#Not the least of which is in terms of etymology

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Annotated Sandman #22–Season of Mists, Chapter 1

This chapter gets a lot of annotations from Leslie Klinger, so I've tried to select a few for our community reread.

Hell in all its forms...

NG sets the scene in the script: "We're looking at Hell, or at least a portion of it. Now, for this initial shot I want to move as far away from the current interpretation of Hell as possible — no twisted geometries, no flames everywhere, no giant maggots and heads on pikes, all that stuff. Let's look instead at what hell means to us: for me, it's concentration camps — endless, bleak camps of fat, jerry-rigged buildings, 'shower rooms' which are gas chambers, huge ovens for burning the bodies: Hell is living there, Hell for me is knowing that one day you'll go for your shower, Hell is really knowing what's going on in Auschwitz, or Dachau, or Belsen, but pretending to yourself that you don't, because that makes it easier to get through the following day. That's part of Hell.

Hell is factories, and industrial waste, air you can't breathe and water you can't drink. Hell is walking past the Port of New York Authority building on a hot day and watching two men with dead eyes stealing a handful of pennies from a third, who sits on the sidewalk and silently cries as the first two divide their loot. That's the kind of Hell we're looking at here. It's a long shot, but somewhere below us there should be a number of terribly thin, naked people, standing up to their knees in mud. There's no sun in the sky, and the horizon is muggy and smoggy, composed of factory chimneys, belching smog and ash into the air."

Avernus, a crater west of Naples, Italy, was thought to be an entrance to the underworld; later, the name became synonymous with the underworld.

Gehenna was an actual place, the valley of Hinnom near Jerusalem, where the city's refuse was dumped and incin-erated. According to ancient legends, sacrifices of children to Moloch took place in the valley; other legends associating Gehenna with a burning afterworld of hellfire claimed that an actual gate to that world stood in the valley.

Hades was the god and ruler of the Greek underworld, the son of Cronus and Rhea. When Cronus was over-thrown, the dominion of the world was divided among Hades (Pluton) and his other sons, Zeus and Poseidon, by lot; Hades took control of the darkness of night and the underworld. As tradition developed, the name Pluto became attached to the god and the name Hades to his domain. Hades was surrounded by five rivers, Styx, Acheron, Pyriphlegethon, Cocytus, and Lethe. In Greek mythology Tartarus was a region beneath Hades, into which originally only those who were a threat to the gods were cast. Other mythologies made it synonymous.

Abaddon, literally the "place of destruction" in Hebrew, was associated with Sheol and later identified as a region of Gehenna.

Sheol was originally a Hebrew term for the grave, the place into which all of the dead traveled to await resurrection. The New Testament, however, generally differentiated between Sheol and Gehenna, with the latter the place of abode of sinners.

Demons

"Demon" is a Greek word of confused etymology.

The Greek philosophers saw demons as intermediate between gods and men. Initially, religions of the world distinguished nature-spirits such as elves and nymphs, concerned with living men and their affairs, from the demons, often considered to be ghosts of dead men. According to the Encyclopadia Britannica (9th Ed.), the earliest notion of demons included "the whole class of such spirits, who may be friendly or hostile, good or evil, persecuting and tormenting man or acting as protecting and informing patron-spirits..." While Christian theology introduced a narrower definition, merging "good" demons with angels and leaving the term "demon" applicable only to evil spirits or devils, "the study of demonology also brings into view the tendency of hostile religions to degrade into evil demons the deities of rival faiths."

What's going on with all these authors and their books?

In an interview, NG confesses that he probably unconsciously took the idea of a library of ideal books from James Branch Cabell's Beyond Life. (SC, p. 98).

Psmith and Jeeves by P.G. Wodehouse. Rupert (or Ronald Eustace) Psmith was a roguish former Etonian whose adventures were recorded in three novels by British humorist P.G. Wodehouse between 1908 and 1910, with a final adventure published in 1923. Reginald jeeves, created in 1915 by Wodehouse, was a gentleman's gentleman, who frequently saved his employer Bertie Wooster from humorously complex situations. Although Psmith and jeeves never met, Wodehousians dream of the day when their unknown adventures together might be discovered.

Love Can Be Murder by Raymond Chandler. The theme of love drawing people into violent situations was common to virtually all of Chandler's classic Philip Marlowe mysteries, The theme is especially prominent in Farewell, My Lovely (1940), in which Moose Malloy attempts to track down "his" Velma, the woman he left behind on entering prison eight years earlier. At his death in 1959, Chandler left four chapters of an unfinished novel entitled The Poodle Springs Story, which mystery writer Robert B. Parker completed in 1989 under the title Poodle Springs.

The Dark God's Darlings by Lord Dunsany. Dunsany (1878-1957), one of the neglected fantasists of the 20th century, was a prolific writer whose dark tales influenced several generations of writers, including H.P. Lovecraft, Arthur C. Glarke, Gene Wolfe, and Neil Gaiman. In the late 1990s, the curator of Dunsany's castle discovered a number of previously unpublished works; this one has not yet been published.

The Hand of Glory by Erasmus Fry. Fry appears in Issue #17, and little is known of his work. A "hand of glory" is a magical artifact, the dried and preserved hand of a hanged man (usually the left), said to bring great luck to the owner or provide a variety of other magical powers. Fry apparently had an affinity for such objects.

The Return of Edwin Drood by Charles Dickens. The Mystery of Edwin Drood is one of Charles Dickens's most famous novels, partly because it is tantalizingly incomplete due to Dickens's untimely death. Numerous other writers have proposed their own solutions or conclusions to the tale; Dickens's own version would be a great treasure.

The Conscience of Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle. A strange title — does this refer to Dr. Watson, who from time to time speaks to Holmes as if he is the latter's inner voice? NG remarks in an interview that this is a book he thought should have been written but wasn't, a conscience being "the one thing that Holmes didn't have." (SC, p. 98)

Poictesme Babylon by James Branch Cabell. Fantasist Cabell (1879-1958) is best-known for Jurgen, A Comedy of Justice (1919). The eponymous hero journeys through fantastic realms, where he beds numerous women. He even visits Hell, where he seduces the Devil's wife. Jurgen was part of a saga of Cabell's creation, comprising 25 books, which he referred to as the "biography of Manuel," a swincherd who eventually ruled the fictional province of Poictesme, in southern France. Presumably this lost book would have continued the adventures of jurgen and characters from Cabell's other works.

The Man Who Was October by G.K. Chesterton. The title is a play on Chesterton's The Man Who Was Thursday (1908), a seminal fantastic work presaging Orwell's 1984 and Huxley's Brave New World and mixing political thought with Christian allegory. We may suppose that Chesterton intended a sequel to the original book. "Thursday" was a code name for the principal character; in Chesterton's mind, he may have envisioned another secret organization with equally fanciful names. A quote from the book appears at 28.24.4.

The Lost Road by J.R.R. Tolkien. This title was added by letterer Todd Klein. Tolkien's epic tales of elves, men, dwarves, and orcs, written in the 1930s and 1940s, gained an immense audience in the 1960s with mass-market editions and seem to grow in popularity annually. After his death in 1973, his son Christopher Tolkien published a number of unfinished works of his father. A fragment of "The Lost Road," apparently written in 1937 or 1938, was published in 1987 as part of The Lost Road and Other Writings. It arose out of a conversation between fellow Inklings J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis about the state of contemporary fiction. Tolkien later wrote in a letter: "We agreed that he should try 'space-travel, and I should try 'time-travel? His result is well known (the Perelandra trilogyl. My effort, after a few promising chapters, ran dry." The tale describes a "road" that connects different eras of history, some of Tolkien's invention, some based on historical evidence.

Alice's Journey Behind the Moon by Lewis Carroll. To the delight of millions of readers, Carroll (1832-1898) famously wrote Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Behind the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871). While he wrote numerous other books, poems, and essays, none achieved the success of these two. However, art imitates art: In 2004, R.J. Carter published a wholly original work entitled Alice's Journey Beyond the Moon in which Carter related the adventures of Carroll's Alice in space. NG remarked in his blog that this was the first book to escape the Library of Dream into the real world.

The following were listed in the script but didn't appear in the published version:

Cthulhu Springtime by H.P. Lovecraft. Lovecraft was the greatest writer of horror in the 20th century, as well as the first serious scholar of the genre, and Cthulhu is the chief of his Old Ones, godlike beings who have vanished from Earth. The book must have been intended to tell of their return. The title is reminiscent of the brilliantly bad musical Springtime for Hitler, produced by Mel Brooks's The Producers (1968).

