Text

Week 10: “Just turn off the screen lil bro” & the 4 great evils of the internet

If this unit has taught me anything it’s that the internet in general is an excellent place for people from vastly different walks of life to communicate with one another and share the viewpoints from many different perspectives.

However, there can never truly be anything good in this world, as unfortunately humans sometimes have a tendency to just be mean to each other for no apparent reasons.

How to be mean online for dummies

Most instances of online harassment fall under one of 4 main categories: Flaming, Trolling, Cyberbullying and Doxxing.

Flaming: formally described as direct, hostile emotional expressions by Andersen in 2021.

Trolling is one of the more sinister actions one could take online, as they are provocative, aggressive and disruptive messages, but being posted under a mask of innocence and sincerity.

Cyberbullying is often more focused and personal, as most of the time the aggressor knows the victim in real life, or at least has personal info on them.

Defined aggressive and intentional acts carried out by a group or individual, using electronic forms of contact, repeatedly and over time against a victim who cannot easily defend him or herself (Smith et al. 2008).

Doxxing is potentially the most malicious form of online harassment, as this involves publishing private / identifying information (name, bank info, address,...) of an individual on the internet without their knowledge or permission (Chen, Cheung & Chan 2019). Out of all of these, doxxing is most likely to get you tangled up with the law.

“Just turn off the screen lil bro”

Even though online harassment is becoming more and more prevalent with each passing day, currently most governmental entities do not have many laws set in place to protect individuals from harm.

As such, many people have expressed opinions that the only way to protect yourself from online harassment is to not be online at all. While this can be effective in some specific cases, it’s not exactly an universally-applicable advice, as sometimes trolling, flaming, cyberbullying and doxxing do not exist in a vacuum, but rather as extensions of the harassment that already takes place against the same individual in real life.

References

Andersen, IV 2021, ‘Hostility online: Flaming, trolling, and the public debate’, First Monday, vol. 26, no. 3.

Smith, PK, Mahdavi, J, Carvalho, M, Fisher, S, Russell, S & Tippett, N 2008, ‘Cyberbullying: its nature and impact in secondary school pupils’, Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, vol. 49, no. 4, England, pp. 376–85, viewed 9 November 2024,

<https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18363945>.

Chen, M, Cheung, A & Chan, K 2019, ‘Doxing: What Adolescents Look for and Their Intentions’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 16, no. 2, p. 218.

0 notes

Text

Week 9: Gaming is the glue that holds humanity together

Throughout human history, one of the most often overlooked aspects of civilization has always been our love for entertainment, and most importantly, games. While a song can be sung by multiple singers at once, and a painting can be a collaboration between multiple artists, there is quite honestly nothing else that can bring people together the way a game does.

The earliest ever recorded instance of a game was The Royal Game of Ur, created in ancient Mesopotamia. This intricately designed board game was at a point so popular among the population, that it somehow became an object of spiritual significance, and fortune tellers would walk around town with a box of The Royal Game of Ur in hand.

"Instead of seeing randomness, people saw the invisible hand of the spiritual realm. Landing on the Waters of Chaos in senet was no random event but a message from a god, a ghost, or even your own soul" (Donovan 2017, p. 16).

Fast forward a few thousand years, and while we aren’t really trying to communicate with the dead through League of Legends or anything (you’re welcomed to try though), games still hold a very important role in bringing people together, even more so now with the power of the internet and an interconnected world.

Even though some games can be played alone, the core essence of gaming has always been to bring together people from all different walks of life, and to focus on the only thing that matters: having fun. Even when some games are designed to be singleplayer experiences, communities can still form around them as like minded individuals flock together to share their own unique experiences with a game.

Another key aspect of gaming is that, within the confines of the digital arenas of video games, nothing else really matters. Noone really cares about your age, your nationality, your ethnicity, or your social class. To everyone else, you’re just the avatar that you’ve chosen to represent you, and what truly matters is what you can do within the system laid down by a game, a system that everyone abides to.

Lastly, even if video games have became much more mainstream over the last few years, in some parts of society, there still exists a a negative connotation attached to gaming, but it is through this attitude that gamers have banded together, forming communities built around their hobby and creating a welcoming aura of mutual empathy for each other, a trait that is heavily reminiscence of counterculture movements and outcast groups of the past (Steltenpohl 2020).

