Text

Screen-Printing

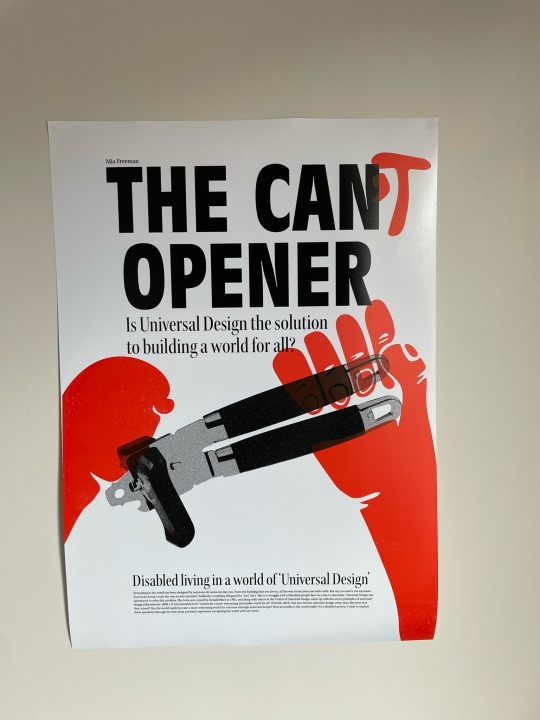

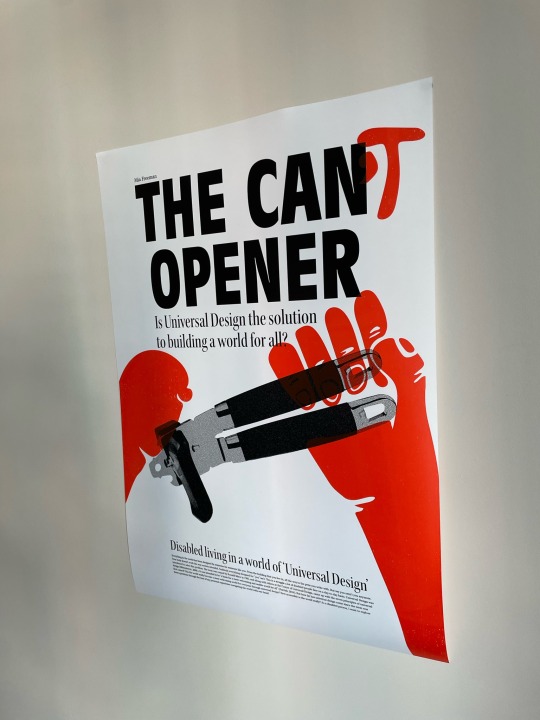

From the beginning of this project, I knew that I really wanted to try out screen-printing. I had never had the chance to do it before and I love the way it looks and textures it creates. My early research and visual mapping led me to keywords that included texture, so I wanted to incorporate this in my final poster design even if I wasn't able to in my research. The red hands and 'T' would be screen-printed over a black & white digital print to create that textured effect and look like someone had graffitied it over a product advert.

This is the screen-print without the digital print underneath on textured paper.

I'm really happy with how the screen-print turned out on the poster. It's really nicely textured and has that graffiti sort of feel to it which I really wanted to achieve through this way of printing. It also doesn't line up or over take perfectly which makes it feels super organic and I love the bright colours it was able to create. Really love how this turned out and I definitely want to try screen-printing more throughout my work.

0 notes

Text

Final Digital Poster

Based on my writing draft and contextual knowledge, I decided to change my question/title to better fit with the research I've done and the direction my writing is heading in. In my writing I talk more about universal design, the history surrounding it and how well it works as accessible design. The title "is universal design the solution to building a world for all?" fits this a lot better.

0 notes

Text

Poster Feedback

I briefly talked to David and got feedback on my poster developments.

Feedback

The bold type looks a lot better, gets your attention more

the can isn't working that well, feels like too much and the idea works better without it

Could even explore the option of completely removing the hands and human presence and just having the can opener

I tweaked the posters slightly based on davids feedback and looked at an option without the hands. I think this looks really clean but I prefer the hands, I think some people wont understand why it is the can't opener without the hands. I've decided to go with the left poster as my final design.

0 notes

Text

Further Developments

From Becky's feedback I developed the posters to these three options. I prefer the posters without the can, I think it makes the poster too literal and also too busy. The other posters aren't as obvious and also have more negative space which I like. Becky said she preferred the retro, thin type but I think the bold text looks better, it stands out more and has more of a visual presence. I also swapped the titles around like suggested and I think this works a lot better.

0 notes

Text

Poster Developments

From my feedback and research into 80's product adverts, I created these poster developments. I'm really happy with how all of these are looking right now, but i'm unsure which colour & composition I should further develop.

Feedback from Becky

red looks better than blue, feels more disruptive

Should include an apostrophe with the 'T' and overlap it other the 'can', it would be more disruptive and fit better with the protest theme of the poster.

the 'can' in a typeface with a hand drawn T looks a lot better than just having the word in a consistent still, feels better broken up

'How accessible is the world really?' acts as more of a title than "disabled living in a world of 'Universal design'" and should be heroed more

The retro style typeface works really well, ties really well to old product advertising

The composition of the text at the top and the illustration in the middle works better than having the illustration on top.

Would be cool to explore putting a can on the poster as well to really show that it can't be opened.

Based on this feedback I'm going to develop the bottom two posters and take the advice that Becky has given me.

0 notes

Text

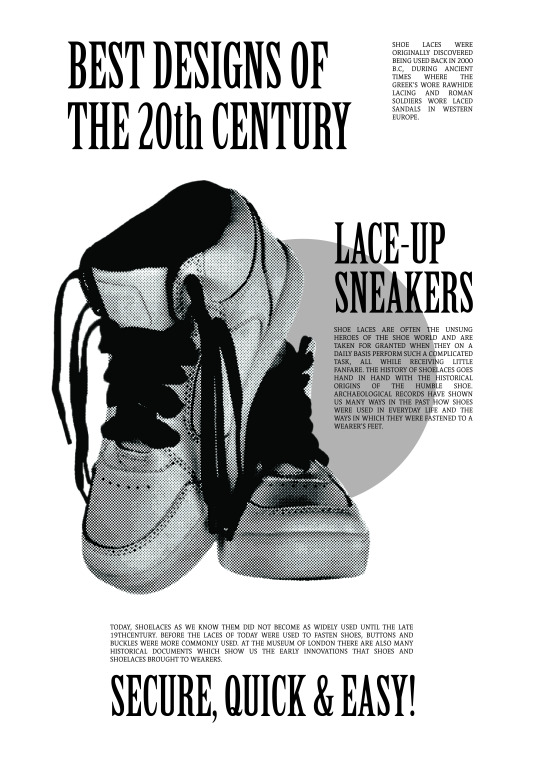

80's Product Advert Design

From my feedback on my current poster concept, I wanted to look at product advert design from the 80's. It was suggested that I could use the type and background composition to indicate a time or style. I want to connect my background to the 80's since the term Universal Design was coined in 1985. Connecting the background work with design from this time and then having a more modern illustration style over the top could indicate how the product and universal design were when it was first coined in 1985 to now.

They all have simple backgrounds, mostly white and a lot have a large serif typeface for the title. There is lots of negative space and the products are almost just floating in the background. Type is often centre aligned too.

I really like the converse poster, laying out my poster in this way could give me good room for my abstract.

0 notes

Text

Universal Design

Mitrasinovic, M., Erlhoff, M., & Marshall, T. (2008). Universal Design. In Design dictionary: Perspectives on design terminology (p. 419–422). Birkhäuser Basel. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7643-8140-0_290

"The term “universal design” was first coined by architect Ronald L. Mace in 1985. Universal design is also known as design for accessibility, design for all, transgenerational design, and inclusive design. Despite the terminological and sometimes normative differences, the ethical principles are analogous across countries and regions.

Universal design is not a specialised field of design practice but an approach to design, an attitude, a mindset conducive to the idea that designed objects, systems, environments, and services should be equally accessible and simultaneously experienced by the largest number of people possible.