Lord Greystoke of Barsoom by Edgar Rice Burroughs.Tarzan meets john Carter et al. One can only imagine the adventure! Carter was featured in only three of Burroughs's novels, while Lord Greystoke appeared in twenty-three. NG also reveals in an interview that the library's collection encompasses other media, such as film, art, and music, including among its movies "all the stories Orson Welles made in his head but could never get the financing to film." (SC, p. 99)

Lucifer

Samael is a name for Lucifer, the prince of devils, in early Jewish commentary. Literally, it means "venom of God," and many scholars see this etymology as cementing his identification with the angel of death. However, the name may have derived from the Syrian god Shemal.

More about Matthew…

[I wrote about Matthew’s story and his first meeting with Dream in a bit more detail here]

In his mortal life as Matthew Cable, Matthew crashes his car while going after his wife Abby to straighten out matters with her, killing himself. However, a demon in the form of a fly agrees to revive him. This resurrection permits Anton Arcane, a ruthless soul pursuing a vendetta against the Swamp Thing, to escape from Hell and possess Cable's body, attaining his powers (see Vol. 1, 15.23.5). Although Matthew eventually triumphs over Arcane, there is significant collateral damage, including the molestation of Matthew's wife Abby. See Saga of the Swamp Thing, Vol. 2, #26-31 (jul.-Dec. 1984).

Lyta's weird pregnancy led to continuity errors…

Hippolyta's father is Steve Trevor [I wrote about Lyta’s messy pre- and post-crisis DC history briefly here]. See Vol. 1, 11.5.5. NG comments in the script for Issue #40 about the age of the child: "Actually that's the one continuity slip in the whole of Sandman — Daniel's age. Theoretically he should have been born about 3 months after the end of 'The Doll's House, in about February or March of 1990... Even if Lyta's metabolism took a while to get back into sync again, she still should have had the baby in spring. Trouble was he had to be newborn in Sandman #22, so I could do the stuff about his naming.

"I suppose if anyone asks, it's sort of fudgeable: Time in dreams is slightly iffy, and more to the point, time in Hell is extremely iffy — the only real honest-to-goodness date given in "Season of Mists" was that the dead came back in December '90. But it irritates me. Everything else works just fine. I suppose if anyone ever asks me I'll just have to admit that I don't understand it either..."

Why Daniel?

In an interview, NG states that the boy's name "connects to the Daniel in the Bible who has visions and interprets dreams." (SC, p. 101) Of course, ultimately he will have no name. See Vol. 4, 72.19.6, when he denies that he is Daniel.

The Toast

There are no extant tasting notes for the 1828 Chateau Lafitte. Michael Broadbent, in his New Great Vintage Wine Book (1991) notes a five-star rating for the 1825 vintage based on his tasting in 1975. The négociant Nicolas recorded a 5 franc price for the original bottling.

Hob's toast appears to be original. The most famous reference to the "season of mists" is in John Keats's To Autumn (1820):

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss'd cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For summer has o'er-brimm'd their clammy cells.

[That’s just the first stanza btw, you can find the rest here]

#the sandman#sandman#dream of the endless#morpheus#hob gadling#the sandman comics#matthew the raven#lyta hall#daniel hall#lucifer morningstar#Lucien the librarian#matthew cable#steve trevor#sandman comics reread#leslie klinger#season of mists#queue crew

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Having a moderate worldbuilding naming crisis now that I'm trying to figure out how old the first use of the word 'track' to refer to continuous tracks is

#Oh fuck oh shit this could be... Tricky#You see dear reader I have been hiding a certain very big piece of information about the 12 Worlds from you all#And it is a piece of information that has continuously fucked with me in so many ways#Not the least of which is in terms of etymology#In short for this case: there's a reason I refer to 'tanks' as 'armtracks'#But depending on how early the 'track' part of that was used in our own history to refer to that sort of device#I might be facing a... Significant problem

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here's a tabletop RPG history question, and also an etymology question if your nerdery bends that way.

d66 tables – as in "roll a six-sided die twice, reading the first roll as the 'tens' place and the second roll as the 'ones' place, yielding a number in the range from 11 to 66" – have been around at least as early as 1977, when the Starships book for classic Traveller used them to randomly generate trade goods for players to buy. However, the term "d66" wasn't yet being used to describe them – the book's text simply describes in detail how to roll on them each time such a table appears.

Conversely, we know the term "d66" was being used to describe this type of random lookup table no later than 2004, because several popular Japanese indie RPGs which came out in that year use it. However, none of these games seem to have originated it – the way they're using it suggests they're dropping a piece of jargon that was already well established at the time.

So the question is: what's the earliest tabletop RPG that specifically uses the term "d66" or "d66 table" to describe this type of random lookup roll? i.e., not "d6/d6" or "d6,d6" or any alternative verbiage, but "d66" specifically? It has to have been published in or before 2004, and (probably) not earlier than 1977. No speculation about which games might have used it, please; if you're going to suggest a candidate, be prepared to cite a specific title and page number.

3K notes

·

View notes

Note

Since you are an expert on vampires (at least well informed and properly presenting sources), I wanted to ask if it made sense for the term "vampire" to exist in the middle ages, specifically the first half of the 13th century. I'm asking because I'm playing in the VtM setting of Dark Ages, which is canonically set in the year 1242 and I was wondering about that

Thank you for the question! Hopefully I can provide a good response (although remember this information is a grand generalization and sources are linked for you to look deeper)

Okay so for a little backstory of the word vampire - There is not a decided 'canon' for it's etymological origins but a few linguists have delved into it's theories, such as Franz Miklosich (or; Franc Miklošič). He, in his work “Etymologie der Slavischen Sprach” theorized that the slavic synonyms ‘Upior’, ‘Uper’ and ‘Upyr’, are all stemmed from the Tatar Turkic word for witch- ‘uber/ubyr’. Montague Summers states in his book 'The Vampire: His Kith and Kin' -

The most wildly accepted form of the word's origins are however from the Serbian word Bamiiup- Miklosich also relays that this word could be a 'transmittor'

Essentially, a lot of different words went through a lot of different variations and translations as the myth of the unread blood-sucker spread over the greater European continent as well as reached it's way across the sea to the Americas. But most importantly - the word vampire wasn't properly dissected the way it is being in more modern times and it wasn't until the 18th-century that variations of the word 'vampyr/vampyre/vampir/vampire' were used wildly.

Katharina M. Wilson states in 'The History of the Word "Vampires"' (a massive and great source used in many other articles on entomology, I mean seriously I encountered her being used as reference multiple times) "In sum, the earliest recorded uses of the term "vampire" appear in French, English, and Latin, and they refer to vampirism in Poland, Russia, and Ma- cedonia (Southern Yugoslavia). The second and more sweeping introduction of the word occurs in German, French, and English, and records the Serbian vampire epidemic of 1725-32."

The word 'vampire' (written as vampyre), while these vampire epidemics were at their height in Europe, was first seen in English in 1732 actually and began then to be more widely used, here is a 1734 book by Michael Ranft that has it in it's title!

To put a long explanation short, the word vampire was not used in the medieval ages. But other words that signal to us modern folk that certain creatures were vampires were definitely used, all because of the Christian Church.

So during the medieval times, instead of vampire it was a minion of the devil, a revenant, a ghost, an undead, some sinning spirit or corpse. Vampire's weren't internationally associated with drinking blood until later publications of literature, they were more like zombies and spirits who consumed people's life essence or came after them in their undeath, and the soul sucking would sometimes be accompanied by blood sucking, since blood was an integral part of a person's body not just medically but in the sense of religion and what distinguished a human from a demon.

While the word was not use the appearance and disposition of of these creatures was very much what we can tell is the tall-tale sign of the vampire myth solidifying. "The Vampire Myth and Christianity" by Dorothy Ivey uses the book 'Medieval Folklore: A Guide to Myths, Legends, Tales, Beliefs, and Customs' by Carl Lindahl, John McNamara and John Lindow (tried to find the book online myself but no luck so I'm quoting Ivey quoting Lindahl and others) as a source and writes “a revenant, reanimated corpse, or phantom of the recently deceased, which maintains its former, living appearance when it comes out of the grave at night to drink the blood of humans.” and further more “lack of decomposition or rigor mortis, pallid face, sharp protruding canine teeth." the book further describes the traits of a vampire having to return to it's coffin at daybreak and that a person is turned vampire by consuming the creatures blood/being bitten. (remember, me and sources/refs are using the word vampire for convenience, not because it was said or written, they were still creatures/spirits/satan's spawn)

Important to note, the Bubonic Plague raged across Europe from 1346 to 1353, the number of corpses and diseased were so plentiful that a lot of bodies were dumped in shallow graves and given in-proper burials, which spiked the myth of them coming back as vampires. It didn't help that the disabled/impaired were viewed horribly during these times. People who were sick from old age, diseases and chronic conditions were treated with the same disgust and repulsion and those who were seen as 'wrong' in the eye of the Church. The vampire myth was an excellently awful tool used by the medieval Church to further their own agenda and power. Ivey writes it perfectly:

So - demons, revenants, spirits, sinners, undead, sick/disabled people, improperly buried corpses etc were core parts of this 'evil'. An example I remember from this work also hones in on the 'improper' buriel aspects that would turn a person into a vampire. People who were aforded proper christian burials were pious god-fearing folk, those who followed the Churchs rulings and therefore were buried in a Church graveyard. People who were given improper funerals were whose who had sinned, were not christian, were, as discussed above, disabled, 'wrong', had committed suicide etc and therefore were not buried in Church ground and therefore were more likely to come back as demons lackeys and revenants.

