#The Scriptures 2009

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Lord, How Faithful You Are!

The loving-commitments of יהוה! For we have not been consumed, For His compassions have not ended.

They are new every morning, Great is Your trustworthiness. — Lamentations 3:22-23 | The Scriptures 2009 (TS2009) The Scriptures 2009 Copyright © 2009 Institute for Scripture Research. All Rights reserved. Cross References: Psalm 78:38; Psalm 89:1; Psalm 103:10; Isaiah 33:2; Jeremiah 3:12; Hebrews 10:23

Read full chapter

What does it mean that God’s mercies are new every morning (Lamentations 3:23)?

#Lord#God#faithfulness#love#praise#compassion#renewal#morning#Lamentations 3:22-23#Book of Lamentations#Old Testament#TS2009#The Scriptures 2009#Institute for Scripture Research

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clothe yourself with wisdom like a robe, put knowledge on yourself like a crown, and be seated upon a throne of perception.

— THE TEACHINGS OF SILVANUS ⚜️ The Nag Hammadi Scriptures: The Revised and Updated Translation of Sacred Gnostic Texts (Ed. Marvin Meyer), (2009)

#Collected Texts#Sacred Texts#Gnosticism#Silas#Silvanus#The Teachings of Silvanus#The Nag Hammadi Scriptures#The Revised and Updated Translation of Sacred Gnostic Texts#Marvin Meyer#(2009)

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

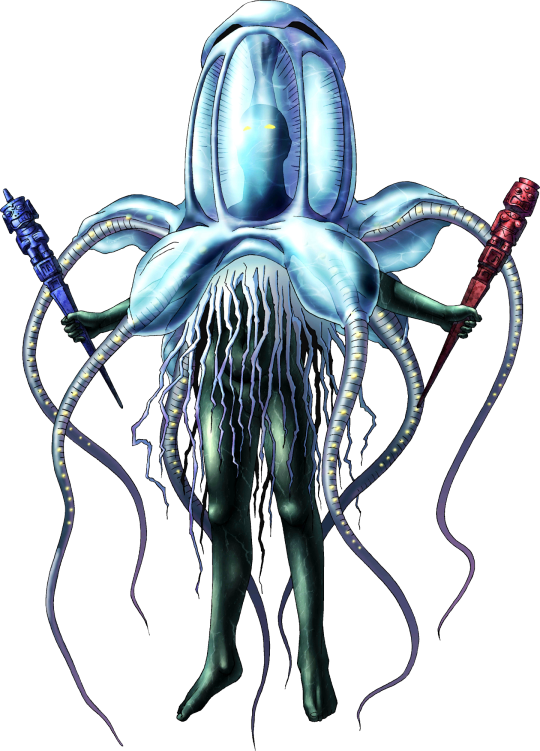

A case of twice-mistaken identity: on “Asherah” in Strange Journey

In 2009, Atlus released one of their most unique games to date - Strange Journey, an rpg set in a deliberately unrealistic setting in which demons exist, while the UN does something beyond issuing a non-binding resolution in the face of crisis. In contrast with many of the previous SMT installments, Strange Journey only introduced a handful of new demons. They were some of the last designs Kazuma Kaneko provided for the franchise, but most of them became instant fan-favorites, sparking a veritable avalanche of fanart (by Megaten demon standards, at least) and endless discussion. Going by the raw numbers on pixiv and similar sites, the consensus view seems to be that the standout among them is the “protagonist” of this article, seen above. The English translation of the game, as well as official English translations of all subsequent Megaten media, opted to romanize the name of the discussed entity as Asherah. I have a strong reason to suspect this is wrong, and that “Asherah” is not who most of us assumed she is on this basis. In this article, I will explain the origin of the term asherah and examine if it was ever the name of a deity. I’ll also look through its cognates in multiple languages. Finally, every Megaten fan’s favorite fringe tome will be consulted for additional hints. As a result, the true identity of “Asherah” shall be revealed.

“A horrid thing”: the asherah in the Bible and related sources

The term asherah appears in the Bible, though it’s actually up for debate if it can be interpreted as the name of a deity (Steve A. Wiggins, A Reassessment of Asherah With Further Considerations of the Goddess, p.105). Ignoring occasional modern attempts at emending passages which do not require that, it occurs forty times in scriptural sources (A Reassessment…, p. 110). Nearly all of them point to the asherah being some variety of cultic object. In some cases a plural form is given, though the grammatical gender is inconsistent, with examples of both asherot (Judges 3:7) and asherim (1 Kings 14.23; 2 Kings 17.10; 23.14). The masculine variant is more common, which makes it unlikely the singular form was particularly commonly viewed as a feminine noun - unless, perhaps, the compilers considered an intentionally ungrammatical plural some sort of irony (A Reassessment…, p. 110-111).

Most of the references are fairly formulaic, and occur in passages from books belonging to the tradition of “Deuteronomistic History” explaining why Yahweh became angry with the kingdoms of Israel and Judah. In those cases the anger appears to be tied to placing one or more asherah in the proximity of an altar. Based on the fact that an asherah could be planted, and destroying it was typically accomplished by burning or hewing, most likely they should be understood as wooden objects (A Reassessment…, p. 111-112). Nothing more can be established with certainty, and in absence of precise descriptions labeling any objects recovered from excavations as examples just because they’re wooden should be avoided (A Reassessment…, p. 261).

A possible reference to Asherah understood as a foreign deity might be present in 1 Kings 18:19, where “400 prophets of Asherah” are among Jezebel’s associates singled out by the prophet Elijah (A Reassessment…, p. 127-129). However, it is implausible that this reflects historical reality. Jezebel hailed from Tyre and no deity bearing an even barely similar name is attested in the local pantheon of Tyre - or, for that matter, in any other Phoenician city in the Iron Age (Spencer J. Allen, The Splintered Divine. A Study of Ištar, Baal, and Yahweh. Divine Names and Divine Multiplicity in the Ancient Near East, p. 280).

A further example might be 2 Chronicles 15:16, where at least according to the Masoretes Asherah is used as a personal name. The passage deals with the deposing of queen mother (gebirah) Maakah by king Asa of Judah after she created an unspecified “horrid thing” for Asherah - or, if the Masoretes were incorrect, perhaps created an asherah, a “horrid thing”, for herself (A Reassessment…, p. 125-126).

Rabbinic tradition generally considers the asherah to be a type of tree (A Reassessment…, p. 148-149). Similarly, the Septuagint (and by extension other translations derived from it) renders the plural form of this term as “groves” (A Reassessment…, p. 269). While especially in the 1990s it was common to argue that the hypothetical namesake goddess must have been some sort of tree deity as a result (A Reassessment…, p. 239), no evidence in favor of this interpretation is available (A Reassessment…, p. 261-263). In the end, the supposed arboreal Asherah is little more than a result of overinterpreting a historical guess about the meaning of a term whose original context was entirely lost by the first centuries CE (A Reassessment…, p. 269).

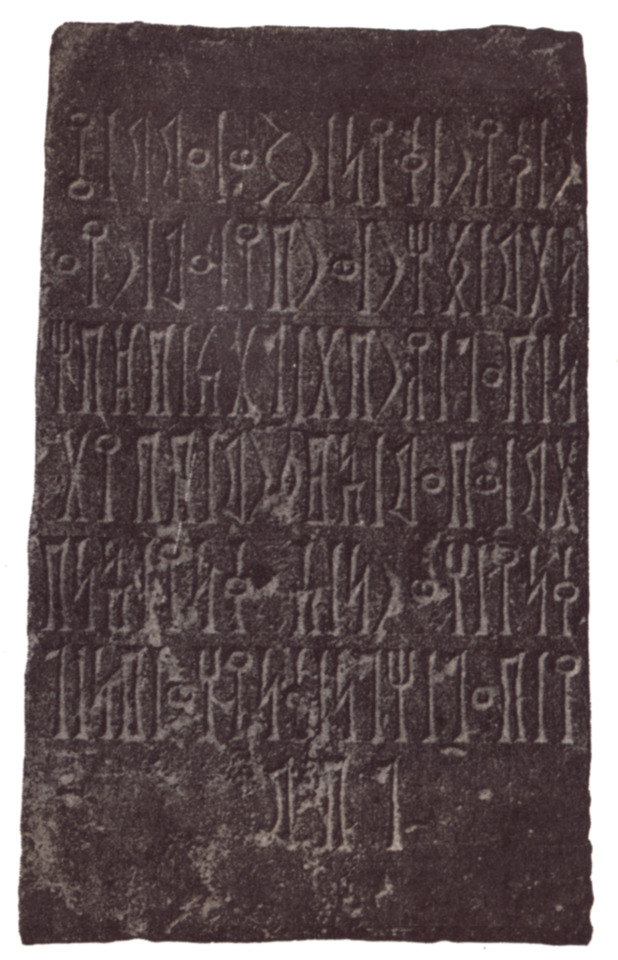

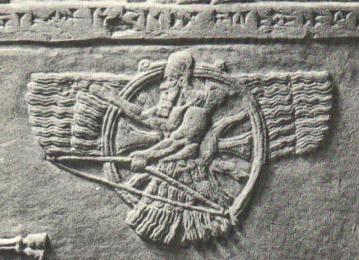

A decorated pithos from Kuntillet Arjud (wikimedia commons)

As far as extrabiblical materials go, the most relevant source offering some further hints about asherah are two early first millennium BCE Hebrew inscriptions from Kuntillet Ajrud in Egypt which mention blessing someone by “Yahweh of Teman and his asherah” and “Yahweh of Samaria and his asherah” (The Splintered Divine…, p. 265). It’s up for debate if “Yahweh of Samaria” and “Yahweh of Teman” were understood as two fully separate deities - the way, say, Ishtar of Nineveh and Ishtar of Arbela were in Mesopotamia - or simply as two regional manifestations of the same deity (The Splintered Divine…, p. 272). The fact that similar formulas find no other parallels in any other texts in Hebrew doesn’t help (A Reassessment…, p. 204). This is ultimately outside the scope of this article, though.

