#kirp creates

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

that fucking crab that i hate

#i was so glad to find out that this was a universal experience lmao#rain world#rw watcher#rw watcher spoilers#rw spoilers#animation#kirp creates

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

WL//WH Video Premiere: PLUTO IS A PLANET "2 Way Mirror"

Video Premiere PLUTO IS A PLANET Pluto is a Planet is a Tasmanian two-piece Electro /Dream Pop/ Shoegaze band, consisting of Darren Barnes, whose other musical exploits are the noted Australian Shoegaze outfit “Trillion”, and Tony Hubbard who under the handle of “Kirp” also writes, creates, and produces his own take on Shoegaze. On the new 5-track “Response Too” EP, the pair have ditched their…

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introductory Post

Hello everyone!

While I have had this account for a while, I figured it is finally time to put it to good use!

Let me start by introducing myself: While I mostly go by Kirp online, I will also go by Vivien here to match the blog! I am a university student in Canada, and I like to draw and write in my free time.

I'm going to use this account to yap about the story I'm creating at the moment, and I've added the first drawing of the main three characters that I currently have planned out!

To start, this story will involve one of the characters being forced forward in time to an unfamiliar era, where they meet the others and make friends! There's going to be some kind of Big Conflict where she plays a main part in solving it, but that hasn't been completely planned at the moment. So far all I have is a faint idea and some disjointed snippets, but that's where all creativity starts, right?

(The story will also have lgbtq+ characters. Many of them. All over the place!)

Feel free to ask questions here or in my ask box! I'll do my best to get to them all.

#writing#creative writing#art#digital art#intro post#blog intro#untitled wip#how do tags work#new to this#lgbtq+ characters#first post#idk what else to tag#Closer To You (Further From Home)

1 note

·

View note

Note

yknow I have one of those rly good voice mimicker friends and I decided how funny it would be if i tell him to do a Kira alarm clock ringtone. father it is currently 4:21 am and I have listened to Kira babble and babble about how sleep is important and he likes to play with my hands while i sleep. before you ask why I'm up this early its bc I need to take care of my cats. my, five cats.

Eye.....this ask lowkey whiplashed me ngl jsjddnejej

As much as i hate to admit it my cursed deep voice allows me to do a very good kirp impression as well as a shoetaro and dip one🗿

Clownery aside though i would probably have a sheer heart attack if i'd wake up to THAT fucker talkin to me like-

(yes i drew that also-)

#do not talk to me i have no idea what i was on when i created that abomination of an image#the confessional#but kirp playin w ur hands as u fall asleep....cursed??? b l u r s e d??? i cant figure-#also i dont blame u for staying up late i basically never sleep kdmdmd

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

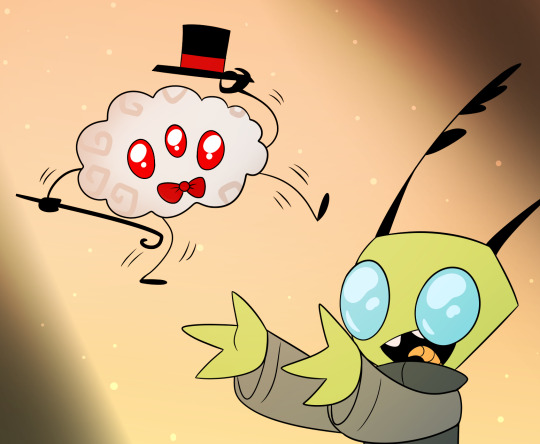

One of the main things I had in mind when creating Marcus (and the start of Kirp's blog I suppose!) was to create a character that lived in the iz verse that was just..completely rational who just happened to be born in the iz universe and the consequences of a character like that living in that world.

It’s certainly not the best place to live in, but Marcus has managed to make a nice life and family for himself in spite of all the insanity of the iz world where that probably shouldn't happen.

Something about that is just kinda touching and funny to me. I’m well aware Marcus and Kirp stand out like needles in a haystack in this universe, but in a way that was the point. Dib and Zim could be trying to kill each other but meanwhile Marcus is just trying to live his best life in the forest with his family.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Wow Kirp, you like so cool as Tallest! I have to ask though, do you know what the control brains are?

THANKS! I MADE IT FROM MY IMAGINATION

I don’t know what a control brain is but it sounds familiar..I will now use my imagination to create what I think it looks like.

BOOM!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

2nd batch of Irken oc fanart.

Ft. @arkasks, @askzelandpen, @skaz-is-jazzed, @ask--kirp, and Wafer created by @mysteriie.

#ooc#other irkens#also I’m making a third batch soon so if you interact with me and your oc isn’t here I’ll get to them soon#now it’s 1am so I’m going to bed goodnight

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

((hey guys guess what))

((With the help of @ask--kirp and @goldeneyedviv, we have created a collaborative blog for three new characters))

((It'll be easier to run and hopefully a little faster!! But feel free to send asks and interact with them because if I don't have something else to do I might lose my mind))

Thank you for that wonderful intro Joe!

Up next to introduce myself is me, Fret!

I am an intergalactic defense attorney, well rounded in all aspects!

Sued? Space cruiser accident? Charged with murder? I can handle it all- come to Fret!

...

Hopefully this little blog thing will make it easier to actually get hired. Probably not, since I'm sharing this blog with a Prosecutor, but we'll see!

I can answer any of your questions about me, my work, or any legal issues you may be having. I'll take your case before the court and win even if the case is a file of jack-shit. I'm smart, I'm resourceful, and I'm desperate. With those three things a man can do anything.

