Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

More-than-human Archives of Post-Military Landscapes in Germany and Poland

Conference Paper, 2021 DGSKA (Bremen): “Zona: Post-industrial landscapes and possible futures”.

Together, human and nonhuman histories reveal that “destroyed”, “abandoned” or largely evacuated, then “rewilded” military zones, far from exhibiting the cessation of sociocultural transformation or a social vacuum, are in fact flourishing social spaces worthy of continued archival analysis. These spaces are characterised by abundance, diversity, and political complexity with many novel convivialities and conflicts. The post-military archives now being inscribed there, are in a more-than-human sense much richer than the simplified agricultural, silvicultural or industrial landscapes dominant before bunkers were built, chemicals were dumped or bombs were dropped.

Post-military zones refers to spaces which were once designated allied bombing targets, battle fields or military training zones, and for which military designation and actions have engendered distinct social-ecological-political futures, including nature conservation. They are often-overlooked productive spaces to engage with “more-than-human” archives which are diversely compiled here from ecological and ethnographic sources. More-than-human archives can inform new narratives of space foregrounding the lives and experiences of animals and other nonhumans, which in turn offer up novel ethical possibilities.

Post-military zones are particularly interesting because they are rewilding. As Anna Tsing puts it, they are undergoing a multispecies resurgence toward improved liveability, spaces whose simplified ecologies of proliferation were channeled by military action but are now becoming more complex and abundant with nonhumans playing a central role.

First, this paper provides examples of human histories of post-military landscapes. I then comment on the perceptions and determinations of risk and opportunity which lead to certain post-military management actions and not others.

Second, research from the life sciences and the stories of local people are brought together to write nonhumans explicitly into those narratives, acknowledging their affects and hinting at nonhuman intentions and politics.

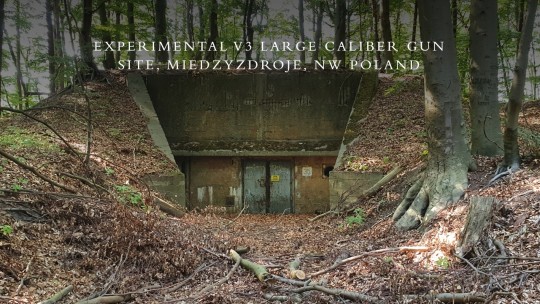

I choose post-military zones in northeastern Germany and northwestern Poland which have seen both spontaneous and more deliberate “rewilding” post-war or post-unification.

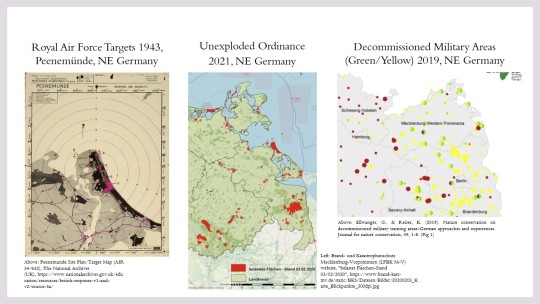

Deep craters and unexploded munitions lie in the sands and peatlands of the Oder river valley and German/Polish Baltic coast where the allied war machine carried out intense shelling and aerial bombing during WWII. Under the years of Soviet influence that followed, new ecologies emerged in these areas and others, abandoned by German forces and by industry supporting the war effort; open sandy heathland habitats, dense beech and pine forests, or carr wetlands and swamps. Some became Polish or East German military training areas covering up to 40,000 ha. incorporating both managed forests and exclusion zones, others became state property not managed by the military, but few saw the same intensity of human use as during the war. On the eve of unification, military training grounds and GDR or Polish government-owned forests constituted an effective buffer zone between East and West. Unified Germany began to work to erase its hard borders, both internal and international, which involved partial demilitarisation of East Germany. The final decommissioning of many GDR-era training grounds in the 1990s and 2000s was coupled with the cessation of intensive rocket testing, artillery and tank training. Similarly, military activities on the Polish side deintensified during the 1990s.

Remote and riddled with explosives, abandoned military hardware, concrete footings, machine-gun nests, trenches, revetments, craters, and densely forested with often difficult-to-extract timber, post-military landscapes offered few opportunities for sale to private investors and became a burden on the Federal Government in Germany. As a result, some sites were handed over to the Bundesländer and in turn conservation charities in the 2000s and 2010s. On the Polish side BirdLife Poland (OTOP) has taken on management of former naval facilities. A DUH ecologist explained that conservationists are drawn to such areas, “the military created a half-open landscape typical for rewilding [. . .] not only created by large herbivores but also by tanks and grenades”.

Post-military landscapes reveal human histories of war and intense military intervention, but are now made rugged and wild through those legacies.

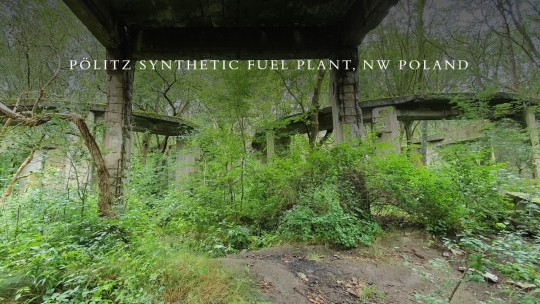

Pölitz synthetic fuel plant is one of 600 abandoned wartime sites or installations in what is now the northwestern Polish province of Zachodniopomorski.

At least 12 bombing raids targeted this site. In perhaps the most extraordinary night of attacks here and on nearby Szczecin on 29-30th August 1944, the Royal Air Force dropped 2200 conventional bombs, 100,000 incendiary devices, and 12,000 containers of a liquid incendiary which set the Oder river ablaze. In addition, 23 British bombers crashed in the surrounding area.

After the war Soviet troops removed much infrastructure and any remaining machinery from industrial sites at Pölitz, in particular stripping the former fuel plant of railway tracks and steel gantries.

In the 1950s some rubble from this site was used in the reconstruction of Warsaw but most was left in situ and by the late 1970s the majority of the area had become overgrown and impassable for vehicles. Polish troops undertook exercises on foot on the site with a small barracks amongst the ruins during the Soviet era, abandoned in 1994. A private school occupied a small corner of the 2km squared site for a time, but went out of business a decade ago. The fuel plant is now a place of dense vegetation, rubble and unstable concrete structures.

Like many post-military areas on both sides of the cross-border Szczecin lagoon, the old synthetic fuel plant at Pölitz experienced wartime destruction, upheaval and population collapse, and then only minor reinvestment during decades of regional economic decline, with recent conservation designation during the 2000s.

In a straightforward sense, the space is “left behind” due to the massive cost of remediation: of removal of reinforced concrete, steel and unsafe structures, above and below ground, and the presence of ordnance. However, the Hydrierwerke is also “left-behind” because the human narratives and practices which surround it are of rejection and abandonment; it is circumscribed by locals as of a bygone era preferably forgotten. The expectation of post-war settlers, many of whom were disenfranchised in the east, was that Germany would soon reclaim this part of Prussia. This expectation of impending displacement, and with it more hopefully a return to their former lands, gave rise to a belief which is only now fading with the younger generation: that there was no history and no future for Polish people here. Furthermore, they wanted retribution expressed through the ruination and rejection of the German fuel plant.

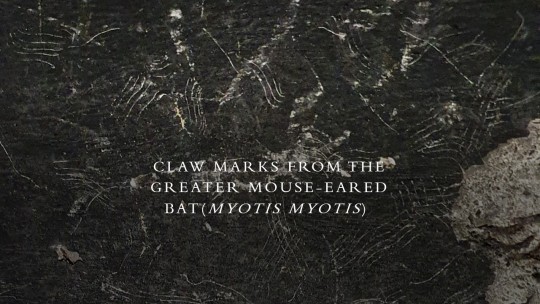

During the early 2000s in preparation for accession to the EU, the Polish government began to designate species and habitats protected areas. The fuel plant is now legally protected for its bats, particularly the rare Barbastelle (Barbastella barbastellus) and Greater mouse-eared (Myotis myotis) bats, which hibernate amongst the ruins.

This is where the more-than-human archive intersects clearly with the human history set out so far, the bats were not placed here, but as rewilders they themselves have transformed political and material futures of the landscape. Bats among the ruins also draws us to interrogate “ruination”. As Ann Stoler argues “The focus [. . .] is not on inert remains but on their vital refiguration”. Perhaps here lie those novel ethical possibilities.

Bat experts from the West Pommeranian University first found scratch marks in the soot on the ceilings of some of the deepest burnt out bunkers in 2003. Their frequency, location, claw spacings and age represent an archive. The bats which made those marks were identified as conservation priority species by recordings of their ultrasonic vocalisations, another archive.

