Text

Something amazing

You want the turtle to see something amazing, so you drive her out to the field near Kitchener where the Mennonites have the hot-air balloon rides. You just plonk her (you think she’s a her? You should use they/them pronouns, but you kind of want the turtle to be female, to be, even, a high-femme reptile, something about the roundness of her shell, the tranquility of her little black eyes, it’s important to you), you plonk her in the passenger seat, where she walks around a bit, then settles. After a minute’s contemplation you reach over and fasten the seatbelt, for reasons of magic. You do so many things for reasons of magic lately: a seatbelt is a protection spell; an invoice is a prosperity spell. Is it working? It’s not; you’re floundering. But at least you have the turtle.

It takes nearly three hours to get to Kitchener. Flat grey highways give way to flat green fields, underlined by the fine flat dark line of the escarpment to your left. The turtle is too far down to see out the windshield, in the bucket seat, so you reach over and put her up on the dashboard. A tricky maneuver, as you’re not an experienced driver; you swerve onto the gravel, startling a lone chicken, but you right yourself. The turtle slides a little this way and that, retracts her head partway. When she settles, you see rolling hills under big grey Zeppelin clouds; a guy doing donuts in a parking lot in one of those black horse-drawn buggies with the spindly wheels, the horse prancing wildly, flecked with sweat; a circle of vultures in a grassy field, swaying, wings spread. You see marching lines of windmills, enormous, turning with a dreamy slowness. You see dots of floating colour, tears in the sky: hot air balloons.

As you park, as you cradle the turtle, now fully retracted, against your chest, as you make your way to the gap between hay bales that serves as a gate, as the balloons ripple and loom overhead, so much bigger than you expected, you remember how afraid of heights you are. Anything higher than the second step on a standard stepladder sings to you of the void. Some part of you knows that someday it will be your destiny to plummet from a high place. But this day, this excursion, isn’t about you. It’s about her: the turtle. You make the chucking noise that you sometimes use to lure her from her shell. It doesn’t work. Nothing ever does, except a proffered lettuce leaf, a partial strawberry. You have some shredded cabbage in the pocket of your cargo pants. You decide it would be best to get situated in a balloon, then lure her out with the cabbage once you’re good and high up there. You imagine what it will feel like, for her, to emerge from the comfy blackness of her shell to a mouthful of cabbage and an infinite vista. It will probably be really great.

Approaching the gate, you slip the turtle into the front pocket of your hoodie to avoid awkward questions. It turns out not to be necessary: the attendant who takes your money gazes past you with his pale blue eyes, the breeze stirring his straw-coloured hair, and tics his head to the side to indicate a balloon a little away from the others in the field. It is an intense, flaming orange, the kind of colour you need to inhale deeply while looking at in order to tolerate. It is turgid with gas, and its fiery shape strains upward, its colour cutting against the dark-grey bellies of the overhead clouds like a scalpel.

A teenage girl in a long dress and white cap, modest and judgemental, steals glances at your knuckle tattoos as she helps you into the wicker basket and directs you to the red pleather bench. When she unties the rope, you expect a giddy rush of sickness, but instead you feel a slow, dignified elevation, like riding upwards on a wooden escalator while a small brass band plays Pomp and Circumstance. Your finger traces the hole in the turtle’s shell where her right front foot is hiding, retracted. The wicker wall is as high as your chin. You peek over it. You are high enough to see the parking lot, your car and the attendants’ van and a rusted pickup truck with empty propane tanks and rope in the flatbed. They dwindle, not quickly. You look up at the clouds, which seem marginally closer. The girl is opposite you, fiddling with the red knob on one of the propane canisters. There’s a hissing, whether of wind through wicker or leaking propane you don’t know. It’s time, you think.

Cradling her with your left hand, you slip your right out and reach it down to your leg pocket, pull out a fistful of cabbage shreds, starting to brown around the edges. Carefully, you draw her out of your hoodie pocket with your left hand, and rest the belly of her shell against the wide wicker rim of the basket. You extend a shred of cabbage in front of her, in front of the shell-hole where her head resides.