The idea of a vampire had widely existed though, from the Greek Vrykolakas to the Nordic Draugr, but in summery, the word vampire did not exist as we know it back during the Medival ages.

And lastly, I feel like this writing by Gemma Hollman in 'Medieval Vampires' summarize the vampire situation during those times quite well

Hope you found this blabbering useful!

Sources:

Justhistoryposts, V. a. P. B. (2024, December 18). Medieval Vampires. Just History Posts. https://justhistoryposts.com/2016/11/01/medieval-vampires/

Matczak, M., Kozłowski, T., & Chudziak, W. (2022). multidisciplinary study of anti-vampire burials from early medieval Culmen, Poland: were the diseased and disabled regarded as vampires? Archaeologia Historica Polona, 29. https://doi.org/10.12775/ahp.2021.012

Ivey, D. (2010). The Vampire Myth and Christianity. Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1015&context=mls

Wilson, Katharina M. “The History of the Word ‘Vampire.’” Journal of the History of Ideas, vol. 46, no. 4, 1985, pp. 577–83. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2709546. Accessed 29 May 2025.

Summers, M. (1929). The Vampire: his Kith and Kin. Notes and Queries, 156(6), 107. https://doi.org/10.1093/nq/156.6.107b

Mutch, D. (2012). The modern vampire and human identity. In Palgrave Macmillan UK eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230370142

Frayling, C. (1991). Vampyres : Lord Byron to Count Dracula. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA14229568

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you were an a-spec exclusionist (or even "neutral") in the 2010s on Tumblr, if you remember laughing at "cringe aces," and have since come around to realize "hey that was kinda shitty, obviously aces and aros are queer," then you've obviously taken a huge step forward. But if you haven't actually evaluated what subtler forms of aphobia look like, and unlearned those too, then you absolutely need to do that, or else internalized biases will persist in this community that make a-specs feel unsafe.

The most rampant and insidious type of aphobia on Tumblr in the past few years hasn't been about explicitly saying you hate/want to exclude asexuals. Aphobes themselves say they've moved on from "discourse blogs," now preferring to make superficially "normal" posts with subtle aphobic dogwhistles, and people who don't consider themselves "exclusionists" still pass those dogwhistle posts around! And sometimes, "subtle" is giving the aphobes way too much credit, because a-spec terminology and microlabels are still constantly mocked, and used as punchlines.

Below, I've linked a variety of posts about what aphobia looks like, what commonly misunderstood/mocked a-spec terminology really means, and how a-spec people differ from common stereotypes and misconceptions. I don't expect everyone to read every one of these posts. There are some long ones. But I know Tumblr would be a significantly less hostile experience for a-spec people if everyone unlearning aphobia looked at, and reflected critically about, at least a few.

Subtle Aphobia; A-Specs and Sex Positivity

[Plain text: "Subtle Aphobia, Aces and Sex Positivity."]

Sex Repulsion Vs. Sex Negativity - Know the Difference

“Anti-Sex” and the Real Sexual Politics of the Right (Spoiler alert: religious purity culture is not "anti-sex." Rather, it's actually opposed to sexual autonomy.)

Acephobia and Ableism, Queer Social Spaces "Discourse"

Common Modern Aphobia, Critical Thinking Questions About "Cringe" Ace Posts on the Dashboard

"Virgin" as an insult just perpetuates sex negativity

Tumblr polls as harassment bait

Hey, What Do Those Terms We Mocked Actually Mean?

[PT: "Hey, What Do Those Terms We Mocked Actually Mean?"]

Origin, Use, and Etymology of "Allosexual"

Why "Queerplatonic" Doesn't Have a Set Definition, and Why That Matters (from the actual people who coined it!)

"Queerplatonic is to relationships what nonbinary is to gender"

"Amatonormativity" as Defined by Dr. Elizabeth Brake

Amatonormativity Affects More Than Just Aces and Aros

On mocking people's labels — "I want to limit your ability to communicate"

Masterpost of A-Spec Readings

Aromantic Allosexuals (Yes, Including Men)

[PT: "Aromantic Allosexuals (Yes, Including Men)"]

"Aroallos are often treated as inherently "more sexual" than other allosexuals. Here's why that assumption happens, and why it's bullshit."

Romantic Attraction Is Not Required To Respect Women

You can't support aroallos without unlearning sex negativity

Further Readings on Aphobia

[PT: "Further Readings on Aphobia"]

The problems with "Asterisk Acceptance"

"Aces are Valid" doesn't cut it

Compulsory Sexuality Is An Issue For Everyone

When sex-positivity in fandom swerves into compulsory sexuality and othering aces. (This is the only "fandom"-adjacent post I'm linking, but doing so because 1. I know the demographics of this site, and 2. this post is so well-put that its point is generalizable to non-fandom topics too.)

Aphobia Was Bad, It Was Bigotry, It Was Part of the TERF Pipeline

Bi person discusses parallels between aphobia and other queerphobia

Bi and trans person discusses parallels between aphobia and other queerphobia

Asexual Women of Color Navigating White Patriarchy

"Trauma is not a factor by which queerness should be measured" - excerpt from Refusing Compulsory Sexuality, and related discussion

Arophobia: "You say you accept aromanticism, but..."

A-Spec Experiences Growing Up in Purity Culture Religions

"The World is Not Made For Single People"

Asexual Theory Masterpost

506 notes

·

View notes

Text

Knock on Wood

To knock on wood is a superstitious action undertaken to try to influence a good outcome when "tempting fate"... but it's also euphemistic for sex involving a penis.

The wood part of that euphemism is obvious... The knock part comes from to knock being slang for to have sex with someone from at least the mid-1500s, with one term for a brothel being a "knocking shop" well into the 1800s. To knock was sometimes also used in the past to mean to verbally ask someone for sex... whereas the wordplay-happy Crowley was humorously choosing to do that, in this case, by literally knocking on the bench in the above scene.

It's these things that make this scene a funny visual pun on knock on wood wherein Crowley knocks on the wood of the bench and Aziraphale, immediately upon hearing the sound, looks down at his cock. 😂

They say the ducks are so used to being fed by secret agents that they've developed Pavlovian reactions to them. *giggles*

The wood knocked on in this scene was a bench-- something they're often sitting on together and something which, based on Aziraphale's response, Crowley's likely knocked on before, especially because of how the etymology of bench can convey a request for a specific variety of knocking on wood. What variety? Well, bench has retained its original meaning from its predecessor, the Old English benc, which meant, as you might figure it would...

... long seat. 😉 Crowley knocking on the bench they're sitting on to see if he can knock on wood and ride his lengthy bench later on, after-- and for-- lunch.

#good omens#ineffable husbands#aziraphale#crowley#aziracrow#good omens meta#ineffable husbands speak

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Dialogue: Happy Expressions

to describe your characters

Happy as a clam - Cute as they are, clams are not the most emotive creatures in the animal kingdom, so why do we say happy as a clam? Some have speculated it’s because a partially opened clam shell resembles a smile. But the expression is a shortening of the longer happy as a clam in mud at high tide or happy as a clam at high water, both of which were in usage by the mid-1800s and serve to mean “happy as a critter that’s safe from being dug up and eaten.” The longer expressions evoke a sense of relief more than the shorter happy as a clam, which is widely used to mean “extremely happy.”

Happy camper - A person who is cheerful and satisfied, although the expression is frequently used in negative constructions, as in “I’m not a happy camper.” The word camper was widely used to refer to a soldier or military man when it entered English in the 1600s. It took on a more generic sense of one who camps recreationally in the mid-1800s, paving the way for the expression happy camper to emerge in the 1930s. Interestingly, use of the phrase happy camper skyrocketed in the 1980s.

Happy-go-lucky - The word happy comes from the Old Norse happ meaning “chance” or “luck.” The wildcard nature of chance is reflected in the wide range of words that share this root. While the adjective happy-go-lucky, meaning “trusting cheerfully to luck” or “happily unconcerned or worried,” is widely used in positive contexts, its etymological cousin haphazard, carries a more negative connotation. The expression happy-be-lucky entered English slightly earlier than happy-go-lucky, but fell out of use in the mid-1800s.

