#ATU Index

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I think it would be fun to challenge people to write stories promoted only by categories in the aarne-thompson-uther index. With the optional additional challenge that the genre/style is NOT folk tale or fable.

Categories such as “war between birds (insects) and quadrupeds” and “which bird is father?” and “innocent slandered maiden” and “suitors at the spinning wheel” and “seemingly dead relatives” and, possibly my favorite, “cases solved in a manner worthy of Solomon”

I’m finding a lot from this table of tale types: https://libraryguides.missouri.edu/c.php?g=1083510

#my post#fairy tales#folk tales#fables#atu index#aarne-thompson-uther index#classifications#writing#prompt

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I'm reading Echo North by Joanna Ruth Meyer, and I absolutely adore how it's a mix of all these tales I spent five months studying for my thesis. It's the entire ATU 425 tale type category at once*. A bit of Beauty and the Beast, a bit of Cupid and Psyche, a bit of East of the Sun and West of the Moon... When you know what you're looking at, it's so interesting to analyse it all.

*ATU= Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index, a classification of as many of the folktales and fairytales indexed around the world and the centuries, catalogued after their structures (their type). ATU 425: "The Search for the Lost Husband". ATU 425A: "Animal as Bridegroom" -> East of the Sun and West of the Moon (and The Serpent Prince, the Pig King...). ATU 425B: "Son of the Witch" -> Cupid and Psyche (also The Son of the Ogress, Tale of Baba Yaga...). ATU 425C: "Beauty and the Beast". There are a few more types (it goes to 425E), but these three are the main ones.

#echo north#joanna ruth meyer#books#fairy tales rewritten#fairytales rewritings#folklore#folklore studies#fairy tales#tale types#atu index#alright professional deformation i guess but this is just fascinating and i want to keep working on contemporary rewritings of fairy tales#rapha talks#rapha reads

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

If you want to have a look at the ATU (Aarne Thompson Uther) Index of Folk Tales:

The Multilingual Folk Tales Database (which includes the ATU Index) is saved on the Internet Archive

The Kalevala Society Foundation has PDF copies of the 2nd printing in 2011: Part I, Part II, and Part III

GUYS THIS IS AMAZING

SERIOUSLY

6000 YEARS

STORIES THAT ARE OLDER THAN CIVILIZATIONS

STORIES THAT WERE TOLD BY PEOPLE SPEAKING LANGUAGES WE NO LONGER KNOW

STORIES TOLD BY PEOPLE LOST TO THE VOID OF TIME

STORIES

#fairy tales#folklore#legends#Aarne Thompson Uther Index#ATU Index#Proto Indo European culture#minor quibble here if the stories existed they're not OLDER THAN CIVILZATIONS they're just older than writing#writing is pretty new only 5000-6000 yo#oral traditions#written traditions#the jump from one to the other and back again is a constant source of fascination for me#anyway brb gonna be here for the next few weeks in this particular rabbit hole bye

133K notes

·

View notes

Text

does anyone know where i can find an online version of the complete Aarne-Thompson-Uther index??

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Okay but can you tell ME about the ATU index (I also am obsessed I just like hearing other ppl talk about it. If ur talking about the folklore one if not idk what it is but I wanna hear Abt it anyways)

OHHHHH MY GOD--

okay I stumbled across it during a particularly slow work week while goofing off on wikipedia. originally started out trying to find a list of fairy tale princesses across literature, and after spending a good chunk of time poking through the List of Fairytales list, I came across it and me personally? I think not only is it incredibly cool from a "wow, some tropes and stories truly do transcend culture and geographical boundaries" standpoint, but there are some categories that I did not know EXISTED, let alone are reocurring?

Why are so many fair maidens marrying snakes?

How is there both a suspicious amount of and suspicious lack of cannibalism?

Why is this the funniest entry I've ever seen?

I am so deeply intrigued by this index, I need to see if a library near me has the complete text edition or else I'll lose my mind

#Birdy Nerdy Chirps#every time there's a lull in the day... i think of her....ATU Index my beloved...#welcoming any and all discussion about this thing because i do not think i will ever get bored of it

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ok so weird thing that happened: a while ago I re-read scheherazade (as one does) (it’s very nice) and I was like uh. I wonder what’s the inspiration for the name. And looked it up and found out about the story. Cut to like two days later and guess what story came up during my literature class! Yeah the timing was absolutely impeccable lol

That's wild, classic Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon! And there's a chance this might keep happening to you, since "storytelling saves bride's life" is a fairly common archetype that's influenced a lot of folklore/literature over the centuries.