Although the term would not appear until much later, the ideas behind universal design stand in the tradition established by scientists, researchers, engineers, and designers of the 1940s, who worked together in military-sponsored research units to provide design solutions for many of the engineering problems the Second World War had brought to light. Toward the early 1950s, these reflections on the Second World War experience had prompted several large research universities in Europe and the United States to conduct scientific studies on human performance and the man-machine relationship. During this period, Alexander Kira conducted well-known studies of lavatory use and sanitary equipment for the United States military, closely observing sanitary attitudes and corresponding behavior patterns of army personnel. Similar studies of office workers in task-specific environments were conducted across the world, particularly in the United Kingdom and Sweden."

This connects to a lot of the other research I've done, that the idea of universal design was only really considered after world war two, due to all the injuries soilders were coming back with.

"By the mid-1950s, the “systems approach” to design had brought together researchers in the areas of (→) human factors and engineering factors into the field of human engineering (also known as human factors engineering or (→) ergonomics), with the aim of creating optimal configurations of human and physical aspects of the man-made world in order to improve accessibility for people of all ages and across physical and mental abilities. The emerging term in common use at that time was “barrier-free design,” which usually meant modifying existing designs to allow for more appropriate and comfortable use by people with disabilities.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, government research centers and national organizations in Sweden, Denmark, France, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan conducted environmental studies and developed standards for (→) environmental design aimed at reaching a desirable balance between human performance and corresponding task environments, the so-called “environmental fit” or “good fit.” In 1977, Michael Bednar proposed that in order to achieve a desirable environmental fit for all users, all potential physical barriers had to be removed from the environment in the early stages of the (→) design process. One way of accomplishing that goal was to methodically involve endusers in the process of design. In the 1970s, Henry Sanoff initiated the Environmental Design Reseach Association, an organization that performed evaluative studies of architecture and environmental planning, and began developing (→) participatory design methods that involved a range of stakeholders in the early stages of designing.

In the mid-1980s, Ronald Mace and his collaborators at the University of North Carolina began arguing for more inclusive practices of environmental design that made both social and economic sense. A major milestone in this effort was the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, which renders illegal any discrimination based on physical or mental impairment that “substantially limits” human performance. In 1995, the analogous Disability Discrimination Act was passed in the United Kingdom. These acts changed the discourse on disability from one based on building codes and regulations to one based on civil rights and equal opportunities for all citizens. They also had a deep impact on the design industry; designers were expected and encouraged to integrate universal design as a mode of thinking into all stages of the design and production process, rather than a set of technical or normative requirements to be satisfied at the end. This mode of thinking extended beyond building design to the design of everyday objects and services traditionally covered by the (→) industrial design profession. A whole new market opened up for products such as OXO Good Grip potato peelers or public buses with floating floors and wheelchair access.

Today, with the growing life expectancy and aging demographics across the world, with an increasingly globalized economy, growing purchasing power and the emergence of consumer economies in the world's most populated regions, universal design is gaining in significance. In 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) established the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Rather than diagnosing people with stable disability conditions, this classification describes limited ability as a function of the capacity to perform specific environmental tasks. ICF views both disability and functioning as outcomes of the interactions between “health conditions” and “contextual factors.” These contextual factors include external environmental factors (social attitudes, material environment, legal and social structures, climate, landscape) and internal personal factors (demographic profile, past and current experiences, natural predispositions). Two important qualifiers regulate the essential information about disability and health: the “performance qualifier” describes what an individual does in his environment, and the “capacity qualifier” describes an individual's ability to execute a specific environmental task. The “gap” between capacity and performance points to the misfit between human beings and their environment: if, for example, capacity is greater than performance, then some aspect of the environment de facto disables optimal performance outputs.

As with the anti-disrimination acts of the 1950s, ICF is indicative of a shift in the way the world understands and defines disability today. The contemporary understanding is based on the belief that everyone at some point in their lives experiences reduced functionality; aging, farsightedness, back problems, and immobility can all contribute to a misfit with the surrounding environment. Disability, therefore, is a universal human experience that depends on the context, time, and circumstances of social and professional practices. In that respect, the role of universal design is, as Ronald Mace wrote, to promote the “design of products and environments to be useable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.”

0 notes

Text

Poster Developments & Feedback

Based on my last feedback from David, I refined my poster a lot and calmed it down to be a lot more minimal. I changed the shoes to a can opener because I very recently had to use a can opener by myself for the first time and released I could not use it at all by myself. I had to open the can buy just stabbing it with a knife instead. In my opinion, this product is a better representation of things I can't use.

Feedback

the poster looks a lot like a movie poster, so might need to be careful about this

Right now you have a straight image so it needs to be paired with more a bent headline, this could be achieved just by removing the underneath word 'can', and leaving just the can't

Should consider more the era that the type and design systems are referring to, it would be good to connect them to a significant time

0 notes

Text

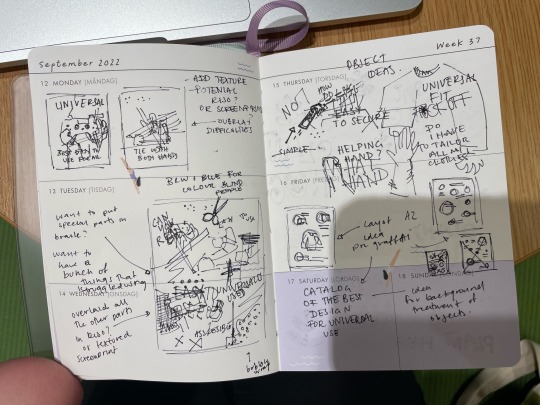

More Poster Exploration

In tutorial we did a task creating poster thumbnails really quickly then moving on to develop them in an analog way. I was focusing on the idea that I started exploring on monday, advertising objects I've struggled to use and then writing over the top the way I've experienced them.

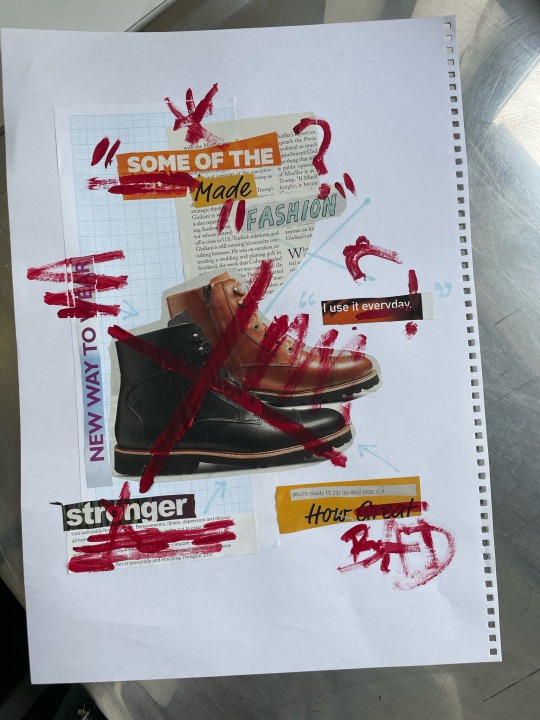

In the analog creation part I made this collage focusing on lace-up shoes. In my positioning the researcher draft I talked about how it took me a long time to learn how to tie my shoes with one hand, so I wanted to create something off the story.

I also made a digital version with the advertising part being printed black and white and then scribbling over it in coloured markers. I really like the effect of this, having the scribbled parts be a different media/texture. I want to try potentially screenprinting or riso printing my final poster over a black and white digital print to create a layered effect like this.

Feedback from David

Good concept and idea but can be refined back a lot more, something more simplistic and impactful might work better

Doesn't need as much background information in the black and white part, can just be a photo

the scribble part over the top is just too busy right now, needs to be taken back a bit

Could use a photo of a pair of your old shoes and then layer over the top

0 notes

Text

Poster Concept Exploration

I wanted to start exploring potential ideas for my poster design. When I started drafting my positioning the researcher writing I talked about some of the things I've struggled using that are more universally used. I want my poster to kind of explore this idea, looking at objects that I struggle using now or in the past.

