#Alexander's army

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Forgive me if this is a very elementary question (inspired after watching your TikToks!!) but… I’ve always been curious: what exactly was the role of a secretary in the Macedonian court such that Eumenes could wield so much power and influence, especially during the Successor Wars? Like, to the point that the Chilliarch, the second-in-command to the king himself, would have beef with him? I guess when I think of a secretary, I envision the more stereotypical modern version of them, which is like an executive assistant, or the front desk receptionist, or a customer service agent, which obviously seems to be anachronistic. But I’m just struggling to comprehend what would have made Eumenes, or the role he occupied, such a controversial figure.

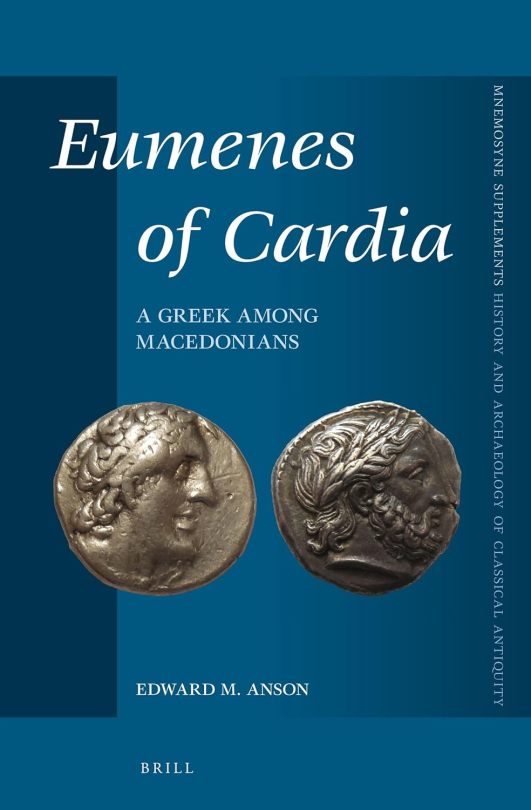

First, let me point to an important book by my colleague, Ed(ward M.) Anson, Eumenes of Cardia: a Greek among Macedonians (2nd ed., 2015). It’s a quite excellent discussion of Eumenes’s career, and was actually Ed’s dissertation topic. I reckon, like me, he waited a long while before turning the dissertation into a monograph (even the 1st edition). Alas, it’s expensive. Even I don’t own a copy, as I have access to the university library’s. But I do recommend that folks interested request it via Interlibrary Loan (ILL). Even smaller public libraries offer that service, although you might have to pay a (relatively) small shipping fee.

So, Eumenes is an interesting character in many ways. As you suggest, “secretary” gives the wrong impression. The word in Greek is grammateus, and it can mean any sort of scribe, clerk, records keeper…or the official in charge of the whole royal office: official correspondence, what letters the king actually saw, the keeping of the Royal Journal and other state records, etc., etc. A hugely influential position, his might be closer to what we’d call, in the US, the Chief of Staff.

In my opinion, that was the heart of Eumenes’s dislike of Hephaistion. I said it in my dissertation and still think it’s true. When Hephaistion was made Chiliarch, that put him above Eumenes in administration around Alexander. The Chief of Staff got demoted…and didn’t like it. It’s from Susa onward that the two men seem to clash—at least twice that we know about. (I differ with Ed on this; he thinks it was about personalities while I think it was more political- and status-driven.)

That Eumenes was loyal to Alexander—and the Argead family—isn’t in question. But it wasn’t just Hephaistion he had trouble with. We know he also didn’t like Antipatros—one reason he sided with Perdikkas, even when (his friend) Krateros joined Antipatros. He also had a long-standing family beef with Hekataios of Kardia, and later hated Kassandros (as the son of Antipatros). But he seems to have got on with Olympias and Kleopatra—who he tried to get Perdikkas to marry. Perdikkas took his advice and divorced Antipatros’s daughter Nikaia, which eventually led to his downfall. One can’t escape the sense that Eumenes was touchy. Then again, as I’ve said before, they all were. And he had to put up with being constantly looked down on both as a “mere secretary” and as a Greek among Macedonians. He advanced on Alexander’s favor…which probably made others jealous of him. In fact, I think that’s one reason he took Hephaistion’s promotion hard. He’d worked hard for Chief of Staff, and didn’t like Hephaistion butting in. And if Hephaistion was also of Greek descent (as I’ve argued), both may have had a sense that there was room only for one. Or at least Eumenes may have thought so.

Men in his position weren’t normally entrusted with military commands, but he proved to be surprisingly good and, according to Ed, probably had more army assignments during Alexander’s lifetime than he’s credited with. (He was allied with Ptolemy’s enemy, Perdikkas, remember and Ptolemy was Arrian’s chief military source.) When Perdikkas was elevated to Hephaistion’s position, Eumenes took Perdikkas’s old command, and later, was himself Chilliarch. The infantry seems to have liked/trusted him, and later, he was quite successful at securing Cappadocia. In fact, during the early Diadochi wars, it was his stratagem that defeated Krateros’ army and got him killed (perhaps to his own regret, although I think Plutarch exaggerated that account). He also fought—one-on-one—against Neoptolemos … another of Alexander’s officers he couldn’t stand. And beat him. Neoptolemos was a demonstrated military commander.

So he seems to have defied the usual expectation of what a grammateus could do—and become. He was the highest ranking Greek in Alexander’s army, the only one to really rub shoulders with the Macedonian inner circle.

EDIT: I realized I forgot Nearchos. So Eumenes AND Nearchos were the two top-ranked Greeks at Alexander's court at his death. But if anything, Eumenes had edged Nearchos in place.

#alexander the great#Eumenes#ancient Macedonia#Alexander's army#Hephaistion#Krateros#Hephaestion#Craterus#Antipatros#Perdikkas#Perdiccas#Olympias#Kleopatra#Cleopatra of Macedon#Alexander the Great's secretary#Chiliarchy#ancient Greece#Classics#Ptolemy#tagamemnon

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

#polls#movies#hellboy ii: the golden army#hellboy ii the golden army#hellboy ii#the golden army#hellboy#2000s movies#guillermo del toro#ron perlman#selma blair#doug jones#john alexander#seth macfarlane#requested#have you seen this movie poll

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

TS4 Washington's Headquarters - 30x20* (NO CC)

Washington's Headquarters at Valley Forge, built as accurately as possible in the Sims 4! This was the site of General Washington's command post and living quarters, where he and his aides-de-camp stayed during the winter encampment of 1777-78.

I visited the Valley Forge National Historical Park and tried to recreate the headquarters as faithfully as possible, though some areas were not open to the public (like the basement cellar, which is where I included a full bath for Sim functionality; I assume it was intended for storage), and I had to make the hallway larger to fit the stairs (the real house is very small!).

★ You can see the reference photos I took at Valley Forge here (Google Drive) - feel free to download them for yourself :)

*The house by itself is 20x15 tiles.

➜ download my TS4 builds: my EA ID is jhocaa / my TS4 builds

#sims 4#my builds#sims build#amrev#the sims 4#ts4 build#george washington#valley forge#historical#18th century#sims 4 historical#sims 4 hamilton#american revolution#revolutionary war#general washington#colonial america#continental army#historical alexander hamilton#historical john laurens#washington's headquarters

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

what a dork he’s literally cosplaying

#THE ARMY ISNT EVEN ASSEMBLED YET#HE TOOK OUT THE COSPLAY FROM THE CLOSET#dgaf a fuck about his wife that’s crying#this is gold#alexander hamilton

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

john laurens is army dreamers coded honestly

#hamilton musical#hamilton fanart#alexander hamilton#john laurens#lams#i listened to army dreamers on repeat while drawing this#pain and suffering ❤

321 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Findings For Alexander Hamilton’s Artillery Company!!

Today I came across “new” (new to me, anyway--nor have I seen a Hamilton biographer or scholar mention this) Captain Hamilton information and I feel bad for the people within my vicinity inside my campus library who had to hear my shocked squeal.

Within the Henry Knox Papers of the Gilder Lehrman Collection held by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History is an “Artillery record book” which was written by Colonel Samuel Shaw for Knox’s regiment of artillery between January 12, 1777 and March 24, 1777. The book itself is only 16 pages (which includes the cover page), but it contains all sorts of troop movements, artillery inventory, and other notes.

