Currently completing my Fine Arts Honours at Uni Melb; studying the Bedroom as a site for connection, meditation and growth. If you want to contribute to my research send a picture of your bedroom or a bedroom you have experienced (mess included) to my email [email protected] or straight to my dms here on tumblr. I'm trying to figure out my place in this digital mess...any advice, queries or opinions would be greatly appreciated (and should be sent to "Ask me anything")

Last active 4 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Thinking on old tech

(:̲̅:̲̅:̲̅[̲̅:☆:]̲̅:̲̅:̲̅:̲̅)

990 notes

·

View notes

Text

Framing Devices #007

I remember the first time I saw a “sex toy” — in actuality, it was a sex-adjacent object — I was 10 years old rifling through the drawers of my mother's bedside table when I found a set of black-sequinned heart-shaped nipple tassels.

I immediately stopped searching for whatever it was that I was looking for and took them to my mother. I lifted my hands to her eyes, baring the treasure gently on my palms, and asked, “What are these for?” My mother, being the sex positive person I know her (now) to be, responded simply, “Those are nipple covers, my friend”

Why would you want to cover your nipples with these? They seem impractical. Wouldn’t a bra be easier? Does my mum just wear these sometimes so she can be topless?

These were the immediate thoughts that came to my mind, but eventually I retorted with one question, “Is this for sex?” “Yes, my dear, your dad likes them”, she followed this by poking out her tongue. “Eughhh” was the only thing that came out of my mouth before I ran back to her room to put them away.

She still owns them to this day, and upon reflection, I can confidently say she has great taste in nipple covers.

Since then, I have had the pleasure (pun intended) of administering pulsing vibrations to partners, having sex toys presented to me by others, and enjoying the pinnacle of human engineering upon myself.

I bought my first vibrator when I was 18. My boyfriend at the time said it could be fun, and it was with him, but I couldn’t even approach this bright pink silicone bullet. The first time I turned it on, I was mortified by how loud this tiny machine was. Every time I attempted to get off, I was paralysed with the fear of being caught. To my ears, this device sounded like a monstrous construction site. Jack Hammers, Saws, and drills — a symphony of men at work — not the subtle wank I was hoping for.

I threw it out, placing it deep in my family trash can — underneath a heap of food waste — so that no one would know that I, Luckk Parker, was now a sex pest.

When I moved to college, suddenly everyone around me was talking about sex; it was all-consuming to these fresh high school graduates. Somehow, amid all these conversations around sex, I had become a wise old crone. I was taking my newfound friends to their first sex shop and guiding them on which products would suit their particular needs — I was the most knowledgeable person when it came to getting off with a partner (having a long-term boyfriend granted me such a title).

I would receive text messages telling me, “So I tried that thing we were talking about and it actually worked!” Even though I wasn’t getting any — being in an exclusive long distance relationship fml — I was helping my girlfriends reach their first O.

I think this was when the shame I had built around sex started to fade into obscurity.

-- Luckk

#2000s#00s#early 2000s#flickr#web finds#dreamcore#y2k#digicam#2005#nostalgia#nostalgiacore#weirdcore#liminal#vhs#movie stills#2006#digital archiving#digitalmemoriez#nostalgic#image archiving#2000s nostalgia#late 2000s#mid 2000s#computers#friends#2000s tech#2000s aesthetic#techcore#computer id#tech id

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking on Framing Devices

The iconography that represents you.

Why that book? Why that bag? Why that blog on your screen?

Why do we collect these things that we never use?

Collecting dust until they're rediscovered in a moment of nostalgia, or panic whilst looking for a vape.

-- Luckk

#00s#early 2000s#flickr#web finds#dreamcore#y2k#digicam#2005#nostalgia#nostalgiacore#weirdcore#liminal#vhs#movie stills#2006#digital archiving#digitalmemoriez#nostalgic#image archiving#2000s nostalgia#late 2000s#2000s#mid 2000s#computers#friends#2000s tech#2000s aesthetic#techcore#computer id#tech id

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Framing Devices #003

It’s 5:00 am … no, 5:03 am, depending on whether you trust the DVD player clock or the VHS player clock more. I’m at Paris’ house, and I’ve been woken up by a few stimuli:

The magpies, celebrating their harvest

The static emanating from Paris’ boxy TV — still paused from last night

The foul stench of stale French fries (my mum never let our family have fast food)

Ruby’s snoring carrying across the room — such a powerful sound for someone so small

And my own fear that this slumber party was about to end.

I’m careful not to cause too much disturbance. I don’t want to be the weird girl who wakes up before the sun, or the annoying girl who wakes everyone else up before they’re ready. Perpetually anxious, and forever fearing my social demise.

So I just wait there — perched on this trundle bed — staring at this clunky tech, occasionally catching my reflection between TV flickers and waves of visual static, wondering:

Why did I have to be the first one awake?

Was I acting weird last night?

And will I make the cut when invitations go out for the next sleepover?

