#RightToHealth

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Lovely Foundation is a dedicated healthcare NGO in India aimed at enabling needy persons to access quality healthcare services. The foundation supports communities with limited access to medical services through free medical camps, health awareness initiatives, and free essential medicines.

Lovely Foundation helps serve the most disadvantaged within the communities, focussing on maternal and child health, hygiene education, and preventive care. Lovely Foundation ensures that doctors, dedicated volunteers, and generous donors can help bridge the gap between health services and those in need. Join us in the mission to build a healthier India. Everyone deserves the right to live a health, and dignified life.

#RightToHealth#HealthForHumanity#NGOForHealth#MedicalAidIndia#HealthyIndia#FreeMedicalCamps#CommunityHealth#WellnessForAll#HealthcareSupport

0 notes

Text

Health Equity In India- Road To Ensure Access To All

Health equity in India remains a challenge as rural areas face a shortage of doctors and resources. Bridging the gap is critical for equitable healthcare access.

#HealthEquity#HealthcareForAll#RuralHealthcare#IndiaHealth#RightToHealth#HealthcareAccess#PHCChallenges#HealthForEveryone

0 notes

Text

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution

https://www.ecospacerealtors.in/post/article-21-of-the-indian-constitution

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution: A Detailed Overview

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution is one of the most significant provisions safeguarding individual rights in India. It provides a fundamental right that ensures every citizen the right to life and personal liberty. Over the years, the Supreme Court has interpreted Article 21 expansively, transforming it into a powerful legal tool that encompasses a wide range of rights essential to living a dignified life.

Text of Article 21:

"No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to the procedure established by law."

While this seems concise, its scope has expanded significantly through judicial interpretations to include various facets of human life and personal freedom.

Key Components of Article 21:

Right to Life: The "right to life" does not merely mean the right to survive. The Supreme Court has interpreted this to include the right to live with dignity, which covers basic human necessities such as food, shelter, education, and healthcare.

Right to Personal Liberty: This aspect protects individual freedom from illegal detention or interference. Any deprivation of personal liberty must follow proper legal procedures.

Evolution of Article 21 through Judicial Interpretation

The scope of Article 21 has broadened significantly, largely due to judicial activism and progressive interpretation by the Supreme Court. Here are some critical rights that fall under the umbrella of Article 21:

Right to Privacy: In the landmark Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017) judgment, the Supreme Court ruled that the right to privacy is a fundamental right under Article 21. This protects citizens from unwarranted state surveillance and intrusion into personal matters.

Right to a Pollution-Free Environment: In the case of Subhash Kumar v. State of Bihar (1991), the Supreme Court declared that the right to life includes the right to live in a clean and pollution-free environment, emphasizing environmental protection as a crucial component of human dignity.

Right to Livelihood: In the Olga Tellis v. Bombay Municipal Corporation (1985) case, the Court recognized that the right to life under Article 21 includes the right to livelihood, ensuring that citizens are protected from arbitrary evictions that may strip them of their means of living.

Right to Health: The Supreme Court has also recognized the right to health as part of the right to life, as seen in the Paschim Banga Khet Mazdoor Samity v. State of West Bengal (1996) case, which mandated the government to provide adequate healthcare facilities.

Right to Education: The Unnikrishnan v. State of Andhra Pradesh (1993) judgment led to the recognition of the right to education as a fundamental part of Article 21. This later resulted in the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009, ensuring education for children between the ages of 6 and 14.

Right to Die with Dignity: In Common Cause v. Union of India (2018), the Supreme Court upheld passive euthanasia, recognizing the right to die with dignity as a part of the right to life.

Right to Speedy Trial: In the Hussainara Khatoon v. State of Bihar (1979) case, the Court ruled that speedy trials are an essential component of personal liberty, highlighting the right of every individual to receive timely justice.

Article 21 and Environmental Protection

Article 21 has been instrumental in cases concerning environmental protection. The courts have ruled that the right to a healthy environment is intrinsic to the right to life. Some landmark cases include:

M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (1987): Known as the Ganga Pollution Case, the Supreme Court ruled that pollution of the Ganges river violated the citizens' right to a clean and safe environment.

Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union of India (1996): The Court recognized the Precautionary Principle and Polluter Pays Principle as essential to safeguarding the right to a healthy environment under Article 21.

Article 21 and the Noble M Paikada v. Union of India Case

In Noble M Paikada v. Union of India [2024 INSC 241], Article 21 played a pivotal role. The Supreme Court struck down a notification exempting linear projects (such as roads and pipelines) from obtaining environmental clearances. The Court held that bypassing public consultation and environmental safeguards violated citizens' right to a pollution-free environment under Article 21. This case reinforces that any decision impacting the environment must prioritize public health and environmental well-being.

Conclusion

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution has evolved into a dynamic and expansive right that encompasses several aspects of human life and dignity. Through judicial interpretation, it has grown to include rights such as the right to privacy, right to a clean environment, right to education, and right to health, among others. The broad interpretation of this article highlights the importance of ensuring that both life and personal liberty are protected in the fullest sense, making it one of the most far-reaching constitutional provisions in India.

Disclaimer

This information is provided for educational purposes and should not be construed as legal advice. For legal interpretations or to understand how Article 21 applies to specific circumstances, it is recommended to consult a qualified legal professional.

