Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Inter beetle :)

gynandromorph stag beetle !!

the finished version on procreate and the initial doodle from my sketchbook !!

“a gynandromorph is an organism, typically an insect, crustacean, or bird, that possesses both male and female characteristics.” or, yanno, trans beetle :)

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don't necessarily agree with this but it has such a mathematical quality to it somehow

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

are you uncomfortable from your hands being dry? if you apply lotion, you can instead be uncomfortable with how greasy they are now. Subscribe for more tips!

86K notes

·

View notes

Text

I love personalization. I love stickers on water bottles and on laptops. I love shitty marker drawing on the toes of converse. I love hand embroidered doodles on jeans. I love posters on walls. I love knick knacks on shelves. I love jewelry with goofy charms. I love when people take things and make them theirs.

98K notes

·

View notes

Text

@zeitschluessel

I'm so fascinated by languages with different levels of formality built in because it immediately introduces such complex social dynamics. The social distance between people is palpable when it's built right into the language, in a way it's not really palpable in English.

So for example. I speak Spanish, and i was taught to address everyone formally unless specifically invited otherwise. People explained to me that "usted" was formal, for use with strangers, bosses, and other people you respect or are distant from, while "tú" is used most often between family and good friends.

That's pretty straightforward, but it gets interesting when you see people using "tú" as a form of address for flirting with strangers, or for picking a fight or intimidating someone. In other languages I've sometimes heard people switch to formal address with partners, friends or family to show when they are upset. That's just so interesting! You're indicating social and emotional space and hierarchy just in the words you choose to address the other person as "you"!!

Not to mention the "what form of address should I use for you...?" conversation which, idk how other people feel about it, but to me it always felt awkward as heck, like a DTR but with someone you're only just becoming comfortable with. "You can use tú with me" always felt... Weirdly intimate? Like, i am comfortable around you, i consider you a friend. Like what a vulnerable thing to say to a person. (That's probably also just a function of how i was strictly told to use formal address when i was learning. Maybe others don't feel so weird about it?)

And if you aren't going to have a conversation about it and you're just going to switch, how do you know when? If you switch too soon it might feel overly familiar and pushy but if you don't switch soon enough you might seem cold??? It's so interesting.

Anyway. As an English-speaking American (even if i can speak a bit of Spanish), i feel like i just don't have a sense for social distance and hierarchy, really, simply because there isn't really language for it in my mother tongue. The fact that others can be keenly aware of that all the time just because they have words to describe it blows my mind!

27K notes

·

View notes

Text

“sex/romance/empathy makes us human,” they say. awful. pathetic. what makes us human is the urge to set things on fire

169K notes

·

View notes

Text

Little rat knight rides her weevil into the forest for an important quest.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I hate when people ask me about my preference but I don’t understand their preference level. Like yes I kinda want Chinese food 10% more than I want a sandwich but if you want a sandwich like 40% more than Chinese food then I would say it’s totally reasonable we get sandwiches.

56K notes

·

View notes

Text

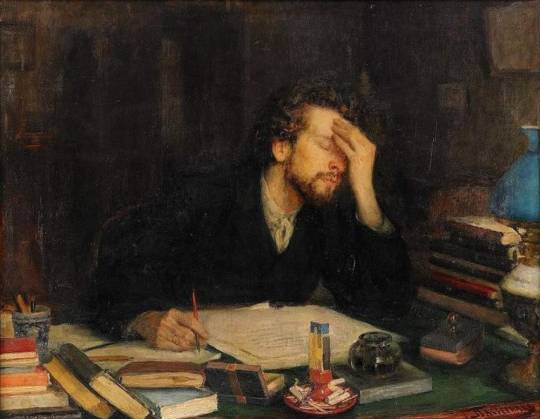

♥︎

Leonid Pasternak (Ukrainian, 1862–1945) - The Torments of Creative Work

156K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ignore the spam, and have a peanut dragon that I drew a few days ago as comphensation (:

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Wake for the Fax Machine

The fax machine is a lot older than you might think. Its first commercial use was providing service between Paris and Lyon in 1865. That’s 11 years before the invention of the telephone!

Indeed, the trusty fax machine lived a long and eventful life. With the advent of Paubox SECURE 2017, the time has come for a remembrance of life for the fax machine.

We are going to hold a wake for the fax machine on Thursday, October 2nd at the Cowell Theater in San Francisco.

The Birth of the Fax Machine

The word fax is short for facsimile. A fax is the “telephonic transmission of scanned printed material, normally to a telephone number connected to a printer or other output device.”

While the first commercial use of the fax machine occurred in 1865, the inception of the fax machine took place almost 20 years earlier.

In 1846, Scottish inventor Alexander Bain worked on chemical mechanical fax type devices that were able to reproduce graphic signs in lab experiments.

From there, Italian physicist Giovanni Caselli invented the Pantelegraph (a hybrid of pantograph and telegraph) where its first commercial use happened in 1865.

