#or maybe Storyteller's should be a jellyfish

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

One last look at the sketch before I muck it up ink and color it in! Dancer's mug is supposed to have a holly design on it. ^_^; I tried to make it look like a decor style you'd see in Sky. Might fix it after inking.

Little extra thing I started as a comic, but might leave as is, and ink and color later as well.

#fanart#sketch#wip#Sky: Children of the Light#Sky: CotL#That Sky Game#Season of Performance#Forgetful Storyteller#Modest Dancer#they sure as hell ain't gonna forget that kiss I tell ya hwat#I thought just a diamond shape on the mugs would be a little boring so manta and holly designs#or maybe Storyteller's should be a jellyfish#based on their canon backstory where their first role in a play was a jellyfish#mmmm making me want some hot chocolate with marshmallows now

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: The Northern Caves

Author: Vladimir Nabokov

Rating: 3/5 stars

One of those books that's "okay" in the sense that I enjoyed reading it a lot and it is of the class of things I "endorse" -- in some vague sense of "this is a book I would, if I were a writer, write" -- but which somehow doesn't feel like a work of art in any other way, in a way that is maybe just "I am OK with the fact that this is the sort of thing I would like to read"

In case it's not obvious, I don't like Vladimir Nabokov much

The Northern Caves features what is, perhaps, a typical Vladimir Nabokov experience -- a novel which is not about anything but which, as the title suggests, takes place in a cave in northern Scotland, and seems to contain no real plot in the traditional sense, and has little continuity across its 1.4 million words. Rather, every chapter begins with a lengthy description of a natural phenomenon, and sometimes goes on to present various speculations about that natural phenomenon, although not always directly related to anything said in the "main story." The chapters can be read in any order, with little or no sense of linearity, although of course it would be very strange if one did.

This is a style which is (a) very different from anything else, and (b) perfectly in keeping with the subject matter. The novel is about the experience of finding oneself in a large dark cave, far from civilization, with only the dim light from distant sources to illuminate the space around you. You begin with a detailed physical description -- the sensation of feeling yourself descend into the cave, the sensation of feeling yourself emerge into the darkness of the cave, the sensation of your eyes beginning to adjust to the gloom -- and soon afterward you come across a strange creature in that darkness, a pale blob with strange spiky protrusions. It is very difficult to describe just how different this scene, this very specific experience, is, but it is very similar to things one has seen and felt and thought many times before -- things which you will not find described anywhere else, which you will find difficult to comprehend if you haven't had them, and will often find to be "very far from ordinary," as one will have many times before as well. In particular, as the cave becomes increasingly dark, and the strange creatures become more distinct, they begin to resemble things that we think of when we imagine caves in the depths of the sea: jellyfish and sea spiders.

This is one of the most remarkable novelistic innovations I've ever encountered -- and I am sure that if I had been asked to "write a book which was mostly like Vladimir Nabokov" it would have sounded impossible -- but one is forced to wonder if it would have been possible to imagine it in the first place, if it hadn't been done first. (Nabokov is not a very original writer and he is not a very original storyteller either, but I don't think there has been anything quite like this novel -- I wonder how many novels have had this kind of structure.) If one has only read a dozen or so Nabokov novels (I certainly have not), one might have to try to fit it into the pattern established by earlier Nabokov books, but one wouldn't know it was really a Nabokov novel at all. I can think of many other novelistic ideas that have been presented in such a way: Umberto Eco's The Prague Cemetery in The Prague Cemetery is very similar, as is James Joyce's The Arming of Turandot. (But Nabokov is by far the only novelist I know who has a novel that is like this.)

At first I thought I should try reading another Nabokov novel soon, just to get some kind of perspective on what kind of experience I'm having here. Then, the more I thought about it, the more I started to feel that I didn't want to read another Nabokov novel. His work is difficult, even if his novels are relatively short. I am still not entirely sure what the appeal is, at a basic level: what exactly is it that I find so appealing? That I know, but I don't exactly want to rehash it on this review. (I tried reading a couple of his nonfiction books, such as Pale Fire -- the experience there was similar but of course not nearly as "good".) I did once read Nabokov's book "The Gift" about the life of an artist who creates realistic paintings, and while I enjoyed it as a curiosity, I didn't really want to take another look at a life so removed from my own. (I can still remember some of those paintings with vividness: this one, from the poem by W. B. Harkness.) So I think I'm going to take some time off for now -- I enjoyed this book a great deal, and I will be reading some good work soon, but I have had enough, if I'm going to keep doing this for a long time. But if anyone else is thinking about picking this book up, I definitely think you should.

Further reading: Vladimir Nabokov, "Dumb," in Pale Fire.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character analysis: Vivienne de Fer (Dragon Age Inquisition)

So, if you’ve wondered where I popped off to the past two months or so, I’m going to give you an answer - I finally bought Dragon Age Inquisition (legit on my gaming wishlist since its 2014 release) and I’ve been obsessed with it ever since.

The main draw to this game however, isn’t so much the gameplay (if you want a game that feels similar but has better gameplay - Assassin’s Creed Odyssey is what you’d want instead), but the storytelling and particularly the character development are top notch. All nine companions are fascinating and fleshed out in such a realistic manner I’m still gasping in awe on my fifth playthrough. Thus, a post on it is in order. It’s a bit different from my usual content, but don’t let that discourage you - clearing my head from Dragon Age will allow me to let Eurovision back in and continue my unfinished 2020 ranking. In this post, I will be analyzing one of DAI’s most interesting characters - none other than Madame de Fer herself, Vivienne. Now, I’m under the impression that this is a rather unpopular opinion but I absolutely love Vivienne. And no, I won’t apologize for it. As a Templar-thumping elitist with a icy, sardonic demeanor the sheer ‘Idea Of A Vivienne’ is meant to make your head spin. Dragon Age has always been a franchise in which mages are a socially surpressed group and to be confronted with a socially confident enchantress who likes Templars and seemingly supports the social shunning out of her own ambition is the walking embodiment of flippancy.

and yet, I feel a lot of sympathy for Vivienne.

Yes, she’s a bitch. She knows she’s one and she’s a-ok with it. I won’t argue with that. Sadly, the “Vivienne is a bitch” rhetoric also drastically sells her short. Vivienne is highly complex and her real personality is as tragic as it is twisted.

Madame de Fer

So let’s start with what we are shown on the surface. Vivienne is a high-ranking courtier from an empire notable for its deadly, acid-laced political game. She seemingly joins the Inquisition for personal gain, to acrue reputation and power, and eventually be elected Divine (= female pope) at the end of the game. She presents herself as a despicable blend of Real Housewife, Disney Villain, and Tory Politician, all rolled into one ball of sickening, unctuous smarm. Worse, the Inquisitor has no way to rebuke Vivienne’s absurd policies and ideas. You can’t argue with her, convince her to listen to your differing viewpoints or even kick her out the Inquisition. She has a way with words where she can twist arguments around in such a fashion that she lands on top and makes the other person look like the irrational party.

“Thus speaks the Inquisitor who has made so many mature and level-headed choices so far. Such as releasion malcontents upon the population without safeguards to protect them should they turn into abominations. Very wise. I rearranged some furniture. Lives aren’t thrown into jeopardy by my actions. Perhaps a little perspective is needed.”

She’s Cersei Lannister on creatine, Dolores Umbridge on motherfucking roids. If you look at merely the surface, then yes, Vivienne looks like the worst person ever created. I love a good anti-villainess however, and she’s definitely one.

Yet, she never actually does anything ‘evil’? Yes, she is ‘a tyrant’ as a Divine, but 1) the person saying this is Cassandra, whose dislike for mage freedom is only matched by her dislike of being sidelined 2) Divine Vivienne isn’t bad to mages either? (hold that thought, I’ll get to it). She never actually sabotages the Inquisition, no matter how low her approval with the Inquisitor gets. She never attempts to stop them, no matter how annoyed she is. She’s one of the most brutally honest companions in the cast, in fact. (It always surprises me people call her a ‘hypocrite’ - you keep using that word and it doesn’t mean what you think it means.) The ‘worst’ display of character is when she attempts to break up Sera and the Inquisitor and even then - are we going to pretend Sera isn’t a toxic, controlling girlfriend with a huge chip on her shoulder? I love Sera, but come on.

