#aleksandr dovzhenko

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Арсенал (Aleksandr Petrovič Dovženko, 1929)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

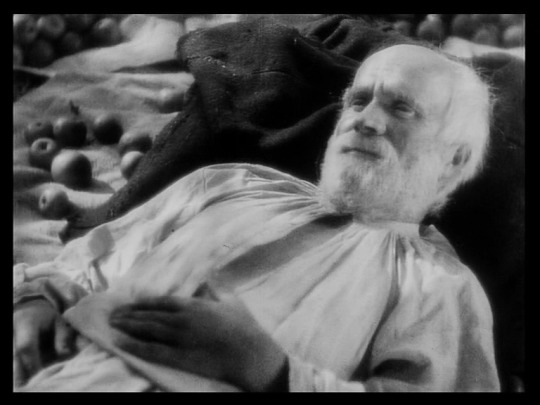

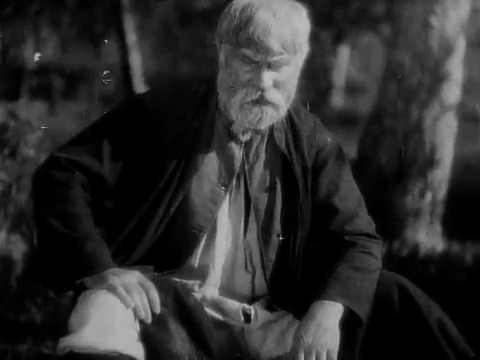

Earth (Aleksandr Dovzhenko, 1930)

Cast: Stepan Shkurat, Semen Svashenko, Yuliya Solintseva, Yelena Maksimova, Mykola Nademsky, Petro Masokha, Ivan Franko, Volodymyr Mikhajlov, Pavlo Petrik. Screenplay: Aleksandr Dovzhenko. Cinematography: Danill Demutsky. Art direction: Vasyl Vasylovych Krychevsky. Film editing: Alexsandr Dovzhenko.

At once lyrical, tragic, and enigmatic, Aleksandr Dovzhenko's Earth might be viewed today as an example of how Ukraine has always been a temptation and a thorn in the side of Russia -- or at least those in Russia who would try to rule it. As a film about the collectivization of agriculture in the young Soviet Union it bears comparison to Sergei Eisenstein's The Old and the New (1929), which attempted that subject with a much heavier hand: Its celebration of the tractor, in comparison with Dovzhenko's somewhat problematic introduction of a tractor whose radiator has to be pissed in before it will function, concludes with a tractor ballet. And Eisenstein's treatment of the reactionary clergy involves an all too obvious montage in which the followers of the church are juxtaposed with a herd of sheep; Dovzhenko is content with just showing his priest's frenzied proclamations of anathema on the collectivists. But Eisenstein's film, like Dovzhenko's, met with official disapproval: Collectivization was just too important to Stalin not to undergo intense ideological scrutiny. Artistically, Dovzhenko's Earth has to be judged the greater film, one in which the relationship of beauty and terror informs almost every frame.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Michurin, Aleksandr Dovzhenko, 1949

0 notes

Text

vimeo

The Magnificent Ambersons es la película más íntima y personal de Orson Welles, también su preferida junto a Falstaff – Chimes at Midnight.

Welles no tuvo control sobre el montaje final por no contar con la aprobación del público tras proyectarse en Pomona y la película pierde algo más de 43 minutos. Los 88 restantes resultan tan discontinuos, desconcertantes, enigmáticos y brillantes, que reconvierten la experiencia en un paseo por las ruinas de lo que había o habría sido (David O. Selznick no consiguió que delegasen una copia íntegra al Museo de Arte Moderno de Nueva York). Se nos ha negado, por tanto, su compleción. Esta mutilación deviene en una misteriosa narrativa que evoca The Searchers, The Wings of Eagles, El Sur o casi cualquier película de Mizoguchi (entre tantos otros ejemplos).

El año en que se estrena, Stefan Zweig se suicida con su esposa en Brasil, desesperados ante la posible propagación mundial del nacionalsocialismo. Casualmente, tanto Letter from an Unknown Woman (novela corta del autor llevada al cine por Max Ophüls) como la película de Welles atesoran algunas de las mejores secuencias que se hayan filmado jamás sobre personajes que transitan escaleras (como podréis comprobar en el vídeo que acompaña esta publicación). A colación de lo anterior, conviene recordar a Tourneur, que también rodaría ese año otra portentosa película en el mismo decorado por el que deambulan los Amberson.

Algunos planos picados de la película recuerdan aquello a lo que tan admirablemente aludía Clarín en La Regenta. De ese mundo contemplado desde las alturas en clave alegórica, nos vamos a otro distinto en los falsos contrapicados, al de Tierra, de Aleksandr Dovzhenko.