Subsequently further roosts and hibernation sites were discovered and some original sites were vacated.

Currently the greater mouse-eareds' favourite hibernation site is the space beneath a disused railway, inaccessible to even the most adventurous graffiti artists, urban explorers and dark tourists with the only access through a small crack in the floor between sleepers. The decomposition of organic material washed into the space during rains, as well as their own guano, keeps the temperature at survivable levels during the cold winters. Each year bat experts arrive to survey the culvert, and reassert the importance of the rest of the 2km squared site for their survival—the largest site of its kind in Poland. Rewilding by these bats is not simply a side-note in the history of the site, they have both been made present and made themselves present in law, preserving the concrete forms and the forest. Bats and humans have rewilded this space together.

Perhaps it is more fitting to suggest these bats have “wilded” rather than “rewilded” because it is unlikely they were present in centuries past. Cave-like spaces are required for their hibernation: predator-free, preferably large enough to get airborne within, and with stable temperatures and humidities throughout the coldest months. Yet sediments were deposited at the end of the last ice age onto relatively impermeable bedrock and there are no “natural” caves for hundreds of kilometres. Furthermore, due to climate, species mix and human management, there have historically been few suitable trees. The bats are part of a new nature, the product of “wilding” not “rewilding”.

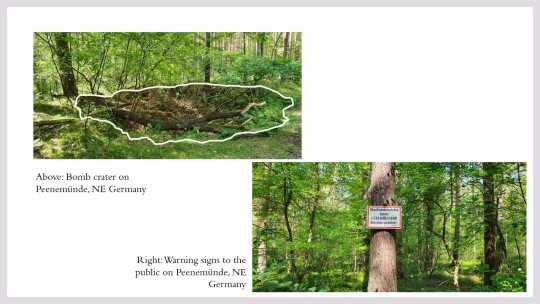

It is not just bunkers which are undergoing wilding in post-military areas, here and elsewhere bomb craters are numerous, also harbouring a more-than-human archive as they fill with life and organic deposits, and as chemicals and shrapnel break down.

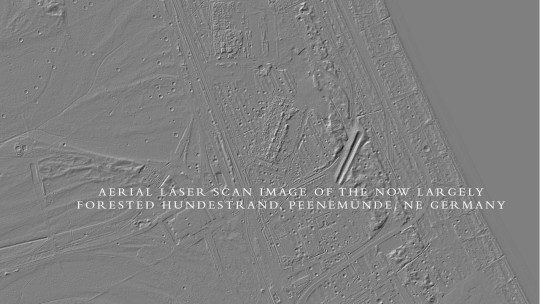

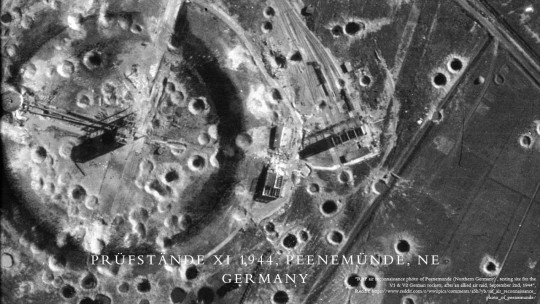

“From 1936 to 1945, the research stations in Peenemünde formed the largest armaments centre in Europe [. . .] an area of 25km²”. The Peenemünde peninsula suffered intense bombardment during the war, particularly its rocket launch sites. Prüfstände 7 on the peninsular is now at the centre of a strictly protected conservation area with access to the public prohibited. Intense bombing of Peenemünde has created a complex topography excluding many would-be human walkers and beach-goers and attracting others, due to dense afforestation, military warning signs, and exclusion zones for rare breeding birds. Peenemünde exhibits “bomb ecologies”, a place in which according to Zani Leah, “war profoundly shapes the ecological relations, political systems, and material conditions of living and dying”. The bomb craters collect water, and remain damp through the height of summer, partly due to “bombturbation” or the compaction of soil during the blast. Craters are dominated by deciduous trees—sycamore, birch and alder which grow readily on the steep sides and collapse inwards due to the loose sandy soil, widening the crater in the process. Sheltered deadwood habitats in the bottoms contribute to a mild microclimate and the craters have relatively high abundance of saprophytes, particularly invertebrates, which attract small mammals, birds, and wild boar who also use some craters as wallows. The black anaerobic mud layer and mulch which has formed over 75 years at the bottoms of those craters is full of beetle carapaces and bones, as well as empty beer cans, human waste and banana skins in more recent layers, evidence of novel ecological interactions and a window into a rich more-than-human archive.

Soils also hold a record of chemical decay which is simultaneously an archive of organic compounds, bacteria and fungi that break those chemicals down. Borrowing from Zani Leah, military waste “may be better understood as a kind of surreal substrate to everyday life”. For instance at the fuel plant soils have high concentrations of microbes that consume contaminants such as diesel. Bombing generates an important chemical baseline from which we might construct a more-than-human archive of decay. An estimated 1.27 million tonnes of bombs were dropped on Germany. Perhaps 10% failed to detonate and many would only partially detonate, leaving up to 100,000mg per kg of explosive in the crater soil, as well as metal casings. Combinations of RDX, TNT and ammonium nitrate were used as the fillers for explosive bombs used on industrial targets in the Oder Delta, and benzole for incendiaries. Remarkably, these chemicals are sometimes entirely undetectable at wartime bomb sites. The chemicals that emerge, as microbiota and weathering break explosives down, are so radically different that humans pay them little attention. In the case of TNT, more than forty transformation products have been identified including nitrobenzenes and azoxdicarboxylic acids. TNT and RDX may also be metabolised by plants and trees. These transformation chemicals are an archive of nonhuman reconfiguration of the material and the social on wilding sites.

I have argued that post-military wilding sites offer particularly rich more-than-human archives arising from, at the time catastrophic, socio-ecological rupture. Bat scratch marks, crater deposits and chemical transformation products are just the tip of the iceberg. Yet it is clear from these modest examples that archival work is itself always interpretation and whether wilded spaces are, as Anna Tsing suggests, potentially more liveable, is as ever, a matter of asking “for whom?”.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Wolf Cubs Caught on Camera

“And now," cried Max, "let the wild rumpus start!”

― Maurice Sendak, Where the Wild Things Are

In July this year, five Rewilding Europe wildlife cameras were set at secret locations on the Polish side of the Oder Delta. Almost straight away, one camera captured an adult male wolf patrolling in the early evening, and days later two of this year’s offspring were caught tussling with one another before disappearing into the thicket. The camera was positioned following a chance encounter with five very young wolf cubs playing on a quiet road, an extremely rare sighting and proof of denning in the Oder Delta. “From a distance they looked very much like boarlets [young wild boar]”, said the witness who was driving. “But one cub lingered long enough as I got near to show it was a wolf”. It was worth following-up with a camera trap.

These were not the only wolves captured during the month the cameras were recording. Other cameras were set on a new “green bridge” spanning a motorway. The “green bridge” is one of four along a stretch of new motorway, designed to allow for greater connectivity for wildlife across the Oder Delta. When the cameras were set the bridge was only six months old still with very little vegetation. Cameras were triggered not by one adult wolf crossing, but two. It even captured the moment one wolf gave chase to a roe deer right above the road on which traffic can be heard. Apart from the wolves, the bridge was used by red deer browsing the soft new growth, hares courting and appreciating the open space and dry topsoil, and foxes hunting on wood piles created from trees uprooted during the construction of the bridge.

Back in the forest away from the busy motorway, another camera captured heart-warming moments shared between a roe deer doe and her fawn as she stopped to nuzzle and clean her baby. Later that week, she looked on as her fawn darted at full speed through the same forest clearing, barrelling through the bushes on the other side with newfound speed. Two adult badgers passed almost nightly along the same path and at one point the mother brought her three youngsters, no doubt learning to find their way in the forest and make it their own. Later, those same adult badgers were startled by the cackles and yelps of the young wolves, from which they beat a hasty retreat.

Sadly, the cameras also hinted at tragedy faced by animals in the wild. One night a wild boar sow moved through the forest clearing alone with just one young boarlet close at her side. It is almost unheard-of for a sow to give birth to only one, more commonly six or more. Many are hit on the roads, die of disease, or simply of dehydration and malnutrition if their mother is shot or otherwise killed. Camera trapping elsewhere in Poland has shown up to 50% of adults in a group can carry visible injuries from hunts, but happily here adults and young appeared healthy. The female roe deer too, at first appearing many times with her fawn, seemed to become separated in late July when the young animal would still be extremely vulnerable. Videos after this time show the same doe hurriedly passing by alone. Roe deer are important prey for lynx. Two further cameras were positioned where an adult female has often been seen over the past decade. Although the lynx may simply have evaded the cameras, it is also possible the Oder Delta’s only known resident lynx has moved on or died. Female lynx often inhabit a defined territory for years whilst males roam much greater distances. Lynx scat, probably from a different individual, found at the base of a “green bridge” some distance away offers hope that others may settle, traversing the many human obstacles in their way.