That Prosecutor should be here any second- so I have to take it up to apologize to Joe in advance. We haven't seen each other in a few days- there's a lot of built up insults I'm ready to throw and there's no doubt he's got some up his sleeve too.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evaluation of Project

1. The main motivation behind my designs was the minimalism art style. This was the basis for all aspects for my design, and I tried to follow it as closely as possible.

On the whole the project was intended to be aimed at everyone. However, I did feel the need to narrow it down, which I did to two target audiences. These were, an urban population, primarily teenagers and young adults, and families. This definitely influenced my designs, as I had to accommodate for both. To help me do this, I looked at London 2012, and what they done to brand their event, as this had to appeal to the world, whilst also trying to inspire a similar age group, hence their slogan ‘Inspire a Generation’.

2. The project did not take any dramatic changes throughout its course, in terms of design, other than the change of imagery from the cartoon style of the artist Andrew Kirp I was originally following, to the more type-based design used in my final pieces. One change that did have to be made, was a slight change to my original proposal of work that I set myself, as I think I overestimated the amount of work I would be able to produce, to a good quality, in the time limit I had, and with the resources I had, given the current situation. Originally, I had intended to produce a name and logo for my festival, which I achieved, create my own typeface, which I also managed to do, create a promotion in a space, which was also done, whilst it could have done with slightly more development. The areas which I did not meet my targets were my Visual Identity and Ephemera. I had wanted to make three for each, and whilst I did not state this for the ephemera side of the project in the brief, this was the intention. Shown by my final designs, I ended up managing to make 2 styles of Visual Identity (Food Packaging and Banners) and 2 types of Ephemera (Poster and Ticket), as well as a wayfinding system.

3. At the start of the project I did struggle to manage my time well due to being quite ill. However, after this I knew that if I was to produce a strong set of work, I would have to closely follow the strict schedule I set myself, as seen in my proposal. The extension of one week to the project was a welcome one and managed to put me back on track with my designs.

Towards the end of the project, my inspiration and drive did begin to dip, when creating my process book, purely based on the fact that I was beginning to become tired of seeing the same designs over and over, which I had been developing for the past six weeks.

4. I think that I responded well to feedback in this project, taking all ideas recommended to me and at least attempting to see whether anything came from them. For the majority of the time, this was the case, and the small improvements that were suggested to me made my designs feel more authentic, and of a higher quality.The online tutorials were difficult at some stages, as it is sometimes hard to describe and display your work without doing it in person, however, I think that everyone involved acted in the best possible manner to ensure that we got the feedback we required.

5. Much like other projects, I would say the developmental side of this project is lacking, and still needs more practice. As I was progressing through the project, I was sure that I had made an extra effort to ensure all my design choices, developments and research was documented. However, this was clearly not the case, as upon review now I have finished the project, there are clear gaps in my research, and development.

6. I would not say that I have necessarily learnt any new skills from the final unit of the year. Other than learning coping with an unprecedented situation, I would not say that my design practice has made and new developments, other than perhaps the refinement of my knowledge of the Adobe suite programmes.

7. On reflection, I would say these are the best sets of final outcomes I have produced this year. I was very happy with how they turned out and tried my best to ensure that consistency was kept across all aspects. I also feel as though I followed the design intentions and art styles, I set myself well.If possible, the one area that I think is considerably weaker than the other aspects, is my Promotion in a Space. Whilst it maintains a similar style to the rest of my work, it was hard to create something in a directly similar fashion. This was because of the limitations of space on the van and ensuring that everything looked appropriate and readable.

0 notes

Text

after going through multiple circles of hell its nice to see familiar faces

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Arctic sea spray aerosols mimic those in California

The Arctic is warming faster than any other place on Earth, leading to the formation of sea spray aerosols similar to what researchers see in California appearing during the Arctic winter, according to a new study.

Summertime Arctic sea ice cover is the second lowest on record, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center’s Arctic report card 2019, continuing a rapid decline over the past several decades. That trend has continued into the fall, with ice in the Chukchi Sea northwest of Alaska at its lowest level on record, according to climate experts at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

The thinning wintertime sea ice cracks, creating open water called “leads.” These leads can be over a half mile across, and researchers have discovered they are the dominant source of aerosols in the coastal Alaskan Arctic during the winter.

“We found that the sea spray aerosol was dominating atmospheric particulate matter population at a time when we didn’t expect it to be there,” says senior author Kerri Pratt, assistant professor of chemistry at the University of Michigan. “The composition tracks what you would see in the midlatitudes, off the coast of California during an algal bloom.”

Sea spray aerosol emissions

The researchers collected atmospheric particles at Utqiaġvik, Alaska, an Arctic coastal site at the northernmost point in Alaska, during January and February 2014. Using computer-controlled scanning electron microscopy, they examined thousands of tiny particles individually, determining each particle’s shape and elemental composition.

Then, through collaboration with Andrew Ault, assistant professor of chemistry, they used Raman microspectroscopy, which determines organic composition based on how molecules vibrate when a laser excites them. With this method, they were able to match the organic composition of the sea spray aerosol particles to marine compounds produced by sea ice algae and bacteria.

“Not only do we expect increasing sea spray aerosol emissions with more leads and greater open water area occurring during the winter, but in this study we also observed a unique chemical composition in the wintertime aerosols,” says lead author and recent doctoral graduate Rachel Kirpes.

“There have been very few studies of aerosol composition in the Arctic winter, and this information is needed to better understand wintertime climate impacts like aerosol influence on cloud formation.”

