Text

Recent listening—

Julia Holter, Aviary (2018)

I can’t recall in recent memory feeling as intensely about a piece of music as I did when I listened to the opening track of this album, “Turn The Lights On”, for the first time. It is a magnificent cacophony. The violence with which it struck me brought me the satisfaction of finding something which I had been looking for for a long time. And while nothing on the rest of the album comes close to the joyous recklessness of the opener, there are subtler pleasures to be found. It’s highly apparent that she’s incredibly well musically educated but the playfulness of her explorations is anything but academic. It’s full of character, and shamelessly curious. It seems, to me, to be her most significant work to date. It’s very much grown from each of her previous works, but especially from Tragedy, her first, her roughest and most experimental, and from Have You In My Wilderness, her latest and most polished. At 90 minutes, it’s an impressive monument. It’s at times immediate and at others impenetrable, but never so much that you want to stop listening.

Radiohead, The King of Limbs (2011)

There was a time, not so long ago, when I was completely addicted to this album. I could not listen to anything else for three days or so. Along with In Rainbows, this is one of Radiohead's most unified albums—in texture, theme, flow, and general atmosphere. It's surprising that their most danceable album is also one of their most nourishing. The instrumentation is sparse, the production low-key, and the form meditative. Each track unfolds with a patient ease, without force, grounded by the supple line of Colin's base and the metronomic pace of Phil's beat. While Thom croons above, the middle ground is inhabited by images unresolved that come and go, alien and fleeting but profound in their imprint. This album is rather unfairly maligned. It’s detractors claim it to be cold and ineffective. But they miss the subtlety with which so much blooms from so little. There is plenty of life to be found in these supple forests.

Bill Evans and Jim Hall, Undercurrent (1962)

It's quite wonderful that two people can make such a world of sound entirely unto themselves. It's a fragile thing, and you can hear its fragility in the catching breaths lying here and there, in the sensitivity of the interplay between the two, and in the sense that without one the other would be nothing. Smaller ensembles are the ones that most inspire me to play. I want to be part of the creation of worlds like these, to inhabit them as they do, and to fill them with my own music, my own voice. I listen and I am comforted by the fact that beauty such as this is possible.

Yo La Tengo, I Can Hear the Heart Beating as One (1997)

This album has appeared on my site before. Half a year ago (the last time I posted properly) I would have balked at the thought of writing about the same album twice because I saw it as a cheap way to fill up words by talking about something you’ve already talked about before. And writing’s meant to be hard, right? But I have changed since then. I could say the same thing about any arbitrary six month period in my life. When you change, the meanings of the things around you also change. The world changes to reflect a world of change in you. Six months ago I thought that “Autumn Sweater” was a perfect song. To me it represented feelings that I knew I had not understood yet, and yet I had idealised them to the point where they felt that they somehow belonged to me. Much of the music I listened to was like this. They were not my emotions, but I stole them anyway. “Autumn Sweater” is a love song, and I had stolen its love. To me it felt like vulnerability, like innocent desire, and like a warm blanket, and I thought, this must be what love is. Then I remembered that it wasn’t mine, and the loneliness came back, stronger than before. I would wonder what it would be like to feel like how the song feels, to feel as cosy in the embrace of another as I did in the embrace of the sound. I would wonder what it would be like to feel an affection for someone as pure as the affection in the music, and despair at the futility of finding her. But despite this there was sweetness in the bitterness, and this was why I thought it was a perfect song. I still think it’s a perfect song. So what is the difference between now and then? It’s that the love is now mine, and that there’s no more bitterness. It’s that I have found her.

Johannes Brahms, Clarinet Quintet, Op. 115 (1891)

On my second day in Vienna the sky didn't know whether to rain or to snow. When I entered the main gates of the Zentralfriedhof it had decided on somewhere in between, and as the sleet coursed into my coat, Brahms's First coursed into my ears. I was in search of him. I found Beethoven first, and then Schubert, and I gave them time, thinking how fitting it was that they lay next to each other. Brahms was around the corner, obscured from the main clearing by a tree. In its shelter I stood before him. I listened to the last movement of his last orchestral work, the Finale-Passacaglia of the Fourth Symphony. I was deeply moved. I've probably spent more time listening to and playing his music than I have of any other composer, artist, or band. I've felt his music in my ears and under my fingers, in my breath and in my chest. I've read it like a novel, taken it like bread. And now, my eyes have lain where he lies.

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yesterday’s new acquisitions from the Daylesford Mill Markets. Ulysses and the Murakami I’ve read before. The latter will sit fittingly beside my copy of A Wild Sheep Chase, as will the Hemingway alongside my copy of Death in the Afternoon.

8 notes

·

View notes

Quote

There’s a light in the wings, hits the system of strings,

From the side, where they swing —

See the wires, the wires, the wires,

And the articulation in our elbows and knees,

Makes us buckle;

We couple in endless increase,

As the audience admires.

And the little white dove,

Made with love, made with love;

Made with glue, and a glove, and some pliers,

Swings a low sickle arc, from its perch in the dark:

Settle down, settle down, my desire.

And the moment I slept, I was swept up in a terrible tremor,

Though no longer bereft, how I shook! And I couldn't remember,

Then the furthermost shake drove a murthering stake in,

And cleft me right down through my center,

And I shouldn't say so, but I knew that it was then, or never.

...

Then the slow lip of fire moves across the prairie with precision,

While, somewhere, with your pliers and glue, you make your first incision,

And in a moment of almost-unbearable vision,

Doubled over with the hunger of lions,

Hold me close, cooed the dove,

Who was stuffed, now, with sawdust and diamonds.

Joanna Newsom, “Sawdust and Diamonds”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recent listening—

Bon Iver, For Emma, Forever Ago (2007)

It’s funny that, despite all the other fantasies I longed and hoped for, I wouldn’t change a thing. There are things I could have said, but didn’t, and the fact that I didn’t is testament to that had I said them, I would have broken something very fragile and precious. And the things I did say—that giddy outpouring before parting—I could not be happier with. You opened a closed soul, and, leaving, you leave me not desolate, but hopeful. How wrong Mr. Vernon was, in saying: “Emma is a place you get stuck in. Emma is a pain you can’t erase.” Perhaps, in weak moments, I succumbed to the words—before waking to my stupidity and realising that they only belonged to my incongruous fantasies. Our reality was fleeting but joyful. It was youthful, tender, painless. Said Vernon: “Emma’s not a person.” Oh but she is.

