Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Red Serpent: 6. A Place called the Holy-water Stoup

Les dalles du pavé mosaïque du lieu sacré pouvaient-être alternativement blanches ou noires, et JESUS, comme ASMODEE observer leurs alignements, ma vue semblait incapable de voir le sommet où demeurait cachée la merveilleuse endormie. N'étant pas HERCULE à la puissance magique, comment déchiffrer les mystérieux symboles gravés par les observateurs du passé. Dans le sanctuaire pourtant le bénitier, fontaine d'amour des croyants redonne mémoire de ces mots: PAR CE SIGNE TU le VAINCRAS.

The slabs of the mosaic paving of the holy place could be alternatively white or black, and JESUS, like ASMODEUS, observes their alignment. It seemed impossible for me to see the summit where the marvellous sleeping one remained hidden. Not being HERCULES with magic power, how does one decipher the mysterious symbols engraved by the overseers of the past? In the sanctuary, however, the holy-water stoup, fountain of love of believers, reminds one of these words: BY THIS SIGN YOU WILL CONQUER him.

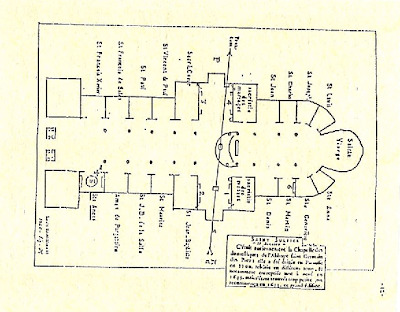

If there is one place without which it would be hopeless to even begin trying to solve the riddle, it is the church of Rennes-le-Château. The poet has fleetingly referred to it a couple of times already, but in this stanza, he makes it very clear that the layout of this church constitutes a key part of the mystery. It would make sense, therefore, to fine-comb everything in this church for clues.

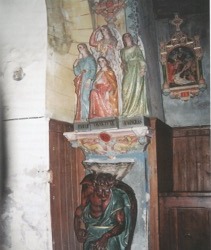

6.1 The church of Rennes-le-Château To get to Rennes-le-Château, one takes the main road from Carcassonne, which eventually crosses the Sals River in the town of Couiza. Just as one is about to exit the town, there is a signpost on the left indicating the road to Rennes-le-Château. From there, the narrow road steadily winds up the hill until one finally drives into this legendary little town. Anybody who is acquainted with the enigma of Rennes-le-Château will understand what a big moment it is to drive into this town for the first time. I can still clearly remember the expectation with which I arrived there. And one is not disappointed. Rennes-le-Château lies right on top of a hill in a picturesque landscape. The old buildings and peaceful atmosphere have an exceptional charm. I have heard many a person express a desire to reside there. The best time to visit this town is over weekends, when all the book- and other shops are open. One should still be able to find copies of the Prieuré de Sion documents that had been deposited in the French National Library, among which Le serpent rouge, at one of these bookshops. Having driven into the town, one continues straight on with the narrow tarred road lined with stone buildings. To one’s right is the castle where the Blancheforts once lived. A short distance further on, just as the church rises right in front, the road curves to the left, with Villa Bethania on the right-hand side. A little further on is the parking area. Here one is greeted by beautiful undulating hills to the south-east, and to one’s right, against the plateau on which the town is built, the Tower of Magdala. Arriving at the Church of Mary Magdalene, one finds a pillar to the left of the footpath similar to the one on which Saunière had engraved ‘Mission 1891’. Just past this pillar is a narrow passage to the left, leading to a shop and the museum, which effects an entrance to Villa Bethania and the Tower of Magdala. To one’s right is the garden in front of the church, as well as the entrance to the cemetery behind it. Above the front door of the church (which is unlocked from time to time), is the following ominous phrase: ‘TERRIBILIS EST LOCUS ISTE’ (‘THIS PLACE IS TERRIBLE’). As one enters the church, one is greeted by a striking devil on the left, who seems to be paralysed from the waist down. The poet calls this character Asmodeus. He has a narrow face and a goatee beard. His eyes look cruel and wild, and his mouth is open. The fingers of his right hand form a conspicuous circle. On his head are two big goat’s horns curling backwards. On the hump behind his head rests the holy-water stoup, which has the shape of a scallop-shell. Above this stoup are two dragonlike figures; possibly salamanders. The one is to the right and the other to the left beneath a red disc with the letters BS written in black on it. These could possibly stand for Bérenger Saunière, or even Boudet and Saunière. Above these letters there is a platform wherein is engraved: ‘PAR CE SIGNE TU LE VAINCRAS’ (‘BY THIS SIGN YOU WILL CONQUER HIM’) — the exact words in the poem. These are the famous words that Constantine had heard in a vision, except that a ‘le’ (‘him’) had been added to the phrase. On the platform are four angels crossing themselves. Right above them is an isosceles cross on a circle with three offshoots at each end. Strangely, all the middle offshoots have been painted light blue, which accentuates the two on either side. That the cross features so prominently makes perfect sense: It is, after all, through this that the devil has to be conquered.

Fig. 16. Asmodeus — the entire artwork

Shifting one’s eyes to the rest of the church, one discovers one is standing to the right at the back of the church. The inside of the church is much smaller than one would imagine. Beneath one’s feet is the black and white chequered floor the poet mentions. Slantwise to the left, in the middle right at the back of the church, is the wooden confessional. Right above it, on the back wall, is a massive fresco depicting the Sermon on the Mount. Straight across from where one is standing, against the opposite wall, is a statue of Jesus being baptised. Jesus is squatting in front of John the Baptist, who is holding a reed cross in one hand and a shell in the other, which is above Jesus’ head. ‘JESUS’ and ‘ASMODEUS’ are therefore facing each other, with the black and white chequered floor between them — precisely as the poet states. There is a reason that these two words are in upper case: They correspond to the white and black theme in the poem, which is symbolic of the antipoles that also feature throughout. This had clearly also been the goal with the depiction of Jesus and Asmodeus in the church, as they are strikingly depicted as antipoles: Jesus is squatting, and Asmodeus is sitting paralysed from the waist down; Jesus’ right knee is touching the pedestal of the statue, and Asmodeus’ left knee; Jesus is dressed in red and the pedestal beneath Him is green, while the devil is wearing green and sitting on a red pedestal. There is a scallop-shell above each of them: the one is in John the Baptist’s hand, the other is the holy-water stoup on the devil’s hump. There is also a cross above each of them: the reed cross in John the Baptist’s hand, and the isosceles cross above the devil, over and above the implied crosses made by the four angels. Looking over the pews from the back of the church, one sees the altar right in front, and the high pulpit just to the left in front of the altar. There are several statues against the walls, including those of St. Anthony the Hermit and St. Germaine that were mentioned earlier; these are to the left. The statue of St. Anthony of Padua is straight across from the pulpit, St. Mary Magdalene straight across from St. Anthony the Hermit, and St. Roch straight across from St. Germaine. Between these statues are the Stations of the Cross, which are to be found in all Catholic churches. To the left behind the altar is a statue of Joseph, and to the right, a statue of the Virgin Mary. Both of them are holding the Child.

6.2 The landmarks at Rennes-les-Bains The fact that the poet highlights Jesus and Asmodeus leads one to surmise that these statues are also related to the area around Rennes-les-Bains. Upon an investigation, one indeed finds a place in the Rennes-les-Bains region that is associated with the devil, namely the Devil’s Armchair. It lies against the hill not too far south-west of Le Cercle. This ‘armchair’ is a light-coloured, detached rock in which a seat had been carved. It actually provides a surprisingly comfortable seat. It is said that this rock had at some stage belonged to the Hautpouls. While the lame devil in the church of Rennes-le-Château is without a chair, one here finds a chair, but the devil is missing. It is evident that these two have to be connected somehow.

Fig. 17. The layout of the church of Rennes-le-Château

Right next to the Devil’s Armchair, a fountain called the Fountain of the Circle rises. This water is also rich in iron, giving it a rusty colour. The water is piped down from up here to the main road at the bottom, where it runs out and eventually flows into the Sals. It could very well be that the circle the devil’s fingers is forming is connected with this Fountain of the Circle. As Gérard de Sède points out in Le trésor maudit de Rennes-le-Château, there are also other landmarks in the region that are associated with the devil, among which the five cup-shaped hollowed out marks in the so-called Bread Stone further to the south-east. The devil is said to have made these with his fingers when he touched it. The plateau behind the Devil’s Armchair, the Le Pla de la Coste, is also reminiscent of the flat side of the devil’s right leg. A third landmark that is associated with the evil one is an old signal tower close by, which at some stage had allegedly been called the Devil’s Nipple.

