Text

A Reylo Retrospective (or: The Friends We Made Along the Way?)

After a New York City SNL weekend, I typically write a flaily recap of the incredible show experience on my way home. (See my unabashedly joyous recap posts from Adam’s 2018 and 2020 shows. :)) My friends and I sadly did not make it into the show this time, so I decided to write a recap post of a different kind. This is a retrospective of my years in Reylo/Adam fandom so far, and why they’ve been the best years of my life.

In December 2017, I saw TLJ in theaters for the first time. Like many of you reading this, my life was irrevocably changed in the span of those hours. We all remember the moment when we felt it happen. Maybe it was when Kylo took off his helmet in front of Snoke and bared those wounded eyes. Maybe it was the moment when all sound cut out and the first force bond opened. Maybe it was the moment Kylo appeared shirtless - hot and broad and so so vulnerable. Maybe (as it was for me) it was the moment when he and Rey locked eyes in the throne room, then turned back to back in a slow motion, world-tilting moment that changed everything. Without fail, this is always one of my favorite things to talk about with Reylo friends both new and old. Recalling the moment. That lightning strike of realization that you were seeing something that would indelibly change who you are.

It’s impossible to describe the experience to people who didn’t share in this particular epiphany. But whenever I attempt to do so, I usually phrase it something like this: When I say TLJ changed my life, I don’t just mean the movie itself. I mean that moment was a gateway. It connected me to a community, friendships, and experiences that would beautify and enrich my life in ways I could never have expected.

In June of 2018, I made a hare-brained trip to the Nantucket Film Festival, where Adam would be speaking on a panel with Noah. The event was small, located in a humble school auditorium. I sat in one of the first rows, mere seats away from Greta and Joanne. Adam came onto the stage, and he was everything and nothing I expected. Larger than life. Impossibly small compared to the explosive impact of his presence. An unassuming, compelling, inexplicable force that made my heart race and my stomach swoop. The impact of his presence is something I still can’t describe. This riveting, authentic persona; this irresistible gravity in the way he carries himself; the way he seems to hunch into a body that nonetheless strains the seams of the world around him. I couldn’t take my eyes off him the entire time, and my heart never calmed down. To this day, it still hasn’t.

Then came September of 2018: Adam’s second SNL appearance and what would be my first time attempting to go to the show. In the week leading up to the show, the undertaking truly gave the impression of insanity. I took an overnight bus to NYC on a Thursday night, and upon my arrival at 5 AM I went straight to join the Standby Line with my humongous backpack and all my things in tow. It was still dark, raining, and I truly contemplated my own sanity as I dug trash bags out from my backpack and bagged all my things in effort to keep everything dry. Then the sun rose, the rain petered out, the one internet friend I’d planned to meet there joined me in line, and as the Friday hours flew by, solidarity and excitement warmed the steadily-growing line.

When I think back to those ~24 hours of mania, I remember spontaneous pizza parties with new line friends; I remember spirited conversations in the midnight hours about Adam’s filmography and all our respective moments of epiphany that led to us being there - on a NYC street at midnight for a mere chance of watching our collective fave on SNL. I remember random Reylos watching our updates on twitter and sending us food, snacks, and Starbucks in line. (Literally never forget the bike delivery guy who, with a befuddled expression, announced he had a pizza delivery for “….the Reylos in the SNL line???”) I remember the camaraderie, the utter silliness, the crafting of homemade signs so the hundreds of passers-by would stop asking what we were there for. (Ours said ‘What: Saturday Night Live. Why: Kylo Ren.”) I remember the hours flying by, and the utter euphoria of it all - enough to keep us (mostly) warm in even the smallest hours of Saturday morning.

In the show’s Dress Rehearsal the next evening, I sat with three girls I’d never met before that weekend. They’re still three of my best friends to this day. We exchanged numbers after the show that evening and started a group chat (“Designated Adam Drivers,” obviously). In the five years since, every single day that group chat lit up my phone meant it would be a good day. In the years since then, we’ve shared countless experiences that would never have even knocked on my door of possibility, were it not for this miraculous thing called the Reylo/Adam gateway - that spark of recognition and understanding that turned us from strangers to soulmates.

Since then, we’ve shared almost an embarrassment of riches in terms of experiences together: Four in-person (one virtual) AITAF shows, five Burn This performances/stage doors, the profound highs and lows of the TROS London premiere, Adam’s January 2020 SNL show, Steven Colbert and Seth Meyers appearances, and an array of film festival premieres. (TIFF 2019 for Marriage Story and The Report; Cannes 2021 for Annette; Venice 2022 for White Noise.) Not to mention that last year I went to visit one of those 2018 SNL besties in Australia (along with the other Aussie bestie I met in the 2020 SNL line).

I realize the above list reflects privilege in terms of my opportunities and work flexibility to travel, and that someone could read the above and think I need to chill the fuck out. But I wrote out that list in attempt to convey the broadening of horizons, the ageless delight, and inexhaustible joy that such a shared passion brings into one’s life. It’s a bright beacon of the kind of excitement most people leave behind in childhood. It’s a reminder of the intangible sources of wonder and inspiration that come from within. It brings together people of disparate ages, backgrounds, and nationalities with a kind of innocent enthusiasm it often feels this world needs so much more of.

Of course, one could always argue this common binding spark is the foundation of fandom culture in general. But I’ve cycled through my fair share of other fandoms pre-Reylo/Adam, and nothing has ever compared to these wondrous heights. And going on six years since my personal TLJ moment, I still feel the conviction in my very toes that nothing else ever will.

In parallel to my real-life adventure squad, these last few years have also seen the cultivation of friendships with other Reylos and fic authors online. Never underestimate the power of a single AO3 comment or twitter DM to spark profound connection. What started as a group of online friends quickly transcended the bounds of cyber space. My “pocket friends” don’t just live in my phone; they’re the people I look forward to telling about my day, the ones I lean on in tough times, the ones whose support and love I know to be constant, no matter physical distance or timezones. They’ve become the indefatigable group of girlfriends my teenaged self might have dreamed up to feature in my adult life. And even as some of us may move on from Reylo/Star Wars, its ties are timeless and unbreakable. We are more than a group of people who cohabitated the same particular corner of the internet for a time. No, we’re kindred spirits who recognized in each other the same values, the same challenges and struggles, the same fears and anxieties, the same hopes and joys. We recognized and nurtured in each other that rare, safe space for our true selves. We were drawn together by this silly, fantastic shared obsession, and together built something real and true that grew well beyond it.

So why am I writing this terribly sappy and self-indulgent post, you wonder? Well, I suppose my motivation came from the bittersweet experience of this weekend. I suppose it came from the conflicted emotional response I had to not making SNL this time. It came from the moment I realized that while the disappointment felt crushing, I will nonetheless cherish this SNL weekend right alongside the others.

And why should that mean anything to you, dear reader? Why should you care about my sentimentality? Perhaps because - even if we’ve never spoken either in person or online - we each shared the moment, at one point or another. The moment that led us here - to me writing, you reading, to us sharing this particular little corner of the world. Perhaps because the highs and lows I experienced this weekend are not unlike the wins and losses we all share in this fandom space. The point of this post is not to wallow in temporary disappointment, but to celebrate how far we’ve come in this shared journey. The point is to cut through the haze and the frustration, the scandal and the hurt, to recall the purity of that shared emotion that first called us here. The point is to dedicate a moment of reflection for the love and enthusiasm that guided and shaped all this in the first place.

To many, Reylo is divisive, even maligned. Nothing we say or do can ever change their warped view. We can, however, know in our heart of hearts that we share something unique and powerful. We can support and love each other; we can see the best in each other. We can fill our shared corner of the world with that magic we each discovered when we stepped through that gateway for the very first time.