0 notes

Text

Universal Design and the Problem of “Post-Disability” Ideology - Part 3

Hamraie, A. (2016). Universal Design and the Problem of “Post-Disability” Ideology. In Design and Culture (pp. 285-309). https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2016.1218714

Disabling Universal Design

Far from mere semantic differences or verbal slippages, the above examples reveal the continued influence of early rehabilitation models on Universal Design discourse and marketing concepts. Post-disability ideologies presume that disability-based discrimination in built environments is inconsequential or nonexistent. Despite their intention to persuade critics of Universal Design’s value, proponents have not challenged misconceptions and assumptions about disability that drive opposition to accessibility. Similar to imperatives for diversity and inclusion that remain neutral on issues of power and privilege (and accordingly, reinforce hierarchies) (Ahmed 2012, 57), Universal Design has become emblematic of a depoliticized orientation toward disability, which invokes human variation as a value but refuses to understand difference as tied to systems of oppression such as racism, sexism, or ableism.

The question remains: can Universal Design discourse embrace, preserve, and celebrate disability, rather than promoting its elimination? If architectural features are forms of material discourse, the Ed Roberts Campus building in Berkeley, California (Figure 3) provides an instructive example (Pill 2015). The building’s design argues against the ideologies of ability and discrimination exemplified by Sunaura Taylor’s cartoonish red stairs. Exterior glass panels and steel beams reveal a bright red ramp torqued between the first two floors. The wall of windows and a circular skylight encase the ramp’s bright panels and suspended cables with natural light. Inside the atrium, disabled and non-disabled people use the ramp as a surface on which to roll, walk, and dwell as they travel to offices or the transit system below. In the background, a fountain creates soothing sounds and helps to orient visitors within the space. Bathrooms with automatic doors and foot-operated controls signal the inclusion of multiple ways of moving through the world. A recent exhibit by the Paul Longmore Institute, Patient No More, utilized the building’s structure to convey the story of radical disability rights protestors occupying federal buildings to demand accessibility laws. Rather than making accessibility invisible, the exhibit and these design features showcased disability as an aesthetic and functional resource (in a manner similar to Amanda Cachia and Sara Hendren’s design of the alterpodium, described in Cachia’s piece in this issue). These design strategies signal disability acceptance and materialize the aspiration for accessible futures. Similarly, a discourse of Universal Design informed by critical disability theory, rather than the ideology of ability, would realize proponents’ underlying aspirations for the approach. Such a discourse would claim disability, treat disabled users as valuable knowers and experts, understand accessibility as an aesthetic and functional resource, and foreground the political, cultural, and social value of disability embodiments.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Universal Design and the Problem of “Post-Disability” Ideology - Part 2

Hamraie, A. (2016). Universal Design and the Problem of “Post-Disability” Ideology. In Design and Culture (pp. 285-309). https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2016.1218714

Universal Design in the Post-ADA Era

A turning point came in 1990 when, through the ADA, disabled people gained civil rights to employment, government services such as public transportation, and access to restaurants and other public spaces. Although the ADA intended to address pervasive discrimination against over 50 million US citizens with disabilities, the law faced resistance from architects and designers who insisted that accessible design would hamper their creative processes and increase costs (Reno 2000). Universal Design advocates across the fields of architecture, product design, web design, and interior design countered that more accessible built environments would benefit all people. Universal Design became a convenient marketing discourse for persuading architects and designers of the desirability of accessible design.

The Return of Post-disability Ideology

Paradoxically, disability began to disappear from the discourse of Universal Design in the post-ADA era. The term “Universal Design” entered the mainstream vocabulary, appearing in design newspapers, magazines, and handbooks as a signifier for a shifting array of meanings, from design that complies with the ADA to design that eschews the category of disability (Pell 1990; Remich 1992). Universal Design’s departure from disability rights discourses in the post-ADA era rested upon the assumption that civil rights legislation had adequately addressed ableism by creating an equal playing field between disabled and non-disabled people, such that it was no longer necessary to discuss oppression based on disability.

Because the ADA marked the beginning of meaningful, enforceable civil rights, rather than an end point, this assumption had significant consequences. Within Universal Design discourse and practice, it led to the reemergence of “post-disability” ideologies, which imagined a world without disability and denied the existence of disability discrimination. My framing of post-disability ideologies in the 1990s and 2000s builds upon critical race theory’s challenges to “post-racial” ideologies, which insist that racism is no longer a significant system of oppression because civil rights laws have ended material manifestations such as segregation. In the aftermath of the civil rights era, as Michelle Alexander (2012) has shown, race-neutral policies merely hide racial inequality within new institutions of mass incarceration. Likewise, legal scholars and philosophers argue that formal requirements for equality do not guarantee substantive changes and meaningful access – a critique that parallels Mace and Lusher’s challenges to minimal guidelines and accessibility codes in the pre-ADA era (Silvers 1998, 13–53). Disability media scholar Elizabeth Ellcessor (2015) writes that treating oppression as inconsequential does not “reduce prejudice, discrimination, or stigma. Instead, such assertions may protect and extend racist or ableist structures, by failing to interrogate, alter, or demolish them.” In its material practices, Universal Design has aspired to produce the kinds of accessible built environments that the ADA was meant to provide, replete with curb cuts, built-in ramps, and multi-sensory displays. However, in the post-ADA era, the discourse of Universal Design often disavows a relationship to disability (as a user group or a civil rights category), eschews a notion of disabled people’s expertise, and infrequently challenges ableist assumptions about disability (Hamraie 2013; Williamson 2012a, 232–233).

Disability-neutral Discourse

Recall that disability activists of the 1970s (as well as Mace and Lusher) reframed accessibility for disabled users as “good design,” specifically in response to designers’ claims that disability would reduce the aesthetic value and creativity of design. Following the ADA, Universal Design advocates began using the phrase “good design” to describe a very specific, value-laden approach to accessibility, which called for greater functionality and usability but adopted disability-neutral language and thus failed to distinguish between marginalized users and the broader non-disabled consumer majority. Disability-neutral terms such as “all users,” “everyone,” or “the entire population” appeared as a point of contrast with barrier-free design and its focus on disabled users. For instance, a group of proponents released Principles of Universal Design 2.0 in 1997 (Figure 2), redefining the approach as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design” (Center for Universal Design 1997). The Principles offered guidelines for Universal Design in “all design disciplines, including those that focused on built environments, products, and communications” (Story 2011, 4.3). Despite Mace and Lusher’s involvement, the Principles were an artefact of the post-ADA era, distancing Universal Design from the perceived stigma attached to accessibility. As Molly Story (2001, 10.6) documented it, “Equitable Use” was the last addition to the Principles, with guidelines for “Flexibility in Use” and “Simple and Intuitive Use” being among the first to be developed.

By the late 1990s, Mace himself shifted his focus to emphasizing Universal Design as a “marketing concept” (Mace 1994, 6). At a symposium on teaching Universal Design, he claimed, “Its what designers think they’re doing anyway, but sometimes they’re not, because they don’t include the full spectrum of human needs and abilities in what is being built” (6). This framing made clear that Universal Design discourse revolved as much around the politics of defining meaning as it did upon changing the material practices of design. When framed through “post-disability” ideologies, however, Universal Design’s marketing often defaulted to disability-neutral discourses. In the 2000s, the language of Universal Design advocacy turned toward distinguishing Universal Design from accessibility and disability rights in handbooks and design media. Architect Denise Levine wrote in 2003:

Accessibility is a civil rights issue focused on eliminating discrimination against one minority group. In contrast, universal design is a market driven concept. Rather than responding to legal mandates, it reflects the realities of contemporary societies with their diverse populations. Instead of a focus on one minority group, universal design is an inclusive approach that benefits the entire population. (Levine 2003, 8)

Notably, Levine frames Universal Design as a marketing concept rather than a civil rights concern – a framing that explicitly divorces Universal Design from the politicized work of disabled designers and activists, as well as from the notion of disability as a marginalized identity. This framing contrasts with Mace and Lusher’s emphasis on disability as a resource for alliance between marginalized users by framing Universal Design as primarily for the benefit of non-disabled users. Similarly, the conflation of accessibility with “legal mandates” represents the social value of disability inclusion as necessarily onerous and bureaucratic.