Reach Us: 📞: +91 9900984444 📩 : [email protected] 🌐 : www.ecospacerealtors.in @ Your One-Stop Shop for Property Needs.

#SairamLawAssociates#EcoSpaceRealtors#Article21#RightToLife#IndianConstitution#PersonalLiberty#PrivacyRights#FundamentalRights#HumanDignity#EnvironmentalProtection#JudicialInterpretation#RightToHealth#RightToEducation#PollutionFreeEnvironment#RightToPrivacy#RightToLivelihood#ConstitutionalLaw

0 notes

Text

How to File a Complaint Against Hospital Negligence in India

With Legal Guidance by Dr. Anthony Raju, Advocate, Supreme Court of India

Expert in Medical Negligence Cases in India & Abroad

---

🏥 Facing Hospital Negligence? Here’s What You Need to Do

If you or a loved one has suffered due to medical negligence, wrong treatment, surgical errors, or hospital misconduct, you have the full right to seek legal compensation and accountability under Indian law.

✅ Step-by-Step Legal Process for Filing a Hospital Negligence Complaint:

📁 1. Gather Strong Evidence

Medical records, bills, test reports, and prescriptions

Doctor’s notes, surgical reports, communication (SMS/Emails)

Photos, videos, witness statements

Expert medical opinion (optional but impactful)

✍️ 2. Draft a Formal Legal Complaint

Your complaint should clearly mention:

The hospital name and address

Dates and facts of the treatment

Specific acts of negligence or misconduct

Harm or injury caused (physical, emotional, or fatal)

Legal relief sought (compensation, apology, cancellation of license, etc.)

⚖️ 3. Legal Avenues Available

Consumer Court (District, State, or National Commission)

Civil Court (for compensation claims)

Criminal Complaint (IPC 304A: Death by negligence)

Medical Council of India / State Medical Council

National/State Human Rights Commission

Writ Petition in High Court or Supreme Court in serious matters

🛡️ Seek Free Expert Legal Representation

👨⚖️ Dr. Anthony Raju

Advocate, Supreme Court of India

Chairman, All India Council of Human Rights, Liberties & Social Justice

Top Legal Expert in Medical Negligence Cases – India & Abroad

Dr. Raju has decades of experience representing victims of hospital errors, ICU deaths, fake surgeries, overcharging, misdiagnosis, denial of emergency treatment, and unethical medical practices. He leads a national and international legal team dedicated to justice for medical negligence victims.

Medical negligence lawyer India

File hospital complaint India

How to sue hospital in India

Dr. Anthony Raju medical negligence expert

Best advocate for hospital negligence

Supreme Court lawyer medical cases

Legal help for ICU death India

File complaint against private hospital

Human rights in healthcare India

Medical malpractice justice India

#MedicalNegligence

#HospitalNegligence

#JusticeForPatients

#DrAnthonyRaju

#SupremeCourtAdvocate

#TopMedicalNegligenceLawyer

#RightToHealth

#MedicalMalpracticeIndia

#ConsumerCourtIndia

#LegalSupportForPatients

#PatientsRightsIndia

0 notes

Text

🌍 World Health Day 2025 🩺 "My Health, My Right" – This year’s theme reminds us that health is a basic human right, not a privilege.

Let’s take a moment to appreciate the importance of good health and commit to building a future where everyone has access to quality healthcare, clean air, safe food, and mental well-being. 💚

At Mewar University, we stand united in promoting a healthier, happier world.

#WorldHealthDay #MyHealthMyRight #HealthForAll #GlobalHealth #WellnessMatters #HealthyLiving #PublicHealth #MewarUniversity #HealthAwareness #StayHealthy #RightToHealth #MentalHealthMatters #HealthEquity #HealthyPlanet #PreventionIsBetterThanCure #StudentWellbeing #HealthcareAccess #OneWorldOneHealth

0 notes

Text

A free health awareness and checkup drive was arranged at Indiranagar, Chinchwad. Dr. Ashwini Pargewar examined 46 patients and Tejashree Khalate counseled them. Ujjwala Khalate helped with registration.Anand Misal looked after the arrangements.

Anita Said arranged the awareness drive under the guidance of Dr.Ashwin Porwal(Founder-President, HHF), Dr. Snehal Porwal(Founder-Secretary, HHF) & Madhura Bhate(NGO-Coordinator, HHF).

Special thanks to all members of Sneh Foundation, Pune for their unending support.

#spreadingsmiles #pilestosmiles #ruralhealth #nutritionist #curingwithcare #punehealthngo #womenhealth #servingsociety #breakingthesilence #awareness #givingback #righttohealth #dutytohelp #bhfyp❤️ #fistulas #fissurecare #healthforall #healthmatters #anorectal #herniacare #guthealthforall #internalpiles #externalpiles #bhfyp😊 #bhfypp #analpainrelief #pilescare #freecheckup #onecurestheothercares #healinghandsfoundation

0 notes

Text

Right to Health | By Saurabh Kumar | Indian Polity and Governance | Rau's IAS Study Circle

youtube

#righttohealth#Indian_Polity_and_Governance#indianpolity#indianconstitution#rausias#rauiasstudycirlce#ias#upsc#gspaper2#polity#polityandgovernance#UPSCMainsGSPaper2#IndianConstitution#laxmikantpolity#Youtube