References

Donovan, T 2017, It’s All a Game : the History of Board Games from Monopoly to Settlers of Catan, Thomas Dunne Books, New York, p. 16.

Steltenpohl, CN 2020, ‘Exploring online and gaming communities through community psychology’, Thesis Commons (OSF Preprints), Center for Open Science.

0 notes

Text

Week 8: Is this the real life? Is this just…Filters?

The predecessor to filters

The concept of Augmented Reality (A.R for short) was first introduced to the public in 1968 by Ivan Sutherland, widely regarded as the father of modern computer graphics. He created a wearable display system that could allow viewers to look at digital graphics. This device laid the foundations for VR goggles down the line.

After its initial invention, A.R technology did not see a lot of use for a few decades, as most companies saw it as little more than a novelty, because of the impracticality and overall high cost to implement.

That all changed in the early 2010s, in the most unexpected of places.

In 2011, the toy line Skylanders was unveiled to the public, utilizing Near Field Communication (N.F.C) technology to allow players to scan physical figures and use them in video games. This was a big out hit, and soon after, many big brands joined in the toys-to-life trend, including Disney Infinity in 2013 and LEGO Dimensions in 2015.

The next step in the evolution of this trend was heavily reliance on A.R, as public interest shifted from bringing physical toys into the digital world, to bringing digital characters into the real world.

Even though the toys-to-life trend did not last too long, it completely changed the game, and helped usher in a new age for A.R technology, as more companies started to see its potential, which led to…

Filters taking over the world

The first instance of “filters” was created in 2015 by Snapchat. While they may be considered a basic feature now, they were a revolutionary piece of technology at the time. Filters alone pretty much carried Snapchat into the most used social media platforms conversation.

The internet had a field day with these filters, which were viewed as just for fun, with ones turning users into animals getting a lot of attraction particularly.

However, it didn’t take long for some people to realize that these filters could be used to alter your face in such a way that you could look more conventionally attractive.

And once again, A.R technology completely changed the game. However, it’s debatable whether that was for the better, or for worse…

As beautification filters exploded in popularity, beauty eventually became homogenized, and the things that once set us apart and made us beautiful in our own ways became unwanted features, things that could be removed and replaced with one simple button, all at the low low cost of your self-esteem.

The negative impact of constant exposure to beautification filters have been the topic of many research papers, and most of them came to the same consensus that the pipeline of using filters can lead users to detest their own features, as well as feeling pressured to conform to one specific image of perception, which often does not even align with their true self, the one that has been buried by dysmorphia and dissatisfaction with oneself (Barker 2020)

References

Barker, J 2020, ‘Making-up on mobile: The pretty filters and ugly implications of Snapchat’, Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 207–221.

Javornik, A 2016, ‘The Mainstreaming of Augmented Reality: A Brief History’, Harvard Business Review, viewed <https://hbr.org/2016/10/the-mainstreaming-of-augmented-reality-a-brief-history>.

I.R. Dijkslag, L. Block Santos, Irene, G & Ketelaar, P 2024, ‘To beautify or uglify! The effects of augmented reality face filters on body satisfaction moderated by self-esteem and self-identification’, Computers in human behavior, vol. 159, Elsevier BV, pp. 108343–108343.

0 notes

Text

Week 7 : Body Modification: The Cosmetic Gaze

Body modification, an enduring aspect of human culture, has long been intertwined with the desire to alter and enhance physical appearance. From ancient tattoos and piercings to modern-day cosmetic procedures and digital filters, the human body has served as a canvas for self-expression. Body modification is a global phenomenon, practiced in diverse forms and for various reasons (Barker & Barker, 2002, p. 92). Examples from around the world include nose piercings associated with Hinduism, neck elongation in Thailand and some African cultures, henna tattooing in Southeast Asia and the Middle East, tooth filing in Bali, lip piercing and earlobe stretching in parts of Africa, and both male and female circumcision in numerous regions (Larkin, 2004; Barker & Barker, 2002; Bendle, 2004). These practices reflect the cultural, religious, and social significance attached to body modification in different societies.

