Documenting my work on digitizing cuneiform, and all the random tangents it takes me on!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Video

#Enthusiast here asking: have the determined shape of tool now? #I recall years ago there being debate on if it was a square or triangle shape.

The most recent in-depth analysis I know of is Cammarosano's 2014 "The Cuneiform Stylus", which is freely available here. The short answer is, it's hard to be sure, because reed styli just don't survive very well archaeologically. But we have some bone and metal styli that did survive (these were popular in Anatolia, where reeds aren't as plentiful), and those have rectangular or trapezoidal ends.

Wedges written with a reed stylus often show a curved impression on one side (what Cammarosano calls "the reed pattern"), which suggests part of the outer surface of the reed was involved, but this could be compatible with either a triangular or a rectangular end. Either way, you'd get an approximately 90-degree angle, with one side curved.

The internal dimensions of the wedges can also be measured to figure out what sort of angle they were written with. Apparently out of these six designs, tip "C" most closely matched actual ancient wedges. (But since only one corner left an impression, this also doesn't tell us if it was a triangle or rectangle.)

So in theory, you could file down the end of a chopstick (or cut a reed stylus with a knife) to get this angle for more authenticity. But chopsticks are just so readily available that I default to them without modification.

i never realized cuneiform was made with the corner of a cuboid tool, i thought the wedge shapes were carved such that you would press straight down with the tool at a 90° angle to the clay

199K notes

·

View notes

Text

YMCA in Akkadian (Ancient Babylonian), as written by Gilgamesh's exasperated tourism minister trying to attract more gay guys to Uruk to keep Gil distracted from politics:

.

Eṭlū!- Young men!

Lā tuštamarraṣā- Do not, do not be troubled!

Aqabbi, eṭlū!- I said, young men!

Lā lā taṣallalā- Do not, do not lie down!

Aqabbi, eṭlū!- I said young men!

Šunu ina ālim- You are in a town,

Bēt bēt šikārim ḫanbā- Where taverns sprout luxuriously,

Eṭlū!- Young men!

Ina ālim alkā- Go to the city,

Aqabbi, eṭlū!- I said young men!

Bēt kaspī ul tīšâ- When you do not have money,

Annikīam tuššabā- Here you can dwell,

Bēt napṭirim nīšu- We have guest-houses,

Itti awīlī umtallâ- They are filled with men….

.

Taḫaddâ ina - You’ll have fun in

𒌋𒊏𒌋𒅗 U-RA-U-KA! - U-R-U-K!

Wašābum ṭāb ina - The living is good in,

𒌋𒊏𒌋𒅗 U-RA-U-KA!- U-R-U-K!

Ziquratum elâ! Purattum amrā!- Climb up the ziggurat! See the euphrates!

Šikārum ṭābum šitâ!- Drink fine beer!

Taḫaddâ ina - You’ll have fun in

𒌋𒊏𒌋𒅗 U-RA-U-KA! - U-R-U-K!

Wašābum ṭāb ina - The living is good in,

𒌋𒊏𒌋𒅗 U-RA-U-KA!- U-R-U-K!

Amuḫḫūni šaqû! Ziqnūni ītebbū! - Our walls are high! Our beards are shiny!

Nuppušātunu!- You are allowed to breathe [relax]

.

Eṭlū!- Young men!

Eṭlū šimeanni!- Young men listen to me!

Aqabbi, eṭlū! Agana šimeanni!- Young men! Come on, listen!

Aiālam terrišāšu- You desire assistance,

Shū ali īde- This I know for certain!

Šārqum wērum ul ninaddinkunūti- We will not sell you poor copper,

Eṭlū! Ālum ša Uruk bani- Young men! The city of Uruk is beautiful!

Aqabbi eṭlū! Bālātka tezzibši!- I said young man! Leave your pride behind!

Nušallakkunūti- We cause you to go,

Ina Uruk alkā!- Go to Uruk!

Ūmum anniam iseddūkunūti- Today they will help you…

.