The following (under the cut) is a chronological rundown of all the times Hamilton or his men are mentioned in the book, along with the images themselves (as unfortunately the database that the Knox Papers were digitized to, American History 1493-1945, is limited to institutional access. However, it can be found here):

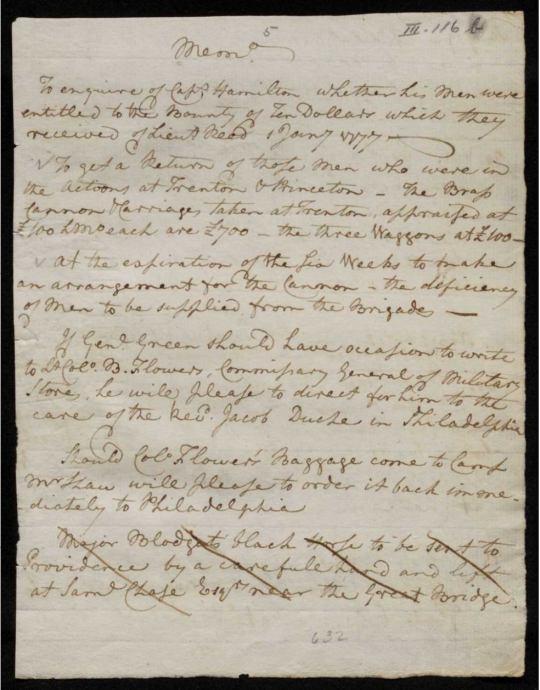

First up, on page five (seen above), Colonel Shaw wrote a series of "memos," or tasks needing completion. One of these, as seen at the top of the page, included "To enquire of Capt Hamilton whether his men were entitled to the Bounty of Ten Dollars which they received of Lieut Reed 1 Jany [January] 1777 --". The start of the new year came of course on the heels of the Battle of Trenton fought on December 26, 1776, wherein Hamilton's cannons played a major role.

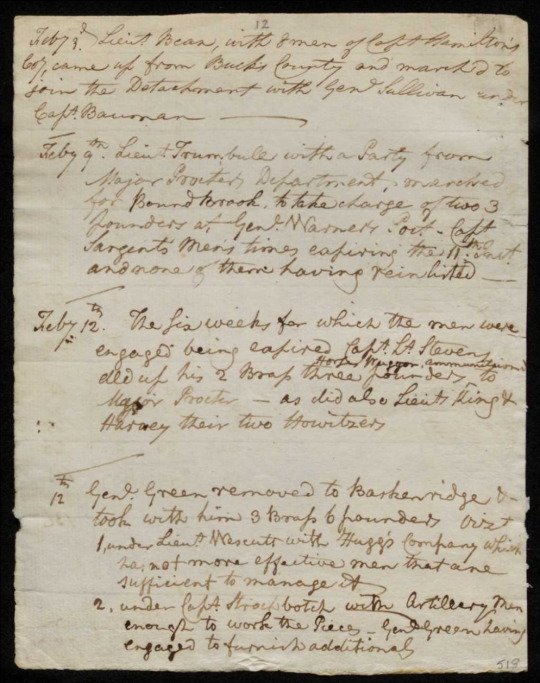

Next (and the most interesting to me), on page twelve (seen above) Shaw wrote a series of troop movements. Dated February 3, 1777, the colonel wrote that "Lieut [John] Bean, with 8 men of Capt Hamilton's Coy [Company] came [up?] from Bucks County and marched to join the Detachment with Genl [John] Sullivan and Capt [Sebastian] Bauman --". At this time, Hamilton was still in recovery from the illness he developed prior to Trenton, and the only other remaining officer in his company was his Third Lieutenant Thomas Thompson. This would thus mean that Hamilton and Thompson were left to watch over those that remained with the company while Bean and eight enlisted men were away.

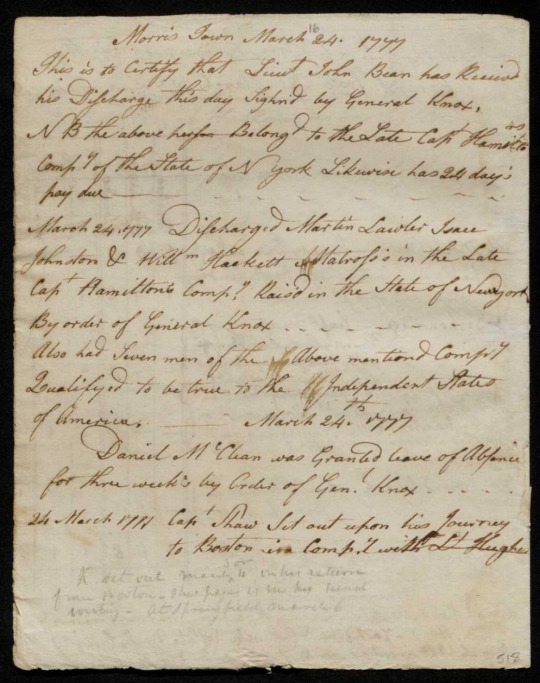

Lastly, on the final page of the record book (seen above) a series of discharges for men in Hamilton's company were written on March 24, 1777. By that time, Alexander Hamilton had joined Washington's staff as an aide-de-camp. Colonel Shaw, and another person who has not been identified, explicitly wrote:

Morris Town March 24, 1777

This is to certify that Lieut John Bean has Received his Discharge this day Sign'd by General Knox, N B the above person Belong'd to the late Capt Hamilton's Compy [Company] of the State of N[ew] York Likewise has 24 days pay due --

March 24, 1777 Discharged Martian Laulen[,] Isaac Johnston & Will'm [William] Hackett Matross's in the Late Capt Hamilton's Compy, Rais'd in the State of New York By order of General Knox . . . .

Also had seven men of the above mentioned compy Qualifyed [Qualified] to be true to the Independent States of America --

Note: the names of the matrosses discharged were cross-referenced with the names found in Alexander Hamilton's artillery company pay book for making my above transcription.

This entire record makes me extremely happy. I have new dates and more minute details and therefore a more concrete timeline surrounding Hamilton and the men of his company, yay!! Lately I have become very interested in the company's continuing service in the American Revolution after Hamilton's departure, and this record just gave me some fascinating information that links to some other information I have found on the whereabouts of some of these men written about above. But this is daring to open a can of worms that should be saved for a later post.

Frankly, it does not surprise me that I have not read about this record previously. It is so detailed and routine that it doesn't stand out necessarily on its own in the wider scope of things. However, as regards The American Icarus (and another project I may or may not be considering tackling?), this new information is very interesting and helpful. And I hope someone else here finds it interesting too.

#I would update my captain hamilton timeline if not for having hit my image and hyperlink limit on that post 😭#grace's random ramble#alexander hamilton#amrev#historical alexander hamilton#captain hamilton#henry knox#amrev fandom#historical hamilton#american revoluton#historical documents#18th century letters#continental artillery#continental army#george washington#battle of trenton#american history#historical research#historical resources#henry knox papers#gilder lehrman institute of american history#the american icarus#TAI#my projects#my writing#writeblr#new york provincial company of artillery

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm dropping (a bit old) john laurens yap here. Please correct anything you must + provide the source.

and we know very limited about John but whatever !!

Laurens was described by Hamilton to have honey blonde hair when clean. His hair was generally said to be light brown/blonde. As seen on portraits, he had soft features, blue eyes, and a big nose. He was described to be very handsome, and IMO I agree!! We don't know exactly how tall he was, but he was most likely over 6 feet. One day before Laurens' 15th birthday, his father wrote to James Grant; ''my Little Jack, now as big as I am...'' (Jack being John's nickname). We don't know Henry Laurens' height, but if he was as tall as Henry at 15, he certainly grew to be taller. In 1778, Henry wrote to John ''A Taylor has cut off as much of your Scarlet as will make he says a Wascoat for 6 feet 3 inches...'' which suggests that John could have been 6'3. It's not clear what exactly Henry means in the letter but as said, John was probably over 6 feet. Laurens was one of the strongest abolitionists of the time despite coming from one of the bigger slave plantations and growing up where slavery was normal. John could speak English, French, Italian, Greek, Spanish and Latin. We know that he was fluent in English and French but we don't know about his fluency in the other languages.

Laurens got Martha Manning pregnant and ended up marrying her out of pity (supposedly to protect her reputation too and to keep illegitimacy of their child.) He wrote to his uncle ''...Pity has obliged me to marry...'', When Laurens left for war, he left his pregnant wife in another country. When John was chosen by congress to be a special minister to France and had him travel there, Martha traveled with their daughter to reconnect with him upon hearing about his arrival in France. But John supposedly made no effort whatsoever to visit them; he completed his mission and went back to America. Martha later died during the trip and their daughter, Frances, was sent to live with her aunt.

John Laurens is believed to have been gay... The man didn't seem to express any attraction towards women, though I think his sexist beliefs played a role in this, as well as his lack of effort to humble his wife. His letters to Alexander Hamilton, and Francis Kinloch also suggest he had an eye for men... ESPECIALLY Kinloch's and his correspondence.

