Photo

Edito - Data Rhei Inventory (État des lieux)

[ENG] / [FR]

The intensification of the neoliberal phenomenon of acceleration seems each day to make our perception of the world look a little more like the uncanny. A shared feeling linked to the end of the metanarratives, or more likely to the stories of the end, often forces us to reconceptualise the deterioration of the socio-economic conditions in a loss of authenticity. This desire to find back the original offers us the fake legitimate desire to fight capitalism. This aspiration to recreate an intimate link with the land is regularly highlighted by the subalterns, who most suffer an economic crisis, which has now begun to be constant. This eagerness to the ‘real’, to the ‘human’, that had been usurped by the populists in the form of Take Back Control*, often finds its answer within a home, intended to protect the individual from the hostility of the outside world, providing an asylum for the original, last and fragile place of the control of our lives, but more than this offering a shelter. As we do this statement, we must be worried. What in the Airbnb shared flat does remain of the family’s protective cocoon? Taking the baton without any transition of a house which was both a symbol of the early capitalism, a resting place and a defense against the labor, the place of the ‘Internet of things’ has been proposed to us as a utopic solution to all the everyday worries. However, is this home really for us? Will we be able to feel protected when smart objects will have changed it into a data fabric? Will we feel safe under a roof endowed with personality? Is our little house strong enough to be a fortress against the ‘loss of the original’ if Airbnb transforms it in a sample flat? Metonymical for all a reality, this house that is no longer Jacques Tati’s ‘house of the future’ must raise us to look through the illusion. Indeed, the traditional home is in trouble: nomadisation; data gathering; opening of the private sphere to the gaze of Internet giants, and so discreditation of the sense of belonging. If the home still protects us from the weather, does it act as a shelter against the market’s attacks?

Therefore, it is driven by the desire, not to take back control, but to share its tools, that we decided to set up the journal Un-Residencies. The first issue will focus on the stakes of the home and the ‘homeness’. Taking as a starting point that the theoretical stalemate of the for or against the technology, which is petrifying all desire of struggle in a conservative stance, doesn’t serve the user, we decided to rewrite the questions instead of re-ask them. By substituting a worried and hasted “must we?” by a speculative and interested “how will be?”, we hope to see farther than the shadows on the wall: “How will the home look like when inhabited by objects endowed with intentionality and personality?”; “Will my house be a surveillance and incarcerating system when it will suggest me to communicate without hanging out?”…It is, looking for answers which surpass ideology, that we decided to call scholars, artists, web professionals, designers, architects and other curators to reinvest our home. By opening breaches in an ideologically loaded Real, where the present is conditioned by the future, we hope to overcome the polarization progressive versus reactionary. Depending on this overcoming: liberty to choose, to choose ourselves.

* Boris Johnson’s slogan for Brexit, 2016.

—

L’intensification du phénomène d’accélération du néolibéralisme semble rapprocher chaque jour un peu plus notre perception du monde de l’inquiétante étrangeté. Un ressenti commun lié à la fin des métarécits, ou plutôt, à l’époque des récits de la fin, nous pousse souvent à reconceptualiser la détérioration des conditions socio-économiques en perte de l’authenticité. Ce désir de retrouver l’original se propose alors comme figuration du désir légitime de s’opposer au capitalisme. Cette aspiration à retisser un lien intime avec la terre est souvent mise en avant par les populations les plus éloignées du pouvoir, qui subissent une crise économique devenue perpétuelle. La plupart du temps usurpée par les populistes qui l’exaltent sous la forme tristement connue du Take Back Control*, cette aspiration au « vrai », à « l’humain », trouve souvent sa réponse au sein d’un foyer qui, en protégeant l’individu de l’hostilité du monde extérieur, se pose comme ultime refuge de l’original, dernier et instable lieu du contrôle de son monde, mais surtout comme abri. C’est au moment où nous faisons ce constat qu’il s’agit de s’inquiéter. Que reste-t-il du cocon protecteur de la famille dans le logement partagé que nous propose Airbnb ? Prenant le relai, sans transition, d’une maison à la fois symbole du capitalisme et lieu de repos, rempart contre le travail, l’habitat de « l’Internet des objets » nous est proposé comme solution utopique à tous les tracas du quotidien. Pourtant, cette maison est-elle vraiment pour nous ? Pourrons-nous encore la voir comme un abri le jour où les objets connectés l’auront transformée en usine à datas ? Nous sentirons-nous en sécurité sous un toit vivant et doué de personnalité ? Notre bicoque fera-t-elle encore forteresse contre la « perte de l’original » quand Airbnb l’aura transformée en appartement-témoin ? Métonymique de toute une réalité, cet habitat qui n’a plus grand-chose de la « maison du futur » de Jacques Tati doit nous forcer à regarder au-delà de l’illusion. En effet, le foyer est en pleine déconstruction : nomadisation ; collecte de données, et donc, ouverture de la sphère privée au regard des géants de l’Internet ; déconsidération du sentiment d’appartenance à un lieu. Si le home nous protège toujours des intempéries, agit-il toujours en refuge contre les agressions du marché ?

C’est donc, animés par le désir, non pas de « reprendre le contrôle », mais de le redonner, que nous avons décidé de mettre en place le journal Un-Residencies, qui dans ce premier numéro s’intéresse aux nouveaux enjeux de l’habitat et de « l’habiter ». Postulant que l’enfermement théorique dans la logique du pour ou contre la technologie, qui pétrifie tout désir de lutter dans l’attitude du conservateur, ne bénéficie pas à l’usager, nous avons décidé de réécrire les questions plutôt que d’y répondre à nouveau. C’est en remplaçant le « faut-il faire ? » inquiet et précipité de celui qui veut agir avant de penser par un « que sera ? » spéculatif et intéressé que nous espérons voir plus loin que les ombres projetées sur le mur : « Que sera le foyer une fois peuplé par des objets dotés d’intentionnalité et de personnalités ? » ; « Ma maison sera-t-elle un dispositif de surveillance et d’incarcération lorsqu’elle me proposera de communiquer sans en sortir ? »… C’est à la recherche de réponses qui dépassent l’idéologie, exerçant ainsi leur fonction libératrice de révélation, que nous avons décidé de faire appel à des chercheurs, des artistes, des professionnels de l’Internet, des designers, des architectes et autres commissaires pour réinvestir notre foyer. En ouvrant des brèches dans un Réel déjà chargé idéologiquement, où le présent est conditionné par le futur, nous espérons dépasser la polarisation progressiste versus réactionnaire, dépassement duquel dépend la liberté de choisir, de se choisir.

* Slogan de Boris Johnson en faveur du Brexit, 2016.

Data Rhei is a research unit of social development. It is a venue on cultural innovations that aims to create ergonomic and narrative products into bringing together various independent actors involved within a fluid structure based on sharing. Non-Profit Entity, Data Rhei is a project born in 2016 in Paris, from the desire to reconsider traditional modes of artistic production through fixed-term interventions.

—

Data Rhei est une unité de recherche et développement social. C’est un lieu d’innovation culturelle qui vise à créer des produits de fiction ergonomiques en faisant intervenir des acteurs indépendants et engagés à l’intérieur d’une structure fluide basée sur le partage. Organisation à but non-lucratif, Data Rhei est un projet né en 2016 à Paris, FR, de la volonté de reconsidérer les modes de production artistiques traditionnels par le biais d’interventions à durées déterminées.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Aristide Antonas with Data Rhei Interview

[ENG]

Data Rhei : You created the project House for Doing Nothing, which is an answer to an assertion from Slavoj Žižek’s book Violence. You say you often work with writing poems or short stories created with and about the law, did you proceed this way for this project? Could you briefly describe it and relate it to your global approach?