Happy hour - People were using the word happy to mean “intoxicated” as early as the mid-1600s, alluding to the merrymaking effect of alcohol. But the phrase happy hour didn’t catch on until the early 1900s. This expression originally referred to a time on board a ship allotted for recreation and entertainment for a ship’s crew. Nowadays the expression refers to cocktail hour at a bar, when drinks are served at reduced prices. This definition caught on around the era depicted in the well-lubricated offices of TV’s Mad Men.

Happy medium - The phrase happy medium refers to a satisfactory compromise between two opposed things, or a course of action that is between two extremes. The notion of the happy medium is descended from an ancient mathematical concept called the golden section, or golden mean, in which the ratios of the different parts of a divided line are the same. This term dates from the 1600s, though it is still widely used today.

Slaphappy - Around the time of World War II, the word happy began appearing in words to convey temporary overexcitement. Slaphappy is one of these constructions, suggesting a dazed or “happy” state from repeated blows or slaps, literal or figurative. Slaphappy can mean “severely befuddled” or “agreeably giddy or foolish” or “cheerfully irresponsible.”

Trigger-happy - The happy in trigger-happy indicates a kind of temporary mental overstimulation. But in this construction, happy means “behaving in an irresponsible or obsessive manner.” The term trigger-happy entered English in the 1940s with the definition “ready to fire a gun at the least provocation.” Over time, it has taken on figurative senses including “eager to point out the mistakes or shortcomings of others” and “heedless and foolhardy in matters of great importance.”

Source ⚜ More: Notes ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs ⚜ Some Personality Idioms

#writing reference#langblr#writeblr#character development#literature#writers on tumblr#dark academia#writing prompt#spilled ink#creative writing#dialogue#happy#poets on tumblr#expressions#words#characterization#writing inspiration#writing ideas#light academia#lit#writing resources

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: Cookies stuffed with fruit and nuts and topped with glaze, sprinkles, and candied orange peel. End ID]

Cucciddati (Sicilian cookies with dates and figs)

This Sicilian fig cookie was one of my great-grandmother's Christmas specialties. Crisp, buttery shortbread surrounds a rich, sweet filling of figs, dates, raisins, nuts, citrus, and spices, and the whole cookie is then topped with an orange juice glaze. The result is a complex, decadent, festive dessert that is also quite pretty. My great-grandmother always used rainbow sprinkles on hers, but you can also go for nonpareils, citrus zest, or candied citrus peel.

Time and place

Sicily is broadly known for having different sweets in different regions that are strongly identified with particular holidays: each village has its own patron saint with its own feast, and its own special sweet. Cucciddati are eaten throughout all of Sicily during Christmastime, but they are perhaps particularly associated with Palermo and Calatafimi. Usually the first cucciddatu of the season is eaten at the l'Immacolata (Feast of the Immaculate Conception), on December 8th.

Cucciddati are (like most foods) a mix of various regional influences that reflect the history of their birthplace. North African culinary influence on Sicily dates back at least to the Islamic conquest of the island from the 9th to the 11th centuries AD: citrus, almonds, and dried figs are prominent examples of it. Cucciddati may also have been influenced by "buccellati di Lucca"—ring-shaped loaves of bread studded with raisin and anise—that were brought from Lucca (in Tuscany, Italy) to Palermo along with a group of merchants who immigrated in the 14th century.

However the ancestors of modern cucciddati came together, some of their ingredients must certainly have been introduced after this time. The chocolate in the filling could not have been added before Spanish colonization in the Americas.

Language and history

These cookies are known as "buccellati" (singular "buccellato") in Italian, or as "cucciddati" (singular "cucciddatu") in Sicilian. Either word may also refer to a ring-shaped loaf of bread, a ring cake with a similar filling, or, indeed, any pastry with a hole in the center. The word "buccellato" comes from the Latin “buccellatum”, meaning "soldiers' biscuit" or "hardtack." One speculative etymology derives "buccellato" from the Italian "braccialetto," or "bracelet"; but this seems less likely.

The term "cucciddati" originally referred to ring-shaped loaves of bread that were divided and handed or thrown out into the crowd during Sicilian festivals, such as the festival of San Giuseppe in Palermo, or the Festa del Crocifisso (Feast of the Holy Cross) in Calatafimi. In centuries past, these loaves were so large that they were carried looped around one shoulder, like a rope: but, in modern festivals, they are much smaller. These loaves might be plain or, as one 1875 text indicates, flavored with seeds including anise and sesame.

Biblioteca delle tradizioni popolari siciliane (1900) describes the throwing of the bread at the Festa del Crocifisso in Calatafimi:

Entering from the Palermo gate, [the procession] is made up of farmers, all on superb, saddled mules, adorned in the most beautiful ways. Each of them has a large candle with the usual ribbons, and two buccellati laid on it from above so that they rest on the farmer's hand. They proceed in pairs, but the last grouping is of three: two of them each carrying a little horse of wood or cardboard; the other, the one in the middle, a little cow, also of wood or cardboard. Great is the delight that the people take in the sight of them: but they take even greater delight in the so-called carrozza (carriage), a cart covered in laurel and covered with buccellati, at the top of which is a beautiful and auspicious handful of ears of corn [...]. It is pulled along the road by four pairs of oxen covered in flowers and ribbons, and farmers stand on it, who never tire of breaking the loaves one at a time and throwing the pieces up to the people on the balconies and windows and down to the crowd; and everyone eagerly tries to eat it, like blessed bread. (translation mine)

The book also quotes a popular Sicilian-language song, in which the villagers hail the cart, with its presents of bread:

'Scìu la carrozza, chi già Iu sapiti, Era càrrica assai di cucciddati, China di li burgisi tutti uniti, Jittannu pani pi li strati strati The carriage comes out, and you already know it It was all full of buccellati Full of the burgisi all united (Who were going) throwing bread in the streets. (A "burgisi" is "one who rents the lands of others; a rich or well-off peasant.")

It is not said that any of these loaves had a fig filling, and I would assume they did not. Figs do appear in association with cucciddati in an 1892 article on Palermo in Natura ed Arte: it mentions "a’ buccellati di uva passa e fichi" (Italian), also known as "cucciddati di passuli e ficu" (Sicilian)—that is, "cucciddati with raisins and figs." They are listed as an example of festive bread or folk sweets ("pane [...] festivo"; "dolci e delle ghiottornie popolari"), as opposed to everyday bread ("pane quotidiano"). There is no mention, however, of the cucciddati being thrown during festivals.

I suspect that these words ("buccellato" and "cucciddatu") came to refer to a fig-filled pastry, as well as a plain ring of bread, through this process: the words first meant "a ring of bread"; for this reason, they came to be associated with any ring-shaped pastry; a pastry (whether cake or cookie) which was shaped like a cucciddatu, but with an additional filling of dried fruit, was referred to as a type of cucciddatu ("cucciddati di passuli e ficu"); and, eventually, this phrase was shortened to just "cucciddati."

Today, cucciddati may retain this ring shape, but they may also be cut into individual portions (as pictured above).

Recipe under the cut!

Patreon | Paypal | Venmo

Makes 24 cookies.

For the dough:

1 cup (120g) all-purpose flour

1/4 cup (100g) granulated sugar

1 tsp baking powder

1 tsp baker's ammonia (optional)

Pinch table salt

1/4 cup (1/2 stick) vegetable shortening or non-dairy margarine, softened

1 Tbsp neutral oil

2 Tbsp cup soy or oat milk, or as needed

1 tsp vanilla extract

For the filling:

1/2 cup dried figs

1/4 cup dried dates, pitted

1/4 cup raisins

Peel of 1 mandarin

1/4 cup almonds, toasted and chopped

1/4 cup walnuts, toasted and chopped

2 Tbsp zuccata (cucuzza squash jam); or substitute marmalade or apricot jam

2 Tbsp dark chocolate chips (optional)

1 Tbsp brandy

1 stick cassia cinnamon, toasted and ground

4 whole cloves, toasted and ground

Small chunk nutmeg, toasted and ground

Some recipes include a greater variety of nuts. You may also use an equal amount of almonds, walnuts, pistachios, and filberts or hazelnuts.

Use 1 Tbsp orange blossom water, or a few drops of fiori di sicilia, instead of brandy for a halal version.

For the icing:

1/2 cup vegetarian powdered sugar, sifted

1/4 tsp vanilla

2 tsp orange juice

To top:

Sprinkles, or candied lemon or orange peel.

Instructions

For the dough:

Whisk dry ingredients together in a large bowl.

Add shortening or margarine and oil and mix to combine.

Add vanilla. Add milk slowly while mixing until everything comes together into a soft, non-sticky dough. The dough should not crack when pressed.

Cover and allow to rest while you prepare the filling.

For the filling:

Toast nuts in a large, dry skillet on medium heat until fragrant and a shade darker.

Toast spices in a dry skillet on medium-low until fragrant. Grind in a mortar and pestle, or with a spice mill. Sieve to remove large pieces.

