#execution of Louis XVI

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The French Revolution: 10 Key Events That Toppled a Monarchy

The French Revolution, a period of profound social and political upheaval in France from 1789 to 1799, remains one of the most pivotal and transformative events in human history. It wasn’t merely a series of protests; it was a radical dismantling of an ancient regime, a violent overthrow of monarchy, aristocracy, and the Church’s entrenched power, in favor of principles like liberty, equality,…

#abolition of feudalism#Ancien Régime#Bastille Day#causes of French Revolution#Committee of Public Safety#consequences of French Revolution#Consulate#coup d&039;état 1799#Danton#Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen#democracy origins#Directory#end of French Revolution#Enlightenment ideals#Estates-General#European history#execution of Louis XVI#execution of Marie Antoinette#fall of monarchy France#Flight to Varennes#French Empire#French history#French Republic#fundamental rights#Great Fear#guillotine#human rights history#impact of French Revolution#July 14 1789#key events French Revolution

0 notes

Text

i do feel for louis capet and i don't think he was a "bad person" (not that i believe in such a thing anyways) he truly seems to have been a decent guy. but that is so entirely not the point of why he was killed and i do get genuinely angry when people are like "poor louis xvi actually wanted to free all the slaves he just didn't manage it in his short rule plagued by the revolution 😔" because that doesn't actually matter. as the french (and haitian) revolutionaries discovered there is actually a ceiling to what can be accomplished without revolutionary action and louis capet opposed that revolutionary action. it doesn't matter what reforms he or any other royals wanted. the system he staked his life and his family's life on was unreformable and he either never realized this or turned away from the realization because it was inconvenient. no matter what he wanted to happen he opposed what could have/did actually realize it and was therefore an enemy to progress and liberation. that's the whole reason he had to die and it doesn't mean you can't be sad about it but you gotta understand it didn't happen because the revolutionaries were a bunch of meanies who didn't know louis was actually a very nice young man who just had a special interest in locks or anything. to use the common parlance, deeply unserious!

#not an invitation for anyone to argue about whether he was a cool guy or not because the whole point is that that is not the point#frev#louis xvi#anyway im in robespierres camp i have no personal love or hate for the man but his execution was a necessity#also not trying to fact check the thing abt slavery rn cause 1. like i said it doesnt matter#and 2. im on vacation and can't do research rn

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

i will forever wonder what the fuck happened at the Triwizard tournament of 1792 the French Revolution date is just like catnip to me

#all we know is something about a cockatrice#and the year of Louis xvi's execution#worldbuilding in hp#I don't want to know what jkr had in mind here#hp#hp meta#harry potter#I just want to make up something interesting#hp history

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The late King of this Country has been publickly executed. He died in a Manner becoming his Dignity. Mounting the Scaffold he express’d anew his Forgiveness of those who persecuted him and a Prayer that his deluded People might be benefited by his Death. On the Scaffold he attempted to speak but the commanding Officer Santerre ordered the Drums to be beat. The King made two unavailing Efforts but with the same bad Success. The Executioners threw him down and were in such Haste as to let fall the Axe before his Neck was properly placed so that he was mangled. It would be needless to give you an affecting Narrative of Particulars.

--Gouverneur Morris to Thomas Jefferson, 25 January 1793.

#louis xvi#french history#french revolution#letters#quotes#!! finally a contemporary claim that the execution was botched.#John Hardman writes that it was it was because his neck was “too fat to fit” but he provides no citation for it.#I went down this rabbit hole before but it was before a bunch of stressful stuff happened and I can't remember what I learned

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Execution of Louis XVI – Revolution and Its Lingual Ripples

Louis XVI’s execution on January 21, 1793, symbolized the fall of monarchy and the rise of republicanism. It also introduced terms like guillotine and reign of terror into English political discourse.

January 21, 1793 The Execution of Louis XVI and the Rise of Revolutionary Ideals On January 21, 1793, King Louis XVI of France was executed by guillotine, marking a turning point in the French Revolution and an event that reverberated globally. This monumental act symbolized the dismantling of absolute monarchy and the rise of revolutionary ideals. Its impact was not confined to France; it…

#citizen#democracy#French Revolution vocabulary#guillotine#guillotine symbolism#Louis XVI execution#political history#reign of terror#republic#rise of republicanism#sans-culottes

0 notes

Text

youtube

A Heartbreaking Betrayal - Assassin's Creed Unity: The Execution

#Assassin's Creed Unity#The Execution mission#Arno Dorian#Élise de la Serre#King Louis XVI#Ubisoft games#historical assassination missions#AC Unity walkthrough#Assassin's Creed drama#Place de la Révolution#Dame Z Gaming#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Why Aziraphale is completely ridiculous in the Bastille scene (and I love him so much for it)

A while ago I posted a comparison of Aziraphale and Crowley's costumes in the 1793 flashback in Good Omens and I wanted to add these little tidbits. (Because they haunt me.)

I feel like most people know this but IF YOU DON'T, Paris in 1793 is right in the middle of something called La Terreur.

HISTORY LESSON If you didn't learn this in school the French Revolution was when, after years of escalating social tension, a coalition representing the working classes of France revolted against the monarchy, violently overthrew King Louis XVI, and declared France to be a republic.

The new National Convention governing France ruled that King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette were traitors to the people of France because of how they had spent ridiculous amounts of money on luxuries for themselves while vast numbers of the lower classes were literally starving to death. (keep the bold in mind - wealth and class disparities were one of the key causes of the whole-ass revolution)

In 1793 (year of the flashback) both the King and Queen were executed by guillotine for their crimes.

