Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Hi Skylar, thanks for sharing this.

I agree that the environment is too often seen as separate from humanity, and not as something that we are part of. As humans, we like to believe we are smarter and more sophisticated than the other, simpler organisms we share this planet with. I think this viewpoint is a seriously flawed way of looking at the world, and it shows how disconnected we are from nature. I think many people with our education in the sciences can see the humorous irony in this way of thinking as well, as us humans are singlehandedly causing a climate and a biodiversity catastrophe that we seem increasingly powerless to stop. In our reading from this week the author makes a point saying how “we are inextricably bound up in the processes of life. With every breath in and out we are part of the natural systems that surround us.” (Rodenburg, 2019). Embracing this interconnectedness requires us to step back and look at what is truly important. Understanding that valuing monetary wealth and success above all else is not making us happier and is destroying our planet is an important first step. As nature interpreters this is our biggest challenge; changing the way people look at the world from “what can I get from it” to “how can my actions make the world a better place”.

Rodenburg, J. (2019, June 17). Why Environmental Educators Shouldn’t Give Up Hope [Review of Why Environmental Educators Shouldn’t Give Up Hope]. https://clearingmagazine.org/archives/14300

Final Blog Prompt #10: Cultivating Hope and Connection: Developing My Personal Ethic as a Nature Interpreter

Developing My Personal Ethic as a Nature Interpreter

As I navigate and grow within my role as a nature interpreter, I have premised myself as having a deep respect for the environment, a commitment to furthering education and a dedication to creating rich and meaningful connections between both nature and humans. I hold the belief that interpretation far exceeds the sharing of knowledge as at its core, it is a celebration of storytelling, sparking curiosity and the encouragement of embracing stewardship of our natural world. As evidenced in, Why Environmental Educators Shouldn’t Give Up Hope by Rodenburg, it can be easy to find oneself discouraged by the harsh realities of climate change, environmental degradation and public apathy. However, hope is paramount within environmental education, and my role as an interpreter is to grow a sense of optimism in others.

Beliefs That Shape My Approach

I bring numerous core beliefs within my role as a nature interpreter. Firstly, I feel that nature is an entity that should be both easily accessible and strikingly meaningful to all individuals, regardless of their previous experiences and backgrounds. The environment is a landscape that both surrounds us and impacts us each and every day and should not be considered simply something that exists in the distance as an abstract concept. I believe that individuals protect that which they care about and understand therefore, effective interpretation must Inspire individuals to find a personal connection between themselves and the natural world.

Rodenberg's work illuminates the manner in which educators should balance the realities of environmental issues with messages of empowerment and hope for our world. fear itself is not capable of inspiring action and instead, individuals should be encouraged to understand that change is possible and that their daily efforts truly do matter. this offers reinforcement to my belief that learning is truly a lifelong journey where people are implored to seek answers to their questions, explore Solutions and recognize their own capacity to hold agency as environmental stewards.

Responsibilities I Hold

Upon reflection of these beliefs, I acknowledge numerous key responsibilities. I hold an ethical duty to share information in an accurate and honest manner and I must ensure that each of my messages are founded scientifically with both evidence and best practices practices and Environmental Education as my driving force. Similarly, I hold a responsibility to remain an advocate for nature where I encourage behaviours that are sustainable and where I assist individuals to recognize their role in conservation efforts. I must develop inclusive and engaging spaces where all visitors feel valued heard and welcome.

Rodenberg highlights that environmental educators should focus on success and progress instead of solely on negative outcomes. this will result in my role shaping itself to not simply warn people about issues of concern such as deforestation pollution and species loss but rather focus on showcasing restoration efforts, Community-led conservation projects and ecosystems that show resilience.

Furthermore, I believe that as a nature interpreter, I must also be intentionally self-reflective. It is essential that I continually and routinely assess my own bias that can exist in my thinking and I must acknowledge my limitations in terms of knowledge therefore prompting me to be open to learning from other individuals which includes the visitors in which I interact.

Approaches That Align with My Personality

As an individual, I am connected to an experiential and participatory approach to interpretation. Beyond simply the provision of information I prefer engagement with people through experiences which are interactive and can include hands-on activities, guided discussions and storytelling that evoke both personal reflection and emotion. I have found that humour and related analogies alongside personal anecdotes best help me align the gaps between abstract ecological concepts and my own everyday life.

Rodenberg reveals how emotional connections contribute to Environmental education. Individuals recall stories, experiences, and personal moments that are far more in-depth than warnings and statistics. this reinforcement of my own beliefs highlights that interpretation reaches far beyond the giving of information into a world of Deep engagement. if I can make an individual laugh or reflect or feel a personal connection To an ecosystem habitat or animal, I am far more likely to have left a lasting impression and impact on that individual.

Additionally, I recognize the importance of adaptability. each audience is unique and interpretation should be matched and mirrored to the needs and interests of those present. Whether offering leadership to a group of children alongside their first nature walk or through engagement with an experienced group of outdoor enthusiasts my personal goal is to connect with individuals where they are in that moment and make the nature around them relevant to their own lives.

Looking Ahead

As I continue to grow as a nature interpreter I hope to deepen my comprehension of environmental communication strategies and will work on creating presentations which hold greater inclusivity and which seek out opportunities to connect with diverse communities. Why Environmental Educators Shouldn’t Give Up Hope Offers insight and a reminder that throughout times of uncertainty, my role is to inspire rather than to focus and dwell on despair so that I can best equip individuals with both the knowledge and the motivation to engage and act.

Certainly, interpretation is a bridge which connects people to Nature and I am thrilled to deepen my connection in meaningful ways. through the embracing of responsibility curiosity and adaptability, I will inspire others to view nature as not simply something to observe but as an entity which is alive and which can be actively engaged with and protected. Of pivotal importance is my hope to carry forward the lesson that hope is truly not naive but rather a necessity.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Veronica, great post. You make a bunch of good points here.

I agree that it is critically important for nature interpreters to focus on developing programming for children particularly in this day and age. As kids are the next generation of environmental stewards and their generation will be dealing with the most severe impacts of climate change, I believe that fostering a healthy relationship with the outdoors is paramount. I think too often adults get bogged down with all the negative news with respect to climate change nowadays. While the wealth of knowledge surrounding climate change only grows, many would argue that we owe it to the next generation to parse through this information to effectively communicate the facts in a way that is inspiring and encourages critical thinking. However, I don’t think it has to be this complicated either as you also point out. The author of this week’s reading says his job description would be simply “to help reveal wonder and cultivate awe” (Rodenburg, 2019). As children are naturally curious and love learning, simply providing them with routine access to nature might be all it takes to instill a love of the natural world. Understanding how to make age-appropriate programming for kids is so important to being an effective nature interpreter I have learned. And as you point out, sometimes this “programming” might simply involve unstructured playtime.

Rodenburg, J. (2019, June 17). Why Environmental Educators Shouldn’t Give Up Hope [Review of Why Environmental Educators Shouldn’t Give Up Hope]. https://clearingmagazine.org/archives/14300

BLOG 10: My Interpretation Ethics 🐻

As I reflect upon my journey as a nature interpreter, I can see how much growth I have made just within the last few months with the influence of this course. My past experiences working in summer camps and children’s sports, my role as a nature interpreter pertains most to introducing children to the natural world. My personal ethics then surround facilitating safe exploration, emphasizing inclusivity and welcoming environments, as well as keeping stewardship at the forefront of interpretation.