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I have such great memories from seeing this film at the Venice Festival - so glad it’s on Netflix now and I can revisit it whenever I want! :DD

White Noise (2022)

#The way he adjusts his glasses with his hand UNDER his robe#He's the biggest weirdo ever exist and I love him to bits#White Noise#Adam Driver

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

is your comfort character also a sad pretty boy with trauma and questionable morals or are you normal

32K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy Birthday Colin Morgan! (1st January 1986)

442 notes

·

View notes

Text

Little Dove | Chapter 1/3

As a small girl, Rey frees the demon her grandfather had trapped in the cellar. He watches over her as she grows, destroying all who would harm her and denying his own yearning. Rey wants none but him.

It required no spell, no prayer, no exorcism to silence the devil on this day, to render him quiet and docile. It took only a kiss from the mortal girl who loves him. A small, vast act – an everyday, singular type of salvation.

CHAPTER 1

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I’m being torn apart. I want to be free of this pain. I know what I have to do but I don’t know if I have the strength to do it.

578 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ADAM DRIVER

Promo for Saturday Night Live, 2018

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

AITAF’s 2022 Broadway Show

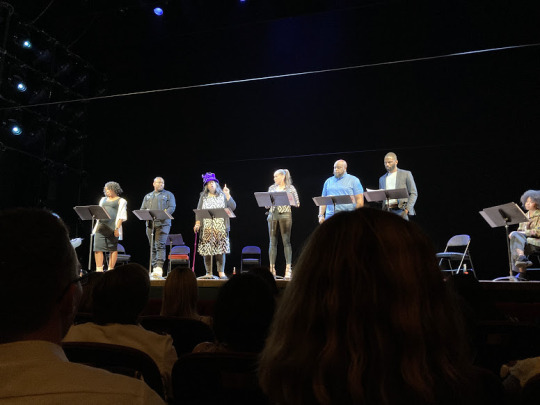

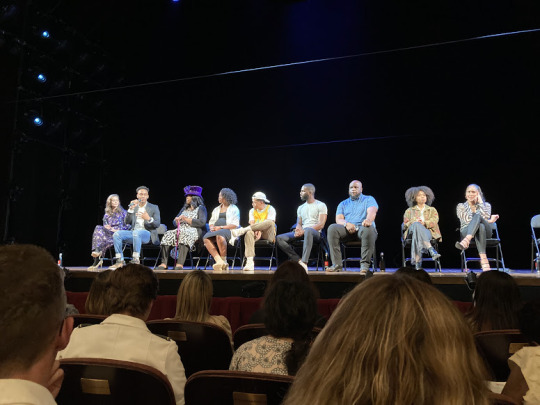

I’ll start by stating what we all know: Without fail, every AITAF show proves to be a profoundly moving experience in one way or another. Whether it’s the reading itself, the talk back afterwards, or simply the atmosphere and sense of connection filling the theater, these nights are always to be remembered. Even speaking as a theater devotee who sees live performances on the regular, AITAF always elevates the experience by emphasizing the collective, community-building nature inherent to the act of performing and watching a play. At heart, AITAF’s mission is to break down barriers: not only barriers between military and civilian viewers in the audience who all find themselves sharing an emotional experience on the same terms; but between military individuals in the audience and the artists on stage as well. To me, this is what makes the AITAF experience truly singular – staying in your seat after the performance concludes, as you watch the invisible boundary between stage and audience dissolve through dialogue and communion.

More than any year prior (at least the four years I’ve attended), this 2022 show highlighted how bold and daring this mission truly is. Putting actors and military personnel in the same room to have a chat and feel some feels together was always something of a radical idea, but this year’s event took the concept so much further. While this was not the first time the Broadway event featured an all-black cast (see my recap of the 2019 performance of A Raisin In The Sun), Fat Ham raised the bar with a veritable celebration of queerness, blackness, and all manner of ‘other’-ness. One of the play’s emotional peaks takes place between Juicy (the Hamlet equivalent) and Larry (the Laertes equivalent, portrayed here as a military recruit home on leave). After several interactions showing Larry to harbor feelings for Juicy, Larry finally makes an utterly beautiful yet tormented confession of love, voicing his profound admiration and envy for all the ways Juicy is “soft” in not letting the world harden him or the dictates of others change him. It’s no exaggeration to say this was one of the single most stirring, gorgeous monologues I can remember hearing in a long time.

The play proceeds to confrontation, then eventual acceptance among the older family members of the younger generation’s difference – difference in not only their sexuality but their evolving expectations and dreams for their futures. Juicy’s uncle (the Claudius equivalent) dies when he chokes on a bite of meat and refuses help from his gay stepson – releasing Juicy from his dilemma of whether or not to revenge his father’s murder and passing judgment on the man’s violent tendencies and homophobic predisposition. In the final scene, the remaining characters briefly contemplate the absurd proposal of killing each other in order to stay true to their tragic source material. Instead, they embrace love and a new tomorrow beyond cycles of violence and revenge. The last thing we see is Larry leading a joyous and utterly fierce dance of liberation, disco music and all.

Fat Ham is the sort of brilliantly irreverent, gloriously life-affirming show you have to see to believe. But just based on what I’ve shared above, you can probably understand why this was such a bold, unexpected choice of work to present to a military audience. Broadly speaking, this is the demographic people might expect to vote red and react with discomfort to such intimate examinations of black, queer, and transgender consciousness. But by the end of the night, it became clear that, actually, there is no audience better suited for such a story.

As the talkback began, an immediate connection was apparent between material and audience. A question was posed about the former ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ policy, and the audience member expressed how rare it is to see portrayals of LGBTQ people in uniform. The one bordering-awkward moment came when an older woman in the audience asked the cast (and Director, also present on stage) whether they believed this depiction of a multi-generational family to be realistic - wherein the younger generation all identify with an LGBTQ orientation. The actor who’d played Larry (Calvin Leon Smith – who I also saw in the Bridge Award reading in September and who’s truly the real deal; this man will make you feel the whole spectrum of emotion) bridged the moment with grace and sincerity, explaining how he himself grew up as a queer-identifying boy in a southern family, making this show personally resonant and all too realistic. The Director followed up to say that if it seems the LGBTQ community appeared from nowhere or expanded at a precipitous rate, that’s only because we have now, for the first time, reached a period of acceptance when people who were long hidden and silent can finally be themselves and live liberated, honest lives. The answering applause was immediate and enthusiastic, followed by the voice of an audience member from the balcony shouting, “And everyone go vote tomorrow!”

(Cue critical self-examination of my previous assumption regarding service members/veterans’ political ideologies.)

From here, the questions became more personal, delving into the actors’ emotional journeys to portray characters experiencing turmoil, conflict, and loss. An audience member who was himself active in the arts asked MVP Calvin Leon Smith/Larry about his approach to channeling the emotion required of the love confession scene described earlier. Mr. Smith started his response with a shoutout to his acting teacher, who was in the audience. “Sorry, I just love him,” he said, becoming visibly emotional. He again referenced his upbringing and said that the tools he learned through acting for understanding and confronting the layers of his own emotions and identity had made a vast difference in his life, but how some elements of his on-stage performance remain unpredictable. “It doesn’t always happen,” he said, in reference to the tears he’d shed on-stage during the scene. I have to note here that this guy in particular really went the extra mile in terms of his honesty and willingness to become vulnerable with the audience. It was clear that this evening’s rendition of the scene in question had been particularly intense for him, but he leaned further into the self-exposure and was willing to openly examine and discuss the experience. His participation in the talkback truly epitomized the profound strength and utility in confronting and sharing moments of emotional rupture, even if difficult or unglamorous. I felt everything he said extraordinarily deeply.

OKAY I haven’t talked at all about our main man yet, but he features heavily in the last and most emotional question of the night! I already recapped this moment on twitter, but it really deserves more extensive description. The last guy to ask a question (it was more of a comment, really, but every heart in the theater was with this guy) was also a member of AITAF’s marathon team. Here’s the most complete recap I can recall what he said:

While deployed with his EOD unit some years ago, he suffered the loss of his best friend. In attempt to come to terms with his grief, he tried traditional therapy for years but it just wasn’t helping. Then he saw Adam’s TedTalk and it “changed his life.” (He paused here as he started becoming audibly emotional and apologized, then soldiered on.) He started becoming involved in acting, and the tools he learned and techniques he was exposed to finally helped him begin to understand and cope with his trauma. (“I finally felt like I wasn’t just angry all the time.”) He said how rewarding acting has been for him, and that he recently landed his first TV role and will be filming in LA soon. (Cue audience and cast on stage cheering and applauding.)