Btw I'm so happy ppl are still reading that fic... i'm not always proud of my old writing but i like to think Scheherazade still holds up 💚

#it's also called the frequency illusion i think#also i looked up the “telling stories saves bride's life” tale type and it's classified as Tale 875B in the ATU Index#at least according to wikipedia lmao#asks#don't think too hard about cdream = bride haha

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

boudreaux & thibodeaux and suljo & mujo are spiritual brothers

#i wish i knew what these types of jokes are called#there has to be a joke equivalent to the ATU index right#personal

0 notes

Text

#brothers grimm#grimm fairy tales#fairy tales#fairy tale retelling#fitcher's bird#bluebeard#heroine rescues her sisters#married to the devil#going through ATU index motof titles will make you excruciatingly aware of how unoriginal those awkward webtoon translated titles are#its just human nature#to circle these motifs#i like it#it feels whatever the opposite of existential is#community maybe

1 note

·

View note

Text

Welcome to another round of Two Truths and a Lie! In this one, we'll explore the ATU index, which classifies folktales into various tale types. This allows scholars to identify which stories count as the same story. Similar folktales have similar tale types, and many are subdivided into subtypes (a, b, c, etc).

Many familiar folktales have subtypes that are... let's just say less familiar. Here are two true examples and one lie:

Cinderella is tale type ATU 510a. In ATU 510b, the end of the story follows a similar arc, but begins with her escaping home after her father tries to marry her.

Rapunzel is tale type ATU 310a. In ATU 310c, she lives in an island at the middle of a lake, and her lover climbs up from the sea realm.

Beauty and the Beast is tale type ATU 425c. In ATU 425a, she is married off to an animal instead of a beast, and after inadvertently betraying him, she must go on a journey to get him back.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Diamonds, Toads, and Dark Magical Girls

According to Bill Ellis in "The Fairy-Telling Craft of Princess Tutu: Meta-Commentary and the Folkloresque," the fairy tale of Cinderella can be seen as one of the earliest examples of the transformation sequences/henshin seen in magical girl anime, particularly in how the title character is given items that help her achieve a goal, usually given to her by a magical being (her mother's spirit in a tree, a fairy godmother, etc.).

Thinking again about the connection between magical girls and fairy tales--even if they aren't as meta as Tutu, many magical girls do use imagery and ideas from European fairy tales (Sailor Moon alone has references to Hans Christian Andersen and Charles Perrault)--I wondered what other character types from the genre may have some precedent in fairy tales. Then I started thinking about the Dark Magical Girl character.

Not every magical girl story has a Dark Magical Girl, but they do crop up in a lot of works. To name a few, there's Fate Testarossa from Magical Girl Lyrical Nanoha, Homura Akemi from Puella Magi Madoka Magica, Rue/Kraehe from Princess Tutu, and countless others that would be too numerous to name. In general they tend to be more cynical, darker counterparts to the main protagonists, who tend to come from relatively more stable environments. Whatever magic they possess also may be more sinister, at least initially.

Tying in somewhat to the story of Cinderella is the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index fairy tale type "The Kind and Unkind Girls" (ATU 480). Many of the stories of this type involve a rivalry between two stepsisters, one being favored by the stepmother due to being the latter's biological daughter. The general idea in most versions of the tale is that both girls encounter a magical being at separate points in time. The kind girl helps the magical being in some way, at which point the magical being gives her a magical ability or magical presents. Meanwhile, the unkind girl refuses to help the magical being and is cursed in some fashion, or, worse, killed. The kind girl meanwhile usually ends up marrying a prince, or a similar character. One of the more popular versions of this story, "Diamonds and Toads," has the kind girl gain the ability to have a jewel or flower fall from her mouth when she speaks, while the unkind girl is cursed to have toads and snakes fall from hers. And while the kind girl does marry a prince, the unkind one is kicked out of her house and dies alone in the woods. (Insert something about Revolutionary Girl Utena's comment about how a girl who cannot become a princess is doomed to be a witch.)

Typically in these fairy tales, the unkind girl is never shown to be a real threat to the kind one; the ultimate threat is the stepmother, who uses her daughter as a means to an end. In contrast, Dark Magical Girls tend to have, well, magic that helps them attack the magical girl protagonist. In this regard, they're the Heavy in the plot, while the witch/mother-like figure/real enemy waits in the background (as is the case in a lot of magical girl shows--the Raven and Rue, Precia and Fate, Fine and Chris in Symphogear etc.). Sometimes the Dark Magical Girl will be a major threat, though--like the Princess of Disaster in Pretear (who is loosely-inspired by the Evil Queen in Snow White).