Taḫaddâ ina - You’ll have fun in

𒌋𒊏𒌋𒅗 U-RA-U-KA! - U-R-U-K!

Wašābum ṭāb ina - The living is good in,

𒌋𒊏𒌋𒅗 U-RA-U-KA!- U-R-U-K!

Šarrum šitpiṣā! Ittmalûšu ṣālā! - Wrestle the king! Fight with him!

Ittīšu mekkê mēlilā!- Play ball with him!

Taḫaddâ ina - You’ll have fun in

𒌋𒊏𒌋𒅗 U-RA-U-KA! - U-R-U-K!

Wašābum ṭāb ina - The living is good in,

𒌋𒊏𒌋𒅗 U-RA-U-KA!- U-R-U-K!

Ziquratum elâ! Purattum amrā!- Climb up the ziggurat! See the euphrates!

Šikārum ṭābum šitâ!- Drink fine beer!

.

Eṭlū! Bilītkunu īde! - Young men! I know your burdens

Amtaraṣ! Ina šinigī- I was unwell, in my village,

Ātanaḫ! Erēšum ezzēr- I was tired, I hated plowing,

Awīlum ana yâšim iṭeḫḫe- A man to me approached,

Inūšu! Awātum awânim- Then! Words were said to me,

Šumašu, Sîn-lēqi-unninni- His name was Sîn-lēqi-unninni!

Ina Uruk alkā! Iqabbi ana yâšim- Go to Uruk! He told me,

Ina Uruk awīlī ūterrešū- In Uruk men are needed…

.

Taḫaddâ ina - You’ll have fun in

𒌋𒊏𒌋𒅗 U-RA-U-KA! - U-R-U-K!

Wašābum ṭāb ina - The living is good in,

𒌋𒊏𒌋𒅗 U-RA-U-KA!- U-R-U-K!

Ziquratum elâ! Purattum amrā!- Climb up the ziggurat! See the euphrates!

Šikārum ṭābum šitâ!- Drink fine beer!

.

Eṭlū!- Young men!

Addāniqa tallkānim- Please come

Aqabbi, eṭlū!- I said, young men!

Inam anniam ezêršu- I hate this job…

Aqabbi, eṭlū!- I said, young men!

Anāku ānḫāku - I’m so tired….

Bēt bēt šikārim ḫanbā- Where taverns sprout luxuriously,

Taḫaddâ ina - You’ll have fun in

𒌋𒊏𒌋𒅗 U-RA-U-KA! - U-R-U-K!

(Šarrum lillam ina - The king is an idiot in

𒌋𒊏𒌋𒅗 U-RA-U-KA!- U-R-U-K…)

Ao3 link

7K notes

·

View notes

Video

Chopsticks are unironically a really good way to practice cuneiform! They're generally much longer than an ancient stylus would be, but the rectangular end is a perfect shape.

Notably, there's some debate in the Assyriological community about whether the horizontal and vertical wedges were written with different edges of the stylus (as shown here) or with the same edge (by rotating it 90 degrees). I've always found it easier to use different edges, but Michele Cammarosano argues (based on the patterns visible on the surface of the clay) that they were universally made with the same edge in Mesopotamia, and probably also in Anatolia.

i never realized cuneiform was made with the corner of a cuboid tool, i thought the wedge shapes were carved such that you would press straight down with the tool at a 90° angle to the clay

199K notes

·

View notes

Note

And then you have the Hittites, who used the base-60 symbols, but crowbarred them into a base-10 system—they came up with a different way of writing 60 that didn't look like a 1, and new symbols for 100, 1k, 10k, and 100k, so they wouldn't have to use 60 or 3600 as units.

We have no idea how they actually pronounced any of these, but they were willing to go to great extents to avoid the base 60 elements, so what they wrote probably corresponded pretty well to how they said them out loud.

i feel like i didn't phrase my question quite right the first time, so to be more specific: did average people use base 60 in everyday life, or was it something only used by scribes for accounting?

