#and that it relates to theories on the value of COMMODITIES which has little to NOTHING to do with what we're talking about in of itself

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Oh, I see. You and all your little friends are just too DUMB to understand. Too low IQ. The arguments sure is convincing.

I’m not kidding they really are saying somewhere out there that Kripke couldn’t possibly understand what it means to be blue collar because to do that, you’d have to have read about the value of a linen coat (which is not directly related to any of this btw) from Marx’s Das Kapital. Kripke of course couldn’t possibly have read it, and if you haven’t read it, you can’t possibly understand anything about class. You have to have read Theory™️ to understand what it means to be *looks down my nose at people who I assume Have Not Read All The Books That I Did* blue collar *sips from tea cup with my pinky out, chortling*

#and like. all of this misses that sam and dean exist in the context of their story/universe#and that they are very clearly and repeatedly treated as low class/working class by people around them in universe (especially dean)#Anyway the original thing being said was that maybe when people make extreme assumptions about dean...#it’s tied to their perception of him as low class in the context of his universe and/or ours#Saying people who (you assume) haven't read the theories you have are Too Stupid And Uneducated to understand#what it means to experience stereotyping based on class is a self callout lending to the original point being made...#AKA you like to make assumptions about people based on classist stereotyping. you told all of us that with your whole chest.hope this helps#Add that the value of a linen coat is an example in Das Kapital known to have been written in an overcomplicated manner#(even Marx himself acknowledged this)#that's especially hard for modern readers to grasp (also limiting it's use value—see what i did there—as a metaphor for a modern show)#and that it relates to theories on the value of COMMODITIES which has little to NOTHING to do with what we're talking about in of itself#and the pretentiousness of mentioning that in particular as a show of Kripke's alleged educational deficiencies just bleeds off every pore.#pony tail guy from the "how 'bout them apples” scene in Good Will Hunting demanding regurgitation of irrelevant info type behavior#“hee hee if you asked him about the value of a linen coat he'd shrivel” *chortles again in degree i think makes me superior*#real “he doesn't know about the three seashells” energy for some complete stranger. But like if you also didn't know#what the seashells were for and walked around with poop running down your legs all of the time#Like jesus fucking christ you people are insufferable.#mail

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

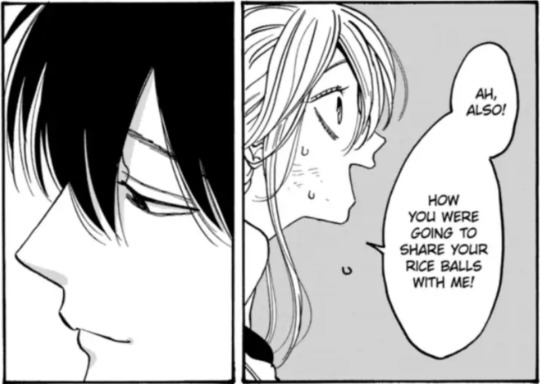

doing a concurrent reread in both english and japanese! i wanted to do some more character analysis this time around since i've read everything that's out, and i also wanted to look a little closer at the japanese (since i originally just read this in english). posting about chapters 1-5 here. (also interpretations of characters definitely aren't fixed yet, so i'm still figuring them out.)

"even so, out of my own will... i loved someone i should not have."

in japanese the verb that satoko uses for "loved" is 愛してしまいました. しまう as auxiliary to indicate that her having loved someone is something regretful, which at least to me i read as being in deference to the reader of her letter. i'm also curious about the usage of past tense here rather than using something like ている to indicate that she still loves this person. i've seen some theories floating around about her letter at the beginning here, but my personal theory that i subscribe to is that she's writing this on her deathbed, and the past tense is due to her likely death upon the letter being received. the only other scenario i can picture is one where shinpei was killed and she really did get his heart in the end.

lsjkdglkjlj the way that we see her already relating to things w shorter lifespans!!

also thinking about the way that shinpei is so casually chatty... why offer food to the person you're about to kill? it's like the planned act of killing satoko is separated from interacting with satoko at this moment. to me it really shows this... detachment? he's being kind by offering food, but he'll still kill her when the time comes. he's seemingly curious about why she's getting killed, but i don't think he has any attachment to her answer either way. it comes across as casually social while being incredibly detached from the person he's actually interacting with. it's probably an extension of his lack of empathy at this point. it just makes me wonder what motivates his interactions with others at this point.

god, satoko... the way that even being faced w sexual assault, her first thought is still on how it impacts her marriage prospects... it's awful the way that it's become her priority over all else in life.

thinking about what it does to a person to be raised on that island and how it impacts socialization. also the way that he sees his value as primarily being what he is able to do... how he is a tool and a weapon. i was talking a little about this on the hny discord where i think about shinpei and his lack of understanding of love as a concept, and how on the island love = sex = commodity = transaction, and how that has to influence his (lack of) understanding of it. his mother being a prostitute (and being killed when he was so young), too...

lsjkdgljsklgj i love that it's not enough to suggest marriage of convenience for access to what she has through her family, but she decides that she has to convince shinpei she's in love with him. which makes sense! if she's trying to cultivate a reason for him not to kill her! he's established that he'll be bought out with money, but he doesn't believe her declaration lksjgdlj so the assets somehow lose out to the promise of the marriage itself, which means there is something about a relationship he might actually want? at this time...

actually okay yeah the fact that money = priority up until she proposes and then he seems genuinely more interested in the concept of getting married to her and her interest in him than anything else. he ignores her comments about nobility in favour of asking what exactly she likes about him.

yeah god he seems like. genuinely into it when she's answering him desperately about things she likes about him.

i know satoko gets hurt by him later on when she realizes that he would be happy with anyone that accepts him for who he is (and i do think part of the reason he's interested here is because she's making these declarations after knowing what he does and seeing him maim people) but i do genuinely think that's part of his thought process right now. someone who accepts him... to me it's entirely about that and not about attraction. (until it is something he is attracted to, anyway, but i feel like that hasn't clicked for him at this point.)

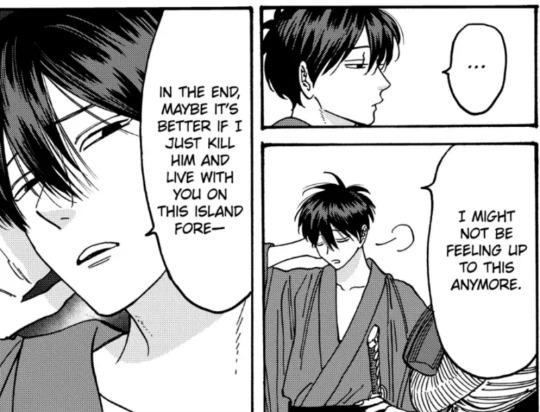

YEAH okay so the fact that he even clearly loses interest once he clarifies that it's a loveless marriage that she's proposing...

i do also think it's really interesting that after that, she asks him if there's anything else that's useful to him, but he's not interested in things that are useful to him! which....... man. to me it says a lot about the way that satoko thinks about her own value in that her connections are the only thing OF value (not satoko herself). i wonder how aware shinpei is of himself being a tool, too.