This kicks of something called The Reign of Terror (La Terreur if you want to be French about it). A multi-year-long period in which the National Convention goes on a bloody witch hunt for any and every member of the middle or upper classes who could even possibly be considered a traitor by those same standards.

If you A) had money or privilege, and B) had ever used your money or privilege to treat yourself, you were getting executed. Over 25,000 people died during the Reign of Terror, half of them by guillotine. In fact, the iconic guillotine was used because it was physically impossible to keep up with the sheer number of people they were executing in Paris every single day.

Some things that could get you killed (actually and completely seriously) during the Reign of Terror:

Implying in any way you were sympathetic to the monarchy

Having a noble title

Having expensive things

Wearing expensive, luxurious clothes (*cough* AZIRAPHALE)

helping or sympathizing with anyone who did any of the above

a working-class person saying you were mean to them once

And then there's this bitch...

I AM NOBILITY PLEASE KILL ME So we have established that Paris in 1793 is in the middle of a frenzied, state-sanctioned bloodbath in which the working classes are massacring everyone even remotely nobility-adjacent. And in the middle of this frenzy, Aziraphale proceeds to roll up in Paris in this outfit:

How will this outfit get him killed? Let me count the ways...

First off- at this point everyone with even the tiniest shred of self- preservation is hiding the fact that they are in any way associated with the monarchy. The wealthy are straight-up abandoning mansions. The middle-class are plastering over decorations to make their house look 'poor'. The only people dressed remotely decent are the guys leading the National Convention and that's just because nobody can stop them. Everyone else is in 24/7 peasant cosplay or else they are covering themselves in cockades and sashes on to show they're pro-Republic.

Aziraphale is basically a giant shiny white sign saying I AM NOBILITY PLEASE KILL ME.

First off the lace jabot and lace cuffs are both associated with the old-school wealthy in the 1790's.

His coat is also decorated in gold braid and silver buttons, which are both marks of wealth and luxury.

He basically looks like he works for Louis XIV - not just rich, but old school rich.

We know it's his natural hair color, but hair powdering (with clay and starch) had been a big trend with the rich all throughout the 18th century to get that clean white venerable look . To someone who doesn't know it's natural, it would very much look like he's wearing hair powder.

He's wearing shades of cream and white, which are very hard to keep clean and clearly states that the wearer is rich and can afford the upkeep necessary to keep an outfit like that stain-free.

He's wearing white knee-breeches and stockings, also called culottes. See above about laundry and how rich you had to be to wear white, but also working-class men wore long pants like this:

A large faction involved in the Revolution were the Sans-Culottes (no-culottes aka we wear long pants LIKE GOOD OLD WORKING MEN). Culottes are specifically associated with everything the revolution hated. That's right - Aziraphale is literally wearing The Fanciest of Fancy Pants in a city where a group called The Men Against Fancy Pants are running around murdering people.

And then there are his shoes.

Oh god his shoes

I could do a whole post about Aziraphale's blessed little white satin pumps and how ridiculous they are.

Actually I might just do that because this is getting so long and I still have to talk about the brioche.

So I can't remember if it's in the script book or if it's from Neil Gaiman's tumblr, but it's apparently canon (?) that Aziraphale was going around in that outfit asking people where he could get crepes and brioche when he was arrested.

The Affair of the Brioches

So... uh... we've all heard the line attributed to Marie Antoinette- how when she was told that her people were starving because there was no bread left in Paris, she famously said...

It's morphed into 'let them eat cake', but the line is first recorded as, "Then let them eat brioches."

While it's unlikely she ever actually said it, the important thing is that... people in 1793 would have thought she said it. It was used as political smear to show how arrogant and out of touch the monarchy was. Marie Antoinette in particular was reviled by the people of France, who thought she was the main cause of their economic problems. That's why she was executed too.

Bread and brioche and the lines between poverty and privilege were a big thing in Revolutionary France. There was a lot of political connotation to what you ate. The French Revolution came about because of decades of suffering among the lower classes of France. It wasn't something that some dudes just decided to do. The people of Paris have been through years of the absolute worst, most oppressive poverty and starvation you can imagine, all while watching the rich throw money around crazy.

So let us recap.

Aziraphale is dressed so ridiculously posh that he looks like a joke parody of a nobleman... and he is bumbling around Paris during the Reign of Terror. Asking people. For brioche. How I imagine everyone looked at him:

It is so astoundingly tone deaf and tactless. He is basically cosplaying as Marie Antoinette and then going around asking the poor for cake.

I just.... Aziraphale. babygirl. no. oh no. You're lucky they even bothered to take you to prison. I am amazed Crowley ever let him live that down.

I have no conclusion other than this. Aziraphale is ridiculous and I love him so much.

YES YOU REALLY SHOULD SIR.

#good omens#aziraphale#good omens meta#good omens costumes#aziraphale's white satin pumps#ineffable husbands

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Guillotine earrings commemorating the execution of Louis XVI during France’s Reign of Terror, c. 1793

#guillotine#guillotine earrings#guillotineearrings#louis xvi#france#jewelry#earrings#vintage jewelry#18th century#antique jewelry#reign of terror#french revolution#1789#1799#1793#1794#18th century history#jewellery#french politics#french history

939 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exhibition 1793-1794 at the Carnavalet Museum (Part I)

For anyone interested in the French Revolution, a visit to the Carnavalet Museum is essential. Though the museum covers the history of Paris from its very beginnings to the present, it’s also home to the world’s largest collection of revolutionary artefacts. Which makes sense, given that Paris was the epicentre of it all.