6.3 Cap de l’Homme Just as the Devil’s Armchair relates to the devil in the church of Rennes-le-Château, so another landmark in the area relates to Jesus! According to Boudet, there had been a sculptured head in a rock above the plateau to the west of Rennes-les-Bains that had been associated with Christ. It was called the Cap de l’Homme (���Head of the Man’). Boudet writes: ‘Cap de l’'Homme. A menhir was conserved in this place, and one have there, high up, sculptured in relief, a magnificent head of the lord Jesus, the saviour of mankind.’[44] In 1884, Boudet himself removed this carving. A depiction of this head — also called the Head of Dagobert II —- apparently appears in the document Pierres gravées du Languedoc, in which depictions of Marie de Blanchefort’s tombstones are also to be found. To reach the rocks where this head had been, one follows the main road going through Rennes-les-Bains further south, past the convergence of the Sals and Blanque Rivers, up to the first narrow tarred road branching off to the right. This road runs up the plateau and leads to the area where the Cap de l’Homme had once been. On this narrow road, just past an open piece of grassland on the left, there is a signpost on the right-hand side indicating the way to Roc d’en Barou — the high point of the plateau directly to the west of Rennes-les-Bains. (One cannot, however, always count on these signs. I have more than once found some of them to have disappeared without a trace.) There is space to park one’s vehicle close by. At this sign, a very inconspicuous two-track dirt road branches off to the right. One follows this, taking the right-hand path that has fallen in disuse where the road forks. About 200 m further on there are a couple of rocks to one’s left. The rock in which the Cap de l’'Homme had been engraved, is nearby — about 30 m from the path. Old Christian crosses are still to be seen on the front and back of this rock. The poet emphasises the fact that Jesus and Asmodeus are eerie the ‘alignment’ of the ‘paving’. These two landmarks in the Rennes-les-Bains area, namely the Devil’s Armchair and the Cap de ‘Homme, correspond exactly to that. Instead of the white and black block-floor in the church, one here finds certain important lines of longitude and latitude, which could also be linked to white and black patterns. The Devil’s Armchair faces east, in the direction of the Sals River lower down the slope. If one were to move the devil in the church here, he would be looking slightly to the left, almost straight in the direction of the Cap de l’Homme — exactly like in the church!

6.4 The Holy-water Stoup The reason the poet draws attention to the church of Rennes-le-Château at this point is that it relates to the next landmark on the route. The Devil’s Armchair is just a few minutes’ walk from the stone circle on the outskirts of Rennes-les-Bains in a south-westerly direction through the beautiful natural forest. It is possibly from here that the poet cannot see the place where the sleeping beauty lay, or lies: ‘It seemed impossible for me to see the summit where the marvellous sleeping one remained hidden.’ This place, which is the end of the route through the area, must therefore be somewhere on a hill. The next landmark could be connected with the holy-water stoup in the church, as the poet refers to it further on in this stanza: ‘In the sanctuary, however, [is] the holy-water stoup, fountain of love of believers ...’ Astonishingly, one discovers that, just like Jesus and Asmodeus are connected with landmarks in the Rennes-les-Bains area, so, indeed, is the holy-water stoup. Just further south, where the Sals and Blanque Rivers converge, one finds a beautiful blue pool of water, which is also called the Holy-water Stoup! In order to get to the Holy-water Stoup from the Devil’s Armchair, one continues along the footpath and then takes the path branching off to the left to Le Roche Tremblante — the so-called Trembling Rock. Beneath this rock is another footpath leading back in the direction of Rennes-les-Bains. The path one is following, leads down to the tarred road next to the Sals River, about 100 m north of the Holy-water Stoup. On thinking back to the holy-water stoup in the church, it strikes one that the letters BS on the red disc above it could also allude to the Blanque and Sals Rivers. It could therefore be that the two dragonlike figures to the left and right underneath the BS are symbolic of these two rivers. The connection between the two rivers and the dragonlike figures is even stronger if one supposes that the figures do not represent two salamanders, but a basilisk and a salamander (which are depicted as identical, simply because they are utilised as twin figures). In that case, the letters BS could be connected with the rivers as well as these figures.

Fig. 18. Snakelike figure at the Fountain of Lovers

The basilisk and salamander are mythological antipoles: The salamander was symbolic of the righteous who could resist the fervent temptations of the devil, as it was apparently fire-resistant and could even put out fire. The basilisk, on the other hand, symbolised the devil and was regarded as the head of the serpents. It was also depicted as a beast that was half serpent, half cockerel. In accordance with the fact that these beasts represent antipoles, they are depicted on either side of the holy-water stoup in the church. In the Rennes-les-Bains area, the Blanque and Sals Rivers symbolise these antipoles, with the Holy-water Stoup, through which the Rose Line runs so neatly, as the central point in between.

6.5 The Fountain of Lovers In the description of the Holy-water Stoup the poet mentions the ‘fountain of love of believers’. These words are reminiscent of another landmark in the area, just further up the Sals River. Turning left on the tarred road at the Holy-water Stoup and driving along the Sals, the road lazily bends from east to south. Just a short distance ahead is a place in the Sals called Fontaine des Amours — ‘Fountain of Lovers’. This must surely be the place with the most beautiful scenery in the region. From the parking space, one takes the footpath just on the other side of the bridge down to the river at the bottom, where a breathtaking scene awaits one. Under the vivid green trees, the water of the Sals bubbles over the rocks and into a magnificent pool. Close by is another pool where the rock has been chiselled into the shape of a heart. On top of the rocks across from the pool, the ruins of an old building are etched against the trees. At this fountain there is a surprise in store. A snakelike figure has been carved in the rock that inadvertently calls to mind the salamander — which is indeed connected with the Sals. The salamander is quite an appropriate figure here at the Fountain of Lovers, as it could serve as a reminder to resist the fervent arrows of the evil one. It seems that Saunière also had to deal with such temptations here. In Henry Lincoln’s Key to the Sacred Pattern there is a photograph of an engraving that apparently related to him. The engraving consisted of the name ‘E. CALVE’ and an arrowed heart, as well as the date 1891. According to some versions of the story, Saunière had gone to Paris that year, where he met Emma Calvé, the famous French opera singer. Unfortunately, the engraving has since been destroyed. The fact that the salamander can be connected with this fountain leads one to speculate that there is a fountain in the upper courses of the Blanque River that could be associated with the basilisk.

6.6 The statues and Stations of the Cross It is fascinating to compare the route from the heart of the Rose Line with the Stations of the Cross and the statues in the Rennes-le-Château church. After the statue of St. Germaine — who is connected with the heart of the Rose Line in the cemetery — and the fifth Station of the Cross next to it, one finds the statue of Jesus and John the Baptist, which relates to the Cap de l’Homme. From the cemetery in Rennes-les-Bains, this landmark lies straight across on the plateau to the west of the church. It is admittedly not on the route, but indeed next to it, walking from north to south. It was undoubtedly a prominent landmark in the time of Boudet; anyone following this route would most certainly have at least been aware of it. This, of course, implies that some of the landmarks may lie somewhat away from the route. The next Station of the Cross in the Rennes-le-Château church clearly also bears reference to the Cap de l’'Homme. It is a depiction of St. Veronica gently wiping Jesus’ face, which, according to tradition, left an imprint of Jesus’ face on the cloth. This emphasis on the face of Jesus links it to the Cap de l’Homme. In the background in this Station, there is a soldier with his bended right hand on a white shield above him, which may very well indicate that this landmark is to the right- hand side above the route. Right next to this Station, just before the confessional, one finds the seventh Station of the Cross. This Station includes a curious depiction of a man on the left with his arm bent in an S-shape. This could allude to the Sals River, which does indeed flow past the cemetery in Rennes-les-Bains. From there, the route also leads further along the Sals, which runs to the east. To the west, on top of the plateau, is the Cap de l’Homme. The confessional, again, could be representative of the church of Rennes-les-Bains, which lies exactly there next to the Sals. After the confessional there are two more Stations of the Cross before one again comes to the devil with the holy-water stoup on his hump. Although the devil as well as the water stoup pertain to two landmarks just a short distance further on the route, they form part of a single work of art, so it is unclear to which landmark one has to link that particular point in the Way of the Cross. Earlier on, Jesus and John the Baptist were depicted together, but only Jesus could be linked to a landmark at that specific point on the route. It could be that the devil and the water stoup only serve as background for another landmark at this point on the route, namely a cross. In that case, the Devil’s Armchair as well as the Holy-water Stoup would be connected with this cross, or maybe the shape of a cross in the area. The fact that the cross is the main motif in the artwork, and highlighted by the words, ‘BY THIS SIGN YOU WILL CONQUER him’ (a reference to Constantine’s cross) confirm this assumption. The fact that there are remarkable similarities between the statues and the Stations of the Cross in the Rennes-le-Château church and the route through the Rennes-les-Bains area, leads one to the significant discovery that the riddle in Le serpent rouge is the exact same riddle Saunière and Boudet had hidden in the layout and ornamentation of the Rennes-le-Château church. All that the poet does is to formulate it in a new way. That is why he encourages one to investigate the clues Saunière and Boudet provided. It’s no wonder he says one has to ‘decipher’ these mysterious symbols created by ‘the overseers of the past’ to reach the ‘solution’. One is therefore not only busy solving the riddle, but also the mystery of the two Rennes’s! In view of the fact that the poet is merely reformulating an existing riddle, it stands to reason that he had access to these priests’ secrets. The information contained in the poem is way too detailed, for him and therefore also Pierre Plantard, not to have been involved in the whole enigma.