Aristide Antonas : No, I did not start with the law in this case. The House for Doing Nothing began as a critique of a concrete written statement, a critique that is normally operated with an essay would now be done with architecture; this is what I decided when I read this text. Slavoj Žižek in this particular fragment was claiming that we should better step back and refuse engagement in order to think from a distance, somehow more productively and undisturbed because of this distance of withdrawal. I thought I could just design the space that Žižek would need for his withdrawal; I would then prove two things at once. The first would be that his so-called withdrawal is a normal or banal condition for every one of us; there is nothing heroic in this condition, we have already withdrawn without being conscious about it, the web is the name of this withdrawal; our distance from reality does not make us more vigilant. It is the opposite: reality is constituted by this distance. The second thing I wanted to show with this architecture was that only through this very withdrawal, that we have already done unconsciously, the contemporary “community of humans” is formed. Giorgio Agamben calls this “community”, if it is still one, “a-demic” i.e. deprived of the communal characteristics of demos. The nowadays human community is formed by this contradiction, by the very impossibility or by the unimportance of “really getting together”. So, I thought that The House for Doing Nothing could showcase fake heroism at the first level with this withdrawal. Secondly, it would show that the idea of withdrawal creates the banality of this society; it deals with a certain category of exoticism that is linked to the idealization of “elsewhere”; it transforms the tension between here and elsewhere to a dead zone. A dead category of the new urban experience is already offered to us; this house depicts the ordinary in its fake exoticism. This house then is not anything new. It shows the banality we live into in a fancy way. With this house, I only wanted to claim that withdrawal is not an exception but the rule; it is the condition of the everyday; an analog to the interface format. An interface is not a representation of something. It is an abstract empty world which carries a content very strange to it. Through the category of the interface, the intellectual distance to reality defines a different wasteland; it is a new type of scenography. We do not deal anymore with the space of a heroic self-exile; I could only write Žižek that the bed where he works is the answer to his idea. His bed was contradicting him: The House of Doing Nothing is only the “happy” extension of it; self-exile is not heroic but already designed for us, it forms today a stronger concept that we could call infrastructural desert. There is a heavy materiality within this infrastructure; withdrawal is the presupposition of this so-called community. Under this light, Žižek’s argument is not proposing any kind of derangement for status quo; a community organized by withdrawal does not seem to need further withdrawal as its political strategy.It would not need any kind of easy engagement against it; it may need the reinvention of being physically together in a different post-web social sphere; the civic conditions of our cities are transposed on a large scale towards the new statement form of life proposed by the internet. This is why I found something wrong with this Žižek's statement. Withdrawal is at the same time obligatory and definitive for what we call the social sphere today. It did not make sense to add any struggle to it since it is banal. The House for Doing Nothing is only a critique of this statement and not a solution; it is a question and not an answer concerning this paradoxical “society of withdrawal”.

DR : This work gave us the impression that you think architecture must act as a kind of political interface between the self and the society. Do you think the self is something we should empower because, as it would be intrinsically unpolitic, it should be the first resistance tool?

AA : There is an obvious critique concerning a certain civilization of the self in this project. And there is no light for any possible community yet. In my works on protocols and in my literature of law I posed the problem that you mention more explicitly. The position of the self in the frame of the community is maybe the main argument of Rousseau’s The Social Contract. We need to re-think the relation of the individual to the community; we are not able anymore to conceive what you call “self” and “society” in the same way as Rousseau did. The identity of what we meant as “individual” in the past is not functioning anymore. In the post-network conditions, we need to redefine the “self” as a population of ready-made borrowed identities or as an ensemble of user attributes. And the community is also very different than in Rousseau's time. The society also needs a redefinition. Society is an archipelago of protocols. It could be a market for protocols or a structure of protocols if the web keeps its power into the social sphere. So, even if we claim that the self is a resistance tool, we need to work more in order to structure a different self in a different community; the old self and his or her signature for ideas are not important anymore. The structural difference between the new self and the new social is weakened; the self and the social are structured through the same archipelago of ready-made platforms; this weakening makes responsibility impossible. We are not able to be responsible in this condition.

DR : Aiming at this empowerment of the self, you start by criticizing Hannes Meyer’s Co-op Zimmer (a transportable room with a bed, two folding chairs and a big gramophone on a table) as a turning point to Aureli’s “Passing Dweller” and the nomadic individual, to head yourself towards The House for Doing Nothing. I think there is something totally different between both: while the Co-op Zimmer is a proposition for an affordable, lightweight and minimalistic living, The House for Doing Nothing looks more like a standardized and low-cost holiday house. Even if the latter gives access to asceticism to a much wider population than usual, it seems always quite difficult to generalize it to the whole population. Then, how could we imagine democratize asceticism to the working class?

AA : On this issue, you have to read more. For instance, in the booklet we wrote together with Pier Vittorio and Raquel Franklin on the Co-op Interieur, I try to make a genealogy of the “bed” and the “table” in a typical domestic economy. There is a war between these two furniture pieces that I observe. The Hannes Meyer work is a very important still from this history. I told you that The House of Doing Nothing is a material exaggeration of the bed. We are all in the position of Žižek, doing the same, using our beds as cockpits. Beds fulfill our imagination of the holiday house without moving elsewhere. Or the bed is the banality of the holiday house when it invaded the city. I am trying to show the core of the everyday in the interface of the exotic. The House for Doing Nothing is our idealized bed or our idealized urban sleep. Our beds breathe with this fake idealization. And the city of today is made out of these beds. You say that this is a generalization from a part of the population to the whole of it; you need to do this to capture interesting concepts. Negri writes that Karl Marx was doing the same when speculating about the transformative power of the working class of the industry with his texts; the phenomenon was not yet formed. He was only speaking for a part of the social sphere. But this part was the most important for the evolution of things. Today, these observations are the most significant from my point of view.

DR : Oslo Architecture Triennale, by labeling our time as the “After Belonging”, seems to share your concerns about the possible loss of the self with the new culture of individual mobility and the “Passing Dweller’s” lifestyle. As it seems related to the idea of being a self with the feeling of belonging to a place, we probably need to worry that an increase of mental health inequality could follow the increasing of precariousness and the rental system growth. Then, do you think that architecture (and your projects) could address the ways we stay in transit and how can we still belong to places or communities?

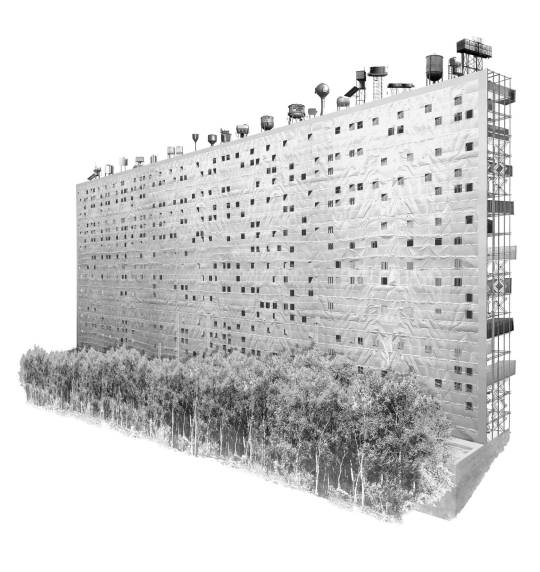

AA : Well, “being a self with the feeling of belonging to a place” is something very old to me; not because of belonging to a place, but because of the very notion of the self. We cannot simply say that today's self is heterochthonous. There is no today's self in the way we knew it in the past. Of course, heterochthony is a good concept that I propose as the opposite to autochthony. It describes the fact we often not relate strongly to a place of origin anymore. This is an old discourse. Oswald Spengler writes already about a similar character of deracination in his Decline of the West. But heterochthony is a positive concept. It relates to a constructive understanding of Unheimlichkeit, i.e. the most radical unhomely core of the western civilization. The west is demonized in its later phase, but there is no other human period with such a treatment of the unhomely. I miss already this elaboration of the view of the abyss in the post-western world. So heterochthony for me is a promise for a different consciousness on the self, it is already a political task. This is really a wishful thinking or my hope for the future. A consciousness of radical heterochthony would be a promise for a political future. But by lamenting the terrible side of the west as we are used to, with such a strong voice, we risk losing the positive construction of the unhomely character. This is a western construction. Investigating more about the limits of placeless communities while the humanity deals with radical heterochthony could be an open promise for the future; it would merge with a different web. I am sometimes accused for a nostalgia of the bygone west. Revisiting the past is for me an important part of any architecture; it is like in philosophy: we start thinking and designing being each time already in the middle of the way. There is an existing story we feel the responsibility to respond to. You ask about architecture in transit, it has its own history, Hannes Meyer’s Co-op Interieur is again a piece to reflect about this story. My Transformable Vertical Village was translating this potential mobility to a stable structure of an awaiting infrastructure where mobile units could plug in.

