#and mass distributed commercially

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Men's literary autofiction is about the boundaries of consciousness/life/death, how hard it is to be a genius artperson, professional identity, universal questions of choice and morality, etc. Women's literary autofiction is about trauma, parents, children, heterosexuality and mental illness 🤩🤩

#when capitalist hell art marketing gives you gender dysphoria 😭😂😂😂😂#to be clear this post is NOT about what art people of different genders are CAPABLE of making. its about what gets published#and mass distributed commercially#post cowritten by me visiting a non vintage bookstore and actually looking at the books there#sometimes i hate being a woman because i dont like 'women's things'. i like women and most of the important people in my life are#extremely smart women but i hate socially ascribed womanhood. unfortunately i dont like any other gender categories better ksksksks#i'm a woman but if being a woman in society was actually nice and normal and not a torture prison skksksks#also yeah trauma etc etc etc is a valid topic for a book. however i dont like those and i hate that women arent allowed to write what i like

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there! I'm a human artist who is (very loosely) following the Disney/Universal vs. Midjourney case, and you seem like you're pretty knowledgeable about it and it's potential consequences, so if you have time/energy to answer a question I have about it I'd greatly appreciate it! If not, no worries, feel free to ignore! I haven't had the chance to read through the whole complaint document itself, but at the very top, point 2 mentions:

"...distributing images (and soon videos) that blatantly incorporate and copy Disney’s and Universal’s famous characters—without investing a penny in their creation—Midjourney is the quintessential copyright free-rider and a bottomless pit of plagiarism. Piracy is piracy, and whether an infringing image or video is made with AI or another technology does not make it any less infringing."

Do you know if human-made fanart would also be included in this? Or is this something that would only be aimed at big companies? the "incorporate Disney's characters" part is giving me some pause, but like I said I haven't had the chance to read the full document and I'm not confident in my knowledge of copyright law. 😅 Thank you in advance if you're able to answer this! (Brought to you by a concerned fanartist with near-equal disdain for both Disney and AI. also sorry for the essay-length question 😅)

No problem at all, I'm happy to help ease your worries!

To put it simply, nothing is going to change for us. This is only going to affect unethical LLMs like MidJourney, OpenAI, etc. trained on copyrighted material without consent.

This is because Disney (and Universal) are arguing that LLMs are already infringing current copyright law. LLMs make money by directly using their copyrighted images fed into machine that then regurgitates their IP, and is sold for a premium, en mass.

So there's that, but even more importantly: it's already illegal to make money off of fanart.

Which, corporations don't really care about unless you're making a LOT of money or getting a LOT of attention. This is because it's quite expensive to take someone to court, and you have to prove your business was negatively affected by said fanart (nearly impossible in most cases). You've got to be making quite a bit more money than the court costs, and provide documented proof of damages (to your wallet or name) for corporations to go after you.

Which, your individual/indie fanartists don't qualify... but MJ most certainly does.

So, not to say something bad can't possibly crop up from this court case, but there are quite a few things protecting us: there's no angle in the court case that targets fair use (this indirectly protects non-commercial fanart), the court case touches on human interpretation being essential for transformative art (which LLMs don't have since they're automatic), LLMs are already infringing existing copyright law (making money using Disney's images), Disney has quantifiable proof of damages to their company by said LLMs (nigh impossible for individuals to do), corporations have a vested interest in keeping fair use around as free advertisement (fanart is akin to spoken word about your product), and fair use is intensely tied to freedom of speech.

So don't worry! There are reasonable concerned voices considering how evil Disney and Universal both are--but most of the vehement arguments being made against this court case are from scared techbros who want unfettered access to your money and labor. Current copyright and IP law is far from perfect, but anyone calling for total abolition thereof wants protection taken from individuals like us.

#zilly squeaks#copyright#ai#llm#Disney#I'm getting some techbros in my mentions and i ain't babysitting y'all#so if u come at me with any of your psyops I'm just blocking you#y'all are dumb as hell and obvious as fuck

254 notes

·

View notes

Photo

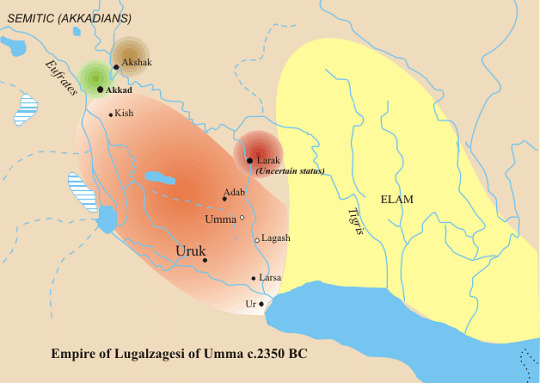

Uruk

Uruk was one of the most important cities (at one time, the most important) in ancient Mesopotamia. According to the Sumerian King List, it was founded by King Enmerkar c. 4500 BCE. Uruk is best known as the birthplace of writing c. 3200 BCE as well as for its architecture and other cultural innovations.

Located in the southern region of Sumer (modern day Warka, Iraq), Uruk was known in the Aramaic language as Erech which, it is believed, gave rise to the modern name for the country of Iraq, though another likely derivation is Al-Iraq, the Arabic name for the region of Babylonia. The city of Uruk is most famous for its great king Gilgamesh and the epic tale of his quest for immortality but also for a number of firsts in the development of civilization which occurred there.

It is considered the first true city in the world, the origin of writing, the first example of architectural work in stone and the building of great stone structures, the origin of the ziggurat, and the first city to develop the cylinder seal which the ancient Mesopotamians used to designate personal property or as a signature on documents. Considering the importance the cylinder seal had for the people of the time, and that it stood for one's personal identity and reputation, Uruk could also be credited as the city which first recognized the importance of the individual in the collective community.

The city was continuously inhabited from its founding until c. 300 CE when, owing to both natural and man-made influences, people began to desert the area. By this time, it had depleted natural resources in the surrounding area and was no longer a major political or commercial power. It lay abandoned and buried until excavated in 1853 by William Loftus for the British Museum.

The Uruk Period

The Ubaid Period (c. 5000-4100 BCE) when the so-called Ubaid people first inhabited the region of Sumer is followed by the Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE) during which time cities began to develop across Mesopotamia and Uruk became the most influential. The Uruk Period is divided into 8 phases from the oldest, through its prominence, and into its decline based upon the levels of the ruins excavated and the history which the artifacts found there reveal. The city was most influential between 4100-c.3000 BCE when Uruk was the largest urban center and the hub of trade and administration.

In precisely what manner Uruk ruled the region, why and how it became the first city in the world, and in what manner it exercised its authority is not fully known. Scholar Gwendolyn Leick writes:

The Uruk phenomenon is still much debated, as to what extent Uruk exercised political control over the large area covered by the Uruk artifacts, whether this relied on the use of force, and which institutions were in charge. Too little of the site has been excavated to provide any firm answers to these questions. However, it is clear that, at this time, the urbanization process was set in motion, concentrated at Uruk itself. (183-184)

Since the city of Ur had a more advantageous placement for trade, further south toward the Persian Gulf, it would seem to make sense that city, rather than Uruk, would have wielded more influence but this is not the case.

Artifacts from Uruk appear at virtually every excavated site throughout Mesopotamia and even in Egypt. The historian Julian Reade notes:

Perhaps the most striking example of the wide spread of some features of the Uruk culture consists in the distribution of what must be one of the crudest forms ever made, the so-called beveled-rim bowl. This kind of bowl, mould-made and mass-produced, is found in large numbers throughout Mesopotamia and beyond. (30)

This bowl was the means by which workers seem to have been paid: by a certain amount of grain ladled into a standard-sized bowl. The remains of these bowls, throughout all of Mesopotamia, suggest that they “were frequently discarded immediately after use, like the aluminum foil containing a modern take-away meal” (Reade, 30). So popular was the beveled-rim bowl that manufacturing centres sprang up throughout Mesopotamia extending as far away from Uruk as the city of Mari in the far north. Because of this, it is unclear if the bowl originated at Uruk or elsewhere (though Uruk is generally held as the bowl's origin). If at Uruk, then the beveled-rim bowl must be counted among the many of the city's accomplishments as it is the first known example of a mass-produced product.

Continue reading...

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

incredible that everyone is crying crocodile tears over the death of Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Asia/whatever. do you... know anything about these stations, by chance?