Mix all filling ingredients in a food processor or meat grinder, and process to desired texture.

To shape:

Divide dough into four equal pieces and leave the ones you're not working with covered.

Roll out dough on a piece of wax or parchment paper into a rectangle of about 5" x 10" (13 x 25cm).

Take 1/4 of the filling and roll it against your work surface until you have a cylinder of the same length as the dough.

Place the filling along the dough lengthwise, then use the parchment paper to roll the dough tightly over the filling. Press the seam to seal, then place the log of filled dough seam-side-down.

Cut the log into 6 equal portions. Repeat with the remaining pieces of filling.

Bake cookies for 12-15 minutes in a 190 °C (375 °F) oven, until they are golden brown on the bottom and around the edges.

For the icing:

Mix all ingredients in a small bowl and whisk to combine.

Dipped cooled cookies into the icing. Top with sprinkles or other toppings, as desired.

92 notes

·

View notes

Note

This might seem like a strange question at first, but in your interpretation, what makes a monster a monster in Greek mythology?

I used to think that gods and heroes represented order and civilization, while monsters symbolized chaos and savagery. However, many monsters are either used by or beloved by the gods. For instance, Karkinos is placed in the sky as a constellation by Hera, Artemis sends the Erymanthian Boar to punish a king, the sea monster Herakles slays on Troy was sent by Poseidon, the Harpies are referred to as the "hounds of almighty Zeus" by Apollonius and punish mortals on his behalf, Cerberus guards the Underworld, Hera sends a dragon to protect her golden fruits in the Garden of the Hesperides, and the Ismenian Dragon, killed by Cadmus, guards Ares' spring and is even referred to as his child by Pseudo-Apollodorus. Notably, Poseidon attempts to avenge his son, Polyphemus, in the Odyssey.

So, for example, how different is the fear of Zeus' thunderbolt—representing divine punishment—from the fear of Zeus' Harpies, which would be monsters?

Here is an interesting excerpt from the introduction to The Oxford Handbook of Monsters in Classical Myth:

"Some ancient cultures had no specific terminology for things we might consider monstrous, but instead encompassed them under the general concept of ‘spirits’—not humans, not gods, but something in between; … But for Greece and Rome, a partial clue to the ancient conception of ‘monster’ around the Mediterranean comes through the language they used to signify such beings, as many other chapters in this volume indicate. The Greek term teras referred both to portents from the gods and, in a more concrete sense, a physical monstrosity, something deformed; hence our modern term ‘teratology’, which refers not only to mythologies about marvellous, unusual, and inhuman physical creatures, but also to the scientific study of congenital abnormalities. The English word ‘monster’ itself comes from the Latin monstrum, etymologically linked with the verbs monere (‘to warn’) and monstrare (‘to show’). A monstrum, to the Romans, originally denoted any manifestation of divine will that breached ‘the natural order, provoking awe or at least shock’, but eventually came to be the closest thing to a regular Latin term for any physically anomalous being (see Lowe 2015: 8–9). So, for the purposes of this volume, readers will find that ‘monster’ refers to a variety of creatures, most of them exhibiting physical anomalies such as an excess or deficit of limbs, unusually large size, and/or jarring hybridity, and all of them, in some way or another, transgressing literal or metaphorical boundaries. Often their main purposes in the stories are to act as disruptive agents, though such disruption may come only when they find their status as guardians threatened. At a minimum, these creatures prove unsettling in their unexpectedness; at a maximum, they pose dire threats to humans and human attempts to settle into and impose order on the natural world."

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

The most important deity you've never heard of: the 3000 years long history of Nanaya

Being a major deity is not necessarily a guarantee of being remembered. Nanaya survived for longer than any other Mesopotamian deity, spread further away from her original home than any of her peers, and even briefly competed with both Buddha and Jesus for relevance. At the same time, even in scholarship she is often treated as unworthy of study. She has no popculture presence save for an atrocious, ill-informed SCP story which can’t get the most basic details right. Her claims to fame include starring in fairly explicit love poetry and appearing where nobody would expect her. Therefore, she is the ideal topic to discuss on this blog. This is actually the longest article I published here, the culmination of over two years of research. By now, the overwhelming majority of Nanaya-related articles on wikipedia are my work, and what you can find under the cut is essentially a synthesis of what I have learned while getting there. I hope you will enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed working on it. Under the cut, you will learn everything there is to know about Nanaya: her origin, character, connections with other Mesopotamian deities, her role in literature, her cult centers… Since her history does not end with cuneiform, naturally the later text corpora - Aramaic, Bactrian, Sogdian and even Chinese - are discussed too. The article concludes with a short explanation why I see the study of Nanaya as crucial.

Dubious origins and scribal wordplays: from na-na to Nanaya Long ago Samuel Noah Kramer said that “history begins in Sumer”. While the core sentiment was not wrong in many regards, in this case it might actually begin in Akkad, specifically in Gasur, close to modern Kirkuk. The oldest possible attestation of Nanaya are personal names from this city with the element na-na, dated roughly to the reign of Naram-Sin of Akkad, so to around 2250 BCE. It’s not marked in the way names of deities in personal names would usually be, but this would not be an isolated case.

The evidence is ultimately mixed. On one hand, reduplicated names like Nana are not unusual in early Akkadian sources, and -ya can plausibly be explained as a hypocoristic suffix. On the other hand, there is not much evidence for Nanaya being worshiped specifically in the far northeast of Mesopotamia in other periods. Yet another issue is that there is seemingly no root nan- in Akkadian, at least in any attested words.

The main competing proposal is that Nanaya originally arose as a hypostasis of Inanna but eventually split off through metaphorical mitosis, like a few other goddesses did, for example Annunitum. This is not entirely implausible either, but ultimately direct evidence is lacking, and when Nanaya pops up for the first time in history she is clearly a distinct goddess.

There are a few other proposals regarding Nanaya’s origin, but they are considerably weaker. Elamite has the promising term nan, “day” or “morning”, but Nanaya is entirely absent from the Old Elamite sources you’d expect to find her in if Mesopotamians imported her from the east. Therefore, very few authors adhere to this view. The hypothesis that she was an Aramaic goddess in origin does not really work chronologically, since Aramaic is not attested in the third millennium BCE at all. The less said about attempts to connect her to anything “Proto-Indo-European”, the better.

Like many other names of deities, Nanaya’s was already a subject of etymological speculation in antiquity. A late annotated version of the Weidner god list, tablet BM 62741, preserves a scribe’s speculative attempt at deriving it from the basic meaning of the sign NA, “to call”, furnished with a feminine suffix, A. Needless to say, like other such examples of scribal speculation, some of which are closer to playful word play than linguistics, it is unlikely to reflect the actual origin of the name.

Early history: Shulgi-simti, Nanaya’s earliest recorded #1 fan

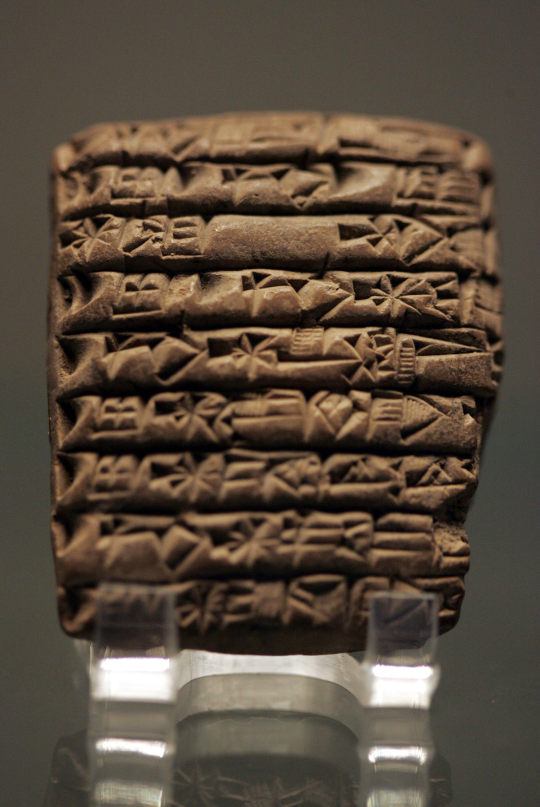

A typical Ur III administrative tablet listing offerings to various deities (wikimedia commons)