DR : Identity construction within the nomadic, and often diasporic lifestyle, often goes by going back and forth between interior and exterior, Home and house, real and virtual, and even human and machine. As these oppositions are very recurrent in the architectural language, do you think architecture, as a mean to build society, could be seen above all as a way to construct ourselves?

AA : This will be a very heroic architecture. But would this be a revisit of the same lost self of the past? The architecture of the self offers a nostalgia for optimists. I am not against nostalgia and its future. I am not against nostalgia, but we have to think more about it. Svetlana Boym gives a good description of nostalgia. And it would be great if we could name “architecture” the works on lost responsibility. It could renew the political in the terms we knew it in the past.

DR : We think that a problem with “neo-nomadism” is that it adds some identity insecurity to the isolation of 20th-century capitalist individual housing, making people even less able to struggle. Whether in your very interesting Transformable Vertical Village (which is a structure made of “elementary homes, hosted in ship containers through an interior solution that allows the units to plug in the village’s infrastructure”) or in The House for Doing Nothing, you use to work on living solutions based on individual housing. Do you think that individual withdrawal is more efficient than collective struggle to fight inequalities?

AA : For me, individual withdrawal gives space for an invisible governance – this governance is operated through the infrastructure. It is a challenge to describe this technical evolution with these terms. But there is no difference or tension between individual withdrawal or collective struggle. They are both parts of the image of a world which is vanishing. In the new world, withdrawal will seem as paradise and the struggle as always already ineffective.

DR : As curators interested in the domestic aspects of life, we are bound to think about the nakedness of the “one-room manifesto”. If, as Lissitzky said, Co-op Interieur was a “still-life of a room, for viewing through the keyhole, rather than a room”, studios in university residencies, for example, are very close from it. Only remain white walls to customize to make it personal. How do you think we could improve small housing, to help subjectivation and reflexion?

AA : This is a question for an architect, but also a question for everybody. Making home is similar to making oneself. It may need again a balance between stability and fluidity. This management may be the architecture of the political. We cannot help reflexion with space, but space is always concretized thought, and we can design fluid arguments.

—

Interview realised between April and May 2017.

Aristide Antonas’ work spans philosophy, art, literature and architecture. As a writer and playwright, he published novels, short stories, theater scripts and essays. His art and architecture work has been featured among other places in Istanbul Design Biennial, Venice Biennale, Sao Paulo Biennale, Display Prague, the New Museum and had solo institutional presentations in Basel’s Swiss Architecture Museum and in Austria’s Vorarlberger Architektur Institut. He won the Arch Marathon 2015 Prize for his Open Air Office, was nominated for a Iakov Chernikov 2011 Prize and for a Mies Van der Rohe 2009 Award for his Amphitheater House. He works as a professor of architectural design and theory, and directs the master’s program on architectural design at the University of Thessaly, GR. Aristide Antonas has been a visiting professor in the Bartlett UCL and at the Frei Universität in Berlin.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

David Apheceix avec Data Rhei Conversation

[FR]

De : Data Rhei <[email protected]> À : David Apheceix <[email protected]> Objet : Conversation Le 4 avril 2017 à 18:01

Tu es architecte et designer. Tu travailles en ce moment sur l’application Talebot, qui lie un questionnement sur la politisation des objets avec d’autres, liés à la médiation technologique et l’économie circulaire, y compris à l’échelle individuelle. Pour commencer, pourrais-tu nous présenter ton travail d’architecte, en lien avec l’idée d’une réalité où les objets font de plus en plus office d’interfaces entre nous et le monde ?

De : David Apheceix <[email protected]> À : Data Rhei <[email protected]> Objet : Re : Conversation Le 6 avril 2017 à 19:35

La scène étymologique de l’architecture est ambiguë et ouverte à l’interprétation. Le préfixe archi- en latin, convoque le grand et le supérieur, mais aussi l’ample et le multiple. La « texture », qui est devenue le « toit » quand elle est au-dessus dans une hutte primitive et a spécifié l’architecture autour de la construction, est pourtant une notion souple, un tissage ou, plus largement une forme tenue par un certain agencement de liens. Cet agencement peut être matériel, mais n’est-ce pas le groupe qui, en cherchant les conditions pour se rassembler, préexiste au toit ? Il me semble qu’ils se constituent en se formulant mutuellement, l’ensemble se tient par un lien expressif. Le monde serait comme un monolithe de matière indifférenciée, dans lequel les choses apparaissent dans la fugacité d’un usage comme médiation, un moment de formulation aux autres qu’on pourrait qualifier d’happenstance, scène où objet, sujet et projet se nouent et produisent ponctuellement leur existence mutuelle. Faire de l’architecture consisterait ainsi à ajouter au monde de la rugosité, des dispositifs pouvant, par leur plasticité intelligible, être saisis pour faire lien. Ce qui pourrait être aussi une définition de l’interface. Formuler, dans mon contexte individuel d’architecte, un morceau d’expression dont chacun pourra se saisir ou pas, de n’importe quelle manière. Les grands récits structuraient verticalement des cohésions en mobilisant des objets très chargés expressivement, mais concentrés comme dans l'église baroque. Le peer-to-peer digital éclate les récits cohésifs à l’échelle individuelle et multiplie la mobilisation de médiations diverses ; on fait feu de tout bois en démontrant son habilité à faire usage du monde, des objets, des manières, de l’accès aux choses. Ce régime d’expressivité générale, diffuse, est avide d’opportunités d’usage dont les objets ou l’architecture peuvent être des supports ponctuels. Ma pratique, pour reprendre une formule d’Andrea Branzi, ne consiste qu’à ajouter des choix possibles.

Le 11 avril 2017 à 08:21, Data Rhei <[email protected]> a écrit :

Finalement, en pensant les objets sous le prisme interfacial, avec des entrées et des sorties, tu les penses comme les moyens de fabrication futur. On pourrait dire qu’en pensant les choses comme faisant partie d’une longue trainée de causes et d’effet sociaux et politiques, tu fais le choix de les penser via le prisme de leurs fonctions, mais avant tout de leurs conséquences. Si on te comprend bien, penser l’habitat pour toi, c’est avant tout penser un levier vers un mode de vie ? Ton travail doit beaucoup passer, en amont, par la l'interrogation et la conception de style de vie, non ?

Le 16 avril 2017 à 17:35, David Apheceix <[email protected]> a écrit :

J’essaie de décrire l’idée de life autonomism, inspirée du mouvement du Lifestyle Anarchism américain théorisé par Murray Bookchin, mais substituant à la liberté une continuité quelconque. Le lifestyle autonomism désigne un mode de vie intégrant dans tous ses aspects les mécanismes concomitants de sa production, en temps réel, et de sa propre subsistance. Là où le travail était une sphère séparée permettant d’alimenter un mode de vie prédéterminé, comme une finalité, le lifestyle autonomism saisit en cours de route les moyens de sa production et d’une certaine subsistance, stratégique, en son sein même. Il ne sous-entend pas pour autant un conservatisme : là où la liberté individuelle est conditionnée par le jugement moral d’un choix meilleur qu’un autre, amenant à chercher à conserver des situations « voulues », le « projet-continuité » autonomiste embrasse dans chaque situation une opportunité quelconque de continuer. Ainsi, c’est plutôt une continuité de pointillés, ou d’épisodes pour reprendre un terme de Zygmunt Bauman. Airbnb fournit des exemples simples, la négociation subjective avec le monde de sa décoration, ou la décision impromptue de partir quelque part, cristallisée par une demande de location intéressante de son appartement. Plutôt que sur la fonctionnalité, surdéterminée et monovalente, c’est une perspective basée sur l’usage, opportuniste, qui répond à des concours de circonstances, qui peut se poser sur tout et former n’importe quoi, donnant une existence éphémère à des choses par une manière de les actionner. Son sujet serait comme un marin seul sur une barque dans une nuit sans étoile. Il peut se diriger dans n’importe quelle direction, il ne manque pas d’une capacité d’action ni de décision, pourtant l’absence d’une médiation extérieure, peu importe laquelle, rend vaine toute action. L’enjeu est, pour lui, l’abondance de signaux assurant la continuité de la navigation, et non plus un point d’arrivée particulier. Le problème pour l’architecture est d’avantage la création de multiplicité que la résolution de particularités.

Talebot, en collaboration avec groupe CCC.