Vivienne is a character where the storytelling rule of Show, Don’t Tell is of vital importance. The Orlesian empire is an empire built around posturing and reputation. Nobody really shows their true motivations or character, and instead builds a public façade. It’s like how the Hanar (the Jellyfish people) in Mass Effect have a Public name they use in day-to-day life, and a Personal Name for their loved-ones and inner circle. Vivienne’s ‘Public Visage’ is that of Madame de Fer - this is the Vivienne who openly relishes in power, publicly humiliates grasping anklebiters with passive-aggressive retorts, the woman who is feared and loathed by all of Orlais, and this is the Face you see for most of the game.

The real beauty of Vivienne’s character and the reason why I love her as much as I do (which is to say - a LOT) are the few moments when - what’s the phrase DigitalSpy love so much - Her Mask Slips, and you get a glimpse of the real woman underneath the hennin.

This is the Vivienne who stands by you during the Siege of Haven and approves of you when you save the villagers from Corypheus’s horde.

This is the Vivienne who comforts you when you lament the losses you suffered.

This is the Vivienne who admires you for setting an example as a mage for the rest of Thedas.

This is the Vivienne who worries about Cole’s well-being during his personal quest, momentarily forgetting who or what he is.

This is the Vivienne who, when her approval for the Inquisitor reaches rock bottom, desperately reminds him of the suffering mages go through on a day-to-day basis because of the fear and hatred non-mages are bred to feel towards them and how this can spiral into more bloodshed without safeguards.

This is the Vivienne who shows how deep her affection for Bastien de Ghislain truly is, by bringing you along during his dying moments. I love this scene btw. This is the only moment in the entire game where Vivienne is actually herself in the presence of the Inquisitor - needless to say, I consider anyone who deliberately spikes her potion a motherfucking psychopath ^_^)

“There is nothing here now” fuck I *almost* cried at Vivienne, get out of my head BioWare, this is WRONG -- people who delude themselves this is an irredeemable character.

So, who is Vivienne really?

Understanding Vivienne requires recognizing that the mask and the real woman aren’t the same person. I think her relationship with Dorian is the prime example of this. I love the Vivienne/Dorian banter train, obviously - an unstoppable force of sass colliding with an unmovable wall of smarm is nothing short of a spectacle. However, there’s more to it than their highly entertaining snipes. As the incredibly gifted son of a magister, Dorian represents everything Vivienne should despise, and should be a natural enemy to her. And yet, she doesn’t and he isn’t.. Their gilded japes at each other are nothing more than verbal sparring, not dissimilar to how Krem and Iron Bull call each other names when they beat each other with sticks. In what I think is one of the most brilliantly written interactions between characters in DAI, I present Vivienne’s reaction when the Inquisitor enters a romance with Dorian:

Vivienne: I received a letter the other day, Dorian. Dorian: Truly? It's nice to know you have friends. 🙄 Vivienne: It was from an acquaintance in Tevinter expressing his shock at the disturbing rumors about your... relationship with the Inquisitor. Dorian: Rumors you were only too happy to verify, I assume. 🙃 Vivienne: I informed him the only disturbing thing in evidence was his penmanship. 🙂 Dorian: ...Oh. Thank you. 😳 Vivienne: I am not so quick to judge, darling. See that you give me no reason to feel otherwise.

Madame de Fer can never be seen directly expressing approval to a relationship between the Herald of Andraste and an ‘Evil’ Tevinter ’Magister’. By this subtle, subtle conversation, Vivienne indirectly tells Dorian that she considers him a good match for the Inquisitor and approves of the romance. It’s one of those reasons why I could never truly dislike Vivienne - between the layers of elegant poison lies a somewhat decent woman who never loses sight of the bigger picture. Not a good person maybe, but not one without some redeeming qualities.

The crux of Vivienne’s personality is that she, like all DAI companions, is a social outcast. She’s a mage in a fantasy setting where mages are psionically linked to demons, and grew up in a country where the majority religion has openly advocated the shunning and leashing of mages (’Magic exists to serve man’ - the Chantry is so, so vile in this game.). Vivienne’s “gift” was discovered so early in her life that she can barely remember her parents. Vivienne grew up in a squalid boarding school, learning from a young age that she’s dangerous and her talents need to be tamed and curbed. She is also terrified of demons, as her banters with Cole point out:

Cole: You're afraid. You don't have to be. Vivienne: My dear Inquisitor, please restrain your pet demon. I do not want it addressing me. Inquisitor: He's not doing any harm, Vivienne. Vivienne: It's a demon, darling. All it can do is harm. Cole: Everything bright, roar of anger as the demon rears. No, I will not fall. No one will control me ever again. Cole: Flash of white as the world comes back. Shaking, hollow, Harrowed, but smiling at templars to show them I'm me. Cole: I am not like that. I can protect you. If Templars come for you, I will kill them. Vivienne: Delightful. 😑

Vivienne’s Harrowing is implied to have been such a traumatizing event to her that she’s developed a pavlovian fear of demons ever since. (Hence her hostility towards Cole.). Vivienne is fully aware of the inherent dangers of magic, and projects this onto all other mages.

Besides, given how Dragon Age has a history with mages doing all sorts of fucked up shit, ranging from blood magic, murder, demonic possession and actual terrorism (yes, *ElthinaBITCH* had it coming, but let’s not pretend like Anders/Justice was anything other than a terrorist), Vivienne’s policies of controlled monitoring and vigilance are actually significantly more sensible than the options of ‘unconditionally freeing every mage all over Thedas’ and ‘reverting back to the status quo before the rebellion’. They’re flawed policies, obviously. When Vivienne says “mages” she pictures faceless silhouettes foremost and not herself. Regardless, unlike Cassandra and Leliana, Vivienne is aware of the fear others harbour for her kind, and how hard it is to overcome such perceptions.

Additionally, Vivienne’s a foreigner. She is an ethnic Rivaini, a culture associated with smugglers and pirates (Isabela from DAO and DA2 is half-Rivaini). This adds an additional social stigma, again pointed out by Cole:

Cole: Stepping into the parlor, hem of my gown snagged, no, adjust before I go in, must look perfect. Vivienne: My dear, your pet is speaking again. Do silence it. Cole: Voices inside. Marquis Alphonse. Cole: "I do hope Duke Bastien puts out the lights before he touches her. But then, she must disappear in the dark." Cole: Gown tight between my fingers, cold all over. Unacceptable. Wheels turn, strings pull. Cole: He hurt you. You left a letter, let out a lie so he would do something foolish against the Inquisition. A trap. Vivienne: Inquisitor, as your demon lacks manners, perhaps you could get Solas to train it.

This is the only palpable example of the casual racism Vivienne has to endure on a daily basis - Marquis Alphonse is a stupid, bigoted pillowhead who sucks at The Game, but remember - Vivienne only kills him if the Inquisitor decides to be a butthurt thug. She is aware that for every Alphonse, there are dozens of greasy sycophants who think exactly like he does, and will keep it under wraps just to remain in her good graces.

Finally, there’s the social position Vivienne manufactured for herself, which is the weak point towards her character imo. Remember, this woman is a commoner by birth. She doesn’t even have a surname. Through apparently sheer dumb luck (or satanic intervention) she basically fell into the position of Personal Mage to the Duke of Ghislain. Regardless, ‘Personal mages’ were the rage in Orlesian nobility, and the prestigious families owned by them like one may own a pet or personal property. By somehow becoming Bastien de Ghislain’s mistress and using his influence, "Madame de Fer” liberated herself from all the social stigmata which should have pinned her down into a lowly courtier rank and turned the largely ceremonial office of “Court Enchanter” into a position of respect and power. This is huge move towards mage emancipation by the way, in a society where, again, Mages are feared and shunned and are constantly bullied, emasculated and taught to hate their talents. Vivienne is a shining example of what mages can become at the height of their power. Power she has, mind you, never actually abused before her Divine election. Vivienne’s actions will forever be under scrutiny not because of who she is, but because of what she is. The Grand Game can spit her out at any moment, which will likely result in her death.

Inquisitor: “You seem to be enjoying yourself, Vivienne?” Vivienne: “It’s The Game, darling. If I didn’t enjoy it, I’d be dead by now.”

