Photo

What better way to demolish the studio system

Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra

Cleopatra (1963)

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

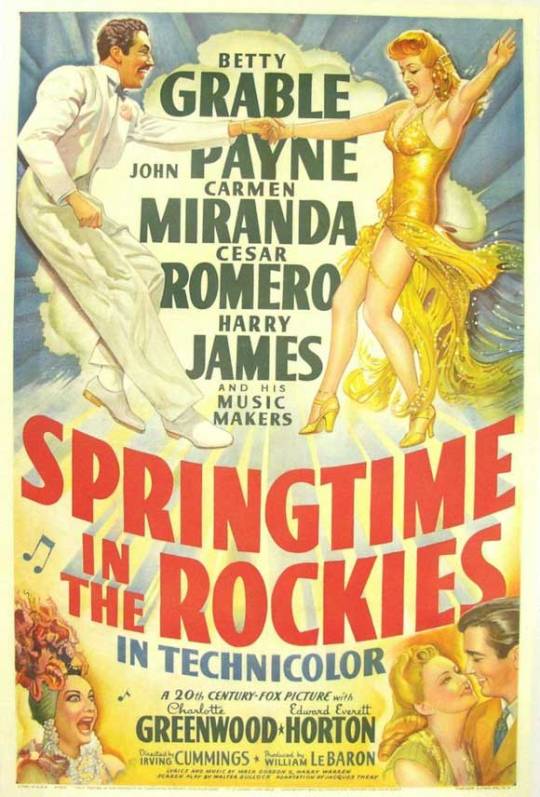

Springtime in the Rockies (1941)

This week we’re looking at the 1941 musical comedy Springtime in the Rockies, purportedly starring John Payne and Betty Grable but really a vehicle for the incomparable Carmen Miranda. It tells the story of a Broadway actor whose two-timing ways lose him a fiancee. Remorseful and desperate for another hit production, he drunkenly decides to track her down in the gorgeous Canadian Rockies, where she’s sort-of-but-not-really fallen for Cesar “The Best Joker” Romero. It’s not bad, kind of a predictable combination of the prewar-style backstage musical and post-Hawks romantic comedy, a nice swing soundtrack if you’re into that sort of thing.

But it’s 100% worth watching for Carmen Miranda, who looms large over the entire production, her sheer goofy presence tearing through the rote screwball proceedings like a big, gay comet. No tutti-frutti hats for the Brazilian Bombshell this go-round, just ruffles, arched brows and an ear-to-ear grin. She sings Chattanooga Choo-Choo in Portuguese. Chattanooga Goddamn Choo-Choo. It could have been embarrassing if it weren’t so fun to watch, if she wasn’t so charismatic and captivating.

youtube

Miranda is iconic. I knew about her in preschool thanks to grey market Daffy Duck videos, not by name of course, but there must have been a good reason that Daffy Duck was wearing bangles and fruit on his head, thrusting his hips and singing “chica-boom.” Carmen Miranda was (at the time of Springtime in the Rockies’ debut) something of a national embarrassment to Brazil, a kind of Larry the Cable Guy-style ugly stereotype, a caricature of folk culture and national identity, a cultural ambassador that made her culture look ridiculous--according to the humorless rich assholes that constituted the Brazilian cultural elite. The Brazilian leftist avant-pop movement of the 1960s, tropicália, eventually reclaimed her as a positive, sincere camp figure. Caetano Veloso, one of the central figures in tropicália (and a musician you should listen to immediately), mentions her in a song named for the movement, which sounds way less subversive than it apparently was. He later spoke of his attraction to Miranda as a camp cultural icon:

You want to bring in an object that’s culturally repulsive, so you go embrace it and then you dislocate it. Then you start to realize why you chose that particular object, you begin to understand it, and you realize the beauty in the object, the tragedy involved in its relationship with humanity...and finally you begin to love it...But before that, there’s a moment when you arrive at that neutral point, when you become uncritical in relation to that object. This was the case with Andy Warhol, who I think stayed at that point right to the end of his life: you cannot think that he is saying: “Look how this is tacky, kitsch, horrible, we should transcend it.” Not at all; he’s at that neutral point when the object is just the object: Bang! It’s in your face and it has nothing to say about itself. So Carmen Miranda, at the time that I wrote “Tropicália,” had reached that point of neutrality for me...She had been recovered: a kind of salvation.

[Dunn, 91-92.]