Le 9 mai 2017 à 18:46, Data Rhei <[email protected]> a écrit :

Ce lifestyle autonomism dont tu parles nous pose question. Nous nous demandons si posséder l’ensemble des modes de production et de reproduction de sa vie ne pousse pas à aller vers une forme d’incarcération. Plus précisément, nous pensons à l’idéal des suburbs et au capitalisme d’après-guerre, qui se développe depuis l’arrivée des premiers réfrigérateurs et machines à laver dans les années 1940 jusqu’aux Dash Buttons d’Amazon. Nous n’allons plus au puits ou au lavoir qui, en étant des lieux communautaires, ont pu être des lieux du politique ; en intégrant à la maison les technologies de reproduction, certains diront que nous avons isolé les individus. On peut alors se demander si le développement de l’informatique ubiquitaire, qui nous permet de tout faire de chez nous, produire et consommer, n’est-il pas, au final, un pas de plus vers l’idéal de pacification et d’internement suburbain que nous échangerions contre une liberté ?

Le 23 mai 2017 à 00:15, David Apheceix <[email protected]> a écrit :

Pourtant en se transposant à la maison la logique de plateforme en fait un lieu de passage pour une multitude de nouvelles relations sociales : dates, guests, réunions professionnelles, etc. Elle est une variable d’ajustement face au manque d’espace, au prix des loyers et à la précarité des activités indépendantes qui se développent. Son accès se module, la clé est supplantée par la serrure activable par les privilèges négociés à travers une plateforme. Le contenant solide de la famille s’assouplit au profit d’une vie sociale en tenségrité, pour reprendre une analogie de Peter Sloterdijk avec les dômes géodésiques, dont les points tiennent forme par des modulations de forces faibles pouvant se réajuster sans cesse. On se rend compte que ce qui semblait une finalité, par exemple la propriété, n’est qu’un moyen d’avoir à disposition les choses et par les choses, les autres. L'efficacité de celle-ci est mise en crise par les plateformes digitales, qui substituent à sa force solide des moyens de disposition agiles, corrélatifs à l’improvisation de modes de vie. Les plateformes permettent un avoir à disposition loose – il faut à la fois pouvoir tenir et lâcher, alors que la propriété ne sait que tenir. De la même manière, elles agencent des relations peer-to-peer en continu, sans besoin de la fixité communautaire. Les lieux du politique se déplacent ainsi de l’espace vers ces dispositifs, où se nouent les relations, en amont de leur déploiement dans l’espace. Giorgio Agamben en fait le constat et propose deux attitudes pouvant amorcer une stratégie politique vis à vis d’eux, la « prolifération » évoquée précédemment, et la « profanation », soit ramener ces matrices algorithmiques dans un champ d’entendement communément accessible pour les rendre critiquables et transformables. Les logiques de disruption et de bootstrapping qui les régissent sont aussi contradictoires avec l’idée d’incarcération, puisque l’une raccourcit la durée de vie des dispositifs et rabat les usages à chaque innovation, et l’autre les place dans un régime de test et itération permanents pouvant amener à leur abandon rapide (les Google Glass rejetées presque « démocratiquement »). Cependant, en amalgamant vie, travail et loisirs, peut-être que le lifestyle autonomism tend à produire un temps homogène dans lequel tout est lié, sans extérieur. Dès lors comment prendre vacance d’un travail diffus ? Comment s’extraire temporairement de la gestion permanente ? L’application Talebot, sur laquelle je travaille avec Alice Gavin, Valentin Bigel et Pierre Garnier, adresse à sa manière cette question de susciter des poches de réalité « en plus », quasi accidentelle. Comme un coin du feu digital, elle indexe et croise par thèmes les présences de chacun pour provoquer des aventures impromptues.

Le 1er juin 2017 à 12:30, Data Rhei <[email protected]> a écrit :

Si la maison est pensée comme l’outil de transformation du travail en capital, puis d’échange de ce capital, elle semble finalement se substituer à l’usine et au marché. En la définissant comme le moyen et non plus la fin, ne transformes-tu pas l’habitat en ce que Karl Marx appellait le capital fixe, c’est-à-dire en une machine-outil dont l’achat était autrefois à la charge de l’employeur ? Notre dernière question serait alors : une fois l’usine comme lieu d’accumulation des forces de travail liquéfiée et atomisée dans le logement, comment – à la manière de Talebot – peut-on produire les outils de la lutte sociale, de l’évasion et de la socialisation nécessaires pour faire du lifestyle autonomism un mode de vie viable et durable ?

Le 12 juin 2017 à 15:14, David Apheceix <[email protected]> a écrit :

Les moyens de production tendent à être embarqués et c’est cette diffusion et généralisation de la productivité qui fait de la maison un lieu de production parmi d’autres, avec des spécificités liées à la gestion privée de son accès. L’émancipation, dans ce mode de vie, pourrait prendre la forme du sentiment ressenti pendant l’heure en plus au passage à l’heure d’été, ce temps étiré pendant lequel les possibles semblent temporairement démultipliés dans la trame même de la vie quotidienne. C’est un moment de battement où le mode d’emploi du temps n’est plus évident et appelle une certaine improvisation. Jacques Rancière évoque un « moment quelconque » qui « exploite la circonstance quelconque non au service d’un enchainement concerté d’actions mais pour elle-même ». Comment générer de l’heure d’été ? Cette question pourrait aussi renvoyer vers « les zones temporaires » de Hakim Bey ou l’errance situationniste. Dans L’Homme sans contenu, Giorgio Agamben se penche sur le rapport au travail dans l’Antiquité grecque, basé sur une dissociation entre la praxis, le travail de production de ce qui est nécessaire à la survie, travail des esclaves, et la poiésis des citoyens, la production d’un « espace où l’Homme trouve sa certitude et assure la liberté et la durée de son action ». Il étudie comment le travail primaire de la praxis a pris le dessus à travers l’Histoire et est devenu une valeur prédominante. Si la praxis est un faire basé sur la volonté, avec une finalité déterminée (la production de tel objet), Agamben précise que la poiésis « n’a rien à voir avec l’expression d’une volonté » : sa finalité est de porter quelque chose à la présence, hors d’elle-même. Alors que le travail productif industriel disparait avec l’automatisation, nos modes de vie reviennent-ils vers un régime de la poiésis ? Ce régime pourrait-il être amplifié par des dispositifs poétiques ? L’émergence de l’intelligence artificielle amène, elle aussi, cette remise en question de la volonté, puisque que cette technologie promet de traiter des informations pour suggérer des choses plus pertinentes que ce qu’on aurait pu concevoir. Incorporée à des objets, disposée dans le monde, elle pourrait être une interface d’agencement superficielle qui multiplie les opportunités à saisir pour donner existence à ces poches d’augmentation. Par exemple, avec Salassa Mitsui, nous travaillons sur un mobilier pour la ville dans lequel la matérialité de l’objet fait interface pour actionner directement la transmission digitale d’une proposition hic et nunc, offrant à un moment donné la possibilité de faire une chose non envisagée avant, ouvrant un espace temps qu’on choisit de saisir ou pas. Le digital est toujours ramené à l’analogie avec le monde matériel, des robots et de l’AI humanoïde aux objets dupliqués en réalité augmentée. Pourtant, les robots qui sont déjà partout, ceux des lignes d’assemblage, ne ressemblent à rien. L’AI risque aussi de se réaliser en effets informes, comme une fine membrane d’orientation de l’expérience dans le monde, catalyseur de possibilités, comme un coach de choix pour ajuster sa vie sans cesse, au gré d’une errance « créative ».

*Bibliographie :

Giorgio Agamben, L’Homme sans contenu, 1996, Circé. Giorgio Agamben, Qu’est-ce qu’un dispositif ?, 2007, Payot & Rivages, « Petite Bibliothèque ». Zygmunt Bauman, L’Amour liquide – De la fragilité des liens entre les hommes, 2004, Le Rouergue / Chambon. Hakim Bey, Zone autonome temporaire, 1998, L’Éclat. Murray Bookchin, Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm, 1995, AK Press. Andrea Branzi & Nicoletta Branzi, Animaux domestiques : le style néo-primitif, 1988, Philippe Sers / Vilo. Jacques Rancière, Les Bords de la fiction, 2017, Seuil, « La Librairie du XXIe siècle ». Peter Sloterdijk, Sphères III : Écumes – Sphérologie plurielle, 2005, Maren Sell, « Essais et documents ».

—

Conversation réalisée entre le 4 avril et le 9 juillet 2017.