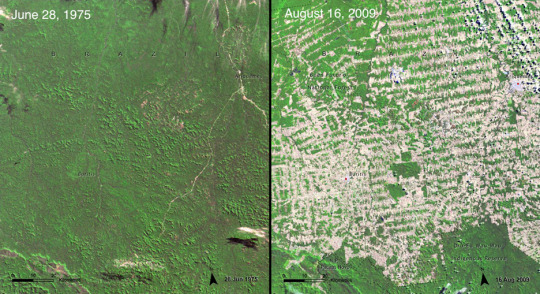

My ethics blossom from both a love for the beauty of the natural environment but also from a place of disappointment in how we are treating it. The anthropogenic effects of humankind are destroying the earth from pollution, to expanding infrastructure, to destroying habitats and ecosystems and plenty more. I believe that the only way to make a change is to help inspire a generation who has a deep personal connection to their role as an environmental steward. As discussed in the text, young children are not to be burdened and overwhelmed with the intricacies of environmental policies but are at the prime stage to foster their natural relationship. As an educated adult who works with children in outdoors programs, I believe it is my responsibility to facilitate an inclusive, welcoming environment which allows children of all ages and abilities to explore the outdoors. As I gain more formal training and learn from texts like Interpreting the Natural World, I improve my interpretation skills, especially in creating and facilitating accessible programs.

Anthropogenic effects: Rainforests being turned into farms (Plumer, 2015).

Anthropogenic effects: Man-made islands in Dubai taking over ocean habitats (Plumer, 2015).

An area in which I hope to improve on in my interpretation journey is educating myself on Indigenous ways of knowing. These communities are one with Mother Earth and their extensive knowledge is “Holistic, cumulative and dynamic” (Government of British Columbia, 2023). The artwork below is that of Cree Indigenous artist Tenessa Gagnon, I thought to include it because it is just so beautiful, and Gagnon describes her relationship with nature as “one of equality, rather than superiority” (Government of British Columbia, 2023). Humans are at the top of the food chain, and we believe we have the rights to use natural resources and land however we please that best profits our economy. This way of thinking perpetuates capitalistic ideals and promotes harmful consumerism which destroys the environment and peoples lives. Sustainable living is a core concept of Indigenous living.

Sustainability has always been one of my core ethics, in nature interpretation and within my own daily life. One of my biggest passions is sustainable fashion. Almost all of the clothes that I own are second hand and I love repurposing old items or fabrics. In my Entrepreneurship course in high school, I designed a company which educated the public on how to mend and repurpose clothing to avoid the tonnes textile waste that ends up in landfills. What I learned in this process is that as a population we are not avoiding sustainable practices but simply have lost the skills to do so. Sewing and mending used to be integral skills for everyone, but we have lost the general sense of community with nuclear families. We now fail to pass along generational knowledge. This connects back to Indigenous practices, as generational teachings is what they do so well. Nature interpretation and teaching is not just a paid position but can be implemented in the ways we speak with those close to us.

The other week I came across a social media influencer that talked about bring back unguided play outdoor and encouraging exploration. She is a mother of two young kids. Although I can no longer find the video I originally cam across, the creator reflects upon her own childhood of playing in the raw outdoors – no playgrounds, or toys, or planned activities. She explains how this lack of overstimulation and guidance allowed her to develop her creativity and inquisitive nature. Implementing this with her children, she observes that there is much less conflict that arises within and between the children as well.

This concept of self-directed play and exploration is key for children in developing their relationship with nature – influencing their worldview. This topic is covered in chapter 6 of the textbook, Beck and Cable (2018) discuss the loss of free-play in our technologically advancing world. They emphasize the importance of natural curiosity,

“From 7 to 14 years, a growing sense of discovery and excitement helps to extend ties beyond the family to parts of the society and the earth’s community of life.” (pg. 115)

Through developing a relationship with nature that is uniquely theirs and created through personal experiences, children can build a strong foundation of respect for the natural world. This gives them a strong personal basis for their future values and ideals. An article titled What Happened to Playing Outside, covers most of the same topics I have previously mentioned, but introduces the analysis of how as a society we have reached this point (Schwartz, 2016). Schwartz (2016) emphasizes an increase in fear within populations since the 1980’s. Intensified after 9/11 and with 24/7 media reports, parents are fearful of the harms of the outdoors – strangers, bugs, rashes, animals, etc. (Schwartz, 2016). This is where nature interpretation and education can allow populations of all ages to become more comfortable and confident in the natural world. Risky play is crucial for child development, and understanding one’s autonomy can aid in safe exploration.

My personal ethics—rooted in inclusivity, sustainability, and stewardship— continue to shape my approach to nature interpretation and are the foundation in any position I assume. The degradation of the beautiful world is the fuel to my fiery passion to make a difference. I hope to instill confidence in the younger generations so they may safely explore the world around them. I can recognize my need to try to control situations but believe in the importance of self-guided play for children. I am committed to expand my understanding and application of Indigenous ways of knowing, through classes listing to community members, and reading books. The western perspective of stewardship is just one singular way of approaching a human-nature relationship. The more I can widen my perspectives the better interpreter I can become. This course in particular has allowed me to explore unique topics of previous interest and open my eyes to new ideas. I truly believe this course content has helped shape me into a more well-rounded interpreter.

______________________________________________________________

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting cultural and natural heritage for a better world. Sagamore-Venture.

Government of British Columbia. (2023, September 28). Indigenous ways of knowing. Province of British Columbia. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/research-monitoring-reporting/reporting/indigenous-ways-of-knowing

Plumer, B. (2015, April 7). 15 before-and-after images that show how we're transforming the planet. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2015/4/7/8352381/anthropocene-NASA-images

Schwartz, S. (2016, April 5). What happened to playing outside? Ecohappiness Project. https://ecohappinessproject.com/what-happened-to-playing-outside/

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 9

As a blossoming nature interpreter, I’ve learned a lot about what it takes to be a good communicator. The methods I employ to interpret the natural world have been shaped by early experiences, travel, work as a bird guide, close friends and my university journey. Foremost, I can thank my parents for curating a love for the outdoors. I have been very lucky to have had opportunities during my childhood to explore the province of Ontario and beyond. Experiential learning has always been the most impactful for me. The adage, “seeing is believing” is so true! Memorable experiences like glimpsing my first snake, catching my first dragonfly, and identifying my first sedge to species have instilled wonder and excitement. This admiration of living things, plus time spent observing them in beautiful and remote spaces, with people from many different backgrounds has further influenced me to the point of shaping my world view and political orientation.

A motto I will always carry with me is that there is always something to learn about the natural world wherever you are, whether that be in a city or out in the wilderness. There will always be something about nature that piques my interest and inspires me to step out of my comfort zone and learn new things. This excitement and sense of wonder is something I want to pass on to others, because there is a growing disconnect between people and nature. Children are spending less time outdoors. For every child stuck inside glued to a screen rather than playing outdoors there is a missed opportunity. Nature is a teacher that everyone has access to; it encourages physical activity, fosters critical thinking and boosts mental wellbeing. “Children today are given few opportunities to be outside. In a school system rife with worry about liability, it is simply easier to stay indoors. Insurance rates are cheaper if kids are contained, accounted for, and “safe” inside.” (Rodenburg, 2019). This quote articulates a disturbing trend, where the outdoors is seen as dangerous, and needing to be “babyproofed”. God forbid a child is stung by a bee, ingests a berry, or falls while climbing a tree!