-- Luckk

#2000s#00s#early 2000s#flickr#web finds#dreamcore#y2k#digicam#2005#nostalgia#nostalgiacore#weirdcore#liminal#vhs#movie stills#2006#digital archiving#digitalmemoriez#nostalgic#image archiving#2000s nostalgia#late 2000s#mid 2000s#computers#friends#2000s tech#2000s aesthetic#techcore#computer id#tech id

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

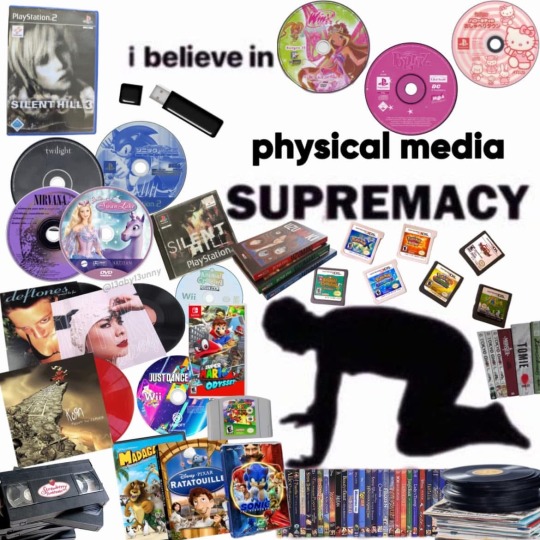

On Physical Media

When my nan first showed signs of Lewy body dementia, it became obvious that she would need to be moved from her single-story brick home in Fairlight into an aged care home — one with round-the-clock supervision.

It started with collapses in the supermarket. Then came the hallucinations — bugs crawling on the walls of her hospital room — and finally, she began confusing me for my mother. They never had a great relationship, so when I went to embrace her — in that clinically mangled bed — the rejection felt all the more saddening. She spoke to me, believing I was my mother.

“Make sure the kids get $100 from me. I know they’re worried about me.” I cried in that moment — an automatic response — a mixture of ego and a fear of mortality. “I didn’t realise you cared for me this much, Fran.”

A family meeting took place shortly after.

My father, his three sisters (at the time), and his brother discussed money, facilities, and next steps. This was two days after Christmas, 2023. By April, I was told that, as the only person in our family over the age of 18 and without full-time employment (ouch), it would be my responsibility to sift through every item in her bungalow and decide: What was sentimental? What was donatable? And what was trash?

I had inadvertently been training my whole life for this moment. My mother was a spring-cleaning fanatic. Like clockwork, once every three months throughout my entire childhood, I would be tasked with auditing the value of the objects in my possession — having to concretely prove how my pink bubble CD player added to my happiness and thus deserved the 30cm² of space it occupied in my bedroom.

How morbid — years of unknowingly prepping for the eventual collapse of my poor nan’s mind.

September rolled around. The cardboard boxes were ready — as were the jumbo reinforced black garbage bags. I thought I was ready too. How naive.

I started with her chestnut TV chest. 152 vinyls, ranging from Scottish choir hymns to Talking Heads. 65 VHS tapes — every Disney princess I wanted to be, now covered in dust and cockroach dung. Every single PG and G-rated film produced between 1999 and 2009 — the last year I had a sleepover in that single-bed room, adorned with nothing but flannel sheets and a strangely attractive portrait of Mother Mary on the bedside table.

I was sorting through the physical remnants of my childhood, unaware that my nan had curated every like, dislike, and fantasy of my youth. Now I was faced with the impossible task of determining the worth of my memories.

Keep, donate, or throw away.

Her living room, now devoid of most of its furniture and décor, began to flicker with projections of times gone by. I could see my brother and me cuddled up to her on the couch, laughing hysterically at our Pa’s flatulence. This fragment vanished as quickly as it appeared, only to be replaced with another. I saw my nan picking out a CD from her ridiculous collection to play as we tended to her rose garden, which surrounded a clay statue of Mary. Just as I saw my six-year-old self jump in the air at the sound of Mika, surrounded by deep reds in bloom — the vision faded. I was left staring at a now bone-dry garden and a lonely Mary, stained with white bird crap.

What could’ve been accomplished in a day by my mother — unsentimental and practical — was stretching into weeks for me. My father had to stage an intervention.

“Hi, cookie girl. I know this isn’t easy. Carmel’s a hoarder, after all, but we don’t have a lot of time left. We need to sell the house so we can pay for her care.”

My father was right. My nostalgia was delaying the truth: my nan wasn’t going to get better, and these things had no place in our lives anymore.

We hadn’t owned a media player of any kind in eight years, for Christ’s sake. Stan, Binge, Netflix, HBO Max, and Prime now housed my childhood — all for $69.97 a month.

I eventually finished sorting through my nan’s house — every item accounted for and distributed to its proper place. I did, however, keep three things for myself:

An LG 220K20D TV

An LG V8824W DVD & VCR player

Shrek 2 on DVD

A challenge to build my own media collection. A tribute to my nan.

