Hello! I am a 21 y/o college student from Philadelphia. The post you see here was an assignment for a course about educational equality in the United States and abroad. Please peruse!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

today’s depressing sight on reddit: a woman being downvoted into oblivion for saying that there is, contrary to what the other posters claim, a vast array of books authored by women prior to 1950 and that, in fact, at one point in time in Western Europe, the novel was seen as an emasculating form and thus avoided by men.

how_to_suppress_womens_writing.txt

21K notes

·

View notes

Text

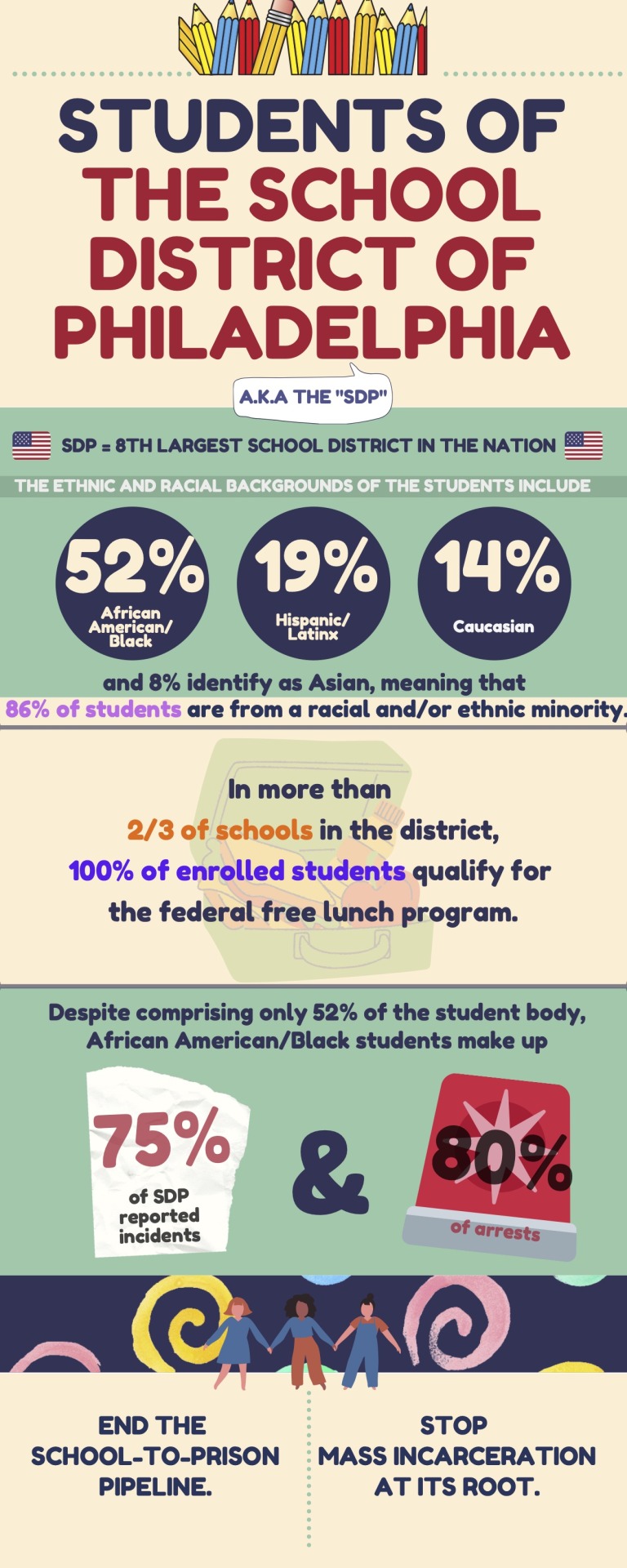

The School-to-Prison Pipeline in Philadelphia

**Long Post Ahead!**

“The nature of the criminal justice system has changed. It is no longer primarily concerned with the prevention and punishment of crime, but rather with the management and control of the dispossessed.” ― Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (2012).

What is the School-to-Prison Pipeline?