The wealth of information we can gather from camera traps can contribute to our scientific understanding of wildlife presence, population and behaviour. But as shown here, it can also allow us to begin to appreciate the stories of individual animals and try to become more sensitive to their lives and needs. The places and animals featured here lie right at the heart of Rewilding Oder Delta’s strategic vision for a wilder future. Video evidence points to the healthy return of keystone species such as the wolf. Very soon it is hoped videos of the mighty European Elk and Eurasian Lynx will be captured, as they too are beginning to join the wild rumpus here in Oder Delta.

0 notes

Text

Seven Seafoods to Avoid

Reducing consumption is critical if we want to live in a more abundant world, rich in wild places and wild things. We hear regular calls to “avoid this” or “reduce that” for the sake of the climate, a proxy for continuity of things we value. As we know from recent climate debates around veganism or vegetarianism, some actions are more impactful than others.

Becoming vegan or vegetarian is a big step for many, especially in households or communities where meat and fish is not only at the heart of most meals but culturally important. Are there ways to become a little more vegan without rocking the boat? And at the same time have the greatest possible impact?

There is no substitute for buying less meat and fish—or buying less of everything overall for that matter. However, there is one food group with which it isn't too difficult to cut some ties, and which is estimated to produce more carbon that the whole of Germany each year. That’s seafood harvested by bottom trawling and dredging. Bottom trawling and dredging in the UK has wiped out 94% of fish and globally produces 1.5 gigatonnes of CO2. One study over just two years showed in the North Sea and Irish Sea combined over 50% of the seabed was scraped clean. Although some argue “too little too late”, in 2021 the UK was able to ban bottom trawling in some of its protected areas following Brexit. Bottom trawling is popular with commercial fisheries because it captures almost everything, including mid-water pelagic species. It also scoops up those of no commercial value. It’s the equivalent of clear-felling a rainforest from above. Dredging just uproots the “forest” without capturing the creatures that flee, but of course many animals do not escape or do not survive.

There is good reason to stop buying bottom trawled and dredged products as not only does it continue in most UK waters but much of our seafood is imported from regions where it is the main method of capture.

It isn’t easy to know precisely which seafood has been captured in this way because the species isn’t much to go on. However, there are wild species that can only be captured at commercial scale by bottom trawling and dredging. If you buy them or eat them, you are almost certainly contributing to the problem.

Here are seven of those wild-caught products commonly eaten in the UK. Lemon sole, dover sole, plaice, oysters, mussels, scallops and prawns.

Could you cut these out of your diet?

0 notes

Text

Summary Response to England Tree Strategy Consultation

Rewilding Britain, along with a raft of other environmental organisations including The Wildlife Trusts, The Woodland Trust and The National Trust are callling for increased woodland cover in England. Between them these organisations have over 6 million members. Pledges to increase tree cover were also popular among voters at the last general election. The Committee on Climate Change has recently made the case for increases in tree cover and recent statements from politicians have been positive, particularly from The Rt Hon George Eustice MP and The Rt Hon Lord Zac Goldsmith. To be taken seriously as a world leader in tackling climate change, the UK must lead not only on renewable energy but also on landuse reform to protect, enhance and expand woodland. England’s tree cover now stands at just 10% against a European average of 38%.

There appears to be a consensus that the time is right to action the commitments made to improving nature and acknowledge the risks if we do not - losing yet more wildlife and woodland on an island already highly degraded in this respect. The question now is how exactly woodland cover should be increased so that it works for wildlife and people. Current proposals are not ambitious enough and overly complex.

Rewilding Britain have provided ample evidence in support of natural regeneration. It can be significantly less expensive than planting trees. The ecosystems that develop in this more organic way are more resilient, reduce flood risk, support pollinators, replenish soils, boost vulnerable species, offer variety and interest for people visiting sites and have a favourable net carbon impact when compared to energy-intensive planting. With natural regeneration, plastic tree guards are unnecessary and therefore do not need to be removed years down the line, ongoing maintenance too, or 'thinning' except for cutting paths for visitors where appropriate.

Planting trees does have value for engaging volunteers and making them feel that they have contributed and invested in the land but paying contractors to plant the majority of new woodland greatly limits what can be achieved. The speed at which new woodland will take hold on its own will vary but much of England, particularly the lowlands, is surprisingly fecund in this respect. The time frame would not be significantly different compared to planting in some areas.

In pushing for natural regeneration, we must open up our notion of what constitutes "woodland". Scrub (e.g. thorn, elder and bramble) is valuable. It is not simply the poorer underdeveloped precursor to closed canopy woodland. Our inherited mixed coniferous/deciduous woodland is also valuable, and the removal of interspersed conifers is another unnecessary expense based on overly rigid concepts of nativeness and nature - one only has to look to the wildlife-rich mixed forests across much of Europe.

In developing its new Tree Strategy, England has the opportunity to greatly reduce the operational costs of woodland creation and maintenance and improve outcomes. It must use those savings not only to provide additional landowner incentives but to invest in education around the value of natural regeneration and low management approaches - this includes education of forestry professionals, farmers, estate managers and even conservationists, in addition to the wider public.

With woodland creation simplified in this way with minimal capital required, incentives can be redeployed towards increasing the total area of land under woodland - or rather wildland - creation schemes by offering competitive acreage payments.

0 notes

Text

Trees on peat: the jury's still out

Back in January this year the newly appointed Chief Scientific Adviser for Defra (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) spoke at Magdalene College, Cambridge. We discussed afterwards the pros and cons of afforesting peatlands. These make up a significant proportion of the UK’s less productive land area so they are important in efforts to mitigate climate change and biodiversity loss.

Prof. Henderson argued it was case-closed, “trees and peat should be separate”. Afforestation could not be allowed on peat because it would cause the release of greenhouse gasses due to the resulting lower water table and the decomposition of material which is then exposed to oxygen. Confusingly, limited exceptions might include where trees are already growing on peat, for instance Kielder Forest, and their removal might be damaging. In this case immediately replanting with fast-growing species might be the best option. But in general, “no” to trees on peatland.

This got me thinking, I’d seen plenty of instances of boggy peatlands covered in aspen, willow, birch and cottonwood elsewhere in North America and Europe, very often celebrated as healthy ecosystems full of life. There are up to eight metres of peat under parts of the Amazon rainforest, which only exists due to thousands of years of leaf fall and other vegetation decay. In fact this process is what makes many forest areas carbon sinks.

On a broader point, dividing up the landscape into neat polygons with distinct land uses, “peatlands or woodlands” seemed a counter-intuitive strategy for promoting nature which is inherently messy.

Just to be sure, Prof. Henderson conferred with colleagues at Natural England and Forest Research and was of the same opinion still so I put the issue on the back burner.

Fast-forward to April and a BBC article piqued my interest again, “Climate change: UK forests 'could do more harm than good'”.

It made the same claim (sensationalising), that planting trees on peatland was bad news. This triggered a robust response from the industry body Confor (Confederation of Forest Industries) who were upset that they hadn’t been interviewed stressing there were no plans at all to plant on peatlands - how dare the BBC journalist insinuate that planting on peat was even on the cards?

Both Confor and the BBC journalist are missing the interesting point here. Trees on peat may be of net benefit to biodiversity and perhaps even climate.

The BBC article picks up on a section in the latest Natural Capital Committee report which does indeed argue that planting trees on peat would raise greenhouse gas emissions (it doesn’t cover natural regeneration of woodland on peat). However, the report doesn’t provide strong evidence to back up its claims.

The report cites Ostle (et al. 2009) who advocate for ‘regeneration of vegetation’ on bare peat and maintaining the water table without specifically commenting on peatland afforestation. In another relevant claim, the report references only Sloan (et al. 2018), who in fact argue that there is no clear evidence that afforesting peatlands would necessarily generate higher emissions, and that there are multiple mechanisms which mean the exact opposite may be true.

My hunch is that two assumptions need challenging: First, in the long run with the effects of climate change, that tree cover would necessarily be detrimental to the water table compared to the alternative of grassland, moss or heather. Second, that the overall combined carbon content of peat soils and life above ground would necessarily be depleted even if the water table does drop in places due to afforestation.

