Text

Book Review #5

Title: Ancestral Sacrifice

Author: Kaakyire Akosomo Nyantakyi

Genre: Prose

Year published:1998

Published by: Louisville, KY: Chicago Spectrum press

Summary: Bob Little, a 16-year-old boy with a disability, wanders into the sacred forest while trying to find his way home. The King suspends the celebration of the Ohum festival and bans the eating of the new yam until the boy is found and returned. Mrs. Little is asked to come to the chief palace to assist in the performance of rituals that will allow the search team to entire the sacred forest. Mrs. Little is conflicted because her Christian beliefs do not support the ancestral sacrifice and worship of gods. The search team cannot proceed without her participation in the rituals. After many days, rising tensions in Asana, possible expulsion from the Catholic Church, the removal of the church from Asana, and the death of Faate’s child forces Mrs. Little to take part in the ancestral sacrifice. Unfortunately when the search team returns, Bob Little is not with them - his body was found with a gunshot wound in his head.

Reaction(s): I remember reading this book in senior high school, and it wasn’t until I almost got to the end that I remembered the way the story unfolded. Reading this book about 12 years later, a few things surprised me.

1. The binaries in the story: the traditional vs. the modern; the Traditionalists vs the Christians; Whites vs Natives; the abled vs. the disabled;

2. The representation of disability - when you start reading the story, Bob Little’s conversation and behaviors with other character seem child-like even though we are told he is 16 years. Other characters treat him like he cannot do things without support but we see him throughout make very firm decisions. I noticed Bob had some sort of disability but no one really mentions it until another describes him as ignorant and retarded and his mother does not even react to those labels. The author omitting to say what kind of disability Bob has, could be perceived as his attempt to normalize it rather than ‘othering’ it but the fact that the only time a character speaks about it is in pejorative labels speaks more to silence than normalization.

3. Words in Ghanaian languages are italicized and they stand out as foreign. Also, he provides a glossary list of translations at the end of the book. That speaks to the audience, and I am not surprised he does that because in the preface he learns that this work was part of his thesis while studying in the US. However, when I expected him to use a Ghanaian language he uses literal translation. For example”

Raising the gourd and looking up, he said, “Supreme God of Saturday, you drink not, but seek your presence. Mother Earth of Thursday, drink,” he bowed and poured a drop of gin on the ground (p. 22).

This act describes part of a ceremony and here it is the act of pouring libation to the gods. In Ghana during these ceremonies, the priest does not say, “Mother Earth of Thurday or Supreme God of Saturday.” What he translates as Mother Earth of Thursday is Asaase Yaa. The author could have used the actual words in the Ghanaian language and provide translations at the back on the book like he does for all the italicized words in the Ghanaian language, but he does not.

4. Ataala’s pidgin English is an amazing inclusion in this book. When I read Ataala’s conversations with characters, I wondered how it would be to read a whole book in pidgin or at least a greater part of it since it is spoken among a large number of people. Although today pidgin is spoken by a lot of educated young people as another social code in certain spaces, in the book, Ataala is the only character who we see an uneducated, a Northerner (which ‘others’ him as different to the people in Asana), an abusive man, and Bob Little’s killer who uses English differently.

In the classroom: There is so much potential for teachers to share this book to start some conversations about disability, language registers, and use, and the problematic nature of binaries in societal issues. However, rather than hold this book as a model, we can bring other books that do not have an either-or approach to social issues but show how more complex they are.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Book Review #4

Title: The gods are not to blame: A play

Author: Ola Rotimi

Year: 1971

Publishers: London: Oxford University Press

Summary: King Adetusa and Queen Ojuola consulted the gods as custom demanded in Kutuje “to divine the future” of her first son (p. 2). The gods revealed that the “boy, he will kill his own father and then marry his mother” (p. 3). Painfully and sorrowfully the baby was taken by the King’s messenger to be taken to killed in the forest to avert the horrible prophecy. 11 years later, King Odewale, “the only son of Ogundele” ruled Kutuje (p. 7), King Adetusa had long died. Odewale was married to the former King’s wife, Queen Ojuola and had four children. The people of Kutuje came to the king’s palace to complain. The land of Kutuje was sick. People were falling sick and dying and nothing the people did brought healing to their land. The King sent Aderopo (Adetusa’s second son) to seek answers from the gods. The story ends tragically when the Odewale, Ojuola, the chiefs, and people of Kutuje find out that their king, Odewale is the son of his wife, Ojuola. Ojuola commits suicide and Odewale makes himself blind by removes his eyes from its socket, and banishes himself and his children from the town.