Frankly, if you plan to explore it all, you’ll want to set aside a good 3–4 hours. For those focused solely on the French Revolution, head straight to the second floor, where you can get through the collection in under an hour. Best of all, the permanent collection is free, making it a brilliant way to spend an afternoon in the city on a budget.

Currently, though, there’s a special treat on offer. Running from 16 October 2024 to 16 February 2025, the museum is hosting an exhibition dedicated to my favourite (and arguably the most chaotic) year of the revolution: Year II (1).

Now, since the family and I were in Reims for a long weekend, I somehow managed (possibly after too much Champagne) to convince my husband to drive 150 kilometres to Paris just so I could see Robespierre’s unfinished signature. It helped that the kids were on board, too. Yes, the four-year-old fully recognises Robespierre by portrait. The one-year-old is, predictably, indifferent.

So, slightly worse for wear after a ridiculous amount of Champagne tastings, off we went to the museum.

1. Why Year II?

Because it was a catastrophe. No. Really. Let me explain, in a very overly-simplified summary:

In Year II, France was plunged into an unparalleled storm of internal and external crises that would define the Revolution’s most radical year and ultimately mark its turning point.

Internally, the government was riven by factional divides, economic collapse, and civil war. The Jacobins (2) took control of the Convention, sidelining the federalist Girondins (3), aligning themselves with the sans-culottes (4), and arguing that only extreme measures could preserve the Revolution. Meanwhile, the more radical Enragés (5) demanded harsh economic policies to shield the poor from spiralling inflation and food shortages. The Convention introduced the Maximum Général (6) to placate them, which capped essential prices; however, enforcement was haphazard, fuelling discontent across the country. At the same time, the Indulgents (7) called for a reduction in violence and a return to clemency.

Externally, France’s situation was equally dire, encircled by the First Coalition—a formidable alliance of Britain, Austria, Prussia, Spain, and the Dutch Republic, all intent on crushing the Revolution before it spread further. With the execution of Louis XVI, France found itself diplomatically isolated, and the army was, frankly, a shambles. Most officers were either nobles or incompetent (8), and the soldiers were inadequately trained and equipped. In a desperate bid to defend the Republic, the Convention issued the Levée en Masse (9) in August 1793, sparking revolts in many cities and outright civil war in the West.

Confronted with this barrage of existential threats, the Convention dialled up its response in spectacular fashion, unleashing what we now know as the Terror—a period of sweeping repression backed by some rather questionable legislation. As you can likely guess from the name alone, this was a brilliant idea…

Put simply: by the end of Year II, nearly all the key figures who had spearheaded the Revolution up to that point were dead. And no, they didn’t slip away peacefully in their sleep from some ordinary epidemic. They met their end at the guillotine.

In short, Year II wasn’t just the Revolution's most radical and defining phase—it was also the year the Revolution itself died. Yes, the Revolution, in its truest, purest, most uncompromising form, met its end the moment the guillotine's blade struck Robespierre’s neck.

2. Overview of the exhibition

The visit opens with the destruction of the 1791 Constitution and closes with Liberty, an allegorical figure of the Republic depicted as a woman holding the Declaration of the Rights of Man in her right hand. In between, the experience is structured around five main themes:

A New Regime: The Republic

Paris: Revolution in Daily Life

Justice: From Ordinary to Exceptional

Prisons and Execution Sites

Beyond Legends

More than 250 artefacts are featured, including paintings, sculptures, decorative arts, historical items, wallpapers, posters, and furniture. The layout is carefully structured around these themes, with a distinct use of colour to set the tone: the first three sections have a neutral palette, while the final two glow in vivid red, creating a very nice change in atmosphere.

What I appreciated most was how the descriptions handle the messy legacy of Year II. The texts actually admit that, while some Parisians saw this year as a bold step towards equality and utopia, for others it was an absolute nightmare. This balance is refreshing, even if things are a bit simplified (because how could they not be?), and it gives a well-rounded view of a wildly complicated time.

In this first part, I'll focus on the first two sections, as the latter three fit together neatly and deserve a deep dive of their own. Besides, there's so much to unpack that I'll likely exceed Tumblr's word limit (and the patience of anyone reading this).

3. A New Regime: The Republic

The first section covers the shift from the Ancien Régime to the First Republic, and, fittingly, it starts with a smashed relic of the old order: the Constitution of 1791. After the monarchy’s fall and the republic’s proclamation in September 1792, the old constitution was meaningless. Though it technically remained in force for a few months, it was replaced by the Constitution of Year I in 1793, marking the end of France’s brief experiment with a constitutional monarchy. In May 1793, the old document was ceremonially obliterated with the “national sledgehammer”—a bit dramatic, perhaps, but Year II was nothing if not dramatic.

This section zeroes in on the governance of the new republic, featuring the Constitution of Year I, portraits of convention members, objects from the Committee of Public Safety and the National Convention (including a folder for Robespierre’s correspondence), and national holiday memorabilia. There’s even a nice nod to Hérault de Séchelles (10) as a principal author of the republican constitution.

3.1 Martyrdom as a political tool

Interestingly, the exhibition places a heavy emphasis on the concept of martyrdom. A significant portion of this first area is dedicated to the Death of Marat (11) and, to a lesser extent, the assassination of Le Peletier (12). It’s a clever angle since martyrs—whether well-known figures or nameless soldiers—have always been handy for rallying public opinion. The revolutionary government of Year II understood this all too well and wielded the concept to its full advantage.