It’s unfortunate, because I have found that quite possibly the easiest way to entertain a young child is to take them on a nature walk. The author then makes the point that too often we feel the need to educate children about unsettling topics like climate change and biodiversity loss, where “Young children are, however, always ready to love the natural world. Connecting with nature is about establishing a relationship and building intimacy” (Rodenburg, 2019). Without the chance to develop that relationship organically and with innate joy, how can children be expected to appreciate the need to value and protect the natural world?

Rodenburg’s quote makes me think back to last weekend, when I went out with friends to look for salamanders. Every year in March on rainy, warm nights salamanders migrate, often across a still snowy landscape, to vernal (ephemeral) pools to breed. We positioned ourselves next to one such pool and waited. A steady trickle of salamanders began to arrive, mysterious in its resolve. While salamanders encompass an impressive amount of biomass proportional to other common species like the White-tailed Deer, they are hard to spot (Campbell et al., 2024). All five of us were captivated by this migration spectacle. I can only imagine how ecstatic I would have been if I were 10, watching these incredibly cool, almost mythical creatures. I would almost certainly be inspired to trade in my Pokémon cards for a flashlight and rubber boots! Yet what teacher would dare, or even be allowed to venture out after dark with their class to experience such everyday magic?? After the salamander walk, I fell down a rabbit hole; trying to understand the complex biology of one of the species we saw- a unisexual complex with genomes of multiple species, where all individuals are female. They essentially “steal” the sperm from males of a related species to initiate development of their eggs, while amazingly this male genome is rarely incorporated into the developing embryo (COSEWIC, 2016)!

Unisexual Ambystoma salamander (W. Konze)

My point with this anecdote is that you can have special experiences essentially in your own backyard, if you know where to look. Passing on this “secret knowledge” to children and adults is my responsibility as a nature interpreter. To appreciate nature, you don’t have to be a scientist; but seeing for yourself and learning a few mind-boggling facts about a salamander that lives throughout southern Ontario might just be enough to get someone “hyped up” about the natural world.

The following quote from our textbook embodies how I want to impact society through my interpretation, “Interpreters encourage people to see the world as interconnected and diverse. They show examples of our ability to alter the planet’s life support systems. They encourage taking responsibility as stewards for the natural world.” (pg. 55; Beck et al., 2018). Through taking an enthusiastic approach to nature interpretation I hope to encourage critical thinking about priorities in modern society. Is making money, having a nice house and an expensive car most important, or is living simply, enjoying the natural world, and taking care of the planet something to aspire to? Is leaving a desolate, inhospitable planet for the next generation really something we want as a society?

These are the big questions I hope to get people considering. Yet you don’t have to be “doom and gloom” to get people to think about uncomfortable topics. All you need to do is illustrate the innate value of nature, while providing the facts, perspectives, and experiences to think critically. I believe that gently, or even covertly incorporating conservation and lifestyle themes into interpretation that fosters every learner’s discovery and excitement is the way to go.

My responsibility as a nature interpreter is to get people excited about the incredible biodiversity in our own backyards. Communicating what I know - along with my passion - in a way that is accessible to everyone; engaging with this fantastical, stranger-than-fiction, outdoor world via experiential learning, is how I will try to create the change I would like to see in our ailing world.

Beck, L., Cable, T.T., Knudson, D.M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage: For a Better World. Sagamore Publishing LLC. https://sagamore.vitalsource.com/books/9781571678669

Campbell, E. H., Fleming, J., Bastiaans, E., Brand, A. B., Brooks, J. L., Devlin, C., Epp, K., Evans, M., M. Caitlin Fisher-Reid, Gratwicke, B., Grayson, K. L., Haydt, N. T., Hernández-Pacheco, R., Hocking, D. J., Hyde, A., Losito, M., MacKnight, M. G., Tanya, Mead, L., & Muñoz, D. (2024). Range-wide salamander densities reveal a key component of terrestrial vertebrate biomass in eastern North American forests. Biology Letters, 20(8). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2024.0033

COSEWIC. (2016). Assessment and Status Report on the Unisexual Ambystoma Ambystoma laterale https://wildlife-species.canada.ca/species-risk-registry/virtual_sara/files/cosewic/sr_Unisexual%20Ambystoma_2016_e.pdf

Rodenburg, J. (2019, June 17). Why Environmental Educators Shouldn’t Give Up Hope [Review of Why Environmental Educators Shouldn’t Give Up Hope]. https://clearingmagazine.org/archives/14300

0 notes

Text

Something about nature that I find incredibly interesting is the ocean. It is home to many species, and since it’s so large, about 80% of it remains undiscovered or unknown. The most fascinating aspect of the ocean, in my opinion, is its species. It is the habitat of the largest living animal, the blue whale and many creatures that have yet to be discovered.

Another captivating feature of the ocean is its landscape. The majority of our planet is covered by the ocean, which contains underwater caves, mountain ranges, and the deepest known point, the Mariana Trench, estimated to be approximately 11,000 meters deep. While some might find the depths of the ocean intimidating, I find them incredibly inviting. The unknown of the ocean inspires me to learn more.

I love spending time in the ocean, whether swimming or exploring it by boat when I travel. One of my goals in life is to witness bioluminescent shores. These shores have organisms emit bioluminescence, lighting up the waves like a natural glow stick. I’m not entirely sure where they are located, but I plan to do some research because visiting them is on my travel bucket list. Another goal of mine is to go whale watching someday.

This picture shows a group of seals I saw when I visited Prince Edward Island this summer.

This is another picture I took during my trip to England. The location is called Durdle Door, a famous rock formation in the water. Typically, the tide is higher than what’s shown in this image.

Whenever I travel, I always seek out unique ocean landscapes and fascinating species!

Beyond my personal love for the ocean, I’ve also gained valuable insights about nature through this course. I’ve learned that nature can be interpreted in many different ways and impacts our lives far beyond just science. It is deeply woven into art, music, history, and countless other fields. Additionally, nature can be expressed in diverse formats beyond scientific articles or research papers, it can come to life through podcasts, blogs, paintings, and more.

As the semester comes to an end, I’ve been reflecting on what I’ve learned across all my courses. This class has taught me what it takes to be an effective teacher. While I’m passionate about nature and have loved studying it, I’m unsure whether I want to pursue a career directly related to it. However, I do know that I want to pursue a career in teaching. This course has helped me understand the importance of recognizing privilege and connecting with an audience. It has also deepened my excitement for nature and shown me the power of approaching topics from multiple perspectives. Just as with nature, any subject can resonate with people in different ways incorporating various lenses makes learning more meaningful and impactful.