6.7 Hercules’ magic power In this stanza, the poet also refers to a Greek mythological figure that outwardly has absolutely nothing to do with the region, namely Hercules. In this regard, he links up with Boudet, who also mentions Hercules: ‘There is no doubt that Hercules existed only in Greek and Latin myth; however, it is useful to note, this famous hero [according to Pyrenean’ tales] takes a real consistence and reclothes the character with truth, as soon as he personifies the celtic nation and the migration of this people towards the western lands of Europe.”[45] One wonders whether Pierre Plantard’s other name, Pierre de France, had not also been an allusion to the fact that he, as their supposed rightful king, personified the French people. The poet’s reference to Hercules’ ‘magic power’ implies that the 12 magic tasks he performed are under discussion. These 12 tasks are widely associated with the star signs of the zodiac, implying Hercules also symbolises the sun in its orbit through the zodiac. The poet is therefore not only referring to the signs of the zodiac, but also to Hercules as a symbol of the sun. As was mentioned right at the beginning, the 13 stanzas of the poem Le serpent rouge fall under the signs of the zodiac, with the Serpent-handler as the 13th sign. There are also five stanzas before this one in which Hercules is mentioned, and seven thereafter, which could be representative of the five winter and seven summer months. Bearing all of this in mind, it may very well be that the geometrical pattern to be uncovered in the Rennes-les-Bains region is also somehow related to the sun. Interestingly, in ancient times, the colours white and black were associated with sunrise and sunset. Hercules, as the sun, is therefore also the one standing in the middle of the antipoles white and black. This could be the reason his name too, like that of Jesus and Asmodeus, is written in upper case. Counting the words in this stanza, one discovers that ‘Hercules’ appears right in the middle: there are 36 words before and 36 after it! It may, however, also be that he in actual fact represents the sun child in the arms of the mother, typically depicted with twin figures on either side of her.

44. Boudet, H. 1886. La vraie langue celtique ... Carcassonne. Reissue: 1984. Belisane: Nice, p. 234. 45. Ibid., p. 214.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Red Serpent: 5. Reaching the Meridian Line

Rassembler les pierres éparses, oeuvrer de l'équerre et du compas pour les remettre en order régulier, chercher la ligne du méridien en allant de l'Orient à l'Occident, puis regardant du Midi au Nord, enfin en tous sens pour obtenir la solution cherchée, faisant station devant les quatorze pierres marquées d'une croix. Le cercle étant l'anneau et couronne, et lui le diadème de cette REINE du Castel.

To assemble the dispersed stones, work with square and compasses to put them back together again in regular order. Seek the meridian line going from the East to the West, then look from the South to the North, finally in all directions, to obtain the searched-for solution, positioning oneself in front of the fourteen stones marked with a cross. The circle being the ring and crown, it is the diadem of this QUEEN of Le Castel.

The poet is clearly done with pleasantries, like introducing friends and relating long walks. In this stanza, he seriously calls one’s attention to the bigger picture. The fact that one should evidently start looking all over the place for clues, leads one to suspect that the landmarks will eventually reveal some kind of geometrical pattern too — the meaning of which, like those in the texts, is still a mystery in itself.

5.1 With square and compasses

One is now instructed to assemble the ‘sixty-four dispersed stones of the perfect cube’ and put them back together again. Exactly what ‘in regular order’ means is at this stage anyone’s guess. The relevant landmarks in the area, which seem to have been scattered randomly, therefore actually form part of a well-ordered whole — the bigger picture.

To reduce the seeming chaos to order, one is told to use two instruments, namely a square and a pair of compasses. These are the two most basic measuring instruments, which still today figure prominently in Masonic lodges. This is quite logical, as the latter had developed from earlier builders’ orders in which these instruments were paramount. A square is used to draw straight lines and rectangles, and compasses, obviously, to draw circles. These are once again antipoles, with which the poem is interspersed.

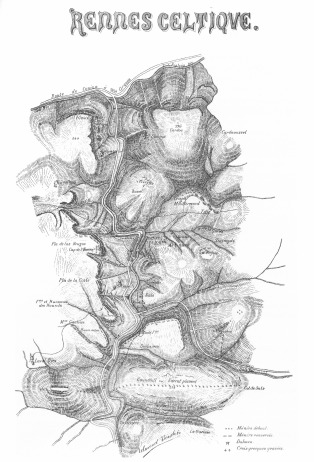

A square and compasses are mainly used to draw sketches and diagrams on paper, and in this case, the ‘paper’ is undoubtedly a map of the area. Although the map at the back of Boudet’s book (see Figure 14) only includes the region from the entrance to the Sals Valley south of the town of Serres to the Serrat Plateau south of Rennes-les-Bains, and is also not drawn exactly to scale, it shows certain landmarks that are not indicated on modern maps and that could be significant. For this reason, Boudet’s map should be used as a basic map of the area.

The poet mentions two more landmarks on the route, namely those one apparently has to regard as starting-points in order to uncover the geometrical pattern(s) in the area. The first is a spot where a certain line of longitude and a certain line of latitude cross, and the other a place that seems to be the centre of a circle. Next, one is supposed to ‘look ... in all directions’, which implies that from there, one can systematically start working towards ‘the searched-for solution’.

5.2 The St. Sulpice meridian

The obvious question now is: Exactly which of the multitude of meridians and lines of latitude crossing each other on the map is the poet alluding to?

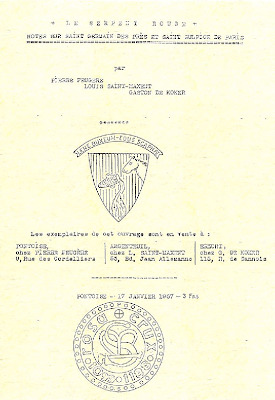

The only meridian singled out in the document Le serpent rouge is the one indicated by the copper strip on the floor of the St. Sulpice Church in Paris. As was mentioned earlier, the floor plan of this church included in the document clearly shows this meridian, with the letters P and S and the words ‘PRAE-CUM’ next to it. This meridian runs 2°20’05.6”E of the prime meridian at Greenwich. It lies very close to the Parisian meridian — 11.4”W of it — which dates from before when the Greenwich meridian started being used as the international line of reference for coordinate systems.

On Boudet’s map, this specific line of longitude runs close to the eastern border of the area, in other words, east of the immediate area in the Sals Valley where one finds oneself at this point.

The question arising, though, is whether somebody alluding to a meridian that in all probability relates to the hiding place of a treasure, would make it this easy to pinpoint. One tends to believe that the St. Sulpice meridian would rather lead one to the exact meridian — and region — the poet has in mind.

Fig. 14. The map of Edmond Boudet

5.3 The Rose Line

In the document Au pays de la reine blanche, a meridian that might be the line one is looking for is mentioned.

Just to put this document in perspective: It was published under the pseudonym Nicolas Beaucéan, which Franck Marie in Rennes-le-Château, étude critique [40] (‘Rennes-le-Chateau, A Critical Study’) deems to be one of Pierre Plantard’s pseudonyms. The name Beaucéan refers to the Knights Templar’s flag. (The Knights Templar was a Medieval Christian military order that existed from shortly after the first crusade until 1307.) This flag comprised parallel white and black blocks — once again echoeing the white and black theme in the poem. In the documents in the French National Library, the Order of the Knights Templar is also associated with the forerunner of the Prieuré de Sion, the Order of Sion.

As for the meridian: The one referred to in the above-mentioned document is called the ‘Rose Line’, in other words, the ‘red line’, which immediately calls to mind the ‘red serpent’. According to the author of this document, the abbé Courtauly had the following to say about the Rose Line: ‘If the parishes of Peyrolles and Serres are the twin children of Saint Vincent, the parish of Rennes-les-Bains protects the heart of the Roseline.’ The Rose Line therefore runs past (or through) the church of Rennes-les-Bains. The fact that this particular line falls almost exactly in the centre of Boudet’s map, leads one to believe that this could be the line the poet has in mind.

The towns of Peyrolles and Serres mentioned in the quotation, lie to the north of Rennes-les-Bains. One can easily spot these from the lookout point on the hiking path between Roque Nègre and Blanchefort. The writer connects them with the ‘twin children’ of St. Vincent — a saint one has already come across: It is said that he is mentioned in one of the parchments allegedly discovered in Rennes-le-Château.

St. Vincent was a friend of Jean-Jacques Olier, the founder of the St. Sulpice Church, wherein a meridian is indicated across the floor. Just like Olier, St. Vincent is also associated with the leadership of the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement, which apparently was a front (or another name) for the Prieuré de Sion.