Whether Vivienne was using Bastien for her own gain or whether she truly loved him isn’t a case of or/or. It’s a case of and/and. The perception that she was using Bastien makes Vivienne more fearsome and improves her position in the Grand Game, but deep down, I have no doubts truly loved him. Remember, Vivienne’s position at the Orlesian court was secure. She had nothing to gain by saving Bastien’s life, but she attempted to anyway. That Bastien’s sister is a High Cleric doesn’t matter - Vivienne can be elected Divine regardless of her personal quest’s resolution. She loved him, period.

No, I don’t think Vivienne is a good person. She treats those she deems beneath her poorly, like Sera, Solas, Cole and Blackwall (characters I like less than Vivienne), which I think is the #1 indicator for a Bad Personality. But I don’t think she qualifies as ‘Evil’ either and I refuse to dismiss the beautiful layering of her character. I genuinely believe Vivienne joined the Inquisition not just for her personal gain, but also out of idealism, similar to Dorian (again, Cole is 100% correct in pointing out the similarities between Dorian’s and Vivienne’s motivations for joining, as discomforting it is to her).

In her mind, Vivienne sees herself as the only person who can emancipate the mages without bloodshed - her personal accomplishments at the Orlesian court speak for themselves. Vivienne isn’t opposed to mage freedom - she worries for the consequences of radical change, as she believes Orlesian society unprepared for the consequences. Hence why she’s perfectly fine with a Divine Cassandra. Hence why her fellow mages immediately elect her Grand Enchanter of the new Circle.

Hence why Vivienne is so terrified by the Inquisitor’s actions if her disapproval gets too low. The Inquisitor has the power to completely destroy everything she has built and fought for during her lifetime. Remember: Vivienne’s biggest fear is irrelevance - there’s no greater irrelevance than having your life achievements reverse-engineered by the accidental stumbling of some upstart nobody. This is the real reason why she joins, risks her life and gets her hands dirty - the only person whose competence Vivienne trusts, is Vivienne’s own.

Even as Divine Victoria, I’d say she’s not bad, at all actually. Vivienne has the trappings of an an Enlightened Despot, maintaining full control, while simultaneously granting mages more responsibility and freedom, slowly laying the foundations to make mages more accepted and less persecuted in southern Thedas. Given that Ferelden is a feudal fiefdom and Orlais is an absolute monarchy, this is a fucking improvement are you kidding me. (Wait did he just imply Vivienne is secretly the best Divine - hmm, probably not because Cass/Leliana have better epilogues - but realistically speaking, yes, Viv should be the best Divine and it’s bullshit that the story disagrees.)

Underneath the countless layers of smarm, frost and seeming callousness, lies a fiercely intelligent and brave woman, whose ideals have been twisted into perversion by the cruel, ungrateful world around her. Envy her for her ability to control her destiny, but know that envy is what it is.

The flaw in Vivienne’s character isn’t so much the ‘tyranny’ or the ‘bitchiness’ or the 'smarm’. Her flaw is her false belief that she is what the mages need the most. Her belief that her competence gives her the prerogative to serve the unwashed mage masses... by ruling over them. For all intents and purposes, Vivienne is an Orlesian Magister and this will forever be the brilliant tragedy of her character. She was created by a corrupt institution that should, by all accounts fear and loathe her but instead embraced her. It’s that delirious irony that makes Vivienne de Fer one of the best fictional characters in RPG history. the next post will be Eurovision-related. :-)

#RPG#Dragon Age#Dragon Age Inquisition#Vivienne#Vivienne de Fer#Madame de Fer#DAI#Dragon Age 3#BioWare

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sherlock 10th Anniversary: Behind the Scenes Set Secrets

https://ift.tt/3juJvKp

Two chairs. A fireplace. 17 steps leading up from the ground floor. On the mantelpiece, letters pierced by a knife, cigars hidden in a coal scuttle and tobacco concealed inside the toe of a Persian slipper… Sir Arthur Conan Doyle provided a few compass points from which set designers on screen adaptations of his Sherlock Holmes stories could work when creating their 221B Baker Street. The rest takes imagination, artistry, a storyteller’s eye and , in the case of BBC One’s Sherlock, the odd bit of mischief.

To celebrate the 10th anniversary of Sherlock’s arrival on the BBC, production designer Arwel W Jones lets Den of Geek in on the behind-the-scenes secrets of 10 sets. Over to Mr Jones…

221B Baker Street

Credit: Arwel W Jones

Though technically speaking it was a Hartswood Production and not directly through the BBC, because we were on the plot in Cardiff’s Upper Boat [Studios] where Doctor Who was being shot, there was a big old prop store there that had a lot of things from Doctor Who and I did borrow a couple of things from there which maybe I should have hired… including some music manuscript that ended up on set. I hadn’t actually spotted at the time that it had some Gallifreyan text on it! So there is that little moment of crossover for anyone that really wants one.

John’s chair is that homely chair that everyone can probably remember their grandparent sitting in. It was a chair we already had that we reupholstered it in a nice tone that complemented the room. For Sherlock, I wanted something that was a timeless classic, like himself. As soon as we saw an image of the Le Corbusier… it ticked every box. It’s low at the back, for the practicalities of shooting, and had exactly that timeless elegance.

The skull was something I’d seen in a magazine, a differently shaped skull sprayed glossy black, and liked. Everywhere you go now you see skulls or bison heads, they’re in every tattooist, every barber shop, even in nice restaurants. I don’t remember seeing them much before that.

Credit: Arwel W Jones

Often I won’t finish deciding on how to decorate a room until we know who’s been cast. The look of the actor affects what you’re doing. Once you visualise that person as that character, it makes it easier to visualise their space. 221B reflects the timelessness of Benedict. His outfits and his look would work in any era and that’s what I tried to do with the space.

It’s a transient space that had different levels of eras. No-one would really decorate their place like that! It did work though. Both Sherlock and John, no matter which wall you look at, if they’re framed against any section, with all those different styles and looks and textures, they look good against them.

Victorian 221B Baker Street

Credit: Arwel W Jones

I loved what we were able to do with ‘our’ version of the Victorian one. I was lucky it happened that way round, rather than do just another Victorian 221B, it was a Victorian version of my modern one, which is slightly surreal.

It was about finding shapes, finding little things that filled the spaces in a very similar way, like the oil lamp that had the brass reflecting around it that was bang-on perfect the same shape and size as the 221B moon lamp in the same space. They were all hints that it was [taking place in Sherlock’s Mind Palace] but there wasn’t anything out of time. We were so strict on it because they didn’t want the hint to be there before. There were clues in dialogue but they were scripted. I didn’t want to be the bad guy who let the cat out of the bag!

The stuffed deer head with the ear horn was quite cool. I was very happy with the skull painting too. It’s a real Victorian image called ‘All is Vanity’ and it worked so well in that spot. It was very of the moment because of that obsession with death that the Victorians had.

I can remember the exact moment where we said ‘what shall we paint over there?’ and I went ‘Aha! It’s the study! We’ll do it in scarlet!’

Mycroft’s Office

Credit: Arwel W Jones

I wanted the idea that he was under your feet as you walked through Whitehall. The pattern on his ceiling is meant to be the underneath of those glass bricks that you walk over, that’s why that light comes in the way it does. We’ve always hinted that he ran the country, not the government and so he’s just there underneath, running everything.

When we did it the first time, it was the same time as doing the cell for keeping and interrogating Moriarty so we had that same feel.

If you look at the bare metal on the filing cabinets, everything is cold and calculated. The glass globe on his desk – world domination! All those things are there for a reason.

Eurus’ Sherrinford Cell

Credit: Arwel W Jones

This is about the coldness of the character and her calculatedness. It’s a smoother shape [than Mycroft’s similarly toned office], the curved ellipse of that cell, there are no edges so you don’t know what’s what. The colours and the textures obviously say coldness, but the glass and the concrete and the bareness were really about how dangerous she was, with no resource.

There are a few little Easter Eggs in there. If you look at the floor and markings on the wall, there are scratchings on the floor where the toilet and the shower would slide out. If you look at the table and the bed, they look like they can slide back into the wall. The idea is that if they wanted to, they could just leave her in a completely empty space and that she would never have to leave it. The round grate on the ceiling echoes the bottom of the well [where Eurus put John and ‘Redbeard’] but also the depths of the island. She was right at the bottom, on the bottom layer, the most secure. We played with the idea at one point of making it feel like it was underwater and there was an element of that in some of the lighting.