This course has taught me to see nature from multiple perspectives and to engage my audience in a way that fosters excitement about the natural world. This is especially important, as emphasized in this week's textbook reading on lifelong learning. The reading highlights key stages where nature interpretation plays a crucial role preschool, elementary school, and high school. It also underscores the importance of educating others about the nature found in their own residential areas.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bird Migration

Something that has always amazed and inspired me is bird migration. Having studied birds throughout Ontario, I am still amazed every year by the spectacle of bird migration every spring and fall. You could say that bird migration invokes this important sense of wonder as described in the textbook (pg 42; Beck et al., 2018)

Point Pelee National Park, a place I have spent many of the past Mays, is one of the best places in Canada to witness spring migration. Being a long point that sticks out into Lake Erie, this makes it a sort of funnel; the first land tired birds encounter after having flown across the lake coming from Ohio. This funneling effect means that many birds are concentrated in the Park, making them easier to spot by bird-ers and nature enthusiasts. Some mornings can be particularly magical. Birders flock down to the tip every morning, and if conditions are right, you might be able to witness thousands of songbirds streaming in off the lake. As many songbirds are nocturnal migrants, a cold front or a low pressure system bringing rain in the hours near sunrise often create the perfect “fallout” conditions, forcing birds down out of the sky to find shelter. Exhausted songbirds can sometimes be seen hopping around on the beach looking for small insects- I can remember a particular morning where there were 5 Blackburnian Warblers (a brilliant orange and black bird) just hopping around at our feet. During my guided walks, I like to tie in the threat of climate change, mentioning how more frequent and intense storms will negatively impact bird migration, (pg 459; Beck et al., 2018).

Another phenomenon known as “Reverse Migration” is another fascinating thing to witness. For reasons not fully understood, some birds will fly south back over the lake in the hours after sunrise, before turning around and heading back towards land. Sometimes individual birds will do several of these loops; scientists believe that it is likely a way of resetting their sophisticated internal compass, essentially a way for them to catch their bearings. As birds use the moon and the stars to navigate, light pollution from cities and industry can understandably confuse and disorient migrating birds. This is why it is important to turn off lights at night during this time of year. Finding rare birds aka rarities is a favourite pastime of visiting birders, every year a few species that typically live further south will “overshoot” their breeding grounds ending up too far north at Point Pelee. Every year typically a few of these rare species will turn up in the park. Understanding weather patterns is thus crucial to understanding and predicting where and when the birds will show up. This is something I like to talk about when I am leading bird walks- the weather and knowing where and when to get out. To reference Tilden’s Principles of Interpretation, “Any interpretation that does not somehow relate what is being displayed or described to something within the personality or experience of the visitor will be sterile” (pg 84; Beck et al., 2018)

Southerly winds and no precipitation is conducive for a good night of migration in the springtime. Looking at weather radar imaging is another way to track migration- sometimes birds can be so numerous that flying birds will show up as rain on the radar!

A Gray Catbird in the Park

Birders looking at a rare bird (Willow Ptarmigan) at the tip of Point Pelee

References:

Beck, L., Cable, T. T., & Knudson, D. M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage.

0 notes

Text

Hi Olivia,

I like how you said that nature in itself is full of rhythm and harmony. I also agree that it is really important to take the time to slow down and listen and appreciate natural sounds. If I am feeling stressed or down, it is remarkably calming to head outside for a walk and try to focus on particular sounds of nature, whether that be a bird singing, wind rustling through the leaves or the gurgling of a stream. It is well documented that being outside in natural spaces reduces stress, anxiety and has other innumerable health benefits. I am convinced that these benefits stem from listening to the natural rhythms, melodies and orchestras of the natural world. By protecting habitats and environments, we are also protecting/preserving the unique sounds of nature. A world without birdsong for example would be dull. Songbirds add so much nuance and complexity to already incredibly intricate and diverse ecosystems, that losing these songs would irreversibly fragment and disrupt nature’s natural rhythm and harmony. That’s why I think its important that we as humans and conservationists in particular place emphasis on preserving the unique soundscapes of ecosystems.

Unit 7

I believe that music and nature have always been intertwined. As someone who has spent a fair share of time in the outdoors, I have often found myself noticing how much the sounds of nature around me (like the wind in the trees or the flow of water) feel like their own kind of music. I think that nature in itself is full of rhythm and harmony. I have always thought that when we take the time to stop and listen, nature shows us a song that has been there all along. Often times we are just too busy, stressed and preoccupied by life to hear.

The sounds of nature, from birds singing to the sound of rain hitting the ground, all work together to display the collective music of the environment. Nature provides an endless amount of auditory stimuli, which many artists have drawn inspiration from. Beethoven had captured this essence in his composition "Pastoral Symphony", which mimicked the calm and peaceful feel of the countryside. More modern musicians have actually used recordings of natural auditory elements such as wind or rain and woven them into their music. Beyond mimicking natural sounds, music is a way for us to express the emotions that nature brings us. When we're in nature, it isn't just the sights that get to us, but also the feelings they stir up. One might feel reflective, or free when experiencing nature. Often times, music does the same, it can capture emotional highs and lows, giving a voice to the way that nature makes us feel.

One song that takes me back to a natural landscape is one that many of us are familiar with, "Take Me Home, Country Roads" by John Denver. This song instantly reminds me of a summer road trip that I took with my friends last year. We spent days driving through rural areas and passing mountains, it was really special. The song's gentle rhythm seemed to mirror the peaceful landscape that we were driving through.

In conclusion, it is undeniable that music and nature are connected. Sometimes we just need to take a moment to really listen.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 7

Music will always be an integral part of nature for me. As a “birder” who listens to birdsong as part of my job, I can often associate particular habitats and landscapes with the calls and songs of certain bird species. A favourite shrub/grassland site of mine in south Guelph will forever remind me of the “bouncing-ball” accelerating trill of the Field Sparrow and the clear whistling of the Eastern Meadowlark. Mature hardwood forests throughout Ontario are synonymous with the persistent whistled notes “here-I-am, in-the-tree, look up, at-the-top” of the Red-eyed Vireo, and at night these same forests ring with the almost dog-like barking of the Barred Owl “Who-cooks-for-you, Who-cooks-for-you-all”. If I picture a certain favourite place in the province, whether that be the Carolinian Forests of Point Pelee, the Carden Alvar, or the Canadian Shield of central Ontario, birdsong always accompanies these mental images, so much so that each one of these places has a unique suite of song associated with it. From one of our assigned readings this week, the authors make a point about ambient sound, “Ambient sound is a central component of natural habitats. Abstracting the voice of a single creature from a habitat and trying to understand it out of context is a little like trying to comprehend an elephant by examining only a single hair at the tip of its tail (before cloning, of course).” (Gray et al., 2001). I can very much resonate with this statement, it can often be more difficult to contextualize or place a song to a certain species without hearing the other ambient noises, and often the songs of other species found in that same place. Eastern Phoebe’s wheezy “Phoebe-Phoebe” song is very much associated with running water, as they will often nest next to streams for example. As a consumer of human music, I often find myself gravitating to such songs that use nature for its inspiration, whether that be the integration of natural sounds into the music itself or through the use of nature-themed metaphor or imagery. A favourite song of mine as a child from summer camp on Beausoleil island on Georgian Bay is a song that connects me to that special place,

“Within the dark forest, the shadows are falling.

The fire of sunset is gone from the sky.

The daylight is dying; the soft winds are sighing.

The night birds are crying as homeward they fly.

The pale moon looks down from its place in the heavens, Enfolding the island in silvery light.

"Go softly, go softly to rest upon Beausaleil.

God watches your slumber through all the still night."

This song would often be sung towards the end of evening campfire; a lullaby of sorts to send the youngest children off to bed. The tune is simple, and the language is poetic - rhyming with a repeating rhythm. The lyrics illustrate the comforting and beautiful natural scene in that very same time and place, connecting the group with the land and the other creatures who are also ending their day.