Veloso’s comments gesture towards the idea of camp as analytic strategy, a way of engaging with an artifact rather than an innate set of qualities. Carmen Miranda only becomes camp if she is approached as such, fruit hats notwithstanding. His notion of “dislocation” and neutrality is particularly interesting, especially in relation to his overtly empathetic reading of Miranda (her “tragedy”). Sontag posits that this detachment is critical to camp’s ironic sensibility, that “tragedy is an experience of hyperinvolvement [i.e. a sincere, serious reading of the artifact-as-account], comedy is an experience of underinvolvement [i.e. an ironic, aesthetic reading of artifact-as-artifact]” and that “Detachment is the prerogative of a[ cultural] elite”--that is, the strategy/discourse of camp hinges upon deliberately identifying artifacts as such (Sontag, 288).

youtube

To approach Carmen Miranda as an accurate account of prewar Brazilian “national character” or folkways is perhaps missing the point, but to approach Carmen Miranda as an icon, a complete “thing” that exists within the cultural consciousness as a complete “thing” regardless of Brazilian (or global) social/cultural history allows the audience to engage with her as a total aesthetic experience unto herself. Her screen presence betrays the illusory aspect of Hollywood: Carmen Miranda is not an actress playing Rosita Murphy (Sontag, 285-6). Her actions, gestures, vocal tics, outward appearance and dress reveal only Carmen Miranda the person generating and performing the the set of ideas and behaviors that supplant the individual with the “Carmen Miranda-icon” (Foucault, 128).

Betty Grable isn’t a particularly good actress either, but she also lacks the silliness and charisma that makes Carmen Miranda so fun to watch. Whereas Miranda commands your attention, Grable is just kind of there. She’s a movie star rather than a transcendent image, an individual without individual character (Sontag, 285-6). Grable’s weird line readings aren’t bad in a funny way because, unlike Miranda, her weird line readings aren’t meant to sound unnatural. Grable’s foil, played by lanky vaudevillian Charlotte Greenwood, isn’t as overwhelming a presence as Miranda, but at least her bizarre hoedown high kicks, shown at the end of the clip above, are a riot. Here’s an example from another film, Down Argentina Way. I could watch this woman dance all day.

youtube

The film ends with the “Pan American Jubilee,” shared earlier in the post. It’s bizarrely on-the-nose. Carmen Miranda’s US stardom is largely due to Hollywood’s involvement with FDR’s Good Neighbor policy, an effort to assuage Latin American anxieties over the United States’ military interventionism in the region throughout the first half of the twentieth century that had been spearheaded/legitimized by Theodore Roosevelt’s enforcement and expansion of the Monroe Doctrine (though it’s not like we ever stopped). The lyrics of the song explicitly mention being a “good neighbor,” which is jarring in the same way as hearing Bugs Bunny tell you to buy war bonds.

I heartily recommend this film, with the caveat that Carmen Miranda is the only thing that makes it worth seeking out. I realize that almost all of this post has been devoted to her but good lord, what a presence. Happy #NotMyPresidentsDay. We will return next week with the post-expressionist tour-de-force, The Scarlet Empress.

Sources

Dunn, Christopher. Brutality Garden: Tropicália and the Emergence of a Brazilian Counterculture. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Foucault, Michel. "What is an Author?" In Language, Counter-Memory, Practice, 113-38. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977.

Sontag, Susan. "Notes on Camp." In Against Interpretation, 275-92. New York: Delta, 1977.

#carmen miranda#campy#kitschy#betty grable#musical#cesar romero#old hollywood#golden age hollywood#good neighbor#fdr#notmypresident#bad taste#susan sontag#sontag#tropicalia#caetano veloso#bad movies#film#movies#foucault#michel foucault

0 notes

Photo

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) dir. Robert Aldrich

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marilyn Monroe performing “Heat Wave” in There’s No Business Like Show Business (1954).

602 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Black velvet art

18 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

#film#marlene dietrich#james stewart#marlene#western#musical#comedy#blazing saddles#campy#kitschy#susan sontag#sontag#bad movies#trashy#cult film#cult#cult movies

0 notes

Text

Excellent post on queer horror, although I would argue that gay male experience/gaze have been a fixture of fantastic film since Méliès’ Eclipse: Courtship of the Sun and Moon.