-- Luckk

Nothing like holding my love

#2000s#00s#early 2000s#flickr#web finds#dreamcore#y2k#digicam#2005#nostalgia#nostalgiacore#weirdcore#liminal#vhs#movie stills#2006#digital archiving#digitalmemoriez#nostalgic#image archiving#2000s nostalgia#late 2000s#mid 2000s#computers#friends#2000s tech#2000s aesthetic#techcore#computer id#tech id

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

Remembering in the digital age

I remember using the Internet Archive for the first time at the age of 13. I had become a certified weeaboo at this point in my life and was desperate for my own copies of Fruits magazine. The gaudy colours, mismatching of patterns, clunky accessories and superior sense of self conveyed by this street fashion documentation was earth shattering to me — how could people confidently dress so outrageously? Was I allowed to dress like this? With little access to money, and 7,820 kilometres of distance separating me from my potential as a fashion kid, I decided to go to the Internet Archive to source copies of these magazines.

I would download these archived issues and print them at my local library — A4 stock standard paper had never been so valuable to me until this moment.

This wasn't just about downloading images. This was a formative act of cultural translation, of self-invention through the preservation of other people’s self-expression. It wasn’t about retro for retro’s sake; it was about seeing a possible future through the past, one I couldn’t find in my local surroundings. For artists like me (nostalgia artists who rely on digital archives as our material) the Internet Archive has never been simply a storage facility.

It is a lifeline.

That’s why the current existential legal threat to the Internet Archive and its Wayback Machine is terrifying. At a time when digital information is being deleted, rewritten, or quietly erased from the web, the idea that we could lose this open, publicly accessible repository of culture, knowledge, and memory is more than just unfortunate — it’s a kind of slow cultural lobotomy.

In many ways, nostalgia art isn’t about the past at all. Art that engages with feelings of nostalgia is about our relationship to memory, to access, to media decay and survival. When I work with screenshots, obsolete aesthetics, old LiveJournal entries, or jpegs from dead links, I’m not just mimicking an ‘vibe’. I’m asking: what did this mean to someone once? Who were they when they made this post? How does the shape of a MySpace profile page change our understanding of broadcasting, of self-presentation?

When media is erased, whether intentionally or through corporate obsolescence, it’s not just a loss of trivia or entertainment.

It’s a severing of connections.

We lose the texture of our collective memory. We lose the ability to understand how people felt, expressed, resisted, or dreamed in their own digital time. Knowledge becomes flattened to what’s commercially viable, or algorithmically favoured. And when that happens, our ability to communicate meaningfully across generations of internet use collapses.

As an artist working with digitally archived material, I rely on these fragments of history to challenge the present. To reimagine identity, expression, and narrative by returning to the discarded, the low-res, the cringe, the earnest. If the Internet Archive disappears or is dramatically limited, that material — and the potential for new readings and creations it offers — disappears with it.

It’s hard to talk about deliberate attempts by the Trump Administration to enact internet destruction without acknowledging the reality that the internet decays “naturally” all the time. The internet forgets all the time, and more importantly, it is made to forget. Websites rot. Domains shut down. Platforms delete unpopular opinions or copyright-infringing content without appeal. Without tools like the Wayback Machine, we’re left with an increasingly shallow internet, scrubbed of its context, cleaned of its character.

The erosion of digital archives isn’t just a problem for artists — it’s a problem for democracy, for history, and for education.

-- Luckk

Internet Archive and 'The Wayback Machine' are Experiencing an Existential, Legal Threat.

Below is a link to a petition whose goal it is to save one of the most effective tools against digital censorship available to the public.

"At a time when digital information is being deleted, rewritten, and erased, preservation is more important than ever."

Signing this petition is FREE and takes less than 5 minutes.

Recently, user @we-are-astronomer was able to utilize Internet Archive's Wayback Machine to locate and preserve government articles DELETED from the NASA website by Trump Administration censors. For more information, their post can be found underneath the break.

If resources such as these are destroyed, we risk losing every digital article and file deleted under the Trump Administration's censorship. Without a method for restoring erased information, censorship proceeds unhindered. No body, no crime.

Collective action gets results. Do your part to protect public peace of mind.

#2000s#00s#early 2000s#flickr#web finds#dreamcore#y2k#digicam#2005#nostalgia#nostalgiacore#weirdcore#liminal#vhs#movie stills#2006#digital archiving#digitalmemoriez#nostalgic#image archiving#2000s nostalgia#late 2000s#mid 2000s#computers#friends#2000s tech#2000s aesthetic#techcore#computer id#tech id

317 notes

·

View notes

Text

Framing devices #006

I always found myself in my brother's room during my youth. Even though we were close in age—only nine months apart—he had somehow amassed three times the amount of stuff I owned in such a short period of time. It shouldn’t have surprised me. Looking back, I can clearly see that my brother was quite the entrepreneur. He had a talent for trade, convincing just about anyone on the playground to hand over their most prized possessions in exchange for little to nothing.

Nintendo games, Pokémon cards, Power Rangers merch, crystals, hand-me-down relics inherited from our older cousins, and an apparent freedom to decorate his room however he pleased—these were the things that captivated me. An incredible feat.