Igor Stravinsky, Concerto in E-flat—“Dumbarton Oaks” (1938)

Yes, I think this is exceptionally pleasant to listen to. Yes, this is a subjective statement. But I also think that by listening to this the right way anyone can find it pleasant. You simply cannot say the same about Schoenberg. Nor Le sacre. What this music should sound like, to give a visual analogy, is like a canvas that combines the geometry of a Picasso with the palette of a Mondrian; a lively, enigmatic Expressionism founded on a hyper-concise mathematical structure—and yet static imagery does not do it justice, for, particularly in the first and last movements, there is a continual sense of purposeful motion, a subtle perpetuum mobile that rises to the fore in the final minutes of the finale—this incredibly vital forward impetus is one and the same with that with which the Danse de la terre hurtles toward the end of the first act of Le sacre du printemps.

Beach House, 7 (2018)

In the same way that you’d be wrong but not entirely unreasonable in saying that Bruckner wrote the same symphony nine times, you might be forgiven for saying that Beach House have released the same album seven times. Unfortunately, the analogy doesn’t go much further past both having a penchant for slow-moving textural swaths. Did you expect to be surprised by 7? More importantly, did you want to be? I’m tiring a lot of the aesthetic they so reliably offer, but should I ever again desire stuff of the sort, I know exactly where to go and I know exactly what I’ll get. At this point, though, there’s little use in keeping 7 on my phone.

Courtney Barnett, Tell Me How You Really Feel (2018)

Gone is the Sprechstimme of the double EP and Sometimes I Sit. Gone is the Courtney of old. “I’ll be what you want / when you want it / But I’ll never be what you need” says she on “City Looks Pretty”. Ironic that what was delivered was not what was wanted but that which was needed—artistically, spiritually.

Nick Drake, Pink Moon (1972)

Autumnal music for autumnal moods. Nourishes aching souls. It is by far the bleakest of his works, the loneliest, the most tragic. It is also, in a sense, the warmest, the most internally radiant of the three. How can such polarising qualities reconcile themselves in a 28-minute work by a 23-year-old man? Bittersweet does not do the emotion justice—no, it cannot be captured in words, only in the songs of an artist that first shunned audiences, then the world altogether, and in so doing, wrought a tale of the utmost passion and empathy that despite this was delivered without the least gesture or contrivance. He is both singular and universal.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recent listening—

György Ligeti, String Quartet No. 1 (1954)

Contains reminisces of: D-S-C-H, B-A-C-H, certain elements of Bartók, certain elements of Stravinsky (Russian period), and (what was most interesting to me) the Bagatelles for wind quintet (or to be more correct the Musica ricercata). What do these mean? Is it more than a vegetative recognition of things we know? Yes—so long as we give it meaning. This ‘voice’ was one of Ligeti’s earlier answers to the question: Whither music if not total serialism? It had to be individualistic and unprecedented whilst steering away from the uncompromising cerebralism of Webern and Boulez—hence, the dissonant Hungarian style, combining the pagan rhythmic ingenuity of early period Stravinsky with the dissonant stasis that was characteristic of Bartók. As for the B-A-C-H, I think it’s less so a deliberate reference and more so a statistical reflection of that the B-A-C-H/D-S-C-H melodic contour is probably the most interesting permutation of a four-note motif, shape-wise.

Johannes Brahms, Ein deutsches Requiem (1868)

This is a vastly different Brahms to the one that premiered the First Symphony eight years later, let alone to the Brahms that penned the late masterworks of the Third and Fourth. There are stretches in the 6th and 7th movements where I begin to see where his detractors are coming from, those that complain that he is laboured and overly heavy. It is an odd, non-absolute form for Brahms to be working in, and this is where some of the structural awkwardness comes from; he did not have complete reign over the form since much of it was prescribed by the text. But Brahms is Brahms, and if you’ve played the four symphonies to exhaustion and you’re looking for more, this is where you’ll find it.

Unsuk Chin, Šu (2009)

Now, more than ever, composers exploit timbre and texture as a primary means through which to convey their craftsmanship to the listener. Gone are the days when this was done through harmonic invention or formal experimentation. Listeners of aggressively contemporary music are not expected to follow a work’s internal logic for to do so requires the recognition of gestures and the subsequent connecting of them—but by design the listener does not recognise anything because if something is recognisable then it is too easy. It is trite. The listener must be contented with momentary sensations, impressions of the present and of the vicinity of the present, in other words the feel of the music, the colour—which of course is governed by timbre and texture. Unsuk Chin is a master of these elements. In Šu, especially, there is a constant sense of ebb and flow, a primeval foreboding and suspicion that this music lies at the intersection of two powerful otherworldly forces in a violent tug-of-war, that shimmering moments of peace only represent a forceful and dynamic equilibrium between unknowable alien entities. These notions are conjured by such exotica as: a thunder sheet, the bin-sasara, mouth organs, Javanese gongs, and, of course, the sheng, which at this year’s Metropolis New Music Festival was played by master craftsman of performance Wu Wei.

My Bloody Valentine, m b v (2013)

It’s been said many times before but this is how I feel and I think this is how you’re supposed to feel when hearing this music: it’s music that you want crawl inside, that you want to wrap around yourself like a winter blanket. It’s albums like these that are timeless, because they convey not ideas, not facts, which are liable to change over one’s life, but feelings, states of mind, and despite however hard we may try, these are the things that we return to, the things that come hurtling back to us when most we need them. Of course, Loveless is timeless for this and another reason, that of fame. m b v is content with belonging in the hearts of fewer—but those who choose it have more to receive.

Olivier Messiaen, Des canyons aux étoiles... (1974)

There is a distinctive characteristic about the dissonances that Messiaen uses. If there was a colour scale of the characteristic dissonances of major composers, from dark to bright, with Ligeti and Bartók on the extreme left (dark), Schoenberg and Berg nearby, Mahler and Wagner still left-ish, Stravinsky sort of all over the place, Webern and Feldman at zero, Debussy and Ravel slightly right (bright), and middle period Stravinsky fairly right—Messiaen would lie to the extreme right, point being that his dissonances shimmer, they are potent with electricity, of a piercing light of a spirituality so pure and so joyous, with an openness and love that Teutonic dissonance could never manage. This is not to say that it is easier music. But perhaps it is more rewarding, emotionally. Over it’s 90-minute span Des canyons aux étoiles... contains a handful of unabashed major triads. They are few and far between. They only arrive after you, the listener, have earned them, and when you hear them, you may feel the ground shake.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recent listening—

Gustav Mahler, Symphony No. 10 (1910—unfinished)