Spoken directly to Adam: “I really just wanted to say thank you and that what you’re doing really does make a difference.”

(Not lying, I just started crying a little just remembering this moment and typing this all out. The sincerity in everything he said was so palpable, the theater was entirely silent in solidarity, and I saw at least two of the actors on stage shed a tear as he spoke.)

Sitting there and listening to him, I remember being so struck by the raw emotion in his voice that in a weird way (and this is something I never thought I’d say), I couldn’t bear to look over at Adam right away? Almost like the moment was too intense or personal? But once the guy looked over and started speaking directly to Adam, of course I looked too. (God, I’m getting emotional again thinking about this!) Adam was leaning entirely forward in his seat, his attention undivided as if this guy were speaking to him face-to-face from two feet away. There were several pauses in his speech when the audience clapped in support, and I remember Adam holding his hands all the way out before him and clapping in sort of self-effacing recognition. It was clear it wasn’t like he was applauding the content of what was being said (about himself), but rather that he was recognizing and offering respect for this guy’s bravery to stand up and share something so personal, and for his successful journey of healing.

As soon as the question was over and the moment past, Adam leaned over to say something to a nearby security person. It was very clearly something along the lines of “I want to meet that man afterwards” and sure enough, homeboy got his meeting and picture later that night! Now THAT is a tearful happy ending right there if I’ve ever heard one. <3

Okay so with all that substance out of the way, let’s indulge in some classic fangirling, shall we? : ) Knowing that Adam wouldn’t be participating in the reading himself, I expected him to just make brief comments at the beginning of the show about AITAF’s mission, thanking the staff/volunteers, and all the usual. I was pleasantly surprised when he also read a short monologue himself – an excerpt from Take Me Out by Richard Greenberg. (You can hear him do the same monologue in the final minutes of the Vice AITAF documentary.) He tied the reading into the purpose of the evening’s event – an exercise in pausing to celebrate and honor ourselves, especially all the service men and women in the audience. Once he concluded, he left the stage and the cast came on to start the Fat Ham reading.

An unexpected highlight to the whole evening was having a clear line of sight to where Adam and Joanne were watching the play from a box off to the side of the audience. I loved having the chance to see Adam’s reactions to everything happening on stage, and I took almost equal enjoyment from both. It will surprise no one to hear that he’s an extremely attentive viewer. He watched most of the more serious, somber scenes with his head sort of cocked to the side in concentration, arms crossed in his lap. His mirth and delight from the play’s many uproarious moments was on clear display – it was like I could almost hear that weird, honky laugh of his. <3 I can clearly remember moments when I’d look over and just see him full on grinning, clearly enjoying and letting himself get lost in the performance. I mentioned on twitter how much he got into the Radiohead Creep scene, and he really did. It WAS quite a moment. Juicy starts singing the song with only partial commitment, but when the first chorus kicks in the whole cast suddenly lurch into the song in unison, moving to the rhythm as Juicy starts belting out the words. Adam was clapping with both arms over his head, and I wouldn’t be surprised if he let out a whoop in compliment.

When the play started getting more tense in its second half, I noticed Adam sort of resting his hand against his mouth. I couldn’t tell if he was actually biting his nails, but he definitely had his fingers against his lips in a sort of absent-minded way, while his attention was fixed elsewhere. He was clearly engrossed, and I loved this brief opportunity to watch him as a captivated viewer – a rare role reversal considering I’m usually the one watching him with that sort of reverence. And yes, it really made the funny moments all the more memorable and touching whenever I would look over and see Adam laughing right along with me, or just grinning the most boyish, adorable grin in the entire universe. (!!!)

As charmingly earnest as he was in his introductory speech (and just a tiny bit awkward with his initial ‘Hello!... Goodbye!’ to the audience when he stepped forward to see us past the stage lights), and as much as I loved getting to watch him as an audience member – reacting and feeling the same emotions as the rest of us, my biggest takeaway from the night is likely still that final exchange between Adam and the marathon team member. Adam didn’t have a microphone or the chance to respond right away, but he didn’t need to. This was an expression of profound and heartfelt gratitude in response to a conversation Adam had already started years and years before, and which Adam still devotes so much time, care, and energy to sustain. I left the event with a reminder of just how unique, how mighty and transformative Adam’s enduring commitment to realize, grow, and maintain AITAF truly is. A reminder that he has dedicated his passionate, theatre-loving heart to sharing the empowerment and resilience he himself discovered through the arts. And, finally, I left knowing that he has changed lives for the better – some in even more profound, consequential ways than how he has already touched mine.

In closing: Thank you Adam and AITAF for yet another supremely moving, unforgettable night.

84 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ADAM DRIVER in ANNETTE (2021) with MARION COTILLARD

part 1 | requested by @lumberjack00fantasies .

#ok but what is he so BIG for????#Annette#Adam Driver#Still one of my fav movies right here#I'm not even remotely joking

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

NEVER FORGET!

3rd Oct. 10

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

White Noise: A Dive So Deep We Need Scuba Gear

I’ve now been fortunate enough to see this movie twice, at the opening nights of both the Venice and New York Film Festivals. Between the two, I was traveling for almost a full month and kept furiously typing away at this piece little by little, whenever I found myself with a few spare hours on planes and trains. I’ve been ruminating on this film for a full month now and one thought just kept leading to another, and then I had to tack on a few new insights after last night’s NYFF screening. Which means.... this is nearly 10K words all together and I AM DEEPLY SORRY. This thing really just seemed to keep writing itself, and with a film this rich I am NOT to blame! >:(

Note: If you’re here just for the Adam highlights (understandable), then Part II towards the bottom is for you. <3

I’ll format this piece similarly to my Annette write-up from Cannes last year: I’ve written up a synopsis of the film and dropped it at the very bottom of this post. (Yes, you could also Sparknotes the book, but a few characters have been trimmed out, the chronology changed around a bit, and a few creative revisions were made.) If you’re here for all the plot spoilers, go ahead and scroll all the way down to read the synopsis first. If you’d rather skip spoilers, then go on and jump right into to the film discussion/analysis just below here (Part I). Any reference to specific plot points will be noted as “Spoiler #___,” and those who want to know can check the corresponding numbers in the synopsis at the bottom to see exactly what plot point is being referenced. This way, the write-up remains spoiler free for anyone who’d rather not dabble in the specifics just yet! With all those logistics out of the way… LET’S GO!!

Part I: So What’s the Movie Really About Anyway??

If I were going to structure this Logically™, I would likely start by examining exactly what “white noise” is being referred to in the title. The thing is, I need to work my way through a few preliminary layers of the story before I can reach that answer. My starting point to get there is a minor scene early in the book which, although omitted from the movie, seems instrumental to understanding everything that comes after. Here, Jack and Murray (a visiting Professor and the only colleague Jack appears genuine friends with; played by Don Cheadle in the film) drive to see a local tourist attraction in their small, middle-America town:

Chapter 3: Several days later Murray asked me about a tourist attraction known as the most photographed barn in America. We drove twenty-two miles into the country around Farmington. (…) Soon the signs started appearing. THE MOST PHOTOGRAPHED BARN IN AMERICA. We counted five signs before we reached the site. There were forty cars and a tour bus in the makeshift lot. We walked along a cow-path to the slightly elevated spot set aside for viewing and photographing. All the people had cameras; some had tripods, telephoto lenses, filter kits. A man in a booth sold postcards and slides – pictures of the barn taken from the elevated spot.

“No one sees the barn,” (Murray) said finally. (…) “Once you’ve seen the signs about the barn, it becomes impossible to see the barn. (…) This literally colors our vision. (…) What was the barn like before it was photographed? (…) We can’t answer because we’ve read the signs, seen the people snapping the pictures. We can’t get outside the aura. We’re part of the aura. We’re here, we’re now.”