Aerosol ‘fingerprints’

Examining each particle in this way told the researchers that the aerosols differed from aerosols collected in the summer. The winter-collected particles had a thick organic coating composed of “exopolymeric substances”—substances that sea ice algae and bacteria produce that protect them from freezing. Samples collected in September, when the sea ice is now hundreds of miles away, did not have this kind of coating.

“The sea ice bacteria and algae are producing these cryoprotectant polymers so they don’t freeze. When air bubbles burst at the seawater surface, these exopolymeric substances coat the sea salt particles produced,” says Pratt, also an assistant professor of earth and environmental sciences.

Fingerprinting the aerosols also showed that the population of sea ice algae and bacteria is different in the summer versus the winter, Pratt says. More open water during the winter in the Arctic means the microbiology of those ocean waters is changing.

“Now, you’re opening up areas of water that weren’t open before. More sea spray aerosol is being produced, and it’s impacted by the changing microbiology,” Pratt says.

“This impacts the atmosphere: these particles can then form cloud droplets, which impacts surface temperature and precipitation. You get a whole cycle where you’re connecting climate change, open water, and microbiology to the changing atmosphere.”

The study appears in American Chemical Society Central Science. The National Science Foundation funded the work.

Source: University of Michigan

The post Arctic sea spray aerosols mimic those in California appeared first on Futurity.

Arctic sea spray aerosols mimic those in California published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

Janresseger: What to Do to Support Students Who Are Chronically Absent from School?

Janresseger: What to Do to Support Students Who Are Chronically Absent from School?

Two new reports—from the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) and from Attendance Works—explore chronic student absenteeism and its consequences for student achievement and graduation. Under the Every Student Succeeds Act, states must begin reporting data about students’ chronic absence in their accountability reports. Attendance Works even posts an online interactive map from the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution where a person can find chronic absence data about one’s own school district.

Chronic absenteeism is defined as students missing not just days but also weeks of school. Attendance Works defines chronic absenteeism as, “missing 10 percent of school—the equivalent of two days every month or 18 days over a 180-day school year.” While all school districts record students’ absences from school, until recent years most have not tracked each individual student’s accrued absences over the semester or the school year. Now school districts are required to watch and intervene when individual students’ attendance patterns become worrisome.

What is clear is that, while there are a number of ways researchers measure students’ chronic absence from school, the problem is serious: When students miss too much school, they learn less, they fall behind, and they are more likely to drop out without graduating. And students who are poor are more likely to miss school.

Writing for Attendance Works, Hedy Chang, Lauren Bauer, and Vaughan Byrnes explain: “Especially hard hit are children who live in poverty, have chronic health conditions or disabilities, or experience homelessness or frequent moves. When chronic absence reaches high levels in a school or classroom, it can affect every student’s opportunity to learn, because the resulting churn—with students cycling in and out of the classroom—is disruptive for all and hampers teachers’ ability to meet students’ diverse learning needs.”

And before they delve into a data analysis, EPI researchers, Emma Garcia and Elaine Weiss summarize past research: “Poor health, parents’ nonstandard work schedules, low socioeconomic status… changes in adult household composition (e.g. adults moving into or out of the household), residential mobility, and extensive family responsibilities (e.g. children looking after siblings)—along with inadequate supports for students within the educational system (e.g. lack of adequate transprtation, unsafe conditions, lack of medical services, harsh disciplinary measures, etc.)—are all associated with a greater likelihood of being absent, and particularly with being chronically absent.”

When we think about chronic absence, most of us think about students who cut school to hang out—students who are bored or disaffected. But other issues are harder to address. One teacher I know told me about a student who was late every day because she had to wait to come to school until a van came to take her quadriplegic mother to a care center. Another teacher who has been substituting in a huge high school told me he was frustrated because in the five sections of the English class he had to teach every day, it seemed that a different group of students was present each day. It seemed baffling to cope with the churn.

From the University of California at Berkeley and the Learning Policy Institute, David Kirp describes a new program in Los Angeles that seems to be paying off: “The Los Angeles Unified School District has invested in a new, low-cost approach to curbing absenteeism that’s been proven to move the needle. It’s a simple, potent idea: Enlist parents as allies in keeping their kids in school.” Many parents, he writes, are unaware that their children are missing school: “To correct these misperceptions and to enlist parents in keeping kids in school, 190,000 Los Angeles families whose kids met the chronically absent standard in the past will be mailed attendance information five times a year.” The letters are simple: “Billy has missed more school than his classmates—16 days so far in this school year… Students fall behind when they miss school. …Absences matter and you can help.” Kirp reports that chronic absenteeism has dropped not only in Los Angeles, but also by 10 or 15 percent in Philadelphia and Chicago after such reporting to parents becomes routine.

The research from EPI and Attendance Works, however, indicates that chronic absenteeism very frequently reflects that students who miss school are facing serious health and family challenges which can be addressed only through additional support by teachers, counselors and social workers to help students find ways to make their own schooling a priority even when other problems intervene.

Two primary school reforms come to mind. The first is to make classes small enough that teachers can really come to know their students and the barriers for students that make school attendance difficult. This is harder in a middle school or high school, however, where teachers work with likely five classes a day—a total of 125 students even when class size is kept at 25 students.

The benefits of wrap-around, full-service Community Schools (see here or here) become apparent in the context of such challenges. With medical and dental clinics located in the school, parents don’t have to keep kids out of school because they have forgotten the necessary immunizations. The toothache can be addressed promptly with only an hour away from class. Such schools also employ social workers to help families balance the responsibilities that sometimes put care-giving in conflict with school and to help parents and students address issues like transportation.

