#mimetic circulation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

composition no. 8 (so far)

REFRAIN

It's a voice calling to me in the night, a voice I recognize from deep within, a voice I only somewhat actually hear.

"Come back."

SONG OF ECHO

Come back. Haven't you seen thematic solitude for as long as you could?

Come back. There's merit in comfortable vanity where comfortable vanity is mimetic music.

Come back. Tell me all the abstractions you've found. Let's rebuild with them.

Come back home. You've been roaming long enough.

ETERNAL CONSTRUCTION SITE ONLY MUCH BIGGER

First I must say where I have been.

Imagine a mansion in eternity. Would it have a make immaculate or ruinous? The merit to perfect bricks is aesthetic, its mode ideal: a perfect brick is what we aspire for bricks to be, with edges sanded smooth and corners exactly pointed; a mansion constructed as such will be a perfect mansion, but would it describe an eternal one? Immaculate polish, maintained according to immaculate conception, does not stand alone without manual upkeep. And a mansion, as a construction, must stand alone (or else we are describing not a mansion but an eternal construction site).

So then, the bricks must be ruinous. Crumbled, imperfect, whittling away towards nothing. Right? Does that hold up for eternity? In a matter of time, the mansion would be a heap of heaps, and later still not even that, the grains of dust blown by wind(?) into the grand temporal circulation patterns, more a part of eternity itself than of the intended construct. Does that describe a mansion?

Obviously this exercise is linguistic, then, and there is no clean answer. Surely? But, if there is no answer, where have I been? An abyssal plain? The unanswerable strand? The perpetually temporary Street of Roads, on the outskirts of the center of fabled underscore? I exclaim, I have been in eternity's mansions.

In truth, I still do not know which of the two makes these mansions were (ideal, or dilapidated), and I present the above to you as condensations of suppositions that had entertained my mind in moments of lucid contemplation. I know only that these were mansions-- at least while I was in them. I was not only in the mansions. My pilgrimage has been winding, and you can find my footprints on many an eternal sand. I am here now speaking of the mansions.

Did they have purposes, or owners? What purpose does any mansion have but to present its inhabitant? A house is designed to be inhabited, and so if a mansion only needed to be inhabited, it would have been a house and have no need for the extravagant size. Adding extravagance to a house, even simply making it much bigger, is like installing a frame onto a canvas: it brings explicit presentation, it emphasizes the presence of presentation. The eternal mansion eternally presents whoever inhabits it.

I inhabited, for a while, an eternal present. That's a slightly different sentence where "present" now qualifies "eternal" rather than "I." The future could be seen from the back windows, the past from the books I'd read. For me, the inhabitant, it was hard doing to focus on either of those at all. The mansion, trappings and all, took up my time. I suspected, and even now think back and wonder, that I was not the only inhabitant. Maybe there were others, maybe there were to be others, and I was alone during my allotted stay. Maybe I was not alone and the mansion was simply that big. One is allowed to question-- anything, in fact, including-- whether I was "the inhabitant" and not a guest.

Where did the mansion come from? Where its materials, its constituent parts? Suppose an eternal mansion has eternal parts. Well, which kind of "eternal mansion," the immaculate or the ruinous? Whichever one the bricks, that one the parts: either way, they came from Earth, from Time as we have known it. I did not stay long enough to be absolutely sure of the specifics, though I have made observations. They are all of this sort:

- I slept on a bed. - It remained the same bed for a number of days, months, more. - It would eventually change to a different bed, and never back to a previous bed. - I never saw it change, though I was not in the same room as the bed all of the time and did not make a concerted effort to see it change. - It was not always a particularly comfortable bed. Sometimes it was.

It is reasonable to assume the nature of the eternal mansion's bricks is the same, with imperfections being replaced when necessary. I did not observe those changes happening either, which on one hand may be more surprising, as there are a lot of bricks in a mansion and I ought to have seen the change happen at least once, but on the other hand may be just as you'd expect, as I do not make a habit of regularly and rigorously watching specific bricks in a wall all day every day. And, for that matter, this is rooted in an assumption. Perhaps the bricks operated differently than the materials of the interior.

I was not the perfect witness to the mechanisms of this mansion, as I spent the greater portion of my stay invested in my own thoughts and activities, those activities usually being further thoughts. I do not have a list of the things I thought about. I was there for a very long time. Many of the things I thought about, I will bring up in natural course in coming posts, blogs, websites, compositions.

It was, they were, mansions. Yet it was not peace.

NESTED

It was not peace, because I spent my days thinking without words. I was interested in this development at first, as it was a relief to change away from the constant words and noises of the brain to which I had grown so accustomed. This persisted, though, and after even a year of this I was now accustomed to mental silence, and words became rare. In that environment, the fluidity of the eternal, I wanted to maintain a pace of words in my head; I saw it as like a vitality without which I became at risk of transforming into a statue, or worse, a feral creature unrecognizing of humanity.

Consider the impossibility of being a writer of words, including the words on this very blog, when there simply are none. This wasn't your everyday lack of words, either. This was a mind that, from birth, was always buzzing, and growing, had many words, through life's chaos, plunging forward, often failing but always trying to articulate happenings and emotions in 26 characters and 9+ punctuation marks (the plus sign not even included in that 9), now sick of fire, weary of change, bruised by strife, aching, so aching, could keep going but instead decides to... stop, temporarily. "Temporarily" turns into "for a while." "For a while" turns into "from now on." Stories, what stories? Those stories? Those were written by a different man, and so they appear as such to my brain now. How can I proceed? How can I describe what went on in my head?

It's not that there were no words. Words in the head are more like.. abstractions of stimulus that calls for decision, they function in that role. Whenever something would happen that called for my decision, the words were there, eventually. Therefore, when I found myself in the eternal mansion, when I settled down to rest my aching legs awhile, I had nested within an environment of negligible stimulus, and my own psychology trapped itself. I was in trouble. All inertia had ceased; there was no more drive. But, do you see? There was nothing doing. Willing myself back into having words, in that place, would not happen.

Not without the dolls.

IN A SILENT WAY

The dolls helped me find words. I did not find the dolls at first, not for a long time that may have been a year. They were tucked away in a room of the mansion I did not venture around. The mansion was huge, and its interior felt like many different houses and structures strung together next to each other in one architectural design, so that after a little bit of preliminary wandering, I had settled on a set of rooms that could serve as a comfortable "house" for me to live in, and there was no reason to explore the rest (beyond curiosity, which the desire for rest at this point overshadowed). Any exploration would quickly run into the issue of exhaustion, as the true scope of that mansion had to have been on the scale of square miles.

The mansion's interior plan, as I eventually got a sense, had modularity to it. A bunch of rooms make up a "house." A bunch of houses are neighbors around a "courtyard," which in some cases is a literal open-roof courtyard (more like a whole park) and in other cases is an assortment of unique rooms. I had no reason to call them "houses" or "courtyards" other than my own need to name them, so don't get caught up in the names. Fundamentally it was all rooms, rooms, rooms.