1982 Duke paper citing that VOA/RFE/RFA are CIA propaganda.

Brief History of VOA’s Domestic Propaganda

"During the Cold War, America’s three largest overseas propaganda venues were Voice of America (VOA), Radio Free Europe (RFE) and Radio Liberty (RL). These mass media outlets are still active today, avidly pushing US geopolitical and corporate interests, including wars, invasions and regime change operations. During the Cold War, these networks pushed US-government propaganda under the guise of advocating democracy, human rights and truth. They still do. But only the VOA was truthful enough to admit it was state financed. Beginning in 1942 under the Office of War Information, the VOA now has a US$200-million budget and broadcasts its propaganda in 45 languages to 270 million people per week.1 The RFE and RL began in 1949 as covert creatures of the CIA. Funding was funnelled through one of the CIA’s many front groups, the National Committee for a Free Europe. (See p.18.) This was revealed in the late 1960s but continued until 1972 when Congress began covering its budget. Still proud of its role in the Cold War, the RFE/RL’s website now brags that the “news and information” it aimed at “audiences behind the Iron Curtain,” “played a significant role in the collapse of communism....”2

U.S. Planting False Stories Common Cold War Tactic

The New York Times in 2000 revealed a classified history of CIA's covert 1953 operation in Iran to oust the prime minister and bolster Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. It included planting articles and editorial cartoons in newspapers. The CIA used disinformation tactics in Latin America, using radio broadcasts under the name Voice of Liberation to help topple the government of Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala in 1954. It used similar tactics in Chile to discredit Socialist President Salvador Allende who died in a 1973 coup when forces loyal to Augusto Pinochet overthrew his government.

U.S. Government Has Long Used Propaganda against the American People

During the early years of the cold war, [prominent writers and artists, from Arthur Schlesinger Jr. to Jackson Pollock] were supported, sometimes lavishly, always secretly, by the C.I.A. as part of its propaganda war against the Soviet Union. It was perhaps the most successful use of “soft power” in American history.

NYT 1977: Worldwide Propaganda Network Built by the C.I.A.

One of the C.I.A.'s first major ventures was broadcasting, Although long suspected, it was reported definitively only a few years ago that until 1971 the agency supported both Radio Free Europe, which continues, with private financing, to broadcast to the nations of Eastern Europe, and Radio Liberty, which is beamed at the Soviet Union itself. The C.I.A.'s participation in those operations was shielded from public view by two front groups, the Free Europe Committee and the American Committee for Liberation, both of which also engaged in a variety of lesser‐known propaganda operations. The American Committee for Liberation financed a Munich‐based group, the Institute for the Study of the U.S.S.R., a publishing and research house that, among other• things, compiles the widely used reference volume “Who's Who in the U.S.S.R.” The Free Europe Committee published the magazine East Europe, distributed in this country as well as abroad, and also operated the Free Europe Press Service. Far more obscure were two other C.I.A. broadcasting ventures, Radio Free Asia and a rather tenuous operation known as Free Cuba Radio. Free Cuba Radio, established in the early 1960's, did not broadcast from its own transmitters but purchased air time from a number of commercial radio stations in Florida and Louisiana.

Fantastic Truths, Compelling Lies: Radio Free Europe and the Response to the Slánský Trial in Czechoslovakia

This article examines the coverage by Radio Free Europe (RFE) of the show trial of Rudolf Slánský in 1952 and contrasts this coverage with documents on the response to the trial within Czechoslovakia. RFE aggressively portrayed the trial as a pack of lies and condemned its anti-Semitism as not authentically Czechoslovak. The response within Czechoslovakia was more much nuanced. Most publicly accepted the trial as valid and acted in ways that underscored that acceptance. Within this acceptance, however, they varied from the trial script and brought their own meanings to the story. Those meanings were not always ones that either RFE or Czechoslovak leaders would have recognised as true.

How America Backs Critics of Freedom

MUNICH -- A quiz: Which American radio station airs lengthy speeches portraying the United States as a decadent power and an unreliable ally? Which American station employs commentators openly contemptuous of Western democratic ideals? The answer is not some clandestine outfit sponsored by Moscow. The name of the station is Radio Liberty. It is part of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Inc., headquartered here in West Germany, but directed from Washington. These two radio stations are a key element in the Reagan administration's campaign to bring a stronger Western point of view to residents of Soviet bloc countries. Their entire budget -- $98 million this year -- comes from the American taxpayer, courtesy of Congress. Children of the Cold War, the radios were to serve as an electronic substitute for a free press for the peoples of the Soviet bloc. RFE covered Eastern Europe and RL the Soviet Union. Officially independent, the stations were in fact funded and loosely supervised by the Central Intelligence Agency. But the CIA was always careful throughout the 1950s and the 1960s not to dictate the contents of broadcasts. Editorial control was left to the fairly autonomous RFE/RL management. Later in the 1970s, when the CIA connection was publicly exposed, supervision of the stations was transferred to the Board of International Broadcasting (BIB), appointed by the president. And herein lies an inherent contradiction: the radios are expected simultaneously to act as the authentic voice of their East European and Soviet audiences and as an instrument of U.S. foreign policy.

"We'll know our disinformation program is complete when everything the American public believes is false." - William J. Casey, CIA Director (1981)

i honestly think too many of you accepted at face value that this image was secretly exclusively about communism

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ 📹 Injured children are pulled from the rubble and wreckage that remains of the Quran studies school inside the Fatima Al-Zahraa Mosque, in the Al-Daraj neighborhood of Gaza City, following an Israeli occupation airstrike that killed 10 civilians, mostly children, and wounded many others. ]

🇮🇱⚔️🇵🇸 🚀🏘️💥🚑 🚨

230 DAYS OF GENOCIDE IN GAZA: RAFAH AND KARM ABU SALEM BORDER CROSSINGS REMAIN CLOSED, ONE HOSPITAL RAIDED BY IOF, SECOND HOSPITAL CLOSES, MASS MURDER CAMPAIGN CONTINUES AS OVER 115'000 CASUALTIES ARE RECORDED

On 230th day of the Israeli occupation's ongoing special genocide operation in the Gaza Strip, the Israeli occupation forces (IOF) committed a total of 9 new massacres of Palestinian families, resulting in the deaths of no less than 91 Palestinian civilians, mostly women and children, while another 21 others were wounded over the previous 24-hours.

It should be noted that as a result of the constant Israeli bombardment of Gaza's healthcare system, infrastructure, residential and commercial buildings, local paramedic and civil defense crews are unable to recover countless hundreds, even thousands of victims who remain trapped under the rubble, or who's bodies remain strewn across the streets of Gaza.

For the 17th consecutive day, the Israeli occupation forces closed the Rafah and Karm Abu Salem border crossings, south of the city of Rafah, in the southern Gaza Strip, blocking thousands of humanitarian aid trucks from entering Gaza, and preventing hundreds of critically wounded and severely sick Palestinians from leaving the enclave for treatment abroad.

Commenting on the closure, the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) warned on Wednesday that "thousands of families still in Rafah need aid."

"WFP distributed food until it ran out. With little aid coming in from southern crossings and our warehouses still inaccessible, remaining food stocks have only supported 50'000 hot meals a day," the WFP said in a post to the social media platform X.

"We need safe and sustained access," the WFP added.

Due to the continued closure of Gaza's largest border crossings, not only are food, medicine and medical supplies in short supply, but also fuel for generators.

As a result of the fuel shortage, Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital in Deir al-Balah, in the central Gaza Strip, said it would cease providing healthcare services "within two hours" due to running out of fuel.

Appeals were made by the hospital calling for more fuel to continue its operations, but to no avail.

Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital is one of the last remaining hospitals still functioning in the Gaza Strip, serving an inordinately large percentage of the Palestinian population in central Gaza, as the Israeli occupation's ongoing bombing and shelling, along with the raid of several hospitals and the closure of Gaza's border crossings, have put the vast majority of the enclave's hospitals and healthcare centers out of service.

Previously, the Israeli occupation army destroyed a multitude of healthcare facilities in Gaza, demolishing and bombing several medical centers, including the Al-Shifa medical complex in Gaza City, one of the largest hospitals in Gaza at the start of the genocide.

The occupation army also destroyed several other hospitals, leaving piles of rubble in place of the medical institutions that once operated in Gaza.

Local medical sources say Al-Awda and Kamal Adwan Hospitals remain the last two hospitals in operation in the northern Gaza Strip, which are barely functioning at the time of publishing, following 8 months of raids, blockade, siege and bombardment.

However, in an example of the Israeli occupation's ongoing assault on what remains of Gaza's healthcare system, on Wednesday, the occupation army stormed Al-Awda Hospital in Jabalia.

According to reporting in the local media, occupation forces stormed Al-Awda Hospital, forcing medical personnel and patients to leave the hospital towards the west of Gaza City following the arrest of at least one member of the hospital's staff.