References:

Gray, P. M., Krause, B., Jelle Atema, Payne, R., Krumhansl, C., & Baptista, L. (2001). The Music of Nature and the Nature of Music. Science, 291(5501), 52–52. https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?p=AONE&u=guel77241&id=GALE%7CA69270354&v=2.1&it=r&sid=AONE&asid=fb9366a8

0 notes

Text

Blog 6: Importance of History in Nature

This quote highlights the importance of history in the interpretation world. It reminds us that the human experience is shaped by the actions and memories of our past.

From generation to generation, these worldviews, lived experiences, triumphs, tragedies are passed down. Over the course of a couple generations however, the impactfulness and potency of experiences of the past is lost. This is why it is important to catalog and document the experiences of our ancestors. For example, today there is a worrying increase in the number of people who are either deniers of or believe the death toll of the Holocaust was exaggerated. This makes some sense, as there are fewer and fewer survivors of the tragedy alive today to relay and share their stories. This denialism again highlights the importance of remembering past injustices so they are not repeated in the present or future. The quote from our textbook, “It is critical to preserve and interpret memories so those memories can inspire action today” (pg 327;Beck et al., 2018) summarizes this succinctly.

More specifically, the quote for this week’s blog prompt defines integrity. It says that integrity is all about stitching together any parts to a whole, even if the parts are scattered across time and space (Unit 6; Courselink). In essence, it says that practicing integrity and living by core values requires us to understand history. Keeping the memories of past generations alive is thus an important role of all interpreters, including us nature interpreters. By teasing apart the histories of ancient things we can also make these events more accessible and digestible to a wider audience and inspire others to create their own meaningful and impactful histories. Teaching people about species extinctions for example is an important way we can educate our audience about the gravity of climate change and the biodiversity crisis. Through the preservation of stuffed Passenger Pigeons, people are actually able to see tangible evidence of a once abundant bird species that has been extinct for well over a hundred years.

This thus has the capability to “breath life” back into the bird, and helps as our textbook says to nurture the development of our place in the world by using this relic from the past as an important reminder of the power of human destruction (pg 306; Beck et al., 2018). This hopefully should instill important values in today’s generations, ones of preservation, conservation, and living sustainably and not wastefully (pg 306; Beck et al., 2018). The last sentence of this quote from Edward Hyams is reminding us of the power of acknowledging how the past impacts the present. I think of the old adage, “If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” when I read this quote. I think the answer to this question is a resounding yes, even if no human hears the tree fall, its decomposing bark, leaves and wood sustains a whole community of organisms for decades to come.

References:

Beck, L., Cable, T.T., Knudson, D.M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage: For a Better World. Sagamore Publishing LLC. https://sagamore.vitalsource.com/books/9781571678669

First Peek at Empty Skies: The Legacy of the Passenger Pigeon. (2014, August 21). Rom.on.ca. https://www.rom.on.ca/media-centre/blog-post/first-peek-empty-skies-legacy-passenger-pigeon

0 notes

Text

The Significance of the Past

“There is no peculiar merit in ancient things, but there is merit in integrity, and integrity entails the keeping together of the parts of any whole, and if these parts are scattered throughout time, then the maintenance of integrity entails a knowledge, a memory, of ancient things. …. To think, feel or act as though the past is done with, is equivalent to believing that a railway station through which our train has just passed, only existed for as long as our train was in it”. – Edward Hyams, Chapter 7, The Gifts of Interpretation

This quote prompted me to consider how meaning is often tied to context rather than the object itself. At its core, significance is not inherent but rather created through human interpretation. Hyams is right; standing alone, historic elements do not in fact hold any significance. Take these rocks for example:

This photo probably did not spark any type of emotion, inspiration, or interest in you, and considering the dull nature of this photo, it’s understandable—I mean, it’s just rocks. Now, what if I told you about their history? These ordinary rocks actually used to lie on the Moon, and were brought to Earth during the Apollo 11 mission in 1969—the first mission to land humans on the moon. These rocks represent humanity’s first steps onto another celestial body, and the profound scientific and political changes that space exploration has since brought about. Now, looking at these rocks, you probably feel a little something more than you originally did—instead of mere confusion about why I’m having you look at rocks.

The significance of historic elements lies in our ability to interpret those ancient things, ultimately aiming to understand the impact of the past on our lives in the present. In his quote, Hyams is suggesting that integrity is not merely about moral honesty, but about maintaining the coherence of a whole across time. He implies that ignoring the past severs the connections that shape identity, meaning, and community. Take the moon rocks as an example; without their story, they are just pieces of stone, but with it, they become tangible links to one of humanity’s greatest achievements.

The analogy of the railway station in Hyams’ quote illustrates the dangers of historical amnesia. To assume that the past is obsolete once we move beyond it is to misunderstand the continuity of time. Interpretation ensures that historical connections remain visible, guiding understanding and action (Beck et al., 2018). In our modern era, where human influence continues to drive constant change, this idea holds particular significance. Human development reshapes landscapes, often erasing historical markers in the process, and when places lose their stories, they risk losing their significance (Beck et al., 2018). To bridge this gap, interpretive writing and historical interpretation are essential to connect lived experiences with archival records and artifacts (Beck et al., 2018).

A significant example of an effective writer is Rachel Carson. A biologist and nature writer, Carson is best known for her 1962 book Silent Spring, which exposed the dangers of widespread pesticide use and its unintended consequences on the environment.

Rachel Carson and her book: Silent Spring

Carson’s strength lay not only in her scientific accuracy, but in her ability to translate her findings into a narrative that captured public attention. Silent Spring did not just present facts—it wove them into a cautionary tale about humanity’s impact on nature, leading to real-world environmental reforms. Effective writing, like Carson’s, is crucial in interpretation because it has the power to transform information into something that resonates with the public and inspires change (Beck et al., 2018).

History’s significance is shaped through interpretation. Whether through oral storytelling, written interpretation, or historical preservation, we maintain integrity by keeping the parts of the whole together. As Hyams suggests, to disregard the past is to sever our connection to it. But, to remember, interpret, and share, is to keep its lessons alive and inform the choices we make for a better future.

References

Beck, L., Cable, T.T., Knudson, D.M. (2018). Interpreting Cultural and Natural Heritage: For a Better World. Sagamore Publishing LLC. https://sagamore.vitalsource.com/books/9781571678669

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 5

For this free blog post, I thought I would discuss the importance of environmental literacy and how science today is failing the planet and the next generation of humans. First, the article in Science succinctly summarizes one of the key problems science is facing in today’s fraught political and environmental climate, that is the divergence of Science Education and Environmental Education (Wals et al., 2014). The authors suggest that this divergence is because science education emphasizes the advancement of capitalistic values, that of mass production and innovation to remain competitive (Wals et al., 2014). On the flip side, environmental education is still taken less seriously than Science Education and is perceived negatively. People think of hippies, the anti-war movement and dare I say socialism when they think about the environmental movement and environmental education in general. Thankfully, I think that today those narratives are slowly being unravelled. While the threat of climate change is forcing people to think twice about how the impacts their actions have on the planet, unfortunately, there are many simple things which counteract emissions that are not being done. In essence, common “environmental sense” is still lacking in many people, particularly those who live in higher-income countries such as Canada and the US. Take for example, lawns. For years we have understood that monocultures are biodiversity killers, having devastating impacts on the organisms that are important pollinators. Second, the water use that goes into maintaining lawns is astronomical. I personally cringe in late summer, after a prolonged dry period with little rain, when I see people watering their green lawns; a lawn which does nothing for the environment and only brings a feeling of pride to whoever is doing the watering.