I am not philosophically qualified to deal with the multitude of musico-literary questions posed by either side of the debate regarding the extent of Mahler’s authorship of the handful of extant completions that, together with their recordings, their critiques, their revisions, and their stories, form the intricately-woven, cosmopolitan, medium-crossing entity known as Mahler’s 10th. But I am philosophically awake enough to ask a few. For example: Is it to be performed abridged? Is it to be performed in full? Are the completions to be regarded as 'full'? How much authorship do we ascribe to Deryck Cooke, or to Rudolf Barshai? And how much is left to Mahler? In the fourth and fifth movements, how much Mahler is there? And what would be preferable between: a completion that adds nothing beyond the unfinished manuscript and a completion that fills in the short score’s gaps with its best approximation of Mahlerian harmony, counterpoint, orchestration, and textural effect? For answers to these and more I direct you to this superlative survey from Tony Duggan. And also to this recording of Cooke III. But any other will do, of any other completion, for hear it once and you will know: it must be heard. And that means all five movements. While it remains a veiled experience, particularly in the musicological thickets of the fourth and fifth movements, its impression is profoundly, distinctly Mahlerian. The veil is subtle—but close listening brings it into haunting focus. Certain passages in the second scherzo and in the finale’s allegro moderato are texturally malnourished. Passages where the completers were forced to resort to the recycling of earlier material fail to realise Mahler’s art of continuous variation, displayed at full might in the Ninth and even in the Tenth’s Adagio. And so what we have is not Mahler in the flesh but Mahler from the grave, his wisps—like the viola wisps of the work’s opening—imbuing every extant note with the passion and pain of his life—the Adagio’s F# subject and the cataclysmic dissonance at mm. 203-208, respectively—as a final shaken fist, furious and fading like the four-horn statement of the very opening’s viola theme in the dying minutes of the symphony. This moment continues to floor me. It is among the most powerful moments in all of Mahler, and it is also one of the most peculiar. In a sense, it is on the nose. Why would the master of continuous variation write so obvious and so literal a quotation in so obvious and so prominent a spot? There are many psycho-philosophical responses to this. All I know for sure is that I would rather be asking that question than this one: Had Mahler composed a Tenth, what would it have been like?

Ludwig van Beethoven, Große Fuge, op. 133 (1826)

And but so: did he mean it? For it is easy (and indeed unoriginal) to ascribe the op. 133′s tortured dissonances and density of sound to the composer’s own torture at his lack of sound. A simple rebuttal is that there are radical elements past these, e.g. the context-less tied quavers (and the peculiarity of tied quavers) in the introduction that teeter on the edge of complete isolation; the wildly confusing syncopation that manifests as complete incoherency of meter without intimate knowledge of the score; the unrelenting contrapuntal tumult of the first and second extended Allegro sections; or the comically insubstantial coda that does not fade out or end in glory so much as sheepishly, obligatorily resolve to a nominal B-flat major as if sweeping the last fifteen minutes violence under the carpet. These are characteristics of the work (rhythmic, structural) whose geneses would not have been affected by the inability to hear—at least three quarters of the works ‘progressive-ness’ can be unequivocally shown to have had nothing at all to do with deafness. To prove the same for the remainder can only be done for yourself by yourself. Listen to the perpetual harmonic momentum that sends the music hurtling down the pages, listen to each voice, each trajectory, the searing intensity of the work’s mode of propulsion: dissonace upon dissonance then momentary resolution then dissonance again and onward... and wonder whether any of this could ever have come about by mistake. Did he mean it? Every note.

Yo La Tengo, There’s a Riot Going On (2018)

At first glance it seemed like it would be impossible ever to take this seriously, on account of what is possibly the most lamentably uninspired album art I have ever seen. This is not an exaggeration. Just look at it. On one hand its unfortunate, because this is a good album, but on the other, it’s funny, because this is a good album and you should have known otherwise than to judge it by its cover (but again it really is godawful) because this is Yo La Tengo and have you ever heard a bad Yo La Tengo album? Or even a mediocre one? No. But have you ever heard a surprising Yo La Tengo album? Or a challenging one? ... No.

Dmitri Shostakovich, Symphony No. 9 in E-flat major (1945)

Less so a symphony and more so a suite—and yet this is at odds with the clearly symphonic conception of the form: The fast-slow-fast-slow-fast structuring of the movements, the sonata-allegro of the first, the scherzo in compound that the third somehow passes for, and likewise the fanfare and quasi-rondo in the fourth and fifth are all blatant signifiers of the Austro-German notion of the symphony. And in a classic Shostakovichian irony he, at the same time, evidences a blatant disregard for the Austro-German notion of development. For each idea is treated with a madman’s haste, is played twice or thrice without the least concern for variation, then passed on for some other ideas which are treated with equal disdain, and then all the ideas are played at end (separately, in succession) and this is somehow deemed an appropriate point to conclude the musical argument that had barely even begun. There is some interesting rhythmic development in the first and fifth but that’s about it, and even then, you’ve no chance of a breath to appreciate it since the fast movements are such frenetic whirlwinds. At worst, this symphony may be described as alternately skittish and languid. At best, it’s fun and concise, a woodwind extravaganza brimming with a barely contained energy. And it comes with an inherent immunity to any criticism it receives: As David Foster Wallace made clear in 1993′s E Unibus Pluram, an ironic work absorbs any criticism incident to it by saying that it already knew it, and that was the point. And no-one was more ironic than Shostakovich. So who was he making fun of? Stalin, probably. But now it’s you.

King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard, Sketches of Brunswick East (2017)

Mood music. Non-confrontationally paced, easy-toned, sleepy, psychedelic jazz delivered in nonchalant, smiling gestures; there’s pleasure to be sought in familiarity with the material, unexciting though it may seem.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Recent listening—

Charles Ives, Central Park in the Dark (1906)

The wisping harmonies of the opening lie somewhere between Debussy and Berg; “tonally ambiguous” doesn’t even begin to describe the haunting palette that these homophonic clusters convey. And you begin to ask yourself: Where is the Ivesian? When—a clarinet folk tune drifts in, ignorant of the shimmering fabric it meanders upon, the atonal accompaniment that is the only thing separating it from complete decontextualisatiom, from silence and death. But by placing it on the precipice of meaninglessness Ives imbues the time-worn melody with a sincere, singular, searing intensity that could be achieved by no other means. And then it is from there into a typical, gallivanting Ivesian density the likes of which are littered all over the orchestral works. This passes quickly before we get too tired of it, and we return to the really interesting part of the circuit through Central—really interesting because it’s discernible polyphony, and since we’re in the nighttime that’s what we prefer.