In any case, my house bordered one given courtyard, and the dolls were in a room several courtyards away, so it was inevitable that I wouldn't find them for a long time. I spent that long time perhaps a little aware of the dolls, paradoxically. I was aware of the mental trap into which I had stumbled, an unequal venting of inertia until starting myself back up again proved more effort than all sense suggested, and furthermore I was also aware of an irrational Hope emerging from the wordless patterns of Tired... a hope that this lack of inertia which had itself come out of inertia would, itself, one day resolve. A hope that I would one day again move, spurred on by some hypothetical curiosity. I reasoned that a mansion like this must contain many curiosities-- many things that I would find curious. Surely. And it did, of course. But even in the profound period of laziness, I still had a hope that I would find some of them, and that I would react appropriately, find them.. curious.

I'm perhaps getting away from myself here. But this style of ramble is appropriate for the contents being narrated. These words fit the wordless, as it's not really about the words, but about the rhythms and structures, the inexhaustible exhaustion, the round-and-round roundabout riddles, every promise of a new subject seeing interruption as the discursive voice sinks into an old whirlpool. Really, it is no wonder that I spent much time resting, but now imagine these whirlpool sentences carrying on even when the words have ceased, imagine a ramble of empty sentences, a roundabout of punctuation-- then you will have considered the chamber music of my everyday life in that mansion.

That, for (I want to say "several") unbroken years, was my mental landscape. Some words, memories of words, washed up from the waves of blank, flotsam from a skillset I once had. It is vital to me now that I have or am retraining my articulation that I try many times to retroactively describe what it was like. Autobiography is a priority, and I am too spiteful to have gone through that and let it remain unspoken.

But the dolls.

I'm still not ready to talk about the dolls yet. There's a bit more I have to say.

THE FORMAL CAUSE OF METAPHYSICS

In a mind without words but shaped by the memory of words, time's passing is experienced elsehow. I felt it like emotions. In an environment without stimulus but shaped by the form of where stimulus might be, emotions are experienced without obscurity. I saw them like clouds. In an emotion without subject but remembered like any emotion with subject would be, time passes long-long. The proof is in the putting.

In talking of this now, having to pull my memories from back then and put words to the wordless, I fall back on the mannerisms of smart people whose works I have read far more recently. All this time, I've been speaking in the style of Samuel Beckett, and in the last paragraph I recalled some Michael Stevens. There simply are no words to adequately convey this, only references and signs, and signs signifying signs. What was that one. Umberto Eco. Of course.

There was a time, at the very dawn of protohistory (i.e. long before this blog or even the whole series of blogs, long before I even had the "protohistory" reference I just made), when I spoke like this too, pulling from contemporary sources, signs signifying nothing but their own technicalities, and fired away my sentences like and as the teenager I was, tasked with describing a past far bigger than any of the words I heard. And the word of the day then was "abuse," unsatisfactory but at least a container of those fires that escaped my brain (far better described through signs like "the eldritch" and "cosmic horror," signifiers of the impossible). The word of the day now is not quite as simple as that, though it's one I recognized even then:

"Isolation."

It's the theme, you see, of all this. Here I sing, you see, the refrain. It's isolation. All the books I've read talk about it, and none of them capture it. How, then, can I capture the unspeakable? How do I speak of where I've been, for eight long adult years, without merely repeating the readily-dismissable forms of the past? It's the refrain, I sing. How do I write about years spent unwriting my own brain?

Well, as you can see, I elected to begin with a conceit: a conversation with a personal god that frames a longer expansion. That expansion treats the allegory, an invention, that is the eternal mansion. Within this expansion, there is a maze, barely mentioned. This composition is set within a maze, in contrast to other works of mine that have been mazes. There's still more to be said, and my pace in setting it all down has been slow, so I can't tell you how long it will be before I'm done. But that's alright. I want this composition to have a slow tempo anyway. Every word must be taken into the mind, considered as an effort. What you're reading, my EAT, my sweet, my last mirror, my lost reader, is the product of the resolution of its own conflict. I am writing now because I am no longer in those mansions. The writing treats a foregone conclusion because it's not really about those mansions. It is about finishing a long thought far bigger, too bigger, than the shadow of a name.

Now I have to kill the You again and try, but only try, to speak of I again. End the refrain, but we will return.

The secret is in the emotions. Isn't it always? The emotions felt in those mansions, devoid of any stimulus that those emotions would otherwise treat as subject and color, in the absence of any natural form, gradually and with conscious practice over the course of courses of times and time, must take on-- must reveal-- the form of emotions themselves. Cut out all distractions, and the form even of the formless may be discerned.

I saw them like clouds, and necessarily like rain and the rivers too. Therefore, I saw emotions, in their purest form, as water. "They come and go like weather..." said one memory of a creation of my head. "Picture yourself by the rushing river of human history as the flotsam of memories drift by..." said another memory of a creation of someone else's. "The Cloud of Look-Like," said one more memory of a creation of my head, "does not exist, yet those who behave as if it does manage to get something right. Therefore, existence is not the only form that our reality accepts..."

Emotions, being of a similar chemistry as that of memories (in fact, what are emotions if not memories stripped, with time, of their content, left only with their form?), move. They enter our focus, color whatever thoughts and sensations are in front of us, then carry on, leaving us to reckon with the consequences of our actions taken under colored impressions. "We are left holding the bag..." says a nameless memory, but I must disagree with that premise, as it supposes that emotions do this on purpose, out of some design of our greater suffering. We are the ones with the designs, we are the ones who create those designs over the course of years, and we leave emotions to hold the bag. Emotions do not have intent. Emotions are like clouds. They come, they paint a sky that we then interpret forms out of which we call "weather," they go none the wiser, neither the more foolish, only the dumber. (remembering what "dumb" actually means)

It is not inherently pleasant to stand within a rainstorm. It is neither inherently depressing to stand under an overcast sky. A sky devoid of clouds, beautiful to look at, leaves my body exposed to the ultraviolent rays of the Light of Knowledge, the Sun we must in our time put down. The rubrics of nature were set before us and did not presume our needs; to change them for one is to change them for all. We must be certain that we know what we are doing. We must understand, and to stand under that Ideal Sun is to exert more effort than life had before prepared me for.

To stay in the eternal mansions, without words, meant watching the slow flow of emotions go, never to know, only to low, never to yes, only to no. Observation yes, composition no. Forget all I know in hopes of one day remembering when I have a better emotional foundation. And that.. may never happen. It may never happen even with the fount of all human knowledge to drink from, it may never happen even with the solidarity of friend and foe engaging me on the daily, it cannot happen when devoid of all drive and alone in rooms I will not describe. I figured that much not long into my stay. And yet, without drive, there is no movement. This situation would resolve itself only painfully slowly, all the while watching my emotions... watching them go.

It was scary in the way that horror stories never know.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Not sure who the dysgenics post is vaguing, and I don't want to get into this off anon, but sterilization (ostensibly voluntary) of genetically inferior potential parents is an idea that I've seen advocated by someone concerned about dysgenics

It's a side post to big discussion involving some people I follow about Scott Alexander's pessimistic predictions for the future. All very silly Decline and Fall stuff, as @discoursedrome put it.