Henry Laurens wrote ''Master Jack is too closely wedded to his studies to think about any of the Miss Nanny's''. But it's important to note that he was a teenager at that time and not every teen develops those feelings at the same time. But I would imagine that since he was as tall as his father at 15, he was early in puberty... Romantic/sexual feelings usually come with puberty, but what do we know? Anyways. John expressed a lot of sexist opinions, even towards his own sisters, which can be read in letters. Most men were sexist, but John seemed to be more ''strict'' on the subject... This definitely plays a part in his supposed ''homosexuality''.

John hid the fact that he had a wife and child from Hamilton for nearly two years. Why? The reason is unknown. It's only up to debate. My guess is that he just wanted to try to ''forget'' them in some way, seeing as he literally left them... Why would you bring up that you have a family that you abandoned? But maybe it was because he never found the right time to tell him, or was it to get a better chance with Hamilton? We will never know, sadly. But what we DO know, is that Laurens referred to his wife as ''dear girl'', and Hamilton, and supposedly ONLY Hamilton, as ''Dear boy''. We know for a fact that Hamilton was close to Laurens and was special to him, but why did he call his wife that? Out of pity? He didn't necessarily show any real attraction towards her... But whatever the reason is, it's kinda cute.

We know that Henry Laurens was emotionally manipulative of John, which is like read in letters... So there is no denying that, really. BUT John was close to his father, attachment issues tsk, tsk tsk... But jokes aside, when John told his father that he wasn't super interested in becoming a lawyer or merchant like his father wanted, Henry wrote this to his brother; ''if he enters upon the plan of Life which he Seemed to pant for when he wrote the 5th. July, I Shall give him up for lost & he will very Soon reproach himSelf for his want of Duty & affection towards me, for abandoning his Brothers & Sisters, for disregarding the Council of his Uncle, & for his deficiency of common understanding, in making Such a choice_ if these reflections prevail not over him, nothing will_ he must have his own way & I must be content with the remembrance, that I had a Son.'' Basically, Henry said he would disown John if he pursued his interests in medicine. So, John ended up becoming a lawyer/statesman to please his father. There are more examples of John trying to please his father, but let's not take that now... HOWEVER, after John had died, Henry wrote of him in response to John Adams' letter; ''Thank God I had a Son who dared to die in defence of his Country'' ... We get a lot of mixed signals from Henry... Though I do believe he loved him, at least somewhat.., even if he was controlling/manipulative. Henry wasn't too nice to his other children either, but since this is about John I'm not gonna talk about that.

John's brother James died at the age of 9-10 (1765-1775)

James, or Jemmy, was supposedly scaling the outside of their house and tried to jump to the landing outside of John’s window but fell. He received life threatening injuries and cracked his skull. The doctors had figured that the injuries were too severe to save him and John described it to his uncle four days later; "At some Intervals he had his senses, so far as to be able to answer single Questions, to beckon to me, and to form his Lips to kiss me, but for the most part he was delirious, and frequently unable to articulate. Puking, Convulsions never very violent, and latterly so gentle as scarcely to be perceived, or deserve the Name, ensued, and Nature yielded."

Since John was supposed to watch over James during this time, John felt guilty and as if it was his fault. James' death was very difficult for John, and it weighed heavily on him.

Henry did little to alleviate those feelings of guilt, which suggests that he either didn't care enough, or that a part of him also blamed John. (I am not saying he 100% did, but it would not be surprising if he so did, considering how he treated John.)

He could also have been in too much grief to console John... Which, as said, would not be too surprising considering his treatment of John. But nevertheless, he did not do much to help John and John's guilt.

TW: mentions of suicide.

It is highly speculated that John was suicidal. We have a couple of written exchanges where John discusses suicide with friends and family. In February 1774, John wrote to Henry Laurens about two men who had attempted suicide. We don't have the whole letter, but here is a part of Henry's response; ''...But, my Dear Son, I trust that your opinion on that Question is So firm, that you are armed with Such irrefragable proofs of the Impiety as well as Cowardice of Self Murther, as puts you out of danger of being made a Convert to Error...'' (Not gonna put all of it). Another time, when John was a prisoner of war and didn't handle imprisonment well, Hamilton wrote to John ''For your own sake, for my sake, for the public sake, I shall pray for the success of the attempt (of being exchanged) you mention; that you may have it in your power to act with us. But if you should be disappointed, bear it like a man; have recourse, neither to the dagger, nor to the poisoned bowl, nor to the rope.'' It is clear that Hamilton (and Henry, despite how he treated John) were worried about John's thoughts of suicide. John's last letter to Hamilton was probably one of the, if not the, most emotional. He wrote ''Adieu, my dear friend; while circumstances place so great distance between us, I entreat you not to withdraw the consolation of your letters. You know the unalterable sentiments of your affectionate Laurens.'' John died about a month later. On the day of his death, John and his men surprised a troop of British soldiers that outnumbered them. Instead of retreating, John chose to immediately attack. He did not really actively end his own life, though it seems as if it was planned or that he was trying. Which is just sad. Also, it's not sure that Hamilton's last letter to Laurens ever got to him before he died. (In that letter he tells John to quit his sword and come to congress with Hamilton)

I don't know what else to add actually but here you have it!! This is as accurate as I can get it, especially cause it's like mostly based on letters... Uhm. But yay!

#john laurens#hamilton#alexander hamilton#hamilton musical#historical alexander hamilton#historical john laurens#turn washington's spies#liberty's kids#eliza schuyler#george washington#history#american history#abolitionist#american revolution#revolutionary war#historical figures#american soldier#continental army#congress#henry laurens#jassesham

91 notes

·

View notes

Note

How did Alexander become adept at recruiting, managing and commanding such a vast multicultural army out of nowhere?

My understanding is that he led a broad Greek army, with the regional differences pertinent to each region or polity, but still self-identifying as Greek. This seems very different from the armies he led later on in the later part of his reign, with completely different languages, religions, identities. How did this change happen so successfully?

I think a lot of us would like to know that. Ha.

This is a good example of the logistical matters that the ancient sources simply don't tell us, except in occasional throw-away lines.

For instance, we know that Eumenes needed an interpreter to give orders to his Macedonian troops, in the later Successor Wars. This was, in fact, one of the details that led some historians to doubt whether "Makedoniste" ("to speak in the Macedonian manner") was Greek. We now know it was (a form of Doric), but apparently, that was so different--especially when spoken--that some (maybe a lot) of his Macedonian troops couldn't understand Eumenes's Attic Greek. Also, we may guess that these were more complicated orders, and that in the heat of battle, he could give (and they understood) simpler commands.

What this little incident tells us, however, is that the army had interpreters readily available. And some officers were bilingual (such as Peukestes--why he became satrap of Persia). Also, as suggested, it's highly likely that everyone had learned certain, simple commands. Things such as "Forward!" and "Fall back!" etc. Also, if you've ever been in a country where you don't/can't speak the language, a lot of gesturing is involved. (LOL) And some pidgin.

But we reason out this; we aren't told it in so many words. Also, it seems to have come in waves.

Alexander began to accept non-Macedonian/non-Greek troops after Darius's death, when some Persians and some central Asians (from the Baktrian area) were integrated. This is also when he instituted the training in Macedonian arms of the epigoni (upper-class Persian/other youths), which apparently included some Greek instruction, too.

I'm not sure he ever had that many Indian troops, but when he got back into Persia in 324, that was a second (larger) wave of incorporation of "foreign" (Persian primarily) troops into the army. Plus the epigoni arrived, after having been training a few years by then. According to what little we are told, these seem to be separate units presumably with their own commanders, speaking their own language. So by "integrating," that doesn't mean they were scattered in battalions right alongside Macedonians. That means he had different units of troops: so one (new) unit of Persian Companions was added to the pre-existing hipparchies, for instance.

I'd also point out that the Persians had been using integrated armies for well over a century, so Alexander had a model to follow. Why reinvent the wheel?

Hope that clarifies.

#Alexander the Great#Alexander's army#ancient Macedonia#ancient Persia#military history#Eumenes#asks

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

BEAUTY

For me beauty is vulnerability...it is the way we present ourselves as naked souls, undressing every layer of the façade that covered our true, hidden intentions. How beautiful it is to surrender yourself to someone...to entrust them with all of you and not regret...

-leolovesyoumore

#aesthetic#aespa#alexander mcqueen#alternative#animation#architecture#art#ao3#adidas#35mm#dead poets society#poetry#poet#poem#spilled poetry#spilled ink#spilled thoughts#poetic#love poem#poets on tumblr#original poem#writers and poets#love letters#love quotes#self love#lol#bts army#bts#love#poems on tumblr

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kind of wanting to put these phone wallpapers I made years ago here. If you watch Turn: Washington's Spies, these are for you.