In this spirit, the middle of this section features a reproduction of David’s Death of Marat, several drawings from Marat’s funeral, Marat’s mortuary mask, a supposed piece of his jaw, and more. Notably absent are any issues of L’Ami du Peuple, as though the display suggests Marat’s death was more impactful to the Republic’s narrative than his actual writings. I’d agree with that—the moment he died, he was elevated to a mythic status, and his legacy as a martyr of Year II took on a life of its own.

4. Paris: Revolution in Daily Life

While the first section focuses on the workings of governance, this part delves into Year II’s impact on ordinary Parisians. This period stands out for two reasons: France was in economic and political turmoil (wars, both internal and external, aren’t exactly budget-friendly), yet it also managed to introduce some remarkably forward-thinking legislation aimed at improving the lives of the common people.

4.1 The Paris Commune & Paranoia

To understand life in Paris during Year II, we can’t overlook the role of the Paris Commune (13). Rooted in the revolutionary spirit of the Estates General of 1789 and officially formalised by the law of 19 October 1792, the Commune was the governing body responsible for Paris. Divided into forty-eight sections, each with its own assembly, it gave citizens a strong voice in electing representatives and local officials. Led by a mayor, a general council, and a municipal body, the Commune handled essential civic matters like public works, subsistence, and policing.

From 2 June 1793 to 27 July 1794 (the height of Year II), the Commune implemented the policies of the Montagnard (14) Convention, which aimed to build a social structure grounded in the natural rights of man and citizen, reaffirmed on 24 June 1793. This social programme sought to guarantee basic rights such as subsistence (covering food, lighting, heating, clothing, and shelter), work (including access to tools, raw materials, and goods), assistance (support for children, the elderly, and the sick; rights to housing and healthcare), and education (fostering knowledge and preserving arts and sciences).

All this unfolded in an atmosphere thick with paranoia and intense policing; enemies were believed to lurk everywhere. The display does a solid job of capturing this side of the Paris Commune, featuring various illustrations that urged people to conform to new revolutionary norms—wear the cockade, play your part in the social order, fight for and celebrate the motherland, and so on.

One of my favourite pieces was the record of cartes de sûreté (safety cards) from one of the 48 Parisian sections. Made compulsory for Parisians in April 1793, these cards were meant to confirm that their holders weren’t considered “suspects” in a climate thick with paranoia. This small, seemingly random document—issued or revoked at the discretion of an equally random Revolutionary Committee—had the power to decide a person’s freedom or the lack of it.

At the risk of sounding sentimental, in the study of history, we often focus on broad events and overlook the "little guy" who lived through them. But here, this record reminds us that behind each document was, in fact, a real person. And that this very real person was trying to make their way through a reality that, 230 years ago, must have felt stifling and, at times, terrifying.

4.2 Education

A significant spotlight is rightly placed on education in this exhibition section, given the sweeping changes it underwent during the Revolution.

Before 1789, Paris was well-supplied with educational institutions. Eleven historic colleges and a semi-subsidised university offered prestigious studies in theology, law, medicine, and the arts, drawing students from across France. Inspired by Enlightenment ideals, boarding schools and specialised courses in subjects like science and mathematics had sprung up, mainly catering to the middle class, while working-class children attended charity schools. Private adult education also provided technical and scientific training. The catch? Most of these were church-operated.

Revolutionary policies targeting the Church caused a mass departure of teachers, financial difficulties, and restrictions on hiring unsalaried educators. Military demands, economic turmoil, and protests added to the strain on schools. Even the Sorbonne (15) was shut down in 1792, and by late 1793, nearly all Parisian colleges were closed except for Louis-le-Grand (16), which was renamed École Égalité. With the teacher shortage and soaring inflation, a handful of institutions struggled on.

This left the Convention and the Paris Commune scrambling to find new ways to educate the young, and they rose (or at least attempted to rise) to the occasion. On 19 December 1793, the Bouquier Decree aimed to establish free, secular, and mandatory primary education—a remarkable move, though it never fully materialised due to lack of funding.

With France at war, the Convention turned public education towards the needs of a nation in crisis. Throughout 1793 and 1794, new scientific and technical programmes sprang up to meet urgent demands, combat food shortages, and push social progress. Thousands of students were trained in saltpetre refinement (vital for gunpowder), and scientific knowledge spread beyond chemists to artisans and tin workers. In the final months of Year II, a saltpetre refinement zone was set up, the École de Mars was founded to rapidly train young men in military techniques, and the École Centrale des Travaux Publics (future École Polytechnique) was established to develop engineers in military-technical fields.

The education display features a fascinating array of educational degrees, lists of primary school students, and instructor rosters. Although a bit more context on the educational upheaval would have been helpful, the artefacts themselves are intriguing. Placed in the context of the rest of the exhibit, it’s clear that the new educational system wasn’t just about breaking away from the Ancien Régime; it was also very deliberately and openly crafted to instil republican ideals. Nothing illustrates this better than the way Joseph Barra(17) was promoted as a model for students at the École de Mars.

And, of course, this section also showcases one of the most enduring legacies of the Revolution: the introduction of the metric system and modern standardised measurements.

4.3 The (lack of) Women in Year II

The women of Year II were not real women. They were symbols—or so the imagery from the era would have us believe. There is shockingly little about the actual experiences of women in the collective memory of Year II.