He was the best playmate I had as a child: generous, imaginative, and energetic. He could always be found either tinkering with his Lego designs or dressed up as Captain Jack Sparrow (or Luke Skywalker), fighting battles invisible to me but always emerging victorious.

But the thing about having so many cool things in your room—and being able to create such vivid worlds within it—is that you can fall into the trap of never wanting to leave. From the ages of 10 to 17, my brother locked himself away, emerging only as someone almost unrecognisable from the boy I once knew.

My sweet brother had changed. He was taller, hairier, jaded, and quiet. His smile was weaker. The shoulders that once jumped ferociously when he laughed were now still—unmoved by any attempt to jest.

We’re both much older now. We’ve both left our rooms for good—only returning to sleep. I’m in the process of reacquainting myself with him. I hope to be his playmate once again.

This digital collage is my attempt to remember the clutter that first drew my attention—and kept me entertained for years.

-- Luckk

#art journal#academic art#artists on tumblr#confessional art#contemporary art#digital art#old internet#art#artwork#collage#digital collage#collage art#childhood nostalgia#nostalgia#2000s nostalgia#nostalgic#nostaligiacore#bedroom#bed rotting#playing#years#revealed#journal#remember#remembering#my diary#diary#digital diary#dear diary#writing

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

When nostalgia becomes painful

I remember begging my mum, in line at the Woolworths checkout, for one of those brain-numbing pre-pubescent magazines—solely for the gift wedged between the plastic encasing and the front cover. It was April, and that month’s gift from Teen magazine was an awfully cheap jelly makeup set: pink sparkly lip gloss, blue sticky eyeshadow, and microscopic sponge applicators. In my child mind, I wholeheartedly believed this makeup kit would set me on the path to becoming a "big girl"—every five-and-a-half-year-old’s dream.

My mother refused me every time. And rightly so—why should her baby grow up faster than necessary? Why should she be reading about how to impress boys or stay thin during the summer months? I look back now and can only imagine how much she must have dreaded the checkout at our local grocer. I was a painfully insistent child.

Even though I was just a kid, when I engage with the murky beast that is nostalgia, I often think of my mother—and the grief I must have caused her.

-- Luckk

"ωє'ℓℓ мєєт αgαιи, ∂σи'т киσω ωнєяє, ∂σи'т киσω ωнєи"

кєєρ gσιиg fσя тнє кι∂ ωнσ ωαитє∂ тσ gяσω υρ ѕσ вα∂ℓу, нσωєνєя мυ¢н уσυ ωιѕн уσυ ¢συℓ∂ gσ вα¢к

#2000s aesthetic#2000s nostalgia#childhood nostalgia#2010s nostalgia#2000s#early gen z#early 2000s#nostalgic#nostalgia#nostaligiacore#dreamcore#weirdcore#liminalcore#liminal spaces#liminal#writing#writers on tumblr#writers and poets#artists on tumblr#small artist#diary entry#digital diary#dear diary#diary#art journal#journal

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why am I back here?

It’s period one of my first ever high school class—Ms. Simpson’s English—and I’m sitting next to a girl boasting about her 8,000 followers on Tumblr. Until that moment, I had been steadily avoiding Tumblr on the advice of my older sister’s friends, who warned me about the explicit content, mature themes, and the neerdowells that inhabited the site. As a 12-year-old attending an all-girls Catholic school—quietly grappling with my non-hetero sexuality and burgeoning atheistic tendencies—I believed I had enough to deal with without adding Tumblr to the mix.

Looking back now, at 24, I’m still unsure what it was about this girl’s tone (or her outright belief that her Tumblr status elevated her above the rest of us) that compelled me to create my first account. But in that moment, I felt challenged. I wanted to outdo her. This was the beginning of my undoing.

The account I created, which no longer belongs to me (I eventually sold it at its peak), was called “kawaiiinpink.” It was dedicated entirely to all things pink and aesthetically pleasing. I taught myself HTML just to design a blog that would be undeniably superior to her Lana-coded sad-girl page. As I gained followers and ventured deeper into the underbelly of Tumblr, I was exposed to some of the internet’s filth: Ana propaganda, self-harm confessions, hardcore porn, and diary entries that should never have been made public—content fed to me daily through the explore page. It slowly distorted my young mind and my sense of self.

Two months in, I began binge eating. I had convinced myself I would never look like Alexa Chung, so I punished myself through a cycle of bingeing and yo-yo dieting, eventually gaining 10 kilograms in the span of a year—a shameful, self-fulfilling prophecy. As my belly grew, so did my online presence. “kawaiiinpink” reached 50,000 followers, and the direct messages became increasingly depraved. I spent hours reading requests to show my “pink bits,” reacting to strangers asking me to rate their naked bodies, and fighting off bots trying to purchase my account. Tumblr had become my primary media diet, yet the only place I could indulge in it was the privacy of my bedroom. Even though no one was forcing me to stay there, I came to associate Tumblr with a kind of guilty pleasure—a secret that had to be hidden. That period lasted two and a half years.