These schools are also designed to welcome families warmly and authentically. In Community Schools in Action (Oxford University Press, 2005), the assistant director of the New York Children’s Aid Society National Technical Assistance Center for Community Schools, Hersilia Mendez describes the role of parent outreach and parent engagement in a Community School: “In its work in Community Schools, the Children’s Aid Society sees parents as assets and key allies, not as burdens; we aim not only to increase the number of parents involved in their children’s education but also to deepen the intensity of their involvement and to encourage greater participation in their children’s future. As we engage parents in skills workshops and advocacy events, we also create a critical link to the home, allowing us to serve and empower whole families… The Children’s Aid Society wanted to erase the mixed invitation that schools often extend to parents—that parents should be involved in their children’s schooling but only on the school’s terms and often in rather menial ways… For an immigrant like me… Public School 5’s warm atmosphere was beyond belief. The beautifully furnished family room, the smell of fresh coffee, the presence of so many parents at all times, and, in particular, the friendly disposition of the staff were heartwarming. To me, it was an inconceivable atmosphere to find in any school, let alone a New York City public school… The parent involvement model is culturally responsive and provides multiple entry points for meeting parents at their level as well as multiple opportunities to engage with, support, and strengthen the school.” (pp. 42-45)

elaine October 5, 2018

Source

Janresseger

Janresseger: What to Do to Support Students Who Are Chronically Absent from School? published first on https://buyessayscheapservice.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

July 2nd

Today I watched a lecture by Professor Gernsbacher “How Is the Internet Changing the Way We Communicate?”

The lecture was all about how the Internet is not responsible for making communication more brief and less formal. While some of our communication may be brief, this is not a new phenomenon created by the Internet. There are several examples of different forms of brief communication throughout history like short letters, short stories, or telegrams. Telegrams were made to be short because customers were charged by the word. Also, there has always been, and always will be, people who are ignorant to when and/how to use formalities. For example, in 1917 Winston Churchill received a letter with the abbreviation "OMG". Another example is calling instructors "Teach" or "Prof", and this has long been a bad habit of some students, even before e-mail.

Professor Gernsbacher concludes by explaining that what the Internet is responsible for is creating a preference for written over spoken communication. She proposed that it could be that written language is intransient, or long-lasting, while speech is fleeting. Written messages offer the luxury of being saved, searched, or reproduced. Another reason could be that written language is more convenient because it is (usually) asynchronous, or not in real time, whereas spoken language is synchronous (in real time).

A lot of times I much prefer communication that is asynchronous. One time recently that I used it was when I emailed an old employer about getting a record of my hours worked, it is something I need for my PA program applications. I found that this would be more convenient because I wouldn't have to sit by the phone waiting for her response and because it would be too much information to take down synchronously.

Afterwards, I read two articles:

Scott Jaschik’s (2017) “Michigan State Will Ban Whiteboards from Dormitory Doors”

David Kirp’s (2017) “Text Your Way to College”

The first talked about how whiteboards have become a tool for bullying, and that is why they will be banned from the dorms at Michigan State. The second article talks about a texting campaign that will help high school students at risk for not going to college. Students get reminders for deadlines set by their intended colleges and counseling, which increased the applications to/acceptance by elite schools and decreased summer melt— students who are accepted but not enrolled. I think the purpose of reading these two articles was to see that 1) the negatives aspects of the internet (i.e. cyberbullying) do not solely affect the internet and 2) the internet can be beneficial.

0 notes

Note

This suddenly came into my mind but imagine if Kirp lived enough to meet Giorno- Giorno could create Mona Lisa's hands for Kirp. No more girls dying and Kirp can take his fetish to the next level. Everyone is happy. -🦑 anon

It wouldnt be the first time someone thot of this and tbh its a great concept indeed..... although i feel as if kirp is just a greedy UNGRATEFUL bastard in general hence why i dont think he'd be fully satisfied with someone just y e e t i n g hands @ him jebfbrnd

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Got Questions About Education Reform? I’ve Heard Them All.

As I travel around the country on a 24-city book tour, giving talks and meeting with education reform leaders and activists, I get a lot of questions. I thought it might be useful to answer a few of them in print. These are a set I received in Oakland, California, at an event sponsored by GO Public Schools, Educate78, and the Rogers Family Foundation.

When will cities face the brutal reality of failing schools, name that as the reality, and use that as the impetus for change?

Some cities—Denver, New Orleans, the District of Columbia, Indianapolis, Memphis and others—have done so. It requires strong leaders, and they must win the inevitable political battles that result—something that is not always easy.

Replacing failing schools with high-quality schools inevitably means some people will lose their jobs, and that usually drives the teachers union to oppose such changes. Some community leaders will also oppose replacing schools in their neighborhoods, even though the new school operators have outstanding track records.

Reformers need to win the resulting political battles with unions and work with the communities involved to help parents help pick the replacement operator they prefer.

Sometimes cities won’t improve without outside influence. Bureaucracy is slow to change, and patronage politics runs deep in many urban districts. In New Orleans, Newark and Camden, New Jersey, the wake-up call came when the state took over the local school district (or most of its schools, in New Orleans) because of perpetually failing schools. People don’t like losing local control, so even if the state improves the schools, a takeover is often met with hostility. But in all three cities, the reforms have won many parents over, because the resulting schools are so much better than those they replaced.