Levine (2003, 9) acknowledges as a myth the assumption that the ADA has “created equality, so there is no need to do any more,” arguing that Universal Design goes beyond the ADA’s focus on physical and sensory “limitations” by focusing on a broader array of functional limitations “in the way people think and interpret things.” She goes on to argue: “Throughout our lifespan, we all experience variations in our abilities. In fact, more than 50% of the U.S. population could be characterized as having some sort of functional limitation. Therefore, universal design eventually benefits all of us.” Here, it becomes evident that Levine is not arguing against post-disability frameworks or in favor of accessibility as a disability right. Rather, she frames Universal Design as a necessary imperative for moving beyond the ADA because of the purported universality of functional limitation.

From the perspective of critical disability theory, however, conflating any type of imperfect user experience with marginalization and disability treats identities and embodiments as untouched by power and privilege. This conflation risks “erasing the line between disabled and non disabled people” (Linton 1998, 13) by assuming that everyone is or will become somewhat functionally limited at some point and implying an equal playing field in user experiences of design. It suggests that enhancing usability or convenience for normate users is a social goal equivalent to addressing discrimination against misfitting users. Disability scholar and activist Simi Linton (1998, 13) argues that when taken for granted as common sense, such erasures are depoliticizing, particularly “as long as disabled people are devalued and discriminated against, and as long as naming the category serves to call attention to that treatment.”

By framing diversity as a marketing concept but omitting mention of disability politics and culture, disability-neutral discourses reduce functional limitation to an impartial demographic category. It may appear that encouraging non-marginalized consumers to buy Universal Design products fosters empathy and serves as a reminder of their potential future disablement. Critical disability theorists point out, however, that framing Universal Design as having (what I term) “added value” for non-disabled people privileges convenience for normate consumers over accountability toward those who are excluded – in the present – from built environments (Hamraie 2013; see also Williamson 2012b, 233). It equates the commercial imperative to enhance middle-class, non-disabled users’ experiences of products and homes with the social and political imperative to grant disabled people the right to live outside nursing homes and institutions, find employment outside sheltered workshops, and be recognized as citizens and users of public space. Disability-neutral discourses of Universal Design that adopt marketing logics thus presume that disability-based discrimination in built environments is inconsequential or nonexistent.

Furthermore, when advocates focus on disability as functional limitation divorced from minority culture and politics, they preclude critical disability, Deaf, and neurodiversity perspectives on accessibility as a tool for preserving and accepting human diversity. Contemporary Deaf and Autistic scholars assert that broad differences in how people think about and interpret the built environment are irreducible to functional limitations, but can be the basis of shared culture – such as when members of Deaf culture use the spatial practice of sign language to communicate, rather than adopting cochlear implants and other medical interventions, or when Autistic adults form communities on the Internet, rather than undergoing therapy to enable normative verbal communication and eye contact in non-Internet social spaces (Bauman and Murray 2014, xxi–xxii; see also Kapp et al. 2013; Sinclair 2012, 2). Additionally, the notion of universal functional limitation does not capture the sense of affiliation between marginalized users that drove early Universal Design. In Mace and Lusher’s formulation, Universal Design foregrounds disabled users and children, the elderly, and people of different sizes without equating these categories to one another. Because they do not begin from an analysis of oppression, disability-neutral discourses fail to capture the relational ethics of disability culture. Nor do they foster a broad, politicized sense of misfitting as a basis for collective organization for structural change (Garland-Thomson 2011, 547).

Anti-disability Discourse

Although Universal Design advocates’ post-disability ideologies stem from attempts to persuade architects and designers to create a more just world for everyone, the consequences of these positions become obvious when disability-neutrality shifts into positions that more directly stigmatize disability. In a 2011 interview with Metropolis Magazine, architect Josh Safdie captures the discursive slippage between disability-neutral and anti-disability positions:

The biggest ‘barrier’ to a richer understanding and more widespread application of Universal Design here in the US – and in particular among architects and planners – is the conflation of Universal Design with accessibility and, more specifically, the ADA Standards for Accessible Design. … [W]e have developed a broader definition of Universal Design that focuses on its role as a facilitator of human experience and performance. … This definition builds upon the World Health Organization’s formal classification of disability as a contextual phenomenon which occurs at the intersection of the user and his or her environment(s). For me as a designer, this is an incredibly powerful idea: that through the design of thoughtful environments – ones which anticipate and celebrate the diversity of human ability, age, and culture – we have the capacity to effectively eliminate a person’s disability. (Safdie and Szenasy 2011)

This statement clearly indicates support for (rather than resistance toward) the project of Universal Design. Safdie’s interest is in creating environments that “anticipate and celebrate” a wide range of diversities. His oppositional framing, however, reveals the persistence of post-disability and rehabilitation logics within this value-laden discourse. Safdie borrows the term “barrier” from barrier-free design to position accessibility as antithetical to the “design of thoughtful environments,” a concept closely aligned with the notion of “good design.” Compared to the disability rights position that disability access (beyond imperatives for normalization and assimilation) should be considered as part of designers’ standards for “good design,” he conflates the social goal of disability access with the bureaucratic enforcement of the ADA, and thus disqualifies considerations of justice in built environments for disabled people from good design. If Universal Design is “thoughtful design,” disability access becomes characteristic of bad design – thoughtless compliance with checklist-style standards. Design that thoughtfully values or preserves disability becomes unthinkable in this logic, while eliminating functional or apparent disabilities becomes a priority.

While the term “diversity” might indicate acceptance of variability and read as a pro-disability position, it coexists with (and distracts from) the explicit call to “eliminate a person’s disability” (understood as functional limitation) through good design. The call “to eliminate disability,” argues Kafer (2013, 83), “is to eliminate the possibility of discovering alternative ways of being in the world, to foreclose the possibility of recognizing and valuing our interdependence.” When architects and designers claim to eliminate disability through better design, their presumption is that a life with disability is begging for correction. This presumption resonates with the eugenic logic of streamlining and the rehabilitation logic of normalization, both of which frame disabled lives as inherently limited, tragic, and undesirable. As Barbara Gibson (2014, 2) argues in relation to rehabilitation metrics and the goal of eliminating disability in order to reinstate independence: “The idea that independence is good (desirable, preferable), and dependence is bad (undesirable, to be avoided) is not a given, but relies on a particular normative understanding of the subject and what constitutes a good life.” If ableism is the belief that ability is better than disability and that disability must be eliminated, then arguing that disability is a “contextual phenomenon” (or functional limitation) that thoughtful design can “eliminate” has the unintended effect of aligning Universal Design with post-disability logics, rather than with disability acceptance. What is lost is, ironically, precisely what Universal Design discourses appear to promise: a world that is designed with everyone in mind.

Reinforcing the ideology of ability, “disability” appears as an object of elimination, while Safdie offers “human ability” as a condition that designers must anticipate and celebrate. However, elevating design for “the diversity of human ability, age, and culture” to the status of good design reinforces the binary between valued ability and devalued disability. The term “human ability” operates as a euphemism for disability, much like the terms “physically challenged, the able disabled, handicapable, and special people/children” (Linton 1998, 14). While this language appears to “refute common stereotypes of incompetence,” Linton writes that these are “defensive and reactive terms rather than terms that advance a new agenda” such as disability acceptance.

Critical disability theory offers that when advocates proclaim that Universal Design “does not discriminate against users based on their ability” (McAdams and Kostovich 2011), the reference to disability as “human ability,” no matter how diverse, does not challenge discrimination based on disability. Instead, it centers the norm of able-bodiedness and denies the value of disability as a way of being non-normate. Ability is already considered a normal, desirable, and default state of being: people are rarely discriminated against because of their abilities. Rather, it is the perception of disability as a devalued state of being that leads to discrimination. Centering design for ability replicates the disability-neutral position that Universal Design should respond to “diverse populations” without naming these populations or considering the degrees of marginalization that separate them. Like post-racial arguments that race is biologically nonexistent and that all people are thus de facto equal, the notion that more thoughtful design can (and should) eliminate disability ignores the persistence of inequality, devaluation, and disqualification that would remain even if more inclusive consumer products were made available to people of all “abilities.” Consequently, disabled people are not merely functionally limited in a vacuum, separate from issues of economic access, racial belonging, or gender identity. Even for those whose disability is (supposedly) eliminated through a better fit between body and environment, issues of affordability, perceived belonging among the cadre of desired users, and access to jobs and housing will still remain (Mingus 2010).