“There remain 14 employees in the hospital, accompanied by 11 injured people and companions. They refused to evacuate unless ambulances were present to evacuate the wounded," a local medical source told the Palestinian media.

Beginning on Sunday, May 19th, the Israeli occupation forces began a massive assault on the city of Jabalia and the Refugee Camp of the same name, demanding local residents evacuate their homes and shelters and forcing them towards Gaza City.

Al-Awda Hospital is considered to be the only hospital to provide orthopedic, gynecological, and obstetrics services in the northern Gaza Strip, while also providing services for general surgery, emergency and trauma care, specialized clinics, radiology and also had a functioning lab.

At least 148 people were trapped in Al-Awda Hospital during the time of the siege, while their fates remain unknown since the time of the raid, though some medical staff were seen evacuating on foot.

Meanwhile, the Israeli occupation forces (IOF) continued massacreing entire families in the Gaza Strip, killing and wounding dozens of civilians, mostly children, over the last day, with massive bombing and shelling targeting residential areas of the Palestinian enclave.

In Gaza's north, in the latest occupation atrocity, Israeli reconnaissance aircraft bombed a gathering of civilians near a gas station in the Al-Zaytoun neighborhood, southeast of Gaza City, killing at least 10 civilians, including several children, and wounding more than 20 others.

Similarly, Zionist air forces bombed Palestinians as they evacuated a shelter for displaced civilians in the Jabalia Refugee Camp, in the northern Gaza Strip, martyring four citizens and wounding several others.

In yet another genocidal mass murder event, Israeli occupation forces bombed a residential home in the Al-Daraj neighborhood in central Gaza City, leading to the deaths of 16 civilians, including at least 10 children, while a number of others were wounded in the attack.

Another 10 civilians were killed, and many others wounded, mostly children, after IOF fighter jets bombed a Quran studies school inside the Fatima Al-Zahraa Mosque, in the Al-Daraj neighborhood of central Gaza City.

In yet another airstrike, occupation forces bombed the Shabat family home on Al-Ma'amel Street, also in the Al-Daraj neighborhood of Gaza City, resulting in the deaths of 5 Palestinian civilians, while a further bombing targeted a residential apartment in the Tal al-Hawa neighborhood, south of Gaza City, killing one civilian and wounding several others.

The Israeli occupation army also pummeled the city of Jabalia, targeting several neighborhoods, including air assaults on Blocks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, along with Riad Al-Saliheen Square, also the Al-Qasaib neighborhood up to the Aisha Mosque, Ezbet Mallin, Al-Ajarma Street, Tal al-Zaatar, and the northern neighborhoods up to the Sheikh Zayed Towers, the Ezbet Abd Rabbo and Hay Al-Salem neighborhoods.

Bombings further targeted a gathering of civilians in front of the Abu Hussein School, leading to the deaths of four Palestinians, while five more civilians were killed when the IOF bombed a house belonging to the Alloun family in the Al-Jarn area of the Jabalia Camp.

The occupation army also burned down entire residential squares in the area of the Jabalia Camp's police station, along with neighborhoods in the eastern and northern areas of the Camp.

The mass bombing in Jabalia didn't end there, occupation forces also destroyed a five-story residential building belonging to the Al-Ajrami family, in the Al-Faluga neighborhood of the Jabalia Camp, while in nearby Beit Hanoun, occupation forces advanced towards the entrance of the town while laying siege to local schools operating as shelters for displaced Palestinian families.

The slaughter continued in central Gaza when IOF warplanes bombed a residential home behind the Al-Orouba School, north of the Nuseirat Refugee Camp, murdering 7 civilians and wounding a number of others.

Following that, the Israeli occupation army bombed a residential house belonging to the Shihab family in the Nuseirat Camp, resulting in the deaths of 8 Palestinians, the majority of which being children and women, while several others were wounded in the assault. The number of deaths is expected to rise due to the critical nature of the injuries sustained by the wounded.

Yet another bombing by the Zionist occupation army targeted a house belonging to the Al-Shami family, in neighborhoods west of the Nuseirat Camp, resulting in the martyredom of 8 civilians and injuring many others.

Yet another occupation airstrike targeted a house belonging to the Al-Shaer family near Lafat Badr, northwest of the city of Rafah, in the southern Gaza Strip, resulting in the death of a civilian.

Occupation Merkava tanks also entered Block 0 south of Rafah along the Egyptian border, west of the Salah al-Din Gate, razing the entire area and advancing further west, while Zionist artillery shelling targeted the Al-Awda roundabout.

As a result of the Israeli occupation's ongoing special genocide operation in the Gaza Strip, the current death toll now exceeds 35'800 Palestinians killed, including over 15'000 children and 10'000 women, while another 80'011 others were wounded since the start of the current round of Zionist aggression, beginning with the events of October 7th, 2023.

May 23rd, 2024.

#source1

#source2

#source3

#source4

#source5

#source6

#source7

#source8

#source9

#videosource

@WorkerSolidarityNews

#gaza#gaza strip#gaza news#gaza war#war in gaza#genocide in gaza#gaza genocide#israeli genocide#genocide#israeli war crimes#war crimes#crimes against humanity#israeli occupation#palestine#palestine news#palestinians#free palestine#occupation#gaza conflict#israel palestine conflict#politics#news#geopolitics#world news#global news#international news#war#breaking news#israel#current events

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

III. Toward an Anarchist Film Theory

In his article “What is Anarchist Cultural Studies?” Jesse Cohn argues that anarchist cultural studies (ACS) can be distinguished from critical theory and consumer-agency theory along several trajectories (Cohn, 2009: 403–24). Among other things, he writes, ACS tries “to avoid reducing the politics of popular culture to a simplistic dichotomy of ‘reification’ versus ‘resistance’” (ibid., 412). On the one hand, anarchists have always balked at the pretensions of “high culture” even before these were exposed and demystified by the likes of Bourdieu in his theory of “cultural capital.” On the other hand, we always sought ought and found “spaces of liberty — even momentary, even narrow and compromised — within capitalism and the State” (ibid., 413). At the same time, anarchists have never been content to find “reflections of our desires in the mirror of commercial culture,” nor merely to assert the possibility of finding them (ibid.). Democracy, liberation, revolution, etc. are not already present in a culture; they are among many potentialities which must be actualized through active intervention.

If Cohn’s general view of ACS is correct, and I think it is, we ought to recognize its significant resonance with the Foucauldian tertia via outlined above. When Cohn claims that anarchists are “critical realists and monists, in that we recognize our condition as beings embedded within a single, shared reality” (Cohn, 2009: 413), he acknowledges that power actively affects both internal (subjective) existence as well as external (intersubjective) existence. At the same time, by arguing “that this reality is in a continuous process of change and becoming, and that at any given moment, it includes an infinity — bounded by, situated within, ‘anchored’ to the concrete actuality of the present — of emergent or potential realities” (ibid.), Cohn denies that power (hence, reality) is a single actuality that transcends, or is simply “given to,” whatever it affects or acts upon. On the contrary, power is plural and potential, immanent to whatever it affects because precisely because affected in turn. From the standpoint of ACS and Foucault alike, then, culture is reciprocal and symbiotic — it both produces and is produced by power relations. What implications might this have for contemporary film theory?

At present the global film industry — not to speak of the majority of media — is controlled by six multinational corporate conglomerates: The News Corporation, The Walt Disney Company, Viacom, Time Warner, Sony Corporation of America, and NBC Universal. As of 2005, approximately 85% of box office revenue in the United States was generated by these companies, as compared to a mere 15% by so-called “independent” studios whose films are produced without financing and distribution from major movie studios. Never before has the intimate connection between cinema and capitalism appeared quite as stark.

As Horkheimer and Adorno argued more than fifty years ago, the salient characteristic of “mainstream” Hollywood cinema is its dual role as commodity and ideological mechanism. On the one hand, films not only satisfy but produce various consumer desires. On the other hand, this desire-satisfaction mechanism maintains and strengthens capitalist hegemony by manipulating and distracting the masses. In order to fulfill this role, “mainstream” films must adhere to certain conventions at the level of both form and content. With respect to the former, for example, they must evince a simple plot structure, straightforwardly linear narrative, and easily understandable dialogue. With respect to the latter, they must avoid delving deeply into complicated social, moral, and philosophical issues and should not offend widely-held sensibilities (chief among them the idea that consumer capitalism is an indispensable, if not altogether just, socio-economic system). Far from being arbitrary, these conventions are deliberately chosen and reinforced by the culture industry in order to reach the largest and most diverse audience possible and to maximize the effectiveness of film-as-propaganda.