Reaction:

1. The mixing of native language in the drama. When the people in the story sing or speak in their native language, the playwright, Ola Rotimi does not provide translation in English. The native language is mixed with English but reading the native language, you can tell it is not a translation to English. The characters go on, as if, their audience understand what has been said.

2. The abundance of proverbs. It is impossible to get through two pages in this book without coming across a proverb. Rotimi captures the use of proverbs used by elders in this Nigerian town. He does not provide an explanation of the proverb but readers may deduce from the dialogue what the character intends. Sometimes conversations between characters are only in proverbs which reflect the mixing of proverbs in everyday conversation. Some of the proverbs are below (can you decipher their meaning?):

“When rain falls on the leopard, does it wash off it spots?” (p. 10)

“By trying often, the monkey learns to jump from tree to tree without falling” (p. 14).

“The horns cannot be too heavy for the head of a cow that must bear them” (p. 20)

“Until the rotten tooth is pulled out, the mouth must chew with caution” (p. 21)

3. Nigerian ways of speaking. I recognize that not all Nigerians may speak like how Rotimi captures, but there are dialogues between characters that reflect speech patterns and expressions I have heard used by Nigerians around me and also in Nigerian media. For example, when Alaka tells Odewale that his “father,” Ogundele, is dead, Ojuola says: “Awu! And you call that good news? (p. 58)” Interestingly, Rotimi italicizes this word “Awu”. This italicization might not be because it is non-English but because it is simply an expression of shock. Even when Ojuola says to Akala, “Awu! And you call that good news?” rather than “Oh my god! This is terrible,” a response that may be used by a different person who is not Nigerian, Rotimi, in English is able to capture the ways of speaking of Nigerians.

In the classroom: I can see this book being paired with “Hamlet” by Shakespeare or classic tales of fate and the Roman gods influencing human activities. One lesson Odewale gives in his final speech is “Do not blame the Gods. Let no know blame the powers... They knew my weakness...” (p. 71). A lesson these tales of gods influencing human action often draw out. The book could also offer opportunities for discussions of how we treat people of other races, people who do not look like you or speak your language, gender roles in society, and spirituality.

1 note

·

View note

Text

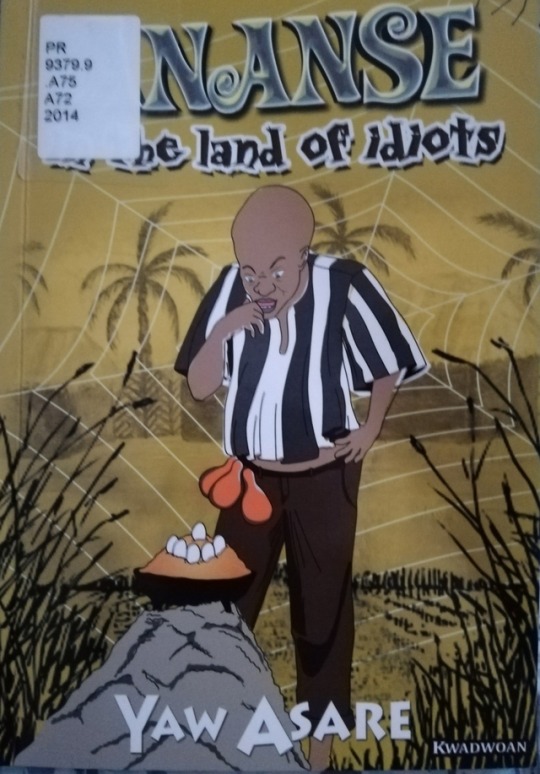

Book Review #3

Title: Ananse in the Land of Idiots

Author: Yaw Asare

Genre: Drama

Year published: 2006

Publishers: Accra, Ghana: Kwadwoan Publishing.