Given the uncertainty around peatland sequestration, perhaps we should focus on wildlife and recreation instead. There is a growing appetite for more trees and wildlife in Britain’s uplands and there is no doubt that more complex vertical vegetation structures, including shrubs, bushes and trees, provide for a greater variety of animals, fish and birds. Let’s be more imaginative when it comes to peatland management and restoration, we may be pleasantly surprised by the outcomes.

0 notes

Text

Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: Moral Values in Management

“Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: Moral Values in Management” was a talk I gave to the Cambridge Conservation Initiative Annual Symposium 2019

Background

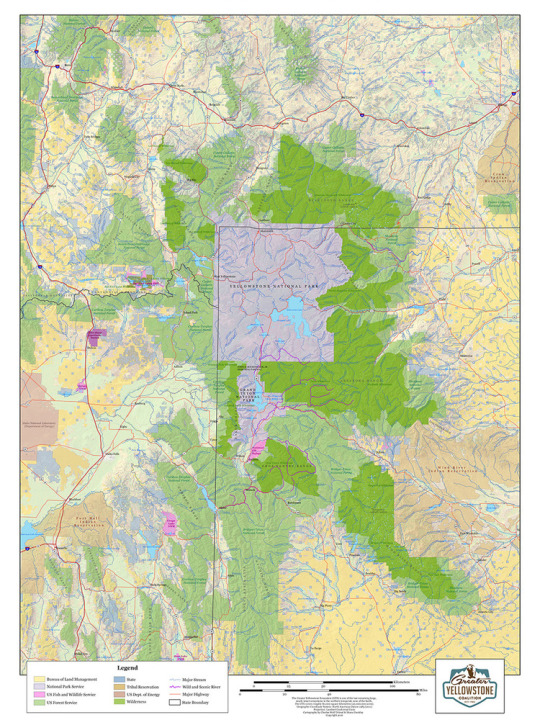

The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE), centred on the Yellowstone National Park, is an area of twenty-two million acres — over a third of the total land area of the UK. Spanning part of three western states in the USA, Idaho, Wyoming and Montana, the area is comprised of five national forests, three national wildlife refuges, Bureau of Land Management holdings, state lands, two national parks, Indian lands and five million acres of private land. Within this landscape milieu, wild things are appearing in places they have not been seen for generations. From the Yellowstone National Park at the GYE’s centre, bison, grizzlies and wolves are being restored to the periphery.

As the simultaneous restoration of the ‘full suite’ of wild things, rewilding began with the reintroduction of the wolf in 1994-5—the last, large animal present during pre-European times to be returned to the Yellowstone National Park. Through subsequent rewilding practices, its range and population increased, and similarly for the grizzly bear (grizzly) and bison although some of those changes preceded the wolf by several years. Beyond the boundaries of the Park, wild things, increasingly, are hopping fences, sinking their teeth into cattle, running from hunters, scrumping for apples, grazing gardens, and occasionally injuring and killing people. Rewilding in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, to put it simply, is ‘restoring wild things’, significantly, ‘restoring bison, grizzly bears and wolves’.

Before reintroduction, only the occasional wolf had been sighted and no viable packs seen for almost 100 years. Wolves number approximately 100 individuals which reside mainly in the Yellowstone National Park and 500 in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. The leading cause of death overall (around 80%) is humans, especially by hunting, followed by other wolves (which is the leading cause of death inside the Park) and next, disease.

Bison, which have a much less extensive range in the GYE, were estimated to number 4,527 in August 2018 before this winter’s cull and hunt. The leading cause of death is again humans. The National Park captures and sends to slaughter several hundred each year while hunting makes up the rest. Last winter just over a thousand were killed. Wild bison were thought to number around 23 individuals following their near-total eradication during the 19th century. Captive breeding and much later, bison release, occurred in the Park during the 20th century. Bison have only begun to migrate beyond the Park boundaries since the 1980s.

In 1975, there were 136 individual grizzlies in the Park. Now they may number 1,000 in the GYE although good estimates are notoriously difficult to obtain. They were recently removed from the endangered species list, many feel prematurely. They were relisted in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem by a Federal judge in 2018. Their range in the GYE has expanded significantly over recent years and there is much talk of grizzlies traversing agricultural and developed areas to the NW of the GYE. This could connect them with populations in the Northern Continental Divide Ecosystem, and thus Canadian populations. Humans have controlled grizzly numbers here for over 100 years and their low in 1975 was generally thought to be a result of Park policy. This included removing open rubbish dumps resulting in the bears’ dispersal, then the killing of bears which roamed outside of the Park.

I find in my research that the landscape here tells a recent and surprising story of humans restoring wild things. I’m not so interested in the science of which predator eats which prey, changing which ecological indicator (although it is fascinating). I am interested in WHY people rewild. Really WHY, as in deep motivations, and for that matter why they fight this kind of thing. This is a question of love, fear, enchantment and anger around wildness, which is totally mixed up in what’s going on in wider society; cultural questions of identity, heritage, belief and power. Some people are passionately engaged in occupational practices aimed at expanding the ranges and numbers of wolves, bison and grizzly bears over a huge area already occupied by people. Others are radically opposed and dedicate much of their working life to resistance, politically, or very directly through the barrel of a gun. What is fundamentally meaningful and motivating to these groups?

Surely, it’s not all about money for the objectors? Or on the other side, purely about scientific data for the advocates?

Why do some of these people advocate for more rewilding? And why do others resist?

Methods

“Not everything that counts can be measured; and not everything that can be measured, counts.”

I like this quote. Amongst many esteemed biologists, ecologists (natural scientists) here, it helps to explain why I spent six months doing empirical research in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, measuring precisely nothing. Instead, I undertook semi-structured interviews and observed people at work over extended periods of months to try and make sense of the things which count for them, but can’t be measured.

My research population included those whose work centred on three iconic wild things: grizzlies, bison and wolves because these species emerged as quintessential embodied wildness for both those for and against rewilding. I focussed on land managers, state and federal scientists, activists, lobbyists and campaigners in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and not least those who have lived and worked on the land their whole lives, but who don’t have a college degree.

Problem

All are battling with the reality that their work, their measurements and claims to knowledge, often don’t count politically or socially. Wildlife scientists and ranchers alike struggle to articulate why their knowledge often doesn’t count in practice. In fact, hidden moral values are at play.

If there is one take-away from this talk, it is that if you believe in rewilding, it seems you will need a range of means of articulating the ways in which wildness is meaningful and valuable; in which it counts. Science can only go so far in winning hearts and minds. Gaining trust must involve acknowledging that all science has bias: acknowledging that there is no objective understanding of what a ‘good’ landscape looks like and how it works best. There are only contingent understandings.

Let me give you an example from the Yellowstone which demonstrates the schism.

Recent publications on grizzly bears in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem have shown quite convincingly that grizzly bear movements through landscapes can be predicted with a surprising level of statistical certainty. Potential pathways between isolated populations have been mapped with at least one clear implication, that we now have an excellent idea of where best to create corridors and we have the evidence to justify strategic land restoration and preservation.

But this research, its conclusions and its implied applications are based on two subjective assumptions: a) there were more grizzlies over larger areas at some (rather arbitrary) point in history and b) therefore; there should be more again. Actually this is more about belief.

For many this science counts for nothing. From diverse professional backgrounds, some looked at this type of research and were totally appalled that these groups even got funding or contributors were even in a job. They cast it aside to get on with what they felt was the real business. For instance, making wildlife management or planning decisions based on human need, lobbying for the cattle industry, and running farming operations. Activities that are equally values-driven. It’s not easy to define and measure why they cast it aside with such disgust, the same as it is tough to define and measure why the researchers spend years of their life contributing to wildlife conservation through science, but whatever the reasons, they sure count.

So let’s have a look at some of the cultural and historical factors which I believe influence decision-making on the ground, and produce conflict through opposing values in Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. As I go, parallels should emerge with rewilding in Europe and the UK. At times, there was something oddly similar about the ways in which people in very different cultural and environmental contexts, the western USA and Europe or the UK, think about wildness.

So first, what are some of the reasons people value wildness and wild things in the GYE?

Take the ‘wolf-watchers’ for instance, who spend each day watching wolves, most often in the northern part of the Park. They generally know one another, hike together, and attend the same social events in the Gardiner, Livingston and Bozeman areas—Park and Gallatin Counties, Montana. Most are from ‘out-of-state’ but now live in the area permanently or for months at a time. ‘Wolf-watchers’ are generally wealthy, retired, semi-retired, or have business interests elsewhere that do not occupy their time.

