Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The California Gold Rus

The California Gold Rush was sparked by the discovery of gold nuggets in the Sacramento Valley in early 1848 and was arguably one of the most significant events to shape American history during the first half of the 19th century. As news spread of the discovery, thousands of prospective gold miners traveled by sea or over land to San Francisco and the surrounding area; by the end of 1849, the non-native population of the California territory was some 100,000 (compared with the pre-1848 figure of less than 1,000). A total of $2 billion worth of precious metal was extracted from the area during the Gold Rush, which peaked in 1852.

On January 24, 1848, James Wilson Marshall, a carpenter originally from New Jersey, found flakes of gold in the American River at the base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains near Coloma, California. At the time, Marshall was working to build a water-powered sawmill owned by John Sutter, a German-born Swiss citizen and founder of a colony of Nueva Helvetia (New Switzerland, which would later become the city of Sacramento). As Marshall later recalled of his historic discovery: “It made my heart thump, for I was certain it was gold.” Days after Marshall’s discovery at Sutter’s Mill, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, ending the Mexican-American War and leaving California in the hands of the United States—a remarkable twist of fate with important ramifications for an America eager for westward expansion. At the time, the population of the territory consisted of 6,500 Californios (people of Spanish or Mexican descent); 700 foreigners (primarily Americans); and 150,000 Native Americans (Barely half the number that had been there when Spanish settlers arrived in 1769). Sutter, in fact, had enslaved hundreds of Native Americans and used them as a free source of labor and makeshift militia to defend his territory and expand his empire.

Though Marshall and Sutter tried to keep news of the discovery under wraps, word got out, and by mid-March at least one newspaper was reporting that large quantities of gold were being turned up at Sutter’s Mill. Though the initial reaction in San Francisco was disbelief, storekeeper Sam Brannan set off a frenzy when he paraded through town displaying a vial of gold obtained from Sutter’s Creek. By mid-June, shops and businesses stood empty, as some three-quarters of the male population of San Francisco had abandoned the city for the gold mines, and the number of miners in the area ballooned to some 4,000 by August. As news reports—many wildly overblown—of the easy fortunes being made in California spread worldwide, some of the first migrants to arrive were those from lands accessible by boat, such as Oregon, the Sandwich Islands (now Hawaii), Mexico, Chile, Peru and China.

When the news reached the East Coast, press reports were initially skeptical. Gold fever kicked off nationwide in earnest, however, after December 1848, when President James K. Polk announced the positive results of a report made by Colonel Richard Mason, California’s military governor, in his inaugural address.

Throughout 1849, people around the United States (mostly men) with gold fever borrowed money, mortgaged their property or spent their life savings to make the arduous journey to California. In pursuit of the kind of wealth they had never dreamed of, they left their families and hometowns. In turn, women left behind took on new responsibilities such as running farms or businesses and caring for their children alone. Thousands of would-be gold miners, known as 49ers for the year they arrived, traveled overland across the mountains or by sea, sailing to Panama or even around Cape Horn, the southernmost point of South America. By the end of the year, the non-native population of California was estimated at 100,000, (as compared with 20,000 at the end of 1848 and around 800 in March 1848). To accommodate the needs of the 49ers, gold mining towns had sprung up all over the region, complete with shops, saloons, brothels and other businesses seeking to make their own gold Rush fortune. The overcrowded chaos of the mining camps and towns grew ever more lawless, including rampant banditry, gambling, alcoholism, prostitution and violence. San Francisco, for its part, developed a bustling economy and became the central metropolis of the new frontier.

The Gold Rush undoubtedly sped up California’s admission to the Union as the 31st state. In late 1849, California applied to enter the Union with a constitution that barred the Southern system of racial slavery, provoking a crisis in Congress between proponents of slavery and anti-slavery politicians. According to the Compromise of 1850, proposed by Kentucky’s Senator Henry Clay, California was allowed to enter as a free state, while the territories of Utah and New Mexico were left to decide the legal status of slavery for themselves.

After 1850, the surface gold in California largely disappeared, even as miners continued to arrive. Mining had always been difficult and dangerous labor, and striking it rich required good luck as much as skill and hard work. Moreover, the average daily take for an independent miner working with his pick and shovel had by then sharply decreased from what it had been in 1848. As gold became more and more difficult to reach, the growing industrialization of mining drove more and more miners from independence into wage labor. The new technique of hydraulic mining, developed in 1853, brought enormous profits but destroyed much of the region’s landscape. Though gold mining continued throughout the 1850s, it had reached its peak by 1852, when some $81 million was pulled from the ground. After that year, the total take declined gradually, leveling off to around $45 million per year by 1857. Settlement in California continued, however, and by the end of the decade the state’s population was 380,000.

New mining methods and the population boom in the wake of the California Gold Rush permanently altered the landscape of California. The technique of hydraulic mining brought enormous profits but destroyed much of the region’s landscape. Dams designed to supply water to mine sites in summer altered the course of rivers away from farmland, while sediment from mines clogged others. The logging industry in the area was born from the need to construct extensive canals and feed boilers at mines, further consuming natural resources.

In 1884, hydraulic mining was outlawed by court order, and soon agriculture became the dominant industry in California, and it remains so today. While a few mines and Gold Rush towns remain, much of the heritage of that era is preserved at places such as Bodie State Historic Park, a decaying ghost town, and at Marshall Gold Discovery State Historic Park, where Sutter’s Mill once stood.

0 notes

Text

The Munich Massacre

In what became known as the Munich Massacre, eight terrorists wearing tracksuits and carrying gym bags filled with grenades and assault rifles, breached the Olympic Village at the Summer Games in Munich before dawn on September 5, 1972. The terrorists, associated with Black September, an extremist faction of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, entered the apartment complex where Israeli athletes were staying. Once inside, they murdered two members of the Israeli team and took nine others hostage. Audiences around the world then watched in horror as the international nightmare unfolded on live TV.

The terrorists demanded the release of 234 Arab prisoners from Israeli jails, as well as two German terrorists held in West German custody. When authorities attempted to rescue the hostages after a 23-hour standoff, all the hostages, one West German police officer and five Black September members were killed. More than 900 million viewers watched coverage of the terrorist attack on TV, including the now iconic sight of a black ski mask-clad terrorist on the balcony. It was the first time an act of terror was broadcast live and took place during a major global sporting event. Hosting its first Olympics in Germany since Adolf Hitler’s Nazi propaganda and racism-laden 1936 Summer Games in Berlin, the West German government had been looking to highlight its democracy and downplay any military presence. Hailing the event as “the Games of Peace and Joy,” and “the Cheerful Games,” West Germany eschewed uniformed soldiers and police for unarmed guards. Less than 30 years after the end of World War II, when approximately 6 million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust, Israel entered the Munich Olympics with its biggest-ever team of officials and athletes. According to the book One Day in September by Simon Reeve, "several of them (were) older Eastern Europeans still bearing physical and mental scars from Nazi concentration camps." Israeli officials had reportedly voiced concern about the lack of security at the Games and a 1972 New York Times report pointed to "glaring" precautionary deficiencies. The way the terrorists were able to take deadly advantage of easy access to the village would change security protocols and preparation for future Olympics.

Ten days into the Games, on September 5, 1972, under the cloak of darkness, the terrorists stormed the Israeli team's quarters at 4:30 a.m., having been helped over a wire fence by athletes sneaking in after a night out who mistook them for fellow Olympians. Upon breaching the Israeli dorm, wrestling coach Moshe Weinberg and weightlifter Yossef Romano were killed almost immediately. Horrifyingly, Romano, according to the Associated Press, was castrated and Weinberg’s body was thrown to the street. Some escaped, but nine Israelis were quickly taken hostage, including weightlifters David Berger, who was born in America, and Ze’ev Friedman, wrestlers Eliezer Halfin and Mark Slavin, track and field coach Amitzur Shapira, sharpshooting coach Kehat Shorr, fencer Andre Spitzer, weightlifting judge Yakov Springer and wrestling referee Yossef Gutfreund. A 9 a.m. deadline was set for the terrorists’ political prisoner release demands—not meeting it, they said, would result in one hostage being executed every hour. With no counter-terror unit in place, the West Germans took control of the negotiations, with Munich's police chief as well as Libyan and Tunisian ambassadors to Germany, attempting to deal with the kidnappers. According to the Guardian, the terrorists rejected the offer of "an unlimited amount of money" for the release of the hostages, but did extend their deadline multiple times. At least one attempt at a rescue in the athletes’ dorm was botched when the terrorists were able to view officers approaching on TV—their electricity hadn’t been cut off.