Igor Stravinsky, Requiem Canticles (1966)

Compared with the Ivesian, the Stravinskian is far more difficult to define. What is it, in essence, that was preserved over the chameleon’s multiple metamorphoses; what is it that, despite the guise of primitivism or neoclassicism or serialism, caused everything he composed to sound so inimitably Igor? Whatever it is, it is the reason why I return again and again to his catalogue—and the same reason why I find his music so difficult to write about.

Palm, Rock Island (2018)

How did they go from Trading Basics to this?—This was my initial reaction. Despite the EP being a clear stepping stone and a fairly obvious clue to the direction they were heading in, it’s still a surprise that they’ve completely let go of the post-punk angst and aggression that made their debut so exciting. And yet, somehow, inexplicably, their most recent, given time, can be just as exciting as their most distant. And it is more distant sonically than it is in time. For on Rock Island they open an entirely different toolbox, the central element of which is the MIDI. Keyboards are set to saxophone, steel drum, and an assortment of other electronic effects, leaving the band with such an extended sonic range that they actually, through some sort of multi-decadal osmosis, start to sound like the Beach Boys, particularly on the 4/4 section of “Composite” and in the quality of the melody on “Bread” (but certainly not in that of the accompaniment). On Rock Island, gone are the grimy ostinati and piercing dissonances of the debut; instead, a focus on clarity, on delivering the genius of their complex rhythms with the utmost precision. On Rock Island, they have found what makes themselves tick, made it their primary motif, and shed away that which obscured it. This, truly, is the band Palm. This is their post-post-punk.

Carlo Gesualdo, Madrigals, Libro 6 (1611)

When the ear tires of functional harmony and yearns beyond the 19th century one tends to look forward; to the Second Viennese and other independent revolts against the tyranny of tonality, forward and even further forward, to Stockhausen, to Boulez, to Cage. The unlearned secret was this: forward is the direction of the sun, the direction of time’s light illuminating history year by year, shining from the past to the present, ever moving forward but always streaming from the same eternal source. Thus: everything written after the common practice period, even that which was written in opposition to it, lies irrevocably in the shadow of the common practice period; the Second Viennese lies irrevocably in the shadow of the First. Instead, look back. Look back past Haydn, past Bach, past when functional harmony tamed the wilds of free modal counterpoint, past the birth of Schenkerian tonality. Look back to Gesualdo. See in the first four chords of “Moro, lasso” the same Expressionistic spirit that two and a half centuries later was to prefigure Tristan. See in the upward chromatic wisps of “Beltà, poi che t'assenti” the same rejection of strict counterpoint that three and half centuries later was to prefigure Ligetian polyphony. Gesualdo’s music is enigmatic, expressive, difficult, dark, and delicious. As Herzog would have it, he writes death for five voices. But this is wrong. Despite his life’s macabre escapades that have more than a little to do with why he is so well-remembered in the present, I would have this: he writes not death but the struggle against it.

Frank Zappa, Hot Rats (1969)

There’s a rampant, youthful creativity afoot, a liberation from insecurity that comes from shunning self-seriousness and scoffing at the pursuit of abstract greatness. It’s a frighteningly productive wildness of thought; the type that conjures recorder solos or Beefheart vocals or cover art like that. This is why it is interesting. And it is also why it is difficult: Zappa’s strings of ideas are connected by no logic other than that hidden forever in the internal workings of his creative psyche. Or have you not listened closely enough?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recent listening—

Luigi Dallapiccola, Variazioni per orchestra (1954)

Does more than skirmish with tonality; while not going so far as to formally cadence you at times get eerie progressions, ghosts of the 19th century rising from the dodecaphonic murk—only to disapparate before larger implications can be drawn. And speaking of implications, what does the opening’s BACH motif signify? It is a monolithic statement of the most legendary four note combination in history (runners up including DSCH and and the opening theme of the Jupiter finale)—Dallapicola in the footsteps of Berg and Webern in their worship of the master of counterpoint.

Françoise Hardy, La question (1971)

The intimacy of the combination of voice, violin, and guitar is what makes the tracks that are so arranged so alluring. This trio is the heart of the album and further touches raise it to a certain level of class distinguished by an effortless self-confidence, an unabashed economy of gesture, and a clarity of expression. Further touches such as: the wind effects on “Le martien” or the addition of double bass on “Chanson d’O” (c.f. bass guitar on “Viens”). And Hardy is sublime. The landscape of her voice is almost tangible.

J.S. Bach / Anton Webern, Fuga a 6 voci (arr. 1935)

A successful counterpoint ought to transcend instrumentation, as Bach taught us with Die Kunst der Fuge. Notwithstanding that the Musical Offering was written for keyboard, Webern’s orchestration takes little away from the original save the austere passion of a six-voice fugue unfolding on a single instrument. This is replaced by the dramatic power of an extended gamut of textures and timbres, expanding the work sonically, as well as, arguably, emotionally (one might counter that on keyboard it is purer, and thus, more monumental—but certainly the emotions are more obvious, more ready, in the orchestration). Schoenberg would be proud—marvel at the Klangfarbenmelodie!

The Beach Boys, Pet Sounds (1966)

Analytic curiosities include: 1. The chromatic mediant relationship on “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” that binds the intro and verse, a standard four chord progression in A that on repeat is altered to land on the flat major III as applied dominant to the I in the distant key of F, a modulation with which to traverse worlds. 2. Quarter note triplets and three bar phrases on “You Still Believe In Me” plus the lovely use of parallel mixture on the final chord of the refrain (a minor iv). 3. Harmonic planing on the first half of “Let’s Go Away For Awhile” and some excellent bari hits that herald the metric change into 6/8. Incidentally, “Let’s Go Away For Awhile” is the best track on the entire thing.