Shakespeare, Proust y Chéjov casi siempre están presentes en las películas de Welles, como también el ideario que subyace tras aquella célebre aserción elegíaca de Cocteau: filmer la mort au travail, cuya aplicación y extensión más representativa podría encontrarse en el personaje de Jedediah Leland en Ciudadano Kane.

Se han mencionado grandes autores con los que Welles establece diafonías y correlaciones, pero me resulta inevitable citar el hilo invisible que une esta película con buena parte del cine de Paul Thomas Anderson, ya que su adyacencia a nuestra contemporaneidad quizá no resulte tan evidente. El contrapunto podría localizarse en la primera aproximación a la novela de Tarkington en la que se basa The Magnificent Ambersons y que lleva por título Pampered Youth (adaptación en la que su director, David Smith, estuvo trabajando aproximadamente durante los años 1924 y 1925).

En la escena que figura a continuación, Orson Welles enclaustra dos corolarios fundamentales: la falta de autoridad en el seno de los Amberson y el sometimiento fantasmagórico y opresivo con el que George pretende dominar a su madre, alentado por su convencimiento de que Eugene —tal y como describe Shakespeare en Hamlet— se había precipitado con premura al tálamo incestuoso. En previsión de dicha catástrofe, decide acechar con vigía y desde una atalaya sombría mientras conspira para perpetuar la materialización de sus convicciones aristocráticas. Bernard Herrmann ilustra y enfatiza la insidia del personaje con su particular Ostinato.

Dado que el paso del tiempo y el tiempo perdido podrían considerarse dos de las obsesiones preponderantes y recurrentes en la filmografía de Welles, sirva de homenaje al esplendor y posterior decadencia de los Amberson esta joya poética de Manuel Alcántara:

"Yo no sé qué voy a hacer cuando se me vaya el tiempo y no pueda irme con él. Tengo los días contados, y él ha perdido la cuenta del futuro y del pasado. El tiempo siempre es presente y pasa mientras se queda, por eso nunca se entiende. Jamás es pronto o despu��s, por más que pasen los años no pasa el tiempo por él. Ni lo pierdas ni lo ganes, el tiempo sabe que tiene todo el tiempo por delante. No sé qué va a ser de mí el día que yo me vaya, y él no se quiera venir"

#the magnificent ambersons#el cuarto mandamiento#orson welles#tim holt#joseph cotten#dolores costello#agnes moorehead#anne baxter#richard bennett#ray collins#nancy gates#film#cine#Vimeo

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Research Blog Post #3

Sergei Parajanov

Sergei Parajanov (1924–1990) was a filmmaker, visual artist, and visionary whose films blur the line between cinema and visual art. Born in Tbilisi, Georgia, to Armenian parents, he studied at the VGIK film school in Moscow under Aleksandr Dovzhenko and initially worked within the Soviet system, but quickly broke away from Socialist Realism. Parajanov’s most significant works—Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964), The Color of Pomegranates (1969), The Legend of Suram Fortress (1984), and Ashik Kerib (1988)—are renowned for their rich, surreal, image-driven storytelling.

Though not a photographer, his approach to film was photographic in the most literal sense: each frame composed like a still-life, often symmetrical, symbol-laden, and packed with texture and color. The Color of Pomegranates in particular stands out as a visual poem, a film that resists linear narrative and instead unfolds in tableaux—each shot meticulously arranged like a museum diorama or a Byzantine icon. It tells the life story of Armenian poet Sayat-Nova, but not through plot or dialogue—instead, it moves through mood, memory, and symbolism.

Parajanov’s films were constantly censored or banned by Soviet authorities. He was imprisoned multiple times, blacklisted, and many of his projects were halted before they could be completed. Despite this, his reputation grew internationally, attracting admiration from directors like Fellini, Godard, and Tarkovsky. In the last decade of his life, he created collages, drawings, and dioramas, which were later exhibited alongside his films.

Watching The Color of Pomegranates felt like flipping through a sacred photo album, delving into Armenian culture, but one you can’t look away from. The film doesn’t try to explain anything. It just presents — a candle burning on a tomb, a boy surrounded by books, a red cloth unfurling across a white stone courtyard. No words, just images that feel like dreams or half-remembered stories passed down visually.

What moves me about Parajanov’s work is his refusal to compromise his vision. He didn’t necessarily care about plot or exposition — he trusted the image. That’s rare. In a world obsessed with speed and clarity, Parajanov gives you something dense, slow, and symbolic. And even though I work with still images, not film, the influence is real. His layering of meaning through color, texture, and gesture makes me think about how I construct an image — not just what’s shown, but what’s felt. His work challenges me to take risks, to be more poetic, and to trust the image to carry weight on its own.