Community engagement and parent empowerment are key factors to support the development of our schools. How do they fit in?

Systems of choice and charter schools have helped empower parents in many cities. In these systems, the tax dollars usually follow the students, so parents have some leverage with the schools, since they can move their children and the dollars will follow. Many charter schools also have a history of encouraging parent engagement. Home visits, regular parents’ nights at school, and other ways to involve parents were initiated in charter schools and then adopted by district schools, in cities such as Washington, D.C., and Denver.

Many parent empowerment organizations, such as The Memphis Lift and Stand for Children, have helped organize and give voice to parents who support charter schools and school choice. These organizations play an important role in giving parents political influence and allowing their voices to be heard.

In Newark, where more than 30 percent of the students are in charters, Mayor Ras Baraka was anti-charter until local charter supporters registered more than 3,000 parents of charter school students to vote. Baraka then decided to back “unity slates” for the District Advisory Board, which will become the school board when control returns to Newark citizens. Newark had some of the strongest charters in the nation, but without mobilizing charter parents, charter advocates would not have been successful in winning seats on the board.

What might be the unintended consequences of this 21st century strategy?

Any idea can be poorly done. In states that don’t have strong charter laws, authorizers aren’t held accountable to anyone but parents. Unfortunately, some parents are happy if a school is warm and nurturing and will leave their children in a school where kids are falling further behind grade level every year. But if the kids aren’t learning, we’re cheating them, denying them future opportunities. We’re also cheating the taxpayers, who fund public schools to produce an educated citizenry and workforce. So charter authorizers need to hold schools accountable.

That means vetting applications thoroughly before giving charters out, then replacing schools that fail to meet their performance goals by large margins. In states where authorizers abdicate this role, charter schools don’t perform much better than district schools. School systems need both autonomy and accountability.

Also, places with weak authorizers or multiple authorizers usually can’t resolve the equity issues that arise in any school system. Do special needs, low-income and kids learning English have an equal shot at high-quality schools, for instance? Only if authorizers ensure they do by creating common-enrollment systems, workable funding systems for special education, services for those who don’t speak English and publicly funded transportation to school.

This has happened in places with strong authorizers, such as New Orleans, D.C., and Denver, but not in cities with multiple authorizers or district authorizers too preoccupied with operating schools—with rowing—to meet their responsibilities to steer.

Is common enrollment for district and charter schools required for this change?

Ideally, yes. As noted above, enrollment is an equity issue. Without a common-enrollment system, parents with more education, time and know-how can get their kids into better schools.

In 2011, Denver Public Schools rolled out its common-enrollment system, “SchoolChoice.” Before then, parents who wanted their children to attend a school other than their neighborhood school had to research and apply to multiple schools. The district had more than 60 enrollment systems for its own schools alone, plus many more for charter schools.

Community organizations such as Metro Organizations for People pushed for a common-enrollment system on equity grounds. Many low-income parents didn’t have the time or language skills to fill out multiple applications, and they found the previous process intimidating, so they were less likely to apply.

SchoolChoice has clearly increased equity, leading to a jump in the percentage of low-income students and English-language learners attending in-demand schools.

Without common-enrollment systems, parents and schools can more easily circumvent the “required” procedures for applying to certain schools. In Denver, a 2010 study proved that 60 percent of those whose kids attended an elementary school outside their neighborhood got them in through “unofficial” means, such as baking brownies for the principal. Common enrollment put a stop to that.

Is transportation required in what you call ’21st century school systems’?

If we want equal opportunity, yes. There is no true equity unless all students have equal access to high quality schools. If parents can’t get their kids to school each day, they’re going to send them to the closest school, which means they don’t really have a choice. Those who have the means will take their kids to a better school and those who don’t will stay with what’s geographically close.

In systems of choice, there should also be a variety of school models—different schools for different kids. Without transportation, this won’t work as well. Imagine if a student wants to go to a STEM school, but the school in his or her neighborhood is a dual-language immersion school. That student needs transportation to the STEM school—otherwise, the student is forced to attend an educational model that isn’t engaging for him or her.

How do you reconcile choice and the inclusion of ‘non-choosers’ (kids without advocates and families without agency)?

Most families want their children to have the best education they can, but some lack the resources, “know-how” or wherewithal to get their kids into good schools. A few are simply not paying attention, for one reason or another.

In 21st century systems, authorizers and/or school boards are freed of the daily tasks of running schools, so they can focus on steering, which includes ensuring equal access to quality schools. In districts such as Denver, New Orleans, Washington, D.C., and Newark, the implementation of common-enrollment systems has helped level the playing fields so that all students have equal access. (Soon Indianapolis will follow suit.)

After implementing common-enrollment systems, districts and authorizers must provide good information about schools in multiple languages, and they must create centers where parents can go to learn about the schools, as the Recovery School District did in New Orleans. Then they should reach out to families who aren’t reaching out to them, to make sure they get the information and help they need to make good choices. Many have not yet met this challenge.

If districts or authorizers fail to do this, outside organizations can step into the breach. In New Orleans, a nonprofit called EdNavigator now contracts with a series of large employers to help their employees make good decisions about their children’s schooling and deal with any problems that come up involving their schools.

Finally, choice, competition and school accountability help all students, even if their families are not actively choosing. Schools that have to compete often work hard to improve. And if districts and authorizers replace failing schools with stronger operators, as they do in 21st century systems, the students in those failing schools benefit.

There are other districts that have improved their academic performance using a totally different strategy (like Long Beach, California, and Union City, New Jersey). Why shouldn’t our district just use that approach?