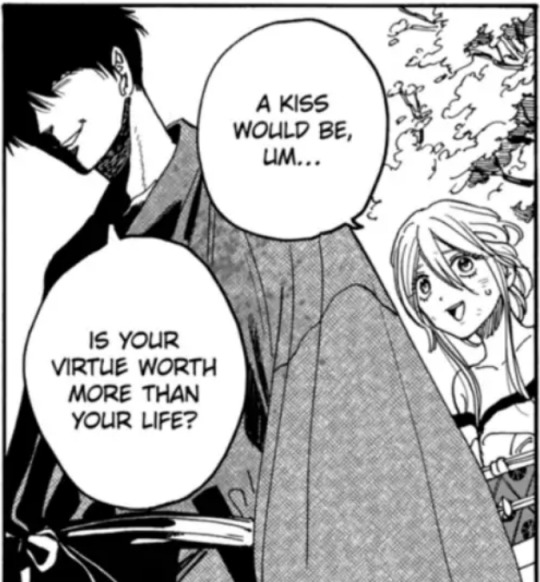

thinking about this line (when she's objecting to kissing shinpei initially) now in light of chapter 35... she really does keep having these boundaries of what she considers acceptable pushed. obviously kissing =/= sex here, and she just doesn't want to kiss him in this scene... but.

goddd thinking about the negotiation that's going on here. "it's fine if you don't want to." "and if i refuse?" "then i'll just kill you when i'm supposed to." all the really dubious consent that ends up happening particularly early on, especially because of the circumstances that satoko's trapped in... the situation with her autonomy is really fascinating to me. in so many ways she's had little-to-no control over her own life, starting already with her disability. then dedicating her life to repaying her father (and viewing it as her personal desire) rather than considering if she may have wants outside of that, because she can't act greedy. the way that she downplays her illness for others (and to give herself a little more freedom than she has), too. and then she gets into this situation. it's interesting in that there are strong limitations on any choices she makes right now, and while entering into this arrangement with shinpei could be seen as coercion when she's threatened with death otherwise, he also doesn't... force her? he isn't going out of his way to save her if she doesn't agree, but it is ultimately up to her, and these are all choices that satoko is making. even if her scope for making decisions right now is, again, incredibly limited under these circumstances.

it also reveals a lot about shinpei's wants that other than money, this is the only term he'll accept for saving her instead of completing his job. (and he quickly prizes the concept of marrying her and her feelings towards him over anything else that comes with that marriage, so money is definitely not the ultimate priority for him, anyway.)

god and the way he gets cruel to her when he thinks it's a lie. but how that just ends up bolstering her resolve when he mocks her, saying that she has no worries about the future...

the way we see light in his eyes for the first time when she wipes his mouth and he realizes she is not refusing him after all. aaaaaAAA

AND the way it's revealed he really was testing her!! that he's surprised she would still kiss him after he killed all those people!!

he's playful and childish, but he's also savvy, too... especially in these early chapters.

GOD the way he seems to like the mirroring of how both of them have uncertain lifespans and he isn't... too concerned w the idea that she'll die soon (bc she doesn't seem ill right now). the way that he even plays with it, thanking her illness, asking if she'll go to hell with him... commenting on her proximity to death and how that must be why she can be okay with him.

lkjsdglksjglkj god him mocking her when she starts saying "oh my dad might not agree to this". the way that he's just...... playing a game with her right now. toying with her. like this just seems fun to him.

"the kiss and the bath were the same. even though he knows i can't refuse, he keeps making me decide."

yeah like this!!! it's so interesting. it really does feel like a game when he's watching her responses here, knowing that she can't afford to say no, but forcing her make the choice nonetheless. "like he's confirming my affection for him." yeah. it's a test. a test and a game. he genuinely wants her to say yes, to play along, to keep confirming those affections—but it's a test every time to prove her affections to him. but it is what he wants from her, ultimately. that's his motivation. he has to keep Testing.

"please save me. you're the only one i can rely on."

thinking a lot about how this early phase of the relationship is entirely transactional and relies on what shinpei can do for satoko. and that it is entirely appealing to his strength and ability to protect her.

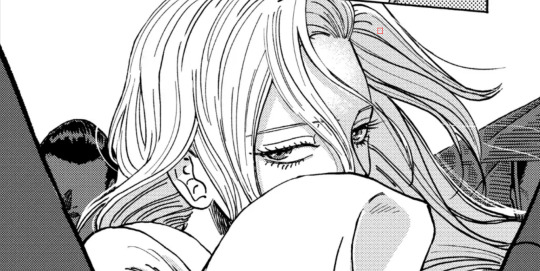

hmm and flipping it so now that she's decided his comment about how his life isn't enjoyable IS actually about him and not her. does he actually not enjoy his life? it's difficult to tell just because of how manipulative he's being in these early chapters, but. outwardly his life doesn't exactly seem great. part of what i'm missing about shinpei right now is an understanding of his inner life, and that's why i feel like i'm mostly grappling for an understanding of him rather than satoko. (although i feel like i'll definitely do another read-through where i do focus almost exclusively on satoko, because i adore her.)

god her comment about the heart is so interesting at this point and the gall of saying it to him.

and then ANOTHER test when he leaves w the prostitutes, making that comment about how it seems like he has to die after he gets out of here. so finally she gets her response to the comment about the heart... in the english translation she starts to say, "i never said you'd die!" but in the japanese she's just asking him to wait. so i feel like his reaction makes more sense in light of what was written originally—it's why he isn't placated.

it's also interesting that when he tests her and leaves her here, she does anything BUT continue to try and appeal to shinpei, instead trying to get attention from literally anyone else. which probably makes him feel useless, also! that she has the will to keep trying and planning and figuring things out without him! the way this backfires on him, particularly when she gets all this attention from people with her dance, and they start crowding her... so he has to drop it and relent. but like. i think he's genuinely captivated by the look she gives him in this scene and it makes him stop testing her (at this moment).

the way that it just feels like this look of, "i'll get by without you if i have to." but he doesn't want that.

"why did you go with them?" "i just wanted to stand and chat a bit." "lies. weren't you just enjoying my reaction?" in jpn -> comments on how he's enjoying her reaction AGAIN, acknowledging the previous tests out loud "you're right." so it's interesting he agrees to it.

her declaration of, "i'm fine if you're not the one who saves me"!!!! god i love the way she feels so independent here.

THE WAY HE ACKNOWLEDGES HIS FAULT FOR TESTING HER/PLAYING WITH HER!!!! like. i really do feel like the dance scene is where he pivots a bit. for her proving she can get by without him, and also (i think) for it making him actually attracted to her. i think he prob also appreciates her cunning about it? that she can play at this game, too.

like!!! satoko isn't just passively going along with things.

god the way that in jpn he doesn't say "forgive me" but "I WANT YOU TO FORGIVE ME" it feels so direct and impolite.

okay yeah i'm not just making this up because even satoko notices the change in demeanor where he isn't just blatantly messing with her anymore. he's decided he is actually attracted to her and doesn't want her going off with other men or relying on anyone but him.

i'm using "attracted" but i'm really only thinking about it in a physiological sense; i still don't think he has the capacity to understand his relationship with her beyond that at this point.

i also wonder if this scene just activated his jealousy a bit for the first time, too.

reading the (outdoor) firefly scene and thinking a lot about how they've both had constraints on their lives in different ways. shinpei unable to leave the island; satoko barely being able to leave the estate in general, and only when accompanied. i love how being here is, in some ways, a chance for her to experience so many things she was never able to before as nobility? (particularly disabled nobility.)

chewing on glass. the english line is "my body is yours to treat as roughly as you please" BUT THE JAPANESE LINE "consider my body as your tool. so it doesn't matter if you use it roughly." there was a game i was into years ago where the english kept removing the (very intentional) repetition of 道具/tool and i see that's happened here too lksjgdlj (i understand why! i know it's because in english it's more unnatural to repeat things all the time!) anyway i really like that he really does refer to his body as a tool. it's good. love that thematically.

godddd the part where she apologizes to him and it shows the way he was going to try and help her in the bath and also wanting to join her in her futon. he really does get obsessed with her after that dance scene, huh.

aaaAAAAAA i love shinpei talking about her being in constant danger would make him indispensable to her. like!!!!! the way he needs to be needed. he knows how to be a weapon and nothing else and he wants to be used (by her).