Series: Turn: Washington's Spies (2014-2017)

#turn washington's spies#benjamin tallmadge#george washington#marquis de lafayette#alexander hamilton#continental army#revolutionary war#period drama#phone wallpaper

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexander the Great at the Battle of the Granicus Against the Persians

Artist: Cornelis Troost (Dutch, 1696-1750)

Date: 18th century

Medium: Oil painting

Description

This painting, created by the Dutch artist Cornelis Troost (c. 1697-1750), was inspired by the Battle of the Granicus, fought between Alexander the Great and the Persians in 334 BCE. It was the first major pitched battle that occurred after Alexander the Great crossed into Anatolia and invaded lands controlled by the Achaemenid Empire, then ruled by Darius III (r. 336-330). In choosing to engage the enemy at the Granicus River, Alexander the Great handicapped himself, for he would have to ford through the water in order to strike at his foes. If, however, he could beat the odds as well as the opposing army, it would add further to the renown and distinction gained from the victory.

At the start of the battle, Alexander brought his army to the banks of the Granicus in battle array, with the Persians matching him on the other side. Alexander positioned himself with the troops on the right flank of his army, and he sent the other columns on his left to begin marching into the water of the river. Although Alexander had other columns advance first, it was his own cavalry force positioned on the right side that would be the real threat to the Persians. While the opposing army was distracted by the marching infantry, Alexander the Great charged across the river with his cavalry from the side and, as he often did, began fighting his way straight for the Persian commanders. The Roman historian, Arrian (90-173+), described this cavalry charge:

“The first to engage the Persians were cut down and died a soldier’s death, though some of the leading troops fell back upon Alexander, who was now on his way across: indeed, he was almost over, at the head of the army’s right wing. A moment later he was in the thick of it, charging at the head of his men straight for the spot where the Persian commanders stood and the serried ranks of the enemy horse were thickest. Round him a violent struggle developed, while all the time, company by company, the Macedonians were making their way over the river, more easily now than before” (Arrian, Anabasis, 1.15).

Such is the spirit of the scene that Cornelis Troost endeavored to re-create in his painting. On the left side, the first waves of troops that crossed the river can be seen in the heat of battle. Alexander is shown in the center of the painting, joining the battle by the riverbank. In the background of the right side of the artwork, more forces can be seen wading through the water toward the scene of battle. Alexander, of course, went on to win the Battle of the Granicus in 334 BCE. Over the next years, the Achaemenid Empire would be dismantled by further battles and conquests carried out by Alexander the Great.

#painting#historical art#alexander the great#oil painting#landscape#artwork#fine art#battle of the granicus#ancient history#persian army#granicus river#battle#horses#armour#sword#dutch culture#cornelis troost#dutch painter#cornelist troost#troops#riverbank#european art#18th century painting

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Axel Von Fersen X Marquis De Lafayette (>3<)

they're so cute oml I cant

❀•°•═════ஓ๑♡๑ஓ═════•°•❀

Ferfayette is random but listen they're so cute 💔💔 (and underrated)

Anyways it's Napoleons birthday today so happy birthday!! 💪💪

#art#fanart#history#amrev history#amrev#amrev fandom#marquis de lafayette#axel von fersen#ferfayette#lersen#historical#ship art#american revolution#revolution#george washington#alexander hamilton#john laurens#continental army

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

so all the descriptions of people calling hamilton "slender" "small" "youth" "stripling" and "boyish" are just telling me that he had the look vibe and body of timothee chalamet is that correct

#ham was a captain in the army and the person went “what is a boy doing here”#honestly timothee in cmbyn is probably exactly ham's body type when he was younger#alexander hamilton#historical hamilton#amrev#hamilton

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captain Alexander Hamilton: A Timeline

As Alexander Hamilton’s time serving as Captain of the New York Provincial Company of Artillery is about to become my main focus within The American Icarus: Volume I, I wanted to put a timeline together to share what I believe to be a super fascinating period in Hamilton's life that’s often overlooked. Both for anyone who may be interested and for my own benefit. If available to me, I've chosen to hyperlink primary materials directly for ease. My main repositories of info for this timeline were Michael E. Newton's Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton and The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series on Founders Online, and the Library of Congress, Hathitrust, and the Internet Archive. This was a lot of fun to put together and I can not wait to include fictionalizations of all this chaos in TAI (literally, 20-something chapters are dedicated to this) hehehe....

Because context is king, here is a rundown of the important events that led to Alexander Hamilton receiving his appointment as captain:

Preceding Appointment - 1775:

February 23rd: The Farmer Refuted, &c. is first published in James Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer. The publication was preceded by two announcements, and is a follow up to a string of pamphlet debate between Hamilton and Samuel Seabury that had started in the fall of 1774. The Farmer Refuted would have wide-reaching effects.

April 19th: Battles of Lexington and Concord — The first shots of the American War for Independence are fired in Lexington, Massachusetts, and soon followed by fighting in Concord, Massachusetts.

April 23rd: News of Lexington and Concord first reaches New York. [x] According to his friend Nicholas Fish in a later letter, "immediately after the battle of Lexington," Hamilton "attached himself to one of the uniform Companies of Militia then forming for the defense of the Country by the patriotic young men of this city." It is most likely that Hamilton enlisted in late April or May of 1775, and a later record of June shows that Hamilton had joined the Corsicans (later named the Hearts of Oak), alongside Nicholas Fish and Robert Troup (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 127; for Fish's letter, Newton cites a letter from Fish to Timothy Pickering, dated December 26, 1823 within the Timothy Pickering Papers of the Massachusetts Historical Society).

June 14th: Within weeks of his enlistment, Hamilton's name appears within a list of men from the regiments throughout New York that were recommended to be promoted as officers if a Provencal Company should be raised (pp. 194-5, Historical Magazine, Vol 7).

June 15th: Congress, seated in Philadelphia, establishes the Continental Army. George Washington is unanimously nominated and accepts the post of Commander-in-Chief. [x]

Also on June 15th: Alexander Hamilton’s Remarks On the Quebec Bill: Part One is published in James Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer.

June 22nd: The Quebec Bill: Part Two is published in James Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer.

June 25th: On their way to Boston, General Washington and his generals make a short stop in New York City. The Provincial Congress orders Colonel John Lasher to "send one company of the militia to Powle's Hook to meet the Generals" and that Lasher "have another company at this side (of) the ferry for the same purpose; that he have the residue of his battalion ready to receive" Washington and his men. There is no confirmation that Alexander Hamilton was present at this welcoming parade, however it is likely, due to the fact that the Corsicans were apart of John Lasher's battalion. [x]

Also on June 25th: According to a diary entry by one Ewald Shewkirk, a dinner reception was held in Washington's honor. It is unknown if Hamilton was present at this dinner, however there is no evidence to suggest he could not have been (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 129; Newton cites Johnston, Henry P. The Campaigns of 1776 around New York and Brooklyn, Vol. 2, pg. 103).

August 23-24th: According to his friend Hercules Mulligan decades later in his “Narrative” (being a biographical sketch, reprinted in the William & Mary Quarterly alongside a “Narrative” and letters from Robert Troup), Hamilton and himself took part in a raid upon the city's Battery with a group composed of the Corsicans and some others. They managed to haul off a good number of the cannons down in the city Battery. However, the Asia, a ship in the harbor, soon sent a barge and later came in range of the raiding party itself, firing upon them. According to Mulligan, “Hamilton at the first firing [when the barge appeared with a small gun-crew] was away with the Cannon.” Mulligan had been pulling this cannon, when Hamilton approached and asked Mulligan to take his musket for him, taking the cannon in exchange. Mulligan, out of fear left Hamilton’s musket at the Battery after retreating. Upon Hamilton’s return they crossed paths again and Hamilton asked for his musket. Being told where it had been left in the fray, “he went for it, notwithstanding the firing continued, with as much unconcern as if the vessel had not been there.”

September 14th: The Hearts of Oak first appear in the city records. [x] Within the list of officers, Fredrick Jay (John Jay’s younger brother), is listed as the 1st Lieutenant, and also appears in a record of August 9th as the 2nd Lieutenant of the Corsicans. This, alongside John C. Hamilton’s claims regarding Hamilton’s early service, has left historians to conclude that either the Corsicans reorganized into the Hearts of Oak (this more likely), or members of the Corsicans later joined the Hearts of Oak.

December 4th: In a letter to Brigadier General Alexander McDougall, John Jay writes “Be so kind as to give the enclosed to young Hamilton.” This enclosure was presumably a reply to Hamilton’s letter of November 26th (in which he raised concern for an attack upon James Rivington’s printing shop), however Jay’s reply has not been found.

December 8th: Again in a letter to McDougall, Jay mentions Hamilton: “I hope Mr. Hamilton continues busy, I have not recd. Holts paper these 3 months & therefore cannot Judge of the Progress he makes.” What this progress is, or anything written by Hamilton in John Holt’s N. Y. Journal during this period has not been definitively confirmed, leaving historians to argue over possible pieces written by Hamilton.