In The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales (1976), Bruno Bettelheim argues that the stepmother as a character is a way for children to process the negative traits of their own mothers, while still idealizing the good qualities of them. With that in mind, the unkind sister and the Dark Magical Girl can be viewed as a way of processing/externalizing the negative traits that a girl can have, being cruel, rebellious, and uncaring. They also embody their fears, too--the fear of being alone, rejected, and doomed to fail.

Of course, nowadays, Dark Magical Girls have a tendency to be redeemed and reconcile with/befriend the main magical girl, something the kind and unkind girls never seem to do in the fairy tales. Maybe it's just emblematic of society deciding that killing a girl off for being a little rude is a bit unfair. She's just a kid trying to find her place in the world, too, after all.

#magical girl#magical girl lyrical nanoha#puella magi madoka magica#princess tutu#senki zesshou symphogear#dark magical girl#fate testarossa#homura akemi#rue kuroha#princess kraehe#chris yukine#cinderella#diamonds and toads#kind and unkind girls#fairy tales#hans christian andersen#brothers grimm#charles perrault#bruno bettelheim#the uses of enchantment#random thoughts#text#read more

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

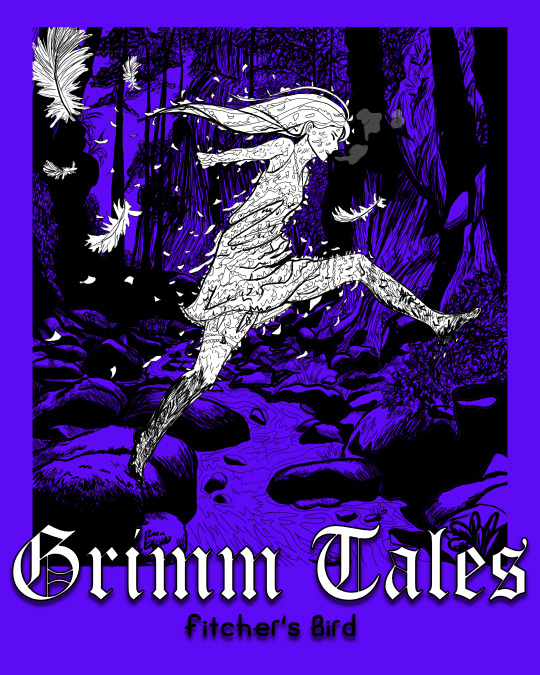

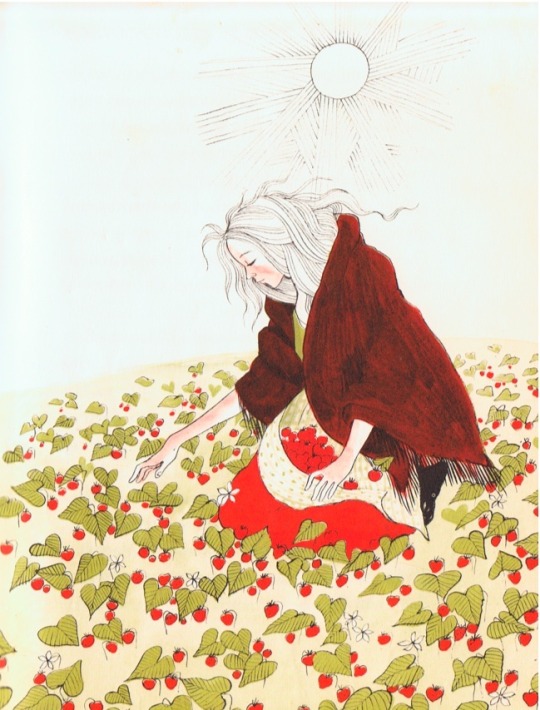

The Twelve Months/Moons, collected by Božena Němcová

According one of the Czech sources I was reading this is the oldest Czech fairy tale. In every collection I own it is the first fairy tale.

Maruška is the step-daughter of a woman who has her own daughter, Holena. Mother and daughter are jealous of Maruška’s beauty and popularity. The tale is classified in the international Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index as type ATU 480, "The Kind and Unkind Girls". Anyone who is familiar with the Brothers Grimm’s fairy tale Frau Holle (German) or Alexander Afanasyev’s Vasilisa the Beautiful (ATU 480 B, Russian, featuring our favorite witch, Baba Yaga) will recognize the theme immediately.

In each of these stories the beautiful and kind step-daughter is sent into the cold, dark woods on an impossible task by the evil step-mother.