(And even then I think he was being too charitable--"the whole world looks like it's decaying if you live in the political and economic center of it and even small things are shifting around you" is true, but I actually don't think very big shifts are occurring--I could go on at length here, but suffice it to say I think US hegemony is assured for the time being, we're making progress even on the biggest issues facing our society, like climate change, and I simply do not think a 50/50 chance of humans destroying themselves within 100 years--or even experiencing a major global collapse--is realistic. I think Acott Alexander lives inside a bubble of people with a lot of really silly ideas about the world and how it works, where being clever is seen as a sufficient substitute for expertise, and he is there because he is fundamentally gullible to any idea packaged in the right aesthetic.)

But historically, the idea of dysgenics/eugenics arose in the context of Social Darwinism. I think Social Darwinism is a funny animal; it is a surface-level retread of some ideas that were in circulation in Britain for a long time before Darwin. Specifically, the idea of a hierarchy of virtue that exists alongside and underpins a hierarchy of class is nothing new--that in itself may be as ancient as human civilization, since every society needs an ideology to legitimate its power structures. But in the context of early 1800s Britain, you had the Whigs, the new middle class of the burgeonining Industrial Revolution, looking to join the ranks of power--either to position themselves against the lazy shiftless aristocracy who did not work for a living, or to join them, to be like "yes, we don't have titles [but please give us some!], but we're also not like those awful lazy/drunk/Irish poors." I think alongside the Whiggish enthusiasm for science and progress, Social Darwinism nicely blends both that older idea of a hierarchy of virtue with newer ideas about dispassionate natural processes to produce an idea with a lot more mimetic heft for the new age (if you don't know much about either Darwinism or economics) than the unfiltered Anglicanism of the pre-1860s generations, one which takes the exact same policy prescriptions and like 90% of the same underlying rationale ("we cannot improve the social condition of the poor; they will waste their money on drink and gambling, breed like rabbits if their children are no longer often starving to death or dying of cholera, and they will corrupt the virtue of our society") and adds just a light dusting of pseudoscience ("we cannot improve the social condition of the poor; they will waste their money on drink and gambling, breed like rabbits if their children are no longer often starving to death or dying of cholera, and they will have a dysgenic effect on the white race").

(Along with the corollary, obviously, that we should get rich people to breed more, because clearly wealth and intelligence and virtue are heritable.*)

I do not think Scott Alexander is a Social Darwinist. Almost nobody is these days, and while I think he sometimes takes some very bad ideas seriously, I do not think he is at "19th century British racist" levels of taking bad ideas seriously. AFAICT the kind of eugenics Scott Alexander would support is what's sometimes called "positive eugenics," i.e., not sterilizating people against their will, but making sure that (for instance) middle-class people aren't actively discouraged from having kids by the tax structure, and using genetic engineering if/when it becomes available to gradually improve longevity, health, and IQ. But where concerns about dysgenics do pop up in modern authors, they tend to echo or simply restate older Social Darwinist concerns--as a general argument against welfare, for instance. But Scott has also talked about how UBI is a good idea, and that's pretty much the welfariest welfare you could possibly welfare. So I assume he's not worried that if we give the poor food, we will be up to our eyeballs in shiftless drunk Irishmen within a few generations.

(*"Heritable" is a great word! Wealth, for instance, is indeed heritable! How much money you will have is strongly predicted by how much money your parents had. But "heritable" is obviously not the same as "genetic," and this kind of equivocation--like that between intelligence and education, or between virtue and conformity to arbitrary social norms, was the bread and butter of 19th and 20th century Social Darwinists.)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

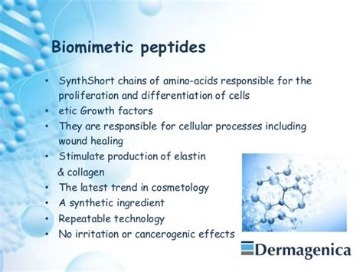

Steven Baris Diagrams and Art

an important (although not necessary) feature common to diagrammatic-based art practices that distinguishes them from more “self-referential” artworks in the contemporary world—namely, these artists are often motivated to create more than mere objects or beautiful optical displays that point to nothing outside of themselves. Artists working in a diagrammatic vein are less likely to subscribe to Frank Stella’s famous statement, “What you see is what you see.” Certainly such a view would have been incomprehensible to most artists and artisans working in pre-modern eras, as there was little to no daylight between what we would call “artworks” and the cultural and religious structures of meaning underwriting them.

The vast majority of frescos, sculptures, paintings, drawings, reliefs, stain glass windows, manuscripts, mosaics, tapestries, and so on were meant to reflect or illustrate “higher order” religious, mythological, philosophical, or royal ideals. Contemporary diagrammatic-based art practices may or may not seek to reflect these kinds of ideals, but their makers generally “intend” for their artworks to point to something extrinsic to the actual artwork even if that something is difficult to pin down precisely.

I will even go out on a limb and suggest that in many instances, this “something extrinsic,” this “more than what you see” is indeed meaning itself

But even though meaning in contemporary art is often highly personalized and idiosyncratic, more than a few artists are compelled to articulate the inarticulable in their work through abstract, non-pictorial means; and I am suggesting that diagrammatic-based practices offers an especially viable platform for this to happen.

______________________________________________________________

by lending more or less equal significance to all the parts of the image, the viewers’ attention would be distributed in such a way as to encourage more correlative interactions among the various parts.

Grid-like visual grammars are stridently spatial, and as such, they eschew sequential/narrative modes of representation in favor of a spatial, simultaneous reception of information. This features prominently in many diagrams; ironically, even those attempting to “map” temporal features onto graphic displays (e.g. graphs, charts, time tables).

Krauss also makes an interesting argument when she states: “In the increasingly de-sacralized space of the 19th century, art had become the refuge for religious emotion; it became, as it has remained, a secular form of belief.” In this context she says the grid allowed artists to “magically resolve the para-logical contradiction between a materialist secularism and a spiritualism [metaphysics] in a sustained suspension.”

Pablo Picasso: Bottle of Vieux Marc, Glass, Guitar and Newspaper

For example, a glancing analysis of Picasso’s Bottle of Vieux Marc, Glass, Guitar and Newspaper (see Figure 6), reveals the telltale presence of “white space” and how it functions to subvert traditional hierarchical composition and instead, prompts the viewer to “correlate diverse packets of information,” (e.g. text, hints of pictorial shading, geometric shapes, lines and notations).

Marcel Duchamp: Network of Stoppages

Francis Picabia

“in Dada, the diagrammatic served as one of three visual tactics—montage and the readymade being the other two—for embracing and representing this epistemological crisis.” Joselit traces several artists’ experiments with combining images and text where, among other aspects of their work, he hones in on their diagrammatic drawings, paintings and designs. Here he states that “such combinations of word and picture [“mimetic units”] are precisely what characterizes more ‘canonical’ Dada diagrams by artists like Picabia. In such works, image and text circulate within a single plane of signification.”