These districts have not improved as fast as New Orleans, Washington, D.C., or Denver. In addition, they have required political stability for a long time. Long Beach has had two superintendents over the past 25 years, the second of which was the first’s deputy. It took five years for reform efforts to begin to show progress in student learning, but the board and superintendent stuck with it.

In Union City, profiled in David Kirp’s excellent book, “Improbable Scholars,” the leadership of the mayor (who was an important force for improvement) and district also remained consistent for more than two decades. Under such conditions, even centralized bureaucracies can make significant progress. Union City, after more than 20 years, reached roughly the state average in performance. But New Orleans, with a far tougher population, did so in less than a decade.

If your district can afford to go more slowly, can guarantee political stability for two decades and cannot use charter and charter-like schools for some reason, by all means emulate Long Beach and Union City. Their children are much better off after 25 years of steady system improvement.

What if a city has too many buildings for the number of schools appropriate to the number of students it has?

There are a number of alternatives. Perhaps the best is to lease empty buildings to charter operators, who are often desperate for buildings they can afford. Some districts, such as Denver, Washington, D.C., and New York City, have also shared buildings between district and charter schools, leasing one wing or one floor of a building. This brings in district revenue while helping the charter schools.

The final alternative is to close half-empty schools and sell the surplus buildings. But this is disruptive to students and families, and it is politically difficult. It might also leave a district with too few buildings if enrollment later grew.

Districts should note that D.C., New Orleans and Denver are all growing districts. An embrace of charter schools and choice has turned out to be the best strategy for increasing enrollment.

How does a district close schools while also pursuing new models and approaches?

Closing schools is always tough, but ultimately, if we let failing schools continue to operate, we hurt kids. So districts should engage with school communities, including parents, to demonstrate that the school is not educating their children effectively and show them other operators that might come in to run the school.

The goal is not to close schools put to replace them with better schools. In New Orleans, D.C. and Denver, the districts/authorizers have learned to bring in two or three potential operators and let the parents talk to them about their school models. They also encourage parents to visit the operators’ existing schools. Then they give parents a say in the decision about which operator comes into their neighborhood and educates their children.

States with strong charter laws and funding tend to attract better charter management organizations, which often have more experience with replicating schools and taking over failing schools. So the quality of state legislation is also important.

Can you share a few examples of similar transitions in other parts of government that are farther along, and how you know that it has “worked?”

Contracting of public services is very common in today’s world. Head Start programs contract with nonprofit organizations to operate their centers. Many human services are contracted to nonprofit organizations. Cities contract with for-profit firms to build and maintain their roads, bridges and highways. Garbage collection is often contracted out to competing private companies, as are myriad other public services.

Consider our largest public programs, Medicare, Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act. All use public funds but private service delivery, by private doctors and hospitals. Indeed, the majority of publicly funded services are now delivered by private organizations. Public education is well behind the curve, too often stuck with an Industrial Era model in the Information Age.

When our district granted more autonomy to principals, it worked for some leaders but some didn’t use their autonomy well. What kind of training and preparation do school leaders need for this to be effective? And what do districts that have made this transition do with principals that don’t want to or can’t make the switch?

Leaders of all organizations need leadership and management training, something school principals rarely get. We also need to make principals’ jobs easier by using multiple school leaders, as so many charter schools do: one for academics, another for operations and sometimes a third for culture and discipline. And we need to provide mentors and coaches to principals who struggle with autonomy.

If a school or program is new, giving the leader(s) enough preparation time is critical. When starting a school, they need time to plan and to build a leadership team well before the school opens. In Indianapolis, an organization called The Mind Trust provides financial and other support to leaders planning new school models, typically for a year or two. The district provides at least a year of planning time for the schools after the application is approved but prior to the opening of the school.

Asking strong school leaders to share best practices with others can also be effective. The superintendent of Denver Public Schools (DPS), Tom Boasberg, has hired dozens of people from charters and worked hard to spread successful charter practices to district-operated schools.

For example, DPS brought in charter leaders from successful networks such as Uncommon Schools and KIPP to lead professional development for DPS principals. The district also gave aspiring school leaders a year to work in a strong charter school—and to visit outstanding schools around the nation—to learn how it’s done. By 2015, 84 percent of Denver teachers rated their principals “effective” or “very effective,” a big improvement. Though turnover of principals in low-income schools was a problem for years, by 2016–17 it had slowed dramatically.

Principals who don’t want to operate in an environment of school autonomy can always move on to other positions, as teachers or in central administration—or with a different district or business. Most Americans lack lifetime job security, after all, and there’s no reason principals should be an exception. Finally, principals who fail in an environment of autonomy must be removed, for the sake of the children.

More autonomy for principals has actually increased the cost of some services in our district, like with centralized food service. How should a district balance the need for efficiency through centralized services with this desire for autonomy?

Services that are efficient but not effective are a waste of time. Most teachers, for instance, think the professional development their districts force on them is a waste of time. Making it more efficient would be no help at all.

We should pursue the most cost-effective methods to educate children. Often centralized food services do not provide the nutritious meals that school leaders want for their children—instead loading them up with carbohydrates and sugar.

If we let school leaders choose their food services, we’re likely to get better nutrition, leading to more learning. In addition, competition between food service providers can lower costs. But if a district contracts out food services competitively, it can also get those lower costs. If school leaders are satisfied with the quality of the food, a centrally managed food service can work—though the power to go elsewhere does help school leaders get what they want from food service providers.