You wait. Her shell is so pretty: a dark waxy green like old jade. It’s panelled, of course, the grout between the tiles of its top a pale yellow-green that looks white by comparison; and there’s a decoration of lipstick-red arcs around its rim, a series of patterned tiles like something you’ve seen on Greek pottery, an imprecise geometry, like letters generated by an AI. The bottom of her shell is almost gaudy by comparison with the top. Up close now, you can just see the edges of it, red and yellow and green in a pattern like leopard skin. You crush the edge of the cabbage shred with your fingernail so she can smell it better.

Slowly, her snout emerges, craggy and black like a mountain turned on its side. You pull the cabbage away a little, luring her out. You can see her nostrils now, high and half-hidden in a peak at the top of her face. A little further, and you can make out her eye, bright green like the fields, bisected horizontally by an irregular black line that gives her, you think, a rakish, outlaw appearance. Further still, and the striped, snakey extent of her neck emerges. Her jaws open: so cute! And then she is ruminating on a mouthful of cabbage, looking out over the world, which is now, you realize, looking at it through her eyes, much further down, you are much higher up, you can see squares of dark green and bright green, almost neon against the blackening clouds, turning bluer in the distance, spikes of windmills here and there, turning their arms in loose breezy inorganic loops, all the way to Lake Huron, gleaming like dull platinum, from up here, behind the turtle, the world is beautiful,

0 notes

Text

Syllogism

Him: I found myself wondering what that turtle was thinking, and that was when I realized: I’m super high

Me: I wonder what turtles are thinking *all the time*

Him: Oh, so you’re like a really strong empath?

Me [suddenly apprehending the lurid death-spiral I’ll go into when my toxic, self-annihilating empathy encounters his wholesome, life-affirming sociopathy]: I just fuggin’ love turtles, man :D

0 notes

Text

Olivia Upstate

BUT TO GET BACK TO THE TURTLES: What if Olivia (shall we posit that all female turtles are named Olivia? No, we must insist on their individuality, it’s monstrous to reduce them like that, even if we don’t know them enough to suss their differences, whether or not it’s damaging to them, it damages us,

What if our Olivia, instead of living in the weird crushed-brick ecosystem of the Leslie Spit, was there instead in that turtle pond on that property in the Catskills? What if, in her lifetime, the turtle pond dried up? Where would Olivia go? Would she just die? How would it feel? It doesn’t bear thinking about, not yet, we’ll have to work our way around to that saddest of songs.

So let’s talk about something more pleasant: the early days of Olivia’s life, when water was plentiful, when Jacob and Evan and Sarah and the kids all hung out together on the log, when at night one tipped oneself into the water and skimmed under the surface over to the smooth rock, where one slept, head just emerging from shell, out of reach of weasel or marten, at the bottom of a soft lap of earth, sheltered under the round shoulders of those old mountains, in the true dark far from any town, stars (finally) wheeling overhead, a white pulsing river of stars wheeling overhead, poking your head out just a bit from the pitch-black tranquility of your shell to watch the stars wheel.

0 notes

Text

Memory (The False Cousin)

I will try, now, to reconstruct the day (was it a weekend? Did I stay over?) at the house with the erstwhile turtle pond, because I had the thought that I may have swum in the river, and now I can’t remember. The river: broad, hip-deep, smooth, green, fast-flowing over big, smooth boulders like cattle. Little frills of white water. Looking down from a high rock at my cousins (is this right? Almost certainly not), at my cousins, romping with their kids (were they born yet? I don’t think so), in any case, an image of my cousin Johnny, looking up from an eddying green pool where he lounged against a rock, pale-skinned, round-faced, dark-bearded, laughing perennially with his square white teeth, his consciousness of being the one person who could reliably make this a good time for everyone involved, myself included. If not for him, I would have succumbed to the pallid demureness of the strange women from the other side of the family; I wouldn’t have shucked off my wedding-guest dress (berry-red, with flowers), to reveal my worn, workmanlike black bathing suit for a moment before I scrambled down the smooth river rocks, feet gripping, then slid into the shocking muscular icy green river, rocks slippery underfoot. It was August but not hot outside, overcast with the kind of milky sky I associate with childhood and boredom. I had a feeling of being on display, a little, under the mild, disapproving eyes of the women of the other side of the family, of self-consciously joking with Johnny and his (yet unborn) kids, his (possibly yet unmet) wife, to offset my discomfort at their scrutiny.