In the above quotation, the churches of Peyrolles and Serres are linked to the Rose Line. A quick glance at the map reveals that they fall on lines of longitude on either side of the Rennes-les-Bains church. Upon closer examination, however, one discovers that these churches lie perfectly symmetrical on either side of the meridian running through the cemetery behind the Rennes-les-Bains church.[41] As the Rose Line dates from the time when these churches were built, one could allow for a minor error of a few metres. The directions in Au pays de la reine blanche therefore correspond exactly to what one finds in reality: The church of Rennes-les-Bains indeed ‘protects’ this line.

On the map, this meridian runs past Lampos in the north — the white rock formations on the slopes of Cardou. Lampos lies straight across from Blanchefort on the other side of the ravine when entering the Sals Valley from the north. South from there, the meridian runs through the Rennes-les-Bains cemetery, further south through the spot where the Sals and Blanque Rivers converge, and still further south, past a fountain called Fontaine de Madeleine (‘Fountain of the Magdalene’.

The fact that this meridian runs through the convergence of the mentioned rivers unveils a beautiful symmetry in the area. This, once again, corresponds to the balancing of the poles in the riddle, which is crucial to finding one’s way.

5.4 Lampos

According to Boudet, the name Lampos comes from the word ‘lamb’. He writes: ‘This last rock separated from Cardou and presenting several points reunited at the base, gave our ancestors the idea of small beings comprising a family ... [They] poetically named these needles Lampos. This word derives from ‘lamb’ or ‘to lamb’, when speaking of the sheep.’ [42] This rock structure does indeed look like white lambs grazing on the slopes. The poet later also connects it with the baptism of Christ, and therefore John’s words: ‘Behold the Lamb of God.’

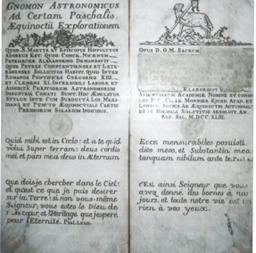

When looking at the copper strip indicating a meridian in the St. Sulpice Church, one makes the astounding discovery that it is indeed linked to the ‘Lamb of God’. At the one end, the line runs to the gnomon in the northern wing of the church, on which it is vertically produced. Right next to the line on the gnomon there is an inscription — as well as the symbol of the Lamb of God! This inscription also appears in the document Le serpent rouge. Just as the Rose Line runs through Lampos, so the meridian line in St. Sulpice is (literally) connected with the Lamb of God. It is therefore highly likely that this symbol on the gnomon serves as an indication of where the relevant meridian lies — the one that runs through Lampos at Rennes-les-Bains!

This discovery is the first indication that the riddle in the poem and the information in the related documents possibly not only pertain to the convictions of Pierre Plantard and his circle of friends, but could also be based on a geometrical pattern in the Rennes-les-Bains region that had existed long before any of them did! Although it is certainly possible that Pierre Plantard linked the symbol of the Lamb of God on the gnomon to Lampos, the fact that both had existed long before his time implies that others before him had the exact same association in mind. It is therefore not coincidental that the meridian running through Lampos also falls in the middle of Boudet’s map, and that all the landmarks on this map can easily be ordered in respect of this meridian. This proves that Pierre Plantard did indeed have access to certain secrets that at least date from the time of the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement.

Fig. 15. The inscription on the gnomon

5.5 The Rennes-les-Bains cemetery

To reach the cemetery behind the church of Rennes-les-Bains, one takes the footpath from Blanchefort, and at the fork, the path going down to the tarred road. At the second little bridge, there are steps leading down to the water from the Pontet Fountain that flows from a pipe underneath the bridge. This water is rich in iron and leaves a reddish deposit on the ground. From here, one follows the road into Rennes-les-Bains.

It is quite a rare experience relaxing with a cold drink outside the café fronting the town square, which is shaded by the majestic plane-trees in the centre. The opposite right-hand corner of the square conceals the entrance to the passage-way that leads to the church.

When entering the vestibule, which is separated from the church itself by a door, the first thing that catches the eye is an iron cross decorated with roses, with a Virgin and Child in the centre. Underneath this cross one finds three inscriptions: ‘IN HOC SIGNO VINCES’ (‘BY THIS SIGN YOU WILL CONQUER’), ‘DOMINO VIE RECTORE’ (‘TO THE MASTER WHO SHOWS THE WAY’) and ‘PETRUS DELMAS FECIT’ (‘MADE BY PETRUS DELMAS’), with the date 1856 underneath. One immediately wonders if the abbé Vie, whose name features in the middle inscription, is the one who is supposed to show the way.

As for the third inscription: In 1856, Petrus Delmas apparently published a writing entitled L’Armorial du Languedoc-Roussillon (The armorial bearings of the Languedoc-Roussillon’) in which one or more of the antique Plantard family coats of arms appeared. The existence of such a book can, however, not be verified.

Walking straight through the vestibule, one reaches the cemetery behind the church. Here one finds the grave of the abbé Jean Vie, who died in 1872 at the age of 64. According to his epitaph, he became a priest at 32, which neatly divides his life into two parts of 32 years each, 32 ‘black’ and 32 ‘white’ years — corresponding to the Knights Templar’s flag, as well as the blocks on a chess-board.

The date on his grave, namely the 1st September, is written as ‘1 er 7 embre’, and therefore also implies 17 (in French, 7 is ‘sept’). Together with the French pronunciation of his name, ‘Janvier’ (meaning ‘January’), one therefore has an allusion to the 17th January — the same day Sigebert is said to have been brought to Rhedae. This is also the holy day of the archbishop of St. Sulpice, the patron saint of the church in Paris that had been named after him, who died on the 17th January, 647. Given the connection between this date and St. Sulpice, it is highly likely that this grave relates to the meridian indicated on the floor of the St. Sulpice Church.

Next to the grave of the abbé Vie is that of Boudet’s mother and sister. The white tombstone is bestrewn with black crystals - again the white-black theme. Between their epitaphs is a vertical line with arrowheads at the top and bottom, and one’s first thought is whether this is not perhaps indicative of the Rose Line.

As the Rose Line indeed runs past these graves,[43] there is little doubt that they are connected with it. This would imply that the cemetery not only boasts an important meridian, but also that the priests of the church had been aware of it and left all sorts of clues about it. Another grave to be found here — which later on proves to be of great significance — is that of Paul-Urbain de Fleury, the son of Paul F. Vincent de Fleury and Gabrielle, Marie de Blanchefort’s daughter.

According to Au pays de la reine blanche, the church of Rennes-les-Bains protects the ‘heart’ of the Rose Line. This ‘heart’ in all probability alludes to a point where the Rose Line and a line of latitude cross, which would imply this line of latitude is the other line the poet is referring to. The next landmark implicitly mentioned in the poem is therefore to be found here in the Rennes-les-Bains cemetery.

5.6 Mirror images

One now expects the poet to enter the church of Rennes-les-Bains. He does, after all, mention the 14 ‘stones’ marked with a cross, which undoubtedly refers to the 14 Stations of the Cross. The Stations in the Rennes-les-Bains church, however, do not include any of the peculiarities found in the Rennes-le-Chateau church, which means it is rather the latter that is relevant at this point. One therefore has to position oneself in front of the Stations of the Cross in the church of Rennes-le-Château — which forms part of the ‘all directions’ one is told to look in.

The poet switches very cleverly between the two churches of these towns. Just as one thinks one is supposed to enter the church of Rennes-les-Bains, he actually has the one in Rennes-le-Château in mind. He clearly had no intention whatsoever of making this a walk in the park.

Just as the poet metaphorically refers to the landmarks on the route as stones, so he also calls the Stations of the Cross in the church of Rennes-le-Chateau ‘stones’. There is therefore a parallel to be drawn between the route in the Rennes-les-Bains area and the Stations of the Cross in the Rennes-le-Château church. This emphasises precisely what one discovered earlier, namely that he calls the route a pilgrimage as an allusion to the Way of the Cross as depicted in the Rennes-le-Château church. The route outside the church of Rennes-les-Bains therefore corresponds to the Way of the Cross inside the church of Rennes-le-Château. These two are therefore mirror images, as it were.

One now starts noticing exactly to what extent the poet’s description of the route tallies with the inside of the Rennes-le-Chateau church. As was mentioned earlier, the description of the poet’s friend standing on Blanchefort corresponds in detail to the first Station of the Cross in this church. The high pulpit directly to the right of the first Station could certainly also be indicative of this look-out on top of Blanchefort.

In the description of the route past Roque Nègre he mentions having to chop down vegetation. This tallies with the depiction in the second Station of a boy dressed in brown, gathering pieces of wood. In the following stanza, wherein a flight is mentioned, the Pontet Fountain is the next landmark, as it is the only place in the region that can be directly linked to Sigebert.

Just after the second Station of the Cross is a statue of St. Anthony the Hermit, who, just like the boy in the second Station, is dressed in brown. The question is whether one can link St. Anthony to the Pontet Fountain — or maybe rather to Sigebert.