In this case Maruška is first sent after violets in January. She encounters the personified months (moons) and impressed by her politeness as they share their fire they decide to assist her, the personification of March giving her the violets.

Next the evil step-mother and spoiled daughter send her for strawberries. This time when she encounters the months (moons) it is June who produces the most wonderful strawberries.

Next the evil step-mother and spoiled daughter send her for apples and it is September who provides them for her.

Eventually the greedy step-daughter goes off on her own seeking the magical fruit claiming Maruška will eat it all if she sends her. She encounters the months (moons) and when she is rude to them January makes a snowstorm and they all disappear leaving the girl to be left in the storm. When the evil step-mother goes looking for the daughter she is lost as well and Maruška inherits the farm lives happily ever after.

Here is an interesting paper that, in part, discusses the personification of days, weeks, months, holidays, etc. in various Slavic cultures.

Illustrators:

#1 unknown

#2 Darina Studentá

#3 Vera Stone

#4 Rodney Thompson

#5 T S Hyman

#6 illustrator unknown

#7 Jan Matulka

#fairy tale#folk tale#Czech#Slovak#the twelve months#Božena Němcová#marushka#Maruška#holena#atu 480#the kind and unkind girls#Darina Studentá#Vera stone#Rodney Thompson#t s hyman#Jan matulka

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

I headcanon that the characters like Apple, Briar, Rosabella, and Ashlynn have a very large extended diverse family

The ATU-index of related fairytales is like a family tree, For example, Cinderella atu 510

Ashlyn Ella would have african, Asian, Latino, and European distant cousins, all descendants of the first Cinderella Rhodopis, Once a year in the summer there is a family reunion.

the kids and teens play, the adults discuss political matters concerning their kingdoms and family reputation. Not everyone in the extended family is royal enough to rule, but the Cinderella family keeps a long record of Rhodopis descendants.

-

#ever after high#eah#eah confessions#mattel#apple white#eah apple#eah apple white#eah briar beauty#eah briar#briar beauty#eah rosabella#rosabella beauty#eah rosabella beauty#eah ashlynn#ashlynn ella#eah ashlynn ella

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

how goes the reading of the andersen tales? also, thoughts on the aarne-thompson-uther index?

I am approximately 2/3rds done, I took a break last week to read something else for a book club I’m in.

I’m not knowledgable enough about fairlytales and folklore to have any strong opinions on the ATU index besides it being interesting and helping me find similar and “related” stories. I imagine there is some controversy and messiness with it as is the case with all classification systems, but I haven’t read into it enough to know about that

148 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you ever made a masterpost of what sources you use to collect your folktales?

I don't have one masterpost, no. But in the tag #sources I've tried to give various people a good starting point for what they're looking for on specific subjects.

Most stories I know myself I've read in books (because I have a book hoard problem). But these are my go-to websites for when I want to link to an online text for something specific:

Grimmstories.com

Andersenstories.com

Sacred-texts.com

Heidi Anne Heiner's Surlalunefairytales.com/books

Wikipedia's fairy tale overview

And if I'm searching for something very obscure Project Gutenberg and the Internet Archive are usually my heroes.

That being said, when I'm looking into something from scratch I often start with these online collections:

D. L. Ashliman's Library of Folktales, Folklore, Fairy Tales, and Mythology, which is organised by plot or theme.

Heidi Anne Heiner's annotated tales on Surlalunefairytales.com/annotated, where well-known tales are grouped with their (usually) lesser known variants.

If I'm feeling very brave I might venture into a database of tale types and motifs:

Folkmasa.org

Thompson Folk Motif Index

University of Missouri Linked ATU Tales

Mythologydatabase.com

I think that's about it!

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

tryna find the full atu index online somewhere but its unnecessarily hard rn. like i keep finding just the original book of the atu index but thats from like 1910. there should be an scp style forum where people can classify stories and argue over whether shrek is atu 425C or a different subcategory

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queering kinship in "The Maiden who Seeks her Brothers" (A)

As I promised before, I will share with you some of the articles contained in the queer-reading study-book "Queering the Grimms". Due to the length of the articles and Tumblr's limitations, I will have to fragment them. Let's begin with an article from the Faux Feminities segment, called Queering Kinship in "The Maiden who Seeks her Brothers", written by Jeana Jorgensen. (Illustrations provided by me)