Uncanny Queer in Horror

Horror films are, at their core, melodramas; works that delve into the muddled waters of familial, romantic, and sexual relationships in order to showcase the horrors that lie underneath the surface of societal interactions. Things that seem “normal” simply because they are widely accepted as rule by society at large can have their facades abruptly removed, leaving the viewer with the mental anguish and revulsion at having been disillusioned. If we dissemble some of the most quintessential, classic horror films we discover broken family models at the heart of the plot.

Films like The Shining, The Exorcist, Carrie, Rosemary’s Baby, and many other essential films of the horror canon question and complicate the traditional patriarchal nuclear family. Whether it is the unraveling of the patriarchy (The Shining), the complete absence of the father figure (The Exorcist, Carrie; although the father figure is still present through the Church), or the menace of a child destroying its mother (Rosemary’s Baby), melodramatic family situations provide the foundation on which the other horrific aspects of the film can be built upon.

So it is no surprise that a genre concerned with uprooting the patriarchal family has often turned to what is perhaps the largest threat to this family model; homosexuality. Lesbianism in particular threatens this model (two penises are better than none!) and has been the subject matter for far more films than gay male relationships. In fact, it is with difficulty that I can think of any horror films concerned with gay men. It is true that the 1980s and 1990s saw the dawn of the Anne Rice vampire, but it is important that these men were bisexual. Their sexual encounters with other men seem to highlight their promiscuity rather than their homosexuality. The main characters may have sex with other men, but only have lasting romantic relationships with women (or 80 year old little girls).

A far more meaningful example of gay sexuality in horror comes from an unlikely source: the cult slasher A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge. The film is renowned amongst horror fans as “the gayest horror movie ever made.” The Nightmare on Elm Street franchise focuses on our inability to control our dreams and how our unconscious dream state can turn on us. In Freddy’s Revenge, we find a teenage boy grappling with his own homosexuality. The film’s protagonist, Jesse, has a series of nightmares in which he morphs into the evil killer Freddy. Freddy is dangerous and constantly lurks deep within Jesse’s turbulent psyche, threatening to engulf him completely. For Jesse, Freddy represents his deepest fears; his homosexuality and, in particular, his attraction to his best friend, Ron.

The sexual tension between Jesse and Ron builds throughout the course of the film, dwarfing the forced relationship between Jesse and his girlfriend Lisa. The film goes out of its way to display forced sexual interaction between Jesse and Lisa, echoing how Jesse himself forces his relationship to work in order to deny his homosexuality. Jesse’s attempts, however, fall short, for during the film’s pivotal scene, his fears come to fruition. Jesse ends up locking himself in a room with Ron, terrified that Freddy will come out of him and force him to kill Lisa. It isn’t Lisa, however, that Freddy is after, for when a half naked Ron begins to console Jesse, Jesse’s desire for Ron erupts and anthropomorphizes into Freddy, who consequently consumes Jesse and murders Ron.

Freddy’s Revenge portrays homosexuality as something that must be known, acknowledged, and accepted, lest it become dangerous. In this way, the film employs the language of contemporary affirmation politics, which encouraged gay men and lesbians to come out of the closet. Here we see homosexuality as threatening only if it is hidden and denied. Lesbianism, on the other hand, is portrayed as most threatening when it is out in the open, for it threatens the very structure of society.

Rebecca, The Haunting, The Hunger, and Mulholland Drive all display the threatening impact of lesbianism. Whilst not all of these films are horror per se, they all portray lesbianism as the uncanny counterpart to the aforementioned patriarchal family model. So what exactly is uncanny about lesbianism?

Freud’s definition of the uncanny is the German unheimlich, translated literally as “unhomely.” The home has long served as the emblem of the nuclear family, the place where “traditional family values” have their stronghold, where smiling suburbanites mow their lawns and bake cookies. The home is the hearth, the safe core of life where one is safe from the outside world. And, most importantly, the home is what is familiar; knowable, constant, and therefore safe. So when something is unhomely, it becomes foreign, unknowable, and dangerous.

Horror films always have a very important and strict relationship to a particular place, most notably the home or places like the home. In The Shining, the Overlook Hotel takes over the role of the home and becomes the site of a melodramatic familial meltdown, thus emphasizing the uncanny nature of the hotel as something that attempts to be home but fails.

