#in the comics medium. the sequential art medium.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

also as a new spideyhead(??) i have much to learn in the way of spideydrawing. namely. the lines. the weblines. the costume weblines. mister ditko how did you do it.

#spidey#how did you design a design that rocks so hard it continues to be used decades later virtually unchanged#but also how did you then keep drawing it every time after.#in the comics medium. the sequential art medium.#the medium of drawing the same thing many times over second only to animation.#though speaking of animation i notice the 60s cartoon elected for the I Do Not See It approach to All That and that is Valid.#i wonder how the other cartoons handle it...#i grew up on One (1) VHS of An (An) spider-man cartoon which i am not even sure of the decade of (90s?)#but hell if i paid attention to details like that.#and the only other spideytoon i done seen is ultimate spider-man which i also did not notice such details of#because i was too busy noticing the details of how that show's art style was. kind of ugly to me.#<- harsh?? but c'est la personal taste.#i just hated peter's haircut and the eyes and the fuckin. chibis.#otherwise cromulent action cartoon style.

0 notes

Note

Your comics are so well done !! I adore the compositions, the linework and colors :D The way you approach compositions is so fun like the panels tripping over each other when Raph stumbles or the way the panel is shaped like the tunnel they’re walking through. I really look forward to seeing more of your work both in this fanwork and any future comics you work on :]

I have fun with the page layouts, composition, and panel boxes ((o(^∇^)o))

TBH one of my favourite pastimes is staring at comics made by more seasoned professional comic artists; it's so interesting to see how they layout their pages and all the fun ways the panel boxes themselves can be used as an addition to the art rather than just what contains it.

Stopping myself before I start rambling. It's so nice knowing there are folks who enjoy and notice things like that!!! Haha thank you!!

#asks#art related asks#will be thinking about this ask for 100 years#i am a nerd about comics as a medium#aaaa another cool thing is the way panels & page layout varies across artists and comic types#long scroll webcomic vs 4 panel vs newspaper strip vs european vs manga vs american vs non bordered sequential image storytelling#*explodes*#every artist puts the puzzle pieces together in different ways#and some forgo them completely#comics are so cool

89 notes

·

View notes

Note

how do you plan the panel layouts for your comics? i always get stuck and it feels cramped or unsatisfying

okay so i went to college for 2 whole semesters and one of the only art classes i took (and definitely the only one i retained much from) was my sequential art & comics class. so i'm gonna try to explain my process in so many words, but there's a LOT of stuff that goes into a successful comic and i'm by no means a professional. i can however throw some tips and tricks and some recommended reading your way (another longpost ahead!)

first, know what you want to do. know where your comic starts and ends. if you find any joy in writing scripts, you can also do that, but i'm not the best at writing with no visual aide so i usually script while i thumbnail, but always make sure you've got a concept and a goal.

next, start thumbnailing. my initial thumbnails usually look like this:

(incidentally, my storyboard thumbnails look a lot like this, too)

there's no real structure, and i'm just noodling my way from the top left of the page to the bottom right. if you've got what you want from your comic in mind, this part can sometimes just pour out of you. i feel a very strong attachment to these characters and the situations i put them in, so that definitely has to do with how smoothly this part goes. draw the panels as small and as detail-free as possible. i usually don't do speech bubbles, and instead treat it like a storyboard, writing my rough script under the panels as i go.

once you're satisfied with the way your story is coming together, THEN you start laying your panels out. this part looks like this when i do it:

(these are actually from a gfalls comic i never cared to finish from like. five months ago but who's counting?)

honestly, it's best to do this as small as you can possibly get it, to really get your head out of the "but i have to fit all the panels exactly as i drew them on the page" funk. remember that, at least if you're writing the comic in english or other languages read in the same direction, that you're trying to lead the reader's eye from top to bottom and left to right. this is really hard to keep track of, and i still make mistakes and flub up the readability all the time. like here:

the panel layout should be reversed here. the panels in the top left and bottom right should be smaller than the other two, so the gutters would actually guide you to read it left to right instead of top to bottom, but laziness and initial drawing blindness struck me and i never fixed it.

once you have a layout that makes sense to you, it's as simple as blowing your thumbnails up to comic-size and going over your very rough sketches with your final clean panels & inks, or, if you're doing it traditionally, re-sketching your page on your big bristol board after doing some measuring to see where your panels should actually be.

there are other rules to keep in mind when you're in the thumbnailing phase of your comic, like the 180-degree rule (something that carries from film to animation to comics to, really, any form of sequential art), which is easiest to explain with a little diagram:

keeping this in mind really helps with readability. you can do a bunch of things with your angles, you can even omit the other character, but keeping them on the side of the frame you establish them on is very helpful. this is mainly for dialogue, but it does also help if you want to display one character walking in one specific direction, or if you want a fight scene to read as well as possible, etc.

and, if you look at your comic sketch now and think, hey, this looks great, this is so clear and easy to read, i highly recommend stepping away for a few hours to look at it again, or, if you're impatient like me, sending it to a friend. you're also totally welcome to send it to me, if you just need someone to tell you whether your comic is easily readable.

to learn more about drawing comics, i recommend two things. one, read some comics. by professionals in the industry, ideally, though there are many many competent and incredibly detailed comics by independent creators out there. people in the industry will (MOST of the time) be held to slightly higher standards of readability than the average independent artist, and the workflow for professional comics involves several people at once reading and reviewing and revising what's made so that it'll be digestible to the average audience.

two, i recommend getting your hands on a copy of "understanding comics" by scott mccloud. love this book. lots of comic artists love this book. it's fun and informative and packed full of tips, while also being a comic, which makes it even more fun to read. mccloud goes into a lot of detail on stuff i didn't mention, from the gutters between panels to lettering to working with other artists and writers and finding an art style that fits the story you want to tell. great stuff. go to the library, check it out. you won't regret it.