Astonishingly, there are indeed two things pertaining to St. Anthony that relate to Sigebert. The first is that the holy day of St. Anthony falls on the 17th January — the day (in 681) Sigebert had allegedly been brought to Rhedae. The second is that, while St. Anthony is regarded as the prince of all hermits, Sigebert (as well as his next two descendants, Sigebert V and Bera III) was also referred to as the ‘hermit prince’ as a result of his living in a cave on a hill close to Rhedae. It would therefore seem that the ornamentation between the Stations of the Cross in the church of Rennes-le-Chateau also relate to the route!

In the fifth stanza, one discovers the next landmark on the route to be the heart of the Rose Line in the cemetery behind the church of Rennes-les-Bains. The rose-decorated iron cross in the vestibule of this church could also allude to this heart. In addition, the fourth Station of the Cross is dominated by rose colours: Mary Magdalene is dressed in apricot-coloured clothes with shades of pink in the creases, and Jesus’ mother is wearing a light rosy pink dress.

Next to the fourth Station is a statue of St. Germaine of Pibrac, holding a bunch of roses in her dress. She was a shepherdess of the Languedoc who was raised to sainthood in 1867. Her story corresponds greatly to (and is probably just another version of) that of St. Roseline, whose holy day is also on the 17th January. St. Germaine’s day of remembrance, the 16th June, is also the day on which the French nun Marguerite Marie Alacoque had the vision that led to her worship of the ‘Sacred Heart’. This, too, could be related to the heart of the Rose Line.

Roses, St. Roseline and the Sacred Heart, all related to the Rose Line, can therefore be linked to St. Germaine. The similarities between the landmarks on the route and the ornamentation in the church of Rennes-le-Chateau are therefore unmistakable. This means one can again and again search the Stations of the Cross and the ornamentation for clues — precisely as the poet suggests.

5.7 The circle

After being led to the heart of the Rose Line in the Rennes-les-Bains cemetery, one is now lured to the ‘circle’. This reference is not merely to this shape — it has a bearing on another spot just a short distance from the cemetery, on the outskirts of Rennes-les-Bains, called Le Cercle (‘The Circle’). In view of the fact that compasses are mentioned, it would seem that this place is to be used as the centre of the circle one has to draw. Boudet alleges that this very spot is the centre of the stone circle that is to be found in the area.

To get to Le Cercle, one walks in a southerly direction from the church of Rennes-les-Bains down the main road. Right on the outskirts, a narrow road branches off slantwise to the right. Following this, one turns left just before the last stone building on the left-hand side.

Entering the house’s yard, one immediately sees Le Cercle — an ancient stone circle of about 7 m in diameter. The house to the left was built on top of some of these stones, which are visible at the bottom of the wall to the left of the front door. Some of the other stones are only just visible above the surface.

The poet compares this stone circle to a ring and a crown. This brings to mind the ring of Solomon, which is also associated with a treasure. The crown does, after all, have a royal connotation. According to legend, Solomon appointed the devil Asmodeus as keeper of the cave in which his treasure was hidden. One day, the king lost his seal ring, upon which the devil refused him entrance to the cave. It was only after Solomon had found the ring again that he could drive the devil away.

In accordance with this tale, the devil does indeed also figure in our story — and he has an armchair just a short distance from Le Cercle!

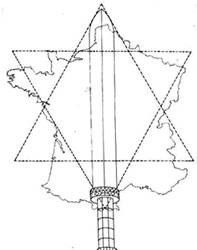

Figuring out how the stone circle could be symbolic of Solomon’s seal ring is the easy part. The ‘seal’ of Solomon, which is also the symbol of the poet’s friend, does, after all, have a circle as base, with all the points of the hexagram on it. One therefore has a circle here that could easily be drawn on a map, with Le Cercle as the centre thereof. This corresponds to the poet’s advice about using a pair of compasses.

What strikes one is that the two geometrical patterns that are implied in this stanza, namely two lines crossing, and a circle, correspond to the two geometrical patterns on the coded texts, namely lines that cross each other, and a hexagram. This could certainly imply that the geometrical patterns on the texts are related to the last two landmarks in the area, namely the heart of the Rose Line and Le Cercle. The latter should, by the looks of it, serve as the base for drawing the seal of Solomon (a hexagram).

Besides the ring and crown, the poet also mentions the diadem of the queen of ‘Le Castel’. The ring, crown, diadem and queen are all indicative of royalty.

This is not the first time one hears about a queen. The poet already in the third stanza refers to the ‘BEAUTY’ and ‘QUEEN’, both in upper case. In the fourth stanza, he follows it up with another reference to the ‘BEAUTY’, and here, in the fifth, with another to the ‘QUEEN’. As in the rest of the poem, everything is in perfect dualistic harmony.

The queen is of ‘Le Castel’, which either refers to a place called Le Castel, or alludes to a castle. It also calls to mind the area where our queen Blanche came from, namely Castille — a name that also has a bearing on a castle. It is furthermore reminiscent of the castle where the ‘sleeping BEAUTY’ lies.

The ‘QUEEN’ and the ‘BEAUTY’ most likely refer to different aspects of the same female figure, and ‘Le Castel’ is where one is headed. It would seem, then, that the poet is drawing more attention to the fact that the ‘solution’ of the bigger picture will only be clear once one has reached this ‘castle’.

Hope maketh not ashamed.

40. Marie, F. 1978. Bagneux: S.R.E.S.

41. The western walls of these churches provide the best reference lines.

42. Boudet, H. 1886. La vraie langue celtique ... Carcassonne. Reissue: 1984. Belisane: Nice, p. 231.

43. The grave of Jean Vie lies on 2°19'11.7"E, which I took as the Rose Line.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Red Serpent: 4. With Measured Steps

Grâce à lui, désormais à pas mesurés et d'un oeil sur, je puis découvrir les soixante-quatre pierres dispersées du cube parfait que les Frères de la BELLE du bois noir échappant à la poursuite des usurpateurs, avaient semées en route quant ils s'enfuirent du Fort blanc.

Thanks to him, from now on with measured steps and a sure eye, I am able to discover the sixty-four dispersed stones of the perfect cube that the Brothers of the BEAUTY of the black wood, escaping the pursuit of usurpers, scattered along the way while they were fleeing from the white Fort.

As in the previous stanza, the poet still draws much attention to the route he is following. From this stanza it appears that he has made good progress, as he has all of a sudden gone from desperately having to chop down vegetation to striding along with measured steps and a sure eye. The reason for this seems to be that he has begun to discover clues. The clues one needs are therefore not only hidden in the two Latin texts, but also en route in the area – which is good news at this point.

4.1 The route from Blanchefort

The poet states that he is able to see scattered stones somewhere along the way. By mentioning this, he is making sure one knows exactly which route he is following. If one fails to see any of the landmarks he reveals, it stands to reason one has no chance whatsoever of reaching the destination.

The ‘dispersed stones’ lie on the route from the ‘white Fort’ – indicating Blanchefort, as was mentioned earlier, as it literally means ‘white fort’. The question, however, is in which direction?

Fig. 10. A menhir along the route

Resorting to Boudet’s book, one discovers that he specifically mentions menhirs (upright rocks) along the road from Blanchefort: ‘At the end of Roko Négro one sees again very clearly the different foundations which served to support the menhirs, but they are overturned and dispersed here and there on the flanks of the mountain, in the greatest disorder.’[35] The poet therefore undoubtedly has in mind exactly what Boudet is referring to here.

So for the first time, one knows exactly in which direction the route goes – in that of Roque Nègre, which is also the direction in which the poet’s friend was staring. Today, this is where the footpath from Blanchefort runs, so one can simply follow it. One is therefore walking in a southerly direction, on the way to the town of Rennes-les-Bains, which lies further down at the bottom of the valley.

4.2 A flight along this route

The poet also points out that this is the way a certain group once fled along to escape ‘the pursuit of usurpers’. It was while the ‘Brothers of the BEAUTY of black wood’ were fleeing that they scattered these stones along the way.

As almost everything in the poem has absolutely no bearing on anything ordinary, this was most likely also an unusual flight. Another fact supporting this assumption is that there are old mines close to Blanchefort wherein an important treasure had allegedly been hidden earlier. The poet could therefore be referring to the time when this treasure had been fled with from the Blanchefort area. Hence, the route he is indicating is nothing less than the way along which this treasure had been transported to a new hiding place. This, in turn, would mean that the riddle embedded in the poem contains the clues as to where the treasure had been taken.

The reference to the stones along the way therefore possibly relates to this fleeing with the treasure. It could be that the stones allude to the landmarks that had been specifically placed to guide one to the new hiding place, therefore representing the directions to be followed through the area.

The poet furthermore states that the ‘dispersed stones’ form a perfect cube when put together. Each ‘stone’ therefore contains a core element of the whole, or an invaluable clue in finding one’s way. As was mentioned earlier, the inner front cover of Le serpent rouge indeed shows a person squatting, deep in thought, in front of scattered ‘dice’, with the caption: ‘Discover the sixty-four stones one by one.’