Israel's immediate response was that there would be no negotiations. "If we should give in, then no Israeli anywhere in the world can feel that his life is safe," Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir said at the time. With negotiations failing, the members of Black September demanded transport to Cairo and, with the hostages, were moved via two helicopters to Fürstenfeldbruck air base, about 15 miles away, where a jet was waiting. In a rescue attempt-turned bloodbath, German snipers, with no sharpshooting experience, inadequate gear, bad intelligence and no means of communication with each other, opened fire on the kidnappers. The terrorists returned fire, killing Anton Flieger Bauer, a German policeman positioned in a control tower. All nine hostages, bound in the helicopters, were killed by gunfire and a grenade. Black September leader Luttie Afif and four other terrorists were also left dead, while three were captured alive. Following the attack, the Games were suspended for 34 hours, with a memorial service held September 6 in Olympic Stadium that was attended by 3,000 athletes and 80,000 spectators. The rest of the Israeli team left Munich, as did Mark Spitz, the Jewish American swimmer who had already won seven gold medals at the Games, and the Egyptian, Philippine and Algerian teams, among others. A month later, the three captured terrorists were released in a hostage exchange after the hijacking of Lufthansa Flight 615 and received a “hero’s welcome” upon arrival in Libya, according to Reuters.

Meir and Israel, meanwhile, responded with Operation Wrath of God, a covert Mossad mission to kill the masterminds behind the Munich massacre. Several suspects were assassinated in the coming months, but the mission was suspended when an innocent man was mistakenly killed in Norway in 1973. The target of that shooting, Black September Chief of Operations Ali Hassan Salameh, was assassinated by car bomb in 1979 in the operation’s final mission.

0 notes

Text

Energy Crisis (1970s)

By the early 1970s, American oil consumption—in the form of gasoline and other products—was rising even as domestic oil production was declining, leading to an increasing dependence on oil imported from abroad. Despite this, Americans worried little about a dwindling supply or a spike in prices, and were encouraged in this attitude by policymakers in Washington, who believed that Arab oil exporters couldn’t afford to lose the revenue from the U.S. market. These assumptions were demolished in 1973, when an oil embargo imposed by members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) led to fuel shortages and sky-high prices throughout much of the decade.

In 1948, the Allied powers had carved land out of the British-controlled territory of Palestine in order to create the state of Israel, which would serve as a homeland for disenfranchised Jews from around the world. Much of the Arab population in the region refused to acknowledge the Israeli state, however, and over the next decades sporadic attacks periodically erupted into full-scale conflict. One of these Arab-Israeli wars, the Yom Kippur War, began in early October 1973, when Egypt and Syria attacked Israel on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur. After the Soviet Union began sending arms to Egypt and Syria, U.S. President Richard Nixon began an effort to resupply Israel. In response, members of the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) reduced their petroleum production and proclaimed an embargo on oil shipments to the United States and the Netherlands, the main supporters of Israel. Though the Yom Kippur War ended in late October, the embargo and limitations on oil production continued, sparking an international energy crisis. As it turned out, Washington’s earlier assumption that an oil boycott for political reasons would hurt the Persian Gulf financially turned out to be wrong, as the increased price per barrel of oil more than made up for the reduced production. In the three frenzied months after the embargo was announced, the price of oil shot from $3 per barrel to $12. After decades of abundant supply and growing consumption, Americans now faced price hikes and fuel shortages, causing lines to form at gasoline stations around the country. Local, state and national leaders called for measures to conserve energy, asking gas stations to close on Sundays and homeowners to refrain from putting up holiday lights on their houses. In addition to causing major problems in the lives of consumers, the energy crisis was a huge blow to the American automotive industry, which had for decades turned out bigger and bigger cars and would now be outpaced by Japanese manufacturers producing smaller and more fuel-efficient models. Though the embargo was not enforced uniformly in Europe, the price hikes led to an energy crisis of even greater proportions than in the United States. Countries such as Great Britain, Germany, Switzerland, Norway and Denmark placed limitations on driving, boating and flying, while the British prime minister urged his countrymen only to heat one room in their homes during the winter.

The oil embargo was lifted in March 1974, but oil prices remained high, and the effects of the energy crisis lingered throughout the decade. In addition to price controls and gasoline rationing, a national speed limit was imposed and daylight-saving time was adopted year-round for the period of 1974-75. Environmentalism reached new heights during the crisis, and became a motivating force behind policymaking in Washington. Various acts of legislation during the 1970s sought to redefine America’s relationship to fossil fuels and other sources of energy, from the Emergency Petroleum Allocation Act (passed by Congress in November 1973, at the height of the oil panic) to the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975 and the creation of the Department of Energy in 1977.

As part of the movement toward energy reform, efforts were made to stimulate domestic oil production as well as to reduce American dependence on fossil fuels and find alternative sources of power, including renewable energy sources such as solar or wind power, as well as nuclear power. However, after oil prices collapsed in the mid-1980s and prices dropped to more moderate levels, domestic oil production fell once more, while progress toward energy efficiency slowed and foreign imports increased.

0 notes

Text

The Watergate Scandal

The Watergate scandal began early in the morning of June 17, 1972, when several burglars were arrested in the office of the Democratic National Committee, located in the Watergate complex of buildings in Washington, D.C. This was no ordinary robbery: The prowlers were connected to President Richard Nixon’s reelection campaign, and they had been caught wiretapping phones and stealing documents. Nixon took aggressive steps to cover up the crimes, but when Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein revealed his role in the conspiracy, Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974. The Watergate scandal changed American politics forever, leading many Americans to question their leaders and think more critically about the presidency.

The origins of the Watergate break-in lay in the hostile political climate of the time. By 1972, when Republican President Richard M. Nixon was running for reelection, the United States was embroiled in the Vietnam War, and the country was deeply divided. A forceful presidential campaign therefore seemed essential to the president and some of his key advisers. Their aggressive tactics included what turned out to be illegal espionage. In May 1972, as evidence would later show, members of Nixon’s Committee to Re-Elect the President (known derisively as CREEP) broke into the Democratic National Committee’s Watergate headquarters, stole copies of top-secret documents and bugged the office’s phones. The wiretaps failed to work properly, however, so on June 17 a group of five burglars returned to the Watergate building. As the prowlers were preparing to break into the office with a new microphone, a security guard noticed someone had taped over several of the building’s door locks. The guard called the police, who arrived just in time to catch them red-handed. It was not immediately clear that the burglars were connected to the president, though suspicions were raised when detectives found copies of the reelection committee’s White House phone number among the burglars’ belongings. In August, Nixon gave a speech in which he swore that his White House staff was not involved in the break-in. Most voters believed him, and in November 1972 the president was reelected in a landslide victory.