The fairy tales in the Kinder- und Hausmärchen, or Children’s and Household Tales, compiled by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm are among the world’s most popular, yet they have also provoked discussion and debate regarding their authenticity, violent imagery, and restrictive gender roles. In this chapter I interpret the three versions published by the Grimm brothers of ATU 451, “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers,” focusing on constructions of family, femininity, and identity. I utilize the folkloristic methodology of allomotific analysis, integrating feminist and queer theories of kinship and gender roles. I follow Pauline Greenhill by taking a queer view of fairy tale texts from the Grimms’ collection, for her use of queer implies both “its older meaning as a type of destabilizing redirection, and its more recent sense as a reference to sexualities beyond the heterosexual.” This is appropriate for her reading of “Fitcher’s Bird” (ATU 311, “Rescue by the Sister”) as a story that “subverts patriarchy, heterosexuality, femininity, and masculinity alike” (2008, 147). I will similarly demonstrate that “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” only superficially conforms to the Grimms’ patriarchal, nationalizing agenda, for the tale rather subversively critiques the nuclear family and heterosexual marriage by revealing ambiguity and ambivalence. The tale also queers biology, illuminating transbiological connections between species and a critique of reproductive futurism. Thus, through the use of fantasy, this tale and fairy tales in general can question the status quo, addressing concepts such as self, other, and home.

The first volume of the first edition of the Grimm brothers’ collection ap[1]peared in 1812, to be followed by six revisions during the brothers’ lifetimes (leading to a total of seven editions of the so-called large edition of their collection, while the so-called small edition was published in ten editions). The Grimm brothers published three versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” in the 1812 edition of their collection, but the tales in that volume underwent some changes over time, as did most of the tales. This was partially in an effort to increase sales, and Wilhelm’s editorial changes in particular “tended to make the tales more proper and prudent for bourgeois audiences” (Zipes 2002b, xxxi). “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” is one of the few tale types that the Grimms published multiply, each time giving titular focus to the brothers, as the versions are titled “The Twelve Brothers” (KHM 9), “The Seven Ravens” (KHM 25), and “The Six Swans” (KHM 49). However, both Stith Thompson and Hans-Jörg Uther, in their respective 1961 and 2004 revisions of the international tale type index, call the tale type “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers.” Indeed, Thompson discusses this tale in The Folktale under the category of faithfulness, par[1]ticularly faithful sisters, noting, “In spite of the minor variations . . . the tale-type is well-defined in all its major incidents” (1946, 110). Thompson also describes how the tale is found “in folktale collections from all parts of Europe” and forms the basis of three of the tales in the Grimm brothers’ collection (111).

In his Interpretation of Fairy Tales, Bengt Holbek classifies ATU 451 as a “feminine” tale, since its two main characters who wed at the end of the tale are a low-born young female and a high-born young male (the sister, though originally of noble birth in many versions, is cast out and essentially impoverished by the tale’s circumstances). Holbek notes that the role of a low-born young male in feminine tales is often filled by brothers: “The relationship between sister and brothers is characterized by love and help[1]fulness, even if fear and rivalry may also be an aspect in some tales (in AT 451, the girl is afraid of the twelve ravens; she sews shirts to disenchant them, however, and they save her from being burnt at the stake at the last moment)” (1987, 417). While Holbek conflates tale versions in this description, he is essentially correct about ATU 451; the siblings are devoted to one another, despite fearsome consequences.

The discrepancy between those titles that focus on the brothers and those that focus on the sister deserves further attention. Perhaps the Grimm brothers (and their informants?) were drawn to the more spectacular imagery of enchanted brothers. In Hans Christian Andersen’s well-known version of ATU 451, “The Wild Swans,” he too focuses on the brothers in the title. However, some scholars, including Thompson and myself, are more intrigued by the sister’s actions in the tale. Bethany Joy Bear, for instance, in her analysis of traditional and modern versions of ATU 451, concentrates on the agency of the silent sister-saviors, noting that the three versions in the Grimms’ collection “illustrate various ways of empowering the hero[1]ine. In ‘The Seven Ravens’ she saves her brothers through an active and courageous quest, while in ‘The Twelve Brothers’ and ‘The Six Swans’ her success requires redemptive silence” (2009, 45).

The three tales differ by more than just how the sister saves her brothers, though. In “The Twelve Brothers,” a king and queen with twelve boys are about to have another child; the king swears to kill the boys if the newborn is a girl so that she can inherit the kingdom. The queen warns the boys and they run away, and the girl later seeks them. She inadvertently picks flowers that turn her brothers into ravens, and in order to disenchant them she must remain silent; she may not speak or laugh for seven years. During this time, she marries a king, but his mother slanders her, and when the seven years have elapsed, she is about to be burned at the stake. At that moment, her brothers are disenchanted and returned to human form. They redeem their sister, who lives happily with her husband and her brothers.