Now, as an adult reflecting on the bedroom through the lens of academic art practice, I can confidently name Tumblr as a critical puzzle piece in the development of my work. It was the first space where I encountered confession, shame, and the raw broadcasting of one’s unfiltered self to an anonymous audience; one that could respond without consequence. Returning to Tumblr, as a platform shaped by radical transparency and rampant free thought, feels like a natural extension of my current research into the bedroom as a site of meditation, growth, and connection. Tumblr’s architecture (anonymous, image-heavy, and archive-driven) mirrors the emotional interiority of the bedroom: private yet performative, intimate yet intrinsically linked to broader cultural rhythms. Just as the bedroom is a space to retreat, unravel, fantasise, and rebuild, Tumblr once offered me a similarly liminal zone; where shame, longing, obsession, and self-reflection could be publicly rehearsed. Its legacy as a confessional space for youth in crisis aligns seamlessly with my desire to excavate the psychic residue embedded in domestic environments. By returning to the platform, I aim to reactivate a former mode of expression—part digital reliquary, part emotional outburst—where the bedroom is not merely represented but embodied through scrolling, curating, and posting as acts of self-meditation.

-- Luckk

#academic art#art journal#artists on tumblr#confessional art#contemporary art#digital art#old internet#art#artwork#collage#essay#digital collage#digital drawing#diary#dear diary#digital diary#diary entry#journal entry#my diary#online diary#shifting diary#tumblr girls#writers on tumblr#writing#writers and poets#my thougts#thoughts#reflection#self reflecting#personal

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

BREATH WORK

Ever since I started going out and allowing myself the space to become the club rat I know myself to be — in my heart of hearts — I’ve grown strangely fond of club bathrooms. And it’s not for the compliments from wasted or heartbroken girls, or the invitations to partake in substances from charming strangers — although I love both.

No, my fondness comes from the curatorship that occurs on the walls, the toilet seats, and the flimsy doors of said club bathrooms.

Poopin’ poets lay out the most devastatingly beautiful sonnets in permanent marker during their moment of rest, only to forget they ever wrote such a thing when they return the following weekend. Love notes, stickers, call-outs, and numbers promising a “good time” — all assembled in a visual heap, barely illuminated in these dingy loos — captivate me and calm me when I’m on the brink of losing myself.

Too many drinks, a mystery powder, seeing my ex–best friend — any of these things could’ve brought me to this stall. But the fodder left behind by other club-goers re-centers me, grounds me, and reminds me that they, too, sought sanctuary here. The word “VACANT” plastered on the lock lets me know they made it out of this club. I’m going to be fine.

Sometimes, I find myself in the bathroom just to catch my breath. The smoking has taken a toll on my lungs — but I won’t quit. Socialising in Narrm is much easier with a cigarette.

When I start to dance, I’m back in my bedroom. I’m floating from one place to another — guided by free-flowing movement and zero inhibitions. The speakers may be saying one thing, but all I can hear is my own playlist — my favourite songs — serendipitously matching the BPM of the local DJ’s set.

-- Luckk

#artists on tumblr#art journal#contemporary art#confessional art#digital art#old internet#art#artwork#collage#academic art#clutter#flashing lights#club#party#bar#technomusic#electronic music#edm#drugblr#girls who do hard drugs#tw drugs#sex and drugs#clubbing#bathroom#post internet#girl interrupted#interior design#digital collage#photography#this is a joke

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Framing Devices #002

send me your bedroom {raw}

#confessional art#academic art#art journal#contemporary art#fiction#digital art#art#artists on tumblr#my art#artwork#mixed media#media#digital collage#collage#collage art#digital drawing#post internet#old internet#internet#internet art#archive moodboard#2006#archive art#internet archive#internet diary#internet culture#the internet#diary#digital illustration#journal

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Framing Devices #004

show me your room (raw)

#contemporary art#digital art#digicam#digital illustration#collage#digital collage#mixed media#art journal#academic art#confessional art#bedroom#messy girl#messy moodboard#bedding#clutter#build mode#i love trinkets#trinket collection#not real#artwork#artists on tumblr#my art#art study#pink#pink aesthetic#old internet#female#hell is a teenage girl#fiction#myspace

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Communion & Shame: A Critical Analysis of Confessional Art through the Comparison of Tracey Emin's My Bed (1998) with Jon Rafman's Solo Exhibition at the Zabludowicz Collection (2015)

In the pluralistic terrain of contemporary art, personal narrative and mediated experience often collide in revealing ways. Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998) and Jon Rafman’s immersive installation in his first solo exhibition Jon Rafman at the Zabludowicz Collection (2015) form a compelling dialectic of oppositional strategies. Emin’s work is grounded in bodily presence and material honesty, engaging a feminist lineage of reclaiming interior space and lived trauma. Rafman’s digital environments, by contrast, stage a masculine, post-internet digestion of the world that is mediated, fragmented, and disembodied.

This essay critically compares these two works, exploring how they construct affect, identity, and narrative through contrasting means. It situates My Bed within traditions of feminist installation and abject expression, and Rafman’s practice within the aesthetics of digital detachment and algorithmic interiority. Drawing on a range of theoretical and critical frameworks from affect theory and media studies to feminist art history and digital aesthetics, it assesses the interpretive tensions and generational shifts each artist reflects. Ultimately, this comparison reveals not only how confessional art navigates the crisis of selfhood but also how it embodies either the radical intimacy of reclaiming or the distanced spectacle of regurgitation.