Even in areas where a monopoly clearly offers efficiency advantages, such as school busing, those advantages can sometimes be illusory. Before Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans used one bus system, which was centrally managed. But there was so much corruption and inefficiency that it was quite expensive—some bus drivers used their district credit cards to sell gas to truck drivers. Today each school manages its own busing, which should be more expensive. But the system spends the same percentage of its funds on transportation as it did before the reforms.

A few services may need to remain centralized monopolies, but most do not. Forty years ago, the school district in Edmonton, Alberta, figured out how to decentralize district services, and their model has been used widely since, by governments at all levels. Most central services are turned into public enterprises and capitalized, but their monopoly is withdrawn, so schools can go elsewhere to purchase the service. Then the funds are distributed to the schools, and the new service enterprises must earn their revenue by selling to the schools. This works like a charm, and every district should do it. To learn more about it, see my chapter on this strategy at http://ift.tt/2pdFB0f.

How have districts worked collaboratively with unions on this strategy?

For the most part, they haven’t. Twenty-first century systems are decentralized, giving power back to the schools and the people who run them. As a result, they take power away from the unions. While some charter schools have chosen to unionize, most have not. Even in charter-lite models, if teachers in a school can vote to leave the collective bargaining agreement, they often do—which means there’s little incentive for the union to support that model either.

The unions have publicly supported teacher-run schools, an educational model used in both district and charter schools, because it increases teacher professionalism and teacher voice. In Minnesota, the teachers union created a charter authorizer, primarily to authorize teacher-run schools. And in Springfield, Massachusetts, the teachers union agreed to participate in an Empowerment Zone Partnership with the state, which is overseen by a board that now authorizes 10 of Springfield’s schools. Four of the members are appointed by the state, three are local leaders.

The union agreed to a longer school day and slightly higher pay, in part because the Partnership offered to require leadership councils at each zone school, with four teachers elected by the teaching staff and one appointed by the principal. The councils work with the principal to make decisions, and they must approve his or her annual plans for the school. (For more information, see our report on Springfield at http://ift.tt/2Akf0j3.)

Springfield’s example offers a route other districts could take to convince unions to support 21st century strategies. Most teachers want more say in how their schools run, and sometimes their unions will back reforms they would otherwise oppose if they increase teacher power. Sadly, however, the statewide union in Massachusetts is fighting against a bill to allow other districts to do what Springfield has.

An original version of this post appeared at the Progressive Policy Institute as David Osborne Answers Frequently Asked Education Reform Questions.

Photo by @darby, Twenty20-licensed.

Got Questions About Education Reform? I’ve Heard Them All. syndicated from http://ift.tt/2i93Vhl

0 notes

Text

Who Needs Charters When You Have Public Schools Like These?

Who Needs Charters When You Have Public Schools Like These?

New York Times, April 1 2017.

David L. Kirp APRIL 1, 2017

Continue reading the main storyShare This Page

Share

Tweet

Email

More

Save

Photo

Starting in kindergarten, the students in the Union Public Schools district in Tulsa, Okla., get a state-of-the-art education in science, technology, engineering and math. CreditAndrea Morales for The New York Times