In “The Seven Ravens,” a father exclaims that his seven negligent sons should turn into ravens for failing to bring water to baptize their newborn sister. It is unclear whether the sister remains unbaptized, thus contributing to her more liminal status. When the sister grows up, she seeks her brothers, shunning the sun and moon but gaining help from the stars, who give her a bone to unlock the glass mountain where her brothers reside. Because she loses the bone, the girl cuts off her small finger, using it to gain access to the mountain. She disenchants her brothers by simply appearing, and they all return home to live together.

In “The Six Swans,” a king is coerced into marrying a witch’s daughter, who finds where the king has stashed his children to keep them safe. The sorceress enchants the boys, turning them into swans, and the girl seeks them. She must not speak or laugh for six years and she must sew shirts from asters for them. She marries a king, but the king’s mother steals each of the three children born to the couple, smearing the wife’s mouth with blood to implicate her as a cannibal. She finishes sewing the shirts just as she’s about to be burned at the stake; then her brothers are disenchanted and come to live with the royal couple and their returned children. However, the sleeve of one shirt remained unfinished, so the littlest brother is stuck with a wing instead of an arm.

The main episodes of the tale type follow Russian folklorist Vladimir Propp’s structural sequence for fairy-tale plots: the tale begins with a villainy, the banishing and enchantment of the brothers, sometimes resulting from an interdiction that has been violated. The sister must perform a task in addition to going on a quest, and the tale ends with the formation of a new family through marriage. As Alan Dundes observes, “If Propp’s formula is valid, then the major task in fairy tales is to replace one’s original family through marriage” (1993, 124; see also Lüthi 1982). This observation holds true for heteronormative structures (such as the nuclear family), which exist in order to replicate themselves. In many fairy tales, the original nuclear family is discarded due to circumstance or choice. However, the sister in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” has not abandoned or been removed from her old family, unlike Cinderella, who ditches her nasty stepmother and stepsisters, or Rapunzel, who is taken from her birth parents, and so on. Although, admittedly, “The Seven Ravens” does not end in marriage, I do not plan to disqualify it from analysis simply because it doesn’t fit the dominant model, as Bengt Holbek does when comparing Danish versions of “King Wivern” (ATU 433B, “King Lindorm”).1 The fact that one of the tales does not end in marriage actually supports my interpretation of the tales as transgressive, a point to which I will return later.

Dundes’s (2007) notion of allomotif helps make sense of the kinship dynamics in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers.” In order to decipher the symbolic code of folktales, Dundes proposes that any motif that could fill the same slot in a particular tale’s plot should be designated an allomotif. Further, if motif A and motif B fulfill the same purpose in moving along the tale’s plot, then they are considered mutually substitutable, thus equivalent symbolically. What this assertion means for my analysis is that all the methods by which the brothers are enchanted and subsequently disenchanted can be treated as meaningful in relation to one another. One of the advantages of comparing allomotifs rather than motifs is that we can be assured that we are analyzing not random details but significant plot components. So in “The Six Swans” and “The Seven Ravens,” we see the parental curse causing both the banishment and the enchantment of the brothers, whereas in “The Twelve Brothers,” the brothers are banished and enchanted in separate moves. Even though the brothers’ exile and enchantment happen in a different sequence in the different texts, we must view their causes as functionally parallel. Thus the ire of a father concerned for his newborn daughter, the jealous rage of a stepmother, the homicidal desire of a father to give his daughter everything, and the innocent flower gathering of a sister can all be seen as threatening to the brothers. All of these actions lead to the dispersal and enchantment of the brothers, though not all are malicious, for the sister in “The Twelve Brothers” accidentally turns her brothers into ravens by picking flowers that consequently enchant them.

I interpret this equivalence as a metaphorical statement—threats to a family’s cohesion come in all forms, from well-intentioned actions to openly malevolent curses. The father’s misdirected love for his sole daughter in two versions (“The Twelve Brothers” and “The Seven Ravens”) translates to danger to his sons. This danger is allomotifically paralleled by how the sister, without even knowing it, causes her brothers to become enchanted, either by picking flowers in “The Twelve Brothers” or through the mere incident of her birth in “The Twelve Brothers” and “The Seven Ravens.” The fact that a father would prioritize his sole daughter over numerous sons is strange and reminiscent of tales in which a father explicitly expresses romantic de[1]sire for his daughter, as in “Allerleirauh” (ATU 510B), discussed in chapter 4 by Margaret Yocom. Even in “The Six Swans,” where a stepmother with magical powers enchants the sons, the father is implicated; he did not love his children well enough to protect them from his new spouse, and once the boys had been changed into swans and fled, the father tries to take his daughter with him back to his castle (where the stepmother would likely be waiting to dispose of the daughter as well), not knowing that by asserting control over her, he would be endangering her. The father’s implied ownership of the daughter in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” and the linking of inheritance with danger emphasize the conflicts that threaten the nuclear family. Both material and emotional resources are in limited supply in these tales, with disastrous consequences for the nuclear family, which fragments, as it does in all fairy tales (see Propp 1968).