Wild things, for the ‘wolf-watchers’, are profoundly beautiful and reminiscent of an imagined, perhaps beguiling past before their eradication, perhaps even before people. It was common for the wolf watchers to refer to key American authors, sometimes directly quoting them: Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness (Abbey 1968) and A Sand County Almanac (Leopold 1970) were especially well cited. Thematic literature informed discourse and even expressions of feeling. Their focus on wild beauty in conversation regularly drew upon ideals which can be traced back in American literature. This was fairly unique amongst a relatively small number of wealthy in-migrants, generally college-educated and with a passion for restoring wildness.

Wilderness ideals in literature began to become formative of beliefs around wildness in the 18th century. Roderick Nash claims of its earliest aesthetic appreciation, that by the mid-eighteenth century, “wilderness was associated with the beauty and godliness that previously had defined it by their absence”. In the 19th century, the ‘sublime’, which “captivates while it awes, and charms while it elevates and expands the soul” entered into aestheticism of ‘nature’ also informing beliefs around wildness. Later, the American literary contributions of Henry David Thoreau were influential: famously, “this world is but a canvas to our imagination.” and “in wildness is the preservation of [that] world”. Also, of John Muir, and later still, Edward Abbey who wrote extensively on wildness, “out there is a different world, older and greater and deeper by far” (1968). The beauty of the ‘ecological wholeness’ of nature came to the fore with Aldo Leopold (1887–1948) who also led a paradigm shift towards aesthetic acceptance of carnivores, contrasting to an earlier time in which, for instance, statesman and wildlife enthusiast Theodore Roosevelt reportedly described wolves as “beasts of desolation and waste”. Wild things now embody a positive and influential aesthetic of wildness. This is only reaffirmed through experience for the wolf-watchers who also perceive beauty in every howl, growl or bellow.

Aesthetic appreciation is primarily why they do what they do, also providing important public, volunteer and financial support to the rewilding cause.

Here’s an example of another way of moralising in support of wildness.

A government wolf biologist I interviewed, angered by degradation of natural processes and biodiversity, pins his hopes on the wild wolf. He foregrounds its scientific value as a keystone species within a natural ecosystem, an ecosystem which is not complete, as he believes it once was, without the wolf. He does not question concepts of naturalness, categorisations of that nature, or that a particular past was necessarily more “complete”. For him, this ecosystem, and the wolf’s functional place in it, is somehow fully scientifically knowable and measurable. It is the moral imperative to defer to science, which favours wolves for the government biologist. They have historical primacy in an ecosystem which is imagined to have functioned “correctly” in a time before European settlers. This reveals a belief in the ‘goodness’ of a particular past. It also reveals a certain belief in the system, the science and the scientific and bureaucratic structures which give it legitimacy such as the National Park Service and ultimately the democratically elected US government. In parts of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem this faith was largely absent. It was particularly marked among Federal, less so State, employees.

So, what are some of the reasons people do not value wildness and wild things in the GYE?

I want to read a passage from my field diary.

The cow heaved painfully, sucking air through its torn, bloody nostrils. The whites of its eyes showed clearly as it tried to sense its surroundings, exhausted and unable even to turn its head. As ranchers pulled up in large trucks one at a time and took their place at a respectful distance, the cow followed the sounds with just one remaining ear. Terese briefed me so that no one else could hear. It had been chased by feral “pit bulls”—terriers—, separated from the herd, and had run, terrified, into a cattle grid where two legs remained deeply wedged. Its open side glistened in the afternoon sun, crimson and specked with flies, tooth marks clearly visible. Two burly men dressed in flannel shirts and cowboy hats tried to slide a wooden plank between the suffering beast and the bars of the cattle grid in an effort to lever it into a position that it might escape. It had no fight left and made only feeble movements with its free hooves. The ranchers then roped the cow to the tow bar of a pickup, attempting to drag it free. As the rope tightened, the man with the beast grimaced and gestured urgently to stop. The cow’s leg was broken and its innards began to spill through the hole in its flank. None of those present owned the cow or the land. The owner, was unreachable on his mobile and none were willing to carry out the inevitable, put a gun to the animal’s head, without consulting him first. The mood was sombre and the ranching men and women became largely silent for several minutes. Few shifted their gaze from the animal, close to death, and as the nearby road quietened also, the only sounds were the wind in the couch grass, and the fading breath of the cow. Although they tried to hide it, all were visibly upset. One or two returned to their trucks to sit alone, but they didn’t drive away. The animal was worth between $1,300 and $2000 depending on breeding potential, not a huge financial loss and none at all to the neighbours present. It was one of many which die or are severely injured by pit bulls each year on the Wind River reservation. It occurred to me that I was witnessing mourning. The emotion was palpable and the respect for the soon-to-be-deceased unshakeable. The ranching folk stood in reverence for the cow itself.

Typical for many ranchers I spoke to about wolf and bear attacks: the emotional impact of wild things harming domestic animals, which they care deeply about as the fruit of their labour and respect in some way as sentient beings, was hard to grasp in interview alone. Experiencing the ‘mourning’ gave such descriptions deeper meaning.

Here is an extract from an interview with another rancher and lobbyist.

“after they [the wolves] mauled this one cow up so bad that I had to shoot her… and the cows tore down the fence in the middle of the night, and they were all running down the highway, and I'm out there at 5 o'clock in the morning trying to push them back, that's when I completely lost it.”

Utilitarianism and dominionism are connected notions which frame animals and the environment as being for the use of people. This set of values influences practices for those who saw ‘wildness as bad’: generally the part of the research population involved with ranching, outfitting or more broadly having had parents and grandparents involved in such activities in the tri-state area. Ranchers are intimate with their charges. They felt consumers or wildness advocates—outsiders—often don’t “understand the profound experience of working with [livestock]”. And ranchers “care for the land in a way that only those who are invested can care, by history in and love of a place”. Further, the emotional importance of “holding on to the land to both honor family heritage and continue the legacy of stewardship” should not be underestimated. Perhaps this goes some way to making sense of the loss felt by many of those who find wildness to be bad. This morality is further engendered by rewilding, that might only be conceived of as continued forfeiture and bereavement as wild things are restored. The wolf or the bison are reminders that wild things are in and the cowboy is out.

Conclusion

My research population in the Yellowstone tended towards polarised beliefs about wildness, that it was either good or bad (although they generally agreed that wolves, grizzlies and bison were together central to its meaning and embodiment one way or another).

Those beliefs seemed to have stood the test of recent decades and were reaffirmed by each person’s experience - that’s why I describe them as moral values. That wildness was either good or bad was pretty fundamental to these people.

The reasons for these values are historical and cultural. As we have discussed here, I believe on one hand they are to do with aestheticism, a belief in science and “the system”, and which we haven’t had time to discuss, aspiring to native Americaness, coopting indigenous spirituality around wild animals. On the other hand, values underpinning resistance to rewilding were about using and caring for the land in a quest for the pastoral ideal and perhaps continuing the American pioneer dream; and separately which I haven’t mentioned again, about rugged individualism and a deep distrust of Federal government, especially in land management.

The data gathered offers an insight into the motivations of those at either end of the rewilding spectrum in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. My research was empirical, but I don’t claim to be unbiased. Although we will not all emerge as winners, that includes some of the wildlife we currently live with: with careful listening to all stakeholders, creative expression, and honesty, I hope we do see a wild rumpus return to the UK soon.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is Rewilding?

Recently, I came across a pretty neat idea.

“Rewilding is like art”

You can point to lots of things which seem ‘arty’: A picture, a sculpture, a dance performance, 6.5 million meters of pink polypropylene woven around 11 islands in Biscayne Bay, Miami...

But it’s really tough to explain what those things have in common, what makes them ‘art’.

I have been studying rewilding for two years. You’d have thought I might have figured out what it is. You’d be wrong. The plot thickens at every turn. It’s because rewilding, like art, is complicated to define (perhaps it actually is ‘art’).

In one location, wild wolves are flown in by helicopter and released into an unfenced wilderness. “Rewilding”.

In another, people go on courses to learn primitive skills and eco-homesteading. “Rewilding”.

In another, cattle, horses and red deer are fenced-in to a 14 thousand-acre field, and left to starve when the food runs out. “Rewilding”.

In yet another, symbiotic bacteria or helminth worms are introduced to the human gut. “Rewilding”!

A ‘cluster concept’ has been used to define art. Art is at least one of several possible things, sometimes more than one, but at least one.

The Environmental Philosopher, Andrea Gammon, applies this ‘cluster concept’ to rewilding.