The real threat of the uncanny lies in its distortion of the familiar, its ability to transform the known into the unknown. Horror has employed concepts of the uncanny from the beginning, as Gothic haunted house novels and films are the epitome of the uncanny; quite literally making the homely unhomely by turning the house against its inhabitants. In Rebecca and The Haunting, the uncanny home becomes synonymous with the uncanny female relationships occurring within its halls. When the domesticity of the traditional family is interrupted, the home becomes an unwelcoming place.

Lesbianism is tied to the uncanny home, but in Mulholland Drive, David Lynch, one of the all-time masters of the uncanny, manages to make all of Los Angeles an uncanny locale for lesbian sexual affairs. In Lynch’s works, seemingly idyllic small suburban Edens are revealed as sinister sites of malevolent powers and malevolent sexual encounters. Towns like Twin Peaks and Lumberton become perverted by taboo sexual desire; be it a father for his daughter (even if she is in disguise) or a man’s psychopathic display of hyper-masculine sexual possession.

So when Hollywood, which is built upon the ultimate display of the uncanny in the film studio and production backlot, is revealed in the same disconcerting manner as Twin Peaks or Lumberton, it goes hand in hand with displays of taboo sexuality; in this case, it is lesbian sex. Mulholland Drive tells two stories that are happening simultaneously; one delusional and the other utterly disillusioned, revealing the characters’ pathetic attempts at leading extraordinary lives in Hollywood. Both dimensions feature a lesbian relationship; one seemingly organic and pure, the other full of narcissism and deceit.

#film#horror#notes#queer#camp#nightmare on elm street#campy#kitschy#susan sontag#sontag#bad movies#trashy#cult film#cult#cult movies

2 notes

·

View notes

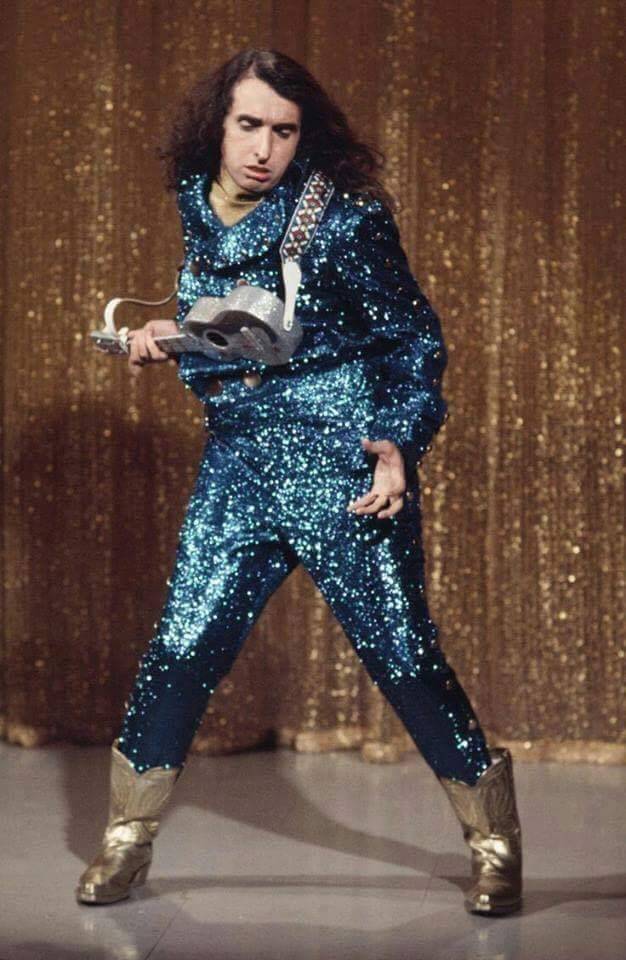

Photo

#1970s#music#artifacts#tiny tim#ukulele#camp#kitsch#sparkles#sequins#outsider music#novelty#campy#kitschy#susan sontag#sontag#bad movies#trashy#cult film#cult#cult movies

359 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This film must have been amazing. So many interesting, weird movies lost in the 1937 Warner Brothers fire.