If you’ve been paying attention to the news these past nine months, you’ll recognize a familiar racial justice buzzword appearing in the title of the article. The school-to-prison pipeline, like police brutality and the war on drugs, is a part of a larger system of oppression aimed at minority individuals. In this case, minority children in schools. Minority students are more likely to face disciplinary measures in their schools, namely suspensions and expulsions, which have a drastic impact on their lives outside of the classroom. This includes students being more at risk of entering the criminal justice system. It is believed that this system is purposeful— a cog in the machine of mass incarceration that spins around us daily. Gass and Laughter (2015) sum up the school-to-prison pipeline explicitly: “in short, ‘priorities to incarcerate compete against priorities to educate.’”

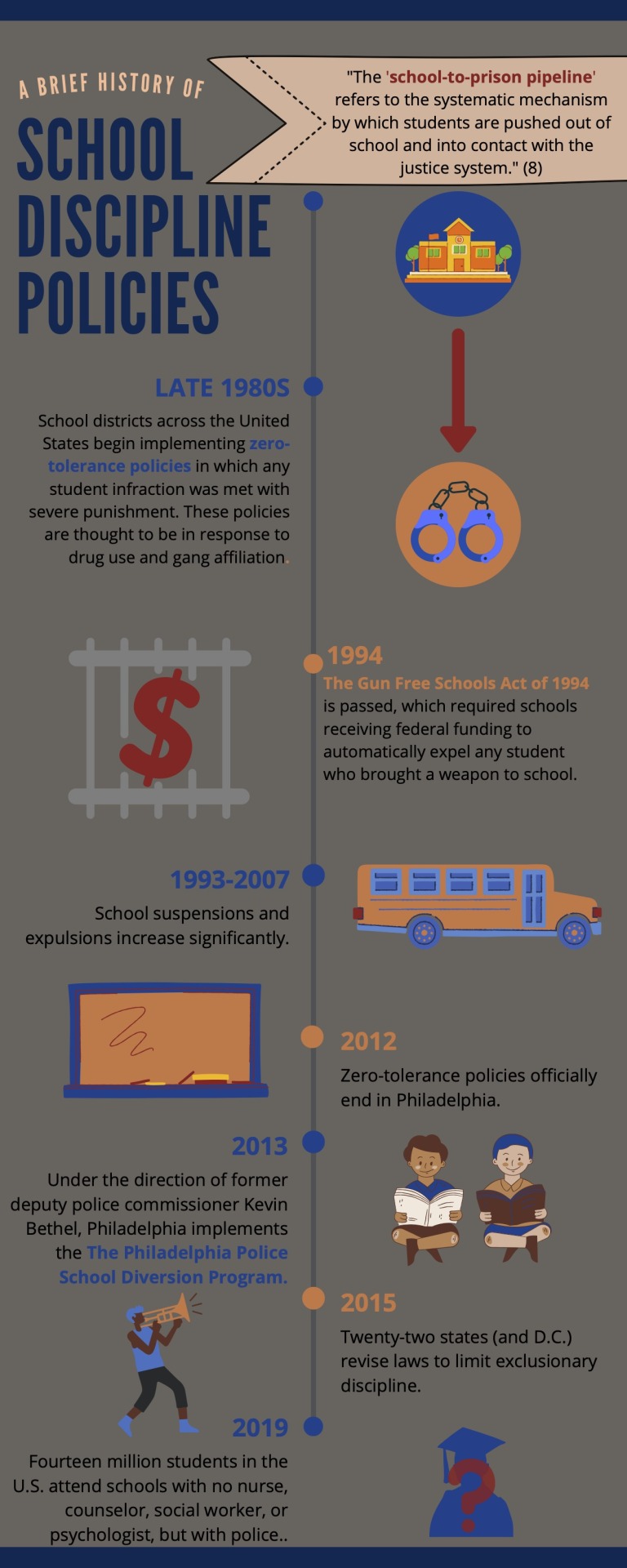

The school-to-prison pipeline is an umbrella term referring to the different policies that have been enacted by federal and state governments in schools to curb misbehavior since the late 1980s. Such policies have included zero-tolerance, metal detectors, school police/security officers, surveillance, and in general, harsher school discipline measures (Goldstein, Cole, Houck, Haney-Caron, Holliday, Kreimer, & Bethel, 2019). It was believed by the SDP that, as Jonathan Kozol claims in Savage Inequalities (2016), “the problems of the streets in urban areas... frequently spill over into public schools. These policies unintentionally affect students of color more so than white students. And, although students living in poverty are always in a place to face more severe consequences for similar actions, being from an affluent neighborhood does not necessarily exempt one from the school-to-prison pipeline. “A recent report by the Government Accountability Office, which relied on a previous set of federal civil rights data, found that racial disparities in school discipline “were widespread and persisted regardless of the type of disciplinary action, level of school poverty, or type of public school attended” (Blad & Mitchell, 2018).