1 note

·

View note

Text

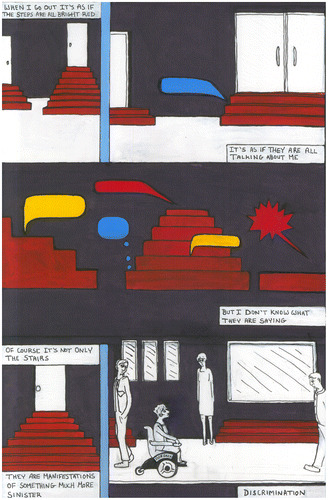

Universal Design and the Problem of “Post-Disability” Ideology - Part 1

Hamraie, A. (2016). Universal Design and the Problem of “Post-Disability” Ideology. In Design and Culture (pp. 285-309). https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2016.1218714

"Disabled artist Sunaura Taylor’s Thinking Stairs (Figure 1) depicts a gray-scale sidewalk flanked by cartoonish red staircases emitting empty speech bubbles. The landscape appears disembodied, impartial, until the final frame, in which Taylor herself appears as a black and white figure driving her powerchair amid staring pedestrians. Wordlessly, the stairs communicate what the people – and their stares – do not: Taylor is out of place. This world was not built with her in mind."

"Twenty-six years after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990, discriminatory features endure in built environments, and accessible design remains marginal within mainstream design practice and theory. Indeed, design scholars and practitioners rarely recognize disability narratives, such as Taylor’s, as valuable sources of architectural and design critique. The discourse of Universal Design, however, gains popularity in design criticism, journalism, and scholarship as a common sense strategy for making built environments more usable for all people.1 While few would object to the promise of a more usable world for everyone, I argue that the portrayal of Universal Design as simply a form of neutral, common sense “good design” (and not design that ensures accessibility for disabled users) distances this approach from the civil rights mandates of the ADA and, by extension, from the notion of disability itself."

Critical Disability Theory

"The field of Disability Studies coalesced in the 1980s around the “social model of disability,” which critiqued medical and rehabilitation models of disability (Oliver 1990, 22; Union of Physically Impaired Against Segregation 1972, n.p). According to the social model, disability is an experience of discrimination resulting from inaccessible built environments, rather than an inherent pathology or impairment in the body. More recent critical disability theories, however, argue that the social model’s sole focus on the functionality of built environments does not go far enough to challenge the cultural logics of ableism. Ableism, or the “ideology of ability,” dictates that life without disability is preferable to life with disability (Siebers 2008, 8). When societies frame disability as deviation from dominant norms and therefore “a problem to be eradicated,” critical disability theorist Alison Kafer (2013, 8–10) explains, “ableist understandings of disability” appear as “common sense,” while the notion of preserving or even desiring disability appears as pathological or unthinkable. Disability has thus become a “master trope of human disqualification,” a concept whose presence is treated as a de facto problem to eliminate (Mitchell and Snyder 2006, 125).

Critical disability theorists emphasize instead that the design of “habitable worlds” must involve treating disability itself as a valuable way of being in the world, one that societies must work to accept and preserve rather than cure or rehabilitate (Garland-Thomson 2014, 300). A habitable world, in other words, would offer more inclusive ideological assumptions about disability, and not simply more accessible structures. Attention to cultural representations of disability has been largely missing from Universal Design discourse, however. Proponents often treat Universal Design as a de facto good, untouched by broader social and political forces, and neutral toward disability. Critical disability theory, by contrast, offers historical and theoretical tools for examining the persistence of ableism in contemporary Universal Design discourses."

Design and Disability in the Pre-ADA Era

"Debates about Universal Design’s relationship to disability often treat accessible design as a stable, ahistorical phenomenon. This presumed stability enables advocates to frame Universal Design as an objective example of “good design” and accessible design as a manifestation of “bad design.” Design historian Stephen Hayward (1998, 222) argues, however, that since its emergence in the 1930s, the representation of “good design” as “common sense” has been an “exercise of power, concomitant with a hegemonic idea of progress or modernity, and the antithesis to a contrary world of ‘bad’ or ‘uncultivated’ design.” Accordingly, understanding Universal Design’s seemingly neutral claim to be “good design” requires a more critical engagement with issues of history, power, and privilege surrounding the concept of disability. When informed by critical disability scholarship, this kind of engagement can also help distinguish the intentions underlying Universal Design discourses and the consequences of these discourses for disability inclusion or exclusion."

Eliminating Disability

"In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, design, medicine, and state power converged around the project of eliminating disability. Thousands of people with supposed cognitive and physical defects (presumed to be excessively dependent or incapable of becoming productive citizens) were incarcerated or sterilized in US institutions; these spaces subsequently provided templates for Nazi eugenics programs (Chapman, Carey, and Ben-Moshe 2014, 6–7; Friedlander 2000, 7–9; Johnson 2003; Mitchell and Snyder 2006).3 Together, eugenics and institutionalization separated disability from public life, rendering the presence of disabled bodies in public space unthinkable and reinforcing the association between disability and disqualification. When treated as common sense, the violence of eliminating disability appeared instead as a “humanistic solution to a social crisis” (Mitchell and Snyder 2003, 85).

Disability historians have shown that this imperative to eliminate disability – to imagine what I am calling a “post-disability” future, in which disability no longer poses a “problem” – extended to standards of “good design.” Eugenicists defined “degeneracy” and “feeblemindedness” (often described as a lack of common sense and intelligence) by measuring an individual’s ability to cope with the design of urban settings (Mitchell and Snyder 2003, 84–85). So-called “ugly laws” prohibited people with atypical bodily features from inhabiting public places. These laws, Susan Schweik (2009, 5) argues, targeted the figure of the “unsightly beggar,” a figure often imagined as a disabled panhandler, but revealed a broader ideological investment in individualism, “which enabled the law’s supporters to position disability and begging as individual problems rather than relating them to broader societal problems,” such as economic and racial inequities. Industrial designers in the 1930s, according to Christina Cogdell (2010), drew upon eugenic goals of culling disabled, non-white, and poor people from the human stock to inform their elimination of aesthetic and functional excesses from “streamlined” consumer products. Twentieth-century architectural handbooks adopted human statistics (derived from military and eugenics research) as standards for the typical inhabitant of architectural structures, and thus reinforced norms of race, gender, and ability (Hamraie 2012; Hosey 2001, 103). When defined by a preference for able-bodied users, “good design” relied upon what Rosemarie Garland-Thomson (2012, 340–341) calls the “eugenic logic” of disability elimination. It easily reinforced the ideology of ability by presenting inaccessible built environments (and the subsequent exclusion of disabled users) as part of the natural order of things, as common sense and untouched by power.

The accessible design movement in the United States (known as “barrier-free design” beginning in the 1960s) emerged through early and mid-twentieth-century efforts to include disabled citizens in public life (Fleischer and Zames 2011, 36–37; Penner 2013, 215–217). Early accessibility sought to expose the norms of embodiment around which architecture and design cohered. However, early advocates focused on troubling the exclusion of disability from standards of normalcy rather than challenging the imperative for normalization itself. In the post-World War II era, accessible design quickly became entangled with economic, medical, and military imperatives to create productive bodies and healthy citizens.5 The return of injured soldiers from war renewed efforts at normalizing bodily function through medical and vocational rehabilitation, rather than through the social acceptance of atypical embodiments (Serlin 2004, 12). Rehabilitation experts and scientific managers such as Edna Yost and Lillian Gilbreth (1944) and Howard Rusk and Eugene Taylor (1949), and industrial designers such as Alexander Kira (1960) believed that when fitted with the correct tools, amputees, paraplegics, and other disabled veterans could become productive workers and citizens (Williamson 2012b, 215). Accessibility advocates argued that inclusive built environments with features such as wheelchair ramps, folding shower seats, elevators, grab bars, and wide doorways would grant disabled people access to public life, employment, education, and housing (Nugent 1960; Rehabilitation Services Administration 1967). Given the right equipment and appropriate built environment, injured soldiers could work in factories, drive automobiles, and realize the American Dream. Disabled people, in other words, could become normal by design (Serlin 2004, 27).