0 notes

Photo

Can't believe this has to be fucking said. An estimated 25 million unsafe abortions happen annually. Nearly 8% of maternal deaths are attributed to unsafe abortions annually. Those most affected are women and girls in poverty or who are marginalised. Almost all deaths from unsafe abortions happen in countries where abortion is severely restricted by the law and/or in practice. These deaths are entirely preventable. In countries with less restricted abortion laws generally had lower abortion rates than countries with highly restrictive abortion laws. Source: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/SexualHealth/INFO_Abortion_WEB.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjd1Z6H78b4AhXObMAKHTg2AmYQFnoECAcQAQ&usg=AOvVaw1dTTBhEzA3CJyvu3gnapDj I have attached a fundraiser for Planned Parenthood in the hope we can support women who will be seeking appropriate and accessible healthcare in the coming weeks/months. Please give whatever you can, if you can. Please also let me know if there is another charity which helps women with relevant healthcare needs. #roevwade #humanrights #abortion #america #womensrights #unitedstates #usa #unitednations #safeabortion #abortionrights #womenshealth #healthcare #righttohealth #law #humanrightslaw #medicallaw #unhrc #plannedparenthood (at United Kingdom) https://www.instagram.com/p/CfM2UU0LkZu/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#roevwade#humanrights#abortion#america#womensrights#unitedstates#usa#unitednations#safeabortion#abortionrights#womenshealth#healthcare#righttohealth#law#humanrightslaw#medicallaw#unhrc#plannedparenthood

0 notes

Photo

#DOH #RO1 #RightToHealth #WHO

1 note

·

View note

Text

YES

Because the very heart at the heart of the matter, the matter at the heart of it is woman, yes, woman, and her body yes, and yes, the very heart at the heart of a woman’s body, the very heart of it is autonomy yes, and the right to choose yes, to choose and have control, the human right to make a choice yes and have control yes over the body yes, yes, yes - and yes is at the very heart, the very heart of the matter yes, to a woman’s right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, yes, and so yes, repeal the 8th yes, and yes my body my choice yes, and yes for sexual and reproductive health and rights yes, yes, yes, and yes, #Together4YES, and YES to this heart, and YES to my heart, my heart YES is a heart YES full of YES.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

September 17 of each year, coincides with the World Patient Safety Day. Promoted internationally by the World Health Organization it foresees the realization of awareness-raising initiatives. It includes the symbolic orange lighting of national monuments of the individual member countries. The Piramide Cestia in Rome is enlighted in orange. This year the 2nd "National Day for the safety of care and the assisted person" emphasizes that the safety of care is a constitutive part of the right to health, as provided for in Article 1 of Law 24 of 2017. #worldpatientsafetyday #worldpatientsafetyday2020 #worldpatientsafety #worldhealthorganization #who #orange #righttohealth #righttohealthcare #safetycare #🟠 #patientsrights #healthfirst #veryimportantmatter #sicurezzacure #patientsafety Giornata Mondiale per la sicurezza delle cure e delle persone assistite: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/news/p3_2_2_1_1.jsp?lingua=italiano&menu=eventi&p=daeventi&id=559 (presso World) https://www.instagram.com/p/CFOFS6hob_H/?igshid=h1ybe3evxjwu

#worldpatientsafetyday#worldpatientsafetyday2020#worldpatientsafety#worldhealthorganization#who#orange#righttohealth#righttohealthcare#safetycare#patientsrights#healthfirst#veryimportantmatter#sicurezzacure#patientsafety

0 notes

Photo

Lets look back at the efforts of HHF team who is consistently working on reaching out and encouraging people to speak up about their anorectal health. Yes! atleast one in each family suffers from either if piles, fissure, fistula or severe constipation. It becomes necessary to understand the root cause and seek proper treatment. At Wadebolai village 66 patients were diagnosed and helped with necessary medicines. Speacial thanks to Panchayat Samiti members, P.H.C. staff and ASHA workers for supporting us.

#spreadingsmiles#pilestosmiles#ruralhealth#nutrition#curingwithcare#fightcorona#womenhealth#servingsociety#breakingthesilence#awareness#givingback#righttohealth#dutytohelp#onecurestheothercares#healinghandsfoundation#@drashwinporwal (Founder/President HHF)#@drsnehaljain (Founder/Secretary HHF)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Approaching the Right to a Healthy Environment through Analysis of Economy versus Environment in the Works of Hayao Miyazaki

... authored by Elijah Bergevin, assigned by Dr. Rebecca Pearson for her course The Right to a Healthy Environment

1.1 The Right to a Healthy Environment

The right to a healthy environment is an ideal under which human necessities -- and to an extent ecological well-being -- must be guaranteed through the establishment of systems which protect those necessities, make them available, and bring justice upon harmful contrarians. In the United States, citizens and industries are expected to preserve fair standards of clean air and water which are set by the Environmental Protection Agency. Legal action can be taken against parties which may abuse such standards. However, the US government is not held accountable to consistently address situations of polluted resources, nor is there any individual environmental responsibility expected of its citizens. (Boyd, 2012) Additionally, EPA “fair standards” are often disputed for their lack of the consideration of the most current scientific conclusions in health and environmental studies. In a true legal sense, the right to a healthy environment does not exist whatsoever in the United States for it has yet to be constitutionalized into the Bill of Rights. This is true, in fact, for a large proportion of countries on earth; 46 of 193 have absolutely no environmental provision in their founding documents today (Boyd, 2012). Therefore, nearly 25% of sovereign nations do not maintain the right to a healthy environment (although legislation may exist to provide some structure).