For over 150 years, the use of the fax machine has been cumbersome, costly, and difficult to operate.

It wasn’t until 1964 when the Xerox Corporation introduced the first “commercial” version of today’s fax machine, LDX (Long Distance Xerography).

Two years later, Xerox invented the Magnafax Telecopier, a 46-pound behemoth that, ironically by today’s standards, was easier to use and could connect to a telephone line. The fax machine we’ve known until today was officially born.

The Golden Age of the Fax Machine

The fax market soon took off after Xerox’s 1966 Magnafax Telecopier. By the late 1970s, both national and international companies had entered the fax market, especially Japan.

The technological advances of fax machines led to faxes becoming a staple in business offices in the 1980s. This Golden Age lasted until the early 2000s.

The fax machine advanced from a document transmitter to a copier and scanner as well. In a pre-internet age, fax machines were revolutionary.

But sadly, all good things must come to an end. As the Internet emerged, the fax machine slowly phased out of modern businesses in favor of online alternatives.

Today, you can transmit documents in an email and deliver it to your recipient within seconds. This includes sending sensitive information such as credit card information or PHI in a secure manner through encrypted email.

Compared to the lightning speed of the world wide web, fax machines seem slow and outdated.

Some businesses do still have a fax machine, though they are more of a prop than anything else. But other businesses still rely heavily on the fax machine, such as the healthcare industry.

Did you know it costs nearly $250 billion to process 30 billion healthcare transactions each year, 15 billion of which are faxes?

It’s time for a serious upgrade.

3 Things I Will Miss About the Fax Machine

The thrilling suspense of receiving a cover sheet without the proper information filled out. (It’s like receiving a gift from a stranger.)

The delightful tune of a dial tone screech.

Having to hang up the phone before sending a fax because there is only one phone line.

RIP Fax Machine, 1865 – 2017. You will be dearly missed, but the era of the fax machine is over. What took the fax machine a few minutes to accomplish takes only seconds with a secure email.

Healthcare, we need to talk. It’s time to shift away from the slow, outdated fax machine to a more modern, HIPAA compliant way to send patient information: encrypted email.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Brief History of Document Scanning

When it comes to storing and retaining digital documents, the importance of scanning should not be underestimated. These devices are perfect for saving space, cutting costs, and improving efficiency – you can access information at a moment’s notice.

No matter the size of your business, we can all agree that document scanners are game-changers. Without them, most of us would be lost, drowning in an ocean of paperwork and files. Scary stuff!

Here at River City Data, we make it our mission to help you escape the monotony of paper, and convert to the digital space.

But just how did such an integral aspect of our lives come to be so? If you’ve ever stopped to wonder( and even if you haven’t), here is a brief history of how document scanning came to be in your office.

The Humble Scanner

Before we delve into the history of scanning, let’s get some background on that crucial tool: the scanner. The device was invented in Kiel, around 50 years ago, and originated in the guise of the fax machine. The original goal was to transmit information for the newspaper industry.

The first scanners could transmit documents, in the form of images rasterized into pixels and lines. They were also fitted with sensing drums; this means that color originals could be read electronically for the first time.

The color values were first converted into electrical current. Then, using light sensors, a photomultiplier converted the incoming light into electric current, before amplifying it. This change allowed a high-density range and proved a real game-changer.

The original scanner changed and adapted over time, before developing into the familiar flatbed scanner we all use today. This evolution moved the goalposts once more; it introduced the DDC element to form a ‘scan line.

This tool could use a range of color-sensitive photodiodes to read an image, and then reproduce it in color. Even better: it did all this for a cheaper cost.

As needs developed, so did the form of the scanner. Camera scanners emerged with free-moving lenses to capture 3D objects, and film scanners read slides and negatives. Eventually, the CCD chip replaced the CCD line, and this could read a color document in a fraction of a second, saving precious time.

Over time, the design adapted and changed according to the needs and demands of the user. The familiar products we use today have been on a journey, and are liable to change and evolve over time.

So Why Scan?

Just because we have something, doesn’t mean we should use it – so why did scanning become ‘a thing?’

While the first scanner as we know it was introduced around 50 years ago, the concept has been around for far longer.

In the 1860s, the Pantelegraph was a device capable of transmitting handwriting, drawings, and signatures over telegraph lines. It was commonly used as a verification tool for signatures in banking transactions.

The concept of storing and exchanging information is not new, and we need to give our (several great) grandparents credit. Things moved on in 1924 with the invention of the wireless photoradiogram, which allowed images to be sent wirelessly overseas.

Moving On

The next stage in the process was the Belinographe, which arose in 1913, and could scan images using a photocell. The brainchild of Edouard Belin this transmitted over telephone lines and created the basis for AT&T Wirephoto service.

Used by news agencies from the ’20s right up to the ’90s, it acted as the frontrunner to both fax and scanning devices.