According to a research study on suspension trends in the School District of Philadelphia, there is evidence that “[finds] relationships between suspending students and negative student outcomes, including low academic achievement, grade retention, dropping out, decreased levels of civic engagement, legal troubles, and emotional and psychological disorders” (Park, Karakus, and Lesnick, 2019). Indeed, author of Restorative justice in urban schools: disrupting the school-to-prison pipeline (2016) Anita Wadhwa agrees: “just as people who are not valued in the service economy have been socially excluded and contained in prisons, young people who are unable to perform on grade level or adhere to behavioral norms are often excluded through suspension and expulsion and contained in alternative schools or juvenile detention centers” . From the same study, we learn that black and African American students are twice as likely to be suspended than white students, and Hispanic/Latinx students are 3.38 times more likely to be suspended in fifth grade than white students (Park, et. al). This data is consistent with statistics that have been discovered across the country that points to disproportionate suspensions between racial/ethnic groups. “Moreover, school attendance protects against misconduct, and thus, suspending or expelling students may actually increase future student misconduct,” reports the Children and Youth Services Review. “When out of school, many suspended and expelled students are unsupervised during the day while parents are at work, increasing opportunities for further delinquent behavior” (Goldstein et al., 2019).

Both in-school and out-of-school incidents can result in legal action against students, including arrests, imprisonment, and court cases. “As a result, schools became the primary source of youth referrals to the justice system... transforming exclusionary school discipline policies into a school-to-prison pipeline” (Goldstein et al., 2019). This legal action can have a psychological and physical impact on students, not only marking them with a criminal record from a young age, but also increasing their chances of offending again. The school-to-prison pipeline ingrains ideas of mass incarceration into students from the time they begin pre-school throughout their academic lives and well into their futures.

History of School Discipline Measures in Philadelphia

Following the lead of other major U.S. cities in the early 1990s, the School District of Philadelphia implemented zero-tolerance behavioral policies to try to curb student violence and drug abuse. Those policies continued the long tradition of alienating people by socioeconomic status, ability, and especially, race through the ensuing decades. From 1993-2007, this included a sharp increase in the number of students suspended from school. “For example, although 21.6% of all students in grades 6 through 12 were suspended in 2007, nearly half (49.5%) of black male students in those grades were suspended and 16.6% of black male students in those grades were expelled” (Ritter, 2018).

Later in 2013, police analysts discovered that the SDP was the largest contributor to youth arrest referrals in the city, and a year later, it was concluded that “[Black and] African American students were involved in 75.0% of reported incidents in the SDP and accounted for 80.0% of arrests, despite constituting only 51.8% of the district's student body” (Goldstein, et. al). However, this was also the time that began to see improvements in the school policing system.

After reading the police analysis in 2013, former deputy police commissioner Kevin Bethel designed a diversion program to create barriers to arresting students. His plan saw a 84.3% reduction in student arrests in its first six years of implementation (Mezzacappa, 2020). Still, as of 2019, “14 million students attend schools with police but no counselor, nurse, psychologist, or social worker” (Mezzacappa, 2020).

The Diversion Program in Philadelphia

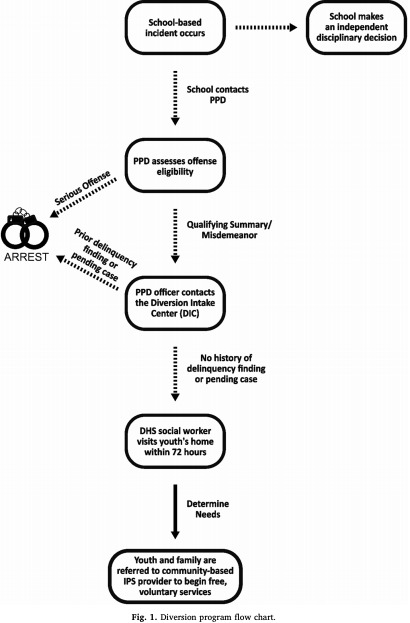

(Goldstein et al., 2019)

As mentioned above, Philadelphia’s Diversion Program is one of the city’s newest measures to minimize minority youth incarceration. Headed by Kevin Bethel, the program’s primary purpose is to prevent the involvement of the Philadelphia Police Department (PPD) in schools as much as is deemed safe by the program. The Diversion Intake Center (DIC) acts as a final check of qualification before an officer is dispatched to a school; if the student meets certain criteria (for example, being under the age of ten), then the PPD concludes its involvement and a social worker is sent to work with the student’s family within 72 hours (Goldstein et al., 2019).