Ca. 20 seconds survived footage of Theda’s destroyed (burnt) Lost Film “Cleopatra” from 1917”

#1910s#silent#lost film#theda bara#cleopatra#egypt#epic#notes#campy#kitschy#susan sontag#sontag#bad movies#trashy#cult film#cult#cult movies

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Blood and Sand (1941)

So Madame Satan was a dishearteningly dull start to this project, and my planned follow-up, Beyond the Forest, left me with little to say other than “Bette Davis is the greatest anything ever.” She sharp shoots a porcupine out of a tree while saying “I hate porkies,” but that’s not really enough to constitute even a modest article. So let’s talk about Blood and Sand, a 1941 bullfighting extravaganza starring Tyrone Power as Gallardo, a young toreador destined for glory and doomed to his own success, and directed by Rouben Mamoulian, also responsible for the extraordinarily lurid pre-Code Friedric March version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde from 1931 (seriously, it’s amazing how much they got away with).

Blood and Sand features gorgeous costumes, and the characters are preoccupied with clothing as markers of social status. Young Gallardo strips off his peasant smock to fight a bull owned by his future impresario, who sends him off in clothes so fine his mother assumes he stole them. Upon his return to Seville as a modestly wealthy bullfighter, Gallardo showers fine veils and dresses upon his friends and neighbors. The most dazzling photography in the film occurs when Gallardo is dressed, piece-by-piece, in his new matador outfit, royal blue silk embroidered in gold thread and fuchsia with busy floral patterns and a white cape that could have been worn by sad, 1970s Elvis. It’s absolutely gorgeous and I would wear it every day if I was less fat/not worried about cultural appropriation of blood sport. (via Berlinale)

The film’s portrayal of masculinity is wrapped up in Gallardo’s appearance--how he dresses, how he smells, how his body moves, how he eats. American audiences, accustomed to heterosexist/misogynist ideas of manhood, read the decadent florals of Gallardo’s costume and the attention drawn to the amount of expensive perfume he wears (though he points out that it merely masks the smell of horses and bulls) as effeminate. But the film establishes these markers of effeminacy as indicators of Gallardo’s heterosexual virility. There’s a hilarious scene where Rita Hayworth seduces him with his cape and he play-acts as a bull, lowing and grunting in idiotic, animalistic lust.

That visual extravagance is carried over to the set design, gloriously fussy mishmashes of silver arabesques, wrought iron swirls, rococo furniture and wicker. Two Velazquez paintings hang on Rita Hayworth’s wall like it’s no big thing. A crucifix in the matador’s chapel stands ominously before a backdrop of faux marble that make it look EXACTLY like El Greco’s Vision of Saint John. (via flickr)

But Blood and Sand isn’t strictly the funny, ironic camp to which modern students of queer theory have grown accustomed. It’s knock-out melodrama, very effective at that. You gasp when Rita Hayworth steals away Gallardo from sweet Linda Darnell and then hate her even more when she leaves him for his childhood rival, Anthony Quinn. Your eyes pop as Gallardo’s mother delivers a monologue in which she confesses to asking Jesus to let her son be gored in the arena. A rum-drunk Gallardo slaps his friend for suggesting he take a handgun into the arena to shoot the bull like a coward, and it stings. A picaresque, funny first hour resolves into intense psychological drama, a string of humiliations and bad decisions that leaves the ending far less certain than typical Old Hollywood fare (almost like Barry Lyndon, but less mean-spirited).

These are big emotions. But these are identifiable emotions. If camp asks us first to find fault in a text’s representation of affect and behavior and then relish the overblown and overacted, what happens when we approach a well-made, well-acted film AS camp? Camp doesn’t necessarily rely on something being poorly made, but it’s certainly a helpful touchstone, something that gets brought up A LOT. Sontag even acknowledges that camp is “not necessarily bad art, and some art which can be approached as camp.. .merits the most serious admiration and study.” But is it possible for a film to exhibit NO flaws in its screenplay, set design, effects, acting, editing, or score to qualify as a camp piece? Perhaps focusing on “camp” qualities as “flaws,” as something negative or incorrect or even bad, is less helpful than thinking of these qualities as eccentricities, choices in the film that fall outside of the Hollywood norm without necessarily becoming avant-garde. While Blood and Sand isn’t eccentric in the same way as, say, a Powell and Pressburger film or The Scarlet Empress, it’s certainly excessive. I’m not convinced that excess alone is enough to consider something a camp text, though. And although Blood and Sand’s visual excess certainly invites a camp reading, I’m not sure whether it’s silly or dumb enough to actively qualify.

I really, REALLY enjoyed this film. It’s big, bold, gorgeously shot and a wonderfully breezy 2 hours. If you’re not into bullfighting, which most people probably thankfully aren’t (no tea no shade on the proud country of Spain), at least see it for the most shockingly funny scene in sports drama history, where a dummy gets gored through the butt and flies through the air like an idiot.