Oh, I understand! (Original reply here.) Yes, people in Mesopotamia used base 6x10 in regular life, there was no "other" system recorded anywhere. Use of base 10, in particular, is nowhere near as universal as modern standardized systems spread by European colonial powers would make it seem.

That said, schooling (for non-scribes) wasn't regularized, so it's unlikely most people would (or would have need to) count to numbers beyond a certain threshold. My guess is most people would know up to shar = 3,600 since it's so round, though that's just a gut feeling.

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Though also remember, numbers less than 60 were made up of tens and ones. The base-60 number system was for very big (>60) or very small (<1) numbers, and at least in Akkadian, both the signs and the words for the numbers in between were base-10: išten "one" + ešeret "ten" = išteššeret "eleven", šina "two" + ešeret "ten" = šinšeret "twelve", etc.

You'd write (though not say!) "100" as "1×60+30", but most people would never need to work with hundreds of things. It's sort of like how you generally wouldn't say "100 teaspoons of water" in a recipe, you'd say "two cups". Similarly, an ancient Mesopotamian would generally switch units when talking about so many things, in order to keep the numbers reasonable.

Just like today, it's the accountants and mathematicians who needed the fancy big numbers!

i feel like i didn't phrase my question quite right the first time, so to be more specific: did average people use base 60 in everyday life, or was it something only used by scribes for accounting?

Oh, I understand! (Original reply here.) Yes, people in Mesopotamia used base 6x10 in regular life, there was no "other" system recorded anywhere. Use of base 10, in particular, is nowhere near as universal as modern standardized systems spread by European colonial powers would make it seem.

That said, schooling (for non-scribes) wasn't regularized, so it's unlikely most people would (or would have need to) count to numbers beyond a certain threshold. My guess is most people would know up to shar = 3,600 since it's so round, though that's just a gut feeling.

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hittite might have what you need here!

The Hittites, like a lot of Ancient Near Eastern cultures, did a lot with cult statues: specially-prepared statues that their gods would literally be summoned into, to be fed and bathed and entertained. Usually this was an actual statue, but sometimes it could be more abstract art, like a sun-disc for the sun god.

And sometimes, instead of a statue, it was a specially-carved monolith called a huwasi. From the start of the New Kingdom onwards they used two Sumerian words to write this term: ZI.KIN, literally "soul object" (sometimes with a determinative NA₄ "stone"). This was also a play on the Akkadian root for "to inhabit", S-K-N, since the god inhabits the monolith.

I don't believe this term was ever used in actual Sumerian, but if you want a term for a soul bound into a physical object, Hittite has you covered—with a bilingual pun, no less!

I’m looking for words to assemble into something that means “Built on memories/soul” or “created with memory/soul as a foundation”. Working on a story where a soul is trapped in stone and the stone is hidden, and an alternate universe begins to sort of crystallize around that stone and form itself based on the memories of the trapped soul.

Hi there! There isn't a great exact term for "memory", see this post for more, though here I might use mengar "remembrance", which seems close enough. I most often translate "soul" as zi "breath".

There also isn't a great translation of "built" without a full sentence - ankimengara dim "I built the universe (anki) from remembrance". The easiest would be to use "of remembrance" -mengara (or "of soul" -zi) as a genitive attached to a noun, the thing that's made of it - like how I used ankimengara "universe of remembrance". Using temen "foundation", we could make temenmengarada "with a foundation (made) of remembrance" or temenzida "with a foundation (made) of soul(s)", though again these are sort of "floating phrases" without context.

I hope one of these works for you! Let me know if there's a longer "frame sentence" that might help me nail down the phrase.

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

In Coptic we see ϩⲉⲓϯ (Fayyumic), ϩⲟⲉⲓⲧⲉ (Sahidic), ϩⲁⲓⲧⲉ (Lycopolitan), ϩⲱⲓϯ (Bohairic), so we can make a guess at the Middle Egyptian vocalization—I'm not great at this step, but something like ḥāiṯət perhaps? So very approximately "HIGH-chet" (/ħa:j.tʃʰət/).