HE'S SUCH!!!! a sulky brat here. i love him. that way that he pulls this every time satoko starts being avoidant in any way about actually marrying him. i love her 100% not indulging him in this moment, though. it's so good. like!!! i just appreciate so much the way that she's still so strong-headed in her interactions with him. particularly despite how dangerous he can be, and the way that she knows she has to rely on him. she still feels, in many ways, so true to herself?? it's a really interesting dynamic, particularly with the way he's so manipulative, too. i love that she doesn't just submit to it. (and even when she does, she knows what she's doing.) it just!! makes her feel like she has more agency even if that's not necessarily true. and makes their dynamic really good to me.

okay trying to split this up by volume as i reread so these posts don't get too long. anyway. um. IF PEOPLE WANNA DISCUSS STUFF, PLEASE, i am so open to chatting about things

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Section VII: The Cost of Labor and Commodities

It is often stipulated by economists that an increase in productivity, or profit, or the cause of such by a decrease in the cost of expense, that all things which benefit the employer will trickle down and benefit the employee. In all of the evidence considered, it is solely competition among a group of buyers or sellers which determines the cost of items, as well as convincing the other party that they need such a commodity. Those Proletarian members whose labor consists in rather simple work tend to be paid a subsistence wage. This does not change whether their employers receive a great or small amount of wealth from their labor. If an employer, for instance, makes more profit, those who are working for him, especially those performing simple tasks, will not receive an increase in their wage. The reason for this is rather simple... The Capitalist has his own interest: his wealth. And, furthermore, he has the ability to reason: he reasons that by refusing to pay higher wages, he is benefiting his own interest of wealth. If a Capitalist, however, finds cheaper labor, or a cheaper method of production, still creating the same product or service as before, the product will not necessarily be cheaper. It must be understood that, as the production expenses decrease, product prices remain virtually unchanged.

A businessman, for instance, who owns a factory producing clothing, may discover an ingenious method in which he can produce two shirts for what once cost him for one shirt. He has no need to pay his workers more, as they are working for a subsistence wage. The only need he has, though, for decreasing the cost of his product, is in competition to others. He may, for instance, decrease the cost by 10% (even though production was increased by 100%). The decrease of the cost, however, will very rarely be equal to the new cheapness of production. The benefit of technology does not improve the lot of the laboring poor. It only improves the condition of the businessmen, by producing more for less. The only reason why there would be a decrease in the cost of commodities by one business is to compete with other businesses. Still, though, people would buy from other businesses. So, instead of decreasing the price, that additional wealth may go into advertising, or convincing consumers to buy this other product. The Capitalist may even use the technology as an advertising ploy. But, once the consumer purchases the products of this Capitalist, they have gained no real advantage, when compared with other products, since the additional productivity of capital has only rendered more wealth to the Capitalist, and not the consumer or the worker (and, it must be understood, that most of the time, the terms “consumer” and “worker” are dealing with different sides of the same person). The reason for a Capitalist to compete is simple: self interest. By decreasing the cost, this Capitalist may argue, he is selling more than before, thus making more profit, which is what he is rationally pursuing by decreasing cost.

There is ample evidence to support the theory that production cost is not the only determining factor of a commodity’s retail value. In his famous essay of 1778, Thomas Malthus wrote, “The increasing wealth of the nation has had little or no tendency to better the condition of the labouring poor.” [176] And, elsewhere, too, he writes, “...the increase of wealth of late years has had no tendency to increase the happiness of the labouring poor.” [177] Describing the fluctuations of an economy, and its relation to the cost of goods (and, therefore, to the cost of living)...

The country would be evidently advancing in wealth, the exchangeable value of the annual produce of its land and labour would be annually augmented, yet the real funds for the maintenance of labour would be stationary, or even declining, and, consequently, the increasing wealth of the nation would rather tend to depress than to raise the condition of the poor. With regard to the command over the necessaries and comforts of life, they would be in the same or rather worse state than before; and a great part of them would have exchanged the healthy labours of agriculture for the unhealthy occupations of manufacturing industry. [178]

What is it that precisely determines the retail cost of a good? In essence, there are two rules: first, the retail cost must cover the cost of production, otherwise the business will fail to make a profit and go under; and second, the retail cost will go as high as the consumers are willing to pay for it. This can be seen in our everyday lives, where the cost of things dramatically rises before holidays, such as Christmas, Halloween, or other assorted special days of the year. Prior to the holiday, the price soars, but once the holiday is over, the commodities assorted with that holiday decrease in price.

#class consciousness#capitalism#class#class struggle#communism#civilization#money#classism#anti capitalism#anti classism#consumption#economics#industrial society#poverty#workers#labor#anarchism#anarchy#anarchist society#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#resistance#autonomy#revolution#anti capitalist#late stage capitalism#daily posts#libraries#leftism#social issues

1 note

·

View note

Text

Capital Vol 1 Sec 1- Karl Marx

So this is a work I started years ago, but found too boring to get through even a chapter of. Since I've been rereading what I'm calling the "Commie Classics", and Capital is Marx's most thorough work, I'm almost compelled to attempt it again. That said, the work is almost 3000 pages over 3 volumes. You'll find little in it to tell you what Marx wanted to implement with Marxism. This work is an in-depth critique of capitalism as a system, and to be honest, I'm not sure I'll even bother to wade into volumes 2 and 3 since it's pretty clear by this point that Marx, for as much as he was convinced his theories couldn't be wrong, was actually wrong. Nonetheless, anyone seeking to understand Marx ought to be familiar with this work, so... in we go!

I'm divvying this work up into sections, of which there are 8 in the first volume. I'm more or less posting my notes on the work. My methodology was to read, underline what I saw as the important points, and then watch some videos about the work to see if I was getting what others were getting. Here is section 1, often thought to be the most difficult, but I didn't find it so. Perhaps because I've had enough of philosophy, and Marx, by now, to already have a base of understanding for the language. If this is your thing, well, hope you enjoy this.

Part One: Commodities and Money

Chapter 1: The Commodity

1. The Two Factors of the Commodity: Use Value and Value (Substance of Value, Magnitude of Value) 2. The Dual Character of Labor Embodied in Commodities 3. The Value-Form, or Exchange Value (a) The Simple, Isolated, or Accidental Form of Value (1) The two poles of the expression of value: the relative and equivalent forms (2) The relative form of value (i) the content of the relative form (ii) the quantitative determinacy of the relative form of value (iii) the equivalent form (iv) the simple form of value considered as a whole (b) The Total or Expanded Form of Value (1) The expanded relative form of value (2) The particular equivalent form (3) Defects of the total or expanded form of value (c) The General Form of Value (1) The changed character of the form of value (2) the development of relative and equivalent forms of value: their interdependence (3) The transition from the general form of value to the money form (d) The Money Form 4. The Fetishism of the Commodity and Its Secret

Ch 1: The Commodity, version TL;DR A commodity is something that satisfies some human need. Commodities have two types of value. The first is value as a useful item, and the second is value as something you can trade for another commodity. The thing that makes commodities valuable is how much human labor goes into them.

____

In a barter society, individuals would trade commodities, but in a more advanced society, money is more useful. Money is a commodity, but it has little useful value in itself, it's real value is as a medium of exchange.

The wealth of capitalist societies consists in the collection of commodities.

A commodity is an external object that satisfies human needs of whatever kind: corn, iron, phones, etc.

The usefulness of a thing gives it a use-value. This value is only realized in use or consumption.

Exchange value appears as a quantitative relation in which one can exchange one commodity for another. Exchange value is relative and variable. Exchange value is also not inherent in a commodity. A commodity can find itself having no exchange value at all.

Use-values can differ in quality. Exchange values have only one measure: quantity.

When you have two commodities of different use: like 20 ears of corn and a pound of iron, that can be considered roughly equivalent in value, so that the producer of 20 ears of corn might trade them for one pound of iron, then there is some other measure of value that completes the equation, and that is labor.

Marx makes the observation that in our societies, even the labor has been reduced to an exchange value. But he wants us to remember use-value when we compute 'value' in general, because in that use-value is a fundamental connection to nature that is separate from exchange value.

Marx introduces the idea of the amount of labor as the thing that can be measured to help define the value of a product. How much, and what kind of, human labor goes into making a thing useful? That quantity is called labor time.

A thing can be of use value, without being a value, because its utility to man doesn't require labor: air, virgin soil, natural meadows.

A thing can also be useful, and a product of human labor, and not be a commodity: something created by someone for his own need, creates use value, but not a commodity.

In order for a thing to be a commodity, it must have use-value, and be transferable.

Use value is the combination of two elements- materials and labor.

The value of commodities represents human labor. They have a dual nature: objects of utility and bearers of value. They have no objective value- their value is purely social, in relation to other things.

Useful labor is productive activity of a definite kind and exercised with a definite aim. It is the difference in this qualitative labor that gives such disparate use values to various commodities. It's why, in Marx's example, a coat has more use-value than a roll of linen cloth.