“Avant garde” or “underground cinema,” in contrast, is marked by its self — conscious attempt to undermine the structures and conventions which have been imposed on cinema by the culture industry — for example, by presenting shocking images, employing unusual narrative structures, or presenting unorthodox political, religious, and philosophical viewpoints. The point in so doing is allegedly to “liberate” cinema from its dual role as commodity and ideological machine (either directly, by using film as a form of radical political critique, or indirectly, by attempting to revitalize film as a serious art form).

Despite its merits, this analysis drastically oversimplifies the complexities of modern cinema. In the first place, the dichotomy between “mainstream” and “avant-garde” has never been particularly clear-cut, especially in non-American cinema. Many of the paradigmatic European “art films” enjoyed considerable popularity and large box office revenues within their own markets, which suggests among other things that “mainstream” and “avant garde” are culturally relative categories. So, too, the question of what counts as “mainstream” versus “avant garde” is inextricably bound up in related questions concerning the aesthetic “value” or “merit” of films. To many, “avant garde” film is remarkable chiefly for its artistic excellence, whereas “mainstream” film is little more than mass-produced pap. But who determines the standards for cinematic excellence, and how? As Dudley Andrews notes,

[...] [C]ulture is not a single thing but a competition among groups. And, competition is organized through power clusters we can think of as institutions. In our own field certain institutions stand out in marble buildings. The NEH is one; but in a different way, so is Hollywood, or at least the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Standard film critics constitute a sub-group of the communication institution, and film professors make up a parallel group, especially as they collect in conferences and in societies (Andrews, 1985: 55).

Andrews’ point here echoes one we made earlier — namely, that film criticism itself is a product of complicated power relations. Theoretical dichotomies such as “mainstream versus avant-garde” or “art versus pap” are manifestations of deeper socio-political conflicts which are subject to analysis in turn.

Even if there is or was such a thing as “avant-garde” cinema, it no longer functions in the way that Horkheimer and Adorno envisaged, if it ever did. As they themselves recognized, one of the most remarkable features of late capitalism is its ability to appropriate and commodify dissent. Friedberg, for example, is right to point out that flaneurie began as a transgressive institution which was subsequently captured by the culture industry; but the same is true even of “avant-garde” film — an idea that its champions frequently fail to acknowledge. Through the use of niche marketing and other such mechanisms, the postmodern culture industry has not only overcome the “threat” of the avant-garde but transformed that threat into one more commodity to be bought and sold. Media conglomerates make more money by establishing faux “independent” production companies (e.g., Sony Pictures Classics, Fox Searchlight Pictures, etc) and re-marketing “art films” (ala the Criterion Collection) than they would by simply ignoring independent, underground, avant-garde, etc. cinema altogether.

All of this is by way of expanding upon an earlier point — namely, that it is difficult, if not impossible, to determine the extent to which particular films or cinematic genres function as instruments of socio-political repression — especially in terms of simple dichotomies such as “mainstream” versus “avant-garde.” In light of our earlier discussion of Foucault, not to speak of Derrida, this ought not to come as a surprise. At the same time, however, we have ample reason to believe that the contemporary film industry is without question one of the preeminent mechanisms of global capitalist cultural hegemony. To see why this is the case, we ought briefly to consider some insights from Gilles Deleuze.

There is a clear parallel between Friedberg’s mobilized flaneurial gaze and what Deleuze calls the “nomadic” — i.e., those social formations which are exterior to repressive modern apparatuses like State and Capital (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987: 351–423). Like the nomad, the flaneur wanders aimlessly and without a predetermined telos through the striated space of these apparatuses. Her mobility itself, however, belongs to the sphere of non-territorialized smooth space, unconstrained by regimentation or structure, free-flowing, detached. The desire underlying this mobility is productive; it actively avoids satisfaction and seeks only to proliferate and perpetuate its own movement. Apparatuses of repression, in contrast, operate by striating space and routinizing, regimenting, or otherwise constraining mobile desire. They must appropriate the nomadic in order to function as apparatuses of repression.

Capitalism, however one understands its relationship to other repressive apparatuses, strives to commodify flaneurial desire, or, what comes to the same, to produce artificial desires which appropriate, capture, and ultimately absorb flaneurial desire (ibid., esp. 424–73). Deleuze would agree with Horkheimer and Adorno that the contemporary film industry serves a dual role as capture mechanism and as commodity. It not only functions as an object within capitalist exchange but as an ideological machine that reinforces the production of consumer-subjects. This poses a two-fold threat to freedom, at least as freedom is understood from a Deleuzean perspective: first, it makes nomadic mobility abstract and virtual, trapping it in striated space and marshaling it toward the perpetuation of repressive apparatuses; and second, it replaces the free-flowing desire of the nomadic with social desire — that is, it commodifies desire and appropriates flaneurie as a mode of capitalist production.

The crucial difference is that for Deleuze, as for Foucault and ACS, the relation between the nomadic and the social is always and already reciprocal. In one decidedly aphoristic passage, Deleuze claims there are only forces of desire and social forces (Deleuze & Guattari, [1972] 1977: 29). Although he tends to regard desire as a creative force (in the sense that it produces rather than represses its object) and the social as a force which “dams up, channels, and regulates” the flow of desire (ibid., 33), he does not mean to suggest that there are two distinct kinds of forces which differentially affect objects exterior to themselves. On the contrary, there is only a single, unitary force which manifests itself in particular “assemblages” (ibid.). Each of these assemblages, in turn, contains within itself both desire and various “bureaucratic or fascist pieces” which seek to subjugate and annihilate that desire (Deleuze & Guattari, 1986: 60; Deleuze & Parnet, 1987: 133). Neither force acts or works upon preexistent objects; rather everything that exists is alternately created and/or destroyed in accordance with the particular assemblage which gives rise to it.

There is scarcely any question that the contemporary film industry is subservient to repressive apparatuses such as transnational capital and the government of the United States. The fact that the production of films is overwhelmingly controlled by a handful of media conglomerates, the interests of which are routinely protected by federal institutions at the expense of consumer autonomy, makes this abundantly clear. It also reinforces the naivety of cultural studies, whose valorization of consumer subcultures appears totally impotent in the face of such enormous power. As Richard Hoggart notes,

Studies of this kind habitually ignore or underplay the fact that these groups are almost entirely enclosed from and are refusing even to attempt to cope with the public life of their societies. That rejection cannot reasonably be given some idealistic ideological foundation. It is a rejection, certainly, and in that rejection may be making some implicit criticisms of the ‘hegemony,’ and those criticisms need to be understood. But such groups are doing nothing about it except to retreat (Hoggart, 1995: 186).

Even if we overlook the Deleuzean/Foucauldian/ACS critique — viz., that cultural studies relies on a theoretically problematic notion of consumer “agency” — such agency appears largely impotent at the level of praxis as well.

Nor is there any question that the global proliferation of Hollywood cinema is part of a broader imperialist movement in geopolitics. Whether consciously or unconsciously, American films reflect and reinforce uniquely capitalist values and to this extent pose a threat to the political, economic, and cultural sovereignty of other nations and peoples. It is for the most part naïve of cultural studies critics to assign “agency” to non-American consumers who are not only saturated with alien commodities but increasingly denied the ability to produce and consume native commodities. At the same time, none of this entails that competing film industries are by definition “liberatory.” Global capitalism is not the sole or even the principal locus of repressive power; it is merely one manifestation of such power among many. Ostensibly anti-capitalist or counter-hegemonic movements at the level of culture can and often do become repressive in their own right — as, for example, in the case of nationalist cinemas which advocate terrorism, religious fundamentalism, and the subjugation of women under the banner of “anti-imperialism.”

The point here, which reinforces several ideas already introduced, is that neither the American film industry nor film industries as such are intrinsically reducible to a unitary source of repressive power. As a social formation or assemblage, cinema is a product of a complex array of forces. To this extent it always and already contains both potentially liberatory and potentially repressive components. In other words, a genuinely nomadic cinema — one which deterritorializes itself and escapes the overcoding of repressive state apparatuses — is not only possible but in some sense inevitable. Such a cinema, moreover, will emerge neither on the side of the producer nor of the consumer, but rather in the complex interstices that exist between them. I therefore agree with Cohn that anarchist cultural studies (and, by extension, anarchist film theory) has as one of its chief goals the “extrapolation” of latent revolutionary ideas in cultural practices and products (where “extrapolation” is understood in the sense of actively and creatively realizing possibilities rather than simply “discovering” actualities already present) (Cohn, 2009: 412). At the same time, I believe anarchist film theory must play a role in creating a new and distinctively anarchist cinema — “a cinema of liberation.”