In full diagrammatic fashion, these works suppress mimetic picturing in favor of explaining, albeit in a highly idiosyncratic and enigmatic manner.

“The diagram reconnects the disconnected fragments of representation invented by cubism. This act of reconnection does not function as a return to coherence, but rather as a free play of polymorphous linkages, which, to this day, remain a central motif of modern (and postmodern) art.”

The viewer is enjoined to take an active role of cross-referencing and decoding.

As with so many conventional diagrams, what takes place in The Large Glass is a transfer of predominantly temporal relations (i.e. processes) into spatial/graphical relations—thus transforming a predominantly sequential order of “events” into a graphic display of simultaneous interrelationships.(3)

“…a relatively neutral blank ground in and around the images, words, symbols or notations. It is the strategic presence of the white space that prompts the viewer to focus less on the individual components, but instead to extract meaning by actively correlating one “packet of information” with another so as to conjure new and unexpected relationships.”

0 notes

Text

Hito Steyerl (2)

In defense of the poor image

Key words

Accelerates, it deteriorates // itinerant // reproduced // lumpen proletarian // effigies // stultification // mimetic // cineastes and esthetes // bureaucratic // blurred // amateurish // dematerialisation // semiotic // deterritorialization // dubious data pools // stupefaction

Quotes

"transforms quality in accessibility"

"Its filenames are deliberately misspelled" (me)

"Poor images show the rare, the obvious, and the unbelievable - that is, if we can still manage to decipher it"

" focus is identified as a class position of ease and privilege, while being out of focus lowers one's value as an image"

"In the class society of images, cinema takes on the role of a flagship store. In flagship stores high-end products are marketed in an upscale environment. More affordable derivatives of the same images circulate as DVDs, on broadcast television or online, as poor images"

"Resolution was fetishised as if its lack amounted to castration of the author"

"Twenty or even thirty years ago, the neo liberal restructuring of media production began slowly obscuring non-comercial imagery, to the point where experimental and essyistic cinema became almost invisible"

"Disappearing again into the darkness of the archive"

"but the economy of poor images is about more than just downloads: you can keep the files, watch them again, even reedit or improve them if you think necessary"

"Many works of avant-garde, essayistic, and non-commercial cinema have been resurrected as poor images. whether they like it or not"

"Poor images are poor because they are not assigned any value within the class society of images - their status as illicit or degraded grants them exemption from its criteria"

"one the other hand, this is precisely why it also ends up being perfectly integrated into an information capitalism thriving on compressed attention spans, on impression rather than immersion, on intensity rather then contemplation, on previews rather than screenings"

0 notes

Text

Mimetic Circulation

How to turn Gods and Heroes into Myths.

Have you ever read a book or watched a movie where there is some kind of legendary figure - let’s say a God of Destruction who wants to destroy the world, right? The writer clearly intended for this story to be a sweeping epic where the gods in their story are similar to that of actual myth and yet, this God of Destruction just feels like a guy who has godly powers? This god feels more like a character and less like a Myth.

Recently I was looking around for inspiration for more stories and ideas, and I stumbled across the theory of Mimetic Circulation. This was the generation-long game of Telephone that people have played in history, using anything from religion to folk heroes as the prop of this action. So how exactly does it work? And how can it be incorporated into your writing?

One day in Ancient Greece, somebody came up with an idea through philosophy that the world and everything must have been created by a superior race of beings, which he called the Gods. One day, when lightning cracked the sky, the people of Greece fearfully decided that it was one of the Gods, Zeus, that was angry with them. Another day, when they got a bountiful harvest, they decided through grateful assumption that it had been the Goddess of Harvest, Demeter, that had been pleased with their worship and granted the harvest to them. This is an example of how something as plain as generic gods turned into the Greek Pantheon - through the mental portrayal of the people who worshipped them. Whether through fear, joy or bewilderment, all it takes is one individual who had a new experience and the courage to speak out about it to mentally project how they see the Gods onto other people’s consciousness. Then, it begins again.

It’s this long chain of mental projection, or Mimetic Circulation, that really adds richness to any culture that has mythological ties. This is also the reason why myths aren’t being made to this day, because it takes generations of people to turn a belief into a myth. And so I hear many of you asking me just how exactly this can be used in your stories when you do not have generations of people on hand? Well you do - you have characters and a rich setting to work with. But there is another way as well.

I’ve written about H.P. Lovecraft before on this blog and it’s no surprise to anybody that he is one of my favourite writers of all time. He created his pantheon of indifferent Elder Gods, such as Yog-Sothoth, Cthulhu and Dagon, and yet we can tell these gods aren’t just tangible entities - these are nightmarish deities spawned in the mind of one man. But how? Well, that is because H.P. Lovecraft was a very insecure and unstable individual who had a very traumatic childhood and early life. On top of that, his gods kept reappearing within his fiction. An example of this is Dagon, who appeared in the story based after his name, Dagon, where he simply appeared as a sea monster of terrifying proportions. In later work, however, Dagon reappears in The Shadow over Innsmouth as more of a deity or empowered being. This happens because Lovecraft kept circulating Dagon through different stories and, because of his neuroses, fears, xenophobia and (unfortunately) racism, every time he invoked Dagon or any other of his gods within his story, he would mentally project them with a new layer of horror or revulsion. His Mythos continues to go through this Mimetic Circulation to this day every time another writer, filmmaker or artist portrays the Lovecraft Mythos in their work, adding their own layer with their own mental projection.

So how exactly is this useful? Well, it is useful especially to you fantasy writers out there who have legendary heroes or powerful gods, but they never seem to be mythical enough to the point of invincible intangibility. Instead, try to ask yourself - why is your benevolent god seen by humans as a nice god? Why do they see the evil one as a malevolent force? Gods will be seen and portrayed differently in a world bathed in peace to that of a world shrouded in fear.

I hope this was useful or even at least interesting to anybody out there reading! If you have any questions regarding fictional writing or just about anything at all really, please don’t hesitate to get in touch and I’ll truly be happy to help! Happy writing!

- CR

#hints and tips#writing help#writing advice#writing tips#hp lovecraft#lovecraft#mimetic circulation#telephone#gods#heroes#myths#mythology#fantasy#literature#fiction#religion#folklore#aetherscribe#ask me anything#ask me#ask aether#dagon#ancient greece#pantheon

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

second punic war historical fiction pov character anna As In, Dido's Sister From The Aeneid Who Was Going To Maybe Be Murdered By Lavinia And Turned Into A River About It, assimilated into the roman goddess anna perenna (there's a cool motif about circular narratives in there. like we Are trapped in meanings that circulate like blood). in silius italicus' punica she helps out hannibal or something. Elaborate On That. (and it Needs to get weird about time + epic narrative in a laviniacore way.) the other pov character is iuturna As In, Turnus' Unwillingly Immortal Sister From The Aeneid Who Was Also A River Goddess. altar in the forum romanum despite her spending the whole aeneid on the side of the war that Lost to aeneas. And They Are Lesbians. turnus has always been hannibalcoded we Know this. did you know turnus and dido are also parallels and also Cousins. the potential for evil mimetic haunted sibling relationships is almost infinite. we are trapped in meanings that circulate like blood! second punic war is the main event but if it gets weird and nonlinear i think polybius should be there also. in what is very clearly a hostage situation. also hannibal is being pursued by an army of ghosts or something idk

#the army of ghosts is Also in the punica. btw.#this is a little bit silly but also the anna / iuturna parallels have haunted me for YEARS.#punica............ 2!#did you know punica book 8 passes the bechdel test. because lavinia threatens to kill anna. feminism win#punic wars#beeps

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Taxonomies of Fandom

In the 19th century, taxonomies were a big deal. A hundred years after Linnaeus developed the system of binomial nomenclature, Darwinian natural philosophy emphasized that new and existing taxonomies should reflect the principle of common descent, giving rise to today’s system of evolutionary taxonomy.