December 31st: Hamilton replies to Jay’s letter that McDougall likely gave him around the 14th [x]. Comparing the letters Hamilton sent in November and December I will likely save for a different post, but their differences are interesting; more so with Jay’s reply having not been found.

These mentionings of Hamilton between Jay and McDougall would become important in the next two months when, in January of 1776, the New York Provincial Congress authorized the creation of a provincial company of artillery. In the coming weeks, Hamilton would see a lot of things changing around him.

Hamilton Takes Command - 1776:

February 23rd: During a meeting of the Provincial Congress, Alexander McDougall recommends Hamilton for captain of this new artillery company, James Moore as Captain-Lieutenant (i.e: second-in-command), and Martin Johnston for 1st Lieutenant. [x]

February-March: According to Hercules Mulligan, again in his “Narrative”, "a Commission as a Capt. of Artillery was promised to" Alexander Hamilton "on the Condition that he should raise thirty men. I went with him that very afternoon and we engaged 25 men." While it is accurate that Hamilton was responsible for raising his company, as acknowledged by the New York Provincial Congress [later renamed] on August 9th 1776, Mulligan's account here is messy. Mulligan misdates this promise, and it may not have been realistic that they convinced twenty-five men to join the company in one afternoon. Nevertheless, Mulligan could have reasonably helped Hamilton recruit men between the time he was nominated for captancy and received his commission.

March 5th: Alexander Hamilton opens an account with Alsop Hunt and James Hunt to supply his company with "Buckskin breeches." The account would run through October 11th of 1776, and the final receipt would not be received until 1785, as can be seen in Hamilton's 1782-1791 cash book.

March 10th: Anticipating his appointment, Hamilton purchases fabrics and other materials for the making of uniforms from a Thomas Garider and Lieutenant James Moore. The materials included “blue Strouds [wool broadcloth]”, “long Ells for lining,” “blue Shalloon,” and thread and buttons. [x]

Hamilton later recorded in March of 1784 within his 1782-1791 cash book that he had “paid Mr. Thompson Taylor [sic: tailor] by Mr Chaloner on my [account] for making Cloaths for the said company.” This payment is listed as “34.13.9” The next entry in the cash book notes that Hamilton paid “6. 8.7” for the “ballance of Alsop Hunt and James Hunts account for leather Breeches supplied the company ⅌ Rects [per receipts].” [x]

Following is a depiction of Hamilton’s company uniform!

First up is an illustration of an officer (not Hamilton himself) as seen in An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Uniforms of The American War For Independence, 1775-1783 Smith, Digby; Kiley, Kevin F. pg. 121. By the list of supplies purchased above, this would seem to be the most accurate depiction of the general uniform.

Here is another done in 1923 of Alexander Hamilton in his company's uniform:

March 14th: The New York Provincial Congress orders that "Alexander Hamilton be, and he is hereby, appointed captain of the Provincial company of artillery of this Colony.” Alongside Hamilton, James Gilleland (alternatively spelt Gilliland) is appointed to be his 2nd Lieutenant. “As soon as his company was raised, he proceeded with indefatigable pains, to perfect it in every branch of discipline and duty,” Robert Troup recalled in a later letter to John Mason in 1820 (reprinted alongside Mulligan’s recollections in the William & Mary Quarterly), “and it was not long before it was esteemed the most beautiful model of discipline in the whole army.”

March 24th: Within a pay roll from "first March to first April, 1776," Hamilton records that Lewis Ryan, a matross (who assisted the gunners in loading, firing, and spounging the cannons), was dismissed from the company "For being subject to Fits." Also on this pay roll, it is seen that John Bane is listed as Hamilton's 3rd Lieutenant, and James Henry, Thomas Thompson, and Samuel Smith as sergeants.

March 26th: William I. Gilbert, also a matross, is dismissed from the company, "for misbehavior." [x]

March-April: At some point between March and April of 1776, Alexander Hamilton drops out of King's College to put full focus towards his new duties as an artillery captain. King's College would shut down in April as the war came to New York City, and the building would be occupied by American (and later British) forces. Hamilton would never go back to complete his college degree.

April 2nd: The Provincial Congress having decided that the company who were assigned to guard the colony's records had "been found a very expensive Colony charge" orders that Hamilton "be directed to place and keep a proper guard of his company at the Records, until further order..." (Also see the PAH) According to historian Willard Sterne Randall in an article for the Smithsonian Magazine, the records were to be "shipped by wagon from New York’s City Hall to the abandoned Greenwich Village estate of Loyalist William Bayard." [x]

Not-so-fun fact: it is likely that this is the same Bayard estate that Alexander Hamilton would spend his dying hours inside after his duel with Aaron Burr 28 years later.

April 4th: Hamilton writes a letter to Colonel Alexander McDougall acknowledging the payment of "one hundred and seventy two pounds, three shillings and five pence half penny, for the pay of the Commissioned, Non commissioned officers and privates of [his] company to the first instant, for which [he has] given three other receipts." This letter is also printed at the bottom of Hamilton’s pay roll for March and April of 1776.

April 10th: In a letter of the previous day [April 9th] from General Israel Putnam addressed to the Chairmen of the New York Committee of Safety, which was read aloud during the meeting of the New York Provincial Congress, Putnam informs the Congress that he desires another company to keep guard of the colony records, stating that "Capt. H. G. Livingston's company of fusileers will relieve the company of artillery to-morrow morning [April 10th, this date], ten o'clock." Thusly, Hamilton was relieved of this duty.

April 20th: A table appears in the George Washington Papers within the Library of Congress titled "A Return of the Company of Artillery commanded by Alexander Hamilton April 20th, 1776." The Library of Congress itself lists this manuscript as an "Artillery Company Report." The Papers of Alexander Hamilton editors calendar this table and describe the return as "in the form of a table showing the number of each rank present and fit for duty, sick, on furlough, on command duty, or taken as prisoner." [x]

The table, as seen above, shows that by this time, Hamilton’s company consisted of 69 men. Reading down the table of returns, it is seen that three matrosses are marked as “Sick [and] Present” and one matross is noted to be “Sick [and] absent,” and two bombarders and one gunner are marked as being “On Command [duty].” Most interestingly, in the row marked “Prisoners,” there are three sergeants, one corporal, and one matross listed.

Also on April 20th: Alexander Hamilton appears in General George Washington's General Orders of this date for the first time. Washington wrote that sergeants James Henry and Samuel Smith, Corporal John McKenny, and Richard Taylor (who was a matross) were "tried at a late General Court Martial whereof Col. stark was President for “Mutiny"...." The Court found both Henry and McKenny guilty, and sentenced both men to be lowered in rank, with Henry losing a month's pay, and McKenny being imprisoned for two weeks. As for Smith and Taylor, they were simply sentenced for disobedience, but were to be "reprimanded by the Captain, at the head of the company." Washington approved of the Court's decision, but further ordered that James Henry and John McKenny "be stripped and discharged [from] the Company, and [that] the sentence of the Court martial, upon serjt Smith, and Richd Taylor, to be executed to morrow morning at Guard mounting." As these numbers nearly line up with the return table shown above, it is clear that the table was written in reference to these events. What actions these men took in committing their "Mutiny" are unclear.

May 8th: In Washington's General Orders of this date, another of Hamilton's men, John Reling, is written to have been court martialed "for “Desertion,” [and] is found guilty of breaking from his confinement, and sentenced to be confin’d for six-days, upon bread and water." Washington approved of the Court's decision.

May 10th: In his General Orders of this date, General Washington recorded that "Joseph Child of the New-York Train of Artillery" was "tried at a late General Court Martial whereof Col. Huntington was President for “defrauding Christopher Stetson of a dollar, also for drinking Damnation to all Whigs, and Sons of Liberty, and for profane cursing and swearing”...." The Court found Child guilty of these charges, and "do sentence him to be drum’d out of the army." Although Hamilton was not explicitly mentioned, his company was commonly referred to as the "New York Train of Artillery" and Joseph Child is shown to have enlisted in Hamilton's company on March 28th. [x]

May 11th: In his General Orders of this date, General Washington orders that "The Regiment and Company of Artillery, to be quarter’d in the Barracks of the upper and lower Batteries, and in the Barracks near the Laboratory" which would of course include Alexander Hamilton's company. and that "As soon as the Guns are placed in the Batteries to which they are appointed, the Colonel of Artillery, will detach the proper number of officers and men, to manage them...." Where exactly Hamilton and his men were staying prior to this is unclear.

May 15th: Hamilton appears by name once more in General George Washington’s General Orders of this date. Hamilton’s artillery company is ordered “to be mustered [for a parade/demonstration] at Ten o’Clock, next Sunday morning, upon the Common, near the Laboratory.”