The first absolutely certain attestations of Nanaya, now firmly under her full name, have been identified in texts from the famous archive from Puzrish-Dagan, modern Drehem, dated to around 2100 BCE. Much can be written about this site, but here it will suffice to say that it was a center of the royal administration of the Third Dynasty of Ur ("Ur III") responsible for the distribution of sacrificial animals. Nanaya appears there in a rather unique context - she was one of the deities whose cults were patronized by queen Shulgi-simti, one of the wives of Shulgi, the successor of the dynasty’s founder Ur-Namma. We do not know much about Shulgi-simti as a person - she did not write any official inscriptions announcing her preferred foreign policy or letters to relatives or poetry or anything else that typically can be used to gain a glimpse into the personal lives of Mesopotamian royalty. We’re not really sure where she came from, though Eshnunna is often suggested as her hometown. We actually do not even know what her original name was, as it is assumed she only came to be known as Shulgi-simti after becoming a member of the royal family. Tonia Sharlach suggested that the absence of information about her personal life might indicate that she was a commoner, and that her marriage to Shulgi was not politically motivated The one sphere of Shulgi-simti’s life which we are incredibly familiar with are her religious ventures. She evidently had an eye for minor, foreign or otherwise unusual goddesses, such as Belet-Terraban or Nanaya. She apparently ran what Sharlach in her “biography” of her has characterized as a foundation. It was tasked with sponsoring various religious celebrations. Since Shulgi-simti seemingly had no estate to speak of, most of the relevant documents indicate she procured offerings from a variety of unexpected sources, including courtiers and other members of the royal family. The scale of her operations was tiny: while the more official religious organizations dealt with hundreds or thousands of sacrificial animals, up to fifty or even seventy thousand sheep and goats in the case of royal administration, the highest recorded number at her disposal seems to be eight oxen and fifty nine sheep. A further peculiarity of the “foundation” is that apparently there was a huge turnover rate among the officials tasked with maintaining it. It seems nobody really lasted there for much more than four years. There are two possible explanations: either Shulgi-simti was unusually difficult to work with, or the position was not considered particularly prestigious and was, at the absolute best, viewed as a stepping stone. While the Shulgi-simti texts are the earliest evidence for worship of Nanaya in the Ur III court, they are actually not isolated. When all the evidence from the reigns of Shulgi and his successors is summarized, it turns out that she quickly attained a prominent role, as she is among the twelve deities who received the most offerings. However, her worship was seemingly limited to Uruk (in her own sanctuary), Nippur (in the temple of Enlil, Ekur) and Ur. Granted, these were coincidentally three of the most important cities in the entire empire, so that’s a pretty solid early section of a divine resume. She chiefly appears in two types of ceremonies: these tied to the royal court, or these mostly performed by or for women. Notably, a festival involving lamentations (girrānum) was held in her honor in Uruk. To understand Nanaya’s presence in the two aforementioned contexts, and by extension her persistence in Mesopotamian religion in later periods, we need to first look into her character.

The character of Nanaya: eroticism, kingship, and disputed astral ventures

Corona Borealis (wikimedia commons)

Nanaya’s character is reasonably well defined in primary sources, but surprisingly she was almost entirely ignored in scholarship quite recently. The first study of her which holds up to scrutiny is probably Joan Goodnick Westenholz’s article Nanaya, Lady of Mystery from 1997. The core issue is the alleged interchangeability of goddesses. From the early days of Assyriology basically up to the 1980s, Nanaya was held to be basically fully interchangeable with Inanna. This obviously put her in a tough spot. Still, over the course of the past three decades the overwhelming majority of studies came to recognize Nanaya as a distinct goddess worthy of study in her own right. You will still stumble upon the occasional “Nanaya is basically Inanna”, but now this is a minority position. Tragically it’s not extinct yet, most recently I’ve seen it in a monograph published earlier this year. With these methodological and ideological issues out of the way, let’s actually look into Nanaya’s character, as promised by the title of this section. Her original role was that of a goddess of love. It is already attested for her at the dawn of her history, in the Ur III period. Her primary quality was described with a term rendered as ḫili in Sumerian and kuzbu in Akkadian. It can be variously translated as “charm”, “luxuriance”, “voluptuousness”, “sensuality” or “sexual attractiveness”. This characteristic was highlighted by her epithet bēlet kuzbi (“lady of kuzbu”) and by the name of her cella in the Eanna, Eḫilianna. The connection was so strong that this term appears basically in every single royal inscription praising her. She was also called bēlet râmi, “lady of love”. Nanaya’s role as a love goddess is often paired with describing her as a “joyful” or “charming” deity. It needs to be stressed that Nanaya was by no metric the goddess of some abstract, cosmic love or anything like that. Love incantations and prayers related to love are quite common, and give us a solid glimpse into this matter. Nanaya’s range of activity in them is defined pretty directly: she deals with relationships (and by extension also with matters like one-sided crushes or arguments between spouses), romance and with strictly sexual matters. For an example of a hymn highlighting her qualifications when it comes to the last category, see here. The text is explicit, obviously. We can go deeper, though. There is also an incantation whose incipit at first glance leaves little to imagination:

However, the translator, Giole Zisa, notes there is some debate over whether it’s actually about having sex with Nanaya or merely about invoking her (and other deities) while having sex with someone else. A distinct third possibility is that she’s not even properly invoked but that “oh, Nanaya” is simply an exclamation of excitement meant to fit the atmosphere, like a specialized version of the mainstay of modern erotica dialogue, “oh god”.

While this romantic and sexual aspect of Nanaya’s character is obviously impossible to overlook, this is not all there was to her. She was also associated with kingship, as already documented in the Ur III period. She was invoked during coronations and mourning of deceased kings. In the Old Babylonian period she was linked to investiture by rulers of newly independent Uruk. A topic which has stirred some controversy in scholarship is Nanaya’s supposed astral role. Modern authors who try to present Nanaya as a Venus deity fall back on rather faulty reasoning, namely asserting that if Nanaya was associated with Inanna and Inanna personified Venus, clearly Nanaya did too. Of course, being associated with Inanna does not guarantee the same traits. Shaushka was associated with her so closely her name was written with the logogram representing her counterpart quite often, and lacked astral aspects altogether. No primary sources which discuss Nanaya as a distinct, actively worshiped deity actually link her with Venus. If you stretch it you will find some tidbits like an entry in a dictionary prepared by the 10th century bishop Hasan bar Bahlul, who inexplicably asserted Nanaya was the Arabic name of the planet Venus. As you will see soon, there isn’t even a possibility that this reflected a relic of interpretatio graeca. The early Mandaean sources, many of which were written when at least remnants of ancient Mesopotamian religion were still extant, also do not link Nanaya with Venus. Despite at best ambivalent attitude towards Mesopotamian deities, they show remarkable attention to detail when it comes to listing their cult centers, and on top of that Mesopotamian astronomy had a considerable impact on Mandaeism, so there is no reason not to prioritize them, as far as I am concerned. As far as the ancient Mesopotamian sources themselves go, the only astral object with a direct connection to Nanaya was Corona Borealis (BAL.TÉŠ.A, “Dignity”), as attested in the astronomical compendium MUL.APIN. Note that this is a work which assigns astral counterparts to virtually any deity possible, though, and there is no indication this was a major part of Nanaya’s character. Save for this single instance, she is entirely absent from astronomical texts. A further astral possibility is that Nanaya was associated with the moon. The earliest evidence is highly ambiguous: in the Ur III period festivals held in her honor might have been tied to phases of the moon, while in the Old Babylonian period a sanctuary dedicated to her located in Larsa was known under the ceremonial name Eitida, “house of the month”. A poem in which looking at her is compared to looking at the moon is also known. That’s not all, though. Starting with the Old Babylonian period, she could also be compared with the sun. Possibly such comparisons were meant to present her as an astral deity, without necessarily identifying her with a specific astral body. Michael P. Streck and Nathan Wasserman suggest that it might be optimal to simply refer to her as a “luminous” deity in this context. However, as you will see later it nonetheless does seem she eventually came to be firmly associated both with the sun and the moon. Last but not least, Nanaya occasionally displayed warlike traits. It’s hardly major in her case, and if you tried hard enough you could turn any deity into a war deity depending on your political goals, though. I’d also place the incantation which casts her as one of the deities responsible for keeping the demon Lamashtu at bay here.