If you’ve read the Aubrey-Maturin series of nautical adventure novels, you might be familiar with Testudo aubreii, the majestic tortoise that Stephen Maturin named after his best friend Jack Aubrey. It is an honor not lightly to be given, a sort of taxonomy as immortality: “This is Testudo aubreii for all eternity; when the Hero of the Nile is forgotten, Captain Aubrey will live on in his tortoise. There’s glory for you.” Putting a name to something makes it easier to understand and discuss; it can provide a starting point for study and for further investigation.

I’ve been thinking a lot about taxonomy lately, thanks to a few conversations I’ve had this month with people looking for expertise on fans and fan studies for final projects. I’m always happy to chat about this stuff, but sometimes I’m unexpectedly run up against the limits of my expertise: to be honest, I don’t know a lot about sports fans, or the practices of fans of massive commercial domains like Disney.

I’m interested in transformative fandom, which is a relatively small (but impactful) slice of the pie, as well as digital platforms and the ways in which youth audiences in particular utilize affordances of those platforms to express enthusiasm. I suppose I’m a fan scholar in the same way that an expert in ants is an entomologist: it’s a useful bit of nomenclature, but don’t ask them about spiders. There’s obviously a lot of benefits to specialization: but for someone who has aspirations towards the public humanities, I’m increasingly aware of my own need to have a more comprehensive overview of the different types of fans.

Over the 30 years of fan studies’ existence there have been numerous attempts to do just that: create a useful paradigm that neatly sections off fan practices into families and genii. The split between “transformational” and “affirmational” fandoms, first proposed by a pseudonymous fan in 2009 and later taken up by scholars like Henry Jenkins, is broadly handy, but problematic: it can lead to viewing “affirmational” fandom such as cosplaying, merchandise-buying, and information-collecting (such as in wikis) as purely mimetic and of lesser cultural value than “transformational” fan activities (see Hills, 2014).

That binary also ignores the large swathes of people that perform both types of fandom, or whose fan practices exist somewhere in between, or not on that axis at all; it’s also slightly outdated. In 2009, transformational fans who wrote erotica about non-canonical ships could still be safely said to be “against” canon in some way, non-sanctioned and acting transgressively out of bounds. I would say that in many cases, that is far from the case today.

Something I’m interested in is how fan practices develop and spread from one “genus” of fandom to another. (Presuming “species” is an individual fandom, and “genus” is a group of species connected by ancestry and shared practice). You see this in the phenomena in sports RPF, for example: slash fanfiction is a genre of practice developed by media fandom (TV/film fandom) in the 1970s and 80s, but it has been “adopted out” so to speak to form the nucleus of a sub-species of sports fans.

This circulation of practice is especially notable in the field of transcultural fandom (see Morimoto, 2017). Fan practices developed in the context of East Asian pop music fandom, such as chart-boosting, have made their way over to Western fandoms and communities centering on non-music media objects. Digital platforms afford this circulation, which in turn results in a blurring of boundaries between fan species and increasing difficulty in parsing out which “type” of fan someone is. Practices are contagious and amoebic. The type of sparkly fancams intially made by K-pop idol fans were adopted by Succession stans.

Like the animal kingdom, there’s just so much going on. To say nothing of what was going on. Which types of fans have gone extinct? Which modes of interacting with media are now archaeological artifacts, thanks to the shifting relationality of the apparatus of cultural production with respect to audiences?

I think that especially in a time when many groups who might not explicitly consider themselves “fans” have freely taken up digital practices developed and popularized in fandom spaces, investigations into the origins and classifications of fans and fan culture has the potential to provide broader behavioral insights into online communities.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In Defense of the Poor Image” - Hito Steyerl

“On the one hand, [the poor image] operates against the fetish value of high resolution. On the other hand, this is precisely why it also ends up being perfectly integrated into an information capitalism thriving on compressed attention spans, on impression rather than immersion, on intensity rather than contemplation, on previews rather than screenings.” ー Hito Steyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image”

In her essay titled In Defense of the Poor Image, Hito Steyerl situates herself within the contemporary digital revolution of semiocapitalism, where means of image production and image value exist within a visual hierarchy based on the quality of its resolution. However, Steyerl argues that the poor image opposes the value hierarchy of high resolution images by establishing its own economy. Incidentally, both the poor and rich image exist within the same system of commodification; as Steyerl writes, “poor images are thus popular images”, in that they operate on a democratic level. They allow access and participation on a mass scale uninhibited by the confines of institutional exclusivity. It functions as a rejection of the “rich” image by purposefully denying the value of high resolution. Like its name suggests, a poor image is inherently substandard. It’s own pictorial quality is defined by its material atrophy. As the poor image constantly cycles through the process of reupload, download, edit, share, copy, paste, it frees itself from the value of high resolution by instead inheriting a form of cult value, influenced by its distribution into the cultural aether. Steyerl identifies that “poor images are poor because they are not assigned any value within the class society of images—their status as illicit or degraded grants them exemption from its criteria. Their lack of resolution attests to their appropriation and displacement”. Once it enters the network of popular image, the poor image is able to redefine value through social capital, a cultural currency defined through virality, influence and clout (John Lorinc, "Your Kids, The Influencers." Corporate Knights 14, no. 2 (2015): 50-53.). It is iterative, responding to its environment through mimetic evolution. A poor image becomes an open invitation for cultural producers, since its inherent fragility allows for continual remix and reproduction. As such, it becomes a transgressive bastardization of the original image, displacing itself from the hierarchy of high art images. The poor image, then, is a transformative copy propelled by the circuits of demand that is stimulated by its own popularity.