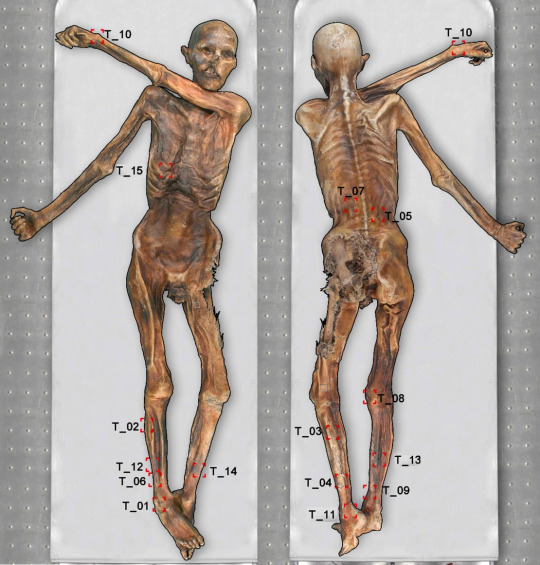

One of the earliest known instances of body modification belongs to Ötzi the Iceman, a 5,300-year-old mummified body discovered in the Alps. Ötzi's body bore 61 carbon pigment tattoos, possibly indicating social status or involvement in ritualistic practices (Samadelli et al., 2015). These markings reflect the deep historical roots of body modification and its significance in human identity.

The concept of body modification extends beyond mere aesthetics; it often carries deeper cultural, social, and personal meanings. In contemporary society, the term "body art" is commonly associated with artists who use their bodies as both subject and medium, producing works that challenge societal norms and explore themes of identity, gender, and vulnerability. Artists such as Marina Abramović and Chris Burden have pushed the boundaries of body art, making their physical bodies central to their creative expression (Vergine, 1974). This practice highlights the body as a site of both artistic creation and social commentary.

Nowadays, with the increasing number of body modification practitioners, the practice has become more normalized and widely accepted. This normalization extends to various forms of modification, including tattoos, piercings, and plastic surgery. Many individuals use these methods to alter, "correct," or "perfect" certain aspects of their appearance, often viewing their bodies as canvases for creative self-expression. While a desire to enhance body image motivates some, this is not the case for everyone who engages in body modification. For many, the appeals of body modification stems from a desire for personal expression or the wish to challenge conventional beauty norms. Some embrace it as a form of fashion, using their bodies to reflect their inner selves and live authentically through their chosen aesthetics (Kang & Jones 2007). One recent study suggests that individuals who were moderately to heavily tattooed have “an increased sense of self-confidence after having pierced or tattooed their bodies” (Carroll & Anderson 2002: 628). However, there is still stigma associated with several types of body modification, including scarification, tattoos, and body piercings. The body is considered sacrosanct by some, who consider it a gift from a higher power. In their perspective, altering the body through modification undermines its natural state and defies its intended sanctity. So what do you think about it?

References

2024, Researchgate.net, viewed 1 November 2024, <https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Matt-Lodder/publication/282667817_Body_Art_Body_Modification_as_Artistic_Practice/links/5617ac5408aee135b3b23ef0/Bo>.

Bradley University 2016, ‘Bradley University: Body Modification & Body Image’, Bradley.edu, viewed <https://www.bradley.edu/sites/bodyproject/disability/modification/>.

Samadelli, M, Melis, M, Miccoli, M, Vigl, EE & Zink, AR 2015, ‘Complete mapping of the tattoos of the 5300-year-old Tyrolean Iceman’, Journal of Cultural Heritage, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 753–758, viewed

0 notes

Text

Week 6 : The slow fashion movement and how the media influences it..

Today, fashion is full of contradictions. People express that they are interested in sustainability, but continue to seek out fast inexpensive fashions (Johansson, 2010). Consumers have embraced fast fashion, seduced by cheap versions of styles that graced the catwalks of Milan and Paris in the previous weeks (Wood, 2009). However, this convenience comes at a high price to both the environment and the people involved in the production process. Fast fashion is linked to overconsumption, as inexpensive clothing tempts consumers to buy more than they need, often discarding garments after just a few wears.