Women played active roles in the Revolution. They filled the Assembly’s tribunes as spectators, mobilised in the sections, founded clubs, joined public debates, signed petitions, and even participated in mixed societies. In many cases, they worked side by side with men to bring about the Republic of Year II. So where are they?

Well, they’re certainly not prominent in this exhibition—but that’s not the fault of the organisers. It’s a reflection of how the time chose to represent them. In revolutionary imagery, women became allegories: symbols of Liberty, wisdom, the Republic, or the ideal mother raising citizens for the state, often reduced to stereotypes and caricatures. Rarely were they depicted as part of the public sphere.

The absence of a serious discourse on women’s rights in this part of the exhibition speaks volumes and is true to the period itself. At the time, there was no cohesive movement for women’s rights, and while specific individuals pushed for aspects of female citizenship, these efforts lacked unity or a common cause. Eventually, being perceived as too radical, all women's clubs were closed in 1973.

4.4 Dechristianisation

In my view, dechristianisation was perhaps the greatest misstep of the various governments from 1789 onwards. Not because I think religion should be central to people’s lives—not at all—but because, in 18th-century France, it simply was essential for most. The reasoning behind this attack on religion was sound enough: no government wants to be beholden to a pope in Rome who had heavily supported the deposed king. But in practice, the application of this principle was far from effective.

By Year II, Parisian authorities were still grappling with the fallout from the Civil Constitution of the Clergy (1790), which had left Catholics split between two competing churches: the constitutional church, loyal to the Revolution, and the refractory church, loyal to Rome. Patriotic priests suspected refractory priests of using their influence to fuel counter-revolutionary sentiment—a suspicion that only intensified the general atmosphere of paranoia.

As tension mounted, it devolved, as these things often do, into outright destruction. On 23 October 1793, the Commune of Paris ordered the removal of all monuments that "encouraged religious superstitions or reminded the public of past kings." Religious statues were removed, replaced by images of revolutionary martyrs like Le Peletier, Marat, and Chalier (19), in an effort to supplant the cult of saints with the cult of republican heroes.

The exhibition presents this wave of destruction with artefacts from ruined religious statues, the most striking being the head of one of the Kings of Judah from Notre-Dame’s facade. These 28 statues were dragged down and mutilated in a frenzy against royalist symbols in 1793. . Ironically, they weren’t even French kings; they were Old Testament kings, supposedly ancestors of Christ—a fact that most people at the time were probably blissfully unaware of. But hey, destruction in the name of ignorance is nothing new, is it?

Many in the Convention and the Commune were atheists and enthusiastically supported the secularisation of public life. Unfortunately, they didn’t represent the majority of the French population. To bridge this gap, Robespierre proposed a "moral religion" without clergy, a way for citizens to unite and celebrate a shared, secularised liberty. In December 1793, the Convention passed a decree granting "unlimited liberty of worship," leading to the Festival of the Supreme Being, held in Paris and throughout France on 8 June 1794.

As with so much in Year II, the "Supreme Being" affair was a logical solution to a pressing problem that ended up blowing up in Robespierre’s face—by now, you might detect a pattern. But that’s a story for Part II of this already very long post.

5. Conclusion to Part 1

Overall, the exhibition presents the first two themes—A New Regime: The Republic and Paris: Revolution in Daily Life—in a balanced way, which I really appreciate. I was expecting a bit more sensationalism, given that Year II is known for its brutality, but instead, it provides a thoughtful overview of how the Republic was structured and the impact this had on Parisians.

The range of media and text offers a good dive into key points, especially on everyday life during the period. I didn’t listen to everything, but from what I saw, the explanations were well done. Naturally, since the exhibition is aimed at the general public, many aspects are simplified.

For younger audiences (pre-teens, perhaps?), the exhibit includes 11 watercolour illustrations by Florent Grouazel and Younn Locard. These two artists attempt to fill the gaps by depicting events from the period that lack contemporary representation (like the destruction of the Constitution with the “national sledgehammer” on 5 May 1793—an event documented but unillustrated at the time). For each scene, they created a young character as an actor or observer, sometimes just a witness to history, to make the scene more immersive. It’s a nice touch, though easy to overlook if you’re not paying close attention.

In Part II, I’ll share my thoughts on the remaining themes: Justice, Prisons and Execution Sites, and Beyond Legends. And yes, a lot of that will involve Thermidor—how could it not?

In the meantime, if you made it this far… well, I’m impressed!

Notes

(1) Year II: Refers to the period from 22 September 1793 to 21 September 1794 in the French Revolutionary calendar.

(2) Jacobins: A political group advocating social reform and, by 1793, strongly promoting Republican ideals. Most revolutionaries were, or had once been, members of the Jacobin club, though by Year II, Robespierre stood out as its most prominent figure.

(3) Girondins: A conservative faction within the National Convention, representing provincial interests and, to some extent, supporting constitutional monarchy. Key figures included Brissot and Roland.

(4) Sans-culottes: Working-class Parisians who championed radical changes and economic reforms to support the poor. The name “sans-culottes” (meaning "without knee breeches") symbolised their rejection of aristocratic dress in favour of working-class trousers.

(5) Enragés: An ultra-radical group demanding strict economic controls, such as price caps on essentials, to benefit the poor. Led by figures like Jacques Roux and, to some extent, Jacques Hébert, the Enragés urged the Convention to fully break from the Ancien Régime.

(6) Maximum Général: A 1793 law imposing price caps on essential goods to curb inflation and aid the poor. Though well-intended, it was difficult to enforce and stirred resentment among merchants.