May 16th: In General Washington's General Orders of this date, it is written that "Uriah Chamberlain of Capt. Hamilton’s Company of Artillery," was recently court martialed, "whereof Colonel Huntington was president for “Desertion”—The Court find the prisoner guilty of the charge, and do sentence him to receive Thirty nine Lashes, on the bare back, for said offence." Washington approved of this sentence, and orders "it to be put in execution, on Saturday morning next, at guard mounting."

May 18th: Presumably, Hamilton carried out the orders given by Washington in his General Orders of May 16th, and on the morning of this date oversaw the lashing of Uriah Chamberlain at "the guard mounting."

May 19th: At 10 a.m., Hamilton and his men gathered at the Common (a large green space within the city which is now City Hall Park) to parade before Washington and some of his generals as had been ordered in Washington's General Orders of May 15th. In his Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene (on page 57), William Johnson in 1822 recounted that, (presumably around or about this event):

It was soon after Greene's arrival on Long Island, and during his command at that post, that he became acquainted with the late General Hamilton, afterwards so conspicuous in the councils of this country. It was his custom when summoned to attend the commander in chief, to walk, when accompanied by one or more of his aids, from the ferry landing to head-quarters. On one of these occasions, when passing by the place then called the park, now enclosed by the railing of the City-Hall, and which was then the parade ground of the militia corps, Hamilton was observed disciplining a juvenile corps of artillerist, who, like himself, aspired to future usefulness. Greene knew not who he was, but his attention was riveted by the vivacity of his motion, the ardour of his countenance, and not less by the proficiency and precision of movement of his little corps. Halt behind the crowd until an interval of rest afforded an opportunity, an aid was dispatched to Hamilton with a compliment from General Greene upon the proficiency of his corps and the military manner of their commander, with a request to favor him with his company to dinner on a specified day. Those who are acquainted with the ardent character and grateful feelings of Hamilton will judge how this message was received. The attention never forgotten, and not many years elapsed before an opportunity occurred and was joyfully embraced by Hamilton of exhibiting his gratitude and esteem for the man whose discerning eye had at so early a period done justice to his talents and pretensions. Greene soon made an opportunity of introducing his young acquaintance to the commander in chief, and from his first introduction Washington "marked him as his own."

Michael E. Newton notes that William Johnson never produced a citation for this tale, and goes on to give a brief historiography of it (Johnson being the first to write about this). While it is possible that General Greene could have sent an aide-de-camp to give his compliments to Hamilton after seeing his parade drill, there is no certain evidence to suggest that Greene introduced Hamilton to George Washington. Newton also notes that "John C. Hamilton failed to endorse any part of the story." (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pp. 150-152).

May 26th: Alexander Hamilton writes a letter to the New York Provincial Congress concerning the pay of his men. Hamilton points out that his men are not being paid as they should be in accordance to rules past, and states that “They do the same duty with the other companies and think themselves entitled to the same pay. They have been already comparing accounts and many marks of discontent have lately appeared on this score.” Hamilton further points out that another company, led by Captain Sebastian Bauman, were being paid accordingly and were able to more easily recruit men.

Also on May 26th: the Provencal Congress approved Hamilton’s request, resolving that Hamilton and his men would receive the same pay as the Continental artillery, and that for every man he recruited, Hamilton would receive 10 shillings. [x]

May 31st: Captain Hamilton receives orders from the Provincial Congress that he, “or any or either of his officers," are "authorized to go on board any ship or vessel in this harbour, and take with them such guard as may be necessary, and that they make strict search for any men who may have deserted from Captain Hamilton’s company.” These orders were given after "one member informed the Congress that some of Captain Hamilton’s company of artillery have deserted, and that he has some reasons to suspect that they are on board of the Continental ship, or vessel, in this harbour, under the command of Capt. Kennedy." Unfortunately, I as of writing this have been unable to find any solid information on this Captain Kennedy to better identify him, or his vessel.

June 8th: The New York Provincial Congress orders that Hamilton "furnish such a guard as may be necessary to guard the Provincial gunpowder" and that if Hamilton "should stand in need of any tents for that purpose" Colonel Curtenius would provide them. It is unknown when Hamilton's company was relieved of this duty, however three weeks later, on June 30th, the Provincial Congress "Ordered, That all the lead, powder, and other military stores" within the "city of New York be forthwith removed from thence to White Plains." [x]

Also on June 8th: the Provincial Congress further orders that "Capt. Hamilton furnish daily six of his best cartridge makers to work and assist" at the "store or elaboratory [sic] under the care of Mr. Norwood, the Commissary."

June 10th: Besides the portion of Hamilton's company that was still guarding the colony's gunpowder, it is seen in a report by Henry Knox (reprinted in Force, Peter. American Archives, 4th Series, vol. VI, pg. 920) that another portion of the company was stationed at Fort George near the Battery, in sole command of four 32-pound cannons, and another two 12-pound cannons. Simultaneously, another portion of Hamilton's company was stationed just below at the Grand Battery, where the companies of Captain Pierce, Captain Burbeck, and part of Captain Bauman's manned an assortment of cannons and mortars.

June 17th: The New York Provincial Congress resolves that "Capt. Hamilton's company of artillery be considered so many and a part of the quota of militia to be raised for furnished by the city or county of New-York."

June 29th: A return table, reprinted in Force, Peter's American Archives, 4th Series, vol. VI, pg. 1122 showcases that Alexander Hamilton's company has risen to 99 men. Eight of Hamilton's men--one bombarder, two gunners, one drummer, and four matrosses--are marked as being "Sick [but] present." One sergeant is marked as "Sick [and] absent" and two matrosses are marked as "Prisoners."

July 4th: In Philadelphia, the Continental Congress approves the Declaration of Independence.

July 9th: The Continental Army gathers in the New York City Common to hear the Declaration read aloud from City Hall. In all the excitement, a group of soldiers and the Sons of Liberty (who included Hercules Mulligan) rushed down to the Bowling Green to tear down an equestrian statue of King George III, which they would melt into musket balls. For a history of the statue, see this article from the Journal of the American Revolution.

Also on July 9th: the New York Provincial Congress approve the Declaration of Independence, and hereafter refer to themselves as the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York. [x]

July 12th: Multiple accounts record that the British ships Phoenix and Rose are sailing up the Hudson River, near the Battery, when as Hercules Mulligan stated in a later recollection, "Capt. Hamilton went on the Battery with his Company and his piece of artillery and commenced a Brisk fire upon the Phoenix and Rose then passing up the river. When his Cannon burst and killed two of his men who I distinctly recollect were buried in the Bowling Green." Mulligan's number of deaths may be incorrect however. Isac Bangs records in his journal that, "by the carelessness of our own Artilery Men Six Men were killed with our own Cannon, & several others very badly wounded." Bangs noted further that "It is said that several of the Company out of which they were killed were drunk, & neglected to Spunge, Worm, & stop the Vent, and the Cartridges took fire while they were raming them down." In a letter to his wife, General Henry Knox wrote that "We had a loud cannonade, but could not stop [the Phoenix and Rose], though I believe we damaged them much. They kept over on the Jersey side too far from our batteries. I was so unfortunate as to lose six men by accidents, and a number wounded." Matching up with Bangs and Knox, in his own journal, Lieutenant Solomon Nash records that, "we had six men cilled [sic: killed], three wound By our Cannons which went off Exedently [sic: accidentally]...." A William Douglass of Connecticut wrote to his wife on July 20th that they suffered "the loss of 4 men in loading [the] Cannon." (as seen in Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pg. 142; Newton cites Henry P. Johnston's The Campaigns of 1776 in and around New York and Brooklyn, vol. 2, pg. 67). As these accounts cobberrate each other, it is clear that at least six men were killed. Whether these were all due to Hamilton's cannon exploding is unclear, but is a possibility. Hamilton of course was not punished for this, but that is besides the point.

One of the men injured by the explosion of the cannon was William Douglass, a matross in Hamilton's company (not to be confused with the William Douglass quoted above from Connecticut). According to a later certificate written by Hamilton on September 14th, Douglass "faithfully served as a matross in my company till he lost his arm by an unfortunate accident, while engaged in firing at some of the enemy’s ships." The Papers of Alexander Hamilton editors date Douglass' injury to June 12th, but it is clear that this occurred on July 12th due to the description Hamilton provides.