4.3 The time of Sigebert

Throughout the poem, the poet draws on different ‘layers’ of meaning. In other words, in mentioning an object, or by using an image, he more often than not refers to something related to the object or image. The escape in this stanza could therefore be connected with not only one specific escape, but a few.

There are several flights in the rich history of the region that could be relevant, some of which occurred in the distant past, and others that more specifically bear on the detail in the poem. The events in the distant past are, however, significant, as they put later events in perspective.

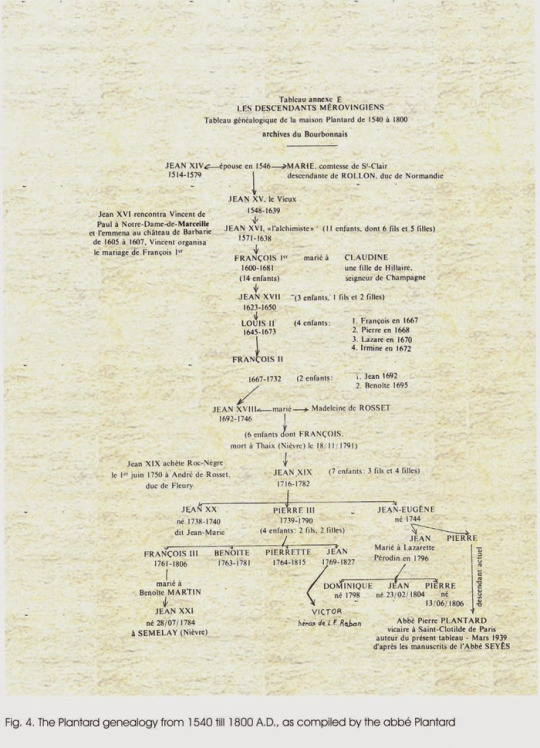

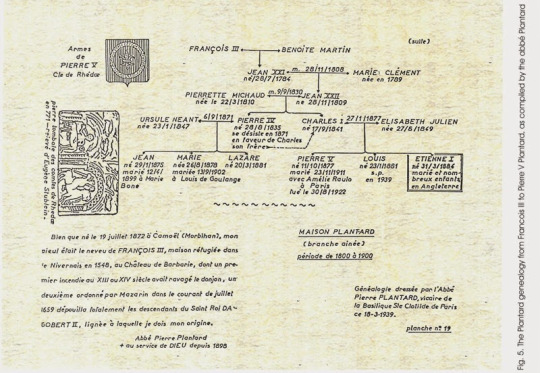

The earliest flight that the poet could have in mind, is that with the young Sigebert. Although this son of Dagobert II is not mentioned in earlier sources and therefore does not feature in generally accepted genealogies, his name is characteristically Merovingian; three of these kings have borne this name. However, he had been taken up as Sigebert IV in the genealogy in the document Le serpent rouge, which means the poet considers this version of history to be the truth. According to Jania MacGillivray, Sigebert is first mentioned in church records from the 16th century in the French National Library, as well as in 17th-century priestly documents of St. Vincent de Paul.

It is said that, following the murder of his father on the 23rd December, 679, in the woods close to Stenay, the three year-old Sigebert had been rescued by his half-sister Irmine, eight years his senior. A warrior (‘le Bellison’) called Mérovée Levi, a loyal subject of Dagobert II, subsequently rescued Sigebert from the clutches of Charles Martel and brought him to Rhedae. This Levi was apparently married to the sister of Bera II, the ruler of Rhedae and father of Sigebert’s mother, Gisélle. Like all the Merovingian kings, this Levi was also of Sicambrian descent.

The poet is therefore possibly referring to this flight with Sigebert from the ‘usurper’ Charles Martel. Although Charles Martel himself never went as far as dethroning the Merovingians, his son Pepin III did and subsequently became King of the Franks with support from the Catholic Church.

There seems to be evidence of the said flight with the young Sigebert to Rhedae. In the 42nd edition of the bulletin of the Le Cercle de Saint Dagobert II (June, 1996) – which I also stumbled upon during my visit to the Dagobert II Museum in Stenay – the author André Roth mentions a very old parchment that had earlier been in the possession of the monks of Orval in Belgium. After the French Revolution, the Black Sisters of the Chapel of Mary Magdalene in Mons, Belgium, placed it in the skull of Dagobert II for safekeeping. This ‘valuable parchment’ was written by Irmine, the daughter of Dagobert II and abbess of the monastery of Oeren. It tells of the rescue of her half-brother, Sigebert, who had subsequently been brought to this monastery before being taken to Rhedae, the capitol of the Razès, where he arrived on the 17th January, 681. There is also mention of the ‘Merovingian treasure’, which, according to Généalogie des rois mérovingiens, could refer to the treasure Dagobert II had sent to the Razès.

It appears that this parchment had actually been seen by several persons. On the 7th October, 1912, the bishop of Tournai’s secretary, the canon Cramme, inspected and copied it under the supervision of the Black Sisters and their head, mother Antoinette Richard. On the 31st December, 1941, the envoy of the Prince of Croy, Monsignor Delmette, visited Mons to take a photograph of the parchment as well as a part of the skull. Mother Bernadette de Haye apparently states in a letter that this parchment had later been taken by the Prince of Croy.

It is uncertain in whose keeping this parchment is today. If everything that is said about the parchment is indeed true, there can be no doubt as to the continued existence of the Merovingian bloodline. These events would then clearly be crucial in interpreting the later events in the Razès. However, like with the other parchments, one would have to wait until the experts have examined it before any valid conclusion could be drawn.

Besides this apparently invaluable document, other earlier documents also appear to refer to Sigebert, one of them being a deed of foundation dating from 718, mentioning ‘Sigebert, count of Rhedae, and his wife, Magdala’. This deed concerns the founding by Sigebert of the monastery of St. Martin of Albières. Upon an enquiry by a member of the University of Lille to the author of Le cercle d’Ulysse (who refers to this deed) about where this document could be found, the latter reportedly said it was kept in the French National Archives, but that it had not been categorised.

There is also the possibility that this deed – or another deed – relates to an incident in which Sigebert had been involved. According to the author of the document Au pays de la reine blanche (1967) (‘In the Land of the White Queen’), Sigebert and his son, Sigebert V, made a donation by means of a deed to the bishop Arbogaste as an expression of gratitude. This followed an incident at the Blésia fountain (Pontet) when Sigebert IV had been wounded in the gut during a pigsticking, upon which the bishop had come to his aid, saving his life. The abbé Pichon apparently also refers to this incident in his book Les diplômes mérovingiens.

After Sigebert IV died of a wound to the head in 758, he was buried in the crypt in the Rennes-le-Château church. The entrance to this burial chamber is said to have been covered by an engraved stone, the so-called Knight’s Stone, depicting a man and presumably a child with him on a horse. According to Les descendants Mérovingiens, this stone commemorates the flight with Sigebert to Rhedae. Saunière removed this stone. Later, a skull was reportedly discovered in the chamber, which could have been that of Sigebert.

4.4 Blésia (Pontet)

The fact that the poet refers to a flight at this point, which clearly also bears on the flight with Sigebert, could mean that he has a landmark that is connected with Sigebert in mind. The Blésia Fountain (or Pontet), where he had been wounded, indeed lies only a short distance further from Roque Nègre next to the tarred road.

The name Blésia had possibly been derived from ‘blesser’ (‘to wound’), which could also bear on the pigsticking incident. As was mentioned earlier, it may also be connected with ‘bles’ (‘gold’).

Following the footpath from Roque Nègre, it forks a short distance further on. The one path runs along the escarpment to Rennes-les-Bains, and the other down to the tarred road. If one takes the latter, one passes the Blésia Fountain on the way to Rennes-les-Bains.

4.5 The Sun King

Although the flight with the young Sigebert to Rhedae is an underlying theme in this stanza, the flight the poet is actually referring to here dates from a later period in history. This took place when one of the ‘usurpers’ – referring to the French dynasties after the Merovingians had been dethroned – apparently attempted to get his hands on the treasure of Blanchefort and the ‘Brothers’ hastily fled with it.

One of the French kings who was not only very interested in the Razès area, but evidently also in the treasure, and who sent one of his subjects searching for something that had allegedly been hidden here, was Louis XIV, the Sun King. His minister of finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, apparently searched and dug all over the place, among others at Blanchefort – exactly where, according to the poet, the treasure had been moved from. The fact that Colbert returned empty-handed is in keeping with the assumption that the safekeepers of the treasure had gotten away with it in time. It would therefore make sense to take a closer look at these events.

4.6 The brothers of the beauty of black wood

According to the poet, those fleeing from the ‘usurpers’ were the ‘Brothers of the BEAUTY of black wood’ – the same ones who scattered the ‘stones’ along the way. It was therefore the persons who escaped with the treasure and who were responsible for compiling the directions that future generations would need to be able to find the new hiding place.

To find out who these ‘Brothers’ are, one must obviously first determine who ‘the BEAUTY of black wood’ is. This is also not the first time the poet refers to a beauty: In the previous stanza, he mentions the residence of the sleeping beauty where he is headed.