I was obviously looking at a lot of reference from Bond movies. That was a real nod to [Bond designer] Ken Adams, because he’d passed away that year sadly.

Magnussen’s Mind Palace

There’s a book [Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss] would reference all about helping your memory and it’s to do with associating things with particular memories. The weirder the thing you associate, the easier it is to remember it. So they told me to find weird and wonderful things! We had a fiberglass baby hippo in a dog bed in one corner, a rabbit pulling something out of a hat, rather than the other way around, a tree draped with gloves.

There was all manner of things on top of every corner of these ‘corridors of information’, including a painting of me at the end of one of them, which I don’t think you really saw. When we were doing The Sarah Jane Adventures years ago, we had a haunted house and there were things falling off the walls. We couldn’t let a hired painting fall in case of damages so I got one of the scenic artists to paint me as Rembrandt. That’s the one we knocked off the wall, so I had it, so I just put it in there as an extra bit of weirdness!

John’s Pilot Bedsit

Credit: Arwel W Jones

That was my favourite set from the unaired pilot. We were in the Coal Exchange in Cardiff that we were using downstairs for the therapist’s room and there was this little pokey room on the top floor. In the room next door they had that proper 1970s Sapele cladding, so I ripped that off one room and clad it around the one side. The tones of the bed covers and that Sapele and the lighting, it just felt like a miserable place, even though it had its own aesthetic.

This is what I keep going on about, even miserable places can have an aesthetic and look beautiful on screen. It added to his despair or his sense of not belonging. What we tried to do was recapture that in the first of the actual series. It was close, but I still think the one in the pilot was a better set in my mind. I didn’t quite get it right.

Read more

TV

Sherlock Designer Arwel W Jones: ‘There’s a Magic to Set Design’

By Louisa Mellor

TV

Sherlock: Steven Moffat on series 5 possibilities

By Kirsten Howard and 2 others

The Baskerville Laboratory

This was a real space, a microcomputer lab that had recently closed, so a lot of that was already there. I had one of the glass cases shatter on me, so I was standing in a pile of glass at one point while we were dressing that.

One of the team said she’d seen something on YouTube about how you could melt a plastic bottle and twist it into a jellyfish. We said, let’s have a go and that’s what the glow-in-the-dark jellyfish are, they’re all plastic bottles!

The monkeys were quite frisky! The male monkey really took a shine to the Grip. Really took a shine to the Grip. They had a tracking shot that was bringing the actors out of the elevator and every time the Grip passed the cage with the male monkey, shall we say he got a bit overexcited in an adult way, which was quite amusing to everyone there and very difficult for the cast to keep a straight face.

Culverton Smith’s ‘Favourite Room’

This was trying to have something that was really modern, because it was meant to be this brand new hospital he’d built and done all sorts of things to. We tried to go as ultra-modern in its feel, with all the LED lighting and the suspended lighting grid above the beds and the bank of coolers. It was about that feel of giving it complete coldness and newness. And having a viewing area, which was weird, but they do actually have that in a lot of mortuaries.

The wallpaper [in Sherlock’s hospital room next door] wasn’t TARDIS roundels, that was just nice wallpaper to give that room something extra. That was a real space, we built that extra wall into the Student’s Union in Cardiff.

John and Mary’s flat

I don’t think there’s a shot that really reflects it in the series, but in that little Christmas teaser [‘Many Happy Returns‘] there was a shot of John sat on the sofa on his own and in that, there are reflections of 221B. The sofa’s in the same place, there’s a light on the left hand side that gives the same kind of lighting as the moon lamp in 221B and I put a little skull-shaped vodka bottle in the cupboard on his right in the same place that the skull image would have been in 221B, just little things. It was a very different type of wallpaper but still a feature wallpaper wall behind him. He hadn’t quite let go. It was the same but different, was the idea.

We did a similar thing in Anderson’s flat (see below) in ‘The Empty Hearse’. That was a dangerous one to do, because what we were trying to do was a 221B that wasn’t quite working, or wasn’t quite right. You could get that very wrong and just get a messy set that didn’t look right. That was a bit more challenging if anything. It was Anderson trying to create his own 221B.

Credit: Arwel W Jones

[In Rosie’s nursery] and the bedroom, the tree and the fruits and the birds were a little reference to the décor of the wedding venue. It’s a nice wallpaper, also in Mrs Hudson’s corridor. The [black fish] mobile may have been a reference to what happens at the Aquarium, because we were talking about the cold, dead eyes of a shark.

John’s kitchen – even though we’d done the reflections of 221B in the flat, we also wanted to do the antithesis of it. The clutter of 221B versus the tidiness of that house. I read somewhere – biggest insult possible! – that it looked like an Ikea showroom of a house, which it wasn’t. There was a lot of stuff in there that was bespoke, but at the same time I can understand the reference. There were deliberately not a lot of signs of life, even the child’s toys are tidied away.

Scotland Yard

Credit: Arwel W Jones

It’s been three different places over the years. The first time it was in the old HTV studios in Cardiff, which no longer exist. That was flattened and is now a housing estate. When we went to look at it it was in kind of a dark blue, which was never going to look nice on camera, but I was looking at it with [director] Paul McGuigan who is a very, very strong Celtic fan and he said there was no way he’d film anywhere that was Rangers blue! So that’s why I painted in green and white hoops like Celtic shirts. So that’s where that colour scheme comes from.

I walked him on there and he said ‘I like this’ and I said ‘Have you realised?’ and he’s going ‘What? What?’ So I tell him ‘Green and white hoops!’ And he went, ‘You legend!’

See many more behind-the-scenes Sherlock photos on Arwel W Jones’ portfolio website.

The post Sherlock 10th Anniversary: Behind the Scenes Set Secrets appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3fXoXbc

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you describe Cressida Cowell's writing style? (And try to convince me to start reading httyd books while you're at it)

Oh my goodness, I am *SO* excited to talk about Cowell’s writing style!

I realized my FAQ page was outdated with a broken link (whoops!), so I’ve fixed that! If you haven’t check that page out or my up-to-date #faq tag, I’ve written many responses on why I recommend the HTTYD books. Obviously those posts aren’t focused on Cowell’s writing style, as you’re curious about. Nevertheless, since you’re interested in recommendations and perspectives regarding those books, these prior responses could be worth checking out, and I’ll happily boop you a link to some of those! [1] [2] [3]

Cressida Cowell’s writing style, to me, is a fascinating combination of simple and eloquent. This goes for how she forms sentences, constructs plot, uses tropes, and more. She takes seemingly common elements that most of us wouldn’t consider “special” - and utilizes them to powerful effect.

Her narration style is charming. In the How to Train Your Dragon books, she uses two similar but distinct writing styles. The prologues and epilogues are given a finesse different than the material in the main chapters.

The majority of her text is written in an almost whimsical, childish way - especially at the start of the series. Sentences are simple; descriptions are amusing; humor is prevalent; and her presentation is straightforward. Unashamed use of italics, capslock, font changes, and font size changes - plus childish scribbles for illustration - contribute to the youthfulness of her narration.

How to Train Your Dragon Ch. 1: First Catch Your Dragon:

“ANYBODY would be better than Hiccup,” sneered Snotface Snotlout. “Even Fishlegs would be better than Hiccup.”

Fishlegs had a squint that made him blind as a jellyfish, and an allergy to reptiles.

“SILENCE!” roared Gobber the Belch. “The next boy to speak has limpets for lunch for the next THREE WEEKS!”

There was absolute silence immediately. Limpets are a bit like worms and a bit like snot and a lot less tasty than either.

As the series develops, the main prose develops slightly, too. Fans often discuss how Cowell’s illustrations markedly grow in complexity from start to end, even as they retain their childish personality. Cowell herself has confirmed that these artistic changes are representative of Hiccup aging. The writing doesn’t change as notably, but it’s arguably there. So, this benign, whimsical narration takes on intentional effect: she’s writing a story about a child with prose that matches the character’s age. It helps us readers enter the mind of a child as we go through Hiccup’s younger years. It’s not to say that it means we can’t think through complex topics in this framework, because we do address deep topics in the breadth of the narration... but the childish writing style provides a personality and character and framing device for how we readers “feel” the story.