Such a cinema would perforce involve alliances between artists and audiences with a mind to blurring such distinctions altogether. It would be the responsibility neither of an elite “avant-garde” which produces underground films, nor of subaltern consumer “cults” which produce fanzines and organize conventions in an attempt to appropriate and “talk back to” mainstream films. As we have seen, apparatuses of repression easily overcode both such strategies. By effectively dismantling rigid distinctions between producers and consumers, its films would be financed, produced, distributed, and displayed by and for their intended audiences. However, far from being a mere reiteration of the independent or DIY ethic — which, again, has been appropriated time and again by the culture industry — anarchist cinema would be self — consciously political at the level of form and content; its medium and message would be unambiguously anti — authoritarian, unequivocally opposed to all forms of repressive power.

Lastly, anarchist cinema would retain an emphasis on artistic integrity — the putative value of innovative cinematography, say, or compelling narrative. It would, in other words, seek to preserve and expand upon whatever makes cinema powerful as a medium and as an art-form. This refusal to relegate cinema to either a mere commodity form or a mere vehicle of propaganda is itself an act of refusal replete with political potential. The ultimate liberation of cinema from the discourse of political struggle is arguably the one cinematic development that would not, and could not, be appropriated and commodified by repressive social formations.

In this essay I have drawn upon the insights of Foucault and Deleuze to sketch an “anarchist” approach to the analysis of film — on which constitutes a middle ground between the “top-down” theories of the Frankfurt School and the “bottom-up” theories of cultural studies. Though I agree with Horkheimer and Adorno that cinema can be used as an instrument of repression, as is undoubtedly the case with the contemporary film industry, I have argued at length that cinema as such is neither inherently repressive nor inherently liberatory. Furthermore, I have demonstrated that the politics of cinema cannot be situated exclusively in the designs of the culture industry nor in the interpretations and responses of consumer-subjects. An anarchist analysis of cinema must emerge precisely where cinema itself does — at the intersection of mutually reinforcing forces of production and consumption.

#cinema#film theory#movies#anarchist film theory#culture industry#culture#deconstruction#humanism#truth#the politics of cinema#anarchism#anarchy#anarchist society#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#daily posts#libraries#leftism#social issues#anarchy works#anarchist library#survival#freedom

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

i am opening commissions! :3

and for the first time in ever, i'm making an ✨official✨ post about it! so excited to get a bunch of bots in my replies! but if you are a cool, real human who has funky little guys in your head, good news! i want to draw YOUR characters!!

here's my (very affordable) price chart, in USD:

these prices are just to test the waters, and if i see a high enough demand for my work they will eventually be subject to change (so get it while it's hot).

any additional characters as well as the inclusion of a simple background will be an additional $5 each for busts, $10 for half body and $15 for full body. payment will be accepted UPFRONT via paypal only.

expand this post for a better look at what i'm willing to do, my work, and my terms!

will do:

- suggestive/nsfw ✅

- light elements of mecha ✅

- gore ✅

- furry/anthro ✅

- simple backgrounds ✅

will NOT do:

- realism ❌

- exactly replicating other artists' styles ❌

- heavy mecha ❌

- complex backgrounds ❌

- over 4 characters ❌

a look at my style:

artwork i create as a commission is for personal use only, including in profile pictures, banners, closed ttrpg games, for personal collections and for use on merchandise that is NOT being mass produced or distributed for profit. commissioners may repost/share their commissioned work as long as they do not take credit or otherwise attempt to obscure my involvement in their creation. if you would like me to create art for commercial purposes such as merch please specify that in your initial direct message and we can have a more in-depth conversation about potential payment plans and/or royalties.

i reserve the right to decline any commission proposals, for any reason.

#kc107 art#107 txt#digital art#digital aritst#digital drawing#digital illustration#character art#character drawing#character illustration#oc art#oc artist#character design#character commissions#character comms#oc commissions#oc comms#art#artists on tumblr#self promo#procreate#human artist

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

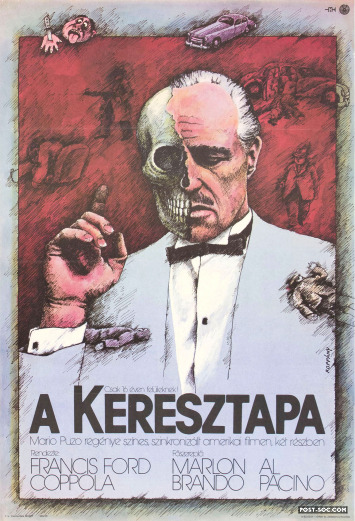

Beyond the Frame | A Reflective Essay on the History of Polish, Czech, and Hungarian Movie Poster Art

In the dim light cast between censorship and creativity, between imported spectacle and domestic interpretation, a unique visual culture emerged behind the Iron Curtain. In Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary, the humble movie poster became an unlikely arena for radical artistic expression. These were not merely promotional images; they were acts of translation, rebellion, and poetic vision. When American films reached Eastern Europe—scrubbed, dubbed, sometimes truncated—their glossy Western allure was peeled away and reconstructed by local artists into something deeper, stranger, and startlingly original. Especially notable is the use of abstraction, symbolism, and psychological metaphor that defined Polish, Czech, and Hungarian poster design from the 1950s to the late 1980s.

Cinema as Subjective Canvas

In the West, a film poster is commercial shorthand—stars, titles, and taglines rendered for maximum allure. But in mid-century Central Europe, posters were conceived not as marketing tools but as interpretations of film. This was possible because the films were distributed through state-controlled channels, which didn’t rely on consumer-driven advertising. Artists weren’t tasked with "selling" the film to the masses. Instead, they were often given titles and basic plot summaries—or, at best, preview screenings—and invited to create work that captured the essence of a film rather than its imagery.

This freedom, paradoxically enabled by a rigid political system, allowed artists to take enormous conceptual and aesthetic liberties. It also created fertile ground for the blending of avant-garde traditions—Constructivism, Surrealism, Expressionism, and Pop Art—resulting in a regional poster tradition that is now recognized as one of the richest and most idiosyncratic in design history.

The Polish School: Interpretation Over Illustration

Poland’s poster scene was particularly fertile, giving rise to the so-called Polish School of Posters in the 1950s. Led by figures like Henryk Tomaszewski, Jan Lenica, and Waldemar Świerzy, this movement elevated the poster to a medium of high art. Their designs rejected realism in favor of metaphor. A Polish poster for Jaws by Andrzej Krajewski might show a stylized swirl of water and teeth, abstracting the shark into a graphic pattern. For Apocalypse Now, one might see not helicopters or war scenes, but a disembodied head, part-masked, part-erased, floating in a red haze.

These designs stripped American cinema of its consumer packaging and re-presented it through a psychological or philosophical lens. Even genres like horror and action became meditations on fear, power, and alienation. The Polish approach was deeply personal, often humorous or grotesque, and almost always indirect.

Czech Surrealism: Playful Dissonance

In Czechoslovakia, poster artists like Zdeněk Ziegler, Karel Vaca, and Dobroslav Foll developed a style rooted in absurdism and surrealism. Where the Polish school leaned into painterly abstraction, the Czech approach often favored collage, visual puns, and theatrical imagery. American films like Grease or Planet of the Apes would be rendered in ways that deflated their commercial sheen—using bizarre juxtapositions, distorted mannequins, or torn photographs.

This reflected the country’s broader surrealist tradition—exemplified by filmmakers like Jan Švankmajer and artists like Toyen—and its subversive humor. Czech posters could be deeply irreverent, yet still evocative, often hinting at the absurdity of American idealism or the disjointed experience of watching foreign dreams play out in a constrained society.

Hungary: Modernism Meets the Mythic

Hungarian poster design, while sometimes overlooked next to its Polish and Czech neighbors, was no less radical. Artists like István Balogh, György Kemenes, András Máté, and Géza Gyalog developed a distinct visual language that fused graphic modernism with folk motifs and Bauhaus geometry. Hungarian posters were often cleaner in form but densely layered in meaning.

Their abstraction leaned toward minimalist surrealism: a floating eye, a single chair, a looming silhouette. A Hungarian poster for The Godfather might depict not Marlon Brando but a red flower bleeding across black paper. 2001: A Space Odyssey could be rendered as a stark black obelisk surrounded by primitive brushwork. The effect was often mystical, symbolic, and darkly introspective.

These artists were deeply influenced by the Hungarian avant-garde of the 1920s and 30s, and later, by the underground art scenes of Budapest. Their posters navigated a fine line—evoking inner worlds while commenting on the alien narratives imported from abroad.