What matters for the discussed subject is that the original publication of the Kuntillet Ajrud material in 1979 sparked what by the early 2000s came to be referred as an “Asherah boom” or “Asherah craze” (Izak Cornelius, The Many Faces of the Goddess: The Iconography of the Syro-Palestinian Goddesses Anat, Astarte, Qedeshet, and Asherah c. 1500-1000 BCE, p. 3).

Crucially, the inscriptions were commonly held as evidence that Yahweh had a wife, and that she was named Asherah (A Reassessment…, p. 190). Nothing explicitly indicates that their authors considered asherah to be the name of a goddess, though (The Splintered Divine…, p. 309).

It is entirely possible that the familiar wooden cultic object is meant (A Reassessment…, p. 198). We might be dealing with a formula similar to Eliezer’s considerably later) invocation of the altar of the Second Temple alongside Yahweh, which obviously does not indicate that he treated a piece of furniture as an independent deity (The Splintered Divine…, p. 309). It might also be worth noting that an asherah was made for Yahweh in Samaria under king Omri’s orders, according to 1 Kings 16:33 (The Splintered Divine…, p. 278).

It should be noted that while one of the inscriptions is accompanied by a drawing (as seen on on the illustration above), it is unlikely to be related to its contents (A Reassessment…, p. 199-200).

It has been argued that a further reference to “Yahweh and his asherah” occurs in a roughly contemporary funerary inscription found in Khirbet el-Qôm in the West Bank, though the poor preservation of the text makes any translations tentative. It cannot thus be used to argue even for a link between Yahweh and the cultic object asherah, let alone for the existence of a goddess named Asherah (A Reassessment…, p. 190-196). It has been argued that it is effectively a Rorschach test of sorts for a given author’s views about the asherah and Asherah (A Reassessment…, p. 274). Ultimately it’s difficult to evaluate if Yahweh ever had a wife, let alone if that wife was named Asherah. If that was the case, it’s hard to disagree that the archeological evidence is beyond sparse, though (A Reassessment…, p. 281).

Looking at material from other nearby areas from the first millennium BCE does not provide any further evidence for a goddess named Asherah. The Phoenician term ʾšrt, which is likely a cognate of asherah, has a handful of attestations (one inscription each from Umm El-Amed, Acre and Pyrgi), but invariably refers to a place - presumably a (type of) shrine or sanctuary - not to a goddess (A Reassessment…, p. 212-214). An alleged Phoenician attestation of Asherah on an amulet from Arslan Tash seems to actually be a reference to the Assyrian head god Ashur, and the object might be a forgery anyway, which would render it virtually worthless as a source (A Reassessment…, p. 210-212).

The supposed Aramaic evidence is even more flimsy. An alleged reference to Asherah (ʾšyrʾ) on a fifth century stela from Tema turned out to be a misreading, with a local deity named ʾšymʾ actually meant. A stela from Sefire does affirm that a cognate, ʾsrt, was used to designate a type of sanctuary, much like in Phoenician, though (A Reassessment…, p. 214-215).

“Lady of the sea”: Athirat in Ugarit

If the evidence for the biblical asherah being a theonym, rather than a term, is flimsy at best, where does the idea that a deity with an identical name existed? To find an answer, we need to travel a few centuries further back than the oldest material discussed in the previous section.

In the early twentieth century, excavations in Ras Shamra in nothwestern Syria revealed that this site was originally a Bronze Age city, Ugarit - and that the local pantheon included Athirat, whose name was suspiciously close to a biblical term for some sort of cultic implement (A Reassessment…, p. 225).

It needs to be stressed that the information from Ugarit cannot be transferred to areas further south in different time periods (The Many Faces…, p. 18). Also, in particular the labeling of Ugarit as “Canaanite” - very common online - should be avoided. It was not located in Canaan - this label only applied to the area more or less from Byblos to Gaza (The Many Faces…, p. 8); it belonged to the circle of Amorite culture (Dennis Pardee, Ritual and Cult at Ugarit, p. 236).

With that in mind, let’s look at Athirat. Her name is undeniably a cognate of the biblical term and its Phoenician and Aramaic analogs. It might very well be that the word originally meant “holy place” or “sanctuary”, and that a theonym developed from it, rather than the other way around (A Reassessment…, p. 221-222). It’s worth stressing right away that Ugarit provides by far the most references to any of the cognate terms which are the subject of this inquiry - Athirat is, ultimately, better attested than asherah (A Reassessment…, p. 105).

Tablet with a section of the Baal Cycle (wikimedia commons)

Athirat is arguably best known from, and most prominent in, the Baal Cycle (A Reassessment…, p. 33). She first appears in the section dealing with the conflict between Baal and Yam, the sea god, though her precise role in the relevant passage is uncertain. She might be involved in providing Yam with a new name or title (A Reassessment…, p. 34-42). Her role in the second of the three sections, which deals with the construction of a palace for Baal, is much better understood. Baal and his ally Anat convince her to mediate with El, her husband, so that Baal can have a house built for himself. Athirat doesn’t appear to be fond of them (in fact, at first she assumes they want to fight her), and convincing her requires numerous gifts provided by the craftsman god Kothar-wa-Khasis. It’s possible Yam, despite already being defeated by Baal earlier, is also present in this scene, and that Athirat temporarily restrains him with a net while her negotiations are ongoing (A Reassessment…, p. 42-74). Athirat makes her final appearance in the third part of the cycle, in which Baal temporarily dies at the hands of Mot. The implied hostility between her and Baal seemingly resurfaces, as Anat remarks that she will surely rejoice after hearing about his untimely demise. El tasks her with appointing a replacement, which she promptly does, choosing Attar to act as a new king of the gods. She seems to be so enthusiastic about this that it has been suggested that it is this opportunity to show off her position this way that’s the cause of her good mood, as opposed to Baal’s death (A Reassessment…, p. 75-77). Athirat’s role is overall less prominent in other literary texts in which she appears. These include the Epic of Keret (A Reassessment…, p. 25-33); Shachar and Shalim (A Reassessment…, p. 86-92); and a variety of shorter or fragmentary compositions (A Reassessment…, p. 92-98). She only occurs with a limited frequency in sources tied to the sphere of cult (A Reassessment…, p. 274).

While none of the Ugaritic texts make that explicit, it can be safely assumed that Athirat was regarded as the wife of El, the head of the pantheon (The Many Faces…, p. 99). Nothing indicates she played this role vis a vis Baal (A Reassessment…, p. 84). The only cases where they occur side by side are offering lists, and this is ultimately as informative when it comes to determining the connection between them as a modern church named jointly after, say, St. Andrew and St. George is for establishing the personal connections of the respective saints (A Reassessment…, p. 101)

El and Athirat have a variety of matching titles, designating them as senior members of the pantheon and creator deities - while El is the “father” and “creator” of the gods, Athirat is accordingly the “mother” and “creatress” (Aicha Rahmouni, Divine Epithets in the Ugaritic Alphabetic Texts, p. 331). The former title only appears once in the entire corpus (Divine Epithets…, p. 73), the latter - six times (Divine Epithets…, p. 276-277).

It needs to be stressed that the “maternal” titles do not designate Athirat as some sort of Frazerian “Great Mother”. They are a reflection of status: she is a creator deity, and a senior member of the pantheon, but not some transcendent all-encompassing ur-mother (A Reassessment…, p. 237). Simply put, she does not represent the popcultural image of a “mother goddess” (A Reassessment…, p. 83-84; The Many Faces…, p. 99).