(7) Indulgents: A faction led by Danton and Desmoulins advocating a relaxation of the severe repressive measures introduced in Year II, calling instead for clemency and a return to more moderate governance.

(8) Incompetence: At the Revolution’s outset, military positions were primarily held by nobles. By Year II, these noble officers were often dismissed due to mistrust, and their replacements—particularly in the civil conflict in the West—were frequently inexperienced, and some, quite frankly, incompetent.

(9) Levée en Masse: A mass conscription decree of 1793 requiring all able-bodied, unmarried men aged 18 to 25 to enlist. This unprecedented mobilisation extended to the wider population, with men of other ages filling support roles, women making uniforms and tending to the wounded, and children gathering supplies.

(10) Hérault de Séchelles: A lawyer, politician, and member of the Committee of Public Safety during Year II, known primarily for helping to draft the Constitution of 1793.

(11) Jean-Paul Marat: A radical journalist and politician, fiercely supportive of the sans-culottes and advocating revolutionary violence in his publication L’Ami du Peuple. Assassinated in 1793, he became the Revolution’s most famous martyr.

(12) Louis-Michel Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau: A politician and revolutionary who voted in favour of the king’s execution and was assassinated in 1793 shortly after casting his vote, becoming a symbol of revolutionary sacrifice.

(13) Paris Commune: Not to be confused with the better-known Paris Commune of 1871, this Commune was the governing body of Paris during the Revolution, responsible for administering the city and playing a key role in revolutionary events.

(14) Montagnard Convention: The left-wing faction of the National Convention, dominated by Jacobins, which held power during the Revolution’s most radical phase and implemented the Reign of Terror.

(15) Sorbonne: Founded in the 13th century by Robert de Sorbon as a theological college, the Sorbonne evolved into one of Europe’s most respected centres for higher learning, particularly known for theology, philosophy, and the liberal arts. It was closed during the Revolution due to anti-clerical reforms.

(16) Louis-Le-Grand: A prestigious secondary school in Paris, temporarily renamed École Égalité during the Revolution. Notable alumni include Maximilien Robespierre and Camille Desmoulins.

(17) Joseph Barra: A young soldier killed in 1793 during the War in the Vendée, whose death was used as revolutionary propaganda to inspire loyalty and martyrdom among French youth.

(18) Civil Constitution of the Clergy: A 1790 law that brought the Catholic Church in France under state control, requiring clergy to swear allegiance to the government. This split Catholics between “constitutional” and “refractory” priests, heightening religious tensions.

(19) Joseph Chalier: A revolutionary leader in Lyon who supported radical policies. He was executed in 1793 after attempting to enforce these policies, later becoming a martyr for the revolutionary cause.

#history#frev#french revolution#paris#marat#carnavalet#museum#robespierre#saint just#amateurvoltaire’s travel diary

244 notes

·

View notes

Text

No, Olympe de Gouges Was Not Executed for Being a Feminist

As @mathildeaquisexta and @robespapier already explained so well in this post, let’s be clear once and for all: Olympe de Gouges was not executed because she was a feminist, nor for any misogynistic reason.

She was executed under suspicion of modérantisme—a political stance that did not necessarily imply opposition to executions or support for clemency—and more crucially, under accusations of counter-revolutionary activity. In her writings, she advocated either a return to constitutional monarchy or the establishment of a federal republic. Given the intense internal and external civil war at the time, such views were considered dangerously destabilizing. The Montagnards, under mounting pressure, resorted to increasingly harsh measures—something that does not excuse their actions, many of which were indefensible, but places them in a broader revolutionary context.

Some sources—though I’ve yet to locate them again, so this should be taken cautiously—even suggest that she may have called for Robespierre’s death. In any case, she was far from the saintly figure some portray her as.

Did Olympe de Gouges deserve to die? Absolutely not. Was her execution condemnable, especially from a human standpoint? Yes. But from a legal perspective—however flawed the laws may have been—her writings were seen as criminal and therefore her trial was not, strictly speaking, unlawful.

Her feminism itself was full of contradictions. She opposed revolutionary women taking up arms, for instance. An interesting detail: historian Mathilde Larrère pointed out in a video that when de Gouges rewrote Article 12 of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen(La Déclaration des droits de l'homme et du citoyen) for her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen (Déclarations des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne), she significantly altered its meaning.

Here is the original Article 12: "The security of the rights of man and citizen requires public military forces: these forces are therefore instituted for the benefit of all, and not for the personal use of those to whom they are entrusted."

Now Olympe's version: "The guarantee of the rights of woman and citizen requires a major utility; this guarantee must be instituted for the advantage of all and for the particular benefit of those to whom it is entrusted."

Where other revolutionary women were requesting weapons—and rightly so, given that they were at war—de Gouges stood firmly against it. At times, I can’t help but wonder if she wasn’t somewhat disconnected from the reality on the ground.

Yes, it's necessary to condemn lynchings, murders, and other excesses of the Revolution. But we must also avoid the "black legend" narrative that demonizes figures like the Montagnards, the CSP of the year II, Hébertistes, or the Enragés, just as we must reject the "golden legend" that romanticizes the Revolution. Much of the Revolution’s progress was driven by violent struggle: the storming of the Bastille, the fall of the Tuileries (which finally removed Louis XVI—a serious threat to the nation and the revolution because of his betrayal), or even the uprisings of enslaved Black people in the colonies.

These were violent acts—but how else could centuries of brutal oppression be overthrown? Enslavers were never going to relinquish power simply because someone asked nicely. The system itself was inventive in its cruelty and designed to resist any path toward Black liberation.