It later came to light that Nixon was not being truthful. A few days after the break-in, for instance, he arranged to provide hundreds of thousands of dollars in “hush money” to the burglars. Then, Nixon and his aides hatched a plan to instruct the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to impede the FBI’s investigation of the crime. This was a more serious crime than the break-in: It was an abuse of presidential power and a deliberate obstruction of justice. Meanwhile, seven conspirators were indicted on charges related to the Watergate affair. At the urging of Nixon’s aides, five pleaded guilty to avoid trial; the other two were convicted in January 1973. By that time, a growing handful of people—including Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, trial judge John J. Sirica and members of a Senate investigating committee—had begun to suspect that there was a larger scheme afoot. At the same time, some of the conspirators began to crack under the pressure of the cover-up. Anonymous whistleblower “Deep Throat” provided key information to Woodward and Bernstein. A handful of Nixon’s aides, including White House counsel John Dean, testified before a grand jury about the president’s crimes; they also testified that Nixon had secretly taped every conversation that took place in the Oval Office. If prosecutors could get their hands on those tapes, they would have proof of the president’s guilt. Nixon struggled to protect the tapes during the summer and fall of 1973. His lawyers argued that the president’s executive privilege allowed him to keep the tapes to himself, but Judge Sirica, the Senate committee and an independent special prosecutor named Archibald Cox were all determined to obtain them.

When Cox refused to stop demanding the tapes, Nixon ordered that he be fired, leading several Justice Department officials to resign in protest. (These events, which took place on October 20, 1973, are known as the Saturday Night Massacre.) Eventually, Nixon agreed to surrender some—but not all—of the tapes. Early in 1974, the cover-up and efforts to impede the Watergate investigation began to unravel. On March 1, a grand jury appointed by a new special prosecutor indicted seven of Nixon’s former aides on various charges related to the Watergate affair. The jury, unsure if they could indict a sitting president, called Nixon an “unindicted co-conspirator.” In July, the Supreme Court ordered Nixon to turn over the tapes. While the president dragged his feet, the House Judiciary Committee voted to impeach Nixon for obstruction of justice, abuse of power, criminal cover-up and several violations of the Constitution.

Finally, on August 5, Nixon released the tapes, which provided undeniable evidence of his complicity in the Watergate crimes. In the face of almost certain impeachment by Congress, Nixon resigned in disgrace on August 8, and left office the following day. Six weeks later, after Vice President Gerald Ford was sworn in as president, he pardoned Nixon for any crimes he had committed while in office. Some of Nixon’s aides were not so lucky: They were convicted of very serious offenses and sent to federal prison. Nixon’s Attorney General of the United States John Mitchell served 19 months for his role in the scandal, while Watergate mastermind G. Gordon Liddy, a former FBI agent, served four and a half years. Nixon’s Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman spent 19 months in prison while John Ehrlichman spent 18 for attempting to cover up the break-in. Nixon himself never admitted to any criminal wrongdoing, though he did acknowledge using poor judgment.

His abuse of presidential power had a long-lasting effect on American political life, creating an atmosphere of cynicism and distrust. While many Americans had been deeply dismayed by the outcome of the Vietnam War, and saddened by the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King and other leaders, Watergate added further disappointment to a national climate already soured by the difficulties and losses of the previous decade.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Exxon Valdez Oil Spill

The Exxon Valdez oil spill was a manmade disaster that occurred when Exxon Valdez, an oil tanker owned by the Exxon Shipping Company, spilled 11 million gallons of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound on March 24, 1989. It was the worst oil spill in U.S. history until the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010. The Exxon Valdez oil slick covered 1,300 miles of coastline and killed hundreds of thousands of seabirds, otters, seals and whales. Nearly 30 years later, pockets of crude oil remain in some locations. After the spill, Exxon Valdez returned to service under a different name, operating for more than two decades as an oil tanker and ore carrier.

On the evening of March 23, 1989, Exxon Valdez left the port of Valdez, Alaska, bound for Long Beach, California, with 53 million gallons of Prudhoe Bay crude oil onboard. At four minutes after midnight on March 24, the ship struck Bligh Reef, a well-known navigation hazard in Alaska’s Prince William Sound. The impact of the collision tore open the ship’s hull, causing some 11 million gallons of crude oil to spill into the water. At the time, it was the largest single oil spill in U.S. waters. Initial attempts to contain the oil failed, and in the months that followed, the oil slick spread, eventually covering about 1,300 miles of coastline. Investigators later learned that Joseph Hazelwood, the captain of Exxon Valdez, had been drinking at the time and had allowed an unlicensed third mate to steer the massive ship. In March 1990, Hazelwood was acquitted of felony charges. He was convicted of a single charge of misdemeanor negligence, fined $50,000, and ordered to perform 1,000 hours of community service.

In the months after the Exxon Valdez oil spill, Exxon employees, federal responders and more than 11,000 Alaska residents worked to clean up the oil spill. Exxon played about $2 billion in cleanup costs and $1.8 billion for habitat restoration and personal damages related to the spill. Cleanup workers skimmed oil from the water’s surface, sprayed oil dispersant chemicals in the water and on shore, washed oiled beaches with hot water and rescued and cleaned animals trapped in oil. Environmental officials purposefully left some areas of shoreline untreated so they could study the effect of cleanup measures, some of which were unproven at the time. They later found that aggressive washing with high-pressure, hot water hoses was effective in removing oil, but did even more ecological damage by killing the remaining plants and animals in the process. One of those areas that was oiled but never cleaned is a large shoreline boulder called Mearn’s Rock. Scientists have returned to Mearn’s Rock every summer since the spill to photograph the plants and small critters growing on it. They found that many of the mussels, barnacles and various seaweeds growing on the rock before the spill returned to normal levels about three to four years after the spill.

Prince William Sound had been a pristine wilderness before the spill. The Exxon Valdez disaster dramatically changed all of that, taking a major toll on wildlife. It killed an estimated 250,000 sea birds, 3,000 otters, 300 seals, 250 bald eagles and 22 killer whales. The oil spill also may have played a role in the collapse of salmon and herring fisheries in Prince William Sound in the early 1990s. Fishermen went bankrupt, and the economies of small shoreline towns, including Valdez and Cordova, suffered in the following years. Some reports estimated the total economic loss from the Exxon Valdez oil spill to be as much as $2.8 billion. A 2001 study found oil contamination remaining at more than half of the 91 beach sites tested in Prince William Sound.

The spill had killed an estimated 40 percent of all sea otters living in the Sound. The sea otter population didn’t recover to its pre-spill levels until 2014, twenty-five years after the spill. Stocks of herring, once a lucrative source of income for Prince William Sound fisherman, have never fully rebounded.

In the wake of the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the U.S. Congress passed the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, which President George H.W. Bush signed into law that year. The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 increased penalties for companies responsible for oil spills and required that all oil tankers in United States waters have a double hull. Exxon Valdez was a single-hulled tanker; a double-hull design, by making it less likely that a collision would have spilled oil, might have prevented the Exxon Valdez disaster.

The ship, Exxon Valdez—first commissioned in 1986—was repaired and returned to service a year after the spill in a different ocean and under a different name. The single-hulled ship could no longer transport oil in U.S. waters, due to the new regulations. The ship began running oil transport routes in Europe, where single-hulled oil tankers were still allowed. There it was renamed the Exxon Mediterranean, then the SeaRiver Mediterranean and finally the S/R Mediterranean.

In 2002, the European Union banned single-hulled tankers and the former Exxon Valdez moved to Asian waters. Exxon sold the infamous tanker in 2008 to a Hong Kong-based shipping company. The company converted the old oil tanker to an ore carrier, renaming it the Dong Feng Ocean. In 2010, the star-crossed ship collided with another bulk carrier in the Yellow Sea and was once again severely damaged. The ship was renamed once more after the collision, becoming the Oriental Nicety. The Oriental Nicety was sold for scrap to an Indian company and dismantled in 2012.

0 notes

Text

The Gilded Age

“The Gilded Age” is the term used to describe the tumultuous years between the Civil War and the turn of the twentieth century. The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today was a famous satirical novel by Mark Twain set in the late 1800s, and was its namesake. During this era, America became more prosperous and saw unprecedented growth in industry and technology. But the Gilded Age had a more sinister side: It was a period where greedy, corrupt industrialists, bankers and politicians enjoyed extraordinary wealth and opulence at the expense of the working class. In fact, it was wealthy tycoons, not politicians, who inconspicuously held the most political power during the Gilded Age.