But this sort of uncertainty is why most Egyptologists don't bother with reconstructed vowels and just use transliterations of the consonants.

Random question: what is the Ancient Egyptian word for hyena and how do you pronounce it/spell it out in English?

There isn't one, really. There are words we think *might* be hyena, but since the Egyptians would have only very rarely encountered them. All we have is:

HT.t

As always, there isn't a pronunciation in English. You can verbalise the transliteration in a number of ways by adding vowels back in. This would be something akin to Hetchet or Hatchet or Hutchet, or Hutchat, Hetchut, Hetchat etc etc

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Slides from the Hittite Instructions to Temple Officials, late 1300s BCE

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

This is beyond my expertise in Egyptian, but many Afro-Asiatic languages have this same distinction between direct and indirect genitives, and generally, the difference is a lot like "can" vs "is able to" in English.

Fundamentally, "she can do it" and "she is able to do it" mean the same thing. "Is able to" is a few syllables longer, so we tend to default to the shorter one; but, if someone decided to use the longer one for some reason, nobody would really bat an eye. They're both perfectly valid ways to say some action is possible.

But, the shorter one also has some restrictions on how it can be used. We can't say *"she will can do it" to mean "she isn't capable of it now but will be capable in the future". We can say "she will be able to do it" to get that meaning.

Well, same with the direct and indirect genitives! The direct genitive is shorter and often more convenient—in Egyptian, there's not a huge difference in writing, but we know direct genitives glommed together into a single big word while indirect genitives kept the stress on each word individually—but it has limitations on how it can be used.

In Akkadian at least (not sure about Egyptian), you can't have multiple nouns with the same possessor in the direct genitive construction, so for something like "the lord's house and lands" or "the king's gold and silver", you need an indirect genitive. And there are limits on where adjectives can go in a direct genitive construction; an indirect genitive has no limits there, and you can put the adjectives exactly where you want them for the right shade of meaning.

So, they mean the same thing; one of them is shorter, but has some limits on how it can be used syntactically, the other is longer but doesn't have those limits, so there are reasons to use them both.

Hope this helps!

( @aphemorpha )

sorry, i'm confused and have no one else to clarify my egyptian questions. is there a semantic difference in meaning between the direct genitive and indirect genitive? i know they're often translated the same, but?

*looks at the clock* 11:19pm on a Saturday night. Yeah sure, lets do grammar right now.

There is no semantic difference in meaning between the direct and indirect genitive in Middle Egyptian. They're translated the same because they are both representative of two nouns where one takes possession of the other.

The difference occurs in the way they're written. For the direct genitive, it is two nouns together, not separated by an intervening word. This usually occurs in set phrases, titles and the like (often with honorific transposition), so: nb imAx mr pr 'possessor of imAx-status' or sA-nsw 'prince' (lit. son of the king). If one of the nouns is to be described with an adjective, then that adjective will come after both nouns.

For the indirect genitive the two nouns are split by the genitive 'n(y)'** or 'of' (or variants depending on gender or number of people speaking) which is literally referred to as the indirect gentive when used this way. So nsw n kmt 'King of Egypt' or wrw nw AbDw 'great ones of Abydos' are good examples of the indirect genitive in action. The indirect genitive can also be split using an adjective, so: inw nb nfr n sxt 'all good products of the countryside'.

** n(y) is almost never written out with the 'y' because it isn't in the Egyptian, but it's important to note that while visually it isn't distinct from the preposition 'n', it is gramatically distinct and should be treated as such.

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

This is part of the problem with not writing the vowels! Presumably the vowels would have made it easy to distinguish mr "hoe", mr "milk jug", mr "pyramid", and mr "love, care for", as well as mrrt "street", in actual pronunciation. But in hieroglyphs, those vowels simply weren't written; instead, determinatives were used to deal with the ambiguity. Fortunately, a hoe, a milk jug, a pyramid, and a street are all pretty easy to draw!