Fast Fashion vs. Slow Fashion

Over the past decade, the fast fashion model has flourished. Brands churn out the latest looks at breakneck speeds, allowing consumers to stay "in trend" for minimal cost. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the slow fashion movement promotes a more sustainable and ethical approach to fashion. This movement was pioneered by Kate Fletcher in 2007, drawing inspiration from the "slow food" movement, which emphasizes responsibility in food production and consumption. Sustainability is increasingly becoming a core consideration for the apparel industry, affecting strategy, operations, workforce engagement, and connection to consumers and communities (Siegel et al., 2012). While slow fashion garments may be more expensive upfront, they are designed to last longer, both in terms of durability and style.

Social Media’s Role in the Slow Fashion Movement

In today’s digital age, social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube play a significant role in shaping consumer preferences and promoting different fashion trends. Influencers, in particular, have a tremendous impact on what their followers buy, making them key players in the fashion industry. Influencers have the special ability to develop stronger psychological ties with their followers because they share more intimate content that centers on their interests and way of life (Audrezet et al. 2020). Given this, there are numerous ways an influencer may use their platform to spread the word about the slow fashion movement.

References

1.5 Lifestyle 2024, ‘Sustainable vs. Fast Fashion: The role of social media | 1.5° Lifestyles’, 1.5° Lifestyles, viewed 9 November 2024, https://onepointfivelifestyles.eu/blog/sustainable-vs-fast-fashion-the-role-of-social-media. Audrezet, A, de Kerviler, G & Guidry Moulard, J 2020, ‘Authenticity under threat: When Social Media Influencers Need to Go beyond self-presentation’, Journal of Business Research, vol. 117, no. 1, pp. 557–569. Brewer, MK 2019, ‘Slow Fashion in a Fast Fashion World: Promoting Sustainability and Responsibility’, Laws, vol. 8, no. 4, p. 24, viewed https://www.mdpi.com/2075-471X/8/4/24. Pookulangara, S & Shephard, A 2013, ‘Slow Fashion Movement: Understanding Consumer Perceptions—An Exploratory Study’, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 200–206, viewed https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2012.12.002.

0 notes

Text

Week 5: Digital Citizenship and Platformization

Digital Citizenship

As we move more and more into the digital age, it has become tremendously more important to be responsible for our actions online, and abide by the rules and guidelines set forth by moderators, just as we would in real life.

A relatively new term that has risen in popularity recently within social media circles is “Digital Citizenship”, which values qualities such as exhibiting safe, legal, and ethical online behavior, as well as contributing productively to virtual communities (Zhong & Zheng 2023.

Generally speaking, there are a lot of overlapping qualities between being a good digital citizen and being a good citizen in real life, such as not overstepping boundaries, respect the authorities, and most importantly, not going out of your way to cause harm to and other people (something that the internet as a whole still struggles with).

Platformization

The term “platform” is one that has had many different meanings throughout history. What initially started out as a way to describe raised surfaces commonly seen in many infrastructures, is now being used widely online as a metaphorical stage one could use to address an audience, while also voicing their own personal beliefs.

The term “platformization” does not describe a thing, but rather a process. In the words of Poell, Nieborg & van Dijck in 2019, it is "the penetration of ifrastructures, economic processes and governmental frameworks of digital platforms in different economic sectors and spheres of life, as well as the reorganisation of cultural practices and imaginations around these platforms."

References

Zhong, J & Zheng, Y 2023, ‘“What It Means to be a Digital Citizen”: Using concept mapping and an educational game to explore children’s conceptualization of digital citizenship’, Heliyon, vol. 9, no. 9.

Poell, T, Nieborg, D & van Dijck, J 2019, ‘Platformisation’, Internet Policy Review, vol. 8, no. 4, p. 1.

0 notes

Text

Week 4 : Reality TV show and the “ordinary celebrities”

When it comes to TV shows, reality shows have long been considered a "weird" and "obscure" form of entertainment. With its first making an appearance in the 90s as a phenomenon, broadcasters have been at odds regarding the primary purpose of the medium in terms of providing entertainment.

Reality television presents viewers with a chance to break away from the routine of their own lives, escape the challenges and burdens of their own situations, and find avenues for emotional catharsis. As we immerse ourselves in the trials and conflicts of others while watching, we can momentarily set aside our own circumstances. It's common to experience thoughts like, "Well, my life isn't so bad after all," or even ponder, "Even someone as glamorous and affluent as so-and-so has their own struggles."