TULSA, Okla. — The class assignment: Design an iPad video game. For the player to win, a cow must cross a two-lane highway, dodging constant traffic. If she makes it, the sound of clapping is heard; if she’s hit by a car, the game says, “Aw.” “Let me show you my notebook where I wrote the algorithm. An algorithm is like a recipe,” Leila, one of the students in the class, explained to the school official who described the scene to me. You might assume these were gifted students at an elite school. Instead they were 7-year-olds, second graders in the Union Public Schools district in the eastern part of Tulsa, Okla., where more than a third of the students are Latino, many of them English language learners, and 70 percent receive free or reduced-price lunch. From kindergarten through high school, they get a state-of-the-art education in science, technology, engineering and math, the STEM subjects. When they’re in high school, these students will design web pages and mobile apps, as well as tackle cybersecurity and artificial intelligence projects. And STEM-for-all is only one of the eye-opening opportunities in this district of around 16,000 students. Betsy DeVos, book your plane ticket now. Ms. DeVos, the new secretary of education, dismisses public schools as too slow-moving and difficult to reform. She’s calling for the expansion of supposedly nimbler charters and vouchers that enable parents to send their children to private or parochial schools. But Union shows what can be achieved when a public school system takes the time to invest in a culture of high expectations, recruit top-flight professionals and develop ties between schools and the community.Continue reading the main story Union has accomplished all this despite operating on a miserly budget. Oklahoma has the dubious distinction of being first in the nation in cutting funds for education, three years running, and Union spends just $7,605 a year in state and local funds on each student. That’s about a third less than the national average; New York State spends three times more. Although contributions from the community modestly augment the budget, a Union teacher with two decades’ experience and a doctorate earns less than $50,000. Her counterpart in Scarsdale, N.Y., earns more than $120,000. “Our motto is: ‘We are here for all the kids,’ ” Cathy Burden, who retired in 2013 after 19 years as superintendent, told me. That’s not just a feel-good slogan. “About a decade ago I called a special principals’ meeting — the schools were closed that day because of an ice storm — and ran down the list of student dropouts, name by name,” she said. “No one knew the story of any kid on that list. It was humiliating — we hadn’t done our job.” It was also a wake-up call. “Since then,” she adds, “we tell the students, ‘We’re going to be the parent who shows you how you can go to college.’ ” Last summer, Kirt Hartzler, the current superintendent, tracked down 64 seniors who had been on track to graduate but dropped out. He persuaded almost all of them to complete their coursework. “Too many educators give up on kids,” he told me. “They think that if an 18-year-old doesn’t have a diploma, he’s got to figure things out for himself. I hate that mind-set.” This individual attention has paid off, as Union has defied the demographic odds. In 2016, the district had a high school graduation rate of 89 percent — 15 percentage points more than in 2007, when the community was wealthier, and 7 percentage points higher than the national average. The school district also realized, as Ms. Burden put it, that “focusing entirely on academics wasn’t enough, especially for poor kids.” Beginning in 2004, Union started revamping its schools into what are generally known as community schools. These schools open early, so parents can drop off their kids on their way to work, and stay open late and during summers. They offer students the cornucopia of activities — art, music, science, sports, tutoring — that middle-class families routinely provide. They operate as neighborhood hubs, providing families with access to a health care clinic in the school or nearby; connecting parents to job-training opportunities; delivering clothing, food, furniture and bikes; and enabling teenage mothers to graduate by offering day care for their infants. Two fifth graders guided me around one of these community schools, Christa McAuliffe Elementary, a sprawling brick building surrounded by acres of athletic fields. It was more than an hour after the school day ended, but the building buzzed, with choir practice, art classes, a soccer club, a student newspaper (the editors interviewed me) and a garden where students were growing corn and radishes. Tony, one of my young guides, performed in a folk dance troupe. The walls were festooned with family photos under a banner that said, “We Are All Family.” This environment reaps big dividends — attendance and test scores have soared in the community schools, while suspensions have plummeted. The district’s investment in science and math has paid off, too. According to Emily Lim, who runs Union’s STEM program, the district felt it was imperative to offer STEM classes to all students, not just those deemed gifted.Photo Students congregate at the start of the Global Gardens after school program at Union Public Schools district’s Christa McAuliffe Elementary School in Oklahoma. CreditAndrea Morales for The New York Times In one class, I watched eighth graders create an orthotic brace for a child with cerebral palsy. The specs: The toe must be able to rise but cannot fall. Using software that’s the industry standard, 20 students came up with designs and then plaster of Paris models of the brace. “It’s not unusual for students struggling in other subjects to find themselves in the STEM classes,” Ms. Lim said. “Teachers are seeing kids who don’t regard themselves as good readers back into reading because they care about the topic.” A fourth grader at Rosa Parks Elementary who had trouble reading and writing, for example, felt like a failure and sometimes vented his frustration with his fists. But he’s thriving in the STEM class. When the class designed vehicles to safely transport an egg, he went further than anybody else by giving his car doors that opened upward, turning it into a little Lamborghini. Such small victories have changed the way he behaves in class, his teacher said — he works harder and acts out much less.

Superintendents and school boards often lust after the quick fix. The average urban school chief lasts around three years, and there’s no shortage of shamans promising to “disrupt” the status quo. The truth is that school systems improve not through flash and dazzle but by linking talented teachers, a challenging curriculum and engaged students. This is Union’s not-so-secret sauce: Start out with an academically solid foundation, then look for ways to keep getting better. Union’s model begins with high-quality prekindergarten, which enrolls almost 80 percent of the 4-year-olds in the district. And it ends at the high school, which combines a collegiate atmosphere — lecture halls, student lounges and a cafeteria with nine food stations that dish up meals like fish tacos and pasta puttanesca — with the one-on-one attention that characterizes the district. Counselors work with the same students throughout high school, and because they know their students well, they can guide them through their next steps. For many, going to community college can be a leap into anonymity, and they flounder — the three-year graduation rate at Tulsa Community College, typical of most urban community colleges, is a miserable 14 percent. But Union’s college-in-high-school initiative enables students to start earning community college credits before they graduate, giving them a leg up. The evidence-based pregnancy-prevention program doesn’t lecture adolescents about chastity. Instead, by demonstrating that they have a real shot at success, it enables them to envision a future in which teenage pregnancy has no part. “None of this happened overnight,” Ms. Burden recalled. “We were very intentional — we started with a prototype program, like community schools, tested it out and gradually expanded it. The model was organic — it grew because it was the right thing to do.” Building relationships between students and teachers also takes time. “The curriculum can wait,” Lisa Witcher, the head of secondary education for Union, told the high school’s faculty last fall. “Chemistry and English will come — during the first week your job is to let your students know you care about them.” That message resonated with Ms. Lim, who left a job at the University of Oklahoma-Tulsa School of Community Medicine and took a sizable pay cut to work for Union. “I measure how I’m doing by whether a girl who has been kicked out of her house by her mom’s boyfriend trusts me enough to tell me she needs a place to live,” she told me. “Union says, ‘We can step up and help.’ ” Under the radar, from Union City, N.J., and Montgomery County, Md., to Long Beach and Gardena, Calif., school systems with sizable numbers of students from poor families are doing great work. These ordinary districts took the time they needed to lay the groundwork for extraordinary results. Will Ms. DeVos and her education department appreciate the value of investing in high-quality public education and spread the word about school systems like Union? Or will the choice-and-vouchers ideology upstage the evidence?

David L. Kirp is a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, a senior fellow at the Learning Policy Institute and a contributing opinion writer.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook and Twitter (@NYTOpinion), and sign up for the Opinion Today newsletter.

A version of this op-ed appears in print on April 2, 2017, on Page SR2 of the New York edition with the headline: What an Ordinary Public School Can Do. Today's Paper

from Blogger http://ift.tt/2ovsvaq via IFTTT

0 notes