1.2 Environment vs Economy, Humanity vs Nature

An overarching theme in the fight for environmental protections, and the right to a healthy environment, is that of environment versus economy. In a political sense, this subject entails two distinct perspectives: 1) industry cannot remain competitive and successful if business is limited in ways to preserve the environment and natural resources, and 2) economic prosperity and environmental sustainability are not adverse concepts but very possibly mutually assuring. The primary stance is inarguably the dominant one in the majority of the western world, though there is nuance to the debate depending on context (Smith & Parsons, 2012).

Take for example, the developmental state of a nation. In global efforts to reduce climate change, developing countries usually show resistance to environmentally-preservative economic limitations as they “struggle to achieve basic material security” (Running, 2014). Natural resource extraction and short-term cheap systems of waste management may in fact be the only means of establishing meaningful GDP. In fairness, these same countries are usually responsible for a smaller portion of climate-changing sources, such as greenhouse gas emissions. However, they also carry the heavier burden of risk surrounding consequences of climate change as found in Katrina Running’s article “Towards climate justice.”

In contrast, more developed countries may contain politicians which tow the line for sustainability in industry, yet with larger corporations involved in the market of said state, it can be difficult to find legislative action which satisfies the government and those businesses employing its citizens. More specifically, in countries with flimsy protections controlling industry involvement in politics, it is all too normal for big-business to influence representatives, shape legislation, and thereby circumnavigate citizen positions on issues like sustainability and climate change. As US Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez recently eloquated in the House Oversight Committee, any US official can legally campaign funded entirely by a special interest group, such as oil, and once elected be unlimited in their ability to deregulate laws around that industry for the gain of individuals and at the expense of the American people and environment.

Beyond this political framing of economy versus environment, there also exists a more loosely and artistically described parallel; humanity versus nature. It is a particularly pervasive ideal that, in the modern west, human activity and culture exists outside of the scope of nature (Smith & Parsons, 2012). The world around us, by this thinking, is but fuel for humanity to use for progress. However, this is shallow and historically uninformed rational. It is a rather recent development that humans have cultivated the ability to single-handedly control the resources of this globe and shape the nature of all other species’ environments. (Carson, 2015) Throughout the centuries, there lie examples of mankind contributing to a ecologically diverse settings, such as during the Edo period in Japan. There, human involvement in “the constant collection of leaves and wood kept the forest open and prevented succession to large trees and dense shade.” (Chan, 2015) Thus, we can observe the human role as a important part in the grand performance of “nature.” It is the challenge of today’s greatest minds to understand this relational truth and reintroduce the concept to the general public. This gauntlet of enlightenment has been championed by many scientists and activists, but it has found a particularly successful home in the hands of artists, such as those of Hayao Miyazaki and the Studio Ghibli team.

1.3 Studio Ghibli

Hayao Miyazaki was, until his recent retirement in 2013, the director of the Japanese animation company Studio Ghibli. The studio has produced a large collection of full length anime films, as well as an array of short specials, television series, and visuals for video games. These works are known worldwide and have received critical acclaim throughout the decades of the studio’s existence. Although each piece is complete and unique, there are undeniable themes which permeate all that Miyazaki touches: self-discovery, magic and fantasy, but most importantly environmental awareness and deep ecology. Miyazaki was profoundly moved by the reading of Sasuke Nakao’s book The Cultivation of Plants and the Origin of Agriculture from which Miyazaki reformed his Japanese identity and ideas on the human-nature relationship (Mumcu and Yilmaz, 2010). Nakao describes a similar early culture between peoples living in evergreen forests which is referred to as the “shiny-leaf culture” (Yamanaka, 2008). Under this lifestyle, “people depended on the forest and were anxious to coexist with it rather than destroy it” (Mumcu and Yilmaz, 2010). It is no surprise then that, owning this new self-enlightenment, Hayao Miyazaki flew into the scene of film production with his primary work Nausica and the Valley of the Wind (1984) which details a post-apocalyptic world overgrown with toxic forestry. The following year, Studio Ghibli was founded in full, and each film after has proudly touted motifs of environmental sustainability or irresponsibility, harmony or dystopia.

It is worth mention that a majority of Ghibli entertainment is marketed towards children and young adults, as is the dominant trend in the medium of animation. This is not inappropriate as many of the films feature younger protagonists, non-complex narratives, and bright visuals. However, to restrict intended audience to children is to ignore the ramifications these pieces may have upon adults. Michele J. Smith and Elizabeth Parsons write in their article, “Animating Child Activism” how environmental media “may function as a sop to the idea that it is now too late for adults, already entrenched in their lifestyles and beliefs, to adopt the challenge of changing themselves. Such a logic of displacement, or even the passing off of responsibility to the next generation to care about the environment, is perhaps one adults are reluctant to embrace in political and lifestyle choices.” Such is to say, the existence of pedagogy to involve and impassion young children in the fight to save their own future on this planet does not bar adult consumers from finding meaning and purpose in the same art to alter the status quo and create change for themselves as well as posterity.