The prologues and epilogues are different. In first instead of third person, they’re written as the reflections of old man Hiccup in his eighties. The writing style here maintains simple characteristics in, for instance, word choice... but it’s mature in tone and topic. These passages are often my favorites, as they delve into interesting moral reflections tied to the adventures young!Hiccup is having in the main story. This is where Cowell shines the most in her combination of simple and eloquent. There’s beauty in what she writes in the prologues and epilogues. Reading them aloud, words flow marvelously (that opening passage in the first book... mmm yum), and you can hear the reflection of the man behind them. It’s where you’ll get quotes like:

How to Ride a Dragon’s Storm: Epilogue

Maybe all Kings should bear the Slavemark, to remind them that they should be slaves to their people, rather than the other way around. And to help them never to forget what it feels like to be a child... to be small and weak and helpless.

How to Betray a Dragon’s Hero: Prologue

Great things are only made out of love and out of pain.

A great sword must be made out of the very best steel. But what truly makes the sword great is what happens to the sword after it is made.

We call this the “testing” of the sword.

The sword is bashed and hammered and hollered into shape by the bright hammer. It is thrust into the fierce heat of the fire, where it softens, and then it is quickly quenched in water, where it hardens again. The higher the temperature, the fiercer the fire, the tougher and greater the sword eventually becomes.

The whole testing process can make a sword, or break it.

The same could be said for the making of a Hero.

Cowell’s still not using complicated vocabulary. Occasionally she’ll insert something like “indelible” into the text, but generally, it’s (superficially) simple language. However. It’s also thoughtful, eloquent, and markedly more mature than something you’ll get in Chapter 3 of the first book. “Great things are only made out of love and out of pain” is something I could embroider and hang on my wall - it’s that sort of a reflective quote.

The contrast of the two styles - the more childish and the more eloquent-mature - help us understand Hiccup’s life from two perspectives: the viewpoint of a kid experiencing dangers around him idealistically hoping to change the world, and the viewpoint of an adult reflecting back with complex moral understandings. And as Hiccup’s adventures become increasingly darker and he grows in age, the main prose will match the mood.

The writing style works. She doesn’t need a large vocabulary or complex sentential forms to sound thoughtful and imbue great adventures or thematic points. Cowell knows how to impart heart-felt concepts and great reflections for readers of any age, child to adult... and have us impacted by them.

Cressida Cowell’s use of tropes is similarly deceiving. The best writing, I believe, combines refreshingly new material with storytelling elements we’re familiar with - our tropes. I believe Cowell strikes the balance marvelously.

She brings in wildly creative new concepts - like a quirky world where dragon species are everything down to big-mouthed bee catchers or insect-sized nanodragons. Characters are equally as ridiculous and special; I’d be hard-pressed to find a personality similar to Camicazi anywhere in literature or media.

Cowell also knows how to use tropes. We so often see the feckless, unwanted, socially outcast wimpy protagonist turn into a Hero. We’ve seen a character with a special sword and a noteworthy family history. We’ve seen a character called by fate and prophecy to revolutionize the land before apocalypse. But that doesn’t make Hiccup a generic character handled blandly. Cowell balances fate with agency and with the challenges of reality. Hiccup has to make choices to save what he loves. And Hiccup is limited in what he can do. After all, “History is a set of repeating circles, like the tide. The wind does blow through the ruins of tomorrow. But it is more a question of two steps forward, one step back.” What we get is a Hero’s journey, but one where our Hero is truly spectacular, diligent, unyielding, pushed to the brink, and endlessly inspirational.

I think the thing that impresses me the most in how Cowell handles tropes is the “it can’t get any worse and then it does” concept. We’ve seen it before. Stories make protagonists go through a dark low. And when the character doesn’t think situations can worsen, they do. What makes the HTTYD series so spectacular and unique in how it’s handled... is the sheer repeated beating Cowell does. It’s overwhelming. She keeps going, and going, and going, and going, and doesn’t stop. Other authors would have stopped five bad events ago! It’s to the point that, in book ten, after so many bad things repeatedly occurred, I cried when Hiccup reached one small positive in his efforts. The author isn’t afraid to put our protagonist through the ringer, thereby making every bad experience, and good experience, impacting, memorable, and sometimes shocking to us as readers.

Cowell definitely uses plot devices we’ve seen before. But she weaves them together impactingly, making an emotional ride through high highs and low lows. We’re left with an inspirational takeaway and a Hero’s development we won’t forget.

Cowell’s long-term plot structure is brilliant, too. She divides the series into three equal parts, more or less. The first part is the “isolated” series of whimsical, innocent, childish adventures. The second part makes you squint suspiciously, realizing you’re getting into more complex and dangerous incidences than you expected. The third part is what I lovingly call “the Ragnarok of pain and despair.”

The starting books, deceivingly, seem like isolated, simple adventures. Cowell’s actually setting ALL the stages for the series’ later turmoil. She’s inserting characters, items, prophecies, themes, conflicts, and plot points that will become extraordinarily impacting as the series continues. But readers don’t notice Cowell’s clever, thorough foundation. They just see cutesie, simple, isolated incidences first read through.

The middling section is where Cowell starts to utilize what she set up. She begins implementing chaos and intertwining strings, pulling Hiccup’s life from random childhood incidences with Alvin and dragons... into something centrally important. She brings together the history of the Barbaric Archipelago with the current events Hiccup’s experiencing around him. All Hiccup’s starting point experiences from the first books become formulative to the choices he has to make now. And all the while, there’s the stewing build-up of a central conflict... which explodes at the end of the second part.

The third part is all-out war. All-out drama. All-out danger. All-out stakes. We see how everything Cowell wrote is interconnected, from the start of the series to whatever conclusion Hiccup’s journey will bring. Moral themes and questions are central; characters are pushed into growth; what we thought was some random thing at the start turns out to be a cleverly-inserted Chekhov’s gun. It’s the payoff to all the set-up and build-up... brilliantly, effectively executed.

Obviously I can’t give examples to you. That would be spoilers. XD To people who’ve read the series, I’ll just say, for one example: all the King’s Things. That’s one example of Cowell’s build-up. But the build-up is everything from moral themes, to character dynamics, to foreshadowed historical revelations. It’s well-paced, well-thought through, well-executed.

The How to Train Your Dragon books are thus both simple and eloquent. And that which is simple isn’t “watered down” - it’s “simple” with purpose, “simple” with complexity, “simple” with personality, “simple” with power.

This is why I always encourage people to keep reading after the first few books. Some people find the starting adventures adorable, loving the charm and humor. I adore that all myself! They’re legitimately treasurable books in and of their own. Other readers aren’t as interested in the cutesie stuff, approaching the first HTTYD books with skepticism; they don’t think that these benign stories are “their thing.” However, every time I’ve encouraged skeptics to read after the first few books, they get sucked in, and find themselves screaming and crying and laughing and celebrating with Hiccup’s dynamic adventures. It’s all because Cowell’s simplicity is deceptive: there’s so much more going on, and there’s always more going on the deeper in you look.

#long post#httyd books#faq#httyd#How to Train Your Dragon#How to Ride a Dragon's Storm#analysis#my analysis#Cressida Cowell#ask#ask me#loveallcute

399 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Oft Overlooked A BUG’S LIFE

A BUG’S LIFE…

What can I really say about this movie that other animation fans on the internet haven’t already? It was critically dubbed Pixar’s most mediocre film before the horror that is the CARS franchise.

I was about nine years old when this film came out, and I really liked it then. Honestly, I still kind of do, but admittedly some of it is nostalgia on my part and I’m well aware that it could have been better.

Like I said, this film has been talked about by other online critics about how it is okay, at best. That it was just the Pixar placeholder in between the first two TOY STORY movies. However for the purposes of this article I would actually like to highlight some of the good things about this movie, or at least my reasoning for why I still have a fondness for it.