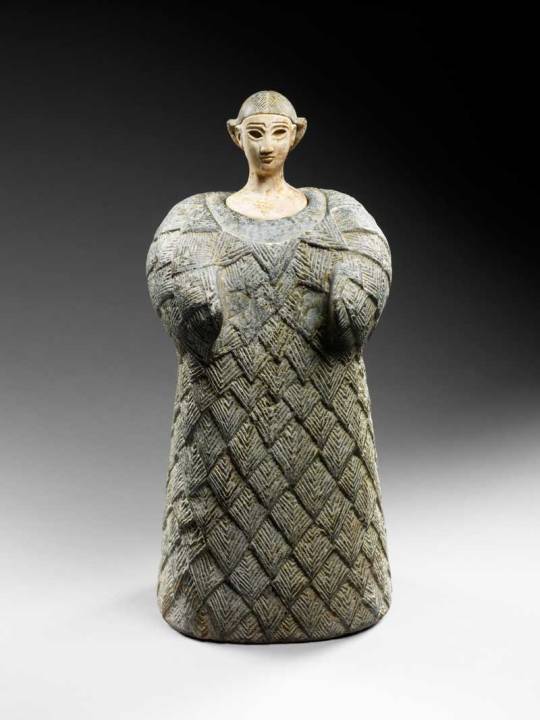

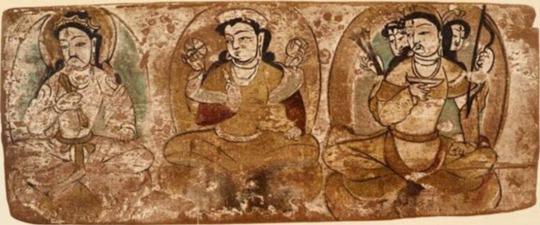

Nanaya in art

The oldest known depiction of Nanaya (wikimedia commons)

While Nanaya’s roles are pretty well defined, there surprisingly isn’t much to say about her iconography in Mesopotamian art.The oldest certain surviving depiction of her is rather indistinct: she’s wearing a tall headdress and a flounced robe. It dates to the late Kassite period (so roughly to 1200 BCE), and shows her alongside king Meli-Shipak (or maybe Meli-Shihu, reading remains uncertain) and his daughter Hunnubat-Nanaya. Nanaya is apparently invoked to guarantee that the prebend granted to the princess will be under divine protection. This is not really some unique prerogative of hers, perhaps she was just the most appropriate choice because Hunnubat-Nanaya’s name obviously reflects devotion to her. The relief discussed above is actually the only depiction of Nanaya identified with certainty from before the Hellenistic period, surprisingly. We know that statues representing her existed, and it is hard to imagine that a popular, commonly worshiped deity was not depicted on objects like terracotta decorations and cylinder seals, but even if some of these were discovered, there’s no way to identify them with certainty. This is not unusual though, and ultimately there aren’t many Mesopotamian deities who can be identified in art without any ambiguity.

Nanaya in literature

As I highlighted in the section dealing with Nanaya’s character, she is reasonably well attested in love poetry. However, this is not the only genre in which she played a role. A true testament to Nanaya’s prominence is a bilingual (Sumero-Akkadian) hymn composed in her honor in the first millennium BCE. It is written in the first person, and presents various other goddesses as her alternate identities. It is hardly unique, and similar compositions dedicated to Ishtar (Inanna), Gula, Ninurta and Marduk are also known. Each strophe describes a different deity and location, but ends with Nanaya reasserting her actual identity with the words “still I am Nanaya”. Among the claimed identities included are both major goddesses in their own right (Inanna plus closely associated Annunitum and Ishara, Gula, Bau, Ninlil), goddesses relevant due to their spousal roles first and foremost (Damkina, Shala, Mammitum etc) and some truly unexpected, picks, the notoriously elusive personified rainbow Manzat being the prime example. Most of them had very little in common with Nanaya, so this might be less an attempt at syncretism, and more an elevation of her position through comparisons to those of other goddesses. An additional possible literary curiosity is a poorly preserved myth which Wilfred G. Lambert referred to as “The murder of Anshar”. He argues that Nanaya is one of the two deities responsible for the eponymous act. I don't quite follow the logic, though: the goddess is actually named Ninamakalamma (“Lady mother of the land”), and her sole connection with Nanaya is that they occur in sequence in the unique god list from Sultantepe. Lambert saw this as a possible indication they are identical. There are no other attestations of this name, but ama kalamma does occur as an epithet of various goddesses, most notably Ninshubur. Given her juxtaposition with Nanaya in the Weidner god list - more on that later - wouldn’t it make more sense to assume it’s her? Due to obscurity of the text as far as I am aware nobody has questioned Lambert’s tentative proposal yet, though.

There isn’t much to say about the plot: Anshar, literally “whole heaven”, the father of Anu, presumably gets overthrown and might be subsequently killed. Something that needs to be stressed here to avoid misinterpretation: primordial deities such as Anshar were borderline irrelevant, and weren't really worshiped. They exist to fade away in myths and to be speculated about in elaborate lexical texts. There was no deposed cult of Anshar. Same goes for all the Tiamats and Enmesharras and so on.

Inanna and beyond: Nanaya and friends in Mesopotamian sources

Inanna on a cylinder seal from the second half of the third millennium BCE (wikimedia commons)

Of course, Nanaya’s single most important connection was that to Inanna, no matter if we are to accept the view that she was effectively a hypostasis gone rogue or not. The relationship between them could be represented in many different ways. Quite commonly she was understood as a courtier or protegee of Inanna. A hymn from the reign of Ishbi-Erra calls her the “ornament of Eanna” (Inanna’s main temple in Uruk) and states she was appointed by Inanna to her position. References to Inanna as Nanaya’s mother are also known, though they are rare, and might be metaphorical. To my best knowledge nothing changed since Olga Drewnowska-Rymarz’s monograph, in which she notes she only found three examples of texts preserving this tradition. I would personally abstain from trying to read too deep into it, given this scarcity. Other traditions regarding Nanaya’s parentage are better attested. In multiple cases, she “borrows” Inanna’s conventional genealogy, and as a result is addressed as a daughter of Sin (Nanna), the moon god. However, she was never addressed as Inanna’s sister: it seems that in cases where Sin and Nanaya are connected, she effectively “usurps” Inanna’s own status as his daughter (and as the sister of Shamash, while at it). Alternatively, she could be viewed as a daughter of Anu. Finally, there is a peculiar tradition which was the default in laments: in this case, Nanaya was described as a daughter of Urash. The name in this context does not refer to the wife of Anu, though. The deity meant is instead a small time farmer god from Dilbat. To my best knowledge no sources place Nanaya in the proximity of other members of Urash’s family, though some do specify she was his firstborn daughter. To my best knowledge Urash had at least two other children, Lagamal (“no mercy”, an underworld deity whose gender is a matter of debate) and Ipte-bitam (“he opened the house”, as you can probably guess a divine doorkeeper). Nanaya’s mother by extension would presumably be Urash’s wife Ninegal, the tutelary goddess of royal palaces. There is actually a ritual text listing these three together. In the Weidner god list Nanaya appears after Ninshubur. Sadly, I found no evidence for a direct association between these two. For what it’s worth, they did share a highly specific role, that of a deity responsible for ordering around lamma. This term referred to a class of minor deities who can be understood as analogous to “guardian angels” in contemporary Christianity, except places and even deities had their own lamma too, not just people. Lamma can also be understood at once as a class of distinct minor deities, as the given name of individual members of it, and as a title of major deities. In an inscription of Gudea the main members of the official pantheon are addressed as “lamma of all nations”, by far one of my favorite collective terms of deities in Mesopotamian literature. A second important aspect of the Weidner god list is placing Nanaya right in front of Bizilla. The two also appear side by side in some offering lists and in the astronomical compendium MUL.APIN, where they are curiously listed as members of the court of Enlil. It seems that like Nanaya, she was a goddess of love, which is presumably reflected by her name. It has been variously translated as “pleasing”, “loving” or as a derivative of the verb “to strip”. An argument can be made that Bizilla was to Nanaya what Nanaya was to Inanna. However, she also had a few roles of her own. Most notably, she was regarded as the sukkal of Ninlil. She may or may not also have had some sort of connection to Nungal, the goddess of prisons, though it remains a matter of debate if it’s really her or yet another, accidentally similarly named, goddess.

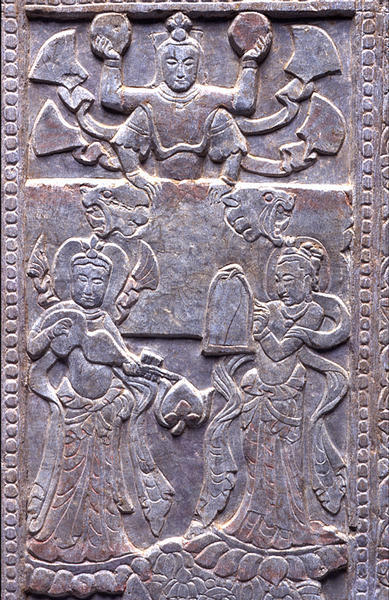

An indistinct Hurro-Hittite depiction of Ishara from the Yazilikaya sanctuary (wikimedia commons)