Now, the first thing you’ll realize about Murray is that he loves to hear himself talk. The second is that he’s incredibly fickle in his observations. Sometimes he’s DeLillo’s monologue device for presenting his Points; other times he spouts bullshit and horrible advice to guide Jack into crisis. In the above quote, though, he frames the operative theme for us in a nice neat box.

I was in Paris the week before the Venice Film Festival, and the above scene immediately reminded me of seeing the Mona Lisa in the Louvre. Hundreds if not thousands of people shuffle into that display room and line up in front of the piece of artwork every single day, and yet I’d hazard to say that not a single one of those people actually look at it. They peer through camera lenses and selfie frames, the sight of the artwork itself utterly drowned out by the din of voices, press of the crowd, and overpowering presence of the hype. (No wonder everyone says ‘I thought she’d be bigger.’) Still, at least she’s a piece of venerated art in a world-class collection, worthy of spectacle.

But what about this barn? It bears noting that the barn itself is never described in the book – only the crowds and the scene around it. As Murray says, the barn itself has ceased to exist under the hype, under its own “aura.” The barn isn’t famous for any quality in and of itself – it’s only famous for being famous. For being photographed; for being the object of attention. In essence, the socially-constructed image of this barn has supplanted the barn itself. The crowds described here have not come to see the barn itself, but rather to be part of a socially fabricated and perpetuated idea of something great and noteworthy; of themselves as part of a grand and noteworthy tradition.

Okay cool, what does that have to do with anything? Just about everything, it turns out. Again and again throughout the story, we see a similar collapse between reality itself and representative concepts of reality. This is acknowledged most literally by Babette (Greta), when she describes a possible side effect of a particular drug as the loss of the ability to “distinguish words from things” (Chapter 26), giving the example of the words “speeding bullet” causing someone to fall to the floor and take cover. On a recurring and less literal basis, we see objective reality obscured by mass-marketed and sensationalized fabrication, and factual knowledge eroded by ever-shifting conjecture and rumor.

A simple example of this is the children’s reaction to news about (Spoiler #1) on the radio. Upon hearing radio chatter about potential symptoms, some of the children immediately begin manifesting said symptoms. They clap hands over their mouths and rush to the bathroom upon hearing broadcasted talk of nausea, and start scratching their hands at the mention of sweaty palms. (In a golden comedic moment, Heinrich tells his sisters they’re showing “outdated symptoms” when they exhibit nausea after the radio moves on to claims of dejavu.) This isn’t simply the power of suggestion or hypochondriac tendencies, however; the all-important influence here comes from the perceived source of authority. To illustrate - think about how, when wondering about the weather, we often check our phone weather apps instead of looking out a window. This is a case of observable, perceptible reality becoming secondary to media-generated description. This is a case of our human perception gradually being rendered secondary to the passively assumed intelligence of machines and the supposed infallibility of technology-driven frameworks for data collection, analysis, and dissemination. Towards the beginning of the book, Jack alone appears skeptical of such developments:

Chapter 6: (Heinrich) “It’s going to rain tonight.”

(Jack) “It’s raining now,” I said.

“The radio said tonight.”

“Look at the windshield,” I said. Is that rain or isn’t it?”

“I’m only telling you what they said.”

“Just because it’s on the radio doesn’t mean we have to suspend belief in the evidence of our senses.”

“Our senses? Our senses are wrong a lot more often than they’re right. This has been proved in the laboratory. Don’t you know about all those theorems that say nothing is what it seems? There’s no past, present or future outside our own mind. (…)

“Is it raining,” I said, “or isn’t it?”

“I wouldn’t want to have to say.”

(Sidenote: Heinrich is Jack’s oldest son from a prior marriage, and not nearly this annoying in the film. Shocker - he’s actually likable : ))

Such alienation from our immediate surroundings and from the conclusions of human rationality also appear in less literal but more overarching ways throughout the narrative, influencing how the entire cast of characters perceives and acts in this world. Even Jack is not immune to these inclinations; all characters appear equally susceptible to the dictates of advertising, the sensationalist thrall of the television, and the venerable power of retail therapy. These are all further types of removal from the immediacy of human experience and natural reliance on human knowledge. As Murray explains with his trademark flourish of bullshit:

Chapter 11: “You have to open yourself to the data. TV offers incredible amounts of psychic data. It opens ancient memories of world birth, it welcomes us into the grid, the network of little buzzing dots that make up the picture pattern. (…) Look at the wealth of data concealed in the grid, in the bright packaging, the jingles, the slice-of-life commercials, the products hurtling out of darkness, the coded messages and endless repetitions, like chants, like mantras. ‘Coke is it, Coke is it, Coke is it.’ The medium practically overflows with sacred formulas if we can remember how to respond innocently and get past our irritation, weariness and disgust.”

In a crude sense, this is the epitome of “life imitates art.” Most of us would probably balk at terming television “art,” but these characters have no qualms doing so. They elevate it as a valued source of “psychic data” – as a source of knowledge and enrichment that somehow prefaces human cognition, rather than being its byproduct. In this world, the egg lays the chicken and no one seems to question the operative logic.

The immense influence of these so-called “coded messages” in commercials and advertising jingles is most strongly felt in the grocery store where all the characters shop. More than any other place in this small town, the grocery store is presented as the sacred heart of communal gathering, personal replenishment, and harmonious oneness. Beyond the grand variety of products on offer, the layout and lighting of the store are extensively described with an awe and reverence usually reserved for grand cathedrals or vast library archives. To these characters, this is not dissimilar to the central role in their lives of mass-marketed goods and consumerism. See the below excerpt from Jack’s shopping spree in the local mall:

Chapter 17: I began to grow in value and self-regard. I filled myself out, found new aspects of myself, located a person I’d forgotten existed. (…) The more money I spent, the less important it seemed. I was bigger than these sums. These sums poured off my skin like so much rain. These sums in fact came back to me in the form of existential credit. (…) They were my guides to endless well-being.

In this society, the products people choose to purchase, wear, or consume define their sense of identity and self-worth more strongly than their occupations, beliefs, or any other aspect of their lifestyles. When Denise takes to wearing the same green visor every day for three weeks, Jack observes “something about the visor seemed to speak to her, to offer wholeness and identity.”

Murray, ridiculous monologuer he is, makes the grocery store’s status as veritable temple of consumerism explicit:

Chapter 9: “Tibetans believe there is a transitional state between death and rebirth. Death is a waiting period, basically. (…) In the meantime the soul restores to itself some of the divinity lost at birth. (…) That’s what I think of whenever I come in here. This place recharges us spiritually, it prepares us, it’s a gateway or pathway. Look how bright. It’s full of psychic data. (…) We don’t have to cling to life artificially, or to death for that matter. We simply walk toward the sliding doors. Waves and radiation. Look how well-lighted everything is. The place is sealed off, self-contained. It is timeless. (…) Here we don’t die, we shop. But the difference is less marked than you think.”

There you have it: “Here we don’t die, we shop.” Here, consumption is elevated to a spiritual act; the grocery store becoming the new house of worship. Not only does the act of shopping provide spiritual restoration, it insulates one from the perpetual specter of death. And to be sure, our protagonists fear nothing more. Jack and Babette repeatedly discuss which of them is more likely to be the first to die, and as the story progresses both take increasingly drastic measures in attempt to escape their overwhelming fear of death. Mind you, it is not exactly death itself that so plagues them, but their psychological fear of it. It is their smallness, their powerlessness before something that cannot be conquered by a credit card or broken down to its constituent parts and explained away in radio-generated technical analysis. It is the unknowability and unpredictability of death that haunts them. This is why, interestingly, when an experimental pharmaceutical is developed with the claim of curing not death itself but merely alleviating the fear of death, it is lauded as if promising eternal life itself. This is yet another demonstration of these characters’ removal from the direct, unmediated truth and experience of reality.