Holbek reaches a similar conclusion in his allomotific analysis of ATU 451, though he focuses on Danish versions collected by Evald Tang Kristensen in the late nineteenth century. Holbek notes that the heroine is the actual “cause of her brothers’ expulsion in all cases, either—innocently—through being born or—inadvertently—through some act of hers” (1987, 550). The true indication of the heroine’s role in condemning her brothers is her role in saving them, despite the fact that other characters may superficially be blamed: “The heroine’s guilt is nevertheless to be deduced from the fact that only an act of hers can save her brothers.” However, Holbek reads the tale as revolving around the theme of sibling rivalry, which is more relevant to the cultural context in which Danish versions of ATU 451 were set, since the initial family situation in the tale was not always said to be royal or noble, and Holbek views the tales as reflecting the actual concerns and conditions of their peasant tellers (550; see also 406–9).2 Holbek also discusses the lack of resources that might lead to sibling rivalry, identifying physical scarcity and emotional love as two factors that could inspire tension between siblings.

The initial situation in the Grimms’ versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” is also a comment on the arbitrary power that parents have over their children, the ability to withhold love or resources or both. The helplessness of children before the strong feelings of their parents is cor[1]roborated in another Grimms’ tale, “The Lazy One and the Industrious One” (Zipes 2002b, 638).3 In this tale, which Jack Zipes translated among the “omitted tales” that did not make it into any of the published editions of the KHM, a father curses his sons for insulting him, causing them to turn into ravens until a beautiful maiden kisses them. Essentially, the fam[1]ily is a site of danger, yet it is a structure that will be replicated in the tale’s conclusion . . . almost.

But first, the sister seeks her brothers and disenchants them. The symbolic equation links, in each of the three tales, the sister’s silence (neither speaking nor laughing) for six years while sewing six shirts from asters, her seven years of silence (neither speaking nor laughing), and her cutting off her finger and using it to gain entry to the glass palace where she disenchants her brothers merely by being present. The theme unifying these allomotifs is sacrifice. The sister’s loss of her finger, equivalent to the loss of her voice, is a symbolic disempowerment. One loss is a physical mutilation, which might not impair the heroine terribly much; the choice not to use her voice is arguably more drastic, since her inability to speak for herself nearly causes her death in the tales.4 Both losses could be seen as equivalent to castration.5 However, losing her ability to speak and her ability to manipulate the world around her while at the same time displaying domestic competence in sewing equates powerlessness with feminine pursuits. Bear notes that versions by both the Grimms and Hans Christian Andersen envision “a distinctly feminine savior whose work is symbolized by her spindle, an ancient emblem of women’s work” (2009, 46). Ruth Bottigheimer (1986) points out in her essay “Silenced Women in Grimms’ Tales” that the heroines in “The Twelve Brothers” and “The Six Swans” are forced to accept conditions of muteness that disempower them, which is part of a larger silencing that occurs in the tales; women both are explicitly forbidden to speak, and they have fewer declarative and interrogative speech acts attributed to them within the whole body of the Grimms’ texts.

Ironically, in performing subservient femininity, the sister fails to perform adequately as wife or mother, since the children she bears in one version (“The Six Swans”) are stolen from her. When the sister is married to the king, she gives birth to three children in succession, but each time, the king’s mother takes away the infant and smears the queen’s mouth with blood while she sleeps (Zipes 2002b, 170). Finally, the heroine is sentenced to death by a court but is unable to protest her innocence since she must not speak in order to disenchant her brothers. In being a faithful sister, the heroine cannot be a good mother and is condemned to die for it. This aspect of the tale could represent a deeply coded feminist voice.6 A tale collected and published by men might contain an implicitly coded feminist message, since the critique of patriarchal institutions such as the family would have to be buried so deeply as to not even be recognizable as a message in order to avoid detection and censorship (Radner and Lanser 1993, 6–9). The sis[1]ter in “The Six Swans” cannot perform all of the feminine duties required of her, and because she ostensibly allows her children to die, she could be accused of infanticide. Similarly, in the contemporary legend “The Inept Mother,” collected and analyzed by Janet Langlois, an overwhelmed mother’s incompetence indirectly kills one or all of her children.7 Langlois reads this legend as a coded expression of women’s frustrations at being isolated at home with too many responsibilities, a coded demand for more support than is usually given to mothers in patriarchal institutions. Essentially, the story is “complex thinking about the thinkable—protecting the child who must leave you—and about the unthinkable—being a woman not defined in relation to motherhood” (Langlois 1993, 93). The heroine in “The Six Swans” also occupies an ambiguous position, navigating different expectations of femininity, forced to choose between giving care and nurturance to some and withholding it from others.

