22 . French ( Native ), English ( C2 ), Irish ( A2 ), Greek ( A1 ) . Arts and Language Studyblr . Aspiring Librarian

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I saw someone recently say that they use chatGPT to get information about language rules (grammar, sentence structure, translations, etc) for languages that are very rare and have pretty much no information available online.

And that really stuck out to me because generative AI like chatGPT does not think. It doesn't magically have information about every single language in the world in its database. Generative AI works by deciding what words are most likely to be next to each other in a sentence, based on information it pulls from either its internal database or from whatever online resources it is given access to.

So if you're looking for information about, for example, Ojibwemowin grammar and you can't find ANY information about it online no matter how long you search, but chatGPT somehow has the exact information you're looking for? Then whatever chatGPT is telling you was made up. It took a bunch of different resources about a bunch of different languages, probably using pages that mentioned Ojibwe once or twice, and smashed it all together into something that looked somewhat coherent to someone who doesn't actually know the facts. Whether it's accurate or not doesn't matter because that isn't actually the purpose of generative AI.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Spent this sunny Sunday afternoon having a cozy language study session 💕

294 notes

·

View notes

Text

Texts and doodles (literally anywhere I can reach, I’m a child with crayon when it comes to doodles)

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

learning non-european languages is only difficult cuz there's so little info outside of schools and textbooks. except for Mandarin, Japanese, and Korean. they get special treatment. where are all the Burmese instructors online? or the lengthy explanations of Vietnamese idioms? or the videos explaining Malayalam verse and rhyme? we need more sub-saharan african and non-east asian language learning material online damnit.

368 notes

·

View notes

Text

21.05.2025 🌿 what a wonderful day! i went to the market with a couple of friends, had a really good violin lesson and they gave me free coffee at the bakery + i got a near perfect grade for my term paper :)

284 notes

·

View notes

Text

May 20th, 2025.

Warming up my brain with some math concepts today—and after a long time, I actually used paper for the calculations. It rained a lot, but somehow the sun’s still out. Can’t say I don’t love that.

250 notes

·

View notes

Text

19.05.25 🍓 ☕ 📚 somehow this semester is not stressful enough to complain about but just stressful enough to feel tired all the time, so i let myself be peer-pressured into drinking coffee for the first time :') bitter af

514 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transcript Episode 104: Reading and language play in Sámi - Interview with Hanna-Máret Outakoski

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘Reading and language play in Sámi - Interview with Hanna-Máret Outakoski’. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Gretchen: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Gretchen McCulloch. I’m here with Dr. Hanna-Máret Outakoski, who’s a professor of Sámi languages at the Sámi University of Applied Sciences in Kautokeino, Norway. She’s a native speaker of Northern Sámi and Finnish and fluent speaker of Swedish. She can read German and uses English mainly for academic publishing purposes. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about multilingual literacy.

But first, some announcements! We’ve commissioned a jazzed up version of the Lingthusiasm logo with fun little doodles in the classic shape of the Lingthusiasm squiggle adorning your podcast reader right now – now filled in with some linguistics and Lingthusiasm references in little, tiny doodles. See how many you can spot! We’re gonna be sending out a sticker with this new design to everyone who’s a patron at the Ling-thusiast level and higher as of July 1, 2025. If you wanna get this sticker that can adore your laptop, water bottle, and help maybe connect you to other people who are enthusiastic about linguistics, go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm. If you just wanna see a version of this sticker and see how many of the little doodles you can identify, you can go to lingthusiasm.com or @lingthusiasm on all the social media sites. We’ll be posting about it a lot. Our artist, Lucy Maddox, did a really great job, and we’re so excited to share this design with you.

Our most recent bonus episode was about the linguistics of kissing from the physical articulation of kisses – which involves the mouth, much like many linguistic things – as well as the social significance of kissing in various ways, various times to various classes of people, to writing kisses as Xs and with emoji. All of that and 98 other bonus episodes at patreon.com/lingthusiasm help keep the show going.

[Music]

Gretchen: Hello, Hanna-Máret, welcome to the show.

Hanna-Máret: Hi!

Gretchen: It’s so nice to have you here.

Hanna-Máret: It’s really good to be here.

Gretchen: We’re gonna get into more of your work later, but let’s start with the question that we ask all of our guests, which is, “How did you get interested in linguistics?”

Hanna-Máret: I grew up in a multilingual region in northern Finland that’s as far north in Europe as one can get. In my childhood, most people living there, they knew my Indigenous heritage language (that’s Northern Sámi), and they also spoke either Finnish or Norwegian or both. We also learned a lot of English in school and through TV. My home was also right at the border of Finland and Norway. There was only a river marking the state border. Some languages float quite freely in that region. For many people, knowing languages was quite natural. Most people didn’t think so much about the languages, but my father was always talking about some linguistic traits or challenges or other matters. He was a special teacher and had always had an interest in languages and for linguistics. His language enthusiasm spread into my life very early. He also read to me and encouraged me to read a lot in different languages, and then we used to talk about the literature afterwards. I was also really fascinated by the language knowledge and cultural knowledge that my Sámi relatives had, although most of them were not academics. The Sámi speakers in the generation before mine were actually the last ones to grow up speaking mainly Sámi. Their language was so beautiful and so effortless. I decided quite young that I would pursue a career working with my heritage language and do my best to support its survival.

Gretchen: That led you into linguistics.