Béla Bartók, Piano Concerto No. 1 (1926)

What differs Stravinskian rhythm to Bartókian is that asymmetry is far more rampant in the Russian. The units are equally crooked but the Hungarian tends more toward repetition and so pays more heed to the heart of his folk than does old Igor; a proper Danse infernale. Harmonically the difference is clearer: not even in Le sacre would you find such brutal tone clusters such as those that punctuate the climax to this work’s middle movement. But why pit the two against each other?—though arriving at different results both aimed to forge lasting meaning in a post-tonal world; to answer Ives’s Unanswered.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

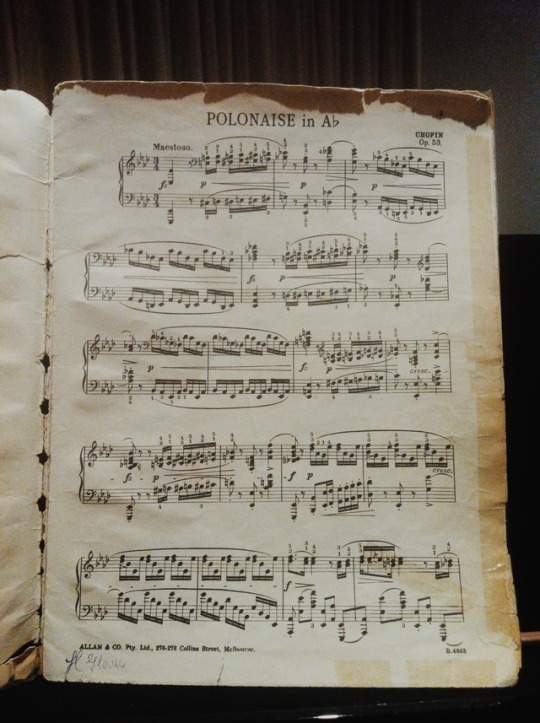

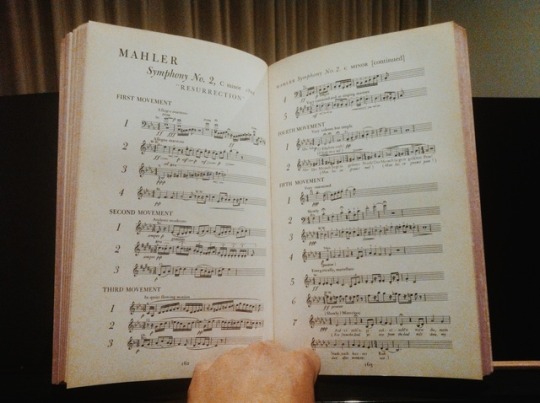

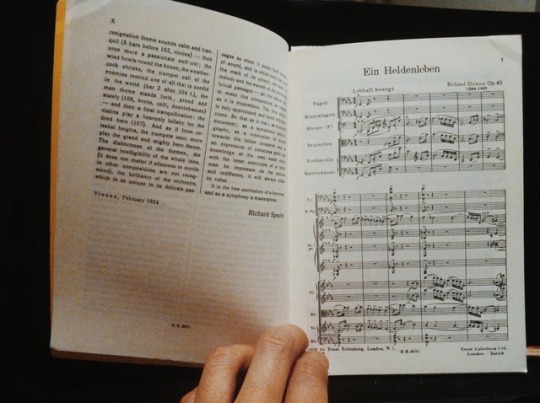

For my birthday I bought myself a few second-hand scores and musicology books from Alice’s in Carlton. They smell gorgeous. The Chopin is fraying and heavily taped but the other three are in excellent nick.

Frédéric Chopin (comp. 1842). Polonaise in Ab, Op. 53. Melbourne, Australia: Allan & Co. Pty. Ltd.

Raymond Burrows (1942). Symphony Themes. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, Inc.

Andrew D. McCredie (1984). Art Nouveau and Jugendstil and the Music of the Early 20th Century. Adelaide, Australia: The University of Adelaide and Graphic Services Pty. Ltd.

Richard Strauss (comp. 1898). Ein Heldenleben, Op. 40. London, WI: Ernst Eulenberg Ltd.

30 notes

·

View notes

Link

Interesting; after seeing The Last Jedi one of my immediate reactions was that it was the least memorable Star Wars score John Williams had produced due to what I felt was a lack of any new, interesting ideas (c.f. The Force Awakens introducing Rey’s theme, Ren’s theme, the Resistance March, and more). Ross’ article somewhat redeems it for me by pointing out the intricacies of the leitmotivic development. Nevertheless I still believe my initial characterisation is a major weakness of the score. Perhaps, though, it is more of a reflection on the exhausted state of the Star Wars franchise than on any compositional lack on Williams’ part.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recent listening—

Protomartyr, Relatives in Descent (2017)

Solemn cynics seek a grandiose aching, paint wicked scapes that bespeak a hidden, unexpected, searing depth of feeling; it is precisely through their gothic haughtiness that they betray their vulnerability. The execution of the pretence is spectacle enough: marvel at the heady monologued verse on “Here is the Thing” or instead the climactic descending pentachords that punctuate the last minute of “The Chuckler” to the words “...and poison in this soil”. Nevertheless the most important words on the whole thing appear on the first track and echo in the last, words in apparent contradiction to the nihilism you so desperately want to find, words that advocate an anachronistic humanism: “She’s just trying to reach you.”

Kara-Lis Coverdale, Grafts (2017)

Antidote to the unending rush of days and weeks, the whirlwind of time, space, people, place, passing instants placed as frames spooling wild into the forgotten past, task after task, night after night, the exhilarating maximisation of one’s faculties and the exhausting repose of achievement, then in again, on again, toil over time too little, toil tricking time to skip minutes, hours, no moment spared to notice, no rest for the wicked, only the bitter glee and cruel pride in the knowledge that one has seen one’s brink—such music as to be antidote and comfort against all above, and more... or at least it was to me.

Jlin, Black Origami (2017)

Quite gratifying that an album such as this is making the rounds of all sorts of year-end lists, one that’s designed on premises a world apart from what we usually call pop music, one whose driving impetus ain’t harmony or melody or a verse-chorus song structure but the oft overlooked element of rhythm. A different way of looking at music and yet still within the borders of what the average consumer would consider ‘acceptable’ to listen to—don’t kid, it’s not overwhelmingly avant-garde; just some fresh beats and a modest disdain for more ‘obvious’ music. The progressive doesn’t always have to be confusing (better if it’s not, actually, to allow the masses to catch up) and this certainly is not. It is very straightforward, very clean and angular, well-crafted and genuinely entertaining.

Chastity Belt, I Used to Spend So Much Time Alone (2017)

So much feeling conveyed with so little gesture! A shame that nothing on the rest of it quite approaches the perfection of the opening track (I have heard it over and over again and I’ve yet to get bored or find a fault), though this would perhaps be asking too much of something so modest—this is its greatest strength. And I relate incredibly to an embarrassing number of lyrics (too personal to reveal).

Sonic Youth, Evol (1986)

Ranaldo pulls off the drunken ramble far more convincingly than Kim ever did because his apathy’s far better suited to the material than her dreamy drugged stupors. He ought to’ve done it more. Second point: d’Anconia/Akston said:

There are almost no contradictions. When faced with a contradiction, examine your premises. You will find that one of them is false.