In love incantations, Nanaya belonged to an informal group which also included Inanna, Ishara, Kanisurra and Gazbaba. I do not think Inanna’s presence needs to be explained. Ishara had an independent connection with Inanna and was a multi-purpose deity to put it very lightly; in the realm of love she was particularly strongly connected with weddings and wedding nights. Kanisurra and Gazbaba warrant a bit more discussion, because they are arguably Nanaya’s supporting cast first and foremost. Gazbaba is, at the core, seemingly simply the personification of kuzbu. Her name had pretty inconsistent orthography, and variants such as Kazba or Gazbaya can be found in primary sources too. The last of them pretty clearly reflects an attempt at making her name resemble Nanaya’s. Not much can be said about her individual character beyond the fact she was doubtlessly related to love and/or sex. She is described as the “grinning one” in an incantation which might be a sexual allusion too, seeing as such expressions are a mainstay of Akkadian erotic poetry. Kanisurra would probably win the award for the fakest sounding Mesopotamian goddess, if such a competition existed. Her name most likely originated as a designation of the gate of the underworld, ganzer. Her default epithet was “lady of the witches” (bēlet kaššāpāti). And on top of that, like Nanaya and Gazbaba she was associated with sex. She certainly sounds more like a contemporary edgy oc of the Enoby Dimentia Raven Way variety than a bronze age goddess - and yet, she is completely genuine. It is commonly argued Kanisurra and Gazbaba were regarded as Nanaya’s daughters, but there is actually no direct evidence for this. In the only text where their relation to Nanaya is clearly defined they are described as her hairdressers, rather than children. While in some cases the love goddesses appear in love incantations in company of each other almost as if they were some sort of disastrous polycule, occasionally Nanaya is accompanied in them by an anonymous spouse. Together they occur in parallel with Inanna and Dumuzi and Ishara and Almanu, apparently a (accidental?) deification of a term referring to someone without family obligations. There is only one Old Babylonian source which actually assigns a specific identity to Nanaya’s spouse, a hymn dedicated to king Abi-eshuh of Babylon. An otherwise largely unknown god Muati (I patched up his wiki article just for the sake of this blog post) plays this role here. The text presents a curious case of reversal of gender roles: Muati is asked to intercede with Nanaya on behalf of petitioners. Usually this was the role of the wife - the best known case is Aya, the wife of Shamash, who is implored to do just that by Ninsun in the standard edition of the Epic of Gilgamesh. It’s also attested for goddesses such as Laz, Shala, Ninegal or Ninmug… and in the case of Inanna, for Ninshubur.

A Neo-Assyrian statue of Nabu on display in the Iraq Museum (wikimedia commons)

Marten Stol seems to treat Muati and Nabu as virtually the same deity, and on this basis states that Nanaya was already associated with the latter in the Old Babylonian period, but this seems to be a minority position. Other authors pretty consistently assume that Muati was a distinct deity at some point “absorbed” by Nabu. The oldest example of pairing Nanaya with Nabu I am aware of is an inscription dated to the reign of Marduk-apla-iddina I, so roughly to the first half of the twelfth century BCE. The rise of this tradition in the first millennium BCE was less theological and more political. With Babylon once again emerging as a preeminent power, local theologies were supposed to be subordinated to the one followed in the dominant city. Which, at the time, was focused on Nabu, Marduk and Zarpanit. Worth noting that Nabu also had a spouse before, Tashmetum (“reconciliation”). In the long run she was more or less ousted by Nanaya from some locations, though she retained popularity in the north, in Assyria. She is not exactly the most thrilling deity to discuss. I will confess I do not find the developments tied to Nanaya and Nabu to be particularly interesting to cover, but in the long run they might have resulted in Nanaya acquiring probably the single most interesting “supporting cast member” she did not share with Inanna, so we’ll come back to this later. Save for Bizilla, Nanaya generally was not provided with “equivalents” in god lists. I am only aware of one exception, and it’s a very recent discovery. Last year the first ever Akkadian-Amorite bilingual lists were published. This is obviously a breakthrough discovery, as before Amorite was largely known just from personal names despite being a vernacular language over much of the region in the bronze age, but only one line is ultimately of note here. In a section of one of the lists dealing with deities, Nanaya’s Amorite counterpart is said to be Pidray. This goddess is otherwise almost exclusively known from Ugarit. This of course fits very well with the new evidence: recent research generally stresses that Ugarit was quintessentially an Amorite city (the ruling house even claimed descent from mythical Ditanu, who is best known from the grandiose fictional genealogies of Shamshi-Adad I and the First Dynasty of Babylon). Sadly, we do not know how the inhabitants of Ugarit viewed Nanaya. A trilingual version of the Weidner list, with the original version furnished with columns listing Ugaritic and Hurrian counterparts of each deity, was in circulation, but the available copies are too heavily damaged to restore it fully. And to make things worse, much of it seems to boil down to scribal wordplay and there is no guarantee all of the correspondences are motivated theologically. For instance, the minor Mesopotamian goddess Imzuanna is presented as the counterpart of Ugaritic weather god Baal because her name contains a sign used as a shortened logographic writing of the latter. An even funnier case is the awkward attempt at making it clear the Ugaritic sun deity Shapash, who was female, is not a lesbian… by making Aya male. Just astonishing, really.

The worship of Nanaya

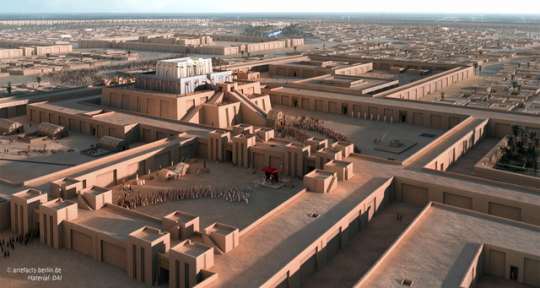

A speculative reconstruction of Ur III Uruk with the Eanna temple visible in the center (Artefacts — Scientific Illustration & Archaeological Reconstruction; reproduced here for educational purposes only, as permitted)

Rather fittingly, as a deity associated with Inanna, Nanaya was worshiped chiefly in Uruk. She is also reasonably well attested in the inscriptions of the short-lived local dynasty which regained independence near the end of the period of domination of Larsa over Lower Mesopotamia. A priest named after her, a certain Iddin-Nanaya, for a time served as the administrator of her temple, the Enmeurur, “house which gathers all the me,” me being a difficult to translate term, something like “divine powers”. The acquisition of new me is a common topic in Mesopotamian literature, and in compositions focused on Inanna in particular, so it should not be surprising to anyone that her peculiar double seemingly had similar interests. In addition to Uruk, as well as Nippur and Ur, after the Ur III period Nanaya spread to multiple other cities, including Isin, Mari, Babylon and Kish. However, she is probably by far the best attested in Larsa, where she rose to the rank of one of the main deities, next to Utu, Inanna, Ishkur and Nergal. She had her own temple, the Eshahulla, “house of a happy heart”. In local tradition Inanna got to keep her role as an “universal” major goddess and her military prerogatives, but Nanaya overtook the role of a goddess of love almost fully. Inanna’s astral aspect was also locally downplayed, since Venus was instead represented in the local pantheon by closely associated, but firmly distinct, Ninsianna. This deity warrants some more discussion in the future just due to having a solid claim to being one of the first genderfluid literary figures in history, but due to space constraints this cannot be covered in detail here. A later inscription from the same city differentiates between Nanaya and Inanna by giving them different epithets: Nanaya is the “queen of Uruk and Eanna” (effectively usurping Nanaya’s role) while Inanna is the “queen of Nippur” (that’s actually a well documented hypostasis of her, not to be confused with the unrelated “lady of Nippur”). Uruk was temporarily abandoned in the late Old Babylonian period, but that did not end Nanaya’s career. Like Inanna, she came to be temporarily relocated to Kish. It has been suggested that a reference to her residence in “Kiššina” in a Hurro-Hittite literary text, the Tale of Appu, reflects her temporary stay there. The next centuries of Nanaya are difficult to reconstruct due to scarce evidence, but it is clear she continued to be worshiped in Uruk. By the Neo-Babylonian period she was recognized as a member of an informal pentad of the main deities of the city, next to Inanna, Urkayitu, Usur-amassu and Beltu-sa-Resh. Two of them warrant no further discussion: Urkayitu was most likely a personification of the city, and Beltu-sa-Resh despite her position is still a mystery to researchers. Usur-amassu, on the contrary, is herself a fascinating topic. First attestations of this deity, who was seemingly associated with law and justice (a pretty standard concern), come back to the Old Babylonian period. At this point, Usur-amassu was clearly male, which is reflected by the name. He appears in the god list An = Anum as a son of the weather deity couple par excellence, Adad (Ishkur) and Shala. However, by the early first millennium BCE Usur-amassu instead came to be regarded as female - without losing the connection to her parents. She did however gain a connection to Inanna, Nanaya and Kanisurra, which she lacked earlier. How come remains unknown. Most curiously her name was not modified to reflect her new gender, though she could be provided with a determinative indicating it. This recalls the case of Lagamal in the kingdom of Mari some 800 years earlier.

The end of the beginning: Nanaya under Achaemenids and Seleucids

Trilingual (Persian, Elamite and Akkadian) inscription of the first Achamenid ruler of Mesopotamia, Cyrus (wikimedia commons)