Summary: In this story, Kweku Ananse, “Odomankoma’s Head-weaver; Master Craftsman in the Guild of Divine Craftsmen; Legend of Tailless Tales; One who manipulates creation from the fringers of a vibrant web; Hunter Extraordinary; Fellow of the Cult of Cosmic Linguists; Supreme Strategist; Odomankoma’s Mystery Messenger who flies the skies without wings and crosses rivers without a boat, ” (p. 2) travels to the land of idiots. This land seems to refer to the world. When Ananse arrives at this place, he is caught eating food that has been left as a sacrifice to the gods of the land. Ananse’s actions are viewed as a defilement of the land which could bring about a curse on the whole kingdom. To avoid a curse from the gods, the priestess of the land calls for the King to behead Ananse so his blood would appease the gods. Ananse, realizing his fate, gifts the king, queen, and elder three kente-woven headbands. The king is in awe of the finely woven masterpiece. Ananse promises to weave kente cloths for the princess and the prince who are soon to be married in exchange for his freedom. This leads to deception, seduction, and a murder that sees Ananse gain a chieftain, the princess as his wife, and many possessions from the land.

Reaction: I was surprised by how much information there was before readers get to the beginning of the play. There is a foreword Africanus Aveh, a section about the playwright, an introduction by James Gibbs, and a review by Professor A.N. Mensah from the Department of English at the University of Ghana. I wonder why all these people had to say something about the play. I refrained from reading most of these sections but I read the section about the playwright before reading the story. I realized why this book was so important to so many people. Yaw Asare, who originally wrote this play in the early 90s, passed away in 2002 at the age of 48. This story was one of his first works and his family and friends came together to put this in print to keep the Yaw’s memory alive. Yaw was a teacher, who majored in English and Theatre at the University and had a Masters in African Studies. He was about to start his PhD in folklore and performance theater when he passed away. Learning about the author beforehand gave me a profound appreciation for the text.

Yaw’s style of writing this play comes to life as he paints the picture as if you were in the audience watching the story unfold on stage. In the beginning of the 1st movement (what others might call act), Kweku Ananse directly talks to the audience as if they were part of the story. Kweku Ananse is angry with the audience:

You have turned my hard-won fame into titles of notoriety “Ananse-the-Tickling-Trickster” “Ananse the Cunning Crook” you call me. What praise names to give a hero? Such terrible appellations!... (p. 2)

Ananse in this story still deceives, manipulates, and outsmarts the people around. Ananse, however, views himself as “the prime custodian of ethical, moral, and philosophical norms. In the story, Ananse words, actions, and interactions with people reveal cultural and societal traditions and practices that must evolve to protect the vulnerable in society.

I was also struck by the use of local language and the lack of translation that was provided. These words in the Ghanaian language were also not italicized or boldened to show them as foreign but written just like they would be spoken by a Ghanaian. This shows also that the intended audience here is local and Ghanaian so when Kweku Ananse chants the audience know exactly how to respond.

youtube

0 notes

Text

Book Review #1

Title: In the chest of a woman: A play in six legs

Author: Efo Kɔdjo Mawugbe

Genre: Drama

Year published: 2008

Summary: When Nana Kwaku Duah II is selected as the next King of Ebusa by the dying Queen Mother, Nana Yaa Kyeretwie, his eldest sister challenges the custom where a woman cannot be enstooled as ruler of the kingdom so long as there is a male in the bloodline. She refuses to accept the few lands she is given to rule.

“I am a woman, I agree, but I am not going to indulge in the fanciful notion that men have a priority on leadership talent. The only sure talent men have demonstrated is the ability to cheat and suppress us of the opposite sex. Who are men anyway?” (p. 19)

She questions “Where is it written that a woman can not rule when there is man?” (p. 20).

One of the elders tells her that told that “the history of the kingdom says so” (p. 20). Even though she challenges all the elders, the brother is still made King. However, before dying, the Queen Mother issues a decree, that between Nana Kwaku Duah II and Nana Yaa Kyeretwie, the future ruler of Ebusa after Nana Kwaku Duah II will be given to whoever produces a male heir.