In this case, the contradiction: noise vs. melody. The false premise: that beauty is synonymous with grace.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Recent listening—

Caroline Shaw, Partita for 8 Voices (2012)

Posed Ives: Whither music? In turn, each pioneer of the new music frontier put forth their answer. Schoenberg: dodecaphony. Stravinsky: neoclassicism. Cage: aleatory. Boulez: total serialism. Reich: minimalism. Ferneyhough: complexity. Many more tried, and many more failed. As the decades wore on, and the gurus came and went, the Neue Musik, which had begun so potent and so hopeful, grew slowly darker. Crueler. The frontier fell into disarray. The climate became, and is, cynical, ironic, and esoteric. And yet, in the cerebral thicket, see the first shape-note-sung major triad of this work’s fourth movement shining radiant, eclipsing all else surrounding. The arrival at this chord is nothing but transcendent. Not since Messiaen has such joy as this been harnessed. This chord is the leading case for the claim that triadic harmony will not—should not—be abandoned. “Resonance will exist as long as we have ears to listen to what surrounds us.” The auditory phenomenon by which we derive pleasure from certain combinations of pitches from the overtone series is no theory. It is an inevitable facet of human nature. The Partita is not merely a celebration of tonality. It is a celebration of life.

Unsuk Chin, Clarinet Concerto (2014)

Descendant of the Darmstadt school not only via Ligeti, her teacher, but also through her music’s uncompromisingly anti-melodic character and the sense of a highly advanced technical rigour behind its surface seeming chaos. In this work there’s little to detect structurally apart from the vague fast-slow-fast form the three movement demarcation appears to suggest. Zooming in it’s not quite all a continuum; it does ebb and flow and the texture grows and recedes but the problem is (and this is what makes music of this sort so fiendishly difficult to listen to) that if everything’s a blur of demisemiquavers and extended techniques there are no easily identifiable landmarks for the ear to latch onto, in turn meaning: you’re lost in a context-less whirlwind of scattered pitches and timbres. Does Chin expect you to see the crystalline logic behind all this atonal commotion? I think not for any student of Ligeti ought to’ve inherited his very niche sense of humour. So then, is feeling lost the point? It can be, if you wish. There’s much nihilistic pleasure to be derived from posing your ear in question to new music and for once, not receiving any answers.

Anton Bruckner, Symphony No. 9 in D minor (1894)

How’s Feierlich, misterioso for a tempo marking? And how’s that opening!? For once this is music truly deserving of the adjective epic. The initial horn statement lurches, leaping, leviathan from the abyss, to a scintillating C flat major triad (theoretically justifiable since the C flat resolves down and the E and G flats sustain until repose at an A flat dominant seventh) at which some monumental pair of gates opens revealing a cavernous, starry expanse. Bruckner’s music resides in this domain, and at that figure, we are within it. The sole dedicatee was God. Your personal belief is irrelevant; when you hear music of such tremendous power you are convinced of one fact: that Bruckner believed.

Arthur Honegger, Symphonie liturgique (1946)

You can tell immediately he was the most Teutonic of Les Six—but this is not to say that his music carries with it the same self-seriousness and German angst as does that of a Strauss or Mahler (which had, anyway, come out of fashion by that time). In theirs you would not find such unabashedness, such cinema as is found in these three movements: see the use of percussion, see the rampant ostinati in the first and third, see the freedom with which the second movement polyphony mingles (freedom to flirt with tonality and its opposite alike, at your heart’s discretion). And it is cinema: from the opening brass skirmishes the third mvmt. unfolds rife with Williams-esque touches—although yes, the hierarchy should really be reversed, but who knows where the syntax would take us.

Igor Stravinsky, Les noces (1922)

Sometimes I feel that this is better than the rite; that this was the peak of Stravinsky’s Russian period. It is, on the whole, less episodic, more eclectic, more economical, and, weirdly enough, more humane—notwithstanding the vocal element there’s also less of the brutal paganisms seen in e.g. the Danse sacrale. It is also more celebratory, and the general brightness of tone derives as much from the compositional approach as it does from the instrumentation. Triads are plenty rife. Modal exploration seems to remain mostly on the Ionian side. And you get more of a melody/accompaniment notion (c.f again the Danse sacrale).

0 notes

Text

Recent listening—

Luciano Berio, Sinfonia (1969)

The third movement alone’s one of the most inspired creations of the mid-20th century avant-garde, up there with e.g. Cage’s 4′33″, Stockhausen’s Gesang Der Jünglinge, and Boulez’s Second Piano Sonata. In a way it derives from Ives; it is an emancipated polyphony built on the backbone of the scherzo from Mahler 3, a densely scored interweaving of disparate materials—except the materials are not, as in Ives’ case, parade tunes or Protestant hymns but masterpieces from the Western canon treated with a god’s disdain. What a thrill it is to hear Le sacre’s “Dance of the Earth” emerge from contrapuntal storms of Ravel and Strauss. Yes—it is very obviously compositionally impressive. But the most important thing about this is the effect of its execution; the effect on the listener. Q. How does one respond to music so formally primal, so lawless and unconventional? A. With great wonder. Its freedom from any presupposed rules makes it equally accessible to all; by taking esotericism to the extreme Berio crafts a state of primeval potency. And what is more primal than the human voice? Anyone can appreciate the beauty in the second movement vocal harmonies; they are so pure, so silken. Anyone can chuckle at the unexpected moments of humour e.g. the introductions of the eight vocalists or (my favourite) “Thank you, Mr. Boulez”. And anyone’s liable to be floored by the cataclysmic eruption that occurs in the minutes following “the name of Mayakovsky hangs in the clean air”. After a series of seismic thrusts propel us toward an overwhelmingly monumental chord what does first soprano exclaim but “MAKE IT LOUDER” with what ought to be the utmost of human passion, primary narrator then resuming with “CAN’T STOP THE WARS CAN’T MAKE THE OLD YOUNGER OR LOWER THE PRICE OF BREAD” and etc. and so on... what does it mean? What does it matter? It is simultaneously sheer terror and sheer joy; what more can you ask for?

Courtney Barnett and Kurt Vile, Lotta Sea Lice (2017)

“Let It Go”—bit of a let down following that gorgeous opener, and then they really had me worried after neither of “Fear Is Like A Forest” and “Outta The Woodwork” really hit the mark; on these (to quote “Over Everything”) they “bend a blues riff that hangs...” and just hangs... not really doing much... well the refrain on the latter’s pretty tasty (colour change at “...if you are” into the devilish “she’s so eaa-syyyy”) but it grows old pretty soon. Then: “Continental Breakfast”—it’s all there: time, space, spirit, and what’s more it makes you smile, you can’t help it, smiling of that happy-sadness with a hit of longing, of nostalgia for histories that weren’t yours, one mood both aching and joyful... yeah; the last five tracks on this are each masterpieces. “On Script” is one of the best Courtney’s ever written. And I’m not as familiar with Kurt as I ought to be but if he can write something as precious as “Peepin’ Tom” then he’s worth more of my time.