Visual Resistance and Personal Codes

Across all three countries, abstraction was not simply an artistic choice—it was also a political strategy. Literalism risked censorship; ambiguity offered protection. These posters functioned as covert acts of resistance. By refusing to glorify American icons, by bending and twisting Hollywood's narratives, artists reclaimed interpretive power.

Moreover, in using abstract and expressionist styles, they left room for viewers to project their own readings. A viewer in Warsaw or Prague might see a poster for Taxi Driver and not recognize Robert De Niro, but feel the character's descent into isolation and violence through disjointed visual cues—a blood-red background, a distorted face, a fractured street lamp.

Legacy and Revival

With the fall of communism in 1989, the poster culture of Central Europe changed dramatically. Market liberalization ushered in glossy, uniform posters that mirrored global branding strategies. The old school of interpreters gave way to marketing departments and Photoshop.

Yet the legacy of Polish, Czech, and Hungarian poster art endures—not just in museums and retrospectives but in the resurgence of alternative movie poster design in the West. Collectors and cinephiles have revived interest in these works, and contemporary artists often draw inspiration from their daring, emotionally intelligent style.

In a time of algorithmically generated content, these posters remind us that art can illuminate what lies behind the screen, revealing the psyche beneath the spectacle.

Conclusion: Posters as Portraits of Imagination

The movie posters of Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary from the Cold War era are not merely historical artifacts; they are poetic documents. They reflect a time when artists were tasked not with selling fantasy, but with interpreting it—translating the distant dreams of America into images shaped by repression, wit, solitude, and resilience.

In abstracting the Hollywood dream machine, these artists didn’t diminish it—they expanded it. They asked not what a movie was about, but why it mattered. And in doing so, they gave us a parallel cinema—not projected on a screen, but drawn with ink, paint, and vision on fragile sheets of paper, speaking volumes without a single word of dialogue.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

adoptable - Hazbin Hotel 10$ (PayPal only)

I designed this cute bunny demon girl as a Hazbin Hotel character. You can change the fandom if you want tho. She is 10 USD via PayPal

Rules

Ownership Transfer: Upon purchase, ownership of the character adoptable ("Character") is transferred from the creator/seller to the buyer.

Non-Refundable: All purchases of character adopts are final and non-refundable.

Personal Use Only: The purchased character is for personal use only. Buyers may not resell or redistribute.

Modification Rights: Buyers have the right to modify the purchased character's design to suit their preferences.

Credit: While not mandatory, crediting the original creator of the character design is appreciated, especially if the modified design is shared publicly.

No Commercial Use: The character may not be used for commercial purposes without explicit permission from the original creator.

Character Reproduction: Reproducing the character design for mass distribution is prohibited without permission from the original creator.

Resale and Trade: Buyers may resell or trade the character adopt, but must ensure that the new owner agrees to abide by these terms of service. You can’t resell for a grater price unless there is extra art of the character.

Changes to Terms: The original creator reserves the right to update or modify these terms of service at any time. Buyers will be notified of any changes and are expected to adhere to the updated terms.

#adorable#character adopt#adoptable#digital art#art#oc#hazbin hotel#hazbin art#vivziepop#hazbin hotel edit#hazbin hotel oc#original character#oc adopt#furry adopt#hazbin hotel fanart#hazbin alastor#hazbin lucifer#hazbin angel dust#illustration#character design#furry character#character art#cartoon#helluva boss#helluva fanart#helluva boss oc#hazbin fanart#oc art#drawing#hazbin

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Scholars often dismiss physique references to ancient Greece as a mere ruse or rhetorical framework--a "classical alibi" or "discourse of validation"--to avoid censorship. But an examination of the lives of the founders, contributors, and members of the [physique studio and pictorial] Grecian Guild [1955-1968] tells a different story. The Grecian Guild was instrumental in helping a community of men struggling to find a discourse to explain and valorize their sense of themselves, particularly men outside of urban gay enclaves. Benson and Bullock [the founders of the Grecian Guild] took a discourse about ancient Greece that gay men had been using for nearly a hundred years and gave it mass distribution. They used it like gay men used reference to "the Greeks" or Mary Renault novels--as a way to signal their homosexuality. It was a rallying cry that brought in customers and helped them imagine a better world. As historian and biographer Benjamin Wise argues about the way Alexander Percy used the language of Hellenism, it was "a way of speaking out and covering up at the same time."

Invoking classical traditions in order to make an argument for gay rights has been largely forgotten in the twenty-first century, as such a line of argumentation has become politically and historiographically problematic. Indeed, much of modern LGBT historical scholarship and queer theory has asserted that a homosexual identity is a creation of a modern, capitalist world--that homosexual behavior in ancient cultures was understood in very different terms from the way it is today. Invoking classical antiquity also smacks of a Western bias that privileges European ancestry over other cultural and historical influences. Such arguments also raise the specter of pederasty and pedophilia--or at least age-discordant relationships--that play into the hands of gay rights opponents who relentlessly use the argument that gays recruit children to fight gay rights measures...

Despite these changes in cultural understandings and sensibilities, the use of the classical Greek trope to name gay organizations, periodicals, and commercial ventures continued for decades, even when the need for an alibi had eroded if not disappeared. The lambda or lowercase Greek "L" became one of the primary symbols of the 1970s gay liberation movement. During this same period Seattle's largest gay organization was the Dorian Group, and a Jacksonville, Florida-based gay magazine called itself David--a reference to Michelangelo's Renaissance statue--an indirect link to the classical tradition. Like the Grecian Guild, David offered membership in a fraternal organization with features such as a book club, a travel service, conventions, and even legal aid. As an online website, it continues to serve as one of Atlanta's premier LGBT news and entertainment sources.

...

While severely limited by the forces of censorship, the desire to create opportunities for customers to correspond, meet, and get acquainted attests to the palpable wish of gay men to connect with each other during this period. If few members attended a Grecian Guild convention, the possibility of doing so resonated widely. As a teenage Grecian Guild subscriber in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, Michael Denneny read the articles so carefully that he underlined the important parts. "That was proto-political organization, the agenda was very clear to me, and I think to everybody else who joined," Denneny remembered..."These magazines were really important to me," Denneny recalled. "They brought this whole possible world into being, which I'm not sure I could have visualized otherwise."

David K. Johnson, Buying Gay: How Physique Entrepreneurs Sparked a Movement

#queer history#thinking about aang and zuko's connection to the deep past#aang's strange displacement from his people and history#that means he has this distinct lived connection to a by-gone civilization and idyll#and then zuko's obsession with the air nomads#going to all their temples#and in the natla collecting all the nomad and avatar relics#then later their exploration of the sun warrior past#another ancient civilization whose philosophies they seek to adapt#and how both of these relate to aang and zuko's exploration of their gender and alternatives to contemporary masculinity#these fascinations with lost civilizations bring aang and zuko together too#and even force them to address assumptions about age-differences...#just a lot to unpack#just about how exploring other cultures and history thoroughly dislodges one's construction of reality#and opens up possibility

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

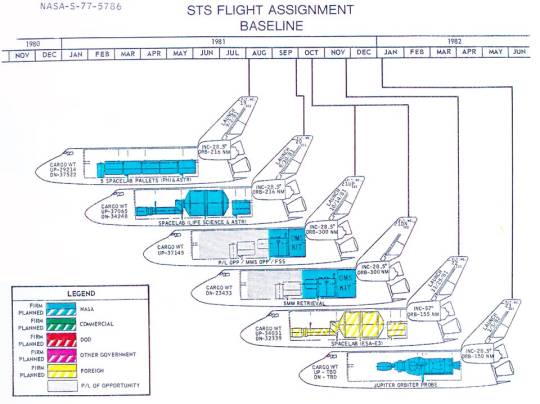

Cancelled Missions: NASA's October 1977 Space Shuttle Flight Itinerary

"Soon after President Richard Nixon gave his blessing to the Space Shuttle Program on January 5, 1972, NASA scheduled its first orbital flight for 1977, then for March 1978. By early 1975, the date had slipped to March 1979. Funding shortfalls were to blame, as were the daunting engineering challenges of developing the world's first reusable orbital spaceship based on 1970s technology. The schedule slip was actually worse than NASA let on: as early as January 32, 1975, an internal NASA document (marked 'sensitive') gave a '90% probability date' for the first Shuttle launch of December 1979.

In October 1977, Chester Lee, director of Space Transportation System (STS) Operations at NASA Headquarters, distributed the first edition of the STS Flight Assignment Baseline, a launch schedule and payload manifest for the first 16 operational Shuttle missions. The document was in keeping with NASA's stated philosophy that reusable Shuttle Orbiters would fly on-time and often, like a fleet of cargo airplanes. The STS Utilization and Operations Office at NASA's Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston had prepared the document, which was meant to be revised quarterly as new customers chose the Space Shuttle as their cheap and reliable ride to space.