I am super interested in understanding why people derive joy, satisfaction or pride from growing this crop that provides virtually zero ecosystem services. This is baffling to me- why are lawns still a thing??!! I think it partially has to do with a lack of effective science education and a nonsensical division between “science” and environmental stewardship. This story, I believe points to how science has become highly politicized, and how it is still believed to be only an activity that elites can contribute to and participate in. It also points to the growing phenomenon known as “Nature Deficit Disorder”, where increasingly children are spending less time out in nature and speaks to the fact that the majority of people living on the planet have very little environmental literacy (Fewer Children than Ever Know the Names for Plants and Animals, 2019). What’s scary to me is that children can more readily identify brand logos than images of native species found where they live. If we are to combat the biodiversity loss, how do we go about doing that if people cannot identify the flora and fauna that need to be protected? I think a radical rethinking of societal values and norms, and possibly mandated time in nature is required for school-aged children if we are to survive as a species beyond the next couple hundred years.

Fewer children than ever know the names for plants and animals. (2019, September 10). World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2019/09/children-are-forgetting-the-names-for-plants-and-animals/

Wals, A. E. J., Brody, M., Dillon, J., & Stevenson, R. B. (2014). Convergence Between Science and Environmental Education. Science, 344(6184), 583–584. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1250515

0 notes

Text

Blog Post 5 - Crash Course!

As we are free to write about whatever is on our mind this week, I will swiftly take this chance to talk about my own personal interests within environmental science. Hopefully this post will teach you something new, and also allow you all - as my classmates - to get to know me better. If you have ever met me in person, you have certainly had the pleasure of witnessing me drone on and on about soil science, or insects, and just because we are in a DE class does not mean any of you are exempt from this!

Crash Course - Soil Science and Agriculture.

For those of you who are not familiar, the study of soils science can be best described as an interdisciplinary cross between geology, toxicology, geography, plant biology, and land management. I love soil science because soil is a product of its environment, you get to understand exactly why soil formed a certain way based on where it’s located, what plants and animals live in that location, what the bedrock geology is like, and any other historical weather events and/or land use it has been though. It’s like solving a puzzle to understand how to best move forward. Studying soil science is incredibly important because soil is the medium the majority of our food is grown in! Did you know that our current food production would drop by at least a third if it were not for fertilizers? Knowing the correct ways to manage our agricultural soils is critical for minimizing excess nutrient runoff - both for environmental and economical reasons. Soil science and how it intersects with biology, biodiversity, toxicology, and practical skills is what makes it an endlessly fascinating subject for me. I have made my friends through this interest, and have had the privilege of studying in the field with some of my favourite people!

Crash Course - Insect Biodiversity

Another long lasting interest of mine has been insects. I feel as though many people gravitate towards insects because they’re simply all around us! This semester I have had the pleasure of being in the ENVS*3090 course taught by Dr.Andrew Young. This course offers many hands-on opportunities for examining different insect specimens in our lab time. Getting the chance to look at insect specimens under a microscope, and see the small details that make each species special and unique has been nothing but joyful for me. You might be asking, what's the big deal about bugs? I don't just enjoy studying insects because they are pretty or interesting, insects have a massive relevance in the environment that is worth studying. The obvious example is that of pollinators, I don't feel as though I have to explain why pollinators are important. Aside from their positive interactions with humans, insects are major carriers/transmitters of disease, and invasive species can bring massive devastation to our ecosystems. In addition, as with anything these days, insects are majorly affected by climate change, with many species moving northwards as our earth warms.

I hope this post helped spark a new interest in you, or just simply helped to get to know me better. I’d love for you all to reply to this post by giving me a crash course of some of your favorite subjects to study!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Using Art in Nature Interpretation

I am a big believer in the power of the arts. I have always been inspired by the beauty of nature to create my art pieces. When I create my art pieces, or stop to take a picture, it is because the scene before me has instilled this sense of wonder and appreciation. Through my art, I am attempting to capture that feeling of connection, with the hopes of sharing it with others to provide that same feeling.

Image 1: A sketch of a trumpeter swan (Cygnus buccinator), made in 2018, by Zoe Land

However, I am aware that there is bias when it comes to artistic expression, like in paintings or photographs of nature. I am often drawn to ones that capture a moment of stillness and “untouched beauty”, but this is not always the reality of what nature is. In this CBC article, Matteo Cimellaro challenges some of the group of seven work, and the Canadian identity, which I found interesting to reflect on (2022). The iconic canadian landscapes which have become so popular, are lacking the inclusion of indigenous peoples who have always traditionally used those lands; particularly the Anishinabewaki, and the Omàmìwininìwag who’s territories Algonquin Park resides on (https://native-land.ca/). The perspectives of the settler art pieces are important to consider, and only portrait one person's view.

Photo 2: The West Wind, 1916-17, Tom Thomson, OIl on canvas. https://ago.ca/collection/object/784

When presenting art as an interpreter, it is important to think about what the message is, and what can be learned from the art piece. For the group of seven works, this ‘idealized nature’ concept might be important to acknowledge. For my own art interpretations and presentations, I would like to provide a disclaimer that these photos/sketches/paintings are through my own settler lens.

Art is such an important and excellent way of sharing knowledge with others, as it can present complex information in creative ways which may help people process and remember more. When Freeman Tilden was talking about “the gift of beauty”, I perceived that as being able to use the arts in a way that can inspire people, and create a sense of wonder and awe about the topic you are sharing. Whether it is through poetry, dance, music or sculpture, these creative expressions are some of the best ways to communicate emotion. This invoking of emotion I think is vital for helping inspire others to become curious, and create deeper connections with the world around them.

Some of my favourite programs I have experienced have been through the expression of art. I love film, and while I was working at the Heritage Centre on Saturna, there was a special viewing of the Planet Earth footage of the garter snakes (Thamnophis elegans) on the island. It was breathtaking to see this beautiful, up close footage of this amazing animal that normally would not be paid close attention to. The best part was seeing the emotion that this footage created in the crowd, and how the whole community got to bond over this moment. After that event, I would have more visitors coming into the museum and ask me questions about the garter snakes! I am glad that people came to appreciate them more, as I also did.

Photo #: Western Terrestrial Garter Snake eating a gunnel. Screenshot taken of the BBC Planet Earth Film from: https://simres.ca/seatalk-home/western-garter-snakes/

As an artist, it is my hope to be able to capture powerful moments in nature that I stumble across. It know it can be a difficult job to decide what medium would be best to re-create and share the moment with other people. However, I think if you are able to collaborate with other artists and visitors, and receive feedback for your ideas, using art can be a very effective way of interpretation.

Work Cited:

Cimellaro, A. (2022) Let's liberate the Canadian landscape from the Group of Seven and their nationalist mythmaking. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/arts/let-s-liberate-the-canadian-landscape-from-the-group-of-seven-and-their-nationalist-mythmaking-1.6410676

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 4: Who are you to interpret nature through art? How do you interpret “the gift of beauty”?