This is the thing: none of this is real, or very little of it. Likely, we didn’t stay overnight; likely, I didn’t swim, or even bring a bathing suit. I don’t think Johnny was even at that wedding; I have probably never seen him lounging against a broad rock in a hip-deep pool in a green river, his black body hair plastered in tight circles on his white, goosebumped skin.

What is real, what I remember for sure: the cold lithe persistent green of the river, and later, the soft disapproving turn of the pretty neck of one of the more distant cousins.

But so then: if I can “remember” this quite vividly, knowing that it’s false, what about the rest of my memories? What about everything I think about myself and everyone else I know?

0 notes

Text

The Hanged Man

Sometimes, like when you’re in a full-body cast, there’s nothing you can do but sit and think, in an unpleasant, morphine-modulated way, at least until the nurse comes to feed you a couple of spoonfuls of jello, which are so puckeringly intense and flavourful, you don’t remember jello ever tasting like this before except maybe in your earliest childhood, you are drifting into a raspberry reverie until the memory jolts you upright: that jello is made from horses’ hooves, and there you are, back on the battlefield, hooves pounding and churning up the muck all around you. You decide to wake up, to follow the thought about hooves wherever it leads. In fact, a distant relative of yours, by marriage, invented jello, boiling hooves in a small white shed in the Catskill mountains. It made the family a fortune, which it then lost, all but the shed and the house next to it. You visited the shed once, and the house, which was charming beyond belief, every banister and armrest carved with animal faces by generations of children; and you fell in love, briefly but intensely, with an older woman, your cousin’s husband’s mother, whose house it was. You are not accustomed to loving people on sight. In your experience, it’s a lot of work to love most people, and yet there you were, and her too, in the still silvery afternoon light of the front room, her long dress and cardigan and dark-silver hair tied back: smitten. And yet you can’t remember what you talked about; just the memory of talking, so easily, for once. A mystery. You never saw her again after that day, and she died last year, and after she died you found out that she had asked after you every time she spoke to your cousin, just as you’d thought about her, more often than seemed sensible, all the time, really, for twenty-odd years; a mystery. There was a pond there, in a green field, that sometimes had turtles in it; according to the family, sometimes the pond dried up; you wondered where the turtles would go. Time will pass, and your body-cast will come off, in pieces, and slowly your thin white rice-noodle limbs will plump up and become pink and limber, if all goes well; at least, that’s the story the nurses tell you as they spoon you full.

0 notes

Text

The Ten of Cups

Happy turtles are all alike. Unhappy turtles are each unhappy in their own way.

So let’s think about the happy turtles, because who wants to fret about the boring lives of unhappy turtles? Not this turtle writer. What does it take to make a turtle happy? Not the sense of well-being, fruition, fulfillment, security or affection, or even a very good dinner — but the sudden illumination?

First, you’re going to ask me: are we sure turtles can be happy? In that way?

And then I’m going to answer, emphatically: Yes! Yes, we are sure. Not just turtles, but all reptiles, all animals, all living things: dandelions, pillbugs, viruses, gangrene. All of them (all of us) can be happy, and furthermore, they all want to be happy, they have an appetite for it, a voracious one. In fact, I’m going to go out on a limb and say that it’s one definition of life: anything that has a voracious appetite for happiness.

You: Whoa, okay, calm down

Me: ATTENTION SCIENTISTS! I HAVE DECLARED A NEW DEFINITION OF LIFE: A VORACIOUS APPETITE FOR HAPPINESS

You: Um, okay, so but what would turtle happiness look like?

Me: Now we’re cooking with gas!! I suspect it would have a lot to do with humidity levels

You:

Me: Okay, let’s say you’re a turtle. We’re going to name you... see, I have this impulse to name you something kind of cute and frumpy like Henrietta, but I suspect that you, a turtle, would prefer a pretty, contemporary kind of a name, like Zoe, or Olivia. And since we’re trying to make you, a turtle, happy, let’s call you... Olivia. And let’s say that you live in a pond on the Leslie Spit, so your living conditions are pretty good? Better than being in some kid’s tiny aquarium? But not ideal, i.e. there are construction vehicles rumbling by you giving off diesel fumes and like asbestos dust during the week, and then on the weekend people in Spandex come along and try to take your picture for Instagram.