I actually use this particular example as an exercise in class:

What would King David be called in ancient Egyptian (in Hieroglyphics) ?

Not sure I can help you there. I would have to know his name written in Aramaic and then I would have to try to backwards configure that to what would ostensibly be Late Egyptian or even Demotic. That's no easy task when a) I don't speak Aramaic and b) I don't believe we have an example of correspondence between speakers of Aramaic and Egyptian where I could make any reasonable guesses.

It's not straightforward either. In the New Kingdom, Amenhotep III and Tushratta, king of the Mittani, wrote letters to one another in both Cuneiform and Egyptian. Tushratta refers to Amenhotep as 'Nibmuaria, King of Egypt, my brother' (as a reference to his Prenomen name 'Nebmaatre') and Amenhotep IV (or Akhenaten) as 'Napkhuria' (his prenomen being Neferkheperre).

It would be incredibly difficult for me to do something like this for King David, particularly given that I don't speak one of the languages required.

140 notes

·

View notes

Note

hiya ♡ I'm still a laic in cuneiform, but i make pottery cups as a hobby and wanted to ask if maybe you have any recommendations of texts that i could write on a cup? I know that your blog is mainly for digitalising cuneiform but maybe you have something in mind? Or could suggest some easy resource that i could explore?

I was trying to find readable excerpts from the epic of gilgamesh but in the end i couldn't find any that would fit.

I'm looking for something pretty, like a short poem, or a verse. Or something funny, like an excerpt from that famous complaint about grain or sth.

Yea, but i don't know much about the topic so it would need to, apart from having said meaning, be intelligible and complete. Bc the begining and ending of most of the tablets that i looked was damaged :cc And i wouldn't know what should go where.

Oh, that sounds awesome! Would you be painting it on, or inscribing it with a stylus?

My specialty is specifically Hittite cuneiform, but if you're interested in Sumerian or Akkadian, I can recommend some other blogs to ask as well. (In particular, @sumerianlanguage is a great source for Sumerian things.) Fortunately, the Epic of Gilgamesh appears in all three languages!

Unfortunately, damaged tablets are the rule rather than the exception after so many thousands of years, so most complete texts are pieced together from multiple copies. If you look at my introduction to cuneiform, there are a couple texts there (the Complaint Tablet to Ea-Nāṣir and the Hittite Myth of Illuyanka), which show about how long one line of cuneiform generally is (both in number of signs and amount of meaning); based on that, how long of a text are you looking for?

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hello! I was wondering if you had any tips for using cuneiform as an art inspiration? One of my friends is super into cuneiform and birds, so I wanted to kind of write the cuneiform for "corvid" using stylised triangular crows.

Feel free to ignore this, it's a pretty involved ask!

I had a look at the Assyrian Languages website, and it spat out

but there's so many options! Why is the translation given as "erebu" without the cuneiform, then followed by the other words "uga" and "buru", which do have cuneiform?

And are there rules for rearranging the different units of the word? Is it like English, where you can't really split the letters of a word up, because it won't make sense?

I also double-checked the translation with the the Concise Dictionary of Akkadian, which you linked a couple posts ago, and they match, but there isn't any cuneiform in the dictionary.

Thank you for reading this far!

Okay, buckle up for a ride!

Akkadian is a Semitic language with a weird, cobbled-together writing system. It's a bit like a rebus: we can figure out that "👁️ ❤️ 🐑" means "I love you," because "eye" sounds like "I," hearts connote love, and a female sheep is a ewe, which sounds like "you." Likewise, a given cuneiform sign can be one of three things: a syllabogram (representing the sound of particular syllables, like 👁️), a logogram (representing a particular idea, like ❤️); or a determinative (representing a category of ideas, like "Dr."). In many cases, a given sign could be any one of those, depending on context. As a result, there are many possible ways to spell most words—although certain sign combinations tend to get standardized in a particular place and time.