St. Vincent, MASSEDUCTION (2017)

So this is pop? Well, I suppose—the strongest element is melody and the melodies themselves are really actually motifs, i.e. we have short simple hooks and no extended lines and that's how the music catches you, so yes, in a way, and so the monstrous riffing that takes place all throughout makes this quality pop indeed; how are these for earworms?—

The melody to "I can't turn off what turns me on" on the title track

The verse riff on "Los Ageless" (which actually makes its first appearance on the number preceding)

The verse riff on "Fear The Future"

The refrain on "Young Lover"

These ideas and their kin represent maybe about 75% of the album. Between these bouts of saturated aural pleasure (again, this is what pop is), experimental pop superstar St. Vincent fades a little and who's there but old Annie Clark sotto voce and with the same vivacity and brightness of tone that was so attractive in the first place. "Happy Birthday, Johnny" could have been on Marry Me. "Slow Disco" could have been on Actor. The two poles collide on one of the finest closers I've ever known: "Smoking Section". If you want to pinpoint the juxtaposition it's accessible at the first 15/8 bar (at the second "let it happen, let it happen, let it happen") with first four beats being Annie and fifth being the majestic beast she's become. (And if you didn't catch it that is indeed a 15/8 bar in the wild.)

Edgard Varèse, Amériques (rev. 1927)

Quite a mess but that's half the fun and half the point; emigre Varese, flee-er of France, finds self foreigner in foreign domain, asks self: Why is it so noisy here? Answers with: Amériques. It is a Dvořák 9 for the 20th century with negro chorus replaced by urban cacophony. And where further does this lie in the great lineage? Antecedent to Stravinsky (elevates a modular technique as seen in Le sacre du printemps to a formal theory of “sound-masses”) and precedent to Cage (laying the seeds of sound egalitarianism by raising not only percussion but also such inorganic noises as sirens and whips to the same level of importance as pitch content).

Dmitri Shostakovich, Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor (1944)

Supersymmetric with the 8th String Quartet via one of the fourth mvmt. themes which in this is far more sinister than its all-out hellish rendition in the later work. On the whole, this work is subtler. There’s a greater range of ideas and yet all still speak clearly and all are developed organically—see the first mvmt. primary subject, first in canon then in piano octaves above an ostinato in the strings then plunging into a kaleidoscope of other ideas whilst never straying too far from familiarity... really a typical first mvmt. form (though not, as far as I can tell, a sonata-allegro) and this follows through to the second, third, and fourth: respectively a scherzo, largo, and allegretto. There are supersymmetries within the work itself: not only does the canon subject resurrect in the fourth movement (at a formally critical point when the infernal dance reaches its first point of repose with piano unleashing Ravelian arpeggios), but further, the end is heralded by a haunting revisitation to the block chords of mvmt. 3—only this time resolving to the deathly sweet embrace of the parallel major.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recent listening—

LCD Soundsystem, American Dream (2017)

On each of the original trilogy there was at least one 10/10 and three or four 9/10s—here there are no 10/10s and only one 9/10: “call the police”. Which is not to say I don’t care for it as a whole; apathy is weak rebuttal to such conviction as is displayed by Murphy and the gang, so bravo for trying, bravo for honest effort (the hype alone could’ve chart-topped it, regardless of quality). Surface-element-wise its much the same as old times and there’s no group of people better than them to try and recreate the sound of the LCD Soundsystem of 2002 to 2011 (this is what this is, an attempted resurrection). But the magic ain’t there. What magic? The magic of the pre-Trump era? The magic of the 2000s? Is it their fault this isn’t another Sound of Silver? Or is it the fault of the times?

Igor Stravinsky, Symphonies of Wind Instruments (1920)

Eclectic, concentrated, precise, vital, enigmatic... and the other word, of course, is polytonal. Lying between the chameleon’s Russian and Neoclassical periods you see elements of both: the former’s rhythmic, timbral primality and the latter’s formal rigour. But back to polytonality: where “Augurs” summoned a violence unmatched in even the wildest Wagnerian harmony, here the tonal juxtapositions evoke broad swaths of alien light—or more like darkness, a cavernous, velvet darkness, static yet immense. A cathédrale engloutie for the new age.

Slint, Spiderland (1991)

Seinfeld effect somewhat afoot, i.e. material once revolutionary influences so much subsequent that in certain spheres it becomes ubiquitous, and so, contemporary viewers/listeners fail to see/hear what all the fuss is about. But as with the sitcom, Spiderland was really the first of its kind, so its elements (now standard tropes of any given post-punk or math-rock record) speak so purely that you don’t mind that you’ve heard this kind of stuff before. By virtue of being the first, it avoids pretension, avoids infection—here we have but the fundamentals of post-punk and math-rock, bare and visceral; as potent as they’ve ever been.

Charles Ives, Four Sonatas for Violin and Piano (~1916)

Never forget the sentimentality in Ives—his music can arouse as much passion as does Berg’s. The difference is in the colour: Austro-German angst vs. a deeply spiritual American nostalgia. While the Ives aesthetic remained more or less consistent after he had emancipated polyphony it is not one that you can tire of easily. These chamber compositions advertise it in a different light: that of a limited number of voices—gone is the effect of supersaturating the texture with voice upon voice; every line is essential here, each melody sings and is heard. The unique beauty of Ivesian polyphony is here at its plainest, its most tender. The most utterly sublime passage in the four occurs toward the end of the first when he quotes one of the most utterly sublime passages in the Fourth Symphony: “Watchman, tell us of the night” atop dreamy clusters, atop some of the most harmonious dissonances ever composed.