Now before I continue I do feel like I should address two big elephants in the room: Namely, John Lasseter and Kevin Spacey. Knowing what we know now about them, if you can’t watch this movie without feeling uncomfortable, I totally understand. I’ll admit it makes me a wee bit uncomfortable to watch the film now, and more so the behind-the-scenes featurette on the DVD. (Wish I could blur their ugly faces when they’re being interviewed…)

However my opinions of this film on its own have nothing to do with them or whatever they contributed to the film, so they are irrelevant to what I have to say here. As far as I’m concerned if they hadn’t been involved in the film someone else would have taken their place, and those other people would have done just as good a job, if not better. Not to mention they would have been able to do it without being complete and utter creeps. To conclude, Lasseter can go suck a jellyfish and I hope Spacey rots in hell.

I’m going to primarily talk about the things I like about this movie, both then and now. But before I get to that I’m going to talk about why I agree with most critics who consider this one of Pixar’s lesser films.

A big problem with the movie is primarily the story and characters being a bit weak.

Part of that problem is the story’s initial structure. It’s clearly a retelling of Akira Kurosawa’s SEVEN SAMURAI; village is being attacked by thugs, one villager leaves to get help in the form of warriors, villager brings back help, and they successfully fight off the invaders.

Probably the biggest difference in story is SAMURAI ended on a bittersweet note due to casualties among the samurai themselves, whereas BUG’S LIFE didn’t have any real casualties on the heroes’ side. That said, though, it’s funny that the ants seemed so damn certain there would be.

Initially modeling an original story off of a classic isn’t a bad thing in of itself. Back when I was in college it was something a lot of my writing and animation professors encouraged: learn from the classics. Not just film, but also literature and mythology.

The thing is SEVEN SAMURAI as a film was three to four hours long. It had time to accommodate for its fairly large cast, while still keeping its focus on a select few.

BUG’S LIFE, however, was only maybe an hour and fifteen minutes long. The writers probably could have stood to trim down some of the Bug Circus and take time to polish the story rather than try to give EVERYBODY an opportunity to have a funny line.

Having a couple ensembles in place isn’t a bad thing. They had that in TOY STORY with Andy’s toys, the Little Green Men in the claw machine, and the mutant toys. The groups, however, were smaller in that movie, and in the case of the Mutant Toys they had no speaking lines and had to convey everything with silent acting.

However something that’s been pointed out is that with Pixar films there was always a real progression in technical quality. That with each movie they got better and better with the tool of their trade that was CG animation.

Let’s look back at TOY STORY. The reason they made the characters plastic toys was because that’s just what their character models at the time always looked like. It would be a long way before they could even consider rendering complex fur textures for MONSTERS INC., and more complex still Merida’s tangled head of hair in BRAVE. It’s why the human characters in TOY STORY also look a bit weird and plasticky by today’s standards.

With TOY STORY they accomplished lively character animation in 3D. With TOY STORY 2 they managed to make better looking, less stiff human models like Al of Al’s Toy Barn, and slightly nicer fur textures on Buster the dog. MONSTERS, INC. had the aforementioned complex fur textures for Sully and some pretty decent early snow effects.

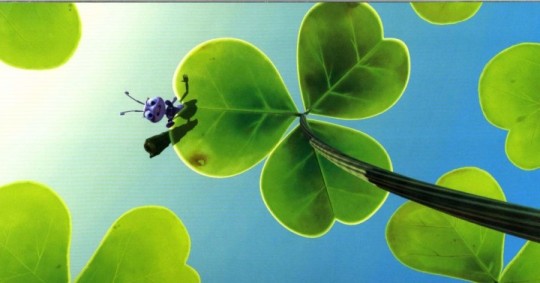

So what did BUG’S LIFE accomplish on a technical level?

Two words: textures, and lighting.

The last time I watched BUG’S LIFE I was absolutely FLOORED by how beautiful the set pieces were.

Take this scene of Flik giving Dot a pep-talk.

All that detailing in the blades of grass in the background, the pebbles on the ground, the textures on the pebbles, the textures on Flik’s contraption, and even the textures on the characters. It blows my mind trying to imagine how long it took to create those models, differentiate between the more see-through nature of the grass blades and the opacity of everything else, and arrange them in a way that makes for a convincing bug’s eye view of a patch of grass.

Then there’s the scene of the grasshoppers breaking into the anthill.

TOY STORY had some decent lighting that helped establish the needed atmosphere, but I don’t recall it being nearly this crisp.

Once again, there’s the textures on the objects and characters. As a kid, while I was aware the film was CG animated, I found myself speculating if the grasshoppers’ muzzles were made of foam rubber.

These were all things I took for granted as a kid, because I did not yet have the experience to know just how much work and skill it takes to make 3D animation.

This is a still from a minute-long film I made in a 3D computer animation class. I was given maybe only a couple months to make it. That included having to navigate my way through these complex computer programs I was completely unfamiliar with, and technical difficulties like the textures not grafting onto the models right. Let me tell you, it was a pain in the ass.

I look at the backdrops for BUG’S LIFE and I’m left to ask: “How many computers CRASHED trying to render all that?” Because, believe me, that happens. A lot.

Also, here’s the thing. When technical elements of a film are done well, such as lighting or camera focus, the audience LITERALLY doesn’t notice it. They’re too swept up in the story because the visual storytelling keeps up the illusion for them. The audience only notices important technical details like this when they’re done BADLY, hence a lot of people outside the film industry really take for granted just how much work and skill is taken into making a film that looks good.

(It’s why I think everyone should watch FOOD FIGHT at least once in their lives, especially animation fans.)

Okay, while it is inevitable that I would bring up Dreamworks’ ANTZ, I’m not going to talk too much about it. (It’s like the Cola Wars; everyone inevitably picks a side.) All I’ll say for now is I’ve always preferred BUG’S LIFE because it’s nicer-looking design-wise and its content and execution is more family-appropriate. (Also, in 1998 we didn’t know at the time Kevin Spacey was a creep, but everyone and their DOG knew Woody Allen was. Nice job, Dreamworks!)

It’s been pointed out that there’s a distinct casting difference between ANTZ and BUG’S LIFE. ANTZ had a cast of recognizable movie actors, while BUG’S LIFE had a cast of recognizable television actors.

For BUG’S LIFE that’s not necessarily a bad thing. One of the things that bothers me about celeb casting in animated movies is that oftentimes it feels like a flimsy attempt at star-power when said stars don’t have the power to elevate the characters. Actors who might be good front of a camera but bring nothing to a recording booth.

However for the most part Pixar has been really good at casting well-known actors who actually fit their characters and add some personality to them. BUG’S LIFE was no exception.

In fact, quite a few of them had loaned their voices to animation before this film, and some damn good performances too.

And I can name at least one BUG’S LIFE alum who graduated from funny performance to heartfelt performance with Pixar…

(… I’m not crying! YOU’RE crying!)

But I digress. I consider the casting for this movie pretty solid. (With the obvious exception of Kevin Spacey.)

What’s more, growing up I remember a lot of the TV spots for Pixar films usually down-played the celeb cast and let the product speak for itself. The celeb casting was less of a selling point for the films and more like a fun little Easter egg for the parents who had to take their kids to the theater.

Earlier I stated that the story and characters in BUG’S LIFE are a bit weak, and I stand by that. However there are a couple characters I’d like to highlight here as I’ve always found them interesting and memorable in their own ways.

First, let me talk about Hopper for a minute.

(I’ve already stated that Kevin Spacey can rot in hell, so there will be no more of that.)

I’ve heard criticism about Hopper as a character that he was a very bland, one-dimensional villain. To be fair, they’re not wrong.

But the thing I always liked about Hopper is that his one and only goal is to hold dominion over the ant colony. To keep them under his foot, both literally and figuratively, and he wasn’t afraid to use deadly force to do that. He was willing to kill a few of his own goons just to illustrate a point. That’s how threatening he was.

In a lot of children’s media I had seen up to that point, there were several bully characters that were often portrayed as the bigger kids who would demand your lunch money. They were usually ineffectual doofuses like Bulk and Skull from POWER RANGERS, or kids with serious insecurities like Binky Barnes from ARTHUR. While not the first of his kind, Hopper was one of the first characters I had ever encountered as being a prime illustration of not just a bully, but one who had the makings of a dictator.

With his rather one-note motivation, I can see why audiences found him bland, but given his violent means of staying in power, I’m glad they didn’t try to make him “complex” or give him any sympathetic character traits.