Diplômé de l’École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture Paris-Malaquais en 2008, David Apheceix complète depuis 2013 un master de philosophie et critiques contemporaines de la culture à l’Université Paris VIII. Il fonde La Ville Rayée en 2006 avec Benjamin Lafore et Sébastien Martinez Barat puis son propre studio en 2014. Ses projets oscillent entre conception d’objets, d’espaces publics, domestiques et d’exposition. Cherchant à étendre le champ de l’architecture dans une catégorie plus large des dispositifs de médiation, il développe ses recherches à travers des studios d’enseignement à l’École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture Paris-Malaquais (« Idées courtes » en 2011, « Duplex » en 2012, “Embedded” en 2013), des conférences (“Lifestyle Autonomism” au New Generation Festival, Florence en 2014, “Bots, Wares, Mirrors” au colloque « Le Sujet Digital », Paris en 2015) et des expositions (« Kenchiku / Architecture » au Pavillon de l’Arsenal, Paris et chez Axis Gallery, Tokyo en 2014, “DiaAgram #4” à Warehouse Four, Dubaï en 2016). Depuis 2015, il développe Talebot, un outil à l’intersection de ces problématiques sociétales, productives et personnelles sous forme d’une application digitale, en collaboration avec groupe CCC.

0 notes

Photo

Melanie Bühler with Christopher Kulendran Thomas and Brad Troemel Discussion

[ENG]

Melanie Bühler: Both of your practices connect to scenarios of living in a situation that is increasingly mediated by precarity and technology. With you, Brad, I am in particular thinking of the work you create through Ultra Violet Production House and with you, Christopher, I think of your very ambitious project New Eelam. I was wondering if you both could explain your projects and point out how they connect to a current living situation that you experience.

Brad Troemel: Ultra Violet Production House is a project I do with Joshua Citarella. We take the images of products available through on-demand retailers like Amazon Prime, Ebay, Alibaba and composite them into new works available on Etsy. Everything we sell though Etsy does not yet exist. These Etsy ‘products’ really are digital composites, hypotheticals made from other already available product parts. At the point of purchase, the buyers then are sent those constituent parts, any tools needed for assembly, an instruction guide for assembly, and a certificate of authenticity. Shipping is provided most often for through Amazon Prime. By not holding our own parts, we have no storage fees; and by not assembling our own work, we have no fabrication bills. Our production model, in relation to the precarity that you mentioned before, is a way of trying to reconfigure the necessity for artists to go into debt as a requisite for production. Typically speaking, artists toil in a studio that costs money, using materials that costs money, with an education that costs money, with the hope that someday a curator, art dealer, or an otherwise important figure from the art world will stumble upon this trove of art that they’ve made in the studio, and create an exhibition opportunity for them. At which point, they’re still in a precarious situation: If they exhibit in group shows, they need to have to ship their own work, install it, reconfigure or remake it, all of which cost more money. At the point of potential purchase, they have amassed a huge amount of debt, just by building up the necessary visibility to participate in the art market. What we’re trying to do is a kind of reversal of that. We’re trying to commit as little as possible of our own manual labour and then position artworks in such a way online that they’re able to glean the most visibility while deferring aspects of precarity to the networks that we use: the companies we buy parts through or the buyers themselves. The goal is to maintain the highest productivity committed toward making new ideas at the lowest cost possible.

MB: And this also goes for space, in the sense that you minimize your physical presence in a spatial sense.

BT: Yes, absolutely! On a basic level it results in neither of us having a studio, which is a financial necessity for us at this stage. At the level of not pre-emptively fabricating works it applies as well: in allowing the market to determine which works become physical and which ones remain digital hypotheticals, there are no superfluous objects taking up space. This results in a streamlined, fluid protection that only assumes space when artworks are actually sold.

Ultra Violet Production House, Brad Troemel & Joshua Citarella, 2016, O Fluxo, courtesy of the artists.

MB : This ties beautifully to a question uttered in the promotional video for New Eelam. The video starts with a series of questions, among which: What if homes are streamables, just like movies? I feel like the undertone here, just as with Brad’s project, is to conceive of consumption as something liquid: that you produce only if there is demand for a product and that you don’t put things out there, but that you keep everything in a state of flux until it’s needed. This ties to a larger framework or ownership that could be related to Zygmunt Bauman’s notion of liquid modernity. Perhaps we could talk about the concept of liquidity in relation to your project, Christopher. I would be curious to hear how you make use of this language and what it means once we go more specifically into how we live today and how housing is perceived today.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas : Yes, and I think what you’re talking about something that you don’t use when you don’t need it. I was thinking about how hard that kind of idea could transform transportation. Right now, the most prominent example are cars. Up until now, motoring has been not only a form of transportation, but also a form of self-expression. But I wonder if that will continue to be the case. Not quite as much, I would argue. For instance, I’m thinking about Tesla’s strategy here. At the moment, you have to buy a Tesla. In the near future, the company’s prediction and sales strategy, however, is, that some people will still buy a Tesla, but other will be able to hail a Tesla. In the same way as they can hail a self-driving Uber. But the interesting thing about the Tesla plan is that even those people that buy their own Tesla car will be able to allow these self-driving cars to go off and pick up other people. So, it makes use of the downtime when a car is not in use. As such, there is a new kind of mixed economy emerging built on various forms of ownership. I think that the added utility of this will outweigh what people have gotten from the idea of maturing your self-expression / self-expression through ownership? And I wonder if a similar thing could happen with housing. Up until now, your home is, similarly, a form of self-expression. But the way in which housing is organized really hasn’t kept up with the reality of how people live: that people need to work in increasingly flexible ways and potentially move around more and more. I believe that transportation will become entirely decarbonized within our lifetime. And I wonder if housing could actually become a kind of a commodified technology, just like phones and now watches. There used to be many different kinds of phones. Now, there basically is one phone, a version of that some phone or an HDTV version of that same phone. But it’s infinitely customizable and infinitely usable. Meaning that a well-designed, streamlined, well-functioning, standardized commodified technology actually provides much greater utility than the multiplicity of phones that used to exist. And I think that this also applies to other utilities. For example, in the case of the watch, there used to be an infinite number of watches. In recent years, since people have phones, the watch has become completely useless. But now, the watch has been reinvented as a standardized commodified technology that is much more useful than any watch in the past. I wonder what housing will look like how it would work if we similarly think of it as a standardized commodified technology.

MB: Could you go a bit more into the specifics of your plan, your project New Eelam?

CKT: New Eelam is the company that I’m starting with colleagues. We’re basically bringing together an interdisciplinary team of specialists from the fields of technology, real estate, finance and architecture to think about how housing can be organized beyond national borders. What we’re developing more specifically is a flexible housing subscription for global living. A flat rate based on a monthly subscription will give you continual access to high quality apartments in specific neighbourhoods and cities around the world between which you can move around freely, as you wish. So, you’ll be able to simply tell New Eelam where you want to go next, and a new place will be ready for you by the time you arrive. You can stay for as long as you like and then tell the app where you want to go next. Because of the flexible way in which theses properties will be inhabited, they can also be bought and sold, but optimally. And, over time, the capital gains from trading will reduce the cost of the subscription to these flexibly inhabited apartments progressively. So, if you imagine before Netflix or Spotify would have been pretty hard or certainly before Napster. This may seem hard to imagine now, but so were services like Netflix or Spotify, certainly before Napster. It would have been really hard to imagine how old commercially available media could be available legally for a relatively small subscription. Now, in retrospect, that kind of subscription model is pretty straightforward. With music or movies there are, however, no marginal costs for the reproduction of that kind of media. That’s certainly not the case for housing. You can’t infinitely print houses at no marginal cost, but my colleagues and I believe that housing could be even more compelling in subscription form because with housing, the actual asset that one subscribes to, can, over time, subsidize the cost of the subscription itself. At the moment, real estate markets extract profit through rent and through asset appreciation. Our model uses the asset appreciation to reduce the cost of the subscription.