July 26th: Hamilton writes a letter to the Convention of the Representatives (who he mistakenly addresses as the "The Honoruable The Provincial Congress") concerning the amount of provisions for his company. He explains that there is a difference in the supply of rations between what the Continental Army and Provisional Army and his company are receiving. He writes that "it seems Mr. Curtenius can not afford to supply us with more than his contract stipulates, which by comparison, you will perceive is considerably less than the forementioned rate. My men, you are sensible, are by their articles, entitled to the same subsistence with the Continental troops; and it would be to them an insupportable discrimination, as well as a breach of the terms of their enlistment, to give them almost a third less provisions than the whole army besides receives." Hamilton requests that the Convention "readily put this matter upon a proper footing." He also notes that previously his men had been receiving their full pay, however under an assumption by Peter Curtenius that he "should have a farther consideration for the extraordinary supply."

July 31st: The Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York read Hamilton's letter of July 26th at their meeting, and order that "as Capt. Hamilton's company was formally made a part of General Scott's brigade, that they be henceforth supplied provisions as part of that Brigade."

A Note On Captain Hamilton’s August Pay Book:

Starting in August of 1776, Hamilton began to keep another pay book. It is evident by Thomas Thompson being marked as the 3rd lieutenant that this was started around August 15th. The cover is below:

For unknown reasons, the editors of The Papers of Alexander Hamilton only included one section of the artillery pay book in their transcriptions, being a dozen or so pages of notes Hamilton wrote presumably after concluding his time as a captain on some books he was reading. The first section of the book (being the first 117 image scans per the Library of Congress) consists of payments made to and by Hamilton’s men, each receiving his own page spread, with the first few pages being a list of all men in the company as of August 1776, organized by surname alphabetically. The last section of the pay book (Image scans 181 to 185) consists of weekly company return tables starting in October of 1776.

As these sections are not transcribed, I will be including the image scans when necessary for full transparency, in case I have read something incorrectly. Now, back to the timeline....

August 3rd: John Davis and James Lilly desert from Hamilton's company. Hamilton puts out an advertisement that would reward anyone who could either "bring them to Captain Hamilton's Quarters" or "give Information that they may be apprehended." It is presumed that Hamilton wrote this notice himself (see Newton, Michael E. Alexander Hamilton: The Formative Years, pp. 147-148; for the notice, Newton cites The New-York Gazette; and the weekly Mercury, August 5, 12, and September 2nd, 1776 issues).

August 9th: The Convention of the Representatives resolve that "The company of artillery formally raised by Capt. Hamilton" is "considered as a part of the number ordered to be raised by the Continental Congress from the militia of this State, and therefore" Hamilton's company "hereby is incorporated into Genl. Scott's brigade." Here, Hamilton would be reunited with his old friend, Nicholas Fish, who had recently been appointed as John Scott's brigade major. [x]

August 12th: Captain Hamilton writes a letter to the Convention of the Representatives concerning a vacancy in his company. Hamilton explains that this is due to “the promotion of Lieutenant Johnson to a captaincy in one of the row-gallies, (which command, however, he has since resigned, for a very particular reason.).” He requests that his first sergeant, Thomas Thompson, be promoted as he “has discharged his duty in his present station with uncommon fidelity, assiduity and expertness. He is a very good disciplinarian, possesses the advantage of having seen a good deal of service in Germany; has a tolerable share of common sense, and is well calculated not to disgrace the rank of an officer and gentleman.…” Hamilton also requested that lieutenants James Gilleland and John Bean be moved up in rank to fill the missing spots.

August 14th: The Convention of the Representatives, upon receiving Hamilton’s letter of August 12th, order that Colonel Peter R. Livingston, "call upon [meet with] Capt. Hamilton, and inquire into this matter and report back to the House."

August 15th: Colonel Peter R. Livingston reports back to the Convention of the Representatives that, "the facts stated by Capt. Hamilton are correct..." The Convention thus resolves that "Thomas Thompson be promoted to the rank of a lieutenant in the said company; and that this Convention will exert themselves in promoting, from time to time, such privates and non-commissioned officers in the service of this State, as shall distinguish themselves...." The Convention further orders that these resolutions be published in the newspapers.

August ???: According to Hercules Mulligan in his "Narrative" account, Alexander Hamilton, along with John Mason, "Mr. Rhinelander" and Robert Troup, were at the Mulligan home for dinner. Here, Mulligan writes that, after Rhineland and Troup had "retired from the table" Hamilton and Mason were "lamenting the situation of the army on Long Island and suggesting the best plans for its removal," whereupon Mason and Hamilton decided it would be best to write "an anonymous letter to Genl. Washington pointing out their ideas of the best means to draw off the Army." Mulligan writes that he personally "saw Mr. H [Hamilton] writing the letter & heard it read after it was finished. It was delivered to me to be handed to one of the family of the General and I gave it to Col. Webb [Samuel Blachley Webb] then an aid de Champ [sic: aide-de-camp]...." Mulligan expresses that he had "no doubt he delivered it because my impression at that time was that the mode of drawing off the army which was adopted was nearly the same as that pointed out in the letter." There is no other source to contradict or challenge Hercules Mulligan's first-hand account of this event, however the letter discussed has not been found.

August 24th: Alexander Hamilton helped to prevent Lieutenant Colonel Herman Zedwitz from committing treason. On August 25th, a court martial was held (reprinted in Force, Peter. American Archives, 5th Series, vol. I, pp. 1159-1161) wherein Zedwitz was charged with "holding a treacherous correspondence with, and giving intelligence to, the enemies of the United States." In a written disposition for the trial, Augustus Stein tells the Court that on the previous day [this date, August 24th] Zedwitz had given him a letter with which Stein was directed "to go to Long-Island with [the] letter [addressed] to Governour Tryon...." Stein, however, wrote that he immediately went "to Captain Bowman's house, and broke the letter open and read it. Soon after. Captain Bowman came in, and I told him I had something to communicate to the General. We sent to Captain Hamilton, and he went to the General's, to whom the letter was delivered." By other instances in this court martial record, it is clear that Stein had meant Captain Sebastian Bauman (and to this, Zedwitz's name is also spelled many different times throughout this record), which would indicate that the "Captain Hamilton" mentioned was Alexander Hamilton, Bauman's fellow artillery captain. Bauman was the only captain serving by that name in the army at this time (see Heitman, Francis B. Historical Register of the Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution, pg. 92). It could be possible that Alexander Hamilton personally delivered this letter into Washington's hands and explained the situation, or that he passed it on to one of Washington's staff members.

August 27th: Battle of Long Island — Although Alexander Hamilton was not involved in this battle, for no primary accounts explicitly place him in the middle of this conflict, it is significant to note considering the previous entry on this timeline.

May-August: According to Robert Troup, again in his 1821 letter to John Mason, he had paid Hamilton a visit during the summer of 1776, but did not provide a specific date. Troup noted that, “at night, and in the morning, he [Hamilton] went to prayer in his usual mode. Soon after this visit we were parted by our respective duties in the Army, and we did not meet again before 1779.” This date however, may be inaccurate, for also according to Troup in another letter reprinted later in the William & Mary Quarterly, they had met again while Hamilton was in Albany to negotiate the movement of troops with General Horatio Gates in 1777.

September 7th: In his General Orders of this date, General Washington writes that John Davis, a member of Alexander Hamilton's company who had deserted in early August, was recently "tried by a Court Martial whereof Col. Malcom was President, was convicted of “Desertion” and sentenced to receive Thirty-nine lashes." Washington approved of this sentence, and ordered that it be carried out "on the regimental parade, at the usual hour in the morning."

September 8th: In his General Orders of this date, Washington writes that John Little, a member of "Col. Knox’s Regt of Artillery, [and] Capt. Hamilton’s Company," was tried at a recent court martial, and convicted of “Abusing Adjt Henly, and striking him”—ordered to receive Thirty-nine lashes...." Washington approved of this sentence, and ordered it, along with the other court martial sentences noted in these orders, to be "put in execution at the usual time & place."

September 14th: Hamilton writes a certificate to the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York regarding his matross, William Douglass, who “lost his arm by an unfortunate accident, while engaged in firing at some of the enemy’s ships” on July 12th. Hamilton recommends that a recent resolve of the Continental Congress be heeded regarding “all persons disabled in the service of the United States.”

September 15th: On this date, the Continental Army evacuated New York City for Harlem Heights as the British sought control of the city. According to the Memoirs of Aaron Burr, vol. 1, General Sullivan’s brigade had been left in the city due to miscommunication, and were “conducted by General Knox to a small fort” which was Fort Bunker Hill. Burr, then a Major and aide-de-camp to General Israel Putman, was directed with the assistance of a few dragoons “to pick up the stragglers,” inside the fort. Being that Knox was in command of the Army’s artillery, Hamilton’s company would be among those still at the fort. Major Burr and General Knox then had a brief debate (Knox wishing to continue the fight whereas Burr wished to help the brigade retreat to safety). Aaron Burr at last remarked that Fort Bunker Hill “was not bomb-proof; that it was destitute of water; and that he could take it with a single howitzer; and then, addressing himself to the men, said, that if they remained there, one half of them would be killed or wounded, and the other half hung, like dogs, before night; but, if they would place themselves under his command, he would conduct them in safety to Harlem.” (See pages 100-101). Corroborating this account are multiple certificates and letters from eyewitnesses of this event reprinted in the Memiors on pages 101-106. In a letter, Nathaniel Judson recounted that, “I was near Colonel Burr when he had the dispute with General Knox, who said it was madness to think of retreating, as we should meet the whole British army. Colonel Burr did not address himself to the men, but to the officers, who had most of them gathered around to hear what passed, as we considered ourselves as lost.” Judson also remarked that during the retreat to Harlem Heights, the brigade had “several brushes with small parties of the enemy. Colonel Burr was foremost and most active where there was danger, and his con-duct, without considering his extreme youth, was afterwards a constant subject of praise, and admiration, and gratitude.”