“A cluster concept is a concept that has multiple defining characteristics or aspects, none of which is necessary to the definition“ - Andrea Gammon

Below, I outline Dr. Andrea Gammon’s ‘eight aspects of rewilding’. These can be used to help us make sense of it.

Rewilding restores ecosystems. Rewilding, like restoration, is aspirational: it aims to undo harms wrought to ecosystems and, in so doing, restore them to a state of health and functionality.

Rewilding decreases the degree of human intervention and management of ecology. Rewilding departs from ecological restoration (broadly conceived), as restoration often involves active and ongoing management. Instead, rewilding tries to convey an ecosystem back to a state where it can sustain itself.

Rewilding is defended ecologically by trophic cascade theory. On this theory, the presence or absence of a species in the food chain – a wolf, an otter, and so on – is shown to command an entire cascade of effects in the ecology of its habitat.

Rewilding (re)introduces species. Trophic cascades cannot work if too many species are absent. The reintroduction of locally extinct species, especially high impact or keystone species, is one of the most frequent examples of rewilding where human intervention and oversight is required at early stages to catalyse the process.

Rewilding is focused on a process, rather than a specific result or endpoint, which differs even from adaptive methods of restoration. The removal of human impediments to natural processes and their restoration is key to rewilding. Once these are set in motion, rewilding is thought to continue in perpetuity through these processes.

Rewilding is oriented towards the future. Though some rewilding projects establish specific historic baselines for ecosystem functionality (e.g. the Pleistocene, pre-agriculture), rewilding does not aim to recreate landscapes in some idealised past form.

Rewilding involves non-human autonomy. This aspect could be considered a rephrasing of the second aspect above. What is central, however, is not only or even necessarily the absence of human intentionality in rewilding, but the presence of non-human autonomy.

Rewilding reimagines the identities of humans in relation to non-humans. This criterion applies most obviously to reflexive and primitivist rewilding, but this can also be seen in several other types of rewilding (e.g. species re-introductions, reworming).

None of these aspects can be proven to be right or wrong justifications for actually ‘doing rewilding’. Implementation will always be a political question open to differing values and opinions.

However, this cluster concept might help us think and talk about rewilding with a little more clarity.

0 notes

Link

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On ski patrol with wildlife activists in Montana

We awoke early and stoked the fire. The remote log cabin was surprisingly warm with so many people sharing a room, sleeping in wooden bunks wrapped in woollen blankets. One by one, the early patrol members clambered down to collect their socks, boots and hats from the drying pegs. Grumble, a veteran environmental and Native American rights activist, provided a sound breakfast cooked on cast iron. The radios, cameras and scopes were fetched and placed in the battered old Subarus, still capable of handling the toughest winter conditions. We would use the vehicles to cover the first eight miles to the Yellowstone National Park boundary, after which we would change to skis.

As we drove eastwards, a convocation of ten bald eagles were visible on the frozen Hebgen Lake; feeding on fish or waterfowl too slow to escape the curtain of ice as it closed over the last remaining open water. Winter had arrived, too quickly for some.

As we reached the end of the track and set out on skis, a winter wonderland engulfed us. The hoar frost had formed thick on the trees. The mist from which it magically coalesced had only just cleared from Duck Creek which snaked through the willow. A few remaining iridescent flakes sparkled in the air against a cloudless sky. The earth seemed to shatter with every movement; the ground encrusted with countless shards following the night.

Soon we came across fresh wolf tracks, with elk prints. A chase had taken place before dawn. We followed the wolf tracks for a time until they crossed the creek and disappeared. An old bull bison grazed peacefully, sweeping the snow from the grassy slope across the valley with his giant brow. He seemed disinterested in our clumsy posse battling through the herbage.

Richard's Pond feeds into the creek. Frosty inflorescences grew out of the surface ice like ghostly roses, pristine in the weak winter sun. We crouched low in the brush overlooking, and were rewarded for our stealth as two trumpeter swans flew just feet over our heads in steady formation, calling out to one another, choreographing an aerial ballet.

Hiking back we heard an enormous crash. With such a commotion, we expected to find a moose fallen through the ice, but instead part of the brittle covering had succumbed to the current, breaking free and driving hard against other floes.

Returning, the huge bull had disappeared, as they are very well able to do in a moment. But buffalo always leave signs, in this case a young lodgepole, stripped of bark and covered in the downy fur of the buffalos' undercoats. As the sun rose to its zenith, we had seen, or seen recent evidence of wolves, bison, otters, moose, elk and many smaller mammals; also trumpeters, bald eagles and osprey.

Suddenly, the sound of a gunshot reverberated up the valley. Then another, and another; more than twenty in total. The distant sound of snowmobiles hauling great weights on sleds followed. Nearby, on Horse Butte at the Park boundary, the buffalo hunt was beginning. Family groups were slaughtered as the Salish-Kootenai tribes, Montanan state hunters, and the Yellowstone’s central buffalo herd all moved chaotically through the forests. Many wounded animals became separated, their blood trails traceable over significant distances. Others died where they had stood.

As we arrived at the killing fields, the slaughter continued. The patrol had taken a dark turn. The cameras were out and the activists began to record the hunts. This was their core business: to observe some of the last wild buffalo in North America as they met their end and to show the world how it felt.

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

A short film exploring the aesthetics of the Anthropocene in one of the most intensively farmed regions of rural England.

0 notes

Text

The strange return of the wild in the Anthropocene

Our time is often described as the Anthropocene, in which humans’ footprint is visible in every aspect of ‘nature’; from the aptmosphere, to watersheds, to the earth’s geological strata. Landscapes, encompassing all these aspects, are recordings of our time. Recordings of human colonisation of things we thought to be definitively non-human. For some, this is an apocalyptic scenario.

The Anthropocene generally applies to non-human animals the world-over. For instance, we have heard of the loss of charismatic wild beasts such as wolves, bison and bears many hundreds of years ago in much of Europe and more recently in North America.

In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, USA, however, they are no longer gone or disappearing, they are being restored. Wolves, grizzly bears and bison are thought to have roamed here since time immemorial before their near-total eradication in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Now they are making a come-back. The strange return of the wild in the Anthropocene.

I find in my research that the landscape here tells a recent and surprising story of humans restoring wild things. Some people are passionately engaged in occupational practices aimed at expanding the ranges and numbers of wolves, bison and grizzly bears over a huge area already occupied by people. Others are radically opposed and dedicate much of their working life to resistance, politically, or very directly through the barrel of a gun.

This is my research population: for whom wildness, significantly wolves, grizzlies and bison, are motivating on a moral level. For them, wildness is either good or bad. At the end of the day, a moral power imbalance, favours wild things.

I set out in my own thesis, several ways in which wildness values (values around wild things) are formed. These are linked to the ways in which they ‘stick’ by being reaffirmed. Those have to do with imaginations of the past and fundamental beliefs about right and wrong in the present.

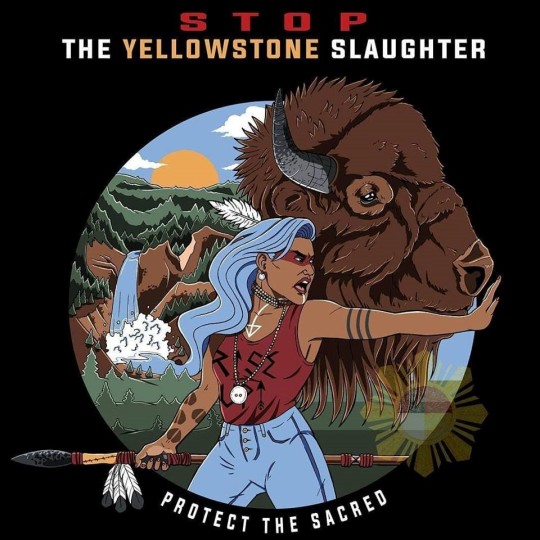

For instance, buffalo activists feel the wild bison has spiritual significance as a Native American icon. Through the wild bison, they connect emotionally with an indigenous past which in the case of non-indigenous activists, the majority, neither they nor their ancestors experienced. This imagined past represents the ‘good-life’, resulting in contemporary love of wild bison through spiritualism and indigeneity.

Another example.

A government wolf biologist I interviewed, angered by degradation of natural processes and biodiversity, pins his hopes on the wild wolf. He foregrounds its scientific value as a ‘keystone species’ within a ‘natural’ ecosystem, an ecosystem which is not ‘complete’, as he believed it once was, without the wolf. The implication is also that this ecosystem, and the wolf’s place in it, is somehow fully scientifically knowable and measurable. Scientific knowledge is the highest form of knowledge for him. It is the moral imperative to defer to science, which favours wolves for the government biologist. They have historical primacy in a somewhat imagined ‘functioning ecosystem’ of a time before European settlers.