Marx then traces the development of money as an exchange medium as opposed to barter.

The simple form of value is in the exchange value of the commodity.

The relative form of value is how much linen would equal a coat, or any other commodity. It is the barter value of one commodity to another.

But the equivalent form is, if I'm not mistaken, money- a medium that will be used for exchange. It could be any socially accepted norm, but money in Marx's day was typically gold. This has direct exchangeability with all other commodities in a society. Money, has no intrinsic relative value. It has value as a medium of exchange, but unlike another commodity in a barter, no one needs coins or bills, for a use value apart from its value as an exchange medium.

Fetishism of Money Marx here notes the "fetishism" of this commodity, money. Here fetishism means an object attributed with powers it doesn't have.

Wood can be transformed into a table by labor. As a table, it's a commodity, but it's still wood too, an object that can be touched. It has a value that is relative to other commodities. Marx sees its value as a commodity as labor giving it an enigmatic quality. This mainly consists of the fact that the commodity reflects the social characteristics of men's own labor. Products of labor become commodities. The value isn't realized until the buyers and sellers come together and the social characteristics of their labor manifest themselves.

The price of commodities becomes set through a wider participation in a market where values are more or less set through a mass of transactions.

Chapter 2: The Process of Exchange

Ch 2: The Process of Exchange, version TL;DR Money is useful as a commodity because it is easily divisible into whatever denomination is needed. Gold, silver and copper were traditionally the metals used for money. Money is the symbol of the amount of labor that went into producing the commodity.

____

Commodities can't exchange themselves, so they must be brought to market by their owners. The owners in turn relate to each other merely in terms of being owners of private property- their commodities. A commodity is distinct from its owner by the fact that all other commodities are nothing more than some measure of its own value.

For the owner of course, his commodity has no use-value to himself, or he'd just use it. Instead it is merely a bearer of exchange value. Since the value of the commodity comes down to the labor put into it, only in the act of exchange can its use-value for others be proven.

In a pure barter economy, every owner sees other commodities he is interested in measured by his own particular commodity. If he has corn, then anything he wants to buy will have to be considered in how many ears of corn it will take to procure the thing he wants. But every owner of every commodity thinks the same, so there is no actual universal equivalent.

The natural answer that arose was money, some agreed upon material of exchange. Marx notes that one of the unique characteristics of money is that it has no use-value on its own. If society were to decide some useful commodity- like corn... or cows- would be the medium of exchange, then that commodity would itself have use-value. But one of the attributes that makes money attractive as an exchange medium is that, because it has none, it is neutral in use-value.

Gold and silver have traditionally been used. These both have dual values, both use and exchange. But for exchange, the medium should be of a material that has uniform property, so that it can be divided at will, and also reassembled. Gold and silver possess these properties.

One can't divide a cow up if he wanted to buy something worth less than a full cow. And even granting that he could butcher the cow and exchange parts, some parts are going to be worth less than others, and cows certainly can't be reassembled. So gold and silver it is.

The fact that money became more of an exchange value than a use value led some to imagine that money had no innate value, but was merely a symbol. While this wasn't true, at least with gold and silver, it did "contain the suspicion that the money-form of the thing is external to itself, being simply the form of appearance of human relations behind it". For Marx, money becomes the direct incarnation of all human labor. Their relationships then form a material shape independent of their control and action. The products of men's labors are no longer considered in terms of the exchange of use-values, but in the form of commodities. This is the money fetish.

Chapter 3: Money, or the Circulation of Commodities

1. The Measure of Values 2. The Measure of Circulation (a) The Metamorphosis of Commodities (b) The Circulation of Money (c) Coin. The Symbol of Value 3. Money (a) Hoarding (b) Means of Payment (c) World Money

Ch 3: Money, or the Circulation of Commodities, version TL;DR Rather than barter with another individual, we now use money. First we sell our commodity: C, and get money, M, then we use money M to get the commodity, C, we want. This form of circulation is C-M-C.

____

But since money is a source of value in the market, the circulation can become inverted to M-C-M; where people have money, then use the money to buy a commodity, so they can sell it for more money. Marx calls this a 'metamorphosis' of the circulation.

In the measuring of values, Marx assumes gold is the money commodity. Its main function is to supply commodities with an expression of their value, represented as magnitudes of the same denomination, qualitatively and quantitatively comparable. It is in this way that it acts as a universal measure of value, and becomes money. Money is the necessary outcome of the need to express the measure of value of labor-time.

While commodities have an actual use-value too, their price, or exchange value is separate and distinct from this in that it is a purely ideal, or notional form. In other words, the price-value exists only as a notion or idea. Marx goes on that since this relation to money is only as an idea, it is expressed on the tongue to those outside the owner of the commodity. As such, computations of value are done purely as mental exercises, and do not require any amount of actual gold or money. But while the money 'that performs the function as a measure of value' is imaginary, the price depends on the actual substance that is money.

Marx notes that since copper, silver, and gold serve as money, commodities will have value expressions in all three. Changes in the values of these metals will affect the money values of the commodities. Each started off with a name denominating a certain weight.

So money performs two different functions as a measure of value: the first is a measure of value of the social incarnation of labor; second it is a standard of price of a quantity of metal. But the value of gold can and does change, which will require adjustments as to the prices of the commodities, whose values it represents. A rise in the prices of commodities can occur when their values increase, OR when the value of money decreases.

Marx notes various situations that could cause fluctuations in the prices of commodities. While price has to bear some relationship to the amount of labor, the fact is that conversion of value into money means that an incongruity between value and price can occur. Marx sees this not as a defect, but as adequate for a 'mode of production whose laws can only assert themselves as blindly operating averages between constant irregularities'.

He also notes that the price form can also harbor a contradiction: price can cease to express value altogether, even though it is nothing but the value form of commodities. Things that are not commodities at all: honor, conscience, etc, can be offered for sale by their holders and thus acquire the form of commodities through price.

To establish a price, it is sufficient to equate the commodity with a measure of gold, or money. But to actually buy it, will require the actual amount of gold. The price-form implies both the exchangeability of commodities, and the necessity of exchanges.

In the Measure of Circulation, Marx first looks at what he calls the metamorphosis of commodities. It's essentially expressed in a very simple formula: C-M-C ; meaning first a thing is a commodity, then it is exchanged for money, and then back to a commodity. He uses the example of a linen weaver who takes his 20 yards of linen to the market. The 20 yards of linen is a commodity. He sells that for £2, which he then takes a purchases a family bible for the purposes of edification. Marx makes much of the fact that the product of the weaver's labor, the linen, is not of use value to the weaver, and it acquires no 'social validity' until it is exchanged for the £2. If he can't find a buyer for his product, then his labor effectively has no useful social value. If too many weavers are spending too much time weaving too much linen, then the market is glutted and sellers will start to sell for less in order to get what they can, and the price drops. There are myriad factors that affect the value of commodities and the sum of them will affect the first part of the conversion of a commodity to money.

M-C, or money to purchase a commodity is the second part of the metamorphosis. Marx says money is the absolute alienation of commodities, because it has no use-value, just exchange value. In the metamorphosis, every commodity disappears when it is transformed into money. No trace remains of the reason for the labor originally done- to produce some socially useful object.

Marx also notes the obvious, that C-M, a sale for the seller, and at the same time, a M-C, or a purchase for the buyer. This is where the 'contradiction' is resolved.

The circulation of commodities is distinct from a direct exchange. The seller of linen, bought a bible. But the bible seller didn't purchase linen. He preferred to purchase something else. In this way, the market becomes a whole network of social connections beyond the control of human agents.

The circulation of money is the continuous, repetitive process of commodities being sold for money, and that money used to buy another commodity. Marx notes that the flow of money from buyer to seller is the hidden one-sided flow of the two-sided C-M-C metamorphosis mentioned earlier. Money removes commodities from circulation, by constantly stepping into their place.

Marx notes that commodities come into the market, and then go out, to be replaced constantly by new commodities. But money continues circulating. The amount of money needed for this must equal the amount of commodities being exchanged. Changes in the size of the economy will then require more or less money in circulation.