Here, I find it productive to draw a parallel to Antigone, the daughter of Oedipus. Antigone defies the orders of her uncle Creon in order to bury her brother Polyneices and faces a death sentence as a result. Antigone’s fidelity to her blood family costs her not only her life but also her future as a productive and reproductive member of society. As Judith Butler (2000) clarifies in Antigone’s Claim: Kinship between Life and Death, Antigone transgresses both gender and kinship norms in her actions and her speech acts. Her love for her brother borders on the incestuous and exposes the incest taboo at the heart of kinship structure. Antigone’s perverse death drive for the sake of her brother, Butler asserts, is all the more monstrous because it establishes aberration at the heart of the norm (in this case the incest taboo). I see a similar logic operating in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers,” because according to allomotific equivalences, the heroine is condemned to die only in one version (“The Six Swans”) because she allegedly ate her children. In the other version that contains the marriage episode (“The Twelve Brothers”), the king’s mother slanders her, calling the maiden “godless,” and accuses her of wicked things until the king agrees to sentence her to death (Zipes 2002b, 35). As allomotific analysis reveals, in the three versions, the heroine is punished for being excessively devoted to her brothers, which is functionally the same as cannibalism and as being generally wicked (the accusation of the king’s mother in two of the versions).

In a sense, the heroine’s disproportionate devotion to her brothers kills her chance at marriage and kills her children, which from a queer stance is a comment on the performativity of sexuality and gender. According to Butler, gender performativity demonstrates “that what we take to be an internal essence of gender is manufactured through a sustained set of acts, posited through the gendered stylization of the body” ([1990] 1999, xv). This illusion, that gender and sexuality are a “being” rather than a “doing,” is constantly at risk of exposure. When sexuality is exposed as constructed rather than natural, thus threatening the whole social-sexual system of identity formation, the threat must be eliminated.

One aspect of this system particularly threatened in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” is reproductive futurism, one form of compulsory teleological heterosexuality, “the epitome of heteronormativity’s desire to reach self-fulfillment by endlessly recycling itself through the figure of the Child” (Giffney 2008, 56; see also Edelman 2004). Reproductive futurism mandates that politics and identities be placed in service of the future and future children, utilizing the rhetoric of an idealized childhood. In his book on reproductive futurism, Lee Edelman links queerness and the death drive, stating, “The death drive names what the queer, in the order of the social, is called forth to figure: the negativity opposed to every form of social viability” (2004, 9). According to this logic, to prioritize anything other than one’s reproductive future is to refuse social viability and heteronormativity—this is what the heroine in “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” does. Her excessive emotional ties to her brothers disfigure her future, aligning her with the queer, the unlivable, and hence the ungrievable. Refusing the linear narrative of reproductive futurism registers as “unthinkable, irresponsible, inhumane” (4), words that could very well be used to describe a mother who is thought to be eating her babies and who cannot or will not speak to defend herself.

The heroine’s marriage to the king in two versions of the tale can also be examined from a queer perspective. Like the tale “Fitcher’s Bird,” which queers marriage by “showing male-female [marital] relationships as clearly fraught with danger and evil from their onset,” the Grimms’ two versions of ATU 451 that feature marriage call into question its sanctity and safety (Greenhill 2008, 150, emphasis in original). Marriage, though the ultimate goal of many fairy tales, does not provide the heroine with a supportive or nurturing environment. Bear comments that in versions of “The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers” wherein a king discovers and marries the heroine, “the king’s discovery brings the sister into a community that both facilitates and threatens her work. The sister’s discovery brings her into a home, foreshadowing the hoped-for happy ending, but it is a false home, determined by the king’s desire rather than by the sister’s creation of a stable and complete community” (2009, 50)

#queering the grimm#queering the grimms#queer fairytales#the maiden who seeks her brothers#the twelve brothers#the six swans#the seven ravens#grimm fairytales#fairytale analysis#fairytale type

22 notes

·

View notes