MB: You started out by describing that this new model works if self-expression is de-coupled from consumption/housing. The way I see it, it’s not only this, but for this model to work, one also would need to do without the affective qualities that we assign the products that we own, the environments that we inhabit and we call our own. This affective quality that emerges from the physical presence and ownership of things has similarly gone in your practice, Brad. You conceive of your artworks as conceptual mock-ups without ever relating to them as material things. So, both of your projects have this aspect of prioritizing a virtual, intangible infrastructure over the material tangibility of things. A certain romanticism about art making goes out of the window here, one that is tied to an intimate relation to material stuff. Similarly, in a living/housing situation, if we feel at home someplace we also feel at home because we relate to things intimately. With subscription based homes that aspect would disappear. How would a model like this deal with it?

CKT: The way I see it, this is just part of a changing reality. For example, I no longer have a record collection, because all my music comes with me. I also don’t really have a book collection, because all my books travel with me. Consequently, I think it’s only logical to think about the possibility of a cloud-based way of organizing housing. One that is, however, based on collective access and not on individual or private property. The reason we’re interested in this, relates to your original question about precarity. Today, real estate as part of a diversified investment portfolio is only really for the super rich. For most homeowners, their home constitutes the majority of their investment – maybe even their only investment. Quite often this is leveraged to the hilt with a mortgage. So, homeownership massively increases precarity. It massively increases middle-class precarity. People who are renting get screwed even more. The real estate market makes the antagonizing forces fundamental to our present economic system between renter and owner / owner and investor explicit. What we are interested in is enabling something that could work better. An alternative, that might be relevant for some people, not for everyone, but something that could work better to enable much more flexibility in renting, free from personal debt and a false sense of security that comes with money. This is something that can only be possible through collective actions rather than individually on property.

MB: Who do you imagine to be the users of the service? Who is your target group?

CKT: In the first instance, this will be most relevant to people that are already living between a few different cities and I think the art world has always been kind of good at experimenting new lifestyle formats. Loft living first practiced in the art world more than half a century ago, would be a really obvious example for a model that later became a mainstream lifestyle aspiration. And similarly now, I think the art world is a the forefront of globalization on the level of lifestyle. So, I think in the first instance, our target group will be people that already live between a few different cities. If we can make this work and if we can demonstrate that it’s possible to live between several cities for the equivalent to the cost of rent in one city and if over time, we can demonstrate how event he cost of that subscription could be progressive, then, I think, this could become a more and more compelling proposition to more and more people.

MB: Essentially, what you have in mind then is an artistic avant-garde who is living this international lifestyle already. Do you think that this is an aspirational lifestyle for other people as well? Or do you think it’s just inevitably that people work more and more internationally and more globally and that mobility increases anyways, and this is where the future goes, and you want to build towards that future? So, what I’m trying to figure out is if you think that you look at of something that is inevitably coming or to something that you wish for to come. What is your position in it?

CKT: Well, one of the many things that I find really interesting about what Brad and Josh are doing now is that it seems prescient of what the future of work could look like. As jobs increasingly are automated, more people will be working increasingly self-sufficient and creatively. And as that happens, it seems that the home after rather than the factory or the office becomes a primary source of production for a decreasingly post-work economy.

New Eelam, Christopher Kulendran Thomas, curated by Annika Kuhlmann, New Galerie, Paris, FR, courtesy of the artist and New Galerie.

MB: Building New Eelam’s infrastructure is such a huge endeavor and I admire you for doing it – it’s very impressive. In which sense do you think this is an art project?

CKT: We are at the very beginning of this journey. And it is growing out of our understanding of what can be done in the world, structurally, operationally, in terms of standing at the frontline of globalization and processes of gentrification, as well as in terms of prototyping immaterial labor. So, whilst we develop a business, this will have consequences far beyond the art field, if it works. We have also been introducing the project to the art world: I have been working in collaboration with an architect to develop it by doing exhibitions. In reality, we ended up being able to bootstrap the very early stages of developing the business with our exhibitions. This actually is quite a good way for us to think about how we can communicate as a brand in more complex, sophisticated ways.

MB: So, the art world is a kind of testing round for the project?

CKT: Yes! Exactly. For the exhibition we’re working on for the Hamburger Bahnhof, we’re using a space as an R&D project in a way that experimenting with some of the technologies that might end up in the apartments that will come. We’re also working with designers and engineers on an aqua-control automated vertical plumbing system and on photovoltaic furniture and that kind of engineering that is about construction methods. These are things that might not be in our minimum of the project. These are things that might not materialize in our project. But they could be pretty quickly be implemented in what we do with the business. So, it’s a way for us to experiment beyond that which is feasible from a purely business point of view. It’s a bit like how car companies might make a concept car right.

BT: I relation to this, I was thinking about the degree to which your business, probably like Josh and mine, doesn’t view profitability as the sole motive for its existence. I’m interested in Eelam’s self-perpetuating ecosystem of ownership – I don’t know if you want to call it rental or living. It’s a self-reflexive view on real estate in the way that Ultra Violet Production House is a self-reflexive take on what an art object can be and how the process of art making can unfold. We believe what we’re doing is a rudimentary version of how a larger segment of artists will continue to produce works as time goes on, and as increasingly fewer galleries are able to afford their artists production budgets.

CKT: I think that what’s brilliant about the Ultra Violet Production House is that rather than simply critiquing the problems of artistic production you’re actually really making a different kind of economic model work. And that’s a strategy that I’m very sympathetic to. I think that as a classical critique and in waiting to do something differently but I’m certainly more interested in how we can make something that works better rather than even requiring an emergence.

—

Discussion realised by Skype on February 23, 2017.

Melanie Bühler lives and works in Amsterdam, NL and New York, US as an independent curator and as curator of contemporary art at Frans Hals Museum. She is the founder and curator of Lunch Bytes, a project on digital art and culture, including talks, discussions and an online platform for which she collaborated with institutions such as the Goethe Institut, Art Basel, CCA Glasgow and ICA London, among others. Her most recent exhibition projects include “Inflected Objects #2: Circulation – Otherwise, Unhinged” at Future Gallery in Berlin, DE, “Inflected Objects #1: Abstraction – Rising Automated Reasoning” at Swiss Institute Milano, IT and “Brands – Concept / Affect / Modularity” at SALTS Project Space Birsfelden, XX. She is the editor of No Internet, No Art. A Lunch Bytes Anthology (Onomatopee, 2015) and her writings have appeared in various exhibition catalogues, publications and magazines.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas is an artist who lives and works in London, UK. Reimagined here beyond national borders, New Eelam is an alternative proposal for how a new economic system could evolve, without friction, out of the present one-through the luxury of communalism rather than private property. The venture is represented here by an experience featuring a show-home environment suite decorated by artworks that incorporate and reconfigure original works of art purchased in Sri Lanka’s recent ‘peacetime’ contemporary art boom. The suite also features New Eelam’s speculative promotional film, which asks: How might a nation be reimagined without territory?; How might a state be constituted in corporate form?; and how could a brand communicate as an artist?

Brad Troemel is an American artist, writer, blogger and instructor based in New York, US. He is most well known for his development of the Tumblr website The Jogging, which has received attention for its work in new media art and microblogging. His project Ultra Violet Production House, that is a collaboration with Joshua Citarella, provides customers with high quality material kits and fabrication guidance for all original works. Buyers assume responsibility for the realization of materials received based on tutorials sent to them at the point of purchase.

0 notes

Photo

Carole Cicciu Le Spectacle et l’Incarné

[FR]

Dans un habitat, des portes cachent le contenu d’un placard. Il n’est visible de personne d’autre que l’usager occupant cet espace. Les objets à l’intérieur se révèlent lorsque les portes s’ouvrent. Ils apparaissent alors pour exécuter une parade dont ils ont le secret. Leur mode de rangement s’apparente à une métaphore de cette vie privée, où il est de rigueur de ne pas s’offrir à la vue de tous. Dans une autre situation domestique, ces mêmes objets sont disposés sur une étagère. Organisés avec parcimonie sur cette simple plateforme horizontale surélevée, ils se montrent à l’habitant, aux personnes de passage et à tous ceux qui, à un certain moment, entrent en contact « visuel » avec eux. Ils se tiennent là, présents, immobiles, incarnant leurs fonctions, dans ce qui pourrait être nommé par un état méditatif. Ils sont les résidents revendiqués d’un espace duquel ils participent à l’identité. Ils l’inscrivent dans un contexte particulier et ne nécessitent aucun prétexte pour sortir de leur cachette et exister. Ils sont simplement présents.