When both brother and sister give birth to girls, Nana Yaa Kyeretwie leads everyone to believe she gave birth to a boy - Owusu Agyeman. She raises her daughter as a boy in order to take the throne. However, when her identity is revealed by as she is going to be executed for impregnating the princess, the king, his elders, and the people of Ebusa have to decide whether to change custom and execute Owusu Agyeman or change custom and let her go.

Reaction: Mawugbe (2008) raises a number of issues in this story including (1) the position of women in society; (2) the persistence of old laws and customs that are problematic today; (3) how both women and men in power oppress the marginalized in society; (4) that people can change laws that subjugate people.

Mawugbe blends the use of English, the Akan language, and Ghanaian ways of speaking to bring to life the characters as if the reader is watching the drama unfold on stage. For example when Nana Yaa says to Ofori, “You fool!...Aponkye...Goat! You’ll soon see what I am going to do to you... Goat...” (p. 23), Mawugbe captures the mixing of English and Ghanaian language that often takes places in interactions between Ghanaians. I dare say that Mawugbe also creatively captures Ghanaian English and not just English as a Ghanaian would speak when talking to other Ghanaians. When the Akosua and Adwoa call each other saying “Eeei Akosua.” “Eeei Adwoa” (p. 37) is an example.

In the classroom: I can see this text being paired with any of the Shakespearean tragedies to initiate dialogue about the role of women in both eras and to illuminate the social injustices that traditions or laws that were written long ago inflicted on different people then and now.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Book Review #2

Title: Grief Child

Author: Lawrence Darmani

Genre: Prose

Year published: 1991

Summary: The story starts with Adu having a nightmare where he is being chased in the forest by a leopard with “red eyes”. Adu’s family (Nimo, his father; Birago, his mother, and Yaa, his younger sister) find him screaming in his room at night with his eyes closing, dreaming: “Papa...Mama... she’s killing me...aaaagh!” (p. 11). This turns out to be the sign of things to come.

The book is divided into two parts. In part one Darmani (1991) we discover why Adu is a grief child. (No spoilers here). All the beloved characters Darmani introduces us to in part one of the book do not make it to part two of the book. (Ok, just a little hint) This story is set in three places: Abenase, Susa, Nsupa, and Buama, rural towns in southern Ghana.

The story is centered around Adu, what he learns from his family, especially his father, and his close friend Yaro and how those lessons help me through the grief he faces throughout the book. The story also demonstrates how friends, teachers, and community members make sure that Adu does not go through part two of the book by himself.

Reaction: Honestly I did not enjoy the book as much as I would have like. The only thing that kept me going till the end was because I wanted to find out what happened to Adu in the end. Darmani (1991) omniscient narrative style does not leave much for the reader to uncover. The author gives the reader too much information about characters and this prevents him (the author) from developing his characters fully.

I thought the story could be much more complex than is presented in the book. There are a number of issues Darmani could have problematized a bit more, like: (1) Nimo not allowing his youngest daughter to go to school while insisting his son Adu, as a boy, should go to school; (2) The discrimination Ghanaians from the North faced from southerners; (3) The two men who dug up gold from the royal graves because they were “hungry”; (4) The people of Buama calling Goma “infertile” because she could not have a child; and (5) Teacher Ofori punishing Adu even though he could see the boy’s excuse was justified.

One thing Darmani develops well is his silence and dialogue to the problem of suffering and pain in the Christian faith. Yaro, the soon-to-be pastor, embodies this when he doesn’t have all the answers to Adu’s question about why God does not God save people from dying. You could summarize the story in these two narratives:

He [Yaro] told me that God was able to to change bad situations to good ones. You [Ama] know that I [Adu] have not seen any good situations yet in all my troubles. But something those words, and the sincerity with which Yaro said them that day, calms my heart every time I remember it. I don’t understand it, but I keep remembering it (p. 145).

He [Adu] had already decided to tear himself away from the crippling, gnawing feeling of loneliness that imprisoned in the past (p. 179).