#film#rita hayworth#bullfighting#costume#set design#camp#velazquez#exoticism#blood sport#cattle#cow#cows#1940s#movies#classic movies#moo cow#queer#vintage hollywood#old hollywood#classic hollywood#campy#kitschy#susan sontag#sontag#bad movies#trashy#cult film#cult#cult movies

0 notes

Video

youtube

(via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=40MO0RY3k-s)

#ephemera#artifacts#fashion#1960s#campy#kitschy#susan sontag#sontag#bad movies#trashy#cult film#cult#cult movies

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Questions Moving Forward

Is there a single, classifiable camp aesthetic? If not, what makes something camp?

On a related note, what sorts of artifacts tend to be camp?

What ideologies are communicated through these artifacts, and are those ideologies at odds with a camp reading of them?

Is a camp artifact, in and of itself, subversive?

Is reading an artifact as camp necessarily subversive?

Is a queer audience/response (subject) necessary for an artifact (object) to be considered camp?

#notes#queerness#theory#camp#campy#kitschy#susan sontag#sontag#bad movies#trashy#cult film#cult#cult movies

1 note

·

View note

Text

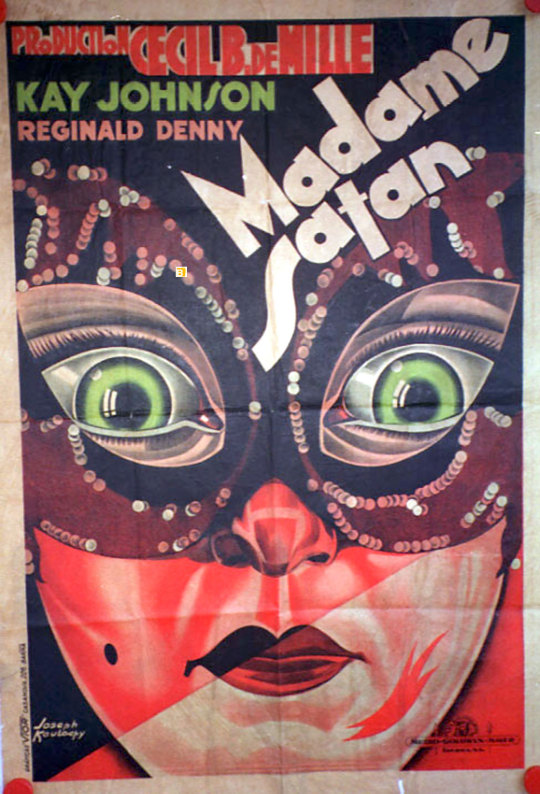

Madame Satan (1930)

Madam Satan, directed in 1930 by Cecil B. DeMille, is not a very good film. Its 2 hour runtime features about 20 minutes worth of kind-of-funny sex capers, the weirdest masked ball scene this side of Eyes Wide Shut, some amazing costumes, and a blimp disaster. It tells the story of Angela, a high society lady whose gallivanting husband, Tom, takes her for granted. He’s boning a flapper named Trixie, who pretends to be married to Tom’s best friend to throw Angela off the scent. Eventually, and I mean eventually, they all go to a masquerade on a blimp, where Angela, disguised as the exotic Madam Satan, tries to win Tom back. It’s a lot of plot for not a lot of story or payoff, although, again, the costumes are fantastic.

For a musical, the music kind of blows. It’s all performed in that weird, warbly old-time white people coloratura that buries its lyrics in vibrato and affected accents. The housekeeper Martha’s song is particularly awful, a completely unintelligible ode to domestic bliss, I think. The one exception is Trixie’s signature hot jazz number “Low Down,” a Charleston-tinged stomper replete with vo-do-de-oh-doing.