Emin and Rafman are separated by generation, gender, and intent, but both operate under the umbrella of confessional art. Each positions the viewer within a space of exposure, whether physical or emotional, and frames the artwork as a lens through which personal or cultural trauma is mediated. For Emin, confession is a tool of reclamation. She stages her own reality with all its messiness and contradictions, foregrounding lived experience as political . Rafman, conversely, submerges his own presence within constructed realities that reflect the collective malaise of post-internet identity. “I investigate subjectivity, that is, what hyper-accelerated contemporary existence does to the psyche,” Rafman explains, aligning himself with the generation that grew up online and whose sense of self is shaped by digital immersion rather than introspection.

Emin’s work emerges from the Young British Artists (YBA) milieu of the 1990s and is deeply informed by feminist and autobiographical practices of the 1970s and 80s. Her raw, unfiltered disclosures resonate with the confessional traditions seen in the work of Carolee Schneemann or Nan Goldin, while being situated within a commercial and institutional art world increasingly receptive to spectacle. Rafman, working in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and amidst the rise of social media, reflects a disillusioned generation coping with alienation through digital means. His aesthetics stem from post-internet art and media archaeology, where memory is no longer rooted in personal narrative but diffused through memes, simulations, and algorithmic repetition.

Despite their differences, both artists confront the viewer with uncomfortable proximities. Emin’s strategy is intimate and confrontational. Rafman’s is immersive and estranged. Each reconfigures confession not merely as self-disclosure but as a way to implicate the audience; either as voyeurs or co-conspirators in the broader cultural landscape. This implicating structure is especially relevant when we consider Berger’s assertion that in traditional art “men act and women appear,” and that women have been culturally conditioned to survey themselves constantly from the position of the other (Berger, Ways of Seeing, 1972, 46��47). Emin’s self-display short-circuits this economy by refusing to present a body as image — instead, she presents the image as aftermath of the body.

The Gendered Bedroom

Historically, the bedroom has been a gendered site; a space of privacy, sexuality, and subordination, particularly for women. In traditional Western art and literature, the bedroom frequently serves as a stage for voyeurism and eroticisation. From classical painting to contemporary media, female bodies are repeatedly depicted reclining, passive, or asleep; offering themselves to the male gaze. This visual legacy positions the bedroom as a zone of leisure and

submission, reinforcing the objectification of women in domestic space . Emin’s My Bed radically subverts this tradition. Rather than a scene of seduction or repose, her bedroom is a site of collapse, distress, and authenticity. She doesn’t aestheticise her body for consumption; rather, she presents its traces (bodily fluids, tampons, dirty linens) as remnants of emotional and physical trauma. In doing so, Emin reframes the bedroom from a place of feminine passivity to one of active resistance. Her confessional use of domestic space aligns with feminist artists such as Judy Chicago and Louise Bourgeois, who likewise challenged patriarchal spatial politics through personal materiality. Gülsüm Baydar notes that My Bed breaks from the “standard image of the master bedroom” by foregrounding “messiness” and excess, presenting the ungovernable materiality of a woman’s private life as a spectacle not of beauty, but of rupture.

The bedroom also operates metaphorically in Emin’s work; as a psychic space from which the artist attempts to escape. Her confessional strategy transforms the bedroom into a stage of agency: by exposing what is usually hidden, she asserts authorship over her narrative. Emin’s autobiographical fragments challenge both narrative cohesion and cultural norms of feminine As Berger observed, “A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself” reinforcing the idea that women’s lived space, including the bedroom, has historically been shaped by the expectation of being seen.decorum, producing a visual excess that resists polished spectacle and forces the viewer into a collaborative, interpretive role. Instead of escape through idealisation, Emin breaks out of the domestic through abjection and radical honesty. Emin’s installation brings the abject into public view; it rejects symbolic cleanliness, embodying instead the “semiotic excess” of what cannot be fully assimilated by rational discourse is especially relevant here.

In contrast, Rafman’s evocation of the bedroom in his digital worlds reflects a shift in gendered dynamics. In his installations, domestic space becomes a screen onto which male anxieties, fantasies, and desires are projected. The virtual bedroom becomes a refuge for disembodied masculinity. These spaces are not about intimacy but about simulation and control . As Rafman has reflected, his work captures “the psychic consequences of digital immersion,” a condition of identity formation that emerges not from embodied experience but from “doomscrolling”; an aesthetics of overconsumption, fragmentation, and alienation (Rafman in Interview Magazine, 2023).