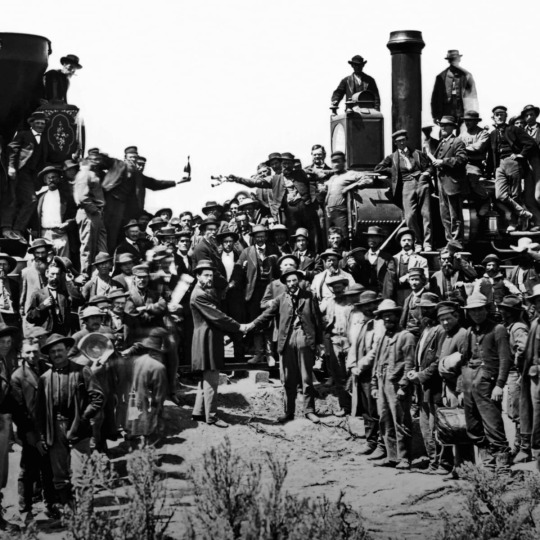

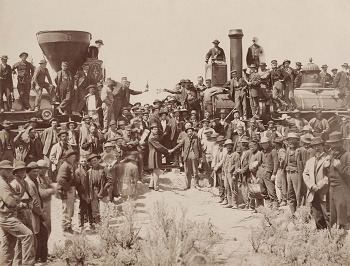

Before the Civil War, rail travel was dangerous and difficult, but after the war, George Westinghouse invented the air brake, which made braking systems more dependable and safer. Soon, the development of Pullman sleeping cars and dining cars made rail travel comfortable and more enjoyable for passengers. It wasn’t long before trains overtook other forms of long-distance travel such as the stagecoach and riding horseback. In 1869, the Transcontinental Railroad was finished and led to rapid settlement of the western United States. It also made it much easier to transport goods over long distances from one part of the country to another. This enormous railroad expansion resulted in rail companies and their executives receiving lavish amounts of money and land—up to 200 million acres, by some estimates—from the United States government. In many cases, politicians cut shady backroom deals and helped create railroad and shipping tycoons such as Cornelius Vanderbilt and Jay Gould. Meanwhile, thousands of African American—many of them former slaves—were hired as Pullman porters and paid a pittance to cater to riders’ every need.

Railroad tycoons were just one of many types of so-called robber barons that emerged in the Gilded Age. These men used union busting, fraud, intimidation, violence and their extensive political connections to gain an advantage over any competitors. Robber barons were relentless in their efforts to amass wealth while exploiting workers and ignoring standard business rules—and in many cases, the law itself. They soon accumulated vast amounts of money and dominated every major industry including the railroad, oil, banking, timber, sugar, liquor, meatpacking, steel, mining, tobacco and textile industries. Some wealthy entrepreneurs such as Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller and Henry Frick are often referred to as robber barons but may not exactly fit the mold. While it’s true they built huge monopolies, often by crushing any small business or competitor in their way, they were also generous philanthropists who didn’t always rely on political ploys to build their empires. Some tried to improve life for their employees, donated millions to charities and nonprofits and supported their communities by providing funding for everything from libraries and hospitals to universities, public parks and zoos.

The Gilded Age was in many ways the culmination of the Industrial Revolution, when America and much of Europe shifted from an agricultural society to an industrial one. Millions of immigrants and struggling farmers arrived in cities such as New York, Boston, Philadelphia, St. Louis and Chicago, looking for work and hastening the urbanization of America. By 1900, about 40 percent of Americans lived in major cities. Most cities were unprepared for rapid population growth. Housing was limited, and tenements and slums sprung up nationwide. Heating, lighting, sanitation and medical care were poor or nonexistent, and millions died from preventable disease. Many immigrants were unskilled and willing to work long hours for little pay. Gilded Age plutocrats considered them the perfect employees for their sweatshops, where working conditions were dangerous and workers endured long periods of unemployment, wage cuts and no benefits.

Wealthy considered themselves America’s royalty and settled for nothing less than estates worthy of that distinction. Some of America’s most famous mansions were built during the Gilded Age such as: Biltmore, located in Asheville, North Carolina, was the family estate of George and Edith Vanderbilt. Construction started on the 250-room chateau in 1889, prior to the couple’s marriage, and continued for six years. The home had 35 bedrooms, 43 bathrooms, 65 fireplaces, a dairy, a horse barn and beautiful formal and informal gardens. The Breakers in Newport, Rhode Island, is another Vanderbilt mansion. It was the summer home of railroad mogul Cornelius Vanderbilt. The Italian-Renaissance style home has 70 rooms, a stable and a carriage house. Rosecliff, also in Newport, was completed in 1902. The oceanfront home was contracted by Theresa Fair Oelrich's and built to resemble the Grand Trianon of Versailles. Today, it’s best known as the backdrop for movie scenes in The Great Gatsby, High Society, 27 Dresses and True Lies. Whitehall, located in Palm Beach, Florida, was the neoclassical winter retreat of oil tycoon Henry Flagler and his wife Mary. The 100,000 square foot, 75-room mansion was completed in 1902 and is now a popular museum.

The industrialists of the Gilded Age lived high on the hog, but most of the working class lived below poverty level. As time went on, the income inequality between wealthy and poor became more and more glaring. While the wealthy lived in opulent homes, dined on succulent food and showered their children with gifts, the poor were crammed into filthy tenement apartments, struggled to put a loaf of bread on the table and often accompanied their children to a sweatshop each morning where they faced a 12-hour (or longer) workday.Some moguls used Social Darwinism to justify the inequality between the classes. The theory presumes that the fittest humans are the most successful and poor people are destitute because they’re weak and lack the skills to be prosperous.

Muckrakers is a term used to describe reporters who exposed corruption among politicians and the elite. They used investigative journalism and the print revolution to dig through “the muck” of the Gilded Age and report scandal and injustice. In 1890, reporter and photographer Jacob Riis brought the horrors of New York slum life to light in his book, How the Other Half Lives, prompting New York politicians to pass legislation to improve tenement conditions. In 1902, McClure Magazine journalist Lincoln Steffens took on city corruption when he penned the article, “Tweed Days in St. Louis.” The article, which is widely considered the first muckraking magazine article, exposed how city officials deceitfully made deals with crooked businessmen to maintain power. Another journalist, Ida Tarbell, spent years investigating the underhanded rise of oilman John D. Rockefeller. Her 19-part series, also published in McClure in 1902, led to the breakup of Rockefeller’s monopoly, the Standard Oil Company. In 1906, activist journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle to expose horrendous working conditions in the meatpacking industry. The book and ensuing public outcry led to the passing of the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act.

It soon became obvious that the huge disparity between the wealthy and poor couldn’t last, and the working class would have to organize to improve their working and living conditions. It was also obvious this wouldn’t happen without some degree of violence. Much of the violence, however, was between the workers themselves as they struggled to agree on what they were fighting for. Some simply wanted increased wages and a better working environment, while others also wanted to keep women, immigrants and blacks out of the workforce. Although the first labor unions occurred around the turn of the nineteenth century, they gained momentum during the Gilded Age, thanks to the increased number of unskilled and unsatisfied factory workers.