In the classroom/Practice: I would consider this book as a classic because of the nature of the story and the time in which the story was written. An issue like not sending your daughter to school was “acceptable” 30 to 40 years. Now, with the many government and non-governmental organizations’ campaigns for girl child education the situation today’s reader would frown at Nimo. However, I think having this text in the classroom is illuminates for the current generation certain practices that were normative in Ghana decades. I think this book offers students an opportunity to experience and engage not just with the story of the grief child, Adu, but the many other issues the author does not take up in developing the story. This book should be paired with a contemporary book that takes up a number of social issues in Ghana Darmani does not focus his story on.

0 notes

Text

Book Review #6

Title: No Sweetness Here and other stories

Author: Ama Ata Aidoo

Year: 1970/1995

Published by: New York, NY: The Feminist Press at The City University of New York

Summary: This book is a collection of 11 short stories. Each story shares with the reader a different view of postcolonial Ghana. The stories open a window into the formation of postcolonial identities among different ethnic groups, social classes, and language groups. Ama Ata Aidoo also highlights the experiences of former colonial subjects in the independent country.

In Everything Counts we read the story of a Ghanaian returning to Ghana after pursuing higher education abroad. The woman soon discovers right after her arrival that “every girl simply wore a wig” (p. 3) and “their smooth black skins had turned light-skinned” (p. 4). She felt like she was in a ”citadel of an alien culture” (p. 5).

In For Whom Things Did Not Change we discover Setu, an old man who runs a guest house. When Setu was running this guest house he used to serve White masters but after independence when he started serving Ghanaian elites, he does not notice a difference between how he was treated by the Whites versus other Ghanaians. He asks his new guest “what does Independence mean?” (p. 29).

In In the Cutting of a Drink the story pulls us into a narration of another character who is telling a group of people about his journey to the city. The narrator in this story is surprised about the culture of the city, the ways of speaking, the ways of dancing, and the forwardness of women in the city. He says, “immediately one of them saw me, she jumped up and said something in that kind of white man’s language which everyone, even those who have not gone to school, speak in the city. I shook my head. She said something else in the language of the people of the place. I shook my head again. Then I heard her ask me in Fante whether I wanted to dance with her. I replied ‘Yes’” (p. 35).

In The Message, a grandmother receives a message from the city that her granddaughter who is pregnant has been opened up and the baby removed in the hospital. Certain that her granddaughter is dead she makes her travels to the city. At the hospital, the nurse calls her “a villager” (p. 45)

In Certain Winds from the South, a father leaves his wife and newborn child in the night to travel to South where he has heard that there are jobs. His mother- in-laws questions why he is going, “our men do not go South to cut grass” (p. 50). We later learn that the mother in-law experience a similar situation when her husband left her with their daughter to go and join the colonial army to fight against the Germans because of the promise of a better life on his return.

In No Sweetness Here, Maami Ama had been separated from her husband and was leaving with her only son and taking take care of him by herself. At 10 years old the boy’s parents were formally getting a divorce. During the divorce proceedings, the father gains custody of the boy. Unfortunately the same day a snake bites a boy and by nighttime he dies.

In A Gift from Somewhere, a Mallam gives a family whose baby is feeling unwell. The mother is worried that she will lose this child too like she has lost all her children. The Mallam promises then that the boy will be fine and that he will live. He instructs the mother to go into the house and brings a list of things. When the mother returns the Mallam has left. Years after the visit the boy still lives, and the woman has other children.

In Two Sisters, the older sister is married and is with one child but the younger sister lives with them. When the younger sister begins the date a married man who is known for his affairs with multiple women, his sister is worried. Her husband, however, says that he does not blame her because all her peers are doing the same things as a way to have money.

In Late Bud, Yaaba a little girl who likes to play a lot and does not help at home wonders why her mother always refers to her older sister as “my child” (p. 105) but does not use “my child” when her mother calls her. Yaaba over hears something her mother wants and decides to get it for her. Unfortunately, it lands her in trouble.