Hanna-Máret: Yeah, but first I considered a career as a translator or interpreter. I actually got a basic training in that also. But I worked as an interpreter mostly just to make some money so that I could continue studying at the university. I studied Sámi, Finnish, linguistics, pedagogy, and I got a bachelor’s degree in Sámi language. Some of my professors then encouraged me to reach for the master’s degree and then continue with the PhD.

Gretchen: Did you go right into Sámi language revitalisation work, or were you doing more academic stuff?

Hanna-Máret: Well, my first attempt with the PhD was actually in formal linguistics. I was working on reflexivity and reciprocity in Sámi and this more specifically with Government and Binding Theory, which had, at that time, not yet lost its glory. I actually never finished the thesis. Instead, my teaching responsibilities grew every year, and I started noticing that I was more interested in the use of language than in some isolated syntactic structure. I don’t want anyone to get me wrong here. I’m really grateful for having acquired a base in formal linguistics since it has given me the tools not only to describe my language but also to problematise and solve some issues that our traditional, prescriptive grammars in some languages are not able to explain. It’s just that, at some point, I started thinking more about the work that was needed to keep the language in daily use and not just the structures.

Gretchen: But you have a doctorate now. You went back and did something else?

Hanna-Máret: My second attempt to finish the doctoral degree was, happily, a bit more successful, and I get the chance to gather texts written by multilingual Sámi children in three countries. Me and my colleagues, we used something that’s called “keystroke logging” to trace the ways our writers express their thoughts and ideas in three languages. I really found that project very inspiring, although it also showed me how challenging it can be to work with schools and pupils. After that PhD, I got a chance to do my postdoctoral studies within applied linguistics and educational sciences.

Gretchen: Three languages – that would be Sámi, Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish? That’s four.

Hanna-Máret: I was in three countries. It was the majority language of all the countries. In Finland, Finnish; in Sweden, Swedish; and in Norway Norwegian. All the kids here in Nordic countries also study English, so that was the third language.

Gretchen: Okay. The third language depending on the country they did – yeah. Did you bring all of these different backgrounds together?

Hanna-Máret: I think that all of the steps on the way there have been really important for me. I’m not a nerdy expert in any given subject, but I have gotten a lot of experience from different fields, which actually is a necessity when working with literacy development in a revitalisation context.

Gretchen: Yeah, I think that’s one of the things that’s really interesting about language revitalisation work is that it draws, really, on all of the different areas of linguistics.

Hanna-Máret: That’s true. I moved away from that personal academic interest and those long days in the office analysing some specific language structures and then moved toward research that actually comes from the needs and the interests of the language community. I think that I still steer all of my projects toward the field that I mastered the best, whether it be literacy development or language didactics or teaching of languages in virtual environments and worlds. That’s only so that I can do my best in the project that I initiated in collaboration with, for example, Sámi language teachers.

Gretchen: If they want to have some aspect of the grammar explained to them, then your training in formal linguistics can help you do that.

Hanna-Máret: It can do that. I also feel that all my knowledge – I don’t want to lose that. I steer the project – even though I want them to be initiated by the teachers – but I tell them, “Well, these are the fields that I know best, so can we do something together within these fields?”

Gretchen: That makes sense. It’s a collaboration. I wanna maybe back up a little bit because I’m from Canada; I don’t know all of the details about Sámi languages. You mentioned already that they’re spoken in three countries. Maybe you could talk a little bit more about Sámi languages and how they relate to other languages in the area.

Hanna-Máret: There are several Sámi languages and also Sámi groups living in a quite big geographical area. It stretches from the middle of Scandinavia in Norway and Sweden over to over the northernmost Finland, and all the way to Kola Peninsula in Russia. It’s a huge area. Many Sámi still live in their traditional home settlement regions, but many have also moved within the traditional home region. For example, I live now in a bigger city in Sweden that is also included in Sámi, but I come from a little Sámi village located at the border of Norway and Finland. I also know that a large group of Sámi live in the bigger cities in the outskirts of Sámi and also in the capital cities of Nordic countries.

Gretchen: And there are several Sámi languages?

Hanna-Máret: The common understanding at the moment is that there are still nine surviving languages, but actually, the situation of the smallest languages on the Russian side of Sámi, that is not the land of the Sámi people, it is quite uncertain. All of the smaller Sámi languages are really extremely vulnerable to changes in speaker networks. All Sámi languages are endangered.

Gretchen: For you, which of these Sámi languages are you closer to?

Hanna-Máret: I have a special relationship with the language that I speak myself. That is Northern Sámi or North Sámi. It is the largest of the Sámi languages, but exactly how many speakers there are, that is unknown. I don’t know how many people there are. This is due to the restrictions in keeping statistics over ethnicity and minority languages in Sweden and Norway. What we do know with certainty is the number of children who are studying Sámi languages in compulsory school in the four countries. That number is actually well under 4,000 individuals. More than half of them are studying Sámi as a second language or as a separate subject in school. Only less than one-third of the pupils have Sámi as their main language of instruction. All of those pupils who study everything in Sámi, and they live either in Norway or in Finland, not in Sweden or in Russia. I think that that language situation of the school-age children serves as a quite good mirror of the rapid changes in demography and language shift among my people.

Gretchen: There’s no Sámi language school in Sweden or in Russia?