Give it a test yourself. Watch The Color of Pomegranates and go to any random point. I assure you, it may surprise you.

youtube

0 notes

Photo

Earth // Земля (1930) dir. Aleksandr Dovzhenko

#earth#земля#aleksandr dovzhenko#ukraine#worldcinemaedit#silentfilmedit#filmedit#classicfilmedit#silent film#landscape#jp=2#*earth

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

J’accuse (Abel Gance, 1919) | Arsenal (Aleksandr Dovzhenko, 1929)

#j'accuse#abel gance#1919#arsenal#aleksandr dovzhenko#1929#silent film#silent movies#silent cinema#silent#french cinema#french movie#french film#soviet cinema#soviet film#soviet movie#wwi

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Earth (Zemlya, 1930) - Aleksandr Dovzhenko

The Southerner (1945) - Jean Renoir

8 notes

·

View notes

Quote

From Salvador Dalí [Cadaqués, March 1932] Dear Luis, I’ve just received your letter, which I consider to be very serious indeed. I see you have completely abandoned all the ideas (surrealist) that we shared until now, and all for the sake of party discipline. I am surprised that the simple fact of joining the Communist Party should eliminate all vestiges of intelligence, even in individuals such as Aragon and yourself who (although no proof of this existed previously) might now be mistaken for the most elementary and infantile obscurantists. I am going to address in haste (because it would take ten more letters) the points in your letter that I regard as the most fundamental and the most monstrous. The most striking of which is your absolute lack of dialectic. You talk of your unspeakable plan to go on with the magazine as if nothing had happened, and to make it strictly surreal and experimental with no political articles (!); when it is not the communist articles the communists object to, but the strictly surrealist ones (the Kharkov resolution); in fact, the communist articles were introduced by the communist-surrealist faction. This all seems nonsensical to me, especially the unimaginable sentence with which you conclude your explanation that I cite here verbatim: ‘This approach may not be brilliant, but time will prove us right.’ No, this will never prove us right because surrealist experimentation is, and always will be (if genuine), regarded as very subversive by today’s society (that is to say, by the bourgeoisie), and as infinitely more subversive by today’s communists, as they are paving the way for a bourgeois state of mind and ideology that is far inferior in evolutionary terms. As for the films, I beg you not to undermine the gravity of this issue with yet another phrase that, again, is absolutely inexplicable coming from you: ‘Do not forgive their artistic errors.’ Artistic errors!! It’s not about those errors (which do exist). Those films, shitty proletarian literature, etc., etc., are polemical works, with entirely propagandistic ends; they are the faithful expression of the spirit and ideology to which they aspire; these are polemics that are not only permitted (PERMITTED) by the government but made by that same government. Those films and that literature are abominations, made in the spirit of ideological shit, on grubby mysticism, on veiled sanctity, etc., etc.. That was what made Aragon cry when he saw Earth, Dovzhenko’s infamous film, not its artistry, but its ideological content. It is all unforgiveable; we are not talking, therefore, about artistic errors (I for one will never forgive the indecent optimism of that poem ‘Red Front’, I find it shameful, poetically speaking. Poppies are red flags! It sounds Andalusian! It could almost, almost be Catalan!!!) However, the most unbelievable phrase in your letter is this one: ‘This new spirit of communism will reach future generations when the imperialist threat has passed, the dictatorship of the proletariat will come to an end with the disappearance of the social classes’. This phrase is exactly the kind of reformist fatalism in the realm of politics that you all (and rightly) used to hate so much; it is the equivalent of saying: ‘There is no need to protest now nor prepare for the revolution because communism will arise inevitably out of the development of history and inherent contradictions of capitalism’(!). ‘This is what the future generations will get’!!! This is your anti-dialectical reasoning when faced with the most transcendental and most human spiritual questions. As this new state of mind and morality is the inevitable consequence of social and economic revolution, we do not need to concern ourselves with them any longer. WHAT SHIT! Those of us who have defended ideological and spiritual subversion honestly demand intervention, violent, incessant and urgent intervention in this sphere, as in the political sphere, through the most effectively revolutionary actions. Historical materialism based on the constant assimilation of scientific evolution raises serious questions today: there are endless indications that this new obscurantism suggests that significant aspects of modern knowledge have not been incorporated into Marxism, nor into proletarian culture, and even that a significant amount of that knowledge has been brutally rejected. They do analyse with some objectivity the case for psychoanalysis as today’s Marxists perceive it. But it is truly shameful. There are some completely erroneous ideas in Marx and Engels (on love) that may have been due to shortcomings in scientific knowledge at the time, but that are still held today. These ideas have been subjected to absolutely no modification to date, in spite of the overwhelming existence of Freud. Had Marx, who appreciated as if it were his own the saying that ‘nothing human is alien to me’, and who turned even the meagre insights of his time to good effect when constructing his theories; had Marx known Freud, do you not think that he would have modified his timid theories of love? Everything is being violently rejected by the Stalins of today who are organizing the most chaste, most REPRESSED society in history: playing checkers (?); physical exercise and only the kinds of love they consider to be natural and healthy (!!). They are conjuring up the most horrendous form of spiritual slavery. The rejection of everything that seems to be subversive in modern natural sciences is the same as the rejection of surrealism, instead all efforts will be channelled into the creation, little by little (alongside the great and magnificent economic revolution) of a bourgeois spirit, starting with the current shit of proletarian art and eventually raising ‘future generations of ever more perfect spirit’. Juan Ramón Jiménez, for example, will surely be modified, but it will be for a more gentle Juan Ramón Jiménez, one that is less aggressive and more bourgeois as in the future communist society he will not have been influenced by our aggressive age of class and economic struggle. In your case and in Aragon’s, your absolute lack of appreciation for historical responsibility is monstrous. We may forgive the millions of revolutionaries who have no knowledge of surrealism, but in your case, you KNOW what surrealism represents for this age (particularly now, in the age of Russia’s moral brutalization): THE ONLY POSSIBLE FUTURE FOR THE WORLD, FOR THE SPIRIT, AND FOR TRULY SUBVERSIVE MORALITY, I say your attitude is unforgiveable for we have a unique historical mission that depends on our own activities and conscience. I know that you are both sincere people and that may well make it worse. With your new communist stance, you are as distant from me as Federico was when he published his Gypsy Ballads. All of this reflects a frightening spiritual weakness that makes me think you never felt surrealism as I did. Surrealism will be strengthened by this future split because it was being held back by that unfortunate political dilettantism, from now on we shall denounce all shit, even if it is proletarian. In fact, Aragon has not existed as a surrealist for a while now. And you have contributed nothing to surrealism, theoretically, despite my very high hopes of you. Surrealism is the only moral consolation left: you cannot imagine how strongly I condemn your attitude. Down with the bourgeois and reactionary optimism of the five-year plan! LONG LIVE SURREALISM! This time, I violently demand a reply from you: there are no legitimate excuses; you cannot leave me with no news again for three months. It is very important for our friendship. I await your immediate reply with all the candour and violence you think necessary. Regards, Dalí PS If we could talk, you would see that I am able to expand on and justify everything that I’ve just said here, because I am surrounded by notes and extremely well informed on all these matters, they are as familiar to me as to any communist. I’ve done nothing but read Marx (or ‘about Marxism’?) for the last three months. I am preparing a long article on what Marx called bestial love and modern sexual love, full of documentary evidence and enormously objective. In it, I conduct an extensive analysis of perversion as an essential characteristic and condition of human love in that it (perversion) presupposes the intervention in love of intelligence and imagination. What we call human love is in fact bestial: but I demonstrate all of this with reference to quotations well known to everyone and with a precise methodology.

Jo Evans & Breixo Viejo, Luis Buñuel: A Life in Letters

#jo evans#breixo viejo#luis bunuel: a life in letters#salvador dali#luis bunuel#louis aragon#aleksandr dovzhenko#karl marx#friedrich engels#sigmund freud#juan ramon jimenez

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arsenal (1929)

Silent film

Dir.Aleksandr Dovzhenko

Based on an actual incident from 1918, the film’s story concerns a group of Ukrainian Bolsheviks who revolted against the Central Rada, the first government of independent Ukraine. The Bolsheviks put up a defense of their cause inside the Arsenal munitions plant in the capital city of Kyiv. Outnumbered by the Ukrainian government troops the Bolshevik rebels are overrun and defeated in a climactic battle, but their revolutionary spirit prevails. The film is notable for Dovzhenko’s refusal to reject national identity as a source of courage. Although his films, like all Soviet films of the period, were made officially "in the service of the state," they’re deeply subversive.

#Arsenal#film#1929#Soviet film#Ukraine#based on a true story#1918 incident#Ukrainians#drama#war#Semyon Svashenko#Aleksandr Dovzhenko#just watched#silent film#cinema#world cinema#early cinema

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zvenigora, Aleksandr Dovzhenko (1928)

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Love’s Berries (1926), dir. Aleksandr Dovzhenko

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Shchors, Aleksandr Dovzhenko, 1939

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zemlya / Earth (Aleksandr Dovzhenko, 1930)

23 notes

·

View notes