In Something to Talk About on the Way to a Funeral, through the dialogue of two friends sitting a bus a reader gets to learn about the story of the deceased person, Auntie Araba. Auntie Araba’s son, the scholar, impregnates, Mansa, one of the girls in the town. The girl’s father is outraged. Auntie Araba decided to take the girl in and take care of her and the baby with the expectation that when her son completes college he will come and marry Mansa. After many years, Araba’s son completes college but he cannot marry Mansa because he had gotten another woman in college pregnant. Auntie Araba is devasted.

In Other Versions, a young man is told by his mother when he gets an internship that he should start giving his father some of the money he makes. The boy complains that he does not have enough. His mother insists and he promised to obey her, confused as to why his mother did not want to receive money from him.

Reaction

I am quite honestly surprised by some of the social issues Ama Ata Aidoo was writing about in 1970. The books present different and complex social and postcolonial realities facing Ghanaians. Each story challenges and questions what it means to be Ghanaian. Is a Ghanaian the person who is able to speak the white man’s language? Is a Ghanaian the one who lives in the village or the one who lives in the city? Is a Ghanaian supposed to be different from the White person?

Most of the stories are told from the point of view of a character in the story and not the author. It allows the stories to capture an oral tradition of telling stories even though it is written.

The physical form on the Ghanaian language in the story is what is a bit disappointing for me. She puts in italics words in the Ghanaian language including certain forms of expressions - excitement, sadness, and pity. For me, that others Ghanaian languages as different and “not English.” However, reading through all the stories I can see how othering Ghanaian languages in the text illuminate how it is positioned to English in the Ghanaian society. However, it still says that English and Ghanaian languages do not hold the same value and place.

I personally have never heard a novel that weaves in how life was during the many coup d’etats in Ghana, but Ama Ata Aidoo also speak to that in Two Sisters

In the classroom

I would have students read this book with some kind of informational, biographical, or historical text that expands the conversation on the social realities of Ghanaian living just before and after independence. It could also open up dialogue on how different things are now compared to 1970 when this book was published.

0 notes

Text

Imagine by Juan Felipe Herrera, illustrated by Lauren Castillo

Apart from the idea that wherever you are from, you can dream, and if you can dream, you can work to realize your dream that is threaded through, the presence and absence of landscape and buildings reveals more about education and schooling.

1. Through something short-lived as flowers, Herrera and Castillo emphasize the importance of allowing kids to dream (imagine) no matter how silly or fickle that dream might seem.

2. I find it interesting that a lot of the young boy dreaming (imagining) happens outside the four walls of the school. It happens when he is outside playing with tadpoles, staring at the night sky, walking back home from school and on and on.

3. The story also shows that although school gave him some words, he already came to school dreaming of possibilities and while school helped, the home environment nursed those dreams.

4. The contrast between the outside landscape, mountains, and trees and the school building in the “winding city” also drew my attention. I wondered, “how come learning takes place in a closed building” while the young boy drew inspiration from the landscape, nature, family, and everything around on the outside. I was drawn to this especially as the image of the elementary school had a fence around it and the doors were shut.

5. When the young boy entered the classroom, one thing stood out to me - the apparent lack of a desk. It seems like there is a desk for him, but it is at the back of the class, and to me, it is almost hidden - like the school did not want him there. But I love that the rest of the story is that of resistance and persistence despite the challenges of everything new and prevailing.

Of course, this notion of didacticism - what’s the lesson in this book - that Tunnel and Jacobs (2013) show was at the center of children’s literature in the 19th century still rings true when I read through this book. I realize that when my only focus is “what is the lesson in the story of the young boy here,” I don’t allow myself to experience the story of the young boy (Nodelman & Reiman, Chapter 2). When I focus on the moral lesson, I fail to see the illustrations of the landscapes, the clothes hanging on the line in the bright sun (reminds of my childhood when I hung my clothes outside on the drying line).

At the back of my mind, I knew illustrations in children’s picture books are important but I had not thought much about the thought process involved for illustrators. For example the thought behind the part of the written story that the illustrator wants us to see. I then wonder, “what doesn’t the illustrator want us to see?” (Sipe, 2001) and what does the illustration allow us to further see?

1 note

·

View note