And yet, Olympe de Gouges, despite being an abolitionist, condemned the Haitian revolt in 1792. In a striking and disturbing passage from her play L'Esclavage des Noirs ou l'Heureux Naufrage, she directly addresses the enslaved and says:

"It is to you, now, slaves, men of color, that I am going to speak; I may have undeniable rights to condemn your ferocity: cruel ones, by imitating the tyrants, you justify them. Most of your masters were humane and kind, and in your blind rage, you do not distinguish innocent victims from your persecutors.

Men were not born for chains, and yet you prove they are necessary. If overwhelming force is on your side, why unleash all the furies of your burning lands? Poison, iron, daggers, the invention of the most barbaric and atrocious tortures cost you nothing, they say. What cruelty! What inhumanity! Ah! How deeply you make those groan who sought to prepare, through tempered means, a gentler fate for you — a fate more worthy of envy than all those illusory advantages with which the authors of France’s and America’s calamities have misled you.

Tyranny will follow you, as crime clings to those perverse men. Nothing will ever bring harmony among you. Fear my prediction — you know whether it is founded on true and solid grounds. I speak my oracles based on reason and divine justice. I do not recant: I abhor your tyrants; your cruelties fill me with horror »

Frankly, this is appalling. To suggest that enslaved people—who had endured horrors that defy comprehension���were just as bad as their oppressors is a cruel and absurd false equivalence when we know all the horrors of the slavery system and even if there were deaths on the other side who were truly regrettable, it is clearly not comparable. And what “tyrants” is she referring to? At the time, there was no formal revolutionary government in place in Saint-Domingue. There was no “major force” on their side. At that point in time, slavery had not yet been abolished, and the arrival of Sonthonax — a proponent of the gradual abolition of slavery — marked a turning point. One of the key factors behind the push for abolition was the execution of Louis XVI, which led some white royalist planters to seriously consider turning Saint-Domingue over to the British. In this context, the text appears, in my view, somewhat disconnected from the historical and political realities of the time.

In short, this is a deeply misjudged and insulting passage. That said, she's far from the only historical figure with contradictory views on slavery—Brissot and even Robespierre had their own problematic moments.

To her credit, de Gouges was lucid in other respects. She opposed the war that Brissot advocated, aligning instead—whether consciously or not—with Danton, Robespierre, and Billaud-Varenne, who foresaw the catastrophe it would bring. According to historian Antoine Resche, she supported constitutional monarchy but rejected the property-based voting system (suffrage censitaire).

Still, Olympe de Gouges was not widely known among revolutionary women of her time. Her Déclaration des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne (Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen) had limited impact. The true revolutionary womens "stars" were Théroigne de Méricourt, Pauline Léon, Claire Lacombe, Sophie de Grouchy, Louise Reine Audu, Manon Roland, Louise de Kéralio, Simone Evrard, Albertine Marat, the Ferning sisters, Rosalie Jullien, Sophie Momoro (as Goddess of Reason), Jeanne Odo, and perhaps Marguerite David ( of the group of Enragés).

In fact, it’s likely that de Gouges knew of these women, but not necessarily the other way around. Even after her execution, I’ve found almost no evidence of posthumous recognition during the revolutionary period.

From Year III to IV, women like Sylvie Audouin, Thérésia Tallien, Marie-Anne Babeuf, Sophie Lapierre, and possibly Élisabeth Le Bon (widow of Joseph Le Bon) gained more visibility — though Thérésia and Babeuf were probably more famous than Audouin or Lapierre. Still, Olympe remained largely absent from the collective memory ( at least to my knowledge). So she wasn't completely unknown, but her importance wasn't as great as some people would have us believe.

According to Mathilde Larrère, Olympe de Gouges only emerged from oblivion thanks to feminist Benoîte Groult, who revived her memory and her declaration. This was a fantastic move—it's always good to recover lost revolutionary voices.

But ironically, her legacy has since been co-opted by people who hold a very dark view of the French Revolution, some even veering toward counter-revolutionary ideals—because, yes, de Gouges was a staunch monarchist. Even worse, some who now praise her aren’t feminists at all, but use her image dishonestly to discredit the Revolution as a whole.

And the tragic twist? The women who were famous during the Revolution—Louise-Reine Audu, the Ferning sisters, Sophie Momoro, Marguerite David, Jeanne Odo, Rosalie Jullien, Sylvie Audouin, Sophie Lapierre, Marie-Anne Babeuf, Elisabeth Le Bon, Louise de Kéralio—have largely disappeared from collective memory. Others have been demonized or reduced to caricatures: Pauline Léon, Claire Lacombe, Simone Evrard, Albertine Marat.

Once again, my point is not to demonize Olympe de Gouges, but to highlight the problem of turning her into the only legitimate feminist voice of the French Revolution, while erasing or vilifying all others just because they held different political views.

If people genuinely want to honor Olympe de Gouges, they should portray her in full:

Her strengths—her opposition to property-based voting, her fight for the rights of children born out of wedlock, her courage in speaking out, her revolutionary spirit, her willingness to denounce Louis XVI’s betrayal despite her monarchist leanings.

And her flaws—her rejection of women bearing arms, her naivety about nonviolent change, her harsh and misguided condemnation of enslaved people fighting for their freedom.

She was sincere in her convictions, passionate about justice, and undoubtedly brave. But she was also human, with contradictions and limits like any of us.

One day, I hope to see a real film that portrays all the women of the French Revolution—regardless of their political alignment—without distortion or demonization.