Hanna-Máret: We have Sámi schools in Sweden, but even there, the Sámi language is a subject, and they do have some other school subjects also taught in Sámi, but not fully. I was very lucky. I went to school where all of my – everything from biology to mathematics, everything – was taught in Sámi. I was very happy and lucky that I grew up in the Finnish Sámi.

Gretchen: In Canada, we have these French immersion schools where all of the subjects are in French, but the students are generally English-speaking. People have been quite excited about them, but now that the first generations have gone through the French immersion schools, they come out and they sort of speak French, but they also don’t necessarily speak French the way someone who used French in everyday life speaks French. Do the kids come out speaking Sámi?

Hanna-Máret: Well, I think, like you said, it depends a lot if they get it at home, if they have it in their free time. There are still children who come from Sámi homes where they hear it in their everyday life and not only in school. For those children, I think that it’s really, really good to be able to study the language, also, as a subject in school. But I have also seen that it’s not a guarantee that they will learn Sámi even though they go to so-called “Sámi” schools. They need support at home and everywhere and not only in school.

Gretchen: Yeah, absolutely. You’ve worked a lot on teaching writing and literacy in the Sámi context. How does that interact with speaking and with the work in the schools?

Hanna-Máret: Even though my research focus is on teaching and learning writing in the Sámi context, I would not want to compare or separate speaking and listening and writing from each other. What I mean is that all of those skills are needed in literacy development. I think that my own teaching methods, they always combine all the three all the time. But what I’ve seen in my school research projects is that writing in Sámi is often left with the least attention in the primary schooling of Sámi children. I’ve also seen that there are great differences between the countries. Finland is globally known for extensive reading and writing instruction. The education of Sámi children in Finland includes more writing than, for example, the education of the Sámi in Sweden.

Gretchen: What do you think is the way that you prefer going about it?

Hanna-Máret: Well, I always promote language didactics that has a more balanced take on the teaching of different language skills. I think that the imbalance that I’ve noted in my projects, it really risks leading into a situation where the coming generations will no longer be able to withhold the literacy traditions of the Sámi society. I’ve also seen that many times people are hostages of their own language beliefs or ideologies. This mantra about Sámi languages being oral languages, that is outdated, but it’s also very regularly used by the Sámi themselves. Many people, therefore, believe that written language threatens the oral traditions when it, of course, in fact, can strengthen those and other traditions, too. We are still in a hegemonic situation where we have these kind of ideas that Sámi has been a spoken language in the history, and it should be like that forever.

Gretchen: What are some of the literary traditions of Sámi society?

Hanna-Máret: There are really, really old Sámi joiks. They look almost like poems – very beautiful poems that are already in the 1500s they were written down. We have this long tradition, and we have even a lot of religious texts that were written in Sámi and novels that came in the beginning of the 1900s. But there have been books for teaching and that kind of thing. We have had possibilities to teach and learn writing, but it has never been part of the school system before. That came much later.

Gretchen: Having children who are learning Sámi in school to be able to connect with those historic literary texts as well seems really interesting and important.

Hanna-Máret: Yeah, well, I’m not sure if the kids are so interested in that kind of literature. I’m not sure about that. [Laughs]

Gretchen: Yeah, maybe something from the 1500s is less interesting to modern-day children, that’s true. Maybe when they get a bit older some of them might be interested.

Hanna-Máret: I think the oldest poems are really, really beautiful. It’s so nice to think that people have had this tradition of making joiks and really beautiful love poems. I dunno if the young kids like that so much, but they might

Gretchen: A “joik” is a kind of poem?

Hanna-Máret: “Joik” – it’s part of our song tradition. There’re joiks that don’t have so many words, but there’re also long joiks that have almost epic stories that are being told about the history and so on. We have had that. It is also something that is vanishing that the moment – joik traditions – not so many people know how to do it anymore and not so many people know the old joiks. But there are still some really good people who know that.

Gretchen: That sounds really cool. Is it more of a private community thing, or are there people who put them on YouTube or something like that?

Hanna-Máret: Well, it’s not like – I’ve learned that in Canada there’re some groups that it’s very sacred knowledge, the singing knowledge, but in the Sámi society, we have some special joiks that they are given. We “joik” people. We don’t “joik” about them. Some of them are private within families, but most of them, like, for example, there’re very nice animal joiks, and we joik even the animals, and we joik also, for example, the mountains and the waters. When you’re joiking them, you give them a musical substance, so they become alive in the music. Those are shared within society. They are open. There are even archives where you can go and listen to some of these.

Gretchen: Oh, cool, maybe we can link to one or two examples of those if people wanna go see in the show notes. I think we’re answering some of these questions already, but do you wanna talk any more about why teaching and learning writing is important in this Indigenous language context?

Hanna-Máret: I think that maybe the best and the shortest answer to this question is very simple. It is for the same reasons as writing in any language. Writing is a way of remembering, describing, and imagining. Today, writing skills are also needed for full participation in the democratic society. Writing and reading in, for example, North Sámi, makes it possible to take part in the trans-Nordic Sámi society. Teaching and learning writing, it happens most often in schools and, thus, having access to writing instruction and writing opportunities in school is really crucial for the development of Indigenous literacy. Of course, there are a number of factors that can hinder the process of learning and teaching Indigenous children to write and read in their own languages. In Sámi we are faced with many problems, but mainly three kinds of challenges. Those are either connected to the shortness of human resources, or shortness of adequate teaching materials, or to the shortness of teaching hours, or all of them in some combination. The reasons for promoting teaching and learning of writing are the same between people and languages. That’s what I think, at least. But the available human material resources might differ as might the width and the breadth of writing opportunities. There are internal and external ideologies and language attitudes that often value writing in a majority language a lot higher than writing in Indigenous languages. We still have to remember that there are really no – analphabetic – or “illiterate” over 6-year-old Sámi people today. We all can read and write in our respective majority languages, but most Sámi are actually insecure about writing in their own heritage language. Many have never even been taught how to do it.