In a world where Denise’s visor or Jack’s dark-tinted glasses and black academic robes constitute identity; where an emergency in the town is addressed by a team of experts in simulated evacuations who announce “we are not here to mend broken bones or put out real fires. We are here to simulate,” - our protagonists navigate artificial systems of belief and representation more than they actually live in a true, immediate sense. Alienated from direct confrontations with reality and human logic as they are, they are woefully ill-equipped to confront the inevitable and inarguable prospect of death – the prospect of all the supposed protections and charms of their material comforts being stripped away and rendered meaningless.

You might be thinking there’s a certain irony in a Professor – a supposed learned, logical man of thought – falling victim to these mass trends of illogical groupthink. To be sure, Jack is an interesting blend of often being the most intelligent person in the room and also the most passive. He spends much of the first half of the book as a Nick Carraway-type observer and reader stand-in. He listens and passively engages in conversations more than he acts or challenges. He hangs on every word of Murray’s diatribe on the supermarket as a Tibetan holy land, without a single facetious challenge. At first, he simply lets us take in and understand his world through his eyes. At first, he feels no need to act out or challenge the system. This changes as the story progresses, however, and as his fear of death becomes more and more immediate and debilitating. Before we get into Jack’s eventual response to his material-driven, counter-intuitive surroundings, though, it’s finally time to circle back to where we started.

So what is the “white noise” anyway?? Well, it’s both the disease and the cure. As Heinrich grandstands to his family across the dinner table one night: “The real issue is the kind of radiation that surrounds us every day. Your radio, your TV, your microwave oven, your power lines just outside the door. Your radar speed-trap on the highway. (…) It’s the things right around you in your own house that’ll get you sooner or later. It’s the electrical and magnetic fields.” More than just the ill effects of pollution, he’s alluding to data overload, choice fatigue, and sensory saturation. The television and radio – once supposed sources of knowledge, facts, and entertainment – have instead become mechanisms of removal from our own senses and cognition. Instead of expanding our minds, the end result is deterioration and alienation. (Think for a minute about rampant disinformation in our current “fake news” era. Think about our ever waning capacity or interest in fact- or source-checking since the advent of the smartphone. Seriously, talk about DeLillo being ahead of his time.)

“You can’t hear it if it’s everywhere” reads the film promo poster; “What if death is nothing but sound?” / “Electrical noise.” / “You hear it forever. Sound all around,” Jack and Babette theorize in the novel. With a growing sense of dread, the characters fall more and more under threat from the same ubiquitous sound-and-information wall they have come to trust more than their own minds. The “white noise” is the fleeting, ultimately meaningless, but apparently all-powerful influence of vapid materialism; its indoctrination delivered by television and advertising. It saps vitality while professing to bestow it. The “white noise” is the ever-growing influence of technology and computer-generated knowledge as it becomes forever externalized, unnatural to and yet elevated above our own minds. The “white noise” is the advance of technology, weapons, and pharmaceuticals, where a new form of energy may be just as likely to destroy a town as to power it, and a new experimental drug may be just as likely to kill you as it is to save your life. And yet, despite these dangers and slow corruptions, we perpetually crave more more more. To claim “stop” or “enough” feels somehow counter to beneficent societal progress and even to life itself. And so, that which slowly, inevitably kills us (radiation, pollution, technological progress) is also what purports to bring us solace from said dying. Through all our attempts to conquer or protect ourselves from death, we have made it omnipresent.

Let’s now turn back to Jack’s individual journey, as he seems to become increasingly aware of these disembodied threats. His slow descent into desperation is explained through his early lecture on the death-defying power of crowds versus the helplessness of the isolated individual.

Chapter 15: “Crowds came to form a shield against their own dying. To become a crowd is to keep out death. To break off from the crowd is to risk death as an individual, to face dying alone. Crowds came for this reason above all others. They were there to be a crowd.”

This manner of thinking is why, when faced with the prospect of death in a communal, abstract sense from (Spoiler #1), Jack remains relatively unperturbed. He keeps a level head, reassuring his family that all will be well. He seems downright complacent in his sense of security and self-regard, demonstrated by the dialogue in both book and film where he states with equanimity that:

Chapter 21: “These things happen to poor people who live in exposed areas. Society is set up in such a way that it’s the poor and the uneducated who suffer the main impact of natural and man-made disasters. (…) I’m a college professor. Did you ever see a college professor rowing a boat down his own street in one of those TV floods? We live in a neat and pleasant town near a college with a quaint name. These things don’t happen in places like Blacksmith.”

Considering Jack’s thorough saturation in consumerist culture as discussed above, I regard this belief as not necessarily classist, but more as misguided faith in the assured safety afforded by material prosperity. Babette holds a similar belief, evidenced when she says she can’t imagine death above a certain “income level.” Jack is a regarded and presumedly well-paid academic, and the family have so far lived ensconced in their refuge of upper middle-class society. When they’re forced to (Spoiler #2), Jack and Babette seem to retain an implicit belief in their income bracket-granted security, with the sense of threat further reduced by its collective nature and the presence of a protective crowd around them.

However, their distance from the danger of death eventually collapses. After hearing (Spoiler #3), Jack must abruptly confront the idea of death in a starkly individual sense. In an ironic twist, his tendency towards blind faith in the expertise of technology makes his personal doom seem all but assured, given this revelation was informed by data on a computer – or by “the passage of computerized dots that registered my life and death.” Jack does not dissent when told “you are the sum total of your data. No man escapes that.” He reacts with only passive, helpless acceptance.

Faced with the prospect of his impending data-determined demise, Jack struggles to come to terms with the harsh reality of his individual mortality. The shiny groceries and excessive shopping sprees that once lent identity and refuge can offer no protection. All of the material clutter Jack accumulated throughout his life gradually becomes a mere reminder of his aging and vulnerability. As his presumed death seems to draw closer, he begins compulsively purging the house of these now offensive objects. (A particularly memorable and powerful shot in the film shows Jack sitting on the floor after looking for something in the household trash. He sits surrounded on all sides by the useless, meaningless detritus all of his trashed purchases have now become.) However, this doesn’t mean that he summarily rejects the idea of consumption as a life-giving force; it merely transforms in his mind into something more pernicious.

Jack’s decline towards his darkest and most desperate moments begin when Murray plants yet another ludicrous idea in his mind:

Chapter 37: (Murray) “Think how exciting it is, in theory, to kill a person in direct confrontation. If he dies, you cannot. To kill him is to gain life-credit. The more people you kill, the more credit you store up.” (…)

(Jack) “You think it adds to a person’s store of credit, like a bank transaction.”

(Murray) (…) ”It’s a way of controlling death. A way of gaining the ultimate upper hand.”

Sounds like total nonsense, right? Yet this is perhaps the logical extreme for a lifestyle that worships at the supermarket and listens to the radio and television as the veritable voice of god. This idea of “life credit” is suspiciously similar to the “existential credit” Jack previously felt he was accumulating through his purchasing power - as if monetary expenditures could enrich the soul with dollar-for-dollar equivalence. So if safety and prosperity can be bought on earth, why not in the afterlife as well? In this society, even life and death have become commodified and transactional.

(If you’ll indulge me a personal note, this is where the story gets extra juicy for me because of its parallels to Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club – aka one of my favorite books of all time and the subject of my English thesis in undergrad. This probably excites no one but me, but it couldn’t be clearer here how direct of an influence DeLillo must have been for Palahniuk, because the Fight Club narrator’s turn towards violence and self-destruction as a source of meaning is so so similar to Jack’s internal dissolution at this point in the book. Can you hear my geeky, gleeful excitement just jumping off the page here? But okay okay, let me slow down and back up for a second here….!)

As we reach our climax, Jack finds himself with both: 1) The idea that external acts of violence can protect him from death in a way no purchase ever could; and 2) A motive and target for his violence – the man responsible for (Spoiler #4). When he confronts said target with a gun in his hand, he savors the resulting sense of power and control. Beyond that, he also feels as if he has finally broken through the omnipresent veil of white noise that has misinformed and misguided him for so long. For a moment, he feels he is seeing the world as it truly is. (Chapter 39: I sensed I was part of a network of structures and channels. I knew the precise nature of events. I was moving closer to things in their actual state as I approached a violence, a smashing intensity.) For a moment, he is convinced he has seized direct and immediate control over his own life and death in its true essence, rather than continuing to live through artificial mediums.