Rehabilitation experts, rather than designers and architects, produced the first accessibility standards in the US. At the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana in the late 1950s, researchers such as Timothy Nugent enlisted disabled students (often veterans attending university through funding from the GI Bill) for research on features such as ramps (Fleischer and Zames 2011, 36; Pelka 2012, 94–112). Thereafter, Nugent (1960, 53) wrote that rehabilitation professionals “are finding it very difficult to project clients into normal situations of education, recreation, and employment because of architectural barriers,” adding that “solution of these problems is not within the realm of professional rehabilitation workers but must be accomplished by … the architects, engineers, designers, builders, manufacturers, and in all probability, the legislators, with encouragement and guidance from those professionally engaged in rehabilitation.” Rehabilitation concepts and data were thus brought to bear on architecture and design practices, similar to the influence of ergonomics and human factors data on the field of industrial design through the work of Henry Dreyfuss (1960).

Though rehabilitation professionals were not architects, their evolving theories of disability involved the interactions between individuals and built environments. A key rehabilitation concept was the notion of “functional limitation,” or the environment’s effect on a person’s ability to engage in life activities such as eating, cleaning, or working (Hahn 2002, 162–189; Institute of Medicine 1997, 148). According to an influential model proposed by medical sociologist Saad Nagi in 1965, functional limitation was situational and distinguished from the categories of “pathology” and “impairment,” which presumed defects inherent to individual bodies (Nagi 1991, 309–327).6 The shift to understanding functional limitation as distinct from pathology or impairment appeared progressive in the sense of rejecting medical and curative approaches to disability. Nevertheless, it followed from the functional limitation concept that disability was a problem to eliminate, and the concept thus maintained an attachment to what Robert McRuer (2006, 2) calls “compulsory able-bodiedness.” Accessibility practices premised upon functional limitation likewise positioned architects, industrial designers, and engineers (rather than physicians) as experts with the tools to correct perceived limitations in a user’s performance in the name of productivity, thereby reinforcing ideologies of ability (Williamson 2012b, 216).

Preserving Disability

Concurrent to the rise of barrier-free design, disabled people responded to rehabilitation and eugenic logics of elimination with demands for acceptance and preservation. Beginning in the 1960s, disability communities responded to institutionalization by forming mutual aid networks, sharing knowledge, and crafting strategies to survive in existing built and social environments (Williamson 2012a, 8). Deaf and hard-of-hearing people formed culture around the shared use of American Sign Language (ASL) (Van Cleve and Crouch 1989). While targeted by eugenicists and often forced into schools that emphasized lip reading and spoken communication, deaf people formed activist networks to reject assimilation and emphasize the unique cultural, spatial, and ethical orientation of ASL communication (Silvers 1998, 71).7 In communities of people with mobility impairments, wheelchairs and crutches became aesthetic and functional tools for dance and sports (Lifchez and Winslow 1982, 154–155). Self-taught design practices were often central to disability cultures. As Bess Williamson (2012a) has shown, people with post-polio disabilities and their families, for whom the mainstream of “good design” was not accessible, shared tips for tinkering with assistive devices, wheelchair ramps, and automobiles through newsletters and social networks. The disability culture that emerged from these efforts offered a view of disability as culturally vibrant and politically resourceful. Disability culture embraced a “counter-eugenic logic,” according to which societies should embrace, rather than eliminate, disabled people’s unique ways of relating to and engaging with one another (Garland-Thomson 2012, 341). When disabled people created culture and community, they challenged the association of disability with tragedy, pain, and decreased quality of life.

Disability activists of the 1960s and 70s imagined a future centered on the needs and expertise of disabled people, rather than compulsory rehabilitation and normalization. The Independent Living movement, for instance, positioned disabled people as experts about their own experiences, worked to liberate disabled people from institutions and nursing homes, emphasized mutual aid, and promoted the value of interdependence (Pelka 2012, 113–130; “The University Picture” 1962). Unlike rehabilitation experts who sought accessibility as a tool for normalization, and unlike mainstream architects and designers who understood accessibility as antithetical to creative and aesthetic choices, disability activists claimed their expertise as users of built environments to justify their authority to redefine “good design.” Architects Raymond Lifchez and Barbara Winslow capture this emerging disability design philosophy in their landmark Design for Independent Living, which catalogues the accessible design efforts of the Independent Living movement in Berkeley, California. They write: "Is the objective to assimilate the disabled person into the environment, or is it to accommodate the environment to the person? … Currently, the emphasis [in barrier-free design] is on assimilation, for this seems to assure that the disabled person, once ‘broken-in,’ will be able to operate in a society as a ‘regular person’ and that the environment will not undermine his natural agenda to ‘improve’ himself. … [T]his assumption can be counterproductive when designing for accessibility. It may serve only to obscure the fact that the disabled person may have a point of view about the design that challenges what the designers would consider good design. Many designers have, in fact, expressed a certain fear that pressure to accommodate disabled people will jeopardize good design and weaken the design vocabulary. Though certain aspects of the contemporary design vocabulary may have to be reconsidered in making accessible environments, one must also look forward to new items in the vocabulary that will develop in response to these human needs – ultimately leading toward more humane concepts of what makes for good design. (Lifchez and Winslow 1982, 150)"

In other words, activists redefined “good design” as accessibility and social inclusion for all disabled people, regardless of their productivity or conformity to dominant standards of citizenship. This position built upon the social model of disability, which defined the social exclusion of disability as environmentally produced, rather than a common sense or natural occurrence resulting from flaws in individual bodies.8 The key difference between the social model and the “functional limitation” model, however, was the new emphasis on disability as a cultural resource that should be valued and preserved through accessible built environments.

Several practical and conceptual concerns limited the success of accessible design in the 1970s and 1980s. Despite the passage of laws such as the Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 and Section 504 of the Federal Rehabilitation Act, enforcement remained limited or non-existent (Jeffers 1977). When these laws were enforced as a result of high-profile activist protests and sit-ins, their enforcement mechanisms – standardized codes and checklists – prioritized the needs of specific disabled people – particularly wheelchair users – who had been subjects of rehabilitation research. This was evident in the way that wheelchair users became emblematic of the broader disability community with the adoption of the “International Symbol of Access” on accessible parking placards and other signage (Ben-Moshe and Powell 2007, 500; Guffey 2015, 359–360). More expansive guidelines would be necessary to facilitate inclusion for people with other (or additional) physical, sensory, or cognitive disabilities. Finally, accessibility standards reduced disability to functional limitations that could be addressed through checklists solutions such as ramps of a certain slope or doorways of a certain width. They did not, however, promote a cultural or disability rights model that would emphasize qualitative dimensions of meaningful accessibility or creative design beyond minimal standards (Mace 1977, 160–161). These specific concerns involving bureaucratic codes, standards, and legal compliance approaches to accessibility culminated in a new discourse: Universal Design.

Foregrounding Disability

Universal Design emerged from the work of disabled designers who lived through the struggles over enforcing accessibility codes in the civil rights era. Ronald Mace, a disabled architect and wheelchair user, had direct experience with long-term hospitalization, exclusion from schools, and employment discrimination.9 In the late 1970s, he became involved with efforts to write new accessibility codes and educate architects and designers about best practices, but these experiences with bureaucratic compliance cultures left him frustrated (Mace 1980). Mace (1985, 147) coined the term “Universal Design” in 1985 to describe “a way of designing a building or facility, at little or no extra cost, so that it is both attractive and functional for all people, disabled or not.” His article “Universal Design: Barrier Free Environments for Everyone” framed accessibility as a requirement for “good design” (just as disability activists had done in the late 1970s) (152).