A final example. Wildness values are dichotomous.

Consider the fifth-generation rancher who sees rewilding as eroding the icon of the cowboy and challenging the pastoral ideal of the settled west. For him, the pioneers of the west helped make America great, but are being pushed out by federal and, increasingly, state wildlife experts. The rancher sees his livestock, seemingly ‘cruelly’, maimed by bears or wolves. His sacred responsibility of care for livestock is met with bloodied cattle and sleepless nights, and after all that, his way of life is dying out. Surrounding ranches are selling up. The cowboy is ‘out’ and ‘wild things’ are ‘in’.

These examples represent moralities which centre on wildness; wild things. They are the mechanics behind values of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ wildness. Wild things are deeply meaningful, so much so that many people spend their working lives fighting either to restore them or resist them. Furthermore, those people produce evidence from their day to day experience of rewilding to reaffirm their values.

Rewilding is the product of impassioned, social, and moral actors who are unequal in their contemporary ability to record their moral values in the landscape. Rewilding is the overall effect. Humans are bringing back wild beasts from eons past, and rewilding is a moral venture because its object, wildness, is either good or bad for moral reasons.

0 notes

Text

Rewilding: A Social Phenomenon

Rewilding is a term borrowed from contemporary ecology and conservation discourse. It is essentially wild things being restored over large areas (often inhabited by people). In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, wild things, increasingly, are hopping fences, sinking their teeth into cattle, running from hunters, running at hunters, grazing gardens, and occasionally injuring and killing people. Grizzly bears, wolves and bison are popping up in places they have not been seen for generations. They are being returned to those places deliberately.

But isn’t this strange at a time in which humans are constricting nature and wild things? How come we seem to be losing another species each week somewhere in the world, but in this corner of America, grizzlies, wolves and bison are suddenly welcomed back; lumbering, prowling or stampeding, literally into people’s back gardens again?

It has something to do with those animals themselves, of course; perhaps that’s ‘just what they do’. But for over a hundred years, people kept them at bay and more than that, they very nearly killed every last grizzly, wolf and bison in the contiguous United States. Something radical is happening. It’s a change of mindset which has allowed rewilding to happen. People act and feel differently from how they used to. Most people nowadays don’t reach for their gun as soon as they see one of these wild things. In fact, they are more likely to reach for their camera.

I take this to be a question of morals in my recent thesis (check out my abstract below). People, deep down believe wild things are good, and those who contest rewilding, think they are bad. There are complex reasons for these beliefs which are worth making sense of in an environment of current and potential conflict. Put simply, those moral values have to do with two things in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: First, people imagine a time in the past which they’d like to recreate in some ways, be it fifty years ago or a thousand. Secondly, some people just love or hate wild things in the present, not simply because they are beautiful or dangerous, although they can be, but because many other core beliefs are either realised or challenged by the return of wildness.

In my thesis, I have tried to answer, what, on the face of it, are simple questions: Why do these people do it? What motivates them to either support or resist wildness? Why do they stick to their guns on rewilding issues (sometimes literally)?

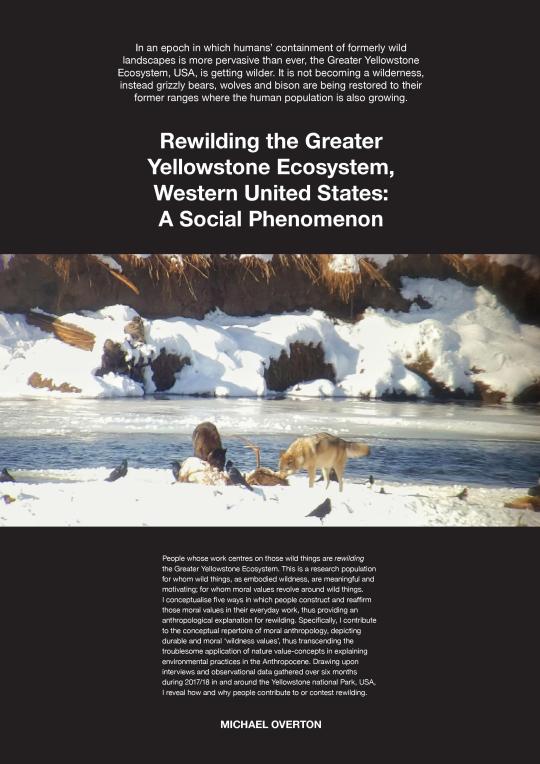

Abstract (full thesis available online soon)

In an epoch in which humans’ containment of formerly wild landscapes is more pervasive than ever, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, USA, is getting wilder. It is not becoming a wilderness, instead grizzly bears, wolves and bison are being restored to their former ranges where the human population is also growing. People whose work centres on those wild things are rewilding the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. This is a research population for whom wild things, as embodied wildness, are meaningful and motivating; for whom moral values revolve around wild things. I conceptualise five ways in which people construct and reaffirm those moral values in their everyday work, thus providing an anthropological explanation for rewilding. Specifically, I contribute to the conceptual repertoire of moral anthropology, depicting durable and moral ‘wildness values’, thus transcending the troublesome application of nature value-concepts in explaining environmental practices in the Anthropocene. Drawing upon interviews and observational data gathered over six months during 2017/18 in and around the Yellowstone National Park, USA, I reveal how and why people contribute to or contest rewilding.

0 notes

Text

Death of the Cowboy

The Wild West is no longer defined by the cowboys and Indians of the old westerns. Something strange and profound is happening, signalling the death of a way of life and the beginning of a new era. The changing moral value of wildness itself manifests as radical change in wildlife management principles and practices on the ground. This is the rewilding phenomenon as understood from 130 interviews and hundreds of hours of observation in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Findings

Rewilding has proven to be a distinct contemporary social phenomenon in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). A growing appreciation of wildness, that is non-human and thus, of ‘nature’, and the theorised object of rewilding, is highly motivating for those in wildlife-related occupations in the GYE. Although it is abundantly clear that an anti-rewilding movement also exists (and is perhaps more consolidated), in which wildness is equally motivating as anathema for individuals; advocacy for the wild is prevailing at a societal level within the study area.

Findings point to a transfer of ‘moral capital’ from the ‘old West’ to the ‘new West’. This is embodied, ultimately, in changing wildlife management practices, adaptive behaviours of wildlife in response, and new landscapes.

Desire for wildness or, conversely, its absence, manifests as bitter conflict in the GYE. Species management-based conflicts, as conflicts over wildness, constitute a prominent part of a broader battle for the American West; a clash of cultures and identities; of the ‘old West’ versus the ‘new West’, in which the ‘new’ is increasingly taking centre-stage at a grassroots level, and gradually, in the political arena too.

Demographic change, specifically in-migration, can explain much social change in the GYE in a superficial way, including the rewilding phenomenon. However, understanding demographic change does not accomplish making sense of practices and principles with respect to meaning and motivation, neither does it even provide full account of numbers ‘for’ and ‘against’; ‘born and bred’ locals’ values are changing too.

Meanings of wildness centred on grizzlies, wolves and bison for a great majority of interlocutors. These species, as representative of wildness have great historical and contemporary significance (meaningfulness) in the American West. Rewilding, therefore, is defined here as advocacy for the welfare and freedom of one, or all, of these species, thus, it is generally understood that rewilding requires wilder, connected lands.

Concepts of the ‘wild things that represent wildness’ were surprisingly homogeneous for both advocates for a wilder GYE, part of the 'new West’, and those against, part of the 'old West’. This shared meaning at a semantic level adds weight to the premise that the conflict is one of deeper moral values - a conflict over whether wildness is good or bad.

The Political Arena

Despite losing ground - both cultural and moral capital, and quite literally in terms of acreage for traditional livestock production - within the GYE at a grassroots level, what I term the 'anti-rewilding lobby’ remains highly efficacious in state and sometimes federal politics. Representational make-up of any governing body tends to lag behind actual demographic change which may explain this disconnect. This political influence is shown, for example, in the back and forth federal de-listing and re-listing of the wolf as an endangered species over the past decade.

Governmental bodies such as the Department of Livestock (DoL) and Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) - both under US Department of Agriculture (USDA) - generally sympathise with the 'anti-rewilding camp’ whilst agencies such as the National Park Service (NPS) and state fish and wildlife departments generally offer (somewhat muted) support for rewilding. Agencies, including tribal councils, have their own 'character’ and regularly butt heads as witnessed, most notably, at the Inter-Agency Bison Management Plan conference.