Money takes the shape of coin because of its function as the circulating medium. Gold, silver, and copper can be measured and minted according to specific sizes corresponding to the values set by the governments where issued. Paper money also came into existence as symbolic of the actual precious metal coins. In theory, the amount of paper money put into circulation needed to be backed by actual gold. If the amount of paper money exceeds that gold, then it is devalued accordingly.

Marx then notes that the only reason paper money can be issued as a symbol of money, is because money itself had become only a symbol of value. That said, the money must have objective social validity. In other words, the people doing commerce with it have to believe it is a symbol of value.

Money carries its own problems. For one, people may decide not to follow through with the second part of the CMC equation and just hold on to the money in order to stockpile it, rather than use it to purchase more commodities. This happens because the accumulation of wealth is seen as socially desirable. Having value stored in use-value commodities is one thing, but have value stored in money means it can be exchanged for anything. So money becomes the most valuable commodity to stockpile.

Marx covers various means of payments that aren't the usual immediate transactions, such as deferred payments, speculations, and credit and debts. He notes that in the Roman empire, there was an ongoing clash between creditors and debtors, with many debtors ending up as slaves. He discusses agreements where goods change hands with the promise to pay later. But circumstances can arise, in a fully developed economy of promises, that cause deficits between debtors and creditors, with the effect that money is sought after, even more than hard, use-value commodities.

Marx also notes that credit notes themselves can be sold as measures of wealth. Meaning one collector can sell debts he is owed to another collector. By this point, money as a means of payment has spread beyond the sphere of circulation of commodities. Rent, taxes, and so on are all collected in money.

As money leaves the domestic sphere and travels to other countries, it must be converted back to its precious metal form. World money serves as the universal means of payment, of purchase, and of absolute material wealth. Every country needs a reserve of gold for internal circulation, so it needs a reserve for circulation on the world market.

0 notes

Text

an assignment i must cope with

“The three readings this week agreed upon one simple idea: nearly everyone is capable of labor. Smith emphasizes the consistency of labor in which a participating member of society must contribute to the market, so as to embrace collectivism. A virtuous cycle begins. Marx shares a similar sentiment in that capital is limitless. There always exists a buyer and a seller, and I interpreted his critique as a comment on human limitations in their labor-power. Instead of naturalizing the idea of the market, he attributes it to a historical development in which commodities have gone through years of mistaken theory, according to Marx. Smith embraces individuals working together to build security in society while Marx critiques the means of production as an animalistic chase of money, which then relates to Weber’s essay on the protestants. They believe in sin, greed and money going hand in hand, but ultimately bending to the market. A question that I sat on while flipping through the readings stems from my ignorance of the philosophies in human motivation. If capital is limitless, not securely finite, how does one view equality when indulging in individualism? Rather than villainizing and attempting to stomp out the market, a focus on the individual in their natural instinct towards self-interest ensures a working market, but then exists those who fail to produce thus the struggle and crisis of capitalism begins. Are human limitations to be ignored?”

If you completely read my ramblings, you would understand that I know nothing at all. Purely auto-biographical and generic, but I can read across as ‘GOD CAN SHE SHUT UP!? She’s actually the worst, but she claims to be the best because she values THE SOCIAL LADDER.’ Whatever that means.

There are at least ten thousand hotter, more talented, greedier, more nihilistic, edgier, more profound ‘sad girls’ out there. I promise you, you are not the hot shit you so deluded yourself into thinking you are.

Because I look at you and see nothing but a pathetic attempt at redemption. So go on! Ignore my hand and seek out a bonier, more inviting hand as you see mine shake. Your outfit makes me cringe. My friends are cooler than you. We would spit on you if we saw you at Trans-Pecos. You would stick out like a sore thumb.

Perhaps I’m being too mean… But I realize that I’m not because I’ve met bitchier, more sinister little bitches. Except, I respected them as they wore cuter clothes than your long leather jacket. You must feel so NYC with that on. I don’t think I’m a bitch at all. Sure, I slink around the grimy gutters with a Marlboro Light, call myself a “Club Kid,” and stick around the DJs, but I am not at the same level of those bitchier, more sinister little bitches who wore cuter clothes. I am a step below, the writer who observes it all, and tucks it away for a later date. Like right now! As I type out this assignment I must cope with…

There is a greedy chase in this so-called ‘social ladder.’ It does not exist, yet everyone in the room realizes one thing when they talk to some Bushwick-ian looking freak, “What can they do for me?” When you enter some Dimes Square rooftop poetry reading, you sit back and wonder, “Did they get canceled? Does that make them more interesting?”

I have no clue at all what you can take away from this pathetic attempt at social commentary… Creative writing has been my ‘thing’ for awhile. Please don’t take that away from me… Just look at me and acknowledge that I’m fucking cooler than you. I am the micro-influencer you so desperately try to cling to.

This is creative writing and I did not mean a single thing I said, but I will post it anyway because I think you can laugh and roll your eyes with me.

Tell everyone about the horrible NYC take you read. Tell everyone about how I wrote a substack article on you! I am probably talking about you. Tell everyone about how delusional I am for even thinking this was okay! Afterall, I have no grasp on the human limitations on shittalking…

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sustainable Development Goals:

GOAL 13 AND GOAL 12

WHAT IS CLIMATE ACTION (Goal 13) ?

Climate action means stepped-up efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-induced impacts, including: climate-related hazards in all countries; integrating climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning; and improving education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity with respect to climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning.

COVID 19 AND IT'S IMPACT ON CLIMATE ACTION (Goal 13)

As the world is struggling with the rapid-onset COVID-19 crisis, and while it is early to conclude which response strategies were the most successful, we can already start drawing some lessons to help shape our response to the slow-onset disaster of climate change. We share here seven such lessons on how to ensure that the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis will happen in a way that will still put the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement at the center of sustainable development efforts.

1. Put science and scientists first

From the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists came together to form collaborative networks beyond political lines and national borders, which has increased the efficiency and speed in research to find a cure. Similarly, policy for advancing climate action should follow science, rather than having political differences interfering with, and preventing, scientific research to be carried out. While the global response to the climate emergency is, and should continue to be, part of multilateral negotiations, science is not negotiable. Well informed climate negotiations mean unimpeded transparency and scientific cooperation, such as the one provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

2. Adopt a “whatever money it takes” approach

Investments that can save even one life, improve livelihoods and the health of ecosystems are never too much. Governments have quickly mobilized financial support to back businesses and expand welfare benefits in response to the COVID-19 pandemic; and this is the right thing to be done! But we often see that much-needed investments on climate action fall victim to difficult negotiations and political conflicts. An urgent fund mobilization is needed to avoid a climate catastrophe. Research shows that the climate investments needed also make great economic sense. For example, it is estimated that for every dollar invested in climate resilient infrastructure six dollars are saved.

3. Protect and improve common goods.

Over-exploitation of common goods, without consideration for the long-term needs of our next generations, has resulted in the “tragedy of the commons”, with big environmental impacts, including the zoonotic origins of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cases of response to the current pandemic show that previous investments by countries in public health and welfare systems have produced better results. Equally important are investments to restore clean air and water, healthy ecosystems, and other environment and climate goods, which contribute to planetary health.

4. Focus on those already left behind

The COVID-19 pandemic struck fast and affected those most vulnerable, those who had little means and access to health-care services, and those in nursing homes and homes for persons with disabilities. In the case of climate change, the ones that have been left behind include inter alia poor farmers, people who lack access to basic services, people living in slums as well as climate migrants. Climate mitigation and adaptation activities should put these and other vulnerable groups at the center of attention and response.

5. Make the global value chains climate resilient

The COVID-19 driven disruption in sectors like transport, medicine and tourism was immediate and hard. The climate crisis with its low on-set characteristics will drive at least similar if not larger implications in the value chains of main sectors. But it will likely do this over a longer time. There is an opportunity to develop systems able to increase the resilience of value chains in climate sensitive sectors; and ensure that critical commodities and services are available to all at times of climate-induced disasters. This will also impact the supply of funds and finances, which need to be directed to deal with critical situations, rather than bailing out polluting industries in decline, creating quick stimulus for sustainable and low-carbon commodities and common goods services.