‘[T]he BEAUTY of black wood’ may very well allude to statues made of black wood. In La vraie langue celtique, Boudet refers to such a statue of the Virgin in Marseille. It appears that this Black Virgin is connected with an alternative tradition in the Catholic Church that had been kept secret throughout the centuries. In The Cult of the Black Virgin [36], Ean Begg suggests that it represents a pagan goddess under a new banner. Some experts indeed regard the oldest madonna in the world, the Brown Virgin of the Catacomb of Priscilla in Rome, as a statue of Isis.

According to Deloux and Brétigny [37], the Black Madonna of Blois, which was honoured there up until the revolution, is the ‘eternal Isis’ honoured by the initiates of the Prieuré de Sion. To top it all, Pierre Plantard himself stated that the Black Virgin is Isis, and that she is called ‘Notre-Dame de Lumière’ (‘Our Lady of Light’).

If the ‘BEAUTY of black wood’ does indeed refer to the Black Virgin, the ‘Brothers’ who are associated with her are most probably none other than the brothers of the secret Prieuré de Sion – which is reportedly also called ‘the ship of Isis’!

Yet another very interesting fact is that the biggest enemy of Louis XIV and his first minister, cardinal Mazarin, was the secret order, the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement (‘Order of the Holy Sacrament’). According to the authors of The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, this group ‘conformed almost perfectly to the image of the Prieuré de Sion’ [38]. Their ‘centre of operations’ was the St. Sulpice Church in Paris. (The mother church of St. Sulpice, St.-Germain-des-Près, was apparently built on an earlier temple of Isis.)

4.7 The tombstones of Marie de Blanchefort

According to an article in the Vaincre of September 1989, some of the prominent families of the Razès were directly or indirectly involved with the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement. This would imply that they were the ones protecting the interests of the Compagnie in the south. It is therefore quite possible that these interests relate to the ‘secret’ of the Hautpoul-Blanchefort family, and even to a treasure hidden in the area. This would mean that these families were the ones responsible for moving the treasure in the time of Louis XIV. It therefore stands to reason that they would also have been responsible for compiling the directions to the new hiding place.

Enter Marie de Blanchefort, who belonged to the mentioned families of the Razès and who figures very prominently in the Rennes-le-Château mystery. On her tombstones appeared information that one later on discovers is indispensable in decoding the hidden secret message in the second text, which most probably relates to the hiding place of the treasure mentioned in the first text. This would imply that it is the exact same treasure which Louis XIV had been after.

Unfortunately, the writing on Marie de Blanchefort’s tombstones does not exist anymore, as Saunière had deliberately removed it. However, it is said to have been published in a book by Eugène Stublein entitled Pierres gravées du Languedoc (1884) (‘Engraved stones of the Languedoc’), but of which not one single copy is apparently still in existence. In 1962, extracts from this book were apparently published under the name of abbé Joseph Courtauly. As with many of the other documents related to Le serpent rouge, the true author of this writing is most likely Pierre Plantard or Philippe de Chérisey. Exactly from where either of them would have obtained this information is not clear, but as Henry Lincoln points out in The Holy Place, at least one of these epitaphs appeared in a leaflet written by E. Tisseyre entitled Excursion du 25 juin 1905 à Rennes-le-Château (‘Excursion of the 25th June, 1905, to Rennes-le-Château).

Fig. 11. The tombstones of Marie de Blanchefort

4.8 The second Latin text

As was just mentioned, the secret message in the second text can only be deciphered with the aid of the information on Marie de Blanchefort’s tombstones. The poet also refers to this second text when stating it is thanks to the ‘manuscript’ of his friend that it is now easier to find his way.

As was also mentioned earlier, deciphering this message is an entirely different story. As it involves a highly intricate procedure, it would be virtually impossible to decode the message without the input of someone who has knowledge of this procedure. Philippe de Chérisey somehow gained access to it, but clearly did not know how to apply it. He was blissfully under the impression that the current 26-letter alphabet could be used, whereas only the old French alphabet without the w yields the correct results. The exact procedure – in all probability supplied by Pierre Plantard – can be found in an appendix to Henry Lincoln’s book The Holy Place. Lionel and Patricia Fanthorpe also provide a very clear exposition of it in their book, Secrets of Rennes-le-Chateau [39].

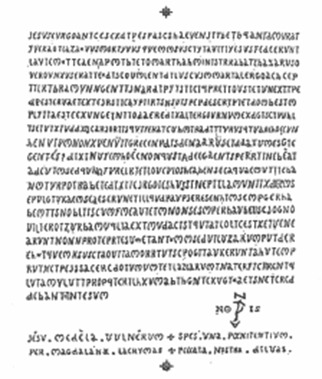

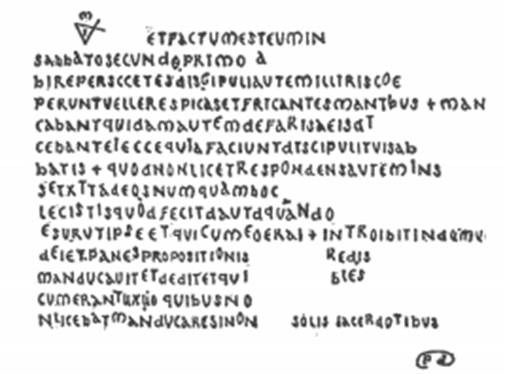

The writing in the second text is much more compact than that in the first, and the text itself is written in block-form. Close to the bottom right is a peculiar symbol with ‘NO’ and ‘IS’ written on either side, which spells ‘NOIS’ – the inverse of ‘Sion’. There is also an N above and an upside-down A beneath this symbol. Right at the bottom, separate from the main body of the text, are an additional two lines. Each of these consists of six words, all separated by either a full stop or a tiny cross. Lastly, there are two odd roselike symbols in the centre right at the top and right at the bottom of the entire text (see Figure 12).

Fig. 12. The second Latin text

Upon closer examination, one discovers that after every sixth letter in the Latin Biblical text, another letter had been inserted. There are 140 of these letters altogether, which are clearly those containing the secret message. An additional eight very tiny letters have been inserted randomly in the text. Put together, these letters spell ‘rex mundi’, which is Latin for ‘king of the world’. Contrary to the secret message in the first Latin text, which states that the mentioned treasure belongs to Dagobert II and to Sion, these words imply that the treasure ultimately belongs to the ‘king of the world’, who, according to the compiler(s), will apparently come from the Plantard family line. Over and above the Messianic connotations of these words it is therefore implied that the treasure is of such value that only the ‘king of the world’ would have a right to it.

One cannot help but wonder whether this hints at the fact that the discovery of the temple treasures of Jerusalem would play a role in confirming the kingship of such a messianic figure.

4.9 Deciphering the second secret message

Right, here we go.

The 140 letters inserted in the Biblical text are divided into two groups – 64 at the beginning and 64 at the end, with the remaining 12 in between. The number 64 immediately calls to mind the ‘sixty-four dispersed stones’ mentioned in this stanza. One later on discovers that this number is also indispensable in solving the riddle. The 12 letters in the middle are subsequently omitted from the cipher, which leaves a total of 128.

These 128 letters are then systematically transformed to other letters by means of two key phrases – which are to be found on Marie de Blanchefort’s tombstones. The first key phrase is compiled from letters on the vertical tombstone, which seem quite odd and even incorrect, namely T, M, R, O, e, e, e, p. However, when rearranged, these letters spell ‘MORT épéé’, which means ‘death, sword’ – the exact two words which the poet emphasises in the previous stanza. The second key phrase consists of all 119 letters on the vertical tombstone, as well as the letters P and S and the words ‘PRAE-CUM’ on her horizontal tombstone – which once again give a total of 128 letters.

What immediately strikes one about the first key phrase is that ‘épéé’ (‘sword’) is an unusually bad choice for a codeword. As Ted Cranshaw put it in his article: ‘Of all possible four-letter keywords in the French language, épéé is the worst.’ However, it may very well be that the person who had devised the code had deliberately chosen this very word due to its symbolic meaning. As was mentioned earlier, one edition of the Circuit also has a sword on the cover (see Figure 6). The emphasis on a sword could allude to revenge – a theme that recurs later on in the poem when the poet describes the red serpent as ‘red with anger’. This serves as one more reason that it is highly unlikely that the person responsible for the encoding had gone about it just for fun.

Now for the mentioned transformation. In the first step of the procedure, the key phrase ‘MORT épéé’ is written repeatedly above all 128 letters. The numerical value of each letter in the 25-letter alphabet is what is crucial here: a = l, c= 3, e = 5, and so on. The numerical values of each of the two letters on top of each other are then added to yield the numerical value of a third letter, e.g. 1 + 19 = 20. (As the relevant alphabet only consists of 25 letters, 26 is again regarded as 1.) On completion, one then has a new series of 128 letters that correspond to these acquired values.

