animals, are prey to the banded cuttercuttle (Venatocochleoteuthis tigris), a freshwater skwoid that is the largest invertebrate predator of the jungle rivers. Measuring up to a foot in length, this powerful hunter is equipped with a saw-like radula to help dismember its prey, as well as small hooks on the suckers of its tentacles that allow it to grip its quarry. While its prey typically consists of shrish and pescopods, it is not picky as an opportunistic hunter, and small pondrats, wading pterodents, and even smaller members of its own species are likewise on the menu.

And of course, while millions upon millions of plants, fungi, microbes and invertebrates form the bases of the rainforest ecosystem, the numerous vertebrate hamster descendants live and flourish in this biome in many shapes and sizes. Dominating as local megafauna, these Gestaltian forms are distict from the fauna of other continents, evolving in geographic separation yet converging in many ways to the other, unrelated animals to whom their niches share.

Notable among them are one of Gestaltia's unique animals, the trunked walkabies. Generalist omnivores, these are represented in the rainforest by large, ground-dwelling omnivores such as the spotted forest trunkuffle (Dipodotapimus punctalbus), a forest-floor forager that feeds on fallen fruit, seeds, roots, fungi, shroomors and invertebrates, while up in the trees arboreal rhinocheirids such as bracelet-nosed treebumms (Nasobrachius annulocheirus) feed on leaves, flowers, fruit, and insects as they climb and leap across the branches on their six prehensile limbs, in many ways being the Gestaltian equivalent to Mesoterra and Arcuterra's lemunkies, absent on this continent, though their cousins the basal squizzels, such as the blacktip squizzel, (Melanocaudosciurumys minimus) are also native here as a few odd species, hoarding the seeds and fruit of epiphytes and helping contribute to their spread.

Meanwhile, ringtailed checkerbacks (Arbosaltocricetus annulus) also occupy the canopy, browsing on the abundant epiphytes that grow on the branches, resistant to their defenses that would make them unpalatable to squizzels and treebumms. They descend from the few remaining hopping boingos, who, displaced from the plains by podotheres called rebounders, have now taken to the trees in a last-ditch effort to survive the changes of the Middle Temperocene, their resistance to toxic bleedweed grass proving useful in occupying the barely-contested niche of epiphyte browser.

Another Gestaltian endemic, the badgebears, are also found in the rainforest, occupying an unusual dichotomy of niches. Some, such as the brown bruinbrowser (Phytoursomys macronyx) are almost entirely herbivorous, foraging on a diet of fruits, plant matter and occasionally invertebrates, others, descendants of the predatory fasbears such as the jungle bearguar (Pantherursomys pardus) are obligate carnivores, and occupy the top spot of apex predator, their diet including walkabies, herbivorous badgebears, and, most significantly, the various species of ungulopes, such as low-browsing pale-rumped junglebucks (Sylvocervimys alboposterius) that eat low understory vegetation and high-browsing rainforest altolopes (Sylvaltungulus conoceros) that browse on leaves of higher canopy trees but also relish the abundant clovervines and beardmoss growing on the tree branches.

One animal even the fiercest bearguars will not touch, however, is the orange-tailed thorntop (Echinospinomys xanthus) a large member of the heckhogs related to the irididescent bluehog, whose sharp quills double both as decorative structures to display to other members of their own kind, and defensive weapons that protect them from predators. Thorntops, while primarily herbivorous, will sometimes catch and eat poisonous squoads, then lick the irritating mixture onto its quills as an additional line of defense. While they are resistant to its compounds, other animals are not, and being pricked by their toxin-laced quills can lead to painful inflammation that can last for days at a time.

Above in the trees, a wide diversity of ratbats call the branches and trees home, their nests secluded in tree hollows where they rear their young until they learn to fly by themselves. While white-streaked barkpickers (Phyllonyctomys melanoleuca) gnaw on the bark of trees to search for insect larvae in the wood, ebony shaderwings (Umbrapteryx corvinyctus) gather berries and seeds that they stash away in larders they chew into trees, and flocks of tricolor aerimuses (Varicolonyctus vulgaris) swoop and dive as they catch flying insects midair. At night, once most of the diurnal ratbats have gone to roost, nocturnal ones, the more basal evening dingbats (Noctopteromys macrotis), take to the air to hunt for night-pollinators like moths. They are distinctive in that their sprawled limbs make them clumsier on the ground than more derived ratbats, and thus prefer to hang from branches to rest, and avoid competition from their diurnal kin by foraging in the cover of darkness: relying on echolocation rather than sight to avoid obstacles and home in on prey.