It is perhaps best to describe Athirat as the divine counterpart of a queen mother, going by her portrayal in the Baal Cycle, especially her role in the appointment of a new king of the gods. It has been argued that her title rbt might specifically reflect this role, judging from the context in which its Akkadian cognate rabītu was used in Ugarit (A Reassessment…, p. 77-78). However, since the sun goddess Shapash is also designated as a rbt, this might be incorrect, at least as far as epithets of deities go (Divine Epithets…, p. 281-282). Athirat’s high status is also reflected by her placement in a trilingual god list based on the Mesopotamian Weidner god list, with Hurrian and Ugaritic columns added. It establishes an equivalence between her, Ninlil and “Ašte Kumurbineve” (Aaron Tugendhaft, Gods on Clay: Ancient Near Eastern Scholarly Practices and the History of Religions, p. 175). The former’s character was similar. She was the wife of a pantheon head, and the epithets highlighting her status similarly refer to her as the “mother” (ummi) or “creatress” (bānīt) of the gods (Divine Epithets…, p. 73). The latter is actually a pure scribal invention, though - the name simply means “Kumarbi’s wife”. No such a goddess was actually worshiped anywhere, she was invented entirely for completeness’ sake (Gods on Clay…, p. 177-178).

Yam (“Ym”), as portrayed in Shin Megami Tensei (MT wiki, via VeskScans)

Seniority is not Athirat’s only characteristic. Her most common epithet is actually “lady of the sea”, which occurs twenty-one times total - all of those attestations are from the Baal Cycle, though (Divine Epithets…, p. 281). While it contains the same word for sea - ym - as the one which doubled as a theonym, it is agreed that an ordinary body of water is meant in this case, not the sea god par excellence, Yam (Divine Epithets…, p. 284-285). Steve A. Wiggins suggests that the title might be a reference to some hitherto unknown tradition about Athirat’s origin, as opposed to an indication of involvement in unspecified marine matters. While this proposal is interesting, it ultimately remains entirely speculative (A Reassessment…, p. 273). Athirat’s presumed association with the sea might explain why a minor deity consistently described as her servant, Qudshu-wa-Amrur, is addressed as her fisherman (Divine Epithets…, p. 150-151). A further deity defined by a connection to Athirat is Dimgay, her handmaiden, though she is much more sparsely attested (and has no aquatic associations). In the sole text to mention her she is paired with Tallish, who fulfills an analogous role in the court of the moon god Yarikh (Divine Epithets…, p. 78-79).

Excursus 1: the illusory triple A goddess(es)

Anat (right) and her #1 fan, pharaoh Ramses II (wikimedia commons)

While Athirat’s connections with El and with her servants are well documented, a common misconception, repeated especially commonly in older scholarship, but also online, is that she, Anat and Ashtart were associated with each other so closely they basically formed a group. As an extension, the three of them are presented as the only major goddesses in Ugarit (and beyond). However, this grouping is both modern and entirely artificial. It’s worth noting that as far as the Ugaritic evidence goes, Shapash, the sun goddess, was actually comparably, if not more, important as Ashtart (A Reassessment…, p. 230).

Nonetheless, at least among Bible scholars it’s possible to find examples of complete and utter credulity leading to presenting Athirat, Anat and Ashtart as not just closely related, but somehow interchangeable (A Reassessment…, p. 283). Typically questionable publications aim to present Athirat and Ashtart as somehow identical or at least conflated with each other. This is based entirely on the superficial similarity of their Romanized names - they were not very similar in Ugaritic, seeing as one begins with an aleph and the other with an ayin. Ashtart doesn’t even appear in parallel with Athirat; if she is paired with another goddess, it’s Anat (A Reassesment…, p. 57). However, while Anat and Ashtart did share multiple characteristics, even they were not conflated with each other (The Many Faces…, p. 100), let alone with Athirat.

A typical depiction of Qadesh (middle), accompanied by Min (left) and Resheph (wikimedia commons)

Despite lacking any strong foundation in reality, the “triple A” misconception managed to influence early scholarship pertaining to a fourth deity - one who doesn’t even have anything to do with Ugarit, at that. Starting with the 1930s, the idea that the goddess Qadesh must be one and the same as “Asherah” arose. This rested on two far reaching conclusions: that if Qadesh appears with Anat and Ashtart in a single inscription, she must be a foreign goddess of comparable importance; and that qdš (“blessed”) was an epithet of Athirat in Ugarit (A Reassessment…, p. 226).

The first problem is that the sole source to group Qadesh with Anat and Ashtart - the so-called Winchester College stela - is nowhere to be found today. It has been lost at least since the 1990s, if not earlier (A Reassessment…, p. 229). It’s not entirely impossible that it was a fake, since back when it was still accessible to researchers in the 1950s it has been pointed out that the artist had an oddly poor grasp of the hieroglyphic script (The Many Faces…, p. 95).

There is also no evidence that qdš was a title of Athirat (A Reassessment…, p. 226). It does occur as a title of El in the Epic of Keret, though, and is actually grammatically masculine (A Reassessment…, p. 227). Alas, I don’t think anyone is bold enough to suggest Qadesh is El’s drag persona.

A further issue is that while no certain examples of depictions of Athirat have been identified, textual sources indicate she would in all due likeness look considerably less youthful than Qadesh does (The Many Faces…, p. 100). Considering all of these serious obstacles, it should come as no surprise that identifying Qadesh as Athirat largely fell out of favor by the early 2000s (The Many Faces…, p. 95). The modern consensus is that she actually wasn’t fully an “imported” deity in Egypt in the first place, in contrast with Anat and Ashtart. Her name does go back to the root qdš, but she was invented in Egypt (Christiane Zivie-Coche, Foreign Deities in Egypt in the UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, p. 5-6).

Qadesh is first attested during the reign of Amenhotep III (1389-1349 BCE), already in a firmly Egyptian context, on a statue of a certain Ptahankh, an inhabitant of Memphis and affiliate of the priesthood of Ptah (Foreign Deities…, p. 3). It is also known that a temple dedicated to her existed in this city. Her firm position in ancient Egyptian religion is also presumably reflected in epithets such as self-explanatory “eye of Ra” and “great of magic”, a designation for goddesses linked to the pharaoh’s crown in one way or another (The Many Faces…, p. 96). She may or may not have been a love goddess, but no strong evidence in favor of this view exists (The Many Faces…, p. 97).

“Mistress of voluptuousness and joy”: Ashratum in Mesopotamia

While the notion of an association between Ugaritic Athirat and Qadesh is ultimately erroneous, she does have a “relative” who can be considered at least superficially similar: the Mesopotamian goddess Ashratum. While Ashratum can be effectively considered a derivative of Athirat (or, perhaps, a more divergent descendant of a common ancestor), it needs to be stressed that her character differed considerably (A Reassessment…, p. 219). Needless to say, information pertaining to her cannot be randomly applied to Athirat (A Reassessment…, p. 153).

Itūr-ašdum‘s votive inscription (wikimedia commons)

Her character is perhaps best exemplified by the most famous primary source dealing with her, a votive inscription invoking her dedicated to Hammurabi of Babylon (reigned c. 1792–1750 BCE) by a certain Itūr-ašdum. This text describes her as the “lady of voluptuousness and happiness” (A Reassessment…, p. 155-156). This title may or may not hint at involvement in the erotic sphere (A Reassessment…, p. 158). The same term translated her as “voluptuousness” - ḫili - also appears in the ceremonial name of her temple in Babylon, Eḫilikalamma - something like “house of voluptuousness of the land (A Reassessment…, p.163).

As far as I am aware, no study offers a good explanation for why Ashratum came to be associated with the qualities reflected in her title and the name of her temple. However, it has been securely established that her other Mesopotamian characteristics stemmed from her close association with the god Amurru, who was regarded as her husband (A Reassessment…, p. 219). It presumably reflected her own Amorite origins (A Reassessment…, p.153). Amurru (“the Amorite god”) was effectively a personified stereotype - the archetypal nomadic simpleton unfamiliar with urban life, a reflection of the Mesopotamian perception of Amorites arriving from the west (Paul-Alain Beaulieu, The God Amurru as an Emblem of Ethnic and Cultural Identity, p. 33-34). Textual sources indicate that his attribute was a crooked staff (gamlu), possibly originally associated with Amorites on the account of their pastoral lifestyle (The God Amurru…, p. 35-36). To put it in modern terms: you could compare him to a cartoony redneck or hillbilly, complete with a banjo and a jug of moonshine. Except people actually built temples dedicated to him, named children after him, and for all intents and purposes treated him as a valid, if not particularly major, member of the pantheon (The God Amurru…, p. 41-43).

As Amurru’s spouse, Ashratum could be referred to as “tenderly cared for in the mountains”. This is implicitly supposed to be understood as “cared for by Amurru”, seeing as he was regularly referred to as the “lord of the mountains”, bēl šadi (A Reassessment…, p. 158). He could simply be treated as an inhabitant of mountainous areas, though it’s possible his association with this environment doubled as a pun of sorts. The cuneiform sign KUR could be used to write both the word “steppe” (where one would expect to find migrating nomads) and “mountain” (The God Amurru…, p. 38-39).

Amurru’s connection similarly applied to his spouse, and is also reflected in their matching epithets - Amurru was the “lord of the steppe”, bēl seri, while Ashratum accordingly could be called belet seri, “lady of the steppe” (The God Amurru…, p. 38). It should be noted there was another, unrelated Belet-seri, who acted as Ereshkigal’s scribe - seri in this case being understood as an euphemism for the underworld (more about her in my next article). I’m not aware of any cases where the two were confused, barring a possible indirect example - Amurru apparently occasionally appears in the company of some of the goddesses who could be identified as Ningishzida’s wife; and the latter role could be fulfilled by Geshtinanna, who was regularly identified with Ereshkigal’s Belet-seri (Andrew R. George, House Most High. The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia, p. 37-38). Given the expected difference in demeanor, it is a shame no source has the two belet-seris interact.

The association with Amurru is also why Ashratum could be called the “daughter-in-law of Anu”, the sky god and Amurru’s father. Online an incredibly antiquated interpretation seems to be spreading up to this day (including in Megaten context), with Ashratum misinterpreted as Anu’s spouse. This is the result of a misunderstanding: in both Sumerian and Akkadian, the term “daughter-in-law” (egia/kallatum) can also designate a bride. That simply reflects the fact that typically a father would pick his son’s wife, though - there’s no ambiguity whose spouse Ashratum is supposed to be (A Reassessment…, p. 157-158). Interestingly, a single unique source would indicate that in addition to the happy-go-lucky Ashratum at least some people in the south were aware of her “relative”. A unique Amorite-Akkadian bilingual lexical list published recently explains a-še-ra-tum as DIĜIR.MAḪ, ie. Bēlet-ilī, the "queen of the gods" (Andrew George, Manfred Krebernik, Two Remarkable Vocabularies: Amorite-Akkadian Bilinguals!, p. 115). On textual grounds, it was dated to the Old Babylonian period, specifically to the times of Rim-Sin I and Hammurabi (Two Remarkable…, p. 113). Based on the character of the goddess listed as the Akkadian “explanation” of the name (which you can guess from its meaning), it can be safely assumed that in this case the same deity as in Ugarit is meant - a senior, “respectable” goddess (Two Remarkable…, p. 118).

YBC 2401, the most complete copy of An = Anum discovered so far (Electronic Babylonian Library; reproduced here for educational purposes only) On the opposite end of the spectrum, the considerably later An = Anum appears to treat Ashratum’s section as little more than a wastebasket for any feminine western theonyms, including, inexplicably, Anat (Wilfred G. Lambert, Ryan D. Winters, An = Anum and Related Lists, p. 26). Note she has her own entry in the Amorite-Akkadian bilingual (Two Remarkable…, p. 115). In Ugarit, the trilingual list transcribes her name phonetically in the Hurrian column, and lists (distinctly male) Sagkud as her Mesopotamian counterpart - not Ashratum (Gods on Clay…, p. 176). Interestingly, since Ashratum appears in the original Weidner god list it can be assumed that scribes from Ugarit would be familiar with her thanks to the import of this source. Sadly, we have no clue what they thought about her and her Mesopotamian spouse (A Reassessment…, p. 161).

Excursus 2: odds and ends

A few other names cognate with the biblical asherah, Athirat and Ashratum are not attested well enough to warrant separate sections of their own.

A letter from Tell Taanach in Palestine written in Akkadian (the diplomatic lingua franca in the second half of the second millennium BCE) mentions a deity named Ashirat. This is most likely a reference to the same goddess as the one known from Ugarit. However, the text provides no detailed information about her - it only mentions a cultic specialist in her service in passing (A Reassessment…, p. 170-171). A ruler of Ugarit’s southern neighbor, the kingdom of Amurru, bore the theophoric name Abdi-Ashirta, “servant of Ashirta”. The variant form Abdi-Ashratum is also attested, so we are pretty clearly dealing either with another form of the name of one of the previously discussed goddesses, or a further deity with a cognate name. The matter is complicated by the fact that multiple times the name is written with typos by Egyptian scribes with only a rudimentary understanding of cuneiform, though (A Reassessment…, p. 168-169).

An apparent Hittite adaptation of the Ugaritic Athirat, Asherdu (sic), is attested exclusively in a short myth in which she and her partner in crime Elkunirsa (an adaptation of El, as you can probably guess) plot against a weather god of uncertain identity. The last of these characters clearly takes Baal’s role, but his precise identity cannot be established, as he’s only referred to with a generic logogram which could designate different weather gods, not with a given name. The entire composition might be based on some hitherto unknown southern forerunner, but not much can be said about its development beyond that (A Reassessment…, p. 172-175).

An example of Qatabanian script (wikimedia commons); no relation to cuneiform.

Finally, a handful of references to a more distant “relative”, Athrat, have been identified in texts from the kingdom of Qataban in Yemen dated to the second half of the first millennium BCE; she is thus separated from Athirat, Ashratum et al. by both a temporal and spatial gulf (A Reassessment…, p. 187). The available sources don’t provide much information about her. Two mention a temple she shared with Wadd, a local moon god, while another relays she received offerings alongside ‘Amm, the national god of the kingdom of Qataban (and possibly also a moon god). The nature of the precise connection between her and those two, and in particular whether she might have been viewed as the spouse of either of them, or even both (perhaps in different locations within the kingdom), is a subject of debate (A Reassessment…, p. 180-181). If she was, she might have been viewed as a solar goddess, though that remains uncertain (A Reassessment…, p. 186). The fact that it’s possible in some of the Qatabian inscriptions a structure is meant, and not a goddess, does not help much with the evaluation of the scarce evidence (A Reassessment…, p. 177-178).

“Genital center”: Asherah according to Barbara G. Walker

The Japanese edition of Walker's book (via an expired online listing with an asking price of 600+ USD [sic]; reproduced here for educational purposes only)

The previous sections more or less summarized what actual scholarship has to say about the term asherah and its cognates. However, with Megaten being Megaten, this is insufficient . No inquiry is complete without also consulting Atlus’ favorite publication: Barbara G. Walker’s magnum opus The Woman's Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets.

Evidently not only Atlus is enamored with her writing - it has influenced a number of other popular Japanese franchises, especially Fate. It also has overwhelmingly positive reviews on Goodreads. There is a non-trivial number of people out there who find it credible, despite the author’s complete lack of relevant credentials, poor sourcing, and questionable at best methodology. Ironically, I have a strong suspicion that Walker herself might no share this view. I’d hazard a guess that this tome - and Walker’s numerous other less discussed New Age publications, including such smash hits as I-Ching of the Goddess - are a cynical grift, since she describes herself as an atheist elsewhere (sic). I digress though.

Walker’s book contains a total of 29 references to Asherah. She gets her own separate entry, but it surprisingly only occupies one page. To be fair, we have to bear in mind that in the early 1980s, when the book was written, the “Asherah boom” was only starting. Most of the entry is not particularly unique, and is limited to Bible-based speculation from before the discovery of the “Yahweh and his asherah” inscriptions, with a dash of Ugarit. Walker basically subscribes to the notion of a “tree goddess” wholesale, and adds that clearly the “groves” were a metaphor for Asherah’s “genital center”. She had to throw in something uniquely baffling, though, and speculates the name Asherah somehow goes back to Old Iranian asha, which she translates as “universal law” (for the actual meaning of this term, consult Encyclopedia Iranica). Further, she connects her with Isis at random, and asserts she was worshiped in Thebes as a result (The Woman’s…, p. 66).

Elsewhere in the book Walker simply rehashes questionable dated scholarship of the sort already discussed earlier. She proclaims Asherah and Baal a couple (The Woman’s…, 85); in Anat’s entry she treats her and Asherah as interchangeable and, inexplicably, also as the goddess of Jerusalem (The Woman’s…, p. 30). Astarte gets similar treatment (The Woman’s…, p. 69). This identification also gets an extended version which includes Aphrodite and Lucian’s Dea Syria as bonuses (The Woman’s…, p. 44). As far as I am aware, the identification with Aphrodite is a Walker original. She liked it so much it also pops up in Adonis’ entry, where she explains he was paired with “Aphrodite or Asherah” in Mesopotamian Mari (The Woman’s…, p. 10). This sort of complete disregard for temporal (Mari ceased to exist in Hammurabi’s times) and linguistic rigor is a mainstay of her work. Interestingly, Walker appears to be entirely unfamiliar with Ashratum, and instead asserts that the Mesopotamian counterpart of “Asherah” was Ashnan. She describes this name as Sumerian (The Woman’s…, p. 66). In reality, Ashnan’s name is Akkadian and means “grain”; the same goddess’ Sumerian name was Ezina - which, as you can imagine, also means “grain” (Julia M. Asher-Greve, Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, p. 41). Needless to say, she had nothing to do with Ashratum.

Conclusions: Asherah, Athirat, or Ashratum?

With both the credible and questionable sources summarized, it is time to finally try to figure out who the “protagonist” of this article is supposed to be.

The translators of Strange Journey evidently concluded they’re dealing with the sort-of kind-of biblical figure. The assumption that’s who “Asherah” is supposed to be is common among English-speaking fans, and recently made it to her entry on the new Megaten wiki, which proclaims the discussed entity was “depicted as the wife of (...) Yahweh” (which, as I already pointed out, is at best a theory). As some of you might remember, in the past even I accepted it, and it was quite surprising to me that Atlus - with the well known love of dubious material, and a penchant for making everything revolve around YHVH which if anything only grew in more recent instalments - did nothing with this in Strange Journey. Or in any other game, for that matter.

I think the answer why that never happened is simple: “Asherah” was never meant to be who the romanization made her. It’s a case of mistaken identity.

As demonstrated on the screencap above, the name used in the original game, as well as in SJR and subsequent SMT installments, is spelled as アシェラト in katakana. A quick search will demonstrate that the biblical term is actually rendered as アーシラト - that’s the spelling Japanese wikipedia uses, for instance.

Who is アシェラト, then?

While this might not be evident at first, apparently the conventional Japanese spelling of Ugaritic Athirat. Japanese Wikipedia claims so outright, though without providing sources. However, I think we can trust it in this case. Most of the relatively few non-Megaten results for アシェラト appear to come from Ugarit hobbyists, here is just one example; I can vouch for this person’s credibility, they are pretty clearly well acquainted with the primary sources and relevant scholarship.

This impression that Athirat, not Asherah, was the intended name is further strengthened by the romanization of the name used in Shin Megami Tensei Series 25th Anniversary Memorial Book: MegaTen Maniacs, a book released as a bonus with a limited edition of Strange Journey Redux (p. 133; thanks to @purseowner4thequalityanimation for directing me to it!):

This is far cry from Asherah, but remarkably close to the non-vocalized form of the Ugaritic Athirat’s name, aṯrt. However, the name is not all. The compendium entries also provide some clues. Her original one describes her as “a Semitic goddess who was the one to bring fertility to the Babylonian lands. She is known as the mother of the gods. It is believed that in Phoenicia, she became Astarte.” I’m not a huge fan of implying there ever was such a thing as a “Semitic pantheon” - only languages can be described as “Semitic”, deities, let alone a “religion”, not really (Michael P. Streck, Semites, Semitic in RlA vol. 12, p. 386-387) - but the information, by Megaten standards, is relatively rigorous. We get a mix of Ugaritic Athirat (“mother of the gods”) and Mesopotamian Ashratum (explicit reference to Babylonia), with the questionable conflation with Ashtart (Astarte is simply the Greek spelling of this name) I mentioned thrown in for good measure. No references to the Bible or the inscriptions which sparked the “Asherah boom” are present, though.

Perhaps most curiously, even if not ideal, the sources consulted were clearly of much higher quality than Woman’s Encyclopedia - which, in fact, seemingly didn’t have any impact on Asherah’s bio. Mashing Ashratum and Athirat together is questionable, much like mashing together, say, Zeus and Tyr based on the shared origin of their names would be, but it’s miles ahead of many other choices made by Atlus. SMT IV didn’t change much. She appears in an NG+ quest which presumably reflects Atlus’ love for unnecessary equations - in this case with Ishtar. The less said about that, the better.

When Asherah was later added to Dx2 - which for now is her final appearance in the series - she received a new compendium entry, which describes her as “a goddess from ancient Semitic religion, married to the Lord of the Mountains Amurru. She is thought of as the Mother of all Gods. As the goddess of love and fertility she was worshiped in ancient Babylonia. She is also known as Astarte in other religions.” Most of the information from the previous version returns, but we have a surprising case of doubling down on the reference to Mesopotamia - with a surprisingly accurate reference to Amurru thrown in. Once again, no trace of Yahweh, biblical cultic objects, or anything of that sort, though. Walker’s influence also cannot be detected. Later on, the Ugaritic material got an additional shoutout in Dx2 - with the advent of a feature letting the player turn spare demons into equipment, the option to turn Asherah into a sword with the ability “Lady of the Sea” was added. It should be noted that Dx2 later did throw the Bible into the mix, though - a craftable shield from the same update is named Asherah Pole, an obvious reference to the cultic objects discussed in the first section of the article. Still, I believe I’ve conclusively demonstrated nothing indicates that was the intent when the design was created for Strange Journey.

To sum up, ignoring the single outlier from Dx2, “Asherah” appears to be a mashup of the Ugaritic Athirat and Mesopotamian Ashratum - with the name clearly pointing at the former. That, at the very least, should be the romanization of it. I do think this adds a second layer of mistaken identity - Athirat and Ashratum have cognate names, but their character is dissimilar, and they were worshiped in different areas - but once again, the series has seen much worse.

My only problem with treating “Asherah” as Athirat is her design. It’s not that I necessarily dislike it (quite the opposite). It’s striking for sure, and its position as a fan favorite is well earned. I won’t delve into speculation whether the popularity boils down to Asherah being a large scantily clad woman covered in geometric patterns who’s easier to draw than fellow scantily clad large woman covered in geometric patterns Maya, and more prominent than fellow scantily clad and covered in geometric patterns (but not necessarily large) Cybele (who’s not in the base SJ which is beyond bizarre to me given that the game is a joyful tribute to Frazerian phantasmagorias by the way of Barbara Walker, but I digress). To be entirely fair, there isn’t really anything I could compare it to. No unambiguously identified iconographic representations of Athirat or Ashratum - let alone of the hypothetical “Asherah” - exist (A Reassessment…, p. 264). The so-called “pillar figures” are frequently labeled as “Asherah” (even in her wikipedia article), but for no particularly strong reason (A Reassessment…, p. 267).

Baal Cycle beach episode (personal screencap from 2021 or so; I do not recommend actually playing the gacha)

A question we should ask ourselves is whether it’s possible to imagine her playing her role from the Baal Cycle, given that it’s the most extensive source dealing with either Athirat or Ashratum. Despite never really adapting it, Megaten somehow managed to give us nearly the complete cast - and I would argue Baal, Anat, Yam, Mot and Attar all look like they could pull off their roles from this cycle of myths. How about “Asherah”? In theory she could, I suppose, though I personally would prefer Athirat to look visibly older, and somewhat less naked (I quite like this one). As the Mesopotamian Ashratum, the design would work perfectly fine, though. I will refrain from trying to evaluate whether the Old Babylonian official who called her the “mistress of voluptuousness and joy” would be fond of the contents of her pixiv tag, but I think her appearance represents this description pretty well.

The alien Dada from Ultraman, an Elamite boar vessel (via MET) and two pieces of Halaf ware (wikimedia commons)

As a side note, while Asherah’s coloration and patterns ultimately simply reflect Kaneko’s enthusiasm for an abstract art themed alien from Ultraman (I suspect the size does too), they unintentionally(?) make the “heroine” of this article resemble painted pottery - which works well enough, I think.

Post scriptum: Asura in Strange Journey

Asura, as portrayed in Strange Journey (MT wiki, via VeskScans) An article dealing with Asherah in Strange Journey - even one focused on different aspects of her role in the game - cannot leave out perhaps the most puzzling choice made during its development. I am referring, of course, to having Asura turn into her. Apparently a few years ago an assumption that Barbara G. Walker might be to blame was making rounds, though this is, surprisingly, entirely baseless (as documented here). My suspicion is that this has nothing to do with Asherah, and instead is a leftover of an earlier version of the game.

As revealed in the already discussed Megaten 25th anniversary book, Asura was initially supposed to turn into Ashur, the tutelary god of the city of Assur, and by extension Assyria as a whole (Megaten Maniacs, p. 133).

While there’s no deeper connection between the two other than a superficial phonetic similarity, presenting them as closely related is not actually not an invention of Atlus either. The notion that the Hindu Asuras have something to do with Ashur, or at least with Assyria more broadly, enjoyed some renown in the early decades of the 20th century, though even then wasn’t universally accepted (Hannes Sköld, Were the Asuras Assyrians?, p. 265-266). Today it is kept afloat largely just by all sorts of fringe websites, including but not limited to puzzling Hinduism-adjacent blogs and Atlantis truthers (are there people searching for the location of Hobbes’ Leviathan too?). Presumably, someone at Atlus found it in a similarly dubious source.

Ashur obviously didn’t make it into the actual game, and Asherah took his spot for some hitherto unknown reason. As per the same source (ie. Megaten Maniacs, p. 133), multiple other demons were replaced at some point in the game’s development. Interestingly, Ashur and Asura are the only case of only one half of a pair being replaced. Morax and Moloch were added as a replacement for Minotaur and Asterius, while Mithras and Mitra - for Asmodeus and Aeshma. Both of the scrapped pairs are closely related thematically: Asmodeus is a Jewish take on Zoroastrian Aeshma in origin; Asterius in this context was presumably intended as Minotaur’s actual given name (as given for example by Pausanias), and not one of the numerous other bearers of the same name in Greek mythology.

It sounds a bit as if some of the changes were done in a hurry. Going beyond the pairs, Ouroboros was supposed to be replaced by but they apparently failed to find someone appropriate - a figure with ma in the name who could take an “administrative role” among the mothers - on time (I think Ninimma would work - she has ma in her name, disputed claims of a “maternal” or “creative” role, and she clearly would work well as an “administrator” - but I digress). Even Mastema almost got replaced at the last minute. The developers apparently worried about his appeal to the potential audience, and considered replacing him with another angel, though no more precise information is provided. Given that he’s easily one of the most popular demons today this sounds pretty silly in retrospect.

Could it be that Asherah’s introduction was a last minute change like that? Perhaps Asura remained simply because there was no time left to design a more fitting demon to go with her (not that he was a particularly good match for Ashur in the first place)? These questions must remain unanswered, unless by some miracle more information about SJ development will emerge in the future, sadly. I feel obliged to point out that the Ashur case might've been a rare example of a situation in which Atlus could’ve instead just resorted to one of the series staples to make it more coherent. I’m talking, of course, about the persistent conflation of Asura and Ahura Mazda (as recently discussed by Eirikr here; note that even Asura’s SJ compendium entry brings it up).

The Assyrian god inside a ring (wikimedia commons)

The Achaemenid figure inside a ring (wikimedia commons) A connection between Ahura Mazda and Ashur, while not directly attested, is a fairly common subject of speculation in scholarship up to this day. To be specific, a symbol common in Achaemenid art, a winged figure inside a ring, is argued to be a representation of Ahura Mazda patterned on earlier Assyrian depictions of a god usually interpreted as Ashur (Michael Shenkar, Intangible Spirits and Graven Images: The Iconography of Deities in the Pre-Islamic Iranian World, p. 47-50; note that identification with Shamash is also relatively common, though).

A possible eastern depiction of Indra-like Ahura Mazda (left) with Nanaya (center) and Weshparkar (right) from Dandan Oilik (wikimedia commons) While Zoroastrianism is, at least nominally, aniconic, historically especially in the peripheries of the areas inhabited by its adherents (like the Caucasus or the western frontiers of China) the borrowing of iconography from neighboring cultures was frequent. The possible Ashur-Ahura Mazda depictions have less ambiguous parallels involving the iconography of Zeus (in Commagene, in Bactria, and on Kushan coins; Intangible Spirits…, p. 61-62) and even Indra (in Sogdia, sometimes complete with elephant mount; Intangible Spirits…, p. 63) being adopted to represent Ahura Mazda. I guess Ronde gets the last laugh here: the bizarrely Zeus-like Ahura Mazda accidentally turned out to be pretty accurate.

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

Incomplete vs. overshoot

I'm on tour with my new novel The Bezzle! Catch me TONIGHT in Seattle (Feb 26) with Neal Stephenson, then Portland, Phoenix and more!

You know the "horseshoe theory," right? "The far-left and the far-right, rather than being at opposite and opposing ends of a linear continuum of the political spectrum, closely resemble each other, analogous to the way that the opposite ends of a horseshoe are close together":

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horseshoe_theory

It's a theory that only makes sense if you don't know much about the right and the left and what each side wants out of politics.

Take women's suffrage. The early suffragists ("suffragettes" in the UK) were mostly interested in votes for affluent, white women – not women as a body. Today's left criticizes the suffrage movement on the basis that they didn't go far enough:

https://www.npr.org/2011/03/25/134849480/the-root-how-racism-tainted-womens-suffrage

Contrast that with Christian Dominionists – the cranks who think that embryos are people (though presumably not for the purpose of calculating a state's electoral college vote? Though it would be cool if presidential elections turned on which side of a state line a fertility clinic's chest-freezer rested on):

https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/otm/segments/how-alabama-ivf-ruling-was-influenced-christian-nationalism-on-the-media?tab=summary

These people are part of a far-right coalition that wants to abolish votes for women. As billionaire far-right bagman Peter Thiel wrote that he thought it was a mistake to let women vote at all:

https://www.cato-unbound.org/2009/04/13/peter-thiel/education-libertarian/

Superficially, there's some horseshoe theory action going on here. The left thinks the suffragists were wrong. The right thinks they were wrong, too. Therefore, the left and the right agree!

Well, they agree that the suffragists were wrong, but for opposite reasons – and far, far more importantly, they totally disagree about what they want. The right wants a world where no women can vote. The left wants a world where all women can vote. The idea that the right and the left agree on women's suffrage is, as the physicists say, "not even wrong."

It's the kind of wrong that can only be captured by citing scripture, specifically, A Fish Called Wanda, 6E, 79: "The central message of Buddhism is not 'Every man for himself.' And the London Underground is not a political movement. Those are all mistakes, Otto. I looked them up."

Or take the New Deal. While the New Deal set its sites on liberating workers from precarity, abuse and corruption, the Dealers – like the suffragists – had huge gaps in their program, omitting people of color, indigenous people, women, queer people, etc. There are lots of leftists who criticize the New Deal on this basis: it didn't go far enough:

https://livingnewdeal.org/new-deal-and-race/

But for the past 40 years, America has seen a sustained, vicious assault on New Deal programs, from Social Security to Medicare to food stamps to labor rights to national parks, funded by billionaires who want to bring back the Gilded Age and turn us all into forelock-tugging plebs:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/06/the-end-of-the-road-to-serfdom/

If you only view politics as a game of elementary school cliques, you might say that the left and the right are meeting again. The left says Roosevelt got it wrong with the New Deal (because he left out so many people). The right says FDR was wrong for doing the New Deal in the first place. Therefore, the left and the right agree, right?

Obviously wrong. Obviously. Again, the important thing is why the left and the right think the New Deal deserves criticism. The important thing is what the left and the right want. The left wants universal liberation. The right wants us all in economic chains. They do not agree.

It's not always just politics, either. Take the old, good internet. That was an internet defined by technological self-determination, a wild and wooly internet where there were few gatekeepers, where disfavored groups could find each other and make common cause, where users who were threatened by the greed of the shareholders behind big services could install blockers, mods, alternative clients and other "adversarial interoperability" tools that seized the means of computation.

Today's enshitternet – "five giant websites, filled with screenshots of the other four" (h/t Tom Eastman) – is orders of magnitude more populous than that old, good internet. The enshitternet has billions of users, and they are legally – and technologically – prevented from taking any self-help measures when the owners of services change them to shift value from users to themselves:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/02/19/twiddler/

The anti-enshittification movement rightly criticizes the old, good internet because it wasn't inclusive enough. It was a system almost exclusively hospitable to affluent, privileged people – the people who least needed the liberatory power of technology.

Likewise pro-enshittification monopolists – billionaires and their useful idiots – deplore the old, good internet because it gave its users too much power. For them, ad-blocking, alternative clients, mods, reverse-engineering and so on were all bugs, not features. For them, the enshitternet is great because businesses can literally criminalize taking action to protect yourself from their predatory impulses:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/10/20/benevolent-dictators/#felony-contempt-of-business-model

Superficially, it seems like the pro- and anti-enshittification forces agree – they both agree that the old, good internet was a mistake. But the difference that matters here is that the pro-enshittification side wants everyone mired in the enshitternet forever, living with what Jay Freeman calls "Felony contempt of business-model." By contrast, the disenshittification side wants a new, good internet that gives every user – not just a handful of techies – the power to decide how the digital systems they work use, and to be able to alter or reconfigure them to suit their own needs.

The horsehoe theory only makes sense if you don't take into account the beliefs and goals of each side. Politics aren't just a matter of who you agree with on a given issue – the real issue is what you're trying to accomplish.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2024/02/26/horsehoe-crab/#substantive-disagreement

#pluralistic#politics#suffrage#womens rights#new deal#civil rights#race#enshitternet#new good internet#old good internet

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

Several years ago, someone posted a request for recommendations of Jewish historical fiction not set during the Holocaust. This eventually found its way to my dashboard, and I reblogged it with a couple of hasty suggestions. I’ve embarked on a program of serious reading and thinking since then, and now I’ve got a whole list. Here they are, in roughly the order they take place. Please note that not all of these are unconditional recs (I’m picky); that it’s many years since I last read some of these books; and that some of them are probably out of print. (eBay is a robust used book market, my friends!)

Like several of the books on this list, As a Driven Leaf (1939), by Milton Steinberg, imagines the life of an historical figure about whom very little is known: in this case, Elisha ben Abuya (fl. ca. 100 C.E.), who is quoted exactly once in the Mishnah; the Gemara later relates that he became a heretic. The novel speculates as to what led to this and what happened to him afterward, against the backdrop of, among other events, the Bar Kochba revolt against Rome (132-136 C.E). (This isn’t unique subject matter: there are at least three other novels and one stage play about Elisha.)

Steinberg (1903-1950) was a Conservative rabbi and a highly prolific author considering his short lifespan, mostly of non-fiction; As a Driven Leaf was his only completed novel. As you might guess from the title, it’s a somber tale. It’s also extremely formal in its language and deliberate in its pace, and I remember struggling with it when I read it about 25 years ago. If that was true then, I wonder whether it will appeal at all to readers now, but I’m including it here for the sake of completeness. It’s probably unfilmable, but might work as an opera.

There’s a saying in Yiddish: Lebn vi Got in Frankraykh, “[One can] live like God in France.” The first French Jews didn’t speak Yiddish: they arrived in Roman Gaul during the first decade of the first century C.E., and for much of the next 1100 years enjoyed an unusually stable and secure existence in what became France. Although they were often taxed at a higher rate than their gentile neighbors and seem to have been quite limited in what professions they could enter, they could, and some did, own large estates (as vassals, to be sure) and major businesses and enjoy civil and even cordial relations with non-Jews. Learning flourished.

Things started to unravel during the second half of the 11th century C.E., as the Church became less preoccupied with the heretical Christian sects (Albigensians, etc.) and lingering paganism that characterized early Medieval France. That didn’t prevent the emergence of Rabbi Salomon ben Isaac, or Shlomo Yitzchaki (1040-1105 C.E.), commonly known by the acronym Rashi, a Scriptural and Talmudic commentator (and vintner) who lived, taught, and wrote in Troyes, in the Seine Valley, and who is arguably the most influential scholar ever to have worked in those fields. His writings were among the first to be put into print after the development of Hebrew movable type during the last third of the 15th century C.E., and for centuries they have been an integral part of every single page of the Talmud. What sets him apart from his predecessors is that he wrote not so much, or not only, for other scholars, but for all readers, using simple language and ideas. That’s the background of Maggie Anton’s Rashi’s Daughters trilogy — Book I: Joheved (2005), Book II: Miriam (2007), and Book III: Rachel (2009). (They should be read in that order.)

It is an historical fact that Rashi had three daughters and no sons. By most accounts, it’s also an historical fact that he gave his daughters the education he would have given his sons if he’d had any. Unconventional? Yes, and the girls definitely wouldn’t have had the opportunity to go to school the way boys did; however, Anton’s supposition that this would have had to be done in secret strikes me as highly questionable. I have a few other objections as well, mostly to do with language. Some of Anton’s word choices seem too contemporary (“crazy” rather than insane or mad; the adjective “amazing”). The frequent telescoping of French into English feels show-offy and quickly grows tiresome (especially since she uses modern French), although admittedly I didn’t have that reaction to her doing the same thing with Hebrew. And I occasionally felt talked down to: I don’t need to be told that Rosh Hashanah is the Jewish new year — but other readers might, and the author does seem to be aiming for a wide audience.

But never mind any of that! Anton, who had a long career in clinical chemistry before she turned to Talmud study and fiction writing, is a born storyteller! These are real page-turners filled with highly nuanced characters and I recommend them highly.

It would be a bit too easy to describe these novels as scholarly bodice-rippers. A fair amount of bodice- (or bliaut-and-chemise-) ripping does happen, some of it pretty explicit (and all of it within marriage), but the characters are far better developed than one would expect to find in a true bodice-ripper. What’s really impressive, though, is the breadth and depth of Anton’s research. Each book includes a timeline of historical events, a foreword setting the scene, an afterword sorting out fact, fiction, and speculation, and a (patchy) glossary. Books II and III include maps (and in Book III we get something we needed all along: a family tree!). There are no bibliographies in the books themselves, but you can find a selective one on the web, and at the end of Book I Anton invites readers to contact her and request a complete list of her sources.

Rashi's Daughters treats us to abundant information about many aspects not only of Jewish life, but also of life in general at the beginning of the High Middle Ages: trade (dyestuffs, spices, wool, second-hand jewellery), travel, manufacturing (cloth, ink, parchment, and other commodities, nutrition (though surprisingly little about gastronomy), personal hygiene, courtly love (which is dismissed as gentile foolishness), agriculture, viticulture and, of course, wine-making. Perhaps stemming from Anton’s background in healthcare, we also learn about a variety of medical problems: along with smallpox, meningitis, and other scourges now brought under control by vaccines, cerebral palsy, dementia, diabetes, hemophilia, leukemia, norovirus, and stroke all appear, not all named but all recognizable, along with a range of gynecological topics. (I should add that we’re definitely not talking about modern medicine or modern anything else here — no indeed! There’s a point near the end of every Jewish worship service when we pray for the time “when superstition shall no longer enslave the mind.” That's a fairly recent addition to the liturgy, but I found myself thinking of those words constantly as I read Rashi’s Daughters.) You’ll also learn a good deal about circumcision from these books. The only thing Anton mentions regularly without seeming authoritative is — wouldn’t you know it! — music, her descriptions of which are frustratingly vague. And of course there’s abundant discussion of, and many quotations from, the Talmud here.*

*If you’d like a non-fiction introduction to this subject, I recommend chapters 2 and 3 of Back to the Sources: Reading the Classic Jewish Texts, edited by Barry W. Holtz, or, for something more in-depth, The Essential Talmud, by Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz.

I really enjoyed Rashi’s Daughters and could continue of the subject for some time, but I’ve already done so at greater length than I had planned, so let’s see if I can finish up:

These books are clearly addressed to women readers, but if you’re looking for unnuanced positive depictions of women you’ll be disappointed. Responsibility for the (supposed) need for secrecy in carrying out the sisters’ education is laid squarely at the feet of their mother, who is portrayed as fixated on her family’s respectability and chronically angry to boot. This may have some basis in fact: surviving memoirs by Rashi’s sons-in-law and grandsons apparently contain hints that his marriage was unhappy. And while Miriam pushes the gender-role envelope very far indeed (she becomes a mohel), she also advises Joheved, who’s had a serious quarrel with her husband, to “accept how the Holy One created you, count your many blessings, and give in gracefully” — in other words, to submit to her husband’s authority. It’s 1086, and there isn’t much presentism in these books.

On a not unrelated note: the unravelling that I mentioned above gets serious in Book III, which contains some extremely violent scenes, and Book I includes an account (delivered second-hand) of harsh treatment of a group of women prisoners. One survivor of that experience is part of a family of Romanian converts to Judaism with whom Rashi’s family gets involved, who’ve been brought to France as slaves. And going back to language for a moment, non-Jewish readers, particularly those who identify as Christians of any description, should know that despite the aforementioned civil and even cordial relations, the words that Anton puts in the mouths of her Jewish characters when they discuss their Christian neighbors in private are — how shall I put this? — not always polite. And I strongly suspect that that’s historically accurate as well. (It might make edifying reading for some of you, actually.)

The three volumes of Rashi’s Daughters have a combined page count of 1,259, all packed with vital details. The only way to film them would be as a 26-hour mini-series, all in one swell foop, in the manner of the 1967 adaptation of The Forsyte Saga that led to the creation of Masterpiece Theatre. I’d absolutely watch that, but they just don’t do that sort of thing anymore, more’s the pity, and in any case I can already hear the verbal hand-wringing that would accompany each casting announcement. I can also imagine a great deal of lovely fan art emerging from these books.

I wrote about The Convert (De bekeerlinge, 2016; English translation, 2020), by Stefan Hertmans, which takes place in France and Egypt at the same time as Rashi’s Daughters, here. As you’ll see after you plough through all of the personal history and ruminating, I have mixed feelings about it.

One of the advance reviews of The Coffee Trader (2003), by David Liss, refers to it as an “historical noir”; that’s an excellent description. Set in Amsterdam in 1659, it’s the story of Miguel Lienzo. Once a highly successful commodities trader, he’s now suffering the consequences of having followed a series of bad hunches: he’s thousands of guilders in debt and has had to move in with his hostile younger brother, Daniel. He decides to take a huge risk on the title beans, which are just being introduced to the Western Hemisphere. It becomes clear that someone will stop at very little to see him fail, and that some of Miguel’s associates are secretly working for whomever that is. The book isn’t only Miguel’s story, however: we also get the point of view of Daniel’s unhappy wife, Hannah, as well as chapters from The True and Revealing Memoirs of Alfonzo Alferonda, in which Miguel’s frenemy and sometime business partner offers his side of the story. It’s all highly entertaining.

This very well-researched novel (there’s a 2 1/2-page bibliography at the end) is full of eye-opening information about the realities of Jewish life in the Dutch Golden Age. Among other things that I hadn’t known is that illiteracy was commonplace among Sephardic women. This was totally unheard of among us Ashkenazim, a fact that’s mentioned in the book. There are a couple of Sephardic names in my family tree, and after reading The Coffee Trader I’m no longer quite so tickled about that.

The Coffee Trader is actually a prequel to (and isn’t quite as good as) Liss’s three novels about Miguel’s nephew Benjamin, who uses the surname Weaver. These take place in London, where the Lienzos have moved, in the early 1720s. (This leaves us with some serious storytelling problems. First of all, there’s a time-warp: Miguel seems to be in middle-to-late 20s in 1659, meaning that by 1720 he would be much older than all but a few people lived to be at that time. He has also moved from borderline rascal to pillar of rectitude, and he’s married to someone other than the woman to whom he’s married at the end of The Coffee Trader. We never learn what led to any of this. For a continuity fussbudget like yours truly, this this adds up to bad news.) Benjamin is a former prize-fighter — he’s very loosely based on a somewhat later historical figure, Daniel Mendoza (1764-1836) — who now earns his keep as a “thief-taker”: that is, he’s a private detective! These are whodunits.

The first two books take place during very specific historical events: the South Sea Bubble of 1720 (A Conspiracy of Paper, 2000) and the 1722 general election (A Spectacle of Corruption, 2004). The third, The Devil’s Company, 2009), takes place later in 1722 and is about the East India Company — in particular, a semi-clandestine effort by the company to overturn a piece of 1721 legislation that would have made illegal the wearing of Indian cottons, effective Christmas Day 1722. (This was an effort to protect the interests of the British wool and silk industries, as well as to boost the cottons that were beginning to be imported from Britain’s North American colonies.) Here, too, we learn a great deal about the conditions of Jewish life at that time and in that place: not good — but, as a character in The Devil’s Company points out, considerably better than in most Catholic nations on the Continent.

The Weaver books are eminently filmable (The Coffee Trader not so much, I suspect — too many flashbacks), but there would be casting problems up the wazoo, particularly given the need to draw heavily from the generation of actors now in their twenties and thirties, whose main concern often seems to be “representing” — rather than, y’know, acting. The thing is, Liss is a well-trained historian (he set aside his Columbia University Ph.D. dissertation in favor of writing historical fiction), and there isn’t one single iota of presentism in his writing. Weaver is a man of his time and place, and his attitudes towards what and whom he encounters reflect this. (Theoretically this could offend even me, since he takes a dim view of the Eastern-European Jews who have begun trickling into England.)

I recall Promised Land (1998), by Ruhama Veltfort, as a terrific yarn, but I have some questions about its historicity. It gives us the tale of an extended family, newly arrived in America from partitioned Poland, attempting to make the overland crossing to California in a covered wagon in 1846-47. Friends, I’ve read a great deal over the years about the Westward Expansion, and I’ve never found a single thing about Jewish overland migrants — and believe me, I was looking for something, even a crumb! (For complicated reasons, it was a very meaningful subject for me in my youth.) Jewish history in California doesn’t begin until 1849, and the first arrivals got there by sailing around Cape Horn. Still, it makes for a great story (and it might be an entertaining film)!

All Other Nights (2009), by Dara Horn, is a Civil War story (ours in the U.S., theoretically from 1861 to 1865, but actually it’s still being fought, every single day). A young Jewish man enlists in the Union Army in order to avoid an arranged marriage and is sent under cover into Confederate territory. His first assignment is the assassination of a New Orleans man who’s believed to be plotting the assassination of President Lincoln — and who happens to be the protagonist’s uncle by marriage. (Many Jewish families were divided during the Civil War.) Several well-known historical figures make brief appearances, and the hero’s romantic interest is based on a lesser-known real person. I enjoyed this book very much, but as with Rashi’s Daughters, non-Jewish readers may want to approach it with a bit of caution: y’all really don’t come off too well here.

When first printed, the book had a note in the back announcing that film and television rights were available, and it would indeed make a wonderful mini-series. It’s surprising that this hasn’t happened. (Or, on the other hand, maybe it isn’t.)

The Rise of David Levinsky (1917), by Abraham Cahan, is one of the great American novels that people no longer read. I can’t decide whether it’s historical fiction or not: it takes its protagonist/narrator right up to the time of publication, as he looks back on his impoverished (but scholarly) childhood and adolescence in Tsarist Russia, through his immigration to the United States at 20 in 1885 (putting him in the vanguard of the mass exodus of Jews from Eastern Europe), to his emergence as “one of the two or three leading men in the cloak-and-suit trade in the United States.” Along the way, he makes a lot of bad personal choices and pretty much loses his soul.

Cahan (1860-1951) was born into a rabbinical family in what is now Lithuania. He received quite a bit more in the way of secular education than was typical for someone in his circumstances, and became an ardent socialist. This became dangerous after March 1881, when Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by a member of a socialist organization; in 1882 Cahan was interrogated by the police, and later that year he emigrated to the United States — placing him in the pre-vanguard of the migration mentioned above, which got underway in earnest the following year. He became a journalist working in the Yiddish-language press, and is remembered today chiefly for his involvement with the iconic Yiddish newspaper Forverts (still very much a going concern). He also wrote fiction in English. His 1896 novella Yekl: A Tale of the New York Ghetto was the basis for the film Hester Street (which you should see if you haven’t). The Rise of David Levinsky has already been adapted as a musical (Off-Broadway, 1987); it would make a fine film.

Your Mouth is Lovely (2002), by Nancy Richler, isn’t exactly light reading: in 1912, in a letter to the daughter who was taken from her at birth, the protagonist looks back over her short life and hard times as she is dying of tuberculosis in a Siberian prison camp, where she’s been sent as punishment for her tiny role in the failed Russian revolution of 1905. (The title is from Song of Songs 4:3; it’s part of what is traditionally said to a child when he or she speaks for the first time.) It’s a grim tale of things going from bad to worse. It probably isn’t adaptable — possibly as an opera, but probably not even that.

Richler (1957-2018) was Canadian, but spent time in the United States while growing up, and it must not have been a good experience: the protagonist’s family end up variously in Montreal and Buenos Aires — but nowhere in the United States!

Hungry Hearts (1983), by Francine Prose, takes place in the 1920s in the world of the New York Yiddish theater. The actors playing the star-crossed lovers in Saul Ansky’s The Dybbuk fall in love for real. When their director gets wind of this, he demands that they keep it a secret at all costs: after all, if the audience knows about their relationship, what happens to their suspension of disbelief? This has consequences during an eventful Latin American tour (with a magical-realist element that I remember finding off-putting — your milage may vary).

I’m all but certain that this one is out of print. Prose still writes about Jewish subjects, but she’s become very sour. She says that she doesn’t recognize the person who wrote Hungry Hearts and her other early work, and has resisted all efforts to return it to print. It might work as a film, if she were to permit such a thing.

Finally, for younger readers I recommend the All-of-a-Kind Family series, by Sidney Taylor: All-of-a-Kind Family (1951), More All-of-a-Kind Family (1954), All-of-a-Kind Family Uptown (1958), All-of-a-Kind Family Downtown (1972), and Ella of All-of-a-Kind Family (1978), which take place on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and later in Brooklyn, between 1912 and the early 1920s and follow the progress of an Eastern-European immigrant couple and their American-born children.

This series accounts for roughly half the output of Sidney Taylor (pseudonym of Sarah Brenner Schneider, 1904-1978), after whom the annual Sidney Taylor Book Awards and Sidney Taylor Manuscript Award are named.

Text dividers by @steddiecameraroll-graphics.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading Lists: American Revolution

A non-exhaustive reading list of popular/academic histories that I have mostly read either in full or at least in part; some of them I have not read but am familiar with the author. I grouped them based on what I think their primary focus is but there is obviously some overlap.

General

Carp, Benjamin L. Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America. Yale University Press, 2010.

Fichter, James R. Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, 1773-1776. Cornell University Press, 2023.

Hinderaker, Eric. Boston's Massacre. Belknap Press, 2017.

Holton, Woody. Liberty is Sweet: The Hidden History of the American Revolution. Simon & Schuster, 2021.

Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. Vintage Books, 1998.

Nash, Gary. Urban Crucible: The Northern Seaports and the Origins of the American Revolution. Harvard University Press, 1986.

Taylor, Alan. American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804. WW Norton & Company, 2016.

Emotions and Relationships

Eustace, Nicole. Passion is the Gale: Emotion, Power, and the Coming of the American Revolution. University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Godbeer, Richard. The Overflowing of Friendship: Love Between Men and the Creation of the American Republic. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Knott, Sarah. Sensibility and the American Revolution. University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Pearsall, Sarah M.S. Atlantic Families: Lives and Letters in the Later Eighteenth Century. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Zabin, Serena. The Boston Massacre: A Family History. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020.

Women

Anishanslin, Zara. Portrait of a Woman in Silk: Hidden Histories of the British Atlantic World. Yale University Press, 2016.

Berkin, Carol. Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America's Independence. Knopf, 2005.

Kerber, Linda. Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America. University of North Carolina Press, 1980.