On July 16, 1877, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company announced a 10-percent pay cut on its railroad workers in Martinsburg, West Virginia, the second cut in less than eight months. Infuriated and fed up, the workers—with the support of the locals—announced they’d prevent all trains from leaving the roundhouse until their pay was restored. The mayor, the police and even the National Guard couldn’t stop the strike. It wasn’t until Federal troops arrived that one train finally left the station. The strike spread among other railroads, sparking violence across America between the working class and local and federal authorities. At its peak, over 100,000 railroad workers were on strike. Many of the Robber Barons feared an aggressive, all-out revolution against their way of life. Instead, the strike—later known as the Great Upheaval—ended abruptly and was labeled a dismal failure. Yet it showed America’s tycoons there was strength in numbers and that organized labor had the potential to shut down entire industries and inflict major economic and political damage. As the working class continued to use strikes and boycotts to fight for higher wages and improved working conditions, their bosses staged lock-outs and brought in replacement workers known as scabs. They also created blacklists to prevent active union workers from becoming employed elsewhere. Even so, the working class continued to unite and press their cause and often won at least some of their demands. Innovations of the Gilded Age helped usher in modern America. Urbanization and technological creativity led to many engineering advances such as bridges and canals, elevators and skyscrapers, trolley lines and subways. The invention of electricity brought illumination to homes and businesses and created an unprecedented, thriving night life. Art and literature flourished, and the rich filled their lavish homes with expensive works of art and elaborate décor. In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone and made the world a much smaller place for both individuals and businesses. Advances in sanitation and housing, and the availability of better quality food and material goods, improved quality of life for the middle class. But while the middle and upper classes enjoyed the allure of city life, little changed for the poor. Most still faced horrific living conditions, high crime rates and a pitiable existence. Many escaped their drudgery by watching a vaudeville show or a spectator sport such as boxing, baseball or football, all of which enjoyed a surge during the Gilded Age.

Upper-class women of the Gilded Age have been compared to dolls on display dressed in resplendent finery. They flaunted their wealth and endeavored to improve their status in society while poor and middle-class women both envied and mimicked them. Some wealthy Gilded Age women were much more than eye candy, though, and often traded domestic life for social activism and charitable work. They felt a new degree of empowerment and fought for equality, including the right to vote through women’s suffrage groups. Some created homes for destitute immigrants while others pushed a temperance agenda, believing the source of poverty and most family troubles was alcohol. Wealthy women philanthropists of the Gilded Age include: Louise Whitfield Carnegie, wife of Andrew Carnegie, who created Carnegie Hall and donated to the Red Cross, the Y.W.C.A., and other charities. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, wife of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who helped create hotels for women and solicited funds to create the New York Museum of Modern Art. Margaret Olivia Sage, wife of Russell Sage, who after the death of her miserly husband gave away $45 million of her $75 million inheritance to support women’s causes, educational institutions and the creation of the Russell Sage Foundation for Social Betterment, which directly helped poor people. Many women during the Gilded Age sought higher education. Others postponed marriage and took jobs such as typists or telephone switchboard operators. Thanks to a print revolution and the accessibility of newspapers, magazines and books, women became increasingly knowledgeable, cultured, well-informed and a political force to be reckoned with.

Jane Addams is arguably the best-known philanthropist of the Gilded Age. In 1889, she and Ellen Gates Star established a secular settlement house in Chicago known as Hull-House. The neighborhood was a melting pot of struggling immigrants, and Hull-House provided everything from midwife services and basic medical care to kindergarten, day care and housing for abused women. It also offered English and citizenship classes. Addams received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931. Temperance leader Carrie Nation gained notoriety during the Gilded Age for smashing up saloons with a hatchet to bring attention to her sobriety agenda. She was also a strong voice for the suffrage movement. Nation’s belief that alcohol was the root of all evil was partially due to her difficult first marriage to an alcoholic, and her work with women and children displaced or abused by over-imbibing husbands. Convinced God had instructed her to use whatever means necessary to close bars throughout Kansas, she was often beaten, mocked and jailed but ultimately helped pave the way for the 18th Amendment (prohibiting the sale of alcohol) and the 19th Amendment (giving women the right to vote). Many other pivotal events happened during the Gilded Age which changed America’s course and culture. As muckrakers exposed corrupt robber barons and politicians, labor unions and reformist politicians enacted laws to limit their power. The western frontier saw violent conflicts between white settlers and the United States Army against Native Americans. The Native Americans were eventually forced off their land and onto reservations with often disastrous results. In 1890, the western frontier was declared closed.

As drought and depression struck rural America, farmers in the west—who vilified railroad tycoons and wanted a political voice—organized and played a key role in forming the Populist Party. The Populists had a democratic agenda that aimed to give power back to the people and paved the way for the progressive movement, which still fights to close the gap between the wealthy and poor and champion the needy and disenfranchised.

In 1893, both the overextended Philadelphia and Reading Railroad and the National Cordage Company failed, which set off an economic depression unlike any seen before in America. Banks and other businesses folded, and the stock market plunged, leaving millions unemployed, homeless and hungry. In some states, unemployment rose to almost 50 percent.

The Panic of 1893 lasted four years and left lower and even middle-class Americans fed up with political corruption and social inequality. Their frustration gave rise to the Progressive Movement which took hold when President Theodore Roosevelt took office in 1901. Although Roosevelt supported corporate America, he also felt there should be federal controls in place to keep excessive corporate greed in check and prevent individuals from making obscene amounts of money off the backs of immigrants and the lower class. Helped by the muckrakers and the White House, the Progressive Era ushered in many reforms that helped shift away power from robber barons, such as:

trust busting

labor reform

women’s suffrage

birth control

formation of trade unions

increased conservation efforts

food and medicine regulations

tax reform

civil rights

election reform

fair labor standards

By 1916, America’s cities were cleaner and healthier, factories safer, governments less corrupt and many people had better housing, working hours and wages. Fewer monopolies meant more people could pursue the American Dream and start their own businesses. When America entered World War I in 1917, the Progressive Era and any remnants of the Gilded Age effectively ended as the country’s focus shifted to the realities of war. Most robber barons and their families, however, remained wealthy for generations.

Even so, many bequeathed much of their wealth, land and homes to charity and historical societies. And progressives continued their mission to close the gap between the wealthy and poor and champion the needy and disenfranchised.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 1992 Los Angeles Riots

The 1992 Los Angeles riots—also called the Los Angeles uprising—sprung from years of rising tensions between the LAPD and the city’s African Americans, highlighted by the 1991 videotaped beating of motorist Rodney King. On April 29, 1992, anger boiled over after four LAPD officers were found not guilty of assaulting King, leading to several days of widespread violence, looting and arson throughout L.A. By May 3, thousands of National Guardsmen and federal troops had largely curbed the uprising, which left more than 60 people dead and produced about $1 billion in damage.

The 1980s brought rising unemployment, gang activity, drugs and violent crime to the poorer neighborhoods of Los Angeles. Aggressive efforts to exert control by the Los Angeles Police Department fostered a belief among minority communities that its officers were not held liable for abusive police actions. In August 1988, as part of LAPD Chief Daryl Gates’s “Operation Hammer” drug sweeps, more than 80 officers tore apart a pair of apartment buildings on Dalton Street in South L.A., leaving dozens homeless. In January 1990, a skirmish between the LAPD and Nation of Islam members following a traffic stop resulted in the death of 27-year-old Air Force veteran Oliver Beasley.

Early on March 3, 1991, an intoxicated parolee named Rodney King led police on a high-speed car chase before stopping in Lakeview Terrace. His subsequent beating, which left him with a fractured skull and cheekbone, was caught on video by Lakeview resident George Holliday, who forwarded it to local station KTLA. Within days, the footage of police repeatedly hitting a Black man with batons was airing on all major networks, drumming up nationwide outrage against the officers involved. On March 15, LAPD Sergeant Stacey Koon and officers Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind and Theodore Briseno were indicted for assault in the King beating, with Koon and Powell also charged with filing false police reports. The African American community endured another blow the following day, when 15-year-old Latasha Harlin's was shot and killed by Korean grocer Soon Ja Du over a disputed shoplifting. Shortly afterward, L.A. Mayor Tom Bradley formed the independent Christopher Commission, named for co-chair Warren Christopher, to investigate operations within the LAPD. In July, the commission published a report that detailed repetitive use of excessive force and recommended a new system of accountability, though Gates staunchly defended his practices. On November 15, Du drew a sentence that included community service and suspended jail time, a decision that outraged Harlin family and supporters. Eleven days later, it was announced the trial for the four officers in the King beating would be moved from Los Angeles County to predominantly white Ventura County. In February 1992, the trial commenced with a 12-member jury that included one Latino, one Asian American and one half-African American.