#ask#myart#wander over yonder#comics#rambling#comics are HARD man it's tough stuff to learn and even tougher to put onto paper#but when you learn about comics you also pick up lots of stuff for animation and writing and even film#because visual art is all connected. peace and love. but comics are one of the most involved mediums of storytelling out there#also quite possibly The best. because you get to read through it as fast as you want#but you can also hang back and look at the panels forever and really think about what makes them work as well as they do.#live laugh love sequential art

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

whatever man this art shit is easy

#creative#visual medium#(sequential)#notes app art#so ready for next year's bad comic day#🝐#fenn original#🝐art?

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

ON BLOOD MAGIC

#BOYYYY IS THIS THING OLD#i remember very vividly the dream that inspired this comic and i started working on it very feverishly during work on my notesapp#so in the process there's like 3 different textures happening bc like 2 different drawing programs plus trad#it feels like a very vulnerable comic and thats probably bc i let it collect dust in my drafts for what im sure is almost a year#but the layout of the comic is verypretty and im still very proud of it so#i can cope with my own cringe#mixed medium#clip studio paint#comic art#short comic#mini comic#digital art#queer artist#latino artist#artists on tumblr#traditional art#traditional sketch#comic#sequential#125

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comics are hard sometimes

I was giving some feedback to another comics artist, and starting writing out a whole thing about how making visual communication is difficult and deeply rooted in both cultural norms and norms of the medium, but then I realized that was way more off-topic and decided to write out my thoughts here.

One of the people I like to run my art by is my dad. This is not because he's particularly well versed as an art critic. He is a complex human with fascinating tastes and a lot to say about a lot of media in a lot of contexts, but in visual art he tends towards the representative and simple. He is not a comics reader. He is almost certainly allistic, while I am not. He is a nerd, but not a pop-culture nerd.

So if he's not the kind of person who would typically interact with the sort of visual language I rely on all the time, why is he so helpful?

The reason I often run pages by him is *because* he is not a comics reader. He doesn't have the shared mental icon library that a lot people who have been reading comics for a long time have. He is as close as possible to what in a scientific study might be called treatment naive, where the treatment is comics.

My dad is my control group, because I can show pages to friends who think similarly and have read a lot of the same stuff and who all have similar shorthands, even if we don't know it, in how we see and process comics, and they'll see and understand in a similar way that I see and understand, and don't see the areas where maybe I rely too much on a visual shorthand, where I've used the conventions of the medium or genre in a way that excludes people who are only just starting to read modern comics. He has questions, and critiques, (some of which I decide to address and others I don't), that might not occur to others.

Comics- art in general, really- is often an exercise in trying to predict how others will interpret what you have made. With comics and visual art, there is a lot more automatic processing compared to, for example, prose, just due to how vision works. In parsing prose, you can say "A broken table"; but in a visual medium, a broken table is full of angles not normally seen, and perspectives that are hard to parse if we weren't expecting it.

This is a bit of a ramble, but the main point I am getting to is: Sometimes what I think is obvious on a page really isn't, and the kind of feedback that helps me refine my art is often from people who don't know what they're looking at.

#comics#comic philosophy#art critique#seriously my dad is great but does not know the Language of the Comic#understanding comics#thoughts on comics#sequential storytelling#sequential art#Show your shit to others without context#you have the context and can decide if the critique is valid but it really helps even if it feels bad when they say they don't get it#also sometimes you make stuff for people who are neck deep in the medium along with you and that's fine too#but just consider the treatment naive#julianova44

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

the amount of fan comics in this fandom is so evil because very regularly im like “omg i want to make a fan comic” as if i don’t already have two fics im writing telling both of the longform stories i have in my brain and also i literally do have a fancomic. called flat facts friday. that i am kind of very slow at updating despite the fact that it has a regular deadline in the title. i haven’t wanted to make a longform fancomic since i was 13/14 making a totally not self insert undertale comic it’s been like eight years

#insert talk tag here#on one hand i just don��t feel like i’m built for comics ive chosen my sequential medium and i’ll lay in it#but on the other hand my confidence in my art is a lot stronger to the point where i wouldn’t feel like i need to color and shade#it to reach a baseline level of visual interest. being a teenager is crazy you’ll just decide to color n shade that shit#and then ur font choice is abysmal

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

comics as an art form make me insane. they’re so difficult to do well. there’s so many different ways to make sequential art work and most of them are deeply unintuitive. onomatopoeia that feels completely ridiculous to put down often reads seamlessly. panels on a page become a fractally nested image composition challenge that’s only possible to lose because if you do a good job no one will notice. you have to direct the readers’ eyes on a specific path across the page but also account for the fact that they won’t follow it. comic time isn’t linear. if the order of events isn’t crystal clear the story becomes incomprehensible. sometimes you need to do this on purpose. all this for a medium almost universally considered less effective than animation and less respectable than plain text. even its own name doesn’t take it seriously

#don’t mind me just chewing on drywall#some of the absolute best comics don’t look remotely impressive until you try to make one yourself#and some absolutely beautiful panel layouts and art combine to make a stunning visual that barely manages to get any meaning across#you have to emulate cinematography by cultural necessity at this point#but if you lean too hard in that direction your comics just become Worse Movies#there’s barely any standard practices for anything because people are just barely starting to look at comics seriously#mumbling

31K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Creator's Guide to Comics Devices is OPEN!!! comicsdevices.com

An online library of visual-narrative devices that are used in the medium of comics and other sequential art.