Alvvays, Antisoialites (2017)

In general, they seem happier. Brighter timbres make for more positive emotions but less dreamy soundscapes and what we end up with’s more like Courtney Barnett than MBV—ah well, couldn’t languish forever. And what we gain: some exceptional riffing on Molly’s part as well as a gritter side to the electric-work (didn’t think the makers of “Red Planet” were capable of fun?—think again). There are some problems with form (e.g. the “Plimsoll Punks” interlude’s completely unnecessary and “Saved By A Waif” is stuffed with more ideas than it can carry), but aside from an uninteresting 6 minutes from “Hey” to “Lollipop” this is at the general quality of the s/t from start to finish. The moments on “Not My Baby” when the vocal line drops and Molly opens up the timbre (“…dooo whatever-I-want…”) are incomparably cool, and “In Undertow” is one of the best tracks they’ve ever written.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Recent listening—

Gabriel Kahane, Craigslistlieder (2007)

Proper new-age harmony in meticulous pianistic textures they’d call “supple” or something, yes, supple, e.g. that’s what reeked off many a program note to Boulez’s Le Marteau sans maître. This is even more personal and yet not as uncomfortable as you’d expect because it’s also ragingly pretentious, quintessentially millennial, and most importantly, genuinely funny. “Oh old friends / I remember you well” followed by right-hand echo and first you think, god, that’s gorgeous. And then you remember the lied’s titled “Half A Box of Condoms”.

Sergei Rachmaninoff, Symphony No. 2 (1907)

Chills at every reappearance of the motto theme. The Dies Irae semblance ain't the brightest trick but compared to the outright quotation in mvmt. 2 it's hardly bothering at all; who knew a three pitch theme could be so monumental? The earth practically crumbles as trumpets hail its final sounding at the close of mvmt. 4. For other supersymmetries, see: horn figures in mvmts. 1 and 4 resembling the solos in mvmt. 3. And also: the mvmt. 2 trumpet march (after the fugue) resurrected in mvmt. 4, in a triplet guise.

Arcade Fire, Everything Now (2017)

Oh nooooooooooooooooo.

Death Grips, Bottomless Pit (2016)

Some of the most important words I’ve recently heard were those from Stefan Burnett on inner struggle vs. surface reality. Perhaps from elsewhere it would seem arrogant to boast mistrust of fellow men and women but he’s no haughty misanthrope. The haughty is the part that’s wrong; misanthrope, yes. And so it’s MC Ride vs. Stefan Burnett, another brutal duality, and the main reason why Death Grips is the one of the most interesting art projects going round right now. The actual content, the surface level noise, is dangerously close to irrelevance.

Carl Nielsen, Wind Quintet (1922)

The ‘supple’ descriptor returns again to haunt; is it just a synonym for ‘chamber’? No, for you wouldn’t apply it to, say, Brahms or Schumann. But you would to Mozart, and definitely to the Nielsen Wind Quintet, so what we have here is really neo-classicism rather than neo-romanticism. Hence the opening sonata-allegro (complete with exposition repeat), hence the theme and variations. Pleasurable to listen to, and even more pleasurable to play.

0 notes

Text

Recent listening—

Palm, Shadow Expert (2017)

I was beginning to doubt that music this inspired could ever emerge again. But stuff like this reignites the spirit of the early 2000s, or, at least, the spirit of how they’re remembered—does so in terms of creativity, innovation, yes, and most importantly, in its whimsy and brightness of tone. It’s too easy to wallow in post-punk cynicism or, you know, trite social commentary (Butler, Murphy, today’s prime offenders), and it’s all very depressing and sometimes that’s the music you’re after but I think what we need most right now (or perhaps its just me) is a bit of optimism. The technical details (which are no less than stunning, I mean, listen to how tight they are on “Two Toes”—that devilish subdivision goes 1-2-3-4-5/1-2-3-4 to a single beat) elevate this to a perfect EP but it’s all driven by the soul, just hear those colours—oh how we missed music that made you smile.

Death Grips, Jenny Death (2015)

Picks up immensely at the parent double album’s namesake track; from then till the end there’s little respite and some of the hardest beats I’ve ever fallen in love with. Sure, from "I Break Mirrors with My Face in the United States" to “Pss Pss” its mostly just fucking around and having a good time, drunken fun, yeah, but the really profound part of the evening’s saved for that latter half. I’m prepared to put forth that the consecutive pair of “Centuries of Damn” and “On GP” represents the pinnacle of what I’ve so far experienced of their total output (all LPs minus Bottomless Pit, and also Steroids). On “Centuries” Ride spits world-tired verse then relinquishes the spotlight to a world-tired melody—a melody?? Not in my Death Grips, no, it can’t be... then we’re in 12/8 (or is it 6/8) for “On GP” and Hill’s really going at it, laying triplet sixteenths on each eighth (so is it actually a hyper-9/16), this is really something now, the feeling you get when riding this is quite indescribable—so all I can say is just please hear it.

Bill Orcutt, s/t (2017)

For a while it was difficult to tell whether I kept returning to this because there was something genuinely precious about it or only because of the fetishistic attractive force of an album of grotesquely deformed renditions of popular standards; covers, that is, of carols, anthems, show-tunes, ten all up, except that you’d be hard pressed to recognise the source material if it weren’t for the track titles, e.g. on this record is probably the darkest, angstiest, most expressionistic “When You Wish Upon A Star” that exists, and will ever. But listen long enough and you’ll pass through the phase where you wonder: is this faux-passion?—pass on to understanding that there is heartfelt emotion behind these chromatic skirmishes. At times he is meditative. At others, rapturous. The entire thing exists past the meaning of rubato; timelessness in the Messiaenic sense.

Eric Dolphy, Out to Lunch! (1964)

I find “Hat and Beard” to be strangely evocative—the head evokes a certain head, hatted, bearded, yes, and a body, too, strolling queerly down the street, very odd, this, but it’s just so curiously playful in manners familiar somehow to those of the nouvelle vague that you can’t help but meld sonic ideas with cinematic. It reminds also of Zappa, in the angular, asymmetric contour of melody—and in the debts that both owe to Stravinsky. There’s also a particular reason why the chameleon’s trace seems to waft throughout this: Dolphy and co. could so so easily stand in for the ragtag ensemble required of the middle-period masterpiece l’Histoire du soldat—direct matches in: cornet, double bass, clarinet, percussion. 4 out of 7 ain’t bad!

Grimes, Art Angles (2015)

Because you deserve a little treat every now and then. Call it what you want but this is really truly pop at heart and though there are progressive elements its far too accessible to be put under some niche label; do so and you’d feel a bit cheated at the incongruity between advertised character and actual. But note: this does not mean that the music has no depth. Sugary, yes, but this is low GI nutrient, broken down slowly, over repeat listens, the initial seed crafted well enough that your mind’s conception of the record grows, evolves, matures, provided the requisite effort on your part. Doesn’t sound like I’m describing pop? Well maybe this is what pop should be. Just because infectious melodies and straightforward structures make it easy for the listener doesn’t mean the music making should be just as easy for the writer. Claire Elise Boucher proves that if you put some thought into it then there’ll be ample subtlety there for those who seek it.

1 note

·

View note