At about 3:15 p.m. on Wednesday, April 29, the jury released their verdict: All four officers were acquitted of charges in the King case, save for a mistrial on one charge against Powell of excessive force. The response was immediate, as protesters took to the streets. Hundreds of people gathered at the Los Angeles County Courthouse to protest the verdict. By 5:30 p.m., the unrest had grown violent near the intersection of Florence and Normandie Avenues in South L.A., where locals attacked passing motorists and forced overwhelmed LAPD officers to retreat. A news helicopter captured footage of white truck driver Reginald Denny being pulled from his rig and beaten nearly to death, with no signs of police assistance. Minutes later, a Latino driver named Fidel Lopez endured a similar attack.

In a matter of hours, neighborhoods across South and Central Los Angeles were in flames as rioters firebombed thousands of buildings, smashed windows, looted stores and attacked the Parker Center police headquarters in downtown L.A. By the end of the day, California Governor Pete Wilson had declared a state of emergency and ordered the activation of reserve National Guard soldiers. The citywide unrest showed little signs of abating on April 30, prompting the suspension of rapid transit, mail service, schools and professional sports games. Many businesses closed, leaving residents to wait in long lines for food and gas, while other store owners, like bands of armed Korean merchants, chose to engage the looters. Although some 2,000 National Guardsmen had reached the city by 8:00 that morning, a lack of proper communication and equipment prevented effective deployment until later in the afternoon. May 1, the third day of continued rioting, was marked by the televised appearance of King, who asked for the mayhem to stop, quietly pleading, “Can we all get along?” That evening, President George H.W. Bush also took to the airwaves to denounce both the “senseless deaths” of the riots and the police brutality that inspired them, and to announce the dispatch of thousands of federal officers to Los Angeles.

By May 2, with 6,000 National Guardsmen bolstered by the addition of another 4,000 federal troops and Marines, the disorder had largely quelled. An estimated 30,000 people marched at a peaceful rally for Korean merchants, and volunteers began cleaning up the streets. Meanwhile, arraignments began for some 6,000 alleged looters and arsonists. Highway exits reopened and police began recovering stolen merchandise the following day, the only significant trouble coming when National Guardsmen shot a driver who attempted to run them over. On May 4, Mayor Bradley lifted the citywide curfew, and residents attempted to resume day-to-day activities with schools, businesses and rapid transit resuming operations. Federal troops stood down on May 9 and the National Guard soon followed, though some soldiers remained until the end of the month.

The final tally for the L.A. riots included 2,000 injuries, 12,000 arrests and 63 deaths attributed to the uprising. Upwards of 3,000 buildings were burned or destroyed and 3,000 businesses were affected as part of the $1 billion in damages sustained by the city, leaving an estimated 20,000 to 40,000 people out of work. At the conclusion of the riots, elected officials set about putting the city back together through a combination of federal grants, collaborations with financial institutions and tax proposals. Governor Wilson and Mayor Bradley tapped Major League Baseball Commissioner Peter Ueberroth to lead the “Rebuild L.A.” effort, which attracted nearly $400 million in corporate investments and set in motion a series of grassroots movements to foster job training and community involvement.

Attention was also focused on the culpability of the city’s law enforcement. On May 11, former FBI Director William H. Webster was named to head an investigation into the LAPD response during the riots, and in late June embattled Chief Daryl Gates stepped down. In October, the commission issued a report that criticized both the LAPD and City Hall for being unprepared and slow to handle the response to the riots. It issued a list of recommendations, including redeploying desk officers into community patrols and upgrading the city’s communications and information systems. Critics of the LAPD earned some vindication in 1993 when officers Koon and Powell were sentenced to 30 months apiece for violating King’s civil rights. In April 1994, King was awarded $3.8 million in a civil lawsuit against the city. Although the LAPD demonstrated improvements with community-based programs, it resisted implementing most of the recommendations of the 1991 Christopher Commission. It wasn’t until the Rampart Scandal of the late 1990s, which exposed widespread corruption within an LAPD anti-gang unit, that serious change was enacted.

In 2000, the city of Los Angeles entered a consent decree with the U.S. Department of Justice that allowed an independent monitor to oversee reforms. After taking over as LAPD chief in 2002, William Bratton was credited with taking steps to overhaul and improve the perception of the department. In 2013, Department of Justice oversight of the LAPD was fully lifted. However, a 2020 report by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights found that thousands of non-traffic infractions issued by police in California were being disproportionately enforced on Black and Latino residents.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bosnian Genocide

In April 1992, the government of the Yugoslav republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina declared its independence from Yugoslavia. Over the next several years, Bosnian Serb forces, with the backing of the Serb-dominated Yugoslav army, perpetrated atrocious crimes against Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) and Croatian civilians, resulting in the deaths of some 100,000 people (80 percent of them Bosniak) by 1995.

In the aftermath of World War II, the Balkan states of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia, Slovenia and Macedonia became part of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia. After the death of longtime Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito in 1980, growing nationalism among the different Yugoslav republics threatened to split their union apart. This process intensified after the mid-1980s with the rise of the Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic, who helped foment discontent between Serbians in Bosnia and Croatia and their Croatian, Bosniak and Albanian neighbors. In 1991, Slovenia, Croatia and Macedonia declared their independence. During the war in Croatia that followed, the Serb-dominated Yugoslav army supported Serbian separatists there in brutal clashes with Croatian forces.

In Bosnia, Muslims represented the largest single population group by 1971. More Serbs and Croats emigrated over the next two decades, and in a 1991 census Bosnia’s population of some 4 million was 44 percent Bosniak, 31 percent Serb, and 17 percent Croatian. Elections held in late 1990 resulted in a coalition government split between parties representing the three ethnicities (in rough proportion to their populations) and led by the Bosniak Alija Izetbegovic. As tensions built inside and outside the country, the Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic and his Serbian Democratic Party withdrew from government and set up their own “Serbian National Assembly.” On March 3, 1992, after a referendum vote (which Karadzic’s party blocked in many Serb-populated areas), President Izetbegovic proclaimed Bosnia’s independence.

Far from seeking independence for Bosnia, Bosnian Serbs wanted to be part of a dominant Serbian state in the Balkans—the “Greater Serbia” that Serbian separatists had long envisioned. In early May 1992, two days after the United States and the European Community (the precursor to the European Union) recognized Bosnia’s independence, Bosnian Serb forces with the backing of Milosevic and the Serb-dominated Yugoslav army launched their offensive with a bombardment of Bosnia’s capital, Sarajevo.

They attacked Bosniak-dominated towns in eastern Bosnia, including Zvornik, Foca, and Visegrad, forcibly expelling Bosniak civilians from the region in a brutal process that later was identified as “ethnic cleansing.” (Ethnic cleansing differs from genocide in that its primary goal is the expulsion of a group of people from a geographical area and not the actual physical destruction of that group, even though the same methods—including murder, rape, torture and forcible displacement—may be used.) Though Bosnian government forces tried to defend the territory, sometimes with the help of the Croatian army, Bosnian Serb forces were in control of nearly three-quarters of the country by the end of 1993, and Karadzic’s party had set up their own Republika Srpska in the east. Most of the Bosnian Croats had left the country, while a significant Bosniak population remained only in smaller towns. Several peace proposals between a Croatian-Bosniak federation and Bosnian Serbs failed when the Serbs refused to give up any territory. The United Nations refused to intervene in the conflict in Bosnia, but a campaign spearheaded by its High Commissioner for Refugees provided humanitarian aid to its many displaced, malnourished and injured victims.