6. Fix and make sustainable the food systems

The FAO has started documenting the negative impacts of COVID-19 on food security. The impacts of climate change on agriculture have also been extensively documented by the IPCC and it is evident that the most crucial global value chain that must be secured against the climate emergency is the food supply chain. Making agriculture and food systems more sustainable is not science fiction. Many policy options have been proposed and already implemented including inter alia ecological rotation of crops, robust estimation of the true cost of food, reducing food waste, fair trade, drastically reducing pesticides, decarbonizing food production and distribution systems.

7. Ensure credible information and not fake news leads the public discussion

Since the causes and risks of climate change are already well examined, documented and vetted, scientific facts and solutions need to be brought widely to the attention of the public to avoid speculations and misconstrued theories, which only cause anxiety and panic, as is happening around this novel disease. The science is unequivocal, and the advocacy should be as large as ever to make every climate denier become a climate champion.

The climate crisis may be seen as a slower moving crisis than the speed of this global pandemic, but it’s the long-term effects are likely to be far more threatening. Runaway global warming is something we do not have the science, technology or funding to solve. Without additional commitments to decarbonization, the planet is on track for a 3.2 degree global temperature rise and beyond. This is linked to an increased likelihood of pandemics, extreme weather events, droughts, flooding and widespread destabilization of global food, economic and security systems. Unchecked global warming will undo gains to address almost every sustainable development goal. It will undo economic recovery.

Today, however, global warming can be limited. As plans are formulated to help countries and communities rebuild their economies and societies, this is an opportunity to embrace renewable energy, green technology and sustainable new sectors that put the planet on a fast-track path to decarbonization.

UNEP is supporting national, regional and sub-regional policymakers and investors and to green fiscal stimulus packages and financing. UNEP is helping to prioritize “green and decent” jobs and income, investments in public wealth and social and ecological infrastructure, advance decarbonized consumption and production and drive forward responsible finance for climate stability.

The work focuses on sectors critical to building back a strong economy: energy transition, buildings and construction, food systems, waste, and mobility, enabling the world to establish the next generation of sustainable and productive infrastructure.

It includes efforts to make trade more climate resilient and sustainable and build on lessons learned from the policies of the Global Green New Deal. UNEP is also continuing to support ongoing country actions on climate change, repurposing energy, cooling, nature-based solutions and recovery investments to align with the Paris Agreement, in collaboration with UNDP and other partners to ensure recovery plans reduce future risks from climate and nature breakdown.

UNEP is committed to supporting member states to identify and facilitate these opportunities and to support successful outcomes at the next Climate Change Conference (COP26) taking place in 2021, and the broader 2030 agenda.

RESPONSIBLE CONSUMPTION AND PRODUCTION (Goal 12)

WHAT IS IT?

As defined by the Oslo Symposium in 1994, sustainable consumption and production (SCP) is about "the use of services and related products, which respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life while minimizing the use of natural resources and toxic materials as well as the emissions of waste and pollutants . This goal is meant to ensure good use of resources, improving energy efficiency, sustainable infrastructure, and providing access to basic services , green and decent jobs and ensuring a better quality of life for all.

IMPACT DURING COVID-19

Unsustainable production and consumption is perpetuated by brown financing, investments and lifestyle choices. Such practices have led to a depletion of natural resources, disruption of ecosystems, resource and carbon-intensive economies and infrastructures, as well as environmental health issues and diseases.

This pandemic has shown where many of the weaknesses in our systems lie. It has proved that responsibilities to act extend from governments to private sector to civil society and individuals if we are to successfully meet environmental goals. Closed borders, availability of commodities, and confinement have forced behaviour changes worldwide.

Some of the changes have accelerated new and emerging sectors that support responsible consumption, such as online working or locally sourced production. As people return to work and schools reopen, some of these positive changes can be retained. Employers – public and private – and individuals have now tested alternative ways of working, studying and consuming at a scale that can durably leap-frog some transitions to more responsible consumption and production.

UNEP is working with partners for recovery policies and investments to incentivize circularity, an inclusive sustainable consumption driven approach and the aligning of public and private finance with shifts towards more sustainable and resilient economies and societies. This is a real opportunity to meet that demand with stimulus packages that include renewable energy, smart buildings and cities, green and public transport, sustainable food and agriculture systems, and lifestyle choices.

Taking action today to protect ecosystems on land and in water, combating global heating and including “safety first” biosecurity measures and environmental safeguards is critical. Ensuring that the knowledge and commitment to responsible consumption and production extends across all pillars of societies will be fundamental building blocks to future-proof the progress and success of all other sustainable development goals.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Little Response to Rhavewellyarnbag's latest Review of The Terror's "Horrible from Supper" (the italics are me)

Being another look at The Terror, episode 01x07, “Horrible From Supper”. But first, the characters in The Terror to whom I own an apology for the things I said last night when I was drunk, in ascending order of how vile it was: Francis. Yes, what I said was true, but I should not have said it. Goodsir, on general principle, because he is a nice man, and doesn’t deserve to have the likes of me talking about him that way. Author’s note: Only daily do I apologize to Harry Goodsir (fictional) for the things I say about him, and to Harry Goodsir (nonfictional) for the things I say about a fictionalized version of him. I like to think that the former would forgive me, but I think that the latter might not. I painted him from the few photos made of him; he has a delightfully reproachful look. Resting bitch face, even.

In the 1845 photos, his eyebrows come together in a way which could be interpreted as judgmental. But, when we think of the trials of sitting for a daguerreotype at that time (not nearly as jolly and pain-free as depicted in “The Ladder” –forgetting about the subsequent Tuunbaq attack) Goodsir’s reproachful look might merely result from the tedium of having his picture taken (or that fatal tooth was beginning to hurt). Tozer. Though, again, I meant it, and, like, look, I defy you tell me that he doesn’t look absolutely stunning when he’s afraid for his life in “Terror Camp Clear”.

“The Terror” certainly broadens the parameters of handsome-ness. Tozer, while listening to Morfin singing “The Silver Swan”, is more attractive than, than, than the Moon! Or the Pyramids! He’s supernatural.

The ship before it weighs anchor, before it, in some fundamental way, becomes a ship. Not yet having fulfilled its function, it is more like a theatrical set. The notion of limbo is a fitting one: the men descending the ladder, coming from the bright, noisy world above, could be entering the afterlife.

Who’s the cat who does the words about utter existentialism? Rod Serling, was that his name? Did everyone see his episode of “The Twilight Zone” about the toys in the Salvation Army barrel? Yikes.

Nothing is working as it should, logic is suspended, and the topsy-turvy world of the carnival will become real.

The movie “Topsy-Turvy” is a great favorite of la famille Sunbeam. Even so, there are useful parallels between that film and “The Terror”: class clashes, pretense and pageantry, and mainly ripping away the fine lace mask of the Victorian era. The attitude of the servants in both shows is strikingly craven.

“Any tips, sir, for a first-timer?”

In the super-heated world of fandom, “any tips for a first-timer” sounds like the sort of pick-up line EC would use on the true Cornelius.

Poor Morfin.

Morfin is “The Terror’s” equivalent of the Victorian Little Nell. Headaches, bad teeth, song-forgetter, probably a once-in-a-lifetime sodomite but nevertheless flogged for it. When he and Tozer go out on that exploratory mission, he falls flat down and Tozer says something like “Don’t volunteer if you don’t have the bottom for it.” (More heat for the fandom). And he gets to be the first to see the severed heads. (Who thought Tozer and Morfin would make a good team for this task? Did they draw names?) “Gently with that one, please.” It’s a little bit insensitive of Goodsir to express concern for his luggage before he does, Morfin, after Morfin’s just collapsed from pain, only looking like the living dead. That trunk, though, is Jacko’s tomb.

Harvey, your theory about Goodsir’s, ah, class-related selfishness is confirmed here.

“Are these our choices, Cornelius, or are they being made for us?” Gibson seems to falter, which is interesting. His idea to separate from the larger group doesn’t seem to be his own, which suggests that Hickey understood that it couldn’t be seen to have come from him. Gibson looks like death warmed over, but Hickey is just as perky as ever.

Gibson seems to get on-and-off injections of great intelligence, but his death-warmed-over look is consistent through the series.

Hickey is also under-dressed, not even wearing a hat.

This is perhaps a very English-major thing to say, but there is a suggestion of a climate change (or a massive change in consciousness) occurring after Carnivale, as if the trauma of the fire left living dead who can no longer feel the cold, or, having felt so much fire, the survivors have had the idea of cold burnt out of them.

He does sometimes dress more appropriately, as in “A Mercy” when he was helping Hartnell transport supplies for the carnival. Suggesting that, in this scene, Hickey means to maximize his attractions. The obvious beneficiary is Gibson, but I think Hickey sees some value in displaying himself for Tozer, the one Hickey is really after, and has been since at least “Punished As A Boy”.

A sexy thought; how much nudity the men would crave. When Hickey is flogged, he is completely exposed to the men present, and I think the sexuality of his having his pants pulled down really hits the sailors hard. Francis alone looks like he’s going to climb out of his skin with the ferocity of his feelings (I won’t say desire, but that’s what I mean). Was it you, Harvey, or someone else who discussed how strong the thirst for touch must be among the Franklin Expedition? I imagine the thirst to see bodies is just as powerful.

Then, I was immediately resurrected by the peek at Collins’ suspenders. He is... built like a cement outdoor commode. There is a lot of Collins to love.

The suspenders become iconic. Collins is one very alluring sailor, even in his bulky sea-diving outfit with that great furry head sticking out. Yet his sexuality seems neutered, compared to the other significant sailors (Still, if Hollywood decided to make a chubby “Wuthering Heights”, Collins would make the perfect pudgy Heathcliff.) Author’s note: I don’t think Francis thinks very much of Goodsir, and the feeling is mutual. Goodsir has to obey Francis, but it’s duty without devotion, without deference, Goodsir having seen very little that would indicate to him that Francis has reformed himself. Francis may have stopped drinking, but he’s up to his old tricks, dismissive unless he wants something, ingratiating when he does. This is the way that Francis behaved toward Hickey, which gives an interesting contrast between Goodsir and Hickey: once Goodsir understands Francis’ motives, he’s no longer taken in; Hickey must understand that Francis was only drunk and trying to get into Hickey’s pants, but Hickey continues to try to make Francis like him.

Francis might resent Goodsir’s place in society, so settled and unique, while Francis himself has to maneuver around Sir John and James and all the rest. But Hickey he can control. (In a way, it’s a shame that Irving, the stupid old king of coitus interruptus, has to bust in again. It would be in vain, and yet interesting, to consider what might have happened if that seduction had been consummated. Think of the bickering harem Crozier could assemble: Hickey and Jopson and Gibson and then Irving, etc etc. (But this speculation, that a captain would handpick a seraglio of sailors, is ruined by the knowledge that, despite all the porn stories and movies, there is no one a teacher would want less to seduce than her students.)

James has to move his little pick ax from one hand to the other to reach out to Francis, suggesting that, emotion aside, he made a conscious decision (his bones not yet reduced to broken glass) to grab Francis’ jacket, right over his heart, no less, and jostle Francis in a friendly manner.

This moment is comparable, to those who might be interested, to Star Trek: The Original Series’s “Amok Time” when Spock grabs Kirk by the arms. Quite the pensee could be written comparing Kirk-Crozier (the fair-haired captains) and Spock-Fitzjames, the haughty eyebrow-waggling second. The latter’s reserve is melted, melted utterly by his realization of how much he loves his Captain.

Author’s note: I am into Edward, but conditionally: I like him in that coat that makes him look substantial. Matthew McNulty is lovely, but he’s far thinner than I thought he was, which came as a bit of a shock.

His shortness is also quite astonishing. I can’t imagine Levesconte being involved.

Levesconte is too busy lying on his little officer’s cot, reminiscing about the time he said “benjo” and everybody cheered.

“There was a fourth man.”

I know you are referring to the raid on Silna in “Punished as a Boy”, but these words put one in mind of T.S. Eliot’s notes to the “Fire Sermon” in his “Wasteland”: “it was related that the party of [Anarctic] explorers, at the extremity of their strength, had the constant delusion that there was one more member than could actually be counted”. Ah, the hypnotic potency of the top of the world.

Did Edward just grab Irving’s knee? Judging by Irving’s expression, yes, I think he did. I think he leaves his hand there for the rest of the meeting. Actually, no, he does not, but he appears to again bring it down to the general vicinity of Irving’s lower body.

I have run this scene over again and again and again (like the Zapruder film), and I think Edward does make an aggressively intimate gesture: “left and to the back, left and to the back.” Irving does not seem displeased.

Hickey begins to assume what he imagines as Tuunbaq’s character. Having already, it’s implied, eaten part of Heather’s brain . . .

It is more probable that Hickey was just tapping at Heather’s brain, mainly because a brain IS not like a pudding; a pudding can be nibbled on without anyone noticing. But if someone nicks a part of a cathedral, which is a self-contained entity, it would be noticed by, at least, Nurse Tozer. Still Hickey might have tasted the cerebrospinal fluid, just for the Hickey of it.

When first aboard Terror, Hickey appears to be sizing up his new environment, but he also looks relieved, hopeful. It’s implied that he had a lucky escape from England, which had gotten too hot for him, but I think that he really believed that he was making a fresh start. Taking another man’s name was practical, perhaps a necessary evil, but I think that E.C. just didn’t want to be E.C. anymore.

I admire the symmetry of Hickey throwing a Neptune-sized bag down by Hodgson, thus startling him far more than one think a tough lieutenant would be startled.

Author’s note: . . Silna doesn’t fall into Goodsir’s arms, because there’s no reason why she would; she might like him, but he’s merely the least untrustworthy of a group of untrustworthy men who, by the end of the series, have not just made her home almost uninhabitable, but killed her father and her friends. Her discovery of Goodsir's body, the state it’s left in, confirms it: if this is what the British do to each other, she was lucky to get away when she did.

Hear hear!

By the way, if one is in the mood, another pensee could also be written about the real daguerreotypes of the Franklin expedition. I am particularly amused by Gore and Fairholme. Gore hates Lady Jane and this stupid thing she’s making him do. just so Sir John can be further exalted. Fairholme picks up the vibe and poses just like Gore, only he has to borrow the affable Fitzjames’ jacket.

I think we’ve all been there.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“It has long been recognized that the foragers of South India – such as the Kadar, Paliyan, Malaipantaram, and Jenu Kurubu – express what has been described as an individualistic ethic or culture. […] But to understand what this individualism entails, an initial note of clarification seems essential. For there has been a lamentable tendency on the part of many anthropologists to set up, in rather exotic fashion, a radical dichotomy between Western conceptions of the individual – misleadingly identified with Cartesian metaphysics or the “commodity” metaphor – and that of other cultures. […] The Malaipantaram, and other foragers of South India, like people everywhere […] recognise that the people they encounter are human beings (manushyan), as distinct from elephants and monitor lizards, and that they have unique personalities, and a sense of their own individuality (which ought not to be equated with individualism as a cultural ethos). They recognise too that other humans, both within their own society and with regard to outsiders, are social beings with ethnic affiliations and diverse social identities. But what is significant about the Malaipantaram and other South Indian foragers’ conception of the human subject is that they place […] a fundamental focus on the individual as an independent person. A fundamental value and stress is put on the autonomy of the individual. Both in terms of their child-rearing practices and their gathering economy, the Malaipantaram place a high degree of emphasis on the person as an existential being – as self-reliant and autonomous. […]

Nobody has expressed this individualistic ethos with more cogency than Peter Gardner, who in relation to the Paliyan and several other foragers views it as intrinsically linked to individual decision-making, social mechanisms that undermine any form of hierarchy, a nonviolent ethos, and a general absence in the formalisation of culture. […] But the key distinction that has to be made is that between the individualism of the South Indian foragers and the various kinds of individualism that are generally associated with the capitalist economy. These range from that of Cartesian philosophy, with its notion of a disembodied ego radically separate from nature and social life; the abstract or possessive individualism of liberal theory that was long ago lampooned by Marx and Bakunin; the methodological individualism of optimal foraging theory (critiqued by Ingold, 1996); and the radical “egoism” of Ayn Rand which advocates a form of selfishness that has little or no regard for other humans. […] [In contrast,] [a]n egalitarian ideal permeated Malaipantaram society, and this ethos contrasted markedly from the emphasis on hierarchy in surrounding agricultural communities, particularly in relation to gender and with regard to the higher castes. […] Among the Malaipantaram and South Indian foragers egalitarianism is manifested in diverse ways, [… including]: the emphasis on sharing, their attitude towards authority structures, and their general emphasis on equality, especially in relation to gender.

Although in various Malaipantaram settlements there are recognized “headmen” (Muppan), these are largely a function of administrative control introduced by the state via the Forest Department, in order to facilitate communication. Such headmen have little or no control over the lives or movements of other members of the local group. There is, in fact, among the Malaipantaram and other South Indian foragers a marked antipathy towards any form of authority or hierarchy, whether based on wealth, prestige, or power. In their everyday life the emphasis is always on being modest, non-aggressive, and non-competitive, engaging with others in terms of an ethos that puts a fundamental emphasis on mutual aid and on respecting the autonomy of others. […] But as many scholars have indicated, the stress on egalitarian relationships does not simply imply a lack of hierarchy, but is actively engendered by forms of social power – diffuse sanctions or levelling mechanisms. […] It seems to me that to describe this form of social power […] as implying “reverse-dominance hierarchy” (Boehm 1999) or as a form of “governance” (Norstrom 2001) is quite misleading, for the Malaipantaram have a marked aversion to all forms of domination and governance. […] They are, like other South Indian foragers, well attuned to the “art of not being governed” (Scott 2009).”

-Brian Morris. “Anarchism, Individualism, and South Indian Foragers: Memories and Reflections.” 2013.

84K notes

·

View notes

Text

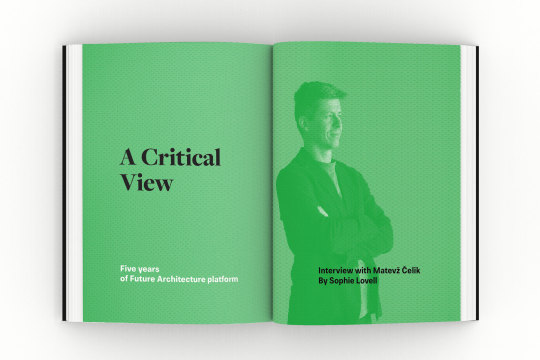

Archifutures 6: Agency

Since 2015 the &beyond collective of writers, editors and designers, have made six volumes of the Archifutures series together with dpr-barcelona for the Future Architecture platform.

Together they form a document of the changing zeitgeist of the last five years in innovative and critical architectural thinking amongst young practitioners and other related fields. The series includes the following five volumes: The Museum, The Studio, The Site, Thresholds and The Apocalypse.

And now &beyond brings you Archifutures Volume 6: Agency, a more hopeful and optimistic field guide to reclaiming the future of architecture.

All six volumes were designed by Diana Portela (in Porto), contain special illustrations by our own Janar Siniloo (Berlin) and were edited by various constellations of myself, Sophie Lovell, and Fiona Shipwright (also Berlin), George Kafka (in Athens) and Rob Wilson (in London).

For each book in the series since its inception, &beyond has sampled the prevailing mood in the room at the FA annual conferences and tempered it with our own experiences to make a volume reflecting the zeitgeist of that moment – expressed through selected projects as well as contributions by invited external experts.As the series developed, each new volume has also reflected a feeling of growing urgency relating to the need for deep, universal, systemic change. Little did we all realise during the FA conference in February 2020 that we were already hurtling towards a global pandemic that was to massively shift the human paradigm and accelerate calls for change.

As we began to commission material for the book during the lockdown in March, some contributors adapted their material slightly to reflect the new circumstances, but most projects, I’m glad to say, already reflected their authors’ assumptions that the need for essential change was a clear given: Disaster is upon us.

Volume 6 is a call to Agency as well as a call to Action. To build agency we first need reflection followed by new narratives that can then progress into action. So in the first chapter, Reflection, I discuss the first five years of the Future Architecture platform with its founder Matevž Čelik and talk about and how this extraordinary collective entity has gathered momentum and sharpened its mission towards one of greater critical production – and becoming an agent of change.

The second chapter is about rectifying imbalance, by turning the Tables (of power), Marina Otero Verzier’s essay here highlights a shift in architectural practice away from commodities and a “nostalgia for a position at the table” towards commons-oriented strategies, politicisation and redistribution of power. It is joined by Miguel Braceli’s Biblioteca Abierta in Venezuela, and the Office of Human Resources’ Agro Commune/ challenging colonial hegemony of production.

Straight lines as impositions of order and separation are a legacy from the past that still very much define our present. Chapter three, Lines, shows that our thinking and responses need to be much less linear and much more inclusive. In her powerful essay called Out of Line, Marie-Louise Richards from the Royal Institute of Arts in Stockholm traces threads of narratives that have been omitted or erased through discriminatory structures. This is followed by projects from 45°N and the Institute of Linear Research, that both use geography to explore and engage with communities and landscapes.

Our fourth chapter covers a topic that has interested the &beyond collective for some time: ruin. “Ruin” is a term that has fascinated architects for centuries, but now we begin to see it in a different context to the usual romantic nostalgia for the past. Here, Will Jennings takes us on a journey through the tropes of the city in ruins and speculative renderings to ask: “What will the ruins of neoliberalism look like?” And Jason Rhys-Parry’s essay An Anticipatory Theory of Ruin Ecology, states that ruins will become the architecture of default rather than the exception and that architects should, therefore anticipate this by designing them to be biodiversity hotspots for the future.

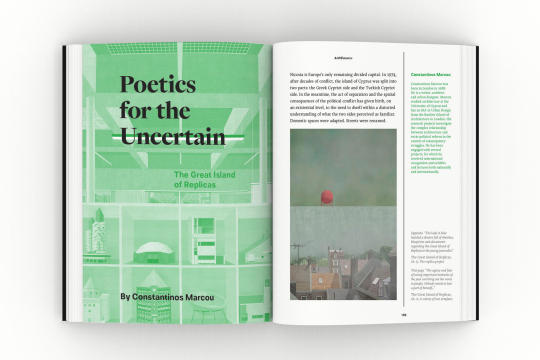

For the fifth chapter, Storytelling, we engineered an exchange between emerging practitioners Paula Brücke and Arian Lehner of Mies.TV and Justinas Dūdėnas and Andrius Ropolas from new platform members Architectūros Fondas. Their exchange became a fantastic conversation and interviewer/interviewee ping-pong about story-making for accessibility and empowerment. Also in this chapter, Un-war Space Lab share their love letter to the Neretva River as the subject of their research about ecologies of violent spatial transformation. And the melancholic illustrations of Constantinos Marcou which form part of his narrative “The Great Island of Replicas” hint at storytelling about the divided island of Cyprus.

Agency, as the capacity to act and exert power or influence, comes through engagement. Therefore, the sixth and final chapter of this volume, Engage, is about how to achieve that. It is also about creating change through direct action. Here, Sam Turner from Architects Climate Action Network shares his activist organisation’s strategies for engagement. We also have an interview in this chapter with Thomas Aquilina – co-director of the London-based New Architecture Writers – about race and space, and how the N.A.W. are developing the critical journalistic skills and editorial connections of Black and minority-ethnic emerging writers in order to generate tools for alternative forms of architecture-making. Then, with their Smart Covenant project, Jack Minchella and his team from Dark Matter Labs share an innovative new legal construct for collective land value infrastructure.

We end the book with another pairing we made between Critical Practice and Unfolding Pavilion. We asked both groups to get together and come up with a form of “mixed media manifesto” for better practice. In response, they curated a “guerilla collaboration” and, to our delight, invited six further practices to create double page spreads of “take-away manifestos”. These were: Arturo Franco and Ana Román, Recetas Urbanas, Coloco, Point Supreme, ateliermob and BC Architects and Studies.