Gretchen: Reading and writing skills don’t – even though Sámi uses the same alphabet, I think, as Norwegian and Finnish and so on – at least I’ve never seen it written with a different alphabet.

Hanna-Máret: We have some special letters in North Sámi. Also, the problem is that most of the Sámi languages – the Sámi languages don’t share the same orthography. We don’t write our languages the same, which is a problem. North Sámi has its own special letters. South Sámi they do it in a different way. It also is something that makes it a bit complex and difficult.

Gretchen: But even if people know the alphabet already or most of the alphabet without depending on the special letters, that doesn’t mean that the skill of reading and writing necessarily transfers automatically to another language. You also have to have training in practicing using it.

Hanna-Máret: Exactly. There are so many special traits in North Sámi. For example, we have a gradation – consonant gradation – which makes it quite difficult. You really need to have training in how to write so that you get things right.

Gretchen: What do you mean by “consonant gradation”?

Hanna-Máret: For example, if we have a subject that is in nominative, then it has different consonants in the middle of the word than it would in the accusative (in one of the scripts). You have to even keep track of the consonants in the words. It’s a complicated system. It’s not always so intuitive for the kids, I have to say.

Gretchen: Maybe this explains – I’ve usually seen Sámi written with a double A, but I’ve noticed in your work that you write it with an A with an acute accent mark on it, just a single A. Are these different variations between different Sámi languages?

Hanna-Máret: Northern Sámi speakers, we call the native land “Sápmi.” The Sámi people call them “Sámit” or “Sápmelaš,” and the language is called “Sámegiella,” the Sámi language. All of these Sámi language groups, they have quite close variants of the name spelt slightly different ways in each language and at least three different spellings of Sámi language used in English sources. Those are the ones that you said “Saami” with two As. There is also a “Sami” with only one A, and the one that I use that is “Sámi” with an A acute, which is the spelling of my own language. I think that the two-A variant, it’s more often seen in sources that originate from Finland. The one-A variant is often used by non-Sámi academics outside Finland. The last variant is then very often used by North Sámi academics, so that’s why I use it also. I have also many times been forced into using the one A variant since the journal or the book publishers that have the English that they want to have, they prefer that variant.

Gretchen: It seems like the variant with just one A – because it is a long vowel. That’s what both the double A and the acute accent is trying to convey is that it’s /saami/ not /sami/.

Hanna-Máret: Yeah, exactly.

Gretchen: Just having the single A with no accent or anything doesn’t convey that.

Hanna-Máret: No. Because you could say /sami/, too. It’s only /sami/, and it doesn’t sound good for us.

Gretchen: It would be a different word or something, yeah.

Hanna-Máret: Of course, if you’re looking at older sources, then you would find the pejorative and outdated term “Lappish” for the language and “Lapps” for the people. Those are no longer okay to use. Otherwise, I would not want to say to anyone else which of the Sámi spellings they should choose. If I’m allowed, then I always prefer the A acute variant that is closest to my own language.

Gretchen: Sounds good. We’re gonna use the A acute variant in this interview because that’s what you use. Do you have any other fun facts about Sámi language or grammar that you’d like to share?

Hanna-Máret: Well, I’ll go with a really hardcore linguistic fact about Sámi languages. Sámi languages have a negation that agrees with the subject in person and number. In the traditional Sámi grammars, it has also, therefore, often been categorised as a verb, although it at least, in the generative tradition, would rather be a functional head of a negation phrase. In Southern Sámi, the negation can also carry tempus – like time morphology – if there’s no auxiliary that can do that job. That has been considered even better proof of the negation being a verb. However, the Southern Sámi is a so-called “affix hopping” language that leaves the main verb in the verb phrase, while Northern Sámi always needs some verb to occupy the head of the tempus phrase and can never show time on negation. But these kind of things, when you’re looking at the traditional grammars, you don’t get the explanation to these things. Then people just have to decide, “Well, how do we categorise negation if we don’t look at the structures that could be behind these things?” And then you get these labels that just don’t feel quite right.

Gretchen: It seems like, “Okay, is this a verb? Is this not a verb?” could be an interesting position for learners to find themselves in of like, “What am I trying to learn here?” That’s an academic or formal linguistic approach to looking at Sámi grammar. You also have this paper about applying Indigenous methodologies to literacy. Do you wanna say a bit more about what you mean by “Indigenous methodologies” in this context or how they relate to literacy?

Hanna-Máret: Well, I guess that in that paper I actually highlighted that we are still missing those robots – the Indigenous methodologies in the field of literacy research. As long as we don’t have any specific Indigenous methodologies, we may be forced to continue using at least some of the Western data gathering methods and analysing methods. I think the main point of that paper was really to show that, also, literacy research should try to follow as many of the Indigenous research principles as possible, even when the methods are still on their way and being developed and not there yet. In that way, it is possible to keep some of the Western methodology also in Indigenous literacy contexts but, at the same time, make sure that we do not do any harm and that we try to make research relevant, also, for the language communities that collaborate with.