All these qualities, however, are precisely what grant the poor image its seductive condition; the poor image is still an object of cultural production, within the informational image economy. In separating itself from the value of high resolution, the poor image is commodified through its accessibility. Rather than being sequestered by the gatekeepers of the rich image, its affinity for rapid distribution and potential for volatility are fetishized by markets that operate in the exchange of culture and information. As Steyerl states, “the networks in which poor images circulate thus constitute both a platform for a fragile new common interest and a battleground for commercial and national agendas. They contain experimental and artistic material, but also incredible amounts of porn and paranoia”. I think this is most evident in the spheres of digital culture, where markets operate in a “meme economy”. The meme has become synonymous with the poor image, in that it exists within the same structure of production and commodification. Like the poor image, its visual repertoire hinges on the bastardization of the original image, which lives on and degrades through the process of iteration, transgression, and transformation. As a cultural artifact, it serves the same function of communication that reflects the ideas of popular culture. And just like the poor image, a meme’s value lies in its inherent trashiness; a meme is characterized by its irreverence to labour and quality, which grants it the capacity for virality and spread (Yvette Granata, "Meme Dankness: Floating Glittery Trash for an Economic Heresy." In Post Memes: Seizing the Memes of Production, edited by Bown Alfie and Bristow Dan, 251-76. Punctum Books, 2019. pp. 259-260). Its status as mutable and proneness to appropriation is what fetishizes a meme within the image economy. A meme’s relationship to democracy and popularity are what give it political clout.

As Yvette Granate wrote in her essay "Meme Dankness: Floating Glittery Trash for an Economic Heresy", “[a meme is] free marketing, free branding, free labor. This is the economic normality of capitalist appropriation—but now mixed with the weird image board flow of the Internet meme” (Granata, 267). As a poor image, a meme is able to be seen by many, and its fleeting temporality takes advantage of the condition of its environment, in that its velocity, intensity and impressionability seduce its audience; a meme opposes the value hierarchy of resolution, yet simultaneously plays into the system of informational capitalism.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

the influencerization of everything

From this LARB essay by Sarah Brouillette about Caroline Calloway:

We see in her case a set of conditions that are likely to intensify as the publishing industry continues to struggle: toward convergence with social media culture, the self-branding industry, gig work in the form of self-publishing, with a growing army of hungry creatives vying for attention. They are serving a new kind of consumer, too — a topic for another piece — who is drawn less to physical paperbound books and more to free content with options added, like that $100 personal phone call, and to the kinds of subscription-based services that reduce the risk of disappointment if you don’t get what you paid for.

For a long time now, I’ve argued that social media incentivize (and then ultimately compel) the production of the self as a commodity — they reconstitute self-expression as perpetual advertisements for the self, demonstrations of one’s human capital, as well as one’s capacity to leverage attention and, as Brouillette emphasizes, the promotional labor of others. The rise of influencers is indicative of the normalization of these practices, and a harbinger — it seems like most forms of work will eventually be influencerized, and workers will have to leverage their personality, their “personal brand,” to get work or to perform it up to managerial expectations. Taylor Lorenz points out in this piece how this has happened in journalism.

But the other side of the coin that Brouillette gestures toward above seems just as important: how influencerization has changed consumption, how it reflects and drives a destabilization of the object of consumption. In other words, once static objects (books, etc.) become “content” — fluid, upgradable, networked, subject to spontaneous (or spurious) customization, directly social in that one can immediately recirculate it, comment on it, argue about it, “react” to it with a button, and so on.

It may become increasingly strange to consume objects we cannot immediately imprint with some avatar of ourselves, that we can’t immediately augment (by paying extra or performing some kind of labor). It’s not “interactivity” per se, because it is not reciprocal and it is mostly systematized and delimited by the interfaces through which media is consumed. But it is a matter of manifesting “influence.” No kind of consumption can occur outside the awareness of the asymmetries of attention that directly govern it.

When one thinks of, say, free-to-play games, it’s easy to construe their constant attempts to milk money from you as annoying. But it may be more accurate to think of that as part of the entertainment, part of the means for subjectivizing the player, for making them feel as though they are being paid attention to, being recognized.

This is how I understand the “new kind of consumer” Brouillette mentions. The vicarious fantasy inherent in consumption can be supplemented by more direct forms of engagement; consumers no longer need to be trained how to enjoy vicarious, imaginative experiences in the same way they used to. The emulative, mimetic aspects of consumption are more straightforward now, given the channels consumers have to immediately produce their responses and see what reactions they attract.

Every commodified experience concretizes some aspect of the “influence” that has produced and circulated it, and the process of consuming it is now a matter of tapping into that and trying to realize it somehow for oneself.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ostarine.

Sarm.

Content

Are There Any Type Of Negative Effects To Collagen Supplements?

Exactly How Is The Examination Performed?

Where To Acquire Sarms Online?

09rik Peptide.

Find Similar Products By Tag.

Due to the means GW works it is risk-free to think it was all or mainly LBM. Because of the method Cardarine works users as well as animal research studies showed that Cardarine is related to substantial reduction in body fat. Where Cardarine or GW50515 ends up being exceptionally intriguing is that PPARD activation boosted mitochondrial biogenesis in the muscle mass, which can redesign your muscle mass cells! In research studies of qualified and inexperienced mice, Cardarine triggered quickly shiver muscle fiber to transform to slow down jerk muscular tissue fibers. As a result of this Cardarine is often called an exercise mimetic as only workout can normally make these modifications to your metabolism and fiber structure. At simply 1mg daily for 3 weeks a medical test showed a typical gain of 1.21 kg in LBM which is almost 1 extra pound of LBM per week which is definitely ridiculous considering the time framework and also the fact that they were not also training. Unlike Ostarine, LGD-4033 does not appear to enhance liver enzymes however like Ostarine it did negatively impact great cholesterol levels.

In peptides-uk.com’s free BPC157 Switzerland as stage 2 trials which lasted 12 weeks 268 patients with reduced HDL degrees were offered 2.5,5,10 mg daily. During this moment good cholesterol enhanced by 17% as well as poor cholesterol was minimized by 7%. Bodyweight likewise boosted usually 1.3 kg nevertheless a LBM vs fat mass analysis was not completed.

Exist Any Negative Effects To Collagen Supplements?

However it is highly likely that the adverse effects at this dose would probably be the same or even worse than testosterone. In recent times, steroid usage has been expanding throughout the UK - not only among gym-goers and bodybuilders, as you would certainly expect, however in certain specialist areas, too. peptides-uk information BPC157 Sweden ideas 's why, in mid-2019, we introduced the initial UK-based hair steroid testing solution, aiding family members legal representatives as well as work environments alike to stamp out the issues brought on by the psychological and emotional negative effects of anabolic steroids. Today tried heavy shoulder presses, and got a brand-new individual finest. My prevoius was 80 kg x 1 associates, currently I handled 80 kg x 3 associates conveniently.

Typically when I stop with my steroids, my toughness reduces as well as I am reducing weight. This time around I lost weight on the scale at the very least however aesthetically it really did not resemble it as well as I preserved my toughness. Finally, the outcomes of the present research revealed useful effects of both SARMs on the muscle mass framework and also metabolic rate in ovariectomized rats.

How Is The Test Executed?

It is worth discussing that taking SARMs is NOT as reliable as steroids. If they were then everybody utilizing steroids would certainly have stopped and switched over a very long time earlier. Having stated this, SARMs are taken at a much reduced dosage than steroids/testosterone. A normal Ostarine dosage is 20mg for 8 weeks yet a typical 8-week testosterone dosage would certainly be anywhere between mg per week, so if Ostarine was taken at a similar dosage would certainly similar testosterone results happen?