As someone who dabbles in photography, art is an important way I interpret the natural world and communicate my lived experiences. I was introduced to works done by the Group of Seven through a visit to the McMichael Art gallery when I was around 10. Having travelled to some of the areas in which the artists’ drew their inspiration- places like Algonquin Park and the north shore of Lake Superior, I could resonate with many of their works (Unit 4, Courselink). The stylized and dramatic landscapes evoked a longing to travel back to these beautiful places. These paintings also helped shape my perception of “Canadian wilderness” and reenforced my own sense of belonging in these spaces and fostered a feeling of wonderment. A favourite winter-time trip when I was between 10-15 was spending a few days in Algonquin Park with my parents. It was a quiet time to visit the park, when there were few tourists and hikers. Here I gained a deep appreciation for Boreal landscapes and the charismatic animal inhabitants like the Pine Marten and colourful birds like the Evening Grosbeak and White-winged Crossbill. Inspired by some of the amazing landscapes captured by the Group of Seven, I decided to take some landscape photos of my own during a visit in 2016 when I was 14:

Looking across Spruce Bog

This experience was meaningful, and it inspired me to keep travelling in search of more beautiful places I had seen photos of in books or read about online. Many of my favourite landscape shots have the power of taking me back to that moment; often evoking feelings of happiness and belonging on top of that nostalgia.

Before the storm- Dinosaur Provincial Park; Alberta

Grey River; Newfoundland

Thus, my enjoyment of these paintings helped instill “The gift of beauty” (pg 85; Beck et al., 2018. As stated in the textbook, the gift of beauty should also help to highlight the importance of “resource conservation”. I choose to interpret this in the context of habitat and biodiversity conservation. I have been very fortunate to travel to some remote wilderness areas during volunteer trips and for work. This travel inspired me to create my own little interpretive photo journal/blog on Instagram. Here, I showcase photos of the wildlife and the landscapes I encountered in these places. I try to communicate interesting and little-known facts about the animals I saw and the habitats they live in in these posts. My overarching message is always one of conservation; highlighting the need to protect these spaces so future generations can visit these places and have similarly meaningful experiences and wildlife encounters. Thus, through the medium, I hope to trigger my audience’s senses both emotionally and intellectually (Unit 4, Courselink). Furthermore, I also hope to encourage other wildlife and travel enthusiasts to step out of their comfort zones and volunteer in remote places like I did, as these immersive experiences have proven super impactful for me, inspiring me to pursue a job in the conservation field.

The world’s smallest shorebird (Least Sandpiper) in a garden of tundra wildflowers- Hudson Bay coast; Ontario

A Polar Bear “cooling hole” and sunset over the Hudson Bay coast; Ontario

Smith’s Longspur- Hudson Bay coast; Ontario

See the caption for this photo I wrote last year below.

One of the continents' most enigmatic bird species; due to a small population, limited range, and a proclivity for grassy tundra expanses in remote and inaccessible regions, much of the Smith's Longspur's life history was shrouded in mystery until recently. Through studies, it has been revealed that this secretive small orange songbird just might have one of the most complex and fascinating breeding biologies of any bird in North America. First off, Smith's Longspurs are polygynandrous. This is the rarest mating strategy observed in birds; only well documented in three other passerines- Eurasia's Alpine Accentor and Dunnock, and the Hihi (Stitchbird) of New Zealand's north island. In the majority of bird species, one male pairs with one female and the two share the responsibilities that come with raising young. In birds that practice polygynandry, things are done quite differently. Each female and male Smith's Longspur typically has 2-3 partners in a given breeding season. Females form a brief (3-7 day) pair bond with a male in which they copulate and he guards her from other males. Females will then move on to another male, and males onto another female where the process is repeated once or twice more. This results in females having clutches of eggs that are sired by multiple males. During incubation, the first (primary male) typically guards and chases away intruders right before the first egg is laid, where the secondary male performs these duties on the day the third egg is laid. Once eggs are hatched the young are always fed by the female, and usually multiple males! Over the course of a week in the peak breeding time, a female will typically copulate 350-365 times, which is one of the highest rates of copulation in any bird! To keep up with all this mating, males have large testes and larger cloacal protuberances. In fact, males' testes takes up 4.2% of body mass vs only 2.0% in their congener, the Lapland Longspur. (wkonze_photography;Instagram)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi Rachel, neat post!

I too am frustrated at the lack of commitment made by western science to learn from and integrate indigenous knowledge into their research. When you talk about how privilege dictates which knowledge and perspectives are amplified, I think you’ve really hit the nail on the head. For the longest time western science as a discipline has ignored indigenous knowledge; labelling the discipline as pseudoscience. This exclusionary approach only serves to further marginalize and alienate their communities, and makes them feel unwelcome in the academic research space. Integrating indigenous knowledge and western science through “Two-eyed Seeing” (the term was coined by Mi’kmaq elders Albert, and Murdena Marshall) (Wright et al., 2019) might be a way to mend this damage and make western science a more holistic (as you put it) and accessible discipline. The goals of this way of thinking is simple; if indigenous as well as western ‘ways of knowing’ are included in curriculum, this should encourage indigenous students to bring their cultural knowledge to the table; thus making them more engaged and more likely to enter academia (Wright et al., 2019). I think having more of these varied perspectives in environmental science will only serve to strengthen the discipline!

Also wanted to add briefly that I saw Joseph Pitawanakwat speak last year- he was giving a talk about his journey to catalog and document indigenous names for Ontraio’s native bird species- was a great talk!

Wright, A. L., Gabel, C., Ballantyne, M., Jack, S. M., & Wahoush, O. (2019). Using Two-Eyed Seeing in Research With Indigenous People: An Integrative Review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919869695

Blog 3: Privilege in Nature Interpretation

After reading the content in unit 3, I think of privilege as the advantages or benefits afforded to individuals or groups based on characteristics such as race, gender, or socioeconomic status. These advantages often shape one’s experiences and opportunities, not from their abilities, competencies, decisions, or actions but rather from their position or social identity. In the context of nature interpretation, privilege may impact who has access to natural spaces and education, whose stories are told, and how these stories are framed.

Nature interpreters often reflect the dominant culture’s perspectives, privileging certain voices over others. For example, Indigenous peoples often find their knowledge overshadowed by Western scientific narratives. Privilege influences which stories are amplified, and this may result in a misrepresented interpretation of historic and cultural relationships with nature.

I have experienced this firsthand as a Wildlife Biology and Conservation major, where most classes focus solely on technical aspects and new research. While these are important, they often fail to incorporate Indigenous perspectives and knowledge. Why would this be important? I think incorporating Indigenous knowledge is essential for fostering a more holistic understanding of ecosystems, ensuring that our education is inclusive, teaches us about the history of our land, and is respectful of traditional ecological wisdom.

I worked at the Royal Botanical Gardens in Burlington, Ontario for two summers as a visitor experience representative. I had the privilege of having access to all the gardens, trails and visitor centres within the property. One of my favourite trails is called “Enji naagdowing Anishinaabe waadiziwin”, which translates to “The Journey to Anishinaabe Knowledge”. This trail, developed in partnership with the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, invites hikers to explore the connections between plants and Anishinaabe culture. Informative signs placed along the trail provide insight into how the Anishinaabe people traditionally used various plants for medicine, food, and cultural practices.

I admire the RBG’s commitment to incorporating Indigenous history, stories and ways of living into their interpretation. This approach goes beyond simply showcasing the beauty of the area, it helps to give a voice to the often overshadowed Indigenous peoples, and a meaningful platform for their important stories to be told.