Mace’s (1985, 152, 148) concept expanded the focus of barrier-free design to a broader population of marginalized users of built environments, from “young people with moderate mobility impairments [who] are placed in nursing homes” to “older couple[s]” to temporarily disabled workers and deaf or hard-of-hearing people. Mace also sought to expand accessibility by framing it as a necessarily interdisciplinary phenomenon involving architects, product designers, engineers, builders, and manufacturers alike in the process of building more accessible built environments as coordinated systems (148, 152). This interdisciplinary approach to “good design” pushed beyond checklist-style standards by requiring an understanding of how component parts of a space work in tandem to facilitate access. By emphasizing that Universal Design was a form of “good design,” Mace strategically framed accessibility for all users (a radical, challenging, and far-reaching imperative) as a simple, common sense practice. This enabled him to draw upon disability rights, culture, and anti-institutionalization positions to challenge architects’ conceptions of disabled people as an insignificant and powerless population and their assumptions about accessibility as inherently tied to distasteful institutional or medical aesthetics (148–149).

Like disability activists who emphasized that rehabilitation should not be a prerequisite for access and citizenship, Mace (1985, 150) argued that accessibility should be available even to those who do not have a formal disability diagnosis. Code compliance approaches often required people seeking barrier-free access to convince others of the degree of their impairment through a process that critical disability theorist Ellen Samuels (2014, 9) terms “biocertification” – for example, use of a wheelchair or assistive device or official proof of a diagnosis. In 1989, Mace and his colleague, disabled design expert Ruth Hall Lusher, framed Universal Design as a concept benefiting marginalized users regardless of medical biocertification.

Instead of responding only to the minimum demands of laws which require a few special features for disabled people, it is possible to design most manufactured items and building elements to be usable by a broad range of human beings including children, elderly people, people with disabilities, and people of different sizes. This concept is called universal design. It is a concept that is now entirely possible and one that makes economic and social sense. (Lusher and Mace 1989, 755)

It is significant to note that Mace and Lusher proposed that Universal Design foreground disability, rather than arguing (as later proponents would) that Universal Design is distinct from disability access. While foregrounding disability, they also framed Universal Design as a resource for alliance between categories of users that were marginalized by mainstream standards of good design (albeit in different ways and to qualitatively different degrees). In doing so, they adopted a cultural understanding of disabled people as a disadvantaged minority group that exists in relation to other spatially excluded populations, such as children, elderly people, and people of different sizes.

This early framing of Universal Design reveals attention to the dimensions of power and privilege that determine belonging in built environments. As design experts with mobility disabilities, Mace and Lusher were among those for whom a legal right to barrier-free design (however limited) was most thoroughly mandated (in the form of ramps, elevators, and automatic doors). They used their relatively privileged positions as disabled designers who were included in accessibility codes to advocate for those who were not – for “collective access,” as activists and scholars would later call it (Hamraie 2013; Mingus 2010). Their attention to the collective stakes of access implied that disability advocates must seek inclusive design not only for themselves, but for other marginalized populations as well.

Mace and Lusher’s approach closely matched a cultural understanding of disability that conveyed the ethos of alliance and affiliation over biocertification and standardization. Their framing disclosed a critical disposition toward disability, which David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder (2003, 10) describe as “a political act of renaming that designates disability as a site of cultural resistance and a source of cultural agency previously suppressed.” Affiliating disability with other categories of social discrimination enabled Mace and Lusher to identify resonances between architecture and design approaches that challenged the normate template. Interaction designer Graham Pullin (2009, 93) would later refer to this sense of collective affiliation as “resonant design,” which begins by including the most marginalized and then explores the benefits of those inclusions for broader populations. Mace and Lusher’s framing also captured disabled people’s resourcefulness in fostering interdependence and relationality: an ethos that feminist disability theorist Alison Kafer (2013) calls the “political/relational” dimensions of disability. These capacious political, relational, and resonant dimensions characterized disability-focused Universal Design in the late 1980s.

0 notes

Text

Universal Design and disability: an interdisciplinary perspective

Universal Design and disability: an interdisciplinary perspective. (2014). In Disability and Rehabilitation (pp. 1344-1349). https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.931472

"The UN Convention on the Rights for Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) provides a comprehensive understanding of equal rights for people with disabilities [4]. The convention also emphasizes to raise awareness throughout society regarding respect for the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities. This international political and moral document constitutes an important contribution to future work towards inclusion and equal rights. The CRPD is part of the paradigm shift, and thus focuses on the need for more research on UD [4]. As a subject for research and teaching, UD encompasses different academic traditions, such as architecture, spatial planning, law, ethics, rehabilitation and public health."

"UD is not an abstract concept but a practical design strategy focusing on usability. According to CRPD, universally designed products, environments, programmes and services should be usable for different people [4]. The intended person universally designed objects aim at being usable for, includes individuals of different ages and with different physical, mental and cognitive impairments. In the CRPD, there is no demarcation towards any group of individuals. A rich understanding of human diversity therefore must guide interpretation and implementation of UD. Disability and UD is connected, insofar, as the aim of UD is to promote equal opportunities to participate in society for all citizens. Therefore, practicing UD strategies imply some concept of person and disability."

"From a UD perspective this is problematic because dismantling barriers must build on an understanding of the particular person who experiences the concrete barriers. A social model is then reductive both epistemologically and ontologically by focusing first and foremost on the barriers. Ontologically a social model overlooks the complexity in impairments as human condition. Epistemologically such a model does not value impairments and individual embodiment as objects of knowledge [13,15]. The role of the individual body and individual experience as situated places for knowledge production is thus under focused in the social model, which makes this model less qualified as a knowledge base for UD."

"What is the description of disability in CRPD article 1? The article states that “persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” [4]. When analyzing this quotation we find three elements. First there are different people with disabilities that include persons with long-term impairments, next there is the person–environment interaction, and third there are the barriers. We can refer to these factors as x, y and z, where x represents people with disabilities who have impairments, y represents the interaction involving people with impairments and the barriers they encounter and z represents the barriers that hinder participation. Disability, understood as a hindrance for participation, is in this interpretation described as a product of the interaction, thus as a product of the person–environment relation. In the preamble of the convention this is expressed even more precisely: “disability results from the interaction between persons with impairments and attitudinal and environmental barriers that hinders their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others” [4,e]. Thus, I will argue that the understanding of disability found in CRPD first and foremost is relational [4]. The relation comprises a person–environment interaction motivated by the person's right to activity, participation and citizenship. As a basis for UD, such a relational model is coherent, unfolding disability as a complex person–environment interplay."

"A relational model understands disability from the perspective of the interaction between the individual and the social, cultural and physical environment. UD is by nature a complex topic that involves a concept of person, the environment, the interaction"

0 notes

Text

Universal Design: From Policy to Assessment Research and Practise

Preiser, W. (2008). UNIVERSAL DESIGN: FROM POLICY TO ASSESSMENT RESEARCH AND PRACTICE. In International Journal of Architectural Research Archnet-IJAR - Volume 2 - Issue 2 (pp. 78-93). https://doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v2i2.234

"It can be said that the origins of universal design go back to the period after World War II when hundreds of thousands of veterans returned from the war and required rehabilitation and education in order to resume their normal lives. For those who were wounded in action, this resulted in the beginning of the movement, which led to the early establishment of rehabilitation centers at universities, for instance, at the University of Illinois. It was then when campuses of universities were first made accessible for wheelchair users and people with other disabilities. Eventually, these efforts resulted in a movement called Barrier-Free Design, and the development of accessibility guidelines on a state by-state basis. They, in turn, formed the foundation for what are now the ADAAG, i.e., the guidelines for the implementation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA, 1990)."

Again this book/article suggests that universal design or design for accessibility did not really become a focus until able-bodied people were injured and realised they needed to make changes to the way we designed. It doesn't sound like born disabled people were taken into consideration.