The rivers and streams of the rainforest, with plentiful food, are frequented by many other hamster species too, which have adapted to a semi-aquatic lifestyle to take advantage of its resources. Forest creek pondrats (Riverrocricetus sylvus) build their nests of sticks and twigs on riverbanks, plastered with mud to conceal it from predators. They are herbivorous, and greatly relish reed-like bramboo that grow on the water's edge, in particular the tender young shoots that spring up feom the main rhizome. Meanwhile, wading pterodents, such as the black-legged swanji (Cygnornimys nigripus), a relative of the mountain-dwelling silver soarers, lives a lifestyle in great contrast to its alpine cousin, foraging in ankle-deep water for the shrish, pescopods and skwoids that make up much of its overall diet. This is in spite of most pterodents being cumbersome at taking off from the ground, but the abundance of trees enable it to make a quick getaway with the help of its wing claws that enable it to quickly scale trees for an easy launch into flight, should any attacker be persistent enough to pursue it up the trees.

With a warm, tropical climate all-year round, the Gestaltian rainforest is unsurprisingly welcoming to ectothermic rattiles, of which many unique kinds are found here too. Scurrying across the leaf litter are red-banded candytails (Saccharosauromys erythrocauda), whose colorful tails act as signals for display, and distractions for predators to draw attention away from their heads and bodies. Uniquely, while they are unable to regrow any lost portion per se, the stub will lengthen its remaining vertebrae to a length similar to that of the original tail but stiffer and with fewer joints, and in some old specimens which had lost their tail several times their now comically-rigid tail can be comprised entirely of just one or two grossly-lengthened bones.

Up in the canopy, the abundance of hundreds of species of ants has unsurprisingly drawn the attention of arboreal burrowurms, such as purple-tongued piedvipers (Erythrophiomys phagomyrmex), which use their short foreclaws and long tongues to break into the nests of ants and gorge themselves on the residents. Their thick keratinous scales are extremely resistant to bites and stings, and their acidic spray has little effect thanks to a transparent third eyelid that protects their eyes when they feed. In fact, piedvipers are able to sequester these compounds to deliver painful stings themselves through the glands on their front claws that they use for self defense. So effective is their weaponry that many other burrowurm species, collectively known as "false piedvipers", mimic their coloration despite not possessing any claw-stings of their own.

And with such an abundance of flora and small invertbrates, the flying wingles are also present, most commonly the goldwing wingle (Aureosauromys splendipteryx) which flits and flutters among the plentiful blooms gorging on nectar, pollen and small insects. At night, they take shelter among the nooks and crannies of tree branches and their own small forests of epiphytes, females and immature males more drab and brown to hide among the mossy bark while mature males sport brilliant yellow tones that make them stand out: perhaps even as a deliberate handicap that any male which can survive in spite of, is a truly fit male and a worthy mate indeed.

Together, all these plants and animals, and the various organisms in-between, form the complex and diverse ecosystem of the Gestaltian rainforest. Thriving in millions of species, be they up in the trees, on the ground, amidst the leaf litter and soil or swimming and wading in the web of rivers spreading across the forest, from small insects to large megafauna, all these living things are inextricably linked to one another, and a testament to the adaptability, codependence and diversity of life on HP-02017 as a whole in the era of the Middle Temperocene.

---------------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#biome post

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

These are adorable, love the style!

Fanart of the sapient hamsters from @tribbetherium's seed world Hamster's Paradise.

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

The rise and fall of a savage, thinking mind, ever so briefly in the span of deep time, torn down by the plague that was to be their legacy.

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#path of descent

317 notes

·

View notes

Text

@eternal-gromnommer Interesting take! I love how you justified the other more unusual features with ontogeny! Definitely something to keep in mind.

I'd love to get into the later epochs soon but sadly my schedule is too busy for me to post much. I had lots of free time during pandemic lockdown but now that activities and university and work are back on track it's given me less time to work on things...

Fanart of the Brontodactyl from "Hamster's Paradise" by @tribbetherium ! Not yet a canon species as of now but it's from this animation.

Since it was said to have descended from the flying pterodents and knuckle-walked I liked the idea that it was flighted to a limited extent at least when young so it could perch on its parents' backs for safety and gradually lost the ability to get airborne as it grew bigger and heavier.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In spite of the massive diversity of species descended from the initial hamster ancestors over the course of 150 million years, many species still retain vestiges of their ancestry through their dentition: two pairs of central incisors, no lateral incisors or canines, and six pairs of molars, which, in many species, have been modified greatly to suit their diet. This remnant trait can be found even in the most unlikely of creatures: including those such as the daggoths, which, were it not for these gnawing incisors, would have no visible and recognizable ties to their rodent heritage.