In this case, "UGA" is the logogram for a corvid, and "MUŠEN" is the determinative for a bird. So one way to write "a crow" (literally "a crow-bird") would be to combine the signs for UGA and MUŠEN. (MUL is the determinative for an astral body, so if you were trying to say "the crow-planet," you could write it as "star-crow-bird," or "MUL.UGA.MUŠEN."). And yes, the order does matter in most cases; I wouldn't rearrange them.

But! Instead of writing something logographically, you could "spell it out" using syllabograms. So the word erēbu/arēbu, which is what "crow" would have sounded like, can be broken down into syllables and spelled that way, e.g. a-re/ri-bu. When the Epic of Gilgamesh describes sending out a raven as part of the Flood story, it spells it as "a-ri-bu." (Well, technically a-ri-ba/a-ri-bi, because those are the declined forms.)

The simplest two options that appear in the corpus, then, are UGA or BURU4 ("crow" without the "bird" determinative, which is optional) or a-ri-bu. Here's what those look like, using two different potential writing styles: Old Babylonian (an earlier and more complex writing system) and Neo-Assyrian (a more rectilinear, streamlined, later writing system):

As you can see, UGA is a very complicated sign, so I would recommend choosing either BURU4 or a-ri-bu. I find Neo-Assyrian much easier to reproduce, but the choice of writing system is up to you.

I hope this helps. Send me a picture of what you produce; it sounds so fun!

108 notes

·

View notes

Note

Akkadian names tended to be complete sentences, so I think using the complete sentence "his wings stir up sandstorms" could work; it's not good Sumerian, but the majority of surviving Sumerian was written by native Akkadian-speakers, and I could definitely see one of them translating a name too literally.

Hello again!

Your blog again has been so helpful in writing for DND!

May I ask, how colors work in Sumerian?

I'm guessing that they come after the word they modify.

So I wanted to say...

"Black Dragon" would it be something like "Ushum-Gig"?

And so on for these colors?

White Dragons Ushum-Babbar Red Dragons Ushum-Sa Green Dragons Ushum-Sig Blue Dragons Ushum-Nisig

Finally, may I also ask, if I wanted to poetically name one of them "He whose wings rouses/stirs up sandstorms" how might that be expressed in Sumerian?

Thank you SO much!!!

Hello, and thanks for the kind words!

Yes, colors, like other adjectives, follow and attach to the noun they modify. Here's my post on color vocabulary - it looks like you've got all the "[color] dragon" terms correct! My one note is that the color space that in English we call "green" is split between sig and nisig in Sumerian, so I'd translate Ushum-sig as "yellow dragon(s)" or maybe "bright green dragon(s)", since a darker/cooler-toned green dragon would also be Ushum-nisig.

As for the "He whose..." translation, that specific construction is very hard to convey in Sumerian - the pronoun ane "she/he/etc" doesn't work well with modifiers like subordinate clauses, and I don't know of any names constructed this way. As a full sentence, I'd say Ani ulu iblulu "His wings stir up sandstorms", from a "wing", ulu "sandstorm, south wind" and the present-tense form of lu "to stir up, mix". (I've opted for a instead of pa, both of which mean "wing", because pa generally implies a bird's wing, covered in feathers.) You could make this into a noun phrase like Ani ulu iblulua "... that his wings stir up sandstorms", but I don't think it'd convey well as a name. Maybe something simpler like Aulu "Sandstorm-wings"? Or if you have any other translation requests or ideas, feel free to let me know!

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Introduction to Cuneiform

Have you ever wanted to learn the world's oldest writing system, Mesopotamian cuneiform from five thousand years ago, but not known where to start?

I find cuneiform absolutely fascinating (as you can probably tell by this blog), but it's also incredibly difficult to get started with. Modern textbooks on Sumerian, Akkadian, Hittite, and so on tend to de-emphasize the actual cuneiform as much as they can for fear of scaring students away, and in my opinion that's a shame, because it's one of the most interesting parts!