But of course, this moment of epiphany and empowerment proves as fleeting as the idea that guided him there. The book/film’s true moment of spiritual introspection and enlightenment arrives not through a squalid encounter with violence, but rather during (Spoiler #6) and the resulting consideration of artificial systems of belief. This is not quite a meditation on the value or credence of the content of certain belief systems – be they religious or material-based - but rather the importance of the maintenance of such systems themselves.

It seems to me that religion is something of an elephant in the room for most of this story. It seems conspicuously absent given our key cast of characters are a white, middle-class, middle American family – probably the most likely group I can think of to frequent church on Sundays. Jack and Babette also seem particularly predisposed to the promises and assurances of organized religion (another form of advertising in and of itself, a cynic could argue) given their troubling preoccupation with death. And yet, this scene towards the end of the story is notably the first time our characters ever directly encounter or contemplate the tenets of Christianity’s afterlife. After turning to all manner of products and pharmaceutical inventions in attempt to alleviate their crippling fear of their own mortality, only now in the story’s final act do they finally ask the question that may have neutralized their fear in the first place: “What does the Church say about heaven today? Is it still the old heaven, in the sky?” (Chapter 39)

Then again, perhaps this prior absence does make sense, given that this story isn’t meant to examine the content or veracity of religion itself, but rather the question of why such an elaborate, socially constructed, and universally shared structure of belief is necessary. The climactic conversation in this scene does not center upon whether religious teachings are true and their supposed adherents sincere or not, but rather why these ideas and believers are so necessary in the first place. We are instead asked to consider the crucial role of such belief systems and the damage that would befall the social fabric of civilization should these systems collapse in their entirety. (Chapter 39: “To abandon such beliefs completely, the human race would die. This is why we are here. A tiny minority. To embody old things, old beliefs. The devil, the angels, heaven, hell. If we did not pretend to believe these things, the world would collapse.”) Upon my viewing, the film seems to make a markedly different commentary from the book on whether or not modern, material-based systems of belief can adequately perform the same function as religion, in terms of structuring and maintaining society through the provision of faith and purpose.

Before I dig further into these differences between book and film, I want to spend another minute considering Jack’s role in and relation to these artificial belief systems. In terms of Jack’s trajectory, we first see him buying into (literally) the operative belief system built around the primacy of consumption and the elevation of material well-being as the highest form of spiritual and even intellectual wealth. Once forced to confront his own mortality, he finds this value system lacking in its ability to provide him any true protection and briefly turns against it, purging his material possessions and contemplating destruction as a backwards means of preservation as he sinks into anti-social inclinations. (In this portion of the story, Jack takes up the mantra “shoot don’t talk, steal don’t buy.”) By the story’s end, he reaches the relatively hopeful point of reassimilation into the operative societal values of the day. He comes to a point of newly found acceptance that certain forms of chaos (e.g. death) will always exist, but so too does the collective resilience necessary for people to endure alongside such chaos. In the book, this realization is implied when little Wilder miraculously rides his tricycle across a multi-lane highway without injury. In the film, this peace with the unknown is depicted through the family’s final joint trip to the supermarket together – reaffirming that Jack and the people around him will “keep inventing hope” and participating in the belief systems that make order and optimism possible. (One of the final lines of the film; not in the book as far as I can find.)

So this is all fine and good, and gives us a relatively happy ending for Jack and his small town family. The film’s depiction of these events, however, scrutinizes the role of human nature in both the perpetuation and destruction of these essential belief systems. When faced with a crisis of faith in societal values, will people always act as Jack did? Will we always seek self-harming and/or violent means to construct a façade of protection against the unknown – against whatever threats society’s knowledge systems fail to classify and resolve? Beyond that, is humanity’s habit of rampant consumption a reflection of our innately destructive nature? Will the systems of faith and values we construct, no matter how well-intentioned, inevitably lead to conflict? (Think conflict over resources, wealth, or even inter-faith conflicts throughout history) The question of whether men are inescapably violent by nature is already raised by Babette in both book and film: “A male follows the path of homicidal rage. It is the biological path. The path of plain dumb blind male biology.” (Chapter 35)

The film takes this line of questioning further with a distinct, stylized shot of Jack in the car on the way to his encounter with violence. While muttering “shoot don’t talk, steal don’t buy” to himself under his breath, an overlay image of a smokestack shooting out flames appears over top of him. This strange, surreal juxtaposition invites us to consider the interplay between malleable, socially-constructed systems and immutable human nature. This can also be seen as a more extreme version of the “life imitates art/art imitates life” quandary regarding society’s relationship to television and media. Do we build smokestacks as an extension of our innate instinct to produce and consume to endless, reckless levels; or have we taken on the traits of the objects we’ve built and installed into the world around us? Whichever direction this cycle of influence flows, have we lost the ability to control it?

Returning to the differences between book vs film, I’ll now circle back to what seems to be a considerable contrast in intention between DeLillo and Baumbach’s treatment of this story. What commentary or value judgment does each auteur seek to convey regarding the artificial, secularized systems of belief underpinning much of modern society? Are they critical, laudatory, or neutral? After finishing the book and seeing the film in close succession, I was struck by a marked difference in tone between the conclusion of each. While the film ends in a surprisingly cheery, reassuring burst of color and energy, the book winds down to a relatively glum, unremarkable ending that never quite escapes the book’s heretofore greyscale tone.

While DeLillo’s novel delivers Jack from the worst of his personal demons, the final pages nonetheless seem to pass harsh judgment on the way of life in which Jack and his family are embedded. In the final chapter, the abrupt rearrangement of the supermarket shelves and the resulting chaos seems to betray how fleeting and fragile this set of consumerist values really is, and to foreshadow that it will perhaps inevitably collapse. (Chapter 40: In the altered shelves, the ambient roar, in the plain and heartless fact of their decline, they try to work their way through confusion.) Descriptions of these bewildered consumers first focus on the older shoppers, shuffling and squinting their way through the aisles. At first, the above quote could seem to apply to the timeless experience of an older generation finding itself out of touch with a rapidly modernizing world. True enough, Jack does often feel this type of alienation from the younger, more tech-savvy generation personified by his children. However, it seems clear by the book’s concluding lines that this state of disorientation and powerlessness has a much broader reach, perhaps even to universality. All shoppers, young and old, seem to be portrayed as the living dead, separated from death by only a waiting area – the pseudo purgatory of the grocery store itself. Remember Murray’s line “Here we don’t die, we shop” and his speech likening the grocery store to a Tibetan transitional state between life and death. In the book’s final passage, what once seemed mere pretension now comes true, but without any of Murray’s excitement:

Chapter 40: This is the language of waves and radiation, or how the dead speak to the living. And this is where we wait together, regardless of age, our carts stocked with brightly colored goods. A slowly moving line, satisfying, giving us time to glance at the tabloids in the racks. Everything we need that is not food or love is here in the tabloid racks. The tales of the supernatural and the extraterrestrial (…) The cults of the famous and the dead.

Thus the great and tragic irony emerges: Our fear of death and aversion to the unknown drives us to construct entire lifestyles around their avoidance; but by doing so we have poisoned our air, our earth, and our bodies. We have indelibly ingrained death into all we see, hear, and do. We invent increasingly capable and intelligent machines which know more about us than we do ourselves – which make our world more unintelligible and hostile with each successive upgrade. (Chapter 40: Dr. Chakravarty wants to talk to me but I am making it a point to stay away. (…) He wants to insert me once more in the imagine block, where charged particles collide, high winds blow. But I am afraid of the imaging block. Afraid of its magnetic fields, its computerized nuclear pulse. Afraid of what it knows about me.) If our own inventions don’t kill or replace us directly, they render our human cognition and experience superfluous and obsolete.