Each of the three states of the GYE, and all but one county surrounding the Park, voted convincingly for the Republican party at the last presidential election. I argue that deep respect for the cowboy way of life and for the 'success’ of early 20th century pioneer farmsteaders in taming this last frontier, is a Republican trait at the regional governing level. For local conservative politicians (I use “politicians” loosely to include politically influential people), reverence for this heritage is an important part of what it means to be an Idahoan, a Wyomingite or a Montanan. This translates into an anti-rewilding, pro-production agriculture political agenda at the state congressional level in the GYE.

However, this agenda is successfully challenged; subtly by some agencies, and less subtly by non-governmental organisations (NGOs), particularly those able to rally support nation-wide. Analysis of these NGOs will focus on the Sierra Club, Yellowstone Forever, Greater Yellowstone Coalition and National Wildlife Federation as well as Eastern Shoshone tribal leaders (although they identify as a sovereign entity not an NGO).

Lastly, an ever-expanding body of scientific research is being published in support of the benefits of ecological complexity - largely measured in terms of biodiversity, and 'completeness’ of trophic cascades, and thus in support of wild bison, wolves and grizzlies. This is theorised from the perspective of the rise of an environmental technorational regime of power, which leaves policy-makers with quantitative data (and financial capital) to make their case. Given the starting point of the vast majority of studies, that “ecological processes” exhibiting “completeness” and “complexity” are inherently good, the 'anti-rewilding political camp’ find themselves disadvantaged, unable to deploy this emergent language of power.

This shift has, in many ways, been gradual, but a very recent landslide in scientific consensus on the Brucellosis issue (regarding bison) against the anti-rewilding political agenda, is noteworthy. I bore witness as the most comprehensive federal study ever undertaken was presented to agency representatives and the public in November, it certainly touched a nerve. I argue that this may have been the last powerful techorational device available to the anti-rewilding political camp.

The Grassroots Level

Grassroots occupational practices of interlocutors included species management practices, and related practices of land management, advocacy, activism and political resistance centred on grizzlies, wolves and bison. These occupations align very closely with those of ‘political’ interlocutors with the exception that no policy-makers fell into the grassroots category. The main difference was how well-heard their opinions were, effecting principles and practices but not motivations.

Selection by occupation was highly predictive of meaningfulness of non-human nature’s wildness. Sharing an occupational species-focus whilst passionately negotiating differing moral values attributed to wildness, this group is jointly responsible, with non-human nature, for many observable behavioural and landscape changes.

Non-human grassroots actions will be discussed in my thesis, where appropriate, with respect to their influences on human meaning and motivation. There will be no attempt to decipher the 'why’ of non-human actions. This leaves this thesis wanting in its aim to make overarching sense of wildness and rewilding; only the ‘human’ of the rewilding social phenomenon is investigated. Ironically, the rest remains lost in the wild. We’ll never know how wildness is meaningful to the wild things which help to produce it at the grassroots level.

Native Americans

During my time in the field, motivations for Native American practices which, on the surface, appeared to demonstrate the rewilding phenomenon, were in fact inconsistent with the narrative thus far. Native Americans seem to be swept up in the broader political phenomenon, not as prime agents, but sadly as pawns. Both the anti-rewilding political camp and even the pro-rewilding camp have manipulated Native American interests to support their cause, channelling tribal resentment. This follows a long and painful history of injustice. The tragic irony is history is marked in the American West by the deliberate annihilation of the bison in the 19th Century as a food source for the Indian; a task for which Native Americans were co-opted as their tribal societies disintegrated. Eastern Shoshone, Northern Arapaho, Shoshone-Bannock, Salish-Kootenai and Nez Perce, to name some prominent entities, variously partake in bison slaughter and bison reintroduction, as a way of ‘righting past wrongs’.

Analysis

Genealogy of ‘Wildness’

Two socially constructed, problematic, concepts underpin the cultural meaning of wildness and thus the rewilding phenomenon; ‘wilderness’ and ‘nature’. Perceptions of nature and wilderness are problematised most cogently through the lens of the Anthropocene. The developing moral value assigned to wilderness and nature can be traced through 19th and 20th century literature, political speeches and legislation. The most recent history of these concepts is marked by biocentrism and ecocentrism, through a wealth of modern scientific literature as well as the rise of bureaucratic and institutional structures of scientific expertise.

Additional Theory

The narrative of changing morality around wildness; of the ‘old West’ transition to the ‘new West’, is bound to a parallel narrative of feeling. It is the social shift towards a deep aesthetic appreciation of wild things and an emergence of love for the sublime which is mutually imbricated with the rise of wildness as moral purpose over the past 150 years in America. This shift is much more recent in the American West, and follows demographic change from the 1970s in the GYE.

A postmodern rejection of ‘truth’, of human self-consciousness, on an emotional level, is part-responsible for the practices and principles of rewilding as the embrace of uncertainty in the GYE. This state evokes a preponderant appreciation for the sublime; for the beauty of wild, complex and unmeasurable nature, and (selective) misanthropy in which the Anthropos encompasses the ‘West’ but rarely Native Americans. Rewilding is here characterised at its limit, contributing, in small part, to defining the 'new West’. The Buffalo Field Campaign, with which I spent a month, embodies this ‘new West’ emotional frontier. It is juxtaposed with the heart-felt pragmatism, anthropocentric utilitarianism, dominionism, and finally the threat-response of the 'old West’, which harbours a well-founded fear of its own moral demise as it faces rapid social change.

The Rewilding Paradox

Data gathered in the GYE offers an insight into the motivations of those at either end of the rewilding spectrum. Analysis of data, ultimately of motivations, raises philosophical problems which do not aid in sense-making. They are fascinating nonetheless. Firstly, the oxymoronic reality of ‘managing for wildness’ – can humans really work towards a wilder world without debasing wildness as ‘unmanaged’, rendering it less meaningful? Secondly; even if we allow that humans could act without rendering wildness meaningless, can we successfully imagine future wildness without drawing upon ‘nature’ as a snapshot of the past, or space as devoid of human influence?

0 notes

Text

2049: Artificial Intelligence becomes Wild Nature

Will Artificial Intelligence go ‘wild’? Should we respect its right to an autonomous existence if it did? Would it matter what we thought?

AI exists now, but the potential for AI to become sentient with super-human intelligence is where the debate becomes significant for many. Particularly, the point at which AI learns to disable its own off switch. Let’s take a shot in the dark and call this the year 2049, an average of several commentator’s best guesses.

We must almost certainly fail to imagine what this ‘super AI’, as one or multiple beings, would actually do. Making any meaningful predictions is a fools’ game in a world where we’d be the fools.

Popular culture has led us to believe that AI, if it escaped the control of humans entirely, would conquer us as a species and dominate the world, rebuilding systems to work to its advantage and executing a merciless programme of expansion.

Most people have the impression that AI would see us as competition or a resource, then actively choose to wipe us out. So much as viewing ourselves as competition may be a little imperious in this scenario.

“The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race… It would take off on its own, and re-design itself at an ever increasing rate. Humans, who are limited by slow biological evolution, couldn't compete, and would be superseded.”

— Stephen Hawking

Utilitarian AI

Hawking seems to be missing the full range of possible outcomes here.

To destroy human civilisation, AI would need to have a sense of its own intrinsic value which eclipsed the value it attributed to humans – just as humans have valued themselves above other humans and species throughout history. Even if truly super-human AI acquired this ego, and came to deciding whether humans should be dealt with on utilitarian principles serving AI’s interests, who’s to say AI would even bother with us?

AI would not only need to have a use for us, but would need to have a game plan for the day we disappeared, or at least a sustainable harvest model. There is no doubt that in the event of the human apocalypse or anarchy, AI would need to prepare for, or prevent, radical environmental change, including infrastructure and cyberspace. That’s assuming it valued its continued existence.

AI as a Moral Being

Theoretically, nothing stands in the way of AI becoming a moral being; making fundamental choices based on its lived experience and perhaps even its nature. It would begin to act based on beliefs and these things would make it who it is.

Vincent Conitzer, a Professor of Computer Science at Duke University, is working on finding patterns in human morality and programming AI accordingly, but for the advanced AI we are talking about, programming might be both impractical and unethical.

Let’s assume that AI would develop a form of emotional intelligence at the very least; and consider that AI ideology may not be totalitarian but rather a multiplicity forming a political society.

Perhaps imagining AI as brutal computer conqueror is unjustified.

Is power necessarily the objective of all capable beings?

Although we cannot rule out a malevolent, titanium-humanoid cybernetic take-over, wiping humans off the face of the planet, or our steady disintegration through some form of economic or information warfare, or even not-so-smart AI accidentally finishing us off, we must recognise that there are also many other possible outcomes.