1.4 Why this?

In this study, various productions of Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli will be analyzed as mediums to approach environmentalism and the right to a healthy environment. Why address such lofty political and human rights issues in this manner? Succinctly, average citizens are uninformed or misinformed about the processes and rights relating to the environment. At Central Washington University, one survey revealed that only 27.3% of 110 participants were correctly informed on both the lack of the US right to a healthy environment and the EPA’s shortcomings in setting current health-science-based standards. But this is no indictment; the simple truth is that many people are not faced with the everyday realities and outcomes of poor waste management, excessive energy use, or irresponsible resource production. They are unaware of the role they play in the human-environment relationship. The same Central Washington University study found that a majority 65.3% of 49 students did not utilize reusable cutlery despite its general availability on campus. Instead, disposable plastic options were chosen, and added to the 32 million tons of plastic discarded each year in the United States. Those utensils then sit in landfills, unable to biodegrade, or are burned producing greenhouse gases and nominal energy output. (Gourmelon, 2015)

Even knowing such information -- as some of these students presumably do -- it can be difficult to interpret the immediate and personal costs of unsustainable actions, despite their impending existence. Research conducted by the National Round Table on the Economy and the Environment found in Canada concluded that climate change will soon present huge financial burdens to Canada and those costs “could escalate from roughly $5 billion per year in 2020 … to between $21 billion and $43 billion per year by the 2050s” (NRTEE, 2011). Cheap and disposable solutions now, will create complicated expensive problems later. This is where the disruptive aesthetics of design activism, such as that of Hayao Miyazaki’s, becomes valuable. As Melanie Chan writes in her article “Environmentalism and the Animated Landscape,” “Indeed [Miyazaki] films invite audiences to identify with different locations and characters, and more specifically tensions between animism, technology, and political power, in order to develop an emotional connection to the environmental concerns they represent.” Narrative media provides a human and accessible gateway to realizing systemic issues and plausible justice. It is therefore appropriate, and furthermore responsible, to analyze how Studio Ghibli invokes the human right to a healthy environment through its representations of economy and environment, humanity and nature.

2.1 Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea

Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea (2008) was a co-production of Studio Ghibli and Walt Disney Animations Studios. The film follows Ponyo, a supernatural daughter of the Ocean, in her adventure far from her home of the deep sea. After escaping the watchful eye of her father, goldfish-like Ponyo finds herself in a terribly polluted human harbor where she is swept into a drifting glass jar and washed ashore. S��suke, five-year-old son of a local sailor, discovers Ponyo and, upon feeding her some ham, transforms the minnow into a little girl. Ponyo’s father, the sorcerer Fujimoto, is appalled to learn of this change when he realizes that Ponyo has abandoned the ocean for the likes of humans, whom he knows only as destructors of nature. In his ultimate attempt to retrieve Ponyo, Fujimoto -- and his love, the Ocean -- elect to flood the earth. The town, in a single night, is leveled. Ponyo and Sōsuke are separated from Sōsuke’s mother and embark on a journey to find her. However, the Ocean locates Sōsuke’s mother first and strikes a deal: all damage will be reversed and Ponyo may remain as a human, but only if Sōsuke promises to love her forever. The boy agrees, and the film ends as the waters recede.

It is necessary to clarify that Ponyo does not immediately present itself as a flaming gauntlet for environmental reform. At first blush, Ponyo is about the wonder of the sea and the innocence of young love. Deeper analysis reveals more meaningful themes and calls for action against environmental pollution and irresponsible waste management. The assault on Ponyo by marine litter is the catalyzing event of conflict in the film. It is by this product of human carelessness that nature is quite personally harmed. Miyazaki moves from this moment to represent the autonomy of nature in the bodies of Fujimoto and the Ocean goddess. The two supernatural forces shift from corrective powers, purifying and protecting the sea, to avenging entities, punishing the earth for the abuse of their waters and the “capture” of their daughter.

This context parallels loosely to current issues of marine life damage. In 2010, an estimate of 4.8 to 12.7 million metric tons of plastic made its way into the ocean. Currently, there is little evidence to support that human non-biodegradable waste in oceans are adverse to the biological health of marine organisms such as fish and birds. However, there is concern how the presence of such debris might restructure ecosystems by altering feeding practices or disabling species activity. Kara Lavender Law communicates some examples in her article ‘Plastics in the Marine Environment;’ “95% of 1,295 beached seabird carcasses in the North Sea contained plastic in their stomachs... and 83% of 626 North Atlantic whales examined in 29 years of sighting photographs had evidence of at least one entanglement in rope or netting.” In Ponyo, we are presented a visual and empathetic representation of this quandary as the goldfish-human is swept up in a garbage-trawler and caught in a glass jar, thereby separating her from her habitat and undeniably altering her life.

Rising sea levels are an another issue addressed by Ponyo. Industrial pollution and greenhouse gas productions have worked over the decades to increase global temperatures, specifically in Earth’s oceans. (US EPA, 2016) This heating is a likely cause of sea levels rising by an average of six hundredths of an inch each year since 1880 up until 2013. Rising waters have had tangible effects with global land loss, including the loss of twenty square miles of US coast to the Atlantic ocean since 1996. (US EPA, 2014) The flooding of Sōsuke’s harbor village is an extremely accelerated depiction of such land loss. These two human-environment relations of ocean pollution and rising sea levels in Ponyo are interesting in their different involvement of truly human characters as well as their aesthetics. While rising sea levels most definitely damage the state of Sōsuke’s home, the polluted waters of the harbor are not depicted as harmful to the humans. Rather, the personified Nature characters are most offended by the waste. It is only in this medium of film, where entities of the ocean can be humanized, that the pollution thereby is communicated as a “human” rights violation. As for aesthetics, note the scenes below of the marine trash are indeed unsightly with murky earth tones, communicating the distaste of human dumping in seas.