On the other hand, Olivia, you’ve got a pretty nice pond, sufficiently deep to last out the season, some choice algae, a couple of good logs to sit on in the sun, some tall grass to lurk amongst. The companionship of your fellow turtles. Sun, rain, frogs, weasels, the moon and the stars (oh, Olivia, but you live in the city’s light dome and I don’t know how good your vision is; you may never see stars? Does science know if turtles can see stars?)

In any case, stars or no stars: you are sunning yourself, on the log, let’s say, having just eaten a nice meal of... insects and algae? Is that correct? Dragonflies skim across the pond’s surface. A weasel rustles in the tall grass on the other side of the pond, but you haven’t nested yet, let alone laid eggs, so while wary, you’re not alarmed. A steady stream of people in Lycra crunch down the gravel path to take selfies with you. The spring sun is starting to warm your shell. You stretch out your neck, close your turtle eyes, feel the log sway as Jacob the turtle clambers onto it after a refreshing swim

There is nothing here to be unhappy about, and so you are

Your fundamental nature is to be

Happy, you’re happy, turtles know no neuroses

Can this be? Is it possible to be alive, to crave happiness, and yet to know no neuroses?

0 notes

Photo

(via GIPHY)

Wondering about the ethics of sharing this private moment, but it’s to the point.

Also, in the future, this will be me, a tortoise, caught on video trying to mate with a croc, and maybe this now is the most I’ll ever know about it, so maybe it’s okay.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Hermit

Some of the stories in this blog will involve drawing a tarot card, and applying it to turtles in some way.

You live in a studio apartment above a defunct dry cleaners near the university. It’s lit by two French doors that open onto a rusted Juliet balcony that hangs over the now-inaccurate dry cleaners’ sign. You have a kitchenette, a breakfast island, a captain’s bed with a chest of drawers underneath, a little desk tucked into an alcove, a loveseat, a bookshelf, a monstera plant. There’s a closet for any of your clothes that won’t fit under the bed, an alcove to hang your coat, a shelf for your boots. The bathroom has a tub, and black tiles. It’s nice. It’s all you need.

You come home after work and climb the stairs. More often than not, you splay yourself across the bed. You spent a lot of money on the bed; the mattress is like a mattress in a good hotel. You felt obscurely, when you moved here, that this would be important, and it is. After a while, you get up and heat up the soup you’ve left in the fridge, and then you go to the couch and pick up your tools. In the summer, you open the doors; the voices of passing students and the smell of hot oil from the fish-and-chips place next door filter in. Between the roof of the house across the street and the sprawling maple next to it, you can count three stars.

You could have people over, but you don’t. Instead, you read, and sometimes watch movies, and carve turtles out of wood. You are going to grow old this way, alone, which makes you sad at times. At other times, you reflect that your turtles are objects of immense power and value, and that makes you feel better.

You paint the turtles, once carved, with red lacquer, then rub gold dust on them, then paint them again with black lacquer, then buff them with sandpaper or dab at them with paint thinner so that they reveal patches of colour. You carve the head and legs and hang them from secret hooks within the shells so that they bob and move about independently. You murmur incantations over the turtles, things you’ve made up for the purpose and polished over time. An example of a turtle incantation might be:

Luminous reptile!

Emblem of certitude!

Stay gold.

You imbue each turtle with magical intentions: one turtle may possess the quality of strong intuition, another, inner strength. You imagine, firmly, that this will give them power over the fates of the people who wind up owning them. Every Sunday in the summer you take a wooden chest of turtles down to Kensington Market, where you lay them out on a rug next to the guy with the ayahuasca-inspired neon cloth paintings of tree frogs. At first, the guy (Carlos is his name) viewed you with suspicion, as competition; but eventually it became clear that your interests meshed, that you were symbionts. In fact, Carlos eventually invited you to an ayahuasca ceremony at his place, and you accepted.