The film, on the other hand, concludes with no such feeling of bleak, inevitable catastrophe. To the contrary, the ending feels almost incongruously carefree following the film’s tonal dips into horror, surrealism, and squalor. While Baumbach fully delves into each shadowy crevice of the book’s narrative exploits and intellectual inquiries - often with loving, word-for-word dedication – he nonetheless manages to steer his screenplay to an entirely different destination. In contrast to the sense of displacement and inevitable decline characterizing the book’s conclusion, the film’s final commentary runs in the entirely opposite direction. The family’s final visit to the grocery store is instead a life-affirming and downright joyous occasion. If a tongue-in-cheek value judgment is being passed upon these characters for taking such enjoyment from their family grocery outing, it’s certainly well buried. In this final scene, the grocery store is depicted as an unironic, true site of reprieve, unity, and renewal. Of the whole film, this scene is the single one must suffused with life and energy. Not only are the shelves brightly colored and gleaming, but the entire atmosphere is lively and jubilant. This is not damnation but optimistic deliverance.

Baumbach has not entirely done away with the original likening of the grocery store to a place of worship, but he has redirected this parallel in his own way. While watching the delightfully exuberant song-and-dance number that plays during the credits, I had the thought that the wide aerial shots of the grocery aisles were somewhat reminiscent of aisles or pews in a church, filled with people all participating in a coordinated, choreographed ritual not entirely unlike the steps of receiving holy communion or standing, kneeling, and standing again during a mass. The grocery store is once again elevated to the essential and otherworldly, but this version is a place where simple, material pleasures are delighted in and celebrated – their common language one of hope and resilience. Perhaps here we don’t die, we dance.

Part II: Forget All That, I’m here for Adam Highlights ONLY

• One of the strangest and scariest scenes of the film is also one of Adam’s cutest?? At one point he dreams that he wakes up to see a stranger sitting in his bedroom, who gets up to use his bathroom and then wordlessly lays down in the bed next to him. This is a fairly long, silent sequence during which Jack just lays in bed looking increasingly sleepy, scared, and deeply confused all at the same time. LET ME CUDDLE AND PROTECC!

• The outfits. Guys, ThE oUTfITs! Whenever he’s on campus in his ~Professor persona, he wears what are truly the most HIDEOUS shirts (think bright ass orange and paisley) in the entire universe under his dramatic af black robes, paired with even mORE dramatic af dark glasses. He looks like the only clown I would ever want to make out with in the entire history of time.

• I mentioned the German lessons in my initial twitter thread, but they need another shout out. Maybe this was extra adorable to me because I speak German, but there’s a scene where he’s at a lesson with his tutor and the tutor basically just says random sentences and has Jack repeat them without explaining anything. They get hilariously stuck on the sentence “Ich esse Kartoffelsalat.” (I eat potato salad.) After repeating it back and forth a few times without any marked improvement in Jack’s pronunciation or comprehension, his tutor points firmly at himself when he says “Ich” in attempt to demonstrate that he’s referring to himself. But Jack, totally clueless baby, points at the tutor, thinking the word means “you” and just keeps repeating the sentence without getting any better. Think Paterson energy from the scene where Laura asks him to guess what’s in the mystery dinner pie. SAME ENERGY AND IT’S MY FAVORITE.

• Okay one of Adam’s best/most ~dramatic scenes is also one of the most climactic of the film. One of the other professors asks Jack to contribute to one of his lectures, knowing Jack’s participation will lend credibility. This leads to Jack jumping off into an entire captivating and spirited yet also deeply freaky diatribe about Nazi death cults. But Adam actually pulls off the feat here of making this scene both deeply unsettling and humorous at the same time?? Unsettling because of his booming, deep ass Alpha voice talking about death cults… but humorous because of his delivery and body language. Like I remember a moment where it looks like he’s finished talking and disappeared into the audience, and then he pops up out of nowhere from behind some students looking like a gigantic bird in his dark academic robes and it’s somehow sort of delightfully weird?? Oh and I didn’t even mention the hilariously extra moment when he first references the word “death” in this lecture and basically the whole movie comes to a grinding halt to let Jack emphasize the !!!!dramatic word!!!! It’s such a weird, inscrutable, yet undeniably powerful moment. He proclaims “Deaaaath!!!” twice for emphasis, with his voice all echoey and some dramatic, slow-mo arm waving going on. I’ve seen this movie with my own eyes yet still can’t explain this at all, evidently.

• I also already mentioned this on twitter but I’m still not even 1% over the fact that THAT BELLY WAS AT LEAST PARTIALLY REAL. You think you’re going to see an innocent, harmless scene at the doctor’s and then boom, your brain is desperately CTRL-ALT-DELETING in attempt to process the site of Adam with his shirt unbuttoned all the way down and an undeniable belly just chilling right there, all attached to our beloved Burberry centaur bod. My friend and I quite literally turned and gasped at each other, shooketh. I do still think they padded his belly out a bit extra when he’s fully dressed because it just doesn’t seem proportional to the rest of him, but…. at least some of the junk in that trunk (shirt) is all Adam. I wish for each and every one of you reading this that you find someone who loves you as much as Adam clearly loves Noah to be THIS committed to this weird af role.

• Ok this was one of the more surreal parts of the movie where I was actively sitting there with an internal mantra of “wtfwtfwtfwtf” running through my head. There’s a weird montage scene where Jack is ~in crisis~ and it cuts back and forth to him in a few different places, including the table where he and the other professors usually eat at the college, and his German lessons at the tutor’s house. The two settings jarringly and hilariously merge all of a sudden, when you hear Jack’s tutor instruct him “stick out your tongue” (for pronunciation purposes?? Idk?) and then you see Jack, seated at the teacher’s table on campus, abruptly turn to look straight into the camera and - you guessed it - stick out his tongue with reckless abandon. Yes folks, riiiight into the camera. Still have a lot of confused, alarmed feels over that moment.

• Okay okay: The moment I thought was his personal best from the whole thing. In the ensuing conversation from Spoiler #5, emotions are all over the place and Jack and Babette start kissing while they’re both extremely emotional. Jack seems to have a handle on himself when he first sits down next to her in bed and kisses her, but then you can see his chin start to tremble, then his entire face, then all the rest of him. He first tries to keep kissing her through it and holding himself steady, but he eventually breaks off when he becomes visibly overcome by all the emotions he’s struggling with in this moment. It’s a wrenching moment of heartache and helplessness.

• For better or worse, Jack’s favorite expression of approval/excitement is “First rate!” We get this incredibly geeky comment in the best and worst situations, including when he and Babette are kissing in bed and she asks if she should read something sexy to him (first rate) or when she asks if she should make chili fried chicken for dinner (again while they’re in the middle of kissing and, again, first rate). Thanks I hate it. Truly. <333333

And now a very relevant and necessary gif of Adam looking like a snacc at the Venice premiere. As I said: Necessary.

Film Synopsis (Do NOT read further if avoiding spoilers!)

The film is presented in three chapters, titled the same as the three sections of the book.

Chapter 1: Waves and Radiation

The first chapter is largely set-up, giving us the chance to get to know the various family members in all their charming idiosyncrasies. Jack Gladney is our protagonist – the only character whose perspective the film occasionally breaks its objective distance to tap into. Jack is a Professor and highly regarded in academic circles for his pioneering establishment of Hitler Studies. He shows reels of Nazi rallies during his classes and gives thrilling, melodramatic, macabre lectures on Hitler rallies as unique gatherings celebrating death, and about how all plots of any kind inevitably progress towards death. (Yes, he has something of a one-track mind on this subject.)

He and his wife, Babette, are each other’s fourth spouses. They look after Heinrich (Jack’s oldest son from a previous marriage), Denise (Babette’s oldest daughter from a previous marriage), Steffie (Jack’s younger daughter from a previous marriage), and little Wilder (their own). The two have a tender relationship, though Babette is occasionally prone to unexplained memory lapses. Denise expresses concern to Jack regarding her mother’s memory lapses, and claims to have seen Babette taking unidentified pills. When asked by Jack, Babette claims she doesn’t remember taking anything, though the audience previously saw her swallow a pill and hide the empty bottle in the bottom of the kitchen garbage disposal.