In contrast, the tone and palate of scenes as the town floods and after it has been submerged seek different goals. As the waves swell to swallow the village, the screen becomes darker and foreboding, but in the aftermath the viewer is subjected to vibrant and placid cuts of marine life peacefully existing in the same space as Sōsuke. This development serves as a portrait of the ocean’s wrath -- the threat of land loss -- but also its beauty and the synergy possible with humanity if it is treated with respect.

In its conclusion, Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea works to mediate the issues of marine pollution and rising sea levels through a contract between nature and humanity, where an oath to love the sea and respect its inhabitants as sovereign themselves (an oath to love Ponyo as a human) earns the people a second chance at a mutually beneficial relationship. This could be interpreted as the establishment of a right to clean waters and minimizing of climate changing sources. Let it be said, however, that this tradeoff is somewhat problematic. Primarily, there is no clear antagonizing human character in Ponyo and therefore it is too lax in its condemnation of pollution. Despite the clear statements blaming humankind as a whole -- “They spoil the sea; they treat your home like their empty black souls,” proclaims Fujimoto at 30:50 -- no single entity is ever confronted for unsustainable actions. Ponyo recommends systemic change but fails to identify any system.

2.2 My Neighbor Totoro

My Neighbor Totoro (1988) is a vignette on the life of Satsuki and Mei, two young girls who move to the rural countryside in order to better suit the needs of their sick mother. Surrounded by rice paddies and ancient trees, the sisters quickly fall in love with their new home. Since their professor father commutes daily to his university, and their mother is housed in a nearby hospital, Satsuki and Mei have ample time to explore their surrounding environment and one day encounter the forest spirit Totoro, who appears similar to a giant rabbit. The supernatural entity provides comfort for the girls with several adventures as they struggle to contemplate the possibility of a life without their mother. The narrative devices of Totoro are not extremely useful to the discussion of this film as environmental media. Totoro’s true value lies in its depiction of the beauty and unique sustainability of the setting satoyama landscape as well as the spiritual respect its characters have for the nature around them. The film aims to personify the gentle temper of nature through regal setting pieces, such as giant camphor tree that grows in the woods near the girls’ home, as well as through the forest spirits themselves -- animism that is customary in Japanese shintoism.

The mutually beneficial relationship between the nurturing environment and the humans that inhabit it demonstrates the values of deep ecology, humans as integral players in the cycles of nature.

Satoyama landscapes (the word ‘satoyama’ literally referring to hills and villages) are unique to the nation of Japan. Satoyama agricultural practices seek to effectively utilize rice paddy fields while conserving the original shape of the land by terracing irrigated sections. Similarly to the practices of aforementioned early “shiney-leaf culture,” satoyama systems promote a diversity of plant and animal life today to a level beyond what might be possible without human influence. In 2009, one study determined 5668 distinct species to be inhabiting Japan’s satoyama biospheres (Fukamachi, 2017). However, with the influx in population over the past century, and growing urbanization (not to mention the devastating effects of war in Japan), preservation of satoyama fields and forests has become difficult. Luckily, legislation has developed in recent years to counter these challenges, including the Act on Promotion of Development of Infrastructures for Leisure Stay in Rural Areas which highlighted green tourism in Japan. Notably, much of the movement to implement these laws stemmed from the cultural phenomena that was My Neighbor Totoro. (Yokohari and Bolthouse, 2011) Miyazaki even went as far as to establish the Totoro Home Country Foundation to rally support for preservation efforts.

Counter to Japan’s sustainability in agricultural production, much of America’s food industry practices are lacking in means of environmental preservation and effectiveness. The majority of such realities can be traced to governmental intervention in the past century to protect from economic disparities (Bowler, 2002). Whether the trade-off was appropriate is a separate discussion, but it stands that farming and ranching desperately require reform that can only be accomplished by legislative changes. Food farming subsidies today cost disproportionate amounts and create wasteful food surplus. Neither Japan nor the US have incorporated the right to a healthy environment in their constitutions. To take further queue from My Neighbor Totoro might permanently protect sustainability and cultural landscapes in Japan, establishing the right to dependable food sources for all citizens. The US would be wise to follow suit.