In contemporary post-internet culture, male users often appropriate domestic settings as zones of performative identity. Through avatars, vlogs, and streaming environments, the domestic is no longer confined to physical interiors but extends into digital platforms. Here, the bedroom is not a space of constraint but of unregulated fantasy; a place where toxic masculinity can fester under the guise of safety and anonymity. Rafman’s art doesn’t necessarily critique this dynamic directly; rather, it stages it with a hallucinatory ambivalence that blurs complicity and critique. Gene McHugh describes this shift as central to post-internet art: “not art that uses the internet as a medium, but art that emerges from the conditions the internet creates” (McHugh, Post-Internet, 2011). In Rafman’s case, these conditions include estranged affect, fragmented memory, and a disavowal of bodily vulnerability.

The comparison between Emin and Rafman underscores a generational and gendered divergence. Emin’s reclamation of the bedroom is an act of embodied protest, emerging from a context in which the female artist had to fight for the legitimacy of her pain. Rafman, conversely, constructs simulated interiors from the perspective of a post-human observer; masculine identity fragmented, mediated, yet still dominant in its voyeuristic lens. Baydar argues that feminine excess disrupts the clean lines of patriarchal visual culture, defying the ideal of the private, controlled, silent bedroom.

I Must Confess

Emin’s material honesty, spatial directness, and refusal to mediate pain through stylisation offer a framework for art-making that is emotionally and politically urgent. Rafman’s worlds, while visually rich, often feel emotionally sterile; a reflection of the culture he documents . Rafman’s installation at the Zabludowicz Collection includes a constructed, artificial bedroom: three walls and a carpeted floor approximating a domestic interior. It resembles a set, a stage; one that evokes the bedroom of a teenage girl. This theatrical simulation draws attention to the artificiality of the space, which, rather than suggesting intimacy, signals voyeurism. The viewer becomes a spectator in a staged domestic scene, implicating themselves in Rafman’s position as a male artist navigating online subcultures and affective detachment. The dynamic Rafman constructs aligns with what Berger identifies in historical painting; the feminine as staged for male consumption, made to be seen rather than to see (Berger, Ways of Seeing, 1972, 47).

This simulated bedroom isn’t based on Rafman’s lived experience, but rather on an amalgamation of internet iconography and cultural tropes. It channels the aesthetics of webcam culture, teen influencers, and soft-core nostalgia; blending innocence and disquiet. The uncanny, theatrical space mirrors Rafman’s practice of digital voyeurism: collecting, editing, and re-presenting found images and fantasies from the depths of online culture. The work’s strength lies in this doubling; the physical bedroom installation isn’t a lived site, but a material trace of desires, created and consumed at a distance. Artie Vierkant defines post-internet objects as works whose “particular materiality” is inseparable from “their vast variety of methods of presentation and dissemination”; they are made to be circulated more than inhabited, their affect produced as spectacle (Vierkant, 2010).

Emin’s My Bed, conversely, recontextualises a real space within the art gallery. By transplanting her unmade bed and its surrounding detritus into the white cube, Emin transforms a private, emotionally charged site into a public tableau. Her audience becomes a collective voyeur, confronted not with fantasy, but with the physical reality of lived crisis. The gesture is one of radical transparency, in which the gallery becomes a frame for self-exposure, and the viewer, implicated in the ethics of looking. Smith and Watson describe this tactic as “the rumpled bed of autobiography”, a form in which the disorder of domestic space challenges both narrative coherence and cultural scripts of femininity.

Emin’s bedroom invites empathetic identification and disrupts the aesthetics of cleanliness and control. Rafman’s imagined bedroom reveals how digital culture stages the domestic as a curated performance. His constructed room reflects the ways young women’s bedrooms are often consumed and replicated online as aesthetic tropes (saturated with fairy lights, pastel tones, and symbolic clutter) stripped of interiority and turned into an algorithmic style. By staging such a room, Rafman draws attention to his position not as insider, but as observer, replicating and aestheticising a form of femininity he cannot inhabit. As Judith Butler might argue, such performances of gendered space reveal not a stable identity but “a stylized repetition of acts” — a signifier of femininity produced for others rather than lived for oneself (Butler, Gender Trouble, 1990, 191).

This distinction matters. Emin speaks from the space she inhabits; emotionally, physically, culturally, while Rafman comments on a space he consumes. One reclaims; the other digests. Emin’s work is marked by the politics of presence while Rafman’s operates through mediated distance. As a result, Emin’s confessional staging subverts the gallery’s detachment, while Rafman’s installation uses simulation to highlight the flattening of experience in post-internet visual culture. McHugh emphasises that post-internet art often reflects “the exhaustion of being constantly online,” where images no longer refer to bodies but to a spiralling archive of representations (McHugh, Post-Internet, 2011).

Oh The Humiliation!

Shame, as both affect and strategy, operates centrally in the work of both artists. Emin lays bare the intimate contours of depression, heartbreak, and vulnerability. Her work invites empathy but also discomfort. Viewers are not merely witnesses; they are implicated. By presenting her bed in a public forum, she collapses the boundary between the personal and the political. As Berger reminds us, the act of making private space visible is not neutral; it is historically tied to systems of power and visibility that render some lives more legible than others (Berger, Ways of Seeing, 1972, 52).