Alexander Hamilton himself recounted in later testimony for Major General Benedict Arnold’s court martial of 1779 that he “was among the last of our army that left the city; the enemy was then on our right flank, between us and the main body of our army.” Hamilton also recalled that upon passing the home of a Mr. Seagrove, the man left the group he was entertaining and “came up to me with strong appearances of anxiety in his looks, informed me that the enemy had landed at Harlaam, and were pushing across the island, advised us to keep as much to the left as possible, to avoid being intercepted….” Hercules Mulligan also recounted in his “Narrative” printed in the William & Mary Quarterly that Hamilton had “brought up the rear of our army,” and unfortunately lost “his baggage and one of his Cannon which broke down.”

September 28th: In his General Orders of this date, Washington wrote that William Higgins of Hamilton’s artillery was “convinced by a General Court Martial” where “Col. Weedon is President” for the crime of “‘plundering and stealing’.” Higgins was “ordered to be whipped Thirty-nine lashes.” Although this noted court martial is written in the present tense, the editors of The George Washington Papers reveal in the second note of the document that Higgins was “convicted the previous day [September 27th] for having “‘[broken] open a Chest & stealing a Number of Articles out of it in a Room of the Provost Guard’” as was written in the court marrial’s proceedings, which can be found in the Library of Congress’ George Washington Papers.

September ???: As can be seen in Hamilton's August 1776-May 1777 pay book, while stationed in Harlem Heights (often abbreviated as "HH" in the pay book), nearly all of Hamilton's men received some sort of item, whether this be shoes, cash payments, or other articles.

October 4th: A return table for this date appears in Alexander Hamilton’s pay book, in the back. These return tables are not included in The Papers of Alexander Hamilton for unknown reasons.

The table, as seen above, provides us a snapshot of Hamilton’s company at this time, as no other information survives about the company during October. His company totaled to 49 men. Going down the table, two matrosses were “Sick [and] Present,” one bombarder, four gunners, and six matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] absent,” and two matrosses were marked as “On Furlough.” Interestingly, another two matrosses were marked as having deserted, and two matrosses were marked as “Prisoners.”

October 11th: In Hamilton’s pay book, below the table of October 4th, another weekly return table appears with this date marked.

The return table, as seen above, again records that Hamilton’s company consisted of 49 men. Reading down the table, two matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] Present,” one bombarder and four matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] absent,” and one captain-lieutenant [being James Moore], one sergeant, and two matrosses were marked as being “On Furlough.”

To the right of the date header, in place of the usual list of positions, there is a note inside the box. The note likely reads:

Drivers. 2_ Drafts_l?] 9_ 4 of which went over in order to get pay & Cloaths & was detained in their Regt [regiment]

Drafts were men who were drawn away from their regular unit to aid another, and it’s clear that Hamilton had many men drafted into his company. This note tells us that four of these men were sent by Hamilton to gather clothing for the company, and it is likely that they had to return to their original regiment before they could return the clothing. This, at least, makes the most sense (a huge thank you to @my-deer-friend and everyone else who helped me decipher this)!! In the bottom left-hand corner of the page, another note is present, however I am unable to decipher what it reads. If anyone is able, feel free to take a shot!

October 25th: Another weekly returns table appears in Hamilton’s company pay book. Once more, this table of returns was not transcribed within The Papers of Alexander Hamilton.

The table, as seen above, shows that Hamilton’s company still consisted of 49 men. Reading down the table, it can be seen that one matross and one drummer/fifer were “Sick [but] present,” and one sergeant, two bombarders, one gunner, and four matrosses were marked as “Sick [and] absent.” Interestingly, one matross was noted as being “Absent without care”. Two matrosses were listed as “Prisoners” and again two matrosses were listed as having “Deserted.”

Underneath the table, a note is written for which I am only able to make out part. It is clear that two men from another captain’s company were drafted by Hamilton for his needs.

October 28th: Battle of White Plains — Like with Long Island, there is no primary evidence to explicitly place Alexander Hamilton, his men, or his artillery as being involved in this battle, contrary to popular belief. See this quartet of articles by Harry Schenawolf from the Revolutionary War Journal.

November 6th: Captain Hamilton wrote another certificate to the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York regarding his matross, William Douglass, who was injured during the attacks on July 12th. This certificate is nearly identical to the one of September 14th, and again Hamilton writes that Douglass is “intitled to the provision made by a late resolve of the Continental Congress, for those disabled in defence of American liberty.”

November 22nd: As can be seen in Hamilton's pay book, all of his men regardless of rank received payments of cash, and some men articles, on this date.

December 1st: Stationed near New Brunswick, New Jersey, General Washington wrote in a report to the President of Congress, that the British had formed along the Heights, opposite New Bunswick on the Raritan River, and notably that, "We had a smart canonade whilst we were parading our Men...." Alexander Hamilton's company pay book placed he and his men at New Brunswick in around this time (see image scans 25, 28, 34, and others) making it likely that Hamilton had been present and helped prevent the British from crossing the river while the Continental Army was still on the opposite side. In his Memoirs of My Own Life, vol. 1, James Wilkinson recorded that:

After two days halt at Newark, Lord Cornwallis on the 30th November advanced upon Brunswick, and ar- Dec. 1. rived the next evening on the opposite bank of the Rariton, which is fordable at low water. A spirited cannonade ensued across the river, in which our battery was served by Captain Alexander Hamilton,* but the effects on eitlierside, as is usual in contests between field batteries only, were inconsiderable. Genei'al Washington made a shew of resistance, but after night fall decamped...

Though Wilkinson was not present at this event, John C. Hamilton similarly recorded in both his Life of Alexander Hamilton [x] and History of the Republic [x] that Hamilton was part of the artillery firing the cannonade during this event. Though there is no firsthand account of Hamilton's presence here, it is highly likely that he and his company was involved in holding off the British so that the Continental Army could retreat.

December 4th?: Either on this date, or close to it, Alexander Hamilton’s second lieutenant, James Gilleland, left the company by resigning his commission to General Washington on account of “domestic inconveniences, and other motives,” according to a later letter Hamilton wrote on March 6th of 1777.

December 5th: Another return table appears in the George Washington Papers within the Library of Congress. This table is headed, "Return of the States of part of two Companeys of artilery Commanded by Col Henery Knox & Capt Drury & Capt Lt Moores of Capt Hamiltons Com." The Papers of Alexander Hamilton editors calendar this table, and note that Hamilton's "company had been assigned at first to General John Scott’s brigade but was soon transferred to the command of Colonel Henry Knox." They also note that the table "is in the writing of and signed by Jotham Drury...." [x]

The table, as seen above, notes part of the "Troop Strength" (as the Library of Congress notes) of Captain Jotham Drury and Captain Alexander Hamilton's men. As regards Hamilton's company, the portion that was recorded here amounted to 33 men.

December 19th: Within his Warrent Book No. 2, General George Washington wrote on this date a payment “To Capn Alexr Hamilton” for himself and his company of artillery, “from 1st Sepr to 1 Decr—1562 [dollars].” As reprinted within The Papers of Alexander Hamilton.

December 25th: Within Bucks County, Pennsylvania, hours before the famous Christmas Day crossing of the Delaware River by Washington and the Continental Army, Captain-Lieutenant James Moore passed away from a "short but excruciating fit of illness..." as Hamilton would later recount in a letter of March 6th, 1777. According to Washington Crossing Historic Park, Moore has been the only identified veteran to have been buried on the grounds during the winter encampment. His original headstone read: "To the Memory of Cap. James Moore of the New York Artillery Son of Benjamin & Cornelia Moore of New York He died Decm. the 25th A.D. 1776 Aged 24 Years & Eight Months." [x] In his aforementioned letter, Alexander Hamilton remarked that Moore was "a promising officer, and who did credit to the state he belonged to...." As Hamilton and Moore spent the majority of their time physically together (and therefore leaving no reason for there to be surviving correspondence between the two), there is no clear idea of what their working relationship may have looked like.