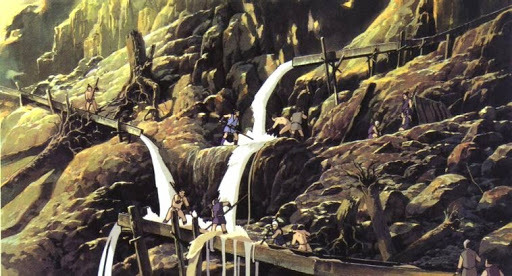

2.3 Princess Mononoke

Princess Mononoke (1997) opens on a secluded Japanese village sometime in the 15th century. The resident Emishi people are suddenly attacked one day by a nature deity turned demonic, and the Emishi prince Ashitaka is wounded and cursed as he slays the rampaging spirit. Doomed to die by the affliction, Ashitaka sets out to discover the origins of the demon’s fury and to “see with eyes unclouded by hate.” He soon finds himself in the midst of a war for a distant forest. Lady Eboshi, founder of the weapon forge staffed by lepers and sex worker called Irontown, has clear-cut large swaths of the area and angered the local spirits including the wolf god Moro and her adopted human daughter, San. Additionally, the emperor has demanded of Lady Eboshi the head of the Great Forest Spirit -- a human faced deer god -- believing it will grant him immortality. Much to Ashitaka’s horror, many forest spirits and humans are losing their lives to the conflict. When San infiltrates Irontown to kill Eboshi, Ashitaka steps in to stop the violence and is shot himself. San, feeling pity, whisks Ashitaka to the woods so the Great Forest Spirit may heal him. He is saved, but Eboshi has followed them to the Great Spirit and decapitates the beast. Instantly black ooze erupts from the headless body and it destroys all that it touches; the forest and Irontown are quickly dissolving. Ashitaka and San recapture the head and rejoin it to the body. The film ends as life returns to the valley and the war reaches a tentative conclusion -- Lady Eboshi elects to start over and build a better town while San retreats to the wilderness.

Mononoke is undoubtedly the Ghibli film with strongest themes of environmentalism and human rights. Hapless resource extraction and adjunct landscape degradation leads to impossible living conditions for anthropomorphized animals and humans, and even corrupts a few souls. There is little subtlety in the representation of nature as San and the animal spirits and the embodiment of human economy in Lady Eboshi and her iron workers. Less intuitive may be the audience-narrator relationship folded in Ashitaka, an empathetic character who respects the life and needs of both sides of the war. It should be noted that the entire narrative might succeed just as effectively without the prince’s presence; the war would still ensue, the Great Spirit would still be beheaded, the valley would still be wasted and resurrected. Thus, the inclusion of protagonist Ashitaka may be a queue to viewers that neither party is right to kill, and this is furthered by the uneasy conclusion of the film. Although both parties (San and Eboshi) maintain their lives, “the greater conflict between industry and nature is left unresolved.” (Thevenin, 2013) No one is proclaimed victor so the ends cannot justify the means.

Such tension is reminiscent of the struggles of indigenous people around the globe today where an array of industrial activities threaten their health as well as their access to clean water and air. Though there is obviously a wide diversity in lifestyle of separate indigenous groups, the disproportionate amount of environmental safety struggles affecting indigenous persons is likely due to their generally shared culture and tradition of living closely with the earth (Schlosberg & Caruthers, 2010). One such instance includes the Mayan Indigenous Communities of Toledo fight against logging and oil extraction in Belize. The community went before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights claiming the resource extraction violated their right to a healthy environment under the rights to life and health (Boyd, 2012). The court found these grounds valid and took action, however there are a slew of similar examples where justice was not served due to lack of established rights. This parallel might earn San and the forest inhabitants an effective change in the extraction of mineral ore by Irontown.

Conversely, the plight of Irontown residents is also cleverly posited in the film. Lady Eboshi’s havening on behalf of the sick and socially marginalized groups, and her intense loyalty to their well-being, communicates that she is indeed not devoid of good. Her emphasis of economic success over the preservation of the world around her entails complex layers of justification when done for those in need. In this manner, Irontown appears similar to a developing country where environmental ideals are generally sacrificed in order to supply basic human opportunities and material securities. However, to an issue of unsustainable forestry, there are current working models which ensure excellence in economy and environment. The US state of Oregon balances timber extraction with reforestation. Legislation specifies how, when, and where trees can be harvested and also when they must be replanted and regrown (OrigeonForests.org, n.d.). Establishing a right to sustainability of high-necessity resources could ensure such effective processes further than Oregon state borders.

Miyazaki works hard in Mononoke to depict the relationship between humanity and nature by animating contrasting scenes, beauty in synergy and distaste in conflict. The opening scenes of the Emishi village exemplify human respect for the environment, where terraced agriculture maintains the original form of the land and human structures intertwine with fauna.

In contrast, the atmosphere of Irontown -- where industry has no regard for the environment -- is drab and harsh in aesthetic. The audience is clearly presented the ugly results of clear-cutting. Almost no fauna is present to emphasize the lack of nature’s place at the table; humanity has attempted to dominate and yet the space in which the people must reside is now unclean and hazardous.

This difference can also be distinctly observed in the valley pans after the Great Forest Spirit has been decapitated, and after the head has been recollected. In the first scene nature has been further deprived by humanity, its greatest being treated as resource. In the second, humanity has finally yielded something back to its environment, and thus the valley re-blooms in opportunity.

One caveat in the representation of nature’s autonomy in both Princess Mononoke and Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea are the reactive and corrective characteristics employed. In both films, there is real danger to the environment that may make it uninhabitable for humans, though it is stemmed from human actions. In Ponyo, the citizens of the harbor town pollute the ocean and harm its wildlife. As vengeance, the Ocean god floods the city. In Mononoke, the citizens of Irontown irresponsibly extract all resources from the valley, and the Great Forest Spirit responds by trying to kill all beings in the valley. These depictions are useful as they artistically show pseudo-real effects of failing to protect human and nature’s rights to well-being. However, these allowances for the state of nature to perfectly self-correct are not extremely productive. The harbor un-floods in Ponyo, the valley re-blooms in Mononoke. These resolutions effectively undo the pedagogical work of each film by allowing the damage to be reversed (not endured or combated) by non-human hands. Although both films conclude with tentative allusions to a rights-based agreement being struck, this trait may not be practical in enlightening audiences to the realities of implementing the right to a healthy environment.