Even modern researchers generally don't use cuneiform in publications unless they absolutely have to, relying on transliterations instead. One of the goals of my research is to change that, by creating new ways to typeset cuneiform and embed the actual signs in a document.

So I've put together my own introduction to the subject, showing off a few of those new technologies for people to work with. It's presented as a series of twelve lessons, starting with the absolute basics (why is it made of wedges in the first place?) and ending with a complete Hittite mythological text to read and transcribe.

Plus, as a bonus, it shows you how to write out the first part of the Complaint Tablet to Ea-Nāṣir. It's Akkadian, not Hittite, but I couldn't resist.

Check it out, and please do let me know what you think! I've been working on these technologies for a while and this is their first time really getting tested in the field.

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thank you very much! That answers my question perfectly. My Akkadian skills are still not great, and I would never have realized it was a trebly weak verb.

I'm working on a basic introduction to the cuneiform writing system, focusing on Hittite since that's my specialty, but given how famous Ea-Nāṣir is now I wanted to include a bit of the tablet as an exercise. Which means brushing off my rusty Akkadian again!

Heya! I'm looking at the famous Complaint Tablet to Ea-Nāṣir and I'm having difficulty with one part of the Akkadian. Specifically, lines 16 through 18: ya-ti a-na ki-ma ma-an-ni-im / tu-ši-im-ma ni-[x-x-x]-ma / ki-a-am te-me-ša-an-ni. I get that the first line is "me, like what sort of person" and the last line is "you treat me so badly", but I'm lost on the one in between. Is this a verb like "wašāmum" or something? And what might the damaged word be? Tyvm!

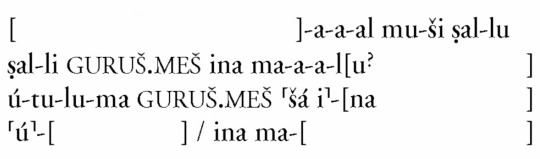

In my translation, I translated those lines loosely as "Are you really going to treat me this way, insulting me like that?" Here is the hand drawing of them:

Word-by-word, this is how I'd translate it:

iāti ana kīma mannim: "me, like what kind of thing..." tu-ši-im-ma-ni-[i]-ma: "... are you treating me?" kī'am tumêšanni: "how you despise me!"

CAD parses the middle line as a single verb, a shin-stem durative of the trebly weak verb ewû, plus a first-person suffix and the -ma coordinating conjunction, and I agree.

The tricky part is that the first half of that line is inscribed quite densely, so there's definitely space for more than an "i" in the missing area in the center, which is why your transcription has space for three signs there. But on the other hand, the "ma" has lots of space around it, so it's possible that the scribe began writing densely, then realized that they had lots of space, so they spaced out the "i-ma" signs at the end of the line. Since the text makes sense with the single sign, I'm inclined to stick with the CAD (and Leemans, whose transliteration agrees).

Let me know if you have follow-up questions!

82 notes

·

View notes

Note

"Ishtar" is a bit weird in Akkadian, because it can either be a name or just the normal word for "goddess". The genitive "of the goddess" would be ištari(m), but the name is usually written with a logogram, and I don't think I've ever seen it inflected.

So instead I'd use an indirect genitive, lābum ša Ištar, probably written something like la-a-bu-um ša INANNA. Literally ša means "the one belonging to", and it's not the most common way to express possession, but you can use it with logograms which made it popular with divine names.

Or, just use the construct state, and leave the inflection as an exercise for the reader: la-ab INANNA.

Hello, I love your blog. Sorry about the previous ask, I hadn't yet seen one of your "no tattoo questions" posts!

Would you be so kind as to translate "Lion of Inanna" and/or "Lion of Ishtar"?

My impression is that the former would be rendered in Sumerian something like "Urgula Inanna.ak" 𒌨𒄖𒆷𒀭𒈹𒀝 but I have little confidence in this translation. I have no idea about "Lion of Ishtar" in Akkadian other than thinking "lābim" would be the genitive form for "Lion"

Hello, and thanks for the kind words!