Deux typologies se dressent. Elles répondent à deux modes de rangement ; je les définis par l’objet incarné et l’objet spectacle. Le premier participe à l’esthétique générale de l’espace qu’il occupe. Il est nécessaire dans la lecture du paysage domestique, tout en incarnant son propre usage. Quand il est activé, il s’absente de son poste pour occuper une autre plateforme horizontale. Après usage, il est rangé, reprenant ce rôle où il n’est question que d’être. Ces deux positions « être vu / être utile » dressent l’enjeu de sa présence dans l’habitat. L’objet spectacle, quant à lui, est tapi dans l’ombre la plupart du temps. En dépit d’éventuels motifs ou formes le rendant unique, il incarne un produit répondant à un usage. En effet, il n’est de sortie que pour remplir l’exercice de ses fonctions sous la forme de ce spectacle. Entrée en scène, usage, sortie.

Ces deux idées d’incarnation et de spectacle se lient à deux modes de rangement. La mise en avant de la visibilité avec l’étagère, qui s’efface derrière son contenu, et le placard, dont les monolithes pivotant camouflent les fonctions qui l’habitent. Ces deux modes discutent à différents niveaux de la façon dont la domesticité se manifeste. Dans une situation, l’espace disparaît au profit des objets, il est vécu, justement incarné. L’autre schéma tend à neutraliser un maximum l’espace. Un placard a le potentiel de camoufler l’identité d’une pièce et lui ôte toute possible singularité. Son ouverture n’est permise qu’à très peu de personnes. Son usage requiert une initiation, une accoutumance, pour parvenir à localiser son contenu. L’étagère, quant à elle, accepte la transparence et invite celui qui habite comme celui de passage à prendre part, au même niveau, à la grande parade de l’usage des incarnés.

Carole Cicciu vit et travaille à Amsterdam, NL. Elle est diplômée de l’École européenne supérieure d’art de Bretagne, site de Rennes et du Dirty Art Department du Sandberg Institute. Par le biais d’interventions constamment en mouvement, intervenant à tour de rôle de façon pragmatique ou plus contextuelle à l’aide de vidéos, objets, dessins, textes, hôtels, bandes sonores et performances, la pratique de Carole Cicciu traite de la cinématique. Pour cela, elle utilise le langage cinématographique tel un large panel de média pour retourner, extruder, distordre l’espace entre réalité et fiction. Ainsi, elle tend à révéler le potentiel filmique et narratif des objets et des situations qu’elle met en lumière, tout en questionnant le réel comme décor infini.

0 notes

Photo

Fanny Garin Une étude Dôme-Home

[FR]

Fanny Garin écrit de la poésie, du théâtre et des récits. Elle est également interprète et metteuse en scène (pièces, dispositifs). Elle se consacre actuellement au roman et à la poésie, notamment avec la création de la revue Territoires Sauriens en collaboration étroite avec Julia Lepère.

0 notes

Photo

Le Grand Jäger (Guillemette Legrand & Eva Jäger) The Okay System

[ENG]

vimeo

The Okay System explores the ethical implications of our ‘smart' domestic landscapes - a terrain inhabited by mirages and informed by human nature.

—

A film with digital engineering by Filip Setmanuk, (short film and 3D space), 2:51 min., 2017.

Le Grand Jäger is a multi-media creative studio devoted to research-led, critical design projects. Their work focuses on the role brands, media and politics plays in changing our visual language.

0 notes

Photo

N-prolenta Ally Theatre: Barcode Nudes

[ENG]

Italo Calvino’s 1985 series of speeches “Six Memos for the Next Millennium” see a delineation of six new paradigmatic values for literature – Lightness, Quickness, Exactitude, Visibility, Multiplicity and Constancy – to be of prime focus during the third millennium. In Ally Theatre: Barcode Nudes, I have offered a sonic visitation and reconstruction of these values under the span of three minutes elapsed; an appraisal of these values re-figuring the conjectures set forth by Calvino with the new knowledge of our placement in the earliest part of this millennium. The first of Calvino’s values – Lightness – is arguably the only original value Calvino presents, as the succeeding five – Quickness, Exactitude, Visibility, Multiplicity and Constancy – are not values in and of themselves, but effectual conditions of that original lightness Calvino denotes. While Calvino’s words on lightness are themselves set within the premises of the literary, the bounds constituting these premises fall decisively outside the confines of any notion foregrounding objects of lithograph as sole witnesses-to, containers-of and sites-of textuality. This conception of the literary is sector-independent and is of an abstract, qualitative, extractive nature: within, the lightness Calvino directs us to exists characteristically ‘in motion’. Calvino’s asserts a connection between his paradigmatic values and what was for him an impending second industrial revolution and thereby to the realms of economy and data space. This is with reason, for the third of his values within the larger paradigm of lightness translates directly to the English word ‘exactitude’, dictating his lightness to “[go] with precision and determination, not with the vague and haphazard”. I would say this might amount to alarm, and perhaps a sense of bizarro, when we consider that, within the dictates of his words on the third millennium’s paradigm of lightness, Calvino moves to violate exactitude’s abhorrence of the “vague and haphazard” by later stating that “the poet of vagueness can only be the poet of exactitude, able to grasp [subtlety]”. I wonder who or what can a poet be when their primary function here is to grasp, parse and then shed light? Perhaps this poet is as much fleshed individuation as it is algorithm, occupying our environments as ubiquitously as both our bodies and the networks lying in appendage to them? Perhaps their exacting gaze lacks the discretion necessary to allow fluidity, ambiguity and darkness their appropriate spaces, imbuing the goals of precision and mordancy with the same kind of violent potentials as that of lapsed surgical incision? Further along, Calvino’s condition of exactitude continues to complicate the reaches of its own tenets by branching into two directions, one side emphasizing “the reduction of secondary events to abstract patterns” and the other emphasizing “the effort made by words to present the tangible aspect of things as precisely as possible”. In many ways, the first branch may be construed as enumeration of the second; the abstraction of data from event is a way to express tangibility within the realm of the empiric. Our poet, who grasps, then parses, before finally shedding light, must, in order to parse, establish partition between stimuli relevant to the constitution of tangibility and stimuli that interfaces with that constitution. They must produce an architecture that keeps the suspended solidity of the inside in and the qualic, fluid, fantastic inclemencies of the outside on the out. Our poet is, of course, not of fixed location and a more transient notion of domesticity emerges from within the designation of the empirically tangible. The bounds of the tangible surely contain thresholds enabling our poet to surveil the objects and behaviors of its exteriorities, abstract new bounds of the tangible, and amend the contents of its domesticity. Everything touched by the light is appraised by our poet and rendered into the fields of datum. The vague, the naughty, the ambiguous bits are not counted as non-essential, but rather subjected to deeper bouts of quantile operation and valuation, so that more light may be shed upon the face of our poet, proliferating it abound in a range of subtleties and allowing them deeper cognition. After the arrival of the third millennium’s light comes, as a consequence, the unfurling of logos and at a fidelity higher than experienced before. These conditions taken into account, Ally Theatre: Barcode Nudes figures a different branching – positing, first, lightness as a tool for the preparation, vectorization and transmission of data, and second, lightness as an agent for the domestication of darkened, privatized, illegible space. The realm of the domestic, under the enlightening, unceasing scrutiny of exactitude’s poetry of subtlety, becomes a site fully quantile. Ally Theatre therein, as a text subject to the tenets of the third millennium’s paradigm of lightness and as a poetry of subtlety, assumes its own domesticity. Whilst the lyric verses themselves reside in the same home, they exist in chambers of their own, in varying degrees of both privacy and audibility. The lyrics here consistently phase toward and away from foreground: whether this indicates variance amongst the tangible realm’s permeability or variance amongst the fidelity of light’s penetration should remain unclear. That multiplicity of actuality and tangibility, beget by the question of those variances, is largely part of lightness’ consequence. Shedding light upon what transpires within this domesticity is a business beginning with a consultation of one’s own poet of subtlety, a poet that is both the progeny and progenitor of the poet inhabiting the network beyond the curtains of that domesticity, and a progeny and progenitor of the poet netted amidst the fluidities outside the charged, floating space of the domestic. I would say Calvino’s perspective hints at, but ultimately ignores, the spectre of contingency, slippage and bizarro that is made very real by the fluidities of the extra-domestic realm. These contingencies and the fluid multiplicative conditions yielding them have characterized our passage through the earliest parts of our third millennium. In my sonic refiguring of the text, this spectre of contingency was prioritized.