By the summer of 1995, three towns in eastern Bosnia—Srebrenica, Zepa and Gorazde—remained under control of the Bosnian government. The U.N. had declared these enclaves “safe havens” in 1993, to be disarmed and protected by international peacekeeping forces. On July 11, 1995, however, Bosnian Serb forces advanced on Srebrenica, overwhelming a battalion of Dutch peacekeeping forces stationed there. Serbian forces subsequently separated the Bosniak civilians at Srebrenica, putting the women and girls on buses and sending them to Bosnian-held territory. Some of the women were raped or sexually assaulted, while the men and boys who remained behind were killed immediately or bussed to mass killing sites. Estimates of Bosniaks killed by Serb forces at Srebrenica range from around 7,000 to more than 8,000. After Bosnian Serb forces captured Zepa that same month and exploded a bomb in a crowded Sarajevo market, the international community began to respond more forcefully to the ongoing conflict and its ever-growing civilian death toll. In August 1995, after the Serbs refused to comply with a U.N. ultimatum, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) joined efforts with Bosnian and Croatian forces for three weeks of bombing Bosnian Serb positions and a ground offensive. With Serbia’s economy crippled by U.N. trade sanctions and its military forces under assault in Bosnia after three years of warfare, Milosevic agreed to enter negotiations that October. The U.S.-sponsored peace talks in Dayton, Ohio, in November 1995 (which included Izetbegovic, Milosevic and Croatian President Franjo Tudjman) resulted in the creation of a federalized Bosnia divided between a Croat-Bosniak federation and a Serb republic.

Though the international community did little to prevent the systematic atrocities committed against Bosniaks and Croats in Bosnia while they were occurring, it did actively seek justice against those who committed them. In May 1993, the U.N. Security Council created the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) at The Hague, Netherlands. It was the first international tribunal since the Nuremberg Trials in 1945-46, and the first to prosecute genocide, among other war crimes. Radovan Karadzic and the Bosnian Serb military commander, General Ratko Mladic, were among those indicted by the ICTY for genocide and other crimes against humanity. The ICTY would eventually indict 161 individuals of crimes committed during conflict in the former Yugoslavia. Brought before the tribunal in 2002 on charges of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, Milosevic served as his own defense lawyer; his poor health led to long delays in the trial until he was found dead in his prison cell in 2006.

In 2007, the International Court of Justice issued its ruling in a historic civil lawsuit brought by Bosnia against Serbia. Though the court called the massacre at Srebrenica genocide and said that Serbia “could and should” have prevented it and punished those who committed it, it stopped short of declaring Serbia guilty of the genocide itself.

After a trial lasting more than four years and involving the testimony of nearly 600 witnesses, the ICTY found Mladic, who had been dubbed the “Butcher of Bosnia,” guilty of genocide and other crimes against humanity in November 2017. The tribunal sentenced the 74-year-old former general to life in prison. Coming on the heels of Karadzic’s conviction for war crimes the previous year, Mladic’s long-delayed conviction marked the last major prosecution by the ICTY.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Democratic Convention of 1968

The Democratic Convention of 1968 was held August 26-29 in Chicago, Illinois. As delegates flowed into the International Amphitheatre to nominate a Democratic Party presidential candidate, tens of thousands of protesters swarmed the streets to rally against the Vietnam War and the political status quo. By the time Vice President Herbert Humphrey received the presidential nomination, the strife within the Democratic Party was laid bare and the streets of Chicago had seen riots and bloodshed involving protesters, police and bystanders alike, radically changing America’s political and social landscape.

Though the 1968 protest at the Democratic National Convention were largely against the Vietnam War, the country was undergoing unrest on many fronts. The months leading up to the infamous 1968 Democratic Convention were turbulent: The brutal assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in April had left the country reeling, and although segregation had officially ended, racism and poverty continued to make life difficult for many blacks. The Vietnam War was in its 13th year and the recent Tet Offensive had proved the conflict was far from over, as the draft sent more young men into the fray. It was only a matter of time before a showdown would take place between the government of President Lyndon B. Johnson and America’s war-weary citizens. By the time delegates arrived for the convention in Chicago, protests had been set in motion by members of the Youth International Party (yippies) and the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (MOBE), whose organizers included Rennie Davis and Tom Hayden. But Chicago’s Mayor Richard Daley had no intention of letting his city or the convention be overrun by protestors. The stage was set for an explosive face-off. The Democratic Party in 1968 was in crisis. President Johnson—despite being elected with a huge majority in 1964—was soon loathed by many of his peers and constituents due to his pro-Vietnam War policies. In November 1967, a relatively unknown and unremarkable Minnesota senator named Eugene McCarthy announced his intent to challenge Johnson for the Democratic presidential nomination. In March 1968, McCarthy won 40 percent of the vote in the New Hampshire presidential primary, thereby validating his candidacy.

A few days later, Senator Robert F. Kennedy abandoned his support for Johnson and entered the presidential fight. President Johnson saw the writing on the wall and, on March 31, told a stunned nation during a televised address that he would not seek reelection. The following month, Vice President Hubert Humphrey—backed by Johnson—announced his candidacy for the nomination, further dividing the Democratic Party. Humphrey focused on winning delegates in non-primary states, while Kennedy and McCarthy campaigned hard in primary states. Tragically, the race was turned upside down again when Robert Kennedy was assassinated after giving his victory speech following the California primary on June 4. Kennedy’s delegates were divided between McCarthy and dark-horse candidate Senator George McGovern, leaving Humphrey with more than enough votes to clench the Democratic presidential nomination, but also leaving the Democratic party in turmoil just weeks before their national convention. Fed up with Democratic leadership’s penchant for war, yippies protesting at the 1968 Democratic National Convention conceived their own solution: nominate a pig for president. Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman came up with the idea, named their candidate “Pegasus the Immortal” and pledged, “They nominate a president and he eats the people. We nominate a president and the people eat him.” Pegasus the Immortal’s presidential campaign may have been the shortest in recorded history. His chance to become leader of the free world ended abruptly when he, Rubin and other members of his campaign staff were arrested at his first press conference in front of the Chicago Convention Center. (Pegasus's eventual fate remains unknown to this day.)

In July 1968, MOBE and yippie activists applied for permits to camp at Lincoln Park and hold rallies at the International Amphitheatre, Soldier Field and Grant Park. Hoping to dilute the protestors’ momentum, Mayor Daley approved only one permit to protest at the bandshell at Grant Park. About a week before the convention, despite not having permission, thousands of protestors—many of them from out of state and from middle-class families—set up camp at Lincoln Park, about ten miles from the Amphitheatre. Expecting resistance, protest leaders organized self-defense training sessions including karate and snake dancing. In the meantime, Democratic Party delegates began arriving in a Chicago that was rapidly approaching a state of siege: National Guardsmen and policemen met their planes. Their hotels were under heavy guard and the convention Amphitheatre was a virtual fortress.

Initially, Mayor Daley let the protestors remain in Lincoln Park. The day before the convention began, however, he ordered Chicago police to enforce the city’s 11:00 p.m. park curfew hoping that a show of force would clear out the protestors before the convention began. The mood at Lincoln Park was festive at first. There were impromptu yoga sessions, music, dancing and the general revelry that happens when like-minded people gather together to protest the establishment. But the mood turned tense as opening day of the convention approached and the police presence increased. Around 11:00 p.m. on Sunday, August 25, a couple thousand police officers wearing riot gear, helmets and gas masks lined up at Lincoln Park. Some threw tear gas into the crowd. Protestors scattered every which way and rushed out of the park, blindly falling over each other as the tear gas assaulted their eyes. The protest grew violent when the police attacked them with clubs and often didn’t stop when someone was subdued on the ground. Eyewitnesses report it was a scene of unrestrained bloodshed and chaos. Later, the police defended their actions by claiming the protestors shouldn’t have broken curfew or resisted arrest. According to Thomas Foran, the Chicago lawyer who would later prosecute protest leaders, many of the protestors were “spoiled brats who thought that they knew better than everybody…they were being encouraged to do things they shouldn’t do by these sophisticated guys whose idea was to shame the U.S. government.”