PPD school officers, SDP school safety officers, and some school administrators received 8 training hours for the program, and the PPD officers obtained an additional 2.5 hours of training in adolescent decision making and positive behavior reinforcement (Goldstein et al., 2019). When an incident occurs that requires PPD school officers, the school first contacts their office. If the offence is minor enough, then the call is then transferred to the DIC. Only when this office determines that the student has no history of arrest is the student placed with a social worker.

The program has shown success in its recent years, but the issue of youth incarceration has not diminished entirely; “still, the promises that once beckoned— the promises of technology, material comfort, democracy, human rights, fairness, basic respect, and decency— have not been fulfilled in much of the world” (Isbister, 2019). Already, plans to expand the Diversion Program include branching out to the surrounding community. Training and resources for teachers are also items that the community has deemed high priority (Blad & Klein, 2018). One could add that the students could benefit from more education, as Peggy McIntosh said “My schooling gave me no training in seeing myself as an oppressor, as an unfairly advantaged person, or as a participant in a damaged culture” (McIntosh, 2019). Another researched solution could also include restorative justice, which the U.N. defines as “a problem solving approach to crime that focuses on restoration or repairing the harm done by the crime and criminal to the extent possible, and involves the victim(s), offender(s) and the community in an active relationship with statutory agencies in developing a resolution” (Mccluskey et. al, 2018). Any step listed above would be one in the right direction, but a combination of the above would like combat the issue the strongest. “The lesson for those committed to fighting inequality… is to fashion a new agenda that gives more scrutiny to both racial and nonracial political and economic forces” (Wilson, 2008).

Works Cited

Alexander, M. (2012). The new Jim Crow: mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. Revised edition. New York: New Press.

Blad, E., & Klein, A. (2018, April 11). Betsy DeVos Weighing Action on School Discipline Policy; GAO: Black students disciplined more. Education Week, 37(26), 18.

Blad, E., & Mitchell, C. (2018, May 2). Black Students Bear Uneven Brunt of Discipline, Data Show; Disparity in school arrest rates rose. Education Week, 37(29), 10.

Gass, K. M., & Laughter, J. C. (2015). "Can I make any difference?" gang affiliation, the school-to-prison pipeline, and implications for teachers. The Journal of Negro Education, 84(3), 333-347.

Goldstein, N. E., Cole, L. M., Houck, M., Haney-Caron, E., Holliday, S. B., Kreimer, R., & Bethel, K. (2019). Dismantling the school-to-prison pipeline: The Philadelphia police school diversion program. Children and Youth Services Review, 101, 61-69. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.03.022

Isbister, J. (2014). Promises not kept: Poverty and the betrayal of Third World development. Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press.

Kozol, J. (2012). Savage inequalities: Children in America's schools. New York, NY: Broadway Paperbacks.

Mccluskey, G., Lloyd, G., Stead, J., Kane, J., Riddell, S., & Weedon, E. (2008). ‘I was dead restorative today’: From restorative justice to restorative approaches in school. Cambridge Journal of Education, 38(2), 199-216. doi:10.1080/03057640802063262

McIntosh, P. (2019). White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack (1989) 1. On Privilege, Fraudulence, and Teaching As Learning, 29-34. doi:10.4324/9781351133791-4

Mezzacappa, D. (2020, June 12). Movement for police-free schools reaches Philadelphia.

Park, J., Karakus, M., & Lesnick, J. (2019, March). Suspension Trends in the School District of Philadelphia, 2015-16 to 2017-18.

Ritter, G. W. (2018). Reviewing the Progress of School Discipline Reform. Peabody Journal of Education, 93(2), 133-138. doi:10.1080/0161956x.2018.1435034

Wadhwa, A. (2015). Restorative justice in urban schools : Disrupting the school-to-prison pipeline. ProQuest Ebook Central https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

#philadelphia#activism#mass incarceration#school to prison pipeline#racial justice#school discipline

4 notes

·

View notes