Frankly, we live in an age where horrible people are romanticized in the media as being “misunderstood”. I feel like, unlike those media outlets or the upcoming JOKER movie, BUG’S LIFE gets it. They don’t deserve to be portrayed with humanity. These people are monsters. Nothing more.

Maybe if Pixar hadn’t felt the need to rush the production maybe Hopper is one of many characters that could have been polished up a bit in the writing process. Give him some more distinct, memorable traits as a character. Maybe hints at a backstory of Hopper having a long-standing history of using and abusing others, and always getting away with it.

(When I put it that way, we can just say Hopper is the John Lasseter Story. Just draw a pair of glasses and a tacky shirt on the guy and it’s a spitting image.)

The other thing I’ve always liked about this movie was the portrayal of Princess Atta.

Besides being the first Pixar Princess, I always liked how, unlike the Disney Princess pantheon up to date in the late 90s, Atta actually had a bit of a character arc related to the fact that… well, she’s royalty! She’s going to have to take over the colony eventually as queen.

We see this from the beginning as she’s overseeing the harvest and going into a panic when things go even slightly wrong. Also, I find it interesting that it’s a guy that screws everything up when Flik accidentally destroys the food offering, yet she’s the one who gets blamed for it. (Ironic commentary coming from the studio led by an egotistic creep who wouldn’t let women in on meetings.)

But what I loved about her as a kid was that her personality and approach to things was a lot more real and down-to-earth than your average glamorous Disney Princess. She felt less like fairy tale royalty and more like a woman up for promotion at a big company. From a pragmatic standpoint that can be just as scary, stressful and daunting.

(It also feels appropriate in hindsight considering her voice actress Julia Louis-Dreyfus would later star on VEEP…)

My friend @baxterfilms and I have had a lot of discussions about this movie, and we agreed that Atta should have been the protagonist. She actually has a character arc of her own of being unsure of herself at the start of the film, taking charge in the second act, and eventually standing up to Hopper in the third.

Remove Flik entirely, and have her go on a journey to find reinforcements against the grasshoppers. Have her realize that Hopper’s demands are impossible, she’s sick of having to adhere to him, and have her sneak out to get help. When she finds out she literally brought home a bunch of clowns, she understandably freaks out. She has to figure out a resolution because there is a lot of pressure on her to make things right and free the colony from bondage.

Strangely enough, with that version of the story you could still probably have all the indulgent fun of the celebrity cast. It’s just the very core of the film’s story needed some serious tightening up, and maybe Dave Foley as Flik would have fared better as a comic relief sidekick.

With all that said, I thank you for taking the time to read this. I really do think that this film is highly under-appreciated in the animation community. There might have been trouble in the writing room, but the technical achievements in this film were still there and helped Pixar hone their craft into making their animated features as stunning as they are heartwarming.

I have to say, though, I find it funny that there’s almost a pattern to these insect-driven animated movies. Going all the way back to MR. BUG GOES TO TOWN, they usually have rather weak leading characters, and the supporting cast winds up leaving more of an impression.

Weird, huh?

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello. I don't know if you're doing requests rn, but could you do a arumika mermaid fic??? I jus saw an amazing art of it by askmermanlevi tumblr, and now i can't stop wishing to read about it.

thank you @askmermanlevi for creating such a wonderful mermaid au w/ so many snk characters. i hope it’s alright that i wrote a mermaid au inspired by your au esp since i reused your cute design for mermaid mikasa xoxo

To the End of the Ocean

Arumika. Mermaid AU.

1693 words.

Buy me a ko-fi!

There are those that are daring enough to explore the vast expanse of the ocean, but Armin is not one of them. The depths of the ocean have always intrigued him, and yet he has always wondered what lies past the barrier of coral that he has come to know so well. It is not that he is frightened of what lies ahead - stinging jellyfish, ravenous sharks, and vicious stingrays. He knows those obstacles will be there, that they exist in the ocean. It is his fear of the unknown that prevents him from leaving his small space in the sea. How can he abandon everything he’s ever known - the little shallow pool near the shore that he rests every night with his grandfather, the colorful reef he visits with his childhood friend Eren, and the beautiful caverns filled with gentle crustaceans that he sometimes takes shelter in when the sea is restless - for something he’s not even sure is there? He fears that whatever lies ahead will only underwhelm him or perhaps be too much for him to handle, and he will always yearn to be back home as soon as he leaves. Still, he continues to look through the vast blue waters, wondering what he would encounter if he ever dared to venture further than he had ever gone before.

Instead, he tries to satisfy himself with the tales that travelers weave as they pass by every year, sometimes showing off souvenirs that they had acquired on their travels. There’s another mermaid in particular whose stories captivate Armin the most. Although she’s the same age as him, she’s traveled more of the ocean than he ever will. Perhaps others in Armin’s position would be jealous, but Armin had never thought to be envious. He’s too busy marveling at her as he listens to the stories she tells.

Mikasa, the mermaid mentioned, sits at the center of a crowd of other curious merpeople. Although she’s been doing this for years, it’s still strange for Armin to see her like this. When they had just been merchildren learning how to swim, he never thought she would swim across the ocean. Perhaps he should have followed her.

The audience members listen intently as she describes the wondrous sights she had witnessed as she traveled the sea. Her family - all of them travelers - had just returned after journeying to a curious ocean filled with sweet water. It makes all the creatures there sweet-tempered and kind, she says, and the seagrass taste of sugar. She had been lucky enough to bring some for those who wished to try it as well.

As she passes it around, others ooh and aah at the peculiar seagrass, its pink tips and ruffled edges making it so different from the seagrass that they’re typically used to seeing. Armin, however, takes little notice of it aside from a quick glance. He’s more interested in Mikasa, how her vibrantly colored tail - glittering with scales of orange and black and white - swishes back and forth and how her gray eyes light up as she recalls her time in the strange sea. He wishes to see that same sea with his own eyes someday, but he does not believe he’ll ever have the courage to travel as Mikasa does. He’s content to just listen to her stories, living through her tales that she spins as her usually calm demeanor barely contains her excitement.

The ending of her storytelling is always Armin’s least favorite. He always wishes that such storytellings can stretch until early the next morning, but he realizes that would be silly. Still, he always wishes that Mikasa would continue with her stories, sharing the details that were perhaps lost in between. Others, however, seem satisfied with tonight’s stories, and the crowd is already dispersing. They’re off to their comfortable homes, but Armin trails behind, wondering when the next time for Mikasa’s travels will be. He’s so lost in thought that he doesn’t notice that someone has swum in front of him, dangling a piece of seagrass in his face.

“Mikasa!” Armin says, surprised. He’s thankful that he didn’t bump into her. He backs up a bit, swallowing nervously. “I … I liked your story tonight. It was very beautiful. I wish I could have seen it myself.”

“Thank you. I was worried that you didn’t like it,” she tells him. Mikasa smiles graciously and offers him the seagrass once more. It’s even softer and more colorful up close, the gentle blades of green and pink swaying with the movement of the ocean. “Here. I noticed you didn’t take some earlier, so I saved a bit for you.”

“But I don’t have anything to give you in return,” Armin mumbles. It’s traditional for travelers like Mikasa and her family to bring souvenirs, and listeners trade those souvenirs for food and other goods as a sign of gratitude for the gifts and entertainment. Armin usually only brings a shell from offshore to trade with, but he seems to have forgotten to bring one tonight.

Mikasa shakes her head. “It’s fine. I already received a lot of things already,” she laughs. She watches as he takes the seagrass from her and nibbles tentatively at a blade. When his eyes grow wide at the peculiar taste of them, a smile spreads across her face and she lets out a satisfied laugh. “Ah, I’m so glad you like it! Isn’t the taste peculiar?”

“It is,” Armin agrees as he chews a little more. As he chews, he can taste a hint of the sugar-sweet sea that Mikasa had once described. He wonders if the waters there are also blue, or perhaps they are tinged with a tint of pink just like this seagrass is. Are the animals there sweet as well? Do they swim together, schools of pastel-colored fish mingling together, or do they swim in separate groups, patches of colors gliding through? Does coral grow there, and does it spiral up into violent spikes or does it bloom upward into soft branches? Can you still see the moon glisten on the surface of the ocean, or does it look different from how it does here? He wishes to ask her all of these questions and more, but he can’t bring himself to be so rude. After all, she must be tired after returning home from such a long travel.