Urgula 𒌨𒄖𒆷 is a word for lion, but the more common term is urmah 𒌨𒈤; both literally mean "great dog". You've got the basic structure but because the genitive ending -(a)(k) generally disappears after a vowel (see the various recent posts on this case), the form would just be urmah-Inanna 𒌨𒈤𒀭𒈹 or urgula-Inanna 𒌨𒄖𒆷𒀭𒈹, though with a full sentence of context it might appear differently - feel free to send one along if you have one.

As for Akkadian, my grammar isn't strong enough to be able to give you a translation or cuneiform. But I can tell you that in this phrase, the genitive case would be applied to Ishtar (genitive corresponds to the object of the "of" preposition in English), and so lion would probably appear as its base form lābu (again, depending on the context within a sentence). I hope that's helpful!

51 notes

·

View notes

Note

Some authors treat A.A as a compound sign with the reading aya (or aja if you prefer), and I think that makes the transliteration a lot cleaner: ma-aya-lu. Giving names to compound signs like this is most common for logograms (ENSI "governor" in a transliteration actually means the three signs PA.TE.SI), but occasionally happens for phonetic signs too!

It is a bit odd for a phonetic sign to represent multiple syllables, but not unheard of. Hittite scribes, for example, wrote the word a-na ("to" in Akkadian) so often that they started to combine the a and the na together, turning them into a single sign with the reading aná:

Hello, I wonder do you still accept asks? Because me and my friends kinda self-taught myself on Akkadian recently and there's passage that kinda... sparked debates among my peers. I can't find the cuneiform but the Akkadian sounds like this :

ü-tu-lu-ma etlütu (gurus) [sa i] - [na ma] -a-a-al mu-si sal-lu

Professional Assyriologist (Andrew George) translated that passage as :

The men were lying down, that were asleep on beds for the night

From the Akkadian dictionary we can identify some words

Utulu : [itulu] lay down

Etlutu (gurus) : Young men

Mu-si : at night

Sal-lu : sleep

Other words are too fragmentary for the admittedly amateur me to decipher, but I can't find any usual word for bed in that passage either "bitu" (bedroom), "erim", "gisnu", "huralbu", "i'lum", "marsu", or any other possible words for bed that you can find on the dictionary, let alone the proof that the word is plural. The closest I can find is, perhaps, that [na ma] there is a fragmentary word for "namallu" which in dictionary means "plank bed", double-sided bed. And also I can't find plural form on that line, so perhaps you can help me? Not necessary about the bed/beds, but more about how will you translate that line?

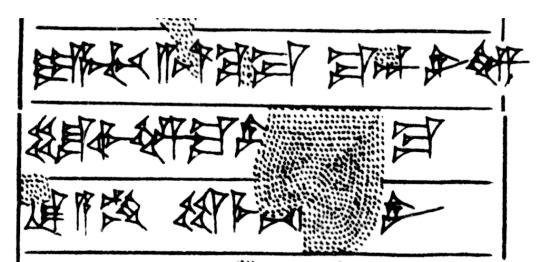

Hi! The fragment you mention is from the SB Epic of Gilgamesh, VI.180. Here is the score for that line (a comparison of various manuscripts):

Although the second line is a little different, we can use it in combination with the other versions to reassemble the likely original line: "ú-tu-lu-ma GURUŠ.MEŠ šá i-na ma-a-a-l mu-ši ṣal-lu." Whenever you see a double "-a-", as in "ma-a-a-l," it's generally transliterating a y/j sound, so it's listed in the dictionary as either "majālu" or "mayālu" (depending on how German your dictionary is!). "Majālu" is a relatively common Akkadian word for a bed or sleeping place. It's rendered in version 1 as "majāl" (no case ending) because "ina" will often occur with the bound (i.e. stripped-down) form of. noun.

So the word-for-word literal translation is "and-they-lay-down, the-young-men, in bed, at-night, sleeping."

Hope that helps, but let me know if you have further questions!

33 notes

·

View notes