Gretchen: You’re seeing it as a combination of the best parts of both worlds or just working with what we have at this point.

Hanna-Máret: I guess. Maybe I’m a bit of a pragmatic researcher in the way that I do not wish to turn my back on methods are part of well known Western methodologies if they work for the thing that I want to do. But I just want to find ways to make the research relevant for the participants. I guess that that’s why the word “collaboration” is so central for my own personal research designs, sometimes to the point that I’d actually rather be out there in the field supporting and helping to develop Indigenous and minority pedagogy rather than really producing academic papers that are rarely actually read by our Sámi participants. I’m not saying how other people should do or how they should feel; I’m just telling what it feels like to be a speaker and a researcher of a highly endangered language. I can’t really afford making a career only for the collection of academic points.

Gretchen: That’s a good point that there’s an increased sense of urgency to say, “Well, but like, I can’t just write papers that no one is gonna read except my fellow academics. I need to do something actually about the language.” Do you have any examples of something that you think is particularly important from an Indigenous perspective as part of the Western methodologies?

Hanna-Máret: I think that when I tried to do my best to save some languages, even though it’s a big job, and I might not be able to do so much by myself, I think that I’m always focusing on giving back. That is one of the very central principles in Indigenous research. What I mean by “giving back” is that I try to make the project count for the participants already during the active research phase by, for example, donating some of my research time for teaching or working in daycare or, for example, for producing bilingual materials for the teachers and other staff. Things like that. In action research projects, I also try to accommodate the needs of the participants, so that they are then able to move forward with their own action plans. In a way, my role is that of a facilitator and (not always) as an outsider researcher. I’m trying to be the one that facilitates the needs of the participants.

Gretchen: I think that’s a good point about trying to have even the process of the research by good for the participants and not just wait until you get the outcomes, and then it’s gonna be really good once I have finally written up the paper. Two years later, I’m gonna come back, and here’s what I’ve produced. But also the process of participating itself needs to already be something that’s useful for people.

Hanna-Máret: I guess for many of my participants and partners, that’s even the more important thing because they are also learning something when I’m showing them if I’m helping them with some things already during the project then, like I said, many times, the Sámi participants are not the ones who are reading the academic papers. Even if I would come back and tell them that, “Oh, here are five papers that I wrote. They came out in these journals,” they might just be like, “Oh, well, good for you. But we actually enjoyed it more when you were here; you were doing some of the hours; you were doing that and that.” I always try to find the balance so that I can do that, too.

Gretchen: Absolutely. Something like working in the daycare where you’re a Sámi speaker and can be talking to the kids in the daycare in the language or doing some sort of fun activities with them or something like that can be really, really helpful at the time – not just like, “Oh, we came back with this outcome about ‘Here’s how we should change the daycare to make it more effective’,” after all this time.

Hanna-Máret: Exactly.

Gretchen: You’ve also mentioned that there can be a bit of a clash between protectionism and encouragement when it comes to heritage language. Do you wanna talk about that a little bit more?

Hanna-Máret: Sometimes, as a speaker of North Sámi, I wish that we had already reached the same proportions of language shift as some of the smaller Sámi languages.

Gretchen: What is the situation in the smaller Sámi languages at the moment?

Hanna-Máret: There are few languages. For example, here, very close to where I live now, there is a Sámi language called Ume Sámi. There are, at the moment, maybe two, three, maximum ten people that are under 50 years old who are actually learning the language as their first language. The middle generation didn’t learn it as a mother tongue at all. They are just now trying to bring it back to homes. But there are so few people left who can speak the language, even the youngest generations who are now studying at school and parents who are trying to start speaking at home when they have been learning some courses – it’s a really, really different situation than for the North Sámi, the biggest language. For those groups – the only thing that I would then say that I hope that we were also almost at that point that the only thing why I say this is that we are now in the middle of a huge wave of change. The reactions exemplify the clash of this protectionism and encouragement that you were talking about, which I feel sometimes is less prominent in contexts where the community has to work together to save the language from that. They’re already been so close to death so that they just now have to either they completely just don’t work together at all, or they have to do everything for the language. We are not there.

Gretchen: It’s very focusing.

Hanna-Máret: Yeah, exactly. We are not there at all because our strongest speakers – those are the other generations – they see how the language of the young people is changing very rapidly at the moment because, yeah, English, Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish, they are winning in that competition. Some of these older people, they react really negatively, and almost they try to cast a protective spell on language and culture. In Sámi culture, we often speak about the “language police,” that is the individuals and collective forces that assess and openly criticise the language of the younger generations or the new speakers. Most of the time, the younger generations, they react as expected, and they stop speaking, and they stop learning the language because, of course, even they are aware of the internal change of the language that is going on between generations. They can hear their language is not the same. They may feel inadequate or wrong or ashamed and many other negative feelings that then re-enforce that reaction, that “stop speaking” reaction. The consequences of that reaction – it is often called the “language stigma,” or we say in Sámi, “language lock,” that’s what we say. It just locks the language somewhere.

Gretchen: It locks a language behind your tongue where it can’t come out of your mouth anymore because you feel so self-conscious about saying it.

Hanna-Máret: Exactly. Of course, I’m not saying that this is what happens everywhere because there are really a skilled people who are very encouraging. They are good at mentoring young people and speakers and those who are new to the language. Those people, they offer support and models and examples of language when the people are needing something to look at. They say that, “Oh, well, you can reach for this,” but they don’t demean the learners when they are in the middle of the process of learning the language. These kind of mentors and teachers, they know that reaching this rich language is very demanding and takes a lot of effort and time and even some luck. They need to support for a long, long time.

Gretchen: They’re not going around shaming the younger people for not speaking the way that they think they should be.

Hanna-Máret: Exactly. There is this little group of people who are doing it in that way. I hope that I also belong to this latter group. I always value the strong speakers of the older generation, but at the same time, I have a very great respect for the younger generations because I know that they will be the elders, the oldest and the best speakers of our language, in the future when we are gone. I try to make the learners feel the pride of the language and to feel that they want to reach for as rich a language as possible, like they would in the majority language. I also always tell them that I am a learner and that no one is ever finished learning the language. Sometimes, that helps. Of course, those who do not have the time or the opportunities to use the language or who are repeatedly discouraged during the process by these “police” or something else, they will probably never become very confident speakers or writers. It is clear that we, the teachers, we play a significant role in the future of our heritage language. We have the means to empower and encourage, but we could also create silence. So, I hope that we are doing the first one and not creating the silence.

Gretchen: There are plenty of older English speakers who are not particularly impressed by how younger English speakers are speaking the language, but because it’s not undergoing a language shift, the younger English speakers are just like, “Oh, well, I’m just gonna keep doing what I’m doing” because it’s not that they’re being shamed out of speaking the language entirely, which is a much different kind of stakes when you have these two different linguistic situations going on.

Hanna-Máret: Exactly, yeah.

Gretchen: One of the things that maybe can contribute to younger people having the opportunity to speak the language or practice a language is this thing that you’ve called “language showers,” which I think is a cute name.

Hanna-Máret: I’m so glad that you like the name. It’s not me. I didn’t come up with that. I saw some newspaper articles in Sweden about language activities for immigrated children, so I felt that was the best way to describe what we were doing.

Gretchen: Maybe we can explain what a “language shower” is.

Hanna-Máret: It’s very important to say that language showers are not the same as full immersion programmes in Canada that you were speaking about earlier, and they are not, also, the same as language nests in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

Gretchen: Those full immersion programmes would be more of a “language bath” where you’re fully surrounded by the language?

Hanna-Máret: Exactly. And for long, long periods of time. There is a continuity in that. But language showers, they are all sorts of short-term language immersion activities. They can be language camps and other occasions that aim at creating an environment for the learners where at least the leaders used the target language of the showers. I’ve also seen that this practice has to be amended sometimes. If most of the learners are complete, new beginners. The long-term goal is to create new domains, additional domains, occasions and places and spaces where the target language, the Indigenous language, is heard and used all the time. That’s the goal.

Gretchen: But sometimes, the real-life situation is more complicated.

Hanna-Máret: Yeah, exactly. I’ve seen different examples. I’ve seen that when the language showers are very well planned and the leaders are linguistically skilled and good with the leaners, and when there is enough language support available in the environment, then the showers can truly function as additional engines in the revitalisation process. With “language support,” I mean all kinds of aids ranging from pictures and maps, colours, recordings, music, and film, so that you have every kind of support.

Gretchen: You’re getting more sources of input and examples beyond just what you’re seeing right now in the activity.

Hanna-Máret: Exactly. Because there are so many different levels in those learners. I’ve also seen situations where, for example, the protruding idea of the “orality” of Indigenous languages, while we only speak the language, it can lead to a situation where the learners have nothing else but the spoken word to lean on. Their learning is rather hindered or slowed down because they can only hear a language, and they don’t know anything, they don’t know the language before, and they get tired of listening to that. It’s those who already know how to speak and have some earlier knowledge of the language, they are supported by this kind of method, while the real beginners, they can actually, in some situations, feel quite outside and become very sullen.

Gretchen: That makes sense, yeah. You mentioned that some things need to be changed if most people are completely new beginners because, otherwise, they can feel this isolation.

Hanna-Máret: I think that there has to be a lot of support so that it becomes a language engine. Sometimes, these kinds of language showers, they end up becoming merely cultural meeting places where the language component gets lost on the way. I think that setting up a new language scene needs some really serious thought behind it to really function as a language strengthening domain, while the cultural scene can often be set up much quicker, so you need to really think about “How do we strengthen the language in this domain so that it doesn’t just become something else?”

Gretchen: Because if you just wanna do a cultural thing where you’re making traditional food or doing traditional cultural practices, I dunno, clothing or crafts or something like that, then that’s something you can do with or without the language.

Hanna-Máret: Yeah, and you could just use words and phrases that go together with that but then use the majority language most of the time. It would actually become more like, people do get to know the words, but if they are not actually going to use the language much more than that.

Gretchen: That makes sense. It seems like there’s a lot of scope for using language play as part of the language showers to have this relaxed environment for people.

Hanna-Máret: I think that there is a lot of support in earlier research on language and play for the positive effects of play and playfulness on children’s language learning and also their well being in the majority context. We don’t actually know so much about this when it comes to Indigenous contexts. I’m really glad to be part of an international research initiative. It’s called “NowPlay2.” It is led by Professor Shelley Stagg Peterson at OISE in Toronto, in Canada. Within that project, I’ve had the chance to collaborate with Sámi teachers and learners to really learn more about the effects of play and playfulness in our local, Indigenous Sámi context here in Sweden, and also, at the same time, learn about – there are 20 other Indigenous sites, also, that are part of this project. We are all the time learning how play can strengthen this.

Gretchen: That sounds really cool. We can link to that project in the show notes. You’re someone who’s working both in an academic context and also as a community member of the languages that you’re studying at the same time. How do you balance that insider-outsider situation?

Hanna-Máret: Well, I don’t think that I always manage to find the right balance right away, but I just kind of keep on adjusting my roles until they are, at least, in some kind of balance. I try to keep Shawn Wilson’s 2001 post about the relational accountability in my mind. That means that I am responsible and accountable for all relations to my research partners and participants. But I’m also accountable for the academy. I have to also think about their rules there. I actually get this question quite often. It’s almost a little bit provocative to me. Most researchers who study the use and structure of, let’s say, Swedish in Sweden or maybe English in Canada, they are probably also members of the same language community that they study. They are usually not asked about being an insider and outsider at the same time, although the same logic should, of course, apply to them. Instead, they just need to prove that they do ethical research and that they think about researcher positionality. I think the same should apply to me. I need to be aware of my positionality as a researcher, but the insider-outsider question, I think it should either be skipped, or it should be posed to everyone who is an academic and, at the same time, belongs to the certain community that they are studying.

Gretchen: Maybe asked to everybody to think about “What are the impacts of the research that you’re doing on the people that you’re doing them for?” I think of myself as an insider-outsider when it comes to doing internet linguistics because I was studying people using language on the internet, but I was also very much using language on the internet. For me, writing a pop linguistics book that people on the internet would find interesting to read was a way of being like, “Okay, how do I give back to this particular type of community even though internet people are not traditionally thought of as ‘Oh, this is a marginalised group’ or something like that?” But it is a group that I was studying while also being a part of. Finally, Hanna-Máret, it’s been so great to have you here on the podcast. If you could design a dream project related to Sámi linguistics, what would that be?

Hanna-Máret: Since I already work as a linguist in language education, I’m really lucky to get to do very many things that I might not always write academic papers about but that still matter for the language community and that I also enjoy doing. There are also a few papers that I’m working on at the moment, but most of them are then connected to research projects. If I get to talk about a dream project, then I think that I would really have this one big project in my dreams. It’s about supporting Sámi parents in their language choices and everyday language use. I really wish that I could find these substantial grants, big grants, to support language revitalisation at the grassroots level so that parents could, for example, use the whole year for intensive language studies. It would be so interesting to follow parents who have the opportunity to really take time off their jobs to study the language with the guidance of good teachers. I think that it would be a great development project, revitalisation project, alongside a really fascinating academic study. That would be my big dream study at the moment.

Gretchen: That sounds really cool.

[Music]

Gretchen: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode, go to lingthusiasm.com. You can listen to us on all the podcast platforms or lingthusiasm.com. You can get transcripts of every episode on lingthusiasm.com/transcripts. You can follow @lingthusiasm on all the social media sites. You can get scarves with lots of linguistics patterns on them including the International Phonetic Alphabet, branching tree diagrams, bouba and kiki, and our favourite esoteric Unicode symbols, plus other Lingthusiasm merch – like stickers that say, “Ask me about linguistics,” Gavagai rabbit t-shirts, aesthetic IPA posters and more – at lingthusiasm.com/merch.

Lauren’s social media and blog is Superlinguo. Links to my social media can be found at gretchenmcculloch.com. My blog is AllThingsLinguistic.com. My book about internet language is called Because Internet.

You can follow our guest, Dr. Hanna-Máret Outakoski, on her website which we’ll link to in the show notes.

Lingthusiasm is able to keep existing thanks to the support of our patrons. If you wanna get an extra Lingthusiasm episode to listen to every month, our entire archive of bonus episodes to listen to right now, or if you just wanna help keep the show running ad-free, go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm or follow the links from our website. Patrons can also get access to our Discord chatroom to talk to other linguistics fans and be the first to find out about new merch and other announcements. Recent bonus topics include the linguistics of kissing, linguist celebrities, and the results of our 2024 listener survey, including the name and rules of “Rock, Paper, Scissors,” a.k.a. “Paper, Scissors, Rock.” As a reminder, if you’re a patron at the Ling-thusiast tier or higher as of July 1, 2025, you’ll also get a snazzy Lingthusiasm logo sticker in the mail to help you find other linguistics fans to interact with.

Can’t afford to pledge? That’s okay, too. We also really appreciate it if you can recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone in your life who’s curious about language.

Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our Senior Producer is Claire Gawne, our Editorial Producer is Sarah Dopierala, our Production Assistant is Martha Tsutsui-Billins, our Editorial Assistant is Jon Kruk, and our Technical Editor is Leah Velleman. Our music is “Ancient City” by The Triangles.

Hanna-Máret: Stay lingthusiastic!

[Music]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blind people gesture (and why that’s kind of a big deal)

People who are blind from birth will gesture when they speak. I always like pointing out this fact when I teach classes on gesture, because it gives us an an interesting perspective on how we learn and use gestures. Until now I’ve mostly cited a 1998 paper from Jana Iverson and Susan Goldin-Meadow that analysed the gestures and speech of young blind people. Not only do blind people gesture, but the frequency and types of gestures they use does not appear to differ greatly from how sighted people gesture. If people learn gesture without ever seeing a gesture (and, most likely, never being shown), then there must be something about learning a language that means you get gestures as a bonus.

Blind people will even gesture when talking to other blind people, and sighted people will gesture when speaking on the phone - so we know that people don’t only gesture when they speak to someone who can see their gestures.

Earlier this year a new paper came out that adds to this story. Şeyda Özçalışkan, Ché Lucero and Susan Goldin-Meadow looked at the gestures of blind speakers of Turkish and English, to see if the *way* they gestured was different to sighted speakers of those languages. Some of the sighted speakers were blindfolded and others left able to see their conversation partner.

Turkish and English were chosen, because it has already been established that speakers of those languages consistently gesture differently when talking about videos of items moving. English speakers will be more likely to show the manner (e.g. ‘rolling’ or bouncing’) and trajectory (e.g. ‘left to right’, ‘downwards’) together in one gesture, and Turkish speakers will show these features as two separate gestures. This reflects the fact that English ‘roll down’ is one verbal clause, while in Turkish the equivalent would be yuvarlanarak iniyor, which translates as two verbs ‘rolling descending’.

Since we know that blind people do gesture, Özçalışkan’s team wanted to figure out if they gestured like other speakers of their language. Did the blind Turkish speakers separate the manner and trajectory of their gestures like their verbs? Did English speakers combine them? Of course, the standard methodology of showing videos wouldn’t work with blind participants, so the researchers built three dimensional models of events for people to feel before they discussed them.

The results showed that blind Turkish speakers gesture like their sighted counterparts, and the same for English speakers. All Turkish speakers gestured significantly differently from all English speakers, regardless of sightedness. This means that these particular gestural patterns are something that’s deeply linked to the grammatical properties of a language, and not something that we learn from looking at other speakers.

References

Jana M. Iverson & Susan Goldin-Meadow. 1998. Why people gesture when they speak. Nature, 396(6708), 228-228.

Şeyda Özçalışkan, Ché Lucero and Susan Goldin-Meadow. 2016. Is Seeing Gesture Necessary to Gesture Like a Native Speaker? Psychological Science 27(5) 737–747.

Asli Ozyurek & Sotaro Kita. 1999. Expressing manner and path in English and Turkish: Differences in speech, gesture, and conceptualization. In Twenty-first Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 507-512). Erlbaum.

84K notes

·

View notes

Text

my dealer: hey man i got this new strain called attic dialect you'll be zonked out of your gourd.

me: i don’t feel shit

15 minutes later

me: i swear those τs were σs two seconds ago

my buddy θάλαττα, pacing: the Athenians are lying to us

616 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love the word "also". I have more things to say

67K notes

·

View notes

Text

linguistics study: genderqueer / nonbinary Arabic speakers wanted!

Do you speak Arabic? Are you trans, nonbinary, genderqueer, gender fluid, or otherwise gender non-conforming?

Please consider taking this 9-question survey to help us create free materials for teaching Arabic.

Please share widely 💜 (Note from synticity: I'm sharing this survey from Kris Knisely on bsky!)

446 notes

·

View notes

Text

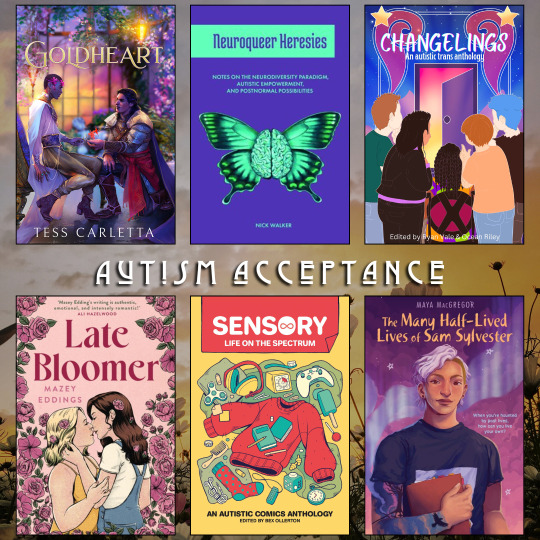

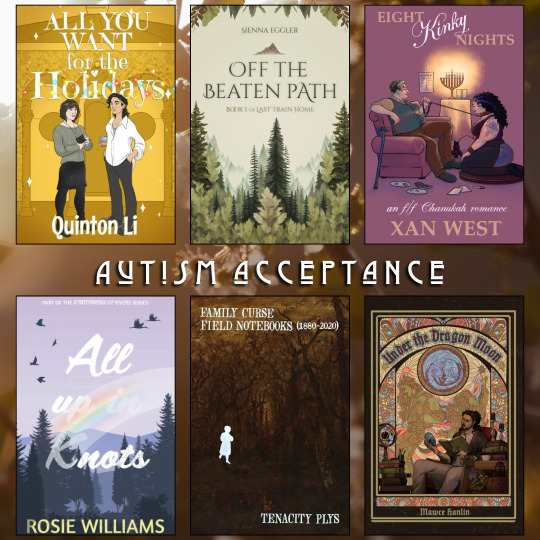

It's Autism Acceptance Month! We are past the time of awareness, it's time for acceptance. There have been so many great posts and book recommendations, it makes me so happy to see people sharing their favorite reads.

These are a good mix of books I want to read, and have read.

312 notes

·

View notes

Text

roadside calla lillies and a page from a book of advice for parents written by children. Yeah and life can be beautiful also

188 notes

·

View notes