Happy Halloween! I'm really excited to be finally launching* what is maybe one of my most ambitious, largest work yet. This online library is the next phase of a research project that began in May 2020, when I first mused on how comics as a field doesn't have a resource that catalogues devices used in the medium. Like, theatre has devices, so does literature, and film! So why shouldn't comics? I always had an interest in comics studies and analysis. I love reading, making and thinking comics. However most of my knowledge was intuitive - I learned comics from osmosis and experience. This is true for many of my peers. Speaking about comics as a creator is hard, because we don't have a robust system of language. When we had to speak, many of us tend to reach for the language developed for film by film practitioners. If there is language specific to comics, it's either scattered in multiple blogs or hidden away in academic journals. The Comics Devices library is meant to aggregate everything and everybody into a single hub! After exploring some multiple resources, alongside some original, independent research, here is the first edition! * The Comics Devices project is still a work-in-progress! It's not final, nor will it ever be. This is why I am seeking contributors to help build this library. Translations, comics examples, etc. There is a lot of work to do! If you are interested, reply to this post or submit an expression of interest on this page. Have fun everyone!! (Now time for me to melt x_x)

#webcomics#comics#comics devices#resources#good god there is still a lot to clean up even in this public state fhskjfhsd#anyway hope yall enjoy reading through this!!#also please help me build up the library lol

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

itty bitty comic that took me WAYYY longer than i expected :'] i was trying to test the viability of this medium for sequential art and the answer is Yes it kind of works but Only if you have both a ton of patience and time on your hands. i think this turned out kinda swag for a first attempt!

anyways this was going to be the beginning of a short story but now i've moved and. no longer live in the forest anymore kjfdksj so might have to rethink it slightly

#hopefully you can tell... what is going on..... i couldn't employ different panel shapes or anything obvs. and the script is weirdd#hermitcraft#grian#goodtimeswithscar#desert duo#this was EXTREMELY RUSHED. like i was at this creek the day before my flight. hence why some of the angles are weird and the-#-dialogue is borderline nonsensical >_<. i'm trying to be positive though! it's definitely good for a first attempt!#hermitbugs adventures#aurie's art

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey Look At This... Comic? The Timekeepers of Eternity

Motion comics were a bit of a bust huh? Oh, there's examples here and there, especially when talking about independent weirdo hypercomics, of works that incorporated motion convincingly and compellingly, but most corporate offerings amounted to taking still images and having their panels slam across the screen, pile on top of each other arbitrarily, or fade into view one at a time accompanying voice acted lines--the worst of film, comics, and audiobooks combined. Easy enough to explain: paying people who work exclusively in print comics to do (or adapt) a "motion comic" just isn't going to result in much latitude or incentive for bold formal experimentation, nor does it play to the training of the artists handed the task.

On the other side, there's the real structure perverts, mad scientists of comics. They face the same problem as every other avant garde artist: how do you get paid? Where does your audience come from? Criticism for comics in general is underdeveloped; criticism for webcomics and hypercomics even more so. Launching what by necessity must be a more fine arts oriented career in what's still widely understood to be mass market commodities seems daunting, as does coaxing a mass audience out of its comfort zone.

It makes some sense, given all that, that one of the best showcases of the potential of motion comics would come not out of comics itself but the weird and heady film fan edit scene. Blessed with an abundance of material to work with (especially in the cases of franchises, miniseries, or films with extensive cut content or rereleased versions) fan editors have a latitude to screw around without having to produce a bunch of raw footage or drawings themselves (though, the nature of enthusiast projects does inspire people to do things like, say, redo all the special effects from Alien3).

There's certainly a mountain of frames to work with in the Langoliers miniseries from 1995. Probably an overabundance, actually. That's great for Aristotelis Maragkos, though, whose recut of the miniseries into the tight hour long experience The Timekeepers of Eternity needs a lot of raw matter.

I actually mean that literally: Timekeepers is a film produced by physically printing out photocopy versions of the miniseries' frames, manually altering them, re-photographing them, and re-cutting the audio to fit the new narrative. Its runtime is partially achieved by layering scenes onto each other, so actions happen in parallel, or characters expound on a subject while a pan of the environment fills in detail. Sometimes, astonishingly, footage of cloudy skies becomes an abstract 2001 style gradient as characters get lost in their own thoughts, or staring eyes from a close up rip eerily into a shot of a still landscape. What another compressing edit might discard, Maragkos collages back into the frame in unexpected ways.

This could be just a fun gimmick or novelty, and can occasionally come across as just a fun flourish on an otherwise kind of awkwardly acted and plotted original. But just as often Maragkos finds incredible possibilities in the strange hybrid medium. There's a shot early on of Toomey, the murderous time-obsessed business boy going through a breakdown, that blew my mind and immediately convinced me of the film's vision. Toomey, who pitched a tantrum when the plane failed to reach his board meeting in Boston, gets his nose nearly broken by another passenger. Outmatched, he retreats, resentfully, turning and walking back through the plane. As he does so, the film tears, creating a multiframe of instances of Toomey looking back, petulant tears in his eyes.

What happens when you turn a film into a comic in this way? In a static comic, splitting up this action into a series of "prolonger" panels helps clarify small movements and draw out the action, but in a film that's not really necessary. we can just watch that sequentially in time, like we do in real life. What else does this breakdown do in a comic? It can heighten a moment, suggest a psychological intensity, a kind of distending of time or hyperreality. Isn't that exactly what's happening for Toomey? He retreats, literally--we watch him do it. Yet he remains in place simultaneously, staring, seething. He might physically go, but psychologically he is still rooted in place, boiling over with anger at his rough treatment.

Shortly after this scene, we discover the textual rationale for Maragkos's bizarre aesthetic endeavor: Toomey has a bizarre tick of his own, am almost eroticized need to stim by tearing and shredding paper. As he sits and stews after another confrontation with the rest of the passengers, he tears at a magazine, and the screen tears too, layers of the frame peeling back to reveal other elements of the scene, so that his tearing becomes the ubiquitous context for the other characters talking about him and around him.

I have a lot more to say about this one so I'll cut the review short here and you can read the rest on my full blog. You can also read the rest of my Hey Look At This Comic reviews on tumblr, and support me on Patreon.

#Hey Look At This Comic#comics#hypercomics#fan edit#the langoliers#stephen king#the timekeepers of eternity#horror#horror recs#horror review

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

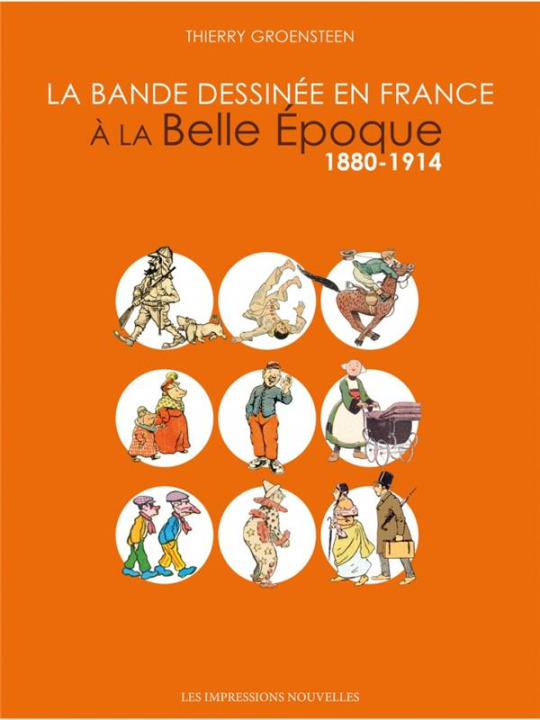

Let's take a look at the ninth art...

Given Asterix and Obelix has been getting popular again, I thought I'd do something I wanted to quickly write down for a long time - some posts to introduce those unfamiliar with to the world of... BD!

"BD"? Bande-dessinée. The French word we use for what Americans call "comic books" or "comics" or "graphic novels". Technically speaking, BD can cover the entirety of European comics production, but traditionally people refer to the "Franco-Belgian BD", "la BD franco-belge", as the heart of the European production was formed out of the industrial duo of France and Belgium.

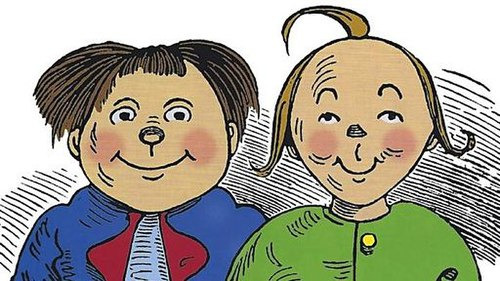

Now, why would you or I use this obscure non-English term "BD" or "bande-dessinée"? Why not just say "European comics" or "French comic book"? Well... Why do you use "manga" and not "Japanese comic"? That's the same thing. Bande-dessinée works a lot like the American comics yes, and in fact, when I took a class at university about the history of BD, the teacher kept referring the theories of Will Eisner and Scott McCloud - BD, like comic books, are two manifestations of the "sequential art" as a whole... However, BD has a very different publishing process, a different historical evolution, a different social reception and cultural context than comics, and so it earns the right to have a specific denomination to separate it from American comics, the same way Japanese mangas are called "mangas". In fact, manga, comics and BD form the holy trinity of the sequential art, the three main manifestations of this specific medium - on one side Batman, Calvin and Hobbes, the Marvel comics ; on the other One Piece or Akira, and in the middle Tintin and Asterix and others...

BD received various other names, from the derogatory to the glorifying.

A derogatory name? "Petits mickeys" (small mickeys), alternatively spelled "petits miquets" (small miquets, a francization of the term apparently from Pascal Oury). This term, from the 60s and 70s, was used to refer to BDs under the angle of low-quality, of "popular", "low" works. "To draw little mickeys, to read little mickeys, to make little mickeys". The term was also used, in a lovingly ironic way, out of self-mockery, by various BD creators such as Goscinny or Gotlib (today you can hear people say this term is tied to the Pilote and Fluide Glacial generations, 60s-80s). Some wonder if it isn't Sempé who made the term "mainstream", through humoristic drawings he made showing how people asked him if he was the one draing "little mickeys". Of course, this is an obvious reference to Mickey, the character from Disney, but it isn't just some sort of "Americanization" thing... The reason Mickey became associated with BD was due to "Le Journal de Mickey" (a famous French comic-magazine), which has been in France one of the historical outlets for introducing and developing the BD in France. But as a result, it led to the perception of BDs as simple stories, as childish things aimed at a young audience, and at "Mickey-adjacent" (and thus Disney-adjacent) products.

A glorifying term? Le neuvième art, "the ninth art". This famous and common denomination (which ranks the BD production to the rank of "art") is based, not on the "seven arts" of the Middle-Ages, but rather on a different system of art classification... You see, in the 19th century, a certain "art hierarchy" was popularized (by Hegel). It deemed that there were five main arts, which in rank of importance were architecture, sculpture, painting, music and poetry. However, after Hegel's classification became popular many authors and thinkers started to add their own arts - in the 1920s, Ricciotti Canudo notably added the "sixth art" (dance) and the "seventh art" (cinema). Though not everybody agreed on what was what - for example, while today the sixth art is "dance", for quite some times it was "photography". And while Canudo added the sixth and seventh art, he had his own concept of the five arts - for him it was poetry, music, theater, plastic arts and eloquence/rhetoric.

Anyway, BD soon became the "ninth art". Morris (creator of the "Lucky Luke" series) and Pierre Vankeer wanted to officially call BD the "eighth art", but they discovered the term was already taken - Roger Clausse used it for radio in the 1940s, but it quickly became a common term for television as a whole and englobed within itself photography... So, Morris-Vankeer chose the "ninth" art for BD and, in a strange coincidence, on the very SAME year Morris-Vankeer published their denomination of "ninth art" (1964), Claude Beylie published his own article deemed BD the "ninth art". (And also, little historical trivia, the term existed by the 1920s but it was to designate gastronomy, and it never took off).

There is also quite a big debate over whether BD should be considered literature or not. It is primarily a narrative with prominent illustrations? Or is it primarily a visual art with some narrative stuck to it? What is more important, the drawing or the text? Is it closer to books or to paintings? Do we focus on the visual logic and the aesthetic, or the storytelling devices? It doesn't help that BDs come in a wide variety, from products very thick and heavy with text, to BDs without any text. From Boulet to Edgar P. Jacobs, from Les Cités Obscures to Blake et Mortimer...

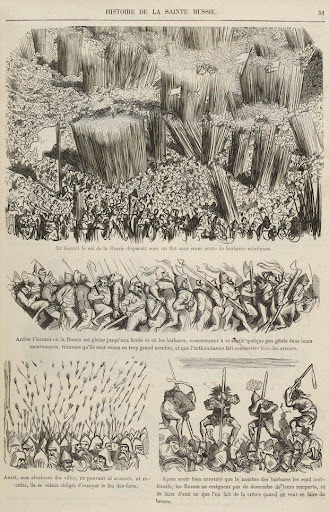

Without going back to the Egyptians and their hieroglyphs, the class I took about the history of BD did point out how the roots of the "sequential art" in France could go back as far as the stained glass of churches, and the very famous Bayeux tapestry.

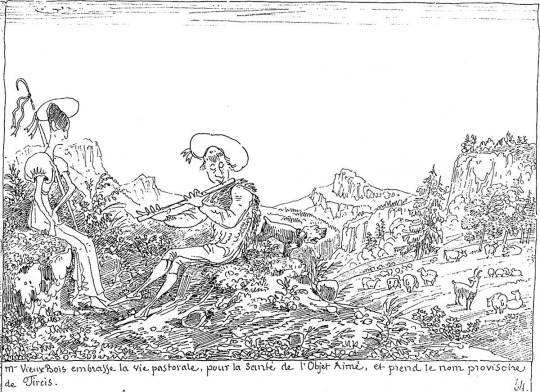

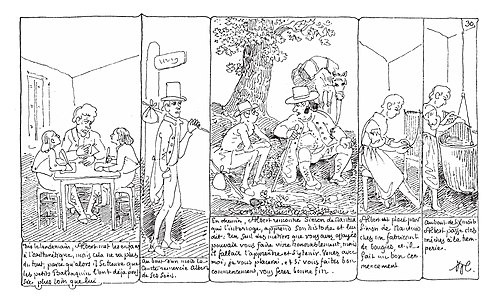

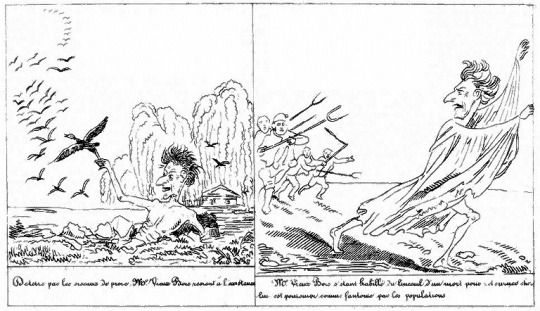

But the story of BD really begins with Rodolphe Töpffer, the man who is thought as the inventor of BD as a whole. You might know of him if you looked into the history of comics books because he is also thought of as the grandfather of American comics. What he wanted to create, first and foremost, was what he called "littérature en estampes" (literature in prints, literature by engravings). He was coming from the world of traditional books and novel-publishing, and thus had a very literary approach to it all. He wanted a form of literature where text and image would co-exist as equals, united for satirical and humoristic purposes. Because that was one of the main features of his work - to have caricatural characters, with exaggerated features, placed within comical situations.

With Töpffer, we find a true "balance of the sequential art". Because the images are clearly dependant and "submissive" to the text, in terms of narration and storytelling, but in return the visual has a much larger part on the page and is what catches the eye immediately. As a result, we have a proto-comic which relies heavily on the text, but where the drawing is what makes it interesting in the first place - and the visuals are needed to appreciate what the text is saying - and these texts usually explore the logic of mismatching, discordance, and absurdity.

Töpffer's work spread throughout Europe, and even reached the USA... And yet never gained any fame. It was not a huge success, it was never a best-seller, in fact it sold in small quantities and limited editions. And yet, it still had a big influence over the various illustrators and cartoonists of the time, and gained a small celebrity in the world of caricatures. But for Töpffer to REALLY become famous and a public figure, we would have to wait for when people started studying the history of BDs and comics...

And what Töpffer changed, through his work, was the idea of these doodles and cartoons existing on their own. Given the development of comics always deeply relied on the developments of the printing industry, they rarely could exist "alone" - unlike text, printing comics required more machines, more supplies, more technique, more effort, and so they usually appeared as caricatures within daily or weekly newspapers, or as comic strips to illustrate a text, they appeared within places of recurring, regular publications that were however not their "own". The BD industry grew out of this logic of recurring, repetitive publications, and still kept a format of "serial". But Töpffer published his little comics on their own, within their own books, without anything else but them - they were sold for themselves. And that's how it changed things.

The BD also primarily began as a form of... "degraded literature", so to speak. It was seen as a storytelling form perfect for almost-analphabetical people and for people with reading difficulties - first of all being children. The BD fed from this concept developed in the 19th century of "youth-literature for young readers", this idea that children could have and deserved their own books separate from the readings of their parents (Jules Vernes notably played a big role in creating this "literature for children" in France). This, tied to how crude, fast-made and easy-to-reproduce the BD drawings were at the time, resulted in a general perception of BD as a form of "futility". BD was there for humoristic satires, funny caricatures, children publications. It can be compared to how the "mangas" were originally drawings of a "low", "mundane" daily-life, opposed to the "high" and "real" art of drawing landscapes.

And this initial "futility" explains a LOT about the history of BD and how it evolved. The first step of the BD history was to prove its "interest" and its "utility", by becoming a "useful" thing, by turning into a tool of pedagogy or a "good" form of entertainment. And once the BD became a legitimate, mainstream, mass-produced "classic" thing, then came a second era of counter-culture, where BD became more experimental and more mature, reaching out for an adult audience.

The "periodical" publication of BDs by "chapters" or "issues" was not truly preserved. Unlike American comics and Japanese manga, where the serial chapter-publication or the periodic-issues release is still a foundation of the industry, the BD industry ditched it all and relies rather on the publication of full "volumes" or complete "collections", as a full book with a solid cover. Before it is true that the income of BD creators came from the "perodics", with their work only being bound in a single volume, a "hardcover", as a "bonus" or a "reward" that confirmed the success of the series - but today BD relies almost exclusively on the publication of full volumes.

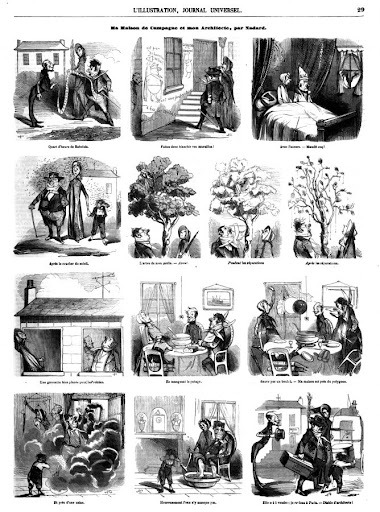

After Töpffer, the "littérature dessinée" (drawn literature) affirmed itself more and more, through satirical caricatures and humoristic tales. It never became the main production of artists - they were primarily illustrators or photographs, and they only did proto-BD as an aside. You had Cham, who took a lot after Töpffer, you had Nadar, who caricatured the mid-19th century politics, you have Gustave Doré too, yes THE Gustave Doré...

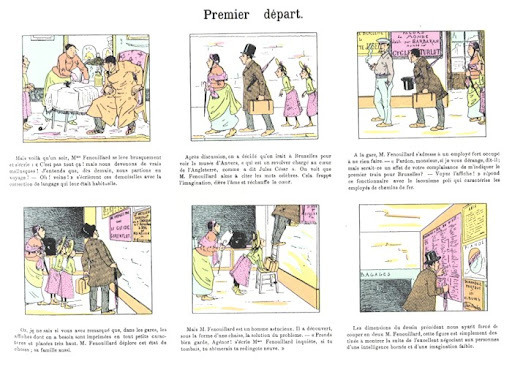

But the next big turn, the one that changed the "generic humoristic stories" into a "specific illustrated literature for children" was "La Famille Fenouillard" by Christophe, considered one of the first real BD of France (1889-1893). And again, we find here a specific balance between text and image. You have a LOT of text, that is a big dependance on the text - it is there that all the story takes place... But the drawings meanwhile are very attracting, very insisting, because they are incomplete scenes and visual enigmas that encourage the reader to check what they are about. The image attracts the gaze, creates the curiosity, the wonder, creates the question, whereas the text offers the answer. We are still in quite simple, not complex stories, but they play a lot on dichotomy - for example the drawings offering joyfull, happy, positive situations, that get more shady, more dubious if not dangerous once you add the text to them.

While I speak a lot of France, Germany has its own things going on aside - most notably, it developed what would become a very common genre in European BD, the "petits garnements" genre. Stories of brats, mischievious boys and little devils - such as the classic "Max und Moritz" (1865). This resulted in a wide fashion of duos or trios of prankster-heroes, that would create a lasting associated in culture between "childhood, youth" and "transgression, disobedience, trick". But here, we are closer to an illustrated tale rather than a "true" comic.

For more about the history of BD, see you in the next post...

#let's explore the ninth art#ninth art#bd#bande-dessinée#bande dessinée#comic books#comics#history of comics#history of BD#french history#france#french comics

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyway, comics pacing, narrative pacing and the fundamental constraints of any medium—

i don't really read comics any more (long story), unless it's something i can buy in trade paperback (and part of that is, honestly, getting burned once too often on webcomics not made by Evan Dahm either never finishing, getting super weird or just kinda fizzling out) and mostly i don't read Big Two comics any more. theoretically, i'd like to go back and re-read All-Star Superman and whatever, but the effort involved in learning about how all the eras are divided up and what's a reboot and what's not and what's worth reading is currently a little beyond me. one day.

so mostly when i read print comics, it's indie stuff or IDW (who aren't indie-indie, you know?)

and those have a meaningfully different pacing structure to something like DC's The Flintstones. it's hard to account for in any sensible way, and it's almost certainly something to do with The Flintstones being a limited run series of only 12 issues, but it's very interesting to see how much you can pack into a handful of pages if you're at liberty to convey "background" information without necessarily shoving it into the foreground with a big flashing neon sign of RELEVANT BACKGROUND INFORMATION like you have to do in prose fiction.

no seriously, like.

i've thought a lot about this (part of the long story, involving aspirations prior to my hands becoming unreliable) — sequential art narratives have a massive advantage in that it's easy to make a stripped down just-the-important-beats story structure feel rounded out and ground it in context and even overlap a side-story going on in the background. in the literal background of the panels. you can't really do that in prose. you can sorta-kinda come close, but it'll likely be obvious you're doing something weird and arcane to cram more things into the narrative space. it won't be something that's just a part of how the medium works.

which is really, really interesting. the trade-off is, of course, the same as with motion pictures: narration, telling, interiority (which requires telling) are a bugger to do in a visual medium without needing to employ techniques that scream HERE'S THE INTERIORITY AND INTROSPECTION SECTIONS I WORKED VERY HARD ON THEM.

the answer to that is of course visual novels, but you know what, fuck learning more programming than necessary. and i can't draw anyway.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

#creative#workposting on the clock#furry#i can and should be doing these dumb little comics with my sona#cats are just like negative effort when im drawing anthro#so i default to it. but why would i be a cat. im not a cat lol#maybe if i make more i will#notes app art#visual medium#(sequential)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thing that's been nagging me: why do Americans think of ourselves as not being a literary or artistic culture? (Compared to, say, the popular image of the French.) We put a lot of ENTIRE MEDIUMS on the map (hip-hop, sequential art) and we've made incredible contributions to everything short of really culturally specific stuff like kabuki theatre. (Even among really culturally specific stuff, sometimes: I used to be in a taiko drum group and modern taiko drumming was influenced by jazz.) (Man, the Japanese are crazy about jazz. You're welcome.)

Aside from the fact that most of what I mentioned is considered either "low art" (thank you to comic book content laws for ruining THE ENTIRE FUCKING MEDIUM and condemning it to the "stuff for kids and immature adults" ghetto in the popular imagination) (this is changing) (slowly) or associated with the world's least favorite race (God forbid we take anything Black people do seriously), we've always had heavy hitters who work in a more prestigious medium, like playwrights, Criterion Collection-worthy film directors, and authors. (We will argue over whether this is because of America's unnerving cultural reach or genuine quality at a later date.)

There's probably some more subtle historical reason (if you have a degree in this topic, reblog and tell me) like America not being a stop on the Grand Tour or whatever - I bet the old-timey European conception of which countries are artistic and which are colonies to plunder has more to do with it than I think - but I think it has something to do with how little we respect artists. I volunteer with Ukrainian refugees and the fact that I've published some writing is a Big Deal to the people I've mentioned it to. Like, genuine admiration and "ooh I've never met a whole writer before", I'm not missing some form of sarcasm here. (I think.) I lightheartedly said to one that I don't mention writing poetry often because it makes me look like a pretentious asshole and she couldn't wrap her head around it. (Meanwhile, I don't think I've ever once mentioned my work on Reddit without someone making fun of me in the replies. Demographics of that site are about half American, so presumably at least half of the people making fun of me are Yanks.) We can't even tolerate people playing guitars at parties without people going "Look at that pretentious prick showing off" and yes, not being able to stand party guitarists *is* culturally specific. Get a bunch of Slavs together and *somebody* is pulling out a guitar.