Beyond its genuine portrayal of real-life situations, a huge factor in the surge of reality television was the inclusion of interactive components. These elements engage a live audience or viewers at home, directly involving them in the program as respondents or judges of the activities showcased on the show creating a “connection” (Hill, 2005, p. 21). And thus this creates a new interest in the reality show genre featuring famous artists in general. For instance, psychologist María Cartagena, as cited by Aceprensa, highlights this : "The primary motivation for our viewership of reality TV likely lies in our strong identification with, interest in, or empathy for one participant or another." When reality shows unveil the daily lives of individuals, audiences can place themselves in the depicted scenarios, contemplating their own responses and pondering the best course of action in such circumstances.

Shows like “Keeping up with the Kardashians”, “The Simple Life”, “Nice To Meet You”, etc are the best examples when it comes to “ordinary celebrities”. With the majority of personalities featured on these shows being either established celebrities or well-known socialites, viewers often perceive them as “stars”. As the television screen showcases glimpses into their daily lives, it fuels our intrigue and fascination, elevating our curiosity to new heights. For example, viewers who like watching Kourtney and Kim Kardashian spar might have sisters of their own. Therefore, they can feel understood or even be able to navigate their own relationships after benefiting from being a spectator by watching two people in the same family dynamic as them, or at least one that is comparable. Even if you might not have any similarities with Georgina Rodríguez, the main character in "I Am Georgina," it's possible that observing her day-to-day activities will teach viewers something about the human condition, allow them to empathize with her, and put them in her shoes.

References

LCMHC, AGM, MA 2021, ‘The Psychology of Reality TV’, Medium, viewed <https://medium.com/@wellwaycounseling/the-psychology-of-reality-tv-434144a76088>.

Aceprensa 2023, ‘Beyond the gossip: Why reality TV is so popular’, Aceprensa, viewed <https://www.aceprensa.com/english/beyond-the-gossip-why-reality-tv-is-so-popular/>.

Hill, A 2005, Reality Tv : Audiences and Popular Factual Television, Routledge, London ; Nueva York, p. 21.

0 notes

Text

Week 3: Public Sphere/ The “Public Sphere”. Habermas, and social media

The term “Public Sphere” was originally coined by German philosopher Jürgen Habermas in the book “Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit. Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft” (The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society), released in 1962. He defined it as “made up of private people gathered together as a public and articulating the needs of society with the state” (Soules 2007).

Two years later, Habermas would expand on this definition, explaining the public sphere as “a realm of our social life in which something approaching public opinion can be formed.” (Habermas 1964)

Within the last decade, with the rampant rise of social media platforms, the term “public sphere” has been a hot topic for debate among media professionals, with some arguing that these platforms serve as the modern equivalent of public spheres.

Within these debates, the most interesting argument I came across was that social media platforms were not exactly public spheres, but rather an evolution of Habermas’s original concept, as these platforms host a wide variety of “micro-publics” in the form of communities. Examples of these “micro-publics” would be Facebook groups, Reddit subreddits, or Tumblr blogs. Due to the widely accessible nature of social media, anyone with access to the internet can join in discussions surrounding any topic, while also interacting with other people who are also interested in these conversations.

One of the most prominent scholars in the “social media as public spheres” debate was, surprisingly, Jürgen Habermas himself. A full 60 years after the original book, he released a sequel titled “A New Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere and Deliberative Politics” in 2020, examining the terms he once put forth under a new lens with social media.

Discussing social media platforms as a potential next step of the public sphere, Habermas proposed a very interesting argument :

“While social media platforms are often seen as something that checks all the boxes for a public sphere, they are always undermined by the fact that most of them run on algorithms, making it easy to form an echo chamber around yourself and only interact with people who share the same views. Eventually, all participants will fall into various groups that have the same values and beliefs.”

REFERENCES

Habermas, J 1964, ‘The Public Sphere: An Encyclopedia Article (1964)’, New German Critique, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 49–55, viewed <https://www.jstor.org/stable/487737>.

Soules, M 2007, ‘Jürgen Habermas and the Public Sphere’, Media-studies.ca, viewed <https://www.media-studies.ca/articles/habermas.htm>.

1 note

·

View note