Once the requirements of the industry evolved beyond the capabilities of the Belingrophe, it was time for the birth of the flatbed scanner.

As we discussed, these are the most familiar to us today and gained popularity in the early ’90s. Flatbeds optically scan handwritten documents or images and convert them into a useful digital form for businesses across the globe.

These flatbed scanners are sometimes also known as reflective scanners, mainly due to the way they operate. White light is shone onto the object to be scanned and reads the color and intensity of the light reflected. Technology has developed and advanced, and flatbed scanners can now produce copies of up to 5400 pixels per inch.

There are two types of technology used in flatbed scanners, Contact Image Sensor (CIS) and Charged Coupled Device (CCD) technology.

Charged Coupled Device (CCD): The document to be scanned is placed on a glass pane; this can be a book, image, magazine, or similar. A bright light source shines onto the entire document, while a moving CCD scanner captures the content. The scanner contains three sensors lined up, each with a filter: one for blue, one for red, and one for green.

Contact Image Sensor (CIS): CIS also uses a mobile scanner, and again, this has a filter to distinguish red, green, and blue light. A blue LED is used to highlight and illuminate the document during the scanning process. Meanwhile, a monochromatic photodiode array is beneath the rod lends of the scanner; this collects light and renders the image.

How We Use Scanning Today

In the modern world, scanning is a crucial part of everyday business. It allows us to collate and collect relevant information without the need for extensive storage facilities.

In addition, we can access the data we need instantly, thanks to electronic search systems. This, in turn, is a substantial time and money saver. Confidentiality can also be maintained and protected more efficiently, with electronic passwords and sophisticated security systems.

Here at River City Data, we work hard to ensure that your business can run as effectively and efficiently as possible. Our range of services allows you to digitize vast numbers of files, transforming your workspace, and moving your business forward.

We offer a complete scanning and digitization service, as well as the secure disposal of any records once the process is complete. Why not get in touch today for a free estimate, and take the first steps to transform your business into a paper-free paradise!

source https://rivercitydata.com/a-brief-history-of-document-scanning/ source https://rivercitydata.blogspot.com/2020/06/a-brief-history-of-document-scanning.html

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Photography in the 1860s

Technology

The first durable color photograph, taken by Thomas Sutton in 1861 of a multi-coloured ribbon. The formula was developed by James Clerk Maxwell using a combination of red, green and blue filters but it didn’t work out as the film had near to none sensitivity to red and green light.

Jumelle de Nicour, France in 1866. One of the first portable cameras that doubled as a pair of binoculars, a nifty gadget for detectives or spies. The design was then popularized and is still being used to this date.

The Pantelegraph was the first fax machine to transmit written things on a piece of paper such as writing, signatures, and drawings. It wasn’t advanced enough to transmit photographs but it was one of the first things that could transmit some sort of image through large distance. It was invented by Giovanni Caselli in 1860 and then was commercially used in 1861.

In 1864 the invention of Woodburytype was found and patented by Walter B. Woodbury. The process can be found here on pages 6-7. Afterward, the prints were used for commercial things like books, magazines, self-use, and advertisements.

Magnesium Flash Photography was first used in the Blue John Caverns by Alfred Brothers in 1864 and he also used the same flash for a lecture, later on, showcasing the flash for a portrait photograph.

Photographers

Mrs. E. Mayer was one of the first women in India, to become a professional photographer. She opened a studio in 1863 in Calcutta, now known as Kolkata, on 7 Old Court House Street Corner and started photographing women in a safe environment without causing them any harm or making them scared. Later on, in 1864, one of the portrait photos was shown in a year overview exhibition of photos.

Julia Margaret Cameron, also from Calutta, was the most influential and abstract photographer/artist of the decade. Her portraiture photographs were out of focus because it created a soft glow around her subject which she wanted and she would leave any dust or smudges during her developing process.

Her subjects were usually famous men during that time, which are now the way we see them, stylized portraits of stories or myths and portraits of women that were also stylized in her aesthetic.

‘The Passing of King Arthur’ by Julia Margaret Cameron in 1874

‘The Dream’ by Julia Margaret Cameron in 1869

‘Charles Darwin’ by Julia Margaret Cameron in 1868.

Mathew B. Brady was an American photographer who managed to take photos of the civil war. He got a team of over 20 photographers during that time and sent them out all over the states to take photos of the war that was going on. He denied them the copyright of the photos and they were all patented by him, as his work. He is named as ‘the father of photojournalism’ because of ‘on the field’ he managed to create over the years he was active.

His work managed to be printed for all the $5 bills of Abraham Lincoln face.

Grand Review of the Union Army in Washington, D.C., May 1865, photograph by Mathew Brady.

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, Cold Harbor, Virginia; photograph by Mathew Brady, 1864.

Abraham Lincoln, photograph by Mathew Brady, 1864.

4 notes

·

View notes