Chapter 2: The Airborne Toxic Event

As you can surmise, this is where shit goes down. (Spoiler #1) Following a train derailment at the edge of town, a huge black cloud appears in the sky and all residents are instructed (Spoiler #2) to evacuate their homes on account of the cloud containing dangerous chemicals. The family get stuck in a long traffic jam while leaving town, and at one point have to stop for gas, where Jack gets out of the car in the rain to refuel the car. At one point he thinks he sees Babette swallow a pill, but when he asks she claims it was just a lifesaver.

Once they arrive at their evacuation point (a boyscout camp), all evacuees are asked whether they were exposed to the cloud or rain for longer than ten seconds. Jack speaks to one of the staff members about his possible exposure, and after claiming to have checked all of Jack’s files on a computer system, (Spoiler #3) the staffer tells Jack that while the effects of the chemical in the cloud on humans are not yet specifically known, he will most likely die within the next thirty years. (Or will he? The “data” from the “computer” is all very ambiguous and impersonal, and the so-called staff “experts” are only trained in evacuation simulations.)

That night, Jack confides the hard news in Murray, his colleague and friend. Murray offers Jack a handgun, expounding on the idea that the transition into a “killer” from a “dier” could help safeguard one from impending death. Jack reluctantly takes the gun.

During a frenzied departure from the boyscout camp the next morning, Steffie (I think?) loses her stuffed bunny and Jack separates from the group to go back and retrieve it. An ominous stranger picks up the toy just before Jack reaches it and hands it to him. Though Jack doesn’t quite see the stranger’s face, he is familiar from an earlier nightmare when Jack believed he saw the same man sitting in his bedroom in the middle of the night. Several days later, the family are finally cleared to return home.

Chapter 3: Dylarama

While Jack secretly sees various doctors to try to determine the actual harm from his exposure level, Babette becomes withdrawn and listless. Denise and Jack grow increasingly concerned about her, until Denise finds a pill bottle marked “Dylar” hidden under the radiator cover. Jack takes one of the pills to be analyzed by a colleague, who can confirm only that the drug is not on the market.

When Babette comes home late one night without explanation, Jack confronts her about the pills. After much cajoling, Babette finally explains everything: She volunteered for a study of a new, experimental drug after seeing an ad in the newspaper. She believed this drug would be able to provide relief for a condition she’s been suffering. The study was officially closed before she received the drug, but (Spoiler #4) in her desperation she came to an arrangement with one of the researchers that she would regularly sleep with him in exchange for the drug. She breaks down in both shame and hopelessness, because the drug failed to cure her condition. Jack is surprised when she admits the condition is an acute fear of death, as he had assumed her fear couldn’t possibly be greater than his own. (Spoiler #5) He attempts to comfort her, but he is clearly upset by the revelation of her having been with someone else. She refuses to tell him who the man was, in case Jack might try to kill him in revenge. Jack is baffled by this, but Babette maintains any man can tap into a well of violence if the situation is right.

As his potentially impending death continues to burden him, Jack begins to seek out Dylar pills despite Babette’s claim that they did not work. While looking through the trash for the pill bottle, he spots the newspaper ad Babette responded to, which includes a phone number. Jack calls the number, claims he wants to buy Dylar, and arranges a meeting.

Jack brings the gun when he goes to meet the man (Mink) in a seedy highway motel. Upon seeing him, Jack realizes this is the stranger he kept seeing in nightmares and at the boyscout camp. From Babette’s prior description of the room, he also realizes this is where she would come to meet Mink. Tormented by imaginings of them together and intending to steal the remaining Dylar pills, Jack shoots him twice. Assuming the man dead, Jack attempts to frame the scene as a suicide by planting the gun in Mink’s hand. Babette arrives just as Mink returns to consciousness and shoots Jack in the arm. The bullet grazes/ricochets off Jack and skims Babette’s leg, giving them both only minor wounds.

Jack and Babette load Mink into their car, intending to take him to a hospital. He doesn’t remember what happened, so Babette supplies that he shot them both and himself with the gun still in his hand. At the hospital, (Spoiler #6) the three of them are treated by nuns, whom the couple ask about the afterlife and the existence of heaven. The nuns reply (in German, so not comprehensible to Jack/Babette, only to us through translated subtitles), that they only pretend to believe for the sake of all the non-believers.

Life continues as usual, with Babette seemingly back to herself and Jack no longer tormented on the daily by his potential exposure. The last shot is the whole family entering the supermarket, harkening back to earlier lines describing the supermarket as a place for “spiritual renewal.” It ends on an optimistic note, then tilts towards full-on joyful during the extended end credits dance number in the grocery store. (Seriously, these are some credits you don’t want to skip!!)

A final note on book vs film differences: I’m sticking this down here because there’s no way to make it non-spoilery. In the book, Jack experiences the whole climactic confrontation with Mink and enlightening encounter with the nuns on his own. On the page, the last full interaction we see with Babette happens just before Jack leaves for the hotel. The exchange is tense, and he leaves with a barbed reference to her meetings with Mink. We don’t really see their relationship mended or any particular warmth between the two before the book’s end – the narrative remains focused on Jack’s individual experience.

I was extremely gratified to see Babette join these final scenes, as her presence injects life and humor into what had been the darkest scenes of the film. The filthy hotel room that could have been the setting of a horror film only seconds before is immediately rendered comic when she and Jack point at each other, exclaiming “You’re shot!” / “You’re shot!” and then stand over Mink together, haltingly explaining that although he tried to shoot them, they magnanimously forgive him. Adam and Greta work so well off each other in these farcical moments; Noah was exactly right to write her into the film’s final stretch.

Her presence at Jack’s side for both the encounter with Mink and the conversation with the nuns about the survival of faith allows these scenes to provide welcome resolution to their earlier marital conflict. After the first half of the film took time to show the warmth between them, I certainly wanted to see their trust and closeness rekindled before the end. Experienced together, these final scenes become the trial that brings them back together, until they’re holding hands across their respective beds in the hospital - a moment that felt both cheesy and relieving, hinting a return to their life of oblivious suburban security and contentment. Seeing their reconciliation here also makes the film’s conclusion much more satisfying and hopeful across the board. Both characters spent the majority of the film silently struggling against their individual fear of death, and know we see that fear alleviated through union.

Giving Babette a more active role here also elevates her from something of a supportive prop piece to more of a co-protagonist. In both book and film, Jack has a strange tendency to refer to Babette in the third-person:

Chapter 26: “You’ve been depressed lately. I’ve never seen you like this. This is the whole point of Babette. She’s a joyous person. She doesn’t succumb to gloom or self-pity.”

You don’t even really need the ~feminist critical lens~ to see how this hints to Jack (and the narrative as a whole?) viewing Babette as more of a concept than an individual. When she begins growing depressed, book!Jack sometimes seems more upset for himself over the loss of her cheerful influence than he is over her distress. He seems annoyed over the disruption in her role as happy, comforting wife who confides all in him. But her appearance in the film when Jack is at his lowest – when she is the one to propose what to do with Mink’s body and how to cover up what’s happened – makes her individual personhood both undeniable and necessary to him. All in all, giving her a larger role here was a vast improvement for both her character and the story’s narrative satisfaction as a whole.

*Deep breath*

Okay, I think that’s really it. Those are all my thoughts ..... for now. If you’re actually still reading this, let’s elope maybe??

One of the best parts of being a fan of Adam is experiencing so much unique, thought-provoking cinema I would likely never have encountered otherwise. Yet another reason why I so appreciate him and all he does. <3 This entire write-up took an unholy amount of time, thought, and effort, but I enjoyed the heck out of every minute. I hope anyone else reading this will find the film as richly rewarding as I did - feel free to message me with all your takes to keep the conversation going! :)

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“There’s so little I can do...”

ADAM DRIVER | ANNETTE (2021)

part 2 of 2 requested by @lumberjack00fantasies .

107 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@lgbtqcreators creator bingo — colour

“you are kind of a gay nerd.”

“shut up, rugby lad.”

1K notes

·

View notes