And now I'm wondering why that is, and I'm gonna look towards the couple of semesters during which I studied for an archaeology/anthropology degree for an answer.

In anthropology, there's a general idea that the easier an environment is to live in, the more time people have to develop a complex cosmology and make advances in their art. There's an argument to be had here over what counts as complexity or "advanced" art, but you're going to have to bear with me here for a minute. I think America is just a tougher place to live than most of the "artistic" countries, historically and up to the present - not because of harsh natural environments, although white people's stubborn insistence on doing stuff like farming the European way sure *made* them harsh according to a settler POV, but it's largely due to pressures from religion and capitalism - so we developed values that helped us under conditions like the industrial revolution, forming dust bowls in our agrarian regions, and being surrounded by fucking Calvinists.

(It was not exactly fun to be like an English guy during the industrial revolution either, to the extent that the north of that country is STILL underrepresented in the arts, but England had a strong enough gentry that there were always people there to sit around writing poetry. America's gentry, in the sense of people who are wealthy from sitting around as part of a rich family, is a way more recent thing. Andrew Carnegie started out a dirt poor Scottish immigrant, Rockefeller himself began his career as a bookkeeper's assistant, Sam Walton grew up on a failing farm...etc.) (Ukraine's always been a little rough too, but there a lot of reasons behind why they value artistic expression to a greater degree that I won't go into just now, especially because I'm not tooooo familiar with Ukraine's artistic culture. Suffice it to say that much of it's because it's been a firm part of asserting and preserving a uniquely Ukrainian identity, to the extent that there's a famous writer whose pen name translates into "Lesya the Ukrainian." I imagine Soviet influence is a factor there too - art was taken deathly seriously in the USSR as a tool for either social advancement or social discord and "writer" was like a wholeass job. They literally had a union. The US didn't have pressures like that to make up for the "harsh environment.")

So, it's interesting to think about and I want to hear what other people have to say.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

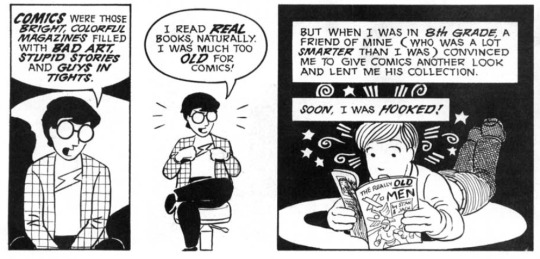

A Light Take on Understanding Comics, Part 1

All right, I'm going to do something dangerous and write one post that promises eight more to come. It's been a while since I reread Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics, a groundbreaking nonfiction comic on the techniques, theory, and potential of comics as a medium. It was first published in 1993, and it's aged... interestingly, but going back through it is giving me a lot of thoughts. Specifically, thoughts about The Power Fantasy, the comic that's been occupying 99% of my brain for four months now. So I'm going to (try and) do a post for each chapter of UC, write about what I think McCloud got right and wrong, and apply that to TPF.

Chapter One is about "What is the definition of comics?" but more specifically, it's McCloud being very clear that comics can be so much more than just the (direct quote) "crude, poorly-drawn, semiliterate, cheap, disposable kiddie fare" that they usually were. Comics can be manga, or comic strips, or graphic novels, or any number of other things, McCloud tells us! There's precedents for comics in Ancient Egyptian wall art, medieval stained glass, all kinds of things! Comics is a medium, not a single genre! It's not just all superheroes!

...and look, this is what I mean by UC having aged interestingly. I want to remind everyone this book was published in 1993, and also point out that Watchmen launched in 1986. UC was groundbreaking in 1993, because lots of people had never seen someone write and draw seriously about comics as a medium. If we take comics seriously today, and we don't feel overly defensive about it, we probably owe some of that credibility to McCloud's defensiveness once upon a time. And he's right that "comics" is best defined as "sequential art", rather than "magazines about superheroes". You can tell all kinds of stories in comic form.

But that defensiveness about "comics can be more than just that superhero junk" is kind of funhouse-mirrored in The Power Fantasy and in its predecessor, Watchmen. I'm admittedly only on the fringes of conversations about superhero comics and their evolution over time... but I know Watchmen was also a groundbreaking comic that shaped comics culture forever. It's a deconstruction of the lighthearted heroic fantasies that came before it, and it inspired a lot of grimdark comics that matched its bleak tone but not its depth and insight.

...or so I'm told. I only read Watchmen once, years ago. I tried rereading it earlier this year, but I couldn't get into it. I just still know all this stuff because that's the level of cultural impact it's had. Also, because so many TPF reviews and blurbs say stuff like, "It's the next Watchmen! It's superhero comics finally moving out of Watchmen's shadow and onto the next thing! It's capturing the true spirit of Watchmen's deconstructionism, not just the surface tone!"

Understanding Comics is one of the best-regarded nonfiction comics of all time. Watchmen is one of the best-regarded comic books of all times. The Power Fantasy is one of the buzziest indie comic books being published right now. All of them roast classic superhero comics pretty hard, and maybe you could read it as an affectionate roast, but I don't know.

Superhero comic books are still usually the face of comics to people who don't read them. Probably not so much as in 1993, but still. How many more comics classics are going to get ahead by throwing them under the bus?

[EDIT: I later took back a lot of this in a follow-up post that you can read here. Writing late at night and not revising your posts has mixed results!]

17 notes

·

View notes