"From the outset of this article and discussion, it should be noted that universal design transcends the ADA in many significant ways, in that it goes beyond minimum dimensional and other requirements of the built environment, and is pertinent to the entire life space of populations. During its short gestation period, since about 1985, universal design has established itself as a potent factor in improving the quality of life for everybody, and on a global basis. In other words, universal design is not just for those who can afford it, or the industrialized countries, but it is also making inroads in developing countries, such as India (Balaram, 2001). Universal design has been called the “Design Paradigm of the 21st Century” (Ostroff, 2001; Preiser, 2006), which amounts to a laudable vision, but appears not to have been achieved by any means, and certainly not on a global basis. Some of the most advanced countries in regards to universal design are Japan, the United States and Canada, and certain countries in the European Union. In fact, Norway is considered to be most advanced in implementing universal design education and policies in community planning in that country (Christophersen, 2002; Vavik, 2008)."

0 notes

Text

The Evolution of Universal Design: A Win-Win Concept for All

Simmons, P. (2020, January 27). The evolution of universal design: A win-win concept for all. Rocky Mountain ADA. Retrieved October 2, 2022, from https://rockymountainada.org/news/blog/evolution-universal-design-win-win-concept-all

History of Universal Design

"Now, the concept of Universal Design is one that is often misunderstood and misapplied. Universal Design is a term coined by an architect, Ronald Mace who wanted to focus on accessible housing with a universal design. Mace championed accessible building codes and standards in the United States. Mace's term universal design exemplifies an all-inclusive philosophy of barrier free design.

Mace was born in New Jersey and contracted polio as a child. As a student at North Carolina State University School of Design, Mace encountered barriers in his wheelchair. Mace became an accessible built environment activist due to the inaccessible design of many facilities that he encountered. He was involved with the passage of North Carolina’s Chapter 11X, the first accessibility-focused building code in the United States. North Carolina’s Chapter 11X became the model for other States to follow. This also influenced Federal legislation prohibiting disability discrimination. The requirements came to be included in the Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990.

The concept of Universal Design is credited to Mace but it is Selwyn Goldsmith of the United Kingdom who contributed the idea of curb cuts. Goldsmith, after consulting with 284 other wheelchair users, conceived “dropped kerbs” in the early 1960s, better known as curb cuts today. The City of Norwich in the United Kingdom was the first city to install curb cuts at different intersections. Today, curb cuts are a common feature throughout the world.

Accessibility legislation such as the Architectural Barriers Act (1968); Section 504 of The Rehabilitation Act of 1973; the Fair Housing Act Amendments (1988); and the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990) established minimum requirements to protect people with disabilities from discrimination. Universal Design focused on making the environment more accessible above and beyond the minimum requirements that law may require. Designers must focus attention on improving function for a larger range of people. While ensuring accessibility, these laws fail to address equity and diversity of use.

In 1985, Ron Mace cautioned that Universal Design should be: “The design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design” (Maisel & Ranahan, 2017). Mainly from the need to reevaluate existing legal mandates to ensure usability by people with disabilities, the Principles of Universal Design were developed at the Center on Universal Design, North Carolina State University in 1997."

Accessible Design vs Universal Design

Modern Universal Design

"The ADA National Network further defines Universal Design as "inclusive design" and "design for all," as an approach to the design of products, places, policies and services that can meet the needs of as many people as possible throughout their lifetime, regardless of age, ability, or situation.

While we have the 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design, thanks to pioneers such as Selwyn Goldsmith and Ronald Mace, we need to remember that Universal Design was developed out of necessity. There have been developments that we are all taking for granted because of their universality such as:

Curb cuts or sidewalk ramps that was originally intended for people in wheelchairs but now used by all;

Automatic door openers are becoming the standard in all places;

Low-floor buses with ramps or that lower themselves when picking up passengers are becoming more common everywhere;

Cabinets with pull-out shelves, kitchen counters at several heights are becoming popular options everywhere;

Captioning feature, while originally intended for deaf people are now being used by more people who are not deaf themselves;

Design of handles and utensils are becoming more universal and easier to use; and

So many more things are now designed with the Seven Principles of Universal Design in mind.

So, let us put our minds together and strive towards a Barrier Free World that is built around Universal Design where everything is easily accessible for EVERYONE so that we will have a world where accessibility is the norm and not a requirement!"

Thought this image was quite a good way to showcase how universally designed things work vs buildings with alterations (buildings that haven't been originally designed for everyone in mind).

0 notes

Text

What We’re Leaving Out of the Discussion Around Inclusive Design

As a disabled person, I found this article incredibly relatable in terms of being excluded through design. I think it gives a good idea of how the world is less accessible than people think.

Holmes, K. (2018, April 6). What We’re Leaving Out of the Discussion Around Inclusive Design. AIGA Eye on Design. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/what-were-leaving-out-of-the-discussion-around-inclusive-design/

"But what does inclusion actually mean—especially when it’s so feverishly applied to broad areas of society? The word is as axiomatic as it is unspecific. I’ve wrestled with this ambiguity as director of inclusive design at Microsoft, in my own independent design practice, and while writing a book about inclusion. Inclusion is a vast promise—as immense, in fact, as human diversity—and that’s what makes it a great design challenge. But without a clear agreement on what inclusion is, can we ever hope to achieve it? How can we design for something that means so many different things to different people?

Perhaps we can’t, at least not effectively. What I have seen make a difference is a slight shift in the way we think and talk about inclusive design. To do this, we need to address that less popular term, the one that tends to get left out of the discussion: exclusion.

Exclusion is not a PR-friendly word, but it is a universal human experience. We all know how it feels when we’re left out. We each experience it over the course of our lives. Exclusion is concrete and specific, and can often be traced back to an identifiable source. This makes it a meaningful starting point for inclusive design. Our ambitions for inclusion are best achieved by first recognizing and then remedying exclusion wherever we encounter it.

Design is much more likely to be the source of exclusion than inclusion. When we design for other people, our own biases and preferences often lead the way. When we create a solution that we, ourselves, can see, touch, understand, or hear, it tends to work well for people with similar circumstances or preferences to us. It also ends up excluding many more people.

This is especially true with respect to disability. The World Health Organization defines disability as a mismatched interaction between the features of a person’s body and the features of the environment in which they live. This is also known as the social definition, or model, of disability.

Every choice we make as designers determines who can use an environment or product. The mismatches that we create in the process are the building blocks of exclusion. From the stairs at the entrance of a building to the two-handed design of a video game controller, our solutions clearly signal who does and doesn’t belong."

This article is extremely relatable for people with disabilities. I have experienced this type of exclusion with a lot of products, including video game controllers. I can't play video games at all really because they require someone to reach buttons on two sides of a controller at the same time, something that is almost impossible with only one hand. It gives a very clear message to me that I am not welcome in participating in that type of activity.

"Exclusion is a deeply personal subject for many people, and often a painful one. Social cognitive neuroscience studies, like those led by Dr. Naomi Eisenberger and Dr. Matthew Lieberman, are helping to shed light on the effects of social exclusion, ostracization, and rejection. There’s evidence that feeling socially rejected activates some of the same areas of the brain that are activated when a person feels physical pain. In short, exclusion can hurt. Not just metaphorically, but physiologically.

What happens when a designed object excludes us? While we expect people to be unfair, we imagine buildings to be unbiased blocks of wood, metal, and concrete. We expect software to be impartial lines of code. This is why an unusable design feels like a rejection, especially if it gates our access to important social moments.

In these moments, many people are more likely to blame themselves than the object. They might feel left behind and wonder why technology changes so much faster than they do. Moreover, it’s often unclear who’s responsible for fixing that exclusion."

It is really tough feeling excluded because of something I have no control over. Especially growing up this way, I got a lot of clear indicators when I was younger that I didn't quite belong or wasn't 'allowed' to use certain products. It sends a very strong message when products are not inclusive.

"Second, we can focus on mismatches as a way to identify better design constraints. Specific types of mismatches can help us go deep into how to create better solutions. Design thrives with good constraints and is exclusive by nature. The key is to regularly ask yourself who will want to use your design, but will be most unable to do so? And then seek out their input as a way to help you shape better design constraints.

And finally, through design, we can be intentional about why we choose to exclude people and take responsibility for making it better over time through planful investments. Exclusion can become a purposeful choice, rather than an accidental harm.