The emerging multimedia artist and producer Brandon Covington Sam-Sumana works to interrogate matters related to currency, transience, narrative structure ans system metabolism. Their interrogations have spawned music projects, objects of generative design, forays into speculative finance, video and visual art. He releases music under the name N-Prolenta. They were born in Fayetteville in North Carolina, US during the mid-1990s.

0 notes

Photo

Salón (Ángela Cuadra & Daisuke Kato) Intimidad en Tiempos de Hiperexposición

[ESP]

En la obra House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, Martha Rosler apuntaba a la creciente invasión de la casa por parte de los medios de comunicación. El hogar se había transformado en un dispositivo militar de vigilancia en virtud de una única ventana, la televisión. El paisaje cercano de la ventana fue sustituido por tubos catódicos con vistas sobre lugares al otro lado del mundo, donde la muerte y destrucción de los otros reconfortaba a la clase media americana de sus preocupaciones diarias. Con la aparición de Internet, este fenómeno se intensifica y se hace recíproco, convirtiendo a los habitantes de una casa en vigilantes-vigilados. Vivimos un momento histórico en el que la confinación en el ámbito doméstico y la continua exposición del mismo a la mirada del otro es la norma. Cómo subvertir estas lógicas ha sido, desde su fundación, una de las preocupaciones de Salón. Cómo hacer la casa permeable sin que esto socave la intimidad de la misma del hogar y de sus habitantes.

Cuando decidimos llamar Salón a nuestra iniciativa, teníamos en mente también un modelo de privacidad permeable, un dispositivo que funcionó desde el final del siglo XVII y fue el germen de la transmisión de las ideas de la modernidad. Este era el modelo de los salones literarios, artísticos y políticos, que pervivieron hasta los albores del siglo XX. Quizá tomar un modelo obsoleto y gastado nos permitía transformarlo y adaptarlo a nuestros fines. Así, la antigua tarjeta de visita, que se entregaba a un público selecto para acudir a los antiguos salones, se transformó en invitación a un evento Facebook a un público más amplio, pero siempre vinculado de alguna manera a nuestro círculo. Varían las formas, pero no las fórmulas. En el fondo de la cuestión, está la idea de hacer comunidad e ir ampliándola. Cada comisario, cada artista que ha pasado por Salón ampliaba el círculo de conocidos y engrosaba un público vinculado por lazos afectivos. Este elemento, la ampliación de públicos por medio de relaciones personales fuertes, o que se van fortaleciendo en el tiempo, es el elemento que exorciza el componente estetizante del apropiacionismo posmoderno. Es decir, no tomamos la idea de los salones por una cuestión nostálgica de un tiempo que fue más bello o más interesante, sino por una cuestión de orden práctico de este tipo de estructuras y es que sus asistentes se conocen entre sí. Como en las sociedades secretas, quien quiera ingresar en ellas lo tiene que hacer necesariamente a través del algún miembro de la misma. En nuestro caso, no es el algo tan drástico, pero las condiciones de privacidad de Facebook hacen que la difusión del evento se realice entre personas que de alguna manera estén relacionadas entre sí. Utilizar las redes sociales como un medio y no como un fin puede permitir generar redes personales fuertes, espacios de resistencia que contrarresten la aceleración capitalista. La casa actúa como cuartel general de una resistencia desperdigada que cada cierto tiempo tiene ocasión de juntarse en un lugar físico para poner en común ideas. En este sentido, la casa es un medio para crear comunidad y generar un lugar de encuentro entre el gremio de agentes artísticos.

Creemos que la forma en que los espacios independientes pueden subvertir las lógicas de institución y mercado pasa necesariamente por el establecimiento de redes de apoyo mutuo en base a intereses comunes, por exhibir sus carencias haciendo de la necesidad virtud para sacar lo máximo de lo mínimo.

Salón es un proyecto que pretende visibilizar la relación entre el arte y la vida. Se trata de crear un espacio expositivo en el taller de los artistas Ángela Cuadra y Daisuke Kato. El modus operandi consiste en la invitación a comisarios para que desarrollen una propuesta en el salón de casa que posteriormente se expondrá durante uno o dos días. Los tiempos de exposición y de trabajo son el resultado de una puesta en común de cada una de la partes implicadas para que las propuestas se inserten en nuestro tiempo de trabajo de manera orgánica. Lo que se pretende es generar encuentros que trasciendan de alguna manera el mero acto contractual entre el espacio expositivo, el comisario y el artista, dando lugar a conexiones más íntimas, así como a propuestas que se engranen en el transcurrir de la vida cotidiana sin hacerles violencia. El encuentro con el público también pretende ser un encuentro cercano, en un ámbito doméstico en el que artistas y comisarios pueden dar a conocer su proyecto desde la cercanía, en un contexto de proximidad. El hecho de estar en un salón en el que hay sofás, se sirve comida casera y la gente está relajada provoca unas sinergías radicalmente diferentes a las que se pueden dar en una galería o en un museo el día de une inauguración. En este sentido, cada exposición es exponerse, exponer nuestra vida cotidiana, exponer una comunidad de personas, generar un encuentro que trascienda el hecho expositivo y ample su sentido. Por tanto, estamos muy lejos del cubo blanco. No se trata de aislar un trabajo en una pared blanca iluminada para focalizar la atención del espectador en un objeto. Dado que la exposición no es aséptica, la gente charla entre sí, se sirven aperitivos, los niños juegan allí… El espectáculo está tanto en la habitación como en las obras que se exhiben.

0 notes

Photo

Charles Savoie Qualia una Fantasia

[ENG]

N-Prolenta / Brandon Covington Sam-Sumana is a multi-disciplinary artist from Fayetteville, North Carolina, home of one of the largest military base in the United States. Their corpus currently comprises two EPs, Driks Ultra Three (2016) and A Love Story 4 @Deezius, Neo, Chuk, E, Milkleaves, Angel, ISIS + Every1else… and Most of All My Dawn Self (2016), as well as a series of videos and performances making up a project entitled Black Hydra, which they describe as: “A set of musical compositions, a set of orated poems, an economic reparations crowdfund initiative and a performance installation project.” Aesthetically, their productions consist of an abstract aggregate of saturated bass frequencies interspersed with fragments of synthetic melodies and hypermodern poetics punctuated by compressed percussing and salves of raucous white noise. As they coagulate, they form a post-R&B wherein afrodiasporic and industrial signifiers collide head-on, and where modernist and postmodernist tropes are modulated at such an intense rate that they dissolve into a phonic whole. Much like the members of NON, an afrodiasporic collective to which they are also loosely affiliated, N-Prolenta primarily employs the sonic medium to produce allegorical dramatisations representing the contemporary condition of stigmatised population for whom each innovation emerging from the military-industrial complex results in the implementation of novel modalities of oppression, fragmentation and repression.

On the Bandcamp page for A Love Story 4 @Deezius, Neo, Chuk, E, Milkleaves, Angel, ISIS + Every1else… and Most of All My Dawn Self, Covington describes the scope of their practice in the following terms: “One of the goals of this project was to use iconographies tied to the complex of technological neoliberalism (think things like QR codes, NFC tags, etc.) in ways that allow me to question more deeply my role as an economic cyborg, being that my entire genealogy is born of the transatlantic slave trade, the middle passage and the events which ensued.”* As Joanna Demers has pointed out, “Electronica’s sounds […] are always heard in relation to something beyond the works in which they are housed, but these linkages to the outside world tend to not to be mimetic as do the sounds in post-Schaefferian electroacoustic music. In electronica, the relationship between signifier and signified is not based on simple resemblance, but rather on conventions that over time have paired a sound with and exterior concept.”** to which she later adds “When electronica musicians construct, reproduce or destroy material, they are perpetuation one of the grandest metaphors in all of music history, that electronically produced vibrations not only exist as objects, but also can carry with them associations and references.” Within Covington’s productions, the present is modulated and operationalised in order to produce complex sonic object presenting themselves not as mimesis of their experience, but instead operate as allegories for existence in western cities in the 21st century, simultaneously fragmented and globalised, technologically enhanced and embedded in the cultural logic of the neoliberal consensus and its genesis. Much like a number of sci-fi works of fictions, they accentuate the features of our contemporary reality in order to create intimate metaphorical representations of their personal relation – and that of the African diaspora – to the network of technological objects operating as prosthetic extensions of systems of oppression and exploitation.