On Monday, August 26, the 1968 Democratic National Convention officially opened at the International Amphitheatre. Television cameras captured everything happening on the convention floor but were unable to live broadcast the demonstrations happening outside. Whether the news blackout was due to the electrical workers’ strike (as Mayor Daley claimed) or a deliberate attempt to prevent the public from learning about the citywide protests is unclear. Several states including Texas, North Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi and Alabama had multiple slates of delegates competing to be seated at the convention. Many took the battle to the convention floor. A racially diverse delegation from Texas was defeated. The convention soon became a battleground between anti-war supporters and Vice President Humphrey’s—and indirectly, President Johnson’s—supporters. On Tuesday night, when a promised televised prime-time debate on Vietnam was postponed until after midnight when most viewers would be asleep, the anti-war delegates made their fury known to the point that Mayor Daley had the convention adjourned for the night.

By Tuesday evening, protestors had gathered at the Conrad Hilton Hotel where many of the delegates and candidates, including Humphrey and McCarthy, stayed. As tense police officers tried to maintain control, Mayor Daley sent in the National Guard to help. Protest leader Tom Hayden united the crowd by proclaiming, “Tomorrow is the day that this operation has been pointing for some time. We are going to gather here. We are going to make our way to the Amphitheatre by any means necessary.” On Wednesday, August 28, the promised televised Vietnam debate finally took place to determine if the Democrats would adopt a plank of peace or one of continued war. At the same time, MOBE convened their long-planned and highly anticipated anti-war rally at the bandshell at Grant Park. Up to fifteen thousand protestors gathered, much less than protest leaders had hoped for, and they were quickly surrounded by hundreds of police and National Guardsmen under orders to keep the protestors from reaching the Amphitheatre. Around 3:30 p.m. that afternoon, a teenage boy climbed a flagpole near the bandshell and lowered the American flag. The police moved in swiftly to arrest him as protestors rallied to his aid, assaulting the officers with rocks and food or whatever else they had on hand. Hoping to quell further violence, Davis reminded police that a legal protest permit had been obtained and requested that all police leave the park. In response, the officers moved in and beat Davis unconscious. The police beat protestors at will with clubs and fists. Despite the hostility, anti-violence protest leader David Dillinger still supported protesting peacefully. But all bets were off for Hayden, who feared mass arrests and worsening violence. He encouraged protestors to make for the streets in small groups and head back to the Hilton Hotel.

As things heated up in Grant Park, they also heated up on the convention floor. The peace plank was defeated, a huge blow to the peace delegates and millions of Americans who wanted the Vietnam War to end, and the delegates erupted into chaos. In the words of one delegate, “We were desolate. All of the work that we had done, all of the effort we had made had, it seemed to us, come to naught…our hearts were broken.” By nightfall, a standoff had ensued in front of the Hilton between thousands of angry protestors and thousands of police officers. No one knows who or what triggered the first blow, but soon police began clearing out the crowd, pummeling protestors (and innocent bystanders) with billy clubs and using so much tear gas that it reportedly reached Humphrey some 25 floors up as he watched the bedlam unfold from his hotel room window. At home in their living rooms, horrified Americans alternated between watching images of police brutally beating young, blood-splattered demonstrators and Humphrey’s nomination. During the nomination process, some delegates spoke to the violence. One pro-McGovern delegate went so far as to refer to the police violence as “Gestapo tactics in the streets of Chicago.” Late that evening, Humphrey won the presidential nomination with Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine as his running mate. But the win was nothing to celebrate. Any illusion of unity within the Democratic Party was shattered—after Humphrey’s nomination, many anti-war delegates joined protesters in solidarity and held a candlelight vigil. The next day, the remaining protesters and hundreds of anti-war delegates attempted to reach the Amphitheatre again but were deterred with tear gas. At midnight on August 29, the bloody and contentious 1968 Democratic Convention officially ended.

Over 650 protesters were arrested during the convention. The total number of injured protesters is unknown but over 100 were treated at area hospitals. It was reported that 192 police officers were injured and 49 required medical treatment. Davis, Dellinger, Hayden, Black Panther activist Bobby Seale and four other protest organizers, known as the Chicago Eight, were charged with conspiracy and crossing state lines to incite a riot and brought to trial. After Seale complained about being denied his right to choose his own lawyer, the judge ordered him to appear before the jury each day bound, gagged and chained to a chair. Seale was removed from the Chicago Eight case and ordered to stand trial separately, making the defendants into the Chicago Seven. Seale was sentenced to four years for contempt of court, but the charges were later overturned. After a lengthy, often circus-like trial, the jury found the Chicago Seven not guilty of conspiracy. Five defendants, however, were found guilty of inciting a riot. All convictions were eventually overturned on appeal. The pandemonium at the 1968 Democratic National Convention did little to stop the Vietnam War or win the 1968 presidential election. By the end of the year, Republican Richard M. Nixon was President-elect of the United States and 16,592 American soldiers had been killed in Vietnam, the most of any year since the war began.

The events of the convention forced the Democratic Party to take a hard look at how they did business and how they could regain the public’s trust.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Watts Rebellion

The Watts Rebellion, also known as the Watts Riots, was a large series of riots that broke out August 11, 1965, in the predominantly Black neighborhood of Watts in Los Angeles. The Watts Rebellion lasted for six days, resulting in 34 deaths, 1,032 injuries and 4,000 arrests, involving 34,000 people and ending in the destruction of 1,000 buildings, totaling $40 million in damages.

It was a low-key traffic stop around 7 p.m. on a Wednesday evening that ignited what would become known as the Watts Rebellion. Stepbrothers Marquette and Ronald Frye were pulled over by a white California Highway Patrol officer while driving their mother’s car near the corner of Avalon Boulevard and 116th Street in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. Marquette failed a sobriety test and panicked as he was arrested. As Marquette’s anger rose at the thought of going to jail, a scuffle broke out between him and one of the police officers. Ronald joined in, partly to protest the arrest but also to protect his brother. A crowd began to gather, and back-up police arrived under the assumption that the crowd was hostile, which resulted in a fight between someone in the crowd and an officer. Another newly-arrived officer jabbed Ronald in the stomach with his riot baton and then moved to intervene in the fight between Marquette and that officer.

Marquette was knocked down by the riot baton, handcuffed and taken to the police car. The Frye brothers’ mother, Rena, showed-up on the scene and—believing police were abusing Marquette—rushed to pull the officers off of him, resulting in another fight. Rena was arrested and forced into the car, followed by Ronald, who was handcuffed after attempting to intervene peacefully in his stepmother’s arrest. As the crowd got angrier about the scene they had witnessed, more highway patrol officers arrived and used batons and shotguns to keep the crowd back from the police car. Hundreds more people flocked to the scene to investigate the sirens there. As two motorcycle police attempted to leave, one was spat on. Those police stopped to pursue the woman who they believed did it, the crowd converged around them, sending several other officers into the crowd to assist them. More police cars were called to the scene. The two police found Joyce Ann Gaines and to arrest her for spitting at them. She resisted and was dragged out of the crowd which, believing she was pregnant, became even angrier. By 7:45 p.m., the riot was in full force, with rocks, bottles and more being thrown at the buses and cars that had been stalled in traffic because of the escalating incident.

The night after the arrest, crowds attacked motorists with rocks and bricks, and pulled white drivers out of their cars and beat them. The following morning, there was a community meeting helmed by Watts leaders, including representatives from churches, local government and the NAACP, with police in attendance, designed to bring calm to the situation. Rena also attended, imploring the crowds to calm down. She, Marquette and Ronald had all been released on bail that morning. The meeting became a barrage of complaints about the police and government treatment of Black citizens in recent history. Immediately following the statement by Rena, a teenager grabbed the microphone and proclaimed that rioters planned to move into the white sections of Los Angeles. Local leaders requested the police dispatch more Black police, but this was turned down by the Los Angeles Police Department Chief William H. Parker, who was prepared to call the National Guard. Word of this decision and subsequent news reports about the teenager’s tirade are credited with causing the riots to escalate.