The JSC planners assumed that six Orbital Flight Test (OFT) missions would precede the first operational Shuttle flight. The OFT flights would see two-man crews (Commander and Pilot) put Orbiter Vehicle 102 (OV-102) through its paces in low-Earth orbit. The planners did not include the OFT schedule in their document, but the May 30, 1980 launch date for their first operational Shuttle mission suggests that they based their flight schedule on the March 1979 first OFT launch date.

Thirteen of the 16 operational flights would use OV-102 and three would use OV-101. NASA would christen OV-102 Columbia in February 1979, shortly before it rolled out of the Rockwell International plant in Palmdale, California.

As for OV-101, its name was changed from Constitution to Enterprise in mid-1976 at the insistence of Star Trek fans. Enterprise flew in Approach and Landing Test (ALT) flights at Edwards Air Force Base in California beginning on February 15, 1977. ALT flights, which saw the Orbiter carried by and dropped from a modified 747, ended soon after the NASA JSC planners released their document.

The first operational Space Shuttle mission, Flight 7 (May 30 - June 3, 1980), would see Columbia climb to a 225-nautical-mile (n-mi) orbit inclined 28.5° relative to Earth's equator (unless otherwise stated, all orbits are inclined at 28.5°, the latitude of Kennedy Space Center in Florida). The delta-winged Orbiter would carry a three-person crew in its two-deck crew compartment and the bus-sized Long Duration Exposure Facility (LDEF) in its 15-foot-wide, 60-foot-long payload bay.

Columbia would also carry a 'payload of opportunity' - that is, an unspecified payload. The presence of a payload of opportunity meant that the flight had available excess payload weight capacity. Payload mass up would total 27,925 pounds. Payload mass down after the Remote Manipulator System (RMS) arm hoisted LDEF out of Columbia's payload bay and released it into orbit would total 9080 pounds.

A page from the STS Flight Assignment Baseline document of October 1977 shows payloads and other features of the first five operational Space Shuttle missions plus Flight 12/Flight 12 Alternate

During Flight 8 (July 1-3, 1980), Columbia would orbit 160 n mi above the Earth. Three astronauts would release two satellites and their solid-propellant rocket stages: Tracking and Data Relay Satellite-A (TDRS-A) with a two-stage Interim Upper Stage (IUS) and the Satellite Business Systems-A (SBS-A) commercial communications satellite on a Spinning Solid Upper Stage-Delta-class (SSUS-D).

Prior to release, the crew would spin the SBS-A satellite about its long axis on a turntable to create gyroscopic stability and raise TDRS-A on a tilt-table. After release, their respective solid-propellant stages would propel them to their assigned slots in geostationary orbit (GEO), 19,323 n mi above the equator. Payload mass up would total 51,243 pounds; mass down, 8912 pounds, most of which would comprise reusable restraint and deployment hardware for the satellites.

The TDRS system, which would include three operational satellites and an orbiting spare, was meant to trim costs and improve communications coverage by replacing most of the ground-based Manned Space Flight Network (MSFN). Previous U.S. piloted missions had relied on MSFN ground stations to relay communications to and from the Mission Control Center (MCC) in Houston. Because spacecraft in low-Earth orbit could remain in range of a given ground station for only a few minutes at a time, astronauts were frequently out of contact with the MCC.

On Flight 9 (August 1-6, 1980), Columbia would climb to a 160-n-mi orbit. Three astronauts would deploy GOES-D, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) weather satellite, and Anik-C/1, a Canadian communications satellite. Before release, the crew would raise the NOAA satellite and its SSUS-Atlas-class (SSUS-A) rocket stage on the tilt-table and spin up the Anik-C/1-SSUS-D combination on the turntable. In addition to the two named satellites, NASA JSC planners reckoned that Columbia could carry a 14,000-pound payload of opportunity. Payload mass up would total 36,017 pounds; mass down, 21,116 pounds.

Following Flight 9, NASA would withdraw Columbia from service for 12 weeks to permit conversion from OFT configuration to operational configuration. The JSC planners explained that the conversion would be deferred until after Flight 9 to ensure an on-time first operational flight and to save time by combining it with Columbia's preparations for the first Spacelab mission on Flight 11. The switch from OFT to operational configuration would entail removal of Development Flight Instrumentation (sensors for monitoring Orbiter systems and performance); replacement of Commander and Pilot ejection seats on the crew compartment upper deck (the flight deck) with fixed seats; power system upgrades; and installation of an airlock on the crew compartment lower deck (the mid-deck).

Flight 10 (November 14-16, 1980) would be a near-copy of Flight 8. A three-person Columbia crew would deploy TDRS-B/IUS and SBS-B/SSUS-D into a 160-n-mi-high orbit. The rocket stages would then boost the satellites to GEO. Cargo mass up would total 53,744 pounds; mass down, 11,443 pounds.

Flight 11 (December 18-25, 1980) would see the orbital debut of Spacelab. Columbia would orbit Earth 160 n mi high at 57° of inclination. NASA and the multinational European Space Research Organization (ESRO) agreed in August 1973 that Europe should develop and manufacture Spacelab pressurized modules and unpressurized pallets for use in the Space Shuttle Program. Initially dubbed the 'sortie lab,' Spacelab would operate only in the Orbiter payload bay; it was not intended as an independent space station, though many hoped that it would help to demonstrate that an Earth-orbiting station could be useful.

ESRO merged with the European Launcher Development Organization in 1975 to form the European Space Agency (ESA). Columbia's five-person crew for Flight 11 would probably include scientists and at least one astronaut from an ESA member country.

Flight 12 (January 30 - February 1, 1981), a near-copy of Flights 8 and 10, would see Columbia's three-person crew deploy TDRS-C/IUS and Anik-C/2/SSUS-D into 160-n-mi-high orbit. Payload mass up would total 53,744 pounds; mass down, 11,443 pounds.

JSC planners inserted an optional 'Flight 12 Alternate' (January 30 - February 4, 1981) into their schedule which, if flown, would replace Flight 12. Columbia would orbit 160 n mi above the Earth. Its three-person crew would deploy Anik-C/2 on a SSUS-D stage. The mission's main purpose, however, would be to create a backup launch opportunity for an Intelsat V-class satellite already scheduled for launch on a U.S. Atlas-Centaur or European Ariane I rocket. An SSUS-A stage would boost the Intelsat V from Shuttle orbit to GEO.

NASA JSC assumed that, besides the satellites, stages, and their support hardware, Columbia would for Flight 12 Alternate tote an attached payload of opportunity that would need to operate in space for five days to provide useful data (hence the mission's planned duration). Payload mass up would total 37,067 pounds; mass down, 17,347 pounds.

Space Shuttle Flights 13 through 18 would include the first orbital mission of the OV-101 Enterprise (Flight 17), during which astronauts would retrieve the LDEF payload deployed during Flight 7.

Flight 13 (March 3-8, 1981) would see three astronauts on board Columbia release NOAA's GOES-E satellite attached to an SSUS-D stage into a 160-n-mi-high orbit. OV-102 would have room for two payloads of opportunity: one attached at the front of the payload bay and one deployed from a turntable aft of the GOES-E/SSUS-D combination. Payload mass up would total 38,549 pounds; mass down, 23,647 pounds.

Flight 14 would last 12 days, making it the longest described in the STS Flight Assignment Baseline document. Scheduled for launch on April 7, 1981, it would carry a 'train' of four unpressurized Spacelab experiment pallets and an 'Igloo,' a small pressurized compartment for pallet support equipment. The Igloo, though pressurized, would not be accessible to the five-person crew. OV-102 would orbit 225 n mi high at an inclination of 57°. Mass up would total 31,833 pounds; mass down, 28,450 pounds.

Flight 15 (May 13-15, 1981) would be a near-copy of Flights 8, 10, and 12. OV-102 would transport to orbit a payload totaling 53,744 pounds; payload mass down would total 11,443 pounds. The JSC planners noted the possibility that none of the potential payloads for Flight 15 — TDRS-D and SBS-C or Anik-C/3 — would need to be launched as early as May 1981. TDRS-D was meant as an orbiting spare; if the first three TDRS operated as planned, its launch could be postponed. Likewise, SBS-C and Anik-C/3 were each a backup for the previously launched satellites in their series.

Flight 16 (June 16-23, 1981) would be a five-person Spacelab pressurized module flight aboard OV-102 in 160-n-mi-high orbit. Payloads of opportunity totaling about 18,000 pounds might accompany the Spacelab module; for planning purposes, a satellite and SSUS-D on a turntable behind the module was assumed. Payload mass up would total 35,676 pounds; mass down, 27,995 pounds.