By the way, Trixie, played by Lillian Roth, is adorable. She’s a fireball, completely bratty, clearly a better time than poor old Angela. Her facial expressions are hilarious, especially when she’s laying the ruse on thick with a wrinkled nose and overblown smizing. Here she is in a Fleischer cartoon so you can see what I mean (starting around 4:10). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFM5YHVMEZs

The first 45 minutes or so is fairly rote screwball comedy, mostly just lies piling on top of one another until everyone knows who’s lying about what but can’t call them out for fear they’ll do the same (very game theory). There are some great lines that are mostly funny due to how weird they sound in 2016, like Bob defending his sleeping through a concert by explaining there wasn’t a saxophone in the orchestra, “Platonic pajamas,” and “Come to the masked ball I’m throwing on the zeppelin.”

youtube

And what a masked ball on the zeppelin he throws. It’s glamorous and goofy and easily the only reason to watch this film. It begins with a song/tap dance about boarding the zeppelin, continues with an intense choreographic representation of the miracle of electricity, and devolves into a parade of ridiculous costumes with tall hats and baffling concepts (an integral part of one woman’s costume is Tom Sawyer doll, because she’s “the original fish story”). The electric ballet sequence is especially worth talking about. It’s like the Moloch scene in Metropolis if Metropolis was dumb. This whole sequence, with its bizarre costumes, its Art Deco set design, and general fantastical tone, really reminds me of L’Inhumaine, a much better 1924 film by Marcel L’Herbier which will likely be covered on Bart Goes to Camp in the future.

After a misogynist auction where he wins a date with Madame Satan, Tom figures out that she is Angela and the two reconcile while escaping the zeppelin, which gets caught in a thunderstorm. This evacuation sequence is played straight–it becomes A Night to Remember for like 5 minutes–and is aided by some otherworldly double exposure shots and rear projection. Bodies dissolve from the frame like ghosts with lo-fi imprecision and parachutes dangle limply above their evacuees. The danger and drama of the scene is betrayed by its unmasked artifice. Nothing looks real, nothing looks correct, but everything looks right through its wrongness.

Almost 90 years later we can look at its effects and stagey acting and find fault, humor, and alienating, hauntological half-images. Robbed of its drama and denied our emotional catharsis, we instead engage in a willful misjudgment of its aesthetics. It no longer represents an event, but presents the apparatus, that is, the demarcation between movie (the illusory visual story) and movie-making (the illusion-process) becomes blurred, if not outright inverted, by the exposure of the illusion as illusion. This misjudgment is a key strategy to discovering and understanding camp. Reading an artifact as camp relies on that artifact’s seriousness or realism being subverted by its own reception, regardless of its quality (we’ll talk more about this in future articles about better films).

I can’t really recommend Madame Satan in earnest. It’s kind of funny, kind of entertaining, and gets kind of interesting near the end, but Christ it’s a slog. Not even a hunk dressed as lightning makes it worth watching in full, although certain parts of the masquerade are hilarious and dazzling.

#1930s#cecil b demille#musical#pre-code#screwball#art deco#sex comedy#zeppelin#not the band just an actual zeppelin#lillian roth#hot jazz#film#campy#kitschy#susan sontag#sontag#bad movies#trashy#cult film#cult#cult movies

0 notes

Text

Chapter I - Loomings

Welcome to Bart Goes to Camp, an exploration of the subversive queer strategy of camp. If you’re unfamiliar with the concept of “camp”, we can essentially think of it as an ironic reading of/engagement with an artifact (movie, TV show, novel, architecture, visual and decorative art, music, consumer product, etc) that values bad taste and, in Sontag’s words, “failed seriousness.” For instance, the “so bad it’s good” strain of contemporary cult media discourse relies on camp readings of primarily horror, sci-fi, and action films to eke out enjoyment from awful, awful movies. However, the roots of camp run deep through queer history and 20th century media as a whole, beyond speculative fiction and beyond boundaries of taste. This blog will use the wonderful book High Camp by Paul Roeg as a guide, and most of the films discussed here will be found in that book.

A bit about me: I’m Glen. I am a queer white man in my mid-twenties. My field is American studies, with a focus on film, consumer culture, queer theory, horror media, and aesthetics. My favorite movie is The Bride of Frankenstein, my favorite band is Can, my favorite author is Joyce and my favorite food is low-quality gyros. This blog is named after the working title of a personally-super-important Simpsons episode, “Homer’s Phobia”, which guest starred John Waters and was my first real exposure to the idea of bad taste. It will be updated roughly weekly. This is NOT an academic project; there will be contractions, half-formed ideas and probably fart jokes. This is mainly a space for personal reactions to camp media and theoretical approaches to camp as a subject. If that sounds AT ALL interesting, strap in duderina/os, it’s gonna be a bumpy dang ride.

#intro#hey wassup hello#defining parameters#campy#kitschy#susan sontag#sontag#bad movies#trashy#cult film#cult#cult movies

0 notes