The two of them swim slowly through the water in silence for a moment before Mikasa speaks again. “I’m grateful that you always come to my storytellings, although I feel that I can never do the sights I see much justice,” she confesses, looking down at her webbed hands. “I love that you’re so interested in my stories. It calms me to see your face in the audience whenever I return.”

Her words surprise him. “But you describe your journeys so well! You don’t over embellish things, but the way you talk with your words and the expressions on your face … it makes me feel as if I were there with you.” Armin stops flipping his fins, allowing the sea to push him forward. “And it … it makes me wish that I had been there with you.”

Mikasa studies his face for a moment, drifting alongside him as the waves of the ocean pulled them forward. Finally, she says, “Why don’t you come with me next time?”

“What?” Armin asks, startled. He thinks that she’s joking for a moment - there are times where she makes peculiar jokes - but her expression is earnest. Quickly, he collects himself and mumbles, “I couldn’t possibly … I’m not suited for that kind of life.”

“Is that so?” Mikasa asks, eyebrows raised. She twirls around him, the swirl of water cool against his skin. “There isn’t anyone else in the world more suited to it than you. I have yet to see anyone so captivated by the idea of exploring the ocean, and there is that hunger to discover every single inch of the sea that even I don’t have.”

“I’m sure that’s not true,” Armin mumbles, but Mikasa ignores him.

“And I’ve always thought,” Mikasa continues, watching him carefully, “that traveling the ocean with you would be a lot more fun.”

It’s not that he was afraid of the unknown, Armin realizes now, but that he lacked confidence in himself. It didn’t matter what he found out there - whether it met his expectations or not. He could always return back home. He just needed a little push to finally swim past that coral barrier, and here was Mikasa reaching out her hand for him. All he had to do was take it.

“Maybe next time,” Armin replies, and it seems his answer is sufficient enough.

Mikasa reaches out to wrap her webbed fingers around his hand and gives him a quick squeeze. “It’s going to be wonderful,” she promises him. She squeezes his hand once more, a smile on her face, before swimming away to return to her family.

Armin doesn’t leave for home, not immediately. He remains drifting in the middle of the sea, watching as Mikasa grows smaller and smaller until she vanishes completely. All the while, he thinks about the adventures at sea they’ll have in the near future: encountering dangerous beasts, discovering new fauna and flora, and excavating ruins of shipwrecks and discarded human artifacts. These are things that excited him and frightened him before, but now the thought of such things exhilarates him. He can’t believe he had confined himself to this corner of the ocean for so long. Ah, but he can make up for that soon. With Mikasa, he can see himself traveling to places he had always dreamed about and going to places so magnificent he could never conjure with his imagination alone. What a glorious and curious feeling she has awakened in him, he thinks, but wonderful nonetheless. He hungers for adventure without worry now, and he knows this craving will only be satisfied once he’s traveled to the end of the ocean. And, as Mikasa has said just a few moments before, he knows it’s going to be wonderful.

#mermaid au#arumika#mikasa ackerman#armin arlert#snk#requests#asks#answered#anon#anonymous#i hope it's alright!#if it's not just tell me and i'll delete this!

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maybe the paywall is down, (and maybe it’s not meant to be!) but snatched the copy for you all:

Ian McKellen, co-founder of Stonewall: I think it’s best for me not to get involved in the trans debate

Ahead of their new play, McKellen and Endeavour’s Roger Allam discuss their friendship, playing Hitler and the lost art of debate

By Chris Harvey

7 June 2023 • 7:00pm

“It’s too early for this sort of thing,” says Ian McKellen to Roger Allam, as they arrive for a photoshoot at a rehearsal space in east London. It’s 11am, but the distinguished knight of the realm was at the Hampstead Theatre last night, where the audience sang Happy Birthday to him – it was his 84th – so we can perhaps assume that he’s been celebrating. He’s wearing a stylish brown felt hat that would be too understated for Gandalf, with a large, blue silk scarf wrapped around his neck; Allam’s in a navy blazer. No sooner are both in front of the lens than all traces of crotchiness vanish, and they start to muck around and perform.

McKellen’s double act with the triple Olivier award-winner, who has just come to the end of a decade playing DCI Fred Thursday in Endeavour, goes back a while. “I don’t think of Roger as just an actor, friend and colleague,” McKellen says. “He’s a father of two lovely boys, who I’ve seen grow up, and he has a lovely partner [actress Rebecca Saire]. I feel that he’s a stable man getting on with life and coping with all the problems of family life, which I don’t have to do because I’m single. And I feel when I’m in his company, particularly when I’m with the rest of the family, that I’m a surrogate uncle or something.”

In 1988, when both were in Glasgow to see Peter Brook’s Mahabarata, McKellen asked Allam to carry a banner on a march to protest the government’s repressive Section 28 legislation against homosexuality. He did so, despite “the most appalling hangover” from a drinking session the night before. “He’s the most gay-friendly straight man I know,” says McKellen.

Together, they’re charmers. Allam, now 69, is unfailingly droll, McKellen a storyteller who pulls you into his anecdotes with that rich, reassuring baritone that can stiffen into the voice of power and authority as it did in Lord of the Rings, or darken towards cruelty, as in his fascist Richard III.

The two first worked together in panto in 2004, sharing a dressing room to play Widow Twankey (McKellen) and the evil Abanazar (Allam) in Aladdin, then reunited for the film Mr Holmes in 2015. Today, we’re chatting about the two-hander they’re rehearsing – Frank and Percy, written by the young East Midlands’ playwright Ben Weatherill, whose play Jellyfish, about a woman with Down’s Syndrome falling in love with a neurotypical man, transferred to the National in 2019.

The play is about the closeness that develops between two men who meet in the park every day with their dogs, and actually talk to one another – although they don’t agree politically. Allam plays Frank, a widower who “cried in Tesco’s the other day”, and McKellen is Percy, a writer and openly gay man who rages about the modern world and the way the younger generation is taught “what to think”.

His outspoken views on climate change risk him being de-platformed. Allam doesn’t think people should be de-platformed but suggests that it’s not an exclusively modern phenomenon: “That’s always gone on – people will protest against people taking up certain positions.” Enoch Powell, after his Rivers of Blood speech in 1968, would have occasioned protests if he’d followed it with campus speaking engagements, he says. “Ideally, people should be allowed free speech. But of course, it depends on what they’re saying.”

McKellen is enjoying the way that the play addresses “now”. There’s even a fleeting reference to the trans debate. McKellen, of course, was one of the co-founders of Stonewall, which has had an enormous impact on British society, on issues such as the legalisation of same sex marriage, and the lifting of the ban on gay people in the Armed Forces. Yet Stonewall now finds itself on the front line of the arguments over self-identification of sex and gender.

In the 1980s, McKellen sat on TV chat show sofas politely arguing for equality, but he’s understandably reticent about getting involved in a debate that has become so polarised. “Many, many people we debated with simply had never met a gay person before, wittingly,” he recalls. “I think a little bit the same may be true of trans people.

“If only [the opposing sides] would stop shouting at each other and thinking the worst of each other and sit down and talk to each other, it might all be alright,” he adds. “But I think it’s best for me not to get involved because I see merit in the arguments of both sides, and both have their own needs.”

The poisonous nature of the row, Allam notes, has not been helped by social media – or as he refers to it, “Twitter and all that s---.” McKellen has a similar view of a future that includes AI – “Oh thank God, I don’t have to cope with that.”

Allam is the son of a London vicar; McKellen, of course, grew up in the North, in Wigan and Bolton, Lancashire. I wonder what both are thinking about the government’s determination to take arts funding out of London and redistribute it to the regions as part of its levelling-up agenda. The English National Opera, for example, will continue to receive funding only if it moves its headquarters out of the capital. For Allam, who studied singing at the ENO and went on to play Inspector Javert in the original West End production of Les Miserables, the new funding diktat is “just stupid”.

McKellen points out that the great regional metropolises – “Leeds, Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham… there’s a confidence there. It’s a different question if you go to Bolton or Wigan or Blackburn or St Helen’s or Warrington, they seem to be there now just to feed Manchester. Those places, having lost their industries, whether it’s cotton or coal or whatever, need looking after… [but] you shouldn’t do it by taking money away from London.”