The truth is that results produced by sarms are smaller than the results of utilizing traditional steroids but they are most definitely safer. With each brand-new version, sarms are coming to be more efficient, so they might eventually produce even more powerful outcomes than traditional steroids. I obtained it for myself, not as much to be gaining mass yet basically for after steroid cycle.

Where To Get Sarms Online?

" I am considering my legal alternatives, in terms of where I stand as well as what I can do. That could cost me a great deal of cash and I'm not sure I can manage to do that. They are playing with individuals lives and also credibilities, and also it's incorrect. Building muscular tissue and also bone toughness would profit a UFC competitor and also as formerly discussed, that is what ostarine does. Two Russian UFC boxers, Ruslan Magomedov and also Zubaira Tukhugov, likewise lately checked positive for ostarine. In their instances, the UFC and USADA did not think that supplement contamination was a valid explanation, as well as provided both with 2 year restrictions.

youtube

SARM piling can lead to cutting fat at the same time while developing muscular tissue, according to unscientific research study on SARMs forums. For example, LGD-4033 and also S-23 have been provided to balance out the bulking results of testolone.

09rik Peptide.

He sent out 20 products in to be tested and also every one came back unfavorable for ostarine. I am thinking that also if it was that item or an infected supplement, or a contaminated batch, after that the odds are reduced of it coming back favorable. ' You ought to watch out for ostarine's numerous synonyms, consisting of MK-2866, enobasarm, -3-( 4-cyanophenoxy)- N- [4-cyano-3-phenyl] -2- hydroxy-2-methylpropanamide, and also GTx-024 on supplement labels'. The objective of this research is to check the safety of GSK in males and females with COPD and also muscle weakness.

Fish Collagen Peptides Market by Top International Players, Segmentation, Industry Growth, Research Report, Regional Overview Forecast to 2027 GELITA AG, Amicogen, Nitta Gelatin, NA Norland Products, Rousselot - Farming Sector

Fish Collagen Peptides Market by Top International Players, Segmentation, Industry Growth, Research Report, Regional Overview Forecast to 2027 GELITA AG, Amicogen, Nitta Gelatin, NA Norland Products, Rousselot.

Posted: Tue, 05 Jan 2021 18:26:13 GMT [source]

LGD-4033 as well as S-4 have been stacked for their impacts on weight loss, as have LGD-4033 and also SR9009 Stenabolic and also GW501516. Testolone is shown in studies to enhance lean muscle cells without increasing fat mass, and also to be extremely bioavailable in its oral supplement form. It also enhances speed and endurance throughout exercise, which can aid with making faster muscle gains. It assists to improve muscle stamina, significantly delays the onset of exhaustion. There is additionally a blurred line in between sporting supplements as well as nutritional supplements, which can make law challenging. In July last year, a South African supplement maker safeguarded its item, after a competitor it funded returned an AAF from one of its products. Biogen sponsors Extreme Combating Champion competitor Demarte Pena, that was issued with a lecture after an AAF for testosterone was mapped back to 'Testoforte for Stamina', produced by Biogen.

Discover Similar Items By Tag.

Both OS and LG boosted muscular tissue vascularization, as well as OS had a stronger impact than LG on vascularization. On the other hand, LG possessed much more effect on muscle metabolic enzymes by raising LDH and CS tasks, whereas OS entirely caused a high CS task. A hypertrophic effect on muscular tissue fiber size was not observed under either SARM therapy. In addition, the uterotrophic impact of both of the examined SARMs at higher does might be a limitation for their application. All rats obtained a soy-free rodent diet (ssniff Spezial Diät GmbH, Soest, Germany) throughout the experiment. OS and also LG were supplied with the soy-free diet (ssniff Spezial Diät GmbH). The staying food in the cage was evaluated once a week to determine the ordinary daily food intake of a rat by separating these information by days in between the considering and variety of rats in a cage.

In Experiment II, intramuscular fat web content was established in the quadriceps femoris muscular tissue in Non-OVX, OVX, as well as OVX+LG 4 teams. In both experiments, a reduced dosage of 0.04 mg/kg BW/day was computed based upon a human-equivalent dosage enough for improvements of complete lean body mass and also physical feature. To check out dose-dependent impacts, 10-fold as well as 100-fold does were made use of. SARMs and also prohormones are 2 types of supplements used for bodybuilding and also getting a ripped, reduced look. While they both result in muscle gains, they're entirely different compounds with entirely different biochemical impacts. Because some SARMs are best for bulking as well as others are shown to be particularly reliable for reducing, they're sometimes integrated, or piled, in research study studies.

The study will inspect the results of GSK on muscle mass assessed as adjustments in leg strength, muscle mass, as well as functional steps such as walking capacity. https://peptides-uk.com/bpc157/canada/ was established to enhance muscle mass size, reduce fat, and increase testosterone degrees. Below at Top Body Nutrition, we are an organization with body home builders in mind, providing a big choice of supplements for a variety of various objectives. In this area, you will certainly find both SARMS, as well as products that are similar to SARM products. In-Vitro research studies reveal that RAD-140 has a much higher binding affinity for the androgen receptor than testosterone and also dihydrotestosterone. It likewise revealed that it was highly selective in skeletal muscle as well as bone, with just a weak hostile effect in androgenic cells. RAD-140 does likewise have an extremely weak interaction with progesterone as well as estrogen because of it not responding with any kind of various other steroid hormone receptors to any type of significant degree.

Assimilation of inline real-time evaluation, such as UV/Vis spectroscopy and also our Variable Bed Circulation Activator into the circulation after the activator authorization prompt identification of any type of non-standard combining events.

This decreases the cost and quantity of waste generated by the synthesis.

This allows the user to identify as well as optimize tough coupling events during little scale syntheses.

The peptide synthesis can then be scaled up making use of the optimised series.

This much more efficient combining additionally greatly lowers the demand for extras of reagent.

As reported by The Sports Integrity Campaign, Gordon Gilbert also faces the very same issue with the same supplement. " These firms require to be frightened to place things like ostarine into their items", he suggests.

" A couple of UFC competitors, who are 12 months into their 2 year bans for ostarine, messaged me", he explains. " One is rather a renowned fighter, as well as he vouched on his children life that he had not taken ostarine.

Are Peptides safe?

They are safe to use but educated prescribing is vital. Like any medication or treatment, peptides can have risks, side effects and contradictions. For example, some may be avoided if the patient has a history of melanoma.

The ordinary everyday dosage of OS and also LG was calculated based upon the everyday food intake and the mean BW in the cage on the particular week. After 13 weeks post-OVX, all animals were euthanized under CO2 anesthesia. Blood product was gathered for further evaluation of creatine kinase as a pen of muscle damages. The gastrocnemius muscular tissue, soleus muscular tissue, as well as longissimus muscular tissue were drawn out. The GM as well as SM were considered and also all muscle mass were frozen in fluid nitrogen as well as saved at − 80 ° C up until more analyses. Either left or right muscle mass were made use of randomly in either histological or enzyme analyses.