You’d heard that ayahuasca was capable of bringing about immense transformations in people, imparting clarity of purpose in those who had previously only drifted through life. The prospect filled you with a faint, quivering hope. During the ceremony, you vomited into a metal bowl for over an hour; then, a puma appeared, crouched on the hand-painted carpet in Carlos’s living room. It looked into your eyes, and you understood that living alone and carving turtles was in fact the correct path for you; and that you were going to die of stomach cancer before you reached 60 anyway.

This sounds depressing, when I write it down like this, but to you it truly felt like a weight lifted from your shoulders. You had worried so much, over the years, about what path you should take through life, and here it turned out that you’d been on it all along, that you couldn’t have done otherwise, that everything was soothingly foreordained, written in strong black ink in nice calligraphy in a book with gold dust rubbed along its fore-edge. You could sink happily into your loveseat at the end of the working day (you work in the marketing department for a midsize pharmaceutical company) and bring out your carving tools, your brushes, your miniature pliers and your sandpaper and buffing cloths, and do exactly what the Universe intended you to do.

In fact, this knowledge sat so softly with you, sank into your bones so sweetly and completely, that you became, privately, and still are now, a kind of saint. You radiate kindness and contentment. You leave a trail of soft blue certitude wherever you go, and passersby inhale it and are better. And when you are dying, at 56, of pneumonia following treatment for stomach cancer, you will be taken into a hospice for the lonely and indigent, and treated with such loving care by the people there that you will almost regret taking your leave of life.

0 notes

Text

Turtles

You see them seldom: in Edwards Gardens, down in the water feature at the south end of the greenhouse, stacked up by the mill-wheel; or on the Leslie Spit, spread out on a swamp-log like raisins on peanut butter on a celery stick on a sultry August afternoon. The ones you see are as flat as dollars, oblong and characterless. Or not characterless: pretty, like works of art; if they were inanimate, they would be objects of power. But anyway you suppose that what you wanted to write about, actually, was tortoises, which you see never, except for in videos, online, embedded in people’s feeds, in which they appear to be creatures of pure pleasure: fucking, with avid squeaks, each other, or a bicycle helmet, or a football; eating strawberries, bleary eyes glinting. Their wizened faces give you a titch of hope, that it might not all be over for you yet, that there might be some pleasure left, however ungainly.

0 notes

Text

Turtles

For now, this blog is going to be fiction about turtles.

0 notes

Photo

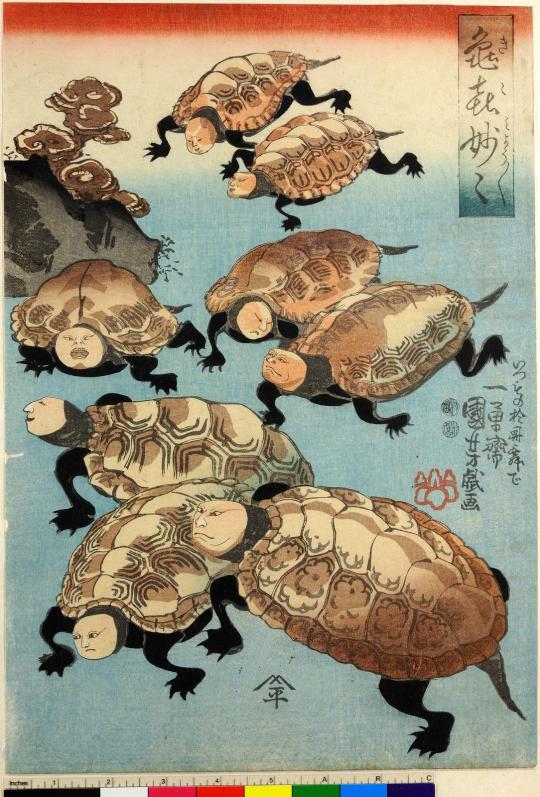

Strange and Marvellous Turtles of Happiness

British Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

0 notes

Text

980 lbs

I’m thinking about the 980-pound man. There was a story around Facebook recently about him, and the surgery that he’s getting to remove 100 pounds of loose skin now that, due to gastric bypass surgery, he’s lost 600-odd pounds.

I’m thinking: 980 seems like a very precise number. He said, in the article, that at his heaviest he just lay in bed all day thinking about things to eat. But he must have weighed himself, too. On a special scale, no less. Did he go to a doctor? How do we know he was not 1,000 pounds? I don’t mean to make light of his situation. But I’m curious about the mechanics of it, and the semantics. And how did he decide to change, to stop? And how did he physically do all the things he had to do to arrange for the surgery, and how did he keep from just falling back into bed?

I’m thinking, also: he had a cruel father, the article said, and a female relative who molested him repeatedly when he was a kid. That’s why he stayed in bed for years and only thought about food. I can see that. My own little store of traumas often paralyses me, and I’m sure they’re nowhere close to his. I can imagine this laxity, this lassitude, stealing over you, this numbing soothing nothing; sometimes leaving the house feels like too much, and the more you give in to that feeling the stronger it gets.

I sometimes think about what if we are all one consciousness snaking its way non-sequentially through each person’s head ; and what if when we die we just become another person; and what if eventually we are all each other, and that is what God is - the sum of all of our experiences of life? Which would mean that eventually I will be the 980-pound man, unless I already have been. Eventually I will know what that is like, just like eventually I will know what it is like to be you, just like you will eventually know what it is like to be me. I find some satisfaction in this thought: I so want to know what it is like to be you. I so want you to know what it is like to be me.

0 notes

Text

Just testing.

Just testing the app now here. Just testing the app.

0 notes

Text

About the Cats

So, I love the cats. There are two of them, brown tabbies, about nine months old. And when I say that I love them, I do mean that I love them in exactly the sobbing, slightly unhinged way that you might be thinking, especially if you don’t have a thing about cats and want to make fun of me. I love them in a hysterical way that makes me not mind when they wake me up in the middle of the night to show me that they’ve tucked a toy dead mouse between my pillow and my neck.

A couple of things follow from this. The first is about love. This is something I worry about: what does it mean to say I love an animal (or two animals)? The kind of love I mean boils down to a sensation, located near the top of my liver and radiating out to the insides of my elbows, of wanting to squeeze. But obviously this is not a desire I could ever indulge very much; which raises another point: how much of this love is actually about the cats, and how much is about my enjoyment of the sensation of wanting to squeeze the cats? How much, in other words, is predicated on my respect for the cats’ own sovereign feelings, and how much is simple self-indulgence?

This seems like a meaningless question: who knows? Who cares? But it has practical, and kind of disturbing, implications. Because if my feeling about the cats is really about the cats, then I have to start thinking about what the cats themselves might want, and not what I want for myself, or for the cats.

For instance: we’ve started letting them outside (they want so badly to be outside); so I bought them reflective collars and stuck them around their necks. They hated them, naturally, and after an hour or so I took them off; but now, I won’t let them out after sunset, which is something they want.

Fine, fair enough: I understand about the cement mixers roaring up the street to the nascent monster home on the corner, probably better than they do. But I keep sensing this ennui in them, too, even when they get outside: a kind of Peggy Lee-ish shrug. And yes, babies, that is all there is: our neighbourhood doesn’t boast a lot of rats, or songbirds for that matter, and the part of your lives where you slip down the alley with a random assortment of Toms: we cut that tendency out of you before you knew you had it. (That’s melodramatic; it wasn’t us, it was the vet.) And those kittens you’ll never have, and the mother you left before you were ready (not our fault, but still): all that affection has nowhere to go now but to us. Right?

So. What is this thing called love?

…

A thought: a lot of this is projection. My friend’s vet told her that cats normally sleep sixteen to twenty hours per day. So that’s not ennui, it’s just the way they are. (But do feral cats sleep that much?)

So what’s under consideration is my own ennui, my own sense (after my equivalent of a quick sniff around the neighbour’s compost bin and a pounce or two on a dopey late-August wasp) that there should be more to life than this. And could this be about my decision not to have children? (I have decided this, because I would most likely be the kind of mother who would fret herself into a helpless weepy depression over, say, toilet training.) And is my love for the cats a redirection of my dammed-up love for my nonexistent children, a mirror of their redirected love for me? A sort of Panama or James Bay love. And how much of love in general is like that? Going where it goes because it needs to go somewhere?

0 notes

Text

Having reached the age where October is unacceptably metaphorical, I choose to ignore the weather.

0 notes

Photo

To be clear, I don't hate nature. I just don't trust it. All those trees.

0 notes