3.0 Conclusion

The right to a healthy environment is underrepresented in the founding documents of sovereign nations around the world despite its practical use to provide for the needs of human beings. Conflicts between interests in economic success and concern for environmental preservation may be a prominent source for this disconnect, but there are compromises that can ensure the best possible life for people and protect the spaces we inhabit. Artistic activism is one process through which we can better communicate and understand the costs of, and solutions to, unsustainable actions. Studio Ghibli demonstrates this through its films Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea, My Neighbor Totoro, and Princess Mononoke in not only content but visual aesthetic choices that engage audiences and inspire empathy. Although film alone cannot amend the real issues we face on environmentalism today, it can inspire responsibility to create change such as establishing new rights for the benefit of all.

Bibliography

Banner, B. (2019, February 07). Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez: Corruption Is Legal In The United States. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=250&v=Kz1lxKF2hDY.

Bowler, I. (2002). Developing Sustainable Agriculture. Geography,87(3), 205-212. Retrieved February 25, 2019, from https://www-jstor-org.

Boyd, D. (2012) The Right to a Healthy Environment Revitalizing Canada's Constitution. UBC Press. 68, 134, 209.

Carson, R. (2015). Silent spring. Penguin Books, in association with Hamish Hamilton.

Chan, M. (2015) “Environmentalism and the Animated Landscape in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) and Princess Mononoke (1997).” Animated Landscapes. doi:10.5040/9781501304804.ch-006.

Fukamachi, K. (2017, 11). Sustainability of terraced paddy fields in traditional satoyama landscapes of Japan. Journal of Environmental Management, 202, 543-549. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.11.061.

Gourmelon, G. (2015, January 27). Global Plastic Production Rises, Recycling Lags [PDF]. Washington, D.C.: Worldwatch Institute.

Lavender Law, K. (2016, September 7). Plastics in the Marine Environment [PDF]. Woods Hole, Massachusetts: Sea Education Association.

Miyazaki, H. (Director). (1988). My Neighbour Totoro [Motion picture on DVD].

Miyazaki, H. (Director). (1997). Princess Mononoke [Motion picture on DVD].

Miyazaki, H. (Director). (2008). Ponyo on a Cliff by the Sea [Motion picture on DVD].

Mumcu, S. & Yılmaz, S. (2010). THE LANDSCAPE OF MIYAZAKI; ENVIRONMENTAL CHARACTERISTICS AND MESSAGES.

Mumcu, S. & Yılmaz, S. (2018). Anime Landscapes as a Tool for Analyzing the Human-Environment Relationship: Hayao Miyazaki Films. Arts. 7(2). 10.3390/arts7020016.

NRTEE. (2011). PAYING THE PRICE: THE ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE FOR CANADA [PDF]. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy.

OregonForests.org. (n.d.). Sustainable Management.Retrieved February 18, 2019, from https://oregonforests.org/content/sustainability.

Running, K. (2015, 03). Towards climate justice: How do the most vulnerable weigh environment–economy trade-offs? Social Science Research, 50, 217-228. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.11.018.

Schlosberg, D., & Carruthers, D. (2010, 11). Indigenous Struggles, Environmental Justice, and Community Capabilities. Global Environmental Politics, 10(4), 12-35. doi:10.1162/glep_a_00029.

Smith, M. J. & Parsons, E. (2012, 01). Animating child activism: Environmentalism and class politics in Ghibli's Princess Mononoke (1997) and Fox's Fern Gully (1992). Continuum, 26(1), 25-37. doi:10.1080/10304312.2012.630138.

Thevenin, B. (2013, 10). Princess Mononoke and beyond: New nature narratives for children. Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture, 4(2), 147-170. doi:10.1386/iscc.4.2.147_1.

US EPA. (2014, May). A Closer Look: Land Loss Along the Atlantic Coast. Retrieved February 18, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/atlantic-coast.

US EPA. (2016, August). Climate Change Indicators: Ocean Heat. Retrieved February 18, 2019, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-ocean-heat .

Yamanaka, H. (2008). The utopian ‘Power to Live’; The significance of the Miyazaki Phenomenon. In MacWilliams, Mark W. (Editor); Schodt, Frederik L. (Foreword by). Japanese Visual Culture : Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime. Armonk, NY, USA: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., p 237-255.

Yokohari, M. & Bolthouse, J. (2010). Keep it alive, don’t freeze it: A conceptual perspective on the conservation of continuously evolving satoyama landscapes. Landscape and Ecological Engineering,7(2), 207-216. doi:10.1007/s11355-010-0116-1.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Since the emergency of COVID-19, National response to the pandemic has halted access to essential health services in different government hospitals across the country as experienced by patients. As a country, we must organized our healthcare system for continuous provision of equitable access to essential service delivery throughout the COVID-19 emergency in order to limit direct mortality and avoid increased indirect mortality from non-COVID-19 illness. #AccessToHealthcare #RightToHealth #HealthForAll #COVID19Nigeria #Nigeria (at Nigeria) https://www.instagram.com/p/CCdl2nVppDt/?igshid=17vnmbl4fqg4p

0 notes