#frev#french revolution#olympe de gouges#feminism#women's rights#women in history#sexism#slavery#revolution

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

My dear American friends,

I know today is a day that might feel incredibly dark, given a fascist is once more crowned President of the United States. But I want you to remember that in the end fascism is always a sign of capitalism failing.

Back in the 1940s, when Nazi Germany fell, the mistake made - in which the US played a big role - was not only letting Capitalism stay in effect, but pushing for more capitalism.

Capitalism is a leftover to this day of the noble hierarchies, that started to be dismantled after the French Revolution. Certain nobles back in the day hedged the rather brilliant plan back in the day to push for capitalism and meritocracy, knowing fully well that they - with their ancient riches - could no fail in that system. They would still be nobles, just by another title. And those old nobles will cling to this power, until they are disposed off.

But please remember this wonderful quote by Ursula K. LeGuin.

We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable — but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings.

We already get rid of kings and the system of nobility. We can do it again.

And just on related news: Tomorrow, the 21st, is the 232nd Anniversary of the execution of the French King Louis XVI. Ending a system is possible.

#anti capitalism#anarchism#anti patriarchy#french revolution#ursula k. le guin#antifascism#punk#trump inauguration

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

I need the show to explain to me with apples why the fuck did Alucard care sm about Mizrak potentially dying????

Like Nocturne has shown throughout season 2 that Alucard often disregards humans to an extent now. 1st when he protested against Richter and Annette's idea of saving the humans from the vampires to cross the river 'faster' (even though they later stopped to witness Louis XVI's execution and Alucard stopped to comment on (at least) 1 of Da Vinci's paintings), then 2nd when he didn't even react to a human that tried to help him getting killed by the vampires he was fighting against, AND 3rd you can see him during the final battle not even trying to save any of the revolutionists he was fighting along side with

Then why, WHY did he look so horrified when Mizrak got critically wounded? Why did he run up to him until Olrox ran to them to hold Mizrak? Why did he care sm about a man he interacted once with????

Please tell me this isn't a main character syndrome, this can't be just bc the other humans I mentioned were just cannon fodder and Mizrak wasn't. There has to be an in-universe explanation pleaseee

#yami rambles#castlevania netflix#castlevania nocturne#alucard#adrian alucard tepes#adrian tepes#olrox#mizrak#castlevania mizrak

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soo, fun fact, Chevalier Charles was an actual person who executed King Louis XVI... Is Kaneshiro dropping some foreshadowing, or is this just a coincidence? So far, the only person who has a royal title attached to himself is Kaiser... Uhm...

#bllk#blue lock anime#blue lock manga#blue lock#charles chevalier#bllk charles#blue lock charles#michael kaiser

196 notes

·

View notes

Text

Élisabeth of France

Artist: Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755-1842)

Date: c. 1782

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: Palace of Versailles, Paris, France

Élisabeth of France

Élisabeth Philippe Marie Hélène of France (3 May 1764 – 10 May 1794), also known as Madame Élisabeth, was a French princess. She was the youngest child of Louis, Dauphin of France, and Duchess Maria Josepha of Saxony, and she was a sister of King Louis XVI. Élisabeth's father, the Dauphin, was the son and heir of King Louis XV and his popular wife, Queen Marie Leszczyńska. Élisabeth remained beside her brother and his family during the French Revolution, and she was executed during the Reign of Terror at the Place de la Revolution.

Regarded as a martyr by the Catholic Church, Élisabeth was declared a servant of God by Pope Pius XII.

#portrait#knee length#elizabeth of france#madame elizabeth#french princess#french royal family#french nobility#french history#heavy clouds#blue horizon#red skirt#grey drapery#costume#flowers#foliage#brimmed hat#painting#oil on canvas#fine art#oil painting#artwork#french culture#french art#elisabeth vigee le brun#french painter#european art#18th century painting#palace of versailles

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Parents in 1770s ireland were always going "I am going to send my child to Radical School" and then acting shocked when their child grew up to be the only person in the friend group who wasn't sad about the execution of louis xvi

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

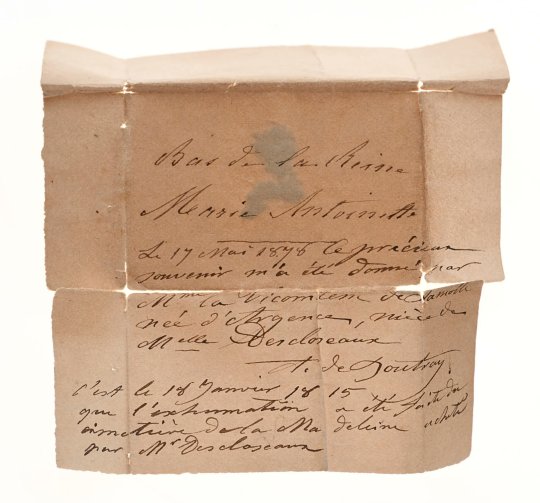

A fragment of a stocking said to have been worn by Marie Antoinette. The inscription notes it was given in 1878 by someone in the Descloseaux family. Louis Descloseaux had purchased the Madeleine cemetery, where Louis XVI and MA's bodies were said to be buried.

During the Restoration, Descloseaux gave the information about the location of the bodies to Louis XVIII. The bodies, or what remained of them due to the use of quicklime, were exhumed. Among the remains in what was said to be the Queen's grave was a stocking and elastic garter.

If the fragment is legitimate, it would presumably be from a stocking she wore to her execution.

Being sold via Osenat.

228 notes

·

View notes