Webster states that he spent his life cost savings trying to find the resource of the ostarine, which he argues might have been due to contaminated supplements or salt tablet computers. ' The UKAD expert testified that the amount of ostarine located in my body was the lowest that has actually ever been reported (4 nanograms/ml) which would certainly make it near impossible to establish the source', reads his declaration.

#BPC157 EU#BPC157 Europe#information BPC157 EU#information BPC157 Europe#EU BPC157 how does it work#Europe BPC157 how does it work

1 note

·

View note

Text

Karp and Thiel have both described these controversial contracts using the language of “nation” and “civilization.” Confronted by critical journalistic coverage (Woodman 2017, Winston 2018, Ahmed 2018) and protests (Burr 2017, Wiener 2017), as well as internal actions by concerned employees (MacMillan and Dwoskin, 2019), Thiel and Karp have doubled down, characterizing the company as “patriotic,” in contrast to its competitors. In an interview conducted at Davos in January 2019, Karp said that Silicon Valley companies that refuse to work with the US government are “borderline craven” (2019b). At a speech at the National Conservatism Conference in July 2019, Thiel called Google “seemingly treasonous” for doing business with China, suggested that the company had been infiltrated by Chinese agents, and called for a government investigation (Thiel 2019a). Soon after, he published an Op Ed in the New York Times that restated this case (Thiel 2019b).

However, Karp has cultivated a very different public image from Thiel’s, supporting Hillary Clinton in 2016, saying that he would vote for any Democratic presidential candidate against Trump in 2020 (Chafkin 2019), and—most surprisingly—identifying himself as a Marxist or “neo-Marxist” (Waldman et al. 2018, Mac 2017, Greenberg 2013). He also refers to himself as a “socialist” (Chafkin 2019) and according to at least one journalist, regularly addresses his employees on Marxian thought (Greenberg 2013). On one level, Karp’s dissertation clarifies what he means by this: For a time, he engaged deeply with the work of several neo-Marxist thinkers affiliated with the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt. On another level, however, Karp’s dissertation invites further perplexity, because right wing movements, including Trump’s, evince special antipathy for precisely that tradition.

[...]

As a case study to demonstrate the usefulness of his modified concept of jargon, Karp takes up a notorious episode in post-wall German intellectual history: a speech that the celebrated novelist Martin Walser gave in October 1998, at St. Paul’s Church in Frankfurt. The occasion was Walser’s acceptance of the 1998 Peace Prize of the German Book Trade. The novelist had traveled a complex political itinerary by the late 1990s. Documents released in 2007 would uncover the fact that as a teenager, during the final years of the Second World War, Walser joined the Nazi Party and fought as a member of the Wehrmacht. But he first became publicly known as a left-wing writer. In the 1950s, Walser attended meetings of the informal but influential German writer’s association Gruppe 47 and received their annual literary prize for his short story, “Templones Ende”; in 1964 he attended the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, where low ranking officials were charged and convicted for crimes that they had perpetrated during the Holocaust. In his 1965 essay about that experience, “Our Auschwitz,” Walser insisted on the collective responsibility of Germans for the horrors of the Nazi period; indeed he criticized the emphasis on spectacular cruelty at the trial, and in the media, to the extent that this emphasis allowed the public to maintain an imaginary distance between themselves and the Nazi past (Walser 2015, 217-56). Walser supported Social Democratic Party member Willy Brandt for Chancellor and even joined the German Communist Party during that decade. By the 1980s, however, Walser was widely perceived to have migrated back to the right. And when he gave his speech “Experiences Composing a Sermon” on the sixtieth anniversary of Kristallnacht, he used the occasion to attack the public culture of Holocaust remembrance. Walser described this culture as a “moral cudgel” or “bludgeon” (Moralkeule).

“Experiences Composing a Sermon” adopts a stream of consciousness, rather than argumentative, style in order to explain why Walser refused to do what he said was expected of him: to speak about the ugliness of German history. Instead, he argued that no further collective memorialization of the Holocaust was necessary. There was no such thing, he said, as collective or shared conscience at all: conscience should be a private matter. Critics and intellectuals he disparaged as “preachers” were “instrumentalizing” and “vulgarizing” memory, when they exhorted the public constantly to reflect on the crimes of the Nazi period. “There is probably such a thing as the banality of good,” Walser quipped, echoing Hannah Arendt (2015, 513). He did not spell out what ends he thought that these “preachers” aimed to instrumentalize German guilt for. He concluded by abruptly calling on the newly elected president Roman Herzog, who was in attendance, to free the former East German spy, Rainer Rupp, from prison. Walser’s speech received a standing ovation—though not, notably, from Ignatz Bubis, then the president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, who was also in attendance. The next day, in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Bubis called the speech an act of “intellectual arson” (geistiges Brandstiftung). The controversy that followed generated a huge amount of debate among German intellectuals and in the German and international media (Cohen 1998). Two months later, the offices of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung hosted a formal debate between the two men. It lasted for four hours. FAZ published a transcript of their conversation in a special supplement (Walser and Bubis 1999).

[...]

I asked at the beginning of this paper what beliefs Karp shares with Peter Thiel and what their common commitments might reveal about the self-consciously “contrarian” or “heterodox” network of actors that they inhabit. One answer that Aggression in the Life World makes evident is that both men regard the desire to commit violence as a constant, founding fact of human life. Both also believe that this drive expresses itself in social forms like language or group structure, even if speakers or group members remain unaware of their own motivations. These are ideas that Thiel attributes to the work of the eclectic French theorist René Girard, with whom he studied at Stanford, and whose theories of mimetic desire, scapegoating, and herd mentality he has often cited. In 2006 Thiel’s nonprofit foundation established an institute to promote the study of Girard and support the further development of mimetic theory; this organization, Imitatio, remains one of the foundation’s three major projects (Daub 2020, 97-112).

The text that Karp chose to analyze, as his case study, also shares a set of concerns with Thiel’s writings and statements against campus multiculturalism and political correctness; Walser’s speech became a touchstone of debates about historical memory in Germany, in which the newly imported Americanism politische Korrektheit circulated widely. In his dissertation, Karp does not celebrate Walser’s taboo speech in the same way that Thiel and his associates have sometimes celebrated violations of speech norms.[11] However, he does assert that jargon, and the unconscious aggression that it expresses, plays a role in the formation of all social groups, and refrains from evaluating whether Walser’s jargon was particularly problematic. Of course, the term “jargon” itself became a commonplace during the U. S. culture wars in the 1980s and 1990s, used to accuse academics and university administrators who purported to be speaking for vulnerable populations of in fact deploying obscure terms to aggrandize themselves. Thiel and his co-author David O. Sacks devote a chapter of The Diversity Myth to an account of how the vagueness of the word “multiculturalism” enabled activists and administrators at Stanford to use it in this manner (1995, 23-49). The idea that such terms express ressentiment and a will to power is consistent with the theoretical framework that Karp went on to develop.

I think this piece is trying to tell a story but honestly I don’t know that that story is.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote