#eliza and david SERVED

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Aelswith and Alfred (eye fucking) in 2x01

For @kingslionheart, @thedarknone, @volvaaslaug, @garunsdottir

#the last kingdom#sevenkingsmustdie#tlk aelswith#tlk alfred#aelswith x alfred#alfred x aelswith#michela you know why I had to make this#her little smirk at the end of the last gif#she's like if we don't have sex you know what I'm going to be doing all alone in my room#I'm utterly obsessed with this scene#this is hotter than any sex scene on this show#she went into that room with A Purpose#I will never get over how they just stared at each other with such blatant desire for like a minute#your honor I love them#eliza and david SERVED#they did this for me#and I am forever indebted to them#they understood the assignment and delivered#god I love them so much#I'm obsessed#this foreplay#anyway I love them#they mean everything to me#they are everything

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

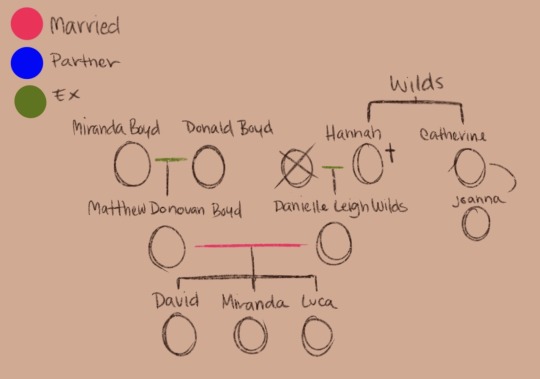

Some family tree stuff I did a while ago but finished today (changed Dan and Katelyn a bit tho after finding out more about their families)

Also to those ppl telling me identical twins aren’t genetic. I never said they were, andreil and Kateaaron have twins cuz twins run in the Hemmicks and Hatfords🫵

Hatford/Wesninski headcanons

Also forgot to write it but Nathan’s dads first name isn’t Natan, it’s his middle name but he discards it when he gets into mob business

HC: Mary doesn’t get along with her older brothers other than Stuart. She’s years younger than them so they forget about her often but also spoil her whenever they have to since she’s the only girl.

David is the heir to the Hatford Crime syndicate but his son dies young and he and his wife spend years grieving before trying again. They arent so lucky. The other boys are pressured to try too but Jacob is shooting blanks and Thomas isn’t keen on even acknowledging his betrothed

When Mary had Nathaniel, her older brothers shunned her for good since she named him Abram. In their eyes, that name belonged to the heir and David had to name his son Isaac instead (Isaac was about a year or two younger than Neil)

Alistair Hatford created the honor and pride of the Hatford name so David wanted to give Abram to his own son in hopes of bringing good luck to their future. To him, Mary had practically killed his son for taking the name for herself

Amrita was Alistair’s fourth wife and being that he killed his last, she made him fall so head over heels for her he’d never so much as lay a hand on her. Amrita knew saying no to a crime boss like him would be suicide so she gave in and manipulated her position to ensure her survival.

Fun fact, Neil (ignoring his fathers color palette) is Amrita’s carbon male copy👀

Each of the contacts Stuart gave them was just the wives/husband families syndicates of their brothers and aunt (Alissa is Turkish, Rochelle is from a smaller French syndicate, Carli is a niece from a Mexican cartel, Maks is Russian, Margarita is Romanian)

Thomas and Charlie are fraternal twins but Thomas and Jacob are the trouble makers of the family

Elizas children cannot inherit the Hatford responsibility because they’re heirs to the Popovs and upon marriage, served her ties to the Hatfords as per agreement

Stuart is acting as head of the family as of current since David has been a mess since Isaac’s death and the other brothers don’t care for challenging him for the position. He would’ve liked Nathaniel to take over but he wouldn’t push him into it after Mary’s death

Minyard/Hemmick/Mckenzie HC

Katelyn’s mom is someone I write differently depending on the au. She’s either divorced/separated from Bruce or she’s dead. Katelyn’s mom is polish but her father is Scottish

Maria has three older siblings and one younger. I hc that even tho she willingly went with Luther, she sort of misses her father and so named her son after him

Tilda used to be known as Tillie by her family, a nickname she loathed

When Tilda got pregnant, Luther demanded she get married or she’d have to get an abortion. However, marriage was too soon and twins were too much so Mr Minyard left

Maude and Evelyn were fraternal twins but weren’t close

Angelica is a good handful of years older than Katelyn but they’re close enough that Katelyn babysits Marcin often

Because I like hiding little tidbits for myself, the Hemmicks have a habit of having two kids max and giving them names with five letters then six. (Ex, Maude, Aaron, Tilda, Nicky are 5, Evelyn, Andrew, and Luther are 6)

Toxic use of religion and neglect pushed Tilda into the life she led but Luther wouldn’t quit on his sister

Just like the Hatfords, the Hemmicks are all short

Boyd/Wilds oc Facts and HC

David is named after Wymack

Miranda is named after Randy

Luca is named after Matt’s nanny, Lucca

Dan’s father was never in the picture before her mother died but Cathy knew what he looked and sounded like (hispanic, tall, and handsome)

Randy and Donald are both tall ppl (6’0 and 6’4) so Matt outgrew them both (6’6)

Miranda goes by Randy too but her parents call her Miranda as to not mix her up. Miranda plays exy her entire life (playing for the Trojans starting line throughout college) and going pro before making Court. She’s the first exy player on the very top to have a clean record on and off court. Miranda has two girlfriends

David aka Dave used to play exy in college but he had a passion for medicine (thanks to uncle Aaron) so he put down his racquet and became a ortho surgeon before settling as a physical therapist for exy players after the stress got to him.

Luca also played exy but dropped it before college since he was never as passionate about it. Randy got him into boxing and he went pro before an injury temporarily had him out of the ring. Dave recommended his best friend to be Luca’s physical therapist. Luca ended up marrying that man

Dan and Matt both make time for their children, whether they’re staying home with Dan or traveling with Matt around the state for his matches

#aftg hc#aftg#aftg oc#all for the game#Hatford family#nathan wesninski#the Hemmicks#neil josten#andrew minyard#aaron minyard#Tilda Minyard#matt boyd#dan wilds#katelyn mckenzie#aftg headcanon

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sunnydale Herald Newsletter, Sunday, October 6th

CORDELIA: Why is it every time I go somewhere with you, it always ends in violence and terror? BUFFY: Welcome to my life. CORDELIA: I don't wanna be in your life. I wanna be in my life. BUFFY: Well, there's the door. Please feel free to walk out at any time and live your life.

~~Homecoming~~

[Drabbles & Short Fiction]

Dream Walk by violettathepiratequeen (Buffy/Spike, G)

Magic in the Moonlight by Skyson (Buffy/Giles, Explicit)

The Urgent Encounter by JammySmut (Buffy/Spike, Explicit)

gravestone by skargasm (Spike/Oz, M)

Final Stop -- Beacon Hills by ElsieHopea (Teen Wolf crossover, Buffy/Stiles, T)

Made with love by Liana_Medea (Angel & Connor, Connor & Colleen Reilly, Buffy/Angel, G)

Why Wasn't I Your Rebound? by ClowniestLivEver (Buffy/Spike, NC-17)

[Chaptered Fiction]

Drawing A Blank - Chapter 1 by EverythingElse (CherryGlowSticks) (Buffy/Spike, not rated [rated R on other sites])

Veni, vidi, vici - Chapter 1 by LadyInBlackandWhite (Harry Potter crossover, Angel, Connor, Angel/Cordelia, Buffy/Spike, Buffy/OC, T)

Make It Stop, Ch. 1 by Sigyn (Buffy/Spike, R)

Breaking Point, Ch. 1 by though_you_try (Buffy/Spike, NC-17)

Something True, Ch. 1 by BewitchedXx (Buffy/Spike, PG-13)

Sold Out, Ch. 1 by Melme1325 (Buffy/Spike, NC-17)

Be Back Before Dawn, Ch. 4 by Blissymbolics (Buffy/Spike, NC-17)

The Degradation of Duality [Series Part 2] Ch. 55 by Ragini (Buffy/Spike, NC-17)

Unholy Matrimony, Ch. 11 by CheekyKitten (Buffy/Spike, NC-17)

The Great Escape from Oz, Ch. 6 by Melme1325 (Buffy/Spike, NC-17)

Fury of the Fallen, Ch. 2 by CheekyKitten (Buffy/Spike, NC-17)

I Live To Serve, Ch. 8 by BlueStories (Warcraft crossover, Buffy, FR21)

The Watcher, Ch. 31 by In Mortal (Buffy/Spike, NC-17)

Viral, Ch. 6 by Harlow Turner (Buffy/Spike, R)

Oh My Goddess, Ch. 6 by Maxine Eden (Buffy/Spike, R)

These Endless Days, Ch. 13 by violettathepiratequeen (Buffy/Spike, PG-13)

[Images, Audio & Video]

Drawing: A baby. by mrsmess (Buffy, worksafe)

A set of Buffy vs. Spike manips about their rivalry by spyder-baby (worksafe)

Buffy/Spike drawings inspired by LadyxB's story «Distraction» by flyora (worksafe)

Shitpost: the tension between 2 men and a bowl of cheerios by slurping-up-grass (The Vampire Diaries crossover, Spike/cheerios, worksafe)

Drawing: Joyce by the-bed-bugs-bit (worksafe)

Four Buffy/Cordelia gifsets by theveryunlikelywonderland (worksafe)

Buffy/Spike manips inspired by Geliot99’s stories, made by Claire (G)

Meme: Check your kids Halloween candy carefully. by whatkindofnameisbuffy (worksafe)

A Buffy/Spike fanvid by everythingselses ()

[Reviews & Recaps]

I just watched the unaired pilot! Honestly not knocking Riff Reagan but Alyson Hannigan is amazing! by OOKAPUCA1993

FRAY appreciation thread by Reddevil8884

Just saw Into the Woods (s5) and I am devastated 😔 by KENZOKHAOS

Phases by Important_Builder317

The Killer In Me S7 E13 (Buffy and the Art of Story Podcast) - Lisa Lilly

[Recs & In Search Of]

BtVS Recs [Buffy/Spike fic, Spike art and and an Eliza Dushku article] by apachefirecat

[Community Announcements]

THE MOUTH OF HELL, an 18+ semi-appless discord-based roleplay inspired by Buffyverse, is looking for players

[Fandom Discussions]

What I want to know is why the Scoobies never gave Spike a soul... by thequeenofsastiel

I wish they had made Spike softer in season 5 [AtS] by thequeenofsastiel

Dawn's kleptomania by Ok_Area9367

Most unlikely couple? by Obiwankimi

Guess what’s on this Spuffy mix I made my friend in high school 😂 by jaduhlynr

Does anyone feel like we never got Giles' mysterious backstory? by -andromeda

Creature of the week by ProfChaos85

Faith fighting against the Circle of the Black Thorn by horriblyfamiliar1

[Articles, Interviews, and Other News]

David Boreanaz and Charisma Carpenter Celebrate Angel's 25th Anniversary [bleedingcool.com reports Instagram posts]

There's going to be a Little Golden Book "Buffy the Vampire Slayer: The Power of Friendship", publication date: July 1, 2025

Submit a link to be included in the newsletter!

Join the editor team :)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top 5 Sci-Fi Movies on Netflix

5. Predestination (2014)

Genre: Science Fiction, Thriller

Actor: Alicia Pavlis, Annabelle Norman, Arielle O’Neill, Ben Prendergast, Carolyn Shakespeare-Allen, Cate Wolfe, Christopher Bunworth, Christopher Kirby, Christopher Sommers, Christopher Stollery, Dennis Coard, Dick York, Elise Jansen, Eliza D’Souza, Eliza Matengu, Ethan Hawke, Felicity Steel, Finegan Sampson, Freya Stafford, Giordano Gangl, Grant Piro, Hayley Butcher, Jim Knobeloch, Katie Avram, Kristie Jandric, Kuni Hashimoto, Lucinda Armstrong Hall, Madeleine West, Maja Sarosiek, Marky Lee Campbell, Milla Simmonds, Monique Heath, Noah Taylor, Noel Herriman, Olivia Sprague, Paul Moder, Raj Sidhu, Rob Jenkins, Sara El-Yafi, Sarah Snook, Sophie Cusworth, Tony Nikolakopoulos, Tyler Coppin, Vanessa Crouch

Director: Michael Spierig, Peter Spierig, The Spierig Brothers

Rating: R

One of the most original time-travel thrillers since 12 Monkeys. A brilliant subversion of the Time Paradox trope, with enough plot twists to keep you entertained until well after the movie is finished. Predestination is an amazing movie with great performances from Ethan Hawke and Sarah Snook. It’s a movie that will feel like Inception, when it comes to messing with your mind and barely anyone has heard of it. It is highly underrated and unknown, sadly.

4. Train to Busan (2016)

Genre: Action, Adventure, Drama, Horror, Science Fiction, Thriller

Actor: Ahn So-hee, An So-hee, Baek Seung-hwan, Cha Chung-hwa, Chang-hwan Kim, Choi Gwi-hwa, Choi Woo-shik, Choi Woo-sung, Dong-seok Ma, Eui-sung Kim, Gong Yoo, Han Ji-eun, Han Sung-soo, Jang Hyuk-jin, Jeong Seok-yong, Jung Seok-yong, Jung Young-ki, Jung Yu-mi, Kim Chang-hwan, Kim Eui-sung, Kim Jae-rok, Kim Joo-heon, Kim Ju-hun, Kim Keum-soon, Kim Soo-ahn, Kim Soo-an, Kim Su-an, Kim Won-Jin, Lee Joo-sil, Lee Joong-ok, Ma Dong-seok, Park Myung-shin, Sang-ho Yeon, Seok-yong Jeong, Shim Eun-kyung, Sohee, Soo-an Kim, Soo-jung Ye, Terri Doty, Woo Do-im, Woo-sik Choi, Ye Soo-jung, Yeon Sang-ho, Yoo Gong, Yu-mi Jeong, Yu-mi Jung

Director: Sang-ho Yeon, Yeon Sang-ho

Lights, camera, VPNaction! Elevate your movie nights with NordVPN. 🎥🔒secure your connection and Download NordVPN . Click now to unlock global cinematic thrills!

A zombie virus breaks out and catches up with a father as he is taking his daughter from Seoul to Busan, South Korea’s second-largest city. Watch them trying to survive to reach their destination, a purported safe zone.

The acting is spot-on; the set pieces are particularly well choreographed. You’ll care about the characters. You’ll feel for the father as he struggles to keep his humanity in the bleakest of scenarios.

It’s a refreshingly thrilling disaster movie, a perfect specimen of the genre.

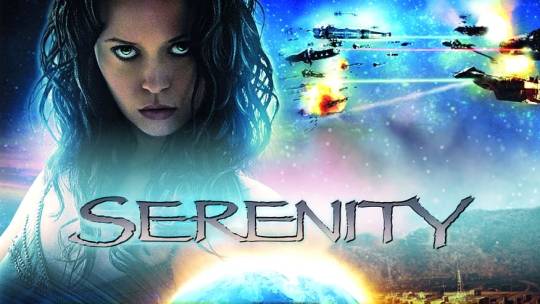

3. Serenity (2005)

Genre: Action, Adventure, Science Fiction, Thriller

Actor: Adam Baldwin, Alan Tudyk, Carrie ‘CeCe’ Cline, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Colin Patrick Lynch, David Krumholtz, Demetra Raven, Dennis Keiffer, Elaine Mani Lee, Erik Weiner, Gina Torres, Glenn Howerton, Hunter Ansley Wryn, Jessica Huang, Jewel Staite, Linda Wang, Logan O’Brien, Marcus Young, Mark Winn, Marley McClean, Matt McColm, Michael Hitchcock, Morena Baccarin, Nathan Fillion, Nectar Rose, Neil Patrick Harris, Peter James Smith, Rafael Feldman, Rick Williamson, Ron Glass, Ryan Tasz, Sarah Paulson, Sean Maher, Summer Glau, Tamara Taylor, Terrell Tilford, Terrence Hardy Jr., Tristan Jarred, Weston Nathanson, Yan Feldman

Director: Joss Whedon

Rating: PG-13

Lights, camera, VPNaction! Elevate your movie nights with NordVPN. 🎥🔒secure your connection and Download NordVPN . Click now to unlock global cinematic thrills!

Serenity is a futuristic sci-fi film that serves as a feature-length continuation of the story-line from the TV program Firefly (2002–2003). The story revolves around the captain (Nathan Fillion) and crew of the titular space vessel that operate as space outlaws, running cargo and smuggling missions throughout the galaxy. They take on a mysterious young psychic girl and her brother, the girl carrying secrets detrimental to the intergalactic government, and soon find themselves being hunted by a nefarious assassin (Chiwetel Ejiofor). The first feature-length film from Joss Whedon (The Avengers), Serenity is a lively and enjoyable adventure, replete with large-scale action sequences, strong characterizations and just the right touch of wry humor. An enjoyable viewing experience that stands alone without demanding that you have familiarity with the original program beforehand.

2. Sorry to Bother You (2018)

Genre: Comedy, Fantasy, Science Fiction

Actor: Armie Hammer, Danny Glover, David Cross, Ed Moy, Forest Whitaker, James D. Weston II, Jermaine Fowler, John Ozuna, Kate Berlant, Lakeith Stanfield, Lily James, Marcella Bragio, Michael X. Sommers, Molly Brady, Omari Hardwick, Patton Oswalt, Robert Longstreet, Rosario Dawson, Steven Yeun, Teresa Navarro, Terry Crews, Tessa Thompson, Tom Woodruff Jr., Tony Toste, W. Kamau Bell

Director: Boots Riley

In the year of the Netflix TV Show Maniac, another absurdist title stole critics’ hearts. Sorry to Bother You is a movie set in an alternate reality, where capitalism and greed are accentuated. Lakeith Stanfield (Atlanta) is a guy called Cassius who struggles to pay his bills. However, when at a tele-marketing job an old-timer tells him to use a “white voice”, he starts moving up the ranks of his bizarre society. A really smart movie that will be mostly enjoyed by those who watch it for its entertaining value, and not so much for its commentary. It is like a Black Mirror episode stretched into a movie.

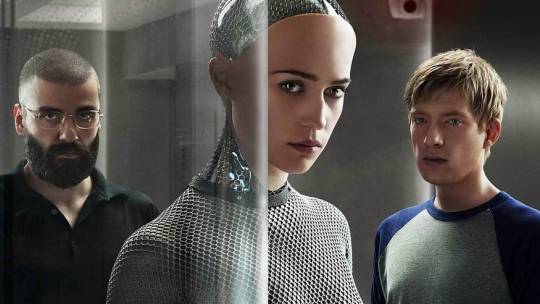

1. Ex Machina (2015)

Genre: Drama, Science Fiction

Actor: Alex Garland, Alicia Vikander, Chelsea Li, Claire Selby, Corey Johnson, Domhnall Gleeson, Elina Alminas, Gana Bayarsaikhan, Oscar Isaac, Sonoya Mizuno, Symara A. Templeman, Symara Templeman, Tiffany Pisani

Director: Alex Garland

Rating: R

Lights, camera, VPNaction! Elevate your movie nights with NordVPN. 🎥🔒secure your connection and Download NordVPN . Click now to unlock global cinematic thrills!

Ex Machina is the directorial debut of Alex Garland, the writer of 28 Days Later (and 28 Weeks Later). It tells the story of Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson from About Time), an IT developer who is invited by a billionaire CEO to participate in a groundbreaking experiment — administering a Turing test to a humanoid robot called Ava (Alicia Vikander). Meeting the robot with feelings of superiority at first, questions of trust and ethics soon collide with the protagonist’s personal views. While this dazzling film does not rely on them, the visual effects and the overall look-feel of Ex Machina are absolutely stunning and were rightly picked for an Academy Award. They make Ex Machina feel just as casually futuristic as the equally stylish Her and, like Joaquin Phoenix, Gleeson aka Caleb must confront the feelings he develops towards a machine, despite his full awareness that ‘she’ is just that. This is possibly as close to Kubrick as anyone got in the 21st century. Ex Machina is clever, thrilling, and packed with engaging ideas.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The following log is evidence of crimes committed by David Alicant (deceased). Text transcribed from audio.

TAPE 2- Found in Fiona Weatherby's childhood home.

[TRANSCRIPT START]

DAVID: Eliza and Thomas Weatherby. Two of the most gifted magicians the world had ever seen. We were inseparable, you see. We served on the side of the people, tracking down the most violent and dangerous magical criminals. It was... pleasant. But it wouldn't last.

They started a family, and so did I. We still kept in touch, but our dueling days had passed. Your father retired and became a doctor, quite a good one, in fact. Me and my wife retired to our mansion and raised our child. Fiona. You and she were born within a week of each other. You, named Thea. You two were best friends.

But Fiona was a very sickly child. She had a rare disease, perhaps a curse, perhaps not. We never found out. But she was dying. And I...

[The following six seconds are inaudible]

DAVID: ...That was unacceptable. Your next destination is St. Benedict's Hospital, where you both were born. It's been abandoned since then. You'll find the next tape where they keep the living dead.

[TRANSCRIPT END]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

19th Wife chapter 15

Click here for the rest of the series!

Click to see the rest of the snark & image descriptions

XV THE PROPHET’S WIFE THE 19TH WIFE CHAPTER SIXTEEN My Wedding Day

Again, kind of feel like the author didn’t have to format his book to the point where we’re in chapter 15 of the dual story of Ann Eliza/Jordan and BeckyLyn… And then chapter 16 of Ann Eliza’s book.

“What number am I?” Brigham reached for my hand to warm it between his. “Number?” “Which wife?” “It’s distasteful to me to put a number next to you, or any woman.” “I appreciate that. But I’d like to know.” “In that case, you are number nineteen.” “Nineteen? What about the others?” “Others?” “At the Lion House?” “They’re friends, but not wives.” “But I’ve heard—” “Ann Eliza, you’ll hear many things now that you’re my wife.” “Nineteen, really? That’s all?” “Nineteen. Really. That’s all.”

Such a charmer. I have to wonder how many of his other wives that he offered the same/similar line to.

I speak the truth when I tell you it was at this moment my bodice tore, exposing my sacred undergarments. According to Brigham himself, a woman must never reveal them to a man, even her husband. Eliza Snow had penned a letter to the women of Zion on the subject: “At the time of connubiality, the wife must open a slot in her sacred garments no bigger than necessary to permit the husband his entry. At no time should she preen before him in anything less than what she might wear on the street, nor reveal to neither his eyes nor hands what lay beneath.”

Going to drop this off here and be on my way. And you were wondering if the entire “Mormon soaking” thing had any grain of truth to it… They’ve always been like this, apparently.

“You don’t like me?” said Brigham. “It’s not that.” “Then what?” He shifted toward me, his great bulk tilting the carriage on its groaning springs. The horseman slowed his team, adjusting for the shifting cargo. I suspect he was used to this sort of situation. Lurching closer, Brigham attempted to kiss me. Soon he was on me, crying, “Tell me you’ve always wanted me as I’ve wanted you!” He pressed me into the corner of the carriage. “Brigham, please—” But his animal had been set free from its cage. […] “Shut the door.” He obeyed my command and settled into the seat with an obvious shame. “What has gotten into you?” I demanded. “I’m sorry, I was overcome. I didn’t mean to alarm you, but you can’t know how beautiful you are.” “Thank you, but you’re not fifteen.”

Why do I get the feeling that if Brigham was around today, he’d be the kind of man who would be constantly divorcing his latest wife the second she hit 25, and finding some naive, barely 18 year old girl to marry next?

When first planning this memoir, I had no intention of dipping into the histories of my fellow wives.

Oh dear Zeus, here we go… Every single time it says “I don’t want to write about this”, this book immediately serves into that huge BUT…

I also know that she intended to be Brigham’s final wife. It was a condition of their marriage. We must give Brigham some credit. He kept his word for two years.

Wow, two whole years! What a saint! Honestly, it’s difficult to fault Amelia for demanding French silk and diamond necklaces. You know he has the money for it, and you know he’s a louse who’ll quickly tire of her. And then where will they be? Amelia will run off with the money from having pawned her silk dresses and diamond necklaces. She’s the smart one, here.

Everything is for them. The voice was Brigham’s. Everything you do now is for your boys.

I love how in the previous chapter, Gilbert had indicated that Ann had given in to Brigham’s demands in order to save her brother. But in Ann’s own words, she doesn’t even MENTION her brother. Everything she’s doing is for her children. What happened to Gilbert and his inability to care for his ~15 children? Who fucking know. Not David Ebershoff, that’s for sure.

On our first anniversary Brigham transferred me, along with my mother and my boys, to Forest Farm, his agricultural compound south of the city. […] What I did not know, nor did Brigham inform me until my arrival, was that most of the farm’s operations were now my responsibility. Forest Farm served as Brigham’s larder. Each day it delivered fresh milk, eggs, butter, vegetables, and meats to his scores of wives and children throughout Salt Lake. Every day in the black of morning I rose to begin my chores in the barn, finishing long after the sun had set. My mother did the same, looking after the house and cooking for the thirty farm hands who tended Brigham’s field of beets and alfalfa, his cocoonery, and his thousand heads of registered cattle. When one chore was complete, five others waited. The end of each day simply brought the beginning of the next. “I’ve never worked so hard in my life,” I said to my mother.

That sounds suspiciously like slavery to me.

Yet in truth, I had never felt more afraid.

Chapter 15 summary: Not even an hour after secretly marrying Brigham did he drag her off to go tend to some church business of two boys killed in a river flood. He drove her back to her mother’s house, where he tried to have his way with her… And then became butthurt after she refused him. After that, they started to have… relations in Brigham’s carriage, which made Ann feel like a common whore. After a few months, he eventually moved her and Elizabeth into a new house, and announced Ann as his wife. He instructed her to dine at the Lion’s House. At this point, Ann pauses to explain about one of the other wives, Amelia, who is nothing but a gold-digger who hates everything and everyone. Although Amelia’s role is limited in the story, it’s easy to see why Ann was quick to stop dining at the Lion’s House. For their one year anniversary, Brigham rewarded her by turning her into an indentured servant on his farm. On sure, Ann and Elizabeth were running the thing, but I doubt that they were allowed to LEAVE. They remained there for three years, upon which Brigham installed them back in a house, but told her that he had no more money. At this point, Ann was forced to take in borders, who were quick to become her friends. They weren’t of the Mormon church, and were quick to slam everything about it. Especially polygamy, when they saw how much Ann was suffering. Despite taking in the boarders, Ann was living hand-to-mouth, and barely getting by. Things came to a head between her and Brigham when she went to him, demanding the money for a new stove in order to better serve her boarders. He almost refused, but Ann put her foot down because he was supposed to be her husband. After leaving his office, she went to the Lion House, where she saw Brigham with Amelia… still wearing diamond necklaces. While Brigham claims to be too broke to let Ann get a new stove. After this, Ann got really, really sick again, but she had her boarder friends to take care of her. As she recovered, one of her boarders, a judge, pointed out that she had a good case for spousal abandonment. Her other friends were quick to point out that it would be a nice test case about plural wives getting away from their shitty husbands. After she got better, two “religious judges” came to basically mock that she’d lost her faith. Ann pointedly looked them in the eye, told them that she no longer believed, who were they to judge what was in her heart, and that Brigham was an absolute louse. Finally, Ann sold off all of her belongings, sent Eddy to live with her father for a while, took Lorenzo, and fled with the help of her friends. She spent the night in a non-Mormon hotel, but in the morning, the news of her flight had already gone through the Mormon community, and a nasty article printed about her in the Mormon paper. However, thanks to the fact that she’d made new friends outside of the cult, she also had an article praising her in the non-Mormon paper. And supporters outside the hotel there to support her in any way they could. However, the final straw for Ann came by way of a letter from Elizabeth, basically saying “You’re no daughter of mine!” Gee thanks, mum! Appreciate the support.

Hire me to fix your book! Copyediting, proofreading, developmental editing, sarcastic editing, and more! 16 years of book-editing experience. Message me anywhere for pricing and further details.

0 notes

Text

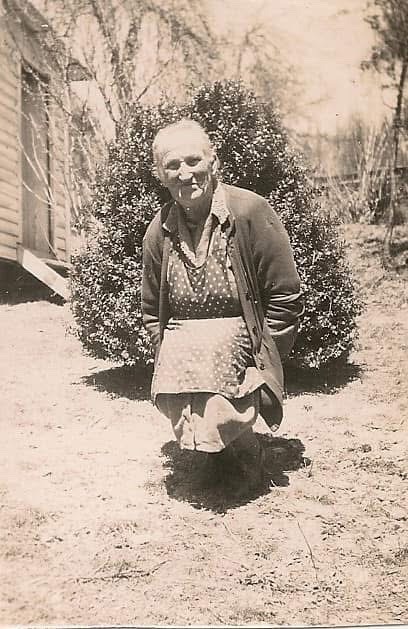

“Granny Guy” served 31 years as a midwife in Avery County, North Carolina

Eliza Millsaps Guy was born October 1, 1869. She was the oldest girl born to Marion and Jane Millsasps near Rush Branch in Watauga County, North Carolina. They then moved to a small farm near the mouth of Beech Creek where Eliza attended public school and lived on a farm.

Eliza married John Guy and to them twelve children were born. She raised her family on a small farm near the mouth of Beech Creek at Beech Mountain. Eliza was considered smart in business affairs and she worked hard on her farm.

In her early life, Eliza became interested in the birth and care of children. She served for many years as a licensed midwife assisting in the birth, care and growth of young children.

"Granny Guy", as she was called, had a smile and a pleasant word for everybody. During her long service as a midwife, she had to travel either foot or horseback, day or night, in rain or a snowstorm. She would be accompanied by a lone guide to a home in the mountainous country where a baby was being born. Eliza served 31 years as a midwife and it was said that she never lost a baby.

Eliza passed away at the age of 87 on May 11, 1958. At the time of her death, she lived on Beech Creek Road at Beech Mountain, NC. Her gravestone reads: “Eliza, or Granny Guy as she was known, served 31 years as a midwife and never lost a baby.”

Eliza is buried at Beech Creek Cemetery in Avery County, NC

(Information from her obituary. Photo from David Harmon via https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/70258614/eliza-guy)

#avery county nc#averycounty#appalachian#appalachian mountains#midwifery#midwife life#north carolina#appalachian culture#western north carolina#appalachia#the south#nc mountains#appalachian history#old history

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

indigo armstrong, twenty nine, fighter pilot

born three months before the start of the great war, indigo spends childhood nestled in a quiet suburb in seattle with his family. he's the oldest of three, the only boy and brother to juniper and, eventually, willow. joseph and adelaide are self proclaimed free spirits and vehement objectors to war in all forms, opposing wilson's call to join the war in 1917. joseph chooses farm labour in another state over enlisting in an attempt to avoid imprisonment for failure to serve.

adelaide takes on parenting indigo and his sister on her own in the absence of joseph but two young children take their toll and things are hard all around. joseph returns a few months after the signing of the armistice, in early 1919, and the family attempts to settle back into the life they'd known. they welcome a third child, another daughter, and decide their family is complete.

the twenties roll by with relatively little fanfare, a move is contemplated in the midst of it in an attempt to stave off using whatever savings they've got to their name but the 30s present a new obstacle and times get even toughter than they had been. indigo turns 16 by the spring of 1930 and starts working wherever they'll let him to start contributing to the household where his father, or mother, cannot. they struggle, pinch pennies and move into smaller and smaller places.

by 1939, indigo is 25 and somewhat transient. much of his time between '32-'39 is spent travelling and working wherever anyone will have him and sending the money back to his family so they can survive. he picks up a steady, long term job as a mechanic on planes and eventually learns to fly them when he's got some downtime.

his parents are furious when he joins the air foce and even moreso when he tells them he's being sent overseas to join the war effort. he knows they'll come around, eventually, and maybe only when the war is over but it sucks, in the moment, for them to decide to stop talking to him, almost pretending like he doesn't exist. he doesn't enjoy the war or think it's right but it feels like the only option and he realizes that flies in the face of everything they'd taught him so he supposes he doesn't blame them but, still.

it's a stable, steady job and, for a time, he doesn't regret it. he flies a single seater, lockheed p38 lightning for a simple fact that he trains on it, he knows it like the back of his hand, and he doesn't want to be responsible for getting anyone but himself back home when all is said and done. he spends the early days of the war flying missions over italy in the mediterranean theater before being transferring to western europe in september '43 where he's been flying escort missions with flying fortresses from the 8th.

indigo is the exact person you want on your side. he's unshakeable, for the most par, always having a level head and the ability to think logically where that might fail with others. he prides himself on being the kind of person everyone can rely on for some perspective.

he does tend to let loose and have fun when he's not flying missions and is stuck on base for whatever reason but he's also a very chill person. he'll go for a drink or a night off at the club but he knows his limits and generally doesn't push them.

(unless david is involved.)

he's a restless sort on the worst days and leans impulsive when he's bored or Very Sure of something (see: his marriage to eliza after 2 months of knowing her) but doesn't see that as a shortcoming.

despite however kept together he may appear on the outside and how little seems to shake him, he's not at all at ease with the war. he compartmentalizes and turns off his guilt by saying it's a job. it's a job and when he's done, he gets to go home to his wife and he never wants to get involved in anything like this again.

certified Wife Guy™

1 note

·

View note

Text

by Adam Kirsch

In Elif Batuman’s 2022 novel Either/Or, the narrator, Selin, goes to her college library to look for Prozac Nation, the 1994 memoir by Elizabeth Wurtzel. Both of Harvard’s copies are checked out, so instead she reads reviews of the book, including Michiko Kakutani’s in the New York Times, which Batuman quotes:

“Ms. Wurtzel’s self-important whining” made Ms. Kakutani “want to shake the author, and remind her that there are far worse fates than growing up during the 70’s in New York and going to Harvard.”

It’s a typically canny moment in a novel that strives to seem artless. Batuman clearly recognizes that every criticism of Wurtzel’s bestseller—narcissism, privilege, triviality—could be applied to Either/Or and its predecessor, The Idiot, right down to the authors’ shared Harvard pedigree. Yet her protagonist resists the identification, in large part because she doesn’t see herself as Wurtzel’s contemporary. Wurtzel was born in 1967 and Batuman in 1977. This makes both of them members of Generation X, which includes those born between 1965 and 1980. But Selin insists that the ten-year gap matters: “Generation X: that was the people who were going around being alternative when I was in middle school.”

I was born in 1976, and the closer we products of the Seventies get to fifty, the clearer it becomes to me that Batuman is right about the divide—especially when it comes to literature. In pop culture, the Gen X canon had been firmly established by the mid-Nineties: Nirvana’s Nevermind appeared in 1991, the movie Reality Bites in 1994, Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill in 1995. Douglas Coupland’s book Generation X, which popularized the term, was published in 1991. And the novel that defined the literary generation, Infinite Jest, was published in 1996, when David Foster Wallace was about to turn thirty-four—technically making him a baby boomer.

Batuman was a college sophomore in 1996, presumably experiencing many of the things that happen to Selin in Either/Or. But by the time she began to fictionalize those events twenty years later, she joined a group of writers who defined themselves, ethically and aesthetically, in opposition to the older representatives of Generation X. For all their literary and biographical differences, writers like Nicole Krauss, Teju Cole, Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, and Tao Lin share some basic assumptions and aversions—including a deep skepticism toward anyone who claims to speak for a generation, or for any entity larger than the self.

That skepticism is apparent in the title of Zadie Smith’s new novel, The Fraud. Smith’s precocious success—her first book, White Teeth, was published in 2000, when she was twenty-four—can make it easy to think of her as a contemporary of Wallace and Wurtzel. In fact she was born in 1975, two years before Batuman, and her sensibility as a writer is connected to her generational predicament.

Smith’s latest book is, most obviously, a response to the paradoxical populism of the late 2010s, in which the grievances of “ordinary people” found champions in elite figures such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Rather than write about current events, however, Smith has elected to refract them into a story about the Tichborne case, a now-forgotten episode that convulsed Victorian England in the 1870s.

In particular, Smith is interested in how the case challenges the views of her protagonist, Eliza Touchet. Eliza is a woman with the sharp judgment and keen perceptions of a novelist, though her era has deprived her of the opportunity to exercise those gifts. Her surname—pronounced in the French style, touché—evokes her taste for intellectual combat. But she has spent her life in a supportive role, serving variously as housekeeper and bedmate to her cousin William Harrison Ainsworth, a man of letters who churns out mediocre historical romances by the yard. (Like most of the novel’s characters, Ainsworth and Touchet are based on real-life historical figures.)

Now middle-aged, Eliza finds herself drawn into public life by the Tichborne saga, which has divided the nation and her household as bitterly as any of today’s political controversies. Like all good celebrity trials, the case had many supporting players and intricate subplots, but at heart it was a question of identity: Was the man known as “the Claimant” really Roger Tichborne, an aristocrat believed to have died in a shipwreck some fifteen years earlier? Or was he Arthur Orton, a cockney butcher who had emigrated to Australia, caught wind of the reward on offer from Roger’s grief-stricken mother, and seized the chance of a lifetime? In the end, a jury decided that he was Orton, and instead of inheriting a country estate he wound up in a jail cell. What fascinates Smith, though, is the way the Tichborne case became a political cause, energizing a movement that took justice for “Sir Roger” to be in some way related to justice for the common man.

Eliza is a right-minded progressive who was active in the abolitionist movement in the 1830s. Proud of her judgment, she sees many problems with the Claimant’s story and finds it incredible that anyone could believe him. To her dismay, however, she lives with someone who does. William’s new wife, Sarah, formerly his servant, sees the Claimant as a victim of the same establishment that lorded over her own working-class family. The more she is informed of the problems with the Claimant’s argument, the more obdurate she becomes: “HE AIN’T CALLED ARTHUR ORTON IS HE,” she yells, “THEM WHO SAY HE’S ORTON ARE LYING.”

What Smith is dramatizing, of course, is the experience of so many liberal intellectuals over the past decade who had believed themselves to be on the side of “the people” only to find that, whether the issue was Brexit or Trump or COVID-19 protocols, the people were unwilling to heed their guidance, and in fact loathed them for it. It is in order to get to the bottom of this phenomenon that Eliza keeps attending the Tichborne trial, in much the same spirit that many liberal journalists reported from Trump rallies. Things get even more complicated when she befriends a witness for the defense, Mr. Bogle, who is among the Claimant’s main supporters even though he began his life as a slave on a Jamaica plantation managed by Edward Tichborne, the Claimant’s supposed father.

Though much of the novel deals with the case and the history of slavery in Britain’s Caribbean colonies, it is first and foremost the story of Eliza Touchet, and how her exposure to the trial alters her sense of the world and of herself. “The purpose of life was to keep one’s mind open,” she reflects, and it is this ability to see things from another perspective that makes her a novelist manqué.

Open-mindedness, even to the point of moral ambiguity, is one of the chief values Smith shares with her literary contemporaries. These writers grew up during a period of heightened tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, then took their first steps toward adult consciousness just as the Cold War concluded. They came of age in the brief period that Francis Fukuyama called “the end of history.”

Fukuyama’s description, famously premature though it was, still captures something crucial about the context in which the children of the Seventies began to think and write. While the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe is sometimes remembered as the “Revolutions of 1989,” the mood it created in the West was hardly revolutionary. After 1989, there was little of the “bliss was it in that dawn to be alive” sentiment that had animated Wordsworth during the French Revolution. Instead, the ambient sense that history was moving steadily in the right direction encouraged writers to see politics as less urgent, and less morally serious, than inward experience.

In the fiction that defined the pre-9/11 era, political phenomena tended to assume cartoon form. Wallace’s Infinite Jest features an organization of Quebecois separatists called Les Assassins des Fauteuils Rollents—that is, the Wheelchair Assassins. In Smith’s White Teeth, one of the main characters joins a militant group named KEVIN, for Keepers of the Eternal and Victorious Islamic Nation. The attacks on the Twin Towers and the war on terror would put an end to jokes like these, but for a decade or so it was possible to see ideological extremism as a relic fit for spoofing—as with KGB Bar, a popular New York literary venue that opened in 1993.

For the young writers of that era, the most important battles were not being fought abroad but at home, and within themselves. Their enemies were the forces of cynicism and indifference that Wallace depicted in Infinite Jest, set in a near-future America stupefied by consumerism, mass entertainment, and addictive substances. The great balancing act of Wallace’s fiction was to truthfully represent this stupor while holding open the possibility that one could recover from it, the way the residents of the novel’s Ennet House manage to recover from their addictions. This dialectical mission is responsible for the spiraling self-consciousness that is the most distinctive (and, to some readers, the most annoying) aspect of his writing.

Dave Eggers set himself an analogous challenge in his 2000 memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. Writing about a childhood tragedy—the nearly simultaneous deaths from cancer of his mother and father, which left the young Eggers with custody of his eight-year-old brother—he aimed to do full justice to his despair while still insisting on the validity of hope. “This did not happen to us for naught, I can assure you,” he writes,

there is no logic to that, there is logic only in assuming that we suffered for a reason. Just give us our due. I am bursting with the hopes of a generation, their hopes surge through me, threaten to burst my hardened heart!

By the end of the millennium, this was the familiar voice of Generation X. Loquacious and self-involved, its ironic grandiosity barely concealed a sincere grandiosity about its moral mission, which was to defeat despair and foster genuine human connection. Jonathan Franzen, Wallace’s realist rival, titled a book of essays How to Be Alone, and for these writers, loneliness was the great problem that literature was created to solve. “If writing was the medium of communication within the community of childhood, it makes sense that when writers grow up they continue to find writing vital to their sense of connectedness,” Franzen wrote in his much-discussed essay “Perchance to Dream,” published in these pages in 1996. Eggers seems to have taken this idea literally, creating a nonprofit, 826 Valencia, that advertises writing mentorship for underserved students as a way of “building community” and rectifying inequality.

If sincerity and connection were the greatest virtues for these writers, the greatest sin was “snark.” That word gained literary currency thanks to a manifesto by Heidi Julavits in the first issue of The Believer, the magazine she co-founded in 2003 with the novelist Vendela Vida (Eggers’s wife) and the writer Ed Park. The title of the essay—“Rejoice! Believe! Be Strong and Read Hard!”—like the title of the magazine, insisted that literature was an essentially moral enterprise, a matter of goodness, courage, and love. To demur from this vision was to reveal a smallness of soul that Julavits called snark: “wit for wit’s sake—or, hostility for hostility’s sake,” a “hostile, knowing, bitter tone of contempt.” For Kafka, a book was an axe for the frozen sea within; for the older cohort of Gen X writers, it was more like a hacksaw to cut through the barred cell of cynicism.

This was the environment—quiescent in politics, self-consciously sincere in literature—in which Smith and her contemporaries came of age. Just as they started to publish their first books, however, the stopped clock of history resumed with a vengeance. It is unnecessary to list the series of political and geopolitical shocks that have occurred since 2000. For the millennial generation, adulthood has been defined by apocalyptic fears, political frenzy, and glimpses of utopia, whether in Chicago’s Grant Park on election night 2008 or in New York’s Zuccotti Park during Occupy Wall Street in 2011.

The children of the Seventies tend to feel out of place in this new world. It’s not that they naïvely looked forward to a future of peace and harmony and are offended to find that it has not materialized. It is rather that their literary gaze was fixed within at an early age, and they continue to believe that the most authentic way to write about history is as the deteriorating climate through which the self moves.

The self, meanwhile, they approach with mistrust—a reaction against the heart-on-sleeve sincerity of their elders. Many of them have turned to autofiction, a genre which is often criticized as narcissistic—a way of shrinking the world to fit into the four walls of the writer’s room. In fact, it has served these writers as an antidote to the grandiosity of memoir, which tends to falsify in the direction of self-flattery—as this generation learned from the spectacular implosion of James Frey’s 2003 bestseller, A Million Little Pieces. By admitting from the outset that it is not telling the truth about the author’s life, autofiction makes it possible to emphasize the moral ambiguities that memoir has to apologize for or hide. That makes it useful for writers who are not in search of goodness, neither within themselves nor in political movements.

For Sheila Heti, this resistance to goodness takes the form of artistic introspection, which busier people tend to judge as selfish and idle. In How Should a Person Be?, from 2010, a character named Sheila has dinner with a young theater director named Ben, who has just returned with a friend from South Africa. “It was just such a crushing awakening of the colossal injustice of the way our world works economically,” he says of their trip, that he now wonders whether his work as a theater director—“a very narcissistic activity”—is morally justifiable. Yet nothing could be more narcissistic, in Heti’s telling, than such moral preening, and Sheila instinctively resists it. “They are so serious. They lectured me about my lack of morality,” she complains. She loathes the idea of having “to wear on the outside one’s curiosity, one’s pity, one’s guilt,” when art is concerned with what happens inside, which can only be observed with effort and in private. “It’s time to stop asking questions of other people,” she tells herself. “It is time to just go into a cocoon and spin your soul.”

Teju Cole’s 2011 novel Open City offers a more ambivalent version of the same idea. Julius, the narrator, can’t justify his aesthetic self-absorption on the grounds that he is an artist, as Sheila does, since he is a psychiatrist. It’s an ironic choice of profession for a man we come to know as guarded and aloof. Cole builds a portrait of Julius through his daily interactions with other people, like the taxi driver whose cab he enters gruffly. “The way you came into my car without saying hello, that was bad,” the driver rebukes him. “Hey, I’m African just like you, why you do this?” Julius apologizes for this small breach of solidarity, but insincerely: “I wasn’t sorry at all. I was in no mood for people who tried to lay claims on me.”

Indeed, for most of the novel he is alone, meditating in Sebaldian fashion on the atrocities of history as he takes long walks through Manhattan. When, during a trip to Brussels, he meets a man who wants to intervene in history—Farouq, a young Moroccan intellectual who declares that “America is a version of Al-Qaeda”—Julius is decidedly unimpressed:

There was something powerful about him, a seething intelligence, something that wanted to believe itself indomitable. But he was one of the thwarted ones. His script would stay in proportion.

Open City can’t be said to endorse Julius’s aesthetic solipsism. On the contrary, the last chapter finds him trapped on a fire escape outside Carnegie Hall in the rain, a striking symbol of a man isolated by culture. Just moments before, he had been united with the rest of the audience in Mahlerian rapture; now, he reflects, “my fellow concertgoers went about their lives oblivious to my plight,” as he tries to avoid slipping and falling to his death. The scene is Cole’s acknowledgment that aesthetic consciousness remains passive and solipsistic even when experienced in common, and that danger demands a different kind of solidarity—one that is active, ethical, even political. Yet Cole conjures Julius’s aristocratic fatalism in such intimate detail that the “Rejoice! Believe!” approach—to literature, and to life—can only appear childish.

Writers of this cohort do sometimes try to imagine a better world, but they tend to do so in terms that are metaphysical rather than political, moving at one bound from the fallen present to some kind of messianic future. In her 2022 novel Pure Colour, Heti tells the story of a woman named Mira whose grief over her father’s death prompts her to speculate about what Judaism calls the world to come. In Heti’s vision, this is not a place to which the soul repairs after death, nor is it some kind of revolutionary political arrangement; rather, it is an entirely new world that God will one day create to replace the one we live in, which she calls “the first draft of existence.”

The hardest thing to accept, for Heti’s protagonist, is that the end of our world will mean the disappearance of art. “Art would never leave us like a father dying,” Mira says. “In a way, it would always remain.” But over the course of Pure Colour, she comes to accept that even art is transitory. In a profoundly self-accusing passage, she concludes that a better world might even require the disappearance of art, since

art is preserved on hearts of ice. It is only those with icebox hearts and icebox hands who have the coldness of soul equal to the task of keeping art fresh for the centuries, preserved in the freezer of their hearts and minds.

Tao Lin’s unnerving, affectless autofiction leaves a rather different impression than Heti’s, and he has sometimes been identified as a voice from the next generation, the millennials. But his 2021 novel Leave Society shows him thinking along similar lines as the children of the Seventies. In Taipei, from 2013, Lin’s alter ego is named Paul, and he spends most of the novel joylessly eating in restaurants and taking mood-altering drugs. In Leave Society he is named Li, but he is recognizably the same person, perched on a knife-edge between extreme sensitivity and neurotic withdrawal. In the interim, he has decided that the cure for his troubles, and the world’s, lies in purging the body of the toxins that infiltrate it from every direction.

Like Heti, Lin anticipates a great erasure. All of recorded history, he writes, has been merely a “brief, fallible transition . . . from matter into the imagination.” Sometime soon we will emerge into a universe that bears no resemblance to the one we know. Writers, Lin concludes, participate in this process not by working for social change but by reforming the self. “Li disliked trying to change others,” Lin writes, and believed that “people who are concerned about evil and injustice in the world should begin the campaign against those things at their nearest source—themselves.”

One way or another, writers in this cohort all acknowledge the same injunction—even the ones who struggle against it. In his new book of poems, The Lights, Ben Lerner strives to elaborate an idea of redemption that is both private and social:

I don’t know any songs, but won’t withdraw. I am dreaming the pathetic dream of a pathos capable of redescription, so that corporate personhood becomes more than legal fiction. A dream in prose of poetry, a long dream of waking.

The dream of uniting the sophistication of art with the straightforwardness of justice also animates Lerner’s fiction, where it often takes the form of rueful comedy. In 10:04, the narrator cooks dinner for an Occupy Wall Street protester, but when asked how often he has been to Zuccotti Park, he dodges the question. His activism is limited to cooking, which he pompously describes as a way of being “a producer and not a consumer alone of those substances necessary for sustenance and growth within my immediate community.” That the dream never becomes more than a dream betrays Lerner’s similarity to Lin, Heti, and Cole, who frankly acknowledge the hiatus between art and justice, though without celebrating it.

Zadie Smith has always been too deeply rooted in the social comedy of the English novel to embrace autofiction, yet she also registers this disconnect, as can be seen in the way her influences have shifted over time. When it was first published, White Teeth was compared to Infinite Jest and Don DeLillo’s Underworld as a work of what James Wood called “hysterical realism.” The book’s arch humor, proliferating plot, and penchant for exaggeration owe much to the author Wood identified as the “parent” of that genre: Charles Dickens.

When Smith says that a woman “needed no bra—she was independent, even of gravity,” she is borrowing Dickens’s technique of making characters so intensely themselves that their essence saturates everything around them—as when he writes of the nouveau riche Veneerings, in Our Mutual Friend, that “their carriage was new, their harness was new, their horses were new, their pictures were new, they themselves were new.” Dickens is a guest star in The Fraud, appearing at several of William Ainsworth’s dinner parties, and the news of his death prompts Eliza Touchet to offer an apt tribute: “She knew she lived in an age of things . . . and Charles had been the poet of things.”

But Dickens, who at another point in the novel is gently disparaged for his moralizing “sermons,” is no longer the presiding genius of Smith’s fiction. (Smith wrote in a recent essay that her first principle in taking up the historical novel was “no Dickens,” and she expressed a wry disappointment that he had forced his way into the proceedings.) Her 2005 novel, On Beauty, was a reimagining of E. M. Forster’s Howards End, and while her style has continued to evolve from book to book, Forster’s influence has been clear ever since, in everything from her preference for short chapters to her belief in “keep[ing] one’s mind open.”

Smith’s affinity for Forster owes something to their analogous historical situations. An Edwardian liberal who lived into the age of fascism and communism, Forster defended his values—“tolerance, good temper and sympathy,” as he put it in the 1939 essay “What I Believe”—with something of a guilty conscience, recognizing that the militant younger generation regarded them as “bourgeois luxuries.”

At the end of The Fraud, Eliza encounters Mr. Bogle’s son Henry, who has grown disgusted with his father’s quietism and become a political radical. He reproaches her for being more interested in understanding injustice than in doing something about it, proclaiming:

By God, don’t you see that what young men hunger for today is not “improvement” or “charity” or any of the watchwords of your Ladies’ Societies. They hunger for truth! For truth itself! For justice!

This certainty and urgency is the opposite of keeping one’s mind open, and while Mrs. Touchet—and Smith—aren’t prepared to say that it is wrong, they are certain that it’s not for them: “This essential and daily battle of life he had described was one she could no more envisage living herself than she could imagine crossing the Atlantic Ocean in a hot air balloon.”

Whether they style themselves as humanists or aesthetes, realists or visionaries, the most powerful writers who were born in the Seventies share this basic aloofness. To the next generation, the millennials, their disengagement from the collective struggle may seem reprehensible. For me, as I suspect is the case for many readers my age, it is part of what makes them such reliable guides to understanding, if not the times we live in, then at least the disjunction between the times and the self that must try to negotiate them.

0 notes

Text

by Adam Kirsch

In Elif Batuman’s 2022 novel Either/Or, the narrator, Selin, goes to her college library to look for Prozac Nation, the 1994 memoir by Elizabeth Wurtzel. Both of Harvard’s copies are checked out, so instead she reads reviews of the book, including Michiko Kakutani’s in the New York Times, which Batuman quotes:

“Ms. Wurtzel’s self-important whining” made Ms. Kakutani “want to shake the author, and remind her that there are far worse fates than growing up during the 70’s in New York and going to Harvard.”

It’s a typically canny moment in a novel that strives to seem artless. Batuman clearly recognizes that every criticism of Wurtzel’s bestseller—narcissism, privilege, triviality—could be applied to Either/Or and its predecessor, The Idiot, right down to the authors’ shared Harvard pedigree. Yet her protagonist resists the identification, in large part because she doesn’t see herself as Wurtzel’s contemporary. Wurtzel was born in 1967 and Batuman in 1977. This makes both of them members of Generation X, which includes those born between 1965 and 1980. But Selin insists that the ten-year gap matters: “Generation X: that was the people who were going around being alternative when I was in middle school.”

I was born in 1976, and the closer we products of the Seventies get to fifty, the clearer it becomes to me that Batuman is right about the divide—especially when it comes to literature. In pop culture, the Gen X canon had been firmly established by the mid-Nineties: Nirvana’s Nevermind appeared in 1991, the movie Reality Bites in 1994, Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill in 1995. Douglas Coupland’s book Generation X, which popularized the term, was published in 1991. And the novel that defined the literary generation, Infinite Jest, was published in 1996, when David Foster Wallace was about to turn thirty-four—technically making him a baby boomer.

Batuman was a college sophomore in 1996, presumably experiencing many of the things that happen to Selin in Either/Or. But by the time she began to fictionalize those events twenty years later, she joined a group of writers who defined themselves, ethically and aesthetically, in opposition to the older representatives of Generation X. For all their literary and biographical differences, writers like Nicole Krauss, Teju Cole, Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, and Tao Lin share some basic assumptions and aversions—including a deep skepticism toward anyone who claims to speak for a generation, or for any entity larger than the self.

That skepticism is apparent in the title of Zadie Smith’s new novel, The Fraud. Smith’s precocious success—her first book, White Teeth, was published in 2000, when she was twenty-four—can make it easy to think of her as a contemporary of Wallace and Wurtzel. In fact she was born in 1975, two years before Batuman, and her sensibility as a writer is connected to her generational predicament.

Smith’s latest book is, most obviously, a response to the paradoxical populism of the late 2010s, in which the grievances of “ordinary people” found champions in elite figures such as Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. Rather than write about current events, however, Smith has elected to refract them into a story about the Tichborne case, a now-forgotten episode that convulsed Victorian England in the 1870s.

In particular, Smith is interested in how the case challenges the views of her protagonist, Eliza Touchet. Eliza is a woman with the sharp judgment and keen perceptions of a novelist, though her era has deprived her of the opportunity to exercise those gifts. Her surname—pronounced in the French style, touché—evokes her taste for intellectual combat. But she has spent her life in a supportive role, serving variously as housekeeper and bedmate to her cousin William Harrison Ainsworth, a man of letters who churns out mediocre historical romances by the yard. (Like most of the novel’s characters, Ainsworth and Touchet are based on real-life historical figures.)

Now middle-aged, Eliza finds herself drawn into public life by the Tichborne saga, which has divided the nation and her household as bitterly as any of today’s political controversies. Like all good celebrity trials, the case had many supporting players and intricate subplots, but at heart it was a question of identity: Was the man known as “the Claimant” really Roger Tichborne, an aristocrat believed to have died in a shipwreck some fifteen years earlier? Or was he Arthur Orton, a cockney butcher who had emigrated to Australia, caught wind of the reward on offer from Roger’s grief-stricken mother, and seized the chance of a lifetime? In the end, a jury decided that he was Orton, and instead of inheriting a country estate he wound up in a jail cell. What fascinates Smith, though, is the way the Tichborne case became a political cause, energizing a movement that took justice for “Sir Roger” to be in some way related to justice for the common man.

Eliza is a right-minded progressive who was active in the abolitionist movement in the 1830s. Proud of her judgment, she sees many problems with the Claimant’s story and finds it incredible that anyone could believe him. To her dismay, however, she lives with someone who does. William’s new wife, Sarah, formerly his servant, sees the Claimant as a victim of the same establishment that lorded over her own working-class family. The more she is informed of the problems with the Claimant’s argument, the more obdurate she becomes: “HE AIN’T CALLED ARTHUR ORTON IS HE,” she yells, “THEM WHO SAY HE’S ORTON ARE LYING.”

What Smith is dramatizing, of course, is the experience of so many liberal intellectuals over the past decade who had believed themselves to be on the side of “the people” only to find that, whether the issue was Brexit or Trump or COVID-19 protocols, the people were unwilling to heed their guidance, and in fact loathed them for it. It is in order to get to the bottom of this phenomenon that Eliza keeps attending the Tichborne trial, in much the same spirit that many liberal journalists reported from Trump rallies. Things get even more complicated when she befriends a witness for the defense, Mr. Bogle, who is among the Claimant’s main supporters even though he began his life as a slave on a Jamaica plantation managed by Edward Tichborne, the Claimant’s supposed father.

Though much of the novel deals with the case and the history of slavery in Britain’s Caribbean colonies, it is first and foremost the story of Eliza Touchet, and how her exposure to the trial alters her sense of the world and of herself. “The purpose of life was to keep one’s mind open,” she reflects, and it is this ability to see things from another perspective that makes her a novelist manqué.

Open-mindedness, even to the point of moral ambiguity, is one of the chief values Smith shares with her literary contemporaries. These writers grew up during a period of heightened tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, then took their first steps toward adult consciousness just as the Cold War concluded. They came of age in the brief period that Francis Fukuyama called “the end of history.”

Fukuyama’s description, famously premature though it was, still captures something crucial about the context in which the children of the Seventies began to think and write. While the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe is sometimes remembered as the “Revolutions of 1989,” the mood it created in the West was hardly revolutionary. After 1989, there was little of the “bliss was it in that dawn to be alive” sentiment that had animated Wordsworth during the French Revolution. Instead, the ambient sense that history was moving steadily in the right direction encouraged writers to see politics as less urgent, and less morally serious, than inward experience.

In the fiction that defined the pre-9/11 era, political phenomena tended to assume cartoon form. Wallace’s Infinite Jest features an organization of Quebecois separatists called Les Assassins des Fauteuils Rollents—that is, the Wheelchair Assassins. In Smith’s White Teeth, one of the main characters joins a militant group named KEVIN, for Keepers of the Eternal and Victorious Islamic Nation. The attacks on the Twin Towers and the war on terror would put an end to jokes like these, but for a decade or so it was possible to see ideological extremism as a relic fit for spoofing—as with KGB Bar, a popular New York literary venue that opened in 1993.

For the young writers of that era, the most important battles were not being fought abroad but at home, and within themselves. Their enemies were the forces of cynicism and indifference that Wallace depicted in Infinite Jest, set in a near-future America stupefied by consumerism, mass entertainment, and addictive substances. The great balancing act of Wallace’s fiction was to truthfully represent this stupor while holding open the possibility that one could recover from it, the way the residents of the novel’s Ennet House manage to recover from their addictions. This dialectical mission is responsible for the spiraling self-consciousness that is the most distinctive (and, to some readers, the most annoying) aspect of his writing.

Dave Eggers set himself an analogous challenge in his 2000 memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. Writing about a childhood tragedy—the nearly simultaneous deaths from cancer of his mother and father, which left the young Eggers with custody of his eight-year-old brother—he aimed to do full justice to his despair while still insisting on the validity of hope. “This did not happen to us for naught, I can assure you,” he writes,

there is no logic to that, there is logic only in assuming that we suffered for a reason. Just give us our due. I am bursting with the hopes of a generation, their hopes surge through me, threaten to burst my hardened heart!

By the end of the millennium, this was the familiar voice of Generation X. Loquacious and self-involved, its ironic grandiosity barely concealed a sincere grandiosity about its moral mission, which was to defeat despair and foster genuine human connection. Jonathan Franzen, Wallace’s realist rival, titled a book of essays How to Be Alone, and for these writers, loneliness was the great problem that literature was created to solve. “If writing was the medium of communication within the community of childhood, it makes sense that when writers grow up they continue to find writing vital to their sense of connectedness,” Franzen wrote in his much-discussed essay “Perchance to Dream,” published in these pages in 1996. Eggers seems to have taken this idea literally, creating a nonprofit, 826 Valencia, that advertises writing mentorship for underserved students as a way of “building community” and rectifying inequality.

If sincerity and connection were the greatest virtues for these writers, the greatest sin was “snark.” That word gained literary currency thanks to a manifesto by Heidi Julavits in the first issue of The Believer, the magazine she co-founded in 2003 with the novelist Vendela Vida (Eggers’s wife) and the writer Ed Park. The title of the essay—“Rejoice! Believe! Be Strong and Read Hard!”—like the title of the magazine, insisted that literature was an essentially moral enterprise, a matter of goodness, courage, and love. To demur from this vision was to reveal a smallness of soul that Julavits called snark: “wit for wit’s sake—or, hostility for hostility’s sake,” a “hostile, knowing, bitter tone of contempt.” For Kafka, a book was an axe for the frozen sea within; for the older cohort of Gen X writers, it was more like a hacksaw to cut through the barred cell of cynicism.

This was the environment—quiescent in politics, self-consciously sincere in literature—in which Smith and her contemporaries came of age. Just as they started to publish their first books, however, the stopped clock of history resumed with a vengeance. It is unnecessary to list the series of political and geopolitical shocks that have occurred since 2000. For the millennial generation, adulthood has been defined by apocalyptic fears, political frenzy, and glimpses of utopia, whether in Chicago’s Grant Park on election night 2008 or in New York’s Zuccotti Park during Occupy Wall Street in 2011.

The children of the Seventies tend to feel out of place in this new world. It’s not that they naïvely looked forward to a future of peace and harmony and are offended to find that it has not materialized. It is rather that their literary gaze was fixed within at an early age, and they continue to believe that the most authentic way to write about history is as the deteriorating climate through which the self moves.

The self, meanwhile, they approach with mistrust—a reaction against the heart-on-sleeve sincerity of their elders. Many of them have turned to autofiction, a genre which is often criticized as narcissistic—a way of shrinking the world to fit into the four walls of the writer’s room. In fact, it has served these writers as an antidote to the grandiosity of memoir, which tends to falsify in the direction of self-flattery—as this generation learned from the spectacular implosion of James Frey’s 2003 bestseller, A Million Little Pieces. By admitting from the outset that it is not telling the truth about the author’s life, autofiction makes it possible to emphasize the moral ambiguities that memoir has to apologize for or hide. That makes it useful for writers who are not in search of goodness, neither within themselves nor in political movements.

For Sheila Heti, this resistance to goodness takes the form of artistic introspection, which busier people tend to judge as selfish and idle. In How Should a Person Be?, from 2010, a character named Sheila has dinner with a young theater director named Ben, who has just returned with a friend from South Africa. “It was just such a crushing awakening of the colossal injustice of the way our world works economically,” he says of their trip, that he now wonders whether his work as a theater director—“a very narcissistic activity”—is morally justifiable. Yet nothing could be more narcissistic, in Heti’s telling, than such moral preening, and Sheila instinctively resists it. “They are so serious. They lectured me about my lack of morality,” she complains. She loathes the idea of having “to wear on the outside one’s curiosity, one’s pity, one’s guilt,” when art is concerned with what happens inside, which can only be observed with effort and in private. “It’s time to stop asking questions of other people,” she tells herself. “It is time to just go into a cocoon and spin your soul.”

Teju Cole’s 2011 novel Open City offers a more ambivalent version of the same idea. Julius, the narrator, can’t justify his aesthetic self-absorption on the grounds that he is an artist, as Sheila does, since he is a psychiatrist. It’s an ironic choice of profession for a man we come to know as guarded and aloof. Cole builds a portrait of Julius through his daily interactions with other people, like the taxi driver whose cab he enters gruffly. “The way you came into my car without saying hello, that was bad,” the driver rebukes him. “Hey, I’m African just like you, why you do this?” Julius apologizes for this small breach of solidarity, but insincerely: “I wasn’t sorry at all. I was in no mood for people who tried to lay claims on me.”

Indeed, for most of the novel he is alone, meditating in Sebaldian fashion on the atrocities of history as he takes long walks through Manhattan. When, during a trip to Brussels, he meets a man who wants to intervene in history—Farouq, a young Moroccan intellectual who declares that “America is a version of Al-Qaeda”—Julius is decidedly unimpressed:

There was something powerful about him, a seething intelligence, something that wanted to believe itself indomitable. But he was one of the thwarted ones. His script would stay in proportion.

Open City can’t be said to endorse Julius’s aesthetic solipsism. On the contrary, the last chapter finds him trapped on a fire escape outside Carnegie Hall in the rain, a striking symbol of a man isolated by culture. Just moments before, he had been united with the rest of the audience in Mahlerian rapture; now, he reflects, “my fellow concertgoers went about their lives oblivious to my plight,” as he tries to avoid slipping and falling to his death. The scene is Cole’s acknowledgment that aesthetic consciousness remains passive and solipsistic even when experienced in common, and that danger demands a different kind of solidarity—one that is active, ethical, even political. Yet Cole conjures Julius’s aristocratic fatalism in such intimate detail that the “Rejoice! Believe!” approach—to literature, and to life—can only appear childish.

Writers of this cohort do sometimes try to imagine a better world, but they tend to do so in terms that are metaphysical rather than political, moving at one bound from the fallen present to some kind of messianic future. In her 2022 novel Pure Colour, Heti tells the story of a woman named Mira whose grief over her father’s death prompts her to speculate about what Judaism calls the world to come. In Heti’s vision, this is not a place to which the soul repairs after death, nor is it some kind of revolutionary political arrangement; rather, it is an entirely new world that God will one day create to replace the one we live in, which she calls “the first draft of existence.”

The hardest thing to accept, for Heti’s protagonist, is that the end of our world will mean the disappearance of art. “Art would never leave us like a father dying,” Mira says. “In a way, it would always remain.” But over the course of Pure Colour, she comes to accept that even art is transitory. In a profoundly self-accusing passage, she concludes that a better world might even require the disappearance of art, since

art is preserved on hearts of ice. It is only those with icebox hearts and icebox hands who have the coldness of soul equal to the task of keeping art fresh for the centuries, preserved in the freezer of their hearts and minds.

Tao Lin’s unnerving, affectless autofiction leaves a rather different impression than Heti’s, and he has sometimes been identified as a voice from the next generation, the millennials. But his 2021 novel Leave Society shows him thinking along similar lines as the children of the Seventies. In Taipei, from 2013, Lin’s alter ego is named Paul, and he spends most of the novel joylessly eating in restaurants and taking mood-altering drugs. In Leave Society he is named Li, but he is recognizably the same person, perched on a knife-edge between extreme sensitivity and neurotic withdrawal. In the interim, he has decided that the cure for his troubles, and the world’s, lies in purging the body of the toxins that infiltrate it from every direction.

Like Heti, Lin anticipates a great erasure. All of recorded history, he writes, has been merely a “brief, fallible transition . . . from matter into the imagination.” Sometime soon we will emerge into a universe that bears no resemblance to the one we know. Writers, Lin concludes, participate in this process not by working for social change but by reforming the self. “Li disliked trying to change others,” Lin writes, and believed that “people who are concerned about evil and injustice in the world should begin the campaign against those things at their nearest source—themselves.”

One way or another, writers in this cohort all acknowledge the same injunction—even the ones who struggle against it. In his new book of poems, The Lights, Ben Lerner strives to elaborate an idea of redemption that is both private and social:

I don’t know any songs, but won’t withdraw. I am dreaming the pathetic dream of a pathos capable of redescription, so that corporate personhood becomes more than legal fiction. A dream in prose of poetry, a long dream of waking.

The dream of uniting the sophistication of art with the straightforwardness of justice also animates Lerner’s fiction, where it often takes the form of rueful comedy. In 10:04, the narrator cooks dinner for an Occupy Wall Street protester, but when asked how often he has been to Zuccotti Park, he dodges the question. His activism is limited to cooking, which he pompously describes as a way of being “a producer and not a consumer alone of those substances necessary for sustenance and growth within my immediate community.” That the dream never becomes more than a dream betrays Lerner’s similarity to Lin, Heti, and Cole, who frankly acknowledge the hiatus between art and justice, though without celebrating it.

Zadie Smith has always been too deeply rooted in the social comedy of the English novel to embrace autofiction, yet she also registers this disconnect, as can be seen in the way her influences have shifted over time. When it was first published, White Teeth was compared to Infinite Jest and Don DeLillo’s Underworld as a work of what James Wood called “hysterical realism.” The book’s arch humor, proliferating plot, and penchant for exaggeration owe much to the author Wood identified as the “parent” of that genre: Charles Dickens.