Rafman’s approach to shame is more oblique. His avatars, grotesque and glitched, reflect a culture of suppressed affect. His work does not express shame so much as simulate the conditions that produce it: alienation, nostalgia, compulsive voyeurism. There is no singular self to confess but a stream of fragmented images and anonymised narratives. Rafman’s installations are haunted not by the presence of shame, but by its absence; by a cultural numbness that renders confession aesthetic rather than cathartic. Kristeva suggests that the abject “draws me toward theplace where meaning collapses,” and in Rafman’s worlds, meaning often collapses under the weight of surplus representation (Kristeva, 1982, 2).

One invites communion, the other distance. Both are valid, but their ethical stakes differ. Emin risks being dismissed as narcissistic and Rafman risks being complicit in the very alienation he portrays. Judith Butler helps us understand this in terms of performative legibility: “It is through the body that gender is performed, and it is only through certain legible performances that one is recognisable as a subject” (Butler, Gender Trouble, 1990, xxiv). Emin’s abjection becomes legible through pain and risk. Rafman’s bedroom refuses this legibility; it oscillates in an ambiguous space where subjectivity is flattened by aesthetic detachment.

What lessons can be drawn from these confessional modes? Emin teaches that shame, when externalised, loses its power. Her work is an act of survival, a refusal to be silenced by stigma. Rafman suggests that shame, when internalised and aestheticised, becomes a loop; an endlessly replayed simulation that neither heals nor resolves. In a 2023 interview, Rafman remarked, “I’m trying to reflect what it feels like to live in this world right now; overstimulated, fragmented, haunted by images you can’t explain” (Rafman in Interview Magazine, 2023). The psychic condition he identifies here is not redemptive. It is ambient, dissociative, and unresolved.

Now What?

In my current series, Framing Devices, I draw deeply from the lineage of confessional art and affective installation, tracing a lineage that includes both Emin’s embodied shame and Rafman’s digital estrangement. This series comprises assemblages of flattened personal ephemera, digital animations of imagined bedrooms, and mixed media textile works constructed from used bedsheets, items that carry the traces of shame, intimacy, and memory. Like Emin, I am interested in transforming the bedroom from a space of concealment to a space of confrontation. As Baydar writes, “By bringing the messiness of everyday life out of the closet, these artists make powerful statements” about the boundaries between public and private, and the feminised spaces traditionally excluded from serious art (Baydar, 2012, 33).

Objects such as pregnancy tests, food diaries, tabloid magazines, used condoms, diary entries, and food stains are not displayed for shock but arranged delicately, often alongside soft or meditative materials. The intent is to unearth shame not as spectacle, but as portraiture; a poetic framing of the conditions that shape my own becoming. This gesture echoes Emin’s insistence on the legitimacy of lived experience and the radical potential of reclaiming abjection.

My work also reflects Rafman’s awareness of how images shift in emotional register. The digital bedrooms in Framing Devices are fabricated but intentionally unstable. Walls flicker, objects sit unnaturally, proportions warp; mimicking both the aesthetic of online dreamscapes and the instability of memory itself. These spaces neither promise safety nor invite total immersion. They resist the polished escapism of Rafman’s installations, foregrounding instead the labor of reconstruction; piecing together a narrative through the debris of daily life.

The use of textiles (particularly stained or worn bedsheets) draws direct influence from Emin’s material honesty. Fabric functions as skin, archive, and barrier. It carries the imprint of the body while also suggesting concealment. Through stitching, layering, and hanging, I approach textiles as both medium and metaphor: a surface onto which intimacy is inscribed, a frame that structures the viewer’s engagement with objects of private shame. Rather than presenting trauma as collapse, Framing Devices seeks a language of meditation and growth. Assemblages are composed with care and stillness, positioning shame as a catalyst for transformation rather than paralysis. There is no cleansing of the past, but an invitation to see it anew.

If Emin’s installation screams and Rafman’s murmurs, Framing Devices breathes. The visual mess becomes a slow exhalation of experience, framed not as spectacle, but as ritual. Emin’s My Bed and Rafman’s Zabludowicz installation represent two poles of confessional art. Emin’s work is visceral, immediate, and deeply embodied. Rafman’s is distant, constructed, and controlled. Both reflect and shape contemporary understandings of selfhood, gender, and vulnerability.

By situating their practices in relation to one another, we see how confessional art evolves in response to changing technologies and cultural pressures. Emin reclaims the domestic as a site of feminist resistance. Rafman turns it into a stage for digital melancholy. Each offers a unique lens through which to view the politics of privacy, performance, and perception. Their art reminds us that confession is never just about the self. It is always about the audience, the space of display, and the systems of meaning that make certain disclosures legible and others unspeakable. As artists and viewers, we are invited to consider our own roles in this exchange, and to confront what we choose to reveal, conceal, or simulate.

-- Luckk

#academic art#confessional art#art journal#essay#art#jon rafman#tracey emin#artists on tumblr#art school#gender stuff#gender identity#sociology#confession#dissertation#thesis#old internet#post internet#contemporary art#nonfiction#thoughts#writing#fine art#analysis#media analysis#commentary#shame#textiles#textilart#digital art#diary

5 notes

·

View notes