This procedure is repeated with the second key phrase, namely the 128 letters on both Marie de Blanchefort’s tombstones. These letters are now written above the acquired 128 letters for a further transformation, but this time the key is written backwards – in other words, the last letter is written first, the second last letter second, and so on. The numerical values of each of the two letters on top of each other are then, once again, added to finally yield a new series of 128 letters.

For the final step in the decoding, one needs two chess-boards. Just as 64 represents the number of blocks in a cube (as the poet states), there are 64 blocks on a chess-board (8 x 8). This is why the numbers 64, as well as 128 (64 x 2), are so significant.

The 128 letters acquired by means of the transformations are now unpacked on the blocks of the two chess-boards. Next, a closed knight’s tour (see Figure 13) is used to at last unravel the secret message. This knight’s tour entails the letters being taken out one after the other according to the moves of a knight on the board. When the knight has landed on every single block, the tour is completed.

Having performed the knight’s tour on both chess-boards, one should finally have the deciphered message!

This specific knight’s tour, devised by the skilled Swiss mathematician Leonhard Paul Euler, reveals a striking geometrical pattern, in which a shape partly resembling a pentagram and partly a hexagram becomes visible. Besides the fact that the hexagram is highlighted in the poem, it also appears on the Hautpoul-Blanchefort coat of arms.

Fig. 13. The knight's tour to be used

The hidden secret message in the second Latin text reads:

‘BERGERE PAS DE TENTATION QUE POUSSIN TENIERS GARDENT LA CLEF PAX DCLXXXI PAR LA CROIX ET CE CHEVAL DE DIEU J’ACHEVE CE DAEMON DE GARDIEN A MIDI POMMES BLEUES.’

This could be translated as: ‘SHEPHERDESS NO TEMPTATION THAT POUSSIN TENIERS HOLD THE KEY PEACE 681 BY THE CROSS AND THIS HORSE OF GOD I COMPLETE THIS DEMON GUARDIAN AT MIDDAY BLUE APPLES.’

There is, however, one more thing: The fact that a geometrical pattern is to be drawn according to certain pointers in the first text, leads one to suspect the same holds true for this one. Upon closer examination, it soon becomes clear that some kind of pattern has indeed been hidden in the text: If one connects the roselike symbols at the top and bottom of the text, then produces another line through the two tiny crosses in the two separate lines at the bottom, these two lines intersect more or less in the centre of the parchment.

The implications of these geometrical patterns are as yet an enigma, but progressing on the route, one discovers how brilliantly and ingeniously they have been devised.

35. Boudet, H. 1886. La vraie langue celtique ... Carcassonne. Reissue: 1984. Belisane: Nice, p. 231.

36. Begg, E. 1985. London: Arkana,

37. Deloux, J. & Brétigny, J. 1982. Rennes-le-Château. Capitale secrète de I’histoire de France. Paris: Editions Atlas.

38. Baigent, M., Leigh, R. & Lincoln, H. 1982. London: Jonathan Cape, p. 183.

39. Fanthorpe, L. & P. 1992. York Beach: Samuel Weiser.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Red Serpent: 3. Finding the Way

Dans mon pélérinage éprouvant, je tentais de me frayer à l'épée une voie à travers la végétation inextricable des bois, je voulais parvenir à la demeure de la BELLE endormie en qui certains poètes voient la REINE d'un royaume disparu. Au désespoir de retrouver le chemin, les parchemins de cet Ami furent pour moi le fil d'Ariane.

During my testing pilgrimage, I attempted to clear a path with the sword through the impenetrable vegetation of the woods. I wanted to reach the residence of the sleeping BEAUTY in whom certain poets saw the QUEEN of a vanished kingdom. Desperate to find the way, the parchments of this Friend were for me the thread of Ariadne.

In this stanza, things start getting tricky. Sure enough the poet confirms there is a route to be followed through the area of Rennes-les-Bains — which he now terms a ‘pilgrimage’ — but immediately after that he fires the first of the riddly clues. Although he reiterates that his friend’s parchments would eventually lead one to the ultimate goal, one gets the uneasy feeling that words like ‘testing’ and ‘desperate’ are an indication of things to come.

3.1 The Rennes-les-Bains region

When driving from Carcassonne in the south of France to the Razès, one takes Route 118 south, which runs through Limoux and Alet-les-Bains. The road winds all along the Aude River, and here and there, caves and holes in the rocks flanking the river are visible. As this is wine country, vineyards meet the eye most of the way. Strangely, one advertising sign posted every couple of kilometres shows a grapevine in the form of a serpent.

Just past Alet-les-Bains, to one’s left, rises Castel-Nègre, where once was the Hautpoul family’s enormous wine-cellar. Close to Couiza one turns onto the road going east in the direction of Coustaussa, Serres and Arques. A few kilometres further, shortly before Serres, one takes the turn-off to the south to eventually reach the Sals Valley wherein Rennes-les-Bains lies.

The entrance to the valley is marked by a deep ravine. To one’s left is the mountain Cardou, with distinct white rock formations on the slopes called Lampos. The white rock formation right at the top on the right-hand side is Blanchefort. The striking black rock formation a little further on, quite a bit lower down the slope on the same side of the road, is Roque Nègre. When one is halfway between these two formations, the Sals River makes a sharp curve, which one crosses before continuing along the stream.

Somewhat further down the road one crosses a bridge, next to which the ruins of warmbaths called the Bains Doux are found. The water from the fountain rising here is hot and links up with the Sals River in a cloud of steam.

Just around the next bend to the right, the picturesque town of Rennes-les-Bains lies in full view. Like all the small towns in the south of France, it has a peaceful, timeless atmosphere with charming old buildings lining either side of the main road. About midway through the town, the square is to one’s left, which also hides the entrance to the little church where Boudet had been priest. One block further down the road, one takes a right turn to the parking lot against the hill, from where the area is explored on foot.

To get to Blanchefort, one takes the hiking trail starting not too far from the parking area. Walking up the hill in a northerly direction with the narrow tarred road, one soon finds the directions to it. It takes roughly 60-90 minutes to reach Blanchefort. The footpath runs gradually higher up the plateau until it finally delivers one at the top.

Walking along this path is an exceptionally pleasant experience. As quite a bit of natural forest is to be found here, the area is vivid green, with fir-cones and small, pretty red fruit strewn all along the way. In places the forest is so dense one feels completely secluded, the smell of nature an overwhelming presence. All the while, the murmuring of the Sals River keeps one’s footsteps company.

Shortly before one reaches Blanchefort, the path takes a sharp turn to the left, from where a very unobtrusive little path leads one down to Roque Nègre. This rock formation has an intense dark brown colour and is camouflaged by thick bush. As it has fairly steep sides, I would not recommend climbing it without the proper gear.

Reaching Blanchefort, the first challenge is to clamber up to the top. On a day when the wind is strong, one keeps seeing oneself freefalling from the rock-face while clawing up the rough surface. There are, however, other spots that provide an easier climb.

Once at the top, one has an exceptional view of the valley. It is striking how vast the area actually is. The ruins of an old fort are still visible, exactly as Boudet describes: ‘On the left bank of the Sals ... the natural point of this rock (the crag of Blancfort) has been raised in the middle ages, to allow the construction of a fort serving as an observation post. There remain some ruins of masonry testifying to the existence of this fort’ [30]. To the south, Roque Nègre is clearly visible lower down the slope and on the horizon one can make out the reef of the Serrat plateau behind Rennes-les-Bains.

This is indeed the place where the poet’s friend is standing ‘as a column on his white rock, looking attentively towards the south, beyond the black rock’.

3.2 A pilgrimage

Right at the beginning of this stanza, the poet mentions a ‘pilgrimage’. It is significant that he links the route through the area with specifically such a journey. In order to keep up with the clues which he provides, it stands to reason one has to determine exactly which pilgrimage he has in mind.

The most famous Christian pilgrimage is the one to Jerusalem and walking along the 14 Stations of the Cross to the grave — the Via Dolorosa of Christ. It could therefore be that the poet is alluding to the Way of the Cross and the 14 Stations thereof, which are depicted in all Catholic churches. The logical place to search for this would then be in the Church of Mary Magdalene in Rennes-le-Château.

The 14 Stations of the Cross in the Rennes-le-Château church indeed present quite a few surprises, not the least of which is that they contain outlandish peculiarities. Indeed, upon closer examination of the first Station, one discovers that it in actual fact relates to the geographical directions in this stanza of the poem!

In this Station (see Figure 8), Jesus (on the left) is depicted standing in front of Pilate (on the right), who is sitting on a raised stone surface that looks like a platform. Jesus is dressed in white. Next to Pilate is a small black male holding a basin with water in which Pilate is washing his hands in ‘innocency’. Between Jesus and Pilate, in the background, there is a prominent figure; possibly the high priest. He is dressed in a green outer robe and a yellow undergarment, and he is holding his right hand in the air with his index finger pointed. Between Pilate and the black man, right underneath the water basin, is an ornamental golden lion.

Fig. 8. The first Station of the Cross in the Rennes-le-Château church