Flight 17, scheduled for July 16-20, 1981, would see the space debut of Enterprise and the retrieval of the LDEF released during Flight 7. OV-101 would climb to a roughly 200-n-mi-high orbit (LDEF's altitude after 13.5 months of orbital decay would determine the mission's precise altitude).

Before rendezvous with LDEF, Flight 17's three-man crew would release an Intelsat V/SSUS-A and a satellite payload of opportunity. After the satellites were sent on their way, the astronauts would pilot Enterprise to a rendezvous with LDEF, snare it with the RMS, and secure it in the payload bay. Mass up would total 26,564 pounds; mass down, 26,369 pounds.

For Flight 18 (July 29-August 5, 1981), Columbia would carry to a 160-n-mi-high orbit a Spacelab pallet dedicated to materials processing in the vacuum and microgravity of space. The three-person flight might also include the first acknowledged Department of Defense (DOD) payload of the Space Shuttle Program, a U.S. Air Force pallet designated STP-P80-1. JSC called the payload 'Planned' rather than 'Firm' and noted somewhat cryptically that it was the Teal Ruby experiment 'accommodated from OFT [Orbital Flight Test].'

The presence of the Earth-directed Teal Ruby sensor payload would account for Flight 18's planned 57° orbital inclination, which would take it over most of Earth's densely populated areas. Payload mass up might total 32,548 pounds; mass down, 23,827 pounds.

Space Shuttle Flights 20 through 23 would include the first mission to make use of an OMS kit to increase its orbital altitude (Flight 21), the first European Space Agency-sponsored Spacelab mission (Flight 22), and the launch of the Jupiter Orbiter and Probe spacecraft (Flight 23)

Flight 19 (September 2-9, 1981) would see five Spacelab experiment pallets fill Columbia's payload bay. Five astronauts would operate the experiments, which would emphasize physics and astronomy. The Orbiter would circle Earth in a 216-n-mi-high orbit. Payload mass up would total 29,214 pounds; mass down, 27,522 pounds.

Flight 20 (September 30-October 6, 1981), the second Enterprise mission, would see five astronauts conduct life science and astronomy experiments in a 216-n-mi-high orbit using a Spacelab pressurized module and an unpressurized pallet. JSC planners acknowledged that the mission's down payload mass (34,248 pounds) might be 'excessive,' but noted that their estimate was 'based on preliminary payload data.' Mass up would total 37,065 pounds.

On Flight 21, scheduled for launch on October 14, 1981, Columbia would carry the first Orbital Maneuvering System (OMS) Kit at the aft end of its payload bay. The OMS Kit would carry enough supplemental propellants for the Orbiter's twin rear-mounted OMS engines to perform a velocity change of 500 feet per second. This would enable OV-102 to rendezvous with and retrieve the Solar Maximum Mission (SMM) satellite in a 300-n-mi-high orbit.

Three astronauts would fly the five-day mission, which would attain the highest orbital altitude of any flight in the STS Flight Assignment Baseline document. JSC planners noted that the Multi-mission Modular Spacecraft (MMS) support hardware meant to carry SMM back to Earth could also transport an MMS-type satellite into orbit. Payload mass up would total 37,145 pounds; mass down, 23,433 pounds.

On Flight 22 (November 25 - December 2, 1981), Enterprise might carry an ESA-sponsored Spacelab mission with a five-person crew, a pressurized lab module, and a pallet to a 155-to-177-n-mi orbit inclined at 57°. Payload mass up might total 34,031 pounds; mass down, 32,339 pounds.

During Flight 23 (January 5-6, 1982), the last described in the STS Flight Assignment Baseline document, three astronauts would deploy into a 150-to-160-n-mi-high orbit the Jupiter Orbiter and Probe (JOP) spacecraft on a stack of three IUSs. President Jimmy Carter had requested new-start funds for JOP in his Fiscal Year 1978 NASA budget, which had taken effect on October 1, 1977. Because JOP was so new when they prepared their document, JSC planners declined to estimate up/down payload masses.

Flight 23 formed an anchor point for the Shuttle schedule because JOP had a launch window dictated by the movements of the planets. If the automated explorer did not leave for Jupiter between January 2 and 12, 1982, it would mean a 13-month delay while Earth and Jupiter moved into position for another launch attempt.

Almost nothing in the October 1977 STS Flight Assignment Baseline document occurred as planned. It was not even updated quarterly; no update had been issued as of mid-November 1978, by which time the target launch dates for the first Space Shuttle orbital mission and the first operational Shuttle flight had slipped officially to September 28, 1979 and February 27, 1981, respectively.

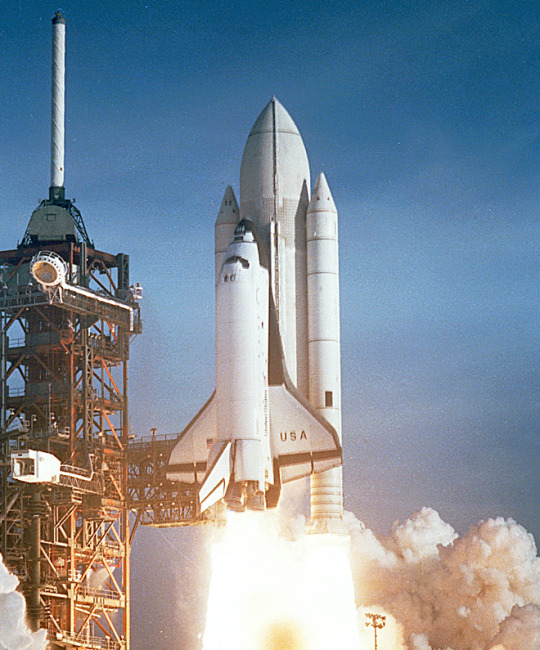

The Space Shuttle Orbiter Columbia lifts off at the start of STS-1.

The first Shuttle flight, designated STS-1, did not in fact lift off until April 12, 1981. As in the STS Flight Assignment Baseline document, OV-102 Columbia performed the OFT missions; OFT concluded, however, after only four flights. After the seven-day STS-4 mission (June 27 - July 4, 1982), President Ronald Reagan declared the Shuttle operational.

The first operational flight, also using Columbia, was STS-5 (November 11-16, 1982). The mission launched SBS-3 and Anik-C/3; because of Shuttle delays, the other SBS and Anik-C satellites planned for Shuttle launch had already reached space atop expendable rockets.

To the chagrin of many Star Trek fans, Enterprise never reached space. NASA decided that it would be less costly to convert Structural Test Article-099 into a flight-worthy Orbiter than to refit Enterprise for spaceflight after the ALT series. OV-099, christened Challenger, first reached space on mission STS-6 (April 4-9, 1983), which saw deployment of the first TDRS satellite.

NASA put OV-101 Enterprise to work in a variety of tests and rehearsals (such as the 'fit check' shown in the image above), but did not convert it into a spaceflight-worthy Orbiter.

The voluminous Spacelab pressurized module first reached orbit on board Columbia on mission STS-9 (November 28- December 8,1983). The 10-day Spacelab 1 mission included ESA researcher Ulf Merbold and NASA scientist-astronauts Owen Garriott and Robert Parker. Garriott, selected to be an astronaut in 1965, had flown for 59 days on board the Skylab space station in 1973. Parker had been selected in 1967, but STS-9 was his first spaceflight.

The 21,500-pound LDEF reached Earth orbit on board Challenger on STS-41C, the 11th Space Shuttle mission (April 6-13, 1984). During the same mission, astronauts captured, repaired, and released the SMM satellite, which had reached orbit on 14 February 1980 and malfunctioned in January 1981. Challenger reached SMM without an OMS kit; in fact, no OMS kit ever reached space.

STS Flight Assignment Baseline document assumed that 22 Shuttle flights (six OFT and 16 operational) would occur before January 1982. In fact, the 22nd Shuttle flight did not begin until October 1985, when Challenger carried eight astronauts and the West German Spacelab D1 into space (STS-61A, October 30 - November 6, 1985). Three months later (28 January 1986), Challenger was destroyed at the start of STS-51L, the Shuttle Program's 25th mission.

In addition to seven astronauts — NASA's first in-flight fatalities — Challenger took with it TDRS-B, NASA's second TDRS satellite. The Shuttle would not fly again until September 1988 (STS-26, September 29 - October 3, 1988). On that mission, OV-103 Discovery deployed TDRS-C. The TDRS system would not include the three satellites necessary for global coverage until TDRS-D reached orbit on board Discovery on mission STS-29 (13-18 March 1989).