But exceptions do exist, as not every ecological niche requires the use of dental equipment for mastication. One noteworthy example is the red-tailed ebony adentate (Adontosauropteryx noctifuriens), one species of wingle native to Gestaltia that subsists primarily on nectar and pollen from the large, sunflower-like blooms of solstems: members of the cabbage family whose gaudy flowers are in fact clusters of numerous smaller ones. Their carbohydrate-rich nectar and protein-rich pollen, scooped out with their long, bristly tongues, is all these active flyers need to survive: and thus have lost their teeth entirely. These nutritious blossoms in particular cater to mature males--distinguished by their bright red tails that they use for display--as it is their energy-intensive task to protect territory from rival males, search out receptive females across long distances, and care for the offspring as most male wingles do, until the young are mature enough to fly on their own at four to five weeks of age.'

------------------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#art one shot

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

'The Early Therocene, 30 million years PE.'

'Illuminated by beams of daylight piercing through the dark, icy waters of the arctic seas, a female megaprawn--largest of the shrarks-- spawns a clutch of eggs several hundreds of millions strong, having mated several times in the days prior and provided spermatophores by multiple males with which to fertilize her eggs internally. At slightly over two meters in length, the megaprawn very closely approaches the upper maximum size physically possible for a marine arthropod: yet each of her spawn are only a millimeter in diameter, soon to hatch into tiny nauplius larvae carried along by the currents of the open seas. While she fears no creature in this day and age, as the Therocene seas' apex predator, her numerous young drifting along are easy prey for the ocean's many creatures as part of the zooplankton that form the base of the marine ecosystem's food chain. Of these millions of offspring, fewer than one percent will last long enough to reach the size and stage where they become active swimmers akin to typical shrish: and, by the time they reach adult size, a feat taking several decades and dozens of molts, only about two or three of the original clutch out of a hundred million would have survived--fortunate enough against all odds to manage to achieve such a milestone.'

----------------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#art one shot

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Formed from the fusion of East Nodera and North Ecatoria, Mesoterra in the Middle Temperocene is home to the descendants of the various species that once called these ancient landmasses home. Of East Nodera, its wildlife are survived by the threepeaked tricorn, an alpine grazer that is Mesoterra's only extant ungulope, and the pinguiphants, semi-aquatic walkabies adapted to forage on Mesoterra's shores.

But small, offshore isles off the coast of Mesoterra harbor some unusual holdovers from an older age. And one such isle is Isla Easnodus on the southwestern coast, where, hidden from the rest of the world, a tiny remnant of its Therocene past continues to linger.

The banded forest streewi (Microstruthiomys gymnorrhinus) is a late-surviving relic of the hamstriches: walkabies adapted for running on open ground. These would eventually disappear as the continents merged into mainland Mesoterra, with their niche more or less being taken over by the podotheres, another cursorial bipedal clade that come to dominate Mesoterra's ecosystem, and later spread far and wide as far as Arcuterra and Ecatoria. On the mainland, the walkabies that did survive were ones that took to the water to become the pinguiphants, but on these offshore islands, the hamstriches shrank down to a miniscule size of less than four kilograms at most, in an isolated environment, giving rise to the streewis.

The banded forest streewi dwells on the forest floors of the island's tropical forests, formed from seeds that were carried over from the droppings of ratbats and pterodents. A small, generalized omnivore, it feeds on fruit, seeds and small invertebrates, and lives in small social groups, consisting of one or two males and up to a dozen females. Mature males are distinguished by their bold, striking markings and broght red bare patches on their faces which they use for social display and to show off to potential mates. Like most walkabies they possess elongated snouts, which, while not as dexterous and pronounced as in rhinocheirids, are still useful tools for foraging for food in the forest floor and undergrowth.

While facing threats from the sky, in the form of predatory ratbats, the banded forest streewi has no enemies on land. As such, their primary defensive strategy is to huddle in groups when startled, seeking shelter underneath vegetation to hide in their shade from the view of aerial hunters. With their sole danger coming from above, they came to forage in small, tight groups, with individuals taking turns to keep watch and alert the group at any sign of an airborne predator.

Female streewis give birth to a single offspring at a time, after a gestation period of about four months. The young are born fully-furred and open-eyed, and remain with their mothers for up to a year at most, weaning at six weeks but continuing to follow her even afterward, learning to forage and take shelter from danger by watching from example. With few enemies and a smaller land space, they grow slowly and breed infrequently, once every two or three years depending on climate and food availability.

----------

#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec evo#hamster's paradise#species profile

81 notes

·

View notes