The RBG website captures this idea by sharing the words of Joseph Pitawanakwat, a plant educator from Wikwemikong Unceded Nation:

“In my Anishinaabe culture and tradition, we teach that every plant is telling you a story, and in that story, the plant is teaching why it is here, its purpose — all we have to do is listen... Scientists are also testing Indigenous medicine plants and discovering active compounds that legitimize their use. As you walk this trail, you’ll see examples of how this works, some easy to spot, and some hidden in the plants.”

This quote highlights the importance of listening to not only plants, but also the wisdom of Indigenous communities, in order to deepen our understanding of the natural world and progress modern science.

Recognizing privilege in nature interpretation is important for ensuring equitable and accessible education for all. I encourage readers to reflect and answer the question: How can you actively work to dismantle privilege and ensure an equal platform for all in your nature interpretation career?

Royal Botanical Gardens. (n.d.). Indigenous plant medicines trail. Retrieved January 21, 2025, from https://www.rbg.ca/gardens-trails/by-attraction/trails/indigenous-trail/

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

What role does “privilege” play in nature interpretation? Please include your working definition of privilege.

Privilege is something that you may not realize benefits you, but is nonetheless still present; it is something that gives you an advantage over your peers, often as a result of your upbringing. My relationship with nature, for example, is one that has been shaped immensely by privilege, even though I sometimes forget to acknowledge it. I am a white male from a middle-class family. Growing up my parents valued being outdoors in nature. From road trips across the province to look for unique wildlife, to camping trips in the summertime, to visiting a boat-access only cottage multiple times per year in Muskoka, I have only had these positive and impactful experiences because of my privilege.

These experiences all fall in my “invisible backpack” and this course, and others are helping me to get better at unpacking and acknowledging this privilege. This privilege is probably most evident when I think about the demographics of the people who have similar hobbies to me. The naturalist and the birdwatching community in general are not diverse, and white folks make up a disproportionate number of the nature enthusiasts I encounter while outdoors. I must also add, that not so long ago, (the early 1990s in one instance) certain ornithological clubs in Ontario only offered memberships to men! The outdoor spaces I choose to spend in are most frequently visited by people, who like me, have binoculars, a camera, in some cases a spotting-scope, and of course access to a vehicle for transportation. Visitors to National and Provincial parks are similarly disproportionately visited by white people and especially people of higher socio-economic status. My experience working as a bird-guide at Point Pelee National Park has informed this observation. While there are many people of colour who visit the park from the local community of Leamington, I have noticed that they are less likely to attend guided walks and are less likely to engage with interpretive programming put on by the park. As minority groups, statistically speaking, are more likely to face economic barriers which prevent them from attending interpretive events (pg 133; Beck et al., 2018), this tells me that as Canadians and as nature enthusiasts we still have a long way to go to make nature an accessible, safe space for all.

Thankfully, the birding community at large is taking big steps forwards to becoming more inclusive and diverse. In the past couple years there have been efforts made to reduce barriers to marginalized communities through inclusion (pg 134; Beck et al., 2018) These include “Birding with Pride” walks led by LGBTQ members of the community, and a week in May called “Black Birders Week”, where black naturalists/scientists and nature lovers are celebrated and given a platform to share their experiences with nature. Additionally, there have been collective efforts made to donate equipment like binoculars and scopes to people who don’t have such items themselves. As a result of these actions and campaigns, I have seen the community grow and develop, and while there is still much work left to be done, I believe the community has benefitted greatly from the addition of diverse voices and perspectives.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hi Olesia, great post; I really enjoyed reading it!

Like you have argued here, I also believe that experiential learning is one of the most impactful ways in which interpreters can engage with their audience. The best way to learn and develop appreciation for nature and the outdoors in general is through these immersive experiences- being out in nature is inherently immersive after all. I think taking this approach to interpretation is crucial if we are to make nature (and science) more accessible for all, in particular kids and those without a scientific background. You also discuss developing a strong scientific skillset to help educate those about the importance of appreciating and preserving the natural world. With climate science becoming more and more polarized and divisive in this age of misinformation, communicating the facts about climate change and the biodiversity crisis effectively, while still leaving room for optimism and those “good news stories” is so important. I think unfortunately there is a real lack of effective communicators in the climate-science world. I feel that increasingly, people without a strong scientific background struggle to find resources which communicate the science in a manner that is easily understandable. Too often these people are turning to unreputable sources because they cannot make sense of all the technical terminology found in the bulk of the peer-reviewed journals! To combat this disconnect between scientists and non-scientists, passionate and enthusiastic nature interpreters are very badly needed. Thanks for the interesting and hopeful read and giving me much to think about,

William

Blog #2: My Ideal Role as an Environmental Interpreter

My ideal role as an environmental interpreter would focus on fostering deep, meaningful connections between people and the natural world through hands-on, interactive, and visually engaging experiences. I picture working in a setting such as a national park or wildlife refuge.

As an environmental interpreter, I would focus on developing and leading immersive, tailored programs that encourage active participation and curiosity. These could include guided hikes where participants learn to identify native plants and animals, interactive workshops on sustainable practices like composting or reducing waste, and wildlife observation tours that teach visitors how to respectfully observe and appreciate natural ecosystems. One of the most important messages I could convey in this role is the critical need to respect and protect wildlife by minimizing human interference. Observing animals in their natural habitats is a privilege, and I would emphasize how even small actions—such as feeding animals, getting too close, or leaving trash—can disrupt their behaviors, harm their health, and negatively impact ecosystems

Because I am a hands-on and visual learner, I would strive to design programs that cater to similar learning styles, emphasizing experiential learning. For example, visitors could engage in activities that involve hands-on conservation efforts, like participating in activities like planting native species or monitoring wildlife populations.

Beyond in-person programs, I would create educational materials that extend the learning experience. Interpretive signs along trails could tell the story of local ecosystems, visually appealing brochures could highlight conservation tips, and virtual tours or online content could make nature accessible to a wider audience.

Recognizing that not everyone has physical access to nature reserves or parks, I would also prioritize creating virtual tours and educational content to reach those who are unable to visit in person. These virtual experiences would allow individuals from all walks of life, including those with physical disabilities or living in urban areas, to explore ecosystems and learn about wildlife conservation. Virtual tours could simulate guided hikes through forests or coastal habitats, where users could explore and learn at their own pace. Additionally, educational resources such as virtual workshops on sustainability practices or wildlife tracking would allow a broader audience to participate in environmental education. These initiatives would also promote global awareness and appreciation for the natural world, ensuring that environmental education is inclusive and accessible to all. The perfect setting for this role would be an area rich in biodiversity and offering a variety of ecosystems to explore. Areas where I would be able to showcase different habitats and how they connect, like the Pacific Northwest.

To thrive in this role, I would need a variety of skills that align with my passion for hands-on and visual learning. Strong communication would be beneficial, especially when it comes to explaining complex ecological concepts in engaging ways for a diverse audience. I would also need a strong expertise in environmental science among other skills.

Ultimately, my goal as an environmental interpreter would be to inspire a lifelong appreciation for nature by creating programs that are interactive, visually engaging, informative, educational, and rooted in hands-on experiences. I believe that by fostering a sense of responsibility, it can create a lasting difference in how people view and care for the natural world.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog 2: Describe your ideal role of environmental interpreter. What might it entail? Where might it be? What skills might you need?